Pelvic floor dysfunction pregnancy

Pelvic Floor Dysfunction: Symptoms, Causes & Treatment

Overview

What is pelvic floor dysfunction?

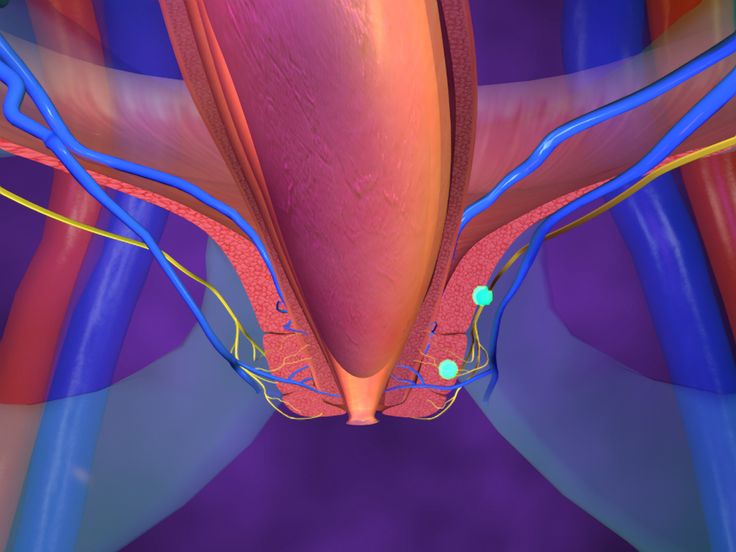

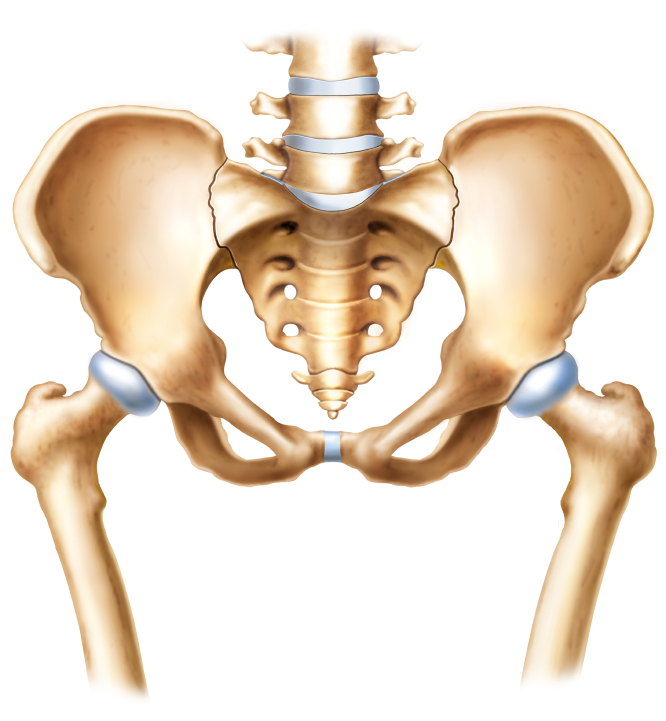

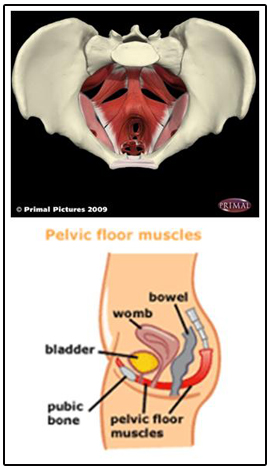

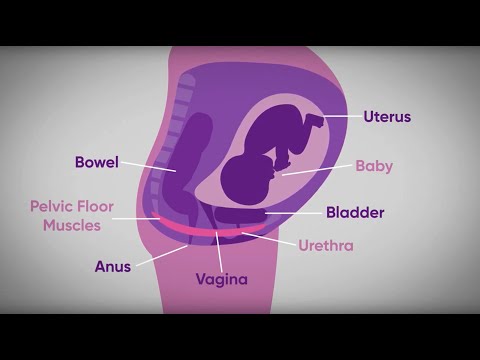

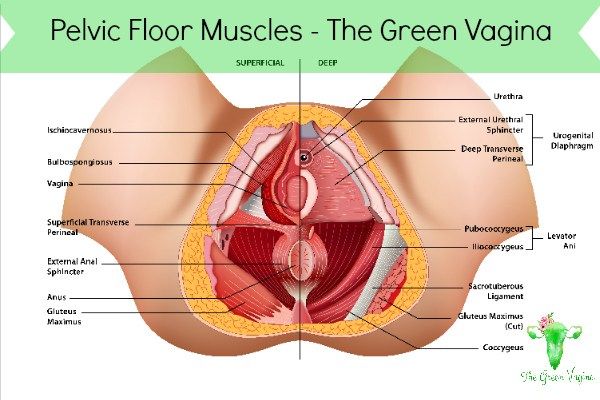

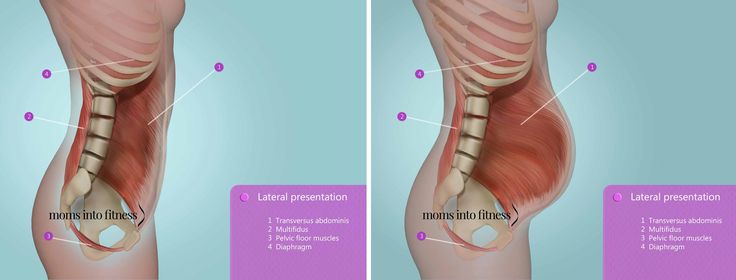

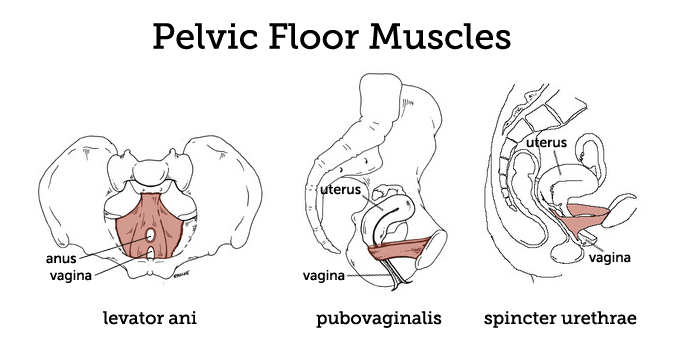

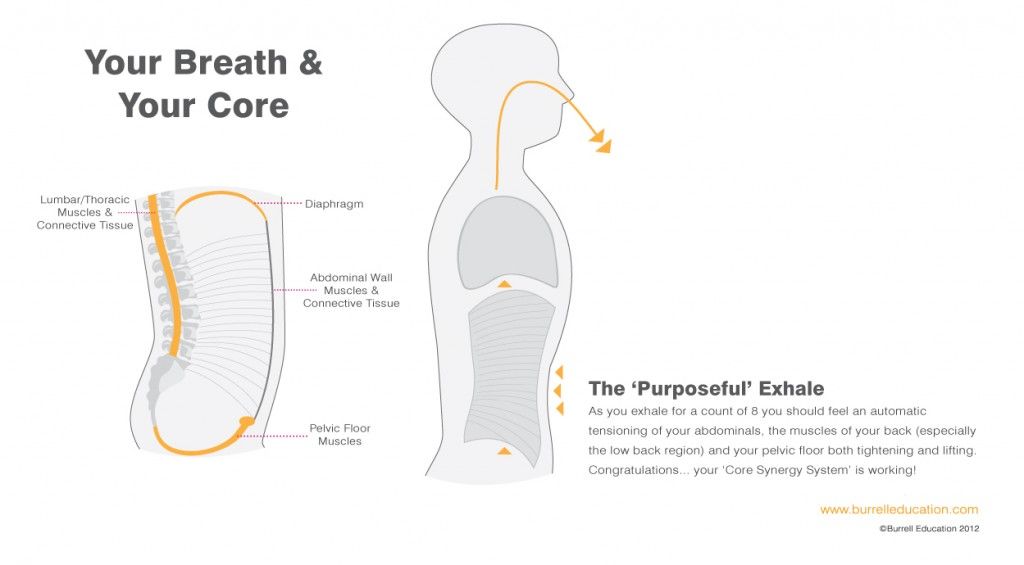

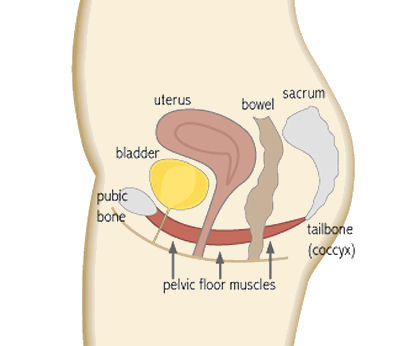

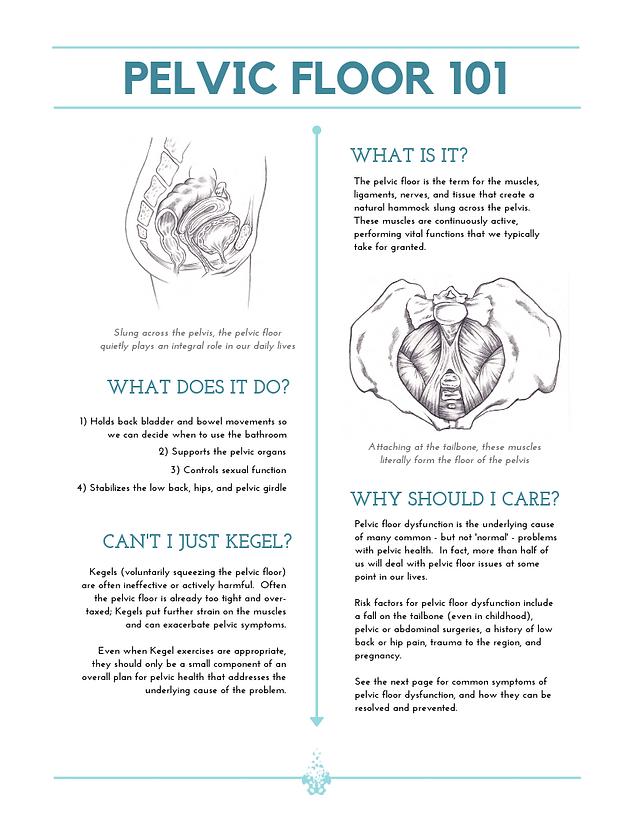

Pelvic floor dysfunction is a common condition where you’re unable to correctly relax and coordinate the muscles in your pelvic floor to urinate or to have a bowel movement. If you’re a woman, you may also feel pain during sex, and if you’re a man you may have problems having or keeping an erection (erectile dysfunction or ED). Your pelvic floor is a group of muscles found in the floor (the base) of your pelvis (the bottom of your torso).

If you think of the pelvis as being the home to organs like the bladder, uterus (or prostate in men) and rectum, the pelvic floor muscles are the home’s foundation. These muscles act as the support