How many minutes are twins born apart

The effect of twin-to-twin delivery time intervals on neonatal outcome for second twins | BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

- L. Lindroos1,

- A. Elfvin2,

- L. Ladfors1 &

- …

- U.-B. Wennerholm1

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 18, Article number: 36 (2018) Cite this article

-

11k Accesses

-

18 Citations

-

4 Altmetric

-

Metrics details

Abstract

Background

The objective was to examine the effect of twin-to-twin delivery intervals on neonatal outcome for second twins.

Methods

This was a retrospective, hospital-based study, performed at a university teaching hospital in Western Sweden. Twin deliveries between 2008 and 2014 at ≥32 + 0 weeks of gestation, where the first twin was delivered vaginally, were included. Primary outcome was a composite outcome of metabolic acidosis, Apgar < 4 at 5 min or peri/neonatal mortality in the second twin. Secondary outcome was a composite outcome of neonatal morbidity.

Results

A total of 527 twin deliveries were included. The median twin-to-twin delivery interval time was 19 min (range 2–399 min) and 68% of all second twins were delivered within 30 min. Primary outcome occurred in 2.6% of the second twins. Median twin-to-twin delivery interval was 34 min (8–78 min) for the second twin with a primary outcome, and 19 min (2–399 min) for the second twin with no primary outcome (p = 0.028). Second twins delivered within a twin-to-twin interval of 0–30 min had a higher pH in umbilical artery blood gas than those delivered after 30 min (pH 7. 23 and pH 7.20, p < 0.0001). Secondary outcome was not associated with twin-to-twin delivery interval time. The combined vaginal-cesarean delivery rate was 6.6% (n = 35) and the rate was higher with twin-to-twin delivery interval > 30 min (p < 0.0001).

23 and pH 7.20, p < 0.0001). Secondary outcome was not associated with twin-to-twin delivery interval time. The combined vaginal-cesarean delivery rate was 6.6% (n = 35) and the rate was higher with twin-to-twin delivery interval > 30 min (p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

An association, but not necessarily a causality, between twin-to-twin delivery interval and primary outcome was seen. An upper time limit on twin-to-twin delivery time intervals may be justified. However, the optimal time interval needs further studies.

Peer Review reports

Background

Twin gestations are increasing worldwide as a result of higher maternal age and conceptions resulting from assisted reproductive technologies (ART) [1]. These pregnancies and deliveries are a challenge in obstetric practice. Twin gestations increase the risk of morbidity and mortality of both children, mainly due to preterm labor, intrauterine growth restriction and circumstances unique to twin pregnancies such as twin-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) and umbilical cord complications [2,3,4].

It is not only the pregnancy itself but also the delivery that constitutes a greater risk to twins than singletons. Kiely showed that normal sized twins (birthweight > 3000 g) had a 70% increased risk of perinatal mortality and a threefold increased risk of intrapartum death compared to singletons [5]. The second twin is at higher risk than the first twin [6, 7] mainly due to the second twin being more difficult to monitor and also because complications such as cord prolapse, premature placental separation and fetal distress during labor are more common in the second twin than in the first one [8,9,10].

Several studies over the years have resulted in quite a clear understanding of how to deliver twins with regard to their presentation and gestation. Vaginal delivery is advocated if the first twin is in cephalic presentation, both twins are normal sized (1500–4000 g) and the second twin is not substantially larger than the first [7]. There is however no consensus as to whether the time between deliveries of the first twin and the second twin affects the neonatal outcome for the second twin. Some studies show that the risks mentioned above increase with a prolonged twin-to-twin time interval > 30 min [9, 11] as well as the risk of a combined vaginal-cesarean delivery [3, 4]. A correlation between longer twin-to-twin delivery intervals and decreasing pH in umbilical arterial blood gas, as well as a reduction of Apgar scores in the second twin, have been found in several previous studies [11, 12]. It has been suggested that the time interval should be kept short, ideally below 30 min. However, there are also a few studies showing that this is not of clinical significance and that there is no need for an upper time limit [9, 13, 14]. Recent guidelines as those from The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists offer no guideline regarding the optimal delivery time interval [15].

Some studies show that the risks mentioned above increase with a prolonged twin-to-twin time interval > 30 min [9, 11] as well as the risk of a combined vaginal-cesarean delivery [3, 4]. A correlation between longer twin-to-twin delivery intervals and decreasing pH in umbilical arterial blood gas, as well as a reduction of Apgar scores in the second twin, have been found in several previous studies [11, 12]. It has been suggested that the time interval should be kept short, ideally below 30 min. However, there are also a few studies showing that this is not of clinical significance and that there is no need for an upper time limit [9, 13, 14]. Recent guidelines as those from The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists offer no guideline regarding the optimal delivery time interval [15].

The aim of the current study was to investigate the relation between twin-to-twin time interval and the neonatal outcome for the second twin, considering both metabolic acidosis and Apgar score at birth, as well as neonatal mortality and morbidity within the first 28 days of life. The study was conducted at an obstetric unit where active management of the delivery of the second twin is not advocated.

The study was conducted at an obstetric unit where active management of the delivery of the second twin is not advocated.

Methods

After ethical approval from the Ethical committee at University of Gothenburg, Sweden, information regarding all twin deliveries at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden, between 2008 and 2014 was retrieved from Obstetrix, a computerized obstetric medical record system. This university teaching hospital is the largest obstetric unit in Sweden and has an average annual delivery rate of 10,000 deliveries. A total of 527 twin deliveries were studied after exclusion of the following deliveries:

-

delivery before 32 weeks of gestation

-

the first twin delivered by cesarean section (CS)

-

intrauterine death of one or both twins before onset of labor

-

known fetal malformations or chromosome aberrations in one or both twins

-

monoamniotic twin gestations

Because of its possible impact on neonatal outcome, information regarding maternal age, body mass index (BMI), smoking, parity, previous CS, maternal chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, diabetes mellitus type 1 or 2, gestational diabetes, gestational age, chorionicity, induction of labor, regional anesthesia, presentation, mode of delivery, time of delivery of both twins and birthweight was collected. From this information twin-to-twin time interval, large for gestational age (LGA), small for gestational age (SGA) and inter-twin birthweight discordance was calculated. LGA and SGA was defined as a birthweight of greater than + 2 standard deviations (SD) or less than − 2 SD, respectively, according to the Swedish reference value for singletons, with adjustment for gestational age and sex [16]. We used the reference values for singletons since there are no reference values available for twins. Inter-twin birthweight discordance was calculated as 100 × (birthweight of the largest twin minus birthweight of the smallest twin)/ birthweight of the largest twin, and was defined as a difference ≥ 25% [17]. Chorionicity was determined by ultrasonography in the first or second trimester.

From this information twin-to-twin time interval, large for gestational age (LGA), small for gestational age (SGA) and inter-twin birthweight discordance was calculated. LGA and SGA was defined as a birthweight of greater than + 2 standard deviations (SD) or less than − 2 SD, respectively, according to the Swedish reference value for singletons, with adjustment for gestational age and sex [16]. We used the reference values for singletons since there are no reference values available for twins. Inter-twin birthweight discordance was calculated as 100 × (birthweight of the largest twin minus birthweight of the smallest twin)/ birthweight of the largest twin, and was defined as a difference ≥ 25% [17]. Chorionicity was determined by ultrasonography in the first or second trimester.

Information regarding umbilical blood gas analysis including pH and base excess (BE), Apgar score, perinatal mortality and morbidity was retrieved from the obstetric computerized medical records system as well as from the Swedish neonatal quality register (SNQ), a national perinatal computerized medical record system in which all perinatal units in Sweden register their patients. After this it was possible to link the information from Obstetrix and SNQ to each other by means of the mother’s 10-digit social security number.

