Death of an infant

Dealing with grief after the death of your baby

What is grief?

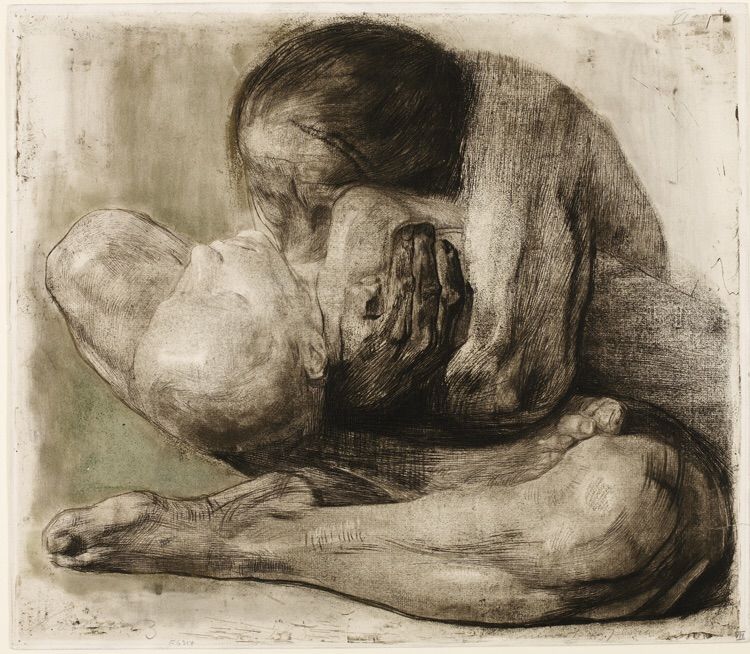

Grief is all the feelings you have when someone close to you dies. You may find it hard to believe that your baby died. You may want to shout or scream or cry. You may want to blame someone. Or you may want to hide under the covers and never come out. At times, your feelings may seem more than you can handle. You may feel sad, depressed, angry or guilty. You may get sick easily with colds and stomach aches and have trouble concentrating. All of these are part of grief.

When your baby dies from miscarriage, stillbirth or at or after birth, your hope of being a parent dies, too. Miscarriage is when a baby dies in the womb before 20 weeks of pregnancy; stillbirth is when a baby dies in the womb after 20 weeks of pregnancy. The dreams you had of holding your baby and watching him grow are gone. So much of what you wanted and planned for are lost. This can leave a large, empty space inside you. It may take a long time to heal this space.

The death of a baby is one of the most painful things that can happen to a family. You may never really get over your baby’s death. But you can move through your grief to healing. As time passes, your pain eases. You can make a place in your heart and mind for the memories of your baby. You may grieve for your baby for a long time, maybe even your whole life. There’s no right amount of time to grieve. It takes as long as it takes for you. Over time, you can find peace and become ready to think about the future.

How do men and women grieve?

Everyone grieves in his own way. Men and women often show grief in different ways. Even if you and your partner agree on lots of things, you may feel and show your grief differently.

Different ways of dealing with grief may cause problems for you and your partner. For example, you may think your partner isn’t as upset about your baby’s death as you are. You may think he doesn’t care as much. This may make you angry. At the same time, your partner may feel that you’re too emotional. He may not want to hear about your feelings so often, and he may think you’ll never get over your grief. He also may feel left out of all the support you’re getting. Everyone may ask him how you’re doing but forget to ask how he’s doing.

He may not want to hear about your feelings so often, and he may think you’ll never get over your grief. He also may feel left out of all the support you’re getting. Everyone may ask him how you’re doing but forget to ask how he’s doing.

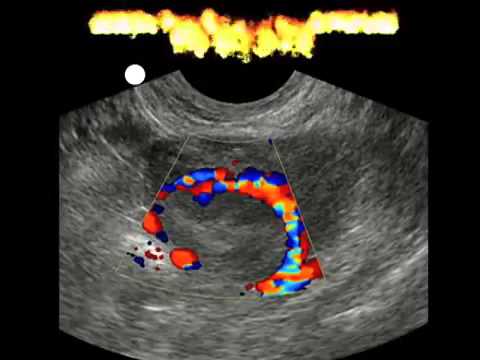

You have a special bond with your baby during pregnancy. Your baby is very real to you. You may feel a strong attachment to your baby. Your partner may not feel as close to your baby during pregnancy. He doesn’t carry the baby in his body, so the baby may seem less real to him. He may become more attached to the baby later in pregnancy when he feels the baby kick or sees the baby on an ultrasound. Your partner may be more attached to your baby if she dies after birth.

In general, here’s how you may show your grief:

- You may want to talk about the death of your baby often and with many people.

- You may show your feelings more often. You may cry or get angry a lot.

- You may be more likely to ask your partner, family or friends for help.

Or you may go to your place of worship or to a support group.

Or you may go to your place of worship or to a support group.

In general, here’s how your partner may show his grief:

- He may grieve by himself. He may not want to talk about his loss. He may spend more time at work or do things away from home to keep his mind off the loss.

- He may feel like he’s supposed to be strong and tough and protect his family. He may not know how to show his feelings. He may think that talking about his feelings makes him seem weak.

- He may try to work through his grief on his own rather than ask for help.

Showing grief doesn’t have any rules or instructions. Men and women often may show grief in these ways. But there’s really no right or wrong way for you or your partner to grieve or share your feelings. It’s OK to show your pain and grief in different ways. Be patient and caring with each other. Try to talk about your thoughts and feelings and how you want to remember your baby.

How do children grieve?

Children of all ages grieve. If you have older children, they may be afraid, act out or need special attention after your baby’s death. They may think they’re going to die, too, or that they’re to blame for the death of their brother or sister. Children can cope better with grief when you explain things and so they know what’s happening.

If you have older children, they may be afraid, act out or need special attention after your baby’s death. They may think they’re going to die, too, or that they’re to blame for the death of their brother or sister. Children can cope better with grief when you explain things and so they know what’s happening.

Here are some ways you can help them better understand the baby's death:

- Use simple, honest words when you talk to them about the baby’s death. You can say things like, “The baby didn’t grow,” or “The baby was born very tiny.” Don’t say things that may confuse them like, “The baby is sleeping,” or “Mommy lost the baby.”