structure keeping everything in place within your body. Your pelvic floor muscles add support to several of your organs by wrapping around your pelvic bone. Some of these muscles add more stability by forming a sling around the rectum.

The pelvic organs include:

- The bladder (the pouch holding your urine).

- The uterus and vagina (in women).

- The prostate (in men).

- The rectum (the area at the end of the large intestine where your body stores solid waste).

Normally, you’re able to go to the bathroom with no problem because your body tightens and relaxes its pelvic floor muscles. This is just like any other muscular action, like tightening your biceps when you lift a heavy box or clenching your fist.

But if you have pelvic floor dysfunction, your body keeps tightening these muscles instead of relaxing them like it should. This tension means you may have:

- Trouble evacuating (releasing) a bowel movement.

- An incomplete bowel movement.

- Urine or stool that leaks.

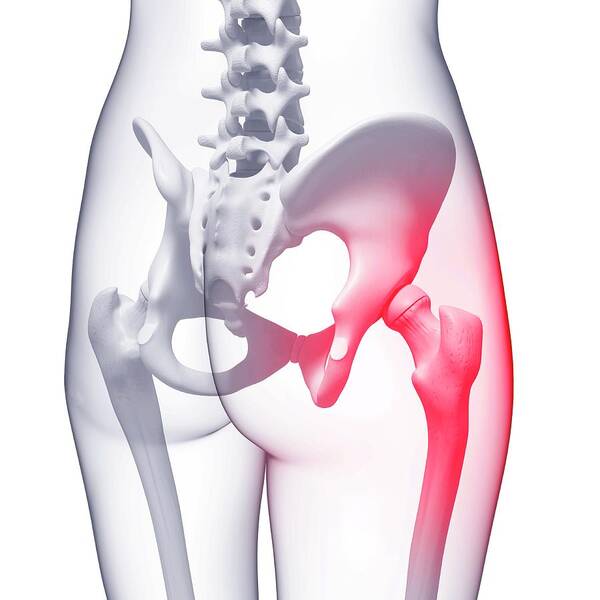

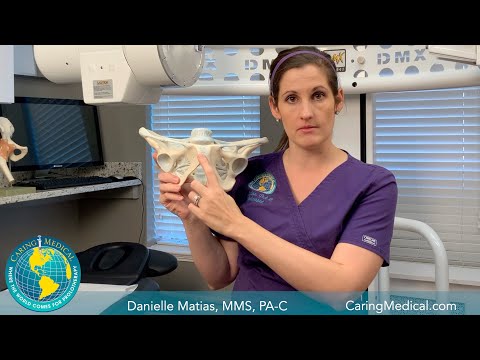

Pelvic floor muscles (female)

Pelvic floor muscles (male)

Symptoms and Causes

What causes pelvic floor dysfunction?

