Pregnant pertussis vaccine

Pertussis Vaccine: Receiving Tdap During Pregnancy

The Risks and Dangers of Pertussis

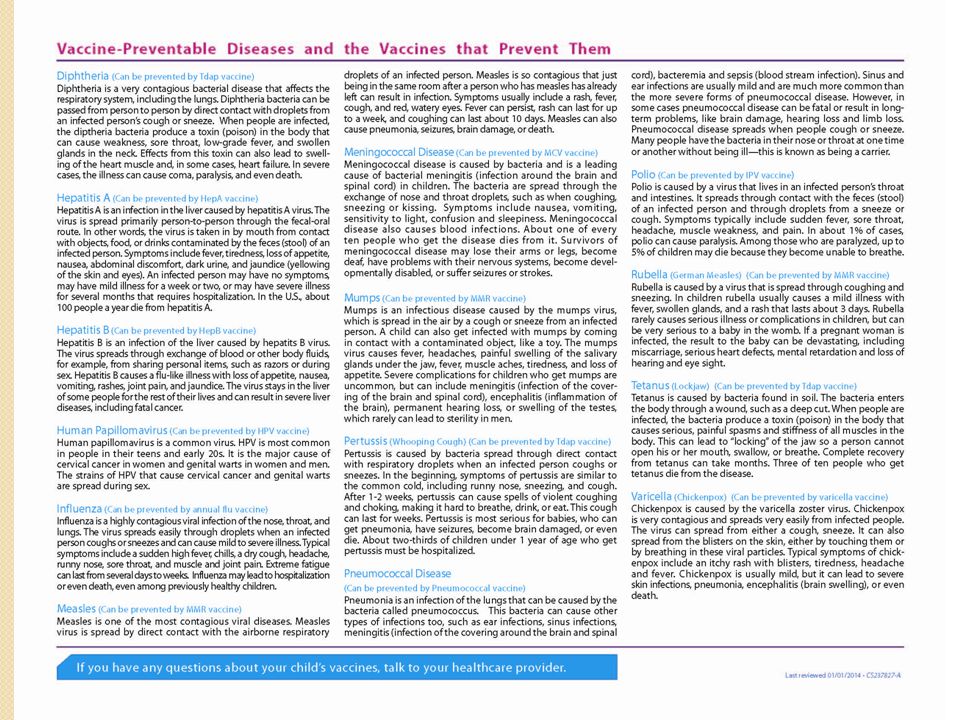

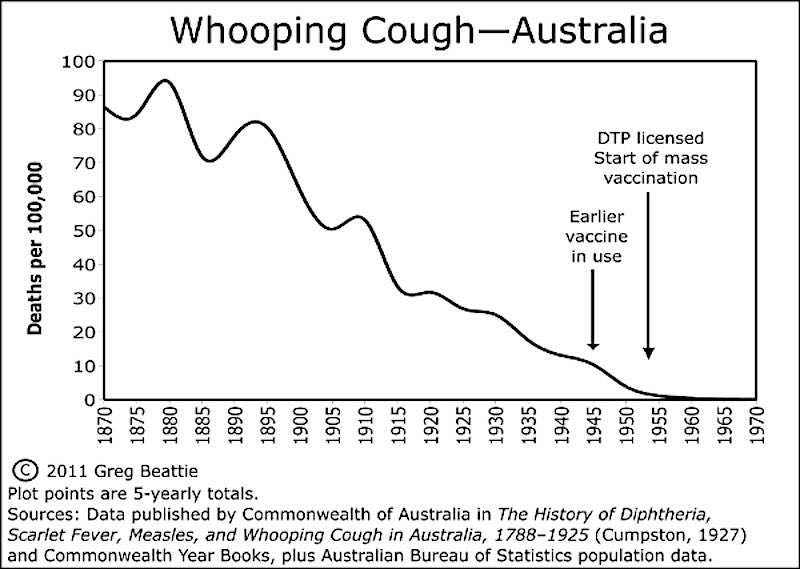

Pertussis is on the rise, and outbreaks are occurring across the United States. Infants are most at risk of contracting pertussis and having severe, potentially life-threatening complications from the infection. In fact, the incidence rate of pertussis among infants is higher than the rate in any other age group, and the majority of pertussis-related deaths occur in infants younger than 3 months of age.

Pertussis by the Numbers

- 28,660 Pertussis cases in the United States (18% increase from 2013)

- 6,951 Pertussis cases in California (other states reporting more than 1,000 pertussis cases were Colorado, Michigan, Ohio, Texas, and Wisconsin)

- 2,974 Pertussis cases in infants younger than 6 months of age (10.

4% of all reported cases)

Tdap Vaccine Recommendation

Public health efforts are focused on protecting infants until they are old enough to receive their own vaccines to build immunity against pertussis.

