How to stop autistic child from running back and forth

Mom perplexed by toddler stimming

Our two-year-old has started running back and forth while shaking things – a string, wire, pencils, hangers, whatever – in his left hand. He does this for hours and has started doing it in public. How can I find a substitute for this behavior and/or limit the time he spends doing it? He has a fit if I take away what he’s shaking. But it’s becoming extreme, and people are starting to notice.

Today’s “Got Questions?” answer is by psychologist Stephanie Weber, of the Kelly O’Leary Center for Autism Spectrum Disorders at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. The center and hospital are part of Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network.

Editor’s note: The following information is not meant to diagnose or treat and should not take the place of personal consultation, as appropriate, with a qualified healthcare professional and/or behavioral therapist.

Thank you for your question. I hear similar concerns from many families whose children come to our autism center for behavioral therapy. It’s great that you’re being proactive in recognizing that these repetitive behaviors can become barriers to your son interacting with people who don’t understand them.

Safety first

Before we get into why your son is doing these things and how to work with him, let’s first make sure he’s safe. So please take a look at the wires, pencils, hangers or other objects that he likes to shake and consider whether they could hurt your son if he, say, falls or shakes them too wildly. If so, it’s best to keep them – and other dangerous objects – out of his reach and sight.

Understanding self-soothing behaviors

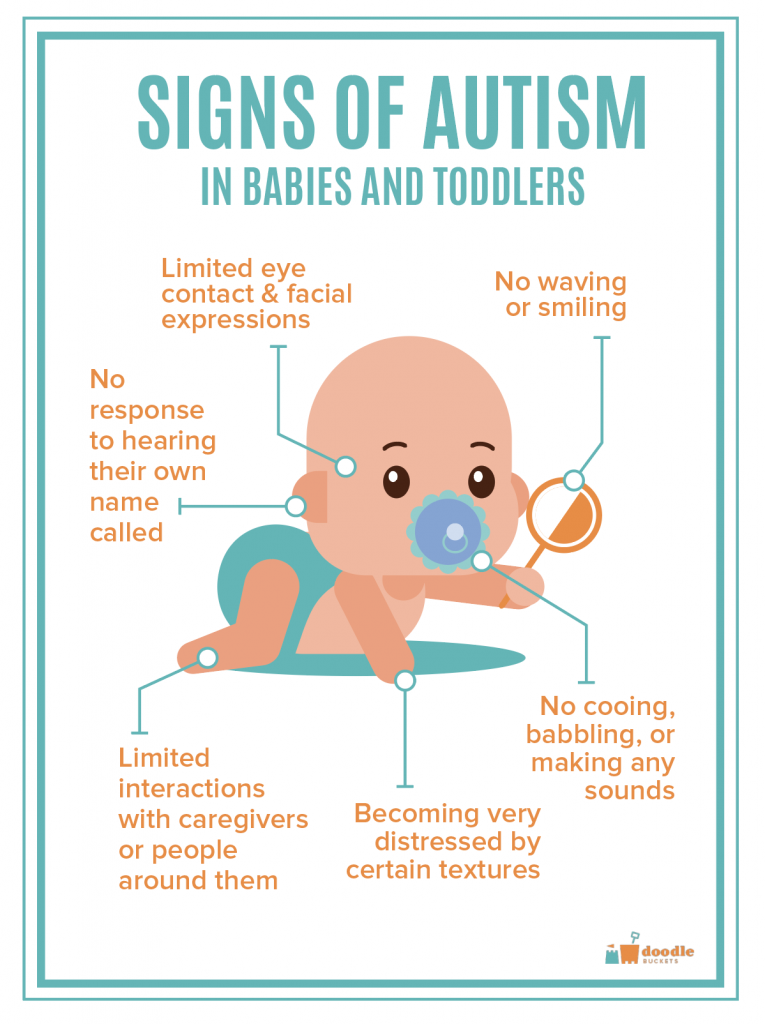

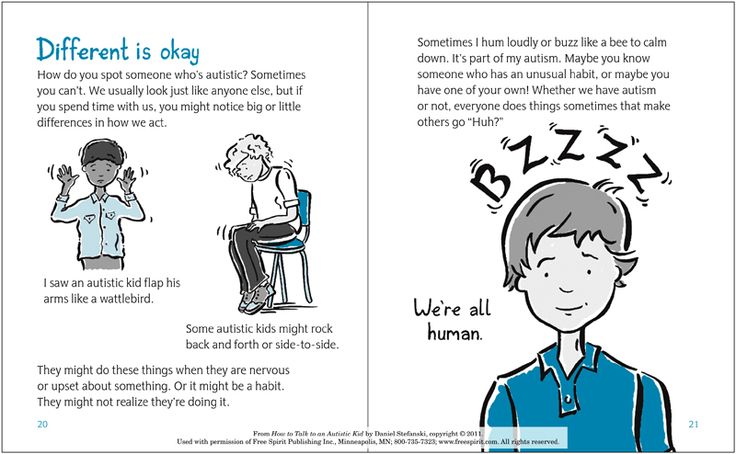

Many children and adults who have autism find it soothing to rock, walk on their toes, flick items in front of their eyes and flap their hands. These are just a few examples of autism-related repetitive behaviors that can be self-stimulating or self-calming.

Are there certain situations that trigger this behavior for your son? If so, it may be that he’s using the behavior to calm himself. It will help if you can avoid or limit the triggering situations to the extent possible.

In any case, from your description of the way your son runs back and forth shaking items for hours, I think it’s very likely that it feels really good to him. In addition, your son may not grasp how to play the way other children do.

Many families come to me perplexed, saying “We have so many toys! I don’t understand why my child just wants to flick and shake things!” I explain that – despite having a wide variety of toys – many children who have autism don’t know how to play with them in the ways we expect.

The types of play we consider “natural” can seem confusing or frustrating to many children who have autism. As a result, they entertain themselves with activities just like the ones you describe in your question.

Learning how to play

My first suggestion is to help your toddler learn how to play with a simple toy. You might need to use gentle hand-over-hand prompting to show him how.

You might need to use gentle hand-over-hand prompting to show him how.

Hand-over-hand prompting is just like it sounds: You put one or both of your hands over his to guide his motions to complete a task. You can do this with many kinds of toys such as ring stackers, shape sorters, simple puzzles, activities that involve matching picture, putting pennies in a piggy bank … and the list goes on!

When teaching your child new ways of playing, make sure to provide verbal praise. For example, “Great job. You put the orange ring on the peg!” In addition to providing positive reinforcement, this helps your son build language and gives him specific information on what you’re expecting from him.

