Does medicare cover midwives

Midwives and Medicare after Health Care Reform

FAQs

Do we have Medicare equity?

Yes, As of January 1, 2011, Medicare payment for certified nurse-midwives services is increased to 100 percent of the Physician Fee Schedule (PFS). This increase from 65 percent was included in the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordability Care Act (PPACA) (aka Health Care Reform Legislation).

Why does it say that we are reimbursed at 80 percent?

Payment from Medicare for physician and CNM services is 80% of the actual charge but Medicare allows that physicians and CNMs bill the patient for the remaining 20 percent. CNMs and physicians are reimbursed equitably.

Why is Medicare equity so important?

Receiving 100% of the PFS under Medicare allows midwives to more easily expand service to women with disabilities of childbearing age as well as senior women covered by the Medicare program. Medicare also serves as the gold standard of reimbursement rates and sets a precedent for unequal reimbursement rates across specialties which provide similar services. Meaning, Medicare has opened the door to now fight for equitable reimbursement under Medicaid in the 22 states where midwives receive less than 100% as compared to physicians, as well as other third party payers.

Why were Certified Midwives (CMs) not included in the ACA legislation?

ACNM championed Medicare equity on behalf of CNMs and CMs. The legislature was unwilling to include CMs in the final health care reform legislation but ACNM and the Government Affairs Committee is continuing to work to include CMs under Medicare as health care reform legislation is addressed in the 112th Congress.

Can midwives initiate well-woman exams?

Yes, as before, well-woman or annual exams can be initiated by a midwife. A well-woman evaluation and management visit (99384-99387, 99394-99397) includes a history and physical, age-appropriate counseling, anticipatory guidance, risk factor reduction and appropriate lab testing.

Can a midwife initiate a wellness exam?

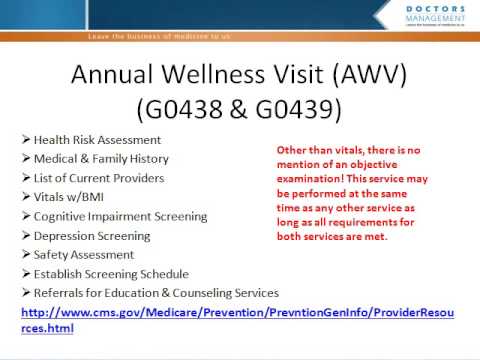

No. Initial and annual wellness exams are a new phenomenon under Medicare and introduced with the PPACA, only effective January 1, 2011. Unfortunately, midwives are not included in the list of providers able to initiate the wellness visit. Only physicians, nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists and physician assistants can initiate the wellness visit in the course of an office visit. However, midwives can participate in components of the wellness visit.

Initial and annual wellness exams are a new phenomenon under Medicare and introduced with the PPACA, only effective January 1, 2011. Unfortunately, midwives are not included in the list of providers able to initiate the wellness visit. Only physicians, nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists and physician assistants can initiate the wellness visit in the course of an office visit. However, midwives can participate in components of the wellness visit.

What is a wellness exam?

A wellness exam is not a well-woman annual exam or a physical. In fact, if a physical exam is performed at the annual wellness visit, it receives no additional payment from Medicare. A wellness exam (first visit G0438 or subsequent visit G0439) includes medical and family history, a list of medical providers and medications, height/weight/BMI/blood pressure and other routine measurements, detection of any cognitive impairment, a screening schedule for the next 5-10 years and health advice, and referrals for education and preventive services.

What if additional preventive physical exam services are provided to the Medicare recipient such as a pelvic or breast exam?

If additional preventive services such as a pelvic or breast exam are provided to the Medicare recipient, these are billed in addition to the wellness visit. This would include a pelvic and clinical breast exam (G0101) or a screening pap smear (Q0091). Keep in mind, Medicare will pay for this every two years, and if the patient meets Medicare's criteria for high risk, then the exam is reimbursed every year.

What is ACNM doing about this?

The ACNM national office has been working with the Secretary of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) since the language was first introduced in 2010 to include midwives to the list of providers eligible to initiate wellness exams under Medicare. ACNM is also working to include CNMs in another section of the AAPCA that would allow midwives to be included in an incentive payment program to receive an additional 10% of the payment amount for primary care services furnished from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2015.

Medicare Coverage and Reimbursement

Return to Advocate > Advocacy > Issue Areas > Medicare Coverage and Reimbursement

Issue Summary

Medicare is a program for those age 65 and over, the disabled and end-stage renal disease patients. Consequently, Medicare beneficiaries make up a fairly small part of the typical midwife's patient population. For example, total Medicare payments to CNMs in 2011 amounted to just over $3 million.

Medicare's real importance to midwifery lies in its position as the steward of various payment methodologies and policy structures that are often adopted by state Medicaid programs and private insurers. Consequently, understanding Medicare is often key to understanding how other coverage and reimbursement systems operate.

Available Literature and Resources

- ACNM Issue Brief: Medicare's Proposed CY 2016 Physician Fee Schedule (July 16, 2015)

- ACNM Issue Brief: H.R. 2 - The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (April 29, 2015)

- Congressional Research Service summary of the provisions of H.

