Hemorrhage when giving birth

Postpartum hemorrhage

Donate

Contact

Events

DONATE

- Home >

- Pregnancy >

- Postpartum care > Postpartum hemorrhage

Topics

In This Topic

KEY POINTS

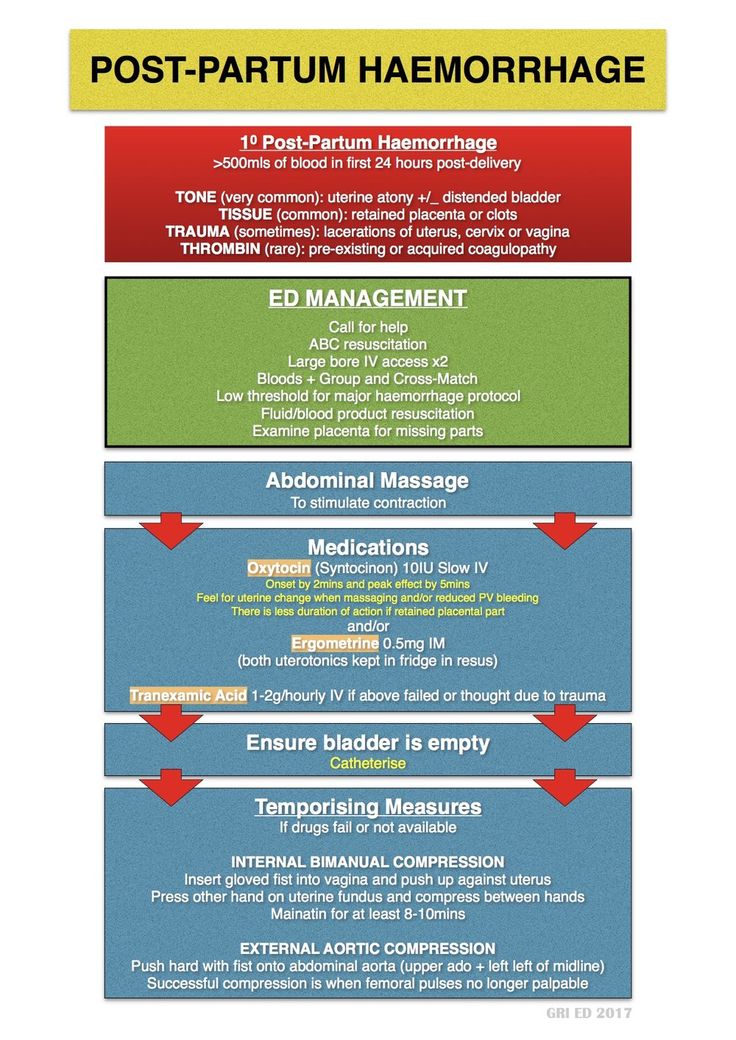

Postpartum hemorrhage (also called PPH) is a serious but rare condition when a woman has heavy bleeding after giving birth.

If you think you’re having PPH, call your health care provider or 911 immediately.

You may have PPH if you have heavy bleeding from the vagina that doesn’t slow or stop, blurred vision or chills, or if you feel weak or like you’re going to faint.

You’re more likely to have PPH if you’ve had it in the past or if you have certain medical conditions, especially conditions that affect the uterus (womb) or the placenta or conditions that affect how your blood clots.

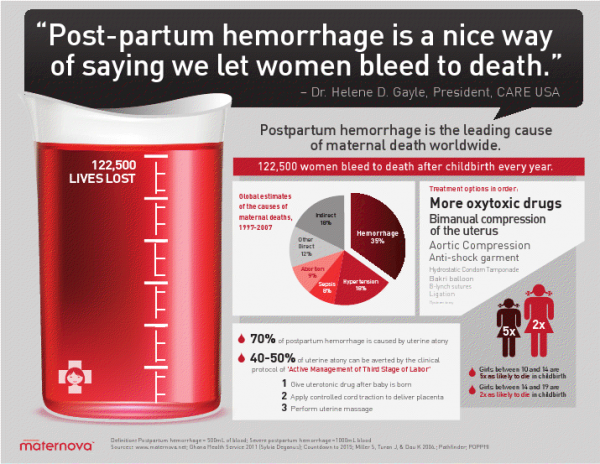

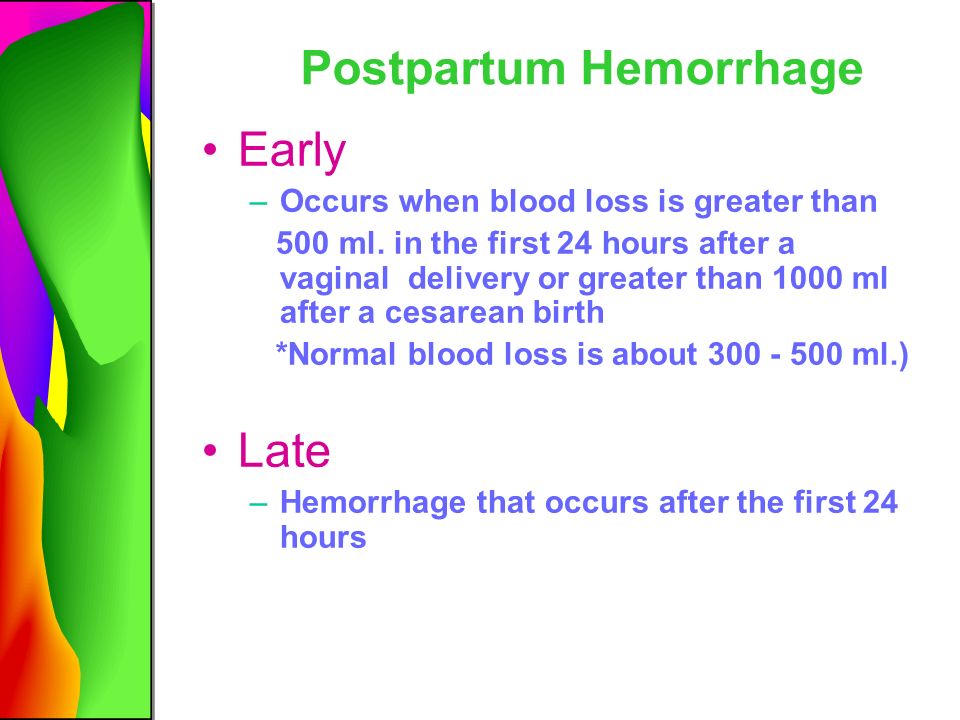

Postpartum hemorrhage (also called PPH) is when a woman has heavy bleeding after giving birth. It’s a serious but rare condition. It usually happens within 1 day of giving birth, but it can happen up to 12 weeks after having a baby. About 1 to 5 in 100 women who have a baby (1 to 5 percent) have PPH.

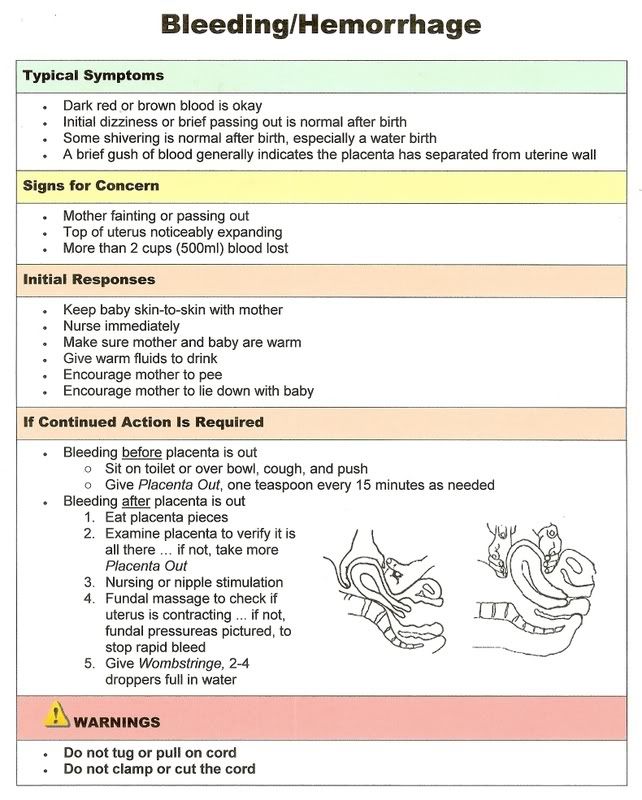

It’s normal to lose some blood after giving birth. Women usually lose about half a quart (500 milliliters) during vaginal birth or about 1 quart (1,000 milliliters) after a cesarean birth (also called c-section). A c-section is surgery in which your baby is born through a cut that your doctor makes in your belly and uterus (womb). With PPH, you can lose much more blood, which is what makes it a dangerous condition. PPH can cause a severe drop in blood pressure. If not treated quickly, this can lead to shock and death. Shock is when your body organs don’t get enough blood flow.

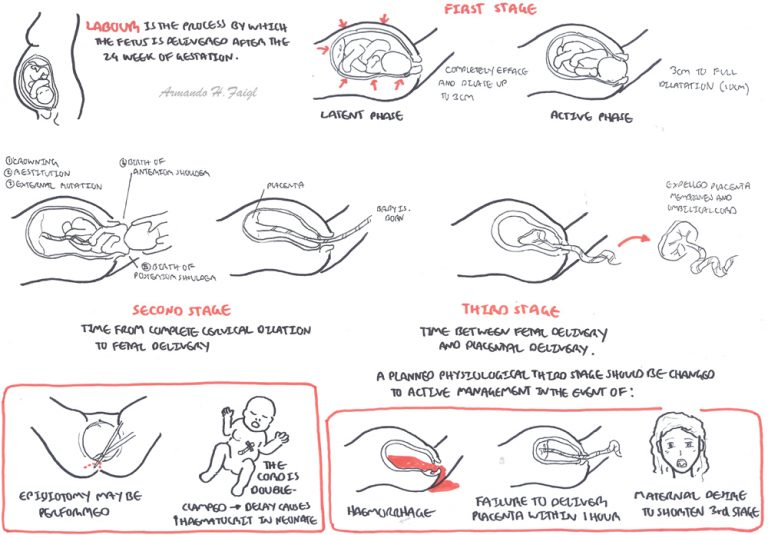

When does PPH happen?

