Oral vitamin k dose

Oral Vitamin K Regimen for Newborns

Welcome to the Evidence Based Birth® Q & A Video on Oral Vitamin K

Today’s video is all about evidence on oral Vitamin K regimens. You can read our disclaimer and terms of use.

In this video, you will learn:

- The main reason why oral Vitamin K might not be as effective as the shot

- The most effective oral Vitamin K regimen

- Reasons why some countries don’t use oral Vitamin K

Click Here to get your Free Video Series and Handout!

Links and resources:

- Learn more by reading the Evidence Based Birth® Signature article on Vitamin K

- References

- von Kries, R., A. Hachmeister, et al. (1995). “Repeated oral vitamin K prophylaxis in West Germany: acceptance and efficacy.

” BMJ310(6987): 1097-1098.

- van Hasselt, P. M., T. J. de Koning, et al. (2008). “Prevention of vitamin K deficiency bleeding in breastfed infants: lessons from the Dutch and Danish biliary atresia registries.” Pediatrics121(4): e857-863.

- von Kries, R., A. Hachmeister, et al. (1995). “Repeated oral vitamin K prophylaxis in West Germany: acceptance and efficacy.

Enjoy the video, and I hope you find it helpful! Stay tuned for our next Q & A!

Want to submit a question for consideration?

Submit your question for the Q & A

Transcript

Hi, everyone. In today’s video we’re going to take a look at the evidence for using oral vitamin K drops in newborns instead of the vitamin K shot.

Hi, everyone. I’m so excited to see you again. Thanks for taking the time to watch this video and thanks for all your comments on the other videos. I can’t tell you how excited everyone is to have the opportunity to learn more about vitamin K and eye ointment.

My name is Rebecca Dekker, and I’m a nurse with my PhD. I’m the founder of Evidence Based Birth®. I originally created these videos in 2014 to celebrate the release of my continuing education course all about vitamin K and eye ointment so everybody could get something out of the release of the course, even if you weren’t enrolled. I updated these videos in 2017.

I’m the founder of Evidence Based Birth®. I originally created these videos in 2014 to celebrate the release of my continuing education course all about vitamin K and eye ointment so everybody could get something out of the release of the course, even if you weren’t enrolled. I updated these videos in 2017.

Back in 2014 when I filmed these videos for the first time, I asked everyone what they wanted me to teach about this in this video lesson, and I got quite a few responses. It seemed like the most popular request by far was for me to teach about the use of oral vitamin K drops instead of the vitamin K shot. Let’s get started.

Now if you didn’t watch my first video lesson on vitamin K or you’ve never read my blog article before about vitamin K, you might want to do that first so you have a basic understanding of why vitamin K levels are important in newborns.

Just as a reminder, babies are born with limited amounts of vitamin K, and they don’t get very much through breast milk. If they don’t have enough vitamin K, they can start bleeding suddenly, any time in the first six months of life. This type of bleeding is rare, but when it does happen, it can be dangerous because the bleeding often happens in the brain.

If they don’t have enough vitamin K, they can start bleeding suddenly, any time in the first six months of life. This type of bleeding is rare, but when it does happen, it can be dangerous because the bleeding often happens in the brain.

Now when I released my blog article in 2014 about vitamin K, a lot of people asked me, if a parent decides to do the oral vitamin K instead of giving their baby the shot, what’s the best regimen to prevent bleeding? Let’s talk about the answer to that question.

Research on oral vitamin K drops originally started by looking at a three-dose regimen. This meant that the baby would get one milligram of oral vitamin K at birth, by mouth, once again again about a week later, and then once more between four and six months of age. Research is very clear that although this three-dose regimen does lower the risk of the baby bleeding from vitamin K deficiency, it’s not as good as the shot.

However, the question comes up, are there any other regimens that are helpful? What about weekly or daily administration of oral vitamin K? There is one really interesting study that compares the weekly and daily regimen. Based on that study, the most promising oral regimen seems to be giving a weekly dose of oral vitamin K for the first six months of life.

Based on that study, the most promising oral regimen seems to be giving a weekly dose of oral vitamin K for the first six months of life.

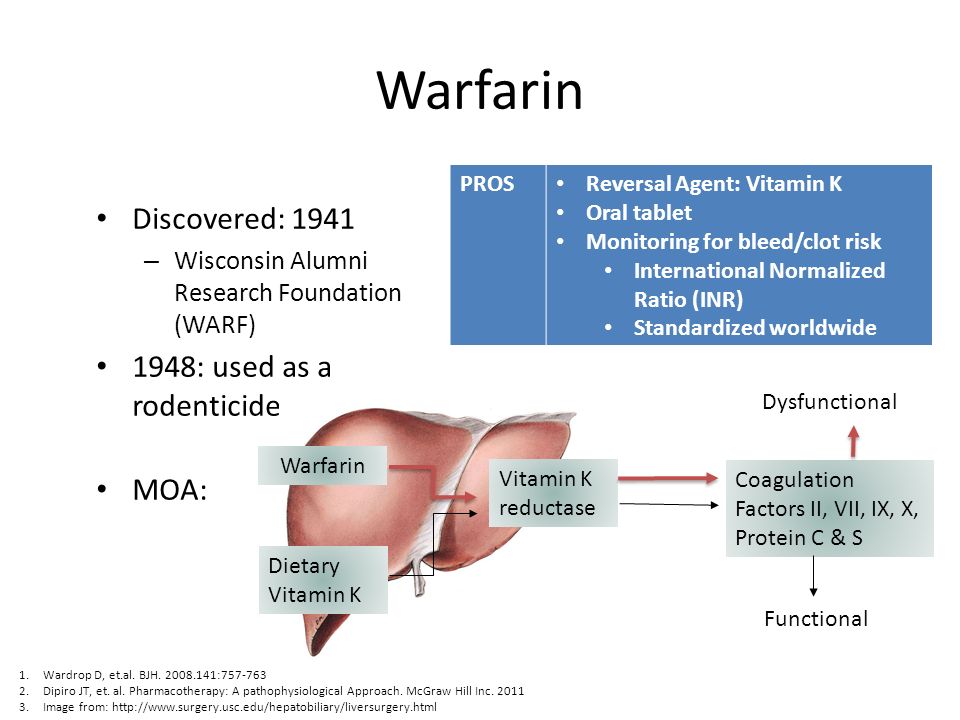

Here’s the deal. The main concern that doctors have with using oral vitamin K instead of the shot is that oral vitamin K probably won’t work for babies with undiagnosed gallbladder problems. Gallbladder problems in babies are rare. They happen in about one out of 60,000 infants, but they’re serious because they often start with bleeding in the brain. Babies with gallbladder problems have trouble absorbing fat-soluble vitamins like vitamin K in their stomach. That’s why they are at higher risk for vitamin K deficiency bleeding.