R. 2: The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015, which contains significant modifications to Medicare's methodology for establishing payment for physician services (April 10, 2015)

R. 2: The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015, which contains significant modifications to Medicare's methodology for establishing payment for physician services (April 10, 2015) - ACNM Issue Brief on Final Rule Modifying Physician Certification Policy (December 12, 2014)

- ACNM Issue Brief on CY 2015 Final Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (December 12, 2014)

- ACNM Issue Brief on CY 2015 Proposed Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (July 24, 2014)

- ACNM Issue Brief on FY 2015 Proposed Inpatient Prospective Payment System Regulation (May 30, 2014)

- ACNM Issue Brief on New Prospective Payment System for Federally Qualified Health Centers (May 30, 2014)

- ACNM Issue Brief on CMS Final Regulation Reducing Administrative Complexity and Burden in the Medicare Program (May 30, 2014)

- Section 180, Chapter 15, Medicare Benefits Policy Manual - outlining coverage for midwifery services under Medicare.

- Section 130, Chapter 12, Medicare Claims Processing Manual - outlining how payments are made for midwife services under Medicare.

- Medicare Physician Fee Look Up Tool - online tool to find Medicare allowable amount for any service paid under the physician fee schedule.

Advocacy

- Letter to CMS on requirement that physicians review all inpatient records for CNM patients in critical access hospitals (August 5, 2016)

- Letter to CMS on proposed changes to Medicare's Hospital Conditions of Participation (June 27, 2016)

- Letter to CMS on proposed CY 2016 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (September 8, 2015)

- Letter to CMS on physician review of CNM inpatients of critical access hospitals (March 19, 2015)

- Comments on the CY 2015 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (September 2, 2014)

- Comments on Physician Certification Issue in CY 2015 Medicare Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System Proposed Regulation (September 2, 2014)

- Letter to CMS regarding the proposed FY 2015 Medicare Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) regulation (June 30, 2014)

- H.

R. 4663, the "Protect Patient Access and Promote Hospital Efficiency Act" - An issue brief on physician certification of inpatient admissions.

R. 4663, the "Protect Patient Access and Promote Hospital Efficiency Act" - An issue brief on physician certification of inpatient admissions. - Letter to CMS regarding physician certification policy. (January 30, 2014)

Archives

American College of Nurse-Midwives

8403 Colesville Rd. Ste. 1230 Silver Spring, MD 20910

Phone: 240.485.1800 Fax: 240.485.1818

All rights reserved

Grief counseling: is it covered by Medicare?

admin

Contents

- Does Medicare cover grief counseling?

- What parts of Medicare does grief counseling cover?

- Part A

- Part B

- Part C (Medicare benefit)

- Part D

- Medicare Supplement (Medigap)

- What are the Medicare requirements for grief counseling?

- Qualifications

- Provider Requirements

- What is woe counseling?

- How much does a psychological consultation cost?

- Statement

- Both original Medicare (Parts A and B) and Medicare Advantage (Part C) cover mental health services, including those needed for grief counseling.

- Medicare Part A covers inpatient mental health services and Medicare Part B covers outpatient mental health services and partial hospitalization programs.

- Medicare covers depression screening, individual and group therapy, medications, and more.

Grief counseling, or bereavement counseling, is a mental health service that can help many people with grief.

Medicare covers most mental health services related to grief counseling for beneficiaries. These services may include:

- inpatient mental health services

- outpatient mental health services

- drugs

- partial hospitalization

you may need during the grieving process.

Does Medicare cover grief counseling?

Medicare covers a wide range of mental health services related to grief counseling.

Medicare Part A covers inpatient mental health services, and Medicare Part B covers outpatient and partial hospital services.

Medicare covers the following counseling services when you need them:

- family counseling

- group therapy

- individual psychotherapy

- laboratory and diagnostic tests

- medication management

- partial hospitalization

- psychiatric evaluations

- annual screenings for depression

A doctor or mental health professional can help you determine what counseling services can help you in your grief the greatest benefit.

When you are ready to start grief counseling, you can get services from the following Medicare-approved providers:

- Doctors

- Psychiatrists

- Clinical psychologists

- Clinical social workers

- Medical sisters-specialists

- Practices

- Assistants

- Consumacities

Medicare Parts A and B cover most grief counseling services. However, other parts of Medicare offer additional drug and out-of-pocket coverage.

However, other parts of Medicare offer additional drug and out-of-pocket coverage.

Find out more about how Medicare covers various grief counseling services below.

Part A

If you are hospitalized and need inpatient mental health services, you will be covered by Medicare Part A.

Part A covers inpatient grief counseling at a general hospital or psychiatric hospital. However, if your mental health services are provided in a psychiatric hospital, you only cover up to 190 days.

Part B

If you need outpatient mental health care or partial hospitalization, you will be covered by Medicare Part B.

Medicare Part B covers outpatient grief counseling services, such as:

- individual and group therapy

- drug management

- psychiatric evaluations

You can get these services at your doctor's office, at your health care provider's office , in a hospital outpatient department, or at a community mental health center.

