How to teach a child with autism spectrum disorder

10 Effective Tips for Teaching Children With Autism in 2022

Feb 03 2021

Positive Action Staff

•

Special Education

“It’s impossible to handle her.”

“He’s totally disruptive and creates a ruckus in my class.”

“What an attention seeker!”

“Do you think she should be attending regular school?”

“He can’t sit still, even for a moment.”

“I don’t think he’s capable of learning.”

These are some of the commonly heard frustrations that come with teaching students with autism.

But what if we tried to understand how the student with autism feels? What if we attributed their behavior to a different brain wiring instead of deliberate disruption?

Not abnormal or dysfunctional – just different.

This better explains their hyperactivity, anxiety, and inability to connect with other children. These behaviors are a cry for help — your help.

At Positive Action, our committee partners with educators by providing schools with the right tools to develop special ed curriculums catered to students with autism.

“What I love most about Positive Action is the way it pertains to the real issues students face in today's world!” — Lori Kessinge, 5th Grade Teacher, Critzer Elementary School, Virginia

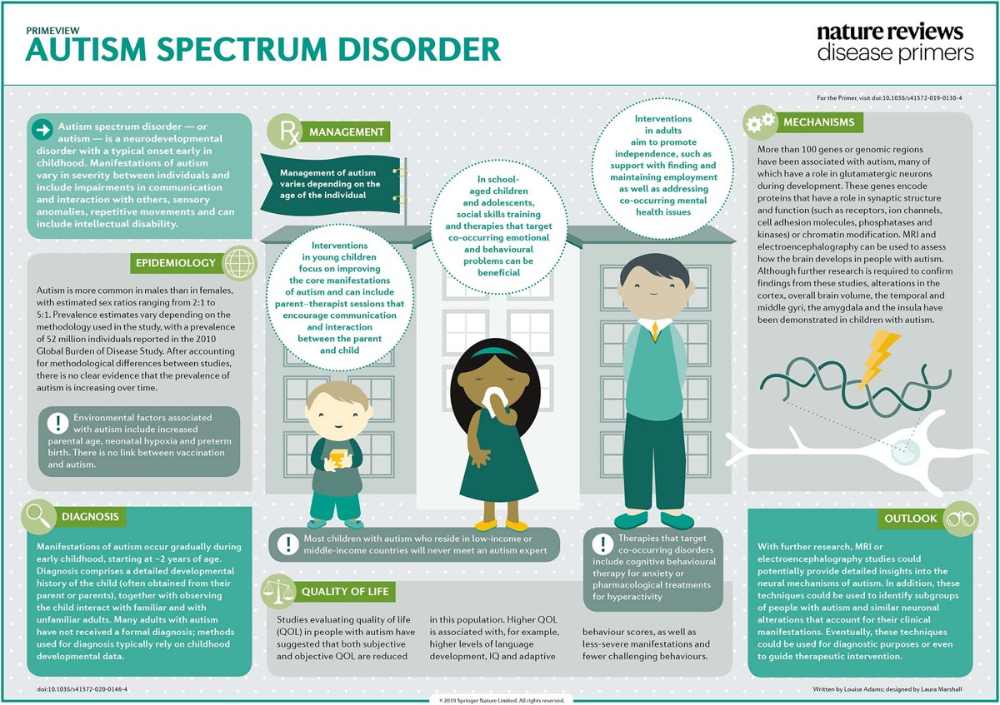

What Is Autism Spectrum Disorder?

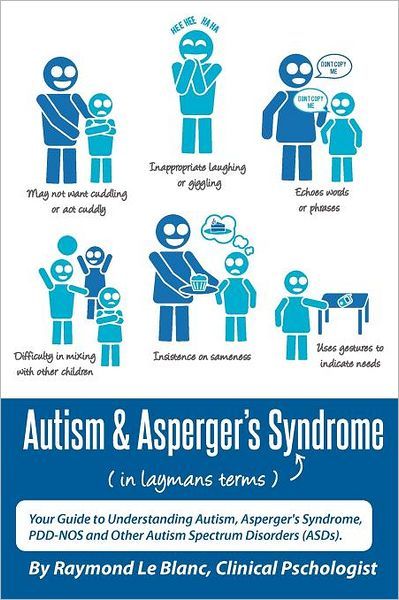

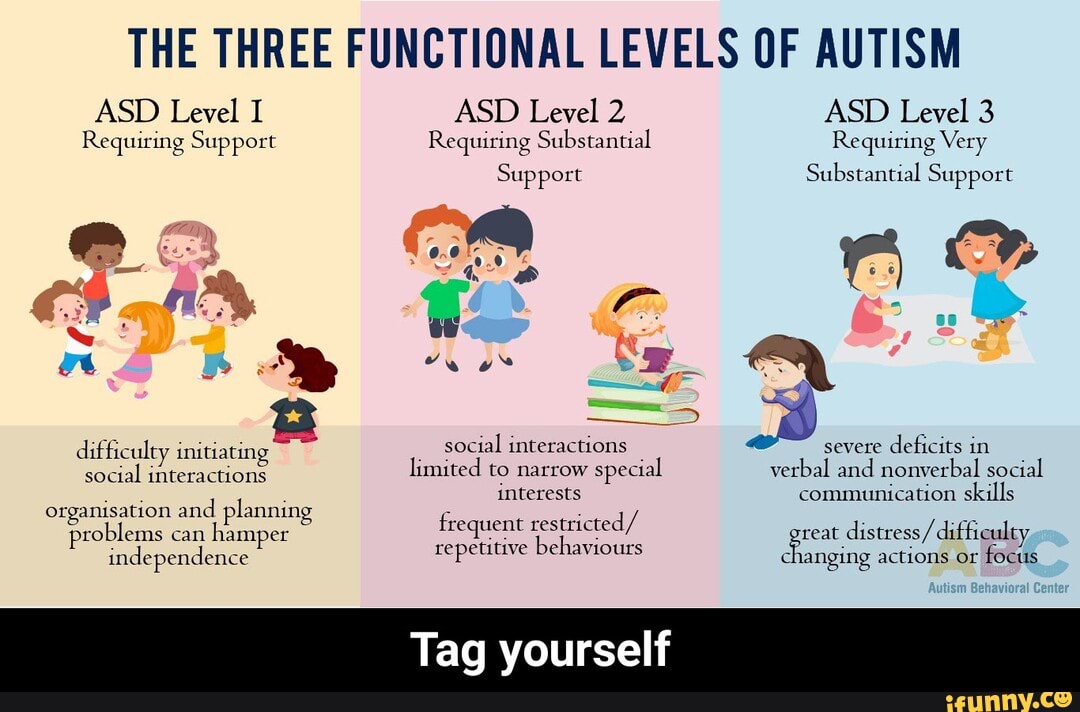

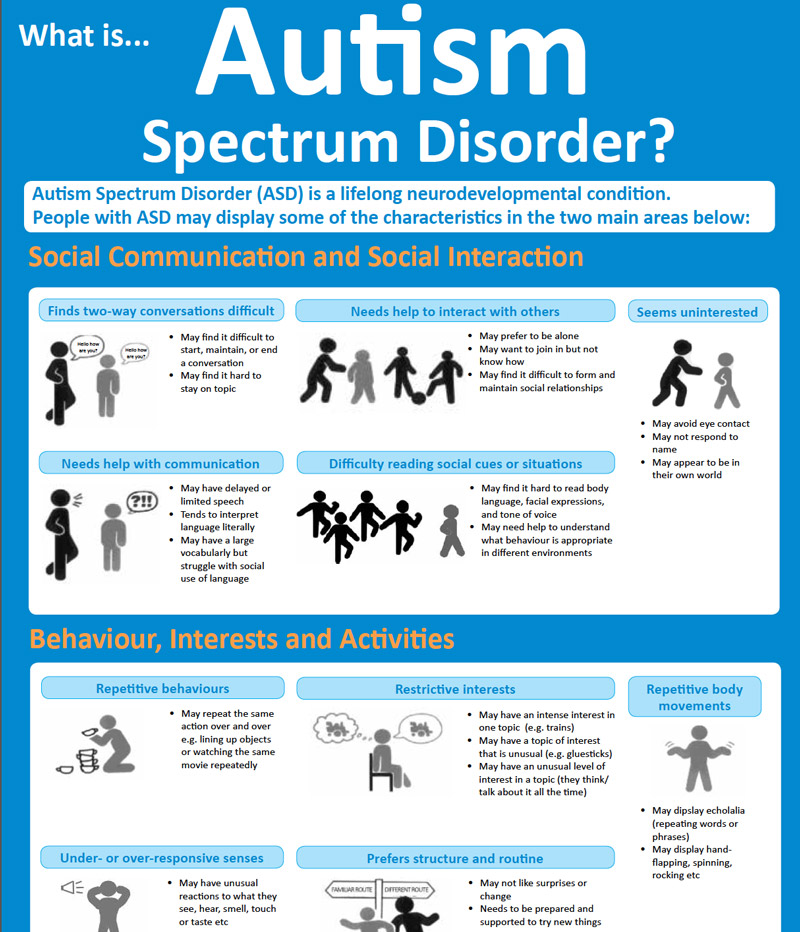

ASD is a child developmental disorder that causes significant challenges in social skills, communication, and behavior in young children — and lasts into adulthood.