The good thing about giving vitamin K by mouth weekly instead of just three times during infancy is that the weekly dose seems to protect these babies with undiagnosed gallbladder disease. This regimen used to be used in Denmark. What they did is that all babies got two milligrams of oral vitamin K after birth and then one milligram orally weekly as long as the babies were getting at least half of their feedings through breast milk.

What they did in Denmark is they tracked all of the babies that had gallbladder problems during that time. During this about six-year period, there were 23 babies that had that rare gallbladder problem. Out of those 23 babies, only one of them had a case of vitamin K deficiency bleeding, but it was not in the brain. None of these babies had bleeding in the brain, which showed that the oral weekly dose did protect these babies with the gallbladder problems.

When they compared this regimen to the shot, it was just as effective as the shot. Another way of saying it would be to say that the shot was also very effective at preventing brain bleeds in babies with that rare, undiagnosed gallbladder problem.

Now one of the interesting things about this research is that in Denmark they actually stopped using the weekly vitamin K oral dose and now they only use the vitamin K shot. The main reason that they stopped using the oral vitamin K is because it’s no longer available on the market. You’ll find that, around the world, whether or not countries can offer the oral regimen depends on whether it’s available for purchase in their country.

You’ll find that, around the world, whether or not countries can offer the oral regimen depends on whether it’s available for purchase in their country.

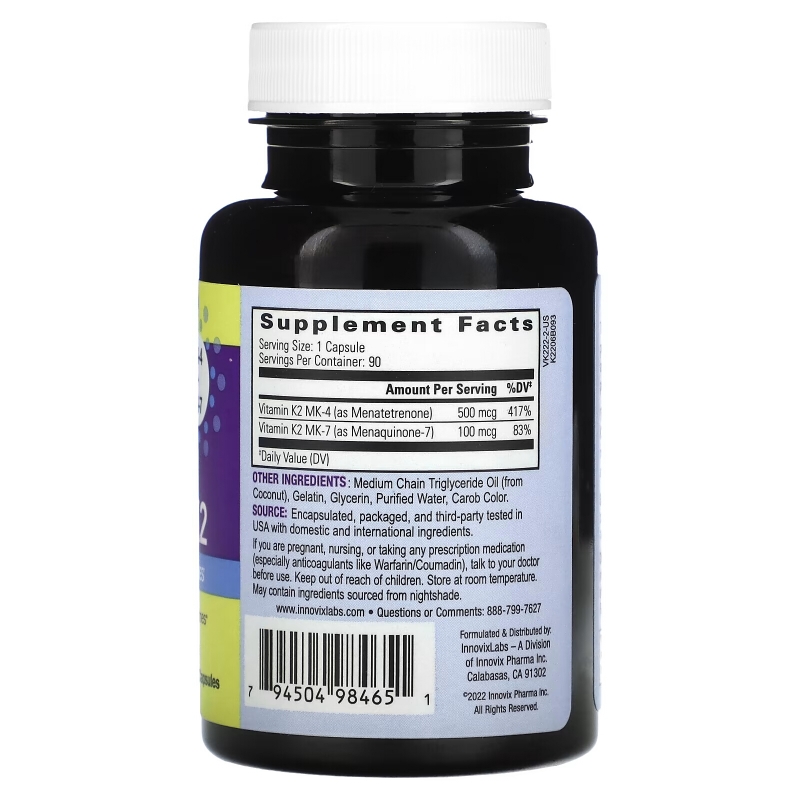

What if you’re a parent in the United States and you want to use this weekly oral regimen? One of the problems is that we don’t have a licensed or FDA-approved version of oral vitamin K for infants. This is called K-Quinone; it is a form of oral vitamin K that you used to be able to buy at food health stores, but I don’t think you can purchase it anymore. There’s at least one other option I’ve seen for sale online in the United States.

One of the problems with these oral vitamin K options is that they’re not regulated by any third party, so we don’t know if the dosing is accurate. The amount of vitamin K in each drop could vary widely from bottle to bottle because there’s no third party that’s testing it to ensure that the dose is accurate.

There’s also a five-milligram vitamin K prescription pill that people sometimes cut up into pieces and then crush and mix with water, and put into the baby’s cheek. But because that pill is five milligrams and you need a one or two-milligram dose, it can be an inaccurate way to get your baby the vitamin K orally.

But because that pill is five milligrams and you need a one or two-milligram dose, it can be an inaccurate way to get your baby the vitamin K orally.

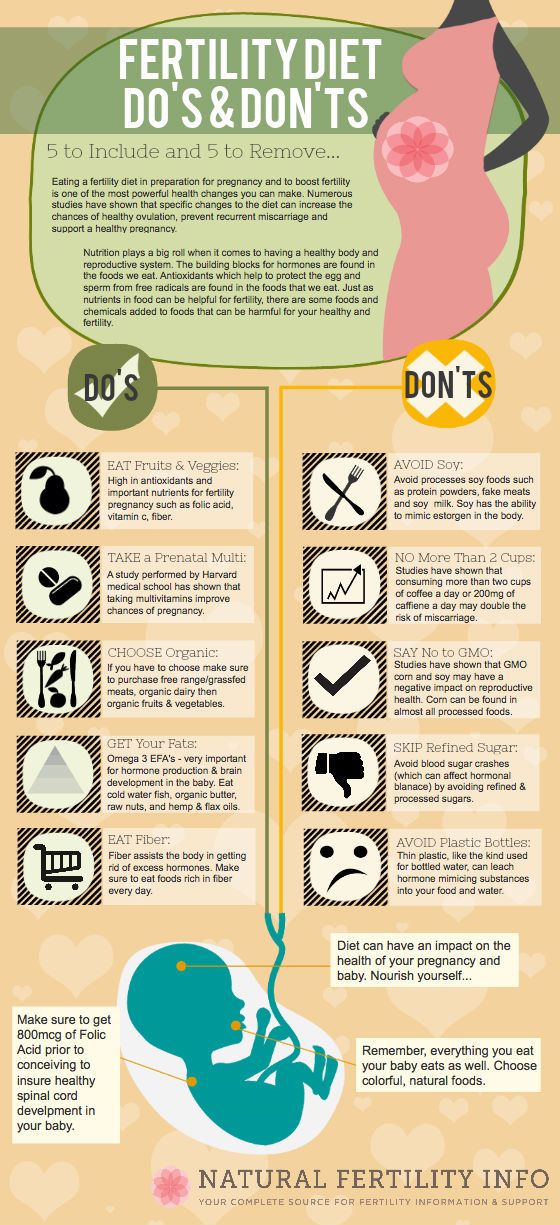

If parents choose the weekly dose of oral vitamin K, it’s important to remember that when this fat-soluble vitamin is given on an empty stomach, it might not be absorbed as well as vitamin K that’s mixed into formula. If parents are breastfeeding and giving their baby oral vitamin K, it’s important that they give it with a feeding and that they make sure that the baby doesn’t spit it up afterwards.

