Born with hip dysplasia

Hip Dysplasia | Boston Children's Hospital

What is hip dysplasia?

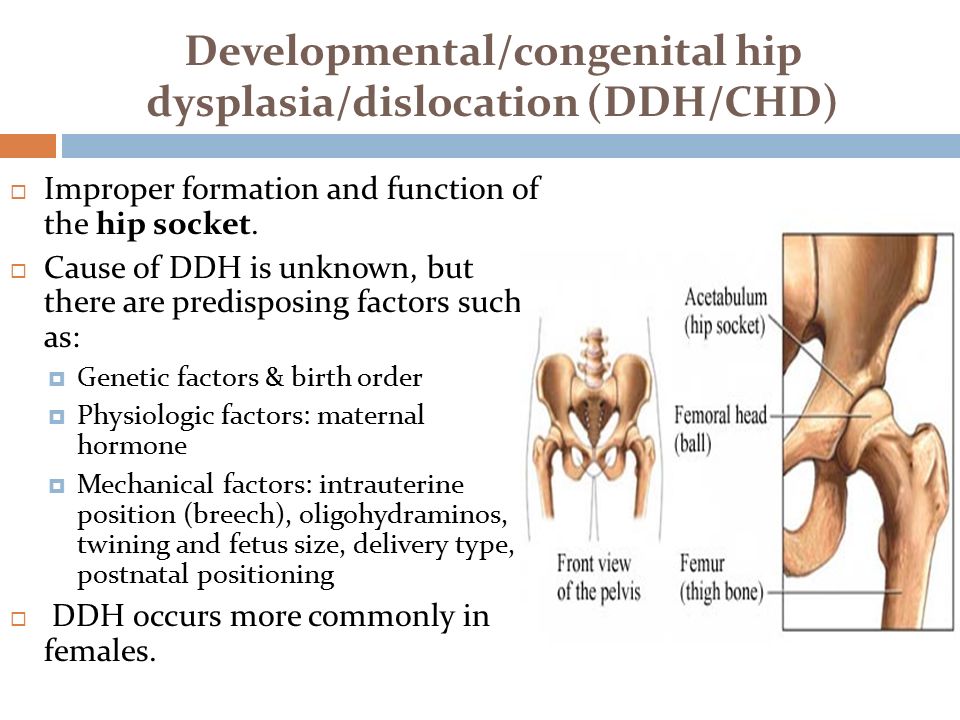

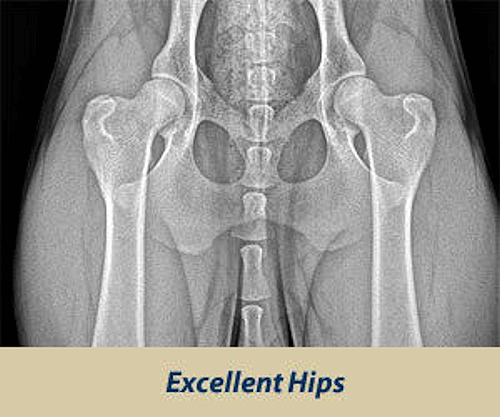

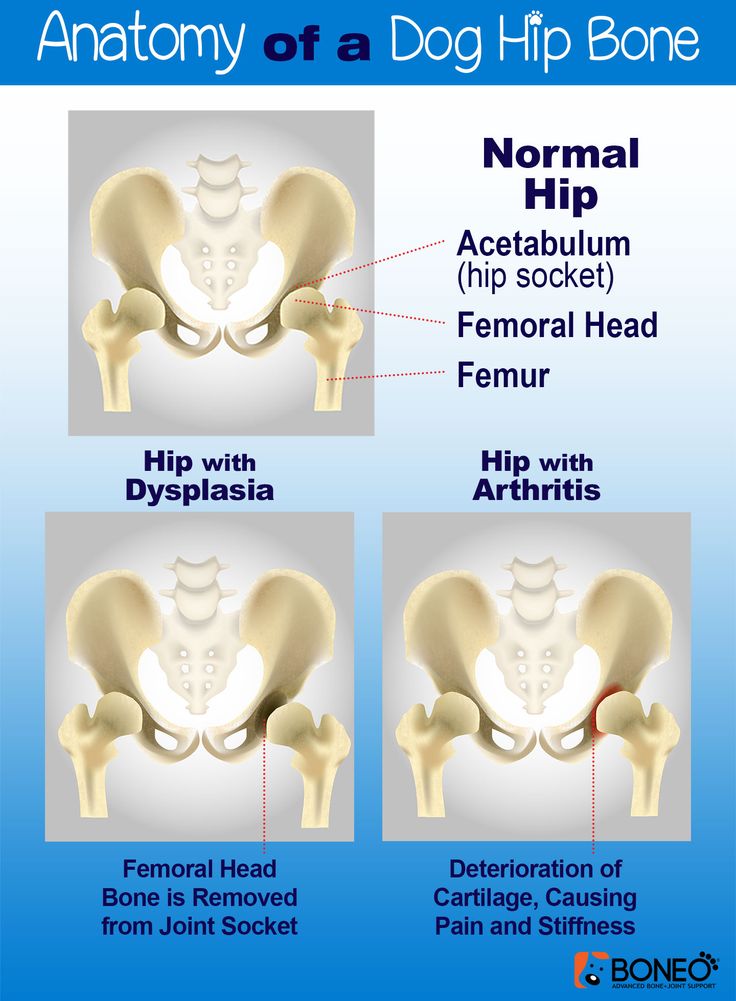

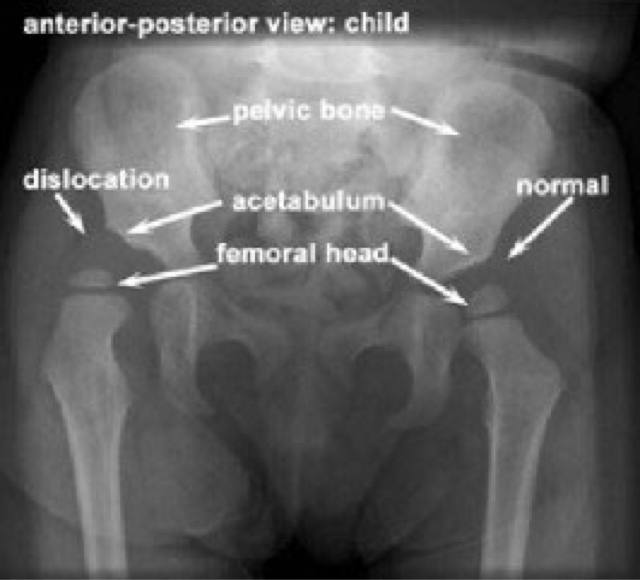

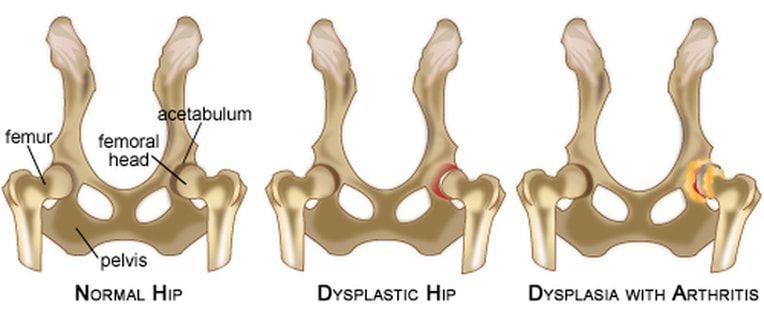

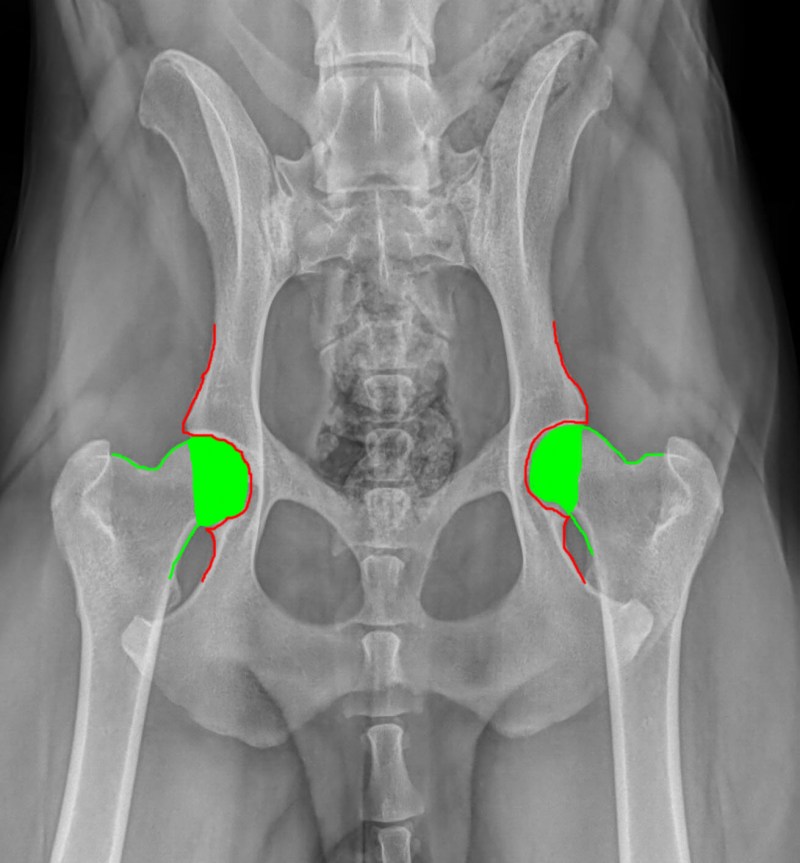

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint. Normally, the ball at the top of the thigh bone fits into the hip socket. Hip dysplasia occurs when the hip joint has not developed properly and the socket (acetabulum) is too shallow. This allows the ball (femoral head) to slip partially or completely out of the joint. Hip dysplasia ranges from a mild abnormality to a complete dislocation of the hip.

Severe cases of hip dysplasia are usually diagnosed during a routine screening within the first few months of a baby’s life. Other times, the problem may only become noticeable as a child grows and becomes more active.

Hip dysplasia is a treatable condition. However, if left untreated, it can cause irreversible damage that will cause pain and loss of function later in life. It is the leading cause of early arthritis of the hip before the age of 60. The severity of the condition and catching it late increase the risk of arthritis. Therefore, monitoring and early intervention are both important to reduce a child’s risk of pain and disability in adulthood.

Who is affected?

Hip dysplasia can affect anyone at any age. Although it is believed to develop around birth, a child with mild dysplasia may not have symptoms for years, or even decades.

- Hip dysplasia in babies is known as infant developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH).

- When diagnosed in adolescents and young adults, it is sometimes called acetabular dysplasia.

The age at which older kids and young adults with hip dysplasia begin to notice symptoms depend on the severity of the condition and their activity level. Athletes who place a lot of load on their hips by participating in dance, hockey, football, soccer, or track and field may experience symptoms sooner.

Meet Louise

Undiagnosed hip dysplasia caused such severe knee pain, this former track star sometimes had trouble walking after competitions. With surgery behind her, and a degree in medicine in the works, she has returned to the sport she loves.

With surgery behind her, and a degree in medicine in the works, she has returned to the sport she loves.

Read her story

Girls and women are two to four times more likely than boys to have hip dysplasia. It also tends to affect first-born children and those who have a close family member with hip problems. Some people with hip dysplasia are affected in only one hip while others have it in both hips.

In boys, the condition tends to be accompanied by other hip problems. These include acetabular retroversion (when the hip socket grows too far over the head of the femur) or CAM lesions (extra bone growth on the surface of the bone that causes extra friction and joint damage).

Hip dysplasia is sometimes confused with hip impingement, which occurs when extra bone grow on the acetabulum or femoral head. The irregular shape creates friction within the joint and wears down cartilage. Some patients have both conditions, both of which cause hip pain and are easy to confuse. However, they are different issues that require different treatments.

However, they are different issues that require different treatments.

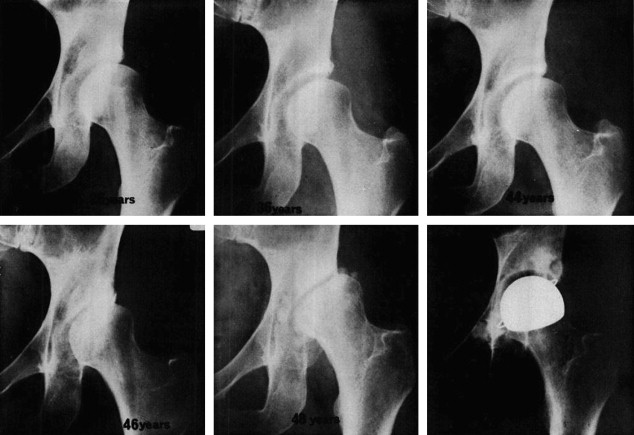

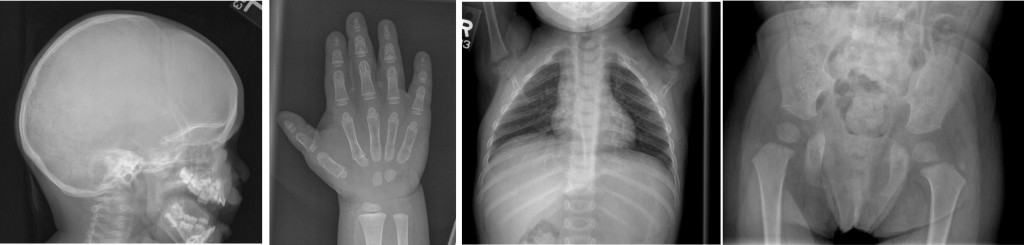

Image

Image

Generally speaking, treating hip dysplasia as early as possible can minimize joint damage and reduce the chance of early onset arthritis.