After this it was possible to link the information from Obstetrix and SNQ to each other by means of the mother’s 10-digit social security number.

The twin-to-twin time interval was defined and calculated as the time interval between the delivery of the first twin and the second twin. In order to examine trends of pH, Apgar and neonatal outcome over time, the time interval was divided into periods of 15 min (1–15, 16–30, 31–45, 46–60 and > 60 min). Analyses of twin-to-twin time intervals < 30 min and > 30 min were also performed since some previous studies suggested an upper time limit of 30 min.

Gestational age was based on a routine ultrasound examination, usually made in the second trimester by an expert midwife or obstetrician in ultrasound. Gestational age is calculated in days but presented in weeks + days as this is the most common and generally accepted method.

Primary outcome was defined as a composite measure consisting of any of the following factors:

-

severe metabolic acidosis in umbilical arterial blood gas with pH < 7.

05 and BE < − 12 or pH < 7.00

05 and BE < − 12 or pH < 7.00 -

if no blood gas was available; Apgar < 4 at 5 min

-

perinatal mortality defined as death after onset of labor and within 7 days after birth

-

neonatal mortality as death within 28 days after birth

Secondary outcome was defined as a composite measure consisting of any of the following factors:

-

Apgar < 7 at 5 min

-

acidosis in umbilical arterial blood gas with pH < 7.10

-

interventricular hemorrhage (IVH) verified by ultrasonography and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) within 28 days after birth

-

hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy I-III (HIE)

-

seizure within 7 days after birth

-

septicemia confirmed by positive blood culture within 28 days after birth

-

necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) within 28 days after birth

-

infant respiratory distress syndrome (IRDS) and transient tachypnea of the newborn (TTN)

-

need for assisted ventilation – continuous positive air pressure (CPAP), ventilation by mask or mechanical ventilation

-

If gestational age ≥ 34 weeks; admittance to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) > 7 days

The intrapartum management of all twin deliveries followed the department’s protocol. All twin pregnancies with the first twin in cephalic presentation were planned for vaginal delivery. Regional anesthesia was not mandatory. Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) was applied during active labor, predominately with fetal scalp registration on the first twin and external transducer for the second twin. A specialist in obstetrics and often resident in training as well as two midwives, at least one with experience, were present at delivery. If oxytocin was used it was paused immediately after the delivery of the first twin. Fetal presentation and heartrate of the second twin was examined with digital examination, ultrasonography and CTG. Amniotomy could be performed to enhance contractions if the second twin was engaged. If the second twin was in transverse lie an attempt of external version, to either cephalic or breech presentation, was performed - if needed with intravenous terbutaline or nitroglycerin for uterus relaxation. If lack of effective spontaneous contractions, oxytocin was started and spontaneous vaginal delivery, in head or breech presentation, was preferred.

All twin pregnancies with the first twin in cephalic presentation were planned for vaginal delivery. Regional anesthesia was not mandatory. Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) was applied during active labor, predominately with fetal scalp registration on the first twin and external transducer for the second twin. A specialist in obstetrics and often resident in training as well as two midwives, at least one with experience, were present at delivery. If oxytocin was used it was paused immediately after the delivery of the first twin. Fetal presentation and heartrate of the second twin was examined with digital examination, ultrasonography and CTG. Amniotomy could be performed to enhance contractions if the second twin was engaged. If the second twin was in transverse lie an attempt of external version, to either cephalic or breech presentation, was performed - if needed with intravenous terbutaline or nitroglycerin for uterus relaxation. If lack of effective spontaneous contractions, oxytocin was started and spontaneous vaginal delivery, in head or breech presentation, was preferred. If this failed an internal version and breech extraction were to be considered. Otherwise CS was performed. There was no upper time limit for twin-to-twin time interval and if no complications occurred expectant management was applied. All twin deliveries were conducted at a special delivery ward which has an operating theatre where the CS were performed.

If this failed an internal version and breech extraction were to be considered. Otherwise CS was performed. There was no upper time limit for twin-to-twin time interval and if no complications occurred expectant management was applied. All twin deliveries were conducted at a special delivery ward which has an operating theatre where the CS were performed.

Statistical analysis

For comparison between two groups independent T-tests were used for continuous variables with normal distributions, Mann-Whitney U-test for continuous variables with non-normal distributions and Fisher’s exact test for dichotomous variables. Logistic regression with calculation of odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) and adjustment for gestational age was performed. Subgroup analysis was performed for chorionicity, presentation of the second twin and for twin pregnancies with vaginal deliveries of the second twin excluding cesarean deliveries of the second twin. Spearman’s rho was used for analysis of correlation between umbilical cord arterial pH and twin-to-twin delivery time interval. Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS Statistics 22. All significance tests were two-sided and conducted at the 5% significance level.

Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS Statistics 22. All significance tests were two-sided and conducted at the 5% significance level.

Results

A total of 527 twin deliveries (1054 infants) met the inclusion criteria between January 2008 and December 2014. During this time period there were 71,908 deliveries at the obstetric unit with 1.6% (1123/71908) being twin deliveries between 22 + 1 to 41 + 2 weeks of gestation and with 23.9% (268/1123) elective CS before onset of labour.

The baseline maternal characteristics are described in Table 1. There were 501 twin gestations with known chorionicity, 386 (77%) were dichorionic and 115 (23%) were monochorionic.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics in women with twin deliveries after 32 completed gestational weeks and with vaginal delivery of the first twinFull size table

In 463 (87.9%) deliveries the first twin had a spontaneous delivery in cephalic presentation, 61 (11. 6%) had an assisted vaginal delivery (vacuum extraction/forceps) and although CS is advocated when the first twin is in breech there were three (0.6%) spontaneous vaginal breech deliveries. A total of 35 (6.6%) of the deliveries were combined vaginal/cesarean deliveries. In 411 (78.0%) deliveries the second twin had a spontaneous delivery in cephalic or breech presentation, in 72 (13.7%) an assisted vaginal delivery and in nine cases (1.7%) a breech extraction was performed.

6%) had an assisted vaginal delivery (vacuum extraction/forceps) and although CS is advocated when the first twin is in breech there were three (0.6%) spontaneous vaginal breech deliveries. A total of 35 (6.6%) of the deliveries were combined vaginal/cesarean deliveries. In 411 (78.0%) deliveries the second twin had a spontaneous delivery in cephalic or breech presentation, in 72 (13.7%) an assisted vaginal delivery and in nine cases (1.7%) a breech extraction was performed.

Neonatal characteristics for the first and second twins are shown in Table 2. The median gestational age was 262 days (range 225–286 days) with 200/527 (38.0%) of the deliveries being preterm.

Table 2 Neonatal characteristics in the first and second twins in twin deliveries after 32 completed gestational weeks and with vaginal delivery of the first twinFull size table

The median twin-to-twin time interval was 19 min (range 2–399) with 217 (41.2%) of the second twins being born within 15 min, 143 (27. 1%) second twins were born within 16–30 min, 70 (13.3%) within 31–45 min, 37 (7%) within 46–60 min and 60 (11.4%) after 60 min.

1%) second twins were born within 16–30 min, 70 (13.3%) within 31–45 min, 37 (7%) within 46–60 min and 60 (11.4%) after 60 min.

Composite primary outcome occurred in 2.7% (14/527) in the second twins (Table 3). Of the 14 s twins with a composite primary outcome there were two cases of perinatal mortality. One was a case of intrapartum death after breech extraction at 34 weeks of gestation, where the obstetrician was unable to deliver the head (twin-to-twin time interval 29 min) and one was a second twin born at 33 weeks of gestation (twin-to-twin time interval eight minutes) who developed NEC at four days of age, underwent major surgery and died shortly thereafter. The remaining 12 s twins with composite primary outcomes had severe metabolic acidosis. One of these neonates, born at 38 weeks of gestation, was admitted to NICU for five days because of transient tachypnea of the newborn (TTN).The other 11 recovered within 15 min.