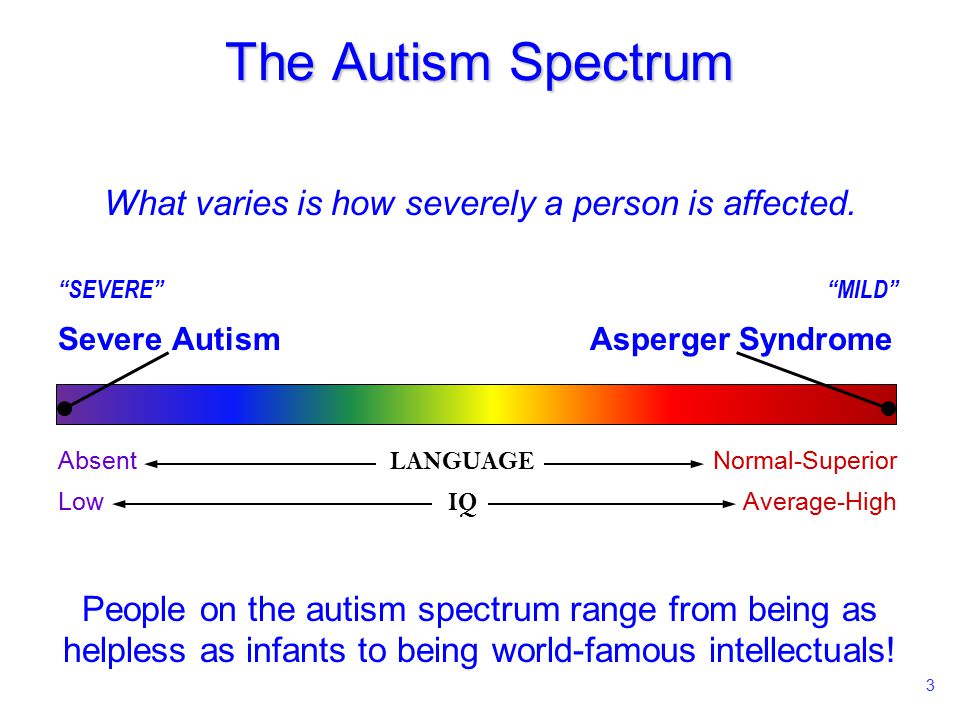

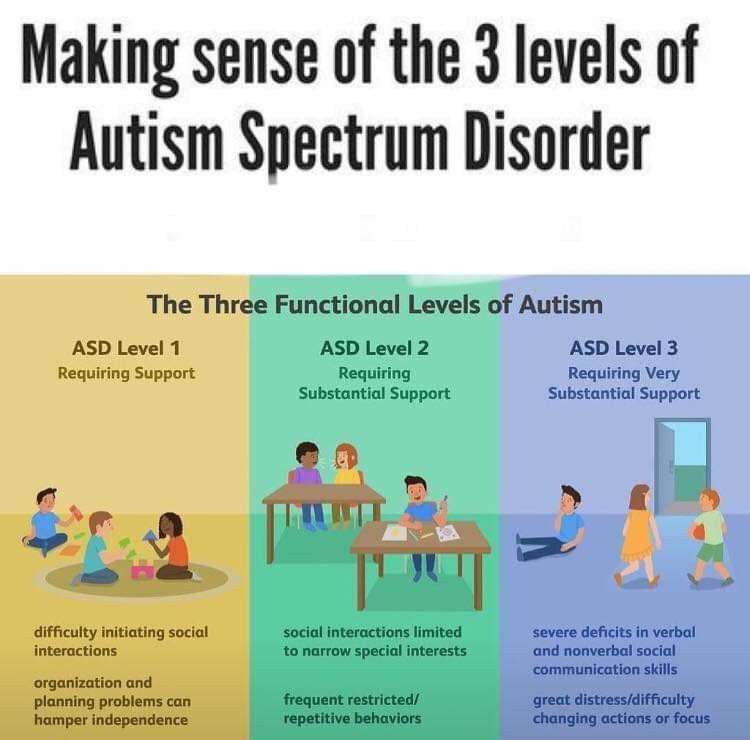

The learning, thinking, and problem-solving abilities of students with autism can range from gifted to severely challenged. Thus, some require more help in their daily lives while others need less.

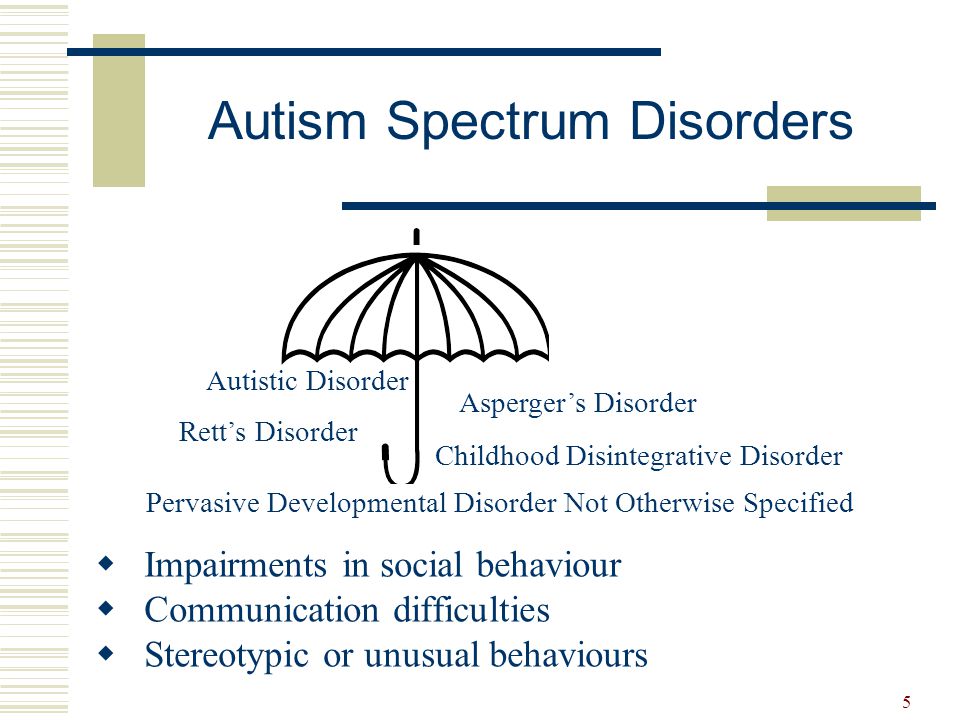

An ASD diagnosis now includes several conditions that used to be diagnosed separately:

These conditions are now collectively referred to as autism spectrum disorder.

Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorders

Students with autism have a wide range of abilities and characteristics — no two children appear or behave the same way. Symptoms can range from mild to severe and often change over time.

Characteristics of ASD fall into two categories:

Social Interaction and Communication Problems

-

Challenges with normal back-and-forth conversation

-

Decreased desire to share personal interests or emotions

-

Difficulty understanding or responding to social cues like eye contact and facial expressions

-

Challenges in developing/maintaining/understanding relationships (trouble building friendships)

Restricted and Repetitive Patterns of Behaviors, Interests, or Activities

-

Hand-flapping and toe-walking

-

Speaking in a unique way — using odd patterns or pitches in speaking or “scripting” from favorite shows

-

Exhibiting intense interest in activities that are uncommon for a similarly aged child

-

Expressing their sensual responses uncommonly or extremely, like indifference to pain/temperature

-

Excessive smelling/touching of objects

-

Fascination with lights and movement and being overwhelmed with loud noises

The truth is, while many children with autism have normal intelligence levels, many others have mild or significant intellectual delays.

This is where the right educators play a huge role in teaching students with ASD.

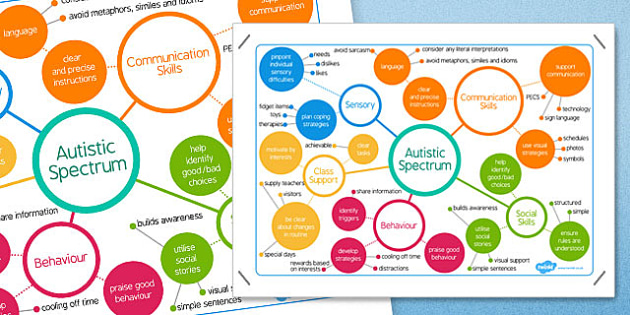

How Do You Teach Students With Autism Spectrum?

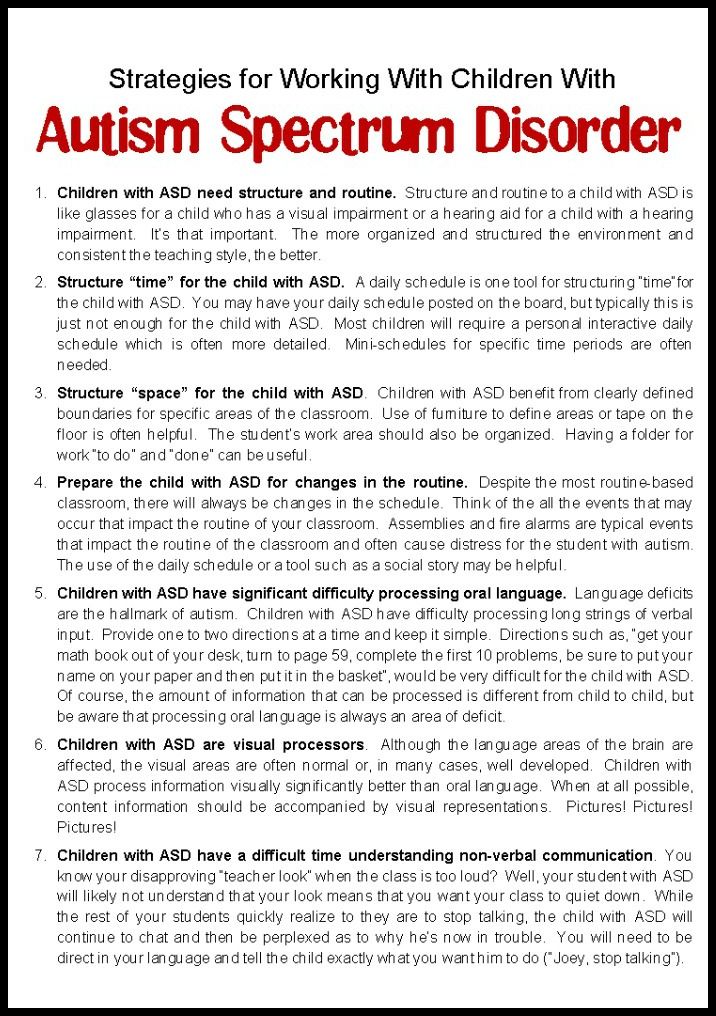

The number of students with autism is on the rise. So a deep understanding of the strategies and social skills needed to handle a class of autistic children is extremely important.