How we care for hip dysplasia

The Child and Young Adult Hip Preservation Program at Boston Children’s Hospital is at the forefront of research and innovation. We combine specialized expertise in non-surgical and surgical treatments with structured physical therapy to help children, adolescents, and young adults live healthy, active lives.

Our team has treated thousands of children with every level of complexity and severity of hip deformity. Our hip specialists have pioneered minimally invasive procedures as well as open surgical techniques to help treat patients of all ages. We perform more periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) procedures every year than any other hospital in the country and have helped hundreds of athletes return to the activities they love.

We have the experience to treat you or your child. Our goal is the same as yours: to help you get better so you can return to being healthy and pain-free.

Patient resources

Download these fact sheets to learn more about hip dysplasia and treatment options.

- fact sheet: developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH)

- fact sheet: Pavlik harness

- fact sheet: hip dysplasia in adolescents and young adults

Hip Dysplasia | Hip Dysplasia in Adolescents

What is hip dysplasia in adolescents?

Hip dysplasia occurs when the hip socket (acetabulum) doesn't develop properly and is too shallow to cover the head of the thigh bone (femoral head) completely. Many adolescents and young adults with the condition were born with developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH). In others, previously healthy hips did not develop properly as their bones and bodies grew.

Meet Alana and Nicole

A year and a half after hip surgery, Nicole still questioned her physical capabilities. That changed when she met Alana, another dancer who’d had the same surgery. This chance meeting became a turning point in both dancers' healing.

That changed when she met Alana, another dancer who’d had the same surgery. This chance meeting became a turning point in both dancers' healing.

Read their story

The condition ranges from a mild abnormality of the hip socket to a complete dislocation of the hip. As children become more active and demand more of their legs, the ill-fitting hip joint becomes unstable. The instability damages cartilage inside the joint that becomes increasingly painful over time.

It is important not to ignore hip pain. Hip dysplasia is a treatable condition but early diagnosis and treatment are critical to preventing irreversible damage.

What are the symptoms of hip dysplasia in adolescents and young adults?

Teens or young adults may develop a limp or have hip pain in the front of the hip or groin. For others, the first sign is knee pain. You might hear a clicking sound in your hip. As the damage progresses, you may find it more and more painful to participate in sports and other activities. Without treatment, the pain will continue to become worse.

Without treatment, the pain will continue to become worse.

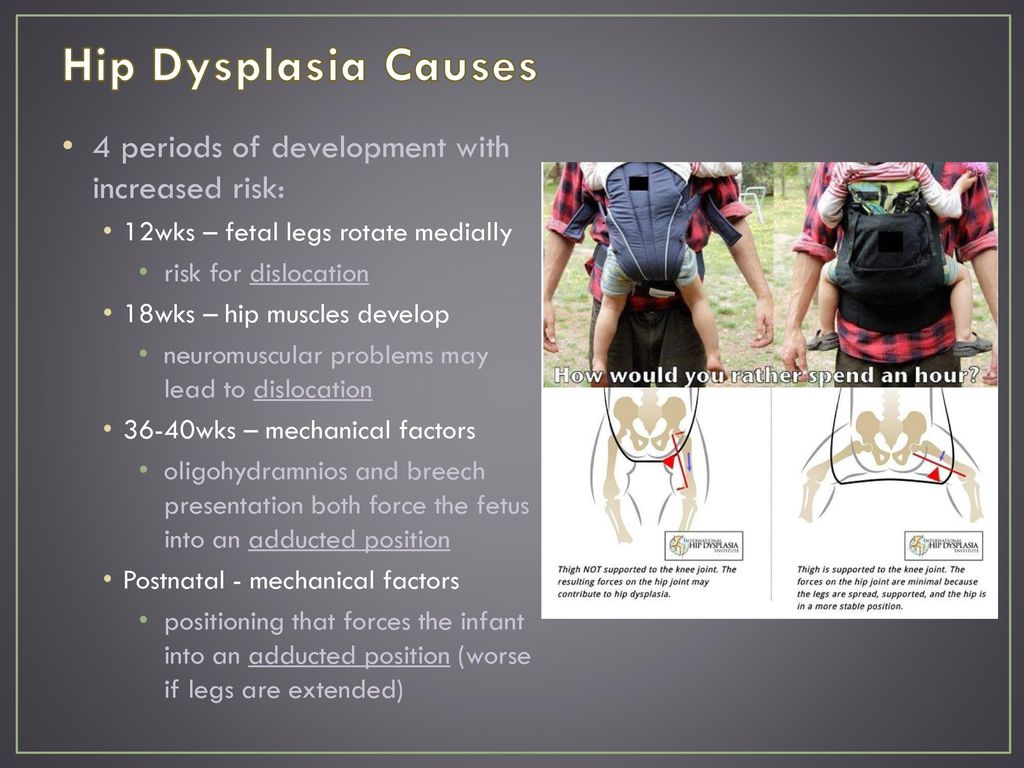

What causes hip dysplasia in adolescents and young adults?

Some teens and young adults are born with mild DDH that becomes symptomatic as they grow. However, the hip joint continues to develop throughout the teen years and sometimes does not develop properly, even if you were not born with DDH. Doctors are not sure why this happens but they do know that the condition affects girls two to four times as often as boys. People with a close relative with hip problems are also at higher risk.

Image

Image

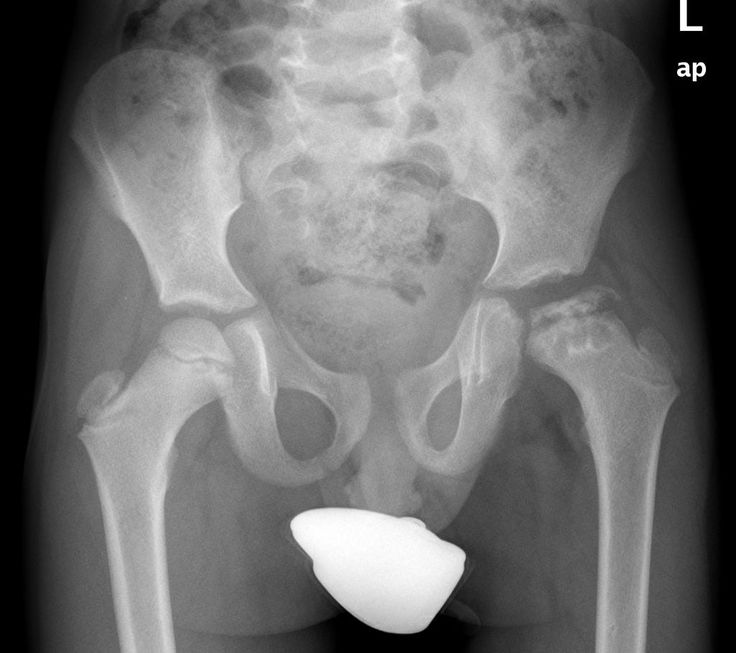

How is hip dysplasia diagnosed in adolescents and young adults?

Doctors typically use variety of tests to determine if dysplasia is the source of hip pain in adolescents and young adults.

