How much to raise a child in australia

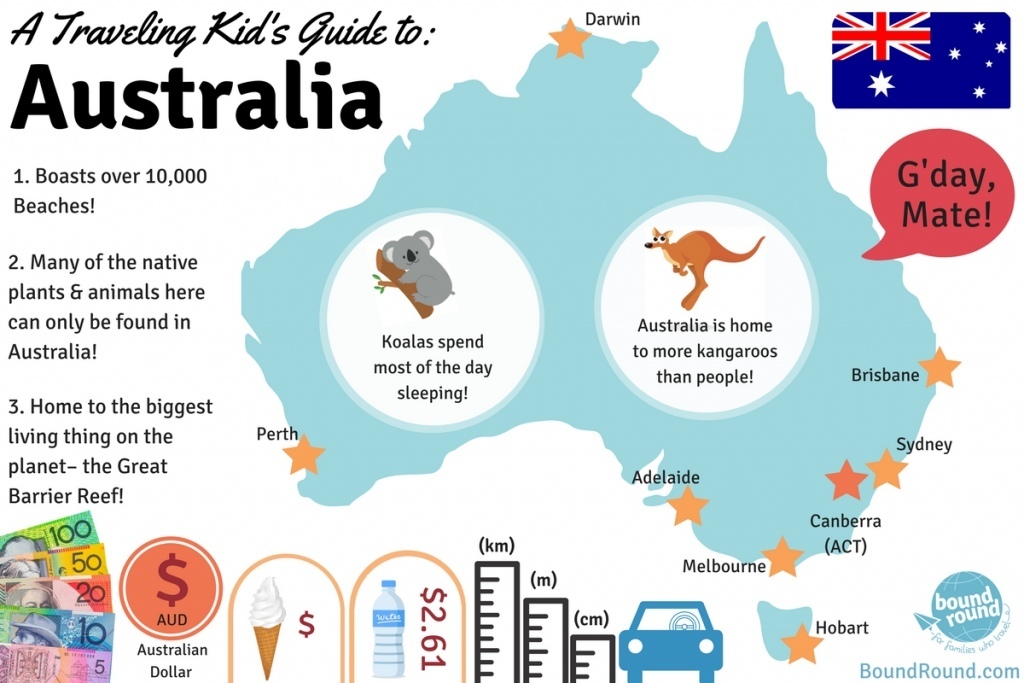

How much does it cost to raise children in Australia?

We’re reader-supported and may be paid when you visit links to partner sites. We don’t compare all products in the market, but we’re working on it!

Having children is a life-changing and joyous experience for most parents, but it also comes with added expenses that can push the budgets of even the savviest savers.

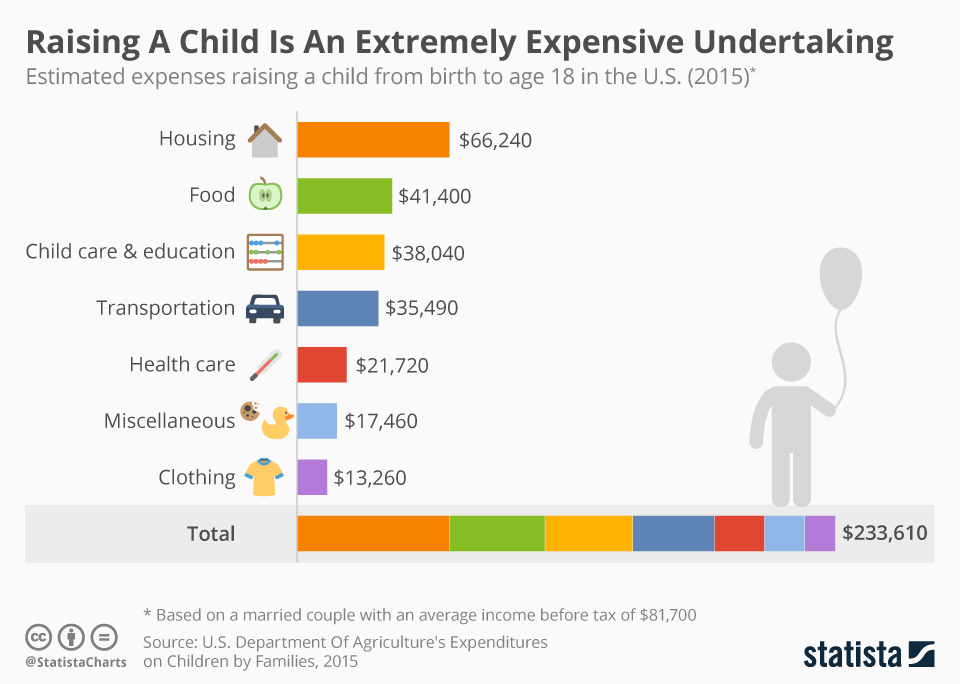

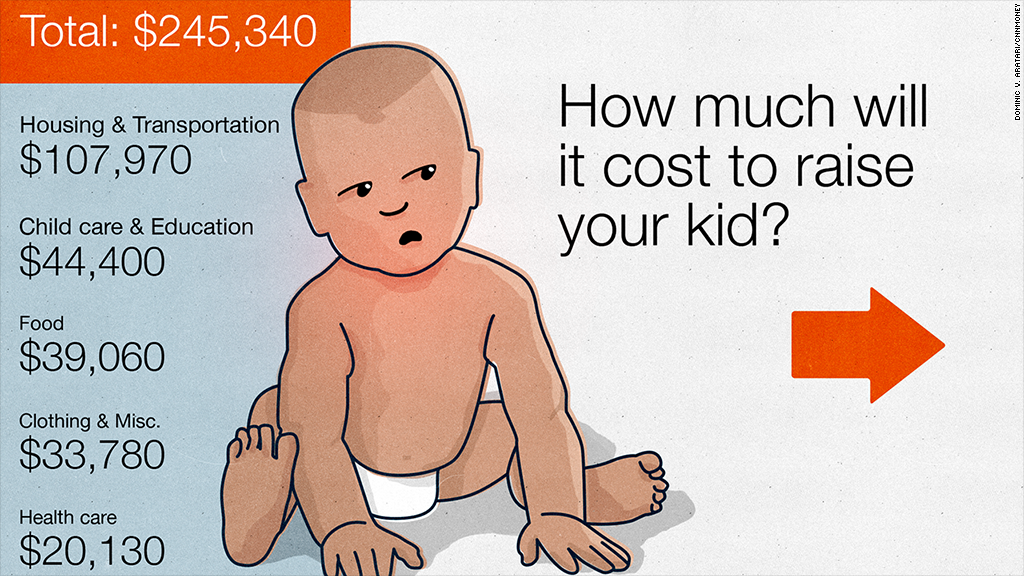

A 2018 government study shows that parents at a bare minimum can still expect to spend around $140–$170 a week to raise a child. However, it's not unusual for this figure to be far higher for most parents and guardians.