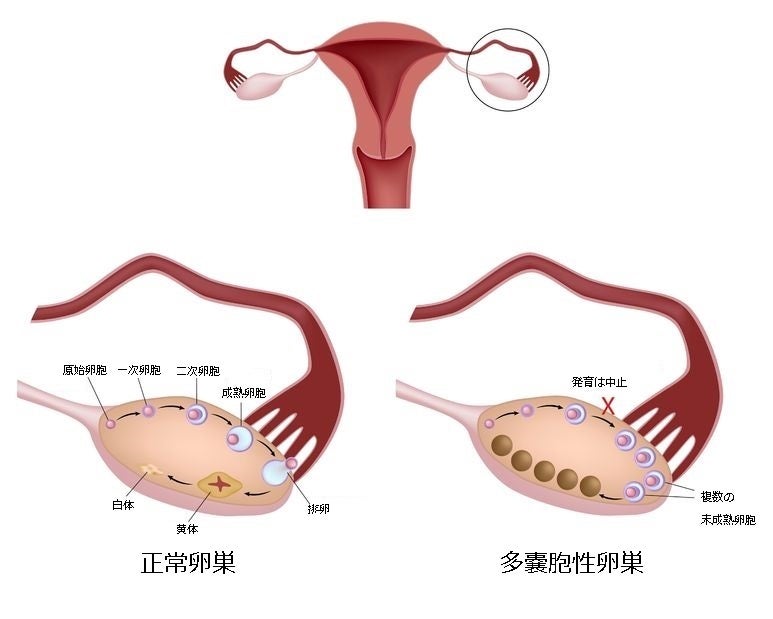

After your baby is delivered, the uterus normally contracts to push out the placenta. The contractions then help put pressure on bleeding vessels where the placenta was attached in your uterus. The placenta grows in your uterus and supplies the baby with food and oxygen through the umbilical cord. If the contractions are not strong enough, the vessels bleed more. It can also happen if small pieces of the placenta stay attached.

The contractions then help put pressure on bleeding vessels where the placenta was attached in your uterus. The placenta grows in your uterus and supplies the baby with food and oxygen through the umbilical cord. If the contractions are not strong enough, the vessels bleed more. It can also happen if small pieces of the placenta stay attached.

How do you know if you have PPH?

You may have PPH if you have any of these signs or symptoms. If you do, call your health care provider or 911 right away:

- Heavy bleeding from the vagina that doesn’t slow or stop

- Drop in blood pressure or signs of shock. Signs of low blood pressure and shock include blurry vision; having chills, clammy skin or a really fast heartbeat; feeling confused dizzy, sleepy or weak; or feeling like you’re going to faint.

- Nausea (feeling sick to your stomach) or throwing up

- Pale skin

- Swelling and pain around the vagina or perineum. The perineum is the area between the vagina and rectum.

Are some women more likely than others to have PPH?

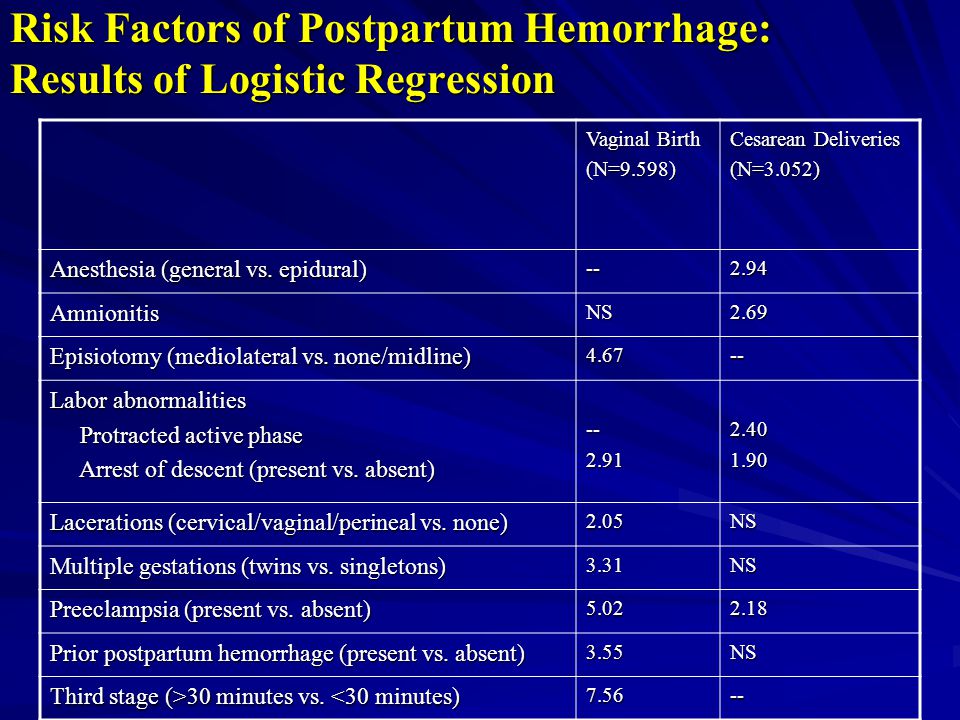

Yes. Things that make you more likely than others to have PPH are called risk factors. Having a risk factor doesn’t mean for sure that you will have PPH, but it may increase your chances. PPH usually happens without warning. But talk to your health care provider about what you can do to help reduce your risk for having PPH.

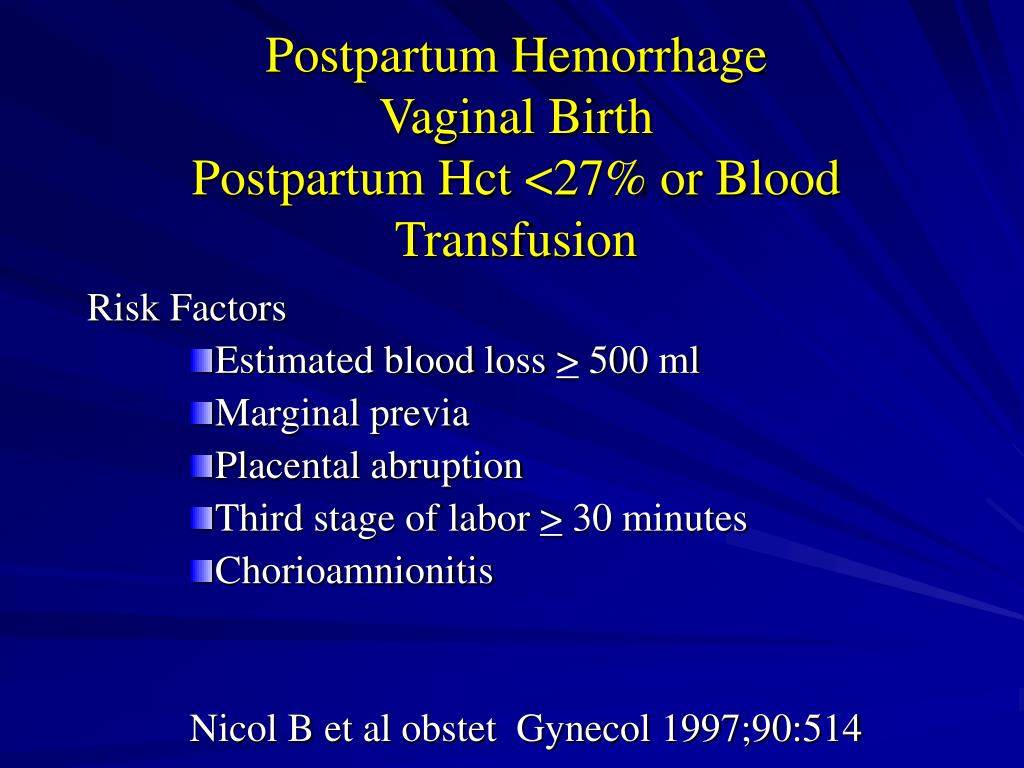

You’re more likely than other women to have PPH if you’ve had it before. This is called having a history of PPH. Asian and Hispanic women also are more likely than others to have PPH.

Several medical conditions are risk factors for PPH. You may be more likely than other women to have PPH if you have any of these conditions:

Conditions that affect the uterus

- Uterine atony. This is the most common cause of PPH. It happens when the muscles in your uterus don’t contract (tighten) well after birth. Uterine contractions after birth help stop bleeding from the place in the uterus where the placenta breaks away.

You may have uterine atony if your uterus is stretched or enlarged (also called distended) from giving birth to twins or a large baby (more than 8 pounds, 13 ounces). It also can happen if you’ve already had several children, you’re in labor for a long time or you have too much amniotic fluid. Amniotic fluid is the fluid that surrounds your baby in the womb.

You may have uterine atony if your uterus is stretched or enlarged (also called distended) from giving birth to twins or a large baby (more than 8 pounds, 13 ounces). It also can happen if you’ve already had several children, you’re in labor for a long time or you have too much amniotic fluid. Amniotic fluid is the fluid that surrounds your baby in the womb. - Uterine inversion. This is a rare condition when the uterus turns inside out after birth.

- Uterine rupture. This is when the uterus tears during labor. It happens rarely. It may happen if you have a scar in the uterus from having a c-section in the past or if you’ve had other kinds of surgery on the uterus.

Conditions that affect the placenta

- Placental abruption. This is when the placenta separates early from the wall of the uterus before birth. It can separate partially or completely.

- Placenta accreta, placenta increta or placenta percreta.

These conditions happen when the placenta grows into the wall of the uterus too deeply and cannot separate.

These conditions happen when the placenta grows into the wall of the uterus too deeply and cannot separate. - Placenta previa. This is when the placenta lies very low in the uterus and covers all or part of the cervix. The cervix is the opening to the uterus that sits at the top of the vagina.

- Retained placenta. This happens if you don’t pass the placenta within 30 to 60 minutes after you give birth. Even if you pass the placenta soon after birth, your provider checks the placenta to make sure it’s not missing any tissue. If tissue is missing and is not removed from the uterus right away, it may cause bleeding.

