Vitamin k supplement for newborns

FAQs About Vitamin K Deficiency Bleeding

Since 1961, the American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended supplementing low levels of vitamin K in newborns with a single shot of vitamin K given at birth. Low levels of vitamin K can lead to dangerous bleeding in newborns and infants. The vitamin K given at birth provides protection against bleeding that could occur because of low levels of this essential vitamin.

Below are some commonly asked questions and their answers. If you continue to have concerns about vitamin K, please talk to your pediatrician or healthcare provider.

Q: What is vitamin K, and how do low levels of vitamin K and vitamin K deficiency bleeding occur in babies?

A: Vitamin K is used by the body to form clots and to stop bleeding. Babies are born with very little vitamin K stored in their bodies. This is called “vitamin K deficiency” and means that a baby has low levels of vitamin K. Without enough vitamin K, babies cannot make the substances used to form clots, called ‘clotting factors.’ When bleeding happens because of low levels of vitamin K, this is called “vitamin K deficiency bleeding” or VKDB. VKDB is a serious and potentially life-threatening cause of bleeding in infants up to 6 months of age. A vitamin K shot given at birth is the best way to prevent low levels of vitamin K and vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB).

Q: Why do ALL babies need a vitamin K shot – can’t I just wait to see if my baby needs it?

A: No, waiting to see if your baby needs a vitamin K shot may be too late. Babies can bleed into their intestines or brain where parents can’t see the bleeding to know that something is wrong. This can delay medical care and lead to serious and life-threatening consequences. All babies are born with very low levels of vitamin K because it doesn’t cross the placenta well. Breast milk contains only small amounts of vitamin K. That means that ALL newborns have low levels of vitamin K, so they need vitamin K from another source. A vitamin K shot is the best way to make sure all babies have enough vitamin K. Newborns who do not get a vitamin K shot are 81 times more likely to develop severe bleeding than those who get the shot.

Breast milk contains only small amounts of vitamin K. That means that ALL newborns have low levels of vitamin K, so they need vitamin K from another source. A vitamin K shot is the best way to make sure all babies have enough vitamin K. Newborns who do not get a vitamin K shot are 81 times more likely to develop severe bleeding than those who get the shot.

Q: Doesn’t the risk of bleeding from low levels of vitamin K only last a few weeks?

A: No, VKDB can happen to otherwise healthy babies up to 6 months of age. The risk isn’t limited to just the first 7 or 8 days of life and VKDB doesn’t just happen to babies who have difficult births. In 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) investigated 4 cases of infants with bleeding from low levels of vitamin K. All four were over 6 weeks old when the bleeding started and they had been healthy and developing normally. None of them had received a vitamin K shot at birth.

Q: Isn’t VKDB really rare?

A: VKDB is rare in the United States, but only because most newborns get the vitamin K shot. Over the past two decades, many countries in Europe have started programs to provide vitamin K at birth – afterward, they all saw declines in the number of cases of VKDB to very low levels. However, in areas of the world where the vitamin K shot isn’t available, VKDB is more common, and many cases of VKDB have been reported from these countries

In the early 1980s in England, some hospitals started giving vitamin K only to newborns that were thought to be at higher risk for bleeding. They then noticed an increase in cases of VKDB. This tells us that giving vitamin K to prevent bleeding is what keeps VKDB a rare condition – when vitamin K is not given to newborns, cases of bleeding occur and VKDB stops being rare.

Q: What happens when babies have low levels of vitamin K and get VKDB?

A: Babies without enough vitamin K cannot form clots to stop bleeding and they can bleed anywhere in their bodies. The bleeding can happen in their brains or other important organs and can happen quickly. Even though bleeding from low levels of vitamin K or VKDB does not occur often in the United States, it is devastating when it does occur. One out of every five babies with VKDB dies. Of the infants who have late VKDB, about half of them have bleeding into their brains, which can lead to permanent brain damage. Others bleed in their stomach or intestines, or in other parts of the body. Many of the infants need blood transfusions, and some need surgeries.

The bleeding can happen in their brains or other important organs and can happen quickly. Even though bleeding from low levels of vitamin K or VKDB does not occur often in the United States, it is devastating when it does occur. One out of every five babies with VKDB dies. Of the infants who have late VKDB, about half of them have bleeding into their brains, which can lead to permanent brain damage. Others bleed in their stomach or intestines, or in other parts of the body. Many of the infants need blood transfusions, and some need surgeries.

Q: I heard that the vitamin K shot might cause cancer. Is this true?

A: No. In the early 1990s, a small study in England found an “association” between the vitamin K shot and childhood cancer. An association means that two things are happening at the same time in the same person, but doesn’t tell us whether one causes the other. Figuring out whether vitamin K might cause childhood cancer was very important because every newborn is expected to get a vitamin K shot. If vitamin K was causing cancer, we would expect to see the same association in other groups of children. Scientists looked to see if they could find the same association in other children, but this association between vitamin K and childhood cancer was never found again in any other study.

If vitamin K was causing cancer, we would expect to see the same association in other groups of children. Scientists looked to see if they could find the same association in other children, but this association between vitamin K and childhood cancer was never found again in any other study.

Q: Can the other ingredients in the shot cause problems for my baby? Do we really know that the vitamin K shot is safe?

A: Yes, the vitamin K shot is safe. Vitamin K is the main ingredient in the shot. The other ingredients make the vitamin K safe to give as a shot. One ingredient keeps the vitamin K mixed in the liquid; another keeps the liquid from being too acidic. One of the ingredients is benzyl alcohol, a preservative. Benzyl alcohol is a common ingredient in many medications.

In the 1980s, doctors recognized that very premature infants who were in neonatal intensive care units might become sick from benzyl alcohol toxicity because many of the medicines and fluids needed for their intensive care contained benzyl alcohol as a preservative. Although the toxicity was only reported for very premature infants, since then doctors have tried to minimize the amount of benzyl-alcohol-containing medications they give. Clearly, the small amount of benzyl alcohol in the vitamin K shot is not enough to be dangerous, even when given in combination with other medications that also contain small amounts of this preservative.

Although the toxicity was only reported for very premature infants, since then doctors have tried to minimize the amount of benzyl-alcohol-containing medications they give. Clearly, the small amount of benzyl alcohol in the vitamin K shot is not enough to be dangerous, even when given in combination with other medications that also contain small amounts of this preservative.

Q: The dose of the shot seems high. Is that too much for my baby?

A: No, the dose in the vitamin K shot is not too much for babies. The dose of vitamin K in the shot is high compared to the daily requirement of vitamin K. But remember babies don’t have much vitamin K when they are born and won’t have a good supply of vitamin K until they are close to six months old. This is because vitamin K does not cross the placenta and breast milk has very low levels of vitamin K.

The vitamin K shot acts in two ways to increase the vitamin K levels. First, part of the vitamin K goes into the infant’s bloodstream immediately and increases the amount of vitamin K in the blood. This provides enough vitamin K so that the infant’s levels don’t drop dangerously low in the first few days of life. Much of this vitamin K gets stored in the liver and it is used by the clotting system. Second, the rest of the vitamin K is released slowly over the next 2-3 months, providing a steady source of vitamin K until an infant has another source from his or her diet.

