How to teach a child with odd

6 Ways to Help Students with ODD

Most children will, at times, argue and test limits. Yet some kids are defiant and hostile to a degree that interferes with their daily lives—behavior that’s sometimes diagnosed as Oppositional Defiant Disorder, or ODD, according to a story by WeAreTeachers.

“Students with ODD disrupt their own lives and often the lives of everyone nearby,” write the report’s authors. “[They] push the limits of defiance far beyond reason. Their problem behavior is much more extreme than that of their peers, and it happens much more often.”

According to the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, kids with ODD exhibit “an ongoing pattern of uncooperative, defiant, and hostile behavior toward authority figures that seriously interferes with the child’s day-to-day functioning,” for six months or more. Symptoms like frequent temper tantrums, excessive arguing with adults, and mean and hateful speech when upset, are usually seen across multiple settings, but especially at home or school. While a direct cause remains unclear, “biological, psychological, and social factors may have a role,” the academy notes. Up to 16 percent of children may have the disorder, and children with ADHD are especially prone.

Though a teacher’s first reaction to ODD might be to react defensively, this can backfire and create a power struggle with the student, say experts. Instead, teachers who’ve worked with students with ODD recommend a set of strategies that will address challenging behavior, and help you start building relationships with hard-to-reach students.

“We all have the capacity to learn, change, and grow,” writes special education teacher Nina Parrish. “When given the right tools and environment, students with problematic behavior can learn more productive strategies that will help them have positive and effective interactions with others.”

1. Be Calm and Consistent: As a new teacher, Parrish says she quickly learned that reacting with anger when her students with ODD acted out made the behavior worse and students became “amused or encouraged by upsetting an adult. ” Instead, Parrish recommends trying to keep a positive tone to your voice, adopting neutral body language, and being “cautious about approaching the student or entering their personal space as this might escalate the situation.”

” Instead, Parrish recommends trying to keep a positive tone to your voice, adopting neutral body language, and being “cautious about approaching the student or entering their personal space as this might escalate the situation.”

Consistency with words and actions is also important when working with kids with ODD. Teacher Brandy T. tells WeAreTeachers she routinely uses the same set of “trigger words” so her students know she’s serious. When students in her class begin to argue with her, “I simply say either, ‘not now,’ ‘later,’ or ‘fix the issue.’” When her students hear ‘fix the issue,’ for example, she says that’s the signal to “go to their chill-out space if they need to calm down.”

2. Reinforce Positive Behavior: For all kids, but especially children with ODD, it’s important to “switch your focus from recognizing negative behavior to seeking out demonstrations of positive behavior,” writes Parrish. She sends home positive notes when students show behavior improvements, even if they’re small gains.

Additionally, consider offering students the opportunity to earn certain privileges, suggests WeAreTeachers, rather than “taking those privileges away as punishment.” For example, give kids the opportunity to earn rewards—like a bit of iPad time or lunch with a teacher.

3. Find Out What’s Going On: Behaviors, notes Parrish, help students “obtain something desirable, or escape something undesirable.” She suggests thinking about behavior as feedback, or a way of communicating, an approach that’s “helped me work more effectively as a teacher with students who display problem behaviors.” Figuring out factors that contribute to students with ODD acting out can help you develop a plan for addressing their difficult behaviors in the classroom.