The full causes of pelvic floor dysfunction are still unknown. But a few of the known factors include:

But a few of the known factors include:

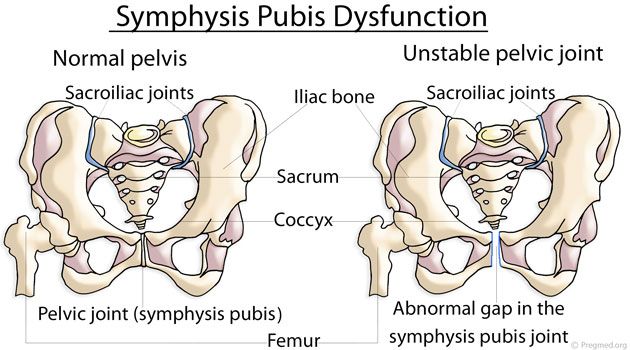

- Traumatic injuries to the pelvic area (like a car accident).

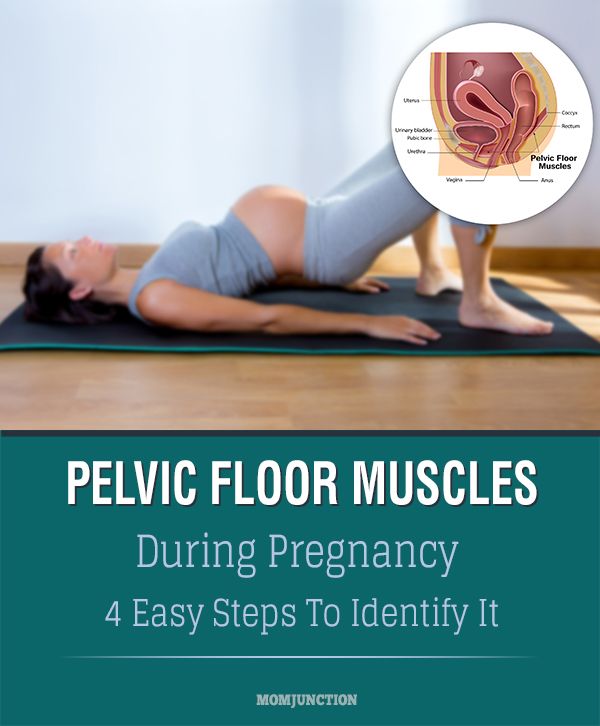

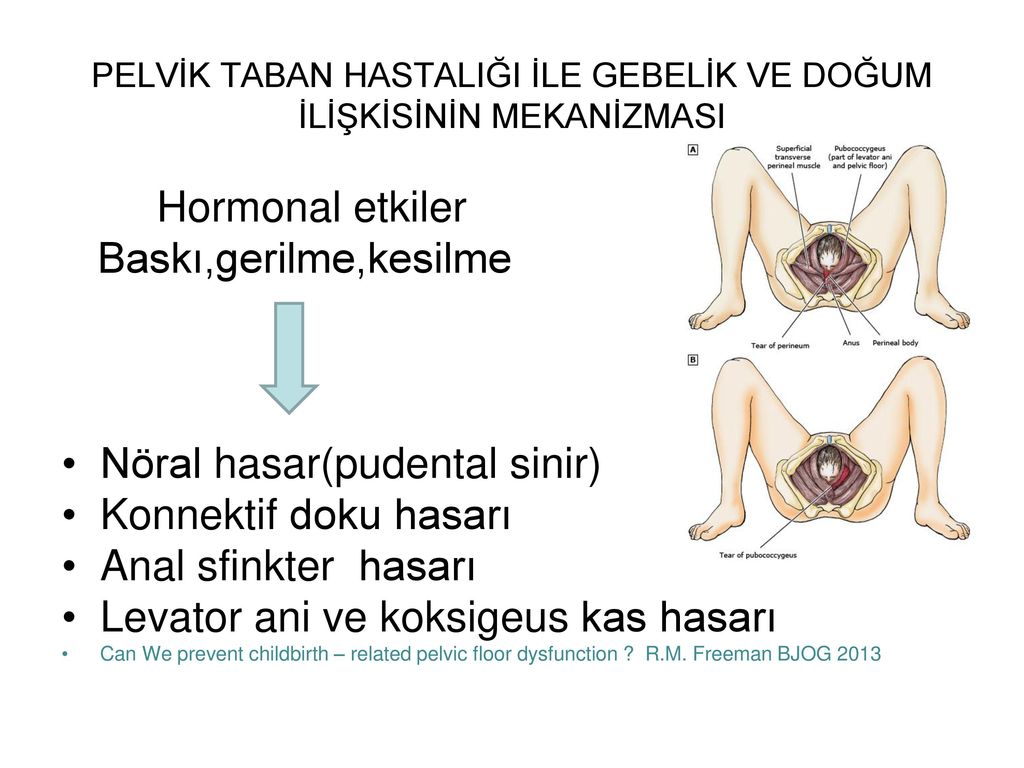

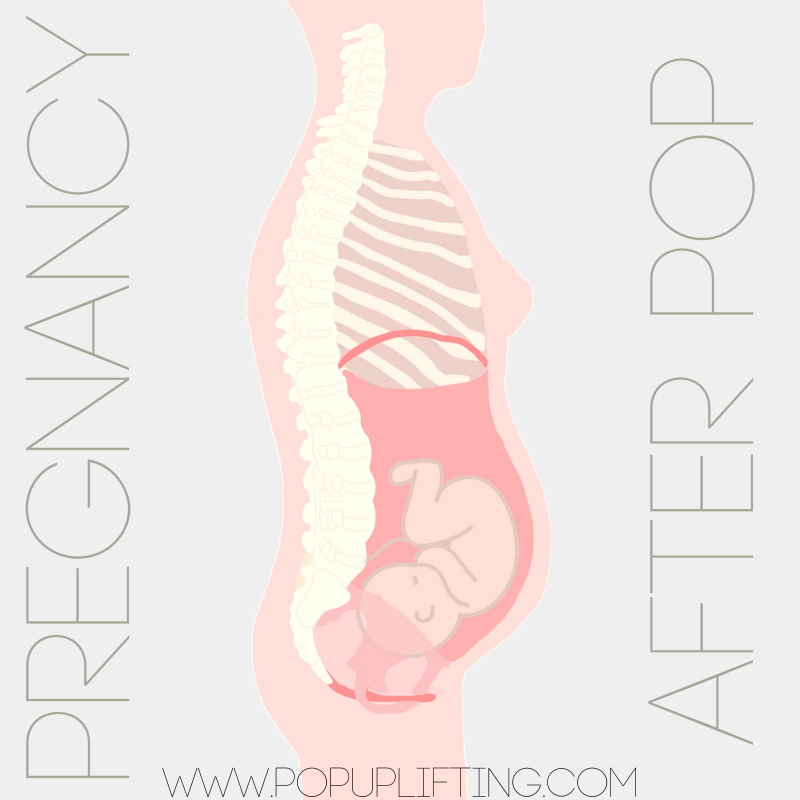

- Pregnancy.

