How to let your child fail

Benefits of Natural Consequences | Empowering Parents

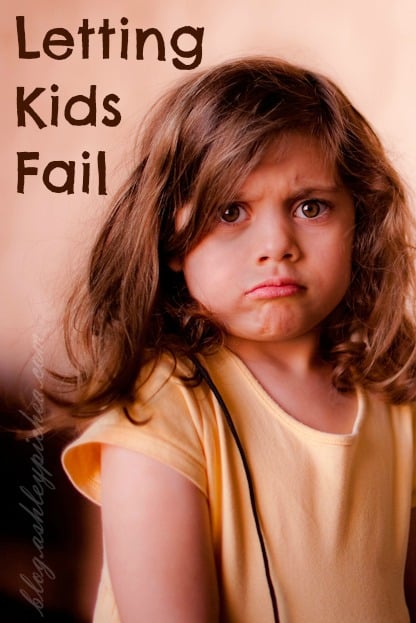

Sometimes you have to let your child fail. Parents often do their kids a disservice when they protect them from natural consequences when they take over for their kids to ensure that their kids don’t fail.

While it’s natural for parents to worry about failure, there are times when it can be productive for kids—and a chance for kids to change for the better.

“Failure is an opportunity to get your child to look at himself.”

But watching your child fail makes you feel helpless, angry, and sad. You worry about everything from your child’s self-esteem and social development to their future success.

In counseling sessions, parents would frequently tell me that they fear their child will fail in life. When I ask them what specifically they’re afraid of, usually, it’s school-related.

They are afraid their child will fail a class or get bad grades. They think that once their child is failing in school, they will fall behind and won’t be able to catch up.

For many parents, this is a crisis. And I understand that.

When a Crisis is an Opportunity

I want to talk about the word, crisis for a minute. The Chinese symbol for crisis is a combination of the symbols for danger and opportunity. Yes, a crisis presents danger, but it also presents opportunity.

In a crisis, parents see the danger part very clearly, but often don’t see the opportunity part. They don’t see that their child has the opportunity to learn an important lesson. The lesson might be about the true cost of cutting corners, what happens when he doesn’t do his best at something, or the real consequences for not being productive.

The crisis might also be a chance for your child to learn the cost of misleading and lying to his parents about how much work he’s actually done or what grades he’s receiving.

Don’t Be a Martyr for Your Child

Many of the parents I’ve worked with are uncomfortable taking the approach of letting their child fail. Therefore, instead of allowing their child to fail, they may try to get the teacher to change the grade. Or they may do the work for their child.

Therefore, instead of allowing their child to fail, they may try to get the teacher to change the grade. Or they may do the work for their child.

But sadly, what their child learns is that they don’t have to take responsibility for their ineffective behavior. They learn that somebody else is going to fight for them.

These parents are playing what I call the martyr parenting role.

Martyr parents are overly anxious when their children feel any discomfort or distress. And, to cope with their own anxiety, martyr parents will do whatever it takes to eliminate their child’s distress. In the process, these parents rob their kids of the opportunity to learn coping skills.

Related content: Mother or Martyr: Are You Doing Too Much for Your Child?

Don’t Shield Your Child from Natural Consequences

If your child chooses not to study enough and gets a failing grade, that’s the natural consequence of her behavior. And she should experience the discomfort that results from her behavior.

Let me be clear: when you try to change the actions of people around your child so she doesn’t face the natural consequences of her actions, she learns the wrong lesson. She learns that if she screws up enough, Mom and Dad will take care of her. She learns that Mom and Dad will handle the teacher for her.

And, to make matters worse, she’s doesn’t learn the math or the science or whatever it is she’s been avoiding.

Related content: 5 Natural Consequences You Should Let Your Child Face

The Perils of Using Power to Solve Problems

When Mom and Dad get the teacher to change a grade, your child learns that power can solve his problems. He learns that power can be a substitute for responsibility, and that power trumps responsibility. That’s not a good lesson.

In fact, he learns that the power of being manipulative and threatening is more valuable than actually being accountable and doing his work competently.

But in the real world—in the adult world—real power comes from taking responsibility for one’s actions, not avoiding them.

“But the School is Being Unfair”

Many parents have reasons to justify their defense of their child. They may cite the unfairness of the school system, their child’s learning difficulties, the principal’s attitude, or the prior history of their child at the school.

I understand that those things can be very real. It may be easier to fight with the teacher than it is to fight with your child. It may be easier to change the teacher—or even the school rules—than to get your child to change.

But if your child didn’t do his homework, ignored a project that was due, or lied and misled you or his teacher, the fact remains that it’s his responsibility to experience the natural consequences of his actions. And the biggest consequence is that your child has failed.

Failure is Not the End of the World

Failure is not the end of the world. It’s a lesson. It’s a gauge of how she’s doing. And it’s designed to help her see that she’s not making the grade. If she’s failed something, she needs to solve the problem responsibly.

If she’s failed something, she needs to solve the problem responsibly.

Confront the Lying

I need to say a word about lying. If your child is lying or being dishonest about doing his homework, you should ask yourself what else is he being dishonest about.

When he’s supposed to be studying after school, what is he really doing? This raises important questions because we know if somebody is sneaky in one area, they may be sneaky in other areas. You need to investigate and open your eyes to the possibility that something else might be going on.

Related content: How to Give Kids Consequences That Work

Solve the Problem by Addressing the Problem

I believe if your child fails a subject or even fails the year, and if you’re addressing the problem, then you’re starting to solve the problem.