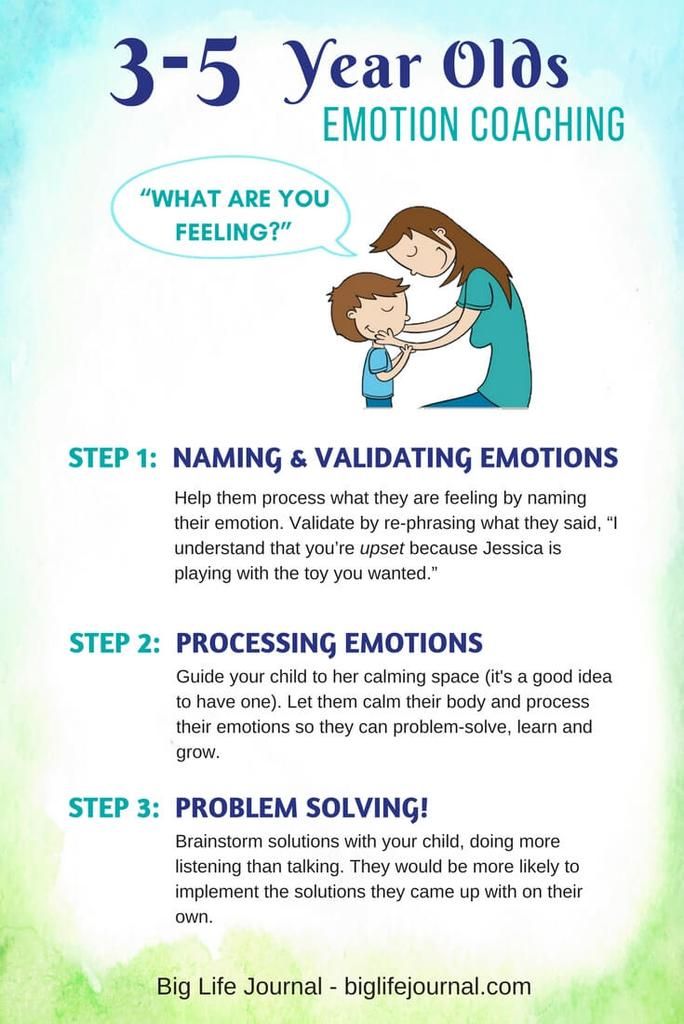

Sometimes, it’s a matter of picking up on a student’s signals that their emotions are building long before things reach a breaking point. When students who’ve experienced trauma are beginning to feel upset, they often show physical signs of their mounting distress: balling up fists, withdrawing from classroom interaction, or clenching their jaw, writes Micere Keels, an associate professor at the University of Chicago and a trauma-informed educator.

“Many educators tend to ignore students’ increasing signs of agitation, hoping they’ll eventually calm down. But when disregarded, these minor behaviors can quickly escalate,” writes Keels, who also recommends identifying students’ triggers, like touch or emotionally difficult anniversaries, to avoid situations entirely.

4. Create a Safe Reset Space: Kids with ODD “can learn to recognize when they’re feeling overwhelmed and getting ready to challenge or defy,” according to WeAreTeachers. “Giving them a safe space to calm down and rethink their choices can be beneficial.”

At Fall-Hamilton Elementary, a trauma-informed school in Nashville, Tennessee, for example, every classroom has a nook—called a peace corner—with a comfortable seat, a timer, and items like stuffed animals, sensory squeeze toys, and simple drawing and writing supplies. It’s a spot where kids can take a break and reset. The school also recognizes that teachers may need a time out too. Using a strategy called Tap-in/Tap-Out, teachers can ask a colleague via text message to briefly cover their class if they are about to lose their cool.

Using a strategy called Tap-in/Tap-Out, teachers can ask a colleague via text message to briefly cover their class if they are about to lose their cool.

"A dysregulated adult cannot regulate a dysregulated child,” says school principal Mathew Portell. “Use strategies that honor the student’s emotions and need for space while also getting their systems to calm in a safe way.”

5. Offer Choices: It’s important to “affirm your students’ autonomy by giving them choices,” writes Keels, about best practices for de-escalation. When kids feel respected, “their sense of belonging and mood will often improve.”

She recommends avoiding ultimatums like “You better sit back down or I’ll send you to the office.” Instead, clearly communicate expectations and limits so kids understand. You might say, “I see you’re upset, but it’s not OK to yell at me. You can either go get a drink of water and come back in five minutes, or sit in the reading chair and I will check in with you in five minutes,” says Keels.

In the heat of the moment, it’s important to avoid an argument, teacher Holli A. tells WeAreTeachers. “State your choices, then walk away,” she says. “Give the student time to process and decide which choice to make. If they don’t like the choices, don’t engage. When they try to argue, repeat the choices, and walk away again. If the student still will not choose, they do not get to participate in their preferred activity.”