This provides enough vitamin K so that the infant’s levels don’t drop dangerously low in the first few days of life. Much of this vitamin K gets stored in the liver and it is used by the clotting system. Second, the rest of the vitamin K is released slowly over the next 2-3 months, providing a steady source of vitamin K until an infant has another source from his or her diet.

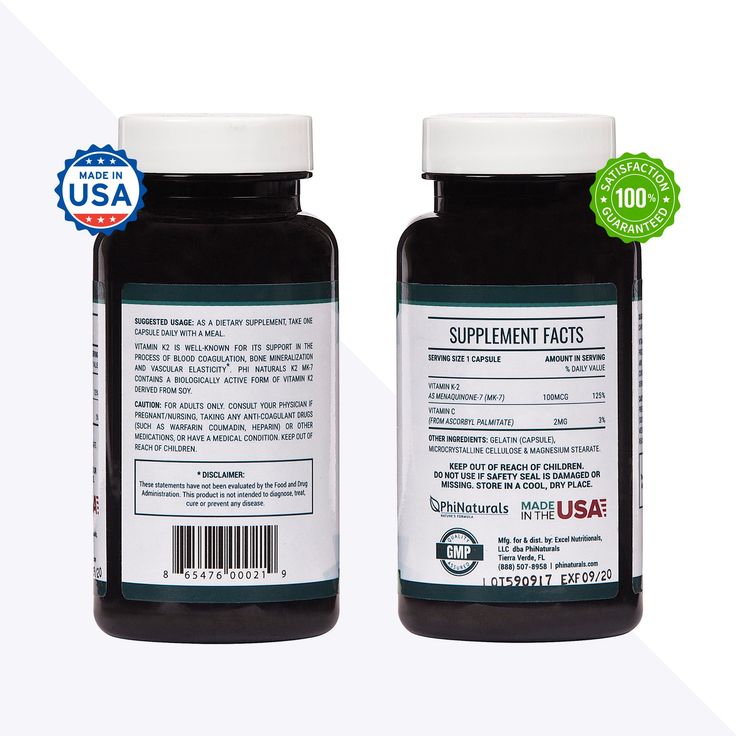

Q: Can I increase vitamin K in my breast milk by eating different foods or taking multivitamins or vitamin K supplements?

A: We encourage moms to eat healthy and take multivitamins as needed. Although eating foods high in vitamin K or taking vitamin K supplements can slightly increase the levels of vitamin K in your breast milk, neither can increase levels in breast milk enough to provide all of the vitamin K an infant needs.

When infants are born, their already low levels of vitamin K fall even lower. Infants need enough vitamin K to (a) make up for their extra-low levels, (b) start storing it in the liver for future use, and (c) ensure good bone and blood health. Breast milk – even from mothers supplementing with vitamin K sources – can’t provide enough to do all of these things.

Breast milk – even from mothers supplementing with vitamin K sources – can’t provide enough to do all of these things.

Q: My baby is so little. What can I do to make the vitamin K shot less painful and traumatic?

A: Babies, just like us, feel pain, and it is important to reduce even small amounts of discomfort. Babies feel less pain from shots if they are held and allowed to suck.You can ask to hold your baby while the vitamin K shot is given so that your baby can be comforted by you. Breastfeeding while the shot is given and immediately after can be comforting too. All of these are things parents can do to ease pain and soothe their baby.

Remember that if your baby does not get the vitamin K shot, his or her risk of developing severe bleeding is 81 times higher than if he or she got the shot. Diagnosis and treatment of VKDB often involves many painful procedures, including repeated blood draws.

Q: Overall, what are the risks and benefits of the vitamin K shot?

The risks of the vitamin K shot are the same risks that are part of getting most any other shot. These include pain or even bruising or swelling at the place where the shot is given. A few cases of skin scarring at the site of injection have been reported. Only a single case of allergic reaction in an infant has been reported, so this is extremely rare.

Although there have been concerns about some other risks, like a risk for childhood cancer or risks because of additional ingredients, none of these risks have been proven by scientific studies.

The main benefit of the vitamin K shot is that it can protect your baby from VKDB, a dangerous condition that can cause long-term disability or death. In addition, the diagnosis and treatment of VKDB often includes multiple and sometimes painful procedures, such as blood draws, CT scans, blood transfusions, or anesthesia and surgery.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended the Vitamin K shot since 1961, and has repeatedly stood by that recommendation because the risks of the shot don’t outweigh the risks of VKDB, which are based on decades of evidence and decades of experience with babies who were hospitalized or died from VKDB.

Your child’s doctor is the best person to talk to about vitamin K. Like you, your child’s doctor wants to see your children grow up safe and healthy and wants to support your efforts to make the best decisions for their health. If you have concerns about vitamin K, talk to your child’s doctor.

Vitamin K at birth | Pregnancy Birth and Baby

Vitamin K at birth | Pregnancy Birth and Baby beginning of content5-minute read

Listen

Key facts

- Vitamin K helps your baby’s blood to clot.

- Babies need more vitamin K than they get from their mother during pregnancy or from breast milk.

- Parents of all newborns are offered a vitamin K injection for their baby soon after birth.

- This helps prevent babies from becoming vitamin K deficient.

- Without the injection, they are at risk of developing a condition called Vitamin K Deficiency Bleeding (known as VKDB).

What is vitamin K?

Vitamin K is an essential vitamin, and has an important role in maintaining good health by helping blood to clot. Vitamin K helps prevent serious bleeding.

Why is vitamin K important for my baby?

Vitamin K helps your baby’s blood clot and prevents serious bleeding. Babies do not get enough vitamin K naturally from their mother during pregnancy. Breast milk also does not provide babies with enough levels of vitamin K. This can result in vitamin K deficiency in newborns.

If your baby has vitamin K deficiency, they are at risk of developing a disease called Vitamin K Deficiency Bleeding, or VKDB. While VKDB is rare, it can be very serious as it can cause babies to bleed excessively and may cause them to bleed into their brain. This condition may result in brain damage and even death.

While VKDB is rare, it can be very serious as it can cause babies to bleed excessively and may cause them to bleed into their brain. This condition may result in brain damage and even death.

How is vitamin K given?

Vitamin K is usually given as a single injection in your baby’s leg muscle shortly after birth. If you prefer that your baby does not get an injection, they can have liquid vitamin K drops into their mouth. It is important to note that oral vitamin K drops are not absorbed as well by the body than injected vitamin K, so 3 doses of oral vitamin K are needed. The first dose is given at birth, the second at 3 to 5 days of age and the third when they are 4 weeks old.

Vitamin K injections are preferred over the oral drops for all babies. Some babies aren’t able to have oral vitamin K, such as if the mother was taking certain medications while pregnant, or if your baby is premature, unwell, taking antibiotics or has diarrhoea.

Can all babies have vitamin K?

Yes, all babies can have vitamin K. If your baby is premature or very small, they might need a smaller dose of vitamin K. You can discuss this with your doctor.

If your baby is premature or very small, they might need a smaller dose of vitamin K. You can discuss this with your doctor.

How much does vitamin K cost?

Vitamin K injections or drops are free. The cost is covered by the government for all babies born in Australia.

Does vitamin K have any side effects? What should I look out for?

Vitamin K in newborns is not associated with any side effects, and has been given to Australian babies for more than 30 years. Studies have investigated whether there is an association between injected vitamin K and childhood cancers. Doctors and scientists have concluded that vitamin K injections are safe and beneficial for babies, and that there is no link between vitamin K and childhood cancer.