Failure is an opportunity to get your child to look at himself and make some changes.

Part of parents’ sensitivity to this is that if their child fails, they feel like they’ve failed, too. And parents don’t want to feel like they’ve failed. I understand that.

And parents don’t want to feel like they’ve failed. I understand that.

I know that it’s tough to be a parent who works hard to raise a child, only to have that child fail. You ask yourself, “What more can I do?”

But that’s the wrong question. The question should be, “What more can my child do?”

So, instead of asking, “What am I not doing as a parent?” Ask, “What is my child not doing as a student?”

Once you present the problem in those terms, you can begin to create effective change.

Feeling Discomfort Is OK

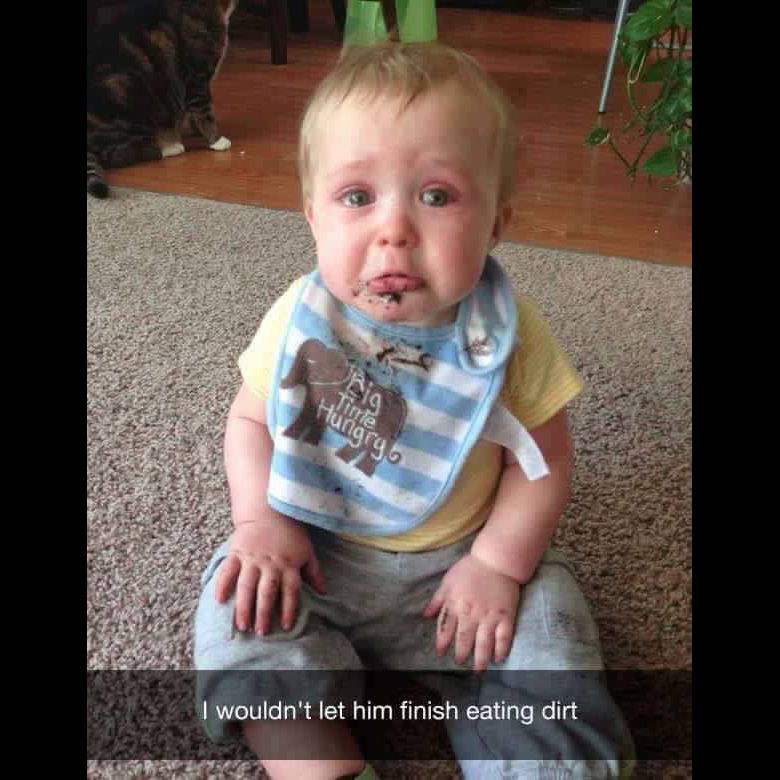

When we talk about failure and what your child can learn from it, we’re really talking about the benefits of allowing your child to feel discomfort. And when I say discomfort, I mean worry, fear, disappointment, and the experience of having consequences for your actions.

I think that most parents really don’t want their kids to feel uncomfortable about anything, even when they know that sometimes it’s beneficial for their child to pay the price for their choices. And so some parents will fight with the school, they will fight with other parents, they will fight with their kids. Ultimately, they will fight with anybody or anything to claim their child’s right never to feel uncomfortable.

And so some parents will fight with the school, they will fight with other parents, they will fight with their kids. Ultimately, they will fight with anybody or anything to claim their child’s right never to feel uncomfortable.

Somehow in our culture, protecting our kids from discomfort—and the pain of disappointment—has become associated with effective parenting. The idea seems to be that if your child suffers any discomfort or the normal pain associated with growing up, there’s something you’re not doing as a parent. Or that somehow your child is a victim.

Personally, I think that’s a dangerous trap for parents to fall into. While I don’t think situations should be sought out to make a child uncomfortable, I do think if that a child is uncomfortable because of some natural situation or consequence, you should not interfere.

Look at it this way: when a child is feeling upset, frustrated, angry, or sad, they’re in a position to develop some important coping skills.

For example, they learn how to prevent a situation from happening again. So, if your child doesn’t do his homework and then is embarrassed because he is called on in class and doesn’t know an answer, then he should learn to do his homework next time in order to avoid future embarrassment. Remember, the problem isn’t that he feels embarrassed, the problem is that he isn’t doing his homework.

Kids Need to Build Up a Tolerance for Discomfort

Kids need to build up a tolerance for discomfort, an emotional callous if you will. Building this tolerance for discomfort is important because discomfort is a big part of life. We have to learn to sit in traffic, to lose a game, or to get passed over for a promotion. Life is naturally full of failures, even for the most successful people.

Your child needs to be able to learn how to manage these situations in order to develop a tolerance for them. And make no mistake, if he doesn’t learn to tolerate discomfort, he’s going to be a very frustrated adolescent and adult.

So I advise parents to let your kid wait in line—don’t try to figure out how to cut ahead. When your child is starting to get frustrated, point it out. You can say:

“Yeah, I know it’s frustrating to wait, but this is the way we have to do it.”

Entitled Kids

When you shield your child from discomfort, he learns that he should never have to feel anything unpleasant in life. As a result, he develops a false sense of entitlement.

He learns that he doesn’t have to be prepared in school, because his parents will complain to the teacher, who will stop calling on him or expecting his homework to be in on time.

He learns that his parents will raise their tolerance for deviance. And his teacher will expect less of him because of his parents’ intervention.

Ultimately, he learns to confront a problem with power rather than dealing with it through responsibility and acceptance.

