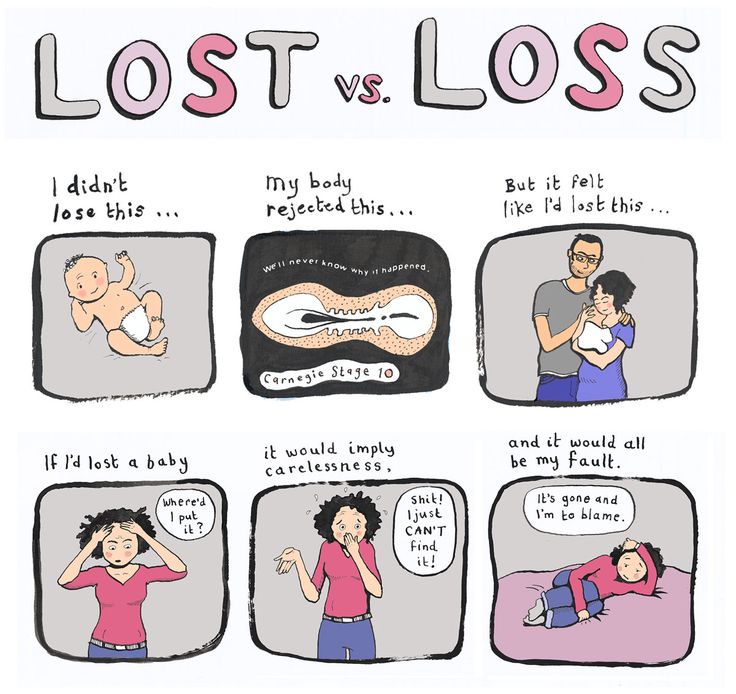

How can i lose a baby

Why we need to talk about losing a baby

Why we need to talk about losing a baby- All topics »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

- Resources »

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Multimedia

- Publications

- Questions & answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Popular »

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Monkeypox

- All countries »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

- Regions »

- Africa

- Americas

- South-East Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- WHO in countries »

- Statistics

- Cooperation strategies

- Ukraine emergency

- All news »

- News releases

- Statements

- Campaigns

- Commentaries

- Events

- Feature stories

- Speeches

- Spotlights

- Newsletters

- Photo library

- Media distribution list

- Headlines »

- Focus on »

- Afghanistan crisis

- COVID-19 pandemic

- Northern Ethiopia crisis

- Syria crisis

- Ukraine emergency

- Monkeypox outbreak

- Greater Horn of Africa crisis

- Latest »

- Disease Outbreak News

- Travel advice

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- WHO in emergencies »

- Surveillance

- Research

- Funding

- Partners

- Operations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Data at WHO »

- Global Health Estimates

- Health SDGs

- Mortality Database

- Data collections

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Dashboard

- Triple Billion Dashboard

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Highlights »

- Global Health Observatory

- SCORE

- Insights and visualizations

- Data collection tools

- Reports »

- World Health Statistics 2022

- COVID excess deaths

- DDI IN FOCUS: 2022

- About WHO »

- People

- Teams

- Structure

- Partnerships and collaboration

- Collaborating centres

- Networks, committees and advisory groups

- Transformation

- Our Work »

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Activities

- Initiatives

- Funding »

- Investment case

- WHO Foundation

- Accountability »

- Audit

- Budget

- Financial statements

- Programme Budget Portal

- Results Report

- Governance »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Election of Director-General

- Governing Bodies website

- Home/

- Newsroom/

- Spotlight/

- Why we need to talk about losing a baby

Why we need to talk about losing a baby

WHO/M. Purdie

© Credits

Losing a baby in pregnancy through miscarriage or stillbirth is still a taboo subject worldwide, linked to stigma and shame. Many women still do not receive appropriate and respectful care when their baby dies during pregnancy or childbirth. Here, we share your stories from around the globe.