Listed are some tried and true strategies that will ensure every autistic child receives the best education possible.

These strategies apply to both the classroom and home environments.

-

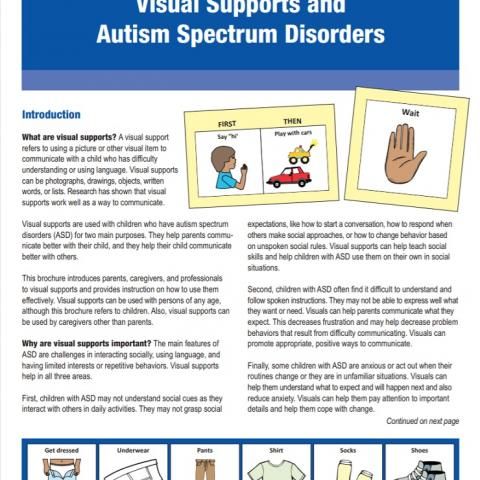

Structure or routine is the name of the game when it comes to autism. Maintain the same daily routine, only making exceptions for special occasions. During such moments, place a distinct picture that depicts the day’s events in the child's personal planner.

-

Design an environment free of stimulating factors:

a. Avoid playing loud background music as it makes it difficult for the autistic child to concentrate.

b. Eliminate stress because autistic children quickly pick up on negative emotions. So for example, if you’re experiencing too much stress, leave the classroom until you feel better.

c. Maintain a low and clear voice when engaging the class. Students with autism get easily agitated and confused if a speaking voice is too loud.

d. Some autistic people find fluorescent lights distracting because they can see the flicker of the 60-cycle electricity. To mitigate this effect:

-

Place the child's desk near the window or try to avoid using fluorescent lights altogether.

-

If the lights are unavoidable, use the newest bulbs you have as they flicker less.

-

You can also place a lamp with an old-fashioned incandescent light bulb next to the child's desk.

e. Let students stand instead of sitting around a table for a class demonstration or during morning and evening meetings. Many students with autism tend to rock back and forth so standing allows them to repeat those movements while still listening to the teacher.

-

-

Keep verbal instructions short and to the point, because an autistic student may find it difficult to recall the entire sequence. Instead, write the instructions down on a piece of paper.

This seemingly small act matters; take this person with autism for instance:

“I am unable to remember sequences. If I ask for directions at a gas station, I can only remember three steps. Directions with more than three steps have to be written down.”

-

Go for repetitive motions when working on projects. For example, most autistic classrooms have an area for workbox tasks, such as putting away erasers and pencils. This kind of predictability helps autistic kids stay organized.

-

Use signs, pictures, and demonstrations for visual learners. For example:

a. When teaching up and down movements, attach cards with the words "up" and "down" to a toy airplane. The "up" card is attached when the plane takes off while the "down" card is attached when it lands.

b. Use a wooden apple cut up into four pieces and a wooden pear cut in half to help students with autism understand the concept of quarters and halves.

“I think in pictures. I do not think in language. All my thoughts are like videotapes running in my imagination. Pictures are my first language.”

-

Many autistic children hyperfocus on one subject like trains or maps so use that specific interest to motivate school work. With a child who likes trains, for instance, calculate how long it takes for a train to go between New York and Washington. And there you have it, you’ve just solved a math problem.

-

The fewer the choices, the easier decision-making is for an autistic kid. For instance, if you ask a student to pick a color, limit them to three choices.

-

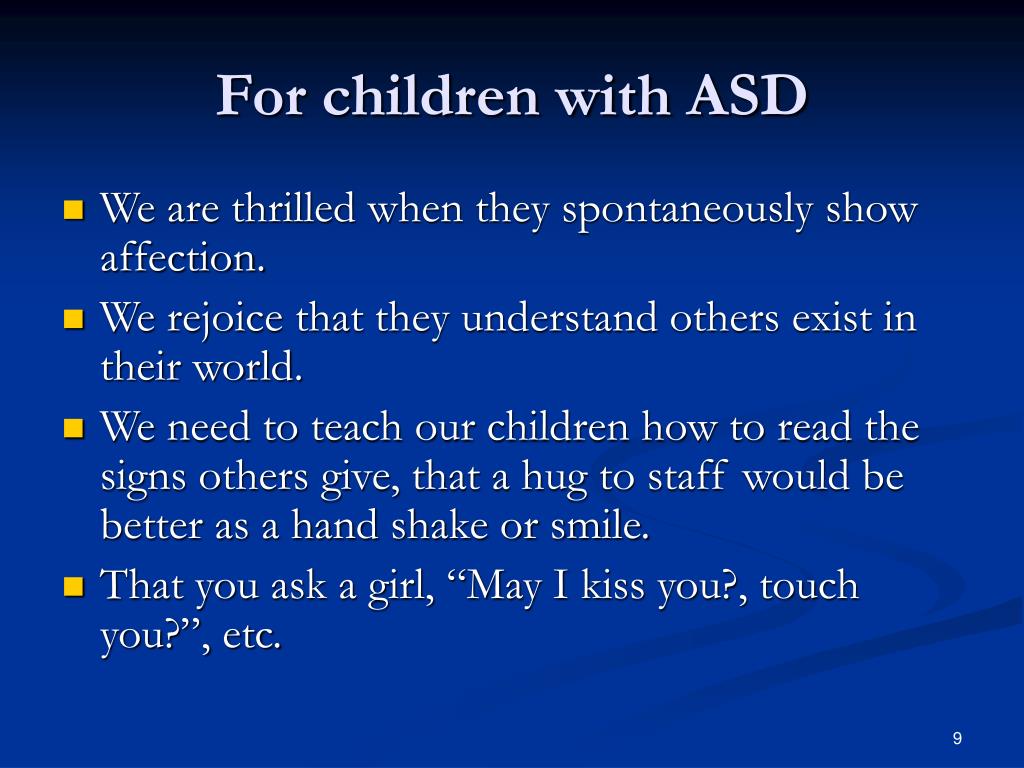

Create a few structured one-on-one interactions between students to promote their social skills. Take note that autistic children can’t accurately interpret body language and touch, so minimal physical contact is best.

-

Parents and caregivers are the true experts on their autistic children. Therefore, to fully support the child in and out of school, teachers should coordinate and share knowledge with them. For example, you can exchange notes on interventions that have worked at home and in school then integrate accordingly.

-

Lastly, we can’t forget you, dear teacher. Even when you’re doing everything right, teaching students with autism can still be tough, so building resilience is important.

Here are some statements you can recite on difficult days:

-

“Building a relationship with autistic children doesn’t happen overnight — it takes time, dedication, and patience.”

-

“Every mistake I make is valuable feedback for figuring out what works.”

-

“I won’t always get things right off the bat and, ultimately, autistic children are still children, who can be a handful even at the best of times.

”

” -

“Autistic children aren’t difficult on purpose. They’re simply doing the best they can with their worldview and available support.”

-

“Good teachers helped me to achieve success. I was able to overcome autism because I had good teachers. At age 2 1/2 I was placed in a structured nursery school with experienced teachers. Children with autism need to have a structured day and teachers who know how to be firm but gentle.”

Rise to the Challenge

Positive Action recognizes the value of each and every person. We help special needs students integrate into mainstream classrooms while equipping them with the essential skills and motivation to thrive.

Positive Action can help you assess your special education students’ needs and plan how to meet them with Individualized Education Plans.

“I am very grateful for these lessons. They fulfill a need that so many children are lacking in the educational process today. ” — Linda Davis, 2nd Grade Teacher, Davis Elementary

” — Linda Davis, 2nd Grade Teacher, Davis Elementary

If you want to see how Positive Action can increase educational success at your institution or organization contact us by phone, chat, or email or schedule a webinar with us below.

Teaching Students With Autism Spectrum Disorder: Tips, Resources, and Information On Supporting Students with Autism

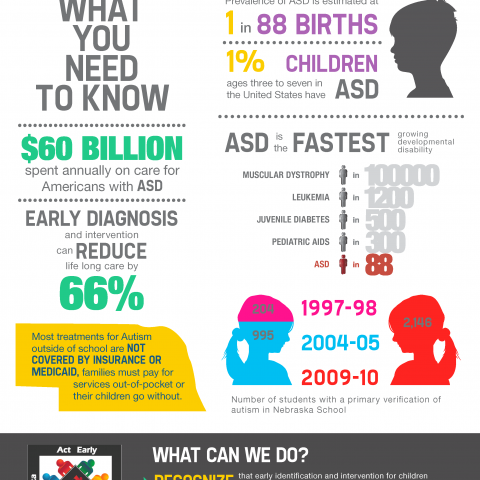

Even if you don’t have a child with autism in your class this year, you will probably teach one at some point. Autism is seen in around 1 in 59 children, a figure that has risen as clinicians have gotten better at recognizing autistic symptoms.[1] Supporting children with autism can make a world of difference in their lives, which is why it’s important for educators to accommodate these students as needed.

Want to better understand and support students with autism at your school? Read on to learn more about what autism is, which challenges students with autism face, and a few tips and lesson ideas for helping them make the most with their education.

What is Autism Spectrum Disorder?