Table 3 Neonatal morbidity in first and second twins in twin deliveries after 32 completed gestational weeks and with vaginal delivery of the first twinFull size table

There were two pregnancies diagnosed with TTTS included in the study. They delivered at 35 + 5 and 37 + 0 weeks of gestation with twin-to-twin time interval of 14 min and 11 min, respectively. The twin delivered at 35 + 5 weeks of gestations was admitted to NICU for 7 days because of suspected infection and seizures, both of which could not be confirmed. No other complications occurred.

They delivered at 35 + 5 and 37 + 0 weeks of gestation with twin-to-twin time interval of 14 min and 11 min, respectively. The twin delivered at 35 + 5 weeks of gestations was admitted to NICU for 7 days because of suspected infection and seizures, both of which could not be confirmed. No other complications occurred.

Twin-to-twin time interval had a significant impact on the composite primary outcome for the second twin (Table 4). Median twin-to-twin time interval was 34 (8–78) min for the second twin with a composite primary outcome and 19 (2–399) min for the second twin without a composite primary outcome (p = 0.028). Lower mean birth weight was associated with a higher rate of primary outcome (p = 0.028) (Table 4).

Table 4 Composite primary (n = 14) and secondary outcome a (n = 92) in the second twin (n = 527) in relation to birth characteristicsFull size table

The composite secondary outcome occurred in 17. 4% (92/527) in the second twin. This was mainly due to pH < 7.10 or the need for assisted ventilation (Table 3).

4% (92/527) in the second twin. This was mainly due to pH < 7.10 or the need for assisted ventilation (Table 3).

Median twin-to-twin time interval, 21 (3–331) min vs. 18 (2–399) min (p = 0.13), had no significant impact on the composite secondary outcome for the second twin. Factors associated with secondary outcomes were lower mean birthweight (p < 0.0001), lower gestational age (p < 0.0001) and inter-twin birthweight discordance ≥25% (p = 0.036) (Table 4).

Composite primary and secondary outcomes are shown in relation to the stratified twin-to-twin time intervals in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1Composite primary* and secondary** outcome in the second twin according to twin-to-twin delivery time interval in minutes

Full size image

When twin-to-twin time intervals were divided into groups of 0 to 30 min and > 30 min, a significant difference could be seen in composite primary outcome (p = 0. 016), severe metabolic acidosis (p = 0.002), mean arterial (p < 0.0001) and mean venous umbilical cord pH (p = 0.016). The outcome was more adverse when the second twin was delivered > 30 min after the first twin (Table 5). The odds ratio (OR) for a composite primary outcome for the second twin delivered > 30 min vs ≤ 30 min was 4.0 (95% CI 1.3–12.2) and 4.1 (95% CI 1.4–12.6) after adjustment for gestational age. Also, when restricting the analysis to twins with a vaginal delivery (n = 492) a higher rate of the composite primary outcome occurred in twins delivered > 30 min after the first twin (p = 0.007), OR 5.3 (95% CI 1.6–17.9) and OR 5.6 (95% CI 1.6–18.9) after adjustment for gestational age.

016), severe metabolic acidosis (p = 0.002), mean arterial (p < 0.0001) and mean venous umbilical cord pH (p = 0.016). The outcome was more adverse when the second twin was delivered > 30 min after the first twin (Table 5). The odds ratio (OR) for a composite primary outcome for the second twin delivered > 30 min vs ≤ 30 min was 4.0 (95% CI 1.3–12.2) and 4.1 (95% CI 1.4–12.6) after adjustment for gestational age. Also, when restricting the analysis to twins with a vaginal delivery (n = 492) a higher rate of the composite primary outcome occurred in twins delivered > 30 min after the first twin (p = 0.007), OR 5.3 (95% CI 1.6–17.9) and OR 5.6 (95% CI 1.6–18.9) after adjustment for gestational age.

Full size table

Stratified into chorionicity, the composite primary outcome occurred in 0/87 monochorionic twins delivered within 0 to 30 min and in 3. 6% (1/28) delivered > 30 min after the first twin (p = 0.243). Composite secondary outcome occurred in 16.1% (14/87) and 21.4% (6/28) monochorionic twins delivered within 0–30 min and > 30 min after the first twin, respectively (p = 0.569). The composite primary outcome occurred in 1.6% (4/256) and 6.2% (8/130) dichorionic twins delivered within 0–30 min and > 30 min after the first twin, respectively (p = 0.025). There was no significant difference in composite secondary outcome for dichorionic twins delivered within 30 min or > 30 min after the first twin.

6% (1/28) delivered > 30 min after the first twin (p = 0.243). Composite secondary outcome occurred in 16.1% (14/87) and 21.4% (6/28) monochorionic twins delivered within 0–30 min and > 30 min after the first twin, respectively (p = 0.569). The composite primary outcome occurred in 1.6% (4/256) and 6.2% (8/130) dichorionic twins delivered within 0–30 min and > 30 min after the first twin, respectively (p = 0.025). There was no significant difference in composite secondary outcome for dichorionic twins delivered within 30 min or > 30 min after the first twin.

There was no difference in composite primary or secondary outcomes according to presentation (cephalic or breech) and intertwin delivery interval.

Figure 2 shows the correlation between arterial umbilical pH and twin-to-twin interval time.

Fig. 2Umbilical cord arterial pH in the second twin related to twin-to-twin delivery time interval in minutes

Full size image

Most of the CS to deliver the second twin occurred in the group with a twin-to-twin time interval > 30 min 28/35 vs. 7/35 ≤ 30 min, p < 0.0001). The indications for CS to deliver the second twin were fetal distress (n = 15), malpresentation (n = 9), uterine inertia (n = 5), cord prolapse (n = 3), placental separation (n = 1), failed internal version (n = 1) and failed external version (n = 1). The mode of delivery for the second twin in relation to twin-to-twin time interval is shown in Fig. 3.

7/35 ≤ 30 min, p < 0.0001). The indications for CS to deliver the second twin were fetal distress (n = 15), malpresentation (n = 9), uterine inertia (n = 5), cord prolapse (n = 3), placental separation (n = 1), failed internal version (n = 1) and failed external version (n = 1). The mode of delivery for the second twin in relation to twin-to-twin time interval is shown in Fig. 3.

Mode of delivery of the second twin according to twin-to-twin delivery time interval in minutes

Full size image

Discussion

This study reaffirms previous evidence that the second twin is at greater risk of metabolic acidosis and neonatal morbidity than the first twin [3, 6, 12, 18]. We were able to confirm that there is an association, but not a clear causality, with the twin-to-twin time interval [11, 12]. Only 14 of the second twins had a composite primary outcome but they had significantly longer median twin-to-twin time intervals than second twins without a composite primary outcome. Second twins with a twin-to-twin time interval of more than 30 min had higher rates of primary composite outcomes than second twins born within 30 min. No differences were seen in composite secondary outcomes that related to twin-to-twin time intervals.

Second twins with a twin-to-twin time interval of more than 30 min had higher rates of primary composite outcomes than second twins born within 30 min. No differences were seen in composite secondary outcomes that related to twin-to-twin time intervals.