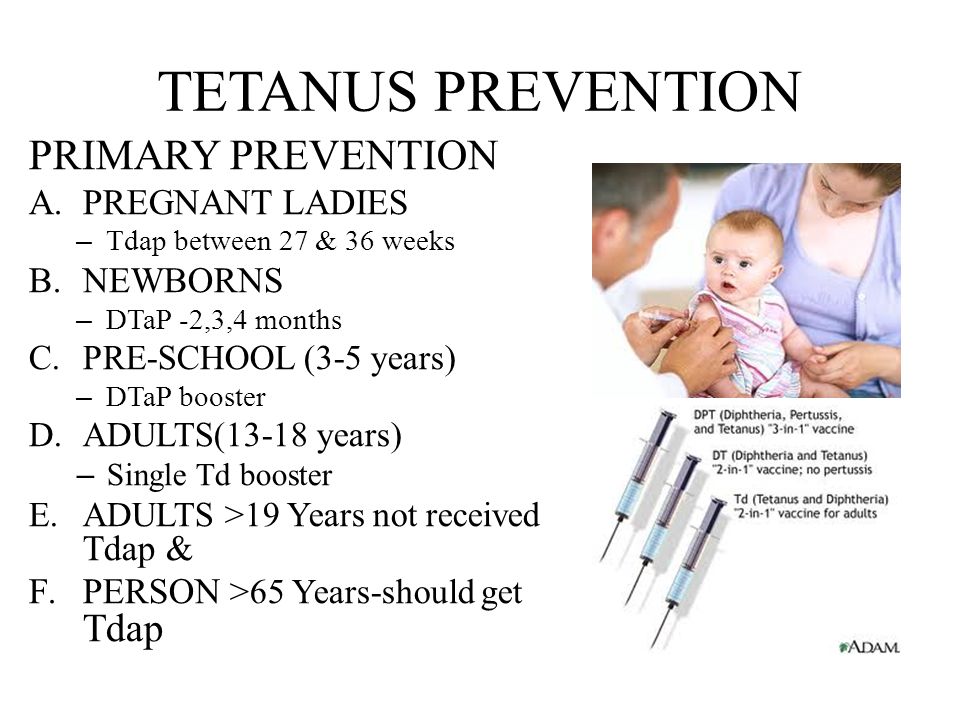

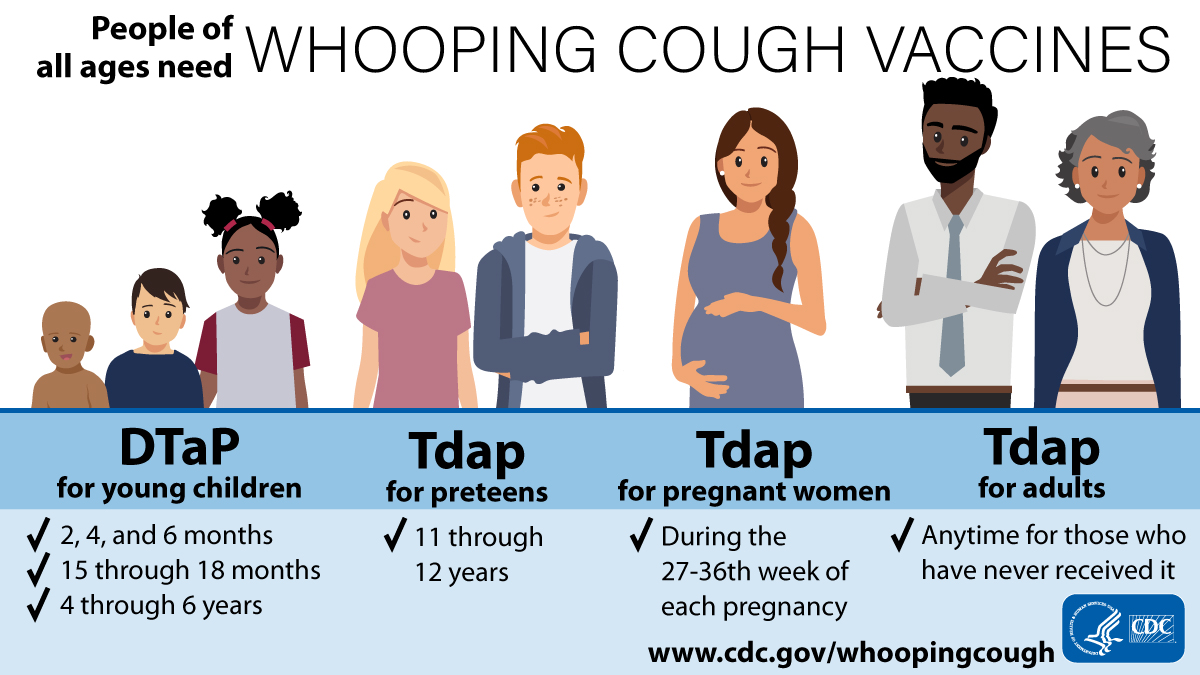

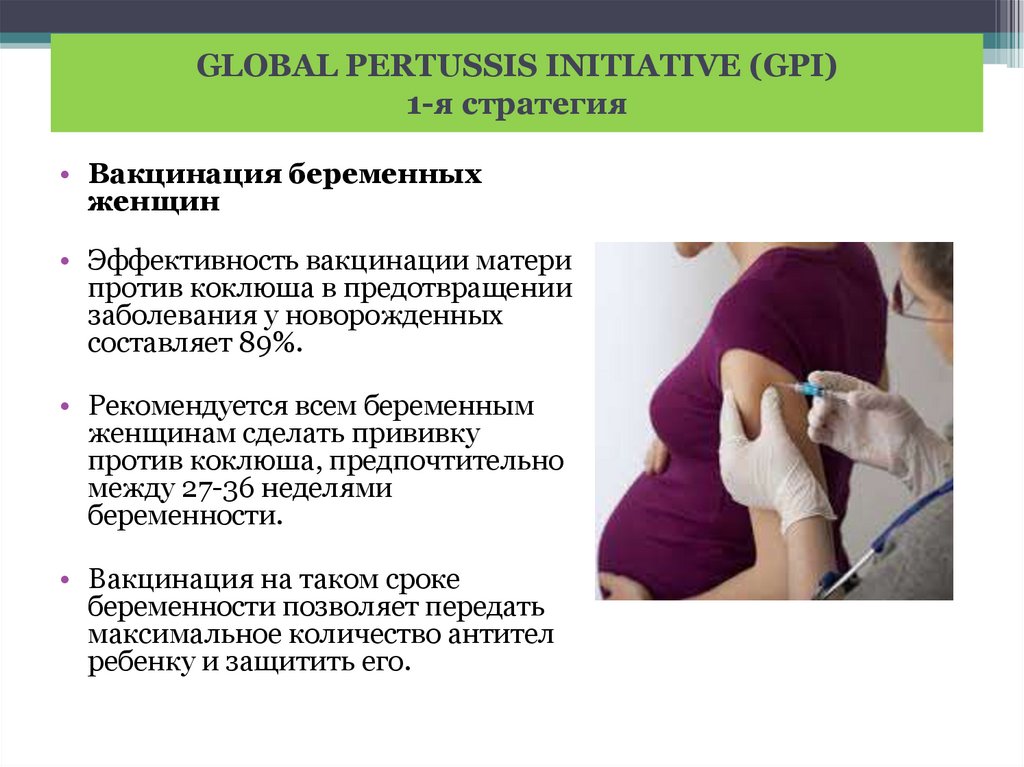

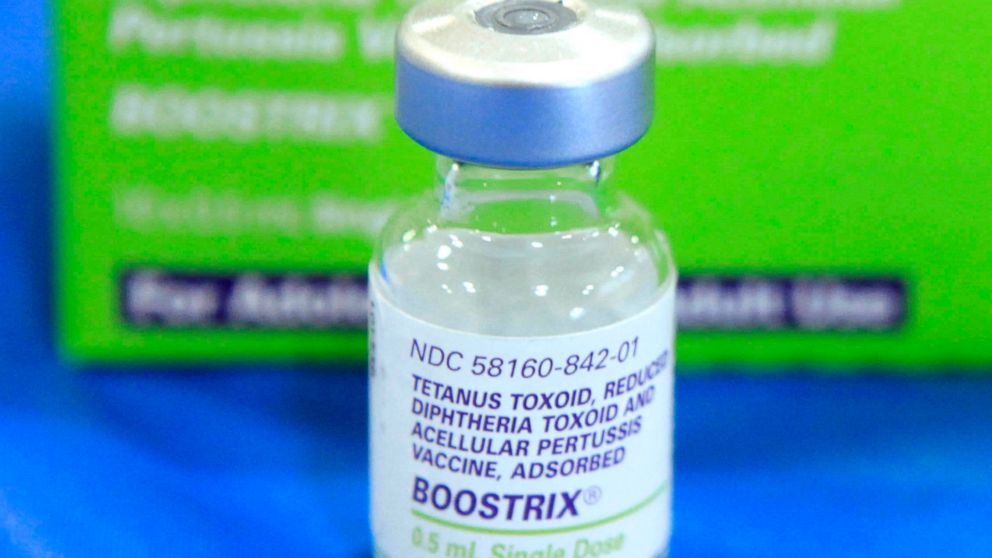

For this reason, pregnant women should receive a dose of the tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine during every pregnancy, ideally between 27 and 36 weeks of gestation. By getting the Tdap vaccine during pregnancy, a mother builds antibodies that are transferred to her baby to provide protection against pertussis until the infant can start getting the diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTaP) vaccine at 2 months of age.

Tdap Vaccine Safety

The Tdap vaccine is safe for both mother and baby at any time during pregnancy, but vaccination is recommended between 27 and 36 weeks of gestation because the maternal immune response to the vaccine peaks approximately two weeks after administration. This recommended timing optimizes passive antibody transfer to the baby and provides the best protection at birth.

Tdap Vaccine Effectiveness

Early evidence shows that infants whose mothers are vaccinated with Tdap during pregnancy are less likely to develop pertussis during the critical first few months of life. One study from the United Kingdom suggests that up to 90% of infants are protected against pertussis when the mother is vaccinated during pregnancy.