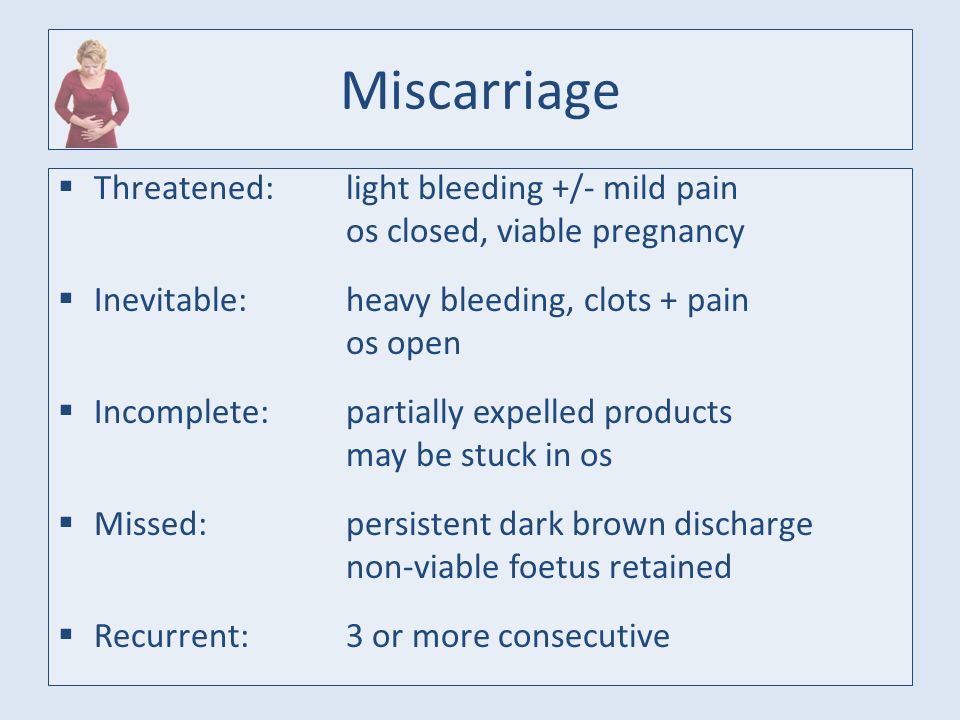

Miscarriage is the most common reason for losing a baby during pregnancy. Estimates vary, although March of Dimes, an organization that works on maternal and child health, indicates a miscarriage rate of 10-15% in women who knew they were pregnant. Pregnancy loss is defined differently around the world, but in general a baby who dies before 28 weeks of pregnancy is referred to as a miscarriage, and babies who die at or after 28 weeks are stillbirths. Every year, nearly 2 million babies are stillborn, and many of these deaths are preventable. However, miscarriages and stillbirths are not systematically recorded, even in developed countries, suggesting that the numbers could be even higher.

Around the world, women have varied access to healthcare services, and hospitals and clinics in many countries are very often under-resourced and understaffed. As varied as the experience of losing a baby may be, around the world, stigma, shame and guilt emerge as common themes. As these first-person accounts show, women who lose their babies are made to feel that should stay silent about their grief, either because miscarriage and stillbirth are still so common, or because they are perceived to be unavoidable.

Jessica Zucker, clinical psychologist and writer, USA

"As a clinical psychologist, I specialise in women's reproductive and maternal mental health and have done so for over a decade. It wasn't until I experienced this 16-week miscarriage first-hand that I could truly grasp the anguish and the circuitousness of grief I had heard my patients speak of for so many years. After my miscarriage, I poured over the research which shows that a majority of women report experiencing feelings of shame, self-blame and guilt following pregnancy loss. "

"

Jessica's story

All of this takes an enormous toll on women. Many women who lose a baby in pregnancy can go on to develop mental health issues that last for months or years– even when they have gone on to have healthy babies.

Cultural and societal attitudes to losing a baby can vary tremendously around the globe. In sub-Saharan Africa, a common belief is that a baby might be stillborn because of witchcraft or evil spirits.

Larai, 44, pharmacist, Nigeria

“Coping with my miscarriage was traumatic. The medical staff contributed a lot to my grief despite the fact that I am a doctor too. The other issue is the cultural attitude. In most traditional African cultures, people think you can lose a baby because of a curse or witchcraft. Here, child loss is surrounded by stigma because some people believe there is something wrong with a woman who has had recurrent losses, that she may have been promiscuous, and so the loss is seen as a punishment from God. "

"

Larai’s story

People, especially those with high profiles, are taking to social media to share their experiences, like in the case of Kimberly Van Der Beek and her husband, actor James Van Der Beek, best known for his role in American television series Dawson’s Creek. The couple recently shared a heartfelt post on Instagram where they opened up about the painful process of suffering multiple miscarriages — and then learning how to move past it.

Kimberly Van Der Beek, USA

"I’ve had three miscarriages, all around 10 weeks gestation. I let them all happen naturally. I had a loving husband, a compassionate birthing team and I felt spiritually grounded about them. And even in the best of circumstances, I was devastated every single time. After one of them I sat in the shower crying for almost five hours. What I find disheartening is that not all women, or fathers for that matter, are treated with the same compassion or have support during this gut wrenching time".

Kimberly's story

There are many reasons why a miscarriage may happen, including fetal abnormalities, the age of the mother, and infections, many of which are preventable such as malaria and syphilis, though pinpointing the exact reason is often challenging.

General advice on preventing miscarriage focuses on eating healthily, exercising, avoiding smoking, drugs and alcohol, limiting caffeine, controlling stress, and being of a healthy weight. This places the emphasis on lifestyle factors, which, in the absence of specific answers, can lead to women feeling guilty that they have caused their miscarriage.