- Read them stories that talk about death and loss. A funeral home, library or school may have children’s books to help them understand death.

- Encourage them to tell you how they feel about the baby’s death. Let them ask questions about what happened to the baby and how you’re doing.

- Ask them to help you find ways to remember the baby.

Ask them to draw a picture or make something that you can keep.

Ask them to draw a picture or make something that you can keep. - Tell them they’re not going to die and that no one is to blame for the baby’s death.

Just like you, children may feel hurt, confused and angry as they grieve. Younger children may be clingy or cranky and act in ways that they haven’t for a long time. Older children may be extra worried about things outside of home, like school, friends or sports. Or they may show no reaction at all to the baby’s death or ask questions that you think are rude or uncaring. If your children act out, be patient and loving.

It may be helpful for your older children to see a grief counselor. This is a person who’s trained to help people deal with grief. A grief counselor who works with children can recommend resources, like bereavement groups just for kids. A bereavement group is a group of people who meet together to heal from grief. To find a grief counselor for your children or to help you with your children, ask your provider, your child’s provider or a social worker at the hospital.

Who can help you and your family deal with grief?

Talking about your baby and your feelings can be helpful and comforting. Of course you can talk to your partner, your friends and your family. But talking to someone who’s trained to help you deal with grief may be useful. For example:

- Your provider. Your provider may be able to help you understand what happened to cause your baby’s death. She also can help you find people to help you through your grief, like a social worker or grief counselor. And if you’re ready, she can help you get ready to get pregnant again. If you feel intense sadness for a long time, your provider can help you get treatment for depression.

- A social worker. This is a mental health professional who helps people solve problems and make their lives better. A social worker can help you deal with your grief, and she can also help with things like medical, insurance and funeral bills. Your hospital may have a social worker on staff.

- A grief counselor. This is someone who’s trained to help people deal with grief.

- Your religious or spiritual leader. Your religious and spiritual beliefs may be a comfort to you as you grieve.

You may want to join a support or bereavement group. A support group is a group of people who have the same kind of concerns. They meet to share their feelings and try to help each other. There are support and bereavement groups just for parents and families who have lost a baby. Group members understand what you're going through and can help you feel like you’re not alone. Your provider, social worker or grief counselor can help you find a group, or your hospital may have a group as part of a loss and grief program for families. You can find groups online, too, like Share Your Story, the March of Dimes online community where families who have lost a baby can talk to and comfort each other. We also offer the free booklet From hurt to healing that has information and resources for grieving parents.

How can you take care of yourself as you grieve?

Your body needs time to recover after pregnancy. You may need more time depending on how far along you are when your pregnancy ends. Here’s what you can do to take care of yourself:

- Eat healthy food, like fruits and vegetables, whole-grain breads and pastas, and low-fat chicken and meats. Stay away from junk food and too many sweets.

- Do something active every day.

- Try to stick to a sleep schedule. Get up and go to bed at your usual times.

- Don’t drink alcohol (beer, wine, wine coolers and liquor) and drinks with caffeine in them, like coffee, sports drinks, tea and soda. Chocolate and some medicines also contain caffeine. Alcohol and caffeine can make you feel bad and make it hard for you to sleep. Instead, drink water or juice.

- Don’t smoke and stay away from secondhand and thirdhand smoke. Secondhand smoke is smoke you breathe in from someone else’s cigarette, cigar or pipe.

Thirdhand smoke is what you smell on things that been in or around smoke.

Thirdhand smoke is what you smell on things that been in or around smoke. - Talk to your provider if you have bleeding from your vagina or if your breasts have milk

- Tell your provider if you have intense feelings of sadness that last more than 2 weeks that prevent you from leading your normal life. If so, you may need treatment for depression. Treatment can help you feel better. If you’re thinking about suicide or death, call 911.

You need time to recover emotionally, too. Certain things, like hearing names you were thinking of for your baby or seeing the baby’s nursery at home, may be painful reminders of your loss. Your body’s physical recovery also may remind you of your baby, like if your breast milk comes in after a stillbirth. A counselor, social worker or support group can help you learn how to deal with these situations and the feelings they create.

How can you handle family and friends while you're grieving?

Your baby’s death affects your friends and family, too. It may be hard dealing with others as you're grieving yourself. Here are some things you can do to help you handle others as you grieve. Do only what feels right for you:

It may be hard dealing with others as you're grieving yourself. Here are some things you can do to help you handle others as you grieve. Do only what feels right for you:

- Tell them that their calls and visits are important to you.

- Decide if it’s OK for them to ask questions about what happened to your baby. If not, tell them you’re not ready to talk about it.

- Tell them it’s OK if they don’t know exactly what to say. Tell them that hearing honest words like, "I just don’t know what to say," or "I want to help but I don't know how," can be comforting. People may say things that aren’t helpful to you like, "It’s for the best," or "You can always have another baby." Try to remember that they’re doing their best to support you, even if what they say is hurtful.

- Tell them exactly what you need. Do you just want them to spend time with you at home? Do you need someone to bring you a meal, shop for groceries, take your older children out or do your laundry? Tell them specific things they can do for you.

- If you want them to, ask them to use your baby’s name and to remember your baby. Tell them that even if you have other children, you won’t forget the baby who died.

- Thank them for their patience and support.

Some people may expect you to limit your grief or get over it in a certain amount of time. Take as long as you need to cope with your loss. Support from others may lessen over time. This doesn’t mean that they've forgotten about your baby or that they don't care. You may need to tell them that you’re still grieving and that you still need their support.

What if you lose a multiple?

Any parent who loses a baby feels grief. But losing one, two or a whole set of multiples can create its own set of feelings. Multiples means being pregnant with more than one baby, like twins, triplets or more. If you lost a multiple, you may feel:

- Sad about not having time to grieve for your baby who died. If you lose a baby and have one who lives, it may be hard to find time to grieve while you’re caring for your living baby.

- Scared. If your living baby is sick, you may be scared that he will die, too. You may not want to hold him, get close to him or care too much for him. It may be hard for you to go to the newborn intensive care unit (also called NICU) to care for your living baby if your other baby died there. The NICU is a nursery in a hospital where sick newborns get medical care.

- Confused. Even if only one baby lives, you’re still the parent of multiples. But others may not see you this way. Your family and friends may not want to talk about the baby who died. They may think remembering the baby you lost will make you sad.