Conditions during labor and birth

- Having a c-section

- Getting general anesthesia. This is medicine that puts you to sleep so you don’t feel pain during surgery. If you have an emergency c-section, you may need general anesthesia.

- Taking medicines to induce labor.

Providers often use a medicine called Pitocin to induce labor. Pitocin is the man-made form of oxytocin, a hormone your body makes to start contractions.

Providers often use a medicine called Pitocin to induce labor. Pitocin is the man-made form of oxytocin, a hormone your body makes to start contractions. - Taking medicines to stop contractions during preterm labor. If you have preterm labor, your provider may give you medicines called tocolytics to slow or stop contractions.

- Tearing (also called lacerations). This may happen if the tissues in your vagina or cervix are cut or torn during birth. The cervix is the opening to the uterus that sits at the top of the vagina. You may have tearing if you give birth to a large baby, your baby is born through the birth canal too quickly or you have an episiotomy that tears. An episiotomy is a cut made at the opening of the vagina to help let the baby out. Tearing also can happen if your provider uses tools, like forceps or a vacuum, to help move your baby through the birth canal during birth. Forceps look like big tongs. A vacuum is a soft plastic cup that attaches to your baby’s head.

It uses suction to gently pull your baby as you push during birth.

It uses suction to gently pull your baby as you push during birth. - Having quick labor or being in labor a long time. Labor is different for every woman. If you’re giving birth for the first time, labor usually takes about 14 hours. If you’ve given birth before, it usually takes about 6 hours. Augmented labor may also increase risk of PPH. Augmentation of labor means medications or other means are used to make more contractions of the uterus during labor.

Other conditions

- Blood conditions, like von Willebrand disease or disseminated intravascular coagulation (also called DIC). These conditions can increase your risk of forming a hematoma. A hematoma happens when a blood vessel breaks causing a blood clot to form in tissue, an organ or another part of the body. After giving birth, some women develop a hematoma in the vaginal area or the vulva (the female genitalia outside of the body). Von Willebrand’s disease is a bleeding disorder that makes it hard for a person to stop bleeding.

DIC causes blood clots to form in small blood vessels and can lead to serious bleeding. Certain pregnancy and childbirth complications (like placenta accreta), surgery, sepsis (blood infection) and cancer can cause DIC.

DIC causes blood clots to form in small blood vessels and can lead to serious bleeding. Certain pregnancy and childbirth complications (like placenta accreta), surgery, sepsis (blood infection) and cancer can cause DIC. - Infection, like chorioamnionitis. This is an infection of the placenta and amniotic fluid.

- Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (also called ICP). This is the most common liver condition that happens during pregnancy.

- Obesity. Being obese means you have an excess amount of body fat. If you’re obese, your body mass index (also called BMI) is 30 or higher. BMI is a measure of body fat based on your height and weight. To find out your BMI, go to www.cdc.gov/bmi.

- Preeclampsia or gestational hypertension. These are types of high blood pressure that only pregnant women can get. Preeclampsia is a condition that can happen after the 20th week of pregnancy or right after pregnancy.

It’s when a pregnant woman has high blood pressure and signs that some of her organs, like her kidneys and liver, may not be working properly. Signs of preeclampsia include having protein in the urine, changes in vision and severe headache. Gestational hypertension is high blood pressure that starts after 20 weeks of pregnancy and goes away after you give birth. Some women with gestational hypertension have preeclampsia later in pregnancy.

It’s when a pregnant woman has high blood pressure and signs that some of her organs, like her kidneys and liver, may not be working properly. Signs of preeclampsia include having protein in the urine, changes in vision and severe headache. Gestational hypertension is high blood pressure that starts after 20 weeks of pregnancy and goes away after you give birth. Some women with gestational hypertension have preeclampsia later in pregnancy.

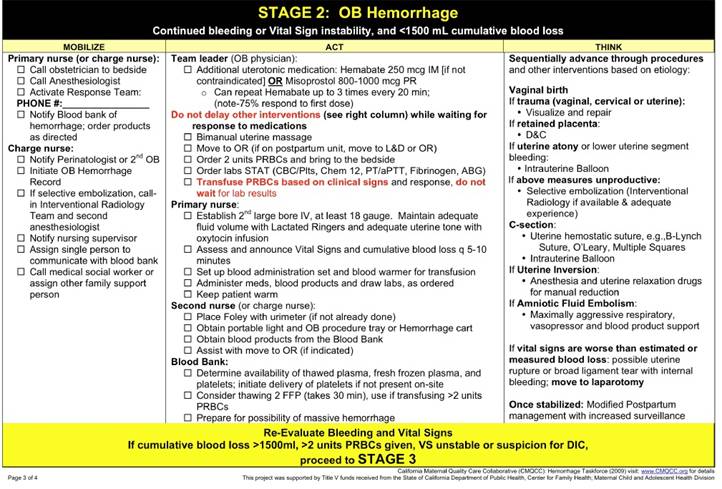

How is PPH tested for and treated?

Your provider may use these tests to see if you have PPH or try to find the cause for PPH:

- Blood tests called clotting factors tests or factor assays

- Hematocrit. This is a blood test that checks the percent of your blood (called whole blood) that’s made up of red blood cells. Bleeding can cause a low hematocrit.

- Blood loss measurement. To see how much blood you’ve lost, your provider may weigh or count the number of pads and sponges used to soak up the blood.

- Pelvic exam. Your provider checks your vagina, uterus and cervix.

- Physical exam. Your provider checks your pulse and blood pressure.

- Ultrasound. Your provider can use ultrasound to check for problems with the placenta or uterus. Ultrasound is a test that uses sound waves and a computer screen to make a picture of your baby inside the womb or your pelvic organs.

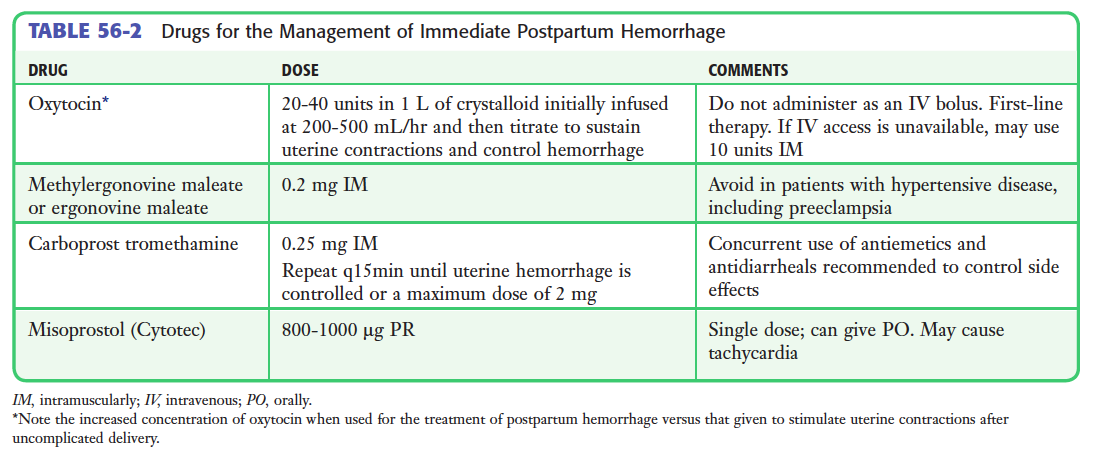

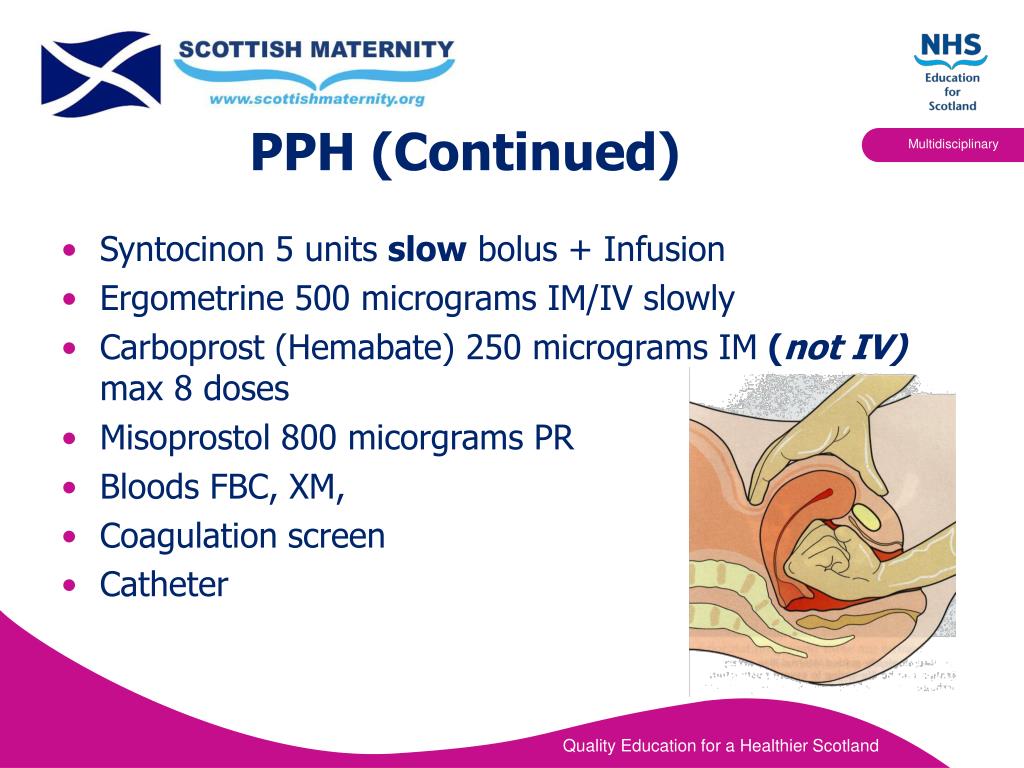

Treatment depends on what’s causing your bleeding. It may include:

- Getting fluids, medicine (like Pitocin) or having a blood transfusion (having new blood put into your body). You get these treatments through a needle into your vein (also called intravenous or IV), or you may get some directly in the uterus.

- Having surgery, like a hysterectomy or a laparotomy. A hysterectomy is when your provider removes your uterus. You usually only need a hysterectomy if other treatments don’t work.