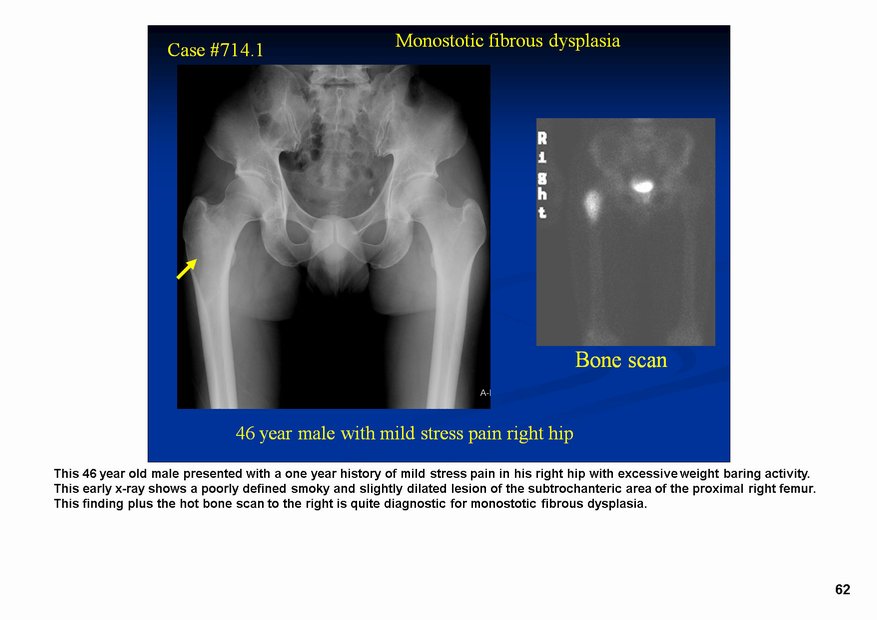

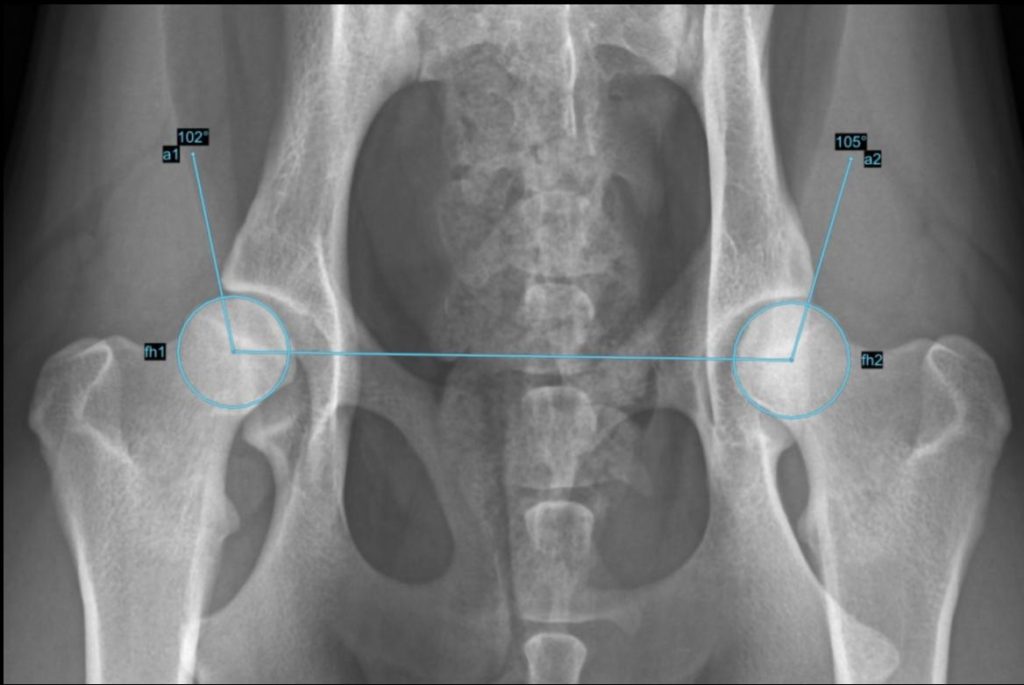

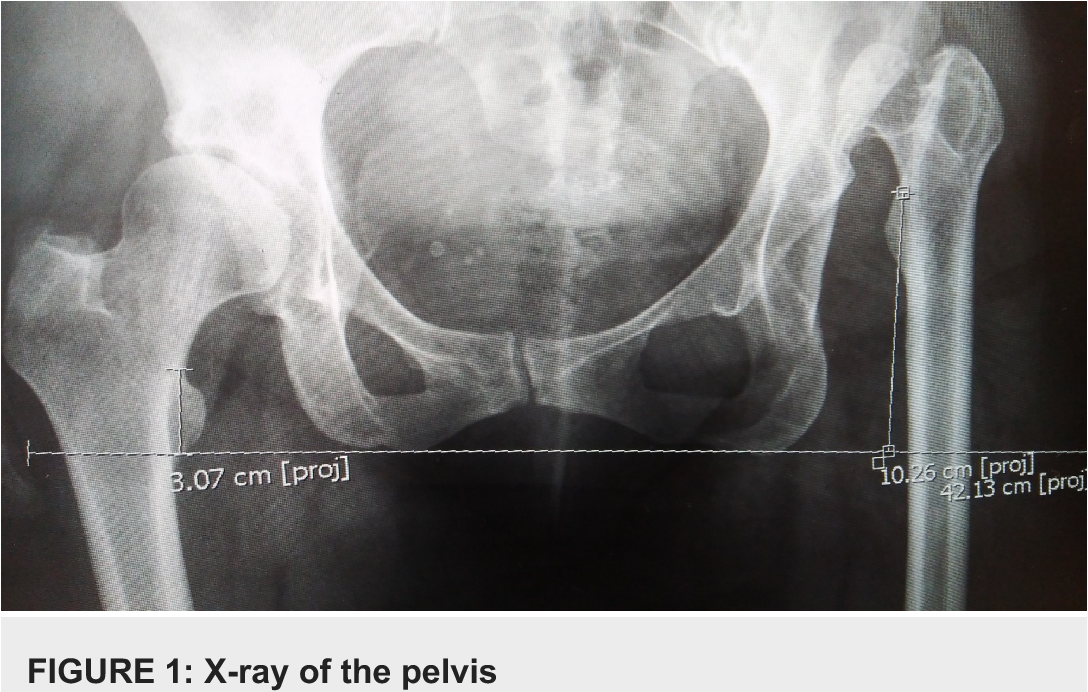

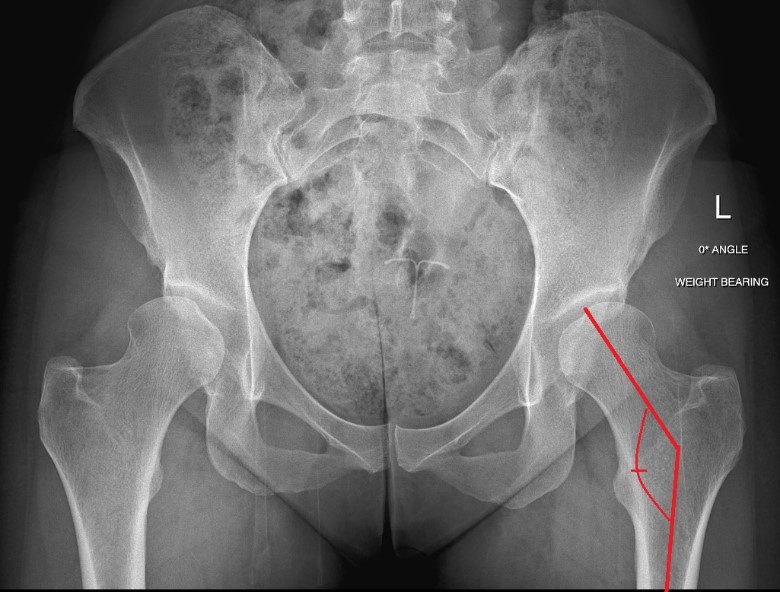

The first step is a thorough patient history and physical exam. The doctor will check your hip for range of motion. They may order imaging studies such as an x-ray, MRI, or CT scan to confirm the diagnosis. Ultrasound-guided diagnostic injection can help your doctor determine the location of your hip pain with greater precision.

Ultrasound-guided diagnostic injection can help your doctor determine the location of your hip pain with greater precision.

How is hip dysplasia treated in adolescents and young adults?

The goal of treatment is to restore normal hip function and eliminate pain. Your treatment will depend on the severity of your condition.

Non-surgical treatment options for adolescents and young adults

Mild to moderate cases of hip dysplasia are often treated with physical therapy and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). If you continue to be in pain after these treatments, your physician may suggest surgery.

Surgical options for adolescents and young adults

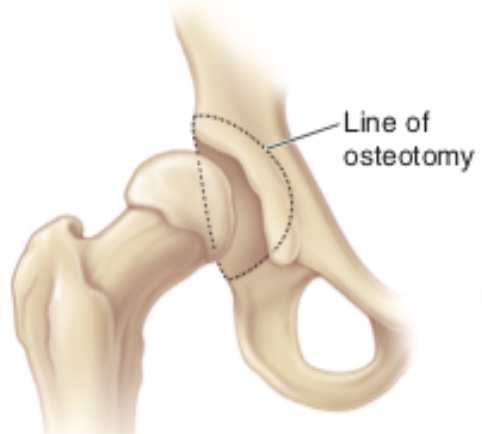

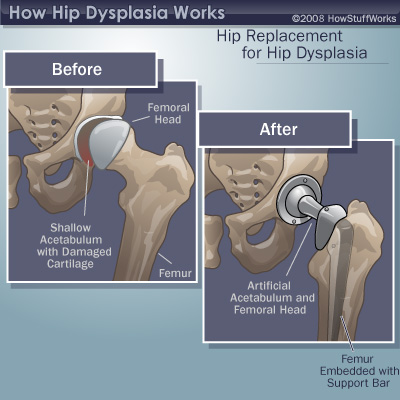

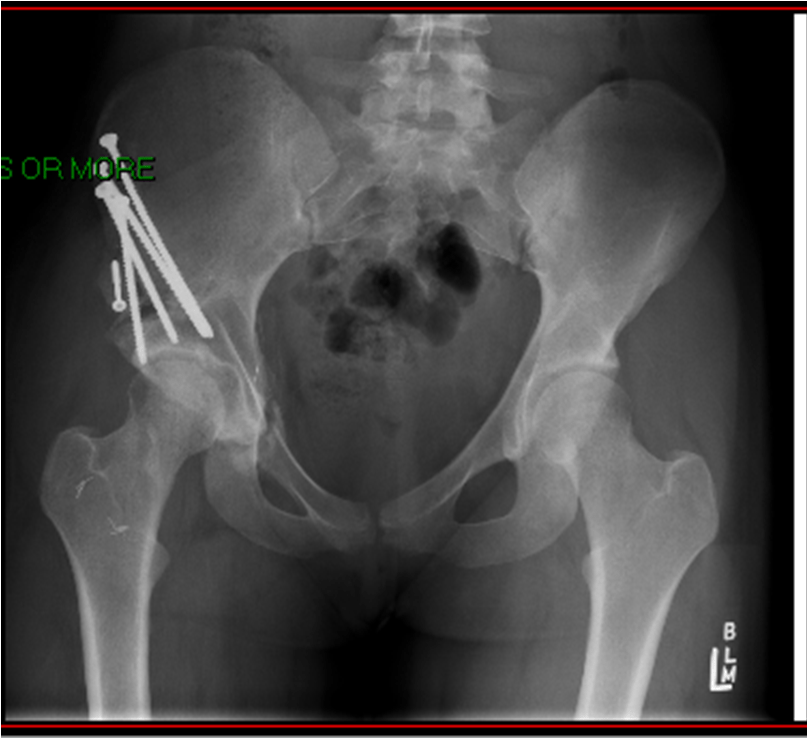

Periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) is the main surgical treatment for adolescents and young adults with hip dysplasia. PAO may serve as a lifelong treatment if performed before serious damage occurs within the joint.

The goals of PAO are to:

- reduce or eliminate pain

- maximize the function of your hip

- enable you to return to sport or other activity

Hip Dysplasia | Hip Dysplasia in Babies

What is hip dysplasia in babies?

Hip dysplasia in babies, also known as developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), occurs when a baby’s hip socket (acetabulum) is too shallow to cover the head of the thighbone (femoral head) to fit properly. DDH ranges in severity. Some babies have a minor looseness in one or both of their hip joints. For other babies, the ball easily comes completely out of the socket.

DDH ranges in severity. Some babies have a minor looseness in one or both of their hip joints. For other babies, the ball easily comes completely out of the socket.

Image

What are the symptoms of hip dysplasia in babies?

Many babies with DDH are diagnosed during their first few months of life.

Common symptoms of DDH in infants may include:

- The leg on the side of the affected hip may appear shorter.

- The folds in the skin of the thigh or buttocks may appear uneven.

- There may be a popping sensation with movement of the hip.

What causes hip dysplasia in babies?

The exact cause is unknown, but doctors believe several factors increase a child’s risk of hip dysplasia:

- a family history of DDH in a parent or other close relative

- gender — girls are two to four times more likely to have the condition

- first-born babies, whose fit in the uterus is tighter than in later babies

- breech position during pregnancy

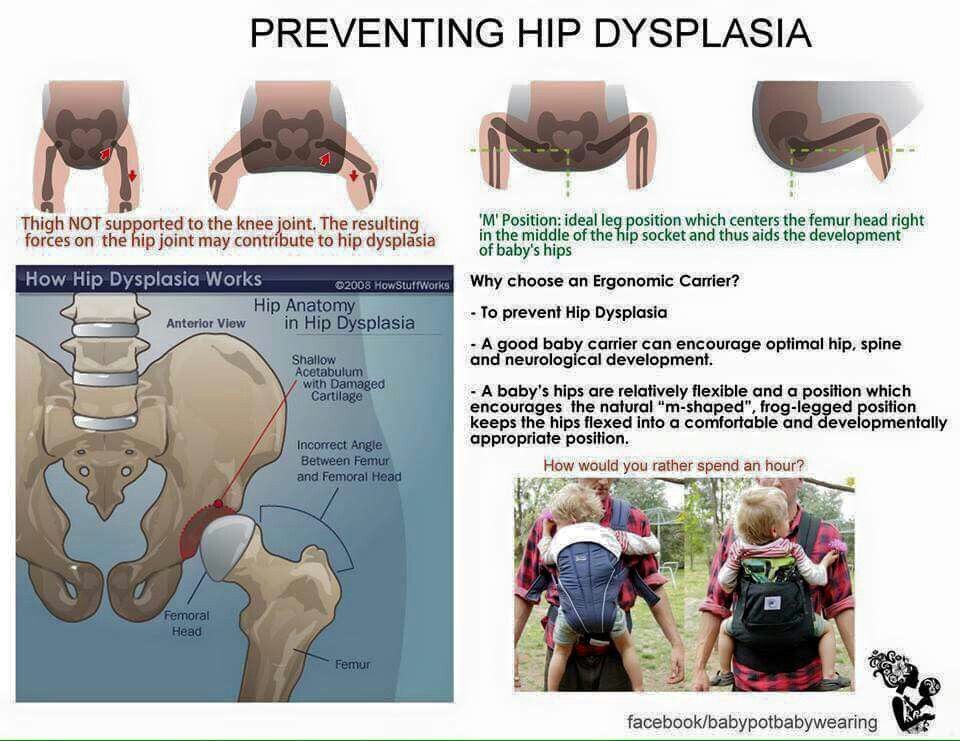

- tight swaddling with legs extended

Breech position: Babies whose bottoms are below their heads while their mother is pregnant with them often end up with one or both legs extended in a partially straight position rather than folded in a fetal position. Unfortunately, this position can prevent a developing baby’s hip socket from developing properly.

Unfortunately, this position can prevent a developing baby’s hip socket from developing properly.

Tight swaddling: Wrapping a baby’s legs in a straight position may interfere with healthy development of the joint. If you swaddle your baby, you can wrap their arms and torso snugly, but be sure to leave room for their legs to bend and move.

Angela's story

Angela was 5 when her parents brought her to Boston Children’s Hospital, where she was diagnosed with hip dysplasia in both hips.

How is hip dysplasia diagnosed?

Infants in the U.S. are routinely screened for hip dysplasia. During the exam, the doctor will ask about your child’s history, including their position during pregnancy. They’ll also ask if there is any history of hip problems on either parent’s side.

The doctor will do a physical exam and order diagnostic tests to get detailed images of your child’s hip. Typical tests can include:

- Ultrasound (sonogram): Ultrasound uses high-frequency sound waves to create pictures of the femoral head (ball) and the acetabulum (socket).

It is the preferred way to diagnose hip dysplasia in babies up to 6 months of age.

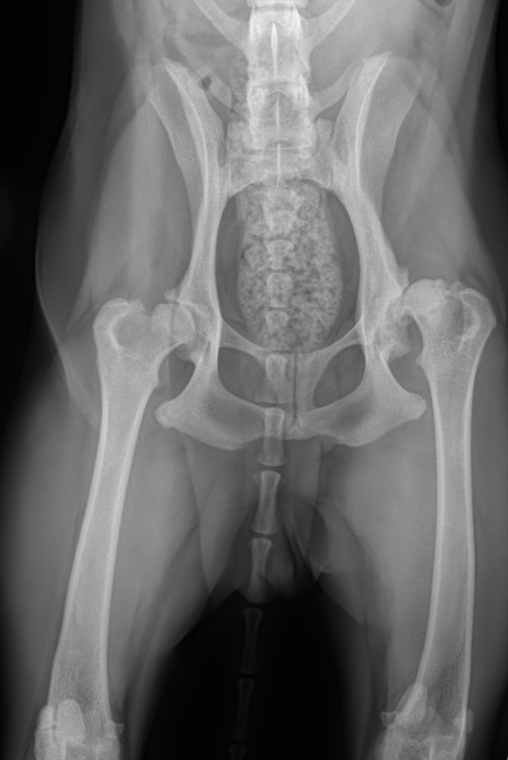

It is the preferred way to diagnose hip dysplasia in babies up to 6 months of age. - X-ray: After a child is 6 months old and bone starts to form on the head of the femur, x-rays are more reliable than ultrasounds.

How is hip dysplasia treated?

Your child’s treatment will depend on the severity of their condition. The goal of treatment is to restore normal hip function by correcting the position or structure of the joint.