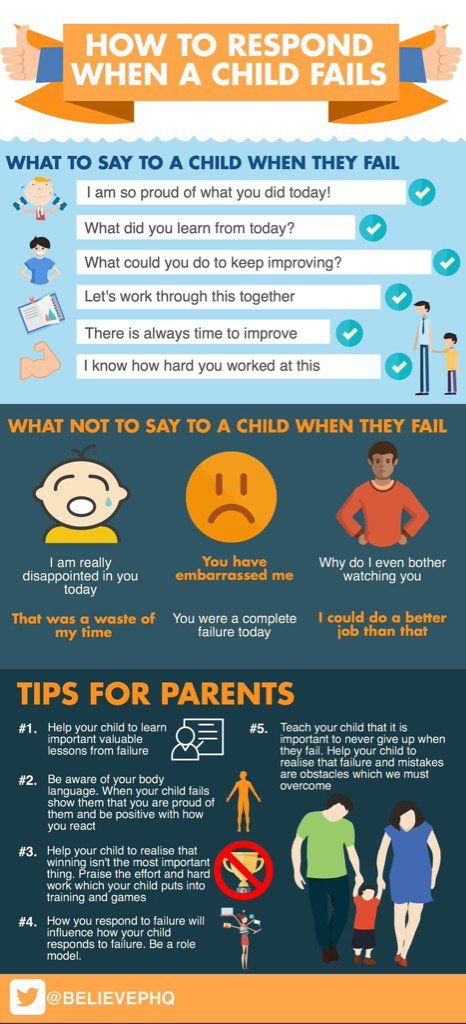

How to Talk to Your Child About Failing

As a parent, you want to coach your child to better deal with natural consequences and failures. Calm and thoughtful coaching can put her in a better position to learn the lessons of failure. It’s just like in sports, where the coach teaches the team how to respond constructively to a loss so that the team has a better chance to win next time.

Calm and thoughtful coaching can put her in a better position to learn the lessons of failure. It’s just like in sports, where the coach teaches the team how to respond constructively to a loss so that the team has a better chance to win next time.

When things are calm for both you and your child, I recommend focusing the conversation on having your child address three key questions: (1) “What part did you play in this?”; (2) “What are you going to do differently next time.”; and (3) “What did you learn from this?”.

1.

“What part did you play in this?”You want your child to learn what part he played in the failure because, after all, he can only change his part. The lesson begins with identifying his part.

Your child might say, “I don’t know what part I played, Dad.” You can respond by saying:

“Well, let’s think about it. Where did you get off track? Where did things go wrong for you?”

If your child doesn’t know, you can say:

“Well, it seems to me you got off track when you didn’t have your homework ready when your teacher called on you. The part you played was not being prepared. And the solution to that is getting prepared.”

The part you played was not being prepared. And the solution to that is getting prepared.”

Your child may agree with you, or he may try to offer some defense. But any defense that’s offered is not going to be legitimate as long as you’re speaking in the context of “What part did you play?” You just need to point out what really happened. You may have to say one or more of the following:

“Well, it seems to me like you’re making an excuse for not having your homework done.”

“Seems to me you’re blaming me for not having your homework done.”

“It looks to me like you’re blaming your teacher for not having your homework done.”

Be aware that your child may blame the teacher. And you may agree that the teacher is a problem. I realize that there are both effective and ineffective teachers.

But consider this: when is your child going to learn to deal with ineffective teachers? Where do you think your child is going to learn to deal with injustice or unfair bosses?

2.

“What are you going to do differently next time?”

“What are you going to do differently next time?” Your child needs to have a plan for what to do differently next time. Say to your child:

“What are you going to do differently the next time when you have to do your homework?”

Or:

“What are you going to do differently next time so that if your teacher calls on you, you won’t get embarrassed?”

Or:

“What are you going to do differently next time to pass the test?”

This is a big question in this conversation with your child because it gets him to see other, healthier ways of responding to the problem.

3.

“What did you learn from this?”Work with your child to help ensure he learns the right lesson. Say:

“What did you learn from being embarrassed when your teacher called on you?”

“What did you learn from not passing the test?”

Let him know that failing is part of the learning process at times. Failing may be a problem, but failing to learn from failure is a much bigger problem.

Failing may be a problem, but failing to learn from failure is a much bigger problem.

Conclusion

Part of learning—for everyone—involves feeling uncomfortable at times. Part of loving your child responsibly means that you need to let him feel discomfort, and even fail, as long as he’s learning how to be accountable for his actions in the process. And try to appreciate the opportunity that a crisis and its natural consequences present to your child.

How to Let Your Children Learn From Failure

People have a complicated relationship with failure. Most of us fear it for ourselves, and for our kids. But we also know kids are supposed to learn from failure. So the question for most parents is how do we avoid falling into the trap of being overbearing helicopter parents on the one hand and hands-off free-rangers on the other? How do we find the sweet spot?

When it comes to the obvious challenges our children face (a big test, for instance), we tend to wonder which is better — let them fail or not? The problem is, while no one will die from failing a test or even a course, it nevertheless feels terrifying for both kids and parents. Real consequences loom – not graduating, not being accepted to college, even not getting reasonable car insurance (which, at least with some companies, is cheaper for students with a B average or higher) – and they are daunting enough that many parents intervene to prevent failure.

Real consequences loom – not graduating, not being accepted to college, even not getting reasonable car insurance (which, at least with some companies, is cheaper for students with a B average or higher) – and they are daunting enough that many parents intervene to prevent failure.