6. Build Connections: Often, kids with ODD “are looking for a relationship with a teacher who can help them deal with problems on their own, instead of making them stand out in a negative way,” according to WeAreTeachers. “Building a connection with them will help get to the root of the behavior.”

Though teachers can feel the need to create boundaries with students, simply talking with them informally can build invaluable connections that influence their behavior in the classroom, says middle school math teacher Cicely Woodard.

Woodard says she intentionally makes herself approachable to students and tries to learn interesting details about them. “Some of my students tell me stories about their lives during the five minutes between classes,” Woodard says. “I stop what I am doing, look them in the eyes, and listen.”

Primary School Teacher Strategies for Oppositional defiant disorder

On this page:

- About

- Strengths

- Evidence-based strategies

- Best practice tips

- Curriculum considerations

- Other considerations

- Relevant resources

About oppositional defiant disorder

All children have times when they might refuse to do something they are asked, disrupt others or not listen. Children with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) need support with these behaviours which disrupt their day-to-day life. These students can appear defiant, disobedient, angry and irritable. They might argue with parents, teachers and other students. They may find it hard to follow teachers’ instructions. They may lose their temper if they feel like something isn’t going their way. Sometimes, it might seem like they annoy other students on purpose, or don’t take responsibility for their actions. They might refuse to join in group activities and get out of their seat regularly.

They might argue with parents, teachers and other students. They may find it hard to follow teachers’ instructions. They may lose their temper if they feel like something isn’t going their way. Sometimes, it might seem like they annoy other students on purpose, or don’t take responsibility for their actions. They might refuse to join in group activities and get out of their seat regularly.

For some students with ODD, reading, writing, maths and concentrating can be hard. Some may also have language delays and find talking about emotions difficult. Students with ODD can have trouble communicating, and making friends. It is also common for students with ODD to have low self-esteem.

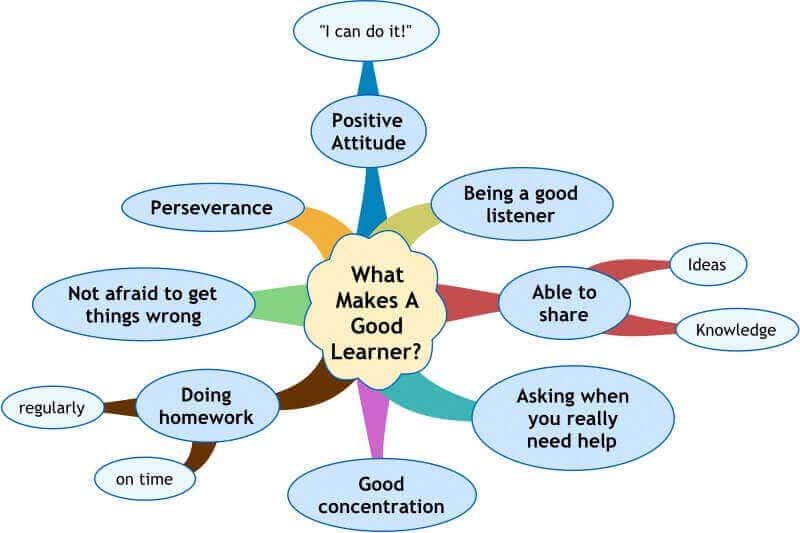

Strengths

What might be some strengths?

- Some students will be able to learn and pay attention in the same ways as other children.

- Students with ODD often have a normal working memory. This means they can remember things in their head like images, numbers or several pieces of information at once.

- Many students with ODD are highly motivated by reward systems.

- Students with ODD often enjoy hands-on learning. They may learn new information well through this approach.

- Some students with ODD are creative and enjoy art.

Where might you provide support?

- Students with ODD may need support managing their emotions. They may have temper tantrums, or they may be easily frustrated.

- They may find it hard to follow instructions and rules, which can be disruptive for class time, excursions, and activities like physical education.

- Students with ODD may have trouble making and keeping friends. They sometimes have trouble communicating and may find it hard to understand social situations. This can also impact their self-esteem.

- They may find problem solving hard. This can make schoolwork difficult, particularly as they may get frustrated easily. Finding it difficult to understand a problem or conversation is often a reason for emotional outbursts.