- Overusing the pelvic muscles (like going to the bathroom too often or pushing too hard), eventually leading to poor muscle coordination.

- Pelvic surgery.

- Being overweight.

- Advancing age.

Does pregnancy cause pelvic floor dysfunction?

Pregnancy is a common cause of pelvic floor dysfunction. Often women get experience pelvic floor dysfunction after they give birth. Your pelvic floor muscles and tissues can become strained during pregnancy, especially if your labor was long or difficult.

Is pelvic floor dysfunction hereditary?

Pelvic floor dysfunction can run in your family. This is called a hereditary condition. Researchers are looking into a potential genetic cause of pelvic floor dysfunction.

What does pelvic floor dysfunction feel like?

Several symptoms may be a sign that you have pelvic floor dysfunction. If you have any of these symptoms, you should tell your healthcare provider:

If you have any of these symptoms, you should tell your healthcare provider:

- Frequently needing to use the bathroom. You may also feel like you need to ‘force it out’ to go, or you might stop and start many times.

- Constipation, or a straining pain during your bowel movements. It’s thought that up to half of people suffering long-term constipation also have pelvic floor dysfunction.

- Straining or pushing really hard to pass a bowel movement, or having to change positions on the toilet or use your hand to help eliminate stool.

- Leaking stool or urine (incontinence).

- Painful urination.

- Feeling pain in your lower back with no other cause.

- Feeling ongoing pain in your pelvic region, genitals or rectum — with or without a bowel movement.

Is pelvic floor dysfunction different for men and women?

There are different pelvic conditions that are unique to men and women.

Pelvic floor dysfunction in men:

Every year, millions of men around the world experience pelvic floor dysfunction. Because the pelvic floor muscles work as part of the waste (excretory) and reproductive systems during urination and sex, pelvic floor dysfunction can co-exist with many other conditions affecting men, including:

Because the pelvic floor muscles work as part of the waste (excretory) and reproductive systems during urination and sex, pelvic floor dysfunction can co-exist with many other conditions affecting men, including:

- Male urinary dysfunction: This condition can involve leaking urine after peeing, running to the bathroom (incontinence) and other bladder and bowel issues.

- Erectile Dysfunction (ED): ED is when men can’t get or maintain an erection during sex. Sometimes pelvic muscle tension or pain is the cause, but ED is a complex condition so this may not be the case.

- Prostatitis: Pelvic floor dysfunction symptoms closely resemble prostatitis, which is an infection or inflammation of the prostate (a male reproductive gland). Prostatitis can have many causes including bacteria, sexually transmitted infections or trauma to the nervous system.

Pelvic floor dysfunction in women:

Pelvic floor dysfunction can interfere with a woman’s reproductive health by affecting the uterus and vagina. Women who get pelvic floor dysfunction may also have other symptoms like pain during sex.

Women who get pelvic floor dysfunction may also have other symptoms like pain during sex.

Pelvic floor dysfunction is very different than pelvic organ prolapse. Pelvic organ prolapse happens when the muscles holding a woman’s pelvic organs (uterus, rectum and bladder) in place loosen and become too stretched out. Pelvic organ prolapse can cause the organs to protrude (stick out) of the vagina or rectum and may require women to push them back inside.

Interstitial cystitis is a chronic bladder condition that causes pain in your pelvis or bladder. Pain from the bladder can cause pain in the pelvic floor muscles and then loss of muscle relaxation and strength which is pelvic floor dysfunction. So, having one of these conditions increases your risk of having the other.

If you’re taking certain medications for interstitial cystitis, including antidepressants, these might cause constipation. Constipation can lead to worsening of your pelvic floor dysfunction symptoms. Check with your provider in case your prescription might be causing this problem.

Diagnosis and Tests

How is pelvic floor dysfunction diagnosed?

Your healthcare provider will usually start by asking about your symptoms and taking a careful medical history. Your provider may ask you the following questions:

- Do you have a history of urinary tract infections?

- If you’re female, have you given birth?

- If you’re female, do you have pain when you have sex?

- Do you have interstitial cystitis (a long-term inflammation of the bladder wall) or irritable bowel syndrome (a disorder of the lower intestinal tract)?

- Do you strain to pass a bowel movement?

Your provider may also do a physical exam to test how well you can control your pelvic floor muscles. Using their hands, your provider will check for spasms, knots or weakness in these muscles. Your provider may also need to give you an intrarectal (inside the rectum) exam or vaginal exam.

You may also be given other tests including:

- Surface electrodes (self-adhesive pads placed on your skin) can test your pelvic muscle control.

This might be an option if you don’t want an internal exam. The electrodes are placed on the perineum (the area between the vagina and rectum in women, and between the testicles and rectum in men) or on the sacrum (the triangular bone at the base of your spine). This test is not painful.

This might be an option if you don’t want an internal exam. The electrodes are placed on the perineum (the area between the vagina and rectum in women, and between the testicles and rectum in men) or on the sacrum (the triangular bone at the base of your spine). This test is not painful. - Anorectal manometry (a test measuring how well the anal sphincters are working) can test pressure, muscle strength and coordination. This test is not painful.

- A defecating proctogram is a test where you’re given an enema of a thick liquid that can be seen with an X-ray. Your provider will use a special video X-ray to record the movement of your muscles as you attempt to push the liquid out of the rectum. This will help to show how well you are able to pass a bowel movement or any other causes for pelvic floor dysfunction. This test is not painful.

- A uroflow test can show how well you can empty your bladder. If your flow of urine is weak or if you have to stop and start as you urinate, it can point to pelvic floor dysfunction.

Your provider may order this test if you have problems while urinating. This test is not painful.

Your provider may order this test if you have problems while urinating. This test is not painful.

Management and Treatment

How do you treat pelvic floor dysfunction?