If your baby has not had a vitamin K injection or the full 3-dose course of vitamin K oral drops it is important that you look out for:

- unexplained bleeding or bruising

- showing signs of jaundice after they are 3 weeks old

If they show any of these symptoms, see your doctor or midwife immediately.

If your baby has liver problems, they may be at a higher risk of bleeding, even if they have had their recommended dose of vitamin K.

Does my baby need to have vitamin K?

It is your choice whether to give your baby vitamin K or not. However, giving vitamin K to your newborn is an easy way to prevent a very serious disease. Health authorities in Australia and throughout the world recommend giving vitamin K to all newborn babies — even babies who were born prematurely or are sick.

How do I get vitamin K for my baby?

During your pregnancy your doctor or midwife will talk to you about vitamin K, including the pros and cons of giving your baby vitamin K by injection or by mouth. Your doctor or midwife will then note this on your file. Your baby will receive vitamin K soon after birth by a doctor or a midwife, based on your decision.

If you have chosen to give your baby vitamin K by mouth then your baby will need to receive 2 more doses after the dose they receive at birth. The second dose can be given in hospital at the same time as your baby has their newborn screening test, or by your local doctor or healthcare worker. It is important to remember to arrange your baby’s third dose when they are 4 weeks old. This important final dose can also be given by your doctor or health care worker.

The second dose can be given in hospital at the same time as your baby has their newborn screening test, or by your local doctor or healthcare worker. It is important to remember to arrange your baby’s third dose when they are 4 weeks old. This important final dose can also be given by your doctor or health care worker.

If you are having a home birth, be sure to discuss giving your baby vitamin K with your midwife. Homebirth midwives are required to have all essential equipment available for a planned home birth, including vitamin K injections.

Sources:

Australian Government, National Health and Medical Research Council (Vitamin K for Newborn Babies), South Australian Neonatal Medication Guidelines (Vitamin K), NSW Health (Having a baby - Labour and birth), SA Health (Planned Birth at Home in SA. 2018 Clinical Directive), The Royal Women Hospital Australia (Tests and Medicines for Newborn Babies)Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Last reviewed: June 2022

Back To Top

Related pages

- Baby's first 24 hours

- Your baby in the first few days

Need more information?

Vitamin K for newborns | NHMRC

Vitamin K helps blood to clot and is essential in preventing serious bleeding in infants. Vitamin K deficiency bleeding can be prevented by the administration of vitamin K soon after birth. By the age of approximately six months, infants have built up their own supply of vitamin K.

Read more on NHMRC – National Health and Medical Research Council website

Vitamin K and newborn babies - Better Health Channel

With low levels of vitamin K, some babies can have severe bleeding into the brain, causing significant brain damage.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

At birth | Sharing Knowledge about Immunisation | SKAI

Most babies get two needles (injections) at birth. One is the hepatitis B vaccine and the other is a vitamin K injection. They are usually given in babies’ legs.

Read more on National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance (NCIRS) website

Children and vitamins

Very few kids actually need to take vitamin and mineral supplements, they can get everything they need from a balanced diet.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Vitamin and mineral supplements - what to know - Better Health Channel

Vitamin and mineral supplements are frequently misused and taken without professional advice. Find out more about vitamin and mineral supplements and where to get advice.

Find out more about vitamin and mineral supplements and where to get advice.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

Vitamins & minerals for kids & teens | Raising Children Network

Children need vitamins and minerals for health and development. They can get vitamins and minerals by eating a variety of foods from the five food groups.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Itching during pregnancy

Mild itching is common in pregnancy because of the increased blood supply to the skin, but if the itching becomes severe it can be a sign of a liver condition called 'obstetric cholestasis'.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Baby's first 24 hours

There is a lot going on in the first 24 hours of your baby's life, so find out what you can expect.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

ACD A-Z of Skin - Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy

A-Z OF SKIN Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy BACK TO A-Z SEARCH What is it? Also known as … Recurrent Cholestasis of Pregnancy, Obstetric Cholestasis, Cholestasis of Pregnancy, Recurrent Jaundice of Pregnancy, Cholestatic Jaundice of Pregnancy, Idiopathic Jaundice of Pregnancy, Prurigo gravidarum, Icterus Gravidarum What is it? Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is a rare liver condition which causes an itchy skin

Read more on Australasian College of Dermatologists website

Pregnancy at week 40

Your baby will arrive very soon – if it hasn't already. Babies are rarely born on their due date and many go past 40 weeks.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Disclaimer

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is not responsible for the content and advertising on the external website you are now entering.

Need further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Video call

- Contact us

- About us

- A-Z topics

- Symptom Checker

- Service Finder

- Subscribe to newsletters

- Sign in

- Linking to us

- Information partners

- Terms of use

- Privacy

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is funded by the Australian Government and operated by Healthdirect Australia.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby’s information and advice are developed and managed within a rigorous clinical governance framework.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Healthdirect Australia acknowledges the Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia and their continuing connection to land, sea and community. We pay our respects to the Traditional Owners and to Elders both past and present.

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

Vitamin K-deficient hemorrhagic syndrome in newborns and children in the first months of life

Summary

The article is devoted to hemorrhagic disease of the newborn (HRD). Data on the biological role of vitamin K and its metabolism in newborns are presented. The frequency of development, causes and clinical symptoms of the early, classical and late forms of the disease are presented. Based on a review of domestic and foreign publications, the issues of laboratory diagnosis, prevention and treatment of HRD are considered. Given the risk of developing life-threatening bleeding, emphasis was placed on the need for maximum coverage of newborns with prophylactic administration of vitamin K in accordance with the Clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hemorrhagic disease of the newborn, developed by the Association of Neonatologists (2015). A clinical case of the development of a late form of HRD in a child who was exclusively breastfed and did not receive vitamin K for prevention after birth is described.

Based on a review of domestic and foreign publications, the issues of laboratory diagnosis, prevention and treatment of HRD are considered. Given the risk of developing life-threatening bleeding, emphasis was placed on the need for maximum coverage of newborns with prophylactic administration of vitamin K in accordance with the Clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hemorrhagic disease of the newborn, developed by the Association of Neonatologists (2015). A clinical case of the development of a late form of HRD in a child who was exclusively breastfed and did not receive vitamin K for prevention after birth is described.

Keywords: hemorrhagic disease of the newborn, vitamin K Deficiency hemorrhagic syndrome, newborns, vitamin K

Neonatology: news, opinions, education. 2015. No. 3. S. 74-82.

Hemorrhagic disease of the newborn (HrDN) (ICD-10 code - P53), or vitamin K-deficient hemorrhagic syndrome, is a disease manifested by increased bleeding in newborns and children in the first months of life due to insufficient blood coagulation factors (II, VII, IX, X), whose activity depends on vitamin K.

The term "hemorrhagic disease of the newborn" was coined in 1894 (Townsend, 1894) to refer to bleeding in newborns not associated with traumatic exposure or hemophilia. More recently, vitamin K deficiency has been shown to be the cause of many of these bleedings, leading to the more accurate term being "vitamin K deficiency bleeding" (VKDB) [1].