A laparotomy is when your provider opens your belly to check for the source of bleeding and stops the bleeding.

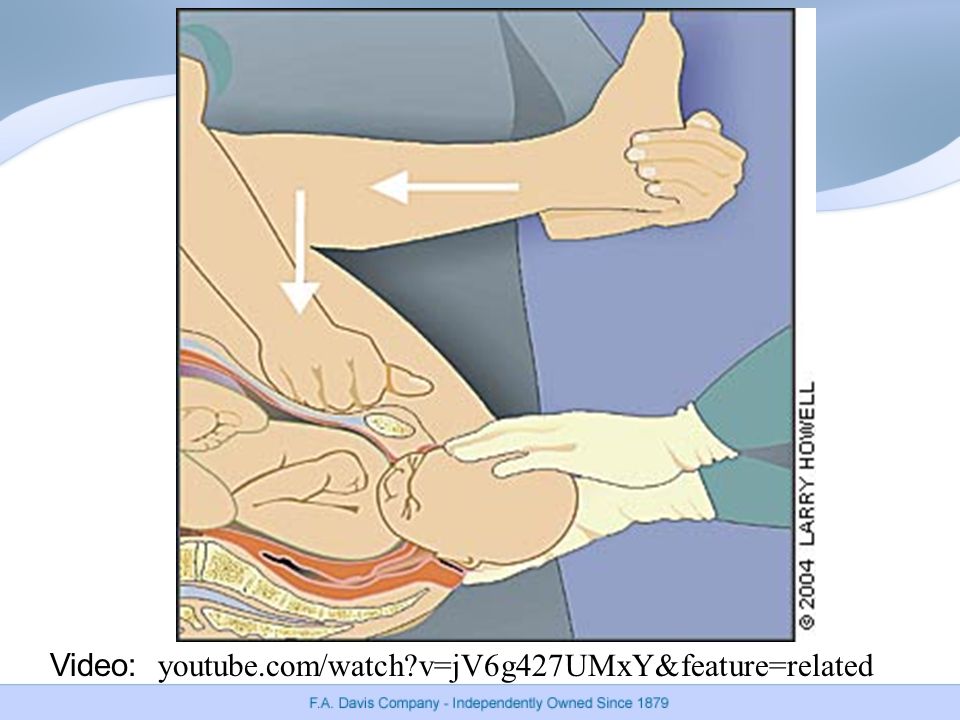

A laparotomy is when your provider opens your belly to check for the source of bleeding and stops the bleeding. - Massaging the uterus by hand. Your provider can massage the uterus to help it contract, lessen bleeding and help the body pass blood clots. Your provider may also give you medications like oxytocin to make the uterus contract and lessen bleeding.

- Getting oxygen by wearing an oxygen mask

- Removing any remaining pieces of the placenta from the uterus, packing the uterus with gauze, a special balloon or sponges, or using medical tools or stitches to help stop bleeding from blood vessels.

- Embolization of the blood vessels that supply the uterus. In this procedure, a provider uses special tests to find the bleeding blood vessel and injects material into the vessel to stop the bleeding. It’s used in special cases and may prevent you from needing a hysterectomy.

- Taking extra iron supplements along with a prenatal vitamin may also help.

Your provider may recommend this depending on how much blood was lost.

Your provider may recommend this depending on how much blood was lost.

See also: Maternal death

Last reviewed March 2020

') document.write('

Nutrition, weight & fitness

') document.write('') }

') document.write('

Prenatal care

') document.write('') }

Postpartum haemorrhage | Pregnancy Birth and Baby

Postpartum haemorrhage | Pregnancy Birth and Baby beginning of content10-minute read

Listen

If your bleeding is getting heavier and you have given birth within the last 6 weeks, call your doctor or go to your hospital's emergency department.

Key facts

- Postpartum haemorrhage is when you lose a large amount of blood after giving birth. It can be serious and even life threatening.

- It is most often caused by your uterus not contracting properly after your baby is born. If it occurs more than 24 hours after you give birth, it’s usually caused by an infection.

- Postpartum haemorrhage is unpredictable and can affect anyone, so it’s important that everyone who gives birth has access to emergency medical care if needed.

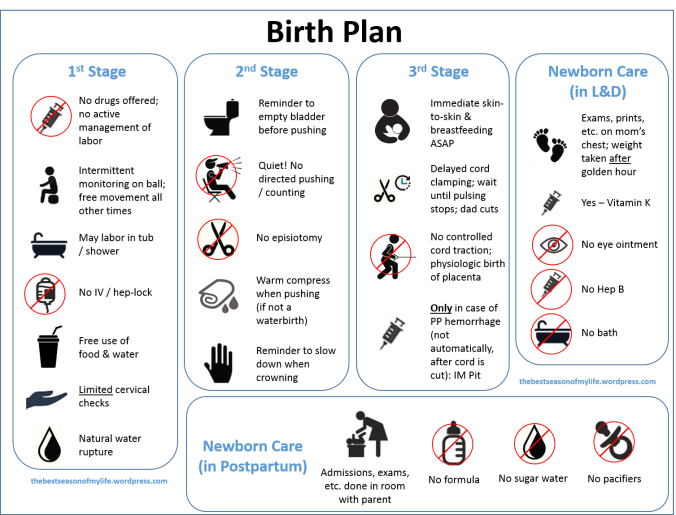

- After your baby is born, you will be offered an injection of medicine to help your uterus contract to help the placenta come out, and reduce your risk of postpartum haemorrhage.

- If you have a postpartum haemorrhage, you may need additional medicines, a blood transfusion or surgery to stop the bleeding.

What is postpartum haemorrhage?

Postpartum haemorrhage is when you bleed more than normal after giving birth. It's defined as passing more than 500ml of blood from your vagina after having a baby.

It's defined as passing more than 500ml of blood from your vagina after having a baby.

If this bleeding occurs in the first 24 hours after the birth, it's called a primary postpartum haemorrhage. If it occurs more than 24 hours but within 6 weeks after birth, it's called a secondary postpartum haemorrhage.

Postpartum haemorrhage is very serious and can be life threatening. Medical attention is needed very quickly to stop the bleeding.

Postpartum haemorrhage happens after 5 to 15 out of every 100 births in Australia.

What causes postpartum haemorrhage?

Postpartum haemorrhage is most often caused by your uterus (womb) not contracting as it should after the birth. When your uterus contracts, it helps push the placenta out and reduces bleeding from the large blood vessels that delivered blood to the placenta. If your uterus doesn’t contract properly, those blood vessels can continue to bleed.

It can also be caused by an injury to your uterus, cervix, vagina or perineum. In other cases, it is caused by a problem with the placenta such as placenta praevia, placental abruption, placenta accreta or retained placenta.

In other cases, it is caused by a problem with the placenta such as placenta praevia, placental abruption, placenta accreta or retained placenta.

Who is likely to have a postpartum haemorrhage?

Most people who have a postpartum haemorrhage don't have any known risk factors. It can happen to anyone and it's unpredictable.

However, it is more likely if you have:

- given birth 3 or more times previously – the risk goes up the more times you have given birth

- a very stretched uterus (for example, if you are carrying a large baby or multiple babies or you have a lot of amniotic fluid)

- a problem with the way the placenta is attached to your uterus

- a bleeding disorder

- had a postpartum haemorrhage before

- uterine fibroids

- other health conditions, for example, a BMI over 35, high blood pressure, anaemia, or diabetes

You have also at a higher risk of a postpartum haemorrhage if:

- you have a very long or very fast labour

- you are induced to go into labour

- your baby is delivered by forceps, vacuum or caesarean

- part or all of the placenta doesn't come out

- you develop an infection

- your baby's shoulders get stuck in the birth canal during delivery

Can postpartum haemorrhage be prevented?

Because postpartum haemorrhage is so unpredictable, it’s important that anyone giving birth has access to emergency medical care after they have their baby.

You will be offered an injection of a medicine containing oxytocin once your baby is born, to help your uterus contract. This can lower your risk of postpartum haemorrhage by half.

Your midwife or doctor can actively help deliver the placenta rather than waiting for it to come out by itself. If your doctor or midwife thinks you are at increased risk of postpartum haemorrhage, they may recommend you give birth in a major hospital with blood products ready in case you need a blood transfusion.

It’s very important that you have an ultrasound during pregnancy to see where your placenta is located and check whether you are at high risk of severe bleeding.

How is primary postpartum haemorrhage treated?

Postpartum haemorrhage is a medical emergency. To treat it, your medical team will insert an IV needle into a vein and possibly a catheter into your bladder. They will examine you to find the cause of the bleeding and keep a close eye on your blood pressure and pulse.

Treatments for postpartum haemorrhage include:

- massaging your uterus to help it contract and help the placenta come out

- giving you fluids through your IV

- giving you medicines to reduce bleeding

- offering you a blood transfusion

If the bleeding still can’t be controlled, you may need to have surgery to remove the placenta or any remaining tissue, or to repair an injury that’s causing the bleeding. There are other surgical procedures that can stop bleeding, such as inserting a surgical balloon into your uterus. Sometimes the only way to stop the bleeding and save your life might be to remove your uterus (hysterectomy).

Afterwards, you will need to be closely monitored in hospital, sometimes in an intensive care unit (ICU).

How is secondary postpartum haemorrhage treated?

Postpartum haemorrhage that begins more than 24 hours after giving birth is usually caused by an infection or retained tissue in your uterus. It is usually treated with antibiotics. You may need to have medicine to help your uterus contract or an operation to remove any tissue still inside your uterus.

It is usually treated with antibiotics. You may need to have medicine to help your uterus contract or an operation to remove any tissue still inside your uterus.

If you are very unwell from blood loss, you may need the same treatment as for primary postpartum haemorrhage.

How do I know if I’m bleeding too much?

While bleeding after giving birth is normal, you may have a postpartum haemorrhage if:

- you are soaking through a pad every hour or two

- you are passing blood clots

- the blood you pass becomes bright red

If your bleeding is getting heavier and you have given birth within the last 6 weeks, call your doctor or go to your hospital’s emergency department.

Can postpartum haemorrhage cause any other problems?