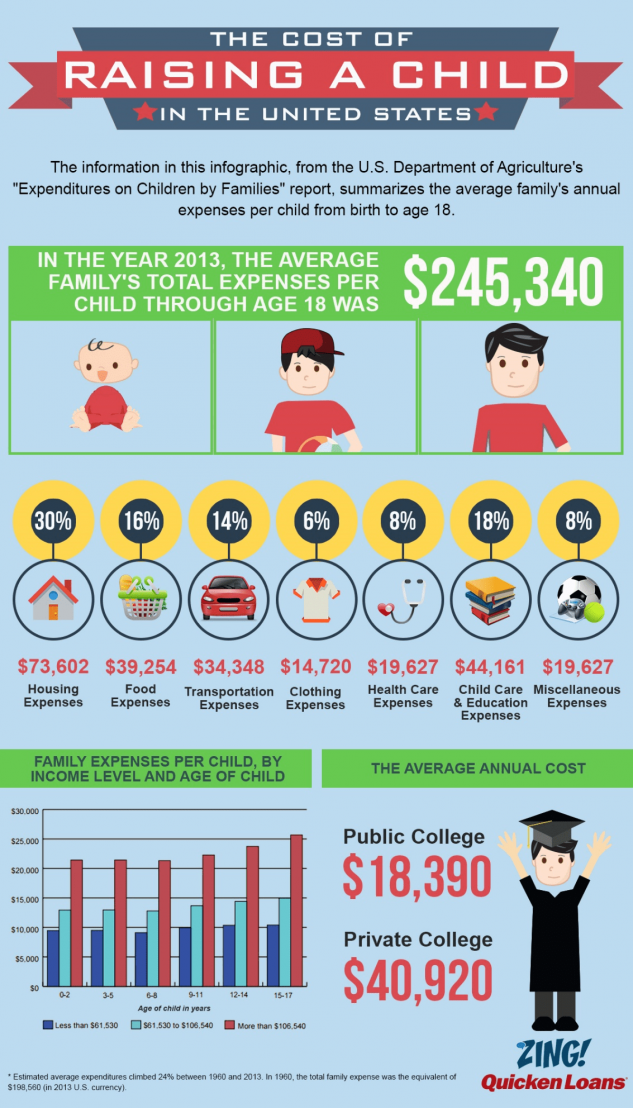

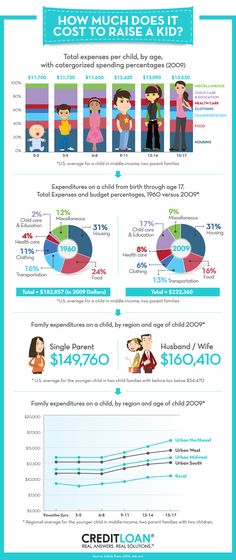

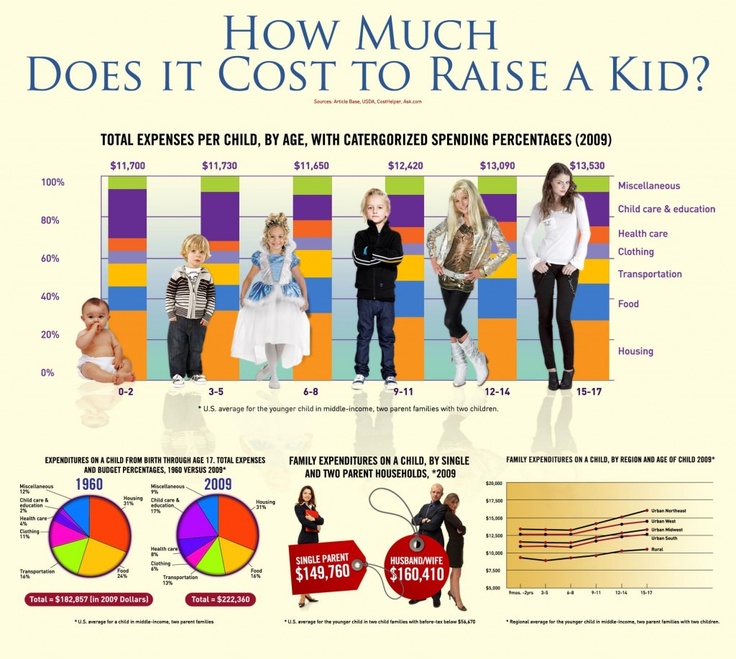

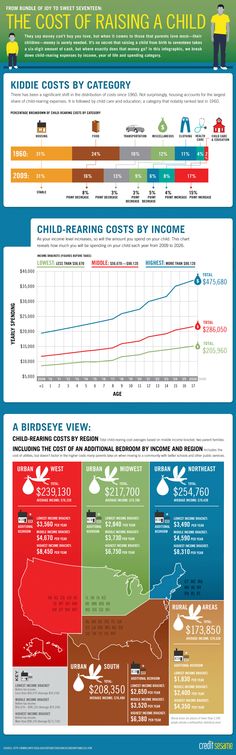

There are a few different answers to that. We looked at a couple of studies and found the estimates ranged from $159,120 to $548,500 over 18 years.

A 2018 research by the Australian Institute of Family Studies shows that it costs low-paid families $340 a week to raise 2 children, a 6-year-old girl and a 10-year-old boy, which is roughly $170 per child. That's $8,840 every year or $159,120 for 18 years per child.

For unemployed families, the cost of raising 2 children of the same ages was $280 a week or roughly $140 per child. That's $7,280 every year or $131,040 for 18 years. Again, per child.

However, a 2013 report by the University of Canberra came up with completely different figures.