The biological role of vitamin K and its metabolism in newborns

The biological role of vitamin K is to activate gamma-carboxylation of glutamic acid residues in prothrombin (factor II), proconvertin (factor VII), antihemophilic globulin B (factor IX) and Stuart-Prower factor (factor X), as well as in antiproteases plasma C and S, which play an important role in the anticoagulant system.

With a lack of vitamin K in the liver, there is a synthesis of inactive decarboxylated forms of K-dependent factors that are unable to bind calcium ions and fully participate in blood coagulation (PIVKA - protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonism) [2-4]. In studies, the determination of the level of PIVKA-II, a decarboxylated form of prothrombin, is usually used.

In 1929, the Danish biochemist H. Dam isolated a fat-soluble vitamin, which in 1935 was named vitamin K, but to date, the pathways of vitamin K metabolism have not been fully understood.

The main source of supply for the body is vitamin K of plant origin, which is called vitamin K1, or phylloquinone. It comes from food - green vegetables, vegetable oils, dairy products. Another form of vitamin K, vitamin K2, or menaquinone, is of bacterial origin. Vitamin K2 is mainly synthesized by the intestinal microflora. The role of vitamin K2 has been studied very little. Its largest amount is located inside bacterial membranes and, possibly, is poorly absorbed. It is believed that vitamin K2 is of little importance to the body. It is known that the deposition of vitamin K occurs in the form of menaquinone-4 (MK-4) in the pancreas, salivary glands, and brain. Currently, research is underway to study the metabolic pathways of various forms of vitamin K. One of the ways to convert vitamins K1 and K2 into a deposited form is their metabolization in the intestine into an intermediate substance - menadione (vitamin K3). Then, from the menadione circulating in the blood, the deposited form of menaquinone-4 is synthesized in the extrahepatic tissues [4-7].

All newborns are relatively deficient in vitamin K. The transfer of vitamin K1 across the placenta is extremely limited. The maternal-fetal gradient for vitamin K1 is 30:1, as a result of which the concentration of vitamin K in the blood of the fetus and its reserves at the time of birth are extremely small. Cord blood vitamin K1 levels range from very low (<2 mg/mL) to undetectable. Vitamin K2 in the liver of newborns is practically not detected or occurs in extremely low quantities. This form of vitamin begins to accumulate gradually during the first months of life. It may be that breastfeeding infants accumulate vitamin K2 more slowly because of their predominant gut microflora ( Bifidumbacterium , Lactobacillus ) does not synthesize vitamin K2.

Bacteria that produce vitamin K2 - Bacteroides fragilis , E. coli , are more common in children receiving artificial milk formulas [1, 4, 8].

At the same time, in 10-52% of newborns in the umbilical cord blood, an increased level of PIVKA-II is determined, indicating a deficiency of vitamin K, and by the 3-5th day of life, a high level of PIVKA-II is found in 50-60% of children, who are breastfed and have not received prophylactic administration of vitamin K [4, 9, 10]. Thus, for newborns, the only source of vitamin K is its exogenous intake: with human milk, artificial nutritional formula, or in the form of a drug.

It is known that HrDN develops more often in breastfed children, since the content of vitamin K1 in breast milk is much lower than in artificial milk formulas, usually <10 µg/l [4]. While artificial milk formulas for full-term babies contain about 50 µg/l of vitamin K, and mixtures for premature babies contain up to 60-100 µg/l.

Classification of hemorrhagic disease of the newborn

There are 3 forms of HRD depending on the age of symptom onset: early , classical and late .

Bleeding in all forms of the disease is based on vitamin K deficiency. However, the risk factors and causes of symptoms differ in different forms.

Early HRD

Not well studied. Occurs rarely. Manifests during the first 24 hours of a child's life.

As a rule, the cause of the development of the early form of HRD is the maternal use during pregnancy of drugs that disrupt the metabolism of vitamin K, such as indirect anticoagulants (warfarin, phenindione), anticonvulsants (barbiturates, carbamazepine, phenytoin), anti-TB drugs (isoniazid, rifampicin ).

The incidence of this form in children whose mothers received these drugs during pregnancy without vitamin K supplements reaches 6-12% [1, 11]. In general, the frequency of the early form of HRD, according to a 6-year follow-up in Switzerland from 2005 to 2011, was 0.22 per 100,000 [12].

In the early form, bleeding of any localization, including in the brain, is possible. Bleeding associated with birth trauma is typical [9, 13]. It is believed that this form of the disease usually cannot be prevented by the prophylactic administration of vitamin K after childbirth [1, 14].

Classical form of HRD

Manifested by bleeding on the 2-7th day of life.

In addition to the above reasons for vitamin K deficiency in the fetus and newborn, there are 2 more important reasons for the development of this form: 1) lack of prophylactic use of vitamin K immediately after birth and 2) insufficient milk supply.

Gastrointestinal bleeding, skin hemorrhage, bleeding from injection/invasion sites, umbilical cord, and nose are common. Intracranial hemorrhages are less typical [2, 9, 15].

The estimated incidence of classical HRD without vitamin K prophylaxis is 0.25-1.5%. Prophylactic administration of vitamin K immediately after the birth of a child makes it possible to practically eliminate this form of HRD [1, 12].

Late form of HRD

It is diagnosed in cases of development of bleeding symptoms in the period from the 8th day to the 6th month of life, although, as a rule, the manifestation occurs at the age of 2-12 weeks [1, 2, 9, 14, 16].

There are 3 main groups of children who are at risk of developing a late form of HRD.

The first group consists of children with vitamin K deficiency: exclusively breastfed and not receiving vitamin K prophylaxis after birth [12, 14, 17].

Group 2 includes children with malabsorption of vitamin K in the gastrointestinal tract. This condition is observed in cholestatic and intestinal diseases accompanied by malabsorption (diarrhea for more than 1 week, cystic fibrosis, short bowel syndrome, celiac disease) [1, 18, 19].

Group 3 includes children receiving long-term parenteral nutrition with inadequate vitamin K supply. or death [1, 11, 20-22].

In some children, some time before a cerebral hemorrhage (from a day to a week), small "warning" hemorrhages are observed [16, 17, 23, 24].

Without the prophylactic use of vitamin K immediately after the birth of a child, the frequency of the late form of HRD is in the range of 5-20 per 100,000 newborns. Intramuscular prophylactic administration of vitamin K can significantly reduce the frequency of the late form, virtually eliminating the possibility of its development in children without cholestasis and malabsorption [1, 12, 25, 26]. under conditions of triple oral prophylactic administration of a water-soluble form of vitamin

K (2 mg on the 1st, 4th day and 4 weeks) showed that the frequency of the late form is 0.87 per 100 thousand, while all cases of late bleeding appeared in children who are breastfed and with cholestatic disease. The development of the classical form is not registered [12].

Laboratory signs of HRD

Laboratory signs of HRD are primarily changes in prothrombin tests: prolongation of prothrombin time (PT), decrease in prothrombin index (PTI), increase in international normalized ratio (INR). A significant change in prothrombin tests is characteristic - 4 times or more. In more severe cases, prolongation of the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) is added [11, 23, 27, 28].

Fibrinogen levels, platelets, thrombin time, as a rule, does not change. However, with massive bleeding and critical conditions, these indicators can also become pathological, which is more often observed in the late form of HRD.

