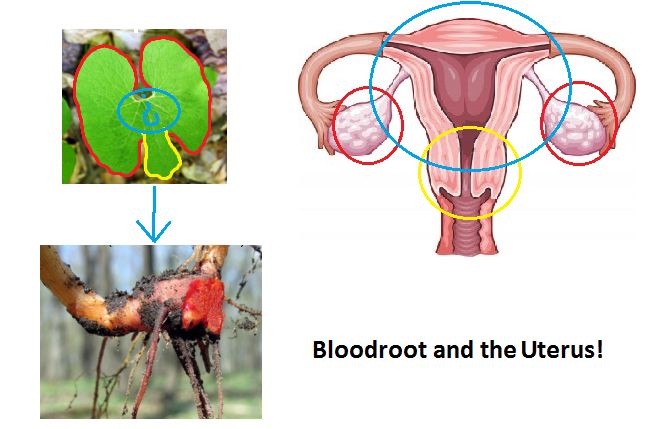

Where does uterus sit

Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Female Pelvic Cavity - StatPearls

Introduction

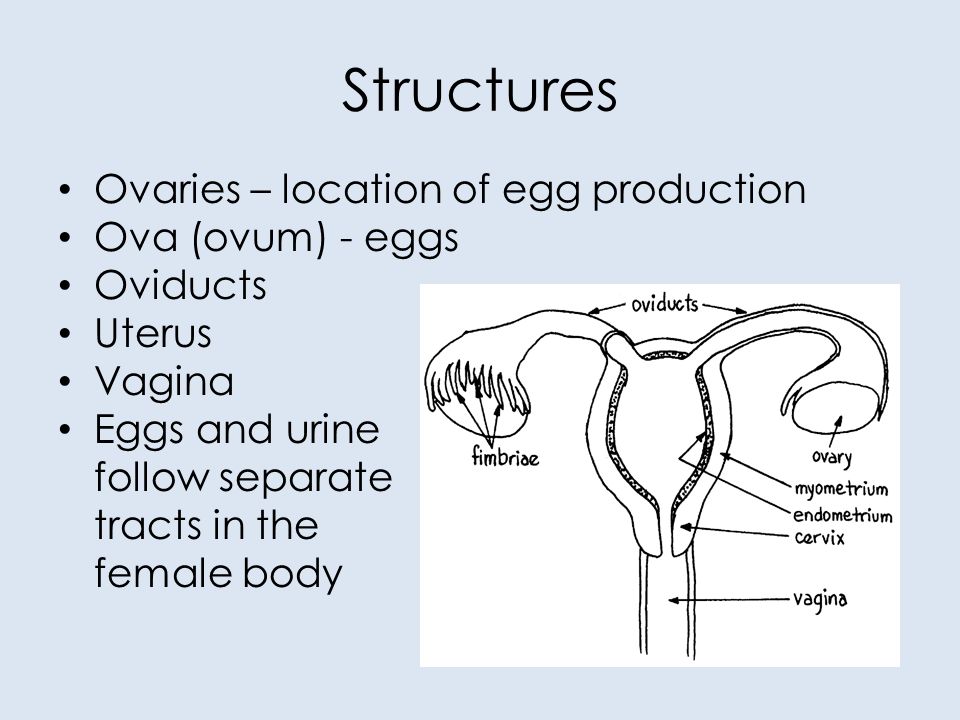

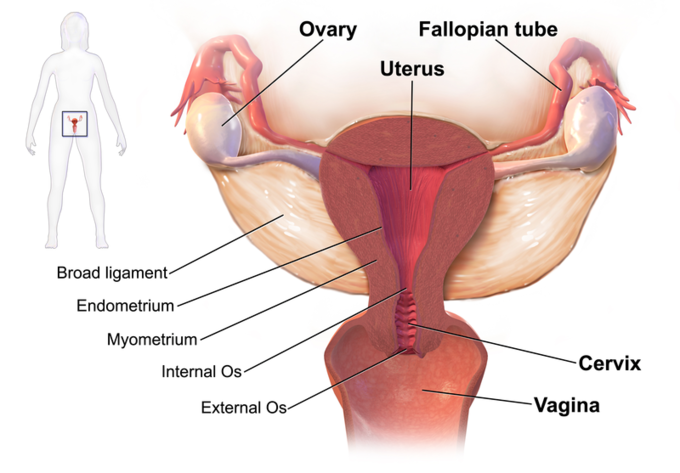

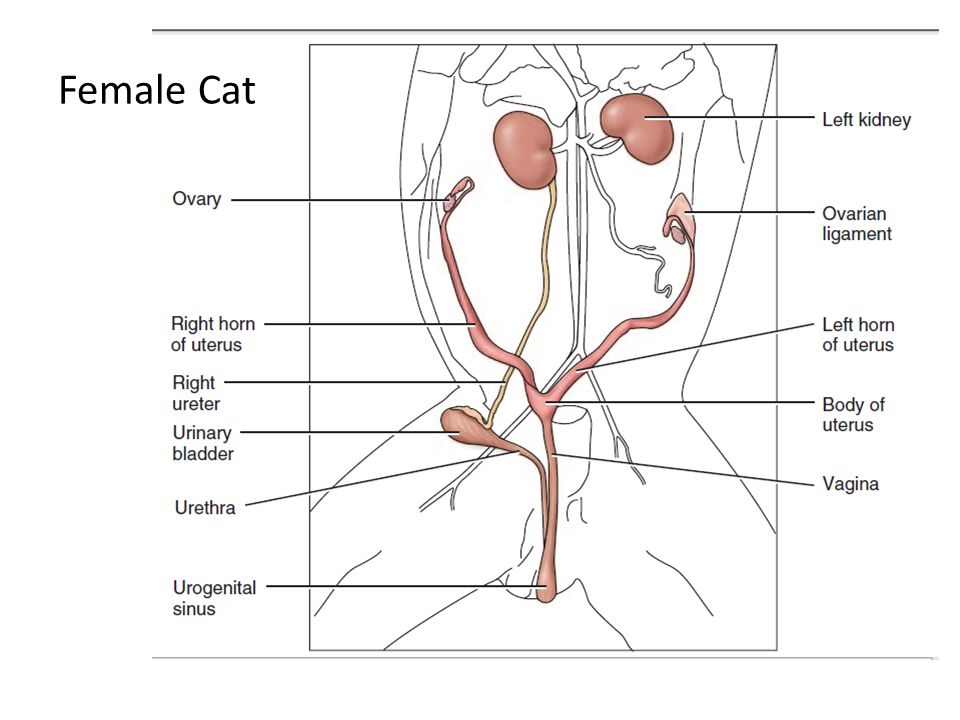

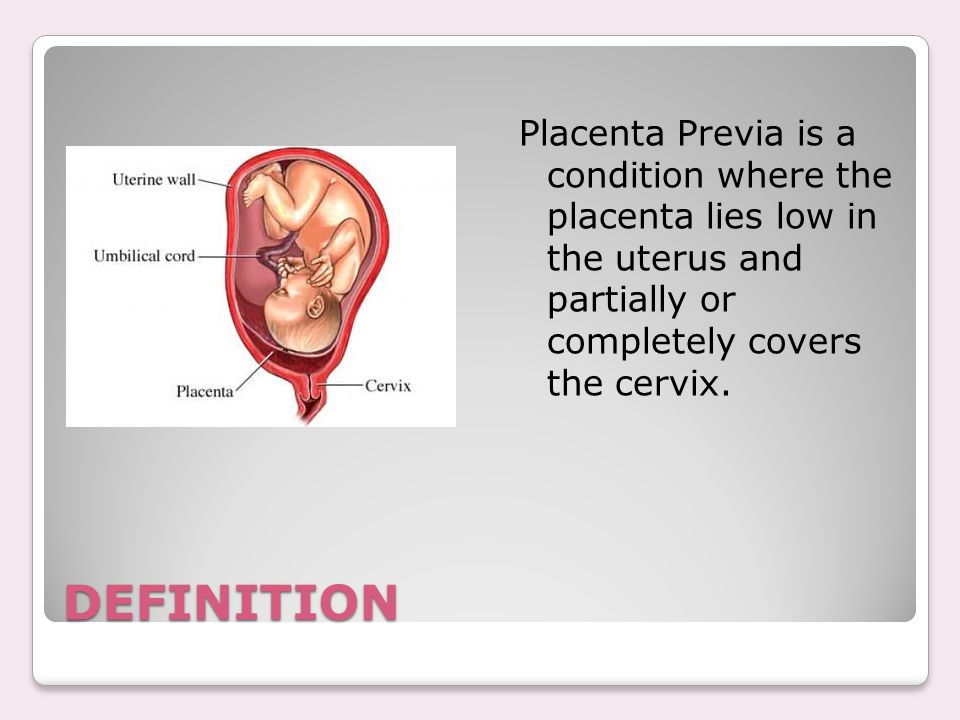

The pelvic cavity is a bowl-like structure that sits below the abdominal cavity. The true pelvis, or lesser pelvis, lies below the pelvic brim (Figure 1). This landmark begins at the level of the sacral promontory posteriorly and the pubic symphysis anteriorly. The space below contains the bladder, rectum, and part of the descending colon. In females, the pelvis also houses the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. Knowledge of anatomy unique to females is essential for all clinicians, especially those in the field of obstetrics and gynecology.