The earlier study created profiles for 3 different families: lower income, middle income and higher income. It found that the cost of raising 2 children would likely range from $474,000 to $1,097,000 over the course of their childhood.

For 1 child, that's an estimate of $13,166 to $30,472 every year or $237,000 to $548,500 over 18 years.

In late 2021, Suncorp Bank revealed the costs of raising a child in Australia in its Cost of Kids report. The research surveyed a representative sample of Australians and targeted parents.

The report found that the cost of raising a child increased by more than 10% in the past five years. Communication devices and technology are the single biggest expenses since the previous report in 2016. Parents now spend 186% more on keeping their children connected each month, with a cost of $106 per child spent on computers, gaming consoles and mobile phones.

| Childcare | $68 | $122 |

| Clothing | $85 | $140 |

| Communications, connectivity and technology | $37 | $106 |

| Educational costs | $130 | $386 |

| Extracurricular activities | $44 | $140 |

| Entertainment, leisure and social activities | $43 | $133 |

| Food | $250 | $402 |

| Furnishings and equipment | $23 | $118 |

| Health care | $92 | $112 |

| Holidays | $47 | $97 |

| Housing | $421 | $321 |

| Insurance | $31 | $70 |

| Personal care products and services | $73 | $96 |

| Pocket money | $24 | $59 |

| Savings and contingencies | $39 | $318 |

| Transport | $98 | $232 |

| Tutoring | $20 | $58 |

| Utilities | $98 | $134 |

If you understand the cost of raising a child, you can make important decisions in advance. You can start saving, create a support network, develop a budget and find affordable housing.

You can start saving, create a support network, develop a budget and find affordable housing.

Anne Hollonds is the director of the Australian Institute of Family Studies. She said the cost of raising a child has long been of interest to potential parents, adding:

"Families are interested because the cost of raising children affects their wellbeing and the decisions they make about managing the burden of care."

Understanding the potential cost of having kids also allows you to put an appropriate financial safety net in place. For example, life insurance or income protection insurance, which guarantee a wage if you become too sick or injured to work.

Insurance can give your family an important safety net in case anything goes wrong. If you die or become too sick to work, life insurance and income protection mean the difference between falling behind on the mortgage or having enough money to pay for the best healthcare. Here's a summary of how they can help:

- Life insurance pays a lump sum if you're diagnosed with a terminal illness or if you die.

The money can be used for whatever your loved ones like, whether that's paying off the mortgage, covering school fees or just keeping on top of everyday expenses.

The money can be used for whatever your loved ones like, whether that's paying off the mortgage, covering school fees or just keeping on top of everyday expenses.

- Income protection insurance replaces up to 75% of your regular wage if you ever become too sick or injured to work. Again, you can use it for whatever you like but it means you can focus on getting better rather than worrying about paying the bills.

We've put together a list of all the life insurance and income protection providers available on Finder. Click through for a personalised life or income protection quote. Not sure which one you need? Our life insurance vs income protection guide can help.

- Life insurance

- Income protection

| Name | Product | Maximum Cover | Average Claims Acceptance Rate | Average Claim Time | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

TAL Life Insurance | $2,000,000 | 74 | $2,000,000 | 87. | 2.9 months APRA's June 2021 stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | $36,630 million APRA's most recent underwriter stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | Finder verifies that TAL has more Australian lives insured than any other provider - for 3 years in a row. Plus, get up to 15% off with TAL’s Health Sense program. | Compare | ||

$15,000,000 | 69 | $15,000,000 | 98.1%APRA's June 2021 stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | 1. | $20,230 million APRA's most recent underwriter stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | Get your first month free when you buy NobleOak Life Insurance policy. Offer ends 30 November 2022. T&C's apply. | Compare | |||

Medibank Life Insurance | $2,500,000 | 70 | $2,500,000 | 87.30%APRA's June 2021 stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | 3.8 months APRA's June 2021 stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | $31,745 million APRA's most recent underwriter stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | 24/7 nurse phone support + Medibank health members will save 10% on premiums every year. | Compare | ||

ahm Life Insurance | $1,500,000 | 65 | $1,500,000 | 87.20%APRA's June 2021 stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | 3.8 months APRA's June 2021 stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | $31,745 million APRA's most recent underwriter stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | Get life cover up to $1,500,000. Plus, ahm health members can save 10% off premiums. | Compare | ||

RAC Life Insurance (Only available in Western Australia) | $25,000,000 | 69 | $25,000,000 | 98.10%APRA's June 2021 stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | 1.1 months APRA's June 2021 stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | $20,230 million APRA's most recent underwriter stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | When you purchase RAC Life Insurance, WA residents receive complimentary RAC membership which includes access to discounts on fuel, savings on shopping, entertainment and more. T&Cs at rac.com.au. | Compare | ||

Real Family Life Cover | $1,000,000 | 64 | $1,000,000 | 90.20%APRA's June 2021 stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | 1.8 months APRA's June 2021 stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | $53,462 million APRA's most recent underwriter stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | Get a refund of 10% of the premiums you've paid (in the first 12 months) with The Real Reward™. | Compare | ||

Zurich Ezicover Life Insurance | $1,500,000 | 69 | $1,500,000 | Data not available | Data not available | $12,444 million APRA's most recent underwriter stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | Get your first month free and a 10% discount by taking out a second life insurance policy (discount applies to the second policy). | Compare | ||

RACQ Life Insurance | $1,000,000 | 65 | $1,000,000 | 97%APRA's June 2021 stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> | Data not available | Data not available | View details | Compare |

loading

1 - 5 of 6

Data from Care for Kids show that the average cost of childcare in Australia is $119.40 a day, before subsidies. That's easily going to be the most expensive outgoing for lots of parents.

However, the price can vary significantly depending on where you are. In Sydney city centre, the average daily price jumped to $171.13 while Melbourne was $152.23 and Brisbane was $137.98. The costs in Perth are $151.50 and $119.25 in Adelaide.

In Sydney city centre, the average daily price jumped to $171.13 while Melbourne was $152.23 and Brisbane was $137.98. The costs in Perth are $151.50 and $119.25 in Adelaide.

Head further out and childcare becomes less expensive. New South Wales' Blacktown reported an average daily price of $101.89 while Victoria's Dandenong was $106.45 and Queensland's LoganBunderberg was $92.15

To put the cost of childcare into perspective, an average-earning Australian couple with 2 young children is likely to spend around 20% of their income on full-time childcare costs based on data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Thankfully, government benefits are available. Check the Australian government's Family Assistance Guide to see which ones apply to you.