But it doesn’t end there. We put structures in place to prevent our kids from even coming close to a failure. Before we know it, we have elaborate systems for checking homework, monitoring grades and assignments, contacting teachers, even checking up on class participation.

While the basic idea of learning from failure is supported by evidence, the sink-or-swim method doesn’t really work. Failing is only productive when two things are true: first, the person who fails actually learns something from it and is thus motivated to try again, and second, the failure doesn’t permanently close future doors.

Ironically, video games, one of the things parents often fight against in their quest to prevent failure, offer some real insight into a third way. When my son Rett was 10, he would do anything to play Cut the Rope, an app based on the science and math principles of angles and velocity, so I downloaded it for him as a treat. In the game, an adorable little monster named Om Nom loves candy, and the player has to cut the rope the candy dangles from in exactly the right place so it falls into Om Nom’s mouth. The second I handed the phone to Rett, he was off, going so fast I couldn’t even follow his moves.

When my son Rett was 10, he would do anything to play Cut the Rope, an app based on the science and math principles of angles and velocity, so I downloaded it for him as a treat. In the game, an adorable little monster named Om Nom loves candy, and the player has to cut the rope the candy dangles from in exactly the right place so it falls into Om Nom’s mouth. The second I handed the phone to Rett, he was off, going so fast I couldn’t even follow his moves.

“Slow down!” I protested. “I can’t even see what you’re doing!”

“What, Mom? I’m just playing it the way you’re supposed to.”

What I quickly realized is that he was cutting the rope in the wrong place, a lot. Om Nom was sad every time, but it soon became clear Rett wasn’t fazed. He had realized it didn’t matter, so he tested and retested, figuring out as he did where to cut next. Unencumbered by the fear of failure, he could progress through the game rapidly, getting better with each attempt, incorporating as much learning from the misses as the successes.

When Rett turned 13, I found another constructive way to let him fail. My husband and I reasoned that even if he just learned to make 10 things for dinner by the time he was 18, he’d leave our house knowing how to make 10 meals for himself, and he could definitely survive like that.

I didn’t set him loose and say, “Okay, great, call me when dinner’s ready!” Instead, I pulled out the recipes I thought would be good for him to start on, the ones without a ton of ingredients or complicated steps and techniques. From that curated pile, he chose what he wanted to make each week.

I made a few mistakes at first. I got distracted and disappeared while Rett was cooking – he needed guidance and without it, burned something. I got too involved. He didn’t know proper knife techniques so when he almost cut his finger I rushed in and soon I was cooking and he was watching. There was some foundational knowledge he was missing, like why the order of adding ingredients matters.

On the nights he cooked, dinner took a long time. The kitchen became messier than I’d like, and quite frankly the food was not as good. But I noticed that if Rett asked me a question and my answer turned into my taking over, he would disengage, sometimes completely leaving the kitchen.

The kitchen became messier than I’d like, and quite frankly the food was not as good. But I noticed that if Rett asked me a question and my answer turned into my taking over, he would disengage, sometimes completely leaving the kitchen.

So my husband and I created some rules for ourselves. When Rett’s cooking, we decided, one of us must be present to answer his questions. But we need to be doing something else, too – paying bills, reading an article, or doing some work – so we are not there exclusively to oversee him. We need to stay on the opposite side of the counter. We also need to suck it up if a meal isn’t all that good or the kitchen is messy.

Slowly but surely, Rett is learning to be a capable cook. In a way, potentially eating cereal for dinner, in the case of a complete failure, is the easy part. The hard part is the work we need to do with ourselves to productively let go and trust the structured process of growth.

Often the solution is to let our kids fail – in small ways. Try taking a step back. Be willing to be needed differently. Give feedback and guidance rather than answers. Ask questions that help your child reflect on what they want, who they are, what they care about, how they feel, and, ultimately, what they should do as a result.

Try taking a step back. Be willing to be needed differently. Give feedback and guidance rather than answers. Ask questions that help your child reflect on what they want, who they are, what they care about, how they feel, and, ultimately, what they should do as a result.

When it comes to things like school, we can take the same approach. Take a risk on the small things, like homework. Put your kid in charge and assume the role of coach. Remember that the consequences of messing up one assignment, or even a few are not life-altering. Let your child build their own routine, ask for help and engage with their teacher. Spend your time asking what your child’s goals are, what their plan is to achieve them, and how progress is going. In doing so you will help them build and practice the lifelong skills they need to be independent and successful in their day to day activities, as well as the high stakes moments. Step in only when it’s clear that the entire house will be on fire if you don’t intervene. Then once you’ve worked together to put out the flames, step aside once again.

Then once you’ve worked together to put out the flames, step aside once again.

My husband and I, like all parents, like being needed by our child. And the fact is, when kids are self-directed, the role of the parent changes. But from my experience of decades of teaching and parenting, that’s the best way to prepare them, and in time, we figure out our new place, too.

Contact us at [email protected].

What will failures teach? How to help a child learn to lose

Failure, disappointment, defeat - all this will definitely be in the life of our children. How and why to teach a child to cope with failures, says psychologist Anna Skavitina.

Anna Skavitina, psychologist, analyst, member of the IAAP (International Association of Analytical Psychology)

When a child experiences disappointment and failure, it is difficult for parents to resist emotions. Seeing your child fail — lace up his shoes with difficulty, spell a letter incorrectly, fail to solve a problem, fail to make friends, or no one wants to sit at a desk with him — is one of the most difficult situations in parenthood.