Redirecting and reinforcing

Many children who have autism aren’t easily redirected away from the activities they love. It sounds like that may be the case with your 2-year-old. Often a reward can help motivate a change. For example, does your son have a favorite video? You can explain that he’ll get to watch a short clip from the video after the two of you finish stacking the blocks together. Or perhaps he’ll be motivated by a few mini M&Ms or a hug and tickle. You know your son and what motivates him.

Or perhaps he’ll be motivated by a few mini M&Ms or a hug and tickle. You know your son and what motivates him.

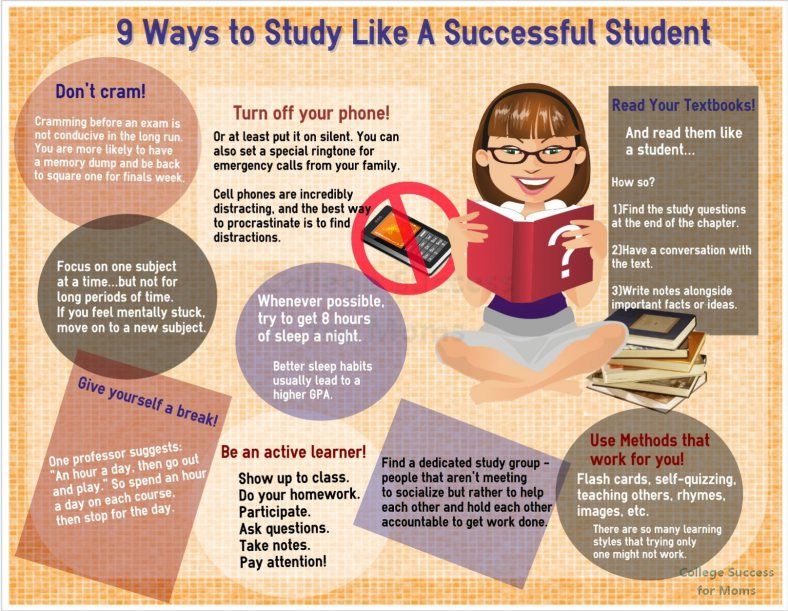

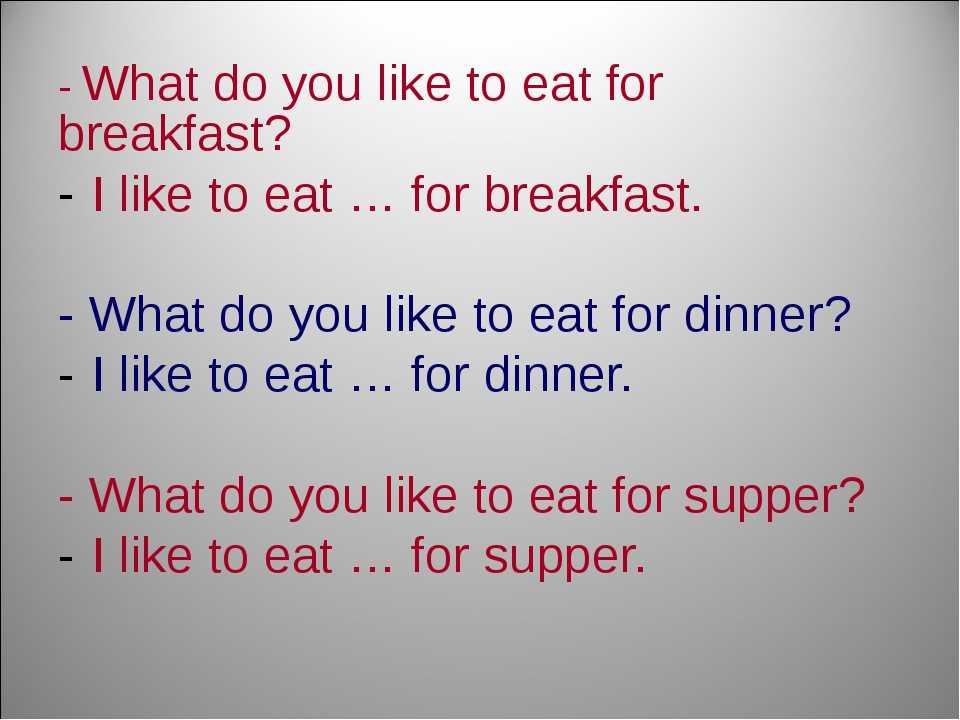

Communicating with visual supports

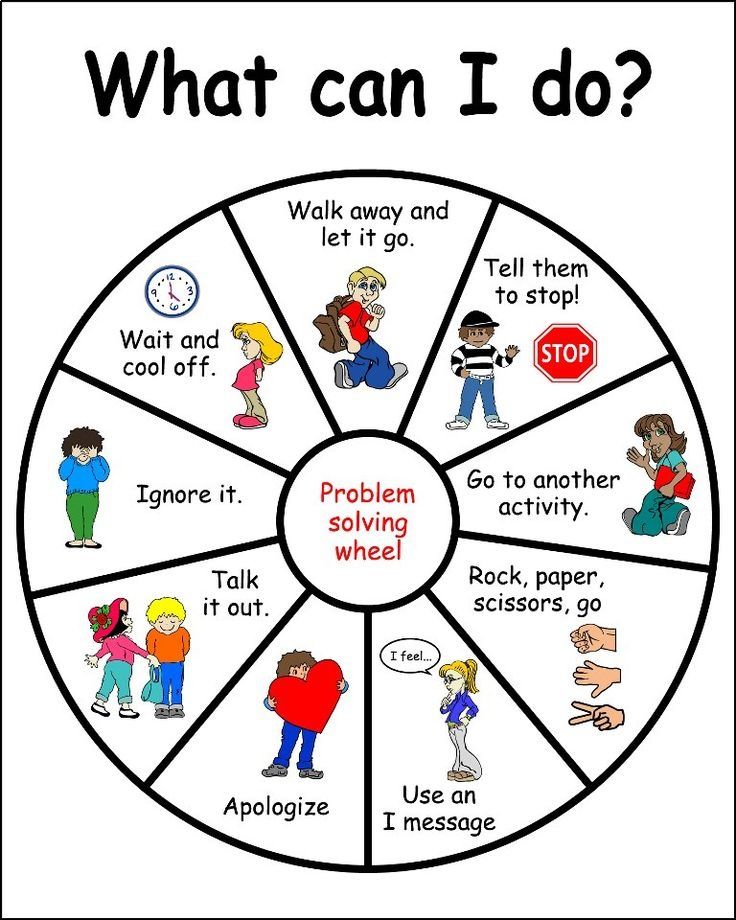

Some children with autism respond better to visual than spoken directions. Hasbro has created a number of visual supports, social narratives and “how-to” guides for helping children with autism learn to play in a meaningful ways. Check out its Autism Project website for more information.

The Autism Speaks Visual Supports tool kit is another great resource.