Lisa, 40, marketing manager, UK

“I’ve had four miscarriages. Each time it happens, a piece of you dies. The most traumatic was the first one. We were so excited about our new baby. But when we went in for the 12-week scan, I was told I had a missed miscarriage, also called a silent miscarriage, which meant the baby died a long time ago but my body hadn't showed any signs. I was devastated. I also couldn’t believe that they were going to just send me home with my dead baby inside me, and no advice about what to do."

I was devastated. I also couldn’t believe that they were going to just send me home with my dead baby inside me, and no advice about what to do."

Lisa’s story

As with other health issues such as mental health, around which there is tremendous taboo still, many women report that no matter their culture, education or upbringing, their friends and family do not want to talk about their loss. This seems to connect with the silence that shrouds talking about grief in general.

Susan, 34, writer, USA

“I’ve been on the fertility train for nearly 5 years. As my own IVF began, I quickly learned that I had no idea what I was in for; it was so physically and emotionally exhausting. Thankfully, I did get pregnant, and my husband and I were so excited. However, after 7 weeks, the baby stopped growing. I then quit IVF hormones, and after 2 more weeks, the miscarriage began. It lasted 19 days. I didn’t realize miscarriages were a long process of pain and heavy bleeding. That the realities of fertility and miscarriage are so shrouded behind shame and silence. "

"

Susan's story

Stillbirths happen later in pregnancy, and more than 40% occur during labour, many of which are preventable. Around 84% of stillbirths take place in low- and lower middle-income countries. Providing better quality of care during pregnancy and childbirth could prevent over half a million stillbirths worldwide. Even in high-income countries, substandard care is a significant factor in stillbirths.

There are clear ways in which to reduce the number of babies who die in pregnancy – improving access to antenatal care (in some areas in the world, women do not see a health care worker until they are several months pregnant), introducing continuity of care through midwife-led care, and introducing community care where possible.

Integrating the treatment of infections in pregnancy, fetal heart rate monitoring and labour surveillance, as part of an integrated care package could save 832 000 who would otherwise have been stillborn.

How women are treated during pregnancy is linked to their sexual and reproductive rights, over which many women around the world do not have autonomy.

Societal pressures in many parts of the world can mean that women get pregnant when they are not physically or mentally ready. Even in 2019, 200 million women who want to avoid pregnancy have no access to modern contraception. And when they do get pregnant, 30 million women do not give birth in a health facility and 45 million women receive inadequate or no antenatal care, putting both mother and baby at much greater risk of complications and death.

Emilia, 36, retailer, Colombia

"When I had a stillbirth at 32 weeks, my baby already had a name. I rushed to the clinic with very high blood pressure. After a checkup, the doctor told me to take some rest and prescribed a medication to lower my blood pressure. After a week I still had the same symptoms. The doctor rushed me to take an ultrasound and he told me that the baby had no vital signs. If I had been given more information from the very beginning, and received more medical attention at critical moments, my baby could have been saved. "

"

Emilia’s story

How women are treated during pregnancy is linked to their sexual and reproductive rights, over which many women around the world do not have autonomy.

Societal pressures in many parts of the world can mean that women get pregnant when they are not physically or mentally ready. Even in 2019, 200 million women who want to avoid pregnancy have no access to modern contraception. And when they do get pregnant, 30 million women do not give birth in a health facility and 45 million women receive inadequate or no antenatal care, putting both mother and baby at much greater risk of complications and death.

Divya Samson Panabakam, 30, consultant, India

"In 2013 I had my first miscarriage. As soon as I started bleeding I went to the hospital and I was sent to get a sonogram, but the person in charge thought that I wasn’t married and made me wait. I asked her: “Even if I wasn’t married, why would you want to treat someone who is losing a baby this way?”. She just looked at me and replied: 'It’s not an emergency, only a woman over 60 would be treated as an emergency case'."

She just looked at me and replied: 'It’s not an emergency, only a woman over 60 would be treated as an emergency case'."

Read More

Cultural practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM) and child marriage are hugely damaging to girls’ sexual and reproductive health, and the health of their babies. Having babies too young can be dangerous for both the mothers and the babies. Adolescent mothers (aged 10 – 19 years) are far more likely to have eclampsia or uterine infections than women aged 20-24 years, which can increase the risk of stillbirth. Babies born to women younger than 20 years are also more likely to be of low birthweight, preterm, or have severe neonatal conditions, all of which can increase the risk of stillbirth.

FGM increases a woman’s risk of prolonged and obstructed labour, haemorrhage, severe tearing and a need for instrumental delivery. Her baby is much more likely to need resuscitation at delivery and faces a high risk of death during labour or after birth.

Putting women at the centre of their care is vital to a positive pregnancy experience – biomedical and physiological aspects of care need to be joined with social, cultural, emotional and psychological support.

Yet many women, even in developed countries with access to the best healthcare, receive inadequate care after losing a baby. The language used around miscarriage and stillbirth can be traumatic in itself – terminology referring to an “incompetent cervix” or a “blighted ovum” can be distressing.

