What can cause fetal distress

Fetal distress | Pregnancy Birth and Baby

beginning of content4-minute read

Listen

Fetal distress is a sign your baby isn’t coping with labour. It might mean they need closer monitoring and possibly a caesarean to speed up the birth.

What is fetal distress?

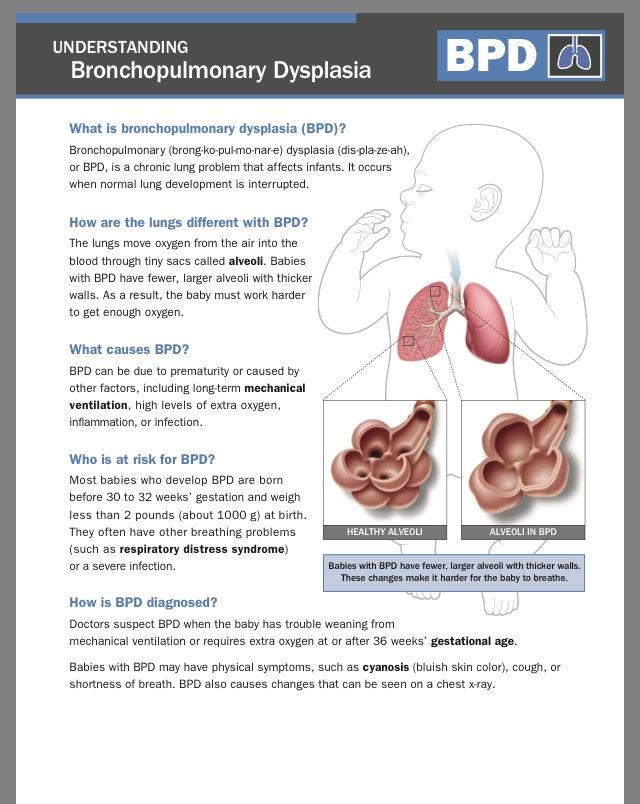

Fetal distress is a sign that your baby is not well. It happens when the baby isn’t receiving enough oxygen through the placenta.

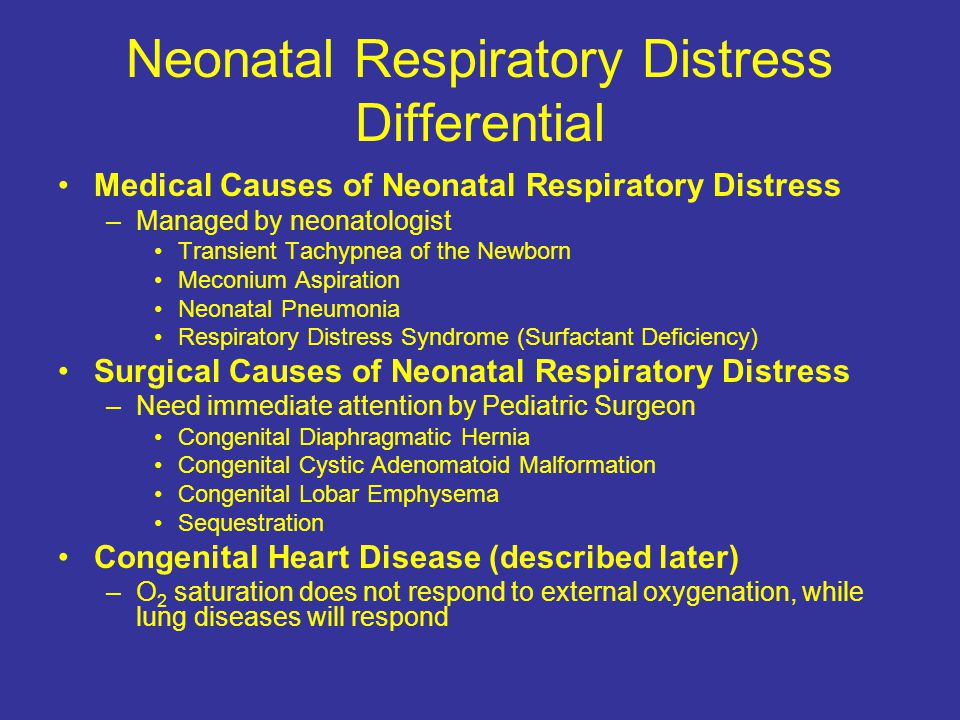

If it’s not treated, fetal distress can lead to the baby breathing in amniotic fluid containing meconium (poo). This can make it difficult for them to breathe after birth, or they may even stop breathing.

Fetal distress can sometimes happen during pregnancy, but it’s more common during labour.

What causes fetal distress?