- Happy and sad about bringing your baby home. You may feel happy about the baby you bring home from the hospital and sad about the baby you lost.

- Worried. The most common complication of being pregnant with multiples is premature birth (before 37 weeks of pregnancy). Premature birth can cause health problems for babies. If your baby was born prematurely, you may be worried about her health.

- Always reminded of the baby you lost. You may wonder what it would have been like if your baby had lived. It may be hard for you to celebrate birthdays and holidays if you’re thinking about the baby who died.

What can you do to remember your baby?

You can do special things to remember your baby, even if didn’t have a chance to see, touch or hold him. Remember your baby in ways that are special to you. You may want to:

- Collect things that remind you of your baby, like ultrasound pictures, footprints, a lock of hair, a hospital bracelet, photos, clothes, blankets or toys. Put them in a special box or scrapbook. Keepsakes like these can help you remember your baby.

- Have a service for your baby, like a memorial service or a funeral. A service can give you a chance to say goodbye to your baby and share your grief with family and friends. Your hospital may have a service each year to remember babies who have died.

- Write your thoughts and feelings in a journal, or write letters or poems to your baby.

Tell your baby how you feel and how much you miss her. Or paint a picture for her.

Tell your baby how you feel and how much you miss her. Or paint a picture for her. - Light a candle or say a prayer in honor of your baby on holidays or special days, like his birthday or the day he died. Do something on your own or bring family and friends together to remember your baby. Read books and poems or listen to music that you like and find comforting.

- Plant a tree or a small garden in honor of your baby.

- Have a piece of jewelry made with your baby’s initials or her birthstone.

- Donate to or volunteer for a charity in your baby’s name, or give something to a child in need who’s about the same age as your baby would be. Dedicate a project to your baby, like raising money to build a swing set in a park.

More information

- From hurt to healing (free booklet from the March of Dimes for grieving parents)

- Share Your Story (March of Dimes online community for families to share experiences with prematurity, birth defects or loss)

- Centering Corporation (grief information and resources)

- Center for Loss in Multiple Birth, Inc.

(for families who have lost a multiple)

(for families who have lost a multiple) - Compassionate Friends (support for families after the death of a child)

- First Candle (support for families with children who died of SIDS or preventable stillbirth)

- International Stillbirth Alliance

- Journey Program of Seattle Children’s Hospital (support for families after the death of a child)

- Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep (remembrance photography)

- Perinatal Hospice & Palliative Care (resources for parents who find out during pregnancy that their baby has a life-limiting condition)

- Share Pregnancy & Infant Loss Support (resources for families with pregnancy or infant loss)

- Star Legacy Foundation (support for families who have had a stillbirth)

- Twinless Twins Support Group International (support for families who have lost a multiple)

Last reviewed: October, 2017

Neonatal death

Topics

In This Topic

KEY POINTS

-

The most common causes of neonatal death are premature birth, low birthweight and birth defects.

-

An autopsy may help you find out why your baby died. You can choose whether or not you want to have an autopsy on your baby.

Your health care provider or a genetic counselor may help you learn why your baby died and if you may have the same problems in another pregnancy.

-

Getting counseling and support can help you cope with your baby’s death.

What is neonatal death?

Neonatal death is when a baby dies in the first 28 days of life. If your baby dies this soon after birth, you may have many questions about how and why it happened. Your baby’s health care provider can help you learn as much as possible about your baby’s death.

Neonatal death happens in about 4 in 1,000 babies (less than 1 percent) each year in the United States. Non-Hispanic black women are more likely to have a baby die than women of other races or ethnicities.

What are common causes of neonatal death?

The most common causes of neonatal death are:

- Premature birth.

This is when a baby is born too early, before 37 weeks of pregnancy. Babies born too early may have more health problems than babies born on time.

This is when a baby is born too early, before 37 weeks of pregnancy. Babies born too early may have more health problems than babies born on time. - Low birthweight. This is when a baby is born weighing less than 5 pounds, 8 ounces. Babies born too small may have more health problems than babies born at a healthy weight.

- Birth defects. Birth defects are health conditions that are present at birth. Birth defects change the shape or function of one or more parts of the body. They can cause problems in overall health, how the body develops or in how the body works.

Premature birth and low birthweight cause about 1 in 4 neonatal deaths (25 percent). Birth defects cause about 1 in 5 neonatal deaths (20 percent).

Other causes of neonatal death include:

- Problems in pregnancy, like preeclampsia. This is a condition that can happen after the 20th week of pregnancy or right after pregnancy.

It’s when a pregnant woman has high blood pressure and signs that some of her organs, like her kidneys and liver, may not be working properly. Signs of preeclampsia include having protein in the urine, changes in vision and severe headaches.

It’s when a pregnant woman has high blood pressure and signs that some of her organs, like her kidneys and liver, may not be working properly. Signs of preeclampsia include having protein in the urine, changes in vision and severe headaches. - Problems with the placenta, umbilical cord and amniotic sac (bag of waters). The placenta grows in your uterus (womb) and supplies the baby with food and oxygen through the umbilical cord. The amniotic sac contains the fluid that surrounds the baby in the womb.

- Infections, like sepsis. Sepsis is a serious blood infection.

- Asphyxia. This is when a baby doesn’t get enough oxygen before or during birth.

Why are premature babies more likely to die shortly after birth than babies born on time?

Some premature babies may develop serious complications that can sometimes cause death. These complications include:

- Respiratory distress syndrome (also called RDS).

This is a breathing problem most common in babies born before 34 weeks of pregnancy. Babies with RDS don’t have a protein called surfactant that keeps small air sacs in the lungs from collapsing. RDS causes about 825 neonatal deaths each year.

This is a breathing problem most common in babies born before 34 weeks of pregnancy. Babies with RDS don’t have a protein called surfactant that keeps small air sacs in the lungs from collapsing. RDS causes about 825 neonatal deaths each year. - Intraventricular hemorrhage (also called IVH). This is bleeding in the brain. Most brain bleeds are mild and resolve themselves with no or few lasting problems. More severe bleeds can cause serious problems for a baby.