Fortunately, pelvic floor dysfunction can be treated relatively easily in many cases. If you need physical therapy, you’re likely to feel better but it may take a few months of sessions. Pelvic floor dysfunction is treated without surgery. Non-surgical treatments include:

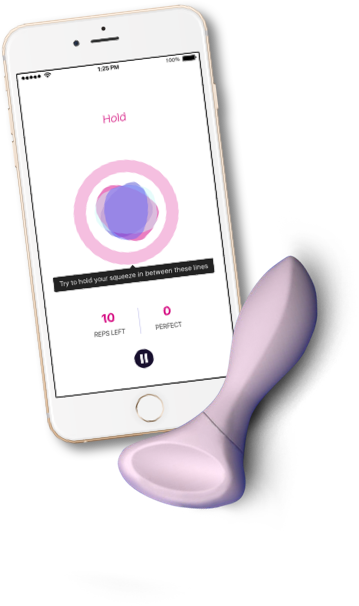

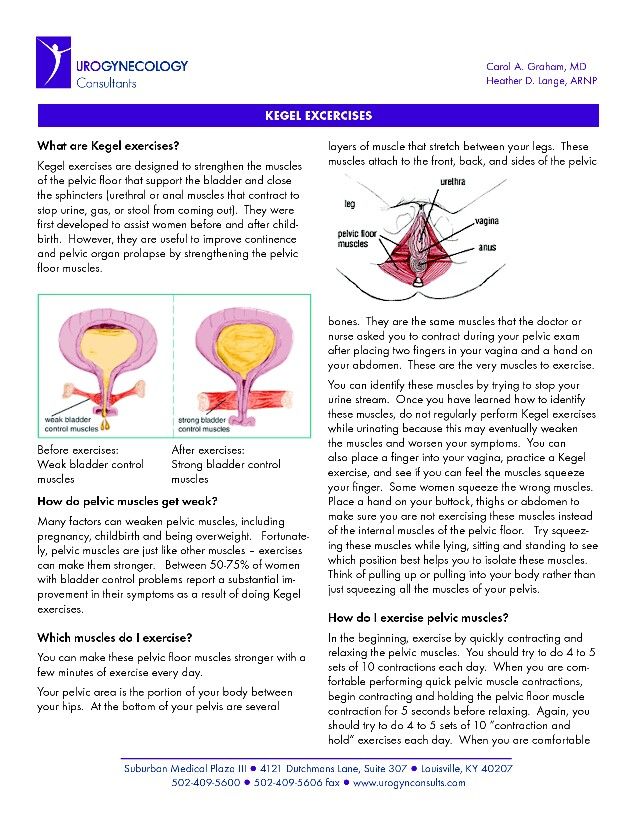

- Biofeedback: This is the most common treatment, done with the help of a physical therapist. Biofeedback is not painful, and helps over 75% of people with pelvic floor dysfunction. Your physical therapist might use biofeedback in different ways to retrain your muscles. For example, they may use special sensors and video to monitor the pelvic floor muscles as you try to relax or clench them. Your therapist then gives you feedback and works with you to improve your muscle coordination.

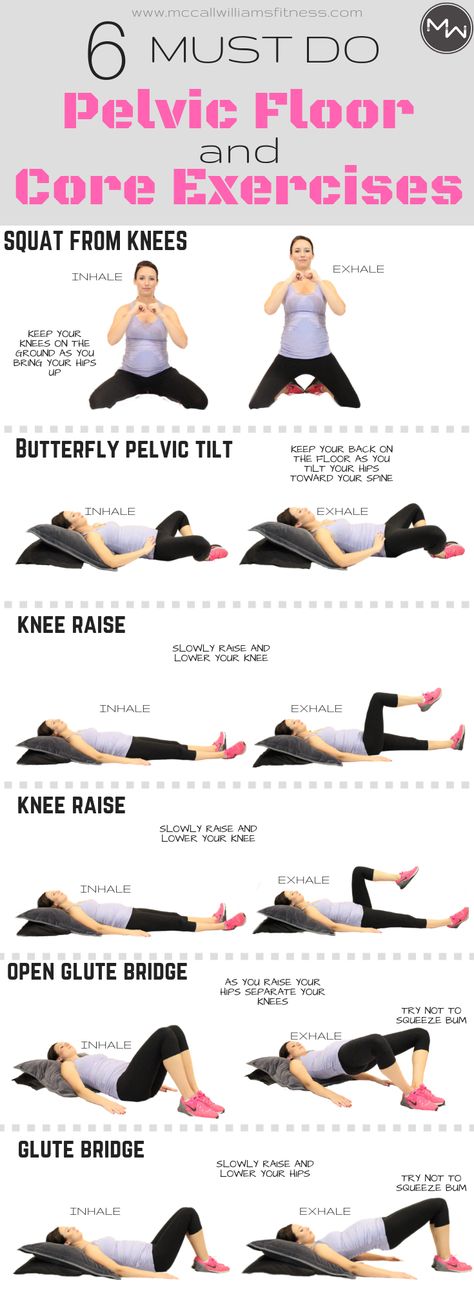

- Pelvic floor physical therapy: Physical therapy is commonly done at the same time as biofeedback therapy. The therapist will determine which muscles in your lower back, pelvis and pelvic floor are really tight and teach you exercises to stretch these muscles so their coordination can be improved.

- Medications: Daily medications that help to keep your bowel movements soft and regular are a very important part of treating pelvic floor dysfunction. Some of these medications are available over-the-counter at the drugstore and include stool softeners such as MiraLAX®, Colace®, Senna or generic stool softeners. Your primary care doctor or a gastroenterologist can help to advise you which medications are most helpful in keeping your stools soft.

- Relaxation techniques: Your provider or physical therapist might also recommend you try relaxation techniques such as meditation, warm baths, yoga and exercises, or acupuncture.

Will I need surgery to treat pelvic floor dysfunction?

There is not a surgery to treat pelvic floor dysfunction because it is a problem with your muscles. In rare circumstances, when physical therapy and biofeedback fail to work, your provider might recommend you see a pain injection specialist. These doctors specialize in localizing the specific muscles that are too tense or causing pain, and they can use a small needle to inject the muscle with numbing medication and relaxing medication. This is called trigger point injection.

What makes pelvic floor dysfunction worse?

It can take several months of routine bowel or urinary medications and pelvic floor physical therapy before symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction start to improve. The most important part of treatment is to not give up. Forgetting to take your medications every day will cause your symptoms to continue and possibly get worse. Also, skipping physical therapy appointments or not practicing exercises can slow healing.

Any activity that increases the tension or pain in your pelvic floor muscles can cause your symptoms to get worse. For example, heavy weightlifting or repetitive jumping can increase your pelvic floor tension and actually worsen symptoms.

If you have problems with constipation due to hard bowel movements or abdominal bloating and gas pain, then you should consult with your doctor and watch your diet closely. It’s important to drink plenty of water daily (>8 glasses) and eat a healthy diet. Foods that are high in fiber, or fiber supplements, may worsen your bloating symptoms and gas pains. These foods should be avoided if your symptoms get worse.

Who treats pelvic floor dysfunction?

Depending on your symptoms and how much pain you feel, you might be treated by your regular provider, a physical therapist, a gynecologist, a gastroenterologist, a pelvic pain anesthesiologist, or a pelvic floor surgeon.

Outlook / Prognosis

Does pelvic floor dysfunction go away on its own?

Pelvic floor dysfunction symptoms (like an overactive bladder) typically stay or become worse if they’re not treated. Instead of living with pain and discomfort, you can often improve your everyday life after a visit with your provider.

Instead of living with pain and discomfort, you can often improve your everyday life after a visit with your provider.

Is pelvic floor dysfunction curable?

Fortunately, most pelvic floor dysfunction is treatable, usually through biofeedback, physical therapy and medications. If you start to experience any of the symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction, contact your healthcare provider. Early treatment can help improve your quality of life and help with your inconvenient and uncomfortable symptoms.