Before I close, I wanted to mention that one of the strange things about how our minds work is that different people can make completely different decisions based on the same information. One pretty could be given all of the research evidence on vitamin K, what it’s used for, what we know about it, what the different regimens are, how effective they are. Another parent could be given the exact same information, and these two parents could make completely different decisions.

If you want to learn more about this, I recommend a really awesome book called Your Medical Mind: How to Decide What’s Right For You by Dr. Jerome Groopman and Pamela Hartzband. Also, one of the problems about vitamin K is that despite my best attempts to put accurate information out there, there are still so many myths and so many rumors out there online about vitamin K. Just about every week somebody emails me a blog article or a new link that is just filled with bad information about vitamin K. It really makes my head hurt. I can’t even bare to read those articles anymore.

Just a tip: If anything uses really inflammatory language about vitamin K, talks about the dark side of vitamin K or the toxins of vitamin K, those people already made up their minds a long time ago about any kind of shot given to newborns, and they’re not really interested in reporting the facts about vitamin K.

If you’re a birth professional, I wanted to ask you, in the midst of all of this information and misinformation, how are you supposed to be able to help parents tell myths from facts? How would you feel if your words led someone down a path and they made a decision based on inaccurate information? Now imagine the opposite. Imagine you’re in a position where you can give accurate information the other people about controversial topics so that, no matter what decision they make, they’re making a truly informed decision and one that’s not based on your own biases or on rumors or misinformation.

Imagine you’re in a position where you can give accurate information the other people about controversial topics so that, no matter what decision they make, they’re making a truly informed decision and one that’s not based on your own biases or on rumors or misinformation.

I’ve seen this need. It really is a pain point. People don’t want to make decisions based on bad information or to give bad information to their clients. I have literally spent years collecting all of the research that I could find on both vitamin K and eye ointment, and putting them into one intensive online course all about these newborn procedures.

If you take this course, it will completely change how you talk with other people about vitamin K and eye ointment because it will open your eyes to the difference between the many myths out there and what the research evidence shows. The course is good for nursing contact hours and pharmacology CEUs for nurse midwives. I’ve also applied for credits for physicians as well.

If you’ve subscribe to this video series and you’re getting my email reminders about these video lessons, I just wanted to give you a heads up that in my next video I’m going to have an offer for you to enroll in this in-depth class. You’re going to want to open that email if you want to take your learning to the next level. If you’re not subscribed to the emails about this free video series, make sure you subscribe by clicking the link below so that you can find out how to join the class.

I hope you’ve found these videos helpful. My call to action for you today is to leave a comment about the information you’ve learned about oral vitamin K that we covered in this video. Finally, if you haven’t subscribed to the EBB newsletter, which is free, make sure you become a subscriber today, because there are a ton of free printable handouts that you’ll get instant access to and that you can print and share with anyone you like. Thanks for listening. Bye.

Low-dose oral vitamin K therapy for the management of asymptomatic patients with elevated international normalized ratios: a brief review

1. McMahan DA, Smith DM, Carey MA, Zhou XH. Risk of major hemorrhage for outpatient treatment with warfarin. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13(5):311-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

McMahan DA, Smith DM, Carey MA, Zhou XH. Risk of major hemorrhage for outpatient treatment with warfarin. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13(5):311-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

2. Samsa GP, Matchar DB, Goldstein LB, Bonito AJ, Lux LJ, Witter DM, et al. Quality of anticoagulation management among patients with atrial fibrillation: results of a review of medical records from 2 communities. Arch Intern Med 2000;160(7):967-73. [PubMed]

3. Kearon C, Gent M, Hirsh J, Weitz J, Kovacs MJ, Anderson DR, et al. A comparison of three months of anticoagulation with extended anticoagulation for a first episode of idiopathic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 1999;340(12):901-7. [PubMed]

4. Palareti G, Leali N, Coccheri S, Poggi M, Manotti C, D'Angelo A, et al. Bleeding complications of oral anticoagulant treatment: an inception-cohort, prospective collaborative study (ISCOAT). Lancet 1996;348(7372):423-8. [PubMed]

5. Oden A, Fahlen M. Oral anticoagulation and risk of death: a medical record linkage study. BMJ 2002;325(7372):1073-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

BMJ 2002;325(7372):1073-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

6. Hylek EM, Chang Y, Skates SJ, Hughes RA, Singer DE. Prospective study of the outcomes of ambulatory patients with excessive warfarin anticoagulation. Ann Intern Med 2000;160(11):1612-7. [PubMed]

7. Crowther MA, Ginsberg JS, Julian J, Denburg J, Hirsh J, Douketis J, et al. A comparison of two intensities of warfarin for the prevention of recurrent thrombosis in patients with the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003;349(12):1133-8. [PubMed]

8. Hirsh J, Dalen JE, Anderson DR, Pollex L, Bussey H, Ansell J, et al. Oral anticoagulants: mechanism of action, clinical effectiveness, and optimal therapeutic range [review]. Chest 2001;119(1 Suppl):8S-21S. [PubMed]

9. White RH, Minton SM, Andya MD, Hutchinson R. Temporary reversal of anticoagulation using oral vitamin K. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2000;10(2):149-53. [PubMed]

10. Pengo V, Banzato A, Garelli E, Zasso A, Biasiolo A. Reversal of excessive effect of regular anticoagulation: low oral dose of phytonadione (vitamin K1) compared with warfarin discontinuation. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 1993;4(5):739-41. [PubMed]

Reversal of excessive effect of regular anticoagulation: low oral dose of phytonadione (vitamin K1) compared with warfarin discontinuation. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 1993;4(5):739-41. [PubMed]

11. Wentzien TH, O'Reilly RA, Kearns PJ. Prospective evaluation of anticoagulant reversal with oral vitamin K1 while continuing warfarin therapy unchanged. Chest 1998;114(6):1546-50. [PubMed]

12. Penning-van Beest FJ, Rosendaal FR, Grobbee DE, van Meegen E, Stricker BH. Course of the International Normalized Ratio in response to oral vitamin K1 in patients overanticoagulated with phenprocoumon. Br J Haematol 1999;104(2):241-5. [PubMed]

13. Fondevila CG, Grosso SH, Santarelli MT, Pinto MD. Reversal of excessive oral anticoagulation with a low oral dose of vitamin K1 compared with acenocoumarin discontinuation. A prospective, randomized, open study. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2001;12(1):9-16. [PubMed]

14. Ortin M, Olalla J, Marco F, Velasco N. Low-dose vitamin K1 versus short-term withholding of acenocoumarol in the treatment of excessive anticoagulation episodes induced by acenocoumarol. A retrospective comparative study. Haemostasis 1998;28(2):57-61. [PubMed]

Low-dose vitamin K1 versus short-term withholding of acenocoumarol in the treatment of excessive anticoagulation episodes induced by acenocoumarol. A retrospective comparative study. Haemostasis 1998;28(2):57-61. [PubMed]

15. Cosgriff SW. The effectiveness of an oral vitamin K1 in controlling excessive hypoprothrombinemia during anticoagulant therapy. Ann Intern Med 1956;45 (1):14-22. [PubMed]