Diagnosis is confirmed by normalization of prothrombin tests and cessation of bleeding after administration of vitamin K [15, 17, 20, 27]. According to Russian authors, complex treatment of the late form of HRD (administration of menadione and fresh frozen plasma) leads to normalization of prothrombin tests within 6-8 to 18-24 hours [17, 24].

When evaluating a coagulogram, it must be taken into account that the normative values of hemostasis in newborns and children in the first months of life differ from the reference values in adults and are subject to significant changes immediately after birth. And premature babies have their own peculiarities of hemostasis depending on gestational age, characterized by a significant range of values. Newborns and premature babies are characterized by a hypocoagulable orientation of the plasma-coagulation link of hemostasis against the background of an increase in intravascular blood coagulation and fibrinolysis activity [an increase in the level of fibrin degradation products (FDP) and D-dimers] [28-34].

The absolute values of hemostasis parameters depend on the reagent and analyzer, therefore it is recommended that each laboratory determine its own reference values for newborns and premature infants in accordance with the methodology used [34, 35].

Determination of vitamin K is not of diagnostic value due to its low concentration in newborns [11].

The level of PIVKA-II can help in the diagnosis of latent vitamin K deficiency, however, it is not classified as the main diagnostic marker of HrDN in practice and is mainly used in scientific papers [4, 9].

Treatment of HrDN

Based on the principles of hemorrhage control and elimination of vitamin K deficiency.

Any child with suspected HrDN should be given vitamin K immediately, without waiting for laboratory confirmation. In the Russian Federation, the vitamin K preparation is menadione sodium bisulfite (Vikasol) - a water-soluble synthetic analogue of vitamin K3. It must be taken into account that its action begins after 8-24 hours.

In case of ongoing and life-threatening bleeding, fresh frozen plasma is indicated, 36]. Instead of plasma, it is possible to use a concentrated preparation of the prothrombin complex [2, 9, 37]. Its administration should be monitored due to the risk of thromboembolic complications [38].

HrDN prevention

HrDN prevention is a priority for neonatal and pediatric services.

To increase the concentration of vitamin K in the body of a pregnant woman and in breast milk, a woman is recommended a diet using foods rich in vitamin K1, as well as taking multivitamin complexes [4, 13, 15].

Pregnant women who take drugs that interfere with vitamin K metabolism during pregnancy are recommended to take additional vitamin K: in the III trimester at a dose of 5 mg/day or 2 weeks before delivery at a dose of 20 mg/day [1, 14]. However, all these measures are not considered sufficient for the full prevention of all forms of HRD.

Taking into account the physiology of the coagulation system and vitamin K metabolism in newborns, in developed countries, prophylactic administration of a vitamin K preparation to all newborns is accepted, while from 1960s only vitamin K1 preparations are used. Studies conducted so far have shown that menadione has an oxidizing effect on fetal hemoglobin, leading to hemolysis, the formation of methemoglobin and Heinz bodies in erythrocytes, which is associated with impaired glutathione metabolism against the background of insufficient antioxidant protection in newborns and, especially, in premature babies. The toxic effect of menadione has been identified when using high doses (more than 10 mg) [4, 15, 39, 40].

Prophylactic use of vitamin K1 preparations has been shown to be effective in numerous studies. It is believed that a single parenteral administration of vitamin K1 after the birth of a child is sufficient to prevent the classic and late forms of HRD in children who do not have symptoms of cholestasis and malabsorption. In some countries, enteral supplementation of vitamin K1 is used for the same purpose, but in these cases it is necessary to take several doses of vitamin K1 orally according to certain schemes. In the presence of cholestasis syndrome or malabsorption, the child will need additional administration of vitamin K [1, 11, 16, 20, 27, 41, 42].

Taking into account the lack of vitamin K1 currently registered in the Russian Federation, for the prevention of vitamin K-deficient hemorrhagic syndrome in our country, intramuscular administration of a 1% solution of menadione sodium bisulfite is used, which is administered in the first hours after birth. During surgical interventions in newborns with possible severe parenchymal bleeding, as well as in children with cholestasis or malabsorption syndrome, additional administration of vitamin K is necessary (see figure).

The efficacy of menadione can be considered proven for the prevention of the classic form of HRD in full-term infants, since many studies have yielded identical results: the administration of menadione intramuscularly (including at a dose of 1 mg) led to a significant increase in PTI, a decrease in APTT, PT , the level of PIVKA-II, a decrease in the frequency of bleeding, while toxic effects were not registered [27, 29, 43, 44].

The high frequency of intracranial hemorrhages in late form of hemorrhagic disease in children who are exclusively breastfed makes the prevention of this form particularly relevant. Numerous foreign studies have shown the effectiveness of a single parenteral administration of vitamin K1 immediately after the birth of a child to prevent this form of the disease. There are practically no studies on the effectiveness of menadione for the prevention of the late form of HRD in the modern literature, which is to some extent explained by what happened in 1960s in many countries by replacing it with a vitamin K1 preparation. Nevertheless, there are few publications in the domestic literature that indicate that the cases of the late form of HRD developed in exclusively breastfed children who did not receive prophylactic administration of menadione in the maternity hospital.

One of the publications presents an analysis of 9 cases of late hemorrhagic disease accompanied by intracranial hemorrhages. The disease developed in children aged 1 month to 2 months 20 days, who were breastfed and did not have a serious somatic pathology. The disease ended unfavorably in 7 (78%) patients: death occurred in 6 children, disability - in 1. The authors try to draw attention to the fact that none of the patients received prophylactic administration of vitamin K in the maternity hospital [17].

Another review presents an analysis of 34 cases of late HRD with intracranial hemorrhage.

The disease manifested from the 3rd to the 8th week. All children were breastfed and did not receive vitamin K prophylaxis [24].

Clinical case of late form of HRD

Boy D . was born from the 3rd pregnancy (1st - frozen, 2nd - delivery on time, the child is healthy), proceeding without features, from 2 births at 39week with body weight 2820 g, height 50 cm. Apgar score was 9/10 points. Attached to the breast in the delivery room. Vaccinated with BCG and hepatitis B vaccine at the maternity hospital. Vitamin K was not administered prophylactically. He was discharged from the maternity hospital in a satisfactory condition with a bilirubin level of 200 µmol/l. Was breastfed. During the first month, he gained 500 g in weight.

At the 2-3rd week of life, there was a slight umbilical bleeding, he did not receive treatment. At the age of 27 days, there was a slight bloody discharge from the nose and a hemorrhagic crust in the nose. The next day, at the age of 28 days, the mother noticed a small hematoma in the child on the back under the shoulder blade, about 1.5 cm in size. In the morning at 29On the 1st day of life, a single vomiting was noted, the child did not suckle well, was restless, tucked up his legs. The doctor on duty at the polyclinic diagnosed intestinal colic.

By evening the child became lethargic, pale, vomiting was observed. On the morning of the 30th day of life, due to the progressive deterioration of his condition, he was hospitalized with a diagnosis of prolonged jaundice, intestinal colic, hydrocephalic syndrome.

Upon admission to the hospital. The condition is extremely difficult. Body temperature 38 °C. The child practically did not react to examination. There was a decortication posture, pronounced hyperesthesia, an irritated monotonous cry, bulging of the large fontanel, anisocoria on the right, the skin was of a pale icteric color, on the back there was a hematoma 1.8-2.0 cm in diameter, the subcutaneous fat layer was thinned, tachycardia was noted. On other bodies - without visible deviations.