Living With

Is pelvic floor dysfunction a disability?

Pelvic floor dysfunction isn’t currently listed as a social security disability. However, depending on your symptoms you may be able to claim disability under the ‘Disability Evaluation Under Social Security’ Section 6.00, Genitourinary (genital and urinary) Disorders. For more information, check with your provider and social security contact.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

Although pelvic floor dysfunction is a common condition, it can be embarrassing to discuss your pelvic floor dysfunction symptoms — especially your bowel movements. The good news is that many pelvic floor dysfunction symptoms are easy to treat.

The good news is that many pelvic floor dysfunction symptoms are easy to treat.

If you think you might have pelvic floor dysfunction, make sure you see your provider early, especially if you have pain when going to the bathroom. Remember, the more open and honest you are with your provider, the better your treatment will be.

Resources

Cleveland Clinic Podcasts

Visit our Butts & Guts Podcasts page to learn more about digestive conditions and treatment options from Cleveland Clinic experts.

Pelvic floor dysfunction, and effects of pregnancy and mode of delivery on pelvic floor

Review

. 2014 Dec;53(4):452-8.

doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2014.08.001.

Murat Bozkurt 1 , Ayşe Ender Yumru 2 , Levent Şahin 3

Affiliations

Affiliations

- 1 Division of Urogynecology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kafkas University Medical School, Kars, Turkey.

Electronic address: [email protected].

Electronic address: [email protected]. - 2 Division of Urogynecology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Taksim Education and Research Hospital, İstanbul, Turkey.

- 3 Kafkas University School of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kars, Turkey.

- PMID: 25510682

- DOI: 10.1016/j.tjog.2014.08.001

Free article

Review

Murat Bozkurt et al. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Dec.

Free article

. 2014 Dec;53(4):452-8.

2014 Dec;53(4):452-8.

doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2014.08.001.

Authors

Murat Bozkurt 1 , Ayşe Ender Yumru 2 , Levent Şahin 3

Affiliations

- 1 Division of Urogynecology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kafkas University Medical School, Kars, Turkey. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Division of Urogynecology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Taksim Education and Research Hospital, İstanbul, Turkey.

- 3 Kafkas University School of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kars, Turkey.

- PMID: 25510682

- DOI: 10.1016/j.tjog.2014.08.001

Abstract

Pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD), although seems to be simple, is a complex process that develops secondary to multifactorial factors. The incidence of PFD is increasing with increasing life expectancy. PFD is a term that refers to a broad range of clinical scenarios, including lower urinary tract excretory and defecation disorders, such as urinary and anal incontinence, overactive bladder, and pelvic organ prolapse, as well as sexual disorders. It is a financial burden on the health care system and disrupts women's quality of life. Strategies applied to decrease PFD are focused on the course of pregnancy, mode and management of delivery, and pelvic exercise methods. Many studies in the literature define traumatic birth, usage of forceps, length of the second stage of delivery, and sphincter damage as modifiable risk factors for PFD. Maternal age, fetal position, and fetal head circumference are nonmodifiable risk factors. Although numerous studies show that vaginal delivery affects pelvic floor structures and their functions in a negative way, there is not enough scientific evidence to recommend elective cesarean delivery in order to prevent development of PFD. PFD is a heterogeneous pathological condition, and the effects of pregnancy, vaginal delivery, cesarean delivery, and possible risk factors of PFD may be different from each other. Observational studies have identified certain obstetrical exposures as risk factors for pelvic floor disorders. These factors often coexist; therefore, the isolated effects of these variables on the pelvic floor are difficult to study. The routine use of episiotomy for many years in order to prevent PFD is not recommended anymore; episiotomy should be used in selected cases, and the mediolateral procedures should be used if needed.

Many studies in the literature define traumatic birth, usage of forceps, length of the second stage of delivery, and sphincter damage as modifiable risk factors for PFD. Maternal age, fetal position, and fetal head circumference are nonmodifiable risk factors. Although numerous studies show that vaginal delivery affects pelvic floor structures and their functions in a negative way, there is not enough scientific evidence to recommend elective cesarean delivery in order to prevent development of PFD. PFD is a heterogeneous pathological condition, and the effects of pregnancy, vaginal delivery, cesarean delivery, and possible risk factors of PFD may be different from each other. Observational studies have identified certain obstetrical exposures as risk factors for pelvic floor disorders. These factors often coexist; therefore, the isolated effects of these variables on the pelvic floor are difficult to study. The routine use of episiotomy for many years in order to prevent PFD is not recommended anymore; episiotomy should be used in selected cases, and the mediolateral procedures should be used if needed.

Keywords: anal incontinence; levator ani muscle injury; pelvic floor dysfunction; pelvic organ prolapse; urinary incontinence.

Copyright © 2014. Published by Elsevier B.V.

Similar articles

-

Association of Delivery Mode With Pelvic Floor Disorders After Childbirth.

Blomquist JL, Muñoz A, Carroll M, Handa VL. Blomquist JL, et al. JAMA. 2018 Dec 18;320(23):2438-2447. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.18315. JAMA. 2018. PMID: 30561480 Free PMC article.

-

Pelvic floor disorders after vaginal birth: effect of episiotomy, perineal laceration, and operative birth.

Handa VL, Blomquist JL, McDermott KC, Friedman S, Muñoz A. Handa VL, et al.

Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Feb;119(2 Pt 1):233-9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318240df4f. Obstet Gynecol. 2012. PMID: 22227639 Free PMC article.

Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Feb;119(2 Pt 1):233-9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318240df4f. Obstet Gynecol. 2012. PMID: 22227639 Free PMC article. -

Association of levator injury and urogynecological complaints in women after their first vaginal birth with and without mediolateral episiotomy.

Speksnijder L, Oom DMJ, Van Bavel J, Steegers EAP, Steensma AB. Speksnijder L, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan;220(1):93.e1-93.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.09.025. Epub 2018 Sep 28. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019. PMID: 30273588

-

Pelvic floor muscle strength and the incidence of pelvic floor disorders after vaginal and cesarean delivery.

Blomquist JL, Carroll M, Muñoz A, Handa VL. Blomquist JL, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):62.

e1-62.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.08.003. Epub 2019 Aug 8. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020. PMID: 31422064

e1-62.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.08.003. Epub 2019 Aug 8. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020. PMID: 31422064 -

Role of elective cesarean section in prevention of pelvic floor disorders.

Koc O, Duran B. Koc O, et al. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Oct;24(5):318-23. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3283573fcb. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012. PMID: 22814811 Review.

See all similar articles

Cited by

-

Restoration of NAD+ homeostasis protects C2C12 myoblasts and mouse levator ani muscle from mechanical stress-induced damage.

Huang G, He Y, Hong L, Zhou M, Zuo X, Zhao Z. Huang G, et al. Anim Cells Syst (Seoul). 2022 Aug 3;26(4):192-202. doi: 10.1080/19768354.2022.