16. Poli D, Antonucci E, Lombardi A, Gensini GF, Abbate R, Prisco D, et al. Safety and effectiveness of low dose oral vitamin K1 administration in asymptomatic out-patients on warfarin or acenocoumarol with excessive anticoagulation. Haematologica 2003;88(2):237-8. [PubMed]

17. Harrell CC, Kline SS. Oral vitamin K1: an option to reduce warfarin's activity. Ann Pharmacother 1995;29(12):1228-32. [PubMed]

18. Cruickshank J, Ragg M, Eddey D. Warfarin toxicity in the emergency department: recommendations for management. Emerg Med (Fremantle) 2001;13(1):91-7. [PubMed]

[PubMed]

19. Weibert RT, Le DT, Kayser SR, Rapaport SI. Correction of excessive anticoagulation with low-dose oral vitamin K1. Ann Intern Med 1997;126(12):959-62. [PubMed]

20. Whitling AM, Bussey HI, Lyons RM. Comparing different routes and doses of phytonadione for reversing excessive anticoagulation. Arch Intern Med 1998;158(19):2136-40. [PubMed]

21. Taylor CT, Chester EA, Byrd DC, Stephens MA. Vitamin K to reverse excessive anticoagulation: a review of the literature. Pharmacotherapy 1999;19(12):1415-25. [PubMed]

22. Patel RJ, Witt DM, Saseen JJ, Tillman DJ, Wilkinson DS. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of oral phytonadione for excessive anticoagulation. Pharmacotherapy 2000;20(10):1159-66. [PubMed]

23. Crowther MA, Julian J, McCarty D, Douketis J, Kovacs M, Biagoni L, et al. Treatment of warfarin-associated coagulopathy with oral vitamin K: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2001;356(9241):1551-3. [PubMed]

24. Crowther MA, Douketis JD, Schnurr T, Steidl L, Mera V, Ultori C, et al. Oral vitamin K lowers the international normalized ratio more rapidly than subcutaneous vitamin K in the treatment of warfarin-associated coagulopathy. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2002;137(4):251-4. [PubMed]

Crowther MA, Douketis JD, Schnurr T, Steidl L, Mera V, Ultori C, et al. Oral vitamin K lowers the international normalized ratio more rapidly than subcutaneous vitamin K in the treatment of warfarin-associated coagulopathy. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2002;137(4):251-4. [PubMed]

25. Lubetsky A, Yonath H, Olchovsky D, Loebstein R, Halkin H, Ezra D. Comparison of oral versus intravenous phytonadione (Vitamin K1) in patients with excessive anticoagulation: a prospective randomized controlled study. Arch Intern Med 2003;163(20):2469-73. [PubMed]

26. Crowther MA, Donovan D, Harrison L, McGinnis J, Ginsberg J. Low-dose oral vitamin K reliably reverses over-anticoagulation due to warfarin. Thromb Haemost 1998;79(6):1116-8. [PubMed]

27. Duong TM, Plowman BK, Morreale AP, Janetzky K. Retrospective and prospective analyses of the treatment of overanticoagulated patients. Pharmacotherapy 1998;18(6):1264-70. [PubMed]

28. Pendry K, Bhavnani M, Shwe K. The use of oral vitamin K for reversal of over-warfarinization [letter]. Br J Haematol 2001;113(3):839-40. [PubMed]

Pendry K, Bhavnani M, Shwe K. The use of oral vitamin K for reversal of over-warfarinization [letter]. Br J Haematol 2001;113(3):839-40. [PubMed]

29. Watson HG, Baglin T, Laidlaw SL, Makris M, Preston E. A comparison of the efficacy and rate of response to oral and intravenous vitamin K in reversal of over-anticoagulation with warfarin. Br J Haematol 2001;115(1):145-9. [PubMed]

30. Lousberg TR, Witt DM, Beall DG, Carter BL, Malone DC. Evaluation of excessive anticoagulation in a group model health maintenance organization. Arch Intern Med 1998;158(5):528-34. [PubMed]

31. Glover JJ, Morrill GB. Conservative treatment of overanticoagulated patients. Chest 1995;108(4):987-90. [PubMed]

32. Wilson SE, Douketis JD, Crowther MA. Treatment of warfarin-associated coagulopathy: a physician survey. Chest 2001;120(6):1972-6. [PubMed]

33. Nee R, Doppenschmidt D, Donovan DJ, Andrews TC. Intravenous versus subcutaneous vitamin K1 in reversing excessive oral anticoagulation. Am J Cardiol 1999;83(2):286-8. [PubMed]

34. Raj G, Kumar R, McKinney WP. Time course of reversal of anticoagulant effect of warfarin by intravenous and subcutaneous phytonadione. Arch Intern Med 1999;159(22):2721-4. [PubMed]

35. Martinez-Abad M, Delgado F, Palop V, Morales-Olivas FJ. Vitamin K and anaphylactic shock. Ann Pharmacother 1991;25(7-8):871-2. [PubMed]

What you need to know about vitamin B12

WHY YOU NEED VITAMIN B12

Vitamin B12 (or cyanocobalamin) is needed for the formation of red blood cells, neuronal development and DNA synthesis. Its deficiency can lead to the accumulation of homocysteine (a neurotoxic compound), anemia, loss of balance, numbness of the limbs, fatigue and memory impairment.

Lack of vitamin B12 is most pronounced: at an older age, after surgery to reduce the stomach, with reduced stomach acid or medication to reduce it, when taking heartburn medications, with diseases of the gastrointestinal tract (Crohn's disease), with a vegan diet.

Vitamin B12 is stored in the liver. Normally, there is a reserve in the human body for several years, but then it can be exhausted. Therefore, people who switch to a vegan or raw food diet feel good at first, especially if they ate a lot of meat before. After a few years, most people go back to eating meat and do not have time to feel the symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency.

VITAMIN B12 RATES

The daily requirement for vitamin B12 depends on age. For adults, it is 2.4 mcg per day, for pregnant and breastfeeding women - a little more. Vitamin B12 has traditionally been prescribed by injection, but 1000 micrograms of the vitamin per day orally has now been shown to be effective, even in people with poor absorption and low acidity. If there are problems with the gastrointestinal tract, then vitamin B12 will be poorly absorbed from food. But taking in large doses will solve the problem. This vitamin can accumulate and is non-toxic, so it is advisable to drink or inject it not constantly, but in courses.

B vitamins interact, so sometimes it is important to drink not vitamin complexes, but those that are not enough. Such an interaction exists, for example, with vitamin B9. Its excess can mask the lack of vitamin B12. A person, for example, eats a lot of vegetables and does not eat meat. If a person does not use B12 for a long time (several years), and then he does an analysis for homocysteine, then the indicator is likely to be normal. This is because B9 and B12 are involved in the same metabolic pathway. But this does not mean that you can do without B12. Masking does not mean compensating.