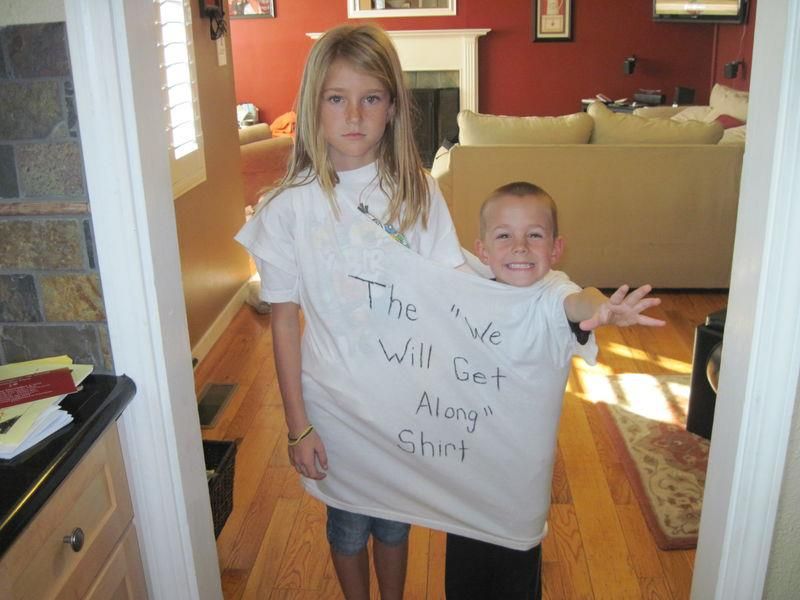

Many mothers and fathers go out of their way to reduce the chance of their children encountering a losing situation. For example, for a birthday, children are invited to invite the entire kindergarten group or the entire class so that no one is offended, and if not everyone was invited, then it is better to lie and hide the very fact of the celebration. At children's holidays and even competitions, the organizers try to set things up so that "friendship wins", or generally avoid games where someone will be excluded at least for a moment. Parents do not want their children to feel bad, even if only for a short time.

In this way they try to help children avoid psychological trauma and low self-esteem. And they protect themselves from dealing with the consequences of childhood disappointment. The irony of this careful approach is that small disappointments resulting from failure are actually good for children.

The benefits of failure

Learning and talking about failure helps children develop coping skills, emotional resilience, creative thinking, collaboration, and other important skills needed to succeed in life. Parents often view failure as a source of pain rather than an excuse to say, “You can handle this! Try it, I'll help, if anything!" Unfortunately, parental overprotection, especially complicated by material advantages over other families, can do a disservice to the child.

Parents often view failure as a source of pain rather than an excuse to say, “You can handle this! Try it, I'll help, if anything!" Unfortunately, parental overprotection, especially complicated by material advantages over other families, can do a disservice to the child.

Moms and dads who do almost everything for their children, repeating: “You are the best, you are unique by the fact of birth, we will make sure that you do not know the need for anything and always feel like a million!”, unable to endure momentary failure and by their actions often achieve that the child does not want to do anything in this life, except to spend parental capital.

He expects that all the people he meets on the way will be fascinated by him and his incomprehensible virtues, and turns out to be ... disappointed and traumatized, because people are not interested in him in any way, the apartment does not clean itself, work does not work, and even domestic staff does not create a magical atmosphere of complete fulfillment of desires. And how to change it, he is not too clear.

And how to change it, he is not too clear.

Coping with disappointment

A review of 200 studies published in Psychological Science in the Public Interest found that the high self-esteem many parents strive to instill in their children, believing that it will help them to believe in themselves and protect them from disappointments and failure does not encourage children to get better grades or to do something for their career. It is the situations of success that lead to the fact that you feel good, and not vice versa. The Journal of Social Science and Clinical Psychology published data from an experiment showing that students who did poorly in college and tried various ways to increase their self-esteem instead of doing homework only made themselves worse.

Unfortunately, we cannot always be in the place where the child fails, we cannot protect him from all troubles and worries, but we can teach him to cope with the consequences of failures and disappointments. For example, when your child says that the guys did not take him to play on the playground or at school break, you can not go and deal with this situation yourself, asking the children: “Why don’t you play with him? Who taught you this?" — I have seen this many times! It is better to listen carefully to the child, be sure to ask: "How did you feel?", to ask what can be done another time in such a situation. Don't fixate on inappropriate answers, say, "Yes, that's a possibility, what else?" Offer a few of your options - this is called "brainstorming": it allows for the voicing of even the most crazy options without criticism. Have the child consider the pros and cons of each approach. Not everything that seems simple and obvious to you is simple and obvious to your child.

For example, when your child says that the guys did not take him to play on the playground or at school break, you can not go and deal with this situation yourself, asking the children: “Why don’t you play with him? Who taught you this?" — I have seen this many times! It is better to listen carefully to the child, be sure to ask: "How did you feel?", to ask what can be done another time in such a situation. Don't fixate on inappropriate answers, say, "Yes, that's a possibility, what else?" Offer a few of your options - this is called "brainstorming": it allows for the voicing of even the most crazy options without criticism. Have the child consider the pros and cons of each approach. Not everything that seems simple and obvious to you is simple and obvious to your child.