Non-surgical treatment options

Observation

If your child is 3 months or younger and their hip is reasonably stable, their doctor may observe the acetabulum and femoral head as they develop. There’s a good possibility the joint will form normally on its own as your child grows.

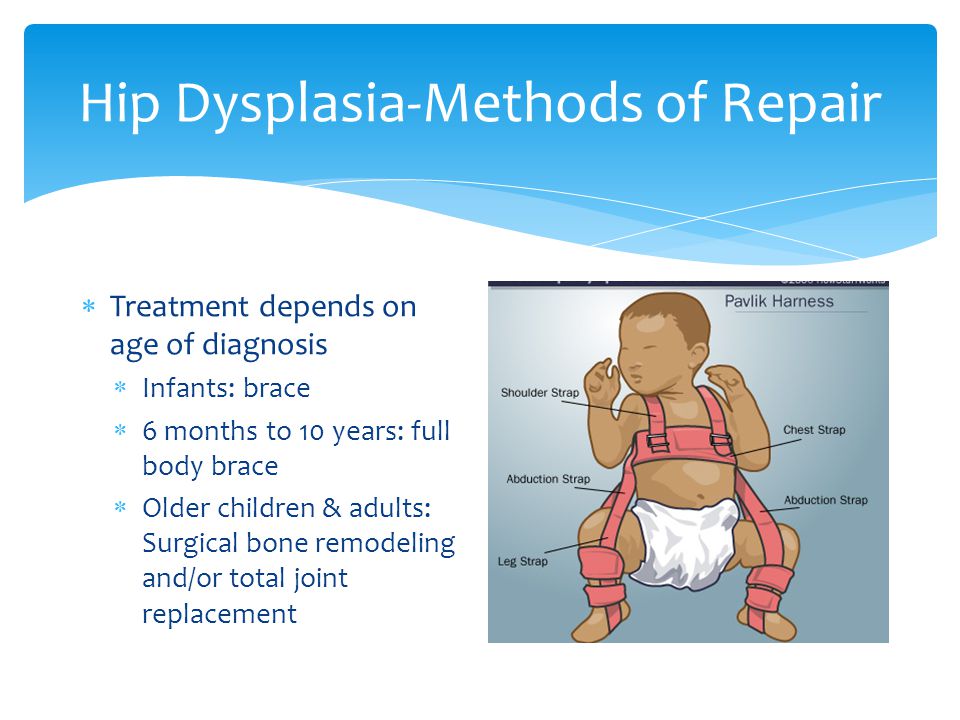

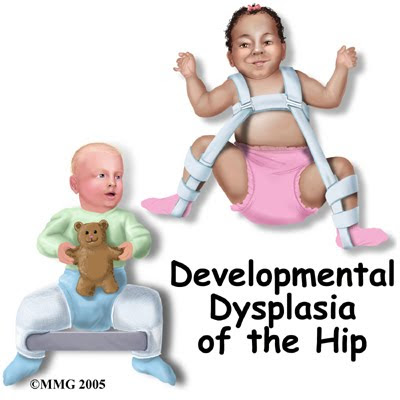

Pavlik harness

If your child’s hip is unstable or sufficiently shallow, their doctor may recommend a Pavlik harness. The Pavlik harness is used on babies up to four months old to hold their hip in place while allowing their legs some movement. The baby usually wears the harness all day and night until their hip is stable and an ultrasound shows their hip is developing normally. Typically, this takes about eight to 12 weeks. Your child’s doctor will tell you how many hours a day your child should wear the harness. Typically, children wear the harness 24 hours a day.

The baby usually wears the harness all day and night until their hip is stable and an ultrasound shows their hip is developing normally. Typically, this takes about eight to 12 weeks. Your child’s doctor will tell you how many hours a day your child should wear the harness. Typically, children wear the harness 24 hours a day.

Image

While your child is wearing the harness, their doctor will frequently examine the hip and use imaging tests to monitor its development. After successful treatment, your child will need to continue to see the doctor regularly for the next few years to monitor the development and growth of their hip joint.

Typically, infants’ hips are successfully treated with the Pavlik harness. But some babies’ hips continue to be partially or completely dislocated. If this is the case, your child’s doctor may recommend another type of brace called an abduction brace. The abduction brace is made of lightweight material that supports your child’s hips and pelvis. If your child’s hip becomes stable with an abduction brace, they will wear the brace for about eight to 12 weeks. If the abduction brace does not stabilize the hip, your child may need surgery.

If your child’s hip becomes stable with an abduction brace, they will wear the brace for about eight to 12 weeks. If the abduction brace does not stabilize the hip, your child may need surgery.

Image

Surgical treatment options for babies

Closed reduction

If your child’s hip continues to be partially or completely dislocated despite the use of the Pavlik harness and bracing, they may need surgery. Under anesthesia, the doctor will insert a very fine needle in the baby’s hip and inject contrast so they can clearly view the ball and the socket. This test is called an arthrogram.

The process of setting the ball back into the socket after the arthrogram is known as a closed reduction. Once the hip is set in place, technicians will put your child in a spica cast. This cast extends from slightly below the armpits to the legs and holds the hip in place. Different casts cover differing amounts of the child’s legs, based on the condition of their hips. Children typically wear a spica cast for three to six months. The cast will be changed from time to time as your baby grows.

Children typically wear a spica cast for three to six months. The cast will be changed from time to time as your baby grows.

Open reduction

If a closed reduction does not work, your child’s doctor may recommend open-reduction surgery. For this, the surgeon makes an incision and repositions the hip so it can grow and function normally. The specifics of the procedure depend on your child’s condition but it may include reshaping the hip socket, redirecting the femoral head, or repairing a dislocation. After the surgery, your child will need to wear a spica cast while they heal.

Follow-up care

Any infant treated surgically for hip dysplasia must be followed periodically by an orthopedist until they have reached physical maturity. At regular visits, their orthopedic doctor will monitor their hip to ensure it develops normally as they grow. Diagnosing and treating any new abnormality early will increase the chance your child will grow up to be active free from hip pain throughout their childhood, the teen years, and adulthood.

Will treatment affect my child’s ability to walk?

Depending on their age during treatment, your child may start walking later than other kids. However, after successful treatment, children typically start walking as well as other kids. By contrast, children with untreated hip dysplasia often start walking later, and many walk with a limp.

Hip Dysplasia | Programs & Services

Departments

Centers

Programs

Hip Dysplasia | Contact Us

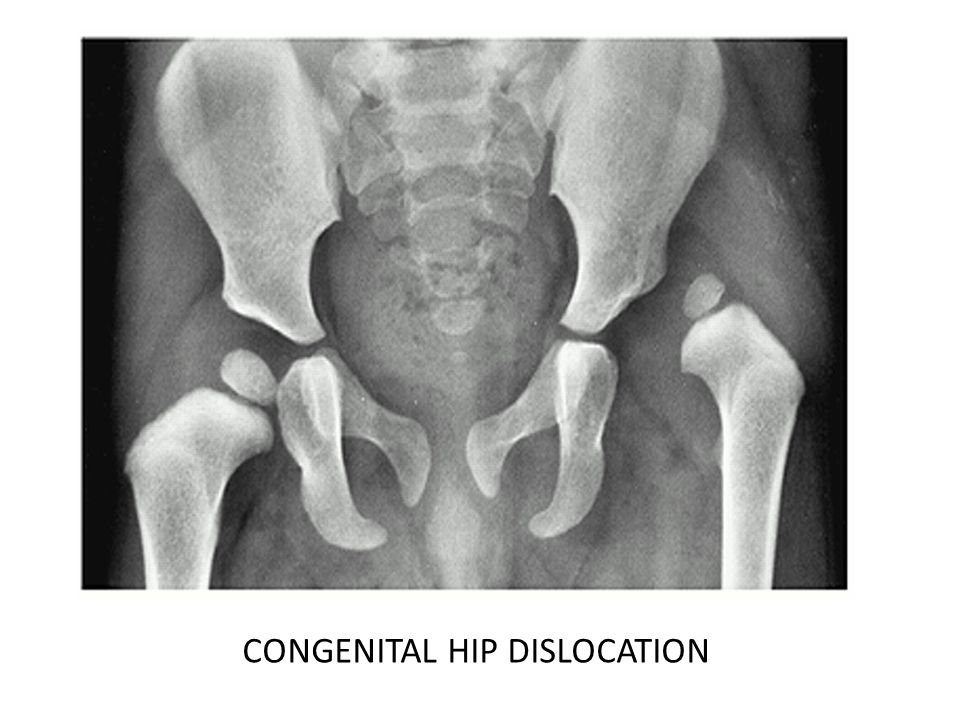

Developmental dysplasia of the hip

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is a condition where the "ball and socket" joint of the hip does not properly form in babies and young children.

It's sometimes called congenital dislocation of the hip, or hip dysplasia.

The hip joint attaches the thigh bone (femur) to the pelvis. The top of the femur (femoral head) is rounded, like a ball, and sits inside the cup-shaped hip socket.

The top of the femur (femoral head) is rounded, like a ball, and sits inside the cup-shaped hip socket.

In DDH, the socket of the hip is too shallow and the femoral head is not held tightly in place, so the hip joint is loose. In severe cases, the femur can come out of the socket (dislocate).

DDH may affect 1 or both hips, but it's more common in the left hip. It's also more common in:

- girls

- firstborn children

- families where there have been childhood hip problems (parents, brothers or sisters)

- babies born in the breech position (feet or bottom downwards) after 28 weeks of pregnancy

Without early treatment, DDH may lead to:

- problems moving around, for example a limp

- pain

- osteoarthritis of the hip and back

With early diagnosis and treatment, children are less likely to need surgery, and more likely to develop normally.

Diagnosing DDH

Your baby's hips will be checked as part of the newborn physical screening examination within 72 hours of being born, and again at 6 to 8 weeks of age.

The examination involves gently moving your baby's hip joints to check if there are any problems. It should not cause them any discomfort.

If a doctor, midwife or nurse thinks your baby's hip feels unstable, they should have an ultrasound scan of their hip between 4 and 6 weeks old.

Babies should also have an ultrasound scan of their hip between 4 and 6 weeks old if:

- there have been childhood hip problems in your family

- your baby was born in the breech position (feet or bottom downwards) after 28 weeks of pregnancy

If you have had twins or multiples and 1 of the babies was in the breech position, each baby should have an ultrasound scan of their hips by the time they're 4 to 6 weeks old.

Sometimes a baby's hip stabilises on its own before the scan is due, but they should still be checked to make sure.

Get help and support from the charity Steps if your baby's been diagnosed with DDH

Treating DDH

Pavlik harness

Babies diagnosed with DDH early in life are usually treated with a fabric splint called a Pavlik harness.

This secures both of your baby's hips in a stable position and allows them to develop normally.

Credit:

DR P. MARAZZI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY https://www.sciencephoto.com/media/729142/view

The harness needs to be worn constantly for 6 to 12 weeks and should not be removed by anyone except a health professional.

The harness may be adjusted during follow-up appointments. Your clinician will discuss your baby's progress with you.

Your clinician will discuss your baby's progress with you.

Your hospital will provide detailed instructions on how to look after your baby while they're wearing a Pavlik harness.

This will include information on:

- how to change your baby's clothes without removing the harness – nappies can be worn normally

- cleaning the harness if it's soiled – it still should not be removed, but can be cleaned with detergent and an old toothbrush or nail brush

- positioning your baby while they sleep – they should be placed on their back and not on their side

- how to avoid skin irritation around the straps of the harness – you may be advised to wrap some soft, hygienic material around the bands

Eventually, you may be given advice on removing and replacing the harness for short periods of time until it can be permanently removed.

You'll be encouraged to allow your baby to move freely when the harness is off. Swimming is often recommended.

Surgery

Surgery may be needed if your baby is diagnosed with DDH after they're 6 months old, or if the Pavlik harness has not helped.

The most common surgery is called reduction. This involves placing the femoral head back into the hip socket.

Reduction surgery is done under general anaesthetic and may be done as either:

- closed reduction – the femoral head is placed in the hip socket without making any large cuts

- open reduction – a cut is made in the groin to allow the surgeon to place the femoral head into the hip socket

Your child may need to wear a cast for at least 12 weeks after the operation.

Their hip will be checked under general anaesthetic again after 6 weeks, to make sure it's stable and healing well.

After this investigation, your child will probably wear a cast for at least another 6 weeks to allow their hip to fully stabilise.

Some children may also require bone surgery (osteotomy) during an open reduction, or at a later date, to correct any bone deformities.

Late-stage signs of DDH

The newborn physical screening examination, and the infant screening examination at 6 to 8 weeks, aim to diagnose DDH early.

But sometimes hip problems can develop or show up after these checks.

It's important to contact a GP as soon as possible if you notice your child has developed any of the following symptoms:

- 1 leg cannot be moved out sideways as far as the other when you change their nappy

- 1 leg seems to be longer than the other

- 1 leg drags when they crawl

- a limp or "waddling" walk

Your child will be referred to an orthopaedic specialist in hospital for an ultrasound scan if your doctor thinks there's a problem with their hip.