Studies suggest that postpartum Tdap vaccination in women is not effective in reducing pertussis in infants 6 months of age or younger.

Talk to Your Pregnant Patients about Tdap Vaccine

Your pregnant patients turn to you as a trusted prenatal care provider. A strong recommendation from you is the best predictor of vaccination that ensures children are born with protection against pertussis.

If a pregnant patient is unsure about getting the Tdap vaccine, consider using the SHARE mnemonic from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC):

- Share specific reasons why the Tdap vaccine is right for pregnant women during every pregnancy.

- Highlight positive experiences (personal or in your practice) that reinforce the benefits of the Tdap vaccine.

- Address your patient’s questions and concerns about the vaccine in plain, understandable language.

- Remind your patient that vaccines protect her and her family from many other serious diseases.

- Explain the potential costs of getting pertussis, especially for infants.

Update on Immunization and Pregnancy: Tetanus, Diphtheria, and Pertussis Vaccination

By reading this page you agree to ACOG's Terms and Conditions. Read terms

Number 718 (Replaces Committee Opinion Number 566, June 2013. Reaffirmed 2022)

Committee on Obstetric Practice

Immunization and Emerging Infections Expert Work Group

This Committee Opinion was developed by the Immunization and Emerging Infections Expert Work Group and the Committee on Obstetric Practice, with the assistance of Richard Beigi, MD.

ABSTRACT: The overwhelming majority of morbidity and mortality attributable to pertussis infection occurs in infants who are 3 months and younger. Infants do not begin their own vaccine series against pertussis until approximately 2 months of age. This leaves a window of significant vulnerability for newborns, many of whom contract serious pertussis infections from family members and caregivers, especially their mothers, or older siblings, or both. In 2013, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices published its updated recommendation that a dose of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) should be administered during each pregnancy, irrespective of the prior history of receiving Tdap. The recommended timing for maternal Tdap vaccination is between 27 weeks and 36 weeks of gestation. To maximize the maternal antibody response and passive antibody transfer and levels in the newborn, vaccination as early as possible in the 27–36-weeks-of-gestation window is recommended. However, the Tdap vaccine may be safely given at any time during pregnancy if needed for wound management, pertussis outbreaks, or other extenuating circumstances. There is no evidence of adverse fetal effects from vaccinating pregnant women with an inactivated virus or bacterial vaccine or toxoid, and a growing body of robust data demonstrate safety of such use. Adolescent and adult family members and caregivers who previously have not received the Tdap vaccine and who have or anticipate having close contact with an infant younger than 12 months should receive a single dose of Tdap to protect against pertussis. Given the rapid evolution of data surrounding this topic, immunization guidelines are likely to change over time, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists will continue to issue updates accordingly.

However, the Tdap vaccine may be safely given at any time during pregnancy if needed for wound management, pertussis outbreaks, or other extenuating circumstances. There is no evidence of adverse fetal effects from vaccinating pregnant women with an inactivated virus or bacterial vaccine or toxoid, and a growing body of robust data demonstrate safety of such use. Adolescent and adult family members and caregivers who previously have not received the Tdap vaccine and who have or anticipate having close contact with an infant younger than 12 months should receive a single dose of Tdap to protect against pertussis. Given the rapid evolution of data surrounding this topic, immunization guidelines are likely to change over time, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists will continue to issue updates accordingly.

Recommendations

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) makes the following recommendations:

Obstetric care providers should administer the tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine to all pregnant patients during each pregnancy, as early in the 27–36-weeks-of-gestation window as possible.

Pregnant women should be counseled that the administration of the Tdap vaccine during each pregnancy is safe and important to make sure that each newborn receives the highest possible protection against pertussis at birth.

Obstetrician–gynecologists are encouraged to stock and administer the Tdap vaccine in their offices.

Partners, family members, and infant caregivers should be offered the Tdap vaccine if they have not previously been vaccinated. Ideally, all family members should be vaccinated at least 2 weeks before coming in contact with the newborn.

If not administered during pregnancy, the Tdap vaccine should be given immediately postpartum if the woman has never received a prior dose of Tdap as an adolescent, adult, or during a previous pregnancy.

There are certain circumstances in which it is appropriate to administer the Tdap vaccine outside of the 27–36-weeks-of-gestation window. For example, in cases of wound management, a pertussis outbreak, or other extenuating circumstances, the need for protection from infection supercedes the benefit of administering the vaccine during the 27–36-weeks-of-gestation window.

If a pregnant woman is vaccinated early in her pregnancy (ie, before 27–36 weeks of gestation), she does not need to be vaccinated again during 27–36 weeks of gestation.

The overwhelming majority of morbidity and mortality attributable to pertussis infection occurs in infants who are 3 months and younger 1. Infants do not begin their own vaccine series against pertussis (with the diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis [DTaP] vaccine) until approximately 2 months of age (the earliest possible vaccination is at 6 weeks of age) 2. This leaves a window of significant vulnerability for newborns, many of whom contract serious pertussis infections from family members and caregivers, especially the mother, or older siblings, or both 3 4 5. Starting in 2006, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended an approach to combat neonatal pertussis infection referred to as “cocooning” 6. Cocooning is the administration of Tdap to previously unvaccinated family members and caregivers, and women in the immediate postpartum period, in order to provide a protective cocoon of immunity around the newborn. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and ACOG continue to recommend that adolescent and adult family members and caregivers who previously have not received the Tdap vaccine and who have or anticipate having close contact with an infant younger than 12 months should receive a single dose of Tdap to protect against pertussis 7. However, the cocooning approach alone is no longer the recommended approach to preventing pertussis disease in newborns (and mothers) 8.

Cocooning is the administration of Tdap to previously unvaccinated family members and caregivers, and women in the immediate postpartum period, in order to provide a protective cocoon of immunity around the newborn. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and ACOG continue to recommend that adolescent and adult family members and caregivers who previously have not received the Tdap vaccine and who have or anticipate having close contact with an infant younger than 12 months should receive a single dose of Tdap to protect against pertussis 7. However, the cocooning approach alone is no longer the recommended approach to preventing pertussis disease in newborns (and mothers) 8.

In June 2011, ACIP recommended that pregnant women receive a dose of Tdap if they have not previously received it 7. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices continued to reconsider this topic in the face of persistent increases in pertussis disease, including infant deaths 9 in the United States. Issues that were considered included an imperative to minimize the significant burden of disease in vulnerable newborns, the reassuring safety data 10 11 on use of Tdap in adults, and the evolving immunogenicity data that demonstrate considerable waning of immunity after immunization 12. In 2013, ACIP published its updated recommendation that a dose of Tdap should be administered during each pregnancy, irrespective of prior history of receiving the Tdap vaccine 7. The recommended timing for maternal Tdap vaccination is between 27 weeks and 36 weeks of gestation. To maximize the maternal antibody response and passive antibody transfer and levels in the newborn, vaccination as early as possible in the 27–36-weeks-of-gestation window is recommended. However, the Tdap vaccine may safely be given at any time during pregnancy if needed in the case of wound management, pertussis outbreaks, or other extenuating circumstances in which the need for protection from infection supercedes the benefit of administering the vaccine during the 27–36-weeks-of-gestation window.

