How to tell my child he has autism

How to tell your child they have autism

Experts share their best advice on why, when and how to talk to kids about their autism diagnosis.

Raelene Dundon will never forget the day she realized it was time to tell her preschool son he was autistic.* When they were visiting her eldest son’s classroom for story time, some of the students noticed that the younger boy seemed similar to their autistic classmate and told Dundon’s eldest that his brother had autism. “I suddenly thought, I don’t want other people to know if he doesn’t know. I need to do something about this,” recalls Dundon, an educational and developmental psychologist who works with children and their families. She knew she’d have to tell her child he has autism.

After getting tips from others who had been through the process, that’s what she did. She went on to share what she learned with the families she was working with, and eventually turned her tips into a book called Talking with Your Child about Their Autism Diagnosis: A Guide for Parents.

“Parents often are quite anxious about how or when to tell their kids, and that sometimes stops them, when it’s actually better to have the conversation as soon as possible,” says Dundon, who is director of Okey Dokey Childhood Therapy in Melbourne, Australia.

While every child and situation is different, Dundon and other experts say there are some universal best practices when disclosing a diagnosis to a child.

Why should I tell my child they have autism?

If you don’t tell your child they have autism, there’s a good chance someone else will let it slip, or your child will eventually figure it out themselves, says Kelly Price, a registered psychologist who assesses children for autism in Victoria, B.C. This is particularly true if your child is participating in programs and receiving services for people with autism because the A-word is bound to come up, he adds. “You don’t want someone else to spill the beans before you’ve had the opportunity to describe it yourself,” he says, adding that it’s unfair for parents to withhold information about their child from them when they reach a certain age, and their child may feel betrayed if they do so.

Dundon adds that kids may feel ashamed if they find out they’re autistic from someone other than their parents because it may seem like their parents were trying to hide it. She says it’s important for kids to know that they’re autistic because it helps them understand who they are, particularly in relation to their peers. “Kids do sense that they’re different, and not helping them see why isn’t okay,” she says. “It causes distress because they can’t fit in, they don’t know why things are difficult for them, they feel like there’s something wrong with them. When they do find out, it’s like, ‘Oh, that explains it. But I’ve had all of these years of thinking that I was somehow less than my peers and that there was something wrong.’”

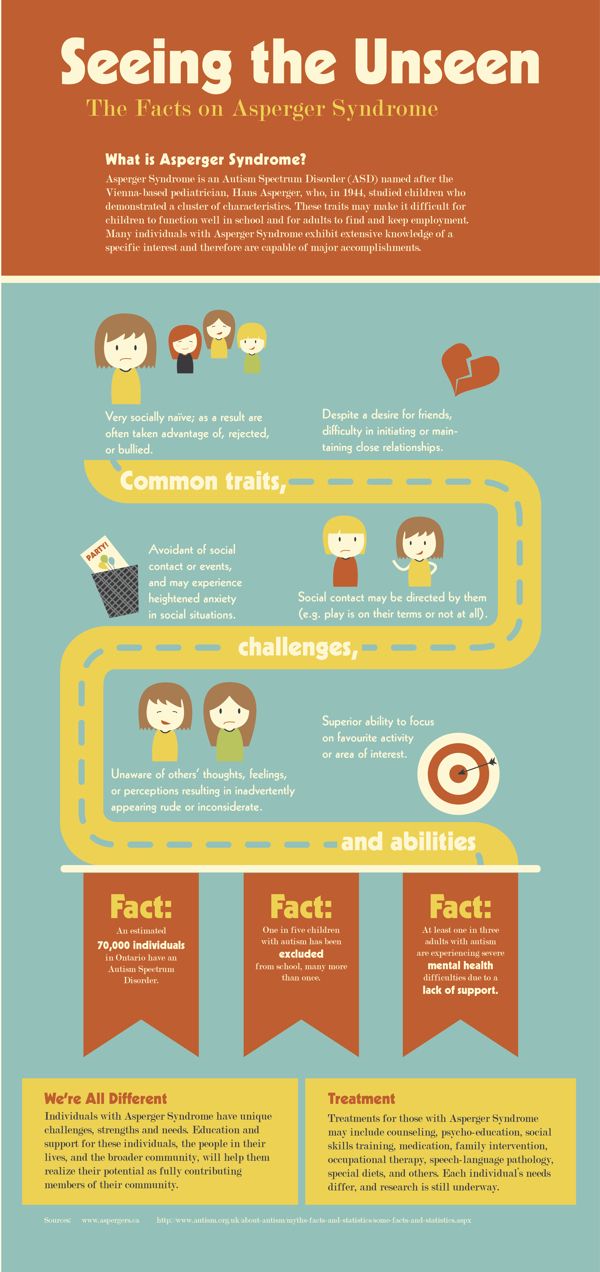

Isabel Smith, a psychologist, professor and the Joan and Jack Craig Chair in Autism Research at Dalhousie University in Halifax, says many children are actually relieved to hear that there’s an explanation for their differences. “It’s reassuring,” she says. “It normalizes things to have a label for it, and it gives them the knowledge that there are others like them who share similarities,” she says. “It allows them to understand that they aren’t sick or weird or abnormal.”

“It normalizes things to have a label for it, and it gives them the knowledge that there are others like them who share similarities,” she says. “It allows them to understand that they aren’t sick or weird or abnormal.”

Janet Arnold, a behaviour consultant who works with children and families in the Greater Toronto Area through her partnership Finding Solutions, says telling autistic children about their diagnosis allows them to learn more about themselves and how to advocate for themselves. “Self-knowledge equals self-acceptance, self-esteem and self-advocacy,” says Arnold, who wrote a book with her professional partner, Francine McLeod, entitled How to Explain a Diagnosis to a Child: An Interactive Resource Guide for Parents and Professionals. “We want children to have a voice, and the only way they really can have a voice is if they understand who they are.”

When should I tell my child they have autism?

When to tell your child they have autism depends on their age, cognitive ability and social awareness, as well as your readiness to have the conversation, says Arnold. “There’s no right age. It depends on the child and the family,” she says, adding that it’s not a one-time conversation but an ongoing process.

“There’s no right age. It depends on the child and the family,” she says, adding that it’s not a one-time conversation but an ongoing process.

In general, though, the experts agree that the earlier you start the dialogue, the better. This doesn’t just ensure the news comes from you; starting early also allows you to tap into younger kids’ accepting nature. “It’s only as kids become older and start to acquire the prejudices of society at large that they see those differences as negative things,” Smith says. “Starting earlier allows you to help break down the stigma and capitalize on this more positive view that we’re all different and we’re all of value.”

Dundon recommends setting the stage for the conversation before the assessment even happens. “You wouldn’t say, ‘We’re going to assess if you’re autistic,’ but you might say, ‘We’re going to see some people to get a bit more of an idea of how your brain works,’” she says. “Then, after the assessment, you can tell them what the results are. ”

”

She adds that having a child receive a diagnosis can be difficult for parents and they need to process their feelings before talking to their kids. “It’s really important that they are in the right head space to talk to their child in a way that’s going to be positive and affirming,” she says. “If they’re going to burst into tears telling their child they’re autistic, then that’s not the time to be telling them.”