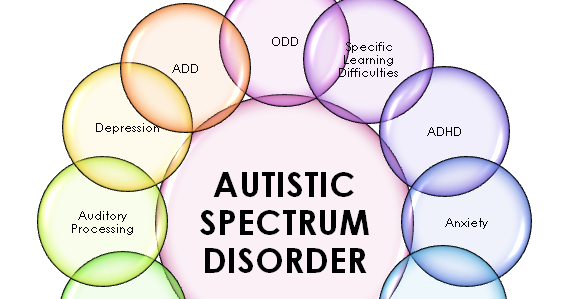

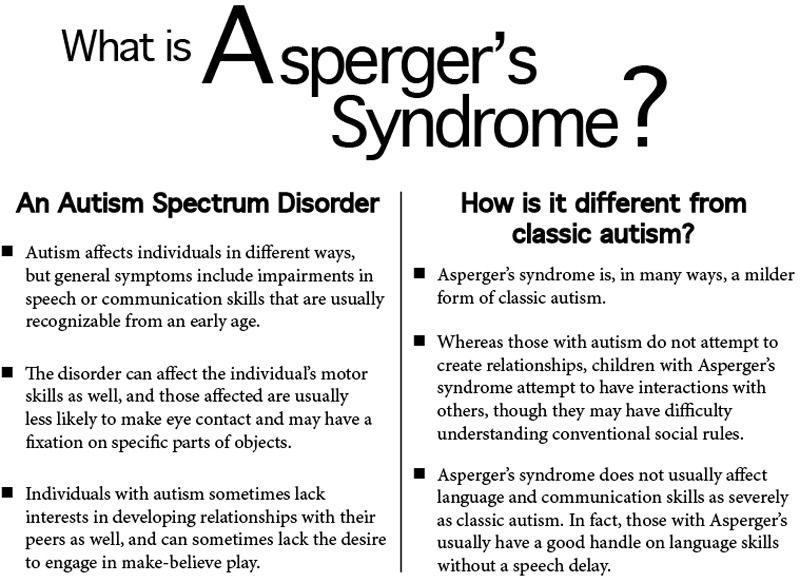

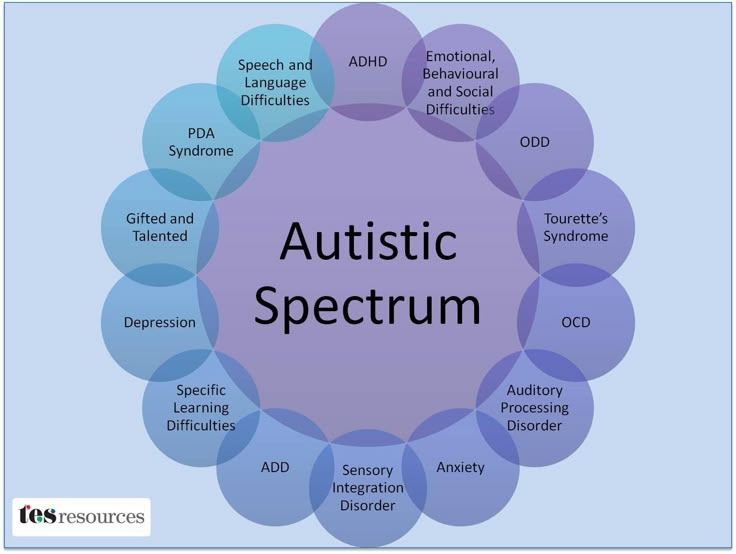

The definition of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition that causes children to be hypersensitive to sensory stimuli. We use the term “spectrum disorder” because characteristics of autism vary depending on the child and can range from mild to severe.[2] That being said, students with autism often have trouble communicating with others and exhibit repetitive behavior.

A few common signs of autism spectrum disorder include: [3]

- Has trouble talking or making eye contact

- Seems to prefer playing alone and is often “in their own world”

- Shows unusual attachments to certain objects or activities

- Struggles in social interactions with other students

- Appears overly sensitive to noises or images

While it’s not certain what causes autism in children, the strongest factor seems to be genetics. A study involving forty-three pairs of twins found that genes can highly predict a person’s likelihood of having autism. [4] While some environmental factors seem to increase the chance that a child develops autism, one thing is certain–researchers have not found evidence that vaccines are one of these factors.[5]

[4] While some environmental factors seem to increase the chance that a child develops autism, one thing is certain–researchers have not found evidence that vaccines are one of these factors.[5]

When working with students with autism, schedule a meeting with the child’s parents or a school specialist at the beginning of the year. That way, you can get a sense of your student’s personal needs and how you can best help. Try not to assume which symptoms a child has or try to self-diagnose a student with autism. When in doubt, the best person to discuss any questions with is always their parent or guardian.

What Challenges Do Students with ASD Experience in School?

While teachers often ask if autism is a learning disability, the answer isn’t as straightforward as you’d think. Autism itself isn’t a learning disability, but there are some learning difficulties associated with autism. For example, students diagnosed with autism are more likely to develop attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and dyslexia. [6] When teaching students with ASD, it’s helpful to watch for symptoms of learning disorders and refer them to a specialist if needed.

[6] When teaching students with ASD, it’s helpful to watch for symptoms of learning disorders and refer them to a specialist if needed.

Children with autism are also more likely to develop emotional disorders due to the unique challenges they face. Without support in the classroom, these students are more likely to feel isolated or misunderstood. At least one in three people with autism with develop mental health issues like depression or anxiety in their lives.[7] And since the risk of self-harm behaviors is 28 times more likely for children with autism, making sure your students receive the emotional support they need is essential.[8]

Another issue many students with autism face is bullying. Around 34% of children with autism report being picked on at school to the point that it distresses them.[9] Because these kids may think or act differently from others, other students may tease them or leave them out of their friend circles. That’s why it’s important to educate all children in your school about autism, not just the student with ASD.

If these issues aren’t resolved early on, they can affect students on the autism spectrum through their entire educational career. Children with autism are less likely to pursue employment or college after high school, in part because of these difficulties.[10] Luckily, teaching students with autism strategies to overcome their personal challenges can help them reach their potential.

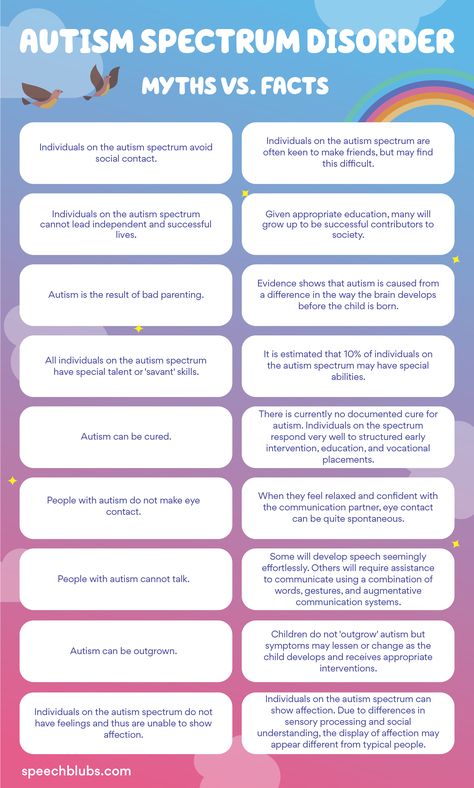

Why Autism Awareness Month? Dispelling Myths About Autism

Every year in April, we celebrate Autism Awareness Month to shed light on misconceptions about autism and help students with ASD find the support they need. Here are a few myths along with the real facts to help you understand more about your students with autism.

“All children with autism have intellectual disabilities.”

Because autism is a spectrum disorder, it comes in a broad range of symptoms and severity.[11] In terms of how autism affects learning in school, some students may have cognitive disabilities while others might not. The best way to know for sure is to discuss their symptoms with their parents or a school specialist.

The best way to know for sure is to discuss their symptoms with their parents or a school specialist.

“Only boys can develop autism. Girls with autism are rare or nonexistent.”

While it’s true that boys are more likely to develop autism, girls can have this condition, too. The ratio of boys to girls with autism is estimated at around 3:1, but girls with ASD are less likely to be formally diagnosed.[12] Some researchers have theorized that autism symptoms can be different in men and women, causing girls with ASD to be misdiagnosed or underreported.[13]

“Students with autism cannot make friends or feel emotions.”

Children with autism feel emotions just like everybody else, even if they show it in different ways.[14] Most students with autism want friends, but if they struggle with social skills, they might not know how.

Luckily, teaching students with autism key social skills can help them bond with their classmates. If a child has trouble fitting in, try playing autism awareness activities or teaching a lesson about diversity with your whole class to help all of your students feel welcome.

“Autism can be cured.”

Since autism is a neurological disorder, symptoms can be alleviated but not “cured” entirely. But while children with autism might struggle with some things, they’re just as capable of growth as other students. Finding activities and learning strategies that address their challenges can help them turn their weaknesses into strengths.

“Children with autism will never achieve as much as their peers.”

Students with autism have so much potential, and some of the brightest minds in the world have been people with autism spectrum disorder, including:

- Charles Darwin

- Emily Dickinson

- Michelangelo

- Temple Grandin

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Beloved poets, talented musicians and artists, and scientists who shaped how we see the world today have been included on lists of famous people with autism. Our communities would not be the same without people on the autism spectrum. While students with autism may have different weaknesses than their classmates, they often have plenty of strengths, too.

Fun Classroom Activities for Teaching Students with Autism

Sometimes, educational strategies for autism may differ from the lesson plans you make for the rest of your class. But thankfully, autism activities can be as simple as stocking sensory toys in your classroom or reading picture books about social skills. Use these four activities for students with autism to help these students learn academic concepts.

Sensory Activities

Because children with autism are sensitive to sensory input, activities that involve their five senses can help ground them in the present.[15] If a child with ASD is having a hard time focus in class, try giving them a special sensory toy to play with. If possible, try to work the sensory item into their assignment.

Here are a few examples of sensory items you could use to help with autism symptoms:

- Stress ball

- Finger paint

- Clay or play-dough

- Fidget toys

- Chewing gum

Exercise Games

Studies show that regular exercise can help alleviate symptoms of autism and improve social skills. [16] Try planning outdoor activities that get your students moving and tie into your lesson plans. You could, for example, play hopscotch to teach kindergarteners how to count or plan a kickball game as a class reward. Once your students come back inside, everyone will have gotten their wiggles out and be ready to work.