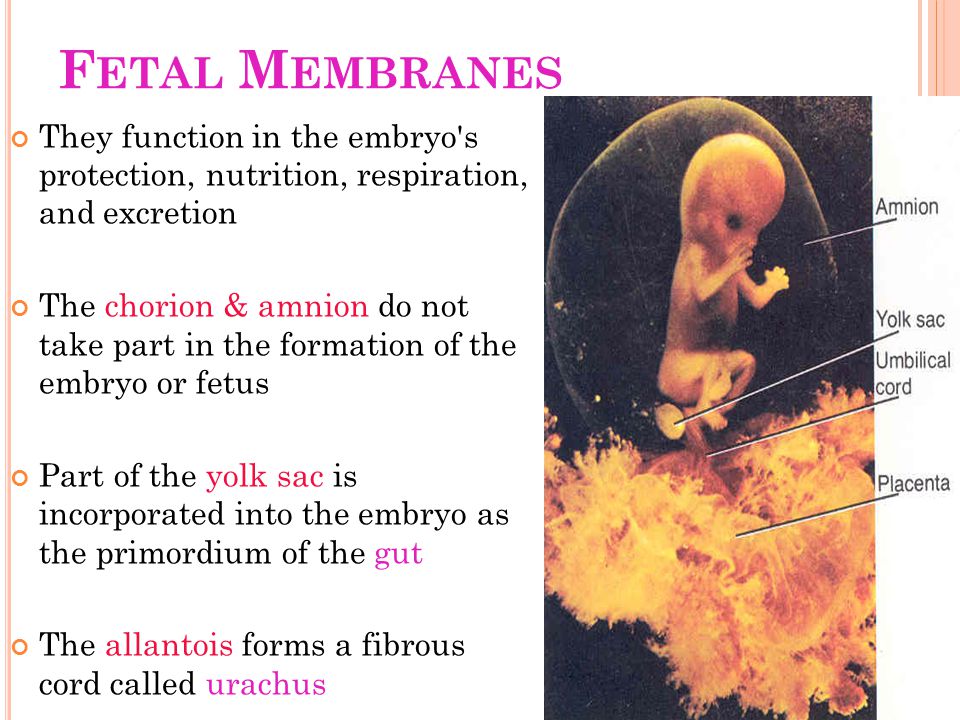

The most common cause of fetal distress is when the baby doesn’t receive enough oxygen because of problems with the placenta (including placental abruption or placental insufficiency) or problems with the umbilical cord (for example, if the cord gets compressed because it comes out of the cervix first).

Fetal distress can also occur because the mother has a health condition such as diabetes, kidney disease or cholestasis (a condition that affects the liver in pregnancy).

It is more common when pregnancy lasts too long, or when there are other complications during labour. Sometimes it happens because the contractions are too strong or too close together.

You are more at risk of your baby experiencing fetal distress if:

- you are obese

- you smoke

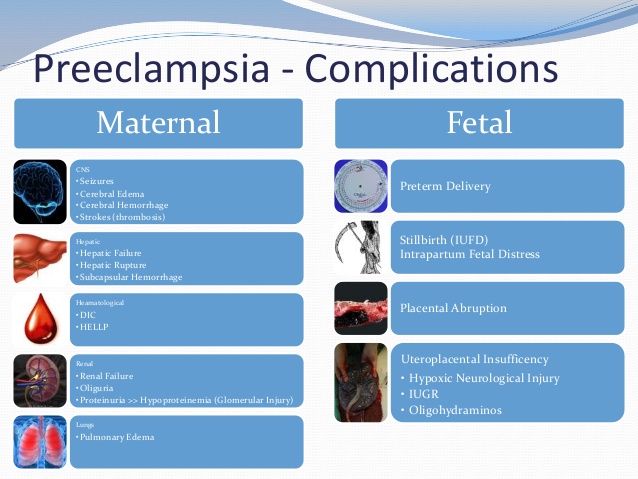

- you have high blood pressure in pregnancy or pre-eclampsia

- you have a chronic disease, such as diabetes or kidney disease

- you have a multiple pregnancy

- your baby has intrauterine growth restriction

- you have had a stillbirth before

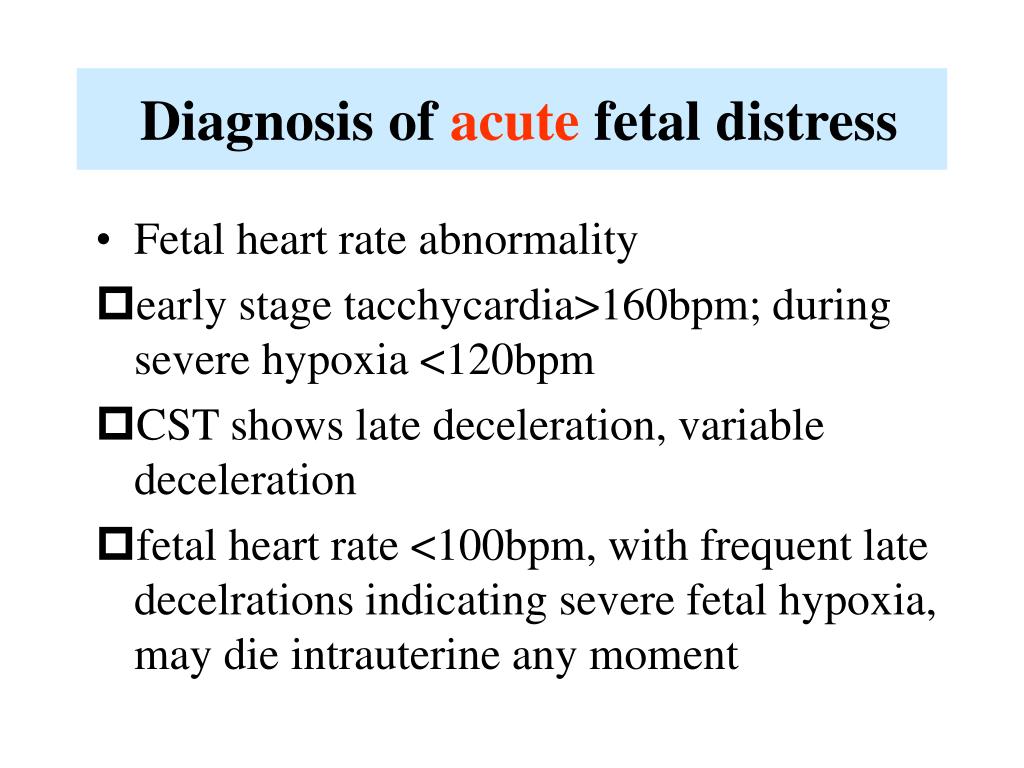

How is fetal distress diagnosed?

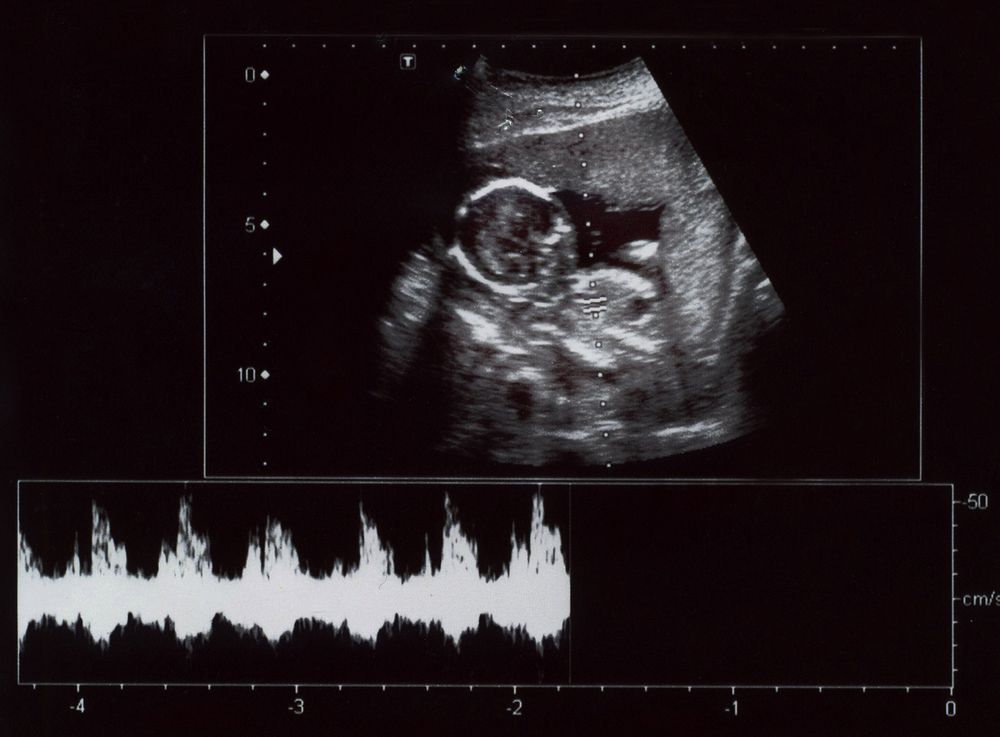

Fetal distress is diagnosed by reading the baby’s heart rate. A slow heart rate, or unusual patterns in the heart rate, may signal fetal distress.

Sometimes fetal distress is picked up when a doctor or midwife listens to the baby’s heart during pregnancy. The baby’s heart rate is usually monitored throughout the labour to check for signs of fetal distress.

The baby’s heart rate is usually monitored throughout the labour to check for signs of fetal distress.

Another sign is if there is meconium in the amniotic fluid. Let your doctor or midwife know right away if your notice the amniotic fluid is green or brown since this could signal the presence of meconium.

How is fetal distress managed?

The first step is usually to give the mother oxygen and fluids. Sometimes, moving position, such as turning onto one side, can reduce the baby’s distress.