Part B also covers partial hospitalization for grief counseling, which includes intensive daily care and counseling. However, Medicare only covers partial hospitalization programs provided by a community mental health center or hospital outpatient department.

Part C (Medicare Advantage)

Any mental health services covered by Medicare Parts A and B will also be covered by Medicare Part C (Medicare Advantage).

Many Medicare Advantage plans also offer prescription drug coverage. If you and your doctor decide that antidepressants or other medications will help you during grief counseling, your Advantage Plan may cover their costs.

Part D

If you need antidepressants or other prescription drugs as part of your mental health treatment, Medicare Part D will cover them.

Antidepressants, antipsychotics, and anticonvulsants are covered by Medicare Part D.

Additional drugs used during treatment may be covered by your Part D plan. But be sure to check your drug plan's Formulary (List of Covered Drugs) for more information about what is and is not covered.

But be sure to check your drug plan's Formulary (List of Covered Drugs) for more information about what is and is not covered.

Medicare Supplement (Medigap)

If you need help paying for some personal expenses related to your mental health services, Medigap can help you.

Medigap is Medicare supplemental insurance that helps cover various costs associated with your original Medicare (Parts A and B). This includes Part A and Part B:

- coinsurance

- copayments

- deductibles

Some Medigap plans also cover additional fees and expenses that you may incur while traveling overseas.

Before you buy a Medigap plan, you'll want to compare your coverage options to determine if adding a Medigap policy is worth it.

What are the Medicare requirements for grief counseling?

Medicare covers any medically necessary services related to the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of illness, including mental health problems.

Below are some of the requirements for getting counseling services from your Medicare plan.

Eligibility

You do not have to meet any special eligibility requirements to get Medicare counseling services.

Instead, you and your healthcare team will determine what mental health services you may need during your grieving process. These services may include counseling and group therapy, short-term antidepressants, and, in some cases, partial or total hospitalization.

Provider requirements

Medicare generally covers all behavioral health services if the provider is an approved participating provider.

Participating providers are those who accept Medicare prescriptions. This means that they have entered into a contract with Medicare to provide services to you as a beneficiary at a Medicare-approved rate.

Many Medicare-approved mental health providers accept a Medicare assignment. However, if you're unsure, you can always double-check them (and your plan) first.

Seeking help when you've had a loss

Grief is a personal but collective experience that we all have to go through in our lives.

Although the process of mourning is incredibly difficult, you do not have to go through it alone. Here are some resources to find professional help when you're grieving:

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA). SAMHSA is a national mental health resource with a 24-hour helpline that you can use to find grief support services in your area.

- American Counseling Association (ACA). ACA has an entire page dedicated to articles, magazines, and other specific resources for people who are grieving.

- GriefShare. GriefShare is an organization that hosts weekly support groups across the country. Its website has a group finder tool to help you find groups in your area.

You can also contact your Medicare plan directly to find a therapist or other mental health professional who specializes in grief counseling in your area.

What is grief counseling?

Grief counseling, also called bereavement counseling, can help people go through the grief process. While grief counseling often involves the loss of a loved one, people can also mourn other major life changes, such as the loss of a relationship or job.

Grief counseling may include services such as:

- individual counseling services

- group counseling services

- grief support groups

- community outreach programs

- home visits and checks

- medications when needed

Any qualified mental health professional can guide you through the grief process, but some specialize in mental health conditions that often accompany grief, such as depression and anxiety.

Regardless of which treatment path you choose, working with a mental health professional can help you get the support you need during your grieving process.

How much does a psychological consultation cost?

Even if you get mental health services through your Medicare plan, you may still need to pay some out-of-pocket costs for your care.

These costs may include:

- Premium for Part A up to $458 per month

- Part A deductible of $1,408 per benefit period

- Coinsurance for Part A of $352 or more per day after 60 days

- Part B premium of $144.60 or more per month

- Part B deductible $198 per year

- Part B co-insurance equal to 20 percent of Medicare approved amount.

- Part C premium, deductible, drug premium, and drug deductible

- Part D premium and deductible

- Medigap Premium

The cost of Parts C, D, and Medigap depends on the type of plan and coverage your plan, among other factors.

If you do not have Medicare or any other health insurance, you will have to pay all out-of-pocket expenses for grief counseling.

According to Thervo, grief counseling can cost up to $150 per session on average. Additionally, individual therapy sessions can cost $70 to $150 per session, while group therapy costs $30 to $80 per session on average.

Depending on where you live, you can find low-cost or free mental health groups in your area. Contact your local health department for more information about potential groups near you.

Conclusion

- For Medicare recipients, most grief counseling services, including individual therapy, group therapy, etc., are covered by original Medicare (Parts A and B) and Medicare Advantage (Part C).

- Adding a Medicare prescription drug plan and, in some cases, a Medigap plan may offer additional coverage and help pay for grief counseling services and costs.

- If you need grief counseling or any other mental health services, the first step is to contact your PCP. They can refer you to a mental health professional who can help you get the support you need.