Previous studies have come to varying results on the possible impact of twin-to-twin time interval on neonatal outcome for the second twin [9, 11, 13]. Most studies imply that considering the fact that umbilical cord pH decreases with longer duration of the delivery of the second twin, it is important to apply active management to keep the twin-to-twin time interval as short as possible, ideally below 30 min. Leung found that pH deteriorates faster in the second twin than in the first twin [19], and recommend a fast delivery of the second twin. In this study we found a significantly higher rate of metabolic acidosis and lower mean arterial pH in second twins born after a twin-to-twin time interval of 30 min than in second twins born within 30 min. However, there was no difference in Apgar score, the differences in pH were small and most of the second twins with metabolic acidosis recovered quickly. The two cases of perinatal mortality occurred in second twins born within 30 min. Furthermore, there was no difference in neonatal morbidity, and admission to NICU was not associated with twin-to-twin time interval.

However, there was no difference in Apgar score, the differences in pH were small and most of the second twins with metabolic acidosis recovered quickly. The two cases of perinatal mortality occurred in second twins born within 30 min. Furthermore, there was no difference in neonatal morbidity, and admission to NICU was not associated with twin-to-twin time interval.

Although the small difference in pH-levels in umbilical blood gas (7.23 vs. 7.20) for second twins delivered within or after 30 min may not have a clinical impact, other findings may justify an upper time limit on the interval between twin-to-twin deliveries. In this study there was a combined vaginal-cesarean delivery in 35 cases (6.6%), a rate consistent with other findings [20]. Cesarean delivery of the second twin is considered to be the least desirable mode of delivery and should be avoided [4, 6] due to possible complications for both mother and child. Studies have shown a worsened outcome, with increased physical and psychological maternal morbidity [18, 21] as well as higher neonatal morbidity [4, 6]. Twenty eight of these 35 combined vaginal-cesarean deliveries occurred in the twin-to-twin time interval of more than 30 min, 17 in the interval of more than 60 min. This is in agreement with previous studies that have found a six-fold increased risk of combined vaginal-cesarean delivery after 30 min and an eight-fold increased risk after 60 min [4]. Our study does not show any differences in primary and secondary neonatal outcome related to CS. However, maternal physical and psychological morbidity was not analyzed.

Twenty eight of these 35 combined vaginal-cesarean deliveries occurred in the twin-to-twin time interval of more than 30 min, 17 in the interval of more than 60 min. This is in agreement with previous studies that have found a six-fold increased risk of combined vaginal-cesarean delivery after 30 min and an eight-fold increased risk after 60 min [4]. Our study does not show any differences in primary and secondary neonatal outcome related to CS. However, maternal physical and psychological morbidity was not analyzed.

The fact that most combined deliveries occurred in the group where the twin-to-twin delivery time interval was more than 30 min, is in itself not surprising. If the second twin is not spontaneously delivered, the risk of assisted delivery increases over time. Previous studies have found that combined vaginal-cesarean twin delivery can be avoided with active management in the second stage of delivery of the second twin [22]. Active management is generally considered to be internal podalic version (IPV) followed by breech extraction of the non-vertex and the unengaged vertex second twin. Previous findings suggest that IPV may be more successful than external version when it comes to vaginal delivery, and with better neonatal outcome [1, 22,23,24]. External version has been found to be associated with complications such as fetal distress, cord prolapse and compound presentations [25]. However, this maneuver was only performed in 10 cases, of which nine were successful. Active management is not praxis at our unit and unfortunately the IPV maneuver is therefore seldom taught to junior obstetricians. A decreasing rate of IPV and breech extraction, and an increased rate of CS, has also been seen in recent years in several other countries around the world [24]. In the Danish register study a better neonatal outcome was seen for the second twin after IPV and extraction than after a CS [24]. If an upper time limit is to be advocated, the management of the delivery of the second twin would need to be more active than what is recommended at our unit today. This may lead to an increase in use of oxytocin, instrumental deliveries (VE/forceps), breech extraction of a second non vertex twin and IPV and breech extraction of a second vertex non-engaged twin.

Previous findings suggest that IPV may be more successful than external version when it comes to vaginal delivery, and with better neonatal outcome [1, 22,23,24]. External version has been found to be associated with complications such as fetal distress, cord prolapse and compound presentations [25]. However, this maneuver was only performed in 10 cases, of which nine were successful. Active management is not praxis at our unit and unfortunately the IPV maneuver is therefore seldom taught to junior obstetricians. A decreasing rate of IPV and breech extraction, and an increased rate of CS, has also been seen in recent years in several other countries around the world [24]. In the Danish register study a better neonatal outcome was seen for the second twin after IPV and extraction than after a CS [24]. If an upper time limit is to be advocated, the management of the delivery of the second twin would need to be more active than what is recommended at our unit today. This may lead to an increase in use of oxytocin, instrumental deliveries (VE/forceps), breech extraction of a second non vertex twin and IPV and breech extraction of a second vertex non-engaged twin. Without adequate knowledge of, and training in, active management the clinical outcome of such a change in strategy is unknown.

Without adequate knowledge of, and training in, active management the clinical outcome of such a change in strategy is unknown.

Our unit is able to monitor both twins simultaneously and continuously. We also have 24-h in-house pediatric and anesthesia coverage and immediate availability for performing emergency CS. This may partly explain the few primary outcomes. Because of this the results of this study cannot be extrapolated to other units with other preconditions. It is important for every unit delivering twins to look at their results and from this stipulate guidelines that are in accordance with their preconditions. Factors such as the level of experience of the obstetrician in charge at the delivery, the skill of intrauterine manipulation and the wish of the women giving birth, may all influence the twin-to-twin delivery time interval. Results from the Twin Birth Study showed that the maternal preference is for vaginal birth, therefore skills need to be maintained [26].

The limitations of the study are, as in all retrospective studies, that we have no control over available information. A rather large number of the twins had missing pH values (23% in the first twin and 19.2% in the second twin). However, analysis was made of complete data on more than 400 twins in each group. Despite a relatively large sample size there were few primary outcomes and regression analysis could not be performed for all potential confounders. The results are to be analyzed in the light of the relatively high gestational age of the sample. Twin gestations delivered before 32 + 0 weeks of gestation are complicated per see and excluding them may result in a selected sample. Including them might on the other hand result in morbidity outcomes that are not related to twin-to-twin delivery interval but prematurity in itself. There may also be other important confounders that we did not have information on. A randomized controlled trial with different twin-to-twin time intervals would be the optimal study design, but would probably be impossible to perform. Further, in this study we have not addressed the impact on maternal morbidity as postpartum hemorrhage and length of hospital stay etc.

A rather large number of the twins had missing pH values (23% in the first twin and 19.2% in the second twin). However, analysis was made of complete data on more than 400 twins in each group. Despite a relatively large sample size there were few primary outcomes and regression analysis could not be performed for all potential confounders. The results are to be analyzed in the light of the relatively high gestational age of the sample. Twin gestations delivered before 32 + 0 weeks of gestation are complicated per see and excluding them may result in a selected sample. Including them might on the other hand result in morbidity outcomes that are not related to twin-to-twin delivery interval but prematurity in itself. There may also be other important confounders that we did not have information on. A randomized controlled trial with different twin-to-twin time intervals would be the optimal study design, but would probably be impossible to perform. Further, in this study we have not addressed the impact on maternal morbidity as postpartum hemorrhage and length of hospital stay etc.

Conclusions

An association, but not necessarily causality, between lengths of twin-to-twin time intervals and primary outcome in second twins, was found. Based on the findings of this study an upper time limit for twin-to-twin time intervals may be justified, due to the increased rate of metabolic acidosis and combined vaginal-cesarean deliveries associated with prolonged intervals between deliveries. However, the optimal twin-to-twin time interval needs further study before any recommendation can be made. Furthermore, active second stage management of the second twin needs an obstetrician with skills in the requisite maneuvers, so adequate training of the next generation of obstetricians is therefore necessary.