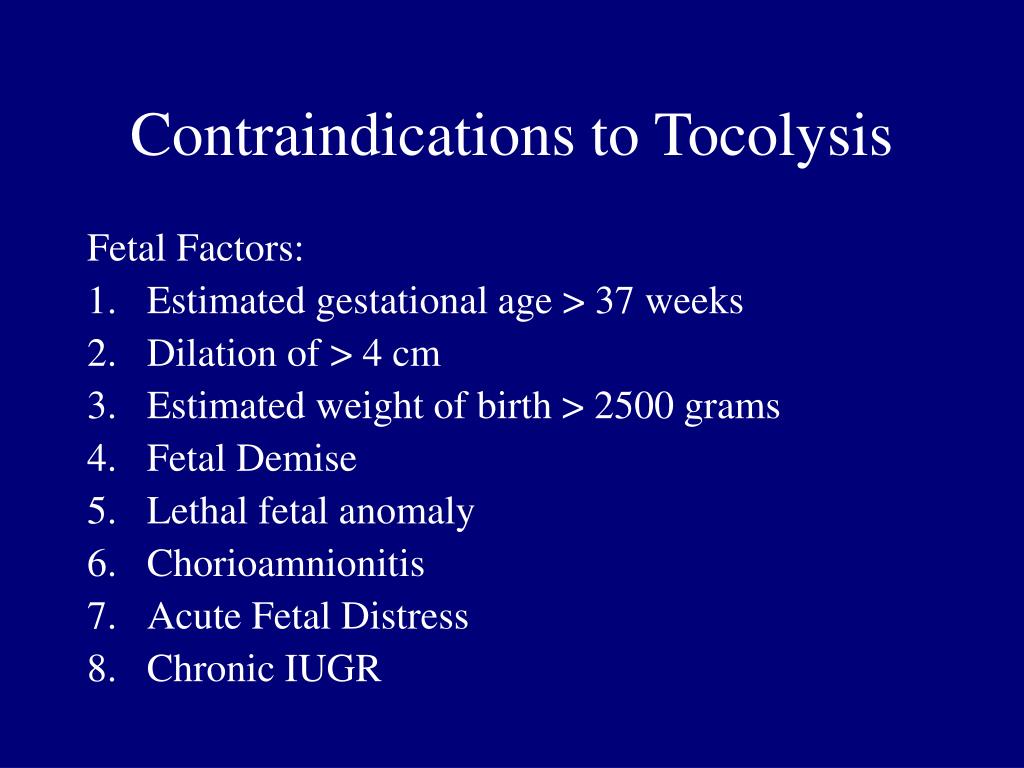

If you had drugs to speed up labour, these may be stopped if there are signs of fetal distress. If it’s a natural labour, then you may be given medication to slow down the contractions.

Sometimes a baby in fetal distress needs to be born quickly. This may be achieved by an assisted (or instrumental) delivery which is when the doctor uses either forceps or ventouse (vacuum extractor) to help you deliver the baby, or you might need to have an emergency caesarean.

Does fetal distress have any lasting effects?

Babies who experience fetal distress, such as having an usual heart rate or passing meconium during labour, are at greater risk of complications after birth. Lack of oxygen during birth can lead to very serious complications for the baby, including a brain injury, cerebral palsy and even stillbirth.

Lack of oxygen during birth can lead to very serious complications for the baby, including a brain injury, cerebral palsy and even stillbirth.

Fetal distress often requires birth by caesarean section. While this is a safe operation, it carries extra risks to both the mother and baby, including blood loss, infections and possible birth injuries.

Babies born with an assisted delivery can also be at greater risk of short-term problems such as jaundice, and may have some difficulty feeding. Having lots of skin-to-skin contact with your baby after the birth and breastfeeding can help reduce these risks.

You won’t necessarily experience fetal distress in your next pregnancy. Every pregnancy is different. If you’re worried about future pregnancies, it can help to talk to your doctor or midwife so they can explain what happened before and during the birth.

Women whose labour didn’t go to plan often feel quite negative about their birth experience.

If you feel sad or disappointed or traumatised about what happened, it is important to talk to someone. You can contact or talk to a range of people and organisations, including:

You can contact or talk to a range of people and organisations, including:

- Your doctor

- PANDA on 1300 726 306

- Australasian Birth Trauma Association

- Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636

- Call Pregnancy, Birth and Baby to speak to a maternal child health nurse on 1800 882 436

Sources:

Australian Family Physician (Decreased fetal movements: a practical approach in primary care setting), Australasian Birth Trauma Association (What is birth trauma?), Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (Labour and birth), Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (Provision of routine intrapartum care in the absence of pregnancy complications), Birth (The effect of medical and operative birth interventions on child health outcomes in the first 28 days and up to 5 years of age), MSD Manual (Fetal distress), Kidspot (All about foetal distress), King Edward Memorial Hospital (Fetal compromise), Journal of Translational Medicine (Reducing the risk of fetal distress with sildenafil study)Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Last reviewed: January 2020

Back To Top

Related pages

- Labour complications

- Interventions during labour

- Induced labour

- Giving birth - stages of labour

- Fetal heart rate monitoring

- Baby movements during pregnancy

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

Symptoms, Causes, Effects on the Baby, and Malpractice

Health Care Providers Need to Watch for Dangerous Warning Signs in Unborn Babies

The idea that your soon-to-be-born baby could be under distress is enough to make any mother worry.