2106303. eCollection 2022. Anim Cells Syst (Seoul). 2022. PMID: 36046029 Free PMC article.

2106303. eCollection 2022. Anim Cells Syst (Seoul). 2022. PMID: 36046029 Free PMC article. -

Determinants of Pelvic Floor Disorders among Women Visiting the Gynecology Outpatient Department in Wolkite University Specialized Center, Wolkite, Ethiopia.

Benti Terefe A, Gemeda Gudeta T, Teferi Mengistu G, Abebe Sori S. Benti Terefe A, et al. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2022 Aug 13;2022:6949700. doi: 10.1155/2022/6949700. eCollection 2022. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2022. PMID: 35996749 Free PMC article.

-

The effectiveness of eHealth interventions on female pelvic floor dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Xu P, Wang X, Guo P, Zhang W, Mao M, Feng S. Xu P, et al. Int Urogynecol J. 2022 May 26:1-30. doi: 10.

1007/s00192-022-05222-5. Online ahead of print. Int Urogynecol J. 2022. PMID: 35616695 Free PMC article. Review.

1007/s00192-022-05222-5. Online ahead of print. Int Urogynecol J. 2022. PMID: 35616695 Free PMC article. Review. -

Physiotherapy according to the BeBo Concept as prophylaxis and treatment of urinary incontinence in women after natural childbirth.

Śnieżek A, Czechowska D, Curyło M, Głodzik J, Szymanowski P, Rojek A, Marchewka A. Śnieżek A, et al. Sci Rep. 2021 Sep 10;11(1):18096. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-96550-x. Sci Rep. 2021. PMID: 34508116 Free PMC article.

-

Effect of Epidural Analgesia on Pelvic Floor Dysfunction at 6 Months Postpartum in Primiparous Women: A Prospective Cohort Study.

Du J, Ye J, Fei H, Li M, He J, Liu L, Liu Y, Li T. Du J, et al. Sex Med. 2021 Oct;9(5):100417. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.

2021.100417. Epub 2021 Aug 19. Sex Med. 2021. PMID: 34419692 Free PMC article.

2021.100417. Epub 2021 Aug 19. Sex Med. 2021. PMID: 34419692 Free PMC article.

See all "Cited by" articles

Publication types

MeSH terms

Pelvic floor dysfunction in pregnant women in the third trimester 2 Russian University of Peoples' Friendship, Ministry of Education and Science of Russia, Moscow

Purpose of the study. To assess the frequency and severity of symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction in pregnant women in the third trimester.

Material and methods. The study included 395 pregnant women aged 28-38 weeks who self-completed the PFDI-20 (Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory Questionnaire).

Results. 61.7% (280/395) of pregnant women listed 2 or more symptoms characteristic of prolapse, 77% (304/395) of the respondents indicated the presence of colorectal symptoms, 73.9% (292/395) of urinary symptoms. Although prolapse symptoms were statistically less common than colorectal and urinary symptoms, their severity was higher. A quarter of women experienced moderate or severe symptoms of prolapse and the same number indicated the need to reduce the protrusion for bowel and bladder emptying, indicating the possible presence of prolapse above I degree. One in four women who experienced colorectal symptoms reported that they were moderate or severe. One in six of those reporting urinary symptoms also indicated their severity, with frequent and very frequent loss of urine associated with coughing, sneezing or laughing reported by one in three of them, which indicates the greatest significance of this symptom.

Although prolapse symptoms were statistically less common than colorectal and urinary symptoms, their severity was higher. A quarter of women experienced moderate or severe symptoms of prolapse and the same number indicated the need to reduce the protrusion for bowel and bladder emptying, indicating the possible presence of prolapse above I degree. One in four women who experienced colorectal symptoms reported that they were moderate or severe. One in six of those reporting urinary symptoms also indicated their severity, with frequent and very frequent loss of urine associated with coughing, sneezing or laughing reported by one in three of them, which indicates the greatest significance of this symptom.

Conclusion. The high frequency of symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction in women during the gestation period indicates the need to actively identify such women through screening and provide them with timely medical care.

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP), urinary incontinence (UI), fecal incontinence and sexual dysfunction are collectively referred to as pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) [1]. Considering that the main cause of DTD is pregnancy and childbirth, the manifestations of DTD are noted already in this period, in most cases persist in the postpartum period and progress over time.

Considering that the main cause of DTD is pregnancy and childbirth, the manifestations of DTD are noted already in this period, in most cases persist in the postpartum period and progress over time.

Thus, UI and POP occur already during pregnancy in at least 40% of women, which are observed within 6–8 weeks of the postpartum period in most of them [2–4]. In 1 year after delivery, the frequency of UI and POP increases by 7-10%, and after 10 years - by 25% and reaches the values indicated in the literature for women examined 10 or more years after delivery (50-77%) [5, 6]. The frequency of sexual disorders correlates with the above manifestations of DTD and increases from 20% in the postpartum period to 50–80% in the long term [7–9]. On the contrary, the frequency of fecal incontinence decreases (but not in women who have suffered grade III-IV perineal tears), amounting to about 8%, also showing a certain association with UI and PTO [10-13].

These circumstances demonstrate the need for screening to identify risk factors and symptoms of DTD among women during gestation and in the postpartum period to identify women in need of treatment and rehabilitation measures, starting from the postpartum period.

The purpose of the study is to evaluate the frequency and severity of DTD symptoms in pregnant women in the third trimester.

Research materials and methods

The study included 395 pregnant women with gestation periods of 28–38 weeks (average 34.5 weeks). Patients independently completed the PFDI-20 (Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory Questionnaire). The questionnaire contained three groups of questions that dealt with symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory – POPDI6), colorectal anal symptoms (Colorectal Anal Distress Inventory – CRAD-8) and symptoms of UI (Urinary Distress Inventory–UDI 6) [1] . All symptoms were rated in points: 0 - no (never experienced), 1 - not at all (but experienced before), 2 - a few, 3 - moderately, 4 - severely.

Criteria for inclusion in the study: age 19-49 years, gestational age 28-38 weeks, informed consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria: mental illness and cognitive disorders, infectious and inflammatory diseases of the lower urinary tract and intestines in the acute phase, episiotomy or perineotomy during childbirth, deep vaginal tears during childbirth (middle and upper third of the vagina), severe somatic diseases. software package Statistica Version 10. When analyzing quantitative characteristics, the arithmetic mean, variance and 95% confidence interval (CI). The significance of the difference between the two means was assessed using a paired Student's t-test. The χ2 test was used to test statistical hypotheses about differences in proportions and ratios in two independent samples. The values were considered statistically significant at χ2>3.84, at p≤0.05.

software package Statistica Version 10. When analyzing quantitative characteristics, the arithmetic mean, variance and 95% confidence interval (CI). The significance of the difference between the two means was assessed using a paired Student's t-test. The χ2 test was used to test statistical hypotheses about differences in proportions and ratios in two independent samples. The values were considered statistically significant at χ2>3.84, at p≤0.05.