If you lose a lot of blood, you might develop anaemia. Your doctor can check this with a blood test. You may need to have iron therapy or a blood transfusion.

Sometimes breastfeeding is more difficult after a postpartum haemorrhage. Speak to your midwife if you are having trouble with breastfeeding.

Speak to your midwife if you are having trouble with breastfeeding.

If you’ve had a postpartum haemorrhage you have a higher risk of developing a blood clot. It’s important to stay active and drink plenty of water. Speak to your doctor to see if there’s anything else you should do to prevent blood clots.

People whose labour didn't go to plan may feel negative emotions about their birth experience. You may feel upset or anxious about what happened. It can help to talk to someone.

You can seek advice or support from:

- The medical team who cared for you during your postpartum haemorrhage

- Your doctor or midwife

- Perinatal Anxiety and Depression Australia (PANDA) on 1300 726 306

- Australasian Birth Trauma Association

- Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636

You can call Pregnancy, Birth and Baby to speak to a maternal child health nurse on 1800 882 436.

When should I see a doctor?

If you have recently given birth, you should see your doctor immediately if you have:

- increased bleeding

- fever

- shortness of breath

- pain, redness or swelling in your leg

You should also see your doctor if you’re feeling very tired or anxious.

Will postpartum haemorrhage affect my pregnancies in the future?

You are at increased risk of having another postpartum haemorrhage next time. It’s very important to tell your medical team during your next pregnancy, so they can try to prevent it from happening again.

If you’re worried about the possibility of a postpartum haemorrhage in future pregnancies, it can help to talk to your doctor or midwife so they can explain what happened.

Speak to a maternal child health nurse

Call Pregnancy, Birth and Baby to speak to a maternal child health nurse on 1800 882 436 or video call. Available 7am to midnight (AET), 7 days a week.

Sources:

Safer Care Victoria (Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) – prevention, assessment and management), Queensland Health (Severe bleeding after birth), RANZCOG (Management of Postpartum Haemorrhage (PPH)), RANZCOG (Provision of routine intrapartum care in the absence of pregnancy complications), Australasian Birth Trauma Association (Psychological birth trauma), Women’s and Children’s Hospital (Postpartum haemorrhage prevention and management)Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Last reviewed: June 2022

Back To Top

Related pages

- Labour complications

- Giving birth - stages of labour

Need more information?

Psychological Trauma - Birth Trauma

Read more on Australasian Birth Trauma Association website

Severe bleeding after birth

Read more on Queensland Health website

Labour complications

Even if you’re healthy and well prepared for childbirth, there’s always a chance of unexpected problems. Learn more about labour complications.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Retained placenta

A retained placenta is when part or all of the placenta is not delivered after the baby is born. It can lead to serious infection or blood loss.

It can lead to serious infection or blood loss.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Shoulder dystocia

Shoulder dystocia happens when a baby's shoulder gets stuck behind the mother’s pubic bone during birth. It is a medical emergency that requires immediate intervention. Find out why here.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Placenta accreta

Placenta accreta is a serious but rare pregnancy complication that causes heavy bleeding. If you have it, you will need special care at the birth.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Why do some mums stop breastfeeding before 6 months?

Most new parents know 'breast is best', but while more than 9 out of 10 babies are breastfed at birth, few mums are breastfeeding exclusively 5 months later.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Periods after pregnancy

After you've had your baby, you might be wondering how long until your periods return and if they will be the same as before your pregnancy.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - uterus

The uterus is your growing baby’s home during pregnancy. Learn how the uterus works, nurtures your baby and how it changes while you are pregnant.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Developing a birth plan - Better Health Channel

betterhealth.vic.gov.au

Read more on Better Health Channel website

Disclaimer

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is not responsible for the content and advertising on the external website you are now entering.

Need further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Video call

- Contact us

- About us

- A-Z topics

- Symptom Checker

- Service Finder

- Linking to us

- Information partners

- Terms of use

- Privacy

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is funded by the Australian Government and operated by Healthdirect Australia.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is provided on behalf of the Department of Health

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby’s information and advice are developed and managed within a rigorous clinical governance framework. This website is certified by the Health On The Net (HON) foundation, the standard for trustworthy health information.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

Bleeding during childbirth: when is it dangerous? at the time of delivery of the placenta 5-10 minutes after the birth of the baby. A woman loses 200-350 ml of blood (0.5% of body weight). Nature has foreseen such a loss.

During pregnancy, the volume of circulating blood increases by one third, including in order to compensate for the loss. At the moment of delivery of the placenta, a protective mechanism is triggered: the walls of the uterus contract and, shrinking, block the blood vessels. They immediately form blood clots that close the lumen. In parallel, the vessels narrow very strongly and "leave" deep into the flesh.

Risk group

If a woman loses more than 400 ml of blood, doctors talk about pathological obstetric bleeding, which is already considered a complication. The risk group includes women who have already had a caesarean section (after the operation, a scar remains on the uterus, so the risk of rupture during natural childbirth increases), as well as expectant mothers expecting twins or a large baby. Other causes of bleeding during childbirth include polyhydramnios, uterine diseases (chronic endometritis, tumors), serious non-gynecological chronic ailments (diabetes mellitus, kidney failure, hepatitis) and blood clotting disorders. The age of the expectant mother can also affect the extent of blood loss: if she is over 35 years old, the risk of weakening labor activity and reducing the contractility of the uterus muscles increases.

Bleeding during childbirth may be due to problems with the placenta, rupture of the uterus or birth canal. In the first hours after the birth of the baby, a complication most often occurs due to hypotension of the uterus, when its muscles lose their tone and contractility. In each individual case, doctors act differently, but the goal is always the same - to stop blood loss as soon as possible. Fortunately, despite the fact that blood is lost quickly and in large quantities and it is not so easy to stop the process, it is still possible to minimize undesirable consequences.

In each individual case, doctors act differently, but the goal is always the same - to stop blood loss as soon as possible. Fortunately, despite the fact that blood is lost quickly and in large quantities and it is not so easy to stop the process, it is still possible to minimize undesirable consequences.

Attachment point

Abundant blood loss can be caused by premature detachment of the placenta, which most often develops against the background of such a pregnancy complication as preeclampsia (in other words, preeclampsia). This disease can be accompanied by sharp jumps in blood pressure, during which the vessels in the area of attachment of the placenta to the wall of the uterus break ahead of time, which is why profuse bleeding begins.

Medical tactics will depend on where exactly this “attachment point” is located. Normally, the placenta is attached to the upper part of the uterus, on its anterior or posterior wall. But it also happens differently. For example, if the placenta is located on the edge, opening the fetal bladder sometimes helps to stop the bleeding. When the amniotic fluid is poured out, the baby's head, sinking to the pelvic floor, presses the exfoliated area of the placenta and the vessels that burst ahead of time. If the placenta is attached to the uterus in the center, an emergency caesarean section will be required.

When the amniotic fluid is poured out, the baby's head, sinking to the pelvic floor, presses the exfoliated area of the placenta and the vessels that burst ahead of time. If the placenta is attached to the uterus in the center, an emergency caesarean section will be required.

- Photo

- Getty Images

Overcoming obstacles

The diagnosis of "placenta previa" means that the "attachment point" is located at the very exit, that is, at the internal os of the cervix. The main cause of improper dislocation is endometritis (a chronic inflammatory disease of the uterus), which leads to a change in the structure of the uterine mucosa. As a result, the chorion (the precursor of the placenta) is attached in the wrong place - next to the cervix. And the vessels in the area of the placental site burst at the very beginning of labor, when contractions barely begin. Since the baby is still inside, the uterus cannot contract to compress the ruptured vessels, and the bleeding does not stop. Doctors can notice placenta previa even in the early stages of pregnancy, during routine ultrasounds. Careful control is established for the expectant mother, she is prescribed bed rest and sexual rest, and a planned caesarean section allows preventing blood loss at the time of childbirth.

Since the baby is still inside, the uterus cannot contract to compress the ruptured vessels, and the bleeding does not stop. Doctors can notice placenta previa even in the early stages of pregnancy, during routine ultrasounds. Careful control is established for the expectant mother, she is prescribed bed rest and sexual rest, and a planned caesarean section allows preventing blood loss at the time of childbirth.

Unexpected retention

Problems with the placenta can also occur in the third stage of labor when the placenta (placenta, membranes and umbilical cord) appears. The reason is the same - chronic inflammatory diseases of the uterus. Normally, the placenta departs 5-10 minutes after the birth of the baby. With a delay, doctors inject oxytocin, a hormone that causes uterine contractions, through a drip. If there is no result, then the placenta is attached too tightly and cannot come out on its own. In this case, the doctor separates it with his hand. This manipulation is considered an operation and is performed under intravenous anesthesia.

After the placenta appears, the midwife very carefully examines the placenta for integrity. If part of the placenta has departed, and part has remained inside, in a place where the vessels have already burst, bleeding begins, because the uterus can contract properly only after the placenta is completely born. Manual separation of the placenta and removal of the placenta again helps to correct the situation.

High voltage

Bleeding can also start due to rupture of the birth canal in the first stage of labor, when, not listening to the recommendations of the midwife, the woman begins to push ahead of time. But if you strictly follow all the instructions of the doctors, this trouble can be avoided. In the second stage of labor, the main causes of bleeding (except for cervical rupture) may be perineal or clitoral tears. To prevent rupture of the perineum, an episiotomy or perineotomy is done (an incision in the perineum at the height of the contraction).

Last effort

If the delivery was prolonged, hypotonic bleeding may develop in the first two hours after the baby is born. The muscles of the uterus get very tired and do not respond to oxytocin, do not contract; accordingly, bursting vessels are not pinched. If an additional dose of oxytocin does not help, a "control manual examination of the walls of the uterus" is performed, designed to cause its reflex contractions. The doctor inserts one hand into the vagina, puts the other on the stomach and tries to compress the uterus from both sides. If the bleeding does not stop, the anterior abdominal wall is cut under general anesthesia and the iliac arteries are ligated.

The muscles of the uterus get very tired and do not respond to oxytocin, do not contract; accordingly, bursting vessels are not pinched. If an additional dose of oxytocin does not help, a "control manual examination of the walls of the uterus" is performed, designed to cause its reflex contractions. The doctor inserts one hand into the vagina, puts the other on the stomach and tries to compress the uterus from both sides. If the bleeding does not stop, the anterior abdominal wall is cut under general anesthesia and the iliac arteries are ligated.