US Health

The basic principle behind the US health care model is that health care is a private good, and therefore a commodity that can be bought or sold. Therefore, the States today are record holders in terms of prices and costs of medical care. The sector is growing rapidly, attracting capital, labor and brains. By the end of the pandemic, it is likely to approach a third of GDP. But it is COVID-19, like a litmus test, pointed to the Achilles' heel of the system: the seemingly most powerful medicine in the world reeled, faced with a virtual existential crisis (the country leads the sad statistics in terms of the number of cases of infection and victims).

The sector is growing rapidly, attracting capital, labor and brains. By the end of the pandemic, it is likely to approach a third of GDP. But it is COVID-19, like a litmus test, pointed to the Achilles' heel of the system: the seemingly most powerful medicine in the world reeled, faced with a virtual existential crisis (the country leads the sad statistics in terms of the number of cases of infection and victims).

If you don't have health insurance, will you die on the street?

There is a myth that poor people in the US who don't have health insurance almost die on the streets because they can't see a doctor.

In fact, the government in the United States pays 52% of all health care costs, so this system cannot be considered completely private, as is often said.

Because of this, in fact, there are a lot of problems in the American healthcare system. The biggest one is related to costs. They are rather poorly controlled, primarily due to a combination of insurance premiums and government reimbursement. It turns out that the consumer does not fully pay for his own medical care: only 13 cents of every dollar in the United States goes directly from the consumer's pocket, and the costs cannot be controlled. This is significantly less than in most single payer countries, such as France or Switzerland.

It turns out that the consumer does not fully pay for his own medical care: only 13 cents of every dollar in the United States goes directly from the consumer's pocket, and the costs cannot be controlled. This is significantly less than in most single payer countries, such as France or Switzerland.

9.5% share of employed in health care of all employed in the economy.

In fact, health care provides a well-paid job for every 11th American.

How does universal health coverage work?

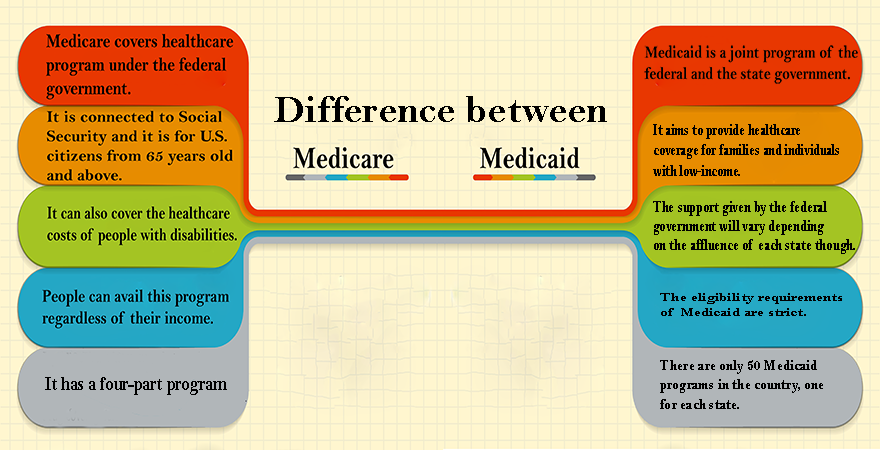

The US healthcare system is a combination of public and private, commercial and nonprofit insurance companies and health care providers. The federal government funds the national Medicare program for adults aged 65 and over and certain people with disabilities, as well as various programs for veterans and low-income people, including Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP). The government manages and pays for some aspects of local insurance coverage and the social safety net. Private insurance (the main form in the US) is provided primarily by employers.

Private insurance (the main form in the US) is provided primarily by employers.

There is no universal health insurance in the US. In 2010, the landmark Affordable Care Act was passed. Already in 2019, more than 92% of the population was covered by various types of insurance, and only 27.5 million people (8.5%) did not have insurance. Public and private insurers set their own benefit packages and cost-sharing structures under federal and state law.

Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded the government's role in financing and regulating health care. The ACA has established a shared responsibility between government, employers, and individuals to ensure that all Americans have access to quality health insurance.

Main components of the ACA:

- requirement for most Americans to get health insurance or pay a fine (repealed under Trump),

- expanding coverage for young people by allowing them to stay in their parents' plans until they are 26,

- Opening health insurance markets or exchanges that offer premium subsidies to low- and middle-income individuals,

- Expanding Medicaid eligibility with federal grants (in states that have chosen this option).

The ACA includes 10 mandatory categories, or "core health benefits": outpatient care (physician visits), emergency services, hospitalizations, maternity and newborn care, mental health and drug treatment services, prescription drugs, rehabilitation services and devices , laboratory services, preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management, pediatric services, including dental and eye care services.

$11,172 is 2019 annual per capita health care spending. The highest in the world; grow by 4.2–5.8% annually over the past five years.

There are insurance plans. And what about freedom of choice?

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services are the government's largest source of health insurance funding.