- Necrotizing enterocolitis (also called NEC). This is a problem with a baby’s intestines. It can cause feeding problems, a swollen belly and diarrhea. It sometimes happens 2 to 3 weeks after a premature birth. It can be treated with medicine and sometimes surgery. But in serious cases, it can cause death.

- Infections. Premature babies often have trouble fighting off germs because their immune systems aren’t fully formed. Infections that may cause death in a premature baby include pneumonia (a lung infection), sepsis (a blood infection) and meningitis (an infection in the fluid around the brain and spinal cord).

What birth defects most often cause neonatal death?

The most common birth defects that cause neonatal death include:

- Heart defects. Most babies with heart defects survive and do well because of medical treatments and surgery. But babies with serious heart defects may not survive long enough to have treatment, or they may not survive after treatment.

- Lung defects. A baby may be born with problems in one or both lungs or with lungs that aren’t fully developed. Lung defects can happen when the lungs don’t develop correctly due to other birth defects or pregnancy problems (such as not enough amniotic fluid). Premature babies can have lung problems that cause neonatal death.

- Genetic conditions. Genes are part of the cells in your body. They store instructions for the way your body grows, looks and works. Genetic conditions are caused by a gene that’s changed from its regular form. A gene can change on its own, or the changed gene can be passed from parents to children.

- Brain conditions. Neonatal death can be caused by problems in the brain, like anencephaly. This is a condition called a neural tube defect (also called NTD) in which most of a baby’s brain and skull are missing. Babies with anencephaly may be stillborn (when a baby dies in the womb after 20 weeks of pregnancy) or die in the first days of life. If you’ve had a baby with anencephaly, talk to your health care provider about taking folic acid to help prevent NTDs in your next pregnancy.

Your health care provider can use prenatal tests (medical tests you get during pregnancy) to check your baby for birth defects before birth. These tests include:

- Amniocentesis (also called amnio). In this test, your provider takes some amniotic fluid from around your baby in the uterus. The test checks for birth defects and genetic conditions in your baby. You can get this test at 15 to 20 weeks of pregnancy.

- Chorionic villus sampling (also called CVS).

This test checks tissue from the placenta to see if your baby has a genetic condition, like Down syndrome. You can get CVS at 10 to 13 weeks of pregnancy.

This test checks tissue from the placenta to see if your baby has a genetic condition, like Down syndrome. You can get CVS at 10 to 13 weeks of pregnancy. - Ultrasound. This test uses sound waves and a computer screen to show a picture of a baby in the womb. It can help find birth defects like spina bifida, anencephaly and heart defects.

Do you need to have an autopsy on your baby?

Your baby’s health care providers can tell you what they know about what caused your baby to die. If you want more information, you may want to have an autopsy on your baby. An autopsy is a surgical exam of your baby’s body after death to help find the cause of death and any diseases or injuries. An autopsy gives information about why a baby dies in more than 1 in 3 cases. This information can be helpful to you if you think you may want to have another baby in the future. It’s your choice whether or not to have an autopsy on your baby. Families often have to pay for an autopsy, so ask your baby’s health care provider about payment. Some hospitals or states may pay for a baby’s autopsy; most health insurance companies don’t pay for one.

Some hospitals or states may pay for a baby’s autopsy; most health insurance companies don’t pay for one.

If you don’t want to have an autopsy, your baby’s health care provider may be able to use other tests to find more information about why your baby died. These tests include genetic tests, X-rays and tests on the placenta and umbilical cord.

If the cause of your baby’s death was a birth defect, you can meet with a genetic counselor to learn more about it. You also can learn about the chances of having another baby with the same birth defect. A genetic counselor is a person who is trained to help you understand about how genes, birth defects and other medical conditions run in families, and how they can affect your health and your baby’s health.

How can you deal with your grief?

Talking about your feelings may help you deal with the grief you feel about your baby’s death. Grief is all the feelings you have when a loved one dies. Visit shareyourstory.org, our online community where families who have lost a baby can talk to and comfort each other. Sharing your baby’s story may ease your pain and help you heal.

Sharing your baby’s story may ease your pain and help you heal.

More information

- From hurt to healing (free booklet from the March of Dimes for grieving parents)

- Share Your Story (March of Dimes online community for families to share experiences with prematurity, birth defects and loss)

- Centering Corporation (general grief information and resources)

- Compassionate Friends (resources for families after the death of a child)

- First Candle (resources for families after the death of a child by SIDS or preventable stillbirth)

- Journey Program of Seattle Children’s Hospital (resources for families after the death of a child)

- Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep (remembrance photography)

- Perinatal Hospice & Palliative Care (resources for parents who find out during pregnancy that their baby has a life-limiting condition

- Share Pregnancy & Infant Loss Support (resources for families with pregnancy or infant loss)

- Star Legacy Foundation (resources for families who have had a stillbirth)

Last reviewed: October, 2017

') document. write('

write('

Preterm labor & premature birth

') document.write('') }

') document.write('') }

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS)

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome is the sudden death of an infant for which there is no clinical and pathological explanation. It is known that this syndrome often affects boys, the age of 2-4 months is considered the most dangerous for the development of the syndrome. Most often, sudden infant death occurs in the autumn or winter months of the year.