How to teach a child to lose

Any failure brings disappointment, sadness, regret, anger. Our task is to teach the child not to avoid these feelings, because they are an integral part of our life and mental development, but to learn to perceive them adequately. Experiences of failure can be converted into learning experiences that improve your child's ability to succeed in the future. Henry Ford once said, "Failure is just an opportunity to start acting again, but smarter."

Experiences of failure can be converted into learning experiences that improve your child's ability to succeed in the future. Henry Ford once said, "Failure is just an opportunity to start acting again, but smarter."

Children learn to overcome failure by watching their parents do it. If mom and dad get furious at their own failures, then the child concludes that this is the way to deal with defeat. No matter what you say, children “take off the sheet” more, that is, they do what they see, and not what they hear. If you make a mistake, then say it out loud: “Oh, I don’t have time to finish the work on time, it’s sad. We must sit down and calculate the time correctly in order to be in time next time!” This is how children understand that adults are not perfect either, they make mistakes, experience unpleasant feelings, but try to cope with it.

Encouragement and praise are powerful stimuli for the development of a child. Little children are ready to repeat their first steps again and again, seeing how happy their mother is. If a mother praises for efforts, for experience, and not just like that, then the child's motivation increases. He, while unconsciously, is already learning to set a goal in order to get the same result - his mother's smile. If the child took the first steps, but fell, it is important to support him with words, wait for him to stand up and rejoice at the next steps together. So, starting from a year, we teach children to set goals and overcome failures by trying again and again.

If a mother praises for efforts, for experience, and not just like that, then the child's motivation increases. He, while unconsciously, is already learning to set a goal in order to get the same result - his mother's smile. If the child took the first steps, but fell, it is important to support him with words, wait for him to stand up and rejoice at the next steps together. So, starting from a year, we teach children to set goals and overcome failures by trying again and again.

The same technique can be extended to other activities of the child. Did you ride a bike (skate, ski) and fell? Support, say: “Yes, it hurts, it’s a shame, but you need to try again!” Problem not being solved? “Yes, it’s sad, of course, but when should it be done? Are there options? What have you already tried? Did you draw a diagram? What else is possible?" It is very interesting to ask a child why something did not work out for him, often his version can surprise you. For example:

- Why do you have "two" in math?

- The teacher picks on me.

- Did you do your homework?

— Why? It's all clear to me.

Do not immediately rush to save the child, stay close to him, discuss what is happening, his feelings and actions. Often this is enough for him to cope with the situation and get a new successful experience. His self-esteem will just grow, but will be supported by a real, albeit small, achievement.

Teach your children to manage their expectations and not set the bar high. When you reason that you will absolutely go on a picnic on Sunday and develop a detailed trip plan, talking with your child about it for a whole week, but then plans change, do not be surprised if his frustration is so high that it will be difficult to cope with it. Consider most situations as probable, as pleasant possibilities, not as a fact that will definitely happen.

Learn to see the positives in different scenarios. “We will go on a picnic in the forest if the weather is good, and if the weather is bad, then we need to think about what we will do in this case. Do you have any suggestions?" "If you pass the exams to this school, then we will go there in the morning together, and if it doesn't work out, then you will stay in the old school or you will have a chance to pass the exams in another, what do you think is better?"

Do you have any suggestions?" "If you pass the exams to this school, then we will go there in the morning together, and if it doesn't work out, then you will stay in the old school or you will have a chance to pass the exams in another, what do you think is better?"

It is important that the child knows that being first is not the most important thing in the world, that your love does not depend on it. This knowledge appears when you praise him not so much for winning, but for his efforts and diligent attitude to business, and when you win, ask what exactly he did to achieve this. Talk to your child about their strengths. Such conversations can help build self-esteem even in the smallest. Discuss how you can make strengths even stronger. How can abilities be developed? And what was missing in a situation of failure?

Understanding when a child needs your help

By trying over and over, our children learn about patience, perseverance, and a sense of pride in their accomplishments. But you need to determine what level of failure the child can tolerate. Often the expectations of parents from children do not correspond to their age or level of development. And the situation turns out to be so difficult for the child that it is necessary not to teach him to cope with failures, but to radically change the situation itself and its requirements.

But you need to determine what level of failure the child can tolerate. Often the expectations of parents from children do not correspond to their age or level of development. And the situation turns out to be so difficult for the child that it is necessary not to teach him to cope with failures, but to radically change the situation itself and its requirements.

For example, a child is brought to a psychologist with a request - there are no friends in the class, teach them to make friends and cope with failures, increase self-esteem, she suffers. The girl is studying in the second grade at two schools at the same time: in Russian before lunch and in English in the afternoon. He studies hard and poorly, he does not cope with the lessons in any school. The child himself is not particularly fast by nature: he thinks for a long time, slowly dresses. The girl does not have the strength to be friends with anyone, she would survive. And the parents say: “Do the other children manage somehow?”

It is difficult for them to see that the child's resources are not enough for such an intensive workload, and it is a pity to leave school. There are situations when a child definitely needs your help. This is not the time or place to learn how to deal with failure. Parents should get involved if:

There are situations when a child definitely needs your help. This is not the time or place to learn how to deal with failure. Parents should get involved if:

-

The situation is too humiliating for him. He forgot his tracksuit and can let his team down. You can, of course, start a "lesson of responsibility" and prove by example how important it is to be responsible. But it's better to just help the child and bring clothes. And the lesson will be held later.

-

Your child is in real danger. For example, he tries to join the game of older guys climbing onto neighboring roofs.

-

Your child is being bullied in real life or online. And this is not a one-time conflict, but a long process.