Learn more about visual supports and download the Autism Speaks ATN/AIR-P Visual Supports Tool Kit.

Encouraging functional behaviors

Through the strategies described above, your aim is to help your son replace some of his “nonfunctional” behaviors with functional ones. By nonfunctional, we mean that the behavior isn’t helping your son communicate or connect with others or to accomplish a task – such as playing in a way that can build important skills.

At the same time, it’s important to remember that it does not work to take away a child’s favorite activities without giving him or her something else that feels good. That’s why the verbal encouragement and rewards can be so important as your son learns to enjoy playing in a more functional manner.

A place and time for self-soothing

It’s also important to build times into the day when it’s okay for your child to engage in the self-stimulatory behaviors that feel good to him. I suggest that you clearly explain to him when and where these behaviors are okay and when and where they are not appropriate.

Consider drawing up a short list of rules concerning when, where and how long your child can engage in the self-stimulatory behavior. For example, some families find it works to allow a child to engage in the behavior for a few minutes at certain times a day, but only at home. Some families encourage their children to engage in the behavior only in their own bedrooms. This has the added lesson of making clear that these behaviors are not appropriate for social settings.

This has the added lesson of making clear that these behaviors are not appropriate for social settings.

You can plan for those times when the repetitive behaviors are not okay by having a favorite toy or other distraction ready to help redirect your child.

Keep using those visual supports

With a child as young as two, it will be very important to use pictures to go along with new rules. Visual supports can help you convey what you expect.

Along these lines, a visual daily schedule can help you make clear when different behaviors are appropriate. On the calendar, you can draw a picture to illustrate “Free Time” or “Sammy’s choice of activity” at the appropriate time or times during the day. Then teach your son – through lots of reminders and practice – that this is the time he can engage in his self-soothing behaviors.

Most two-year-olds are just learning how to stay focused on an activity for 5 to 10 minutes at a time. So timers can be another great tool to let your child know when one activity is over and the next one begins. This includes using the timer to show your child how long he can engage in his self-soothing behavior. When the timer goes off, it’s time to do something new.

This includes using the timer to show your child how long he can engage in his self-soothing behavior. When the timer goes off, it’s time to do something new.

It may help to give your child a special box where he can put away the string or other object he likes to shake. Then he knows it’s safe and waiting for the next scheduled time.

Another great way to use visual supports to direct your son’s activities is with a “First/Then Board.” The “first” picture shows the child what activities he or she needs to complete before moving on to a desired activity. For example, the “first” picture might show your child playing with the ring stacker. In the “then” box, you can put a picture of your son running back and forth with his string! Photos can be particularly helpful for young children who don’t yet understand that cartoon drawings symbolize real people and objects.

Once your child feels more comfortable with the new activities you’ve introduced (e.g. playing with toys) at home, I recommend introducing enjoyable activities that your son can do with the family in public. For example, reading a book together on a park bench or while waiting for a doctor’s appointment. Practice these new activities at home first and then try when out in the community.

For example, reading a book together on a park bench or while waiting for a doctor’s appointment. Practice these new activities at home first and then try when out in the community.

Thank you again for your question!

Readers: Got Questions for our behavioral and medical experts? Send them to [email protected].

Stimming: children & teens with autism

About stimming and autism

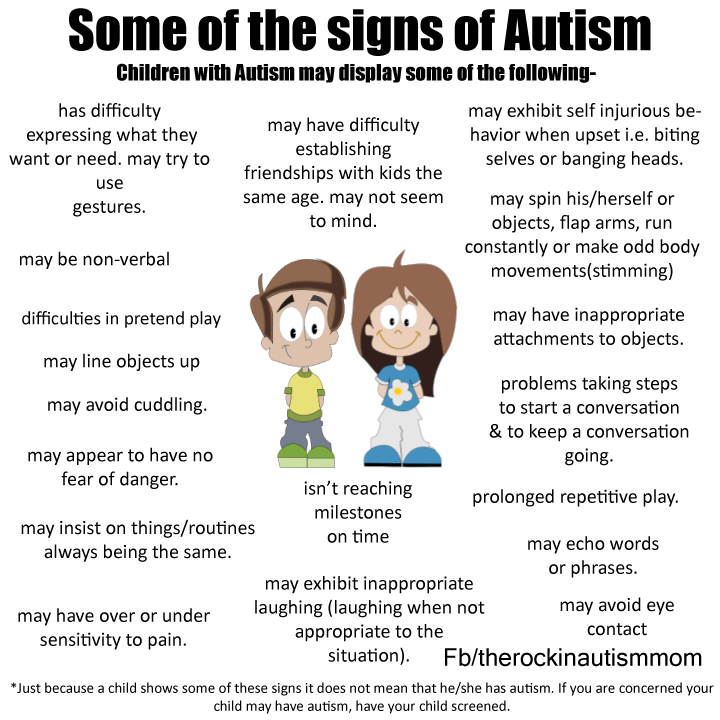

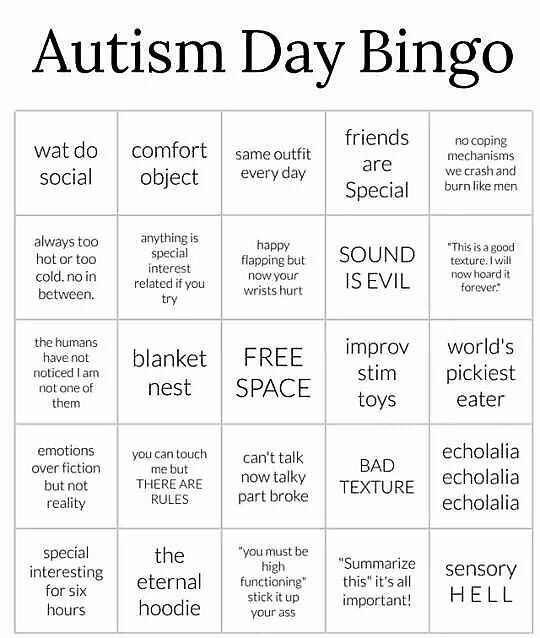

Stimming – or self-stimulatory behaviour – is repetitive or unusual body movement or noises. Stimming might include:

- hand and finger mannerisms – for example, finger-flicking and hand-flapping

- unusual body movements – for example, rocking back and forth while sitting or standing

- posturing – for example, holding hands or fingers out at an angle or arching the back while sitting

- visual stimulation – for example, looking at something sideways, watching an object spin or fluttering fingers near the eyes

- repetitive behaviour – for example, opening and closing doors or flicking switches

- chewing or mouthing objects

- listening to the same song or noise over and over.