If you’re still struggling to start the conversation after a couple of months, consider speaking with a health professional about your feelings. “In most jurisdictions, the parent is the one who’s going to take the lead in doing a lot of the therapy, so they have to get help with it, move on and turn that distress into something more constructive,” says Price.

Smith says many families find it helpful to have a conversation with a health professional, such as the psychologist who did the assessment, to help them figure out how to broach the subject with their kids. Many health professionals will even offer to facilitate that first conversation about the diagnosis with the child and the parents, she says.

Many health professionals will even offer to facilitate that first conversation about the diagnosis with the child and the parents, she says.

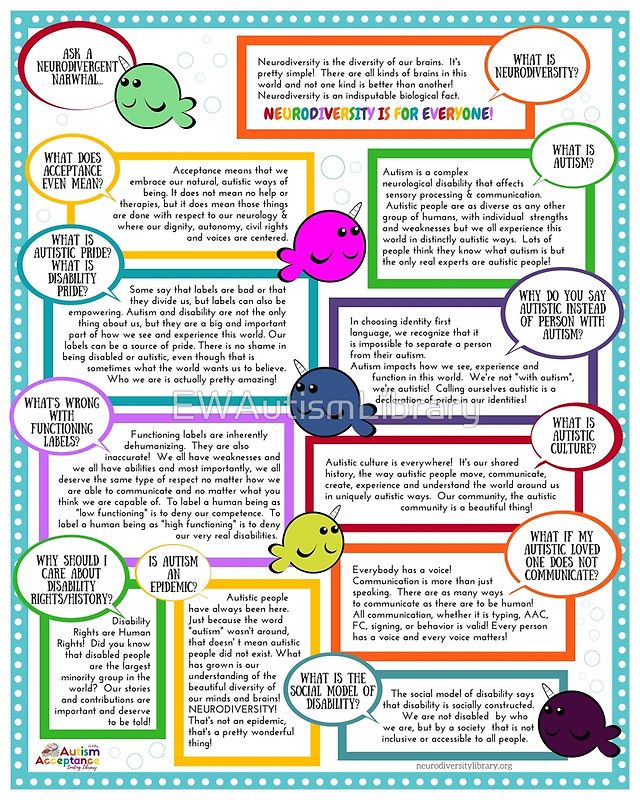

The experts also encourage parents to do their research on autism and how to discuss it with their child before having “the talk.” This may include connecting with other parents through support groups; reading information on the websites of reputable autism organizations; reading books for adults and kids about autism, differences and how to discuss a diagnosis; and reading information from the perspectives of autistic people.

If you decide to hold off on telling your child they have autism, Arnold says it’s important to be vigilant in looking for signs that it’s time to bite the bullet. She says such signs include behaviour changes like withdrawing or acting out, negative self-talk, comparing themselves to others and asking questions like, “What’s wrong with me? Why am I different? Why is this so hard for me?”

Some kids will have these thoughts but not express them, so it’s important to check in with other people involved in your child’s care to see if they’ve noticed any changes.

1) Integrate autism into everyday conversation

If your child is diagnosed young, say as a toddler or preschooler, the experts recommend integrating autism into everyday conversation right from the start. Smith says parents can do this when the child is receiving autism interventions, attending social events for children with autism or watching TV or reading books that feature autistic characters. It’s as simple as saying, “We’re going to the doctor today because you have autism,” or “Julia from Sesame Street is autistic like you.”

“Rather than avoiding the A-word, it’s just a matter of fact in family life,” Smith says. “There often isn’t a need to be direct about telling them because they’ll grow up knowing that word, and that it’s something characteristic of them.”

Some families prefer talking about the differences in how their child thinks and perceives things before introducing the word “autism,” says Dundon, and that’s totally fine. She recommends mentioning differences or autism in the context of a child’s strength and challenges or by highlighting similarities and differences to others. For instance, “Your autistic brain is really sensitive to those noises,” or, “Your brain works a bit differently than your brother’s because you are autistic.”

She recommends mentioning differences or autism in the context of a child’s strength and challenges or by highlighting similarities and differences to others. For instance, “Your autistic brain is really sensitive to those noises,” or, “Your brain works a bit differently than your brother’s because you are autistic.”

“The more naturally it’s brought into conversation, the better, because then it just becomes a part of who they are,” she says. “It’s really about helping them see that they have differences, and some challenges associated with those differences, and that’s okay.”

Price recommends using autism to describe some of your child’s behaviours. For instance, “When it’s hard for you to stop playing that game, that’s because of your autism. Sometimes people who have autism have really strong interests.”

2) Set the stage for a positive conversation

Price recommends having the conversation when your kid is calm and happy and things are going well. “I wouldn’t pull out the autism term when they’re having a tantrum,” he says. “You don’t want it to have a negative connotation.” He also suggests keeping it light and casual. “You don’t want the kid to remember that day you sat them down and told them they have autism because that makes it too much of a thing. It makes it seem like it’s bad news for them.”

“I wouldn’t pull out the autism term when they’re having a tantrum,” he says. “You don’t want it to have a negative connotation.” He also suggests keeping it light and casual. “You don’t want the kid to remember that day you sat them down and told them they have autism because that makes it too much of a thing. It makes it seem like it’s bad news for them.”

Arnold suggests thinking about where the great conversations in your family happen—whether it’s around the dinner table, on a long car ride or curled up in bed—and doing it there.

3) Focus on strengths, challenges and differences

Once you’re settled in for the conversation, a simple way to open it is by mentioning the assessment process, Dundon says, adding that you can start with something like, “You know how you did all those special activities? We found out that your brain works a bit differently and that’s called autism.” Consider explaining how autistic and neurotypical brains work differently by using an analogy like Mac and PC computers: “They just do things a little bit differently,” Dundon says. “It doesn’t mean that one is any less than the other.”

“It doesn’t mean that one is any less than the other.”