Figures taken on 23 June 2022 from Care For Kids child care cost calculator.

Data from the Futurity Investment Group shows that parents can expect to spend an average of $83,869 to send a child starting school in 2022 to a metropolitan state school.

Of course, that price balloons if they decide to send their child to a private school. In that case, they can expect to spend a whopping $349,404 on their child's education.

Costs vary considerably depending on which state your child goes to school in as well. Brisbane takes the crown for Australia's most expensive Catholic education, while Sydney is in the lead for the highest Government and Independent education. Perth is the nation's most affordable city for an Independent education.

| Sydney | $92,375 | $132,048 | $459,236 |

| NSW (regional and remote) | $59,683 | $117,476 | $137,268 |

| Brisbane | $74,988 | $158,199 | $273,280 |

| QLD (regional and remote) | $78,503 | $121,648 | $164,142 |

| Adelaide | $85,773 | $141,274 | $284,690 |

| SA (regional and remote) | $71,478 | $106,821 | $142,357 |

| Melbourne | $88,906 | $146,496 | $403,373 |

| VIC (regional and remote) | $59,162 | $108,182 | $213,232 |

| Perth | $76,229 | $140,387 | $215,554 |

| WA (regional and remote) | $74,645 | $110,054 | $154,213 |

Source: The Futurity Investment Group Planning for Education Index

It's easy to spend more than the government's estimated figure on raising your child especially if you don't fall into the unemployed or low-paid category.

In 2019, women's media platform Mamamia asked 11 families to analyse their weekly spending per child. The figures ranged from a frugal $152 all the way to an eye-watering $863.

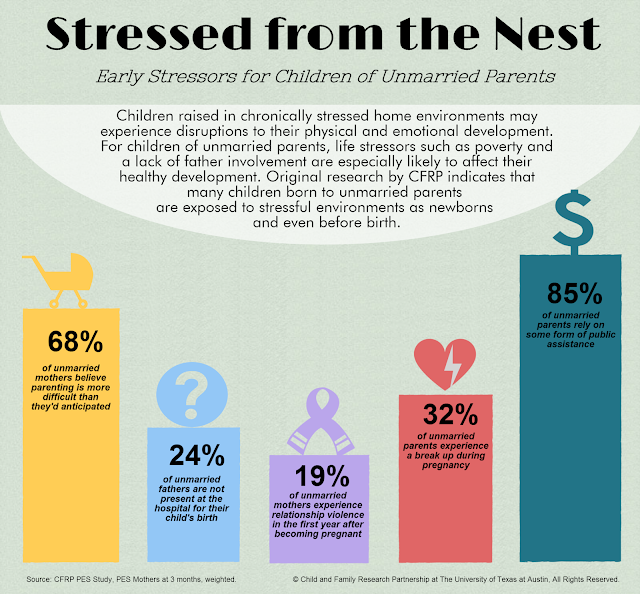

You also have to take into account the economic impact of taking time off work – either for parental leave, to raise your children for a few years or even just turning down overtime hours.

A 2014 report by the Australian Human Rights Commission found that 49% of the mothers and 27% of the fathers reported experiencing discrimination in the workplace during pregnancy, parental leave or on return to work.

The same report found that 18% of mothers felt they were either dismissed, made redundant or moved elsewhere due to their pregnancy, parental leave or family responsibilities or breastfeeding requirements.

Of course, money isn't the only thing you'll have to part with if you decide to have children. Social engagements, spare time and even career ambitions can all be impacted.

Finder surveyed over 1,000 parents in 2021 and found that one big impact on parents is how much time they spend driving their children around. Parents spend 3.5 hours per week on average driving their kids to school and other activities.

Parents spend 3.5 hours per week on average driving their kids to school and other activities.

You might also have to make some changes to your career once you have kids. 29% of survey respondents switched to part-time eployment after giving birth.

We also spoke with 3 mums who shared their personal sacrifices as they became parents.

"We have chosen to put lavish family holidays on hold and enjoy trips in our caravan with friends so that we can pay for private school education at $100 a day per child."

- Leisa Papa, founder of Little Kids Business

"Having dependants to care for has made us look far into the future and be responsible with our spending. We travel less, dine out less frequently and even find more joy in finding bargains from Kmart than shopping in the branded outlets."

- Natalie Chan, CEO of Motherpedia

"With kids, then time for your partner and time for work/business, you find that it is very hard to have alone time. Something that was once so easy is a mammoth effort of organising and a payoff between do I work, spend time with somebody else or give myself time for me?"

- Raeleen Kaesehagen, CEO and founder of Mudputty

You pay the same as buying directly from the life insurer. Better still, we regularly run exclusive deals that you won't find on any other site – plus, our tables make it easy to compare policies.

Better still, we regularly run exclusive deals that you won't find on any other site – plus, our tables make it easy to compare policies.

Our team of life insurance experts have researched and rated dozens of policies as part of our Finder Awards and published 350+ guides to make it easier for you to compare.

Unlike other comparison sites, we're not owned by an insurer. That means our opinions are our own and we work with lots of life insurance brands, making it easier for you to find a good deal.

Since 2016, we've helped 270,000+ people find life insurance by explaining your cover options, simply and clearly. We'll never ask for your number or email. We're here to help you make a decision.

New estimates of the costs of raising children in Australia

The figures - published today by the Australian Institute of Family Studies’ - show the weekly costs of raising a child range from $140 for unemployed families and $170 for low-paid families.

Institute Director, Anne Hollonds said the costs of bringing up children are of intense interest to both families and policy makers.

“Families are interested because the cost of raising children affects their wellbeing and the decisions they make about managing the burden of care, and policy makers need robust information to inform family policies, including the adequacy of minimum incomes,” Ms Hollonds said.

The research was carried out by the UNSW Social Policy Research Centre using a ‘budget standards’ approach to estimate the cost of children’s food, clothing and footwear, health, personal care and school expenses and their share of household expenses like housing, household goods and services (including energy) and transport costs.

Professor Peter Saunders said that the budget standards approach identifies and then costs all of the items that are needed to achieve a ‘minimum income standard for healthy living’ in Australia today.