Structure and Function

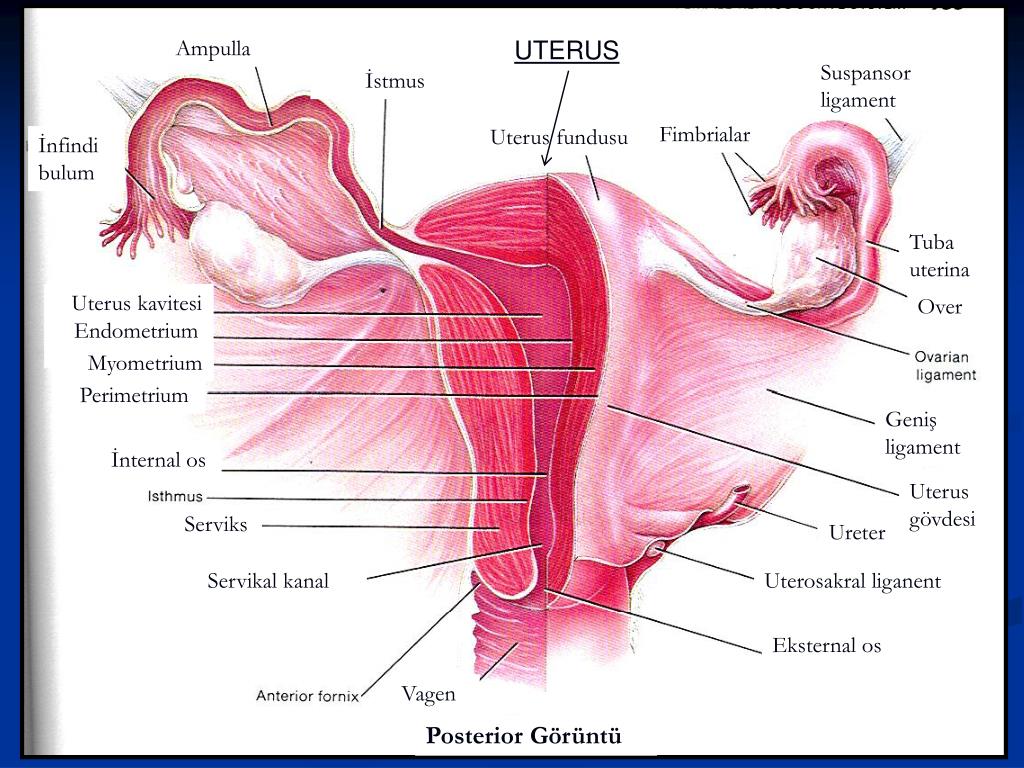

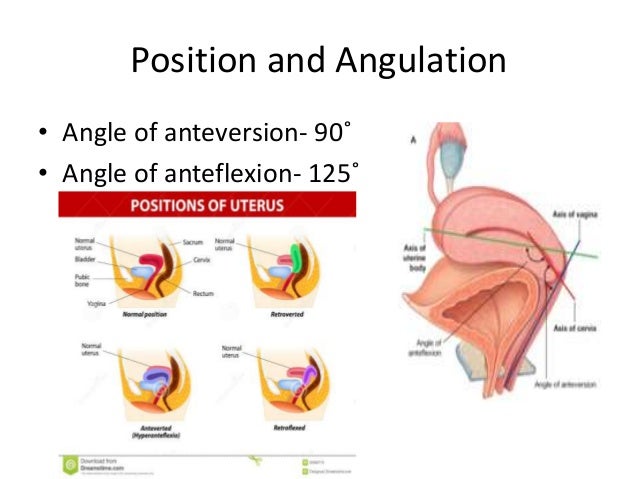

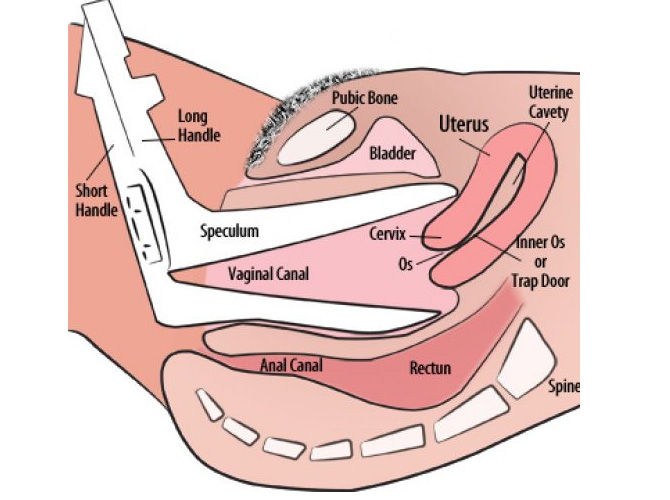

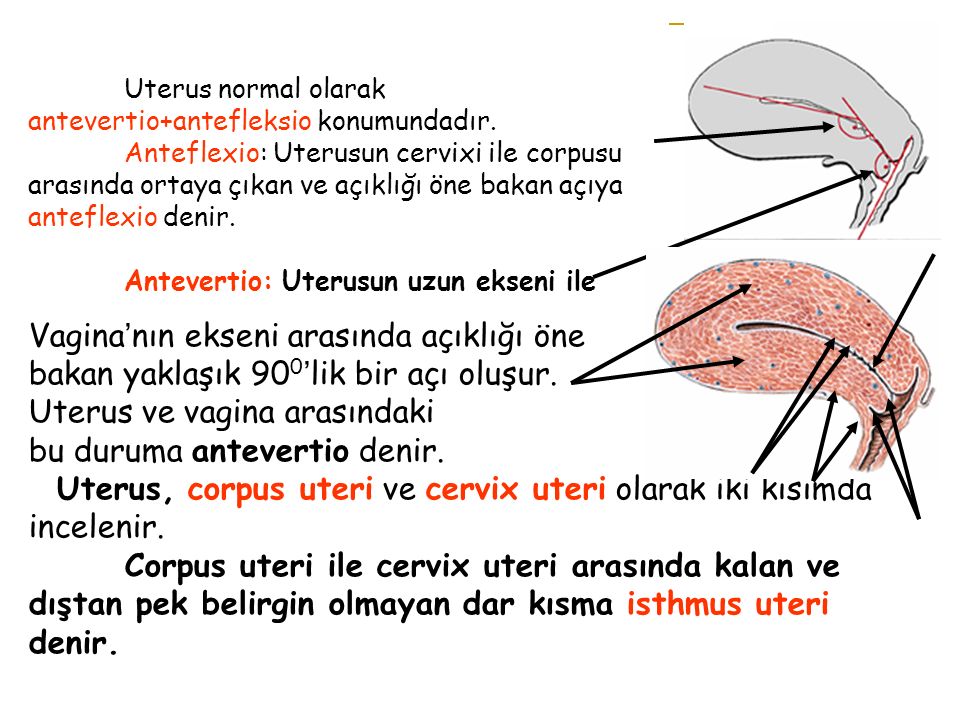

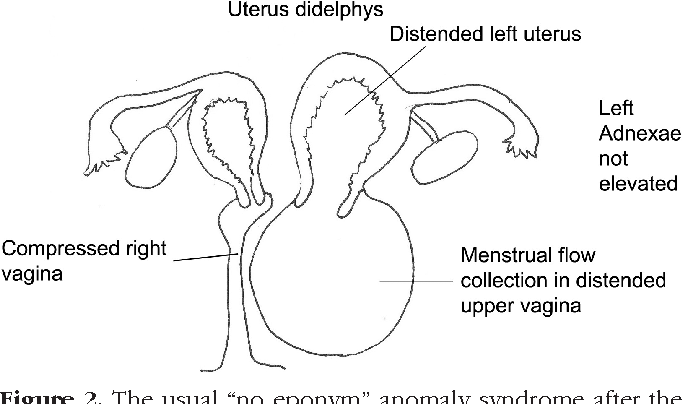

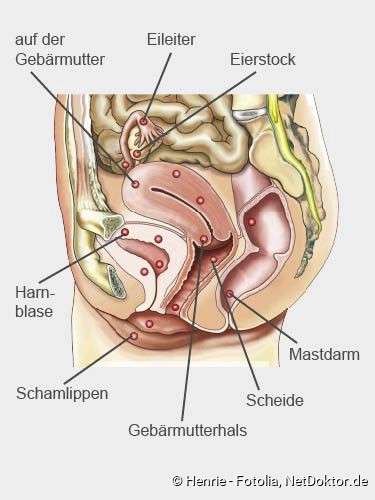

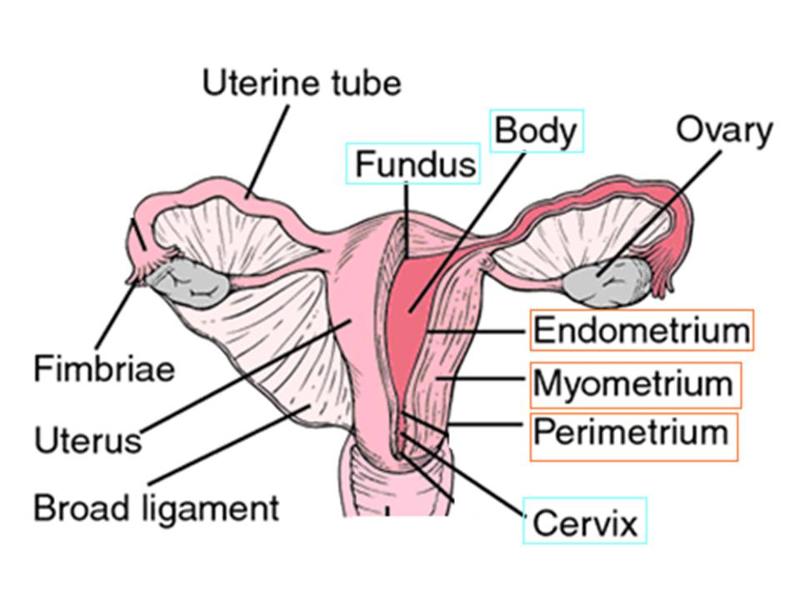

The uterus sits in the center of the female pelvic cavity (Figure 2.) The most common position of the uterus in the pelvic cavity is anteverted and anteflexed.[1] "Version" refers to the angle between the cervix and the vagina. An anteverted uterus appears "tipped forward" in the pelvic cavity. A retroverted uterus is "tipped backward. " Retroversion is a normal variant but can lead to dyspareunia. Additionally, retroversion of a gravid uterus correlates with higher rates of vaginal bleeding and spontaneous abortion.[2]