Many autistic children and teenagers stim, although stimming varies a lot among children. For example, some children just have mild hand mannerisms, whereas others spend a lot of time stimming. Stimming can also vary depending on the situation. For example, some children stim, or stim more, when they’re feeling stressed or anxious.

Why autistic children and teenagers stim

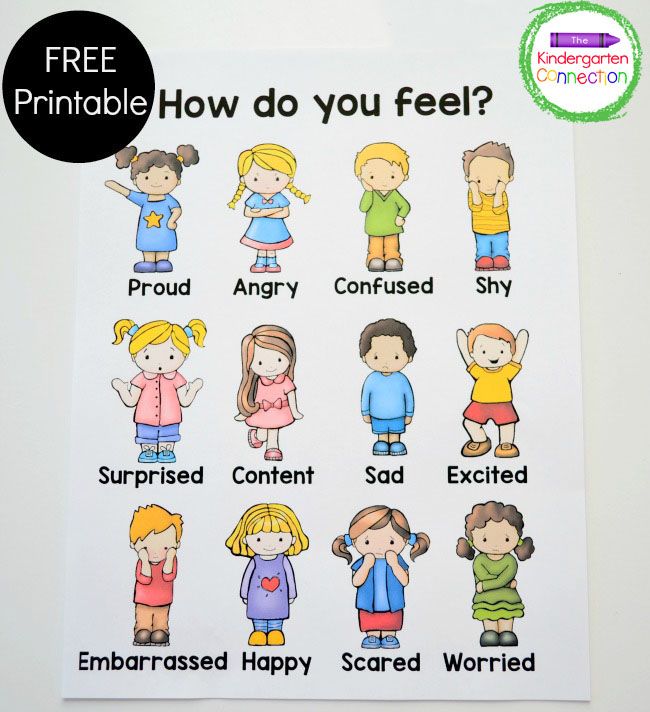

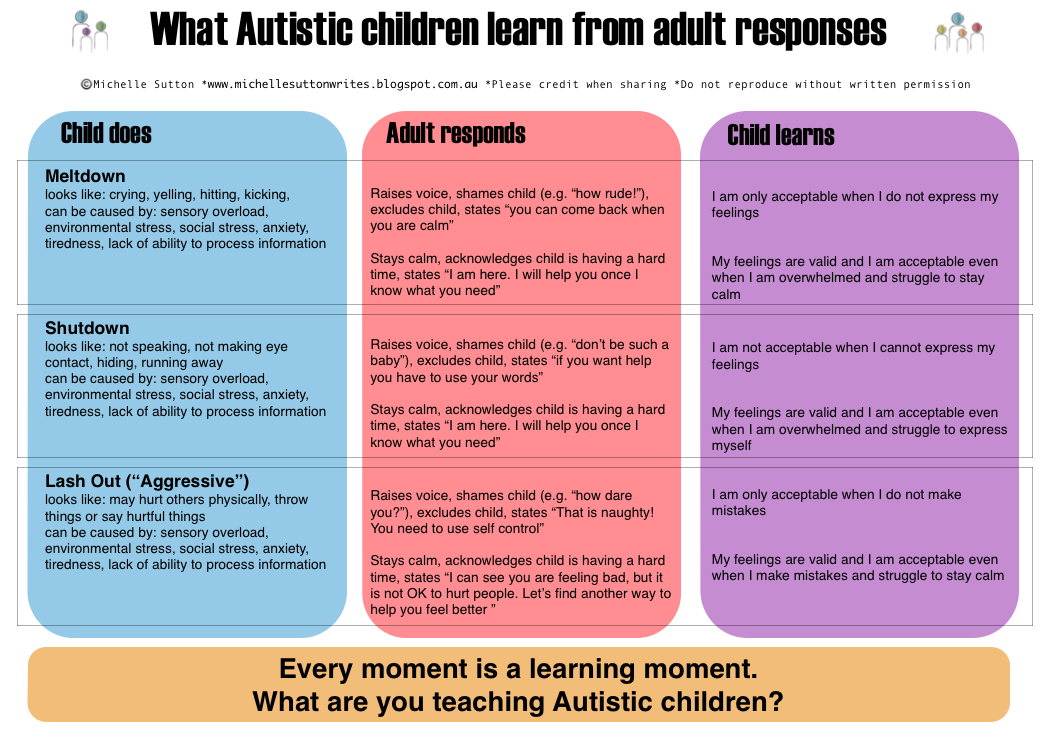

Stimming seems to help autistic children and teenagers manage emotions like anxiety, anger, fear and excitement. For example, stimming might help them to calm down because it focuses their attention on the stim or produces a calming change in their bodies.

Stimming might also help children manage overwhelming sensory information. For autistic children who are oversensitive to sensory information, stimming can reduce sensory overload because it focuses their attention on just one thing. For autistic children who are undersensitive, stimming can stimulate ‘underactive’ senses.

How stimming affects autistic children and teenagers

Stimming isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as long as it doesn’t hurt your child. But some stimming can be ‘self-injurious’ – for example, severe hand-biting.

Stimming can also affect your child’s attention to the outside world, which in turn can affect your child’s ability to learn and communicate with others.

For example, if a child flicks their fingers near their eyes, they might not be playing with toys so much and not developing play skills. When the child is older, if they’re absorbed in watching their hands in front of their eyes in the classroom, they’re not engaged with schoolwork. Or if the child is pacing around the fence in the playground, they’re missing valuable social opportunities.

We all use stimming sometimes. For example, some children suck their thumbs or twirl their hair for comfort, and others jiggle their legs while they’re working on a difficult problem or task. You might pace up and down if you’re anxious, or fiddle with a pen in a boring meeting.

You might pace up and down if you’re anxious, or fiddle with a pen in a boring meeting.

Helping autistic children and teenagers with stimming

Many autistic people feel they should be allowed to stim because stimming helps them to manage emotions and overwhelming situations. But if stimming is hurting your child or affecting their learning, social life and so on, it might be best for your child to stim less often.

You might be able to reduce your child’s need to stim by changing the environment or helping your child with anxiety. Also, stimming often reduces as your child develops more skills and finds other ways to deal with sensitivity, understimulation or anxiety.

Changing the environment

If your child finds the environment too stimulating, your child might need a quiet place to go, or just one activity or toy to focus on at a time.

If your child needs more stimulation, your child might benefit from music playing in the background, a variety of toys and textures, or extra playtime outside.

Some schools have sensory rooms for autistic children who need extra stimulation. There might be equipment children can bounce on, swing on or spin around on, materials they can squish their hands into, and visually stimulating toys.

Working on anxiety

If you watch when and how much your child is stimming, you might be able to work out whether the stimming is happening because your child is anxious. Then you can look at your child’s anxiety and change the environment to reduce their anxiety.

For example, is there something new or changed in your child’s environment? Preparing your child for new situations and teaching your child new skills to deal with things that cause the anxiety can reduce stimming.