Andrea, 28, stylist, Colombia

"When I was 12 weeks pregnant, I went for a check-up and had an ultrasound. The doctor told me that something was wrong without specifying what it was. The next day I woke up and noticed that the bed sheet were stained with blood. I did not receive any information on why I had a miscarriage. The nurses were very cold and unfriendly and they behaved as if it was just a medical procedure. Among all the staff at the hospital the only one who had a bit of humanity was the doctor, who later reassured me that I could try again to get pregnant. "

"

Andrea's story

Depending on the policy of the hospital, the babies’ bodies may be treated as clinical waste and incinerated. Sometimes when a woman finds out her baby has died, she is required to carry the dead baby for several weeks before she can give birth. Though there may be clinical reasons for this delay, this is distressing to the woman and her partner. Even in developed countries, women may birth their dead baby in maternity units, surrounded by women with healthy babies.

Not all hospitals or clinics can adopt new policies or provide more services. This is a reality of overburdened health care systems. Yet encouraging more sensitivity in dealing with bereaved couples, and removing the taboo and stigma around talking about baby loss does not need to cost money. This is reflected in some of the stories featured here.

Becky, 38, primary school teacher, Viet Nam/UK

"My husband and I were over the moon when I fell pregnant with twin girls and were devastated to lose one of them – we called her Isla - at 34 weeks. I was terrified that we were going to lose our other baby too, and insisted on staying in hospital. The next day I delivered our girls via caesarean section. Overall the hospital was incredibly supportive and we were given a private room and time to spend with Isla. However a number of doctors showed complete insensitivity with one even asking why I was crying and telling me to cheer up".

I was terrified that we were going to lose our other baby too, and insisted on staying in hospital. The next day I delivered our girls via caesarean section. Overall the hospital was incredibly supportive and we were given a private room and time to spend with Isla. However a number of doctors showed complete insensitivity with one even asking why I was crying and telling me to cheer up".

Becky's story

Healthcare staff can show sensitivity and empathy, acknowledge how the parents feel, provide clear information, and understand that the parents may need specific support both in dealing with their loss and in potentially trying to have another baby. Providing human rights based care, that is socioculturally relevant, respectful and dignified is as much a requirement for competent maternal and newborn care as clinical competence.

Sarah, 40, civil servant, Australia

"Stillbirth is so common in Australia when it happens to you or someone you know. It’s suddenly everywhere. Stillbirth affects around 2000 Australian families each year. Our rate of stillbirth hasn’t changed in 20 years and for Indigenous Australians it’s twice as high. Yet before it happened to me and I became that one in six, I never considered that babies could die in utero. It’s never spoken about. The doctor told me about my increased risk of cord prolapse with polyhydramnios but no one mentioned I was at an increased risk of fetal death".

It’s suddenly everywhere. Stillbirth affects around 2000 Australian families each year. Our rate of stillbirth hasn’t changed in 20 years and for Indigenous Australians it’s twice as high. Yet before it happened to me and I became that one in six, I never considered that babies could die in utero. It’s never spoken about. The doctor told me about my increased risk of cord prolapse with polyhydramnios but no one mentioned I was at an increased risk of fetal death".

Sarah's story

Key messages around support

The Unacceptable Stigma And Shame Women Face After Baby Loss Must End

Op-ed by Dr Princess Nothemba Simelela, Assistant director-general for family, women, children and adolescents, WHO

Find out more

More on WHO's work

More on WHO's work with partners

All illustrations WHO/M. Purdie

Join WHO in action

Miscarriages (for Parents) - Nemours KidsHealth

What Is a Miscarriage?

A miscarriage is the loss of a pregnancy (the loss of an embryo or fetus before it's developed enough to survive). This sometimes happens even before a woman knows she is pregnant. Unfortunately, miscarriages are fairly common.

This sometimes happens even before a woman knows she is pregnant. Unfortunately, miscarriages are fairly common.

A miscarriage usually happens in the first 3 months of pregnancy, before 12 weeks' gestation. A very small number of pregnancy losses are called stillbirths, and happen after 20 weeks’ gestation.

What Happens During a Miscarriage?

Often, a woman can have an extra heavy menstrual flow and not realize it’s a miscarriage because she hadn’t known she was pregnant.

Some women who miscarry have cramping, spotting, heavier bleeding, abdominal pain, pelvic pain, weakness, or back pain. Spotting does not always mean a miscarriage. Many pregnant women have spotting early in the pregnancy and go on to have a healthy baby. But just to be safe, if you have spotting or any of these other symptoms anytime during your pregnancy, talk with your doctor.

What Is Stillbirth?

Many experts define a stillbirth as the death of a baby after the 20th week of pregnancy. It can happen before delivery or during labor or delivery. A stillbirth also is sometimes referred to as intrauterine fetal death or antenatal death.