But how would you know if it were happening? And what exactly does the term “fetal distress” mean in the medical sense?

There is a lot of confusion about fetal distress, and even some medical professionals working in women’s hospitals might be misguided as to what it means.

Fetal distress refers to any sign that an unborn baby is endangered, struggling, or unwell. It is a broadly applicable term that refers to the symptom of a problem, not the cause.

Many different conditions can lead to fetal distress. It is a doctor, nurse, or midwife’s job to understand what those are.

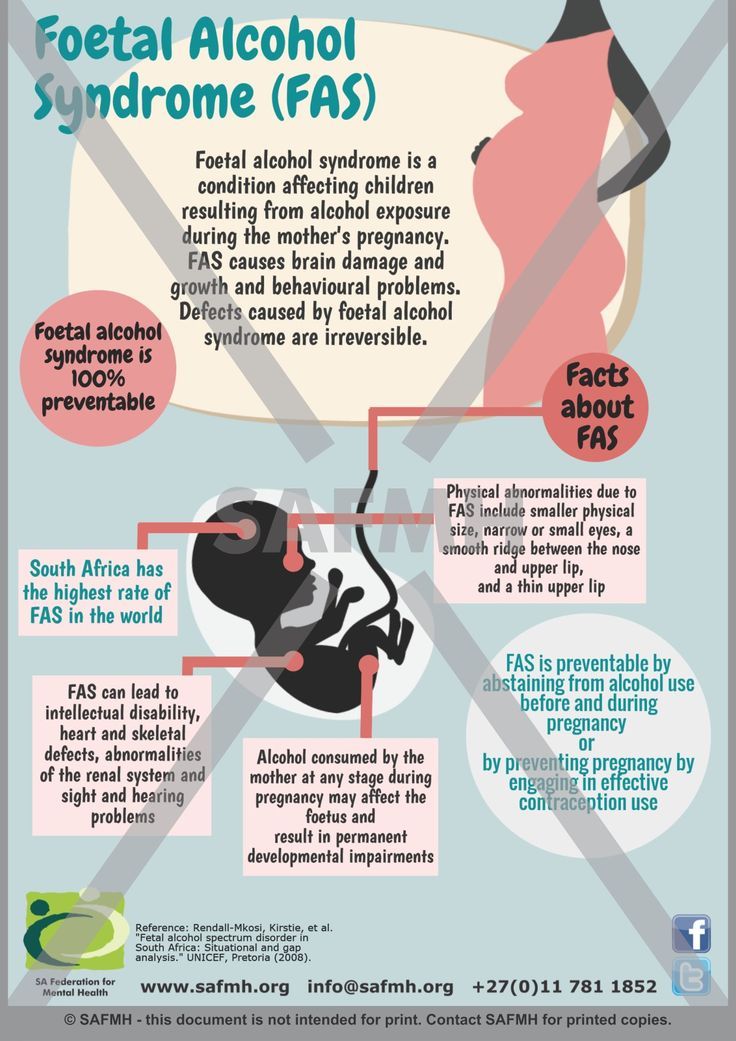

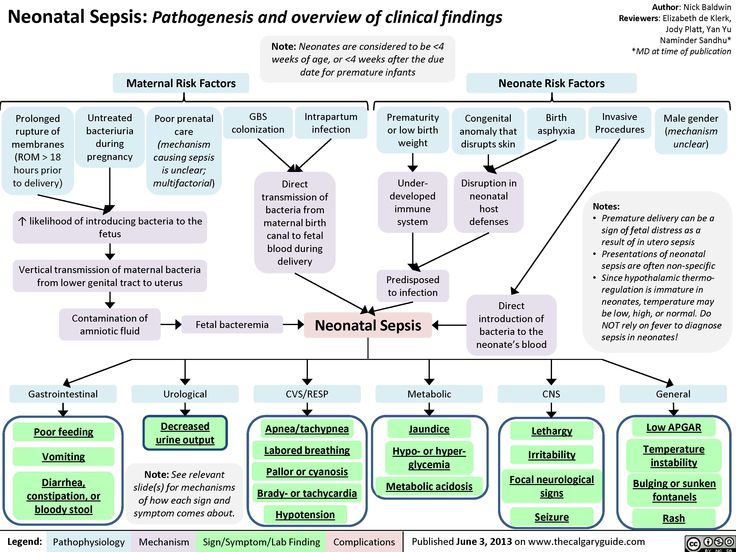

Unfortunately, many people confuse the term “fetal distress” with a different condition, birth asphyxia, in which a baby does not have an adequate oxygen supply. While birth asphyxia is extremely serious and does often lead to distress, many other issues entirely unrelated to oxygen supply can give rise to fetal distress symptoms too.

When doctors, midwives, and nurses don’t know what to look for — or fail to engage in proper monitoring — they can miss critical, life-endangering signs of fetal distress.