Abbreviations

- BE:

-

Base excess

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CPAP:

-

Continuous positive air pressure

- CS:

-

Cesarean section

- HIE:

-

Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy

- IPV:

-

Internal podalic version

- IRDS:

-

Irregular respiratory distress syndrome

- IVH:

-

Intraventricular hemorrhage

- LGA:

-

Large for gestational

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NEC:

-

Necrotizing enterocolitis

- NICU:

-

Neonatal intensive care unit

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SGA:

-

Small for gestational age

- SNQ:

-

Swedish neonatal quality register

- TTN:

-

Transient tachypnea of the newborn

- TTTS:

-

Twin-twin transfusion syndrome

References

Arabin B, Kyvernitakis I. Vaginal delivery of the second nonvertex twin: avoiding a poor outcome when the presenting part is not engaged. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(4):950–4.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Barrett JF, Ritchie WK. Twin delivery. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;16(1):43–56.

CAS Article PubMed Google Scholar

Armson BA, O'Connell C, Persad V, Joseph KS, Young DC, Baskett TF. Determinants of perinatal mortality and serious neonatal morbidity in the second twin. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(3 Pt 1):556–64.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Cruikshank DP. Intrapartum management of twin gestations. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(5):1167–76.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Kiely JL. The epidemiology of perinatal mortality in multiple births. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1990;66(6):618–37.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rossi AC, Mullin PM, Chmait RH. Neonatal outcomes of twins according to birth order, presentation and mode of delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2011;118:523–32.

CAS Article PubMed Google Scholar

Barrett JF, Hannah ME, Hutton EK, Willan AR, Allen AC, Armson BA, Gafni A, Joseph KS, Mason D, Ohlsson A, et al. A randomized trial of planned cesarean or vaginal delivery for twin pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1295–305.

CAS Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Erdemoglu E, Mungan T, Tapisiz OL, Ustunyurt E, Caglar E. Effect of inter-twin delivery time on Apgar scores of the second twin.

Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43(3):203–6.

Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43(3):203–6.Article PubMed Google Scholar

Stein W, Misselwitz B, Schmidt S. Twin-to-twin delivery time interval: influencing factors and effect on short-term outcome of the second twin. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87(3):346–53.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Smith GC, Shah I, White IR, Pell JP, Dobbie R. Mode of delivery and the risk of delivery-related perinatal death among twins at term: a retrospective cohort study of 8073 births. BJOG. 2005;112(8):1139–44.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Leung TY, Tam WH, Leung TN, Lok IH, Lau TK. Effect of twin-to-twin delivery interval on umbilical cord blood gas in the second twins. BJOG. 2002;109(1):63–7.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Hjorto S, Nickelsen C, Petersen J, Secher NJ. The effect of chorionicity and twin-to-twin delivery time interval on short-term outcome of the second twin. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27(1):42–7.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

McGrail CD, Bryant DR. Intertwin time interval: how it affects the immediate neonatal outcome of the second twin. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1420–2.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Rayburn WF, Lavin JP Jr, Miodovnik M, Varner MW. Multiple gestation: time interval between delivery of the first and second twins. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;63(4):502–6.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Committee on Practice B-O, Society for Maternal-Fetal M. Practice bulletin no. 169: multifetal gestations: twin, triplet, and higher-order multifetal pregnancies.

Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):e131–46.

Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):e131–46.Article Google Scholar

Marsal K, Persson PH, Larsen T, Lilja H, Selbing A, Sultan B. Intrauterine growth curves based on ultrasonically estimated foetal weights. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85(7):843–8.

CAS Article PubMed Google Scholar

D'Antonio F, Khalil A, Dias T, Thilaganathan B, Southwest Thames Obstetric Research C. Weight discordance and perinatal mortality in twins: analysis of the Southwest Thames obstetric research collaborative (STORK) multiple pregnancy cohort. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41(6):643–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Wolff K. Excessive use of cesarean section for the second twin? Gynecol Obstet Investig. 2000;50(1):28–32.

CAS Article Google Scholar

Leung TY, Lok IH, Tam WH, Leung TN, Lau TK. Deterioration in cord blood gas status during the second stage of labour is more rapid in the second twin than in the first twin. BJOG. 2004;111(6):546–9.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Fox NS, Silverstein M, Bender S, Klauser CK, Saltzman DH, Rebarber A. Active second-stage management in twin pregnancies undergoing planned vaginal delivery in a U.S. population. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 Pt 1):229–33.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Rabinovici J, Barkai G, Reichman B, Serr DM, Mashiach S. Randomized management of the second nonvertex twin: vaginal delivery or cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156(1):52–6.

CAS Article PubMed Google Scholar

Schmitz T, Carnavalet Cde C, Azria E, Lopez E, Cabrol D, Goffinet F.

Neonatal outcomes of twin pregnancy according to the planned mode of delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):695–703.

Neonatal outcomes of twin pregnancy according to the planned mode of delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):695–703.Article PubMed Google Scholar

Chauhan SP, Roberts WE, McLaren RA, Roach H, Morrison JC, Martin JN Jr. Delivery of the nonvertex second twin: breech extraction versus external cephalic version. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173(4):1015–20.

CAS Article PubMed Google Scholar

Jonsdottir F, Henriksen L, Secher NJ, Maaloe N. Does internal podalic version of the non-vertex second twin still have a place in obstetrics? A Danish national retrospective cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(1):59–64.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gocke SE, Nageotte MP, Garite T, Towers CV, Dorcester W. Management of the nonvertex second twin: primary cesarean section, external version, or primary breech extraction.

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161(1):111–4.

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161(1):111–4.CAS Article PubMed Google Scholar

Murray-Davis B, McVittie J, Barrett JF, Hutton EK, Twin Birth Study Collaborative G. Exploring Women's preferences for the mode of delivery in twin gestations: results of the twin birth study. Birth. 2016;43(4):285–92.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Nils-Gunnar Pehrsson for statistical advice and Gwyneth Olofsson for language revision.

Funding

Financial support was received from the Health & Medical Care Committee of the Regional Executive Board, Region Västra Götaland (VGFOUREG) and through an agreement concerning research and the education of doctors (ALFGBG-70940). Funding bodies had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article can be provided on reasonable request from the corresponding author if further ethical permission is obtained.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Institute of Clinical Sciences at Sahlgrenska Academy, Gothenburg University, Diagnosvägen 15, 416 85, Gothenburg, Sweden

L. Lindroos, L. Ladfors & U.-B. Wennerholm

Department of Pediatrics, Institute of Clinical Sciences at Sahlgrenska Academy, Gothenburg University, Gothenburg, Sweden

A. Elfvin

Authors

- L. Lindroos

View author publications

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- A. Elfvin

View author publications

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- L.

Ladfors

LadforsView author publications

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- U.-B. Wennerholm

View author publications

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors (LLi, AE, LLa and UBW) have contributed to study conception, design, analysis and interpretation of data. LLa collected all data from the medical records. LLi wrote the manuscript in collaboration with AE, LLa and UBW. All authors have revised the manuscript and approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to L. Lindroos.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical committee at University of Gothenburg, Sweden, Dnr 727–16. Informed consent was waived by the ethics committee.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was not required, as data were anonymized and informed consent was waived by the ethics committee.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Giving birth to twins | Pregnancy Birth and Baby

Twins are more likely to be born early, often before 38 weeks, so it's important to understand your birth options. Less than half of all twin pregnancies last beyond 37 weeks.

Less than half of all twin pregnancies last beyond 37 weeks.

Because of the likelihood that your babies will be born early, there is a good chance one or both of them will spend some time in special care.