It can happen before delivery or during labor or delivery. A stillbirth also is sometimes referred to as intrauterine fetal death or antenatal death.

There are some known risk factors for stillbirth, such as smoking, obesity, problems with the placenta, a pregnancy lasting longer than 42 weeks, and some infections. But the cause of many stillbirths isn’t found.

The most common sign of a stillbirth is decreased movement in the baby. If you notice your baby moving less than usual, call your doctor right away. Your doctor can use an ultrasound to look for the heartbeat or, later in pregnancy, give you a fetal non-stress test. This involves lying on your back with electronic monitors on your abdomen. The monitors record the baby's heart rate and movements, and contractions of the uterus.

Why Do Miscarriages Happen?

The most common cause of pregnancy loss is a problem with the chromosomes that would make it impossible for the fetus to develop normally.

Other things that could play a role include:

- low or high hormone levels in the mother, such as thyroid hormone

- uncontrolled diabetes in the mother

- exposure to environmental and workplace hazards, such as radiation or toxic agents

- some infections

- uterine abnormalities

- incompetent cervix, which is when the cervix begins to open (dilate) and thin (efface) before the pregnancy has reached term

- the mother taking some medicines, such as the acne drug Accutane

A miscarriage also can be more likely in pregnant women who:

- smoke, because nicotine and other chemicals in the mother’s bloodstream cause the fetus to get less oxygen

- drink alcohol and or use illegal drugs

What Happens After a Miscarriage?

If a woman miscarries, her doctor will do a pelvic exam and an ultrasound to confirm the miscarriage. If the uterus is clear of any fetal tissue, or it is very early in the pregnancy, many won’t need further treatment.

If the uterus is clear of any fetal tissue, or it is very early in the pregnancy, many won’t need further treatment.

Sometimes, the uterus still contains the fetus or other tissues from the pregnancy. A doctor will need to remove this. The doctor may give medicine to help pass the tissue or may dilate the cervix to do:

- a dilation and curettage (D&C), a scraping of the uterine lining

- a dilation and extraction (D&E), a suction of the uterus to remove fetal or placental tissue

A woman may have bleeding or cramping after these procedures.

If a baby dies later in a woman’s pregnancy, the doctor might induce labor and delivery. After the delivery, the doctor will have the baby and the placenta examined to help find the cause of death if it's still unknown.

Women who have had several miscarriages may want to get checked to see if any anatomic, genetic, or hormonal problems are making miscarriages more likely.

Can Miscarriages Be Prevented?

In most cases, a miscarriage cannot be prevented because it’s caused by a chromosomal abnormality or problem with the development of the fetus. Still, some things — such as smoking and drinking — put a woman at a higher risk for losing a pregnancy.

Still, some things — such as smoking and drinking — put a woman at a higher risk for losing a pregnancy.

Good prenatal care can help moms and their babies stay healthy throughout the pregnancy. If you’re pregnant:

- Eat a healthy diet with plenty of folic acid and calcium.

- Take prenatal vitamins daily.

- Exercise regularly after you've gotten your doctor's OK.

- Keep a healthy weight. Pregnant women who are overweight or too thin may be more likely to have miscarriages.

- Avoid drugs and alcohol.

- Avoid deli meats and unpasteurized soft cheeses such as feta and other foods that could carry listeriosis.

- Limit caffeine intake.

- If you smoke, quit.

- Talk to your doctor about all medicines you take. Unless your doctor tells you otherwise, many prescription and over-the-counter medicines should be avoided during pregnancy.

- Avoid activities that could cause you to get hit in the belly.

- Make sure you’re up to date on all recommended vaccines.

- Know your family medical and genetic history.

- Go to all of your scheduled prenatal visits and discuss any concerns with your doctor.

- Call your doctor right away if you have fever; feel ill; notice the baby moving less; or have bleeding, spotting, or cramping.

Trying Again After a Miscarriage

If you've had a miscarriage, take time to grieve. The loss of a baby during pregnancy is like the loss of any loved one. Give yourself time to heal emotionally and physically. Some health care providers recommend that women wait one menstrual cycle or more before trying to get pregnant again.

Some other things that can help you get through this difficult time:

- Find a support group. Ask your doctor about local support groups for women who are trying again after a loss.

- Find success stories. Other women who have had a successful pregnancy after having a miscarriage can be a great source of encouragement.

Your doctor might know someone to talk with.

Your doctor might know someone to talk with.

During future pregnancies, it can help to:

- Be proactive. The more you know about the medical aspects of your pregnancy, the better you'll be able to discuss treatment options and outcomes with your doctor.

- Monitor the baby's movements. If you're far enough along to feel kicks and jabs — usually between 18 and 22 weeks — keep a log of the baby's activities each morning and night and report any changes or lack of movement to your doctor. If your baby isn't moving, eat or drink something sugary and lie down on your side. You should feel at least 10 movements in a 2-hour period. If you don't, call your doctor right away.