As the American Pregnancy Association points out, confusion about the meaning of “fetal distress” has led to inaccurate diagnoses and improper treatment, which can be deadly for both mother and child.

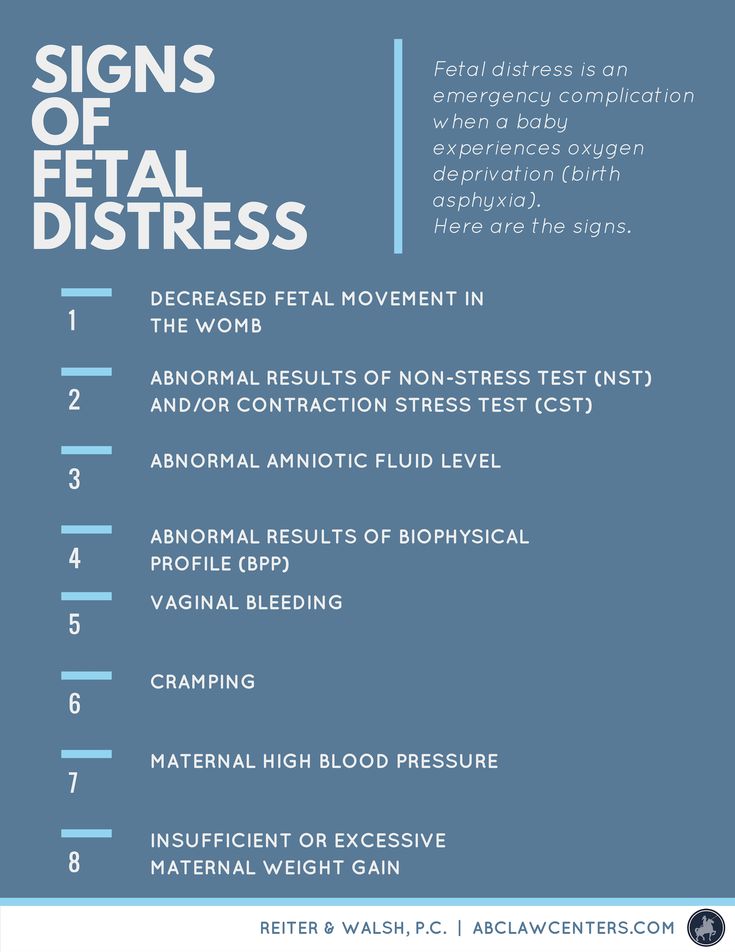

Signs and Symptoms of Fetal Distress

Sometimes, mothers notice signs of fetal distress on their own. These symptoms might include:

- Decreased movement by the baby in the womb

- Cramping

- Vaginal bleeding

- Excessive weight gain

- Inadequate weight gain

- The “baby bump” in the mother’s tummy is not progressing or looks smaller than expected

Some mothers have also a reported a sense that “something doesn’t seem right.” While, in most cases, these anxieties alone are not symptomatic of fetal distress, you may want to visit your doctor for reassurance.

Your care providers should take any sign, symptom, or health concern seriously and then examine you accordingly.

Some signs of fetal distress can only be detected by a doctor or health care provider. These include:

- Abnormal fetal heart rate

- Abnormal fetal heart rhythm

- Abnormal amniotic fluid levels

- Abnormal results of a Biophysical Profile (BPP)

- High blood pressure in the mother

- Failure to progress / failure to thrive

Causes of Fetal Distress

Many conditions can cause, or contribute to, fetal distress. These include:

These include:

- Abnormal positioning of the baby

- Anemia

- Contractions that are too strong or too close together

- Dystocia

- Eclampsia / Preeclampsia

- Forceps / vacuum extraction (when misused)

- Intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR)

- Macrosomia (unusually large baby)

- Meconium (from the baby’s stool) in the amniotic fluid

- Oligohydraminos (amniotic fluid deficiency)

- Placental abruption

- Pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH)

- Post-term pregnancy

- Problems during labor (e.g. prolonged labor, arrested labor)

- Uterine rupture

Effects on the Baby

Fetal distress is a sign that something is wrong. Most cases are serious, and any sign of fetal distress should be treated as a medical emergency.

Understandably, parents are eager to learn about the potential effects of distress on the baby. Remember, however, that fetal distress is a symptom of an underlying cause. The effects will depend on the condition causing distress.

The effects will depend on the condition causing distress.

However, all causes of fetal distress have the potential to lead to serious complications, including permanent injury or disability or death. Some can also lead to the death of the mother.

Monitoring, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Monitoring is the key to identifying fetal distress, treating it before it leads to irreversible complications, and preventing it in the first place.

The most common form of monitoring is Fetal Heart Rate (FHR) monitoring. Through FHR monitoring, health care providers can detect problems related to heart rate and rhythm, oxygen levels, and many other common causes of fetal distress. Ultrasound and other imaging or monitoring may be appropriate as well.

Just as importantly, paying careful attention to overall health and vital signs throughout pregnancy, labor, and delivery is critical to a successful birth.