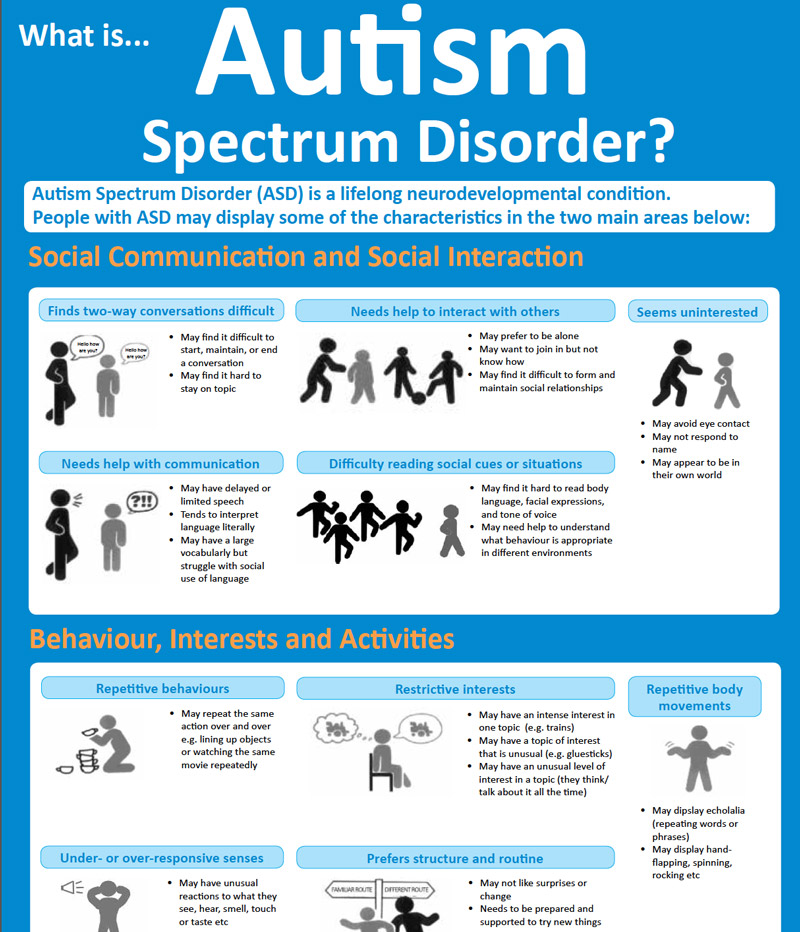

Another option is to start by talking about strengths, challenges and differences in general. Smith suggests discussing the things your child is good at and the things they struggle with, and then doing the same thing for other people like siblings and classmates. “You want to help the child understand that everyone has highs and lows in terms of abilities and interests,” she says. This makes it easier to fold autism into the conversation, she says, which you can do by saying something like, “Autism is a word that describes some of the strengths and challenges that you have.”

When you do introduce autism, all of the experts recommend taking an individualized approach by using concrete examples of your child’s strengths and challenges to explain how their brain works, keeping it positive as much as possible. For example, Dundon suggests saying something like, “You know how it’s hard for you to talk to some of the kids at school, or you feel a little bit awkward, or you’re not sure why they do the things they do? It’s because of the way that your brain works, and that means that you follow different social rules and have a different way of communicating than some other kids and that’s called autism. ”

”

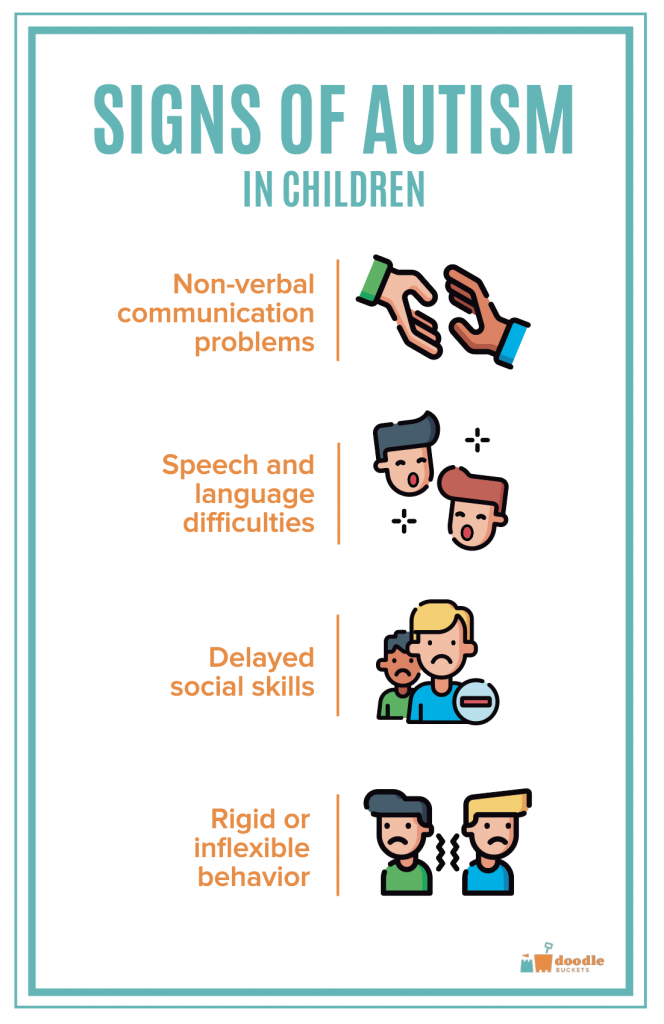

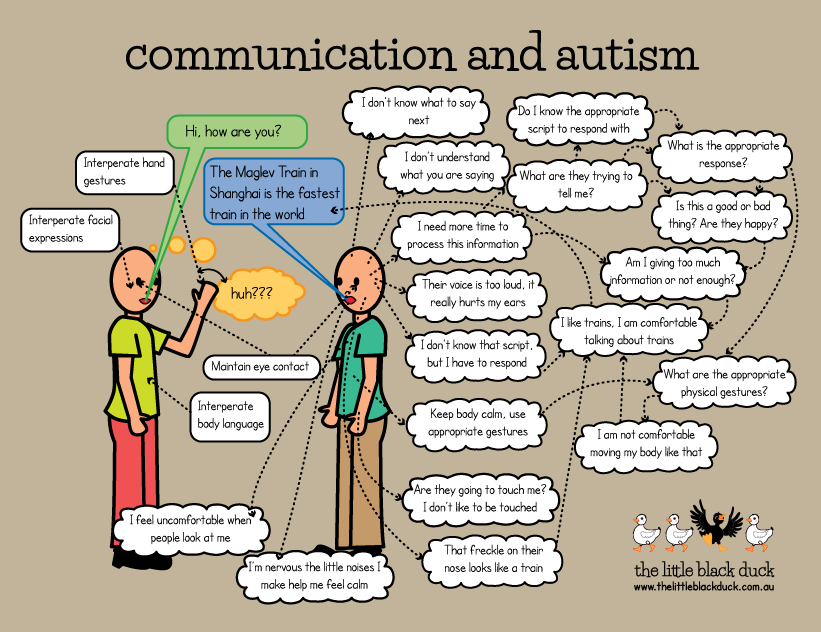

Price recommends following up on that approach by explaining what autism is by drawing on the diagnostic criteria. For instance, if you’re talking about a social challenge your child has, he suggests saying something along the lines of, “Autism is difficulties with social communication like eye contact and conversation. Do you think you have difficulties with those things?”

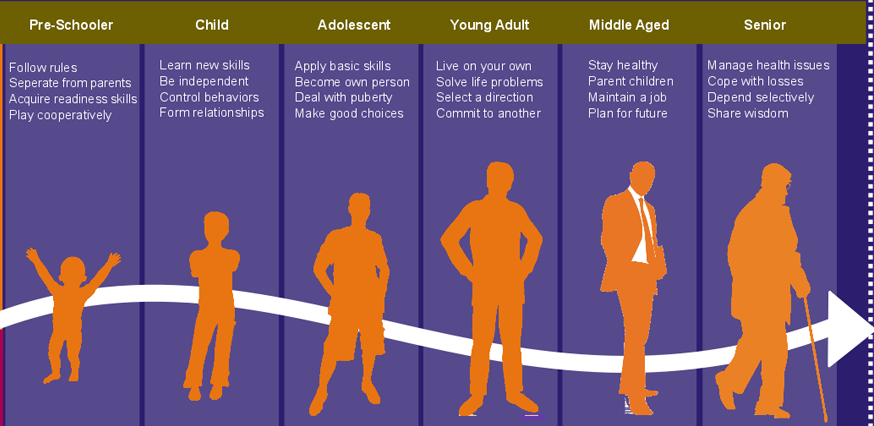

Arnold urges parents to follow their child’s lead, keep it age-appropriate and add information over time. She compares talking to your kid about autism to talking about the birds and the bees. “If a child says, ‘Where do babies come from?’ you’re going to explain different information at different stages depending on your family dynamics and values,” she says. “It’s a process.”