- Try not to compare. No two pregnancies are exactly alike, so try not to dwell on any similarities between this pregnancy and the one that ended in a loss.

- Stay positive. Envision a good end to help you stay positive.

Reviewed by: Larissa Hirsch, MD

Date reviewed: October 2020

Why is it so important for us to talk about the loss of a child

Why is it so important for us to talk about the loss of a child?- Popular Topics

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Data and statistics »

- News bulletin

- The facts are clear

- Publications

- Find country »

- A

- B

- B

- g

- D

- E

- F

- °

- and

- l

- N 9000

- R

- C

- T

- in

- x

- C 9000

- WHO in countries »

- Reporting

- Regions »

- Africa

- America

- Southeast Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- Media Center

- Press releases

- Statements

- Media messages

- Comments

- Reporting

- Online Q&A

- Developments

- Photo reports

- Questions and answers

- Update

- Emergencies "

- News "

- Disease Outbreak News

- WHO Data »

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Monitoring Dashboard

- Basic moments "

- About WHO »

- CEO

- About WHO

- WHO activities

- Where does WHO work?

- Governing Bodies »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive committee

- Main page/

- Media Center /

- Spotlight/

- Why is it so important for us to talk about the loss of a child

Why is it important for us to talk about the loss of a child

WHO/M. Purdie

Purdie

© A photo

The loss of a child during pregnancy due to miscarriage or stillbirth is still a taboo subject around the world, with condemnation or shame associated with it. Many women who lose a child during pregnancy or childbirth continue to receive neither the proper care nor the respect they deserve. In this material we want to share stories told by women from different countries.

Miscarriage is the most common cause of pregnancy loss. Estimates of the prevalence of this phenomenon vary somewhat, although according to the March of Dimes Foundation, an organization dedicated to maternal and child health, the prevalence of miscarriage in women who knew they were pregnant is 10-15%. Different countries around the world use different definitions of pregnancy loss, but as a rule, the death of a child before 28 weeks of gestation is considered a miscarriage, and death at or after 28 completed gestational weeks is considered a stillbirth. There are 2.6 million stillborn babies born each year, and many of these deaths could have been prevented. However, even in developed countries, miscarriages and stillbirths are not systematically recorded, so the actual figures may be even higher.

There are 2.6 million stillborn babies born each year, and many of these deaths could have been prevented. However, even in developed countries, miscarriages and stillbirths are not systematically recorded, so the actual figures may be even higher.

Worldwide, women's access to health care varies by country of residence, with hospitals and outpatient facilities very often under-resourced and understaffed in many countries. As varied as the experience of bereaved women, stigma, guilt and shame are common themes around the world. Women who have lost their children have shared personal experiences that they felt they had to keep their grief quiet, either because miscarriages or stillbirths remain common or because people perceive them as inevitable.

Jessica Zucker, Clinical Psychologist and Writer, USA

“I am a clinical psychologist specializing in mental health issues related to reproduction and motherhood. I have been doing this for over ten years. But when I myself had a miscarriage at 16 weeks, only then could I truly feel that heartache, that re-experienced feeling of grief and loss that my patients have been telling me about for so many years.

Jessica's story

All this has an extremely hard effect on women. Many women who lose a child during pregnancy may develop mental health problems that last for months or years, even if they later have healthy children.

Cultural and social views on the loss of a child in different parts of the world can be very different from each other. Thus, in sub-Saharan Africa, the prevailing opinion is that a baby can be born dead because of witchcraft or the machinations of evil spirits.

Larai, 44, pharmacist, Nigeria

“I took everything that happened after my miscarriage very hard. This was greatly facilitated by the medical workers themselves, despite the fact that I am also a doctor. Another issue is cultural representations. Here, the loss of a child brings shame to the woman, because there is a perception that if a woman has lost a child several times, something is wrong with her, and that she may have had extramarital affairs, and the loss of a child in that case, God's punishment.

Larai's story

There are many possible causes for miscarriages or stillbirths, including fetal abnormalities, maternal age, and infections, many of which (such as malaria and syphilis) are preventable, although identifying the exact cause is often difficult.

General recommendations for preventing miscarriage include a healthy diet, physical activity, avoiding smoking, drug and alcohol use, limiting caffeine intake, managing stress, and maintaining a normal body weight. This approach focuses on lifestyle factors, and in the absence of specific explanations for what happened, this can lead to women feeling guilty that it was their behavior that caused the miscarriage.

Lisa, 40, Marketing Manager, UK

“I've had four miscarriages. Every time this happens, a part of you dies. The first time was the hardest. It was my very first pregnancy. We were so happy that we will soon have a baby. But when we went to our local hospital in the southeast of England at week 12 for a routine ultrasound, I was told that I had a miscarriage, or miscarriage, which meant that my baby had died long ago, although I did not feel no signs. "

"

Lisa's story

As with some other medical topics, such as mental health, which remain a huge taboo, many women report that, regardless of their cultural background, education and upbringing, their friends and families don't want to talk about their loss. Apparently, this is due to the general tradition to surround any grief with a veil of silence.