"Flexion" is the term for the angle between the cervix and uterine body. Anteflexed means the uterus is bent forward. Retroflexed means the uterus bends backward. Occasionally, retroflexion is seen after cesarean section and may be due to scar tissue that attaches the uterine body to the abdominal wall, causing the fundus to bend posteriorly.[3] However, the data supporting this theory is limited.

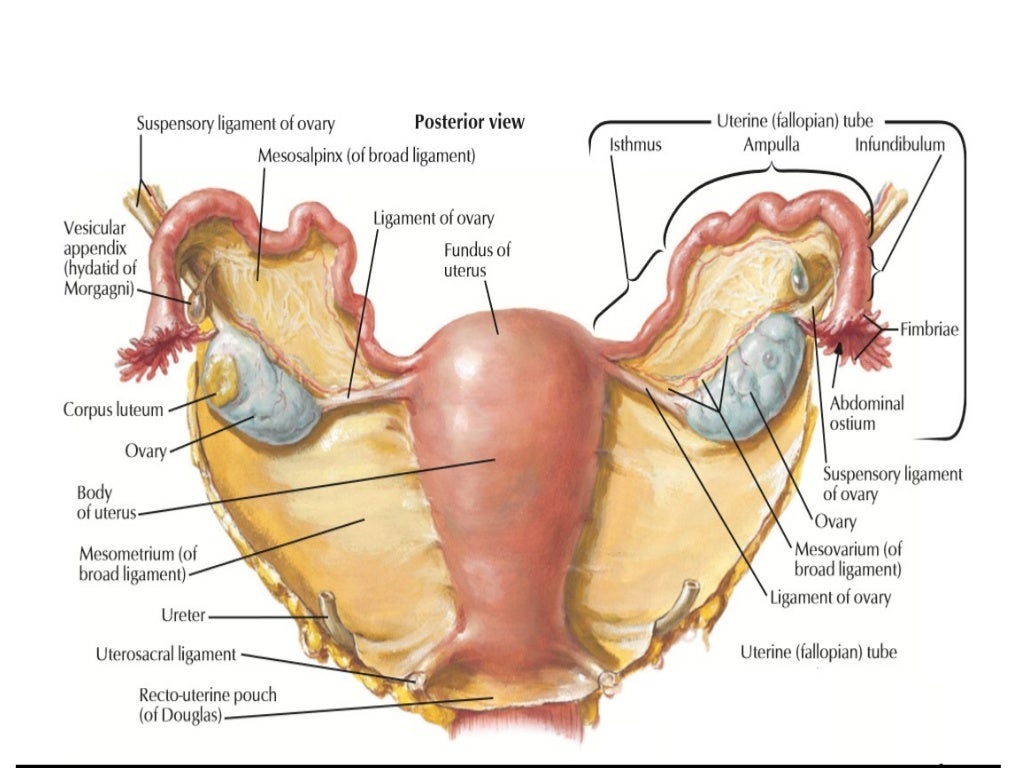

Anterior to the uterus is the bladder, with rectum located posteriorly. Between the uterus and the rectum is the recto-uterine space, also known as the posterior cul-de-sac. It is a potential space prone to fluid collection. Small amounts of physiologic fluid accumulate during ovulation and menses. Pathologic causes of fluid collection in the recto-uterine pouch include pelvic abscesses, drop metastasis from gastrointestinal malignancies, and endometriosis. In certain situations, if fluid accumulation is severe, this space can be drained by performing a culdocentesis, which is accomplished by inserting a needle through the posterior fornix of the upper vagina to access the posterior cul-de-sac.

In certain situations, if fluid accumulation is severe, this space can be drained by performing a culdocentesis, which is accomplished by inserting a needle through the posterior fornix of the upper vagina to access the posterior cul-de-sac.

The posterior cul-de-sac communicates with the retroperitoneal space of the abdomen via the right and left epiploic gutters. The right gutter leads to the hepatorenal space, also known as Morrison's pouch. The right epiploic gutter also allows the spread of pelvic pathogens into the subphrenic space. Occasionally infection of the subphrenic space can occur, leading to adhesions on the capsule of the liver. This pathology is known as Fitz-Curtis-Hugh syndrome or gonococcal perihepatitis.

The left epiploic gutter leads to the splenorenal pouch. Due to the leftward position of the rectum, pelvic pathology is less likely to spread to the abdomen via the left epiploic communication.[4]

Embryology

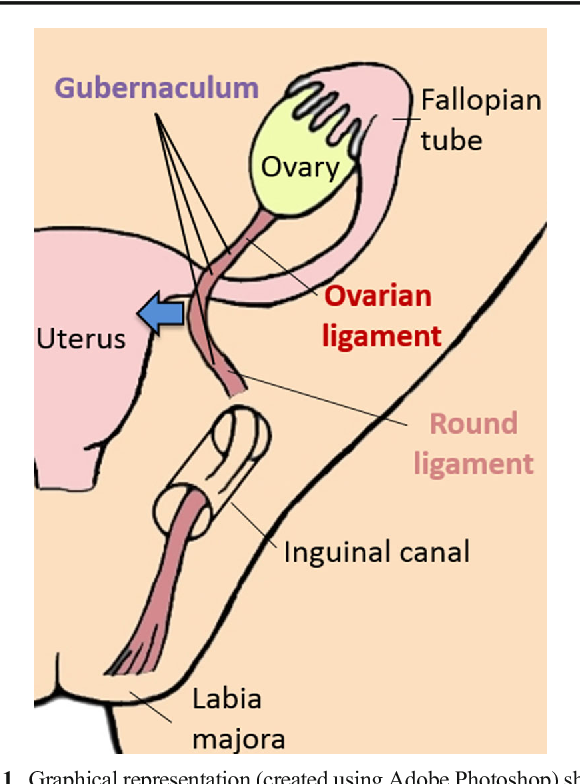

The organs of the female reproductive tract each have a unique embryological origin. The exact embryological timeline in which these organs develop is still open to debate because most embryologic studies use animal models with different gestational ages. However, there is a consensus that the ovaries are the first to develop. They arise from the surface of the mesonephros at the gonadal ridge.[5] Later in development, the ovaries descend into the pelvis with guidance from the gubernaculum. The inferior aspect of the gubernaculum subsequently becomes the round ligament of the uterus and terminates at the labia majora.

The exact embryological timeline in which these organs develop is still open to debate because most embryologic studies use animal models with different gestational ages. However, there is a consensus that the ovaries are the first to develop. They arise from the surface of the mesonephros at the gonadal ridge.[5] Later in development, the ovaries descend into the pelvis with guidance from the gubernaculum. The inferior aspect of the gubernaculum subsequently becomes the round ligament of the uterus and terminates at the labia majora.