4) Let them know there’s help and community

Once you’ve told your child they have autism, the experts say you should let them know that there’s help for some of their challenges. For instance, if they have difficulties with communication, you can tell them about speech therapy. If they’re sensitive to loud environments, you can offer them headphones.

If they’re sensitive to loud environments, you can offer them headphones.

Smith says parents can also help kids learn more about autism by providing them with kids’ books on the subject, particularly those written by autistic people. For example, Dundon, who is autistic, wrote the Max and Barnaby series of books about an autistic boy who navigates social situations with the help of his pet lizard. Smith recommends parents look for books that feature autistic children with similar skills profiles to their children to ensure they can connect to the story.

She also encourages parents to let their kids know that there’s a thriving community of autistic children out there and lots of opportunities to connect through things like autistic youth groups and social activities. “Receiving a diagnosis gives a child access to a peer group, which is a huge gain if they may not have had much positive peer interaction.”

5) Be ready for your child’s reaction and questions

From relief and indifference, to shock and confusion, to sadness and anger, kids can have a range of emotions when they hear they have autism. “We’ve seen the whole spectrum,” Arnold says.

“We’ve seen the whole spectrum,” Arnold says.

Negative self-talk like, “This is why no one likes me,” may also bubble up during the conversation. “It’s okay to say, ‘These are big feelings, and it must feel kind of crappy right now,’” Arnold says, adding that parents can try to bring the conversation back to how everyone is different and has unique strengths and challenges, and even mention how there are all sorts of famous and successful people with autism, such as Greta Thunberg.

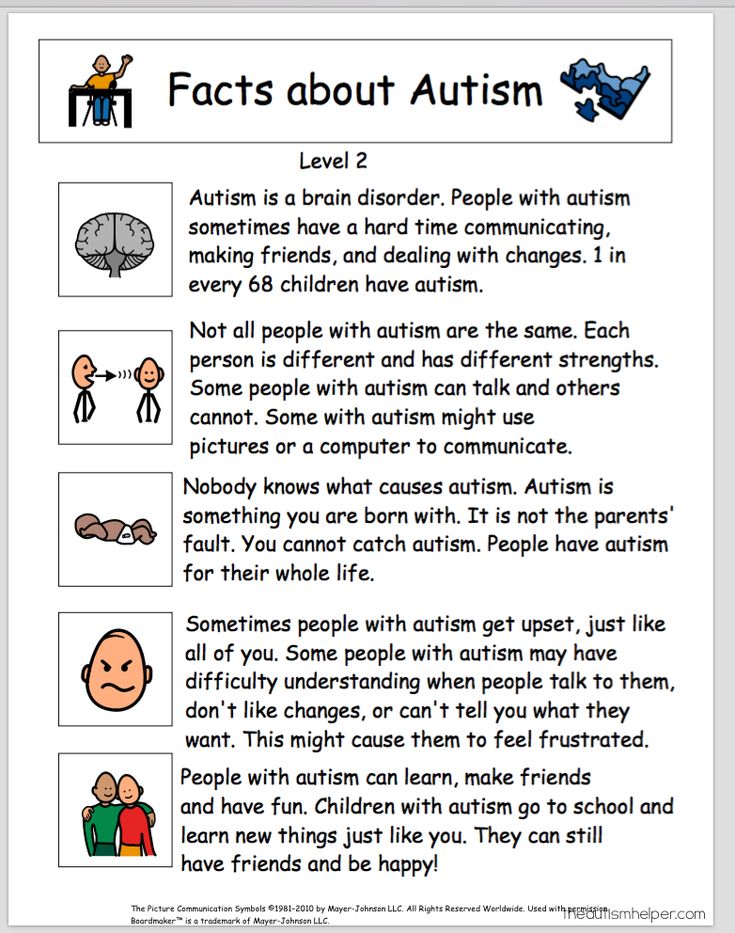

Be ready for your kids’ questions. Some common ones the experts have heard are “How did I get it?,” “Is it contagious?” and “Will it go away?” Questions like these are an opportunity to explain that they were born with autism, all kids’ brains develop differently and while it won’t go away, they can get help with their challenges.

Arnold adds that it’s okay to not have all the answers. “You can say, ‘I’m not sure, let’s research that together.’ Or, ‘Why don’t you give me a few days, I’m going to get back to you. ’”

’”

6) Keep the conversation going

Once you’ve told your child about their diagnosis, keep the conversation going. At first you can do this by asking them how they’re feeling after that first conversation or if they have any questions and then check in every week or two to see how things are going, Arnold suggests.

Both Arnold’s and Dundon’s book include activities you can do with your child to help them better understand themselves and their diagnosis and keep autism in the conversation. For instance, Arnold’s book has a family and friends worksheet, which allows kids to look for similarities and differences in people close to them and consider what makes everyone unique. Arnold says this is a great activity to do with the whole family.

As time goes on, you can look for incidental opportunities to bring up autism. For instance, you can keep an eye out for stories about people with autism in the news and bring them up at the dinner table. “You want to be weaving it into as many conversations as possible and not letting it slip away from their awareness, but not dwelling on it and trying to talk about it every day,” Price says.

*This article uses both person-first and identity-first language as members of the autistic community have different preferences.

Stay in touch

Subscribe to Today's Parent's daily newsletter for our best parenting news, tips, essays and recipes.- Email*

- CAPTCHA

- Consent*

Yes, I would like to receive Today's Parent's newsletter. I understand I can unsubscribe at any time.**

FILED UNDER: austism spectrum disorder Autism disabilities health service seo Special needs

Getting Started: Introducing Your Child to His or Her Diagnosis of Autism: Learn About Autism: Indiana Resource Center for Autism: Indiana University Bloomington

Many parents are fearful that labeling their child as having an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) will make him or her feel broken, or that they may use their label as an excuse to give up and not try. Adults on the autism spectrum have found the opposite to be true. Giving your child information on the nature of his/her differences will give them a better understanding and the motivation that is needed to drive through challenges.

Adults on the autism spectrum have found the opposite to be true. Giving your child information on the nature of his/her differences will give them a better understanding and the motivation that is needed to drive through challenges.

Discussing an autism spectrum diagnosis with your child is an important issue and one for which many parents seek advice. This article will focus on aspects of explaining your child’s diagnosis to him or her, and provide resources that can assist and guide you.

Why Tell?