Results of the study

The age of the surveyed varied from 19 to 42 years (mean 31.6 years). There were 115 primigravidas (29...

Pelvic floor dysfunction in pregnant women in the third trimester » Obstetrics and Gynecology

DOI

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2017.11.123-128

1 Tyumen State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of Russia, Tyumen 2 Russian University of Peoples' Friendship, Ministry of Education and Science of Russia, Moscow

Purpose of the study. To assess the frequency and severity of symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction in pregnant women in the third trimester.

To assess the frequency and severity of symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction in pregnant women in the third trimester.

Material and methods. The study included 395 pregnant women aged 28-38 weeks who self-completed the PFDI-20 (Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory Questionnaire).

Results. 61.7% (280/395) of pregnant women listed 2 or more symptoms characteristic of prolapse, 77% (304/395) of the respondents indicated the presence of colorectal symptoms, 73.9% (292/395) of urinary symptoms. Although prolapse symptoms were statistically less common than colorectal and urinary symptoms, their severity was higher. A quarter of women experienced moderate or severe symptoms of prolapse and the same number indicated the need to reduce the protrusion for bowel and bladder emptying, indicating the possible presence of prolapse above I degree. One in four women who experienced colorectal symptoms reported that they were moderate or severe. One in six of those reporting urinary symptoms also indicated their severity, with frequent and very frequent loss of urine associated with coughing, sneezing or laughing reported by one in three of them, which indicates the greatest significance of this symptom.

Conclusion. The high frequency of symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction in women during the gestation period indicates the need to actively identify such women through screening and provide them with timely medical care.

pelvic floor dysfunction

urinary incontinence

pelvic organ prolapse

fecal incontinence

pregnancy

third trimester

0002 1. Memon H.U., Handa V.L. Vaginal childbirth and pelvic floor disorders. women's health. 2013; 9(3): 265-77.

2. Sangsawang B., Sangsawang N. Stress urinary incontinence in pregnant women: a review of prevalence, pathophysiology, and treatment. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2013; 24(6): 901-12. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

3. Mørkved S., Bø K. Prevalence of urinary incontinence during pregnancy and postpartum. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1999; 10(6): 394-8.

4. Lewicky-Gaupp C., Cao D.C., Culbertson S. Urinary and anal incontinence in African American teenaged gravidas during pregnancy and the puerperium. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2008; 21(1): 21-6.

J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2008; 21(1): 21-6.

5. Altman D., Ekström A., Gustafsson C., López A., Falconer C., Zetterström J. Risk of urinary incontinence after childbirth: a 10-year prospective cohort study. obstet. Gynecol. 2006; 108(4): 873-8.

6. Dolan L.M., Hilton P. Obstetric risk factors and pelvic floor dysfunction 20 years after first delivery. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2010; 21(5): 535-44.

7. Xu X.Y., Wang H.Y., Su L. et al. Women's sexual health after delivery and its related influential factors. J.Clin. rehab. tissue engineer. Res. 2007; 11:1673-8225.

8. Dixon M., Booth N., Powell R. Sex and relationships following childbirth: a first report from general practice of 131 couples. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2000; 50(452): 223-4.

9. Kline C.R., Martin D.P., Deyo R.A. Health consequences of pregnancy and childbirth as perceived by women and clinicians. obstet. Gynecol. 1998; 92(5): 842-8.

10. Chiarelli P., Murphy B., Cockburn J. Fecal incontinence after high-risk delivery. obstet. Gynecol. 2003; 102(6): 1299-305.

obstet. Gynecol. 2003; 102(6): 1299-305.

11. Brown S.J., Gartland D., Donath S., MacArthur C. Fecal incontinence during the first 12 months postpartum: complex causal pathways and implications for clinical practice. obstet. Gynecol. 2012; 119(2, Pt 1): 240-9.

12. Eason E., Labrecque M., Marcoux S., Mondor M. Anal incontinence after childbirth. CMAJ. 2002; 166(3): 326-30.

13. Macarthur C., Wilson D., Herbison P., Lancashire R. J., Hagen S., Toozs-Hobson P. et al. Faecal incontinence persisting after childbirth: a 12 year longitudinal study. BJOG. 2013; 120(2): 169-78.

14. Chen Y., Li F.Y., Lin X., Chen J., Chen C., Guess M.K. The recovery of pelvic organ support during the first year postpartum. BJOG. 2013; 120(11): 1430-7.

15. Liang C.C., Chang S.D., Lin S.J., Lin Y.J. Lower urinary tract symptoms in primiparous women before and during pregnancy. Arch. Gynecol. obstet. 2012; 285(5): 1205-10.

16. Ammari A., Tsikouras P., Dimitraki M. , Liberis A., Kontomanolis E., Galazios G., Liberis V. Uterine prolapse complicating pregnancy: A case report. HJOG. 2014; 13(2): 74-7.

, Liberis A., Kontomanolis E., Galazios G., Liberis V. Uterine prolapse complicating pregnancy: A case report. HJOG. 2014; 13(2): 74-7.

17. Parés D., Martinez-Franco E., Lorente N., Viguer J., Lopez-Negre J.L., Mendez Z.R. Prevalence of fecal incontinence in women during pregnancy: a large cross-sectional study. Dis. Colon rectum. 2015; 58(11): 1098-103.

18. Pearl G., Herbert J.H. Assessing pelvic floor during childbearing year. Nurs. times. 2008; 104(18): 40-4.

19. Khajehei M. Sexuality after childbirth: Gaps and needs. World J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012; 1(2): 14-6.

Received September 15, 2017

Accepted for publication September 22, 2017

Anton Alexandrovich Sukhanov, Head. Department of Family Planning and Reproduction, Perinatal Center, Postgraduate Student of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Resuscitation with a Course of Clinical Laboratory Diagnostics of the Institute of Research and Development, SBEE HPE Tyumen State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of Russia. Address: 625002, Russia, Tyumen, st. Daudelnaya, d. 1. Phone: 8 (3452) 50-82-77. E-mail: [email protected]

Address: 625002, Russia, Tyumen, st. Daudelnaya, d. 1. Phone: 8 (3452) 50-82-77. E-mail: [email protected]

Galina Borisovna Dikke, Honored Worker of Science and Education, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Medicine of the Faculty of Advanced Training of Medical Workers of the FSAEI HE RUDN University.

Address: 117198, Russia, Moscow, st. Miklukho-Maklaya, d. 6. Phone: 8 (495) 434-53-00. E-mail: [email protected]

Irina Ivanovna Kukarskaya, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Chief Specialist in Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Department of Health of the Tyumen Region, Professor of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Resuscitation with a course of clinical laboratory diagnostics of the Institute of Scientific and Practical Diagnostics of the State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education Tyumen State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Chief Physician of the Perinatal center.