Where to go for help with stimming

Occupational therapists can help you look at environmental adjustments to support your child.

If your child’s behaviour is causing your child harm or hurting other people, speak to your child’s GP, paediatrician, psychologist, another health professional working with your child, or school support staff.

There are therapies and supports that can help with stimming if that’s what your child needs. These therapies and supports are listed in our Parent Guide to Therapies. Each guide gives an overview of the therapy, what research says about it, and the approximate time and costs involved in using it.

Sitemap - Soviet Psychoneurological Dispensary

Version for visually impaired

- Home

- About Hospital

- About the Hospital

- Licenses

- Branches

- Jobs

- Structural divisions

- Anti-corruption activities

- Mode and work schedule

- Appointment schedule by manager

- Constituent documents

- Management personnel reserve

- Accounting policy

- Report on the activities of the institution

- Our achievements

- Structure

- Information for sponsors

- Services

- State task

- Paid services

- Procedure for the provision of paid medical services

- Professional qualifications and certification

- Supervisory authorities

- Details for payment for paid medical services

- For patient

- Contact information for citizens

- Right to medical care

- Regulations

- Drug supply

- Hospitalization

- Crisis Prevention

- Information for the public

- Patient Information

- Internal regulations for consumers of services

- Contacts of executive authorities of subjects of the Russian Federation

- Medical insurance organizations

- Labor protection

- Teaching materials for parents

- Rules for conducting diagnostic tests

- Medical Prevention

- Video

- Medical prophylaxis

- Addiction Prevention

- Reviews

- Information for patients with disabilities

- Contacts

- Employers

|

|

What about self-stimulating behavior? | Autistic City

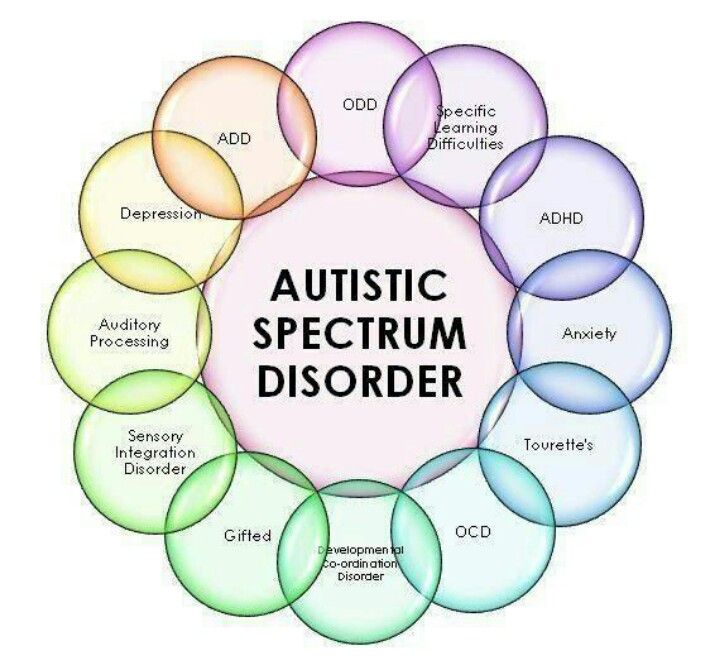

In addition to socialization, the most common topic in the discussion of autism is self-stimulating behavior or "stimming". For those who don't know, stimming refers to clearly non-functional, repetitive movements. This is a rather vague definition, so I will give some examples of what is referred to as stimming. "Stims" can include motions such as rocking back and forth, twisting your fingers and pulling your hair, rocking from side to side, circling in one place, walking quickly back and forth, shaking your hands, or scratching your skin. By the way, breathing or blinking are also repetitive movements, but since they serve a specific and explicit purpose, they are not classified as stimming. The term stimming is also used to refer to behaviors that resemble obsessive-compulsive disorder, such as arranging objects in straight lines. The reason for this behavior is different, but it is still called stimming, despite the different reasons.

For those who don't know, stimming refers to clearly non-functional, repetitive movements. This is a rather vague definition, so I will give some examples of what is referred to as stimming. "Stims" can include motions such as rocking back and forth, twisting your fingers and pulling your hair, rocking from side to side, circling in one place, walking quickly back and forth, shaking your hands, or scratching your skin. By the way, breathing or blinking are also repetitive movements, but since they serve a specific and explicit purpose, they are not classified as stimming. The term stimming is also used to refer to behaviors that resemble obsessive-compulsive disorder, such as arranging objects in straight lines. The reason for this behavior is different, but it is still called stimming, despite the different reasons.

All people stim from time to time. For example, when people are bored, they may start tapping their fingers on the table, playing with their hair, or twiddling their thumbs. The difference between normal stimming and autism stimming is only a matter of degree and frequency. While any normal person may have the habit of tapping their fingers from time to time, an autistic person will jump and spin around the room (which is much more conspicuous), and they will also do it much more often. The question is why does he do it? The best explanation is that stimming is the body's way of understanding how to perceive everything around.

The difference between normal stimming and autism stimming is only a matter of degree and frequency. While any normal person may have the habit of tapping their fingers from time to time, an autistic person will jump and spin around the room (which is much more conspicuous), and they will also do it much more often. The question is why does he do it? The best explanation is that stimming is the body's way of understanding how to perceive everything around.

Sensory feedback

When we are first born, we do not perceive sensory signals. For example, a small child who is just learning to walk has the muscle strength to walk upright, but when he gets up, he immediately falls down. This is because he has not yet figured out his own feelings. He doesn't know that a certain amount of pressure in his heels means he's falling backwards, or that pressure in his toes means he's falling forward. He has not yet developed the skills to receive sensory feedback. In order to develop sensory feedback (and thus better control of their body), a young child needs as much sensory stimulation as possible to test different sensations and "calibrate" all of their senses.

That's why babies put everything in their mouths. They develop in this way a sense of taste and touch. Therefore, do not feed small children with bread, let them balance on some curbs or logs. No wonder playgrounds are equipped with various swings, carousels and slides. For young children, this is an opportunity to develop tactile feedback, and they are biologically predisposed to do so. A small child does not talk about the need to swing because he has calculated how developed his senses are and determined that he needs more practice. A small child loves to play on the swing because he has a subconscious, instinctive desire to develop his sensory experience, and this makes things like trampolines a source of great fun.

As people get older and become more sensory oriented, they don't get the same pleasure from balancing on a beam or swinging on a swing. While a two-year-old child derives great joy from balancing or rocking, this is due to the instinctive need to test his sensations and get to know the world around him better. As people grow up and become familiar with the world around them, the instinctive desire to test their sensations disappears. So swings and carousels lose their former appeal that they had in childhood. The reason autistic people engage in self-stimulating behavior is because they are "stuck" in this infantile phase of developing their own senses. In other words, their brains have never decided what the world around them is like.