Examination data

In the clinical blood test: Hb 99 g/l, erythrocytes 2.71×1012/l, platelets 165×109/l. In a biochemical blood test: total protein 57 g/l, total bilirubin 227 µmol/l, direct 16.1 µmol/l, glucose 5.1 mmol/l, ALT 12 U/l, AST 13.4 U/l.

Coagulogram. Conclusion: hypocoagulation associated with a deficiency of K-dependent coagulation factors (see table).

Based on the anamnesis, clinical picture and additional examination, the diagnosis of HRD (vitamin K-deficient bleeding), late form was established.

Intraventricular hemorrhage III degree. Posthemorrhagic anemia.

The main diagnosis was treated: vikasol 1 mg/kg 1 r/day for 3 days, dicynone, two transfusions of fresh frozen plasma, transfusion of erythrocyte mass.

During treatment 1 day after admission, the coagulogram parameters returned to normal (see table)

1 month later, due to the development of occlusive tetraventricular hydrocephalus, the child was transferred to a neurosurgical hospital, where he underwent ventriculoperitoneal shunting.0003

Conclusion

HrDN is a serious disease that can lead to death or disability, especially if it develops in a late form. It should be taken into account that the formation of severe intracranial hemorrhages in the late form of HRD can be prevented by timely prophylaxis.

The accumulated experience convinces of the need for prophylactic administration of vitamin K preparations to all newborns in the first hours after birth and to maintain vigilance for the late form of HRD.

In this regard, in 2015, the Association of Neonatologists developed clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of HRD. A scheme for the prevention of HRD has also been proposed [36]. Unfortunately, in the Russian Federation, 100% routine HRD prevention is difficult to implement, since hemolytic disease in a newborn is an official contraindication for prescribing the only vitamin K drug registered in our country, menadione; its appointment in this group of children is possible only if there are serious arguments (see figure).

Prevention of the late form of HRD should include the administration of vitamin K in the maternity hospital and maintaining vigilance for this disease in children of the first six months of life from high-risk groups: those who are breastfed, those with cholestasis syndrome and malabsorption syndrome. In this regard, the appearance of hemorrhages in children during the first months of life requires immediate differential diagnosis and the exclusion of vitamin K-deficient bleeding.

These warning hemorrhages include:

✧ epistaxis;

✧ bleeding from the umbilical wound;

✧ petechiae and ecchymosis of the skin or mucous membranes;

✧ intermuscular hematomas or bleeding from invasive intervention sites (injections, vaccinations, blood sampling sites, circumcisions, operations).

If HRD is suspected, menadione should be given immediately to avoid life-threatening bleeding.

After the registration of vitamin K1 in Russia, clinical guidelines for the prevention and treatment of vitamin K-deficiency bleeding in children will be revised and the use of vitamin K1 preparations will be recommended.

REFERENCES

1. NHMRC (National Health and Medical Research Council) (2010). Joint statement and recommendations on Vitamin K administration to newborn infants to prevent vitamin K deficiency bleeding in infancy - October 2010 (the Joint Statement). Commonwealth of Australia. www.ag.gov.au/cca. ISBN Online: 1864965053.

2. Neonatology. National leadership. Brief edition / ed. acad. RAMN N.N. Volodin. M.: GEOTAR-Media, 2013. 896 p.

3. Joshi A., Jaiswal J.P. Deep vein thrombosis in protein S deficiency // J. Nepal. Med. Assoc. 2010 Vol. 49. P. 56-58.

4. Greer F.R. Controversies in neonatal nutrition: macronutrients and micronutrients. In: Gastroenterology and nutrition: neonatology question and controversies. 2nd ed. by Neu J. Philadelphia: Elsevier saunders, 2012, pp. 129-155.

5. Card D. J., Gorska R. et al. Vitamin K metabolism: Current knowledge and future research // Mol. Nutr. food res. 2014. Vol. 58. P. 1590-1600.

6. Thijssen K.H.W., Vervoort L.M.T. et al. Menadione is a metabolite of oral vitamin // Br. J. Nutr. 2006 Vol. 95. P. 260-266.

7. Sharer M.J., Newman P. Recent trends in the metabolism and cell biology of vitamin K with special reference to vitamin K cycling and MK-4 biosynthesis // J. Lipid Res. 2014. Vol. 55, No. 3. P. 345-362.

8. Thureen P.J., Hay W.W. Neonatal Nutrition and Metabolism. 2nd Ed. Jr. Cambridge University Press. 2006.

9. Gomella T.L. Neonatology: Management, Procedures, On-Call Problems, Diseases, and Drugs. McGraw Hill. 2013.

10. von Kries R., Kreppel S., Becker A., Tangermann R., Gobel U. Acarboxyprothrombin concentration (corrected) after oral prophylactic vitamin K // Arch. Dis. child. 1987 Vol. 62. P. 938-940.

11. Nimavat D.J. Hemorrhagic Disease of Newborn. Updated: Sep 26, 2014. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/974489-overview.

12. Laubscher B., Banziger O., Schubiger G., the Swiss Pediatric Surveillance Unit (SPSU). Prevention of vitamin K deficiency bleeding with three oral mixed micellar phylloquinone doses: results of a 6-year (2005-2011) surveillance in Switzerland // Eur. J. Pediatr. 2013. Vol. 172. P. 357-360.

13. Shearer M.J. Vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) in early infancy // Blood. Rev. 2009 Vol. 23. P. 49-59.

14. Burke C. W. Vitamin K Deficiency Bleeding // J. Pediatr Health Care. 2013. Vol. 27, No. 3. P. 215-221.

15. Shabalov N.P. Neonatology. 5th ed., rev. and additional, in 2 vols. M.: MEDpress-inform, 2009. 1504 p. (in Russian)

16. Schulte R., Jordan L.C., Morad A., Naftel R.P., Wellons J.C., Sidonio R. Rise in late onset vitamin K deficiency in young infants because of omission or refusal of prophylaxis at Birth // Pediatric Neurology. 2014. Vol. 50. P. 564-568.

17. Lobanov A.I., Lobanova O.G. Hemorrhagic disease of the newborn with late onset. Questions of modern pediatrics. 2011. No. 1. S. 167-171.

18. Feldman A.G., Sokol R.J. Neonatal cholestasis // Neoreviews. 2013. Vol. 14, No. 2. e63.

19. van Hasselt P.M., de KoningT.J., KvistN. et al. Prevention of Vitamin K Deficiency Bleeding in Breastfed Infants: Lessons From the Dutch and Danish Biliary Atresia Registries. Pediatrics. 2008 Vol. 121, No. 4. e857-e863.

20. Notes from the field: late vitamin K deficiency bleeding in infants whose parents declined vitamin K prophylaxis // Tennessee. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013. Vol. 15, No. 62 (45). P. 901-902.

21. Volpe J.J. Neurology of the Newborn. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2008. 1094 p.

22. Volpe J.J. Intracranial Hemorrhage in Early Infancyd Renewed Importance of Vitamin K Deficiency // Pediatric Neurology. 2014. Vol. 50. P. 545-6.