Parents go through a range of emotions when given their child’s diagnosis. The hope is that you have found support to help you in this new journey. Isn’t it just as important to consider that your child should also be given information and support for understanding and coping with their new diagnosis? All children need to be understood and respected. At some point, people who are successful have learned who they are, and accept and use that information to help themselves become the best they can be in life. Children with an autism spectrum diagnosis should have the chance to understand, accept and appreciate their uniqueness by being given information about their diagnosis.

Children with an autism spectrum diagnosis should have the chance to understand, accept and appreciate their uniqueness by being given information about their diagnosis.

You may fear a number of things if you tell your child (and others) about the diagnosis. You may fear that your child will not understand, that your child may lose some of his/her options in life, that your child will become angry or depressed because they have a disability, that your child (or others) will use the disability as an excuse for why they cannot do something, or even that your child will think of themselves (or others will think of your child) as a complete failure with no hope for a positive future. These issues and others may or may not surface whether or not the child and others are told of the diagnosis. All issues can be addressed, if needed. Shouldn’t all involved, including your child, have important information since the diagnosis will affect various aspects of his or her life?

Consider the stories of many individuals with an autism spectrum diagnosis who were not told, and/or were not diagnosed until they were adults. Not understanding others or social situations for many leads to poor interactions with others and resulted in ridicule and isolation. Some adults on the autism spectrum share how they felt that they were a disappointment and failure to their families and others, but had no clue why they failed or how to do better. Over time, the result can be low self-esteem and/or self-acceptance problems among other issues. Given correct information about their diagnosis and differences, along with support, many of these individuals explain they have become successful.

Not understanding others or social situations for many leads to poor interactions with others and resulted in ridicule and isolation. Some adults on the autism spectrum share how they felt that they were a disappointment and failure to their families and others, but had no clue why they failed or how to do better. Over time, the result can be low self-esteem and/or self-acceptance problems among other issues. Given correct information about their diagnosis and differences, along with support, many of these individuals explain they have become successful.

Your child may know that s/he is different, but like all children at certain developmental stages, they may come to the wrong conclusion about their perceived differences. They may even wonder if they have a terminal illness and are going to die. They see doctors and therapists and go for treatments, but are not told why. Even the child or adult who does not ask and/or verbally express concern about being different may still be thinking those thoughts. Even children with autism spectrum disorders, like all children, may sense the frustration and confusion of others and make wrong assumptions about the cause of the turmoil around them.

Even children with autism spectrum disorders, like all children, may sense the frustration and confusion of others and make wrong assumptions about the cause of the turmoil around them.

When to Tell?

There is no exact age or time that is correct to tell a child about their diagnosis. A child’s personality, abilities and social awareness are all factors to consider in determining when a child is ready for information about their diagnosis. If older when told, they may be extremely sensitive to any suggestion that they are different. You can look for the presence of certain signs that the child is ready for information. Some children will actually ask, “What is wrong with me?” “Why can’t I be like everybody else?,” “Why can’t I _____?,” or even “What is wrong with everyone?.” These types of questions are certainly a clear indication that they need information about their diagnosis. Some children, however, may have similar thoughts and not be able to express them well.

Some children do not get a diagnosis until they are in their teens or older. Frequently, those who are diagnosed later have had some bad experiences that can influence the decision of when to share information with them about their diagnosis. They may be very sensitive to any information that suggests they are different. On the other hand, an older child may already know about a previous diagnosis such as Attention Deficit Disorder, Conduct Disorder, and/or a mental health disorder of some kind. Because of this history with another label or diagnosis, it may be an appropriate time to share the diagnosis and some concrete information about ASD.

Frequently, those who are diagnosed later have had some bad experiences that can influence the decision of when to share information with them about their diagnosis. They may be very sensitive to any information that suggests they are different. On the other hand, an older child may already know about a previous diagnosis such as Attention Deficit Disorder, Conduct Disorder, and/or a mental health disorder of some kind. Because of this history with another label or diagnosis, it may be an appropriate time to share the diagnosis and some concrete information about ASD.

Many adults with an autism spectrum diagnosis express the view that children should be given some information before they hear it from someone else, and/or overhear or see information that they sense is about them. A child may believe that people do not like them and/or that they are always in trouble, but do not know why. If given a choice, waiting until a negative experience occurs to share the information is probably not the best option.

What/How to Tell?

Staying positive when talking about ASD is very important. Autism spectrum disorders are complex. Everyone with a diagnosis is unique. It is important that the process of explaining an autism spectrum diagnosis to a child is individualized and meaningful to them. As you begin, it can be hard to decide what and how much information to share. If the child has asked questions, it will give you a place to start. Make sure that you understand what they are asking.

Many families have found that setting a positive tone about each family member’s uniqueness is a wonderful starting place. A positive attitude about differences can be established if you start as early as possible, and before the diagnosis is mentioned by others. Everyone is in fact unique with his or her own likes and dislikes, strengths and weaknesses, and physical characteristics. Differences are discussed in a matter of fact manner as soon as the child or others their age understand simple concrete examples of differences. With this approach, it is more likely that differences, whatever they are, can be a neutral or even fun concept. Matter of fact statements such as “Mommy has glasses and Daddy does not have glasses” or “Bobby likes to play ball and you like to read books” are examples. The ongoing use of positive concrete examples of contrasts among familiar people can make it easier to talk about other differences related to your child’s diagnosis with him or her.

With this approach, it is more likely that differences, whatever they are, can be a neutral or even fun concept. Matter of fact statements such as “Mommy has glasses and Daddy does not have glasses” or “Bobby likes to play ball and you like to read books” are examples. The ongoing use of positive concrete examples of contrasts among familiar people can make it easier to talk about other differences related to your child’s diagnosis with him or her.

Consider your child’s ability to process information and try to decide what and how to tell. For those children who have a keen interest in their diagnosis and those whose reading ability is good, there are currently a few books written by children with an autism spectrum diagnosis that may be of interest (Hall, 2001; Jackson, 2003; Krauss, 2010).

There are also many more books written by adults with an autism spectrum diagnosis. Some of these books are meant to be read by any interested persons, but many are meant to be read by others with a diagnosis of an autism spectrum disorder. Authors with an autism spectrum diagnosis are reaching out to others with a diagnosis by sharing experiences, sharing tips on life’s lessons, and helping the reader feel that they are not alone in this journey (Endow, 2012; Finch, 2012; Soraya, 2013; Willey, 2015; Zaks, 2006).

Authors with an autism spectrum diagnosis are reaching out to others with a diagnosis by sharing experiences, sharing tips on life’s lessons, and helping the reader feel that they are not alone in this journey (Endow, 2012; Finch, 2012; Soraya, 2013; Willey, 2015; Zaks, 2006).

Most children may need minimal information to start. More information can be added over time. Again, be as positive as possible. Your positive attitude and the manner in which you convey the information is important. To make what you discuss with your child meaningful, you can begin by talking about any questions that s/he has asked. You may want to write down key points and tell him or her that others with this diagnosis/disability also have some of the same questions and experiences. Then you could ask if they would like to find more information by reading books, watching videos, and/or by talking with other people. If asking your child if they want information is likely to get a “no” response, you may choose to not ask. However, tell them that you will be looking for information and would like to share it with them. Let them know they can ask any question they want at any time they want.

However, tell them that you will be looking for information and would like to share it with them. Let them know they can ask any question they want at any time they want.