Susan, 34, writer, USA

“I've been dealing with infertility for almost five years now. After I decided to try IVF, I actually managed to get pregnant, but after a few weeks the baby stopped growing. It took doctors two and a half weeks to confirm this. It took another two weeks before I had a miscarriage that lasted 19days. I could not imagine that it could be so painful, for so long and with such heavy bleeding.

Susan's story

Stillbirths occur later in pregnancy, namely after 28 gestational weeks, as defined by WHO. About 98% of stillbirths occur in low- and middle-income countries. Lack of proper care and supervision during labor results in one in two stillbirths occurring during delivery, many of which could have been prevented with quality care and proper supervision of the woman in labour.

Lack of proper care and supervision during labor results in one in two stillbirths occurring during delivery, many of which could have been prevented with quality care and proper supervision of the woman in labour.

Better care during pregnancy and childbirth could prevent more than half a million stillbirths globally. Even in high-income countries, non-compliance with standards of care is an important cause of stillbirths.

There are clear ways to reduce the number of children who die during pregnancy, namely: improving access to antenatal care (in some parts of the world, women do not see a health worker until they are several months pregnant), introducing continuous care models, provided by midwives, as well as community care where possible. Integrating infection management during pregnancy, fetal heart rate monitoring and birth monitoring into a comprehensive care package could save 1.3 million lives of otherwise stillborn babies.

Emilia, 36, shopkeeper, Colombia

“When my baby was stillborn at 32 weeks, we already gave him a name. The doctor referred me for an ultrasound examination, during which he told me that the child was not showing signs of life. I knew right away that my baby was dead. I know this could have been avoided. If from the very beginning I had been told everything about my condition in more detail, if the doctors had treated me more attentively during the critical periods of my pregnancy, my child could have been saved.

The doctor referred me for an ultrasound examination, during which he told me that the child was not showing signs of life. I knew right away that my baby was dead. I know this could have been avoided. If from the very beginning I had been told everything about my condition in more detail, if the doctors had treated me more attentively during the critical periods of my pregnancy, my child could have been saved.

Emilia's story

Attitude towards women during pregnancy is related to the extent to which their sexual and reproductive rights are generally realized; many women around the world do not have the ability to make autonomous decisions in this area.

In many parts of the world, the pressure of public opinion is forcing women to become pregnant when they are not yet physically or psychologically ready for it. Even in 2019, 200 million women who want to avoid pregnancy do not have access to modern methods of contraception. And when pregnancy does occur, 30 million women are forced to give birth outside of health facilities, and 45 million women do not receive adequate antenatal care or no antenatal care at all, greatly increasing the risk of complications and death for both the mother and the mother. child.

child.

Cultural practices, such as ritual female genital mutilation and child marriage, cause great harm to girls' sexual and reproductive health and the health of their children. Having children at a young age can be dangerous for both mother and child. Adolescent girls (aged 10–19 years) are significantly more likely to have eclampsia or intrauterine infections than women aged 20–24 years, increasing the risk of stillbirth in this age group. In addition, babies born to women younger than 20 are more likely to have low birth weight, prematurity, or severe health problems in the first month of life, which also increases the risk of stillbirth.

Female genital mutilation increases a woman's risk of protracted or difficult labour, bleeding, severe tears and increases the frequency of instrumental use in childbirth. At the same time, children of such mothers are much more likely to need resuscitation during childbirth and increase the risk of death during childbirth or after birth.

Putting women at the center of care is critical to creating a positive pregnancy experience—the biomedical and physiological aspects of health services need to be complemented by social, cultural, emotional and psychological support.

However, many women, even in developed countries with access to the best health care systems, do not receive adequate care after the loss of a child. Even the language used by medical professionals in relation to miscarriage and stillbirth can be traumatic in itself: the use of terms such as "cervical failure" or "dead gestational sac" can be painful.

Andrea, 28, stylist and singer, Colombia

“When I was 12 weeks pregnant, I had a scheduled appointment with the doctor, where I had an ultrasound. The doctor told me that I was not doing well, but did not specify what exactly was wrong. The next day, when I woke up, I noticed blood stains on the sheets. I didn't get any information about why I had a miscarriage. My doctor was very kind to me, but he didn't explain anything to me. But the nurses were completely indifferent and unfriendly and behaved as if I had undergone an ordinary medical procedure, and nothing more. No one gave me any support."

My doctor was very kind to me, but he didn't explain anything to me. But the nurses were completely indifferent and unfriendly and behaved as if I had undergone an ordinary medical procedure, and nothing more. No one gave me any support."