Issues that were considered included an imperative to minimize the significant burden of disease in vulnerable newborns, the reassuring safety data 10 11 on use of Tdap in adults, and the evolving immunogenicity data that demonstrate considerable waning of immunity after immunization 12. In 2013, ACIP published its updated recommendation that a dose of Tdap should be administered during each pregnancy, irrespective of prior history of receiving the Tdap vaccine 7. The recommended timing for maternal Tdap vaccination is between 27 weeks and 36 weeks of gestation. To maximize the maternal antibody response and passive antibody transfer and levels in the newborn, vaccination as early as possible in the 27–36-weeks-of-gestation window is recommended. However, the Tdap vaccine may safely be given at any time during pregnancy if needed in the case of wound management, pertussis outbreaks, or other extenuating circumstances in which the need for protection from infection supercedes the benefit of administering the vaccine during the 27–36-weeks-of-gestation window. Additional data available since 2013 increasingly demonstrate that administration of Tdap during the late second or early third trimester (with at least 2 weeks from the time of vaccination to delivery) is highly effective in protecting against neonatal pertussis 13 14 15 16. In addition, even when maternal vaccination is not completely protective, infants with pertussis whose mothers received Tdap during pregnancy had significantly less morbidity, including risk of hospitalization and intensive care unit admission 13. Safety data also continue to be reassuring, including when women receive successive Tdap immunizations over a relatively short time because of short-interval pregnancies. New data demonstrate that immunizing against Tdap early within the 27–36-weeks-of-gestation window maximizes the maternal antibody response and passive antibody transfer to the fetus 17. Therefore, giving the Tdap vaccine as early as possible in the 27–36-weeks-of-gestation window appears to be the best strategy 18 19.

Additional data available since 2013 increasingly demonstrate that administration of Tdap during the late second or early third trimester (with at least 2 weeks from the time of vaccination to delivery) is highly effective in protecting against neonatal pertussis 13 14 15 16. In addition, even when maternal vaccination is not completely protective, infants with pertussis whose mothers received Tdap during pregnancy had significantly less morbidity, including risk of hospitalization and intensive care unit admission 13. Safety data also continue to be reassuring, including when women receive successive Tdap immunizations over a relatively short time because of short-interval pregnancies. New data demonstrate that immunizing against Tdap early within the 27–36-weeks-of-gestation window maximizes the maternal antibody response and passive antibody transfer to the fetus 17. Therefore, giving the Tdap vaccine as early as possible in the 27–36-weeks-of-gestation window appears to be the best strategy 18 19. Linking the Tdap vaccination to screening for gestational diabetes will allow this to be implemented easily. For women who are Rh negative, another strategy worth consideration is to administer Tdap vaccination during the same visit as Rho(D) immune globulin administration.

Linking the Tdap vaccination to screening for gestational diabetes will allow this to be implemented easily. For women who are Rh negative, another strategy worth consideration is to administer Tdap vaccination during the same visit as Rho(D) immune globulin administration.

Receipt of Tdap between 27 weeks and 36 weeks of gestation in each pregnancy is critical. For women who have never received a prior dose of Tdap, if Tdap was not administered during pregnancy, it should be administered immediately postpartum in order to reduce the risk of transmission to the newborns 7. A woman who did not receive the Tdap vaccine during her most recent pregnancy, but received it previously as an adolescent, adult, or during a prior pregnancy should not receive Tdap postpartum. Additionally, adolescent and adult family members and planned caregivers who have not received the Tdap vaccine also should receive Tdap at least 2 weeks before planned infant contact, as previously recommended (sustained efforts at cocooning) 6. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Immunization and Emerging Infections Expert Work Group and Committee on Obstetric Practice support these recommendations. Pregnant women should be counseled that Tdap vaccination during each pregnancy is safe and important to make sure that each newborn receives the highest possible protection against pertussis at birth. Since protection from previous vaccination is likely to decrease over time, a Tdap vaccination is necessary during every pregnancy to give the best possible protection to the newborn.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Immunization and Emerging Infections Expert Work Group and Committee on Obstetric Practice support these recommendations. Pregnant women should be counseled that Tdap vaccination during each pregnancy is safe and important to make sure that each newborn receives the highest possible protection against pertussis at birth. Since protection from previous vaccination is likely to decrease over time, a Tdap vaccination is necessary during every pregnancy to give the best possible protection to the newborn.

Data consistently demonstrate that when a physician recommends and offers a vaccine on site the rate of vaccine acceptance is significantly higher than when physicians either do not recommend, or recommend but do not offer the vaccine 20. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists encourages obstetrician–gynecologists and other obstetric care providers to strongly recommend and offer Tdap vaccination to all pregnant women between 27 weeks and 36 weeks of gestation in each pregnancy. Additionally, efforts to stock the Tdap vaccine in the obstetrician–gynecologist’s or other health care provider’s office and administer it as early in the recommended window as possible offers the best chance of vaccine acceptance and neonatal protection. Depending on the size of a practice and services provided, there may not be the means to supply and offer the Tdap vaccine in the office. If the Tdap vaccine cannot be offered in a practice, patients should be referred to another health care provider when possible. For example, pharmacists are well equipped to give immunizations, and the Tdap vaccine is available at most major pharmacies. If patients receive the Tdap vaccine outside of the obstetrician–gynecologist’s office, it is important for them to provide proper vaccine documentation so a patient’s immunization record can be updated. Given the rapid evolution of data surrounding this topic, immunization guidelines are likely to change over time, and ACOG will continue to issue updates accordingly.

Additionally, efforts to stock the Tdap vaccine in the obstetrician–gynecologist’s or other health care provider’s office and administer it as early in the recommended window as possible offers the best chance of vaccine acceptance and neonatal protection. Depending on the size of a practice and services provided, there may not be the means to supply and offer the Tdap vaccine in the office. If the Tdap vaccine cannot be offered in a practice, patients should be referred to another health care provider when possible. For example, pharmacists are well equipped to give immunizations, and the Tdap vaccine is available at most major pharmacies. If patients receive the Tdap vaccine outside of the obstetrician–gynecologist’s office, it is important for them to provide proper vaccine documentation so a patient’s immunization record can be updated. Given the rapid evolution of data surrounding this topic, immunization guidelines are likely to change over time, and ACOG will continue to issue updates accordingly.

General Considerations Surrounding Immunization During Pregnancy

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends routine assessment of each pregnant woman’s immunization status and administration of indicated immunizations. Importantly, evolving data demonstrate maternal and neonatal protection against an increasing number of aggressive newborn pathogens through the use of maternal immunization, suggesting pregnancy is an optimal time to immunize for disease prevention in women and newborns 13 14 15 16 21 22. There is no evidence of adverse fetal effects from vaccinating pregnant women with an inactivated virus or bacterial vaccines or toxoids, and a growing body of robust data demonstrate safety of such use 11. Concomitant administration of indicated inactivated vaccines during pregnancy (ie, Tdap and influenza) is also acceptable, safe, and may optimize effectiveness of immunization efforts 10. Furthermore, no evidence exists that suggests that any vaccine is associated with an increased risk of autism or adverse effects due to exposure to traces of the mercury-containing preservative thimerosal 23 24 25 26. The Tdap vaccines do not contain thimerosal. The benefits of inactivated vaccines outweigh any unproven potential concerns. It is important to remember that live attenuated vaccines (eg, measles–mumps–rubella [MMR], varicella, and live attenuated influenza vaccine) do pose a theoretical risk (although never documented or proved) to the fetus and generally should be avoided during pregnancy. All vaccines administered during pregnancy as well as health care provider-driven discussions about the indications and benefits of immunization during pregnancy should be fully documented in the patient’s prenatal record. In addition, if a patient declines vaccination, this refusal should be documented in the patient’s prenatal record, and the health care provider is advised to revisit the issue of vaccination at subsequent visits.