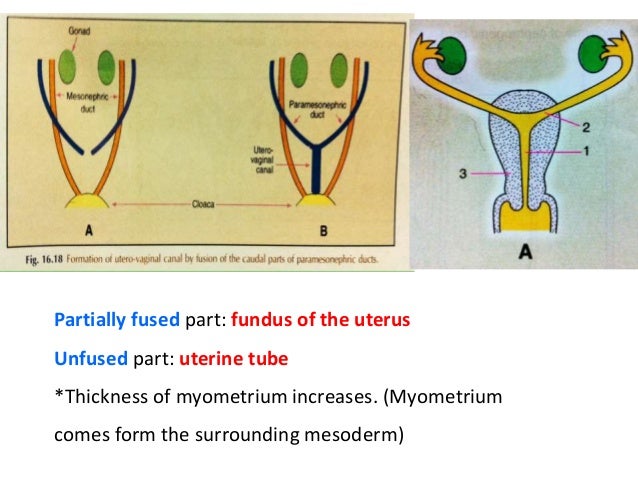

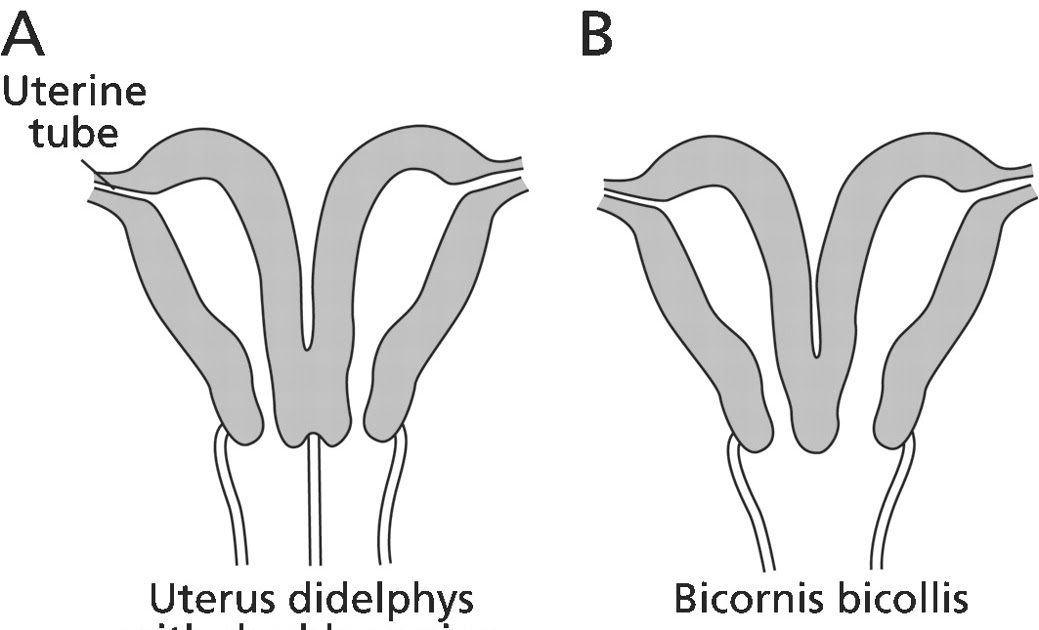

In females, the absence of a Y chromosome allows the uterus to form. It derives from the Müllerian ducts, also known as the paramesonephric ducts. These ducts fuse to form the uterus, fallopian tubes, and cervix. Some studies suggest that the paramesonephric ducts also give rise to the upper vagina while other studies indicate that the vagina exclusively derives from the urogenital sinus epithelium.[6] In males, a substance coded for on the Y chromosome, known as the anti-Mullerian hormone, prevents the formation of internal female reproductive organs.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Arterial

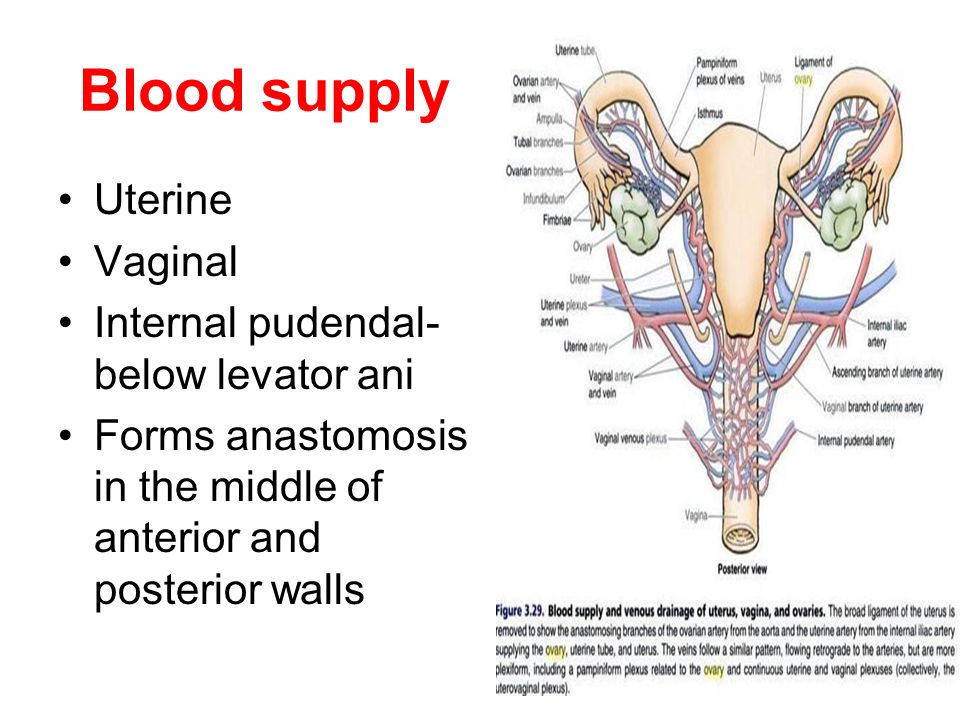

The anterior branch of the internal iliac artery supplies most of the female reproductive organs. The uterine artery supplies the majority of the uterus (Figure 3). The lower uterine segment has a dual blood supply that includes branches of the vaginal artery. The ovaries are an exception because they receive blood from the ovarian arteries, which descend from the abdominal aorta.

The superior vesicle artery supplies the upper bladder. In females, the vaginal artery supplies the lower bladder. Both arteries are also branches of the anterior branch of the internal iliac artery.

The rectum receives vascular supply via three vessels. The superior rectal artery is the terminal branch of the inferior mesenteric artery. The middle rectal is a branch of the internal iliac artery. The inferior rectal is a branch of the pudendal artery.

Venous

The venous supply of pelvic organs follows the arterial supply. The uterine vein receives blood from the uterus and drains into the internal iliac vein. The ovarian veins receive blood from the ovaries. The right ovarian vein drains its contents directly into the inferior vena cava, while the left ovarian vein drainage is into the left renal vein. The increased length of the left ovarian vein makes it more susceptible to compression, especially during pregnancy.[7] Ovarian vein compression can lead to pelvic venous compression syndrome. The resulting pelvic vasculature congestion is a cause of chronic pelvic pain and may occur in non-pregnant patients as well.

The uterine vein receives blood from the uterus and drains into the internal iliac vein. The ovarian veins receive blood from the ovaries. The right ovarian vein drains its contents directly into the inferior vena cava, while the left ovarian vein drainage is into the left renal vein. The increased length of the left ovarian vein makes it more susceptible to compression, especially during pregnancy.[7] Ovarian vein compression can lead to pelvic venous compression syndrome. The resulting pelvic vasculature congestion is a cause of chronic pelvic pain and may occur in non-pregnant patients as well.

The left-sided venous supply is also unique because the left internal iliac artery travels from its right-sided origin at the inferior vena cava towards a leftward destination in the pelvis. The longer path makes the left internal iliac more prone to compression and may explain why venous thromboembolism in pregnancy most commonly occur in the left iliac and iliofemoral veins.[8] Additionally, the leftward position of the sigmoid colon causes a gravid uterus to tip toward the right, which is thought to increase the risk of iliac vessel compression further.

Lymphatics

The lymphatic network of the pelvis is complex but is essential to understand when staging and treating gynecologic malignancies. Generally, the pelvic organs drain into the internal and external iliac lymph nodes (Figure 5).

The lymphatic drainage of the uterus is more complicated and remains somewhat ambiguous.[9] Some researchers suggest it may involve pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes.[10] A more recent study from 2017 suggests that the uterus has two primary routes of lymphatic drainage, an upper pathway that drains to the external iliac and/or obturator lymph nodes and a lower pathway that drains to the internal iliac and/or presacral lymph nodes.[11]

The ovaries are an exception to the other female pelvic organs because they do not drain to pelvic lymph nodes. Their lymphatic drainage follows their blood supply; therefore they drain directly to the paraaortic lymph nodes.

Nerves

The female reproductive organs have both autonomic and sensory innervation. Beginning with the autonomic nervous system, sympathetic fibers exit at the level of T10 to L2 to form the superior hypogastric plexus, which divides into the left and right hypogastric nerve at approximately the level of the sacral promontory. The parasympathetic nerve fibers exit at the level of S2 to 4 and meet up with the sympathetic nervous system at the right and left hypogastric nerves. The right and left hypogastric nerves then migrate inferiorly to form the inferior hypogastric plexus. After this point, the nerve fibers follow blood vessels to their target organs. The inferior hypogastric plexus also receives sensory information from the uterus.

Beginning with the autonomic nervous system, sympathetic fibers exit at the level of T10 to L2 to form the superior hypogastric plexus, which divides into the left and right hypogastric nerve at approximately the level of the sacral promontory. The parasympathetic nerve fibers exit at the level of S2 to 4 and meet up with the sympathetic nervous system at the right and left hypogastric nerves. The right and left hypogastric nerves then migrate inferiorly to form the inferior hypogastric plexus. After this point, the nerve fibers follow blood vessels to their target organs. The inferior hypogastric plexus also receives sensory information from the uterus.