[16] Try planning outdoor activities that get your students moving and tie into your lesson plans. You could, for example, play hopscotch to teach kindergarteners how to count or plan a kickball game as a class reward. Once your students come back inside, everyone will have gotten their wiggles out and be ready to work.

SEL Picture Books

Stories are a great method for teaching children with autism important social emotional learning (SEL) skills. You can read SEL picture books as a class or assign them to your student as independent reading.

Here are a few books about social-emotional skills you can read to your student with autism:

- No, David! by David Shannon

- Last Stop on Market Street by Matt de la Peña

- The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein

- A Sick Day for Amos McGee by Philip and Erin Stead

- Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No-Good, Very Bad Day by Judith Viorst

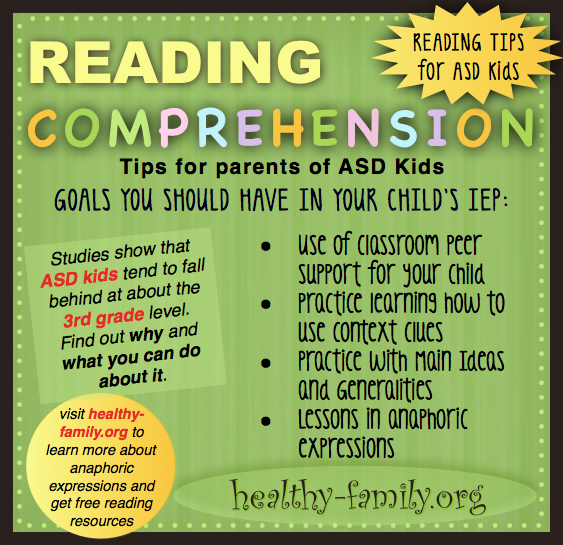

Reading Time

Since school can involve so much sensory stimulation, a full day of class can leave students with ASD feeling overwhelmed. Children with autism benefit from quiet breaks throughout the day, so try planning a quiet reading activity as a class to give everyone time to de-stress and work independently.[17] Or if your student with autism is having trouble focusing, ask them if they’d like to spend some time reading in the school library.

Children with autism benefit from quiet breaks throughout the day, so try planning a quiet reading activity as a class to give everyone time to de-stress and work independently.[17] Or if your student with autism is having trouble focusing, ask them if they’d like to spend some time reading in the school library.

Tips for Working with Children on the Autism Spectrum

The more you know about how to support students with autism, the better prepared these children will be for academic success.

Use these five tips and accommodations for students with autism to make sure every child in your classroom feels welcome and supported:

- Avoid sensory overload in classroom decorations or activities, which can make it tough for students with autism to pay attention [18]

- Many children with autism have difficulties understanding figurative language. If a student misunderstands a simile or idiom that you use, try to teach them what you really mean [19]

- Sometimes, students with autism feel confused by open-ended questions.

When possible, try giving your students options if they don’t seem to understand your question [20]

When possible, try giving your students options if they don’t seem to understand your question [20] - Children with autism often have a special interest in a topic or activity–try using what they’re interested in to teach them. If they’re fascinated with dinosaurs, for example, you could use dinosaur figurines to teach them how to add or subtract

- Don’t assume that a child with autism is intellectually disabled. If you’re not sure how to best support your student, discuss their symptoms with their family or a school psychologist [21]

Sources:

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Data & Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder. Retrieved from cdc.gov: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html.[1]

Iowa Department of Education. Talking to Parents About Autism. Retrieved from educateiowa.gov: http://educateiowa.gov/sites/files/ed/documents/Parent-Factsheets_April2010_Autism.pdf.[2]

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. What are the symptoms of autism? Retrieved from nichd.nih.gov: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/autism/conditioninfo/symptoms.[3]

What are the symptoms of autism? Retrieved from nichd.nih.gov: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/autism/conditioninfo/symptoms.[3]

Baily, A., Couteur, A.L., Gottesman, I., and Bolton, P. Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: evidence from a British twin study. Psychological Medicine, July 2009, 25(1), pp. 63-77.[4]

Landrigan, P.J. What causes autism? Exploring the environmental contribution. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, April 2010, 22(2), pp. 219-25.[5]

Montes, G., and Halterman, J.S. Characteristics of School-Age Children with Autism. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, October 2006, 27(5), pp. 379-85.[6]

National Autistic Society. Autism facts and history. Retrieved from autism.org.uk: https://www.autism.org.uk/about/what-is/myths-facts-stats.aspx.[7]

Mayes, S.D., Gorman, A.A., Hillwig-Garcia, J., and Syed, E. What causes autism? Exploring the environmental contribution. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, january 2013, 7(1), pp. 109-19.[8]

109-19.[8]

National Autistic Society. Autism facts and history. Retrieved from autism.org.uk: https://www.autism.org.uk/about/what-is/myths-facts-stats.aspx.[9]

Ibid.[10]

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. What are the symptoms of autism? Retrieved from nichd.nih.gov: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/autism/conditioninfo/symptoms.[11]

Loomes, R., Hull, L., and Mandy, W.P. What Is the Male-to-Female Ratio in Autism Spectrum Disorder? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, June 2017, 56(6), pp. 466-74.[12]

Bargiela, S., Steward, R., and Mandy, W. The Experiences of Late-diagnosed Women with Autism Spectrum Conditions: An Investigation of the Female Autism Phenotype. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, October 2016, 46(10), pp. 3281-94.[13]

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. What are the symptoms of autism? Retrieved from nichd.nih.gov: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/autism/conditioninfo/symptoms.[14]

What are the symptoms of autism? Retrieved from nichd.nih.gov: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/autism/conditioninfo/symptoms.[14]

Greene, K. Teaching Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Retrieved from scholastic.com: https://www.scholastic.com/teachers/articles/teaching-content/teaching-students-autism-spectrum-disorder/.[15]

Healy, S. The effect of physical activity interventions on youth with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. Periodical from the International Society of Autism Research, 2018, 27(5), pp. 818-33.[16]

Kluth, P. Supporting Students with Autism: 10 Ideas for Inclusive Classrooms. Retrieved from readingrockets.org: http://www.readingrockets.org/article/supporting-students-autism-10-ideas-inclusive-classrooms.[17]

Manolis, L. 6 Tips for Teaching Students with Autism. Retrieved from teachforamerica.org: https://www.teachforamerica.org/stories/6-tips-for-teaching-students-with-autism.[18]

Ibid. [19]

[19]

Kluth, P. Supporting Students with Autism: 10 Ideas for Inclusive Classrooms. Retrieved from readingrockets.org: http://www.readingrockets.org/article/supporting-students-autism-10-ideas-inclusive-classrooms.[20]

Moreno, S., and O’Neal, C. Tips for Teaching High-Functioning People with Autism. Retrieved from iidc.indiana.edu: https://www.iidc.indiana.edu/pages/Tips-for-Teaching-High-Functioning-People-with-Autism.[21]

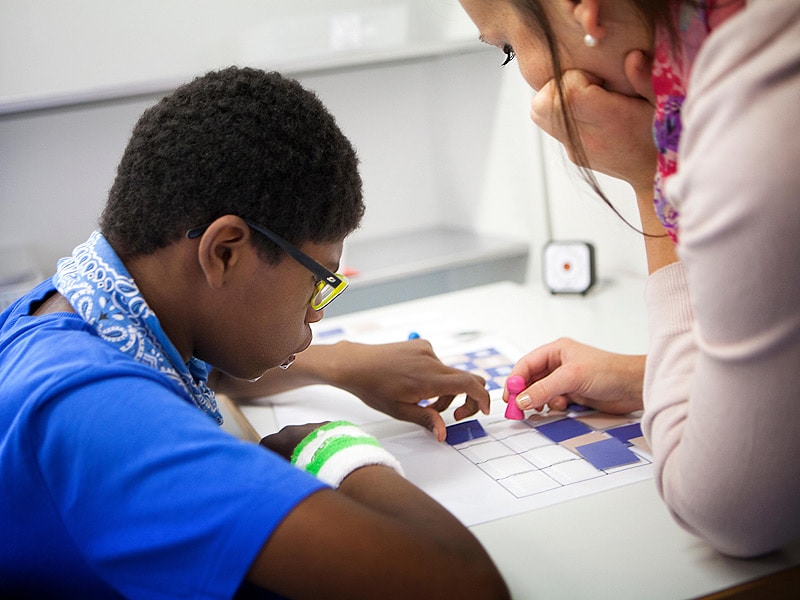

Teaching children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) to read and write using the creation of a "Personal Primer"

Over the years, the Institute of Correctional Pedagogy of the Russian Academy of Education has developed a system for preparing children with autism and other autism spectrum disorders (ASD) for schooling. Mastering reading and writing by creating a "Personal Primer" is a technique that is the result of summarizing the experience of correctional and developmental education of more than twenty autistic children. All children who were involved in the formative experiment were subsequently able to study in a public school and master the general education program. Creating a "Personal Primer" is the initial stage of teaching an autistic child the skills of reading and writing.

All children who were involved in the formative experiment were subsequently able to study in a public school and master the general education program. Creating a "Personal Primer" is the initial stage of teaching an autistic child the skills of reading and writing.

At the same time, we note that classes in preparation for school using this technique can be carried out with autistic children who use speech and have passed the preparatory stage of education, the task of which is to form learning behavior. Thus, for all children with ASD, with the exception of those who lack external, expressive speech (that is, mutic, non-speaking children), classes with the help of the "Personal ABC Book" are necessary and useful - subject to some preparatory work to organize their voluntary attention and behavior.

The optimal age for training using this primer is 5-7 years, but it can be started later if the development of voluntary self-organization skills in the child is delayed.