The Tdap vaccines do not contain thimerosal. The benefits of inactivated vaccines outweigh any unproven potential concerns. It is important to remember that live attenuated vaccines (eg, measles–mumps–rubella [MMR], varicella, and live attenuated influenza vaccine) do pose a theoretical risk (although never documented or proved) to the fetus and generally should be avoided during pregnancy. All vaccines administered during pregnancy as well as health care provider-driven discussions about the indications and benefits of immunization during pregnancy should be fully documented in the patient’s prenatal record. In addition, if a patient declines vaccination, this refusal should be documented in the patient’s prenatal record, and the health care provider is advised to revisit the issue of vaccination at subsequent visits.

Special Situations During Pregnancy

Ongoing Epidemics

Pregnant women who live in geographic regions with new outbreaks or epidemics of pertussis should be immunized as soon as feasibly possible for their own protection in accordance with local recommendations for nonpregnant adults. In these acute situations, less emphasis should be given to targeting the proposed optimal gestation window (between 27 weeks and 36 weeks of gestation) given the imperative to protect the woman from locally prevalent disease. Newborn protection will still be garnered from vaccination earlier in the same pregnancy. Importantly, a pregnant woman should not be revaccinated later in the same pregnancy if she received the vaccine in the first or second trimester 7.

In these acute situations, less emphasis should be given to targeting the proposed optimal gestation window (between 27 weeks and 36 weeks of gestation) given the imperative to protect the woman from locally prevalent disease. Newborn protection will still be garnered from vaccination earlier in the same pregnancy. Importantly, a pregnant woman should not be revaccinated later in the same pregnancy if she received the vaccine in the first or second trimester 7.

Example case: A pregnant woman at 8 weeks of gestation with one kindergarten-aged child at home calls the office and mentions that pertussis has recently been diagnosed in four different children by their pediatricians in her neighborhood. She is not sure what to do and has heard that she is supposed to get a Tdap vaccination in the third trimester. How should you best manage this patient?

Answer: Advise her to come that day and receive the Tdap vaccine in your office. She should be reassured that Tdap vaccination is safe to give at any point in pregnancy and that getting the vaccine now will directly protect her, indirectly protect her fetus, and also will offer some protection for her newborn from pertussis. She will only need to receive the Tdap vaccine once during pregnancy. All other adolescent and adult family members also should be advised to make sure they are up-to-date with their Tdap vaccine to ensure protection for themselves and the newborn.

She will only need to receive the Tdap vaccine once during pregnancy. All other adolescent and adult family members also should be advised to make sure they are up-to-date with their Tdap vaccine to ensure protection for themselves and the newborn.

Wound Management

As part of standard wound management care to prevent tetanus, a tetanus toxoid-containing vaccine is recommended in a pregnant woman if 5 years or more have elapsed since her previous tetanus and diphtheria (Td) vaccination. If a Td booster vaccination is indicated in a pregnant woman for acute wound management, the obstetrician–gynecologist or other health care provider should administer the Tdap vaccine, irrespective of gestational age 7. A pregnant woman should not be revaccinated with Tdap in the same pregnancy if she received the vaccine in the first or second trimester.

Example case: An emergency department (ED) physician calls you about a patient, gravida 4, para 3, at 13 weeks of gestation who is being seen after accidentally stepping on a rusty nail. The patient cannot remember when she last received a tetanus booster and the ED physician is confused about when to administer the indicated tetanus booster because the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines recommend the administration of Tdap between 27 weeks and 36 weeks of gestation. How should you advise the ED physician?

The patient cannot remember when she last received a tetanus booster and the ED physician is confused about when to administer the indicated tetanus booster because the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines recommend the administration of Tdap between 27 weeks and 36 weeks of gestation. How should you advise the ED physician?

Answer: The ED physician should be advised that the appropriate acute wound management strategy for the patient is to receive a dose of Tdap now. This vaccine replaces the solitary tetanus booster vaccine, and administering it now as part of acute wound management is the most important factor. The patient should be told that getting Tdap now will preclude her getting it again between 27 weeks and 36 weeks of gestation in this pregnancy. She and her fetus will still receive pertussis prevention benefits from receipt at 13 weeks of gestation.

Indicated Tetanus and Diphtheria Booster Vaccination

If a Td booster vaccination is indicated during pregnancy (ie, more than 10 years since the previous Td vaccination) then obstetrician–gynecologists and other health care providers should administer the Tdap vaccine during pregnancy within the 27–36-weeks-of-gestation window 7. This recommendation is because of the nonurgent nature of this indication and the desire for maternal immunity. It also will maximize antibody transfer to the newborn.

This recommendation is because of the nonurgent nature of this indication and the desire for maternal immunity. It also will maximize antibody transfer to the newborn.

Unknown or Incomplete Tetanus Vaccination

To ensure protection against maternal and neonatal tetanus, pregnant women who have never been vaccinated against tetanus should begin the three-vaccination series, containing tetanus and reduced diphtheria toxoids, during pregnancy. The recommended schedule for this vaccine series is at 0 weeks, 4 weeks, and 6–12 months. The Tdap vaccine should replace one dose of Td, preferably given between 27 weeks and 36 weeks of gestation 7.

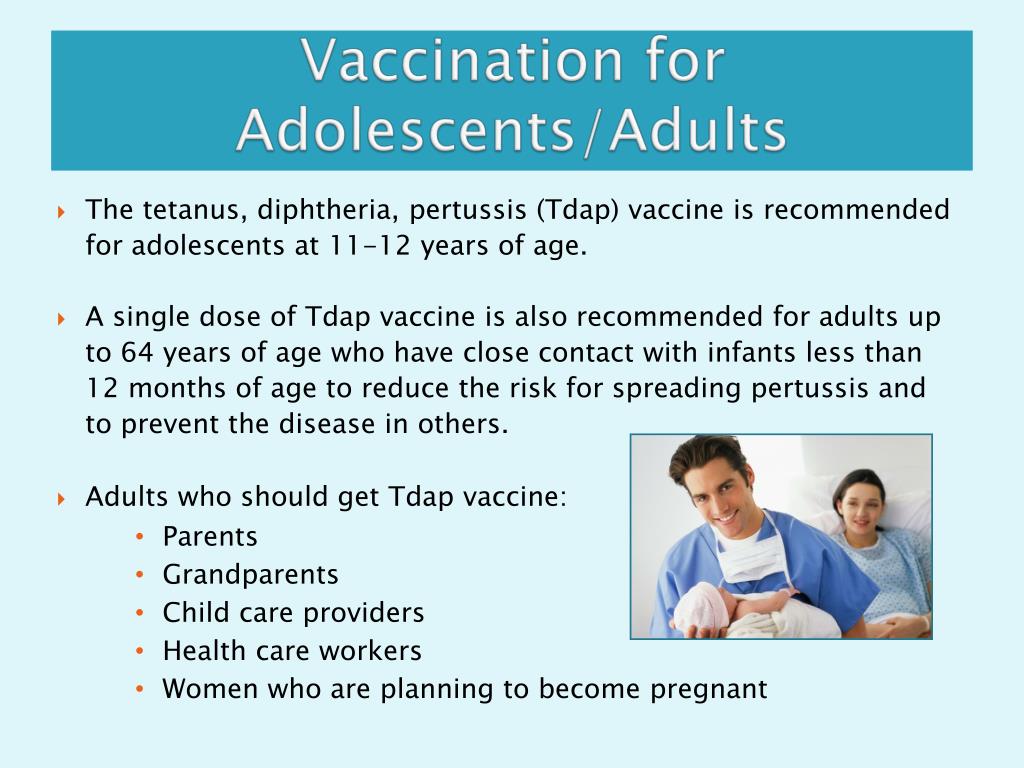

Vaccination of Adolescents and Adults in Contact With Infants

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends that all adolescents and adults who have or who anticipate having close contact with an infant younger than 12 months (eg, siblings, parents, grandparents, child care providers, and health care providers) who previously have not received the Tdap vaccine should receive a single dose of Tdap to protect against pertussis and reduce the likelihood of transmission 7. Ideally, these adolescents and adults should receive the Tdap vaccine at least 2 weeks before they have close contact with the infant 6.