As people grow up and become familiar with the world around them, the instinctive desire to test their sensations disappears. So swings and carousels lose their former appeal that they had in childhood. The reason autistic people engage in self-stimulating behavior is because they are "stuck" in this infantile phase of developing their own senses. In other words, their brains have never decided what the world around them is like.

As with other manifestations of autism, this is due to the fact that the functioning and development of the brain is different from normal. When a small child plays on a swing or spins in one place, his brain receives sensory feedback. But unlike the average person who learns from this feedback, in the autistic person this information is lost or misinterpreted. This means that their senses never become "calibrated" and the desire for sensory experiences remains very similar to the behavior of an infant.

Stimming is more than just getting tactile feedback. All human feelings need calibration. So your child may be walking back and forth and making strange noises or talking to himself just to hear his own voice. This means that he is trying to calibrate his auditory perception. All ordinary small children do something similar - at first they just walk, then they repeat other people's words and phrases, then they talk to themselves. When an older child keeps repeating the same words over and over or making sounds, this is simply an attempt to satisfy the body's need for feedback. In the same way, your child may swing or shake various objects in front of his eyes - this is an attempt to calibrate visual perception. Stimming doesn't have to be a movement like rocking back and forth.

All human feelings need calibration. So your child may be walking back and forth and making strange noises or talking to himself just to hear his own voice. This means that he is trying to calibrate his auditory perception. All ordinary small children do something similar - at first they just walk, then they repeat other people's words and phrases, then they talk to themselves. When an older child keeps repeating the same words over and over or making sounds, this is simply an attempt to satisfy the body's need for feedback. In the same way, your child may swing or shake various objects in front of his eyes - this is an attempt to calibrate visual perception. Stimming doesn't have to be a movement like rocking back and forth.

This explains why stimming is usually noticed only when the child is older. When a one-year-old child winds circles or jumps from one foot to another, parents consider this to be completely normal behavior. However, when an autistic eight-year-old does the same thing all the time, it seems a bit odd and labeled "self-enhancing behavior. " In reality, your older child is just doing the same thing as a very young child, he instinctively tests his feelings. As in the case of a very young child, an autistic person does not do this consciously, he does not choose to stim. This is a completely instinctive process, it happens unconsciously, automatically. Very often, autistic people themselves are not aware of their stimming, for example, they do not notice that they have begun to sway back and forth, just as a small child does not notice this.

" In reality, your older child is just doing the same thing as a very young child, he instinctively tests his feelings. As in the case of a very young child, an autistic person does not do this consciously, he does not choose to stim. This is a completely instinctive process, it happens unconsciously, automatically. Very often, autistic people themselves are not aware of their stimming, for example, they do not notice that they have begun to sway back and forth, just as a small child does not notice this.

From a more personal point of view, I can tell you that I don't even notice or think about stimming when I start doing it. I usually pick at the skin on my arms when I watch TV. I don't even notice it until the commercial starts and I don't look at my hands - only then do I see what I'm doing. I almost always do something unconsciously with my hands. Sometimes I rub them together, sometimes I pick at the skin, sometimes I twist my fingers, sometimes I start playing with something. I never try to do something like that, my hands start doing such things absolutely automatically, if I get distracted even for a second.

I never try to do something like that, my hands start doing such things absolutely automatically, if I get distracted even for a second.

The best analogy I can think of for stimming is breathing. You can think about your breath, you can control your inhalation and exhalation. However, as soon as you focus on something else, you will begin to breathe absolutely automatically. Similarly, I can focus and stop stimming, but as soon as I focus on something else, my hands will start doing it again, I need to think about my hands to stop them.

Obsessive-compulsive tendencies

Some people believe that obsessive behavior, such as aligning objects or doing the same routine every day, is a type of stim. This is a valid categorization because obsessive-compulsive behavior is usually repetitive and non-functional. However, it is important to understand that unlike other stimming, this behavior is not caused by sensory feedback. The basis of such behavior is the desire for order and a rigid routine.

As I have said in previous chapters, predictable order and routine make life very easy. They make everything simpler, more understandable and predictable, and this reduces the anxiety associated with uncertainty. In addition, when everything around is in its place, it is very pleasant and soothing. For the most part, there is nothing wrong with establishing a rigid order or routine in the performance of certain tasks. This makes it easier to perform and reduces stress, but in some situations, deviation from the established routine is necessary, and in these cases, obsessive-compulsive tendencies can lead to problems.

Benefits of stimming

The next topic of discussion is the potential benefits of stimming. At first glance, stimming seems like a stupid and useless waste of time. The very definition of stimming says that it is not functional, so what use can it be? The answer is that the benefits of stimming are emotional.

In other words, stimming makes the autistic person feel good. As I mentioned, autistic people stim because they have an instinctive need to do so. This need is purely unconscious, so nothing can be done about it. You can learn to delay stimming so that you can do it in the least problematic situations, but an autistic person can never completely get rid of this need, for him it is like completely getting rid of hunger. So if your child is stim, then it satisfies his instinctive need and can bring great pleasure, just like his favorite food.

As I mentioned, autistic people stim because they have an instinctive need to do so. This need is purely unconscious, so nothing can be done about it. You can learn to delay stimming so that you can do it in the least problematic situations, but an autistic person can never completely get rid of this need, for him it is like completely getting rid of hunger. So if your child is stim, then it satisfies his instinctive need and can bring great pleasure, just like his favorite food.

Stimming is very useful if a person needs to calm down. I can't know why this happens, I can only assume that it's like when a person gets better from a favorite treat. Satisfying an instinctive need makes us feel better and helps us calm down. It's like when people eat ice cream to cheer themselves up.

Stimming also helps us in stressful situations because it allows us to get rid of problematic attitudes. If you focus on rocking back and forth, then it is easier for you to focus on the most important and block out the chaos in the environment. In a nutshell, stimming makes us feel better and helps us deal with stress better.

In a nutshell, stimming makes us feel better and helps us deal with stress better.

Problems with stimming

Now that we've covered the benefits of stimming, it's time to look at the problems associated with it. The first problem is that stimming looks very strange. Personally, I am of the opinion that the strange appearance is not a problem in itself. There is nothing scary in a slightly bizarre way. But when a bizarre appearance causes abuse and violence from other people, then it becomes a problem. The second problem is that stimming can annoy other people. And the third problem is that sometimes stimming causes physical damage to the child. So let's look at these issues in more detail.