The ovarian nerve innervates the ovary. Although previously thought only to contain sensory fibers, recent animal studies suggest this nerve also carries autonomic fibers that may play a role in hormone secretion and constriction of ovarian vessels.[12][13][14] Recent studies suggest that the cervix and upper vagina also have autonomic innervation; however, the role of autonomic innervation in this region remains unclear. [15][16] Sensory innervation to the cervix and upper vagina has been more widely studied and receives supply by the pelvic splanchnic nerves. The pudendal nerve supplies the sensory innervation of the lower vagina. Pudendal nerve blocks can be used to provide local pain relief to laboring women by using the ischial spines as landmarks. Although once the treatment of choice for labor pain, it is no longer commonly used due to the widespread use of epidural anesthesia.[17]

[15][16] Sensory innervation to the cervix and upper vagina has been more widely studied and receives supply by the pelvic splanchnic nerves. The pudendal nerve supplies the sensory innervation of the lower vagina. Pudendal nerve blocks can be used to provide local pain relief to laboring women by using the ischial spines as landmarks. Although once the treatment of choice for labor pain, it is no longer commonly used due to the widespread use of epidural anesthesia.[17]

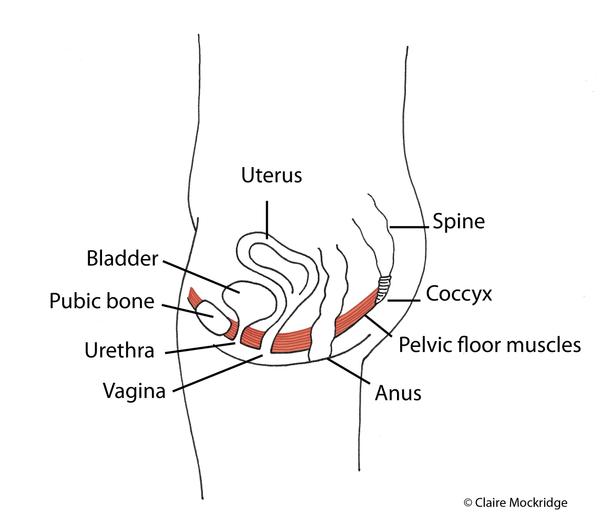

Muscles

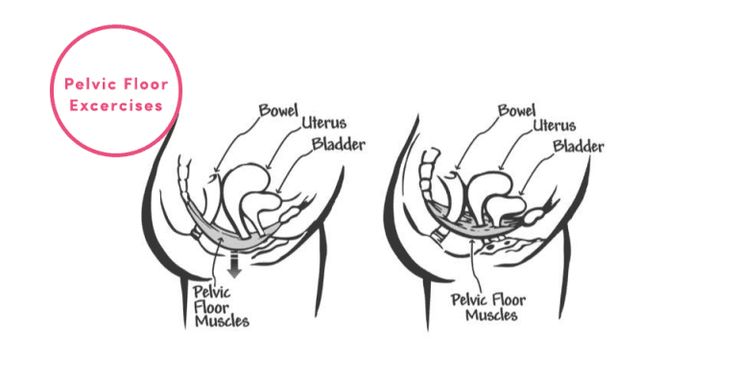

The inferior border of the pelvic cavity is the pelvic diaphragm. It is made up of a group of muscles. From posterior to anterior, these muscles include:

Piriformis

Coccygeus

Iliococcygeus

Pubococcygeus

Puborectalis

The fibers of the iliococcygeus, pubococcygeus, and puborectalis make up the levator ani muscle. Because of its proximity to the vagina, the pubococcygeus and puborectalis are the most commonly injured muscles during vaginal deliveries. [18] The obturator internus muscles make up the peripheral borders of the pelvis but are not among the muscles of the pelvic floor.

[18] The obturator internus muscles make up the peripheral borders of the pelvis but are not among the muscles of the pelvic floor.

Ligaments

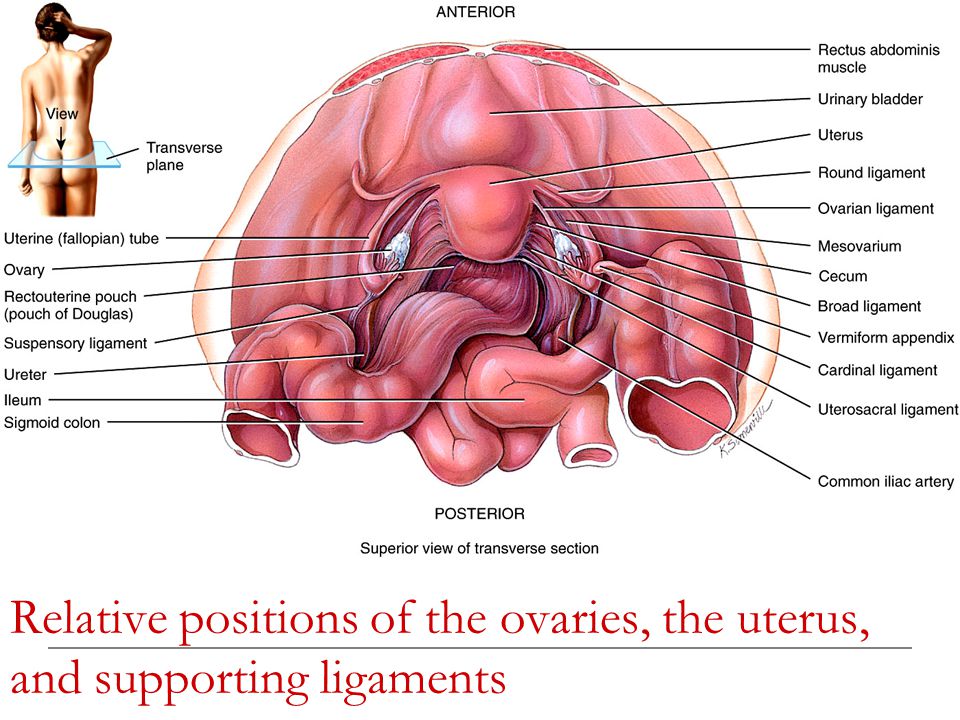

Three ligaments anchor the uterus. The uterosacral ligament supports the uterus posteriorly, and the pubocervical ligament anchors the uterus anteriorly. The transverse cervical ligament supports the uterus laterally. Unlike the anterior and posterior planes that contain the bladder and rectum respectively, the lateral plane lacks supporting structures other than the transverse cervical ligament. It is for this reason that this ligament also has the name of the "cardinal" ligament. The transverse ligament also differs from other supporting ligaments of the uterus because it is the only ligament that contains a vasculature structure, the uterine artery.

The ovary also has ligamentous support. The utero-ovarian ligament, also known as the ovarian ligament, extends from the ovary to the uterine body. The ovary is supported superiorly by the infundibulopelvic ligament, also known as the suspensory ligament of the ovary. This ligament descends from the lateral aspect of the abdominal wall and contains the ovarian neurovascular bundle.

This ligament descends from the lateral aspect of the abdominal wall and contains the ovarian neurovascular bundle.

The broad ligament overlies the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. It is the inferior most extension of the parietal peritoneum and has three divisions based on location. The lateral most aspect of the broad ligament is the "mesovarium" and overlies the ovaries. The "mesosalpinx" covers the fallopian tubes. The largest portion of the broad ligament is the "mesometrium" and overlies the uterus.

Physiologic Variants

The uterine and ovarian arteries supply the majority of the female reproductive tract. The uterine artery, like many pelvic arteries, has a variable presentation. It most commonly arises from the anterior branch of the internal iliac artery and shares a common trunk with the obliterated umbilical artery.[19] One study that analyzed imaging from 218 patients reported this presentation in 80.7 % of cases.[20] The same study reported the uterine artery branched directly off of the internal iliac in 13. 6% of cases, making this the most common variation. The second and third most common variations they found were direct branching from the superior gluteal artery and internal pudendal artery, respectively. These variations are necessary to be aware of during surgery as well as during uterine artery embolization.

6% of cases, making this the most common variation. The second and third most common variations they found were direct branching from the superior gluteal artery and internal pudendal artery, respectively. These variations are necessary to be aware of during surgery as well as during uterine artery embolization.

Ovarian artery variants are less common, but case reports exist that detail unique aberrations. One case report found an aberrant ovarian artery arising from the external iliac artery.[21] Another study reported an ovarian artery that branched directly from the common iliac artery.[22] These variations are thought to be due to abnormal descent of the ovaries into the pelvis during embryological development and may also correlate to other differences.[23]

Surgical Considerations

Several anatomical relationships are essential for surgeons to be aware of when operating in the female pelvis. For example, during a cesarean section, the bladder should always be identified to avoid iatrogenic cystotomy. This cautionary measure is especially the case in patients that have had a prior cesarean section because scar tissue can cause the bladder to adhere to the anterior uterine wall.

This cautionary measure is especially the case in patients that have had a prior cesarean section because scar tissue can cause the bladder to adhere to the anterior uterine wall.

During any uterine surgery, identification of the uterine artery is vital. If cut, massive bleeding can ensue. During abdominal hysterectomies, the uterine artery is typically “skeletonized” so that its path along the uterus is clearly identifiable to the operating team.

If hemorrhage does occur, knowledge of pelvic vasculature becomes crucial. If the bleeding vessel cannot be clearly identified, the internal iliac should be clamped below the origin of the superior gluteal artery. This method is preferred so that necrosis of the gluteal muscle does not occur.

When operating deeper in the female pelvis, identification of the ureter is also crucial. There are three major locations where this structure may exist. Beginning superiorly, the ureters descend into the pelvis posterior to the infundibulopelvic ligaments. The ureters maintain this relationship until approximately the level of the iliac vessels, where they begin to travel more medially.

The ureters maintain this relationship until approximately the level of the iliac vessels, where they begin to travel more medially.

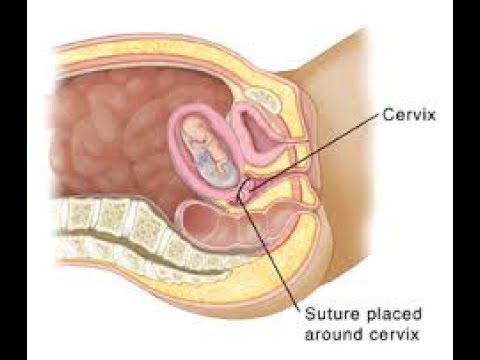

As the ureters continue to travel inferiorly, the next important landmark is the transverse cervical ligament. The ureters dive under this structure. Awareness of this relationship is of considerable importance when performing a hysterectomy. A popular pneumonic used by medical students is, "water under the bridge."