Ideally, these adolescents and adults should receive the Tdap vaccine at least 2 weeks before they have close contact with the infant 6.

For More Information

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has identified additional resources on topics related to this document that may be helpful for ob-gyns, other health care providers, and patients. You may view these resources at: www.acog.org/More-Info/Tdap.

These resources are for information only and are not meant to be comprehensive. Referral to these resources does not imply the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ endorsement of the organization, the organization’s website, or the content of the resource. The resources may change without notice.

References

- Van Rie A, Wendelboe AM, Englund JA. Role of maternal pertussis antibodies in infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2005;24:S62–5.

Article Locations:Article Location

- Robinson CL, Romero JR, Kempe A, Pellegrini C.

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for children and adolescents aged 18 years or younger—United States, 2017. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Child/Adolescent Immunization Work Group. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:134–5.

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for children and adolescents aged 18 years or younger—United States, 2017. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Child/Adolescent Immunization Work Group. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:134–5.

Article Locations:Article Location

- Bisgard KM, Pascual FB, Ehresmann KR, Miller CA, Cianfrini C, Jennings CE, et al. Infant pertussis: who was the source? Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004;23:985–9.

Article Locations:Article Location

- Skoff TH, Kenyon C, Cocoros N, Liko J, Miller L, Kudish K, et al. Sources of infant pertussis infection in the United States. Pediatrics 2015;136:635–41.

Article Locations:Article Location

- Wiley KE, Zuo Y, Macartney KK, McIntyre PB. Sources of pertussis infection in young infants: a review of key evidence informing targeting of the cocoon strategy. Vaccine 2013;31:618–25.

Article Locations:Article Location

- Murphy TV, Slade BA, Broder KR, Kretsinger K, Tiwari T, Joyce PM, et al.

Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria among pregnant and postpartum women and their infants: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [published erratum appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008;57:723]. MMWR Recomm Rep 2008;57(RR-4):1–51.

Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria among pregnant and postpartum women and their infants: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [published erratum appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008;57:723]. MMWR Recomm Rep 2008;57(RR-4):1–51.

Article Locations:Article LocationArticle LocationArticle Location

- Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2012. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013;62:131–5.

Article Locations:Article LocationArticle LocationArticle LocationArticle LocationArticle LocationArticle LocationArticle LocationArticle LocationArticle Location

- Blain AE, Lewis M, Banerjee E, Kudish K, Liko J, McGuire S, et al. An assessment of the cocooning strategy for preventing infant pertussis—United States, 2011.

Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:S221–6.

Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:S221–6.

Article Locations:Article Location

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis outbreak trends. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/outbreaks/trends.html. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

Article Locations:Article Location

- Sukumaran L, McCarthy NL, Kharbanda EO, Weintraub ES, Vazquez-Benitez G, McNeil MM, et al. Safety of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis and influenza vaccinations in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:1069–74.

Article Locations:Article LocationArticle Location

- McMillan M, Clarke M, Parrella A, Fell DB, Amirthalingam G, Marshall HS. Safety of tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis vaccination during pregnancy: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:560–73.

Article Locations:Article LocationArticle Location

- Healy CM, Rench MA, Baker CJ. Importance of timing of maternal combined tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) immunization and protection of young infants.

Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:539–44.

Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:539–44.

Article Locations:Article Location

- Winter K, Cherry JD, Harriman K. Effectiveness of prenatal tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccination on pertussis severity in infants. Clin Infect Dis 2017;64:9–14.

Article Locations:Article LocationArticle LocationArticle Location

- Winter K, Nickell S, Powell M, Harriman K. Effectiveness of prenatal versus postpartum tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccination in preventing infant pertussis. Clin Infect Dis 2017;64:3–8.

Article Locations:Article LocationArticle Location

- Dabrera G, Amirthalingam G, Andrews N, Campbell H, Ribeiro S, Kara E, et al. A case-control study to estimate the effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in protecting newborn infants in England and Wales, 2012–2013. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60:333–7.

Article Locations:Article LocationArticle Location

- Baxter R, Bartlett J, Fireman B, Lewis E, Klein NP.

Effectiveness of vaccination during pregnancy to prevent infant pertussis. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20164091.

Effectiveness of vaccination during pregnancy to prevent infant pertussis. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20164091.

Article Locations:Article LocationArticle Location

- Abu Raya B, Srugo I, Kessel A, Peterman M, Bader D, Gonen R, et al. The effect of timing of maternal tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) immunization during pregnancy on newborn pertussis antibody levels — a prospective study. Vaccine 2014;32:5787–93.

Article Locations:Article Location

- Naidu MA, Muljadi R, Davies-Tuck ML, Wallace EM, Giles ML. The optimal gestation for pertussis vaccination during pregnancy: a prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215:237.e1–e6.

Article Locations:Article Location

- Kent A, Ladhani SN, Andrews NJ, Matheson M, England A, Miller E, et al. Pertussis antibody concentrations in infants born prematurely to mothers vaccinated in pregnancy. PUNS study group. Pediatrics 2016;138:e20153854.

Article Locations:Article Location

- Ding H, Black CL, Ball S, Donahue S, Fink RV, Williams WW, et al.

Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women—United States, 2014–15 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:1000–5.

Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women—United States, 2014–15 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:1000–5.

Article Locations:Article Location

- Zaman K, Roy E, Arifeen SE, Rahman M, Raqib R, Wilson E, et al. Effectiveness of maternal influenza immunization in mothers and infants [published erratum appears in N Engl J Med 2009;360:648]. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1555–64.

Article Locations:Article Location

- Vandelaer J, Birmingham M, Gasse F, Kurian M, Shaw C, Garnier S. Tetanus in developing countries: an update on the Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus Elimination Initiative. Vaccine 2003;21:3442–5.

Article Locations:Article Location

- Thompson WW, Price C, Goodson B, Shay DK, Benson P, Hinrichsen VL, et al. Early thimerosal exposure and neuropsychological outcomes at 7 to 10 years. Vaccine Safety Datalink Team. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1281–92.

Article Locations:Article Location

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Thimerosal in vaccines. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/concerns/thimerosal. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

Thimerosal in vaccines. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/concerns/thimerosal. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

Article Locations:Article Location

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Thimerosal in vaccines. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/SafetyAvailability/VaccineSafety/UCM09622. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

Article Locations:Article Location

- Joint statement of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the United States Public Health Service (USPHS). Pediatrics 1999;104:568–9.

Article Locations:Article Location

Copyright September 2017 by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, posted on the Internet, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher.

Requests for authorization to make photocopies should be directed to Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400.