The first problem, as I just said, is that stimming looks weird. This leads to problems if people who observe strange behavior draw erroneous conclusions. For example, if you seem strange during a job interview, then you are unlikely to get this job. Strange appearance is also a problem if you want to make a good first impression. The problem is that people always assume the worst and are unaware of the real problem of the autistic person. However, since an autistic person has to live with other people's misguided ideas, they may be concerned about how not to look crazy in situations where making a good first impression is important.

The problem is that people always assume the worst and are unaware of the real problem of the autistic person. However, since an autistic person has to live with other people's misguided ideas, they may be concerned about how not to look crazy in situations where making a good first impression is important.

The second problem is that sometimes stimming annoys other people. For example, spinning in one place, waving arms and making sounds are not a problem if the child is alone in his room. However, in the classroom, this behavior can be distracting and disturbing to those around you.

Similarly, some of the child's stims can be problematic in themselves, such as the habit of getting bottles of liquid soap and pouring all the soap on their hands, because they like the feel of soap. Or the child may be annoying because he chews his shirt all the time and ruins new things. Again, these stims are usually not a problem in and of themselves, but cause problems for other people. In the interest of society as a whole, your child should probably try to refrain from such activities if they are problematic for others.

In the interest of society as a whole, your child should probably try to refrain from such activities if they are problematic for others.

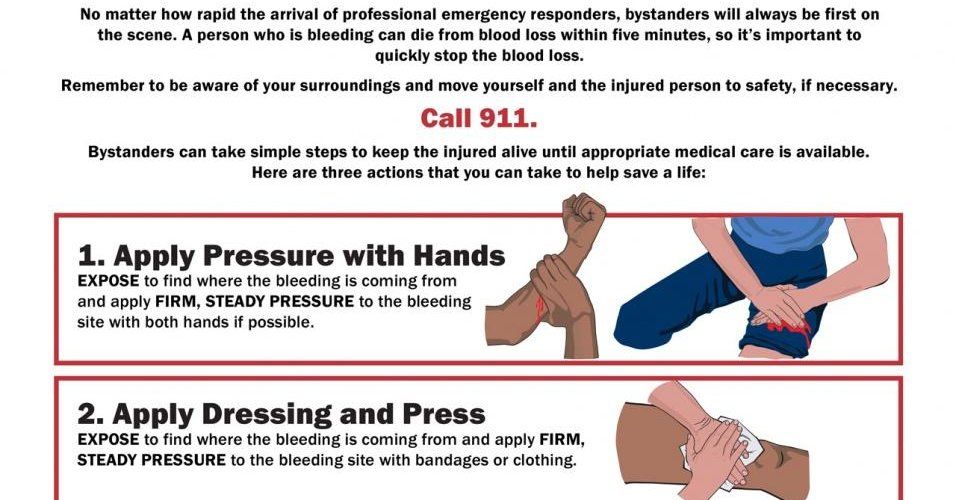

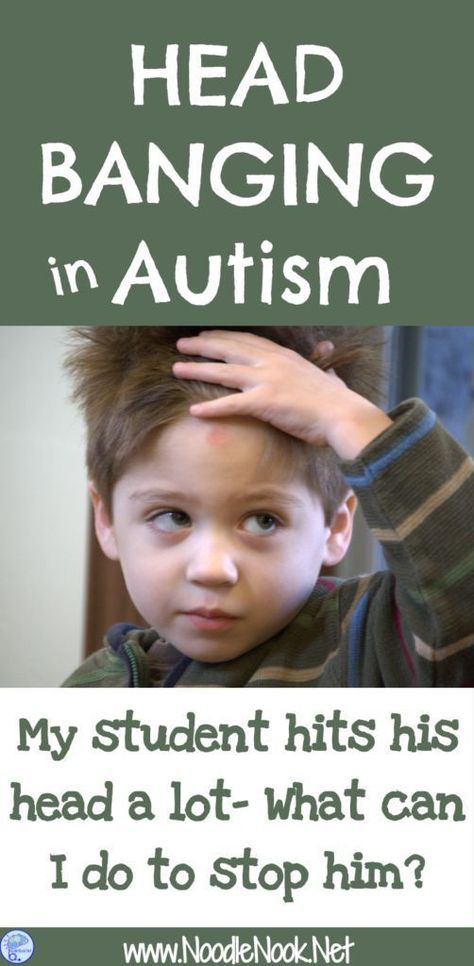

Finally, the third problem with stimming is that it can be physically harmful to the child himself. As I mentioned earlier, your child may have an unusual feeling of pain. What should cause pain may just be an unusual sensation for him. People who don't perceive pain may pick at their skin and bang their heads against things because they enjoy the sensations. This is partly due to endorphins, which are released during injuries. These endorphins cause feelings of well-being and joy. The purpose of endorphins is to reduce pain and allow functioning after an injury. However, in the absence of pain, these endorphins become just a way to feel good. This can lead to self-harm, especially in situations of acute stress where the person is trying to quickly reduce stress in this way.

Obviously, you don't want your child to harm themselves, even permanently. This is of no use to anyone. However, this does not mean that ALL types of self-harm are extremely problematic and should be stopped immediately. If the child simply picks at the skin or chews on the lips, this is not a problem. I pick at the skin on my hands - I can show the scars, if anything. But I have achieved a lot in life, despite the scarred hands. And your child can do it too. The main thing is that if your child causes any kind of injury to himself, then you need to take precautions to prevent really serious problems. For example, if someone scratches or picks at the skin, then you should always carry plasters with you in case of bleeding. If your child hits his head on something, it's best to choose a soft and safe surface for this (I personally prefer my bed). If your child learns to avoid serious injury, then there is no problem.

This is of no use to anyone. However, this does not mean that ALL types of self-harm are extremely problematic and should be stopped immediately. If the child simply picks at the skin or chews on the lips, this is not a problem. I pick at the skin on my hands - I can show the scars, if anything. But I have achieved a lot in life, despite the scarred hands. And your child can do it too. The main thing is that if your child causes any kind of injury to himself, then you need to take precautions to prevent really serious problems. For example, if someone scratches or picks at the skin, then you should always carry plasters with you in case of bleeding. If your child hits his head on something, it's best to choose a soft and safe surface for this (I personally prefer my bed). If your child learns to avoid serious injury, then there is no problem.

To stim or not to stim

Now that we've covered the basics of stimming, we're left with the question of whether it's a good idea to keep stimming going. However, this does not mean that you should give up stimming entirely. It's just not a realistic goal, and usually it just makes things worse. A much better approach to stimming is to determine what level of stimming is acceptable in a given situation.

However, this does not mean that you should give up stimming entirely. It's just not a realistic goal, and usually it just makes things worse. A much better approach to stimming is to determine what level of stimming is acceptable in a given situation.