After passing under the transverse cervical ligament, the ureters continue to travel medially toward the bladder. Their insertion into the inferior aspect of the bladder is the third major location they should undergo positive identification intraoperatively. The insertion points are also visible from inside the bladder itself, during cystoscopy; this is sometimes performed after pelvic surgery if an injury to the bladder is suspected.

Injury to the bladder can also occur during pelvic surgery from the vaginal approach. When operating in this plane, injury to the rectum is also a possibility because at this level the rectum is directly posterior to the vagina (Figure 6. ) Avoiding bladder and rectal injury becomes increasingly difficult if the patient has pelvic organ prolapse, such as cystocele or rectocele.

) Avoiding bladder and rectal injury becomes increasingly difficult if the patient has pelvic organ prolapse, such as cystocele or rectocele.

When performing surgery on the fallopian tubes, such as during a tubal ligation or tubal anastomosis, the location of the round ligament should be determined. Due to the similarity in structure and location, the round ligament can be mistaken for a fallopian tube. Unlike the round ligaments, however, the fallopian tubes have fimbriae, a characteristic can be used to differentiate between these two structures intraoperatively.

Clinical Significance

Clinical correlates related to female pelvic anatomy can be summarized as follows:

The standard position of the uterus is anteverted and anteflexed. Abnormal positioning of the uterus is associated with pathology. Retroversion, for example, is a cause of dyspareunia. Additionally, retroversion of a gravid uterus is associated with higher rates of spontaneous abortion.

The posterior cul-de-sac, located between the uterus and the rectum, is a potential space prone to fluid collection.

Physiologic fluid accumulates during menses and ovulation. If fluid collection is pathologic, this space can undergo drainage via culdocentesis.

Physiologic fluid accumulates during menses and ovulation. If fluid collection is pathologic, this space can undergo drainage via culdocentesis.The posterior cul-de-sac communicates with the abdomen via the left and right epiploic gutters, which allows the spread of pelvic pathogens into the abdominal cavity. Due to the leftward position of the rectum, infections usual take the path of the right epiploic gutter. The right epiploic gutter leads to potential spaces surrounding the liver. These include the hepatorenal space, also known as Morrison’s pouch, and the subphrenic space. Infection of the subphrenic space secondary to a gonococcal pelvic infection is termed Fitz-Curtis-Hugh syndrome or gonococcal perihepatitis.

The increased length of the left ovarian vein makes it more susceptible to compression, especially during pregnancy. Compression of this vessel sometimes leads to pelvic venous compression syndrome and is a cause of chronic pelvic pain in both pregnant and non-pregnant patients.

Venous thromboembolism in pregnancy is most commonly left-sided and occur in the iliofemoral vessels, which is thought to be because of pelvic vessel engorgement in combination with the increased path the left iliac vein takes across the pelvis. These factors make this vessel more susceptible to compression by a gravid uterus.

Understanding the lymphatic drainage of the female reproductive tract is important when tracking the spread of gynecologic malignancies. Generally, the female reproductive organs drain to the internal and external iliac lymph nodes. A notable exception is the ovaries, which drain to the paraaortic lymph nodes.

The pudendal nerve receives sensory innervation to the lower vagina. Historically, pudendal nerve blocks were used to alleviate labor pains. However, pudendal nerve blocks are no longer commonly practiced due to the wide-spread use of epidural anesthesia.

The muscles of the pelvic floor are susceptible to injury during vaginal deliveries.

The most commonly injured muscles are the pubococcygeus and puborectalis muscles due to their proximity to the vagina.

The most commonly injured muscles are the pubococcygeus and puborectalis muscles due to their proximity to the vagina.The pelvic vasculature contains many physiologic variants that are important for surgeons to know. Interventional radiologists should also be knowledgeable of variants, particularly during uterine artery embolization to treat fibroids. The uterine artery most commonly arises from the anterior branch of the internal iliac and shares a trunk with the obliterated umbilical artery. The most common variation is direct branching from the internal iliac.

Review Questions

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Comment on this article.

Figure

Compilation of 6 images detailing anatomy of female pelvic cavity. Contributed by Gray's Anatomy Plates (Public Domain)

References

- 1.

Roach MK, Andreotti RF. The Normal Female Pelvis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Mar;60(1):3-10.

[PubMed: 28005593]

[PubMed: 28005593]- 2.

Weekes AR, Atlay RD, Brown VA, Jordan EC, Murray SM. The retroverted gravid uterus and its effect on the outcome of pregnancy. Br Med J. 1976 Mar 13;1(6010):622-4. [PMC free article: PMC1639005] [PubMed: 1252851]

- 3.

Sanders RC, Parsons AK. Anteverted retroflexed uterus: a common consequence of cesarean delivery. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014 Jul;203(1):W117-24. [PubMed: 24951223]

- 4.

Turco G, Chiesa GM, de Manzoni G. [Echographic anatomy of the greater peritoneal cavity and its recesses]. Radiol Med. 1988 Jan-Feb;75(1-2):46-55. [PubMed: 3279472]

- 5.

Yao HH. The pathway to femaleness: current knowledge on embryonic development of the ovary. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005 Jan 31;230(1-2):87-93. [PMC free article: PMC4073593] [PubMed: 15664455]

- 6.

Robboy SJ, Kurita T, Baskin L, Cunha GR. New insights into human female reproductive tract development. Differentiation.

2017 Sep - Oct;97:9-22. [PMC free article: PMC5712241] [PubMed: 28918284]

2017 Sep - Oct;97:9-22. [PMC free article: PMC5712241] [PubMed: 28918284]- 7.

Jeanneret C, Beier K, von Weymarn A, Traber J. Pelvic congestion syndrome and left renal compression syndrome - clinical features and therapeutic approaches. Vasa. 2016;45(4):275-82. [PubMed: 27428495]

- 8.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 196: Thromboembolism in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jul;132(1):e1-e17. [PubMed: 29939938]

- 9.

Coleman RL, Frumovitz M, Levenback CF. Current perspectives on lymphatic mapping in carcinomas of the uterine corpus and cervix. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006 May;4(5):471-8. [PubMed: 16687095]

- 10.

Burke TW, Levenback C, Tornos C, Morris M, Wharton JT, Gershenson DM. Intraabdominal lymphatic mapping to direct selective pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy in women with high-risk endometrial cancer: results of a pilot study.

Gynecol Oncol. 1996 Aug;62(2):169-73. [PubMed: 8751545]

Gynecol Oncol. 1996 Aug;62(2):169-73. [PubMed: 8751545]- 11.

Geppert B, Lönnerfors C, Bollino M, Arechvo A, Persson J. A study on uterine lymphatic anatomy for standardization of pelvic sentinel lymph node detection in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 May;145(2):256-261. [PubMed: 28196672]

- 12.

Uchida S, Kagitani F. Autonomic nervous regulation of ovarian function by noxious somatic afferent stimulation. J Physiol Sci. 2015 Jan;65(1):1-9. [PMC free article: PMC4276811] [PubMed: 24966153]

- 13.

Pastelín CF, Rosas NH, Morales-Ledesma L, Linares R, Domínguez R, Morán C. Anatomical organization and neural pathways of the ovarian plexus nerve in rats. J Ovarian Res. 2017 Mar 14;10(1):18. [PMC free article: PMC5351206] [PubMed: 28292315]

- 14.

Cruz G, Fernandois D, Paredes AH. Ovarian function and reproductive senescence in the rat: role of ovarian sympathetic innervation. Reproduction. 2017 Feb;153(2):R59-R68.

[PubMed: 27799628]

[PubMed: 27799628]- 15.

Mónica Brauer M, Smith PG. Estrogen and female reproductive tract innervation: cellular and molecular mechanisms of autonomic neuroplasticity. Auton Neurosci. 2015 Jan;187:1-17. [PMC free article: PMC4412365] [PubMed: 25530517]

- 16.

Mowa CN. Uterine Cervical Neurotransmission and Cervical Remodeling. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2017;18(2):120-124. [PubMed: 27001061]

- 17.

Schrock SD, Harraway-Smith C. Labor analgesia. Am Fam Physician. 2012 Mar 01;85(5):447-54. [PubMed: 22534222]

- 18.

Memon HU, Handa VL. Vaginal childbirth and pelvic floor disorders. Womens Health (Lond). 2013 May;9(3):265-77; quiz 276-7. [PMC free article: PMC3877300] [PubMed: 23638782]

- 19.

Peters A, Stuparich MA, Mansuria SM, Lee TT. Anatomic vascular considerations in uterine artery ligation at its origin during laparoscopic hysterectomies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;215(3):393.e1-3. [PubMed: 27287682]

- 20.

Chantalat E, Merigot O, Chaynes P, Lauwers F, Delchier MC, Rimailho J. Radiological anatomical study of the origin of the uterine artery. Surg Radiol Anat. 2014 Dec;36(10):1093-9. [PubMed: 24052200]

- 21.

Kwon JH, Kim MD, Lee KH, Lee M, Lee MS, Won JY, Park SI, Lee DY. Aberrant ovarian collateral originating from external iliac artery during uterine artery embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013 Feb;36(1):269-71. [PubMed: 22565531]

- 22.