- Students with ODD might not be able understand the consequences of a behaviour. They might distract another student in class without thinking about the other student, the class or what the teacher might say.

Evidence-based strategies

Provide a positive environment

Be proactive

Build a child’s skillset

Collaborate with parents

Punishment may not lead to changes in challenging behaviour. Instead, rewards/encouragement can be given for positive behaviours. Behaviour charts with stickers help students see their progress. Students may be more motivated if they can choose their favourite reward like a sticker, game or book.

Punishment may not lead to changes in challenging behaviour. Instead, rewards/encouragement can be given for positive behaviours. Behaviour charts with stickers help students see their progress. Students may be more motivated if they can choose their favourite reward like a sticker, game or book. You can find other general social skills strategies on the social functioning page.

You can find other general social skills strategies on the social functioning page.

Learning simple ways to relax may help students with ODD manage their emotions. Watch an example of a breathing and relaxation exercise on the teacher resources page.

Learning simple ways to relax may help students with ODD manage their emotions. Watch an example of a breathing and relaxation exercise on the teacher resources page.

Best practice tips

Consider your tone

Have a clear and predictable schedule

Curriculum considerations

The Arts

English

Health and Physical Education

The Humanities

Languages

Mathematics

Science

Technologies

g. “How did that sound make you feel?”)

g. “How did that sound make you feel?”)

Consider tailoring your approach to a child’s strengths.

Consider tailoring your approach to a child’s strengths. Other considerations

Safety

First aid

Safety drills

Behaviour

Relief teachers

Friendships

Homework

Excursions/camps

Language delays

Wellbeing

Transitions

Other co-occurring conditions

Relevant resources

Visit our resources page for a range of resources that can help to create inclusive education environments for children with disabilities and developmental challenges. Some particularly relevant resources for children with oppositional defiant disorder include:

Strengths and abilities communication checklist

Class schedule

Emotion cards (A4)

Student self-monitoring form

Problem solving guide

Story - When my teacher is away

Story - Going on an excursion

Download this page as a PDF

Odd and even numbers for preschoolers

Numbers, numbers…. The kid begins to get acquainted with them already at preschool age, and at first they seem to him incomprehensible signs in the form of hooks and squiggles. Gradually, the child masters not only numbers and counting within twenty, but also the simplest skills of addition and subtraction. It's time to introduce him to such a concept as even and odd numbers.

Gradually, the child masters not only numbers and counting within twenty, but also the simplest skills of addition and subtraction. It's time to introduce him to such a concept as even and odd numbers.

But how to make sure that the learning process does not turn into a boring activity? And how do you understand and remember all these definitions and properties? The answer is simple: learning is better through play and entertaining exercises.

What are even and odd numbers?

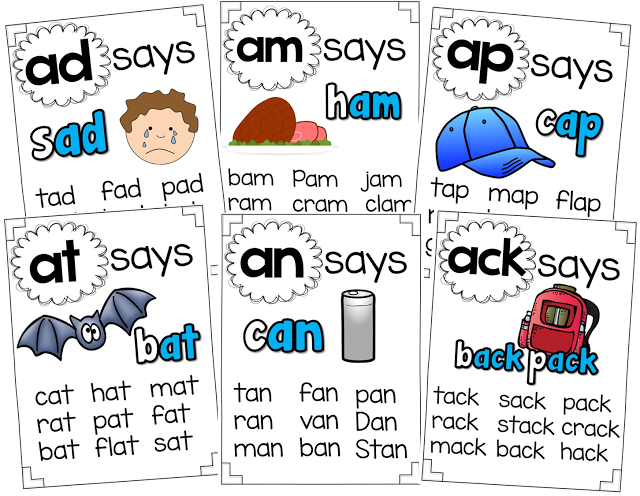

Before starting to get acquainted with even and odd numbers, you should make sure that the baby knows the sequence of numbers well. Use the game format "My and your numbers" to check. The game has very simple rules: you call the number 1, the child calls the next one. Then again your turn (number 3), and then the child's turn (number 4) and so on up to ten or twenty. At the next stage, you can change the sequence: the child begins the number series, and you continue it. This is a good exercise for memory and mindfulness.