This primer, like the whole system of preparing an autistic child for school, is based on the idea of his special educational needs. To understand the specifics of literacy classes for an autistic child, it is worth highlighting one of these needs, namely, the development of meaning formation, which we understand as the achievement of a meaningful attitude of the child to the learning process itself, to any information he assimilates, the formation of meaningful skills , which in the future the child will be able to use both at school and, in general, for understanding the world around him.

To understand the specifics of literacy classes for an autistic child, it is worth highlighting one of these needs, namely, the development of meaning formation, which we understand as the achievement of a meaningful attitude of the child to the learning process itself, to any information he assimilates, the formation of meaningful skills , which in the future the child will be able to use both at school and, in general, for understanding the world around him.

Our consulting experience shows that attempts to teach school-relevant skills using traditional methods and techniques or approaches used in working with children with other developmental disabilities are inadequate in relation to children with ASD. In consultations, parents of autistic children told us about typical learning problems:

- the child knows all the letters, plays with them, collects ornaments from the magnetic alphabet, but refuses to make words out of the letters;

- the child knows the letters, but associates each of them with only one specific word;

- the child knows how to put words together from letters or is taught to read by syllables, but does not understand the meaning of what is read, cannot answer a single question;

- the child can read but cannot and categorically refuses to learn to write;

- the child understands the short story he has read, answers questions about the text, but cannot retell it.

These and other characteristic problems inevitably arise when teaching autistic children without taking into account their special educational needs. Failing to achieve the goal, such attempts each time cast doubt on the very possibility of preparing an autistic child for schooling and adapting him to the conditions of a mass school.

The task of developing meaning formation required the use of special educational material filled with personal meaning for the child, the organization of such learning conditions that allow the child to achieve awareness of each educational task, each of his own actions, as well as a complete understanding of each acquired skill . Otherwise, at all intermediate stages of the educational process, there is a danger of emasculating its meaning, turning the newly acquired skill into a stereotypical mechanical game, and the educational material into a means of autostimulation.

Therefore, the logic of pedagogical work in general was set by the principle “from the general to the particular”, or rather, “from meaning to technology”. For example, when teaching reading, this meant that the teacher had to first create in the child an idea of what letters, words, phrases are, fill them with personal, emotional meanings, and only then work out the reading technique. It was difficult to adhere to such logic, but any deviation from it led to the mechanical, thoughtless assimilation of a certain skill by an autistic child, to the impossibility of its meaningful use.

For example, when teaching reading, this meant that the teacher had to first create in the child an idea of what letters, words, phrases are, fill them with personal, emotional meanings, and only then work out the reading technique. It was difficult to adhere to such logic, but any deviation from it led to the mechanical, thoughtless assimilation of a certain skill by an autistic child, to the impossibility of its meaningful use.

In particular, this is precisely why, while studying letters with the child using the “Personal ABC Book”, and creating in him the idea that letters are components of words, the teacher simultaneously used elements of the “global reading” technique, thanks to which words and phrases acquired for the child their meaning, "overgrown" with personal meanings. Only then could one turn to analytical reading without fear that the child would learn to read mechanically.

Thus, the primer, which will be discussed, serves to study letters, to create in the child an idea about the letter, that it acquires meaning in the word. This primer, unlike the traditional one, does not provide for mastering the analytical way of reading. Having mastered such a “primer”, the child knows all the letters and, of course, can involuntarily read individual words, but the teacher does not consciously develop this skill, moreover, does not fix the child’s attention on it in order to first create an idea of the word and phrase.

This primer, unlike the traditional one, does not provide for mastering the analytical way of reading. Having mastered such a “primer”, the child knows all the letters and, of course, can involuntarily read individual words, but the teacher does not consciously develop this skill, moreover, does not fix the child’s attention on it in order to first create an idea of the word and phrase.

Self-acquaintance of an autistic child with letters often occurs even before classes with a teacher. In everyday life, an autistic child, just like an ordinary child, involuntarily pays attention to signs, product names, favorite books, cartoons. When the teacher introduced the children to the letters of the alphabet, some of them already knew the name and spelling of individual letters.

For example, Misha K. (7 years old) already knew “B” before starting the letter lessons. His favorite book "Pinocchio" began with this letter.

Alyosha R. (6.5 years old) wrote the initial letter of his name on a blackboard, in an album, on pieces of paper and showed it to adults.

However, due to the tendency to stereotyping and autostimulation, the autistic child reproduced only a set of letters that was significant for him. He manipulated the "valuable" letters in the game, lined them up in rows, folded patterns. Attempts by an adult to draw the child's attention to learning new letters with the help of a traditional primer often caused anxiety and fear in the child. He could leaf through the primer, look at the pictures, but he refused to learn the letters from it.

Tyoma G. (6.5 years old) picked up the primer bought by his mother and said:

- He's not my friend. - Why? Mom asked. — No about Chip and Dale.

Primer is the first book on the basis of which the prerequisites for meaningful reading are formed. Reading itself becomes interesting later, at first the child's attention is attracted by illustrations. The traditional primer covers a fairly large range of educational topics that are understandable and interesting to an ordinary child (vegetables, fruits, dishes, animals, etc. ). But even with a successful combination of speech and visual material, the primer does not always affect the interests of an autistic child. It is clear that the traditional primer most often has nothing to do with his selective predilections (for example, the life of pirates or robots).

). But even with a successful combination of speech and visual material, the primer does not always affect the interests of an autistic child. It is clear that the traditional primer most often has nothing to do with his selective predilections (for example, the life of pirates or robots).

It was unacceptable to use the stereotyped hobbies of an autistic child in teaching or his interest in letters as abstract signs that could be elements of an ornament or a collection. In this case, we would encourage his tendency to autostimulation, and the child could use the developed reading and writing skills only in line with his “supervaluable interests”, and not for learning about the world around him.

The most true and natural in this situation seemed to us the maximum connection of learning with the child's personal life experience, with himself, his family, the closest people, with what is happening in their life . Experience shows that this is the only way to make the learning of an autistic child meaningful and conscious. Starting with mastering the alphabet, recognizing letters in words, and gradually moving on to reading words and phrases, we necessarily relied on the material of the child’s own life, on what happens to him: everyday activities, holidays, trips, etc. This approach to learning in parallel, he developed a system of emotional meanings for an autistic child, helping him to realize the events of his own life, relationships, feelings of loved ones.

Starting with mastering the alphabet, recognizing letters in words, and gradually moving on to reading words and phrases, we necessarily relied on the material of the child’s own life, on what happens to him: everyday activities, holidays, trips, etc. This approach to learning in parallel, he developed a system of emotional meanings for an autistic child, helping him to realize the events of his own life, relationships, feelings of loved ones.

So, the teacher offered the child to create his own primer. It is clear that the selectivity and stereotyping of interests, an increased level of anxiety and fear of everything new led to the fact that the child could first refuse our offer, say that “he doesn’t need any primer”, that he “doesn’t want to invent anything”, “does not will do nothing." Then the teacher, together with the parents, sought to create positive motivation in the child, to tell him why it is so important to create his own primer, what an interesting and necessary thing it is.

Of course, the child needed to be explained what an ABC book is, why it is needed, why one needs to know the letters. But at the same time, we started from his interests, from what he loves, knows and can do, trying to find the most significant motive. For example, if a child was fond of diagrams, maps, and talked about travel, the teacher could ask: “How can I write a note to my mother that her son went to travel if you don’t know how to write?” or “How do you understand a map if you don’t know what it says?” etc.

In many cases it was possible to rely on the child's expressed cognitive interest, to tell him how much he could learn from books about his favorite insects or about volcanoes. It was important in the end to get a positive answer from the child to the question of whether he wants to learn letters. Then, as homework, the teacher asked the child and her mother to choose and buy an album for letters and bring her photograph. At the lesson, the teacher and the child together pasted the photo into the album, and under it the teacher signed “My primer”.

The creation of the "Personal Primer" assumed a special sequence in the study of letters, aimed at their meaningful assimilation. So, in our practice, the study always began with the letter "I", and not with "A", and the child, together with the adult, pasted his photograph under it.

It is known that with autism a child talks about himself in the second or third person for a long time, does not use personal pronouns in his speech. The study of the first letter “I” and at the same time the word “I” allowed the child to “go away from himself”, instead of the usual “we”, “you”, “he”, “Misha wants”. Creating a primer as a book about himself, in his own name, in the first person, from "I", the child rather comprehended those objects, events, relationships that were significant in his life.

Then the child had to learn that the letter "I" can occur in other words, at the beginning, middle, end of a word. The teacher prompted the child with suitable words, but which of them to leave in the album was a matter of his personal choice.

For example, Nikita V. (7 years old) took a long time to choose objects that had “I” in their names.

- Nikita, what objects will we draw on "I": an apple, a lizard, an egg, a yacht, a box? the teacher asked. - Definitely not an egg, what to choose? Maybe a box? “Maybe something tasty?” the teacher asked. - Then an apple or apple juice. Actually, I love a lot of things. I love sweets,” he continued. - Nikita, today we are talking about the letter "I". There is no "I" in the word "candy". "I" is in the word "apple", "apple juice". Choose what you will draw. “Apple,” the child replied.

After studying the "I" we moved on to the letters from the child's name. When they were completed, the adult, together with the child, signed his photo: “I .... (child's name)”.

Then the letters "M" and "A" were studied. The consistent study of the letters "M", "A" and the mother's photograph in the album with the caption "mother" involuntarily led the child to read the word "mother" instead of the abstract syllable "MA".

Mastering the letters, we tried to avoid the stereotype inherent in an autistic child and together with him to come up with as many words as possible that begin with the letter being studied. If you study a letter in one example, there is a danger that the child will associate it with only one specific word. For example, a teacher at a diagnostic appointment was faced with a situation where an autistic child could not read the word “house”, instead he called the words beginning with each letter in turn: “D” - “woodpecker”, “O” - “monkey”, “ M" - "motorcycle".