- Photo

- Getty Images/iStockphoto

Express method

For heavy bleeding, a rapid hemoglobin test is performed. If the indicators fluctuate within acceptable limits, the volume of fluid in the vessels is restored using special solutions (saline, glucose, etc.). When the hemoglobin level is very low, a blood transfusion is required. For prevention purposes, drugs that increase blood clotting are also used.

For prevention purposes, drugs that increase blood clotting are also used.

More useful materials for expectant mothers - in our channel on Yandex.Zen.

Lyubov Prishlaya

Reading today

“The mother-in-law constantly compares her grandson with someone else's child. What is she up to?

Reluctant child prodigy: how the closest people prepared for Nika Turbina a truly tragic fate

4 tips on how to end a relationship without a future0003

Survived the loss of a child, hid her daughter for 5 years: 8 facts from the life of Victoria Isakova

Prevention of obstetric bleeding in high-risk patients. Modern treatment tactics

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is a life-threatening complication of spontaneous and operative delivery, one of the main factors of maternal morbidity and mortality both in developing countries and in countries with a low level of economic development. PPH occurs with a frequency of approximately 6% in all types of childbirth [1-4] and is associated with a number of severe conditions accompanied by a large amount of blood loss (severe anemia, heart failure, sepsis).

According to I.S. Sidorova [4], during pregnancy against the background of preeclampsia, the production of prostacyclin decreases and the secretion of a powerful vasoconstrictor and aggregant, thromboxane, increases. This leads to the occurrence of a generalized vascular spasm with the addition of a hypercoagulable syndrome. HELL. Makatsaria et al. [5] and T.A. Fedorova et al. [6] noted pronounced shifts in the hemostasis system towards hypercoagulation and an increase in the level of paracoagulation products characteristic of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) during pregnancy against the background of preeclampsia. E.B. Canes et al. [7] classify pregnant women with severe forms of preeclampsia as a group of especially dangerous obstetric hemorrhages.

The consequence of obstetric bleeding can be not only DIC, but also a number of other equally severe complications such as cardiovascular and renal failure, HELLP syndrome, and Sheehan's syndrome (postpartum pituitary necrosis) [8, 9]. Thus, the pathogenetic basis of disorders of the hemostasis system consists in the generalization of the process of intravascular thrombosis with subsequent depletion of anticoagulant factors and the development of severe coagulopathic disorders, so even a slight excess of physiological blood loss can trigger the development of DIC [4].

Thus, the pathogenetic basis of disorders of the hemostasis system consists in the generalization of the process of intravascular thrombosis with subsequent depletion of anticoagulant factors and the development of severe coagulopathic disorders, so even a slight excess of physiological blood loss can trigger the development of DIC [4].

According to G.M. Savelyeva et al. [10], blood loss of more than 1000 ml (more than 25% of the circulating blood volume (CBV) or more than 1.5% of body weight) leads to the development of hemorrhagic shock. However, according to S.P. Lysenkova et al. [11], even with a blood loss of up to 20% of the BCC, changes characteristic of DIC can be observed in the hemostasis system: a short-term hypercoagulation phase is replaced by a hypocoagulation phase. Some domestic authors [5, 10] believe that hypercoagulation syndrome and hypovolemia, which are characteristic of the course of pregnancy against the background of preeclampsia, reduce the tolerance of the female body in the event of obstetric bleeding, and also lead to a breakdown in compensatory capabilities and the appearance of symptoms of shock and with less blood loss. In severe forms of preeclampsia, multiple organ failure and endogenous intoxication develop, which can lead to the death of the mother and / or fetus.

In severe forms of preeclampsia, multiple organ failure and endogenous intoxication develop, which can lead to the death of the mother and / or fetus.

Caesarean section (CS) is a recognized risk factor for the development of PPH, with the proportion of operative deliveries in recent years increasing to 20–30% in most developed countries and up to 40% in China [12, 13]. Despite the introduction of new methods of treatment into clinical practice, anomalies of labor activity are one of the main reasons for performing operative delivery, approximately every third CS is performed for anomalies of labor forces [14, 15].

According to foreign researchers [12, 13], in the structure of indications for abdominal delivery, the scar on the uterus predominates, its share is 15-38.2%, followed by preeclampsia - 16%, dystonia in childbirth - 13.4-42%, fetal distress - 10.9-19%. These indicators indicate that the interests of the fetus are considered as the leading reasons for performing CS in almost 80% of cases of operative delivery.

In recent decades, there has been a fairly clear trend towards a significant expansion of indications for CS, in turn, an increase in the frequency of CS performed can significantly reduce perinatal losses [16, 17]. The frequency of CS in the Russian Federation is 15-16%, reaching 30-40% in perinatal centers. The upward trend in this indicator is due to changing indications for surgery, among which in the last decade, “relative in the interests of the fetus” has been a priority [16, 18]. The implementation of delivery by CS and the performance of organ-preserving operations on the uterus contributed to an increase in the number of women of reproductive age with an operated uterus. At the same time, the management of subsequent pregnancies and childbirth in these patients is a complex problem. Re-K.S. not only requires large material costs, but also increases the risk of intra- and postoperative complications. At the same time, the level of maternal morbidity and mortality in this contingent of women is significantly higher than those after spontaneous delivery and the first CS [2, 19].

The frequency of massive obstetric bleeding after CS is higher than after vaginal delivery, which causes some concern for specialists due to the steady increase in the proportion of planned and emergency CS in the total number of births. At the same time, some risk factors for the need to perform a CS are simultaneously risk factors for the development of PPH [20]. The high incidence of complications after CS necessitates the improvement of methods for their prevention. For this purpose, intravenous drip slow administration of oxytocin has been used for a long time [21, 22]. However, this drug has a short half-life (10–15 min) in the body both during the operation and in the early postoperative period. At the same time, it is during this period that the maximum frequency of PPH is observed [20, 22].

Thus, the problem of ensuring safe and effective prevention of PPH during operative delivery by CS is topical. In clinical practice, a wide range of methods for the prevention of PPH is used; therefore, a clear algorithm of actions is needed that would provide an optimal result.

The purpose of the study was to analyze the literature data on the use of carbetocin for the treatment of obstetric bleeding after CS.

WHO currently recommends active management of the third stage of labor to prevent PPH. As part of this set of measures for the prevention of PPH, the following actions are carried out:

1) administration of a uterotonic preparation immediately after the birth of the child;

2) controlled pulling of the umbilical cord to deliver the placenta;

3) massage of the fundus of the uterus after the birth of the placenta [23].

In this case, the introduction of uterotonic drugs immediately after the birth of the child is considered the most important stage. Oxytocin is considered as a recommended drug when used in conditions where its effectiveness is beyond doubt [24]. Drugs from the group of uterotonic drugs play an important role in obstetrics, in particular in the implementation of labor activation and labor induction, as well as in the prevention and treatment of PPH. Regardless of the indications, when using uterotonic drugs, specialists achieve the optimal combination of efficacy and safety of their use, taking into account the characteristics of specific drugs, their dosages, routes of administration, clinical indications and contraindications for their use, as well as the individual characteristics of the patient [25].

Regardless of the indications, when using uterotonic drugs, specialists achieve the optimal combination of efficacy and safety of their use, taking into account the characteristics of specific drugs, their dosages, routes of administration, clinical indications and contraindications for their use, as well as the individual characteristics of the patient [25].

Oxytocin (10 IU IV or IM) is recommended as the uterotonic drug of choice. WHO and other organizations recommend storing oxytocin at a temperature of 2–8 °C in order to prevent the destruction of the active substance and maintain the effectiveness of the drug [26].

Synthetic oxytocin has been widely used in obstetric practice since the 1960s. For decades, a search has been made for a uterotonic drug with a more stable active substance to increase the effectiveness of its use. A more modern analogue of oxytocin is carbetocin, a drug that also acts on oxytocin receptors in the myometrium. According to a number of characteristics, this drug differs significantly from synthetic oxytocin - its half-life is much longer, the drug is more thermostable.

According to experts [12, 13, 25], the current lack of effective uterotonic drugs is a key obstacle to a significant reduction in maternal mortality in most countries of the world.

Currently, oxytocin and syntometrine (combination preparation containing 5 IU of oxytocin and 0.5 mg of ergometrine) are predominantly used to prevent PPH. Synthometrine acts quite quickly due to oxytocin and has a stable uterotonic effect due to ergometrine. Despite the fact that the prophylactic use of syntometrine in the III stage of labor effectively reduces blood loss and the frequency of PPH, the use of this drug leads to the development of adverse events from the cardiovascular (CVS) and digestive systems. So, when using syntometrine, nausea, vomiting and an increase in blood pressure can be observed, primarily due to the activation of smooth muscle contraction and vasoconstriction, therefore syntometrin is contraindicated in preeclampsia and in the presence of a number of concomitant diseases, in particular CCC. Oxytocin is administered to such patients, although this drug is less effective in preventing PPH [27].

Oxytocin is administered to such patients, although this drug is less effective in preventing PPH [27].

In recent years, prostaglandins such as misoprostol and carboprost have been actively studied for the prevention of PPH. Misoprostol is less effective than parenteral uterotonic drugs in preventing PPH after spontaneous delivery, and its use is associated with a higher incidence of severe PPH and the need for additional uterotonic drugs [28], making misoprostol unsuitable for the prevention of PPH.

It should be noted that the effectiveness of uterotonic drugs in the prevention of PPH may be reduced under conditions that lead to degradation of the active substance. In a number of low- and middle-income countries, where it is not possible to provide the necessary conditions for transporting and storing the drug at all stages, the effectiveness of oxytocin cannot be guaranteed, since it decomposes under the influence of temperature [28]. To date, the fact of destruction of oxytocin under the influence of temperature is well known [29, thirty]. It has been shown that up to 45.6% of oxytocin samples do not pass quality assessment tests, primarily due to the insufficient content of the active substance in finished dosage forms [31]. Another study confirmed the low quality of uterotonic drugs in a number of countries around the world [32]. This study showed that 74.2% of injectable oxytocin samples and 33.7% of misoprostol samples did not meet the required quality level [32, 33].