23. Ursulenko E.V., Martynovich N.N., Tolmacheva O.P., Ovanesyan S.V. A case of late hemorrhagic disease in a 6-week-old child, complicated by the development of acute cerebrovascular accident and hemothorax. Siberian Medical Journal. 2012. No. 2. P. 114-118.

24. Lyapin A.P., Kasatkina T.P., Rubin A.N. Intracranial hemorrhages as a manifestation of late hemorrhagic disease of newborns // Pediatrics, 2013. No. 2. P. 38-42.

25. Cornelissen M., Von Kries R., Schubiger G., Loughnan PM. Prevention of vitamin K deficiency bleeding: efficacy of different multiple oral dose schedules of vitamin K // Eur. J. Pediatr. 1997 Vol. 156, No. 2. P. 126-130.

26. Von Kries R. Oral versus intramuscular phytomenadione: Safety and efficacy compared // Drug Safety. 1999 Vol. 21, No. 1. P. 1-6.

27. Wariyar U., Hilton S., Pagan J., Tin W., Hey E. Six years’ experience of prophylactic oral vitamin K // Arch. Dis. Child Fetal Neonatal. 2000 Vol. 82, N 1. F64-F68.

28. Puckett R.M., Offringa M. Prophylactic vitamin K for vitamin K deficiency bleeding in neonates // Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2000 Is. 4, No. CD002776.

29. Chuprova A.V. The system of neonatal homeostasis in normal and pathological conditions (scientific review) // Bull. SO RAMN. 2005. No. 4 (118). pp. 13-19.

30. Shabalov N.P., Ivanov D.O. Shabalova N.N. Hemostasis in the dynamics of the first week of life as a reflection of the mechanisms of adaptation to extrauterine life of the newborn // Pediatrics. 2000. N 3. S. 84-91.

31. Andrew M., Paes B., Milner R., et al. Development of the human coagulation system in the full-term infant // Blood. 1987 Vol. 70. P. 165-172.

32. Andrew M., Paes B., Milner R. et al. Development of the human coagulation system in the healthy premature infant // Blood. 1988 Vol. 72. P. 1651-1657.

33. Mitsiakos G., Papaioannou G. et al. Haemostatic profile of fullterm, healthy, small for gestational age neonates // Thrombosis Research. 2009 Vol. 124. P. 288-291.

34. Motta M., Russo F.G. Developmental haemostasis in moderate and late preterm infants // Ital. J. Pediatr. 2014. 40 (Suppl 2): A38.

35. Dorofeeva E.I., Demikhov V.G. and other Features of hemostasis in newborns // Thrombosis, hemostasis and rheology. 2013. No. 1 (53). C. 44-47.

36. Monagle P., Massicotte P. Developmental haemostasis: Secondary haemostasis // Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2011 Vol. 16. P. 294-300.

37. Degtyarev D.N., Karpova A.L., Mebelova I.I., Narogan M.V. et al. Draft clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hemorrhagic disease of the newborn // Neonatology, 2015. No. 2. P. 75-86.

38. Krastaleva I.M., Shishko G.A. and other Problems of treatment of hemorrhagic disease in newborns // Medical News. 2014. No. 9(240). pp. 60-62.

39. Alarcon P., Werner E., Christensen R.D. Neonatal hematology pathogenesis, diagnosis, and Management of Hematologic Problems 2nd Edition // Cambridge University Press. 2013.

40. Report of Committe on Nutrition: vitamin K compounds and the water-soluble analogues // pediatrics. 1961 Vol. 28. P. 501-507.

41. Shahal Y., Zmora E., Katz M., Mazor D., Meyerstein N. Effect of vitamin K on neonatal erythrocytes // Biol. neonate. 1992 Vol. 62. No. 6. P. 373-8.

42. Ipema H.J. Use of oral vitamin K for prevention of late vitamin K deficiency bleeding in neonates when injectable vitamin K is not available // Ann. Pharmacother. 2012. Vol. 46. P. 879-883.

43. Takahashi D., Shirahata A., Itoh S., Takahashi Y. et al. Vitamin K prophylaxis and late vitamin K deficiency bleeding in infants: Fifth nationwide survey in Japan // Pediatric. international. 2011 Vol. 53. P. 897-901.

44. Chawla D., Deorari A.K., Saxena R., Paul V.K. et al. Vitamin K1 versus vitamin K3 for prevention of subclinical vitamin deficiency: a randomized controlled trial // Indian. Pediatr. 2007 Vol. 44, No. 11. P. 817-822.

45. Dyggve H.V., Dam H., Sondergaard E. Comparison of the action of vitamin K1 with that of synkavit in the newborn // Acta Pediatrica. 1954 Vol. 43. No. 1. P. 27-31.

Vitamin K2, essential for newborns and valuable for children and the elderly

Vitamin K2 plays an important role in the health of newborns and is valuable for both children and the elderly, where, among other things, it has a cardioprotective effect. In addition to the known benefits of regulating blood clotting and bone health, as well as various other benefits.

In a recent scientific review published on Children (Kozioł-Kozakowska A, Maresz, 2022) summarizes the extensive scientific literature on a vitamin that the human body cannot synthesize and therefore must be consumed in the diet. (1)

Vitamin K2 sources

Vitamin K (Naphthoquinone) is fat soluble and is divided into two types according to origin.

- K1 (phylloquinone), plant origin and mainly found in green leafy vegetables such as spinach, broccoli, lettuce, Brussels sprouts.

- K2 (menaquinone) MK-7, of bacterial origin and present in large quantities in "natto", a Japanese dish based on fermented soybeans (cover). Its MK-4 form is also found in rarely eaten animal organs (liver, brain, kidneys, pancreas).

Other Sources Meat (especially chicken, bacon, and ham), egg yolks, and full-fat dairy products such as hard cheeses are important sources of vitamin K2.

Vitamin K in algae and microalgae

Algae and microalgae in turn, they are valuable sources of vitamin K:

- nori seaweed ( porphyry sp. or washbasin contains approx. 60 g/m2) dried vitamin K,

- wakame seaweed ( Undaria pinnate ) and hijiki ( Sargassum fusiform ), dried, containing respectively 1293 mcg/100 g and 175 mcg/100 g of vitamin K1,

- microalgae and cyanobacteria are also valuable sources of vitamin K (2,3).