Depending on the rules of the particular medical facility, stillborn bodies may be treated as clinical waste and may be incinerated. It happens that when a woman learns that her child has died, she is forced to continue to carry the dead baby for several weeks before she can give birth. Even if this delay may be clinically justified, this situation is excruciating for both the woman and her partner. Even in developed countries, women may be forced to give birth to their dead babies in maternity wards, surrounded by women who have healthy children, which is very difficult from a psychological point of view and reminds the woman of her loss.

Not all inpatient or outpatient facilities can adopt a new care strategy or provide more services. This is the reality that reflects the overload of health systems. And yet, there is no extra cost to be more sensitive in dealing with bereaved couples and to remove the taboo and stigma around talking about the loss of a child. This is evidenced by some of the stories told here.

This is the reality that reflects the overload of health systems. And yet, there is no extra cost to be more sensitive in dealing with bereaved couples and to remove the taboo and stigma around talking about the loss of a child. This is evidenced by some of the stories told here.

Medical staff are fully capable of being sensitive and compassionate, acknowledging the depth of the parents' feelings, providing clear information about the situation, and understanding that parents may need special support, both in relation to the loss of a child and in relation to the possible desire for more children. . To provide competent maternal and newborn health care and to meet the requirements for clinical competence in general, it is necessary that this care be provided from a human rights perspective, on the basis of respect, protecting the dignity of patients and taking into account their socio-cultural characteristics.

Learn more about the work of WHO

Learn more about the work of WHO in collaboration with partner organizations

Coping with the loss of a child - together

There is nothing more devastating in the world than the death of a child. It is difficult for families to imagine how to cope with such a loss. While parents never stop thinking about and missing their child, grief changes over time. According to parents, the acute and deep feelings of grief become less pronounced and more manageable over time. However, each person experiences grief differently. Grief does not follow a set schedule or pattern. Today you can feel progress, and tomorrow the simplest tasks seem impossible. Sometimes family members are surprised or even guilty to find that they have regained the ability to laugh at something. These feelings and reactions are natural.

It is difficult for families to imagine how to cope with such a loss. While parents never stop thinking about and missing their child, grief changes over time. According to parents, the acute and deep feelings of grief become less pronounced and more manageable over time. However, each person experiences grief differently. Grief does not follow a set schedule or pattern. Today you can feel progress, and tomorrow the simplest tasks seem impossible. Sometimes family members are surprised or even guilty to find that they have regained the ability to laugh at something. These feelings and reactions are natural.

Watch this video

Grief

Grief is a natural reaction to the loss of a loved one. This feeling is individual. Everyone experiences grief in their own way, with different strengths and for different times. There is no standard set of emotions that you should feel after losing a child. Common feelings and reactions include:

- shock

- sadness

- fear

- anger

- guilt

- sadness

- feeling of loneliness

- anxiety and constant agitation

- unwillingness to contact others

- constant thoughts and memories of the child

- dreams of spending a little more time with the child and longing for missed moments

- trouble falling asleep and insomnia

- excessive sleepiness

- changes in appetite

- loss of interest in entertainment

- trouble concentrating

Everyone can experience grief, but everyone experiences it in their own way. Even in the same family, spouses can have completely different reactions. Children and teens also experience grief in their own way, with different emotions and behaviors ranging from tears and sadness to disobedience and guilt. All these feelings are normal.

Even in the same family, spouses can have completely different reactions. Children and teens also experience grief in their own way, with different emotions and behaviors ranging from tears and sadness to disobedience and guilt. All these feelings are normal.

Watch this video

When to seek help

Counseling professionals—psychologists, counselors, and social workers—can be a source of support during bereavement. If a person asks for help, this does not mean that he somehow experiences his grief incorrectly. For some families, a mental health professional simply provides additional support. Parents and siblings of a departed child are often afraid that their friends and relatives will get tired of hearing about their grief. With a consultant, you can calmly share your experiences. A mental health professional creates a safe environment in which to talk about feelings and helps parents and siblings cope with grief.

In some cases, family members may present with symptoms of a psychiatric disorder such as anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Specific thoughts and feelings to discuss with a mental health professional:

Specific thoughts and feelings to discuss with a mental health professional:

- thoughts about reuniting with the child

- thoughts of hurting yourself or someone else

- sense of worthlessness

- slow movement

- auditory and visual hallucinations

- serious anxiety or anxiety

- sleep problems, nightmares

- difficulty with daily activities

- refusal to believe in the death of a child

- avoiding baby reminders

- indignation

- loss of meaning and purpose in life after the death of a child

- sense of detachment

- sudden frightening memories that make you feel like you are reliving them

If you have thoughts of harming yourself or others, seek help immediately.

- Call the emergency number (112 in Russia, 911 in the US) and report these thoughts.

- Call the number of the Unified Helpline 8-800-2000-122 or the Emergencies Ministry's emergency psychological helpline 8(495)989-50-50.