Treatment depends on the underlying cause, and may range from something as simple as changing the mother’s position or providing fluids to something as urgent as emergency c-section surgery.

Mismanaged Fetal Distress: Birth Injury and Medical Malpractice

Doctors, nurses, and midwives have a duty to monitor both the mother and baby for signs of fetal distress, to accurately diagnose any conditions causing distress, and to provide effective treatment immediately. Failure to do so may constitute medical malpractice in Maryland and in Washington, D.C.

Talk to an Experienced Maryland Birth Injury Lawyer Today

You and your child deserve thorough, attentive, and expert medical care. You depend on your doctors and health care team to identify problems, diagnose dangerous conditions, and respond to them right away. There is simply no excuse for fetal distress that arises or gets worse because of preventable medical negligence.

If you or your baby has suffered and you think a health care provider’s carelessness might be to blame, please contact D’Amore Law right away. Our experienced team of Maryland birth injury attorneys is here to fight for you.

Call 410-324-2000 or contact us online to get started with a free consultation today.

Fetal distress - all you need to know about fetal distress

Sometimes at the last moment of pregnancy, unpleasant things happen that can be very sad. Fetal distress is one such complication that, if not addressed, can lead to problems for both the mother and the baby.

Fetal distress

Fetal distress is subdivided into intrauterine and birth distress. Distress is usually determined by monitoring the child's heart rate. The presence of meconium (the baby's first stool) may also indicate that the fetus is unwell in the womb.

Often referred to as hypoxia or threatened asphyxia, fetal distress occurs when an infant does not receive enough oxygen in the womb or during labor.

What causes fetal distress?

The reason why your unborn baby faces the problem of lack of oxygen can be different. These could be umbilical cord problems, fetal abnormalities, the stress of childbirth, or reactions to certain medications. This can happen due to abnormal fetal development, problems with the placenta, or even multiple births.

These could be umbilical cord problems, fetal abnormalities, the stress of childbirth, or reactions to certain medications. This can happen due to abnormal fetal development, problems with the placenta, or even multiple births.

Fetal monitoring during labor

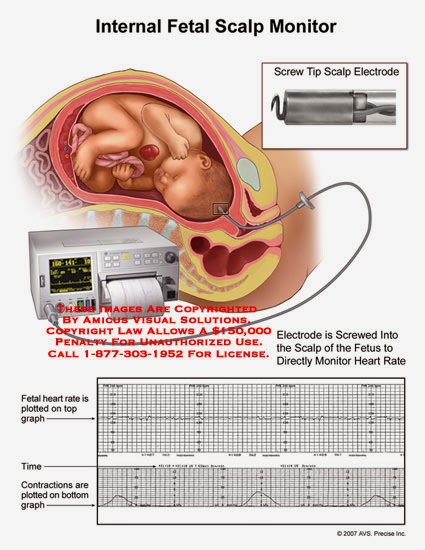

When a pregnant woman gives birth, the baby is constantly monitored. One of the most common methods for monitoring a baby is the use of an electronic fetal monitor (EFM). In this technique, two straps are wrapped around the abdomen, one measures the baby's heart rate, and the other assesses contractions or uterine activity. Monitors are also used to determine if the baby is having problems with each contraction.

For monitoring, doctors may also use a device that is applied to the baby's scalp.

What should be the ideal fetal heart rate?

The results of the electronic fetal monitor are shown on the monitor in diagrammatic form. The doctor and nurses constantly monitor the numbers on the graphs and check if the heart rate is within adequate parameters. The ideal range should be between 110 and 160 beats per minute.

The doctor and nurses constantly monitor the numbers on the graphs and check if the heart rate is within adequate parameters. The ideal range should be between 110 and 160 beats per minute.

A temperature that is too high may indicate that the child is unwell or has a fever. While too low a temperature "speaks" of a lack of oxygen. Monitoring divides indications into 2 categories: accelerated heartbeat and slow heartbeat.

Rapid heartbeat

This means a short-term increase in heart rate, say 15 beats per minute, which can last 15 seconds or more. Accelerated, quite normal, it indicates an abundance of oxygen. For most babies, the heartbeat can speed up several times during the entire birth process.

If the doctor has any suspicions that the fetus is deteriorating, he may cause an increase in the fetal heart rate. Suspicion may arise from:

- Gently touching the mother's abdomen

- As a result of pressing the child's head, with a finger, through the cervix

Slow heart rate

Slow refers to temporary drops in heart rate. It can be divided into three types:

It can be divided into three types:

1. Early Deceleration

This is usually normal and nothing to worry about. Early deceleration occurs when the baby's head contracts. It mostly happens in the later stages of labor as the baby descends through the birth canal. Sometimes this happens during childbirth when the baby is premature or in a state of breech presentation.

2. Late Deceleration

They only happen when contractions are at their peak. Typically, late slows are smooth and shallow dips in heart rate that reflect the contraction that causes them. As long as the baby's heart rate shows an accelerated rhythm, late slowdowns are not a cause for concern. Late decelerations can also be a sign that the baby is not getting the amount of oxygen it needs.