Hip-healthy swaddling

A baby's hips are naturally more flexible for a short period after birth. But if your baby spends a lot of time tightly wrapped (swaddled) with their legs straight and pressed together, there's a risk this may affect their hip development.

Using hip-healthy swaddling techniques can reduce this risk. Make sure your baby is able to move their hips and knees freely to kick.

Find out more about hip-healthy swaddling on the International Hip Dysplasia Institute website

Page last reviewed: 08 August 2022

Next review due: 08 August 2025

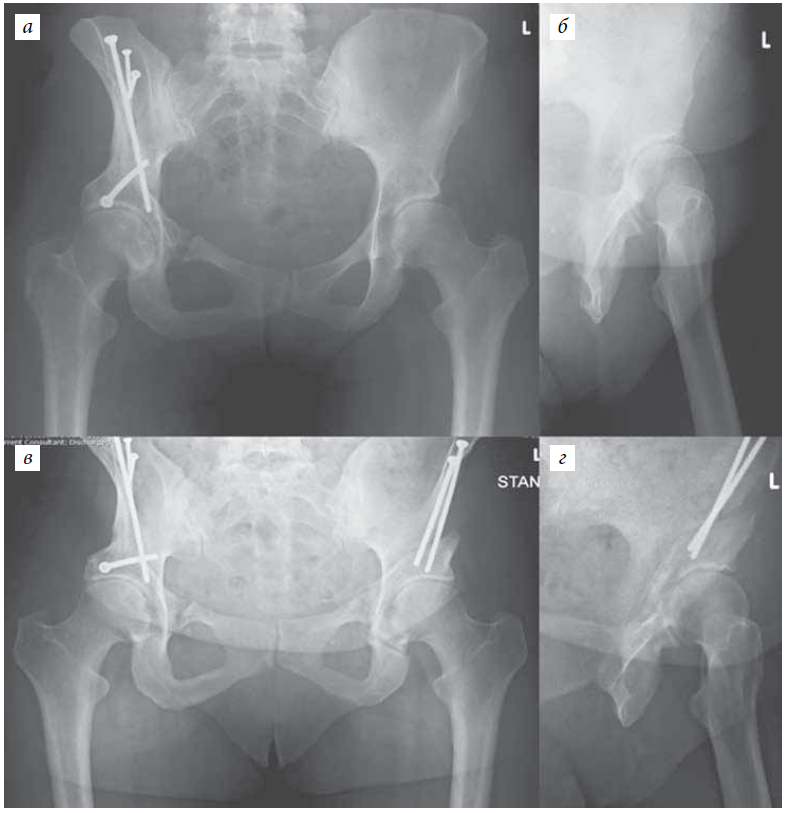

Dysplasia in a child: the main thing is to start treatment on time

Young parents often meet with such a diagnosis in a baby as hip dysplasia. This is a congenital inferiority of the joint, which is due to its underdevelopment and can lead to subluxation or dislocation of the hip.

Traumatologist-orthopedist of the first qualification category of the Chelyabinsk Regional Children's Clinical Hospital Alexander Semenov tells about the signs of dysplasia, methods of treatment and the main mistakes of parents.

- Alexander Vladimirovich, why does dysplasia occur?

- One of the reasons leading to disruption of the normal development of the joint is its abnormal development already in utero. The disease begins to develop at 5-6 weeks of gestation.

Genetic and hormonal factors influence. Hip dysplasia is 10 times more common in children whose parents had signs of congenital hip dislocation. It is worth noting that in girls, hip dysplasia occurs twice as often and is especially difficult.

- Can a woman learn about the disease during pregnancy through ultrasound and avoid its development?

- During ultrasound, as a rule, this diagnosis is not revealed. In this case, nothing depends on the woman. Here the main thing is timely diagnosis in a child and proper treatment.

Here the main thing is timely diagnosis in a child and proper treatment.

- What should parents pay attention to first of all?

- For the asymmetry of the folds on the legs and buttocks, during gymnastics - restriction of movement in the joint. Parents often complain that one leg is shorter than the other in a child, but most often this symptom is misinterpreted. Factors such as breech presentation of the fetus, large fetus, pregnancy toxemia should alert a pregnant woman in terms of possible congenital joint pathology in a child. The risk in these cases increases tenfold.

- Is there an asymptomatic course of dysplasia?

- It happens. Sometimes parents cannot suspect dysplasia on their own when there is no restriction of movement in the hip joint. In this case, only a doctor detects the disease. Therefore, in one month, the child must be examined by an orthopedist.

- But orthopedists are not available in all areas of the Chelyabinsk region. What about families from the outback?

What about families from the outback?

- Currently, about 18 orthopedists are being treated in the Chelyabinsk region, two of them are in the regional hospital, three in the region - in Kopeysk, Miass and Zlatoust, about 13 - in the city of Chelyabinsk. The orthopedist must necessarily examine the child within the decreed terms (1 month, 6 months, 12 months), so if there is no doctor in the area, you need to take a referral to our children's regional clinic. We are ready to accept all children from the Chelyabinsk region.

In addition, in some maternity hospitals in the region, a screening ultrasound of the hip joints is performed on the 5-7th day of the newborn to exclude dysplasia. If the disease is detected, then the baby is discharged already with recommendations and a referral to an orthopedist.

- What are the treatments for dysplasia?

- The main principles of treatment are early onset, the use of orthopedic devices for long-term retention of the legs in the position of abduction and flexion, active movements in the hip joint.

The main thing in treatment is gymnastics, which parents should perform with their children. The task of exercise therapy is to strengthen the muscles of the hip joint and organize the child's motor activity, sufficient for full physical development. It usually includes five types of exercises. In addition, complex treatment should include massage and physiotherapy. In more severe cases (severe dysplasia, subluxation, dislocation of the hip), we use various orthopedic aids - Pavlik's stirrups at an earlier age, spacer splints for older children.

- Where is the child being treated?

- We send patients for treatment at their place of residence. The main responsibility in this case lies with the parents, they must perform a set of exercises daily. And massage and physiotherapy can be obtained in polyclinics at the place of residence.

- Who can massage a child?

- Massage can only be done by a specially trained massage therapist, certified and preferably specialized in baby massage.

- How does swaddling a baby affect treatment?

- Previously, tight swaddling was used, now it has already been abandoned, because in this case the joint is in a non-physiological position. Now experts recommend either wide swaddling or a free position for the legs.

- If a child is prescribed orthopedic products, then his movements are limited for a long time. How will this affect his future development?

- Nothing. The fact is that there is no particular restriction on movement. If parents follow the orthopedic regimen, then in 80% of cases we cancel Pavlikama's stirrups after 3 months. Even if a child wears a spacer splint for six months, this only has a positive effect on the formation of his joints. In the future, this will not affect the overall development of the child.

- Is it possible to completely get rid of dysplasia?

- The leading role is played by early recognition of this defect and timely treatment. With timely treatment and compliance with the orthopedic regimen by parents, about 70% of children recover completely, but 30% develop gait disturbance at an older age.

With timely treatment and compliance with the orthopedic regimen by parents, about 70% of children recover completely, but 30% develop gait disturbance at an older age.

If we talk about congenital dislocation of the hip, then there is a high probability of developing arthrosis of the hip joint in a few years. But still, in most children, the disease goes away without a trace if it is detected in time and treated.

- How many children in the Chelyabinsk region suffer from dysplasia?

- Every day 4-5 people from all over the region come to our regional polyclinic with this diagnosis. Congenital dislocation occurs once or twice a month. Luckily, there are not so many cases. Basically, this happens in remote areas of the Chelyabinsk region, where it is not possible to show the child to an orthopedist in a timely manner.

Childhood hip dysplasia

Contents

Introduction

- Definition

- Epidemiology

- Etiology and pathogenesis

- Risk factors

- Clinical stages

- ICD-10 classification

- Diagnostics

- Treatment

- Forecast

- Output

“Your child was born with hip dysplasia” - this news in the maternity hospital can shock unprepared parents, because a lot of questions immediately arise: “Why does our child have?”, “And this is now forever?”, “What should we do now ? etc. The first thing to do is stop panicking. Hip dysplasia has always existed, in the medical literature it was first described by Hippocrates in the 300s BC. In most cases, the situation is resolved on its own, in others, this will only require the use of special fixing splints, and only a small number of children may require more serious intervention - plastering or surgical treatment.

The first thing to do is stop panicking. Hip dysplasia has always existed, in the medical literature it was first described by Hippocrates in the 300s BC. In most cases, the situation is resolved on its own, in others, this will only require the use of special fixing splints, and only a small number of children may require more serious intervention - plastering or surgical treatment.

Hip dysplasia describes a spectrum of different pathologies in newborns and young children. This includes abnormal development of the acetabulum and proximal femur, as well as mechanical instability of the hip joint. As information accumulated, the terminology changed. Initially, they often talked about congenital dislocation of the hip, but the pathology is not always identified at birth, developing in early childhood, so the definition of "congenital" was abandoned. Further, it turned out that not only dislocation, but also a number of other conditions can be a manifestation of pathology, so that the modern term “hip (or hip) joint dysplasia” was formed as a result.

Estimates of the incidence of hip dysplasia are quite variable and depend on the means of detection, the age of the child, and diagnostic criteria. It is estimated that dislocation of the hip or hips with severe or persistent dysplasia occurs in 3 to 5 children per 1000. Historically, the incidence of hip dysplasia with dislocation has been 1 to 2 per 1000 children. Mild hip instability is more common in neonates, with a reported incidence of up to 40%. However, mild instability and/or mild dysplasia in the neonatal period often resolves on its own without intervention from specialists. Infants with mild instability and/or mild dysplasia during the neonatal period, according to modern concepts, should not be included in the assessment of general morbidity, otherwise there is a distortion that significantly overstates the overall assessment of the prevalence of pathology.

In a prospective study published in the journal Pediatrics, 9,030 infants (18,060 hips) were routinely screened for hip dysplasia by physical examination and ultrasound during the first to third days of life. Ultrasound anomalies were found in 995 joints, the incidence was 5.5%. However, when re-examined at 2 to 6 weeks of age without prior treatment, residual anomalies were found in only 90 hip joints, which ultimately corresponds to the true incidence of dysplasia of 0.5%. It was these children who needed further treatment. In other words, 90% of newborns with clinical or ultrasound evidence of hip dysplasia improved spontaneously between two and six weeks of age to the point where they did not require medical intervention.

Ultrasound anomalies were found in 995 joints, the incidence was 5.5%. However, when re-examined at 2 to 6 weeks of age without prior treatment, residual anomalies were found in only 90 hip joints, which ultimately corresponds to the true incidence of dysplasia of 0.5%. It was these children who needed further treatment. In other words, 90% of newborns with clinical or ultrasound evidence of hip dysplasia improved spontaneously between two and six weeks of age to the point where they did not require medical intervention.

The incidence of hip dysplasia depends to some extent on ethnic factors. It is maximum among the Saami and American Indians (from 25 to 50 cases per 1000 births), minimum - in populations of African and Asian origin.

Both joints are affected in 37% of patients. Among unilateral cases, the left hip is more commonly affected than the right. The predominance of left-sided cases may be due to the typical location of the fetus in the uterus, in which the left thigh is pressed against the mother's sacrum.

Development of the hip joint depends on normal contact between the acetabulum and the femoral head to promote mutual induction. Abnormal development can result from disruption of this contact as a result of a variety of genetic and environmental factors, both prenatal and postnatal.

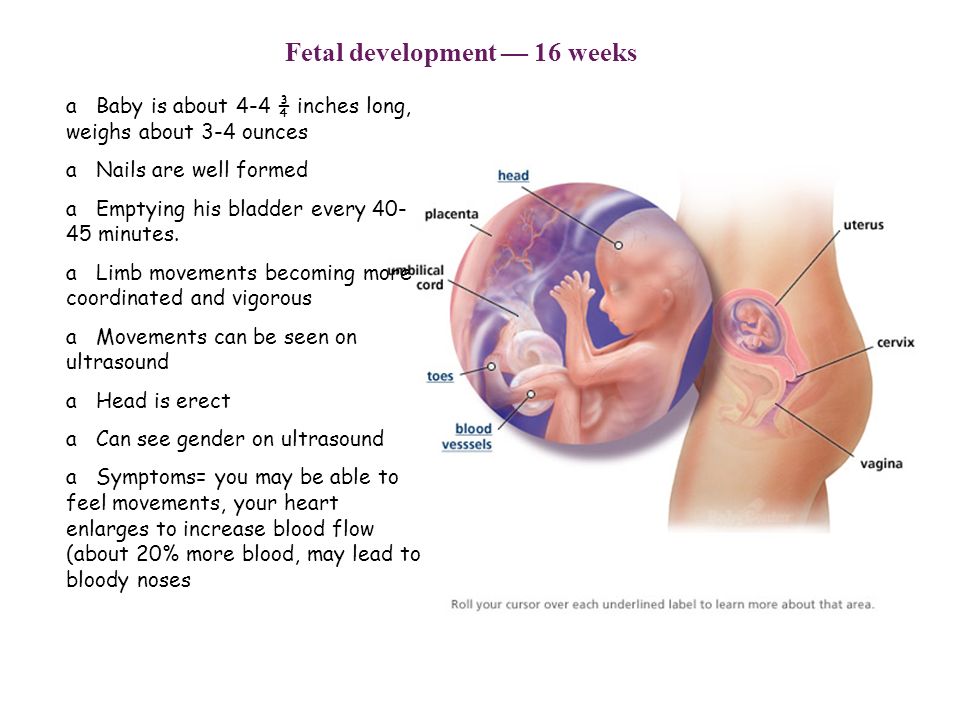

By the 11th week of pregnancy, the hip joint is usually fully formed. The head of the femur is spherical and is set deep in the acetabulum. However, it grows faster than the socket, so that by the end of pregnancy, the head of the femur is covered by the roof of the acetabulum by less than 50%. During the last four weeks of pregnancy, the femur is vulnerable to mechanical influences, such as adduction, which guide the femoral head away from the central part of the acetabulum. Conditions that limit fetal mobility, including breech presentation, exacerbate these mechanical factors. All this leads to eccentric contact between the femoral head and the acetabulum.