As twins are often born prematurely, it's a good idea to discuss birth options with your midwife or doctor early in your pregnancy.

You should also discuss where you would like to give birth. You will most likely be advised to give birth in a hospital because there's a higher chance of complications with a twin birth.

It's common for more medical staff to be involved in the birth of twins, such as a midwife, an obstetrician and two paediatricians - one for each baby.

While the process of labour is the same as when single babies are born, twin babies are more closely monitored. To do this, an electronic monitor and a scalp clip might be fitted on the first baby once your waters have broken. You will be given a drip in case it is needed later.

Vaginal birth

About one third of all twins are born vaginally and the process is similar to that of giving birth to a single baby. If you're planning a vaginal delivery, it's usually recommended that you have an epidural for pain relief. This is because, if there are problems, it's easier and quicker to assist the delivery when the mother already has good pain relief.

If you're planning a vaginal delivery, it's usually recommended that you have an epidural for pain relief. This is because, if there are problems, it's easier and quicker to assist the delivery when the mother already has good pain relief.

If the first twin is in a head down position (cephalic), it's usual to consider having a vaginal birth. However, there may be other medical reasons why this would not be possible. If you have had a previous caesarean section, it's usually not recommended you have a vaginal birth with twins.

If you have a vaginal birth, you may need an assisted birth, which is when a suction cup (ventouse) or forceps are used to help deliver the babies.

Once the first baby is born, the midwife or doctor will check the position of the second baby by feeling your abdomen and doing a vaginal examination. If the second baby is in a good position, the waters will be broken and this baby should be born soon after the first as the cervix is already fully dilated. If contractions stop after the first birth, hormones will be added to the drip to restart them.

If contractions stop after the first birth, hormones will be added to the drip to restart them.

Caesarean section

You may choose to have an elective caesarean from the outset of your pregnancy, or your doctor may recommend a caesarean section later in the pregnancy as a result of potential complications. You’re nearly twice as likely to have a caesarean if you’re giving birth to twins than if you’re giving birth to a single baby.

The babies' position may determine whether they need to be delivered by caesarean section or not. If the presenting baby - the one that will be born first - is in a breech position (feet, knees or buttocks first), or if one twin is lying in a transverse position (with its body lying sideways), you will need to have a caesarean section.

Some conditions also mean you will need a caesarean section; for example if you have placenta praevia (a low-lying placenta) or if your twins share a placenta.

If you have previously had a very difficult delivery with a single baby, you may be advised to have a caesarean section with twins. Even if you plan a vaginal birth, you may end up having an emergency caesarean section.

Even if you plan a vaginal birth, you may end up having an emergency caesarean section.

This could be because:

- one or both babies become distressed

- the umbilical cord prolapses (falls into the birth canal ahead of the baby)

- your blood pressure is going up

- the labour is progressing too slowly

- assisted delivery doesn't work

In very rare cases, you may deliver one twin vaginally and then require a caesarean section to deliver the second twin if it becomes distressed.

After the birth

After the birth, your midwife will examine the placenta to determine what type of twins you have. Twins can either be fraternal or identical.

If your babies need special care

Depending on where you plan to give birth, you may need to go to another hospital with appropriate facilities if complications in your pregnancy indicate you're likely to have an early delivery. This may not be near to home, so make sure to check there are enough beds for both your babies in the neonatal unit.

Ask if your chosen hospital has a transitional care unit or a special care nursery. These are places that allow mothers to care for their babies if they need special care but not intensive care. These hospitals are more likely to be able to keep you and your babies in the same place.

You might also want to ask if your hospital has cots that allow co-bedding (where your babies sleep in a single cot), if this is appropriate and if you want your babies to sleep together.

If you have one baby in the hospital and one at home, you will need to think about splitting your time between the two. When you visit your baby in hospital, ask if you can bring their twin and if co-bedding is allowed during visits.

If you want to breastfeed and only one twin can feed effectively, you may need to express milk to feed the twin who is having trouble feeding. You may then need to put the twin who can feed on the breast to encourage milk production in order to get enough milk to feed both babies.

Check if your hospital offers support from a community neonatal nurse, which would allow for you and your babies to leave hospital earlier, for example if your baby is still tube-fed.

When you go to clinics for follow-up appointments, it's a good idea to ask not to be booked into early morning appointments. Getting out of the house with two babies, particularly if one is unwell, can be difficult.

For more information and support, visit Twins Research Australia.

Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Multiple pregnancy

Author: Mikheeva Natalia Grigoryevna, Malyshok magazine

A multiple pregnancy is a pregnancy in which two or more fetuses develop simultaneously in the uterus. Multiple pregnancy occurs in 0.4 - 1.6% of all pregnancies. Recently, there has been an obvious trend towards an increase in the incidence of such pregnancies due to the active use of assisted reproduction technologies, including in vitro fertilization (IVF).

Types of multiple pregnancies

Children born in multiple pregnancies are called TWINS. There are two main types of twins: monozygotic (identical, homologous, identical, similar) and dizygotic (fraternal, heterologous, different). African countries have the highest twin birth rate, Europe and the USA have an average rate, and Asian countries have a low rate.

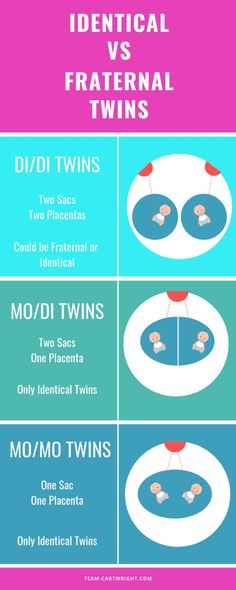

Dizygotic (fraternal) twins are more common (in 66-75% of all twins). The birth rate of dizygotic twins varies from 4 to 50 per 1000 births. Dizygotic twins occur when two separate eggs are fertilized. The maturation of two or more eggs can occur both in one ovary and in two. The predisposition to develop dizygotic twins may be maternally inherited. Dizygotic twins can be either same-sex or opposite-sex, they look like each other like ordinary brothers and sisters. With fraternal twins, two placentas are always formed, which can be very close, even touching, but they can always be separated. Two fruit spaces (i.e., fetal bladders or two “houses”) are separated from each other by a septum consisting of two chorionic and two amniotic membranes. Such twins are called dizygotic dichorionic diamniotic twins.

Two fruit spaces (i.e., fetal bladders or two “houses”) are separated from each other by a septum consisting of two chorionic and two amniotic membranes. Such twins are called dizygotic dichorionic diamniotic twins.

Monozygotic (identical) twins are formed as a result of the separation of one fetal egg at various stages of its development. The frequency of birth of monozygotic twins is 3-5 per 1000 births. The division of a fertilized egg into two equal parts can occur as a result of a delay in implantation (immersion of the embryo in the uterine mucosa) and oxygen deficiency, as well as due to a violation of the acidity and ionic composition of the medium, exposure to toxic and other factors. The emergence of monozygotic twins is also associated with the fertilization of an egg that had two or more nuclei. If the separation of the fetal egg occurs in the first 3 days after fertilization, then monozygotic twins have two placentas and two amniotic cavities, and are called monozygotic diamniotic dichoriones (Fig. A). If the division of the ovum occurs between 4 - 8 days after fertilization, then two embryos will form, each in a separate amniotic sac. Two amniotic sacs will be surrounded by a common chorionic membrane with one placenta for two. Such twins are called monozygotic diamniotic monochorionic twins (Fig. B). If division occurs by 9- 10th day after fertilization, then two embryos are formed with a common amniotic sac and placenta. Such twins are called monozygotic monoamniotic monochorionic (Fig. B) If the egg is separated at a later date on the 13th - 15th day after conception, the separation will be incomplete, which will lead to the appearance of conjoined (undivided, Siamese) twins. This type is quite rare, approximately 1 observation in 1500 multiple pregnancies or 1: 50,000 - 100,000 newborns. Monozygotic twins are always the same sex, have the same blood type, have the same eye color, hair, skin texture of the fingers, and are very similar to each other.