Now you can explain to the child what even and odd numbers are. So, even numbers are those that are divisible by two without a remainder. Odd cannot be divided in half. It will be easier for a kid to understand this principle using a good example:

Let's take three oranges and try to divide them equally between you and a friend. How to do this and how many oranges will each of you get?

Surely the child will come to the conclusion that it will not work to divide the fruit exactly in half. Some will get more, and some will get less. Or one orange will have to be cut, that is, everyone will get one whole fruit and another half.

What if you were given four oranges? Can you share them equally with a friend?

In this case, the child will divide the vitamin supply so that no one is offended: each will get two oranges.

It should also be explained to the child that even and odd numbers in a sequential row alternate with each other: 9.

And a few more rules to remember:

All numbers ending in 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 are even.

Numbers ending in 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 are odd.

These rules apply to both single and double digit numbers. Understanding the essence will help the child to cope with complex mathematical problems in the future.

Even and odd numbers on practical examples

The main goal of any educational process is to activate mental activity. No need to concentrate only on giving the child ready-made knowledge. Any information is much better remembered if you master it with practical examples.

First ask the baby to count the number of sweets in the vase or flowers in the bouquet and determine if this number is even or odd?

Similar techniques can be used not only during classes, but also in everyday life: on a walk, during a trip to the country, when visiting a cafe. Let the baby count all the objects that come across - cars, cakes, road signs, cutlery, toys. If he does the tasks correctly, you can proceed to more complex concepts: the properties of even and odd numbers.

If he does the tasks correctly, you can proceed to more complex concepts: the properties of even and odd numbers.

Properties of even and odd numbers

Properties of even and odd numbers are useful when performing all mathematical operations: addition, subtraction, multiplication, division. There are several basic properties, and we'll start with the simplest:

Adding two even numbers always results in an even number.

2 + 4 = 6;

8 + 2 = 10.

Adding an even number and an odd number results in an odd number.

7 + 2 = 9;

4 + 5 = 9.

Adding two odd numbers adds up to an even number.

3 + 7 = 10;

5 + 1 = 6.

The same principle is used when subtracting:

6 - 2 = 4;

9 - 7 = 2; 10 - 3 = 7 And don't forget to remind the young mathematician of the same properties of addition and subtraction.

Two-digit addition:

12 + 24 = 36;

28 + 17 = 45;

11 + 19 = 30;

Two-digit subtraction:

24 - 12 = 12;

39 - 15 = 24;

48 - 25 = 23.

Multiplication and division are a bit more complicated. Here you will need not only the ability to remember properties, but also an understanding of the meaning of mathematical operations.

Multiplication properties:

Multiplying even by even always results in even.

2 x 8 = 16

3 x 4 = 12.

Multiplying odd by odd is odd.

5 x 3 = 15.

Properties when dividing:

When dividing two even numbers, the result can be either even or odd:

12 : 4 = 3;

16 : 4 = 4.

Even divided by odd is even.

12 : 3 = 4.

Dividing odd by odd, we get odd. 21 : 3 = 7

About zero

As noted above, zero is an even number. Unfortunately, many adults will be puzzled by the question of zero belonging to a particular group. What can we say about children, for whom this strange circle, similar to the letter "o", remains a mystery until a certain moment.

To make it easier to determine even and odd, you need to remember the definition: even numbers are divisible by two without a remainder, odd numbers are not divisible. But here, with respect to zero, another difficulty arises: not every child can even understand what it means to divide zero by any number. And just in this case it is better to just remember a few rules:

Zero is an even number, it is the first in the number series.

Dividing zero by any number, odd or even, always results in zero. That is all the same even number.

Practice reading odd and even numbers whenever possible. If the child has just mastered the simplest actions within twenty, then use puzzles with prime numbers. And only then, as you study the material, you can use more complex examples.

If the child has just mastered the simplest actions within twenty, then use puzzles with prime numbers. And only then, as you study the material, you can use more complex examples.