During the neonatal period, ligament weakness makes the developing hip susceptible to other external mechanical influences. A fixed position with extended hips, such as tight swaddling, can result in eccentric hip contact as the femoral head slides in or out of the acetabulum. If these factors persist, abnormal contact of the hip joint leads to structural anatomical changes. If the head of the femur has not entered deep into the acetabulum, the upper lip may turn out and flatten, and the round ligament may elongate. Abnormal ossification of the acetabulum occurs and a shallow variant develops.

Over time, hypertrophy of intra-articular structures occurs, including the upper lip with a thickened ridge (neolimbus), round ligament and fibro-adipose tissue (pulvinar). Contractures develop in the iliopsoas and hip adductors, and the inferior capsule retracts into the empty acetabulum, further reducing the likelihood of transition of the femoral head into the acetabulum. A false acetabulum can form where the head of the femur meets the lateral wall of the pelvis above the true acetabulum. Lack of contact between the femoral head and the acetabulum inhibits further normal development of the hip joint.

Lack of contact between the femoral head and the acetabulum inhibits further normal development of the hip joint.

With or without complete hip dislocation, dysplastic changes may develop. The most common result is a shallow acetabulum with reduced anterior and lateral coverage of the femoral head. There may also be asphericity of the femoral head, valgus angle of the neck and shaft, and persistence of excessive anteversion of the femur.

Dysplasia is more common among infants with certain risk factors (eg, female sex, breech presentation in the third trimester, family history, tight lower extremity swaddling). However, with the exception of females, most infants with a confirmed diagnosis of hip dysplasia do not have any specific risk factors that could be realized.

Female. The risk of dysplasia in girls is estimated at 1.9%. Hip dysplasia occurs in them two to three times more often than in boys. In a 2011 meta-analysis published in the European Journal of Radiology, which evaluated 24 studies and more than 556,000 patients, the relative risk of dysplasia for girls was 2. 5 compared with boys.

5 compared with boys.

The increase in incidence in girls has been associated with a temporary increase in ligament laxity associated with increased susceptibility of female infants to the maternal hormone relaxin. However, some studies refute this hypothesis.

The increased incidence of dysplasia in girls is difficult to separate from the increased risk of this condition in breech presentation, which is also significantly more common in girls.

Presentation. Breech and breech presentation during the third trimester is the most significant single risk factor for hip dysplasia in children. The absolute risk of dysplasia is estimated at 12% in breech presentation girls and 2.6% in breech presentation boys. In the already mentioned meta-analysis of risk factors, 15 studies (more than 359300 patients) in presentation, and the relative risk of breech presentation was 3.8. It is not clear in the literature whether the amount of time spent in breech presentation, or the point on the pregnancy timeline at which the fetus was in breech presentation, affects the risk of dysplasia.

An increased risk of dysplasia is present regardless of mode of delivery. However, reducing the time spent in breech presentation by elective caesarean section may reduce the risk of clinically significant hip dysplasia. This was illustrated in a 2019 retrospective review.year, published in the journal Pediatrics & Child Health, which found a reduction in the incidence of dysplasia among children with breech presentation who were born by elective caesarean section (3.7% compared with 6.6% among children born by caesarean section during childbirth, and 8.1% among children born naturally).

Family history. Genetic factors appear to play a role in the development of hip dysplasia in children. The absolute risk in infants with a positive family history is approximately 1 to 4%. In the already mentioned 2011 meta-analysis in the European Journal of Radiology, the authors examined four studies (more than 14,000 patients) on the topic and determined that the relative risk of a positive family history was 1. 39. If one of the twins has dysplasia, the risk of a similar pathology in the other twin is higher if they are monozygotic than dizygotic (40% versus 3%).

39. If one of the twins has dysplasia, the risk of a similar pathology in the other twin is higher if they are monozygotic than dizygotic (40% versus 3%).

Family members of children with dysplasia are also at increased risk of occult acetabular dysplasia, which often develops before age 30.

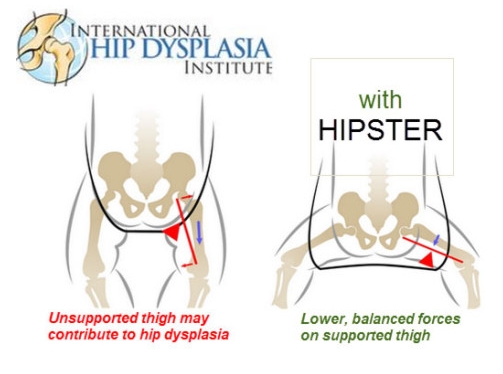

Swaddling. The incidence of hip dysplasia is increasing in populations that use diapers and lullaby boards. These practices limit the mobility of the hip joint and fix the hip in adduction and extension, which may play a role in the development of hip dysplasia. In an experimental study in rats, traditional swaddling during hip adduction and extension resulted in a higher incidence of dislocations and dysplasia than no swaddling.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the Pediatric Orthopedic Society of North America (POSNA), and the International Hip Dysplasia Institute (IHDI) recommend a “healthy hip swaddle,” also known as “loose swaddling,” that provides enough room for hip and knee flexion and free leg movement.

Other factors. Several other factors associated with decreased mobility or abnormal posture have been found to be associated with pediatric hip dysplasia, but no causal relationship has been proven. These include torticollis, plagiocephaly, adducted metatarsus, clubfoot, first birth, oligohydramnios, birth weight >4 kg, and multiple pregnancies.

Dysplasia in children, depending on the severity of the process, can be divided into the following stages:

Dysplasia. Violation of the shape of the hip joint, usually a shallow acetabulum, in which the upper and anterior edges are affected by the pathological process.

Reductive stage. The femur is dislocated at rest, but the femoral head can be placed into the acetabulum by manipulation, usually flexion and abduction.

Subluxation. The femoral head is in place at rest but may be partially dislocated or subluxated on examination. Joint with slight instability.

Joint with slight instability.

Sliding version. The head of the femur is within the cavity at rest, but easily goes beyond it not only during examination, but simply when changing position. Joint with instability.

Subluxation. The femoral head partially extends beyond the acetabulum and at rest, but always remains in contact with it.

Dislocation. Complete loss of contact between the femoral head and the acetabulum.

The ICD codes for hip dysplasia in children should be looked up in class Q65, congenital hip deformities. These include the following options:

Q65.0. Congenital hip dislocation unilateral

Q65.1. Congenital hip dislocation bilateral

Q65.2. Congenital dislocation of hip, unspecified

Q65.3. Congenital hip subluxation unilateral

Q65.4. Bilateral congenital subluxation of the hip

Q65.5. Congenital subluxation of hip, unspecified

Q65. 6. Unstable hip

6. Unstable hip

- Hip dislocation predisposition

- Hip subluxation predisposition

Q65.8. Other congenital deformities of the hip

- Anterior displacement of the femoral neck

- Congenital acetabular dysplasia

- Congenital:

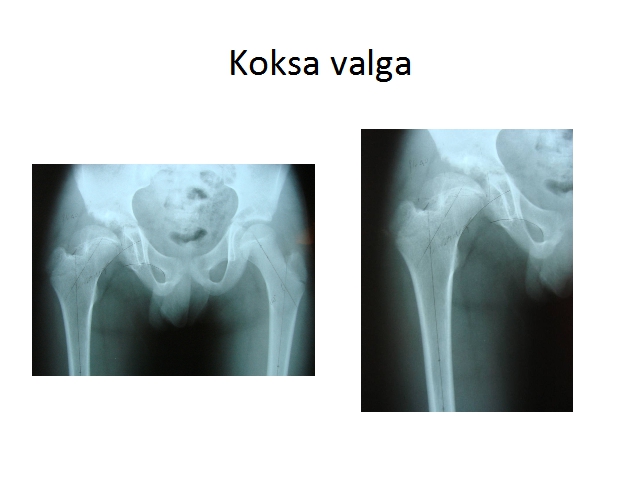

√ valgus position [coxa valga]

√ varus position [coxa vara]

Q65.9. Congenital deformity of the hip, unspecified

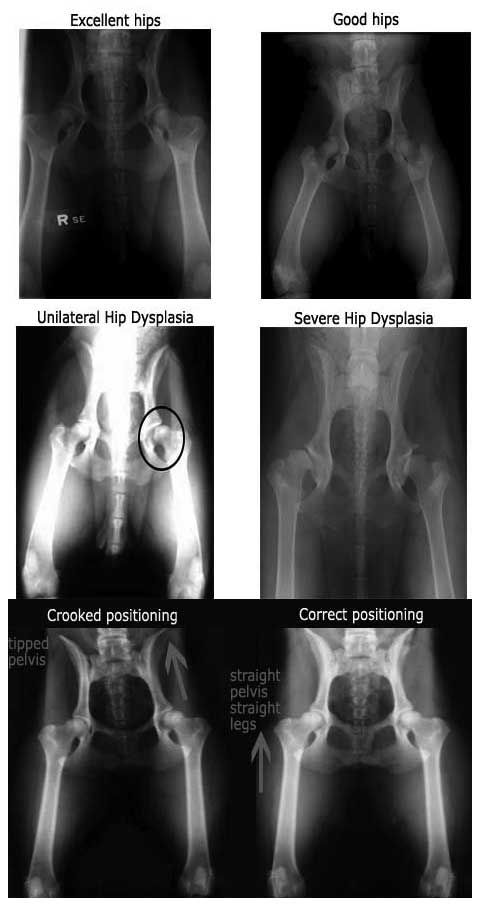

General inspection. Neurological examination and examination of the spine and lower legs is important for diagnosis, during which it is looked for associated with hip dysplasia and other causes of its instability.

- The neurologic examination should include assessment of spontaneous movements of all four limbs and assessment of spasticity.

- Examination of the spine should include range of motion (look for torticollis) and cutaneous manifestations of spinal dysraphism.

- Examination of the limbs should include examination of the foot for the presence of the metatarsal muscle.

Mobility assessment. Results vary by age:

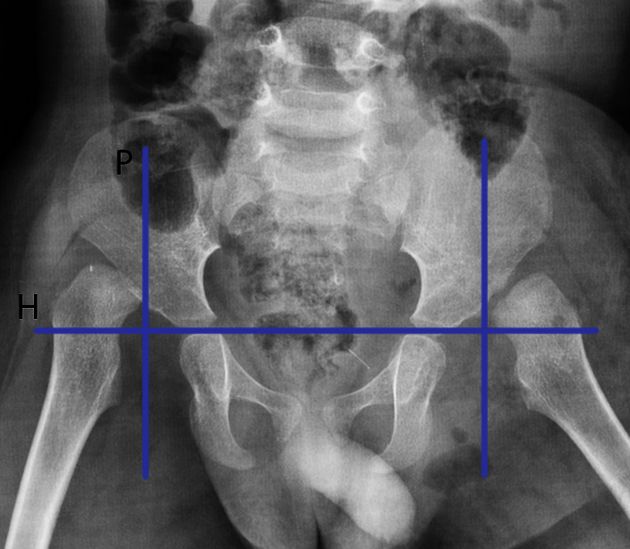

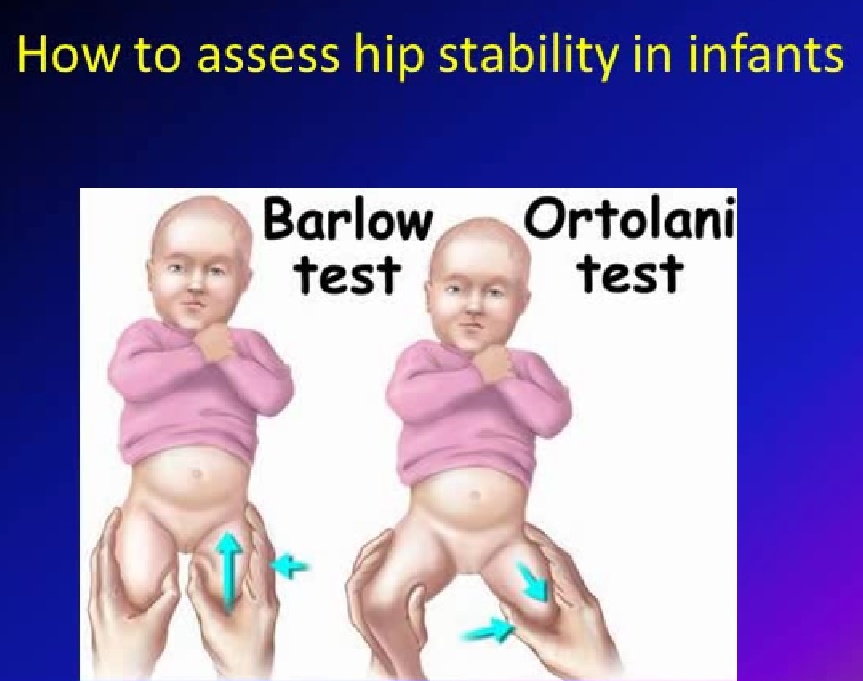

- In infants less than three months old, it is important to assess hip joint stability using the Ortolani maneuver. The Barlow maneuver, the Galeazzi test, and the Klisich test may also be helpful. There are usually no restrictions on joint abduction at this age

- In children older than three months, there may be an obvious discrepancy in the length of the legs (for unilateral cases). The Galeazzi tests for unilateral cases and the Klisich test may be considered better indicators of hip dysplasia than instability.