Sometimes when parents ask the question, “How can I teach my child to deal with failure,” they are really asking, “How can I deal with my fear that my child will be disappointed and start crying and stamping their feet? I am ready to do anything so that he does not scream so loudly and for a long time, and I do not feel like a bad parent. Know if the child is disappointed and screams, and you breathe deeply and endure, hug him or just sit next to him, talk about what is happening or be silent - you are an excellent parent, much better than the one who, in a panic, tries to quickly do everything for the child or give him anything, as long as no one has any negative emotions. There is no experience of disappointments - there is no experience of overcoming and learning, because it will not arise by itself.

Know if the child is disappointed and screams, and you breathe deeply and endure, hug him or just sit next to him, talk about what is happening or be silent - you are an excellent parent, much better than the one who, in a panic, tries to quickly do everything for the child or give him anything, as long as no one has any negative emotions. There is no experience of disappointments - there is no experience of overcoming and learning, because it will not arise by itself.

Read also:

14 rules for a good argument: how to teach your child to defend his point of view

7 ways to deal with learned helplessness syndrome

Why every child (and even some adults) needs an imaginary friend Konstantin, ESB Professional, Aaron Amat, Dean Drobot/Shutterstock.com

psychologyeducation

To be successful, you need the opportunity to fail

You can be an excellent conversationalist, be able to listen, and most importantly, hear the people with whom you communicate, and at the same time be absolutely deaf to your own inner voice: not accepting your needs and not understanding yourself. Why is it so important to be able to do this and how to teach your children to be in harmony with themselves? The expert answers "Oh!" psychologist Anna Skavitina.

Why is it so important to be able to do this and how to teach your children to be in harmony with themselves? The expert answers "Oh!" psychologist Anna Skavitina.

Anna Skavitina, psychologist, analyst, member of the IAAP (International Association of Analytical Psychology), supervisor of the ROAP and the Jung Institute (Zurich), expert of the Psychology journal

One day a psychologist colleague started his training session with a hundred parents asking, “Are you happy in life? Happy, raise your hands!” - no one raised their hand. “What can you teach your children then?” he continued. During the first break, many parents left the hall, realizing that they were hopeless and they did not seem to have a chance to raise their children normally.

The fact is that parents have a unique task: many of us have to teach our children what we ourselves cannot do. For example, to teach to swim, even if we ourselves are afraid of water, or to try to make children happy, while being dissatisfied with our own lives. Oddly enough, but some parents are quite successful in this. Why? Probably because these parents themselves suffer and think a lot about what they lack in order to swim, be happy, feel understood and accepted in society, and realize their inner potential. And also about how to create conditions for this for your children, what can be outsourced: for example, find a coach, a teacher, a psychologist for a child and yourself, and what outsourcing will not work and you will have to do it yourself.

Oddly enough, but some parents are quite successful in this. Why? Probably because these parents themselves suffer and think a lot about what they lack in order to swim, be happy, feel understood and accepted in society, and realize their inner potential. And also about how to create conditions for this for your children, what can be outsourced: for example, find a coach, a teacher, a psychologist for a child and yourself, and what outsourcing will not work and you will have to do it yourself.

In order for a person to think about his inner potential, about revealing his abilities, about the desire to create, he must have enough energy for this. Personal self-realization has a direct connection with a sense of self-worth, satisfaction with life, success, with a sense of happiness. If a person lacks basic things: food, sleep, clean air, space for life, security, then no self-realization worries him.

Maslow's classical pyramid of needs tells us that all previous levels of needs must be satisfied in order to reach the highest, to the top of the pyramid - the need for self-realization. Therefore, the best thing that parents can do in order to support the child's need to realize their inner potential is to create conditions for satisfying all the first levels of needs.

Therefore, the best thing that parents can do in order to support the child's need to realize their inner potential is to create conditions for satisfying all the first levels of needs.

After two basic levels of needs - physiological and safety, comes the level of belonging and love - for all people, and especially for children, it is important to feel part of something greater than ourselves, for example, part of your family, it is important to love and be loved . Parents should have time to nourish the child with love, care and a sense of belonging before he has to make a serious independent breakthrough: go to kindergarten, perform at a concert, go to camp without mom and dad. Plan your days so that before important social events for your child, you spend more time with him than usual. This is necessary so that all his strength does not go into a real or fantasy struggle for his mother's love, so that he feels that this territory has been conquered: mom and dad love and support him.

Next step: need for respect. Children are the lowest link in the family hierarchy. They are loved, but not always understood that respect is needed not only by the older generation, but also by the younger one.

For many parents, the fact that their child is respected causes surprise and bewilderment. Respect is, after all, a feeling of respect, reverence, attitude towards a person based on the recognition of his merits, importance, significance and value. Yes, adults are valuable people, they do important work for the family and society, they can and should be respected at least for this. But why respect a child, why is he valuable and significant?

“Quickly get up and put away your toys. Immediately. It's time to eat, I've already set the table!" - Behind this ordinary phrase is the need of the parent to confirm his importance and downplaying the importance of what the child is doing and his needs. I cooked food and set the table - valuable and significant, I demand respect, I am valuable and significant..jpg) In order to feel my worth, I need to do something and get confirmation from those around me: "Mom - well done!". Play is not valuable and not significant, you are not valuable and not significant. Children are offended, feel humiliated, come up with strategies for protection and survival, wait for their turn to become older and break away from the younger ones, to show them that they are not valuable and not significant. Yesterday in the sandbox, a four-year-old child said to a two-year-old: “Go away, you are a baby, you should not interfere with your elders doing important work!” If we choose to respect a child not because he has earned the right to respect, but because he is a person, a person, and has the right to his opinion and desires, then we teach the child to respect himself, parents, and other people, and also allow him to express his point of view and defend his rights in life.