Another reason to take vitamin B12 alone is that the cobalt ion in it destroys other vitamins. B12 interacts with some medications, so if you are taking any medications, especially for treating heartburn, ulcers, and diabetes, be sure to check with your doctor.

WHEN THERE IS A DEFICIENCY OF VITAMIN B12

A lack of vitamin B12 can be suspected by the results of an analysis of homocysteine - this substance becomes more with a lack of vitamin B12. But this analysis is not completely reliable. If you consume a large amount of folic acid, for example, thanks to a vegan diet, the level of homocysteine will be normal.

But this analysis is not completely reliable. If you consume a large amount of folic acid, for example, thanks to a vegan diet, the level of homocysteine will be normal.

Another marker of B12 deficiency is megaloblastic anemia. It is diagnosed with a blood test. Anemia caused by a lack of B12 passes safely, but neurodegenerative processes due to a lack of cyanocobalamin are irreversible. A number of studies have shown that people with various forms of dementia often lack vitamins B12 and B9, but the therapeutic effect of these vitamins on patients with dementia is rather weak.

Fervent fans of a purely plant-based diet cite herbivorous primates as an example, since they eat only fruits and are not deficient in B12. But primates in the wild eat termites and other insects, and along with them - a sufficient amount of B12.

WHERE IS VITAMIN B12

Vitamin B12 is found in animal products, primarily in red meat, liver and fish, but also in eggs and milk. It can be added to food products at the factory, which must be indicated on the label.

It can be added to food products at the factory, which must be indicated on the label.

WHO SHOULD USE B12:

- vegans and vegetarians with experience;

- people with low stomach acid;

- people with chronic bowel disease (Crohn's disease, irritable bowel syndrome) or after surgery on the gastrointestinal tract;

- people over the age of 50;

- AIDS patients;

- people who take antacids, metformin to treat diabetes.

In some cases, B vitamins can be poorly absorbed or even harmful, so rule number 1 is to consult your doctor before taking any vitamins or medications.

Source

Unresolved issues of vitamin and mineral support for patients undergoing bariatric surgery | Malykhina

INTRODUCTION

Throughout the world, the prevalence of obesity has been steadily increasing over the past few decades. This disease, which can rightfully be considered a non-infectious epidemic of the 21st century, is considered not only as a cosmetic problem, since it reduces the duration and quality of life. The high prevalence of obesity is a serious medical and social problem and is due to urbanization, a decrease in the physical activity of the population and the availability of high-calorie food.

The high prevalence of obesity is a serious medical and social problem and is due to urbanization, a decrease in the physical activity of the population and the availability of high-calorie food.

According to the WHO fact sheet of October 2017, in 2016, more than 1.9 billion people over the age of 18 were overweight in the world, of which over 650 million were obese [1].

According to the ESSE-RF (Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Diseases and Their Risk Factors in the Regions of the Russian Federation) multicenter observational Russian study conducted in 11 regions of the Russian Federation, in which 18,305 people took part (including 6,919 men and 11,386 women ,) at the age of 25–64 years, the prevalence of obesity in the population was 29.7% [2].

Obesity is not only a problem of the adult population. Worldwide, about 41 million children under the age of 5 are overweight or obese [1].

Chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases (CVD), dyslipidemia, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSA), musculoskeletal diseases and many cancers [3] have been shown to be associated with obesity, and even after minimal weight loss at the level of 5-10% of the original, the outcomes of these diseases significantly improve [4-9].

Unfortunately, to date, all existing conservative methods of treating obesity (diet, pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, etc.) ultimately turn out to be ineffective, and maintaining the achieved result in terms of weight loss is the most difficult task for patients.

Bariatric surgery is currently recognized as the most effective and radical method of treating morbid obesity [10–15].

Bariatric surgery can lead to impressive results in terms of weight loss and improvement in patient health, but the development of vitamin and micronutrient deficiencies is a common and inevitable problem in the postoperative period.

Various forms of nutritional deficiencies can develop after any type of bariatric surgery, and the more difficult the operation and the greater the percentage of excess weight loss, the more pronounced the degree of expected nutritional deficiency.

Many obese patients already initially have a deficiency of vitamins and microelements, in particular, a deficiency of vitamins D, B 1 , B 12 , iron, etc. [7, 16–29], therefore, it is necessary to identify and correct in a timely manner these deficient states are still at the preoperative stage.

[7, 16–29], therefore, it is necessary to identify and correct in a timely manner these deficient states are still at the preoperative stage.

Due to the high popularity of bariatric surgeries all over the world, the growing interest in them in Russia every year, the question of active dynamic postoperative monitoring and management of these patients in the long term after surgery is steadily rising.

VITAMIN AND MINERAL SUPPORT AFTER DIFFERENT TYPES OF BARIATRIC SURGERY

Depending on the type of bariatric surgery used (restrictive, malabsorptive), the daily requirement for vitamins, macro- and microelements varies, but always exceeds the daily requirement for non-operated patients.

To prevent the development of micronutrient deficiencies, all patients who have undergone bariatric surgery are recommended to take multivitamin complexes that include vitamins, macro- (calcium, phosphorus, etc.) and microelements: iron, zinc, selenium and copper [6, 15 , 30–33].

Due to the lack of specially developed “bariatric vitamin-mineral complexes” on the Russian pharmaceutical market, the curator has to prescribe affordable multivitamins in the pharmacy network that do not meet the requirements of International recommendations and do not contain enough copper, selenium, magnesium, manganese and other trace elements; in this connection, additional administration of iron preparations and fat-soluble vitamins, as well as calcium and vitamin D preparations is required.

IRON PRODUCTS

To prevent the development of iron deficiency anemia (IDA) in patients after gastrectomy (LGA), gastric bypass (GAS) and biliopancreatic bypass (BPS) [23, 34], 45–60 mg of elemental iron per day should be prescribed [ 31-33], women of childbearing age are advised to increase the dose of elemental iron to 100 mg per day [33, 35, 36].

Ferrous salts are preferred due to their greater bioavailability, and co-administration of iron with vitamin C increases iron absorption [34, 37]. During pregnancy, ferrous sulfate 200 mg 2-3 times a day is prescribed [32]. To date, there are preparations containing non-ionized iron, which are multimolecular complexes of ferric hydroxide. Questions about the purpose, efficacy and tolerability of these drugs in operated patients require further study. A separate study requires a preparation containing sucrosomal (liposomal) iron. However, one capsule of this drug contains 30 mg of liposomal iron, which requires the appointment of at least 2 capsules per day, which is off-label (appointment not recommended in the instructions for use of the drug). Questions about the purpose, efficacy and tolerability of these drugs in operated bariatric patients are also not well understood.