- In a walking child, weakness of the hip joints on the affected side can be recognized by a positive Tradelenburg test (inability to maintain the pelvis in a horizontal position while standing on the ipsilateral leg), as well as the presence of a Tradelenburg roll when walking.

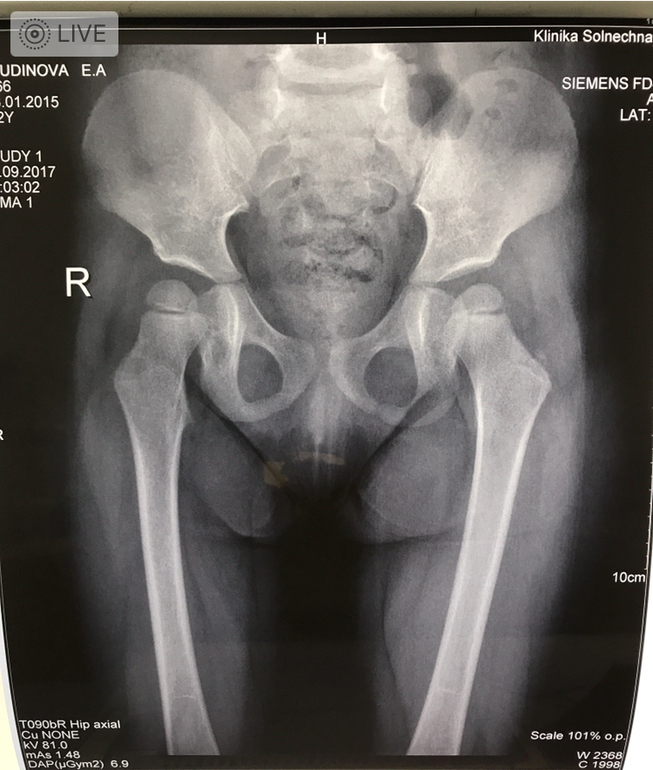

Ultrasound. Ultrasonography is the primary imaging modality for evaluating hip morphology and stability in suspected hip dysplasia. This is an important addition in the clinical evaluation of children under 4–6 months of age. The main drawback of the method is that an experienced and trained diagnostician is needed to accurately interpret the results. Ultrasound criteria for hip dysplasia have been established for both static and dynamic visualization of the flexed hip with and without the modified Barlow tension maneuver.

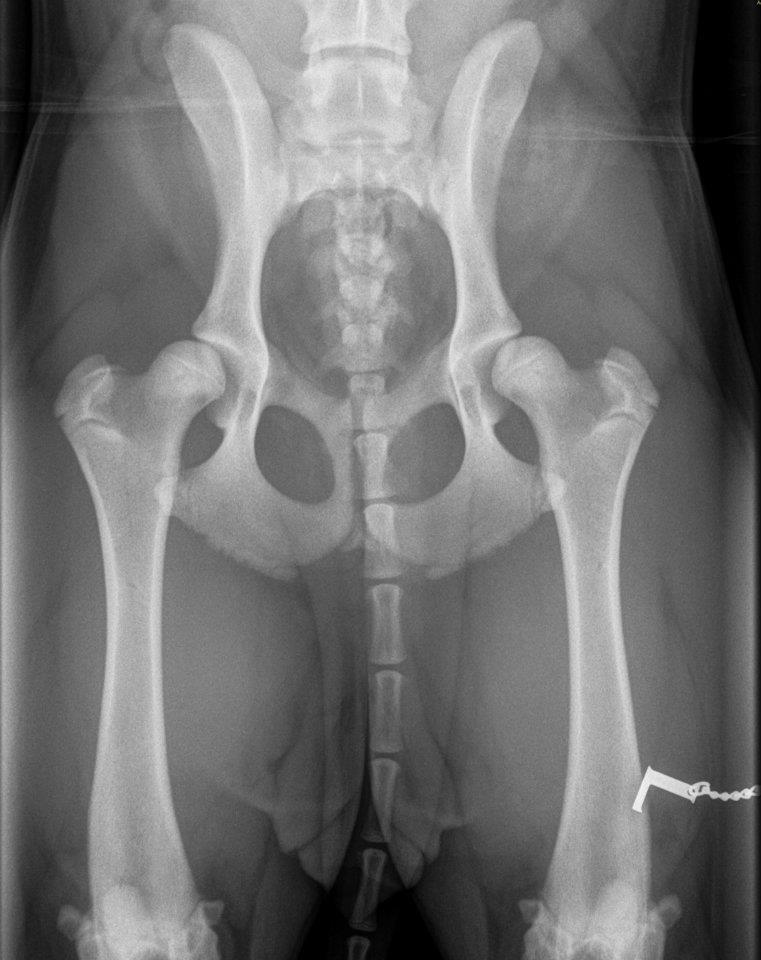

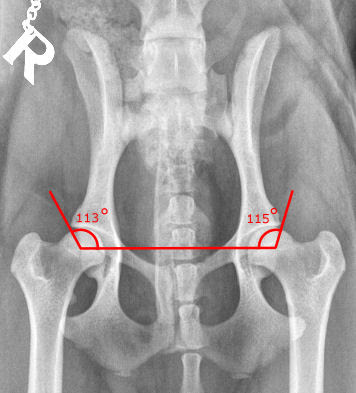

Radiography. May be useful in diagnosing hip dysplasia in children aged 4-6 months. In younger infants, it is not very informative, since the head of the femur and the acetabulum have not yet ossified and therefore do not contrast in the pictures.

Other imaging modalities. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are not suitable for diagnosing hip dysplasia in children, but can be used to assess the quality of reposition after surgery. At the same time, special pediatric protocols should be used for CT, providing for a reduction in radiation exposure during the study.

At the same time, special pediatric protocols should be used for CT, providing for a reduction in radiation exposure during the study.

Differential diagnosis. The main pathology from which hip dysplasia in children should be distinguished is also accompanied by limb shortening:

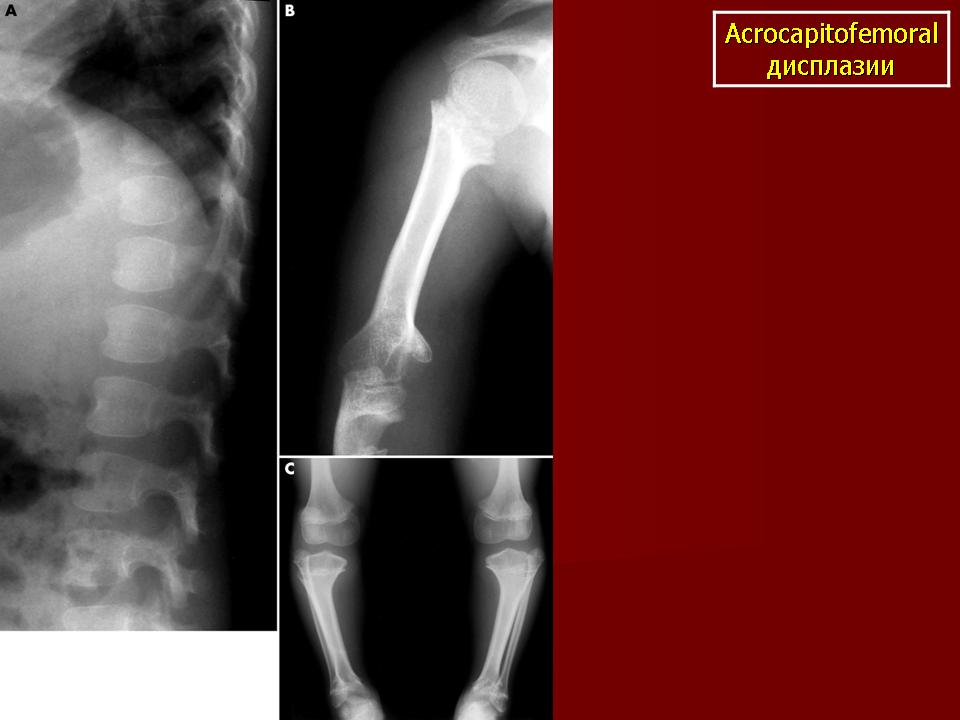

- Proximal focal femoral deficiency, a rare congenital disease, the spectrum of which varies from hypoplasia of the femoral head to the absence of everything except the distal epiphysis of the femur .

- Coxa vara defined by an angle of less than 120° between the femoral neck and the diaphysis, resulting in an elevation of the greater trochanter.

- Hemihypertrophy or hemihyperplasia (eg, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome).

- Agenesia of the sacrum with limb deformity.

In the vast majority of cases, hip dysplasia in children stabilizes on its own shortly after birth and does not require any special and separate interventions. In rare cases, with age, there may be a gradual progression of the disease, the appearance of chronic pain and accelerated development of osteoarthritis. The risk of such complications has not been determined, but it may be associated with the formation of a false acetabulum.

In rare cases, with age, there may be a gradual progression of the disease, the appearance of chronic pain and accelerated development of osteoarthritis. The risk of such complications has not been determined, but it may be associated with the formation of a false acetabulum.

The aim of the treatment of hip dysplasia in children is to obtain and maintain concentric contraction of the joint, that is, the alignment of the geometric centers of the femoral head and acetabulum. In young children, concentric reduction provides an optimal environment for the development of the components of the joint, in older children it helps to prevent or delay the development of osteoarthritis of the femoral joint.

The optimal environment for the development of the femoral head and acetabulum is one in which the cartilaginous surface of the femoral head is in contact with the cartilaginous floor of the acetabulum. Both the femoral head and the acetabulum have the ability to grow and reshape, which can lead to gradual resolution of the dysplasia over time (months to years) if concentric contraction is maintained. The upper age limit for acetabular remodeling has been estimated to be 18 months to 11 years, with maximum acetabular remodeling 4–6 years after hip dislocation reposition.

The upper age limit for acetabular remodeling has been estimated to be 18 months to 11 years, with maximum acetabular remodeling 4–6 years after hip dislocation reposition.

0-4 weeks. Dislocation of the hip is rare in children less than four weeks old, but joint laxity (mild instability) and/or a shallow acetabulum (dysplasia) is common. The management of infants less than four weeks of age depends on clinical findings and risk factors. At the same time, retrospective studies have not shown the advantage of starting the use of fixation devices as early as possible, therefore, these children are managed observationally, if necessary, performing follow-up ultrasounds.

4 weeks - 6 months. A variety of restraint devices are recommended: Pavlik stirrup, Aberdeen splint, Von Rosen splint for infants less than six months of age with hip dislocation or permanently dislocated or subluxated joints. In this case, it is better to give preference to Pavlik's stirrups, which are essentially a dynamic splint that prevents hip extension and limits adduction, which can lead to dislocation, but allows flexion and abduction. This position contributes to the normal development of the dysplastic joint, stabilization of its subluxation, and usually leads to a gradual reduction in the degree of dislocation, even if the joint does not return to normal on physical examination. It is not recommended to wear double or triple diapers on a child, although this approach was previously practiced. It has proven to be not only ineffective, but also potentially harmful, as it can promote hip extension, which is unfavorable for the normal development of the joint.

This position contributes to the normal development of the dysplastic joint, stabilization of its subluxation, and usually leads to a gradual reduction in the degree of dislocation, even if the joint does not return to normal on physical examination. It is not recommended to wear double or triple diapers on a child, although this approach was previously practiced. It has proven to be not only ineffective, but also potentially harmful, as it can promote hip extension, which is unfavorable for the normal development of the joint.

6-18 months. If the use of fixation devices is unsuccessful, surgery may be attempted, such as open or closed reduction under anesthesia. Children over six months of age have a less than 50% chance of successful recovery with Pavlik stirrups, and there is a higher risk of osteonecrosis (avascular necrosis) of the femoral head.

Orthopedists at most centers recommend treatment for a dislocated hip soon after diagnosis. The result is influenced by the age of the child and the development of the hip joint at the time of treatment. In observational studies, the earlier an intervention is undertaken, the higher the chance of success for a closed reduction; the older the patient, the greater the likelihood of needing open reduction and possible osteotomy of the femur and pelvis.