Kim WK, Yang SB, Goo DE, Kim YJ, Chang YW, Lee JM. Aberrant ovarian artery arising from the common iliac artery: case report. Korean J Radiol. 2013 Jan-Feb;14(1):91-3. [PMC free article: PMC3542308] [PubMed: 23323036]

- 23.

Rahman HA, Dong K, Yamadori T. Unique course of the ovarian artery associated with other variations. J Anat. 1993 Apr;182 ( Pt 2):287-90. [PMC free article: PMC1259840] [PubMed: 8376204]

Your Body throughout Pregnancy

Your Body Before Pregnancy

Next Image

Your Body Before Pregnancy

Before pregnancy, most of the space in your abdomen is taken up by the large and small intestines. There is no real separation between the areas of your pelvis and abdomen.

There is no real separation between the areas of your pelvis and abdomen.

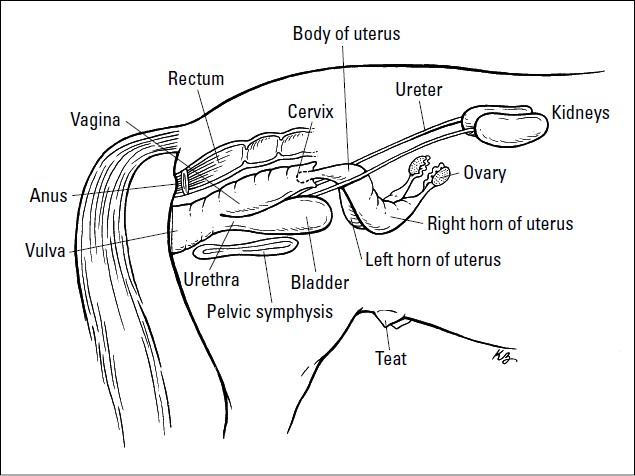

In the picture here, you can see that the vagina is behind the bladder (sac that collects urine) and urethra (tube for moving urine out of bladder and body). In its normal position, your uterus is above and behind the bladder, with the cervix protruding into the vagina. The pelvic colon, rectum and anal canal are behind the vagina and uterus.

Previous | Next

Your Body at 6-7 Weeks of Pregnancy

Next Image

Your Body at 6-7 Weeks of Pregnancy

When you are between 6 and 7 weeks pregnant, you may be experiencing the early signs of pregnancy: your period has stopped and you may have nausea, breast tenderness and swelling, frequent urination and fatigue.

At this point, your uterus has begun to grow and become more egg-shaped. The pressure of the growing uterus on the bladder causes frequent urge to urinate.

In this image, you can see the beginnings of the placenta in the uterus. The embryo is about 1/4 inch to 1/2 inch long and weighs 1/1,000th of an ounce.

The embryo’s head is large in proportion to the rest of the body. The internal organs are forming and the heart has been beating since the end of the 4th week.

The embryo is floating in the amniotic sac. Buds for the arms and legs emerge in the 5th week and, by the 7th week, buds for fingers and toes also appear. The umbilical cord is lengthening and will continue to grow, allowing the fetus freedom to move. The 7th week represents a milestone in development: the embryo is now considered a fetus.

Previous | Next

Your Body at 12 Weeks of Pregnancy

Next Image

Your Body at 12 Weeks of Pregnancy

At the 12th week of pregnancy, the placenta is much larger. It now produces the hormones needed to sustain the pregnancy. Your uterus is the size of a grapefruit and completely fills the pelvis. It rises up into the area of the abdomen, as shown in the image. The fundus, the upper end of the uterus, is just above the top of the symphysis where the pubic bones join together. This upward growth of the uterus takes pressure off the bladder and decreases the need for frequent urination. The mucus plug, a barrier to protect the growing fetus, fills your cervical canal.

It now produces the hormones needed to sustain the pregnancy. Your uterus is the size of a grapefruit and completely fills the pelvis. It rises up into the area of the abdomen, as shown in the image. The fundus, the upper end of the uterus, is just above the top of the symphysis where the pubic bones join together. This upward growth of the uterus takes pressure off the bladder and decreases the need for frequent urination. The mucus plug, a barrier to protect the growing fetus, fills your cervical canal.

The fetus is now about 3 inches long and weighs about 1 ounce. By this week, the fetus has fingernails and toenails and can open and close the fingers. The fetus will start to move, but you will not feel it yet.

Previous | Next

Your Body at 20 Weeks of Pregnancy

Next Image

Your Body at 20 Weeks of Pregnancy

By the 20th week of pregnancy, your uterus can be felt at the level of your belly button (umbilicus). The pelvic colon and small intestines are crowded upward and backward. The ascending and descending colon maintain their usual positions.

The pelvic colon and small intestines are crowded upward and backward. The ascending and descending colon maintain their usual positions.

At this point, your uterus is especially enlarged where the placenta attaches to it (usually on the front or back wall). This gives the uterus an uneven bulge. The wall of the uterus, which lengthens and thickens early in pregnancy, stretches as the fetus grows, and becomes thinner now – just 3 to 5 millimeters thick. Your bladder moves up but not as much as your uterus, which straightens as it moves up.

As your uterus moves up, it rests against the lower portion of the front of your abdominal wall, causing it to bulge forward noticeably by your 20th week. The size of the bulge depends on how strong your abdominal muscles are. If they are firm, the uterus may be pressed against the spinal column, and there will be no noticeable bulge; if they are weak, the pressure of the uterus against the inside wall makes a sizeable bulge.

At this point, you should be able to feel light movements of the fetus. This is called “quickening.” You may recognize this earlier if you have been pregnant before. The fetus sleeps and wakes at regular intervals, is more active, is about 9 inches long and weighs between a half-pound and a pound.

This is called “quickening.” You may recognize this earlier if you have been pregnant before. The fetus sleeps and wakes at regular intervals, is more active, is about 9 inches long and weighs between a half-pound and a pound.

Previous | Next

Next Image

At this point in pregnancy, the top of your uterus is about one-third of the distance between the bellybutton and the xiphoid cartilage at the lower end of your breastbone. Constipation is common because your uterus is pressing on your lower colon and hormones slow down your body’s excretion process. Between the growth of your uterus and general weight gain, you may be feeling fatigued. Some women also experience heartburn as your uterus presses against your stomach.

Your breasts are also changing to get ready for breastfeeding. First colostrum and then milk are produced by the grape-like clusters of tiny sacs (alveoli) deep within the breast tissue. Clusters of alveoli form lobules, which come together to form 15 to 20 lobes. Each lobe connects to a lactiferous duct for conveying milk. As the ducts extend toward the nipple and areola (darker area around the nipple), they widen into the lactiferous sinuses. These sinuses (or milk pools) release the milk through 15 to 20 tiny nipple openings in each breast when the baby nurses.

At week 28, the fetus is about 16 inches long and weighs two to three pounds. The skin is wrinkled but will become less so as more fat builds up under the skin in the next few weeks. Fine, downy hair called lanugo, and a waxy white protective substance covering the skin called vernix, are on the fetus’ body. Its eyes are open, and eyebrows and eyelashes were formed in the fourth month. The fetus sucks its thumb and its taste buds have developed. It kicks, stretches and moves frequently in your uterus—you’ll feel it moving around and others might even be able to see these movements!

It kicks, stretches and moves frequently in your uterus—you’ll feel it moving around and others might even be able to see these movements!

Fetal organs and systems are quite well developed by the 28th week of pregnancy, but the final two months of gestation are important for further maturation of all body systems and organs.

Previous | Next

Your Body at 36 Weeks of Pregnancy

Next Image

Your Body at 36 Weeks of Pregnancy

By the end of the 36th week of pregnancy, your enlarged uterus almost fills the space within your abdomen. The fetus is inside the membrane sac within the uterus and high within the abdomen. The muscles of your abdomen support much of its weight.

During this week, the top of the uterus is at the tip of the xiphoid cartilage at the lower end of the breastbone, which is pushed forward.

The change in the position of the heart and the upward pressure of the diaphragm may make it hard to breathe at this point. The crowding of your stomach and intestines may contribute to discomfort after eating.

Your cervix is long, thick and filled with the mucous plug. By the 36th week, your vagina and urethra are elongated and all the tissues in the perineum (area between vaginal and anal openings) are enlarged. The swollen perineum projects outward in the last weeks of pregnancy and readily expands during labor.

The brain of the fetus is growing rapidly, but bones in the skull are soft so that he or she will fit through your vagina at birth. The lungs are still forming. You will likely feel the fetus kicking and may be aware of rhythmic movements, which could be hiccups or thumb sucking. Another possible sensation, sudden movement, may be a startle response.

Previous | Next

Your Body at 40 Weeks of Pregnancy (Internal)

Next Image

Your Body at 40 Weeks of Pregnancy (Internal)

At full term, or 40 weeks of pregnancy, the fetus’ head has generally lowered into your pelvis, where it takes up most of the space. This is called “lightening.” In first pregnancies, this may happen a few weeks before labor. In repeat pregnancies, this can happen at the time of labor. The canal of the broad, enlarged cervix is still filled with the plug of mucous. If this is your first pregnancy, the small opening at the bottom of your cervix is usually not dilated, whereas if you have given birth before, it will often be open as wide as two fingers some time before labor begins.

At this point, you may be experiencing frequent urination, increased constipation, edema (water retention) and aching legs or vulva. Varicose veins in the vulva, rectum and legs are also possible. This is because of the position of the uterus, the pressure of the baby's head and a loss of muscle tone as the hormone relaxin loosens your tissues in preparation for birth. Other changes at this time include increased development of blood vessels and increased amount of blood.