3. Variable Deceleration

Variable decelerations are sudden dips in the fetal heart rate that can lead to serious consequences. These slowdowns mostly occur during childbirth when the umbilical cord temporarily contracts, indicating a decrease in blood flow. Such variable changes in heart rate can be unsafe.

These slowdowns mostly occur during childbirth when the umbilical cord temporarily contracts, indicating a decrease in blood flow. Such variable changes in heart rate can be unsafe.

What to expect from a medical team?

In principle, the procedure for monitoring a child's heart rate is often painless. However, there are several risks associated with difficult birth situations that result in the medical team doing the following:

- Oxygen supply to mother

- Instillation of fluid into the amniotic sac to thicken the meconium (Amnioinfusion is the infusion of Ringer's solution or normal saline into the amniotic sac using a catheter.)

- Instrumentation (forceps/vacuum)

- Caesarean section

Before giving birth, be sure to consult with your doctor, ask him all the necessary and interesting questions. Get your medical card. And go to birth!!!

And remember, vigilance is the Key to a successful birth of your baby!!!

Fetal distress

If your baby does not feel well or is unwell during pregnancy or delivery, doctors call it fetal distress. Fetal distress during childbirth is quite common.

Fetal distress during childbirth is quite common.

There are many reasons why a child may experience distress. Often, health complications affect how much blood, with its essential oxygen and nutrients, reaches the baby through the placenta.

If you are expecting twins or more, one or both of your babies are likely to be in distress.

Your child may be more susceptible to this condition if they are small.

If you are 35 years old or older or have transitioned, your child may be more likely to feel unwell.

Some complications that occur during pregnancy can increase the chance of fetal distress, including:

- Preeclampsia develops, which affects how well the placenta works.

- Too much amniotic fluid or too little amniotic fluid.

- Development of high blood pressure during pregnancy.

- Vaginal bleeding from 24 weeks onwards.

Close to or during labor, some interventions can make your baby more likely to feel unwell. For example, if your baby is in a breech presentation and the doctor is trying to rotate him. Speeding up labor, which can make contractions stronger and more frequent, can also affect how well the baby feels.

For example, if your baby is in a breech presentation and the doctor is trying to rotate him. Speeding up labor, which can make contractions stronger and more frequent, can also affect how well the baby feels.

The list of reasons a child may experience distress is long. This reflects the fact that each pregnancy and childbirth is different, influenced by many factors.

Signs of fetal distress during pregnancy

Pay attention to your baby's movements. If you notice a change in your child's normal movement patterns, this may be a sign that he needs help. The type of movement you feel may change as the due date approaches, but the frequency should remain the same. Even if your baby has less room to move around in the womb, you should still feel strong, frequent, and regular movements.

There is no recommended set number of strokes that you should pay attention to. You must understand what is normal for your child.

Signs of fetal distress during labor

One of the first signs is meconium (baby stool) in your waters when they break. The amniotic fluid is usually clear, tinged with pink, yellow, or red. But if they are black, this is a sign that your child has had meconium. The density of meconium is important. Lumpy meconium causes distress because it can cause problems if it enters a child's airways.

The amniotic fluid is usually clear, tinged with pink, yellow, or red. But if they are black, this is a sign that your child has had meconium. The density of meconium is important. Lumpy meconium causes distress because it can cause problems if it enters a child's airways.

Meconium alone does not always mean there is a problem. If your child has an elevated heart rate, along with meconium, this is a sign of distress. The normal heart rate range for a full-term baby is 110 to 160 beats per minute. Although a low or high heart rate may be a cause for concern, the doctor will look for other symptoms such as:

- no change in the baby's heartbeat

- slow heartbeat after contraction

- baby needs time to recover from each contraction

A fast heartbeat (tachycardia) can also happen if you have a high temperature. A slow heart rate (bradycardia) during contractions can be caused by your position, such as lying on your back.

What happens if there is fetal distress during labor?

If your doctor suspects your child is not feeling well, they may touch your child's scalp to see if he is responding to stimulation. They may also take a tiny sample of blood from your child's scalp. A blood sample will be tested to determine if your child is getting enough oxygen. This is the best indicator of how your child is doing.

They may also take a tiny sample of blood from your child's scalp. A blood sample will be tested to determine if your child is getting enough oxygen. This is the best indicator of how your child is doing.

If all checks show that your child is in distress, the doctor will try to help:

- Raising your fluid levels by offering you a drink or an IV.

- Offering you paracetamol if you have a fever.

- Laying you on your left side to relieve pressure from your uterus on your body's main vein, the vena cava. This prevents a decrease in blood flow to the placenta and the baby.

- Temporarily stop taking any medicines you have been given to make your contractions worse.

If your baby is still showing signs of distress despite these efforts, he will need to be born as soon as possible. How your baby is born depends in part on what stage of labor you have reached and whether your cervix is fully dilated. Your baby may need to be delivered vaginally, with vacuum extraction, or with forceps.