In observational studies, the earlier an intervention is undertaken, the higher the chance of success for a closed reduction; the older the patient, the greater the likelihood of needing open reduction and possible osteotomy of the femur and pelvis.

The long-term outcome of treatment depends on the severity of dysplasia, the age of diagnosis and treatment, and the presence of a concentrically reduced hip joint. It is generally accepted that the sooner a patient is treated, the higher the likelihood of a good outcome, which emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis. Approximately 90% of neonatal hips with instability or mild dysplasia resolve spontaneously with normal functional and radiographic findings.

If hip dysplasia is diagnosed before the age of six months, Pavlik stirrup treatment achieves and maintains hip contraction in approximately 95% of patients. Long-term follow-up is important to monitor residual dysplasia, which may occur in up to 20% of patients after successful treatment. Once the hip has stabilized and the patient has recovered from any surgical procedures, annual or biennial follow-up is recommended until skeletal maturity is reached.

Once the hip has stabilized and the patient has recovered from any surgical procedures, annual or biennial follow-up is recommended until skeletal maturity is reached.

Residual dysplasia after treatment or undiagnosed dysplasia may progress to osteoarthritis. Most young people who have undergone hip replacement due to dysplasia have not had

Hip dysplasia in children is a common pathology, but in the vast majority it resolves on its own and does not require special medical intervention. In more complex cases, for several weeks - before the completion of normal formation of the joint - it may be necessary to wear various fixation devices, while neither a cast nor "strict" swaddling is required. In isolated cases, surgery may be required, and the sooner it is performed, the higher the chances of success.

References

- Wedge JH, Wasylenko MJ. The natural history of congenital dislocation of the hip: a critical review // Clin Orthop Relat Res 1978; :154.

- Wedge JH, Wasylenko MJ. The natural history of congenital disease of the hip // J Bone Joint Surg Br 1979; 61-B:334.

- Crawford AH, Mehlman CT, Slovek RW. The fate of untreated developmental dislocation of the hip: long-term follow-up of eleven patients // J Pediatr Orthop 1999; 19:641.

- Bialik V, Bialik GM, Blazer S, et al. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: a new approach to incidence // Pediatrics 1999; 103:93.

- Castelein RM, Sauter AJ. Ultrasound screening for congenital dysplasia of the hip in newborns: its value // J Pediatr Orthop 1988; 8:666.

- Terjesen T, Holen KJ, Tegnander A. Hip abnormalities detected by ultrasound in clinically normal newborn infants // J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996; 78:636.

- Marks DS, Clegg J, al-Chalabi AN. Routine ultrasound screening for neonatal hip instability. Can it abolish late-presenting congenital dislocation of the hip? // J Bone Joint Surg Br 1994; 76:534.

- Dezateux C, Rosendahl K.

Developmental dysplasia of the hip // Lancet 2007; 369:1541.

Developmental dysplasia of the hip // Lancet 2007; 369:1541. - Harris NH, Lloyd-Roberts GC, Gallien R. Acetabular development in congenital dislocation of the hip. With special reference to the indications for acetabuloplasty and pelvic or femoral realignment osteotomy // J Bone Joint Surg Br 1975; 57:46.

- Schwend RM, Pratt WB, Fultz J. Untreated acetabular dysplasia of the hip in the Navajo. A 34 year case series followup // Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999; :108.

- Wood MK, Conboy V, Benson MK. Does early treatment by abduction splintage improve the development of dysplastic but stable neonatal hips? // J Pediatr Orthop 2000; 20:302.

- Shaw BA, Segal LS, SECTION ON ORTHOPAEDICS. Evaluation and Referral for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in Infants // Pediatrics 2016; 138.

- Murphy SB, Ganz R, Müller ME. The prognosis in untreated dysplasia of the hip. A study of radiographic factors that predict the outcome // J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995; 77:985.

- Terjesen T. Residual hip dysplasia as a risk factor for osteoarthritis in 45 years follow-up of late-detected hip dislocation // J Child Orthop 2011; 5:425.

- Lindstrom JR, Ponseti IV, Wenger DR. Acetabular development after reduction in congenital dislocation of the hip // J Bone Joint Surg Am 1979; 61:112.

- Cherney DL, Westin GW. Acetabular development in the infant's dislocated hips // Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989; :98.

- Brougham DI, Broughton NS, Cole WG, Menelaus MB. The predictability of acetabular development after closed reduction for congenital dislocation of the hip // J Bone Joint Surg Br 1988; 70:733.

- Albinana J, Dolan LA, Spratt KF, et al. Acetabular dysplasia after treatment for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Implications for secondary procedures // J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004; 86:876.

- Weinstein SL, Mubarak SJ, Wenger DR. Developmental hip dysplasia and dislocation: Part II // Instr Course Lect 2004; 53:531.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: recommendation statement // Pediatrics 2006; 117:898.

- Lorente Moltó FJ, Gregori AM, Casas LM, Perales VM. Three-year prospective study of developmental dysplasia of the hip at birth: should all dislocated or dislocatable hips be treated? // J Pediatr Orthop 2002; 22:613.

- Larson JE, Patel AR, Weatherford B, Janicki JA. Timing of Pavlik harness initiation: Can we wait? // J Pediatr Orthop 2017.

- Flores E, Kim HK, Beckwith T, et al. Pavlik harness treatment may not be necessary for all newborns with ultrasonic hip dysplasia // J Pediatr Health Care 2016; 30:304.

- Rosendahl K, Dezateux C, Fosse KR, et al. Immediate treatment versus sonographic surveillance for mild hip dysplasia in newborns // Pediatrics 2010; 125:e9.

- Burger BJ, Burger JD, Bos CF, et al. Frejka pillow and Becker device for congenital dislocation of the hip. Prospective 6-year study of 104 late-diagnosed cases // Acta Orthop Scand 1993; 64:305.

- Atar D, Lehman WB, Tenenbaum Y, Grant AD. Pavlik harness versus Frejka splint in treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip: bicenter study // J Pediatr Orthop 1993; 13:311.

- Danielsson L, Hansson G, Landin L. Good results after treatment with the Frejka pillow for hip dysplasia in newborn infants: a 3-year to 6-year follow-up study // J Pediatr Orthop B 2005; 14:228.

- Czubak J, Piontek T, Niciejewski K, et al. Retrospective analysis of the non-surgical treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip using Pavlik harness and Frejka pillow: comparison of both methods // Ortop Traumatol Rehabil 2004; 6:9.

- Carmichael KD, Longo A, Yngve D, et al. The use of ultrasound to determine timing of Pavlik harness discontinuation in treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip // Orthopedics 2008; 31.

- Tiruveedhula M, Reading IC, Clarke NM. Failed Pavlik harness treatment for DDH as a risk factor for avascular necrosis // J Pediatr Orthop 2015; 35:140.

- Hedequist D, Kasser J, Emans J. Use of an abduction brace for developmental dysplasia of the hip after failure of Pavlik harness use // J Pediatr Orthop 2003; 23:175.

- Cashman JP, Round J, Taylor G, Clarke NM. The natural history of developmental dysplasia of the hip after early supervised treatment in the Pavlik harness. A prospective, longitudinal follow-up // J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84:418.

- Nakamura J, Kamegaya M, Saisu T, et al. Treatment for developmental dysplasia of the hip using the Pavlik harness: long-term results // J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007; 89:230.

- Walton MJ, Isaacson Z, McMillan D, et al. The success of management with the Pavlik harness for developmental dysplasia of the hip using a United Kingdom screening program and ultrasound-guided supervision // J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92:1013.

- Lerman JA, Emans JB, Millis MB, et al. Early failure of Pavlik harness treatment for developmental hip dysplasia: clinical and ultrasound predictors // J Pediatr Orthop 2001; 21:348.

- Kitoh H, Kawasumi M, Ishiguro N. Predictive factors for unsuccessful treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip by the Pavlik harness // J Pediatr Orthop 2009; 29:552.

- Ömeroğlu H, Köse N, Akceylan A. Success of Pavlik Harness Treatment Decreases in Patients ≥ 4 Months and in Ultrasonographically Dislocated Hips in Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip // Clin Orthop Relat Res 2016; 474:1146.

- Eidelman M, Katzman A, Freiman S, et al. Treatment of true developmental dysplasia of the hip using Pavlik's method // J Pediatr Orthop B 2003; 12:253.

- Bialik GM, Eidelman M, Katzman A, Peled E. Treatment duration of developmental dysplasia of the hip: age and sonography // J Pediatr Orthop B 2009; 18:308.

- Murnaghan ML, Browne RH, Sucato DJ, Birch J. Femoral nerve palsy in Pavlik harness treatment for developmental dysplasia of the hip // J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93:493.

- Hart ES, Albright MB, Rebello GN, Grottkau BE. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: nursing implications and anticipatory guidance for parents // Orthop Nurs 2006; 25:100.

- Hassan F.A. Compliance of parents with regard to Pavlik harness treatment in developmental dysplasia of the hip // J Pediatr Orthop B 2009; 18:111.

- Kosar P, Ergun E, Gokharman FD, et al. Follow-up sonographic results for Graf type 2A hips: association with risk factors for developmental dysplasia of the hip and instability // J Ultrasound Med 2011; 30:677.

- Luhmann SJ, Bassett GS, Gordon JE, et al. Reduction of a dislocation of the hip due to developmental dysplasia. Implications for the need for future surgery // J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85-A:239.

- Holman J, Carroll KL, Murray KA, et al. Long-term follow-up of open reduction surgery for developmental dislocation of the hip // J Pediatr Orthop 2012; 32:121.

- Rampal V, Sabourin M, Erdeneshoo E, et al. Closed reduction with traction for developmental dysplasia of the hip in children aged between one and five years // J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90:858.

- Carney BT, Clark D, Minter CL.

Is the absence of the ossific nucleus prognostic for avascular necrosis after closed reduction of developmental dysplasia of the hip? // J Surg Orthop Adv 2004; 13:24.

Is the absence of the ossific nucleus prognostic for avascular necrosis after closed reduction of developmental dysplasia of the hip? // J Surg Orthop Adv 2004; 13:24. - Segal LS, Boal DK, Borthwick L, et al. Avascular necrosis after treatment of DDH: the protective influence of the ossific nucleus // J Pediatr Orthop 1999; 19:177.

- Chen C, Doyle S, Green D, et al. Presence of the Ossific Nucleus and Risk of Osteonecrosis in the Treatment of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort and Case-Control Studies // J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017; 99:760.

- Gould SW, Grissom LE, Niedzielski A, et al. Protocol for MRI of the hips after spica cast placement // J Pediatr Orthop 2012; 32:504.

- Desai AA, Martus JE, Schoenecker J, Kan JH. Spica MRI after closed reduction for developmental dysplasia of the hip // Pediatr Radiol 2011; 41:525.

- Tiderius C, Jaramillo D, Connolly S, et al. Post-closed reduction perfusion magnetic resonance imaging as a predictor of avascular necrosis in developmental hip dysplasia: a preliminary report // J Pediatr Orthop 2009; 29:14.

- Aksoy MC, Ozkoç G, Alanay A, et al. Treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip before walking: results of closed reduction and immobilization in hip spica cast // Turk J Pediatr 2002; 44:122.

- Murray T, Cooperman DR, Thompson GH, Ballock T. Closed reduction for treatment of development dysplasia of the hip in children // Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2007; 36:82.

- Senaran H, Bowen JR, Harcke HT. Avascular necrosis rate in early reduction after failed Pavlik harness treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip // J Pediatr Orthop 2007; 27:192.

- Moseley CF. Developmental hip dysplasia and dislocation: management of the older child // Instr Course Lect 2001; 50:547.

- Gans I, Flynn JM, Sankar WN. Abduction bracing for residual acetabular dysplasia in infantile DDH // J Pediatr Orthop 2013; 33:714.

- Sewell MD, Rosendahl K, Eastwood DM. Developmental dysplasia of the hip // BMJ 2009; 339:b4454.

- Kamath SU, Bennet GC.

Re-dislocation following open reduction for developmental dysplasia of the hip // Int Orthop 2005; 29:191.

Re-dislocation following open reduction for developmental dysplasia of the hip // Int Orthop 2005; 29:191. - Wada A, Fujii T, Takamura K, et al. Pemberton osteotomy for developmental dysplasia of the hip in older children // J Pediatr Orthop 2003; 23:508.

- Ertürk C, Altay MA, Yarimpapuç R, et al. One-stage treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip in untreated children from two to five years old. A comparative study // Acta Orthop Belg 2011; 77:464.

- Subasi M, Arslan H, Cebesoy O, et al. Outcome in unilateral or bilateral DDH treated with one-stage combined procedure // Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466:830.

- Sarkissian EJ, Sankar WN, Zhu X, et al. Radiographic Follow-up of DDH in Infants: Are X-rays Necessary After a Normalized Ultrasound? // J Pediatr Orthop 2015; 35:551.

- Engesaeter IØ, Lie SA, Lehmann TG, et al. Neonatal hip instability and risk of total hip replacement in young adulthood: follow-up of 2,218.596 newborns from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register // Acta Orthop 2008; 79:321.