During pregnancy, ferrous sulfate 200 mg 2-3 times a day is prescribed [32]. To date, there are preparations containing non-ionized iron, which are multimolecular complexes of ferric hydroxide. Questions about the purpose, efficacy and tolerability of these drugs in operated patients require further study. A separate study requires a preparation containing sucrosomal (liposomal) iron. However, one capsule of this drug contains 30 mg of liposomal iron, which requires the appointment of at least 2 capsules per day, which is off-label (appointment not recommended in the instructions for use of the drug). Questions about the purpose, efficacy and tolerability of these drugs in operated bariatric patients are also not well understood.

Ferrous sulfate preparations are usually prescribed to patients after bariatric surgery due to good bioavailability, efficacy and low cost [6, 37-39]. In a systematic review, Manasanch et al. [40] showed that modified-release ferrous sulfate preparations were better tolerated and had fewer gastrointestinal side effects (nausea, dyspepsia, constipation).

Iron preparations are available in various dosage forms (pellets, capsules, chewable tablets, oral syrups) and differ in the amount of elemental iron per dosage unit, the chemical structure of iron, and galenic form (rapid or gradual release of the active ingredient) [ 41]. On the packaging of the drug, the content of the iron salt and the amount of equivalent elemental iron are usually indicated. When choosing a drug, you should focus on the amount of elemental iron. The composition of vitamin-mineral complexes registered in the Russian Federation includes 10-20 mg of elemental iron, which is insufficient for bariatric patients and requires additional prescription of iron preparations.

CALCIUM AND VITAMIN D

The daily dose of elemental calcium depends on the type of operation: after longitudinal gastric resection (LGA) and gastric bypass (GSH) - 1200-1500 mg; after biliopancreatic shunting (BPS), where the malabsorptive component is more pronounced - 1800–2400 mg [31, 32].

Calcium preparations are represented by organic calcium salts: citrate, gluconate, lactate, etc., and inorganic calcium salts: chloride, carbonate, phosphate [42, 43]. In patients undergoing bariatric surgery, it is preferable to prescribe calcium citrate preparations due to the fact that the bioavailability of calcium citrate is 2 times greater than the bioavailability of calcium carbonate [44]. The appointment of calcium citrate preparations is accompanied by a minimal risk of kidney stones due to its better solubility in water, and absorption does not depend on gastric pH and meal times. Therefore, calcium citrate preparations are the drugs of choice in patients with achlorhydria, inflammatory bowel disease, and in patients taking proton pump inhibitors and H 2 blockers [42, 43, 45]. Taking calcium citrate preparations is not accompanied by dyspepsia, since this salt does not neutralize hydrochloric acid and does not form carbon dioxide [43].

Meta-analysis by Sakhaee K. 1999 showed that calcium absorption from calcium citrate is 22–27% higher than from calcium carbonate, both on an empty stomach and when fed together, and thus a calcium citrate preparation can be taken both before, during and after meals [46].

1999 showed that calcium absorption from calcium citrate is 22–27% higher than from calcium carbonate, both on an empty stomach and when fed together, and thus a calcium citrate preparation can be taken both before, during and after meals [46].

To date, dietary supplements are registered in Russia, which include calcium citrate and vitamin D 3 . However, its calcium citrate content is only 250 mg per tablet, and to achieve the recommended daily requirement for elemental calcium, 6 to 8 tablets per day must be taken, which creates some inconvenience for patients and is not economically viable. The Russian pharmaceutical market also presents a combination drug that includes citrate and calcium carbonate salts, as well as vitamin D and other trace elements; however, the manufacturer does not indicate the percentage of calcium salts in the preparation.

According to the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) [31] and the Obesity Task Force Practice Guidelines [32], the recommended preventive dose of vitamin D in patients undergoing weight loss surgery should be based on baseline levels of vitamin D in blood serum and can reach 50,000 IU/day, and the recommended maintenance dose of vitamin D at an initial level of 25(OH)D> 30 ng/ml is 3000 IU.

FAT-SOLUBLE VITAMINS PRODUCTS

All patients, according to international recommendations [31, 32], should take fat-soluble vitamins (A, E, K), the dose of which depends on the type of bariatric surgery: after PRV and GS - vitamin A - 5000 IU ( is part of the vitamin-mineral complexes), vitamin K - 90-120 mcg.

Given the more pronounced hypoabsorption of fats and the possible development of steatorrhea after BPD, large doses of fat-soluble vitamins are required: vitamin A - 10,000 IU, vitamin K - 300 mcg.

The dosage of vitamin E after various types of bariatric surgery is debatable. Although the optimal dose for the prevention and/or treatment of vitamin E deficiency after HSS and BPD is not known, the recommended dose range is from 300–600 mg [47] to 800–1200 mg [48].

FOLIC ACID AND VITAMIN B SUPPLEMENTS

12 Supplementation of folic acid supplements is usually not required (unless there is an initial deficiency), since usually 400-600 micrograms of folic acid are included in vitamin-mineral complexes. Women of childbearing age are recommended to prescribe 800-1000 micrograms of folic acid per day [30, 31].

Women of childbearing age are recommended to prescribe 800-1000 micrograms of folic acid per day [30, 31].

All patients after bariatric surgeries (PVR, GS, BPS) should be prescribed vitamin B 12 [31, 32]. Absorption of vitamin B 12 is carried out with the participation of the internal factor of Castle (Intrinsic factor, IF), which is produced by the parietal cells of the gastric mucosa. However, approximately 1% of orally administered vitamin B 12, is passively absorbed, even in the absence of intrinsic Castle factor [23]. Therefore, oral intake of vitamin B 12 at a dose of 350–500 µg guarantees the absorption of the required dose of this vitamin [23, 31]. Currently, the oral form of vitamin B 12 is not registered in Russia. There are alternative regimens for prescribing vitamin B 12 [34]: 1000 µg IM once a month, 3000 µg IM once every 6 months, or 500 µg intranasally every week (this form of vitamin B 12 is not available in Russia). registered).

registered).

OTHER MEDICINES

Other mineral deficiencies (zinc, copper, selenium, potassium, magnesium) and vitamin B 9 deficiency0107 6 are described after bariatric surgeries [7, 23, 31, 34], therefore, these components should be included in vitamin-mineral complexes. If the above deficiencies are identified, it is necessary to carry out an appropriate correction in accordance with approved clinical guidelines.

CONCLUSION

Despite the fact that all obese patients who have undergone bariatric surgery need vitamin and mineral support, today, on the pharmaceutical market in Russia, there are no vitamin and mineral complexes that would fully satisfy the daily needs of these patients. patients in vitamins and microelements, which creates difficulties in the prevention of long-term postoperative complications.

Under these conditions, doctors have to combine the prescription of available multivitamins in the pharmacy network, iron, calcium and vitamin D preparations, fat-soluble vitamins in order to achieve optimal daily doses for patients after various bariatric surgeries.

This creates inconvenience, because in order to achieve optimal dosages of vitamins, macro- and microelements, patients have to simultaneously take a large number of drugs (up to 10 tablets or capsules per day), which leads to a violation of adherence to treatment (compliance), partial or complete skipping medications and increasing the cost of their purchase, as well as the inevitable increase in postoperative complications, which are caused by metabolic disorders.