It has been shown that up to 45.6% of oxytocin samples do not pass quality assessment tests, primarily due to the insufficient content of the active substance in finished dosage forms [31]. Another study confirmed the low quality of uterotonic drugs in a number of countries around the world [32]. This study showed that 74.2% of injectable oxytocin samples and 33.7% of misoprostol samples did not meet the required quality level [32, 33].

Relatively common are ergometrine or methylergometrine, misoprostol, and fixed-dose combinations. Ergometrine is degraded when exposed to heat or light, while misoprostol is rapidly degraded when exposed to moisture [34]. The degradation of the active substance leads to a decrease in its concentration and to a decrease in the effectiveness of the drug.

Recent studies state that oxytocin has “unsatisfactory actual efficacy in real clinical practice due to temperature sensitivity” [30]. However, this suggestion is based solely on an estimate of the amount of pharmacologically active substance in the samples, and not on data on the effectiveness of the drug obtained in clinical studies on patients.

It has been shown that the route of administration of the drug is of great importance for the effectiveness of drugs in the prevention of PPH [31, 34]. Thus, in a double-blind study that evaluated the comparative efficacy of oxytocin at a dose of 10 IU intravenously and intramuscularly, significant differences were shown in the parameters used as clinically significant endpoints. The success rate for the prevention of blood loss equal to or greater than 1000 cm3 3 , defined as an adjusted odds ratio (aOR), was 0.54 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.32-0.91), the indicator of the reduction in the need for blood transfusion is OR 0.31 (95% CI 0.13-0.70), i.e. the effectiveness of the drug when administered intravenously higher than with intramuscular [35].

Along with this, differences were found when using the drug in doses of 5 and 10 I.U. Thus, a pooled analysis of the results with blood loss equal to or more than 500 cm 3 as an end point showed that the effectiveness of oxytocin at doses of 5 and 10 IU is comparable, the OR values were 0. 42 (95% CI 0.17–1.01) and 0.47 (95% CI 0.38–0.59) [36].

42 (95% CI 0.17–1.01) and 0.47 (95% CI 0.38–0.59) [36].

In the 1990s, carbetocin, a synthetic analog of human oxytocin with structural modifications, was proposed for use in clinical practice, prolonging its half-life in the body, which in turn increases the duration of the drug effect by 4–10 times [12, thirty]. The data available to date suggest a higher efficacy of carbetocin as a drug for the prevention and treatment of PPH compared with oxytocin and other drugs and their combinations [35].

Carbetocin is a long-acting synthetic analogue of oxytocin that can be administered as a single intravenous or intramuscular injection. When studying the pharmacodynamic characteristics of the drug, it was found that intravenous administration of carbetocin led to the development of tetanic contraction of the uterus for 2 minutes, followed by rhythmic contractions for 1 hour. Intramuscular administration of the drug was accompanied by the development of tetanic contraction of the uterus for 2 minutes lasting about 11 minutes, followed by rhythmic within 2 h [36].

It has been established that carbetocin, when administered in the postpartum period, has a longer duration of action than oxytocin and causes more frequent contractions of greater amplitude [37].

Optimization of the production of carbetocin preparations has resulted in a product that meets the requirements of the International Council for the Harmonization of Specifications for Medicinal Products for Human Use (ICH) for hot and humid climates (zones IVA and B) for 36 months at 30 °C and for 6 months at a temperature of 40 °C [36]. In countries where refrigeration is not available at all stages of storage and transport, carbetocin, used as a safe uterotonic drug that is stable at higher temperature and humidity, may help reduce maternal mortality from PPH.

This drug is more stable and causes a prolonged uterine response when the drug is administered in the postpartum period. The drug manufacturer has developed a stable version of the molecule (heat-resistant carbetocin, formerly carbetocin RTS), which can potentially be used in countries where it is difficult to provide the necessary conditions (including temperature) during delivery and storage [36-39].

However, to date, the drug is not among the uterotonic drugs recommended by WHO for the prevention of PPH. This is primarily due to its unconfirmed efficacy in the prevention of PPH after vaginal delivery.

As is known, in addition to clinical efficacy, the most important characteristic of all drugs is their safety. At the same time, it should be taken into account that oxytocin and other uterotonic drugs are often used in unsafe conditions (the drug is administered until mechanical obstacles to head advancement are eliminated, intramuscularly or intravenously as a bolus, without careful monitoring of labor activity and in the absence of an opportunity to perform an emergency CS) [40]. Such unsafe use of these drugs has a significant impact on the incidence of adverse birth outcomes, significantly increasing their level in a number of countries in Asia and in some other regions [41, 42].

Carbetocin is not a safer drug in this respect. Perhaps, given the longer half-life of carbetocin, its wider use instead of oxytocin will increase the risk of adverse outcomes associated with misuse, in particular acute fetal hypoxia and uterine rupture.

One cannot ignore such characteristics of the considered group of drugs as their availability and cost. Thus, oxytocin is a relatively cheap and widely available drug, but in a number of countries generic drugs (generics) on the market often do not meet modern international quality standards. Of course, in order for carbetocin to be considered as a suitable alternative to oxytocin, it is necessary that the drug be equally cheap and widely available. Carbetocin manufacturer Ferring Pharmaceuticals (Switzerland) intends to make the drug “available in public sector institutions in countries with a high disease burden at an affordable price”, but at the moment this program is far from the declared level of its implementation [43].

To date, data from clinical studies have been obtained that have confirmed that the drug can be used at a dose of 100 micrograms intravenously or intramuscularly for the prevention of bleeding after CS. At the same time, it is considered that carbetocin should be used in conditions of abdominal delivery in the presence of at least one risk factor for bleeding, including placenta previa, in the presence of signs of placental rotation, chorioamnionitis, more than one CS in history, duration of an anhydrous period of more than 24 hours, multiple pregnancy , estimated fetal weight of more than 4500 g, a history of PPH with plasma or blood transfusion, severe anemia, thrombocytopenic purpura [44, 45].

In August 2018, the New England Journal of Medicine presented the results of a large-scale international study comparing the effectiveness of carbetocin and synthetic oxytocin in the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage [30]. Based on the publication of the results of the study, some experts said that the use of carbetocin "will lead to a revolution in the prevention of maternal death." Although this statement seems to be an exaggeration, a number of clinical studies have been conducted to date on the effectiveness of carbetocin in the prevention of PPH after spontaneous delivery, including a controlled study "Heat Stable Carbetocin for preventing postpartum haemorrhage: a randomized non-inferiority ” with the participation of 30,000 patients [46] and “Intramuscular Oxytocics: A Comparison Study of Intramuscular Carbetocin, Syntocinon and Syntometrine for the Third Stage of Labor Following Vaginal Birth (IMox) — North Bristol NHS Trust” with the participation of 6285 patients [47]. Based on the results of these studies, the necessary rationale is provided for the inclusion of (thermostable) carbetocin in the global recommendations in response to the need for additional methods for the prevention of PPH [48].

Based on the results of these studies, the necessary rationale is provided for the inclusion of (thermostable) carbetocin in the global recommendations in response to the need for additional methods for the prevention of PPH [48].

Carbetocin is increasingly being used to prevent PPH after CS. Studies of the possibility of using carbetocin during CS have shown a high clinical efficacy of the drug in the prevention of PPH, while the safety of the drug is similar to that of oxytocin. The purpose of the study L. Su et al. [49] studied the effectiveness of intramuscular uterotonic drugs, as well as a comparison of the frequency and severity of side effects and the cost of carbetocin, oxytocin and fixed-dose oxytocin/ergometrine (syntometrine) combined preparations. All preparations were refrigerated throughout the study in accordance with the blinded study design. The study is particularly important because it also evaluated the combination oxytocin/ergometrine, which is widely used in the prevention of PPH due to its high efficacy, but its use is associated with a number of side effects.

It is believed that carbetocin should be used in puerperas with abdominal delivery and with at least one or more risk factors for postpartum haemorrhage [27, 43]. Reports of RCTs conducted to date indicate that to prevent bleeding after CS, the drug should be used at a dose of 100 μg intravenously or intramuscularly [30, 50, 51].

The aim of the study I. Gallos et al. [48] evaluated the clinical efficacy and safety of uterotonic drugs for the prevention of PPH, followed by the creation of a rating of available uterotonic drugs for use in clinical practice in accordance with efficacy and side effects. The science-based rating is intended to determine the most effective drug for the prevention of PPH.

The authors compared all uterotonic drugs and their combinations for the prevention of PPH (oxytocin, misoprostol, ergometrine, carbetocin, oxytocin + misoprostol, oxytocin + ergometrine) with placebo and no such treatment group. The meta-analysis included data from all RCTs and cluster studies that examined the efficacy and/or safety of these drugs for the prevention of PPH. The use of uterotonic drugs in the III stage of labor for the prevention of PPH was evaluated when compared with a control uterotonic drug, with placebo or no treatment. The target group included patients after operative delivery or spontaneous delivery that occurred in the hospital and out of hospital. According to the results of the study, the combinations of ergometrine + oxytocin, misoprostol + oxytocin, as well as the drug carbetocin, were shown to be more effective in preventing PPH with a volume of more than 500 ml. It was shown that the combination of ergometrine + oxytocin was the most effective in preventing PPH with a volume equal to or more than 1000 ml, and carbetocin was characterized by maximum safety - it had the most favorable side effect profile among the most effective drugs and their combinations.

The use of uterotonic drugs in the III stage of labor for the prevention of PPH was evaluated when compared with a control uterotonic drug, with placebo or no treatment. The target group included patients after operative delivery or spontaneous delivery that occurred in the hospital and out of hospital. According to the results of the study, the combinations of ergometrine + oxytocin, misoprostol + oxytocin, as well as the drug carbetocin, were shown to be more effective in preventing PPH with a volume of more than 500 ml. It was shown that the combination of ergometrine + oxytocin was the most effective in preventing PPH with a volume equal to or more than 1000 ml, and carbetocin was characterized by maximum safety - it had the most favorable side effect profile among the most effective drugs and their combinations.