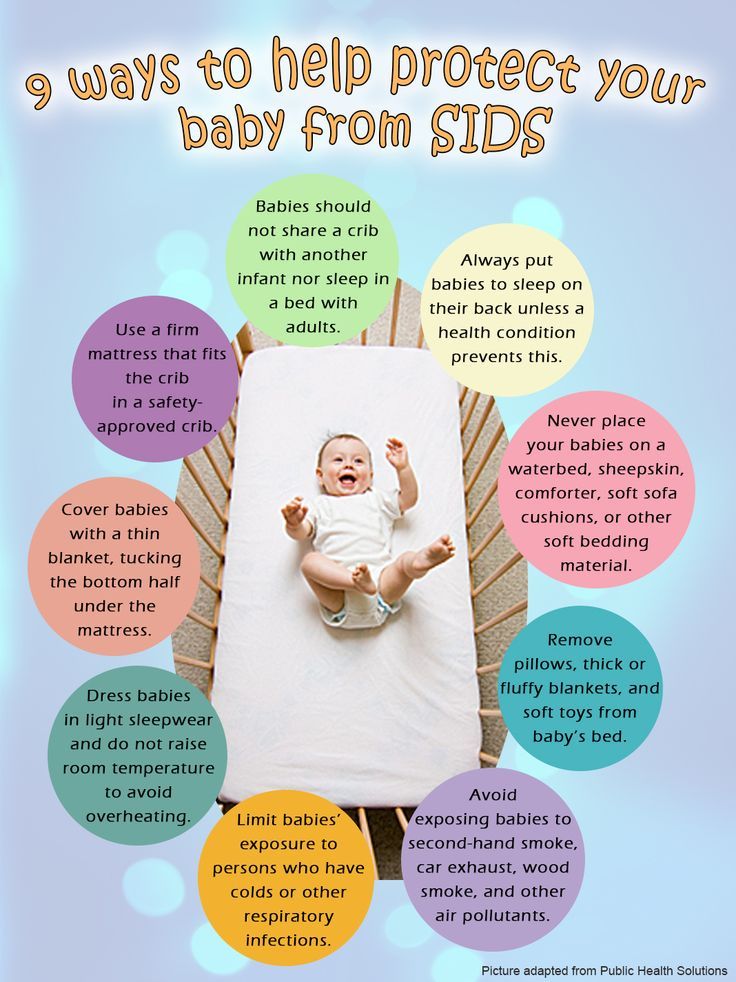

SIDS Prevention

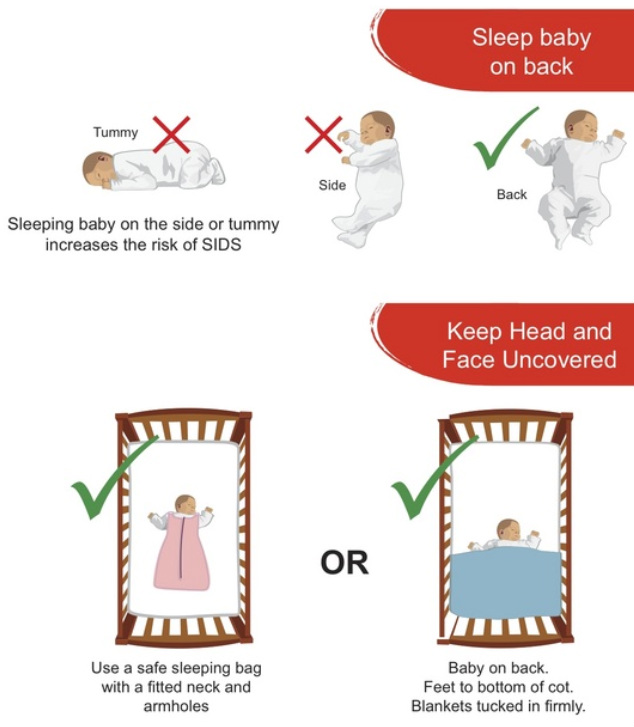

- Creating optimal sleep conditions: the child should sleep on a firm mattress, without a pillow, in the same room as the parents, but in a separate bed.

- Avoid exposure of the child to strong odors (tobacco, alcohol, perfumes), sounds and light stimuli, especially during sleep, including daytime.

Often, in response to an unpleasant odor, children experience a slowdown or cessation of respiratory movements, tachycardia.

Often, in response to an unpleasant odor, children experience a slowdown or cessation of respiratory movements, tachycardia. - Do not allow smoking in an apartment where a small child lives. Children of smoking mothers are 5 times more likely to die suddenly.

- Compliance with the temperature regime in the children's room. The optimum air temperature is + 20 + 22 C. In the room where the child sleeps, the air temperature should be comfortable for an adult wearing a short-sleeved shirt. If the skin between the shoulder blades of the child is warm, but not sweaty, then he is comfortable.

- During sleep, the child should be covered with a light blanket up to shoulder level, which should be light. A wadded blanket can crush a child with its weight or cause suffocation.

- During sleep, the child should lie on his back. In the position on the stomach, the chest is pressed against a hard mattress, which limits respiratory movements and contributes to the narrowing of the airways.

In such a situation, the supply of blood with oxygen decreases, from which the brain primarily suffers, therefore, the regulation of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems is disrupted. Also, when a child sleeps on his stomach, he can bury his nose in a mattress or pillow and block the airways.

In such a situation, the supply of blood with oxygen decreases, from which the brain primarily suffers, therefore, the regulation of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems is disrupted. Also, when a child sleeps on his stomach, he can bury his nose in a mattress or pillow and block the airways. - The use of soft duvets and blankets also contributes to overheating of the child.

- Tight swaddling hinders the movements of the child, restricts the mobility of the chest and respiratory movements, therefore it has long been recognized as harmful and dangerous in the light of the development of SIDS.

- It is recommended to wear knitted spiky woolen socks for the child, which, by irritating the reflexogenic zones, will prevent the infant from stopping breathing

- The best prevention of SIDS is breastfeeding the child. Breast milk protects against all diseases, and the physical effort that the baby spends on getting food strengthens and develops his respiratory system.

Infants who are formula fed early are at increased risk of sudden death

Infants who are formula fed early are at increased risk of sudden death - Regular massage and gymnastics contribute to the enrichment of blood with oxygen, improve metabolic processes, stimulate the development of the cerebral cortex, reducing the risk of developing SIDS to zero.

Emergency Apnea and Sudden Death Syndrome (for parents)

Every mother should know how to resuscitate chest compressions and mouth-to-mouth breathing to bring life back to an infant who has suddenly stopped breathing.

- Check the breathing rate by approaching the child's mouth and nose, trying to catch the movements of the chest.

- Check your skin tone. The pallor of the skin and the blue of the lips testify to the cessation of breathing.

- In the absence of breathing, stir up, wake up the baby, gently massage the hands, heels, rub the earlobes. In the vast majority of cases, this will be enough to restore breathing.

- If breathing does not appear, then make sure that there are no foreign objects in the trachea by opening the mouth and slightly tilting the child's head back.

- Immediately call an ambulance, before the arrival of which, help the baby by performing artificial respiration, and if there is no pulse on the manual artery, carefully start massaging the chest.

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: evolution of definitions, epidemiology and risk factors | Korableva

1. Filiano JJ, Kinney HC. A perspective on neuropathologic findings in victims of the sudden infant death syndrome: the triple-risk model. Biol Neonate. 1994;65(3–4):194–197. doi: 10.1159/000244052

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sudden Unexpected Infant Death and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/sids/aboutsuidandsids.htm. Accessed on 06/12/2021.