Frequently, when individuals with an autism spectrum diagnosis have an opportunity to meet others with ASD, they find it is an eye opening and rewarding experience. Individuals with an autism spectrum diagnosis can sometimes better understand themselves and the world by interacting with others who have an autism spectrum diagnosis. Interacting with others on the autism spectrum can help individuals realize there are other people that experience the world the way they do, and that they are not the only one.

There are various possibilities for “meeting” others on the spectrum. A few camps around the country offer various programs specifically for those on the autism spectrum. Some agencies and organizations offer playgroups for children and/or social activity groups for teens. There are also Listservs and Facebook groups some hosted by individuals with an autism spectrum diagnosis. It is important you check these online forums for safety. Some conferences for parents and professionals offer sessions and other events for teens and adults on the autism spectrum. Most of us can relate to an interest in connecting with people who are like us.

It is important you check these online forums for safety. Some conferences for parents and professionals offer sessions and other events for teens and adults on the autism spectrum. Most of us can relate to an interest in connecting with people who are like us.

Workbooks that provide a structured guide for the process of telling a child with ASD about their diagnosis (Faherty, 2014; Vermeulen, 2012) are readily available. The workbook format is designed to provide activities that help organize information about an autism spectrum diagnosis as well as making the information more child specific and concrete. The different lessons suggest how the information is shared with your child. The child and a trusted adult working together can complete the worksheets. In many cases, worksheets can also be modified for different ages and functioning levels of the child who would be using the materials.

Who Tells/Where to Tell?

Certainly circumstances vary from family to family. If your child is asking questions don’t put off answering them. You should be forthcoming and not suggest talking about it later. Not providing an answer could increase the child’s anxiety and make the topic and information more mysterious.

If your child is asking questions don’t put off answering them. You should be forthcoming and not suggest talking about it later. Not providing an answer could increase the child’s anxiety and make the topic and information more mysterious.

For many families, using a knowledgeable professional to begin the disclosure process instead of a family member or a friend of the family might be the best option. Having a professional involved, at least in the beginning stages of disclosure, leaves the role of support and comfort to the family and those closest to the child. For someone with an autism spectrum disorder, it can be especially hard to seek comfort from someone who gives you news that can be troubling and confusing. Having a professional whose role is clearly to discuss information about the child’s diagnosis and how the disability is affecting his/herlife can make it easier for family members to be seen by the child as supportive. The professional discussing information with the child about his/her disability can also help the parents understand the child’s reaction and provide suggestions for supporting their child. Having a professional involved also allows the use of a location outside of the family home for beginning this process.

Having a professional involved also allows the use of a location outside of the family home for beginning this process.

Explaining an autism spectrum diagnosis to an individual can not be done in one or two encounters. The individual needs time to assimilate the new information about him/herself at their own pace. It may take weeks or months before the child initiates comments or asks questions about the new information. The process of explaining an autism spectrum diagnosis is ongoing. Making the information meaningful from the child’s point of view will greatly enhance the learning process. A positive focus helps maintain self esteem and an effective atmosphere for learning. There are materials available to help this learning process and hopefully you have others that know your child who can help support you and your child in this process. Now, is it time for you to get started?

Resources

Dundon, R. (2018). Talking with your child about their autism diagnosis: A guide for parents. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kinsley Publishers.

Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kinsley Publishers.

Dura-Vila, G. & Levi, T. (2014). My autism book: A child’s guide to their autism spectrum diagnosis. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Endow, J. (2012). Learning the hidden curriculum: The odyssey of one autistic adult. Shawnee, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Faherty, C. (2014). What does it mean to be me? A workbook explaining self-awareness and life lessons to the child or youth with high-functioning autism or Aspergers (2nd ed.). Arlington, TX: Future Horizons, Inc.

Finch, D. (2012). The Journal of best practices: A memoir of marriage, Asperger Syndrome, and one man's quest to be a better husband. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Hall, K. (2001). Asperger Syndrome, the universe and everything. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kinsley Publishers Ltd.

Jackson, L. (2003). Freaks, geeks and Asperger syndrome: A user guide to adolescence. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers Ltd.

Kraus, J. D. (2010). The Aspie teen’s survival guide: Candid advice for teens, tweens, and parents, from a young man with Asperger’s Syndrome. Arlington, TX: Future Horizons, Inc.

D. (2010). The Aspie teen’s survival guide: Candid advice for teens, tweens, and parents, from a young man with Asperger’s Syndrome. Arlington, TX: Future Horizons, Inc.

Soraya, L. (2013). Living independently on the autism spectrum. Avon, MA: F+W Media, Inc.

Vermeulen, P. (2013). I am special: Introducing children and young people to their autistic spectrum disorder (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Willey, L.H. (2015). Pretending to be normal: Living with Asperger Syndrome (Autism Spectrum Disorder) (Exp.ed.) Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Zaks, Z. (2006). Life and love: Positive strategies for autistic adults. Shawnee, KS: Autism Asperger Publishing.

Wheeler, M. (2020, May). Getting started: Introducing your child to his or her diagnosis of an autism spectrum disorder. https://www.iidc.indiana.edu/irca/learn-about-autism/getting-started-introducing-your-child-to-his-or-her-diagnosis-of-autism.html.

Should I tell my child that he has autism?

01/01/16

Recommendations of a specialist and mother of a son with autism to other parents

Author: Lisa Joe Rudy / Lisa Jo Rudy Source: Autism. About.com 9000

About.com 9000

9000 9000 9000

with us I never had "that" conversation with my son. Tom always knew he had autism. After all, he worked with behavioral therapists almost every day… was in a resource class at school… and was generally, well, different.

However, for other families, autism is not as obvious and obvious in a child's life. For example, a child may not have a speech delay, may have relatively minor social and sensory problems, and may be in a mainstream school (no extra accompaniment or special class).

Such a child may be intellectually and socially on a par with his peers in kindergarten and even in the lower grades of school. But then, says Brenda Dater, author of Parenting Without Panic, the rough years come.

“Sometimes,” says Dater, “the diagnosis doesn't come up until the third or fifth grade, when social and academic standards rise dramatically. The environment and the demands on the child change a lot.” Sometimes parents only during this period turn to a specialist and find out that the child has an autism spectrum disorder.

Should parents tell their child about his diagnosis? Some parents don't want to do this. They fear that such knowledge will only undermine the child's self-esteem or become a convenient excuse for him. However, Dater believes that in general it is better to inform the child about his diagnosis. There are two reasons for this.

First, she says, “Children are getting more and more dissatisfied with themselves. They want everything in their life to be completely different, but for some reason this does not happen. They have to come up with excuses and reasons for themselves.”

I hear this story over and over again. The child is dissatisfied with himself and others. He can't understand why he can't do what others can easily do. He cannot understand other people. As a rule, such a child comes to one of two conclusions. The first conclusion is that he is stupid, worthless, and he will never succeed. The second conclusion is that everyone around is idiots, and I don't care what they might think.

For such a child, knowing about the diagnosis is a necessary tool to understand himself.

This information allows children to realize that if something is harder for them than for others, then there is an objective reason for this. And they can get support and resources to cope.