Chapter "Mathematics and Logic" from the book "Believe in Your Child"

All calculations are based on counting, so the child should develop the ability to count in the first place. But “counting” means, on the one hand, knowing the names of numbers, and on the other hand, understanding the essence of the counting process itself. As always, if knowledge precedes understanding, the child will advance faster. From the age of one and a half, the baby begins to benefit from the very first exercises, provided that you are not in a hurry.

Numbers from 1 to 10.

Count out loud (loud and clear) before you do anything: turn off the lights, turn on the TV, open the door. Try to do this at least once a day. Soon the child will be able to name numbers from 1 to 10. But this does not mean at all that he has learned to count. It's just that when he understands what an account is, he will be able to concentrate all his attention on the essence of the actions performed, without straining his memory too much, since he has already memorized the numbers.

But this does not mean at all that he has learned to count. It's just that when he understands what an account is, he will be able to concentrate all his attention on the essence of the actions performed, without straining his memory too much, since he has already memorized the numbers.

Counting should become as common as speaking.

Eating rituals offer the greatest opportunity for this. Count plates, knives, pieces of meat, spoons of porridge ... Seeing how you think, the baby will want to follow your example. As soon as he shows such a desire, encourage him to try to count with you. And so that he better understands that the score is not just a funny abracadabra, put a plate in front of him and put three identical objects next to it. Tell your child to put the items on the plate one at a time and count them at the same time. Help him if needed. “You see, there are three cubes, there are three cubes in the plate! Now let's see how many there will be this time . .. "Give him two dice and start the game again. When he has learned the numbers one, two, and three well, add the fourth die, and so on.

.. "Give him two dice and start the game again. When he has learned the numbers one, two, and three well, add the fourth die, and so on.

Numbers greater than 10.

When a child (usually at the age of three) learns to count objects, he will make more and more progress. And therefore it is necessary that you always get ahead of him. Once he can count to 10, introduce him to the next ten in the manner described above. You can also sing the numbers to a motive familiar to the baby (for example, the songs “How can I explain to my mother ...”). When he can count a certain number of objects, buy, for example, beans, and have him count the beans, shifting them from one vessel to another. Give him a mug to which you add a few beans (or balls) every day. When they reach 50, take another mug and say, “There are 50 beans in your mug. And the next beans you will put in another mug! This will allow you to somehow "make sure" that there are still 50 beans in the first mug. Next time, you can focus on the numbers that follow, without having to start the whole count from scratch.

Next time, you can focus on the numbers that follow, without having to start the whole count from scratch.

Zero.

Explain to your child what zero is. This is very important, because when you go to zero, you will need to write numbers after 9. To make your baby feel that a number that stands for nothing is a very special number, ask him joke questions: “How many cows do you have in your pocket? How many crocodiles do we have in the bathroom? You can be sure that he will never forget what zero is!

Count by touching.

When the child properly learns to count objects, shifting them from one vessel to another, show him your hand with spread fingers and ask him to count the fingers, touching them. You can help the baby by moving the finger he needs to touch.

Then invite him to count the objects in front of him, touching each of them. It is necessary that he understands that he must touch each object once. This is not easy, which is why it is desirable to start the exercises in terms of transferring objects from one vessel to another. Finally, teach him to count the objects shown in the pictures in the book.

Finally, teach him to count the objects shown in the pictures in the book.

Countdown.

This is a very important exercise, as the child will not learn to subtract if he cannot "count backwards". However, wait for him to master counting to 30 (at least) before starting this new game. Otherwise, you will confuse him. The whole learning procedure is similar to that for regular counting. When the baby learns to count backwards (from 10 to 1), start counting from 11, then from 12, and so on. Counting back from 20 to 10 is often the most difficult thing for a child, but when he encounters those numbers that he already learned when counting from 10 to 1, things go much better.

Count up to a predetermined number.

It is necessary to teach the child to count to a predetermined number. Put a handful of beans in front of the baby and ask him to count 3 of them. When he understands this, ask him to make several piles of beans - for example, 3, 5, 9 pieces each. If the child copes with this task, place objects in a row in front of him. Ask him to count (touching them, but not moving) a smaller number of objects than lies in front of him. Finally, do the same exercise by counting the objects depicted in the book. Regularly ask your baby to count up to a certain number you specify, without touching objects or mentioning them.