The development and appearance on the Russian pharmaceutical market of vitamin and mineral supplements, balanced in all necessary components and meeting the recommended daily needs of patients after bariatric surgery, would reduce the frequency of long-term metabolic disorders by increasing compliance, ease of taking the dosage form of the drug and reducing the cost of purchase of the drug.

Thus, pharmaceutical companies are faced with the task of developing domestic vitamin and mineral complexes that would meet the needs of patients after bariatric surgery and at the same time combine ease of use and economic availability. Currently, Russian specialists have come close to the manufacture and clinical testing of such specialized vitamin and mineral preparations, and in the near future they will be ready to present them to a wide audience, both doctors and patients.

Currently, Russian specialists have come close to the manufacture and clinical testing of such specialized vitamin and mineral preparations, and in the near future they will be ready to present them to a wide audience, both doctors and patients.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Funding source. Preparation and publication of the manuscript were carried out at the personal expense of the team of authors.

Conflict of interest. The authors declare no apparent or potential conflicts of interest related to the publication of this article.

Participation of authors. All authors made a significant contribution to the study and preparation of the article, read and approved the final version of the article before publication.

1. who.int [Internet]. world health organization. media center. Fact sheet "obesity and overweight". [updated 2018 Feb 16; cited 2019 Dec 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/ru/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

2. Muromtseva G.A., Kontsevaya A.V., Konstantinov V.V. ., etc. Prevalence of risk factors for noncommunicable diseases in the Russian population in 2012–2013. Results of the ESSE-RF study. // Cardiovascular therapy and prevention. - 2014. - T. 13. - No. 6. — S. 4-11. [Muromtseva GA, Kontsevaya AV, Konstantinov VV, et al. The prevalence of non-infectious diseases risk factors in the Russian population in 2012-2013 years. The results of ECVD-RF. Cardiovascular Therapy and Prevention. 2014;13(6):4-11. (In Russ).] DOI:10.15829/1728-8800-2014-6-4-11

Muromtseva G.A., Kontsevaya A.V., Konstantinov V.V. ., etc. Prevalence of risk factors for noncommunicable diseases in the Russian population in 2012–2013. Results of the ESSE-RF study. // Cardiovascular therapy and prevention. - 2014. - T. 13. - No. 6. — S. 4-11. [Muromtseva GA, Kontsevaya AV, Konstantinov VV, et al. The prevalence of non-infectious diseases risk factors in the Russian population in 2012-2013 years. The results of ECVD-RF. Cardiovascular Therapy and Prevention. 2014;13(6):4-11. (In Russ).] DOI:10.15829/1728-8800-2014-6-4-11

3. Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(17):1625-1638. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa021423

4. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report. 1998.

1998.

5. Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, et al. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:88. DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-9-88

6. Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient--2013 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21 Suppl 1:S1-27. DOI:10.1002/oby.20461

7. Bodunova N.A. Influence of bariatric operations on the content of vitamins in obese patients: Abstract of the thesis. dis. … cand. honey. Sciences. — M.; 2016. [Bodunova NA. Vliyanie bariatricheskikh operatsiy na soderzhanie vitaminov u bol’nykh s ozhireniem. [dissertation] Moscow; 2016. (In Russ).]

8. Maggard MA, Shugarman LR, Suttorp M, et al. Meta-analysis: surgical treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(7):547-559. DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00013

Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(7):547-559. DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00013

9. Mattar SG, Velcu LM, Rabinovitz M, et al. Surgically-induced weight loss significantly improves nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and the metabolic syndrome. Ann Surg. 2005;242(4):610-617; discussion 618-620. DOI:10.1097/01.sla.0000179652.07502.3f

10. Karlsson J, Taft C, Ryden A, et al. Ten-year trends in health-related quality of life after surgical and conventional treatment for severe obesity: the SOS intervention study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31(8):1248-1261. DOI:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803573

11. Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(26):2683-2693. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa035622

12. Sjostrom L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273(3):219-234. DOI:10.1111/joim.12012

DOI:10.1111/joim.12012

13. Yumuk V, Tsigos C, Fried M, et al. European Guidelines for Obesity Management in Adults. obes facts. 2015;8(6):402-424. DOI:10.1159/000442721

14. Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. Bariatric Surgery Worldwide 2013. Obes Surg. 2015;25(10):1822-1832. DOI:10.1007/s11695-015-1657-z

15. Russian Society of Surgeons, Society of Bariatric Surgeons. Clinical guidelines for bariatric and metabolic therapy. — M.; 2014. [Rossiyskoe obshchestvo khirurgov, obshchestvo bariatricheskikh khirurgov. Klinicheskie rekomendatsii po bariatricheskoy i metabolicheskoy terapii. Moscow; 2014. (In Russ).]

16. Kimmons JE, Blanck HM, Tohill BC, et al. Associations between body mass index and the prevalence of low micronutrient levels among US adults. MedGenMed. 2006;8(4):59.

17. Wortsman J, Matsuoka LY, Chen TC, et al. Decreased bioavailability of vitamin D in obesity. Am J Clinic Nutr. 2000;72(3):690-693. DOI:10.1093/ajcn/72.3.690

18. Cepeda-Lopez AC, Aeberli I, Zimmermann MB. Does obesity increase the risk for iron deficiency? A review of the literature and the potential mechanisms. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2010;80(4-5):263-270. DOI:10.1024/0300-9831/a000033

Cepeda-Lopez AC, Aeberli I, Zimmermann MB. Does obesity increase the risk for iron deficiency? A review of the literature and the potential mechanisms. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2010;80(4-5):263-270. DOI:10.1024/0300-9831/a000033

19. Marreiro DN, Fisberg M, Cozzolino SM. Zinc nutritional status and its relationships with hyperinsulinemia in obese children and adolescents. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2004;100(2):137-149. DOI:10.1385/bter:100:2:137

20. Toh SY, Zarshenas N, Jorgensen J. Prevalence of nutrient deficiencies in bariatric patients. nutrition. 2009;25(11-12):1150-1156. DOI:10.1016/j.nut.2009.03.012

21. Bavaresco M, Paganini S, Lima TP, et al. Nutritional course of patients submitted to bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2010;20(6):716-721. DOI:10.1007/s11695-008-9721-6

22. Flankbaum L, Belsley S, Drake V, et al. Pre-operative nutritional status of patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10(7):1033-1037. DOI:10. 1016/j.gassur.2006.03.004

1016/j.gassur.2006.03.004

23. Allied Health Sciences Section Ad Hoc Nutrition C, Aills L, Blankenship J, et al. ASMBS Allied Health Nutritional Guidelines for the Surgical Weight Loss Patient. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(5 Suppl):S73-108. DOI:10.1016/j.soard.2008.03.002

24. Xanthakos SA. Nutritional deficiencies in obesity and after bariatric surgery. Pediatric Clin North Am. 2009;56(5):1105-1121. DOI:10.1016/j.pcl.2009.07.002