3. Mitchell EA, Krous HF. Sudden unexpected death in infancy: a historical perspective. J Pediatric Child Health. 2015;51(1): 108–112. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12818

4. Erck Lambert AB, Parks SE, Shapiro-Mendoza CK. National and State trends in Sudden Unexpected Infant Death: 1990–2015. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3):e20173519. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3519

Pediatrics. 2018;141(3):e20173519. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3519

5. Hauck FR, McEntire BL, Raven LK, et al. Research priorities in sudden unexpected infant death: An international consensus. Pediatrics. 2017;140(2):e20163514. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3514

6. Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Parks S, Lambert AE, et al. The Epidemiology of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and Sudden Unexpected Infant Deaths: Diagnostic Shift and other Temporal Changes. In: SIDS Sudden Infant and Early Childhood Death: The Past, the Present and the Future. Duncan JR, Byard RW, eds. Adelaide (AU): University of Adelaide Press; 2018. Ch. 13 Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513373. Accessed on 06/12/2021.

7. Byard RW. Sudden infant death syndrome - A "diagnosis" in search of a disease. J Clin Forensic Med. 1995;2(3):121–128. doi: 10.1016/1353-1131(95)

-9 8. Byard RW. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: Definitions. In: SIDS Sudden Infant and Early Childhood Death: The Past, the Present and the Future. Duncan JR, Byard RW, eds. Adelaide (AU): University of Adelaide Press; 2018. Ch. 1. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513393. Accessed on 06/12/2021.

Duncan JR, Byard RW, eds. Adelaide (AU): University of Adelaide Press; 2018. Ch. 1. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513393. Accessed on 06/12/2021.

9. Beckwith JB. Discussion of terminology and definition of the sudden infant death syndrome. In: Proceedings of the second international conference on causes of sudden death in infants. Bergman JB, Ray CG, eds. Washington: University of Washington Press; 1970.pp. 14–22.

10. Willinger M, James LS, Catz C. Defining the sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS): Deliberations of an expert panel convened by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Pediatric Pathol. 1991;11(5):677–684. doi: 10.3109/15513819109065465

11. Rambaud C, Guilleminault C, Campbell PE. Definition of the sudden infant death syndrome. BMJ. 1994;308(6941):1439. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6941.1439

12. Cordner SM, Willinger M. The definition of the sudden infant death syndrome. In: Sudden infant death syndrome. New Trends in the nineties. Rognum TO, ed. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press; 1995.pp. 17–20.

New Trends in the nineties. Rognum TO, ed. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press; 1995.pp. 17–20.

13. Mitchell EA, Becroft DMP, Byard RW, et al. Definition of the sudden infant death syndrome. BMJ. 1994;309(6954):607. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6954.607

14. Sturner WQ. SIDS redux: Is it or isn't it? Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1998;19(2):107–108. doi: 10.1097/00000433-199806000-00001

15. Krous HF, Beckwith JB, Byard RW, et al. Sudden infant death syndrome and unclassified sudden infant deaths: A definitional and diagnostic approach. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):234–238. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.234

16. Jensen LL, Rohde MC, Banner J, Byard RW. Reclassification of SIDS cases — A need for adjustment of the San Diego classification? Int J Leg Med. 2012;126(2):271–277. doi:10.1007/s00414-011-0624-z

17. Kelmanson I.A. The ratio of some functional indicators of children of the first year of life with a high risk of developing sudden death syndrome. Pediatrics. Journal them. G.N. Speransky. - 1989. - T. 68. - No. 9. - S. 111–113.

G.N. Speransky. - 1989. - T. 68. - No. 9. - S. 111–113.

18. Vorontsov I.M., Kelmanson I.A., Tsinzerling A.V. Syndrome of sudden infant death. - St. Petersburg: SpecLit; 1997. - 220 p.

19. Sterligov L.A., Goldberg N.D., Pishchulina V.G. et al. Prevention and prospects for studying home infant mortality // Pediatrics. Journal them. G.N. Speransky. - 1991. - T. 70. - No. 1. - S. 65–68.

20. Glukhovets B.I. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: methodological and pathogenetic variants of the diagnosis // Questions of modern pediatrics. - 2011. - T. 10. - No. 2. - S. 78–81.

21. Baranov A.A., Albitsky V.Yu., Namazova-Baranova L.S. Mortality of the child population in Russia: state, problems and tasks of prevention // Questions of modern pediatrics. - 2020. - T. 19. - No. 2. - S. 96–106. doi: 10.15690/vsp.v19i2.2102

22. Matturri L, Minoli I, Lavezzi AM, et al. Hypoplasia of medullary arcuate nucleus in unexpected late fetal death (stillborn infants): a pathologic study. Pediatrics. 2002;109(3):e43. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.3.e43

Pediatrics. 2002;109(3):e43. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.3.e43

23. Ottaviani G. Crib Death—Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). Sudden Infant and Perinatal Unexplained Death: The Pathologist's Viewpoint. 2nd ed. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer International Publishing; 2014.

24. Matturri L, Ottaviani G. Lavezzi AM. Techniques and criteria in pathologic and forensic-medical diagnostics in sudden unexpected infant and perinatal death. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;124(2):259–268. doi: 10.1309/6AR-EY41-HKBE-YVHX

25. Lavezzi AM, Piscioli F, Pusiol T, et al. Sudden intrauterine unexplained death: time to adopt uniform postmortem investigative guidelines? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):526. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2603-1

26. Ottaviani G. Defining Sudden Infant Death and Sudden Intrauterine Unexpected Death Syndromes with Regard to AnatomoPathological Examination. Front Pediatrician. 2016;4:103. doi: 10.3389/fped.2016.00103

27. Hauck FR, Tanabe KO. International trends in sudden infant death syndrome: stabilization of rates requires further action. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):660–666. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-0135

Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):660–666. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-0135

28. Taylor BJ, Garstang J, Engelberts A, et al. International comparison of sudden unexpected death in infancy rates using a newly proposed set of cause-of-death codes. Arch DisChild. 2015;100(11): 1018–1023. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-308949

29. Kryuchko D.S., Ryumina I.I., Chelysheva V.V. and others. Infant mortality outside medical institutions and ways to reduce it // Questions of modern pediatrics. - 2018. - T. 17. - No. 6. - S. 434-441. doi: 10.15690/vsp.v17i6.1973

30. Leach CE, Blair PS, Fleming PJ, et al. Epidemiology of SIDS and explained sudden infant deaths. Pediatrics. 1999;104(4):e43. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.4.e43

31. Rusen ID, Liu S, Sauve R, et al. Sudden infant death syndrome in Canada: trends in rates and risk factors, 1985–1998. Chronic Dis Can. 2004;25(1):1–6.