“We updated the existing budget standards using new ABS data on what Australians own, what they do and what they spend their money on,” he said.

“For example, we included the costs of mobile phones which are now commonplace and what it costs to feed and clothe children by pricing shelf items in nationwide stores, such as Woolworths and Kmart.

“A series of focus group interviews with low-income families told us how they manage on their budgets which turned up important trends, including clothes swapping for school uniforms and buying more home-brand or generic items in supermarkets and chain stores.”

The study found the estimated weekly costs for low-paid families of raising two children – a 6 year-old girl and a 10 year-old boy – is $340 per week, or $170 a week per child. While at the lower unemployed standard, the weekly costs of raising two children is $280 per week, or $140 a week per child.

The most expensive budget items were housing costs, based on families paying average prices for rental accommodation in Sydney, Melbourne or Brisbane, followed by food, household goods and services.

Other, shared costs include the additional energy bills required to keep the home adequately warm and transport costs associated with ferrying children to school and activities.

“The new estimates of the cost of children are considerably higher than those produced by updating the original budget standards created in 1995 because prevailing community standards have shifted upwards over the past two decades,” Professor Saunders said.

“A key advantage of the budget standards approach is that it makes transparent the key decisions, choices and assumptions required to estimate how much is needed to achieve the minimum healthy living standard, consistent with adequate levels of social participation and inclusion.”

“The results provide important data for assessing how much income unemployed and low-paid families need and can thus guide the setting of the Newstart Allowance and the minimum wage.”

| Budget category | Family type: | Costs of child(ren): | ||||

| Couple, 0 children (1) | Couple, 1 child (2) | Couple, 2 children (3) | 6-year-old girl (2) minus (1) | 10-year-old boy (3) minus (2) | Combined cost of G6 and B10 (3) minus (1) | |

| Food | 123. 60 60 | 156.22 | 200.91 | 32.62 | 44.69 | 77.31 |

| Clothing and footwear | 15.77 | 23.72 | 33.20 | 7.95 | 9.48 | 17.43 |

| Household goods and services | 99.59 | 112.72 | 139.10 | 13.13 | 26.38 | 39.51 |

| Transport | 120.75 | 144.72 | 144.72 | 23.97 | 0.00 | 23.97 |

| Health | 14.45 | 19.51 | 24.36 | 5.06 | 4.85 | 9.91 |

| Personal care | 27.04 | 31.03 | 35.34 | 3.99 | 4.31 | 8.30 |

| Recreation | 39.54 | 62.06 | 76.99 | 22.52 | 14.93 | 37.45 |

| Education | 0.00 | 27.43 | 61.26 | 27.43 | 33.83 | 61.26 |

| Housing (Rent) | 392.50 | 392.50 | 457.50 | 0.00 | 65.00 | 65.00 |

| Total budget | 833. 24 24 | 969.91 | 1,173.38 | 136.67 | 203.47 | 340.14 |

The article will be published in the forthcoming issue of Family Matters, the Institute’s journal that publishes research relevant to contemporary Australian families. You can access the article, New estimates of the costs of children by Peter Saunders and Megan Bedford in the Related publications section below.

More information about the project is also available on the University of New South Wales (UNSW) Sydney webpage (link in Related publications section below): Budget Standards: A new healthy living minimum income standard for low-paid and unemployed Australians.

"To be, to belong, to become": how children are brought up in Australia

TravelHistory

People fled to Australia in the 18th century for this freedom, but now they come here for it. And the children who were lucky enough to be born here are used to deciding everything themselves.

- Photo

- Natasha Lesonie

HEROINE

Elena Stepanova*

Born in Moscow in 1983. In 2006 she graduated from the Russian State Trade and Economic University. She worked at Procter & Gamble in Moscow, where she met her future husband Dmitry.

In 2011 the Stepanov family moved to Sydney. During her maternity leave, Elena founded Gem Studio Photography , which specializes in photography of weddings and family events. Elena and Dmitry are raising three children: Anton (9 years old), Maya (8 years old) and Yana (3 years old).

* Elena told Around the World about her life in Australia and about the peculiarities of raising children in this country in 2017. - Intelligence in the face of the youngest daughter reported that they have three boys. Then my son Anton went to play with them and said that there were actually five boys. And the other day, a neighbor's dog ran into our site, I took it to the owners, met them and was surprised to find out that there were eight boys. The eldest is 18 years old, the others are 15, 12, 8, 6, 4, 2 years old and the youngest is 8 months old.

And the other day, a neighbor's dog ran into our site, I took it to the owners, met them and was surprised to find out that there were eight boys. The eldest is 18 years old, the others are 15, 12, 8, 6, 4, 2 years old and the youngest is 8 months old.

In the North Beaches area of Sydney, where good schools are concentrated, almost all families have many children. Few have less than three. Australian women give birth to their first child after 30. And often they do not even wait two years to give their first child a brother or sister. The weather here is business as usual. Moms are easy to manage with a whole gang.

Barefoot childhood

As soon as you find yourself in the area of Forestville , where Elena's family lives, you get the feeling that you have arrived at the dacha: under the purple vaults of blooming jacaranda, children run squealing in the same swimming trunks and pouring water on each other from watering cans.

- Anton, Maya and Yana are now playing at the neighbors'. There are three kids around the same age. Children rush back and forth all day long: they jump on our trampoline, then they run to the neighbors on the trampoline. Swim in their pool and race to dive into ours. Children often run barefoot down the street, even in the city. Heat.

There are three kids around the same age. Children rush back and forth all day long: they jump on our trampoline, then they run to the neighbors on the trampoline. Swim in their pool and race to dive into ours. Children often run barefoot down the street, even in the city. Heat.

- And in general, here no one cares, as we do in Russia, about many things - for example, handrails in public transport that you have to hold on to, or puddles that you can’t run across. It is believed that if a child at a certain age crawls on the floor or lawn and puts everything in his mouth, then this is normal for his immunity, says Elena.

- As soon as we moved to Sydney from Moscow, my husband and I immediately liked being relaxed Australian parents. The habit of wrapping up children and protecting them from dirt evaporated in the very first autumn. I calmly watch how mine sit right on the asphalt - to have a bite or play. But how to forbid if everyone around - both adults and children - are sitting on the ground?