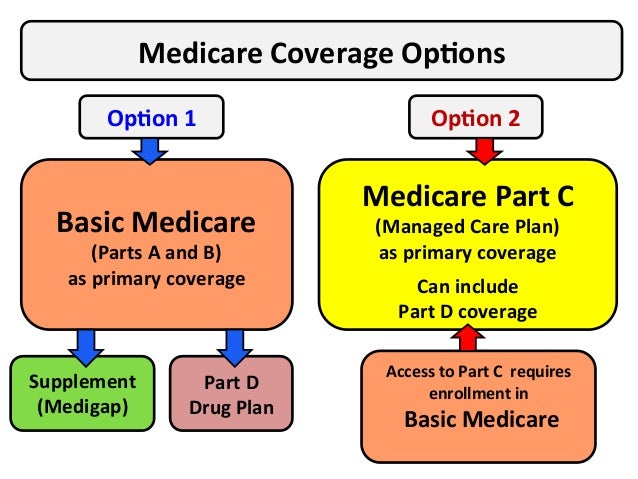

Medicare. In addition to universal entitlement to health care for people aged 65 and over, Medicare guarantees eligibility for people under 65 with a chronic disability or end-stage renal disease. All beneficiaries are eligible for traditional Medicare, a fee-for-service program provided by hospital insurance (Part A) and health insurance (Part B). There is also a Medicare Advantage (Part C) option that enrolls people in a private health care organization (HMO) or a managed care organization.

All beneficiaries are eligible for traditional Medicare, a fee-for-service program provided by hospital insurance (Part A) and health insurance (Part B). There is also a Medicare Advantage (Part C) option that enrolls people in a private health care organization (HMO) or a managed care organization.

One in three Medicare recipients in 2019 chose to get coverage through a private Medicare Advantage health plan.

Part D has been added to Medicare since 2003 to help get outpatient prescription drugs.

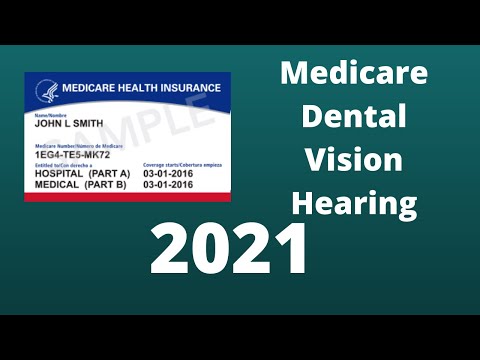

So people with Medicare are eligible for inpatient hospital care (Part A), which includes hospice and short term care in a skilled nursing facility. Part B covers physician services, durable medical equipment, and home health services, and only limited outpatient benefits for prescription drugs, including injections or infusions, that must be administered by a health worker in an outpatient clinic. Medicare covers short-term postpartum care, such as rehab services in a skilled nursing facility or home, but not long-term care.

Dental and eye care coverage is limited, and most beneficiaries do not have coverage for dental care.

Medicare is funded by a combination of general federal taxes, a mandatory payroll tax paid by hospital insurance, and individual contributions.

Medicaid. The program first enabled states to receive federal funding to provide health care services to low-income families, the blind, and people with disabilities. Gradually, insurance became mandatory for pregnant women and babies from low-income families, and then for children under 18 years of age.

Today Medicaid covers 17.9% of Americans. Because this is a state-run, means-tested program, eligibility varies by state.

Individuals must apply for Medicaid coverage and re-enroll and reassess each year. As of 2019, more than two-thirds of Medicaid recipients were enrolled in managed care organizations.

Consistent with federal guidelines, Medicaid covers a wide range of services, including inpatient and outpatient hospital services, long-term care, laboratory and diagnostic services, family planning, nursing midwives, autonomous birth centers, and transportation costs.

States may offer additional benefits, including physical therapy, dental, and vision services. Most states (39 as of 2019) provide dental care.

Medicaid is primarily funded by taxes, with federal tax revenues accounting for two-thirds (63%) of costs and state and local revenues the remainder. The expansion of Medicaid under the ACA was fully funded by the federal government until 2017, after which the share of federal funding gradually decreased to 90%.

CHIP is a children's health insurance program. Operated since 1997 as a government program for low-income children who earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but are unlikely to be able to afford private insurance. Today the program covers 9.6 million children. It operates as an extension of Medicaid in some states, and as a separate program in others.

CHIP is funded by grants from the federal government to the states. Most states (30 in 2019year) collect insurance premiums under this program.

The role of private health insurance. Spending on private health insurance accounted for one third (34%) of total health spending in 2019.

Private insurance is the primary health insurance for two-thirds of Americans (67%).

Most private insurance (55%) is sponsored by the employer, a smaller share (11%) is purchased by individuals from for-profit and non-profit companies.

Most employers contract with private health plans to manage benefits. Most employer plans cover medical expenses for employees and their dependents, and there are often several plans to choose from. Usually, contributions are paid by both employers and employees, much less often, insurance premiums are fully covered by the employer.

The ACA has launched the HealthCare.gov federal marketplace for purchasing individual primary health or dental insurance through private plans. The state can also create its own trading platforms.