If the child copes with this task, place objects in a row in front of him. Ask him to count (touching them, but not moving) a smaller number of objects than lies in front of him. Finally, do the same exercise by counting the objects depicted in the book. Regularly ask your baby to count up to a certain number you specify, without touching objects or mentioning them.

N.B. For counting to become a habit, a child must count often. The above numerous options are needed in order, on the one hand, to avoid monotony, and on the other hand, to teach him to count in different ways. As a result, he will begin to count everything that surrounds him. Encourage this desire. Daily counting exercises prepare his mind for calculations.

Alternate account.

When your baby is good at learning the names of numbers, play counting with him: you say 1, he says 2, you say 3, he says 4, etc. At first he will want to call your numbers; explain to him that this is prohibited by the rules of the game. Next time he should start: he says 1, you say 2, and so on. When the child can easily cope with such a task, involve someone else in the game (say, another child, he will like it too!) And play with three, then four, etc. Now that he quickly figured out what's what, continue to play only if he shows interest.

Next time he should start: he says 1, you say 2, and so on. When the child can easily cope with such a task, involve someone else in the game (say, another child, he will like it too!) And play with three, then four, etc. Now that he quickly figured out what's what, continue to play only if he shows interest.

Even and odd numbers.

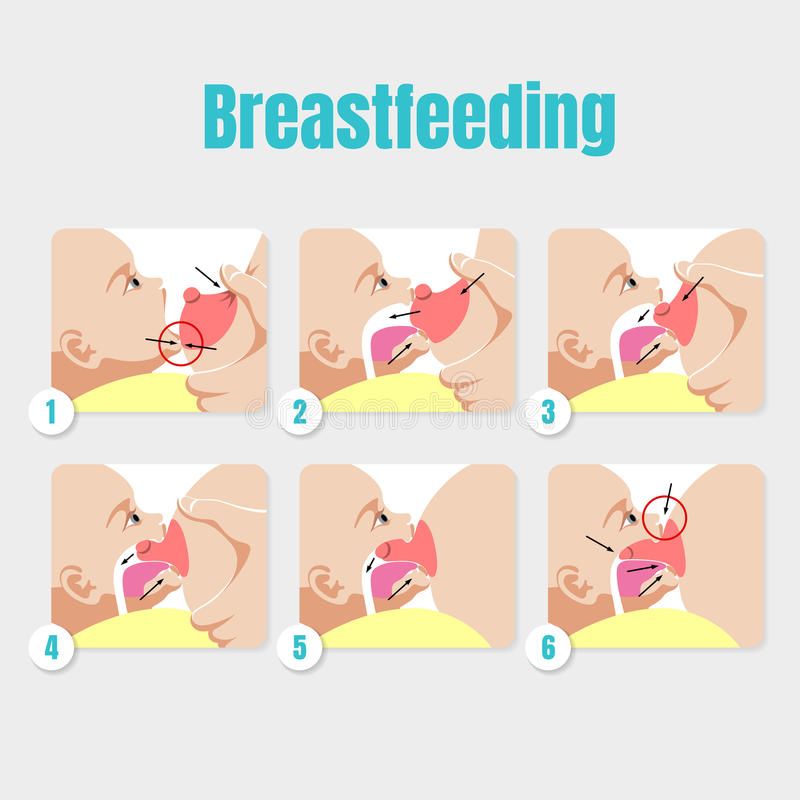

To explain this concept to a child, take two plates and a handful of beans:

This is your plate and this is mine. Here are two beans. Can you put as many beans on my plate as you have on yours? Yes, sure! You can put one bean on your plate and one on mine. Now here are three beans for you, see if you can do the same with them? .. No! There are two beans in one plate, and one in the other. You see, it turns out that the number 2 can be divided into two equal parts (such a number is called even), but the number 3 cannot be divided into two equal parts (it is called odd). Now let's see how 4 ... 9 behaves0018

When your child understands the difference between an even and an odd number, take turns counting with one of you calling the odd numbers and the other calling the even numbers.