25. Aasheim ET, Hofso D, Hjelmesaeth J, et al. Vitamin status in morbidly obese patients: a cross-sectional study. Am J Clinic Nutr. 2008;87(2):362-369. DOI:10.1093/ajcn/87.2.362

26. Ernst B, Thurnheer M, Schmid SM, Schultes B. Evidence for the necessity to systematically assess micronutrient status prior to bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2009;19(1):66-73. DOI:10.1007/s11695-008-9545-4

27. de Luis DA, Pacheco D, Izaola O, et al. Micronutrient status in morbidly obese women before bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(2):323-327. DOI:10.1016/j.soard.2011.09.015

DOI:10.1016/j.soard.2011.09.015

28. Lefebvre P, Letois F, Sultan A, et al. Nutrient deficiencies in patients with obesity considering bariatric surgery: a cross-sectional study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(3):540-546. DOI:10.1016/j.soard.2013.10.003

29. Bodunova N.A., Askerkhanov R.G., Khatkov I.E., et al. Effect of bariatric surgeries on vitamin metabolism in obese patients. // Therapeutic archive. - 2015. - T. 87. - No. 2. - C. 70-76. [Bodunova NA, Askerkhanov RG, Khat'kov IE, et al. Impact of bariatric surgery on vitamin metabolisms in obese patients. Ter Arkh. 2015;87(2):70-76. (In Russ).] DOI:10.17116/terarkh301587270-76

30. Dedov I.I., Melnichenko G.A., Shestakova M.V., et al. National clinical guidelines for the treatment of morbid obesity in adults. 3rd revision (treatment of morbid obesity in adults). // Obesity and metabolism. - 2018. - T. 15. - No. 1. - S. 53-70. [Dedov II, Mel'nichenko GA, Shestakova MV, et al. Russian national clinical recommendations for morbid obesity treatment in adults. 3rd revision (Morbid obesity treatment in adults). obesity and metabolism. 2018;15(1):53-70. (In Russ).] DOI:10.14341/OMET2018153-70

3rd revision (Morbid obesity treatment in adults). obesity and metabolism. 2018;15(1):53-70. (In Russ).] DOI:10.14341/OMET2018153-70

31. Parrott J, Frank L, Rabena R, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Integrated Health Nutritional Guidelines for the Surgical Weight Loss Patient 2016 Update: Micronutrients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(5):727-741. DOI:10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.018

32. Busetto L, Dicker D, Azran C, et al. Practical Recommendations of the Obesity Management Task Force of the European Association for the Study of Obesity for the Post-Bariatric Surgery Medical Management. obes facts. 2017;10(6):597-632. DOI:10.1159/000481825

33. O’Kane M, Pinkney J, Aasheim ET, et al. BOMSS Guidelines on peri-operative and postoperative biochemical monitoring and micronutrient replacement for patients undergoing bariatric surgery. BOMSS; 2014.

34. Mechanick JI, Kushner RF, Sugerman HJ, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery: Medical guidelines for clinical practice for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and non surgical support of the bariatric surgery patient. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(5 Suppl):S109-184. DOI:10.1016/j.soard.2008.08.009

Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(5 Suppl):S109-184. DOI:10.1016/j.soard.2008.08.009

35. Parkes E. Nutritional Management of Patients after Bariatric Surgery. Am J Med Sci. 2006;331(4):207-213. DOI:10.1097/00000441-200604000-00007

36. Malinowski SS. Nutritional and Metabolic Complications of Bariatric Surgery. Am J Med Sci. 2006;331(4):219-225. DOI:10.1097/00000441-200604000-00009

37. Love AL, Billett HH. Obesity, bariatric surgery, and iron deficiency: True, true, true and related. Am J Hematol. 2008;83(5):403-409. DOI:10.1002/ajh.21106

38. Wax JR, Pinette MG, Cartin A, Blackstone J. Female reproductive issues following bariatric surgery. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62(9):595-604. DOI:10.1097/01.ogx.0000279291.86611.46

39. Marinella MA. Anemia following Roux-en-Y surgery for morbid obesity: a review. South Med J. 2008;101(10):1024-1031. DOI:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31817cf7b7

40. Cancelo-Hidalgo MJ, Castelo-Branco C, Palacios S, et al. Tolerability of different oral iron supplements: a systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29(4):291-303. DOI:10.1185/03007995.2012.761599

Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29(4):291-303. DOI:10.1185/03007995.2012.761599

41. Belovol A.N., Knyazkova I.I. From iron metabolism to issues of pharmacological correction of its deficiency. // Faces of Ukraine. - 2015. - No. 4. — S. 46-51. [Bilovol AN, Knyaz'kova II. From Iron Metabolism to the Issues of Pharmacological Correction of Iron Deficiency. Likey Ukraine'ny. 2015;(4):46-51. (In Russ).]

42. Trailokya A, Srivastava A, Bhole M, Zalte N. Calcium and Calcium Salts. J Assoc Physicians India. 2017;65(2):100-103.

43. Gromova OA, Torshin I.Yu., Gogoleva IV, et al. Organic calcium salts: prospects for use in clinical practice. // RMJ. - 2012. - T. 20. - No. 28. - S. 1407-1411. [Gromova OA, Torshin IY, Gogoleva IV, et al. Organicheskie soli kal'tsiya: perspektivy ispol'zovaniya v klinicheskoy praktike. RMZh. 2012;20(28):1407-1411. (In Russ).]

44. Tondapu P, Provost D, Adams-Huet B, et al. Comparison of the absorption of calcium carbonate and calcium citrate after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2009;19(9):1256-1261. DOI:10.1007/s11695-009-9850-6

Obes Surg. 2009;19(9):1256-1261. DOI:10.1007/s11695-009-9850-6

45. Dobrokhotova Yu.E., Dugieva M.Z. Postmenopausal osteoporosis: calcium preparations in a modern strategy for prevention and treatment. // RMJ. Mother and child. - 2017. - T. 25. - No. 15. - S. 1135-1139. [Dobrohotova YE, Dugieva MZ. Postmenopauzal'nyy osteoporosis: preparaty kal'tsiya v sovremennoy strategii profilaktiki i lecheniya. RMZh. Mat' i childa. 2017;25(15):1135-1139. (In Russ).]

46. Sakhaee K, Bhuket T, Adams-Huet B, Rao DS. Meta-analysis of calcium bioavailability: a comparison of calcium citrate with calcium carbonate. Am J Ther. 1999;6(6):313-321. DOI:10.1097/00045391-199911000-00005

47. Allied Health Sciences Section Ad Hoc Nutrition C, Aills L, Blankenship J, et al. ASMBS Allied Health Nutritional Guidelines for the Surgical Weight Loss Patient. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(5 Suppl):S73-108. DOI:10.1016/j.soard.2008.03.002

48. Koch TR, Finelli FC. Postoperative metabolic and nutritional complications of bariatric surgery.