Medicaid beneficiaries may receive their benefits through a private health care organization that receives capitated (capitation), usually risk-adjusted, payments from state Medicaid departments. More than two-thirds of Medicaid beneficiaries are covered by managed care.

Uninsured individuals have access to emergency care under federal law that requires most hospitals to treat all patients in need of emergency care, including women in labor, regardless of ability to pay, insurance status, national origin, or race. As a consequence, private service providers are an important source of philanthropy and grants.

The US healthcare system is facing two major challenges amid the spread of the coronavirus: lack of medical equipment and lack of insurance for millions of Americans.

17.1% of GDP is health care spending in the US.

6.2% of GDP is the gross value added created by healthcare.

For comparison: GVA equal to 7. 6% of GDP is created by the entire US financial sector: banks, insurers, management companies and pension funds.

6% of GDP is created by the entire US financial sector: banks, insurers, management companies and pension funds.

23.3% of GDP is the direct contribution of healthcare to the economy.

Not easy to learn and not easy to fight!

Education and personnel. Most medical schools (59%) are public.

The median cost of tuition in public medical schools in 2019 was $39,153 and in private schools it was $62,529. 73% graduate with $200,000 in health care debt (2019)), including pre-medical education.

Several government debt reduction, loan forgiveness and stipend programs are offered; many targeted internships in underserved regions. Health care providers practicing in states where there is a shortage of medical professionals are eligible for Medicare Physician Premium Payments.

Primary care. Approximately one third of all professionally active physicians are primary care physicians, a category that includes specialists in family medicine, general practice, internal medicine, pediatrics and geriatrics. Approximately half of primary care physicians in 2019year accounted for therapists; more often they are general practitioners rather than family physicians.

Approximately half of primary care physicians in 2019year accounted for therapists; more often they are general practitioners rather than family physicians.

Primary care physicians are paid by a variety of methods, including contractual fees (private insurance), capitation payments (private insurance and some public insurance), and administrative fees (public insurance).

66% of primary health care practice income comes from service fees.

Medicare is experimenting with alternative payment models for primary care providers and specialists.

Outpatient care. Specialists can work both in private practice and in hospitals. Specialist practices are increasingly integrated with hospital systems as well as with each other. Most specialists are engaged in group practices, most often specialized group practices.

Outpatient professionals have the right to choose which form of patient insurance they accept. Not everyone accepts publicly insured patients due to the relatively lower reimbursement rates mandated by Medicaid and Medicare. Therefore, access to specialists for the beneficiaries of these programs - not to mention people without any insurance - in the States is sometimes limited.

Not everyone accepts publicly insured patients due to the relatively lower reimbursement rates mandated by Medicaid and Medicare. Therefore, access to specialists for the beneficiaries of these programs - not to mention people without any insurance - in the States is sometimes limited.

Administrative Arrangements for Direct Patient Payments to Providers: Physician visit fees are usually paid at the time of service or billed to the patient at a later date. Some insurance plans and products (including health savings accounts) require patients to file claims in order to receive reimbursement.

Providers bill insurers by coding the services rendered. There are thousands of codes, which makes this process laborious; providers usually employ coding and billing staff.

Due to administrative hurdles, a small number of providers do not accept any insurance. Instead, they only accept cash payments or require annual or monthly upfront payments to providers for "concierge medicine" that offers enhanced access to services.

Out-of-hours assistance. Primary care physicians are not required to provide or schedule out-of-hours appointments for their registered patients.

In 2019, 45% of primary care physicians worked after hours: 38% of them provided care in the evenings and 41% on weekends.

Out of office hours, private emergency centers or clinics are increasingly available, which typically serve younger, healthier people who require occasional care and may not have a primary care provider.

Hospitals. Institutions have the freedom to choose what insurance they accept (most under Medicare and Medicaid). Hospitals are paid in several ways. Medicare pays DRG rates, which do not include physician fees. Medicaid pays on a DRG, per diem, or reimbursement basis, with states having considerable latitude in setting hospital payment rates. Private insurers pay hospitals, usually per diem, which is usually negotiated between each hospital and its insurers on an annual basis.

In 2019, 57% of the 5,198 acute care hospitals in the US were nonprofits; 25% - commercial, 19% - state. In addition, 209 federal state hospitals were operating.

Is medical assistance a right or a privilege?

The Trump administration made changes to Medicare and Medicaid. First of all, the regulation on primary health care, a new model of voluntary payments aimed at simplifying the payment for the services of primary health care doctors, which is planned to be launched in 2021. In addition, as of 2018, several states have introduced a requirement for able-bodied individuals to document that they meet the minimum job requirements to be eligible for Medicaid.

Changes made to the Affordable Care Act. In particular, some measures to protect consumers through regulatory and executive actions have been abolished: for example, an individual mandate, a financial penalty for not having health insurance.

Trump Plan: Eliminate the penalty for refusing to purchase insurance and reduce the price of insurance plans by up to 60%, ensure transparency in pricing, protect patients with chronic diseases, and allow the export of more affordable drugs from Canada.

The administration has allowed states to offer alternative, lower cost, minimally regulated insurance plans that may not meet ACA requirements.