- Now we have winter already - June, July and August are the coldest months in Australia. We sleep with heaters. The floor is ice cold. From the end of May until September, we adults wear ugg boots at home. Children are not. Maya is ready to run barefoot all year round. I let. This is her choice. My daughter never missed school in a year. And at home she was constantly sick.

We sleep with heaters. The floor is ice cold. From the end of May until September, we adults wear ugg boots at home. Children are not. Maya is ready to run barefoot all year round. I let. This is her choice. My daughter never missed school in a year. And at home she was constantly sick.

The only piece of clothing you can't live without in Australia is a headdress. To protect children from the scorching sun in kindergartens and playgrounds, rule No hat, no play (“No hat - no play”) applies. A wide-brimmed cowboy hat is part of the school uniform.

Everything else - according to command take it easy (keep calm). Walking barefoot into a coffee shop on the way from the beach or running home in a bathing suit is nothing special. Australians give children complete freedom of choice - both clothing and life path.

Freedom for the parrots

In May, at the beginning of the school year, at a meeting in elementary school, teachers tell parents about the generally accepted concept of education.

All Australian pedagogy is reduced to the rule of three B : being, belonging, becoming , which means “to be, belong, become”. These three B define the core values of Australian life.

“Children learn the rules of behavior through encouragement,” Mrs. Wilson, Anton's teacher, told me. Here it is customary not to focus on the negative, but, on the contrary, to intensely praise the child if he did something well, - says Elena.

— Twice a year, at a meeting with a teacher, I listen for half an hour to what wonderful children I have: assiduous, creative, talented, kind, artistic. In elementary school, children, of course, are taught to read and write, to do homework. But still give them the opportunity to grow and develop at their own pace.

— The tasks are simple: ride a bike for 30 minutes, ask dad how you are, help mom cook dinner, read a small book, write down and colorfully arrange a recipe.

The first of the three Bs, being, means to live here and now. That is, children should explore the world and enjoy their childhood, and not pore over the lessons.

That is, children should explore the world and enjoy their childhood, and not pore over the lessons.

- It is better for a child to spend several hours on the street chasing bright parrots than to sit over textbooks. We have nine months of heat a year, children grow up outside. They didn’t hear about the early development of the mother here at all. There is no panic if the child starts talking after two years. Or at five he can't put two and two together.

- No one bothers children with educational cards, cubes and pyramids. My neighbors say that teaching children is the job of teachers. I really like the motto on the poster hanging at our school: Childhood is a journey not a race

The race starts a little later, after graduation from school in the sixth grade, when the child has to choose where he will study next. From 7th to 12th grade, children attend secondary school.

There are several options - a prestigious and expensive private, paid Catholic or selective school, where you need to take an entrance exam, or a public free district school.

— Recently, at dinner, our boy announced to us that, they say, you parents can discuss the best schools and tutors in the city as much as you like, and I will go to our district school with friends.

- Anton wants to be a simple worker and drive a ute (pickup) with a toolbox. We dreamed that he entered a selective French school. Maybe he'll change his mind? The decision is his.

All for One

A child's place of education is the second most popular topic after the weather in local culture small talk (small talk). Australians are known for their affability and friendliness. They don't mind talking.

Starting a conversation with a stranger on the street is as easy as at the office cooler. It is enough to ask: “Where will yours go to study?”

- For Australians, success in life is measured by the school their children attend. And it's not about the quality of education. It is believed that the social circle that the child acquires is much more important, - says Elena.

Second B - belonging - means belonging to a particular society. Parents are ready to go to great lengths to give their child a good start in the form of an elite school: for example, to sell their house and move to another area.

And if a district school is taken on a geographic basis, then you can get into a private school only by signing up for a waiting list almost immediately after the birth of a child.

- Anton's best friend Will Ferguson will go to the prestigious St Josephs at Hunters Hill for boys, which his dad Scott once graduated from. At a neighbor's barbecue, Scott said with a laugh that his son's expensive education would hardly be any different from the one ours would receive in a free school.

- But the line indicating the elite educational institution in the child's personal file, according to the father, will open up more opportunities for him.

In order to be happy and self-confident, the child must feel belonging to the family, the street, the community, the circle of friends and, ultimately, to his country. Neighbors are very close-knit.

Neighbors are very close-knit.

Australians like to do everything together, in big groups. Here, from early childhood, they are taught to make friends, take care of others, and spend time with their families.

— I often feel like a mother of many children: I take for a walk not only my own, but also my neighbor's children. After school on Mondays we have swimming practice. The day before, a neighbor calls and asks to look after her boys, whom she does not have time to pick up from school. Five children can easily fit in my car, I take everyone to the pool.

- And in the evening Maya's girlfriend comes to us at sleep over - children often spend the night with friends. Good neighborly mutual assistance is a common thing.

- Once I got stuck at work. Our nanny calls me and says that her car has a flat tire, there are three children in the car, it is raining outside, and the rescue service will not be here until an hour later.

— In desperation, I describe the situation on a social network, and within five minutes three of our neighbors express their readiness to go pick up the children in their cars… They also cooked dinner at my house while I was getting there, — Elena recalls.

Australia is known for its strong social support system for children, families and working mothers, but it often seems that children are taken care of not so much by the state as by the society itself. The fact that the country does not even have the concept of “orphanage” speaks volumes.

— Yana's youngest daughter has a friend Levi. The kid is two and a half years old, he has been raised by trustees for more than a year. This family raised several kids who got into a difficult life situation. All the children lived with them for 8–10 months a year, and Livay was adopted,” says Elena.

- Everyone in this country is ready to help someone else's child. Caring is shown even in small things. Example: on our street there is a family of pensioners who are already over 70. They do not have their own children. Pam, the neighbor, goes to my children's school for grandparents, looks at crafts, talks to the teachers. We have no relatives in Australia. Pam helps us out so the kids don't feel left out at school.

However, in an Australian school it is difficult to feel deprived or superfluous.

STATISTICS

Adults and children

31 is the average age of a mother at birth in Australia. This is one of the highest rates in the world.

Infant mortality rate* - 3.01

(Japan - 1.90 ; USA - 5.17 ; Russia - 6.42 ; India - 30144).

22% of Australian children are in the care of grandparents, 14% go to kindergarten, 7.8% stay in day care after kindergarten and school, 2.5% attend family-type kindergartens.