A). If the division of the ovum occurs between 4 - 8 days after fertilization, then two embryos will form, each in a separate amniotic sac. Two amniotic sacs will be surrounded by a common chorionic membrane with one placenta for two. Such twins are called monozygotic diamniotic monochorionic twins (Fig. B). If division occurs by 9- 10th day after fertilization, then two embryos are formed with a common amniotic sac and placenta. Such twins are called monozygotic monoamniotic monochorionic (Fig. B) If the egg is separated at a later date on the 13th - 15th day after conception, the separation will be incomplete, which will lead to the appearance of conjoined (undivided, Siamese) twins. This type is quite rare, approximately 1 observation in 1500 multiple pregnancies or 1: 50,000 - 100,000 newborns. Monozygotic twins are always the same sex, have the same blood type, have the same eye color, hair, skin texture of the fingers, and are very similar to each other.

Twin births occur once in 87 births, triplets - once in 87 2 (6400) twins, quadruples - once in 87 3 (51200) triplets, etc. (according to the Gallin formula). The origin of triplets, quadruplets, and more twins varies. So, triplets can be formed from three separate eggs, from two or one egg. They can be monozygotic and heterozygous. Quadruples can also be identical and fraternal.

(according to the Gallin formula). The origin of triplets, quadruplets, and more twins varies. So, triplets can be formed from three separate eggs, from two or one egg. They can be monozygotic and heterozygous. Quadruples can also be identical and fraternal.

Features of the course of multiple pregnancy

In case of multiple pregnancies, the woman's body is subject to increased requirements. All organs and systems function with great tension. In connection with the displacement of the diaphragm by the enlarged uterus, the activity of the heart becomes difficult, shortness of breath, fatigue occur. Enlargement of the uterus, especially towards the end of pregnancy, leads to compression of the internal organs, which is manifested by impaired bowel function, frequent urination, and heartburn. Almost 4-5 times more often there is the development of preeclampsia, which is characterized by an earlier onset, a protracted and more severe clinical course, often combined with acute pyelonephritis of pregnant women. Due to the increased need and consumption of iron, iron deficiency anemia often develops in pregnant women. Significantly more often than with a singleton pregnancy, complications such as bleeding during pregnancy and childbirth, anomalies in labor, and a low location of the placenta are observed. Often, with multiple pregnancies, abnormal positions of the fetus occur. One of the most common complications in multiple pregnancy is its premature termination. Preterm birth is observed in 25-50% of cases of such pregnancies.

Due to the increased need and consumption of iron, iron deficiency anemia often develops in pregnant women. Significantly more often than with a singleton pregnancy, complications such as bleeding during pregnancy and childbirth, anomalies in labor, and a low location of the placenta are observed. Often, with multiple pregnancies, abnormal positions of the fetus occur. One of the most common complications in multiple pregnancy is its premature termination. Preterm birth is observed in 25-50% of cases of such pregnancies.

The development of term twins is normal in most cases. However, their body weight is usually less (by 10% or more) than in singleton pregnancies. With twins, the weight of children at birth less than 2500 g is observed in 40-60%. The low weight of twins is most often due to insufficiency of the uteroplacental system, which is not able to adequately provide several fetuses with nutrients, trace elements and oxygen. The consequence of this is a delay in the development of the fetus, which is a common occurrence in multiple pregnancies. The mass of twins, respectively, decreases in proportion to their number (triplets, quadruplets, etc.).

The mass of twins, respectively, decreases in proportion to their number (triplets, quadruplets, etc.).

With monochorionic twins in the placenta, anastomoses are often formed between the vascular systems of the fetus, which can lead to a serious complication - the syndrome of feto-fetal transfusion. In this case, there is a redistribution of blood from one fetus to another, the so-called "stealing". The severity of feto-fetal transfusion (mild, moderate, severe) depends on the degree of redistribution of blood through the anastomoses, which vary in size, number and direction.

Diagnosis in multiple pregnancy

The most reliable method for diagnosing multiple pregnancy is ultrasound, which allows not only early diagnosis of multiple pregnancy, but also to determine the position and presentation of fetuses, localization, structure and number of placentas, the number of amniotic cavities, the volume of amniotic fluid, congenital malformations and antenatal fetal death, the state of the fetus from a functional point of view, the nature of the uteroplacental and fetal-placental blood flow.

In multiple pregnancies, due to the higher risk of complications, ultrasound monitoring is performed more frequently than in singleton pregnancies. With dizygotic twins, about once every 3-4 weeks, with monozygotic twins - once every 2 weeks.

In addition, examinations and control of clinical tests are carried out with great care, and CTG is regularly recorded from 28 weeks of pregnancy.

Birth management

Indications for caesarean section associated with multiple pregnancies are triplets (quadruple), the transverse position of both or one of the fetuses, breech presentation of both fetuses or the first of them, and not associated with multiple pregnancy - fetal hypoxia, anomalies labor activity, prolapse of the umbilical cord, extragenital pathology of the mother, severe gestosis, placenta previa and abruption, etc.

-

ECO

In the department of assisted reproductive technologies of the Maternity Hospital No. 2

2

, IVF is performed at the expense of the Republican budget for couples

who have received a positive decision from the Minsk city or regional commissions to provide one free IVF attempt.

No drug supply problem. There is no waiting list. -

Farewoman

-

Individual care for patients

-

Ultrasound diagnostics

Curious facts are

0

, how many are the Geminis? up to 80 million pairs of twins.

The number of twins born in relation to the total number of newborns in different countries and on different continents is different, but in general the trend is such that it continues to grow. Compared with the 60s, the percentage of twins has increased from 1.18 to 2.78, that is, almost 2.5 times.

The largest number of children

The largest number of children born to one mother, according to official data, is 69. According to reports made in 1782, between 1725 and 1765. The wife of a Russian peasant Fyodor Vasiliev gave birth 27 times, giving birth to twins 16 times, triplets 7 times and 4 twins 4 times. Of these, only 2 children died in infancy.

The wife of a Russian peasant Fyodor Vasiliev gave birth 27 times, giving birth to twins 16 times, triplets 7 times and 4 twins 4 times. Of these, only 2 children died in infancy.

The most prolific mother of our contemporaries is considered to be Leontina Albina (or Alvina) of San Antonio, Chile, who at 1943-81 years gave birth to 55 children. As a result of the first 5 pregnancies, she gave birth to triplets, and exclusively male.

Most birthed

The record 38 births are said to be Elizabeth Greenhillies Abbots-Langley, c. Hertfordshire, UK. She had 39 children - 32 daughters and 7 sons.

The largest number of multiple births in one family

Maddalena Pomegranate from Italy (b. 1839) had triplets born 15 times.

There is also information about the birth on May 29, 1971 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, and in May 1977 in Bagarhat, Bangladesh, 11 twins. In both cases, no child survived.

Most fertile pregnancies

Dr. Gennaro Montanino, Rome, Italy, claimed to have removed, in July 1971, the embryos of 10 girls and 5 boys from the uterus of a 35-year-old woman who was 4 months pregnant. This unique case of 15-fertility was the result of infertility pills.

Gennaro Montanino, Rome, Italy, claimed to have removed, in July 1971, the embryos of 10 girls and 5 boys from the uterus of a 35-year-old woman who was 4 months pregnant. This unique case of 15-fertility was the result of infertility pills.