In order to feel my worth, I need to do something and get confirmation from those around me: "Mom - well done!". Play is not valuable and not significant, you are not valuable and not significant. Children are offended, feel humiliated, come up with strategies for protection and survival, wait for their turn to become older and break away from the younger ones, to show them that they are not valuable and not significant. Yesterday in the sandbox, a four-year-old child said to a two-year-old: “Go away, you are a baby, you should not interfere with your elders doing important work!” If we choose to respect a child not because he has earned the right to respect, but because he is a person, a person, and has the right to his opinion and desires, then we teach the child to respect himself, parents, and other people, and also allow him to express his point of view and defend his rights in life.

Many problems with inadequate, from the point of view of parents, behavior of a child are solved if they begin to be treated with respect. This gives the child the opportunity to release more strength to learn about the world around him and himself. Children whose opinions are taken into account know themselves much better and rarely worry about the question “what should I be when I grow up?” From early childhood, they listen to themselves, make decisions on their own, get disappointed, bear responsibility, and therefore it is easier for them than for children for whom their parents decide everything. They risk being themselves, do not hide their feelings and desires.

This gives the child the opportunity to release more strength to learn about the world around him and himself. Children whose opinions are taken into account know themselves much better and rarely worry about the question “what should I be when I grow up?” From early childhood, they listen to themselves, make decisions on their own, get disappointed, bear responsibility, and therefore it is easier for them than for children for whom their parents decide everything. They risk being themselves, do not hide their feelings and desires.

The next levels are cognitive and aesthetic needs. To know, to recognize, to enjoy the beauty of the world, strength and desire are also needed. The task of parents is to provide a developing environment for research and creativity. This does not mean that each child needs to create a personal physical or chemical laboratory at home, fill his room with materials for creativity: plasticine, paints, glue, colored paper, and so on. Although this also does not hurt if the parents have such an opportunity, and the child himself wants not only to have it, but also to do something with it. To create a developing environment is to follow the child, communicate with him, answer his questions, without referring to "grow up - you will learn." It is important to be guided by the principle "If the child asked a question, then he is ready to receive an answer." You are not obligated to always tell him all the ready-made answers. You remember, we ourselves are far from being magicians, we don’t know and can do everything at all, our task is to support the child’s interest in the search for truth. Often the question itself develops us more than the answer received from someone.

To create a developing environment is to follow the child, communicate with him, answer his questions, without referring to "grow up - you will learn." It is important to be guided by the principle "If the child asked a question, then he is ready to receive an answer." You are not obligated to always tell him all the ready-made answers. You remember, we ourselves are far from being magicians, we don’t know and can do everything at all, our task is to support the child’s interest in the search for truth. Often the question itself develops us more than the answer received from someone.

Freedom of choice is another important factor in the development of the child and the manifestation of oneself, which leads to an understanding of responsibility for one's actions and their consequences. It starts small: I want to eat, I don’t want to, today I will choose clothes for the garden myself, then I will decide whether I will draw or sculpt, and tomorrow I will understand what I really want to do in my life, and what I don’t want to.

Support your children's hobbies, their choice, but insist on continuing classes if you see that the child enjoys the process, but sometimes he lacks the strength, experience, and ability to cope with the difficulties that stand in his way. For example, if a child is engaged in a sports section or a music school with pleasure, and not because the whole family forces him, but suddenly decided to quit classes because something is not working out for him, support him, go back to the step "Let's feed the child with love and care”, help choose a strategy for overcoming difficulties, rejoice with him when he made a leap forward. Then you can step back a little to give him the opportunity to do something completely by himself.

Activities that a child hates, but parents believe that it is necessary, “because all the children around are doing this”, do not lead to any self-realization and the opportunity to express themselves. This is the path to the neuroticism of the child and his apathy, unwillingness to do nothing, not to strive anywhere. Classic plot: “Mine doesn’t want anything, no music school, no English, no chess, no study. How to make it develop? At one time, it was violence, the cramming of knowledge, the denial of minimal freedom of choice that contributed to this situation.

Classic plot: “Mine doesn’t want anything, no music school, no English, no chess, no study. How to make it develop? At one time, it was violence, the cramming of knowledge, the denial of minimal freedom of choice that contributed to this situation.

Another important factor for successful self-expression is the possibility of failure. It may seem strange, but it is failures that often give more useful experience for our development than success. Failure is a serious part of the story of success and self-realization in life. It is important to give the child the opportunity to have negative experiences, make mistakes and learn from them, draw conclusions, overcome the difficult feelings associated with them and move on. Successfully overcoming setbacks and careful debriefing strengthen your child's character, add stress resistance and allow him to move forward, realizing that failures may lie in wait for him.

If you need so many things for self-realization and successful search for your inner treasures, then how could it be possible for ever-hungry artists or poets, research scientists to achieve this? It turns out that if in a person’s life, especially in his early childhood, there was a fairly long period of saturation of all needs, that is, he was fed, provided security, loved, then for some time during his life a person is ready to live without this and not fall into complete despondency, supporting itself with internal motivation, the desire to do what seems important to him right now, even if it does not bring instant results, is ready to postpone pleasure for later.