Next, we tried to create in the child the idea that any letter can occur at the beginning, in the middle or at the end of a word. If the letter being studied is always located only at the beginning of a word, an autistic child, with his inherent stereotype, remembers it in this position and may not recognize it in the middle or at the end of the word. For example, a child could learn that "A" is only "watermelon", "orange", "apricot", and not perceive it in other words (for example, "tea", "car").

Therefore, while studying, for example, the letter “M”, together with the child, we pasted a photo of the mother into the album, and next we drew a lamp and a house, signing the pictures and explaining to the child that the letter “M” can be in both the beginning and in the middle, and at the end of a word.

Photos and drawings in the album accompanied the whole process of learning letters and, in general, learning to read. Visualization is important for autistic children even more than for others, since their visual perception and attention in most cases prevails over auditory. Therefore, the teacher sought to supplement any oral instruction, oral explanation with a drawing, picture, photograph.

The child mastered the letter “P” in the word “dad” and two words in the name of which “P” occurs in the middle and at the end (for example, “hat”, “soup”).

To the previously studied letters "I", "M", "A", "P", as well as the letters from the child's name, the letters that make up the names of mother, father, (relatives) were added. Then the remaining letters corresponding to vowels were studied.

Then the remaining letters corresponding to vowels were studied.

Next, the question arose about the sequence of introducing the remaining letters into the primer, corresponding to consonant sounds. In our experience, this sequence was individual in each case, since it was set by the need to introduce a new letter at a certain point in time into a word familiar and interesting to the child. This guaranteed the meaningfulness of mastering all the letters of the alphabet by an autistic child (it formed an attitude towards them not as abstract icons, but as parts of a whole word and what it means).

For example, Marina P. (7 years old) has always been interested in the life of mice. The teacher, taking into account the interests of the girl, added “Sh” and “K” to the previously studied letters in order to collect the word “mouse”, and then “C” to draw “cheese”, the mouse’s favorite food, “D” - for “ holes" in cheese, "H" - for "mink", where the mouse lives, etc.

The meaningfulness of mastering letters was thus associated with the constant visual demonstration to the child of the essence of reading and writing, with the creation of conditions for the rapid mastery of these skills. The teacher always encouraged the child to first find the letter being studied in different words, then find and complete it in well-known words (“... ok”, “cha ... s”, “but ...”), and then independently write well-known words (“I” , "mother, father").

The teacher always encouraged the child to first find the letter being studied in different words, then find and complete it in well-known words (“... ok”, “cha ... s”, “but ...”), and then independently write well-known words (“I” , "mother, father").

In addition, we tried to connect the drawings in the album with the child's personal experience, with himself, his family, the objects of his favorite games and activities. For example, when learning the letter "D", the child could draw a cake with candles on the table and name the picture "Birthday". Joint drawing, emotional and semantic commentary, dialogue with the child about significant events helped, on the one hand, meaningful learning, and, on the other hand, emotional comprehension, the formation of a personal attitude of an autistic child to the events of his own life.

The sequence of working with the primer

At the first lesson in the album, which is called "My primer", the teacher in front of the child made a "working blank". In the upper left corner of the sheet, a “window” for the letter was drawn, next to it on the right - 3 rulers for writing it (in block letters). In the lower half of the sheet, 3 “windows” were outlined for drawings of objects in the name of which there is a given letter, and for signatures denoting them.

In the upper left corner of the sheet, a “window” for the letter was drawn, next to it on the right - 3 rulers for writing it (in block letters). In the lower half of the sheet, 3 “windows” were outlined for drawings of objects in the name of which there is a given letter, and for signatures denoting them.

Such preparation helped to organize the child's attention during the lesson. It is well known that an autistic child absorbs information more easily and completes a task faster if everything needed to complete the task (or complete the sequence of tasks) is in the child's field of vision. In addition, a good visual memory ensures that an autistic child captures visual information that is meaningful to him. At home, the child, together with his mother, made similar workpieces for mastering letters for each subsequent lesson.

A new letter was mastered on each page of the primer. At first, the teacher wrote this letter himself, commenting on the spelling: “A stick, a circle, a leg - the letter “I” turned out. ” The continuous writing of all the graphic elements of the letter was commented on and worked out by the teacher at the time of its development. Learning to write with a hand detachment after each element creates additional difficulties for an autistic child, who is characterized by fragmented perception and difficulty switching attention. True, when mastering some printed letters (“A”, “Sh”, “Yu”, etc.), it was not always possible to write them without taking your hands off. We taught the child to write such letters with the smallest hand separation.

” The continuous writing of all the graphic elements of the letter was commented on and worked out by the teacher at the time of its development. Learning to write with a hand detachment after each element creates additional difficulties for an autistic child, who is characterized by fragmented perception and difficulty switching attention. True, when mastering some printed letters (“A”, “Sh”, “Yu”, etc.), it was not always possible to write them without taking your hands off. We taught the child to write such letters with the smallest hand separation.

Then the teacher wrote a few letters on the first ruler and asked the child to circle them with a colored pencil or fountain pen. If he found it difficult to circle the letter on his own, the adult manipulated his hand. On the second line, the child wrote letters at the points that the adult marked for him as a guide, on the third - already on his own. It is also important that while working in the album, the child learned to see the “working line”, got used to writing along the line without going beyond it.

A child could also master writing a letter using a stencil. To do this, the stencil was superimposed on the landscape sheet, and the child circled it with a pencil, and then ran his finger over the stencil and over the written letter, thereby memorizing its “motor image”. The child was not faced with the task of writing all three lines of a new letter in class. Part of the task was completed in class, the rest of the letters were completed at home.

As soon as the child wrote several letters on his own or did it with the help of an adult, the teacher named three words in the name of which the studied letter occurs at the beginning, middle and end. The teacher asked the child to repeat these words and pointed to three windows at the bottom of the sheet. Then the adult wrote the studied letter in three boxes, each time in the place where it should be in the named word. For example, the teacher said the first word "juice" and wrote "C" at the beginning of the first box, said "hours" and wrote "C" in the middle of the second box, said "nose" and wrote "C" at the end of the third box.

The child did not have to immediately add the words, because for this he needed to quickly analyze what sounds they consisted of, and correctly place each word on the sheet. We led the child to solve these problems gradually, while we were drawing together with him in the windows the objects we named. If it was difficult for the child to draw the desired object on his own, the teacher helped by leading him with his hand. We did not strive to completely draw all the objects in the lesson. It was enough for the child to draw the outlines of objects in the classroom, and then paint over them at home.

It was more important, in our opinion, not just to draw an object with the right letter with the child, but to give this object some features that would connect it with the child's personal experience. For example, we encouraged the child to paint on a plate, exactly the same as at home, to a previously drawn apple, or draw a familiar fringed home rug under the ball. With the help of emotional and semantic commentary, the teacher always sought to connect the child's drawing with a specific life situation familiar to him.

In addition, the teacher's commentary was aimed at expanding the child's ideas about the properties and qualities of objects. An autistic child could see these objects in everyday life, even play with them, get acquainted with their sensory properties. But, doing this involuntarily, the child was not aware of either the qualities themselves or their connection with a particular object, with its functional significance. Therefore, the teacher’s reasoning became a real discovery for him, for example, that “you and I are now drawing an apple, look how green it is, fragrant and with a twig on top, and sour and round ...”. The child listened with interest to the adult, saying at the same time: “more”, “and then”, and continued to draw.

Sequential drawing of objects in each of the three windows made it possible to immediately show the child the place of the desired word on the sheet. That is, here, as in many other cases, we used a visual rather than verbal explanation, taking into account the cognitive characteristics of an autistic child. Signing drawings with words formed the interest of an autistic child in written language. In addition, thanks to a good visual memory, he quickly memorized the correct spelling of words. While the child did not know all the letters of the alphabet, he wrote only the familiar letter in the word. More precisely, he circled the letter being studied, which the adult had already written in three boxes. Later, as the child mastered the alphabet, the child wrote in the word all the letters he knew.

Signing drawings with words formed the interest of an autistic child in written language. In addition, thanks to a good visual memory, he quickly memorized the correct spelling of words. While the child did not know all the letters of the alphabet, he wrote only the familiar letter in the word. More precisely, he circled the letter being studied, which the adult had already written in three boxes. Later, as the child mastered the alphabet, the child wrote in the word all the letters he knew.

Over time, the child could come up with words with the studied letter. It was important to teach him not to rush, to listen to himself and check the pronunciation of the word with its spelling. For example, while studying the letter "B", we asked the child to write the word "mushroom". The child pronounced “flu” and informed the teacher that the letter “B” was not in this word. Then the teacher told the child that some words are not spelled the way we hear and pronounce them. In this example, the teacher first suggested “naming the mushroom affectionately” (“fungus”, “mushroom”), and then finishing the phrase: “Many, many grow in the forest . ..” (“mushrooms”) so that the child hears the desired sound. If there was no “logical” explanation for spelling, the teacher explained to the child, for example, like this: “Despite the fact that we pronounce the word “marozhin”, you need to write “ice cream”. Thus began the necessary work on sound-letter analysis and mastering the rules of spelling words.

..” (“mushrooms”) so that the child hears the desired sound. If there was no “logical” explanation for spelling, the teacher explained to the child, for example, like this: “Despite the fact that we pronounce the word “marozhin”, you need to write “ice cream”. Thus began the necessary work on sound-letter analysis and mastering the rules of spelling words.

When all items were signed, the teacher asked the child to circle or underline the letter in the words being studied. At the same time, first the teacher, and later the child himself, named the place of the letter in the word.

For example, Nikita V. (7 years old) spoke about the letter “Sh”: “This is “Sh”. This is my favorite puppy. "Sch" begins with "puppy".