ISSN 1074-861X

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 409 12th Street, SW, PO Box 96920, Washington, DC 20090-6920

Update on immunization and pregnancy: tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis vaccination. Committee Opinion No. 718. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:e153–7.

This information is designed as an educational resource to aid clinicians in providing obstetric and gynecologic care, and use of this information is voluntary. This information should not be considered as inclusive of all proper treatments or methods of care or as a statement of the standard of care. It is not intended to substitute for the independent professional judgment of the treating clinician. Variations in practice may be warranted when, in the reasonable judgment of the treating clinician, such course of action is indicated by the condition of the patient, limitations of available resources, or advances in knowledge or technology. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists reviews its publications regularly; however, its publications may not reflect the most recent evidence. Any updates to this document can be found on www.acog.org or by calling the ACOG Resource Center.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists reviews its publications regularly; however, its publications may not reflect the most recent evidence. Any updates to this document can be found on www.acog.org or by calling the ACOG Resource Center.

While ACOG makes every effort to present accurate and reliable information, this publication is provided “as is” without any warranty of accuracy, reliability, or otherwise, either express or implied. ACOG does not guarantee, warrant, or endorse the products or services of any firm, organization, or person. Neither ACOG nor its officers, directors, members, employees, or agents will be liable for any loss, damage, or claim with respect to any liabilities, including direct, special, indirect, or consequential damages, incurred in connection with this publication or reliance on the information presented.

Topics

Morbidity Pregnancy Pregnant women Immunization Diphtheria-Tetanus-acellular Pertussis vaccines

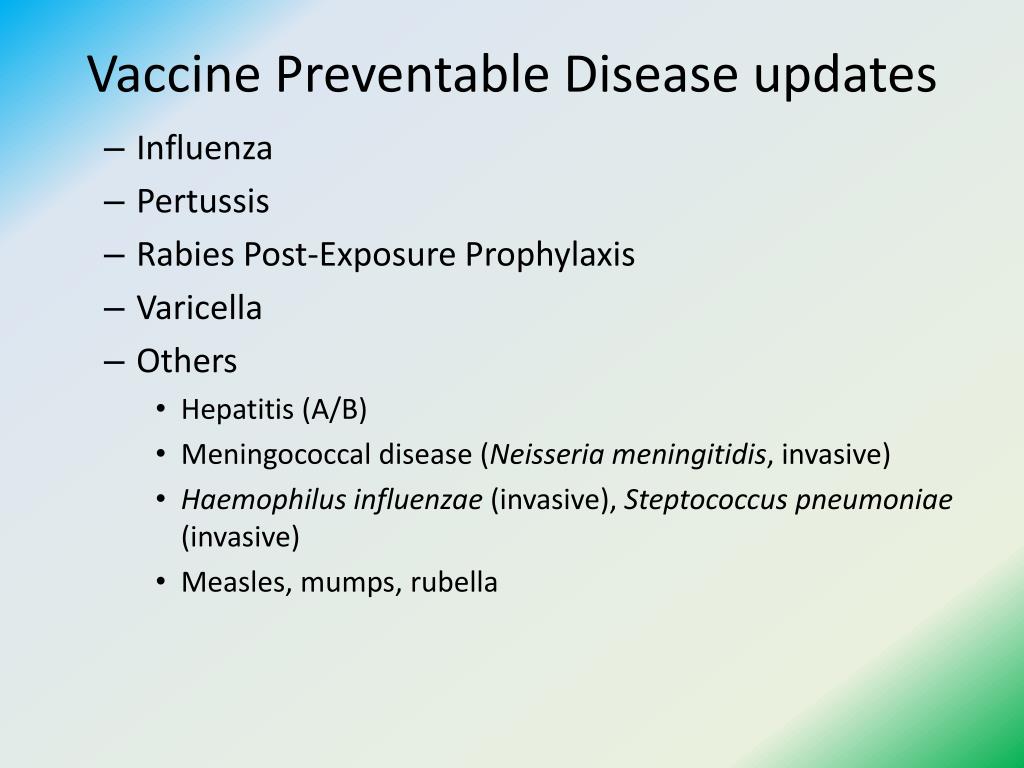

Fomin's clinic - a network of multidisciplinary clinics

You probably know that in the modern world there is a fierce struggle. And this is not about military conflicts or political strife, but about clashes between supporters of vaccination and anti-vaccinationists who claim that vaccination is a real universal evil that causes irreparable consequences - pathologies and disorders. Nevertheless, pregnant women and newborns are the most vulnerable groups, which can be taken care of by timely vaccination.

And this is not about military conflicts or political strife, but about clashes between supporters of vaccination and anti-vaccinationists who claim that vaccination is a real universal evil that causes irreparable consequences - pathologies and disorders. Nevertheless, pregnant women and newborns are the most vulnerable groups, which can be taken care of by timely vaccination.

What diseases should a pregnant woman be vaccinated against?

Pregnancy is stressful for the body, and therefore it functions differently than before or after it. It is because of a weakened immune system that the risk of severe influenza in pregnant women is much higher than in non-pregnant women. Influenza can not only cause premature birth, but also harm the health of the unborn baby.

Influenza vaccination is strongly recommended by all world medical organizations (including the well-known World Health Organization). There are controversial opinions about vaccination in the first trimester, therefore, if it does not fall in autumn or winter - the most dangerous months for the active spread of the disease, it is better to get vaccinated in the II-III trimester.

Get vaccinated

When you get vaccinated against influenza, it primarily has a preventive effect directly for you - the expectant mother, but the whooping cough vaccine is about taking care of the baby's health. The woman who received the vaccine will pass antibodies to the child in utero - and this will save him from the disease in the first months of life, because for the newborn it can be fatal.

Whooping cough is difficult to recognize immediately, because it does not always manifest itself with a characteristic cough - at one moment breathing can simply stop, although there were no visible symptoms. For your baby's safety, you should get the whooping cough vaccine (along with diphtheria and tetanus) during every pregnancy - best done in the third trimester.

No, not dangerous.

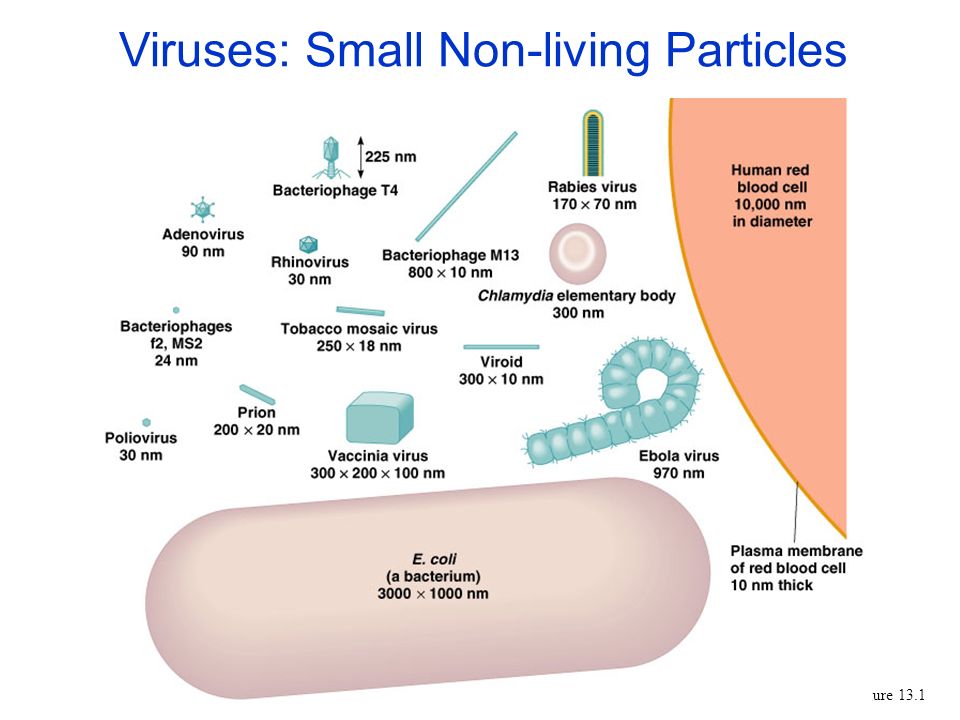

There is a myth that you can get the flu after vaccination. It is impossible to catch the flu from a vaccine, since the vaccine does not contain the whole virus, but only its parts - antigens. Antibodies are produced against these antigens, our defending cells. And the next time our body encounters a virus, already real, our antibodies will actively destroy the viral particles.