For example, there are certain situations where an unusual appearance is highly undesirable. For example, during job interviews and similar situations where you need to make a good first impression. In these situations it is wise to avoid stimming if possible. It usually takes an hour, no longer, so it's a reasonable goal. If stimming cannot be avoided, then you need to switch to the most inconspicuous stim possible. For example, rubbing your hands together or moving your feet in a boot. Rotating the tongue in the mouth can also be imperceptible, if done correctly.

The next item on the list is public places. When you're at school and sitting in a classroom, going to the store, or just being around people, you need to suppress stimming a little, but not to the same extent as during an interview. First of all, it is important to avoid very noisy stimming or anything that attracts everyone's attention, such as rocking back and forth so much that it distracts people sitting behind. In such situations, moderate types of stimming are preferable. For example, rubbing your hands, wringing your fingers, fidgeting in your chair, rubbing your legs together, curling your fingers back, twisting your hair, or picking your skin a little. The idea is that stimming does not attract much attention from others. So try to keep quiet and avoid large or too sudden movements.

First of all, it is important to avoid very noisy stimming or anything that attracts everyone's attention, such as rocking back and forth so much that it distracts people sitting behind. In such situations, moderate types of stimming are preferable. For example, rubbing your hands, wringing your fingers, fidgeting in your chair, rubbing your legs together, curling your fingers back, twisting your hair, or picking your skin a little. The idea is that stimming does not attract much attention from others. So try to keep quiet and avoid large or too sudden movements.

Next on the list is stimming in a group of understanding and friendly people. For example, at home with family or among good friends. Under these circumstances, you can relax about stimming and do the most obvious stims, such as rocking back and forth hard, walking back and forth, lowing under your breath, or doing something that would attract unwanted attention in a public place. My favorite stim in this category is walking back and forth. When I'm at home, I do it all the time - it helps to think. At work, I do it too, only there I pretend to go for a drink of water.

When I'm at home, I do it all the time - it helps to think. At work, I do it too, only there I pretend to go for a drink of water.

The last point is stimming, which is practiced only in solitude. It is mostly done at home when no one is around. If you are alone, then you can do whatever you want. For example, making loud noises, crashing into walls (literally) or bludgeoning things. These most obvious stims can be done with some family members, but since this can be very distracting for them, it is better to go to a separate room. Family members usually don't like loud singing or banging on things while they watch TV.

Stimming or self-harm

One of the most common misconceptions is that all self-harm in autism is stimming. People can put skin picking into one category, and when a person beats himself at the moment of tantrum. These are completely different things. Self-harm while stimming is completely automatic. When I sit still, I always do something with my hands. If there are no other options, I start picking at the skin. I'm not intentionally trying to hurt myself, I just need to do something with my hands. What people think of when they hear the word "self-harm" is the far more dramatic and dangerous act during a tantrum. Self-harm stims are not related to the desire to harm oneself, but during a tantrum, self-harm is aimed precisely at this goal.

If there are no other options, I start picking at the skin. I'm not intentionally trying to hurt myself, I just need to do something with my hands. What people think of when they hear the word "self-harm" is the far more dramatic and dangerous act during a tantrum. Self-harm stims are not related to the desire to harm oneself, but during a tantrum, self-harm is aimed precisely at this goal.

If your child has tantrums that are accompanied by aggression against himself (or others), then you need to help him cope better with stress and prevent tantrums. If you cannot avoid tantrums, then you need to develop a plan of action for this case (for example, take the child to a quiet place without extraneous stimuli). However, this is a problem on a completely different level than just scratching the skin for pleasure.

How can parents help?

Because this book is written for parents looking for helpful advice, I thought I'd include a section on what parents can do to help their child stim more effectively. As I said earlier, stimming is purely an instinctive desire. Thus, trying to completely stop stimming is tantamount to demanding that the person stop eating or sleeping. This does not work. So first of all, parents should learn to understand when their child wants to stim. There is nothing wrong with asking the child to go fast somewhere else if he annoys you. However, if the child is engaged in pleasant stimming when relaxing at home, then this should not be prohibited.

As I said earlier, stimming is purely an instinctive desire. Thus, trying to completely stop stimming is tantamount to demanding that the person stop eating or sleeping. This does not work. So first of all, parents should learn to understand when their child wants to stim. There is nothing wrong with asking the child to go fast somewhere else if he annoys you. However, if the child is engaged in pleasant stimming when relaxing at home, then this should not be prohibited.

Second, parents can provide opportunities for children to stim more effectively. If the child is one of those who like to move a lot, run back and forth and spin in place, then you can help the child channel this energy into a peaceful direction. Mini trampolines are especially popular for this purpose, and most recommend them. Other options are the installation of swings or ladders. In the same way, you can take the child to the park and just let him out on the playground. If your child is a chewer, give him something to chew on. Gum is the obvious solution, as are chewing beads and straws. If you notice that your child is constantly doing something, then you need to find a way to do it in a more efficient, non-destructive and safe way.

Gum is the obvious solution, as are chewing beads and straws. If you notice that your child is constantly doing something, then you need to find a way to do it in a more efficient, non-destructive and safe way.

You can also help your child by purchasing stim toys. These are small items that can be played with during the steam mood. Possible options include: leather balls, elastic band, yo-yo, plasticine and so on. More options can be found here: http://www.officeplayground.com/Fidget-Toys-C102.aspx

Which stim toys you choose is up to you and your child. However, they should be consistent with how your child usually stims. If he likes to move a lot, then a swing is better than plasticine. If he likes to rub his hands together, then plasticine is a good idea. And if he does both, then plasticine with a swing is a good combination. If your child is visually stimmed, consider a lava lamp or toys with lights.

There is a growing trend to use pressure shirts (shirts that squeeze the body to provide little pressure) and weighted vests for sensory feedback. Personally, I don't have a weighted vest or pressure shirt, so I can't judge their effectiveness, but some people find them very useful. They are often recommended to the same people who are recommended trampolines, so it's reasonable to assume that they are suitable for children who move a lot. If you want to find more information, tips and ideas, then type in the search engine the term "sensory diet". So many other people have already found effective stimming devices that have proven to be very useful.

Personally, I don't have a weighted vest or pressure shirt, so I can't judge their effectiveness, but some people find them very useful. They are often recommended to the same people who are recommended trampolines, so it's reasonable to assume that they are suitable for children who move a lot. If you want to find more information, tips and ideas, then type in the search engine the term "sensory diet". So many other people have already found effective stimming devices that have proven to be very useful.

If you decide to order accessories for stimming, then beware of products that are sold at grossly inflated prices. So many people are happy to cash in on panicking parents and put up an insane price for a beautiful name that actually does nothing. For example, a weighted vest or weighted belt can be found at any large sports store for $15. Or you can order "special vestibular sensory weighted vest for the treatment of autism, approved by experts in ABA" for $80. And it will be the same thing, a beautiful name does not make it something else.