Then the child spoke in great detail about what his puppy likes to do, and continued his reasoning: “These are vegetables: carrots, potatoes, cabbage. Beet. Here it is "Sh" - in the middle of the word. And this is a bowl of soup. “A plate of borscht,” the teacher corrected him. — Nikita, is there a “Sch” in the word “borscht”? - Of course, there is, it ends with "Sch".

— Nikita, is there a “Sch” in the word “borscht”? - Of course, there is, it ends with "Sch".

At the end of the lesson, we talked with the child, turning to his mother, what he learned today. In the first lessons, the teacher did this from a single “common face” (“We”) with the child, accompanying her story by showing the page of the primer. This fixed in the child's memory the sequence of performing tasks in the lesson, which subsequently helped him to independently plan his actions. In addition, emotionally commenting, pronouncing what happened in the lesson, the teacher brought to the child's consciousness the meaning of what happened in the lesson (what and how the child studied, how he did it, who would praise him for it, etc.).

For example? First, Nikita and I learned a new letter "I" and learned how to write it. Then we pasted Nikitin's photograph into the primer and signed it "I". Then we drew a ball and a snake and signed them. Nikita - well done, he tried so hard, he wrote and drew so well! He made us all happy: me, my mother, and the nanny! And dad will look at the album at home and ask: “Who painted the ball, the snake so beautifully, wrote the letter “I”? This is probably a mother or a nanny? “No, it’s me myself,” answered the child.

General the sequence of work with the primer can be represented as follows:

- Learning a new letter. The letter is first written by an adult, then the child himself (or an adult with his hand).

- Drawing objects whose names contain the letter being studied. The child independently or with the help of an adult draws objects or finishes some detail in a drawing made by an adult.

- Signing of drawn objects. The child himself or with the help of an adult writes a familiar letter in the word. If necessary, writing a letter is worked out in advance with the help of exercises.

1-2 lessons were assigned to study one letter.

When all the letters of the alphabet have been completed, The Personal Primer usually becomes the autistic child's favorite book. If we asked children to bring an ABC book to class, they most often protested, so we had to come up with special pretexts for this - "Let's show the kids who can't read yet to their parents. " The primer became a valuable personal book for the child, which he cherished very much.

" The primer became a valuable personal book for the child, which he cherished very much.

For example, Zhenya L.'s mother (8 years old) said that his "Personal primer" should not be taken out of the house. The child does not go to bed until he has watched it from beginning to end.

Further, the teacher could use the traditional primer in the classroom. He no longer aroused anxiety in the child, on the contrary, he began to show cognitive interest in him.

For example, the mother of Tyoma G. (7 years old) said that when her son saw several primers on a bookcase, he asked her to buy them all at once. "Why do we need so many?" Mom asked. “You, me and dad,” he replied.

Thus, the “Personal Primer” introduced the autistic child to letters, helped him remember their graphic representation, gave him the idea that letters are components of words, that words can denote different objects or be the names of close people. Of course, by inscribing familiar letters at the beginning, middle, and end of words, the child was formally ready to master analytical reading. However, knowing that the process of folding letters or syllables into words would inevitably distract the autistic child from their meaning, we preceded the development of analytical reading with a short stage of “global reading”, within which we gave the child the idea that only a whole word has a certain meaning and that words can form phrases.

However, knowing that the process of folding letters or syllables into words would inevitably distract the autistic child from their meaning, we preceded the development of analytical reading with a short stage of “global reading”, within which we gave the child the idea that only a whole word has a certain meaning and that words can form phrases.

Summing up, we list the necessary skills developed in a child with ASD at the initial stage of learning to read in the process of creating a "Personal primer":

- The ability to correctly recognize and name the letter separately and in words.

It was important for the teacher not only to teach the child to name the letter correctly, but also to recognize the location of the letter in the word. If the child stereotypically repeated his examples after the teacher, but could not come up with his own, the skill was not considered formed. Assimilation of a letter was assessed by the child's ability to come up with (or independently recall) words with the studied letter. Even if he independently came up with only one word that began with the letter being studied, we considered the skill to be formed. For example, when naming the letter "I", the child could say "pit", "box", for the letter "K" - "pit", for "C" - "construction", "pump". The spelling of some words the child could remember from books, magazines that he saw at home or in newsstands.

Even if he independently came up with only one word that began with the letter being studied, we considered the skill to be formed. For example, when naming the letter "I", the child could say "pit", "box", for the letter "K" - "pit", for "C" - "construction", "pump". The spelling of some words the child could remember from books, magazines that he saw at home or in newsstands. - The ability to correctly write a letter separately and in words.

Thanks to instant visual memory and interest in abstract signs, an autistic child can involuntarily remember the graphic image of many letters and write them in a chaotic way, upside down, in a mirror image, enjoying the image of “incomprehensible icons”. However, it is much more important for us that the child learns to write letters as part of a meaningful voluntary activity, realizing the possibility and necessity of using the writing skill in his life. Therefore, the skill was considered formed when the child not only could write the studied letter separately, but also wrote it in words in the right place.

Examples of the pages of the "Personal primer"

The project "Personal primer" - semantic reading and writing (authors of the ICP RAO: N.B. Lavrentyeva, M.M. Liebling, O.I. Kukushkina) is being prepared for publication by the publishing house "Enlightenment" (expected by December 2017).

special schools or online learning for autistic children

Let's start with some terms. Autism as an independent concept exists only at the everyday level. This diagnosis is poorly understood, so it is not made. Instead, in the conclusions of the Territorial Psychological-Medical-Pedagogical Commission (TPMPK) one can meet ASD - an autism spectrum disorder.

In the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), a whole section F84 is allocated for psychological disorders. This included childhood autism (F84.0), atypical autism (F84.1), Rett syndrome (F84.2) and Asperger's syndrome (F84.5). A specific diagnosis is rarely made, they are very similar to each other. Usually, doctors limit themselves to F84, which can be read as "The child has ASD."

Usually, doctors limit themselves to F84, which can be read as "The child has ASD."

Consider the most common misconceptions and figure out what is actually hidden behind this word.

Myths about ASD

Not able to feel

It is generally accepted that children with autism do not feel anything, do not show emotions, do not know how to be affectionate and gentle with loved ones.

Actually: approximately the same processes take place inside any child. Children with ASD know how to get angry, cry, worry and sympathize. The difference is that they don't show it, so they may seem indifferent.

Don't look into their eyes

This misconception is related to the first one: if children with autism are not capable of feelings, then it is pointless to look into their eyes.

Actually: children with ASD look through the person, as if through the eyes. They just don't pay attention.

Brilliant

There is an opinion that if a person has autism, then he accurately reproduces maps of the world from memory, multiplies five-digit numbers in his head or recites “War and Peace” by heart.

Actually: the frequency of giftedness among people with autism is about the same as the rest.

Genes or vaccines are to blame

The myth began in 1998 when Andrew Wakefield published an article in The Lancet in which he linked autism to vaccines. The sample then was only 12 people. A year later, a refutation came out with 500 study participants, in 2005 with 10 million children, and in 2011 with almost 15 million.

Fact: The relationship between autism and vaccines and genes has not been proven. The phenomenon as a whole has been little studied.

When we have dispelled all the myths, let's figure out what it really means.

<

ASD Facts

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, ASD now affects one in 54 children.

The manifestations of autism are called autism spectrum disorders because there are signs that are the same for everyone, but they can manifest themselves in different degrees. This is the spectrum - variety in monotony.

Typical manifestations:

- difficulties in social communication;

- difficulty processing sensory information;

- repetitive, stereotyped behaviour;

- Rigidity, i.e. lack of response to stimuli: for example, will not withdraw his hand if he is pinched.

How to educate children with ASD

A child with ASD in elementary school can be taught according to one of the four GEF programs:

- 8.1 for children with intact intelligence

The level of final development: as in peers with the norm of development.

Study period: four years.

- 8.2 for children with ASD and mental retardation (MPD)

Level of final development: as in peers with normal development.

Terms of study: five years if he was in kindergarten, and six if he was not.

- 8.3 for children with mild and moderate intellectual disabilities (ID)

The level of final development: lower than that of peers with developmental norms.

Study duration: six years.

- 8.4 for children with severe ID and multiple disabilities

Level of final development: lower than that of peers with normal development.

Study duration: six years.

Starting from secondary school , children with ASD study according to the regular GEF.

What should be emphasized in education

Socialization, communication with peers and adults

The child does not need to build communication on his own, especially if he does not speak. Therefore, an adult needs to artificially create situations for communication: for example, ask to pass an object.

Everyday skills

This is what the child needs to master before the rest of the education. Sometimes it's the only thing a child can do. To do this, an adult needs to literally follow the child: hand in hand, put things in their places, hold a spoon, get dressed.

Correction of unwanted behavior

This can be injuring yourself and others, pinching, biting, screaming. The parent should contact a specialist - a defectologist who will help build the path "problem - explanation - solution". It is possible to achieve corrective results on your own, but, most likely, it will take a lot of time to find the optimal path.

The decision on how and where to educate a child is always made by the parents (Article 44 of the federal law on education in the Russian Federation). TPMPC can only recommend an institution.

<

Which schools attend children with ASD

Special schools

There are no special schools for children with ASD exclusively. Usually they are sent to where children with intellectual disabilities (ID) or mental retardation (MPD) study or to the so-called "speech school".

Usually they are sent to where children with intellectual disabilities (ID) or mental retardation (MPD) study or to the so-called "speech school".

Public schools

There can be two options here:

- regular class, which will be equated with inclusive;

- a correctional class in a regular school, which is called integration.

In an inclusive classroom, a child with ASD will study on an equal footing with children with a norm. Usually this option is chosen for a child with a norm of intelligence and speech. In an integrative class, children with various disabilities or only with ASD can study. Accordingly, they have their own program and educational route.

Ordinary schools can be public or private, it doesn't matter. The school can organize a resource zone - this is a place where a child with ASD can come to take a break from social contact. There may be a dry pool, carpets, sofas, pillows, "rain" hanging from the ceiling.