The White House also announced efforts to reduce high healthcare costs, especially prescription drugs. Two bills passed in 2018 remove provisions that prevented pharmacists from informing customers when the out-of-pocket price of a drug (not including insurance) is lower than the price stipulated in the insurance contract. In addition, to ensure transparency of hospital prices, federal regulations require all hospitals to post their payments for medical procedures online and update the list at least once a year.

Over the past few years, employers that provide health insurance to about half of Americans have taken steps to reduce health care costs by removing intermediaries such as insurance companies and pharmaceutical benefit managers from the health care funding chain. Some larger employers have teamed up to form their own not-for-profit healthcare corporations, one notable example being the joint venture between Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway and JP Morgan. Other firms, such as Apple, hire health care providers directly, including employees at local clinics.

Other firms, such as Apple, hire health care providers directly, including employees at local clinics.

Pandemic and System Transformation

US healthcare is learning from the crisis, assessing weaknesses, and building a model for change today.

As the epidemiological situation worsened, medical services could be seen being provided in places that were previously intended for other purposes: parks turned into field hospitals, parking lots into diagnostic testing centers. The Army Corps of Engineers even drew up plans to convert hotels and hostels into hospitals. New protocols have been developed to accommodate multiple patients on a single ventilator.

Parks, car parks and hotels will certainly return to normal. But pre-Covid medical practice will undergo the most significant changes.

The future of telemedicine. Before the crisis, some major players in the healthcare system began to develop telemedicine services. However, its use across the country was limited. The inactivity of many providers was due to restrictions on reimbursement for such services and fears that their expansion would jeopardize the quality and even the very fact of continued relationships with patients who may turn to new sources of online treatment.

However, its use across the country was limited. The inactivity of many providers was due to restrictions on reimbursement for such services and fears that their expansion would jeopardize the quality and even the very fact of continued relationships with patients who may turn to new sources of online treatment.

Indeed, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have previously restricted providers' ability to receive payment for telehealth services, but have expanded coverage during the pandemic. As is often the case, many private insurers have followed CMS' lead. To support this growth and strengthen the medical workforce in regions hardest hit by the virus, state and federal governments have removed the requirement for doctors to obtain a separate license in the state in which they practice. Telemedicine company Teladoc Health soon reported a 50% weekly increase in visits. But most importantly, doctors in hospitals and offices, traditionally preferring live visits to patients, in conditions of social isolation, managed to “taste” telemedicine.

For the health care system to really kick-start change, physicians and clinics need to understand that telemedicine is just a convenient technology for delivering care, not some inferior substitute for face-to-face contact. The experience gained during the pandemic will work to change consciousness. Another question is whether telemedicine services will be fairly compensated after the crisis is over. CMS is now committed to easing reimbursement restrictions “for the duration of the COVID-19 public health emergency.". Nevertheless, there is strong evidence that the changes will take hold and the new model will become an integral part of the modern US healthcare system.

An extension of the term "health care provider". Prior to the corona crisis, healthcare workers experienced high and rising levels of burnout. This trend was fueled by the need for physicians to address the many non-clinical problems associated with the so-called "social determinants of health" of patients - illiteracy, lack of housing, a personal vehicle, and even food. A recent study published in the Journal of the American Council of Family Medicine found that physicians who considered their clinic to have a high ability to meet the social needs of patients had significantly lower levels of burnout.

A recent study published in the Journal of the American Council of Family Medicine found that physicians who considered their clinic to have a high ability to meet the social needs of patients had significantly lower levels of burnout.

The pandemic has caused an uptick in demand for medical care, while at the same time reducing opportunities as healthcare workers themselves become infected with the virus. And since the families of hospitalized patients cannot visit their loved ones in the hospital, the role of the so-called caregiver is expanding.

The growing mismatch between the needs of patients and the capabilities of health care providers defines one of the most common weaknesses in the US healthcare system.

To expand capacity, hospitals have reassigned doctors and nurses who were previously involved in routine care to help patients with COVID-19. Similarly, non-clinical staff were forced to help triage patients, and fourth-year medical students were given an unprecedented opportunity to graduate early and join colleagues on the front lines. The government has temporarily allowed nurse practitioners, paramedics, and certified nurse anesthetists to perform additional functions without a physician's supervision.

The government has temporarily allowed nurse practitioners, paramedics, and certified nurse anesthetists to perform additional functions without a physician's supervision.

The rapidly growing demand for the collection and processing of test specimens has created a surge in demand for medical personnel needed to perform diagnostics. Non-profit and military organizations sent employees and volunteers to conduct clinical research. And, of course, the need for skilled home care and additional health workers has grown exponentially.

Even allowing for the fact that the need for additional staff will decrease when the crisis subsides, there remain numerous public health and above all social needs that have been beyond the capacity of current health care providers for many years.

The US healthcare system will need to build a workforce to meet the growing social needs of patients.