One day of kindergarten costs AUD 150-170, half of which is covered by the government.

Babysitting costs AUD 20-30 per hour.

64% of girls and 61% of boys aged 15 to 24 are studying.

80% of people with higher education are employed.

* Number of deaths of children under the age of one year per 1000 live births (according to the CIA)

A place under the Sun

No one will tease a child who is somehow different from other students. Bullying - bullying of any kind - is immediately stopped at school. The classes are mixed every year. Tolerant Australian children, when talking about a newcomer to their parents, will not describe his skin color or physical features.

Bullying - bullying of any kind - is immediately stopped at school. The classes are mixed every year. Tolerant Australian children, when talking about a newcomer to their parents, will not describe his skin color or physical features.

— Once a new student was transferred to Anton's class. The son described him as "a strong boy in blue jeans". Seeing this child for the first time, I was very surprised - it would be more accurate to describe him as fat.

Whatever you are and whoever you become, society will not judge you. Explaining the meaning of the third B from the list - becoming - teachers say that many circumstances and events influence the formation of each person.

The school library has an entire section dedicated to books for the little ones from the My first look at series. There are picture books here with frightening titles, My Mom Has Cancer, My Pet Died. The essence of difficult situations is explained to children in an accessible language. One of the books, for example, talks about why some children have two dads or two moms.

One of the books, for example, talks about why some children have two dads or two moms.

Families with children definitely go out into the countryside on weekends — hiking in the bush, on the ocean, on a picnic, on a bike trip, in winter they go skiing. One of the leisure activities is to live on a farm.

- There are farms where several families coexist in one large religious community. We somehow went there for the weekend to show the children that people can live in different ways, but no one will look askance at them,” says Elena.

Children talk about past weekends and holidays in kindergarten and school. Kids easily get up in front of the whole group and perform. In elementary school, where they start going from the age of three, oratory is taught.

Already in the second grade they organize public speaking competitions. First, the best speaker from the class is chosen, then from among parallel classes, as a result, the winner must make a speech in front of the whole school.

- Children in front of a large audience make presentations on a certain topic, like real speakers. At these competitions, every time I am amazed at their abilities and once again I understand why the Australians are so relaxed and free: they are sure from childhood that everyone in this country will be carefully listened to and not judged. Therefore, people here are not afraid to express their opinion and do what they really like.

By the way, Australia is one of the most prosperous countries in the world. According to a comprehensive study by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), it ranks second in the world (after Norway) in the Better Life Index.

REVERSE

No family

May 26 is National Repentance Day in Australia. Commemorative ceremonies are held across the country to honor Aboriginal children forcibly separated from their families.

Between 1910 and 1970, the government separated tens of thousands of children from their parents in order to raise them in the spirit of Australian society. In 2008, the country's prime minister, Kevin Rudd, apologized to the indigenous population, acknowledging that "profound grief, suffering and loss" had been inflicted on an entire generation.

In 2008, the country's prime minister, Kevin Rudd, apologized to the indigenous population, acknowledging that "profound grief, suffering and loss" had been inflicted on an entire generation.

Some of the natives managed to obtain moral and financial compensation. Today, Indigenous Australians make up about 3% of the population. In terms of the prevalence of alcoholism, unemployment rates, the number of suicides and cases of domestic violence, they are far ahead of the rest of the inhabitants of Australia, and in terms of life expectancy they lag behind them by 10 years.

Photo: Elena Stepanova, Alamy / Legion-Media, Getty Images, iStock, HEMIS / Legion-media

Material published in Vokrug Sveta No. 6, June 2017, partially updated in August 2022

Daria Karelina

Tags

- children

- education

7 Australia | RefNews

Rethinking contemporary and historical adoption experiences will help thousands of children in foster care, says a new report from Australian experts.

Australia is known as the Land of the Lucky, but the almost 40,000 children in orphanages waiting for a permanent home with loving parents and the many spouses who want to adopt a child are hardly lucky.

Adoptions in Australia have declined by a staggering 97% over the past 40 years, from nearly 10,000 adoptions in 1971-72 to to just 339 in 2012-13, with almost a third of them made overseas. Other countries also experienced a decline in adoptions, albeit not much compared to Australia.

Are we really taking better care of children in need? Or is the fact that a large number of them are in shelters a sign that we have preferred ideological and bureaucratic concerns to their interests? A new report from the Australian Women's Forum "Adoption Rethink" shows that the latter is closer to the truth.

The report examines the decline in adoptions from various perspectives, including the current rise in legal abortions, feminist theory and media coverage. It tracks how this practice, once seen as a natural and obvious solution to the needs of children who are unable to be raised by their own parents, has fallen out of favor in recent decades, and how it affects the growing number of children being raised outside the family.

Closed adoptions, stolen generations

At the forefront of this recent story are women who abandoned their children at birth in a time when single mothers were viewed with disapproval. Sometimes these women were under pressure to give up babies without knowing the adoptive parents or expecting to ever see their child again. These women speak of their grief and the wound they have received. Already grown children, who were adopted / adopted under the same “closed” regime, also complained about their painful “quest” to find their biological parents, their full identity. Studies conducted among such people revealed a high level of mental disorders in them.

Historical errors that lead us to speak of the Stolen Generations (separating Aboriginal children from their families), lost innocents (the "export" of 7,000 children from the UK in the early 20th century) and Lost Australians (hundreds of thousands of Australians who spent their childhoods in orphanages) have also contributed to the bleak notion of adoption over the past ten years.

At the same time, the population of children who could benefit from adoption has also changed. Early 19In the 1970s, at least half of the adoptions involved the children of young unmarried women. They, themselves almost children, were encouraged, even forced to give away a child they could not raise alone, and instead encouraged to strive to complete their education, find a job and get married. Now those norms have changed with benefits, abortions and birth control pills.

Is another lost generation on the way?

Today's picture is very different from the past. Most children in Australia (and similar countries) in need of foster parents have been taken from their biological parents due to physical, sexual or emotional abuse, neglect, and placed in foster homes. The number of these children has doubled over the past decade, however, despite this, it takes an average of four years to adopt a child into a foster family.

At a time when dramas about foreign adoptions fill the pages of magazines and newspapers, the uncertain future of these children is a growing scandal that calls for urgent action.