The aim of the study by M. Widmer et al. [46], evaluated the effectiveness of thermostable carbetocin at a dose of 100 μg intramuscularly compared with oxytocin at a dose of 10 IU in the prevention of PPH after spontaneous delivery. Postpartum administration of this uterotonic drug has been shown to reduce the incidence of hypotonic PPH. According to the authors, most of the deaths of PPH can be avoided by the prophylactic administration of uterotonic agents during the third stage of labor.

Postpartum administration of this uterotonic drug has been shown to reduce the incidence of hypotonic PPH. According to the authors, most of the deaths of PPH can be avoided by the prophylactic administration of uterotonic agents during the third stage of labor.

Another meta-analysis compared the efficacy of carbetocin and oxytocin as uterotonic agents after spontaneous labor and operative delivery in 8 studies. In all studies, carbetocin was administered at a standard dose of 100 µg. The total dose of oxytocin ranged from 5 to 32.5 IU. Most head-to-head studies showed that the risk of PPH was not significantly reduced with carbetocin compared with oxytocin, with an hazard ratio (RR) of 0.66 (95% CI 0.42-1.06). However, the use of carbetocin is associated with significantly less need for additional uterotonic drugs (RR 0.68; 95% CI 0.55–0.84) and uterine massage (RR 0.54; 95% CI 0.31– 0.96). A comprehensive evaluation of efficacy showed that the risk of massive PPH (blood loss equal to or more than 1000 ml in the III stage of labor) against the background of carbetocin and oxytocin does not differ (RR 0. 91; 95% CI 0.39-2.15). With regard to the frequency of blood transfusions, OR levels were less than 1, while there were no statistically significant differences [51].

91; 95% CI 0.39-2.15). With regard to the frequency of blood transfusions, OR levels were less than 1, while there were no statistically significant differences [51].

A comparative meta-analysis of the incidence of side effects of carbetocin and oxytocin showed that the risk of side effects (nausea, vomiting, "hot flashes", headache, fever, tremor, abdominal/back pain, metallic taste in the mouth, sweating, shortness of breath and dyspnea, tachycardia, drop in blood pressure, itching, chills and decreased visual acuity) in patients after CS was comparable, except for the incidence of dizziness (RR 0.31; 95% CI 0.12-0.83). No statistically significant differences were shown after vaginal delivery for PPH rates (RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.43–2.09), the need for therapeutic uterotonics (RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.43–2.09), and the incidence of side effects of carbetocin and oxytocin. At the same time, the need for uterine massage with the introduction of carbetocin is significantly lower compared with oxytocin (RR 0. 70; 95% CI 0.52-0.94). There were no statistically significant differences in assessments in terms of blood loss, the level of decrease in hemoglobin and uterine tone after the administration of carbetocin and oxytocin after surgical and spontaneous labor [51].

70; 95% CI 0.52-0.94). There were no statistically significant differences in assessments in terms of blood loss, the level of decrease in hemoglobin and uterine tone after the administration of carbetocin and oxytocin after surgical and spontaneous labor [51].

O. Reyes and G. Gonzalez [50] conducted a comparative study of the efficacy of carbetocin and oxytocin in patients with severe preeclampsia after spontaneous or operative delivery. Carbetocin and oxytocin have been shown to be equally effective in the prevention of PPH, with carbetocin being a safe drug, making it a suitable alternative to oxytocin as it appears to have no clinically significant hemodynamic effects in massive PPH.

M. Moertl et al. [52] specifically investigated the hemodynamic effects of carbetocin versus oxytocin after C.S. Both drugs have been shown to have comparable hemodynamic effects as measured by heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels, and total peripheral vascular resistance, and have an acceptable safety profile for prophylactic use. In addition, a meta-analysis of 2 studies showed that against the background of carbetocin, the risk of developing arterial hypertension after spontaneous delivery is significantly lower than against the background of syntometrine.

In addition, a meta-analysis of 2 studies showed that against the background of carbetocin, the risk of developing arterial hypertension after spontaneous delivery is significantly lower than against the background of syntometrine.

The purpose of the study L.D. Belotserkovtseva et al. [53] compared the efficacy of carbetocin and oxytocin in preventing PPH in high-risk patients with abdominal delivery. According to the results of the study, equally high efficiency of the applied schemes was demonstrated. At the same time, it was found that significantly more women needed additional uterotonics in the postoperative period in the oxytocin group (43.6% compared to 97.3%). The volume of blood loss over 1000 ml was registered in 6 (2.8%) patients of the group in which carbetocin was used, and in 4 (2.2%) when using oxytocin. There was one case of hysterectomy in each group (0.5% each).

Ligation of the internal iliac arteries was used as the most common method of the surgical stage of bleeding control, which was performed in 22 (10. 1%) cases with carbetocin and in 13 (7.0%) with oxytocin. Most often, as an indication for ligation of blood vessels, the authors considered the presence of placental abruption or placenta previa. Compression sutures on the uterus, plasma and blood transfusions, as well as reinfusion of autoplasma and autoerythrocytes were performed with a similar frequency. Carbetocin has been shown to be effective in preventing bleeding in 97.2% of cases when performing CS in high-risk pregnant women. At the same time, the need for additional prescription of uterotonic drugs in the postoperative period decreased by more than 2 times.

1%) cases with carbetocin and in 13 (7.0%) with oxytocin. Most often, as an indication for ligation of blood vessels, the authors considered the presence of placental abruption or placenta previa. Compression sutures on the uterus, plasma and blood transfusions, as well as reinfusion of autoplasma and autoerythrocytes were performed with a similar frequency. Carbetocin has been shown to be effective in preventing bleeding in 97.2% of cases when performing CS in high-risk pregnant women. At the same time, the need for additional prescription of uterotonic drugs in the postoperative period decreased by more than 2 times.

It is generally accepted that the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage, which is the leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality, is higher with operative CS than with vaginal delivery. At the same time, the share of CS in the total number of births, most likely, will only grow in the foreseeable future. Currently, approaches to the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage differ significantly, and therefore, based on the evidence and the results of expert consensus, guidelines are being developed to select the most safe and effective treatment tactics for emergency CS.

Certainly, carbetocin is one of the drugs that act on the myometrium, which is considered as a potentially important tool to improve birth outcomes. There is a possibility that carbetocin will partially replace some other drugs in certain clinical situations. However, the need for oxytocin, misoprostol, tranexamic acid and ergot alkaloids will remain. The optimal strategy for the use of uterotonic drugs depends on the specific clinical setting. It is necessary to take into account the characteristics of the drugs used, the available data on efficacy and safety, as well as the peculiarities of the region in which the drug is used.

Heat-resistant carbetocin is currently being studied as a potential alternative to oxytocin for the prevention of PPH. It is likely that the results of the studies will become the basis for the revision of WHO recommendations on the prevention and treatment of bleeding: carbetocin may be included in the recommendations as a means of preventing postpartum hemorrhage. It is believed that the drug can also be included in the WHO list of essential medicines used for this purpose, if it is not possible to ensure optimal storage and transportation conditions for other uterotonic drugs. However, there are only a few reports in the literature about this approach to the prevention and treatment of bleeding during surgical delivery. Clear indications for the use of carbetocin in pregnant women with a high risk of bleeding have not been developed, there are no data from evidence-based studies of the efficacy and safety of this drug in this group of patients. Changes in the hemostasis system in pregnant women with the use of carbetocin, as well as the effect of the drug on hematological and biochemical parameters in women with a high risk of postpartum hemorrhage, have not been characterized, the effect of the use of this drug on the need for additional use of uterotonics in the postoperative period has not been evaluated.

It is believed that the drug can also be included in the WHO list of essential medicines used for this purpose, if it is not possible to ensure optimal storage and transportation conditions for other uterotonic drugs. However, there are only a few reports in the literature about this approach to the prevention and treatment of bleeding during surgical delivery. Clear indications for the use of carbetocin in pregnant women with a high risk of bleeding have not been developed, there are no data from evidence-based studies of the efficacy and safety of this drug in this group of patients. Changes in the hemostasis system in pregnant women with the use of carbetocin, as well as the effect of the drug on hematological and biochemical parameters in women with a high risk of postpartum hemorrhage, have not been characterized, the effect of the use of this drug on the need for additional use of uterotonics in the postoperative period has not been evaluated.

Studies conducted to date have shown that the incidence of side effects when using carbetocin is not higher than that when using oxytocin, the drug is no less effective than syntometrine, therefore it can become an alternative uterotonic agent for the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage after spontaneous labor and operative delivery.

However, despite the established efficacy and safety of carbetocin after CS, additional studies are needed to clarify the safety profile of this drug in the presence of concomitant diseases in parturient women, in particular arterial hypertension and other diseases of the cardiovascular system. It is also necessary to conduct studies aimed at clarifying the minimum effective dose of carbetocin, assessing the clinical and economic aspects of its use in the practice of obstetric medical institutions.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Credits

Babloyan A.G. — Postgraduate student of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Moscow State University of Medicine and Dentistry. A.I. Evdokimov” of the Ministry of Health of Russia, Moscow, Russia; https://orcid.org/ 0000-0001-6618-5077

Tsakhilova S.G. – MD, prof. FGBOU VO Moscow State University of Medicine and Dentistry named after A. I. A.I. Evdokimov” of the Ministry of Health of Russia, Moscow, Russia; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4898-6919

I. A.I. Evdokimov” of the Ministry of Health of Russia, Moscow, Russia; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4898-6919

Sakvarelidze N.Yu. – Candidate of Medical Sciences, Assoc. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Moscow State University of Medicine and Dentistry named after A.I. A.I. Evdokimov” of the Ministry of Health of Russia, Moscow, Russia; https://orcid.org/ 0000-0002-9041-6055

Pihut P.P. — Postgraduate student of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Moscow State University of Medicine and Dentistry. A.I. Evdokimov” of the Ministry of Health of Russia, Moscow, Russia; https://orcid.org/ 0000-0002-0716-955X

Zykova A.S. — Senior laboratory assistant of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Moscow State University of Medicine and Dentistry. A.I. Evdokimov” of the Ministry of Health of Russia, Moscow; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9577-4815

Morgoeva A.A. — Postgraduate student of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Moscow State University of Medicine and Dentistry.