One way to address the problem may be to provide important aspects of care to those who do not have a clinical degree. For example, laid-off social service workers receive the necessary training and access to the medical profession. Already today, the Live Better U Walmart program subsidizes health education for laid-off store employees. In addition, high school or college graduates could gain a few years of experience before taking important steps in their education. This group could not only mobilize in acute moments of a national crisis, but also in calmer periods would support the health care system in meeting the social needs of patients suffering from untreated chronic diseases.

For example, laid-off social service workers receive the necessary training and access to the medical profession. Already today, the Live Better U Walmart program subsidizes health education for laid-off store employees. In addition, high school or college graduates could gain a few years of experience before taking important steps in their education. This group could not only mobilize in acute moments of a national crisis, but also in calmer periods would support the health care system in meeting the social needs of patients suffering from untreated chronic diseases.

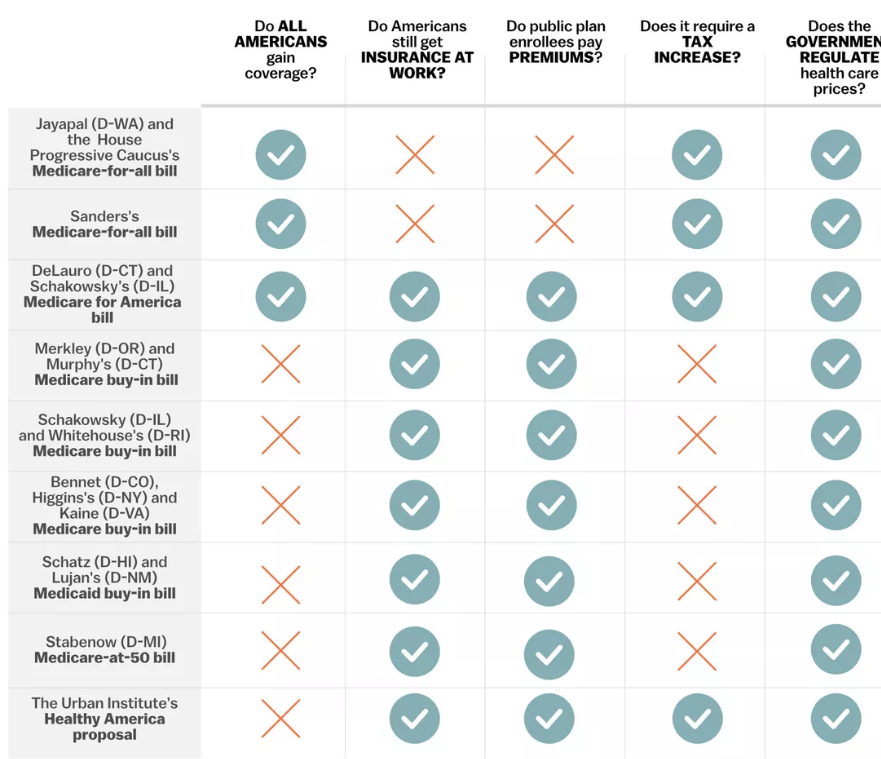

New health insurance model. Even before the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010, the debate about health care reform focused on two topics: how to increase access to insurance coverage and how to pay health care providers. The first question led to a broad debate about the Medicare program and the creation of a "public opportunity" to compete with private insurers. The second revolved around the question of whether the prevailing and deficient fee-for-service reimbursement system should be replaced with an approach where providers are paid based on their efficiency and completeness in meeting patients' medical needs. Ten years after the adoption of the ACA, the US system has made only a slow drift at best in addressing these fundamental problems.

Ten years after the adoption of the ACA, the US system has made only a slow drift at best in addressing these fundamental problems.

The pandemic has exposed another inadequacy of the current health insurance system: it is based on the assumption that, at any given time, a limited and calculated portion of the population will need a well-known or predictable combination of health services. Thus, forecasting needs for assistance is considered to be a stable and routine activity.

Suddenly it became clear that the health insurance model was not designed to cover the costs of healthcare during a massive pandemic, when patients with acute need see doctors in large numbers and at an unprecedented speed.

In a system that included many billing codes, including, for example, a special code for the treatment of a patient who "was injured while knitting or crocheting", no payment method was found for such critical actions like acquiring personal protective equipment and even ventilators, turning lobbies into hospital rooms, supporting patients taking their last breath, or colleagues who become powerless witnesses to unprecedented patient despair. Taken together, these actions are only illustrative parts of the true “unfunded mandate” of the health system.

Taken together, these actions are only illustrative parts of the true “unfunded mandate” of the health system.

Most insurers are now moving to models that temporarily exempt patients from co-pays and deductibles and guarantee coverage for all COVID-19-related costs. More difficult is the cost that hospitals face when it cannot be fully attributed to any one patient. A reasonable approach is that insurers provide hospitals with global payments that roughly reflect the monthly amounts paid out in recent years. This will allow much-needed cash to be transferred to clinics whose regular sources of income have simply evaporated at a time when they have had to operate far beyond their capacity.

And even such measures are just a band-aid applied to a deep wound in a system that does nothing to insure patients at times when the risks to their health are at a very high level. Eliminating this vulnerability does not necessarily require moving to universal coverage such as Medicare for All.