Rethinking Adoption reports that of 39,621 children in foster care in mid-2012, two out of three were in a state of permanent family-to-family transfer for two or more years, with an increasing number of children continually returning to the system . “Thus, children in foster care live in a state of more frequent change and instability, which leads to more complex needs and behaviors.”

Becky Hope, in her book All In a Day's Work, cited in the report, emphasizes the critical importance of stable, loving care during the earliest periods of a child's life:

who do not get their basic needs met in reciprocal, loving care, and who are forced to scramble through life on their own, suffer visible devastating effects of brain development even before they are a year old.

It has also been found that children who experience severe lack of parental attention as infants and are placed in long-term foster care before six months of age are able to generally make more progress than if they are adopted after six months.

Children need stability to form secure attachments, but guardianship, no matter how well it is done, is temporary in nature. While there has been an increase in permanent guardianship cases in Australia (and similar instruments elsewhere), a recent study in Queensland found that such arrangements "do not provide enough stability for children". On the one hand, the rights of guardians can be challenged by the family of origin, on the other hand, they do not give children the same sense of belonging to the family, unlike adoption.

Gregory Pike, director of the Center for Bioethics and Culture in Adelaide, also comments on this situation in the report “Rethinking Adoption”: adoptions. The cost to society and government of caring for these children and treating the traumatic consequences of their situation is enormous.

Adoption: open and closed

(Ed. With a closed adoption, the adoptive family can keep the fact that the child is not a parent, with an open adoption is not a priority)

In Australia in 2011-12, 95% of local adoptions were open - this is a continuing upward trend that has covered 80% of adoptions since 1998.

Although some adoptions did not really take into account the needs of the birth mothers (fathers were usually not in this picture at all) and the child, in the age of open adoptions, every effort is made to respect the rights and feelings of all participants in the “adoption triangle” . In any case, it is the adoptive parents who now suffer their own stigma for being on a side with a dark history, which has negatively impacted a significant number of people.

There is a tendency to exaggerate this influence.

Dr. Pike reviewed local and international reports on adoption outcomes for biological mothers, adopted children and parents, including those who belonged to the "closed" age. The literature provides a much more detailed picture than is evident from media reports of people who have gone through negative or unhappy experiences.

Undoubtedly, some mothers who were forced to give up children suffered, but “a significant amount of uncertainty exists about how common these outcomes were and how they relate to the characteristics of adoption and its process,” Pike says.

There is evidence that finding and reuniting with a child has a healing effect.

There is evidence that finding and reuniting with a child has a healing effect. Looking at the problems of adopted children, he found the following: Although adopted children represent the largest proportion of patients with mental disorders, the actual proportion of "adoptees" in a society with such problems is very small. Foster children face significant challenges in addition to those typically experienced by children in early childhood and adolescence, however, there is evidence that foster children have incredible resilience and there is official evidence of their ability to "catch up" on various occasions. For some adopted children, their experiences prior to adoption were often difficult and sometimes traumatic, and these experiences were associated with later outcomes. When compared with their peers who remained in the shelters, the "adoptees" had better physical and mental health and better circumstances in education and socialization. The key issues for adopted children were attachment, self-determination, search and recovery.

Little research has been done on foster parents and their problems.

Intercountry adoption

Despite the bad reputation and availability of reproductive technology, it appears that many couples would be happy to adopt if given the option. Frustrated by the barriers to adoption in Australia, they often turn to orphanages in developing countries. Here again they have to wait up to five years.

Obviously, special care must be taken to ensure that the adoption of a child in another country and culture serves his best interests. Pike says: “In the case of all adoptions, and according to the Hague Convention on Adoption, cross-country adoption should be used only in cases where the biological parents (parent) or relatives do not have the ability or desire to properly care for the child. Only if there are no suitable facilities available to provide ongoing care in the State where the child was born, should ethical inter-country adoption be considered in the best interests of the child.

”

” Tony Abbot's government in Australia has taken steps to expedite these adoptions by creating a new national agency that will be operational by mid-2015 to negotiate adoptions with most countries.

However, each country has its own special obligations to its children, and those under the care of the state deserve a new plan. Barnados Australia, a leading non-governmental agency for the protection of child survivors of abuse, urges Abbott to set a goal for open adoptions in every state.

So why delay?

According to a report by Martin Nary, UK Government Adoption Adviser, important factors include: take him to meetings with his parent or parents while the court decides the future of the child. This represents a shocking mistake with devastating consequences for children and society that will last for decades."

- Parents are given priority: the needs of the parents, not the rights of the children, are the priority.

-Loss of sense of urgency when a child is placed in care.

-Social workers: the need for a balance of social workers who have maturity (not necessarily skill level) and experience in the care and development of children and young workers who may be qualified. Everyone needs to be trained in a real child protection situation and taught to understand the priorities of the child, the need to act immediately, and so on.

Pike also noted that ideology plays a key role: there are a number of references in Australian sources to an anti-adoptive mentality in some educational institutions "and perhaps among professionals who are key intermediaries", such as employees of government welfare departments. A 2005 government report on foreign adoption noted that attitudes in these departments ranged from "indifference to hostility".

Feminist ideas about patriarchy and its "dominant prescriptions" are also included. Combined with revelations about previous scandals and forced adoptions, this has shaped public opinion that children should not be separated from their parents.

This is basically a reasonable principle: the child must be with the parents and reasonable steps must be taken to ensure that they can stay together. However, when a child is neglected or abused, despite the help of relatives and the intervention of the authorities, there must come a time when the best interests of the child dictate the need for his removal from the family. At this point, undoubtedly, efforts should be focused on providing the child with a loving, stable and permanent family.

Presumably, the principles of open adoption should apply if there is safety for the child and permission from the adoptive parents. Biological parents cannot be completely written off.

However, this should not be done with adoption either. As Pike says in the conclusion, “There is something about most adoptions that helps them end well. Despite all the complexities and shortcomings of the human experience, the mistakes of the past and the failures of the present, adoption remains a realistic and workable solution.

10%APRA's June 2021 stats on claims" title="" data-original-title="">

10%APRA's June 2021 stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> 1 months APRA's June 2021 stats on claims" title="" data-original-title="">

1 months APRA's June 2021 stats on claims" title="" data-original-title=""> T&Cs apply.

T&Cs apply.

..

.. T&C’s apply.

T&C’s apply.