9 children - the largest number in one pregnancy - were born on June 13, 1971 by Geraldine Broadrick in Sydney, Australia. 5 boys and 4 girls were born: 2 boys were stillborn, and none of the rest survived more than 6 days.

The birth of 10 twins (2 boys and 8 girls) is known from reports from Spain (1924), China (1936) and Brazil (April 1946).

The father with many children

The largest father in the history of Russia is Yakov Kirillov, a peasant from the village of Vvedensky, who in 1755 was presented to the court in connection with this (he was then 60 years old). The first wife of a peasant gave birth to 57 children: 4 times four, 7 times three, 9once twice and 2 times once. The second wife gave birth to 15 children. Thus, Yakov Kirillov had 72 children from two wives.

Thus, Yakov Kirillov had 72 children from two wives.

Longest Birth Intervals for Multiple Pregnancies

Peggy Lynn of Huntington Pennsylvania, USA, gave birth to a girl, Hanna, on November 11, 1995, and the second of the twins, Erika, only 84 days later (February 2, 1996).

Siamese twins

United twins became known as "Siamese" after Chang and Eng Bunkers were born fused in the area of the sternum on May 11, 1811 in the Maeklong region of Siam (Thailand). They married Sarah and Adelaide Yates of pc. North Carolina, USA, and had 10 and 12 children, respectively. They died in 1874, and with a difference of 3 hours.

The science of twins - gemellology.

"Secret language"

Twins often talk to each other in a language that others do not understand. This phenomenon is called cryptophasia.

Left-handed twins

18-22% of left-handed twins (for non-twins this percentage is 10).

Parallel Lives Separated twins reunite after 39 years.

A striking resemblance glorified them all over the world: People: From life: Lenta.ru

A striking resemblance glorified them all over the world: People: From life: Lenta.ru Fate separated newborn twins from the American town of Pikva for 39 years. The brothers did not know anything about each other, but seemed to live according to the same scenario. They fell in love with similar women, gave their pets the same nicknames, shared common tastes and preferences between two, even rested on the same beach. "Lenta.ru" revealed the details of their incredible life.

Back in 1939, a 15-year-old American woman gave birth to identical twins in a hospital in the American town of Piqua, Ohio. The young mother clearly understood that she could not afford to feed the boys alone, and gave them up for adoption.

Three weeks later, the newborns were separated. One of the twins was given to Ernest and Sarah Springer, a married couple who also lived in Pikva. And two weeks later, his brother got into the family of Jess and Lucille Lewis from the city of Lyme, located nearby. Both boys, without saying a word, were given the name Jim.

Both boys, without saying a word, were given the name Jim.

The adoptive parents never met the mother of the twins and were initially convinced that one of the brothers had died at birth. The truth surfaced when the children were one year and four months old. During the paperwork for adoption, Lucille Lewis accidentally overheard the conversation of the district court employees. They whispered that the second twin had also been christened Jim. “All these years I knew that he was alive, and often wondered if he had a roof over his head and if he was all right,” she recalled.

Jim Lewis learned about his brother from her when he was a child, but decided to find him only at the age of 39. “I don’t know why then,” he admitted. “It just seemed like the time had come.” For information about the twin, he turned to the court, which dealt with adoption issues. “They told me that they would try to find out the contacts of the twin and write him a letter. They wanted to make sure he wanted to meet me,” he recalled.

Mirror Lives

A month after going to court, Lewis got a call. An unfamiliar voice from the other end of the wire asked: "Are you my brother?" Lewis immediately realized who he was talking to and blurted out: “Yes!” The twins met five days later.

Related materials:

“I remember driving from Lima to Dayton, where Jim was waiting for me,” Lewis shared his memories. - It was our first meeting. I was terribly nervous, my palms were indecently sweaty. But when we met, I calmed down. There was no feeling that a stranger was sitting in front of me.

The brothers were surprised to find that they have the same name not only. They preferred the same brand of cigarettes, drank Pepsi, liked Miller Lite beer equally, and drove blue Chevrolets. The twins went to rest on the same beach in Florida. Both suffered from migraines and had a bad habit of biting their nails. Each of them liked to hide romantic notes for his wife in the house.

The coincidences didn't end there. It turned out that even the sons of their adoptive parents were named the same - Larry, and both in childhood had dogs named Toy. During their school years, the brothers had a passion for mathematics and could not stand spelling, and when they grew up, they married ladies named Linda.

It turned out that even the sons of their adoptive parents were named the same - Larry, and both in childhood had dogs named Toy. During their school years, the brothers had a passion for mathematics and could not stand spelling, and when they grew up, they married ladies named Linda.

Jim Lewis (left), his adoptive mother Lucille and Jim Springer

Photo: AP

A few years later they divorced and married a second time. The new wives of Lewis and Springer were named Betty. By an unthinkable coincidence, women resembled each other not only in appearance, but also in character. In an interview, Springer remarked that they were easily mistaken for sisters. The twins soon had sons who were given names that differed by only one letter: James Alan and James Allan.

Both of them have a lot of common interests that are not so common. The twins loved carpentry and were engaged in drafting and lettering. At one time, both were deputies of the sheriff, Lewis also worked as a security guard at the smelter.

However, what united the brothers most of all was the feeling of inner emptiness. “It seemed to each of us that we were missing something important in our lives. This feeling disappeared only when we met, ”Springer explained.

Test subjects

The story of the twins spread all over the world and interested scientists. Psychologist Thomas Bouchard, Jr. of the University of Minnesota, decided that Lewis and Springer were ideally suited to study the influence of heredity on personality, interests, and intellectual development. Genes were opposed to the environment, which also affects a person.

“We are convinced that these identical twins, raised apart, will go down in history and become the object of scientific research. They will be written about in books,” Bouchard said before meeting with the brothers. Lewis and Springer visited him in Minneapolis on March 1979 years old.

Jim Lewis (left) and Jim Springer with psychologist Thomas Bouchard, Jr.

Photo: AP

“We stayed at the university for a week. And all this time passed the tests one by one. Among other things, scientists took blood tests from us, did x-rays, gave us personality tests. My brother and I hardly saw each other there. Unless they accidentally crossed paths in the corridor, ”Springer said in a television interview.

When the twins were asked to draw the first thing that came to their mind, they drew the same picture. “This experiment was recorded on video. We were told to draw something. Of course, we were apart,” Springer recalls. - Well, I drew a person, the outlines of the body. Just an image I made up. And, imagine, Jim drew the same thing! Just think, he could have depicted a house or, for example, a car. Yes, whatever. But we both drew the same thing."

Springer remembered another test they had to take at the university. The scientists showed each twin the same picture and asked them to make up a story. “They wanted us to write a story with a denouement and ending based on what they saw,” Springer said. “And again, we all matched. Although, you see, there were many options for the development of events. According to him, one might think that the same person was tested. “It’s all in my head,” he added.

“And again, we all matched. Although, you see, there were many options for the development of events. According to him, one might think that the same person was tested. “It’s all in my head,” he added.

“If I had not heard the story of the twins firsthand, I would hardly have believed it to be true,” said Bouchard. The test results amazed not only scientists, but also the world media. Many TV channels, magazines and newspapers tried to interview Lewis and Springer and find out the unique details of their lives. Through the publicity about the birth-separated Ohio twins, Bouchard met other twins who had grown apart. Later they also became the objects of his research.

Thomas Bouchard Jr. experimenting on the Jim twins

Photo: Thomas S. England / East News

Eight years later, Lewis and Springer returned to Minneapolis for a new study. This time, the scientists were interested in how the twins changed as they aged, and whether these changes occurred in the same way for each.