Second, Dater says, you can't ask for help if you don't know you need it. “Disclosure of the diagnosis is closely related to the ability to defend one's interests. If your child does not understand himself, then there is no chance that he can explain his difficulties to other people, ask for help, understand what is useful for him and what is not, and even just remain calm.

Understanding oneself and being able to stand up for oneself becomes more and more important as the child grows older. In the real world, people who think and learn differently are unlikely to get support by default, but if they are able to understand and explain what kind of support they need, then getting help is easier.

Dater explains it this way: "You can be silent about your difficulties in academic and social situations, but people will still notice them, and they will come up with their own explanations for why you behave this way." Very often, such explanations are much worse than autism - "she despises everyone", "he's just some kind of psycho", "he takes something", and so on.

But isn't autism itself prejudiced? Regarding this, Dater writes: “It is not necessary to talk to others about “autism” or “Asperger's syndrome”. Sometimes it's enough to say, "I'm having a hard time with this" or "Could you do it this way?" If you need help, then you need help - if you pretend that everything is in order when it is obviously not, then the results will be very deplorable.

How to tell your child about his diagnosis and teach him how to stand up for himself

How to tell a child about his diagnosis of autism

How to help a child with autism recognize their strengths and weaknesses

Notes of an autist. You must tell your children that they have autism

You must tell your children that they have autism

We hope you find the information on our website useful or interesting. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

Parenting children with autism

How can I tell my child about his autism diagnosis?

07/14/13

A difficult issue for parents, but such information may be necessary for successful growing up with autism

Author: Marsi Wiler / Marci Wheeler

Source: Indiana Resource Centism

9000

9000

Who, what, when, where, how and why are important questions parents ask when making decisions that affect their children's lives. Discussing a diagnosis of autism or Asperger's with your child is a very important decision about which parents can seek guidance. This short article will look at various aspects of explaining to a child his or her diagnosis, and resources that can help and guide you.

Why talk?

“Why tell a child about his diagnosis of autism at all?” This is probably the first question parents ask themselves. After diagnosing a child, parents experience a range of emotions, and it is hoped that they find support in correct information about the condition of their child.

Sometimes siblings, grandparents, and other family members go through a variety of emotions and stages when faced with a family member being diagnosed with autism. Isn't it reasonable to think that the child himself should receive information about his diagnosis and receive support to cope with this new information? All children deserve respect and understanding. Successful people sooner or later found out who they were, accepted it and used this information to achieve the greatest results in life. Don't children with autism deserve a chance to understand and accept themselves by being informed about their disability?

Parents may fear the various consequences of informing children (and sometimes others) about a child's disability in this way. For example, they may be afraid that the child will not understand their diagnosis, that the child will lose life opportunities, that the child will become angry or depressed about their disability, that the child (or other people) will use the disability as an excuse for not can do something, or even that the child will begin to consider himself (or other people will think so) flawed, with no hope for the future. These problems will not necessarily appear, but they can be dealt with as they come.

For example, they may be afraid that the child will not understand their diagnosis, that the child will lose life opportunities, that the child will become angry or depressed about their disability, that the child (or other people) will use the disability as an excuse for not can do something, or even that the child will begin to consider himself (or other people will think so) flawed, with no hope for the future. These problems will not necessarily appear, but they can be dealt with as they come.

Most of these problems, and not only them, can occur even if the diagnosis is hidden from the child and others. Wouldn't it be good to share information about autism or Asperger's syndrome with all concerned, including the child, since it is a diagnosis that affects every aspect of a child's life without exception?

In fact, the likelihood of problems is even higher when a person is not told about his disability and is not provided with the necessary support. Think of the stories many adults with autism spectrum disorder tell who weren't told about their diagnosis or who didn't get the correct diagnosis until adulthood. Lack of understanding of other people and social situations leads to problems in communicating with others, constant ridicule and isolation. When you are constantly told: “You must understand this” or “Stop acting like an idiot”, and you have no idea what you did wrong and how to “fix” the situation, then you begin to constantly experience irritation and confusion.

Lack of understanding of other people and social situations leads to problems in communicating with others, constant ridicule and isolation. When you are constantly told: “You must understand this” or “Stop acting like an idiot”, and you have no idea what you did wrong and how to “fix” the situation, then you begin to constantly experience irritation and confusion.

Many adults report that they perceived themselves as failures and a huge disappointment to their family and others, but could not figure out why they were failing or how they could behave differently. Over time, this leads to low self-esteem and problems with self-acceptance, among other difficulties. Many such people believe that if they received the correct information about their diagnosis and differences from others in a timely manner, then they would have a better chance of a successful life.

Your child may already know that he is different from other people, but like all children at certain stages of development, he may come to false conclusions about his differences. Some children even begin to think that they have a terminal illness and that they will soon die. After all, they go to doctors and other specialists, receive some kind of treatment, but no one explains to them why. A child or adult who never asks questions or verbally expresses their concerns may still have such thoughts. Even children with autism spectrum disorders, like all children, can feel the tension and confusion of adults, and they can come to the wrong conclusions about the reasons for such behavior.

Some children even begin to think that they have a terminal illness and that they will soon die. After all, they go to doctors and other specialists, receive some kind of treatment, but no one explains to them why. A child or adult who never asks questions or verbally expresses their concerns may still have such thoughts. Even children with autism spectrum disorders, like all children, can feel the tension and confusion of adults, and they can come to the wrong conclusions about the reasons for such behavior.

If the child is younger than 18, it is up to the parents to decide whether to tell them about the diagnosis. It may seem that this is a very difficult task, especially when everyday worries absorb all the time and energy of the family. It may be helpful to discuss your concerns and options with someone who knows the child well, other parents of children with autism, or even adults with autism who have been told about their diagnosis.

When to speak?

There is no exact age or time to tell a child about his or her diagnosis. The child's personality, abilities, and social understanding all need to be taken into account to determine when a child may be ready to receive information about their diagnosis. If you start too early, it can cause confusion in the child. If too late, the child may become overly sensitive to the idea that he is different from other people. You can watch for possible signs that the child is ready for this information. Some children directly ask questions: “What is wrong with me?”, “Why can’t I be like everyone else?”, “Why can’t I _______?” or even "What's wrong with everyone around?" Such questions are an unequivocal indication for some information about your diagnosis. However, some children think about it but find it difficult to put these questions into words.

The child's personality, abilities, and social understanding all need to be taken into account to determine when a child may be ready to receive information about their diagnosis. If you start too early, it can cause confusion in the child. If too late, the child may become overly sensitive to the idea that he is different from other people. You can watch for possible signs that the child is ready for this information. Some children directly ask questions: “What is wrong with me?”, “Why can’t I be like everyone else?”, “Why can’t I _______?” or even "What's wrong with everyone around?" Such questions are an unequivocal indication for some information about your diagnosis. However, some children think about it but find it difficult to put these questions into words.

Some children are not diagnosed until adolescence or later. Often those who are diagnosed late already have negative experiences that may have influenced their decision when to share information about their diagnosis. They may be emotionally unprepared to deal with new information due to the burden of negative experiences and their impact on their self-esteem and self-confidence. They can be very sensitive to any hint that they are not like everyone else. On the other hand, older children may already be aware of their old diagnoses - attention deficit disorder, behavioral disorders and/or emotional disorders of some type. Experience with a different diagnosis or definition can help communicate the new diagnosis and provide specific information about their disability.