Antibodies are produced against these antigens, our defending cells. And the next time our body encounters a virus, already real, our antibodies will actively destroy the viral particles.

Many people do not consider it necessary to get vaccinated because they think that the vaccine protects against only a few strains of influenza, and there are many. But every year the vaccine contains precisely the actual strains for this season and this territory. So mass vaccination forms a stable herd immunity. Immunity after vaccination lasts for a year, so the flu shot is annual.

In some cases, pregnant women need additional vaccinations:

Vaccination against hepatitis B. The immunobiological preparation does not contain live or whole virus. According to medical research and statistics, this hepatitis shot is safe for a child. However, the vaccine is recommended for expectant mothers who are at risk of infection with this type of hepatitis (for example, if a loved one is infected). If the likelihood of the disease increases, then the pregnant woman is given emergency vaccination and a specific immunoglobulin is administered.

If the likelihood of the disease increases, then the pregnant woman is given emergency vaccination and a specific immunoglobulin is administered.

Vaccination against hepatitis A. Hepatitis A can be contracted through contact with objects that contain the virus, after drinking contaminated water or food. The immunobiological preparation contains an inactivated virus, and therefore the likelihood of its negative effect on the fetus is minimal. Vaccination is carried out if the risk of infection increases. This is possible if a pregnant woman enters a region unfavorable for hepatitis A or doctors suspect that contact with the virus has already taken place. In some cases, normal human immunoglobulin is given with the vaccine.

Rabies vaccination. Infection usually occurs after the bite of a sick animal. The rabies virus is quite strong and dangerous, with the development of the disease provokes death. It is for this reason that rabies vaccination is an urgent and necessary measure. The vaccine contains an inactivated virus, so the drug is considered safe for the fetus. If the bites and injuries are severe, then the victim is injected with a specific immunoglobulin.

The vaccine contains an inactivated virus, so the drug is considered safe for the fetus. If the bites and injuries are severe, then the victim is injected with a specific immunoglobulin.

Meningococcal vaccination may also be recommended by a doctor during pregnancy in the event of a meningococcal outbreak or if traveling to an area endemic for meningococcal disease.

The possibility of vaccinating a pregnant woman against pneumococcal infection may be considered by a doctor for women who have chronic respiratory diseases during the II-III trimesters of pregnancy.

Pregnant women are not vaccinated if the vaccine contains live attenuated

cultures of pathogens. These drugs include vaccines: measles, rubella, chicken pox, mumps, BCG.

In order to protect yourself and your baby from possible infectious dangers, it is necessary to get the necessary vaccinations before pregnancy.

If the risk of getting sick appeared during pregnancy (the pregnant woman was not vaccinated on time and there was contact with the patient), then specific prophylaxis is carried out with immunoglobulins.

In our clinic, also, when planning a pregnancy, it is possible to vaccinate MMR (measles, mumps, rubella vaccine) - a combined attenuated live vaccine against infections: mumps, rubella and measles.

Follow us

Vaccination of pregnant women

When planning a pregnancy, you need to review the vaccination history of the expectant mother. If not, tests to determine the level of protective antibodies should be performed. Based on the vaccination history and test results, the doctor will prescribe the necessary immunizations before pregnancy. If you need measles, mumps, rubella, or chickenpox vaccines, be sure to get them at least 1 month before pregnancyRecommended vaccines during pregnancy

The CDC (US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) recommends that all pregnant women receive the inactivated influenza vaccine at any time during pregnancy and the pertussis vaccine (Tdap Adacel) at the beginning of the third trimester during each pregnancy. The flu and whooping cough can be fatal, especially in the first few months of a child's life. Vaccinating women against these diseases during each pregnancy helps protect both themselves and their babies. Studies show flu and whooping cough vaccines are safe for pregnant women and developing children

The flu and whooping cough can be fatal, especially in the first few months of a child's life. Vaccinating women against these diseases during each pregnancy helps protect both themselves and their babies. Studies show flu and whooping cough vaccines are safe for pregnant women and developing children Vaccination of pregnant women in special cases

The decision to vaccinate in special cases is made by the attending physician and the pregnant woman based on an assessment of the likelihood of infection and the risk to the mother and fetus from both the disease and vaccination. This should be guided by international recommendations on immunization of pregnant women (for example, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices)Basic information on vaccination of pregnant women under special conditions

Hepatitis A Data on the safety of vaccination during pregnancy have not been established. The theoretical risk to the fetus is low, it is necessary to compare the risk of vaccination and the risk of infection (it is necessary to discuss with your doctor if you are at risk)Hepatitis B

There is limited data on the safety of hepatitis B vaccination during pregnancy. If there is a risk of infection during pregnancy, vaccination is necessary (need to discuss with your doctor if you are at risk)

If there is a risk of infection during pregnancy, vaccination is necessary (need to discuss with your doctor if you are at risk) Human papillomavirus (HPV)

HPV vaccines are not recommended for pregnant women. However, if the vaccine dose was administered during pregnancy, no intervention is required. Next, the series of vaccines should be postponed until the end of pregnancy.Measles, mumps, rubella

Vaccines should not be given to women who are pregnant or trying to become pregnant. Pregnancy should also be avoided for 28 days after vaccinationMeningococcal disease

There is limited data on the safety of meningococcal vaccination during pregnancy. Pregnant women who are at risk of infection during pregnancy may be vaccinated (need to discuss with your doctor if you are at risk)Pneumococcal infection

There is limited data on the safety of pneumococcal vaccine (PPSV23) during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy.

Pregnant women who are at risk may be vaccinated (need to discuss with your doctor if you are at risk). There are no recommendations for the use of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) in pregnant women.

Pregnant women who are at risk may be vaccinated (need to discuss with your doctor if you are at risk). There are no recommendations for the use of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) in pregnant women. Hemophilus vaccination

There is limited data on the safety of Haemophilus influenzae vaccination during the third trimester of pregnancy. Pregnant women who are at risk may be vaccinated (need to discuss with your doctor if you are at risk)Poliomyelitis (IPV/OPV) In theory, vaccination of pregnant women should be avoided, although no side effects of IPV have been reported in pregnant women and their fetuses. If there is an increased risk of infection and immediate protection against polio is needed, IPV can be given according to the recommended schedules for adults (need to discuss with your doctor if you are at risk)

Chickenpox

Chickenpox vaccines should not be given to women who are pregnant or trying to get pregnantYellow fever

Live yellow fever vaccine is not contraindicated during pregnancy.