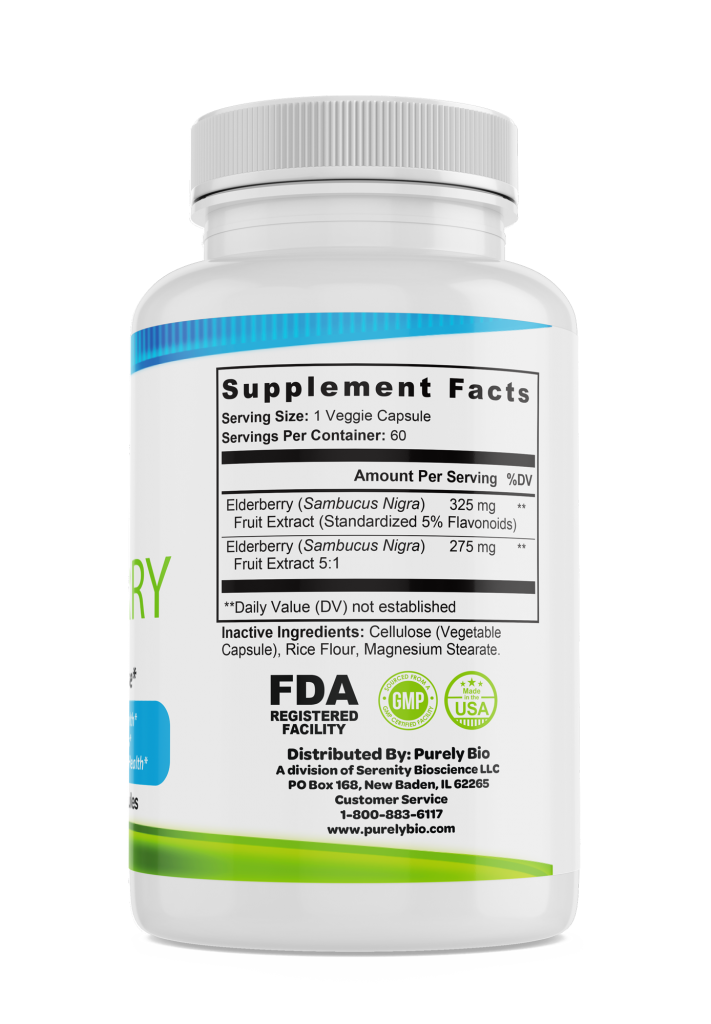

Fig. 1 - Vitamin K in algae and microalgae (Simes et al., 2020. See notes 2,3).

Vitamin K2 and activation of essential proteins

Scientific research now it is clear that vitamin K2 activates proteins that perform important biological functions:

- mineralization of bones and teeth, including for anti-caries function,

- cardiovascular health,

- brain development,

- joint health,

- body weight control.

Studies scientific evidence from the review under consideration suggest the use of vitamin K2 already in some pathological conditions of childhood and adolescence, such as: - inflammatory bowel disease and liver disease,

- severe disability often associated with malnutrition, malabsorption, microbiota changes and liver dysfunction.

Koziol-Kozakovska A., Maresh K. Effects of vitamin K2 (menachionones) on children's health and disease: a review of the literature.Vitamin K2, Essential Dietary Supplement

In addition to the cases mentioned In terms of disease, the significant decline in intakes of vitamin K, and vitamin K2 in particular, is due to the impoverishment of Western dietary patterns over the past 50 years. With severe health consequences.

To aggravate the situation Therapy used in pediatric practice based on antibiotics and glucocorticoids for a long time contributes to: skeleton causing osteoporosis.

Risk of deficiency in newborns

Vitamin K deficiency this is common in newborns. This is due to poor synthesis of the vitamin due to the fact that the intestines are still poorly colonized by bacteria, reduced passage of vitamin K through the placental barrier and low accumulation in breast milk (with the exception of newborns in eastern countries). Japan).

Such a deficiency of in newborns can cause bleeding, even fatal. A safe form of prophylaxis is a single intramuscular injection of vitamin K at birth, according to the recommendations of the renowned pediatric hospital Bambino Gesu in Rome, which explains: This administration is recommended for all newborns (not just those at increased risk of bleeding). '. (4)

Vitamin K, role in adulthood and the elderly

The proteins that are dependent on vitamin K ( vitamin K-dependent proteins , VKDP)—widely distributed in tissues, even outside the liver—are best known for their protective role in bones and the cardiovascular system. In addition to being involved in cell differentiation and proliferation, inflammation and signal transduction.

Deficiency Thus, vitamin K has been associated with various chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), chronic kidney disease, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, cancer, dementia, certain skin diseases, functional impairment and disability. Pathologies are largely associated with pathological calcification and inflammation, where the role of VKDP and vitamin K is highlighted.

study Rotterdam Avenue - conducted in 4,807 people without a history of myocardial infarction and followed for 7 years - low levels of vitamin K2 (and not also K1) were associated with a significant risk of coronary heart disease ( Coronary heart disease CHD ), all-cause mortality, and severe aortic calcification. (5)

Room Prospect-EPIC cohort of 16,057 women without CVD, since follow-up median 8.1 years - an inverse relationship was found between vitamin K2 (particularly MK-7, MK-8 and MK-9) and the risk of coronary artery disease with an 85-100% reduction in coronary events for every 10 mcg increase in vitamin K2 intake. (6)

K2, safe and effective

In the form of MK-7 , vitamin K2 has a documented history of safe and effective use in children and adults. The only possible contraindication is the use of anticoagulant drugs such as coumarins, which can interfere with vitamin K production.

Expert Panel The Scientific Committee on Diet, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA) of EFSA, in its opinion dated 22.5.17, confirmed the dietary reference values established by the Scientific Committee on Foods in 1993.

Daily amounts of adequate vitamin K intake are indicated at:

- 10 mcg for children aged 7 to 11 months;

- 12 micrograms for children aged 1 to 3 years;

- 20 micrograms for children aged 4 to 6 years;

- 30 micrograms for children aged 7 to 10 years;

- 45 micrograms for children 11 to 14 years of age;

- 65 micrograms for adolescents 15-17 years of age e

- 70 micrograms for adults, including pregnant and lactating women. (7)

Martha Strinati and Dario Dongo

Nippon.com cover image, https://www.nippon. com/hk/japan-glances/jg00116/

Attention

(1) Kozel-Kozakovska A., Maresh K. Effects of vitamin K2 (menachionones) on children's health and disease: a review of the literature. Children. 2022; 9 (1): 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/children

78

(2) Dina S. Simes, Carla S.B. Viegas, Nuna Araujo, Katarina Marreiros (2020). Vitamin K as a dietary supplement affecting human health: current evidence on age-related diseases . Nutrients. Jan 2020; 12 (1): 138. doi: 10.3390 / nu12010138

(3) Vitamin K1 synthesis has been found in several species of macroalgae and microalgae, such as porphyra sp , ( Rhodophyta

(4) Bambino Gesu Children's Hospital. Vitamin K . https://www.ospedalebambinogesu.it/vitamina-k-89768/

(5) Geleiinse JM, Vermeer C., Grobbeehlight DE, Schurgers LJ, Knapen MHJ, Van Der Meer IM, Hofman A., Witteman JCM (2004 ). Dietary intake of menaquinone is associated with a reduced risk of coronary heart disease: a study in Rotterdam . J. Nutr. 2004, 134: 3100-3105. doi: 10.1093 / v / 134.11.3100

(6) Gast GC, de Roos NM, Sluijs I., Botsnary ML, Beulens JW, Geleinse JM, Witteman JC, Grobbee DE, Peeters PH, van der Schouw YT (2009). High consumption of menaquinone reduces the incidence of coronary heart disease. Int. Metab. Cardiovas. Dis. 2009, 19:504-510. doi: 10.1016 / j.numecd.2008.10.004

(7) Recommended dietary values: EFSA publishes opinion on vitamin K. 22.5.17 https://www.efsa.europa.eu/it/press/news/ 170522-1

Martha Strinati

+ messages

Professional journalist since January 1995, working for newspapers (Il Messaggero, Paese Sera, La Stampa) and periodicals (NumeroUno, Il Salvagente). An author of journalistic food reviews, she published the book Reading Labels to Know What We're Eating.

Dario Dongo

+ messages

Dario Dongo, lawyer and journalist, PhD in international food law, founder of WIISE (FARE - GIFT - Food Times) and Égalité.