They may be emotionally unprepared to deal with new information due to the burden of negative experiences and their impact on their self-esteem and self-confidence. They can be very sensitive to any hint that they are not like everyone else. On the other hand, older children may already be aware of their old diagnoses - attention deficit disorder, behavioral disorders and/or emotional disorders of some type. Experience with a different diagnosis or definition can help communicate the new diagnosis and provide specific information about their disability.

Many families have found that a good starting point for talking about a diagnosis is a positive discussion about the uniqueness of each family member. A positive attitude towards differences can be indicated as early as possible, long before the diagnosis is mentioned. Each person is unique, with their own likes and dislikes, strengths and weaknesses, and physical characteristics. Differences between people can be discussed in everyday conversations once the child is able to understand simple and concrete examples of differences. With this approach, it is more likely that the differences between people, whatever they may be, will be perceived as something neutral and even interesting. Neutral comments such as "Mom wears glasses and Dad doesn't wear glasses", "Bobby likes to play ball and you like to read books" are good examples. Constant positive and specific examples of differences between people around you will make it easier to talk about the differences in the child himself in connection with his diagnosis.

With this approach, it is more likely that the differences between people, whatever they may be, will be perceived as something neutral and even interesting. Neutral comments such as "Mom wears glasses and Dad doesn't wear glasses", "Bobby likes to play ball and you like to read books" are good examples. Constant positive and specific examples of differences between people around you will make it easier to talk about the differences in the child himself in connection with his diagnosis.

Many adults with autism believe that children need to be given information before they accidentally hear it from strangers. The child may feel that other people don't like him and/or are always in trouble, but he doesn't understand why. So it is better not to wait for the appearance of a negative experience in order to share information with the child.

What and how to say?

Autism spectrum disorders are complex. Each person with this diagnosis is unique. It is very important that the process of explaining the diagnosis to the child is individual and meaningful specifically for him. The child should not be given too much information. It can be difficult to decide what information to start with. If the child asks questions, then it is better to start with them. First, make sure the child understands what is being asked. Remember that it is very easy to misunderstand the meaning of their words.

The child should not be given too much information. It can be difficult to decide what information to start with. If the child asks questions, then it is better to start with them. First, make sure the child understands what is being asked. Remember that it is very easy to misunderstand the meaning of their words.

Be aware of your child's ability to process information and try to decide what to say and how. For those children who have a pronounced interest in their diagnosis and for children with good reading skills, there are now several books written by other children with autism that may be of interest to them (Hall, 2001; Jackson, 2003).

More books written by adults with autism. Some of these books are only for those interested in autism, but some are for other people with autism. An author with autism can share his experience, give useful advice, help the reader feel that he is not alone in his life journey (Gerland, 2000; Newport, 2001; Willey, 1999; Lawson, 2003).

Most children need only minimal information at first. Over time, you can add new information. Try to keep a positive attitude. Your positive attitude and the way you talk about this topic is extremely important. To make your conversation with your child meaningful, you can start by answering his questions. Perhaps you should write down the most important information and explain to him that other people with this diagnosis have the same questions and experiences. You can then ask if he needs more information from books, videos, and/or conversations with other people. If the child is likely to answer “no” to a question about additional information, then you can not ask it, but simply say that you will be looking for additional information and that you would like to share it. Let the child know that he can always ask you a question as soon as he appears.

Very often, when people with autism have the opportunity to meet other people with the same diagnosis, it becomes a revelation and a very valuable experience for them. People with autism may find it easier to understand themselves and the world by interacting with other people with autism. Connecting with other people on the autism spectrum can help a person understand that there are other people who perceive the world in the same way, and that they are not alone.

People with autism may find it easier to understand themselves and the world by interacting with other people with autism. Connecting with other people on the autism spectrum can help a person understand that there are other people who perceive the world in the same way, and that they are not alone.

There are various possibilities for such communication. There are summer camps that offer special programs for children on the autism spectrum. MAAP holds an annual conference and publishes a newsletter that publishes letters, poems and other texts from people with autism of all ages. There are mailing lists for people with this diagnosis on the Internet, some of them are supported by people with autism spectrum disorders. Carol Gray created a pen pal project that allows students with autism to connect with each other. Each of us knows this desire to find people with whom you have a lot in common, especially if you have lived in a foreign country for a long time! Think about it.

Who should report the diagnosis and where?

Circumstances may vary from family to family. If your child asks questions, don't put off answering them. You have to be open, don't offer to talk about it later. The lack of an answer can increase the child's anxiety, and the topic will become even more mysterious.

If your child asks questions, don't put off answering them. You have to be open, don't offer to talk about it later. The lack of an answer can increase the child's anxiety, and the topic will become even more mysterious.

For some families, the best approach is to enlist the help of a knowledgeable professional to disclose the diagnosis instead of a family member or friend. Involvement of a specialist, at least in the early stages of disclosure of the diagnosis, leaves the child's family and others close to the role of a source of support and comfort. Some people with autism may find it very difficult to seek solace from someone who has given them bad or confusing news. The role of the specialist should be to discuss with the child information about the diagnosis and how this disability affects his life. This will make it easier for the family to support the child. A professional who talks to the child about their disability can also help parents understand the child's reactions and offer advice on how best to support the child. Engaging a specialist also allows the disclosure process to begin outside the home.

Engaging a specialist also allows the disclosure process to begin outside the home.

The diagnosis of autism cannot be explained in one or two meetings. A person needs time to get used to new information about himself at the optimal speed for him. The entire process of disclosing a diagnosis can take weeks or months before the child starts commenting or asking questions about new information. The process of explaining the diagnosis is ongoing. It is important to provide information that is important from the child's point of view, and this will greatly improve the learning process. A positive attitude will help maintain the child's self-esteem and create an effective learning environment. There are materials for this learning process, and hopefully there are people around you who know your child and who can support him and you along the way. So, isn't it time for you to get started?

Ref.

Faherty, C. (2000). What does it mean to be me? A workbook explaining self-awareness and life lessons to the child or youth with high-functioning autism or Aspergers. Arlington, TX: Future Horizons, Inc.

Arlington, TX: Future Horizons, Inc.

Gerland, G. (2000). Finding out about Asperger Syndrome, high functioning autism and PDD. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, Ltd.

Gray, C. (1996). pictures of me. Jenison, MI: Jenison Public Schools. (www.thegraycenter.org)

Hall, K. (2001). Asperger Syndrome, the universe and everything. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kinsley Publishers Ltd.

Jackson, L. (2003). Freaks, geeks and Asperger Syndrome: A user guide to adolescence. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers Ltd.

Lawson, W. (2003). Build your own life: A self-help guide for individuals with Asperger syndrome. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers Ltd.

Newport, J. (2001). Your life is not a label. Arlington, TX: Future Horizons, Inc.

Vermeulen, P. (2000). I am special: Introducing children and young people to their autistic spectrum disorder. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers Ltd.

Vicker, B.