32. Blair PS, Sidebotham P, Berry PJ, et al. Major epidemiological changes in sudden infant death syndrome: A 20-year populationbased study in the UK. Lancet. 2006;367(9507):314–319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67968-3

Lancet. 2006;367(9507):314–319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67968-3

33. Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Kimball M, Tomashek KM, et al. US infant mortality trends attributable to accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed from 1984 through 2004: Are rates increasing? Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):533–539. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3746

34. Heron M. Deaths: Leading causes for 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;65(5):1–96.

35. Matthews TJ, MacDorman MF, Thoma ME. Infant mortality statistics from the 2013 period linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(9):1–30.

36. Moon RY, Hauck FR. risk factors and theories. In: SIDS Sudden Infant and Early Childhood Death: The Past, the Present and the Future. Duncan JR, Byard RW, eds. Adelaide (AU): University of Adelaide Press; 2018. Ch. 10. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513386. Accessed on 06/14/2021.

37. Goldberg N, Rodriguez-Prado Y, Tillery R, Chua C. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: A Review. Pediatrician Ann. 2018;47(3):e118–e123. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20180221-03

Pediatrician Ann. 2018;47(3):e118–e123. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20180221-03

38. Weese-Mayer DE, Berry-Kravis EM, Zhou L, et al. Sudden infant death syndrome: case-control frequency differences at genes pertinent to early autonomic nervous system embryologic development. Pediatric Res. 2004;56(3):391–395. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000136285.91048.4A

39. Cummings KJ, Klotz C, Liu WQ, et al. Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) in African Americans: polymorphisms in the gene encoding the stress peptide pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP). Acta Paediatr. 2009;98(3):482–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.01131.x

40. Tan BH, Pundi KN, Van Norstrand DW, et al. Sudden infant death syndrome-associated mutations in the sodium channel beta subunits. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7(6):771–778. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.01.032

41. Tfelt-Hansen J, Winkel BG, Grunnet M, Jespersen T. Cardiac channelopathies and sudden infant death syndrome. Cardiology. 2011;119(1):21–33. doi: 10.1159/000329047

doi: 10.1159/000329047

42. Tester DJ, Wong LCH, Chanana P, et al. Cardiac Genetic Predisposition in Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. J Am Call Cardiol. 2018;71(11):1217–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.01.030

43. Van Norstrand DW, Asimaki A, Rubinos C, et al. Connexin43 mutation causes heterogeneous gap junction loss and sudden infant death. circulation. 2012;125(3):474–481. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.057224

44. Korachi M, Pravica V, Barson AJ, et al. Interleukin 10 genotype as a risk factor for sudden infant death syndrome: determination of IL-10 genotype from wax-embedded postmortem samples. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;42(1):125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.06.008

45. Opdal SH, Opstad A, Vege A, Rognum TO. IL-10 gene polymorphisms are associated with infectious cause of sudden infant death. Hum Immunol. 2003;64(12):1183–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2003.08.359

46. Opdal SH, Rognum TO. The sudden infant death syndrome gene: does it exist? Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):e506–e512. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0683

2004;114(4):e506–e512. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0683

47. Van Norstrand DW, Ackerman MJ. Genomic risk factors in sudden infant death syndrome. Genome Med. 2010;2(11):86. doi: 10.1186/gm207

48. Hunt CE. Gene-environment interactions: implications for sudden unexpected deaths in infancy. Arch DisChild. 2005;90(1): 48–53. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.051458

49. Opdal SH, Vege A, Rognum TO. Serotonin transporter gene variation in sudden infant death syndrome. Acta Paediatr. 2008; 97(7):861–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00813.x

50. Nonnis Marzano F, Maldini M, Filonzi L, et al. Genes regulating the serotonin metabolic pathway in the brain stem and their role in the etiopathogenesis of the sudden infant death syndrome. Genomics. 2008;91(6):485–491. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.01.010

51. Klintschar M, Heimbold C. Association between a functional polymorphism in the MAOA gene and sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e756–e761. doi: 10.1542/peds. 2011-1642

2011-1642

52. Courts C, Grabmüller M, Madea B. Monoamine oxidase A gene polymorphism and the pathogenesis of sudden infant death syndrome. J Pediatr. 2013;163(1):89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.12.072

53. Opdal SH, Vege A, Stave AK, Rognum TO. The complement component C4 in sudden infant death. Eur J Pediatr. 1999;158(3): 210–212. doi: 10.1007/s004310051051

54. Goldstein RD, Kinney HC, Willinger M. Sudden unexpected death in fetal life through early childhood. Pediatrics. 2016; 137(6):e20154661. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4661

55. Kinney HC. Neuropathology provides new insight in the pathogenesis of the sudden infant death syndrome. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117(3):247–255. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0490-7

56. Kinney HC, Cryan JB, Haynes RL, et al. Dentate gyrus abnormalities in sudden unexplained death in infants: Morphological marker of underlying brain vulnerability. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129(1): 65–80. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1357-0

57. Miyagawa T, Sotero M, Avellino AM, et al. Apnea caused by mesial temporal lobe mass lesions in infants: Report of 3 cases. J Child Neurol. 2007;22(9):1079–1083. doi: 10.1177/0883073807306245

Miyagawa T, Sotero M, Avellino AM, et al. Apnea caused by mesial temporal lobe mass lesions in infants: Report of 3 cases. J Child Neurol. 2007;22(9):1079–1083. doi: 10.1177/0883073807306245

58. Leiter JC, Böhm I. Mechanisms of pathogenesis in the Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;159(2): 127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.05.014

59. Brownstein CA, Poduri A, Goldstein RD, et al. The Genetics of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. In: SIDS Sudden Infant and Early Childhood Death: The Past, the Present and the Future. Duncan JR, Byard RW, eds. Adelaide (AU): University of Adelaide Press; 2018. Ch. 31. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513378. Accessed on 06/14/2021.

60. Alessandri LM, Read AW, Stanley F, et al. Sudden infant death syndrome and infant mortality in aboriginal and non-aboriginal infants. J Pediatric Child Health. 1994;30(3):242–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1994.tb00626.x

61. Wilson CE. Sudden infant death syndrome and Canadian Aboriginals: Bacteria and infections. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1999;25(1–2):221–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01346.x

FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1999;25(1–2):221–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01346.x

62. Moon RY, Horne RS, Hauck FR. Sudden infant death syndrome. Lancet. 2007;370(9598):1578–1587. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61662-6

63. Anderson TM, Lavista Ferres JM, Ren SY, et al. Maternal Smoking Before and During Pregnancy and the Risk of Sudden Unexpected Infant Death. Pediatrics. 2019;143(4):e20183325. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3325

64. Duncan JR, Byard RW. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: An Overview. In: SIDS Sudden Infant and Early Childhood Death: The Past, the Present and the Future. Duncan JR, Byard RW, eds. Adelaide (AU): University of Adelaide Press; 2018. Ch. 2. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513399. Accessed on 06/14/2021.

65. Bada HS, Das A, Bauer CR, et al. Low birth weight and preterm births: Etiologic fraction attributable to prenatal drug exposure. J. Perinatol. 2005;25(10):631–637. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211378

66. Ostfeld BM, Schwartz-Soicher O, Reichman NE, et al. Prematurity and Sudden Unexpected Infant Deaths in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20163334. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3334

Ostfeld BM, Schwartz-Soicher O, Reichman NE, et al. Prematurity and Sudden Unexpected Infant Deaths in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20163334. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3334

67. Bigger HR, Silvestri JM, Shott S, Weese-Mayer DE. Influence of increased survival in very low birth weight, low birth weight, and normal birth weight infants on the incidence of sudden infant death syndrome in the United States: 1985–1991 J Pediatr. 1998;133(1):73–78. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70181-7. PMID: 9672514

68. Bhat RY, Hannam S, Pressler R, et al. Effect of prone and supine position on sleep, apneas, and arousal in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):101–107. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1873

69. Kassim Z, Donaldson N, Khetriwal B, et al. Sleeping position, oxygen saturation and lung volume in convalescent, prematurely born infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92(5): F347-F350. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.094078

70. Elder DE, Campbell AJ, Galletly D. Effect of position on oxygen saturation and requirement in convalescent preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(5):661–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02157.x

Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(5):661–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02157.x

71. Malloy MH. Size for gestational age at birth: impact on risk for sudden infant death and other causes of death, USA 2002. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92(6):F473-F478. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.107094

72. Getahun D, Amre D, Rhoads GG, Demissie K. Maternal and obstetric risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):646–652. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000117081.50852.04

73. Mitchell EA, Thach BT, Thompson JMD, Williams S. Changing infants’ sleep position increases risk of sudden infant death syndrome. Arch Pediatric Adolesc Med. 1999;153(11):1136–1141. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.11.1136

74. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Suffocation deaths associated with use of infant sleep positions o ners - United States, 1997–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(46):933–937.

75. Mitchell EA, Scragg L, Clements M. Soft cot mattresses and the sudden infant death syndrome. N Z Med J. 1996;109(1023):206–207.

Soft cot mattresses and the sudden infant death syndrome. N Z Med J. 1996;109(1023):206–207.

76. Erck Lambert AB, Parks SE, Cottengim C, et al. Sleep-Related Infant Suffocation Deaths Attributable to Soft Bedding, Overlay, and Wedging. Pediatrics. 2019;143(5):e20183408. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3408

77. Hauck FR, Herman SM, Donovan M, et al. Sleep environment and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome in an urban population: the Chicago Infant Mortality Study. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 Pt 2):1207–1214.

78. Rechtman LR, Colvin JD, Blair PS, Moon RY. Sofas and infant mortality. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):e1293–e1300. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1543

79. Doering JJ, Salm Ward TC. The Interface Among Poverty, Air Mattress Industry Trends, Policy, and Infant Safety. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):945–949. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303709

80. Moon RY. Air Mattresses Are Not Appropriate Sleep Spaces for Infants. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):838–839. doi: 10. 2105/AJPH.2017.303727

2105/AJPH.2017.303727

81. Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. SIDS and Other Sleep-Related Infant Deaths: Updated 2016 Recommendations for a Safe Infant Sleeping Environment. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5): e20162938. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2938

82. Thach BT, Rutherford GW Jr, Harris K. Deaths and injuries attributed to infant crib bumper pads. J Pediatr. 2007;151(3):271–274, 274.e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.028

83. Scheers NJ, Woodard DW, Thach BT. Crib Bumpers Continue to Cause Infant Deaths: A Need for a New Preventive Approach. J Pediatr. 2016;169:93–97.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.10.050

84. Vennemann MM, Hense HW, Bajanowski T, et al. Bed sharing and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome: can we resolve the debate? J Pediatr. 2012;160(1):44–48.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.06.052

85. Carpenter R, McGarvey C, Mitchell EA, et al. Bed sharing when parents do not smoke: is there a risk of SIDS? An individual level analysis of five major case-control studies. BMJ Open. 2013; 3(5):e002299. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002299

BMJ Open. 2013; 3(5):e002299. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002299

86. Moon RY. Task force on sudden infant death syndrome. SIDS and Other Sleep-Related Infant Deaths: Evidence Base for 2016 Updated Recommendations for a Safe Infant Sleeping Environment. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20162940. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2940

87. Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evid Rep Technol Assess (FullRep). 2007;(153):1–186.

88. Thompson JMD, Tanabe K, Moon RY, et al. Duration of Breastfeeding and Risk of SIDS: An Individual Participant Data Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;140(5):e20171324 doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1324

89. Psaila K, Foster JP, Pulbrook N, Jeffery HE. Infant pacifiers for reduction in risk of sudden infant death syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4(4):CD011147. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011147.pub2

90. Moro PL, Arana J, Cano M, et al. Deaths Reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, United States, 1997–2013.