Previous | Next

Your Body at 40 Weeks of Pregnancy (External)

Next Image

Your Body at 40 Weeks of Pregnancy (External)

You can see that the round ligament is long and enlarged. It is also farther forward because of the twisting of the uterus. The enlarged uterosacral ligament is shown stretched taut by the enlarged uterus. Backaches in late pregnancy may be due to the stress of the weight of your uterus on the ligaments that connect it to your spine.

It is also farther forward because of the twisting of the uterus. The enlarged uterosacral ligament is shown stretched taut by the enlarged uterus. Backaches in late pregnancy may be due to the stress of the weight of your uterus on the ligaments that connect it to your spine.

Because your uterus dropped a bit, you may be able to breathe and eat more comfortably near the end of your pregnancy.

At this time, the lungs of the fetus are likely fully mature and ready to begin breathing. The fetus gains about a half pound every week at the end of pregnancy, for a birth weight of roughly 7 pounds, and is growing longer for a birth length of about 18 to 21 inches.

Labor starting on its own around week 40 is a sign that your body is ready to give birth and your baby is ready to be born.

Previous | Next

How is the female body? - Family clinic Arnika, Krasnoyarsk

Services

Virtual tour.

Clinic "ARNIKA"

Clinic "ARNIKA"

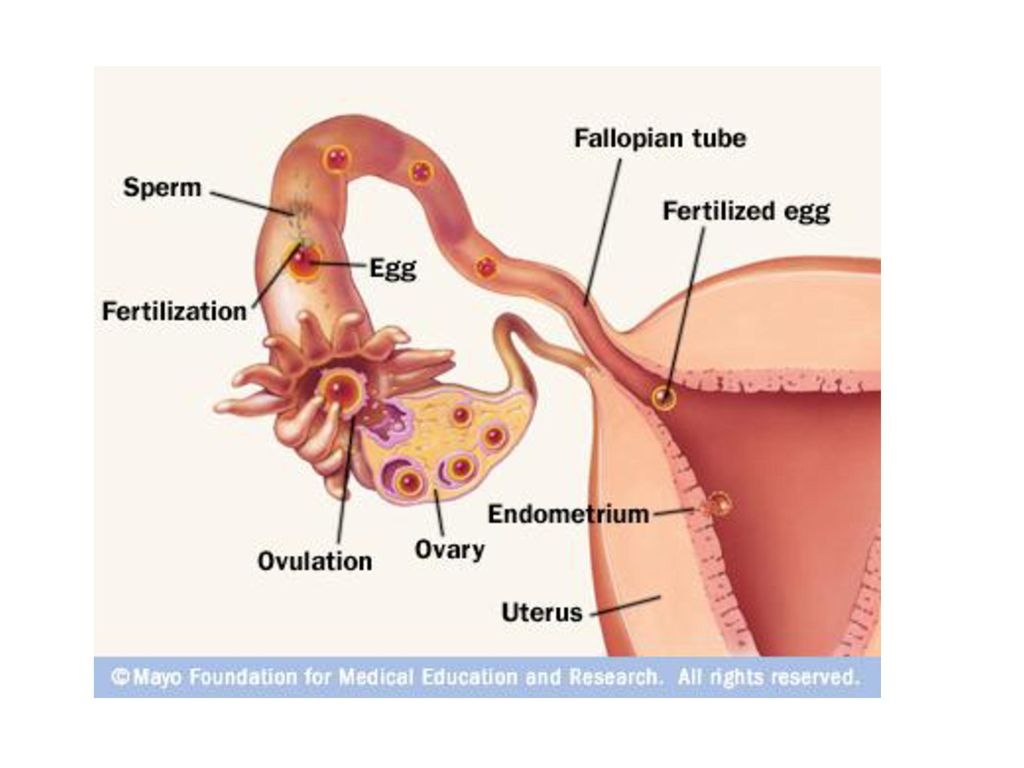

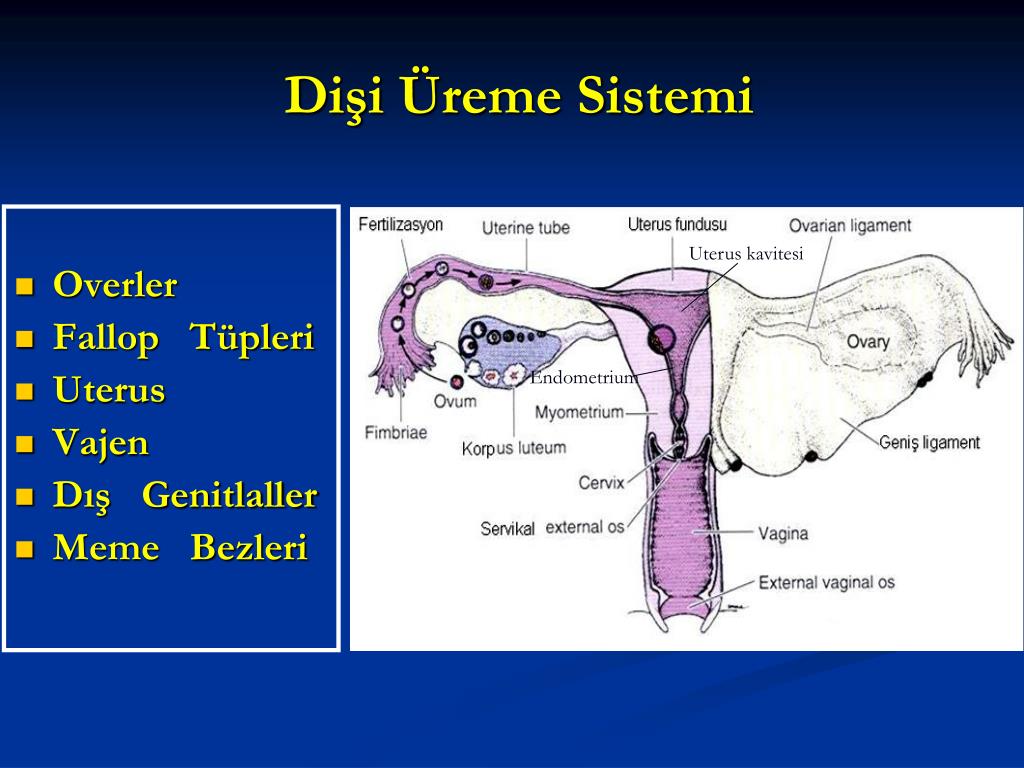

Did you know that the uterus can increase 20 times during pregnancy? This is a unique organ located in the pelvis and connected to the fallopian tubes. If the fallopian tubes are blocked, infertility or an ectopic pregnancy may develop. The cervix connects the uterus and vagina, and the ovaries produce eggs.

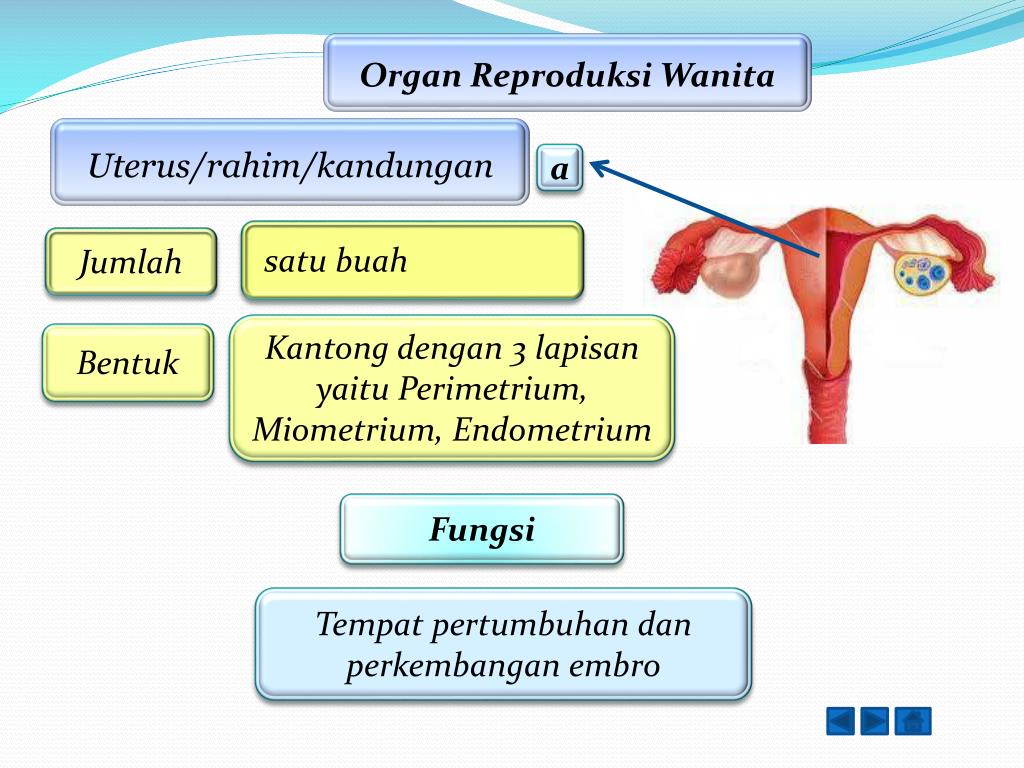

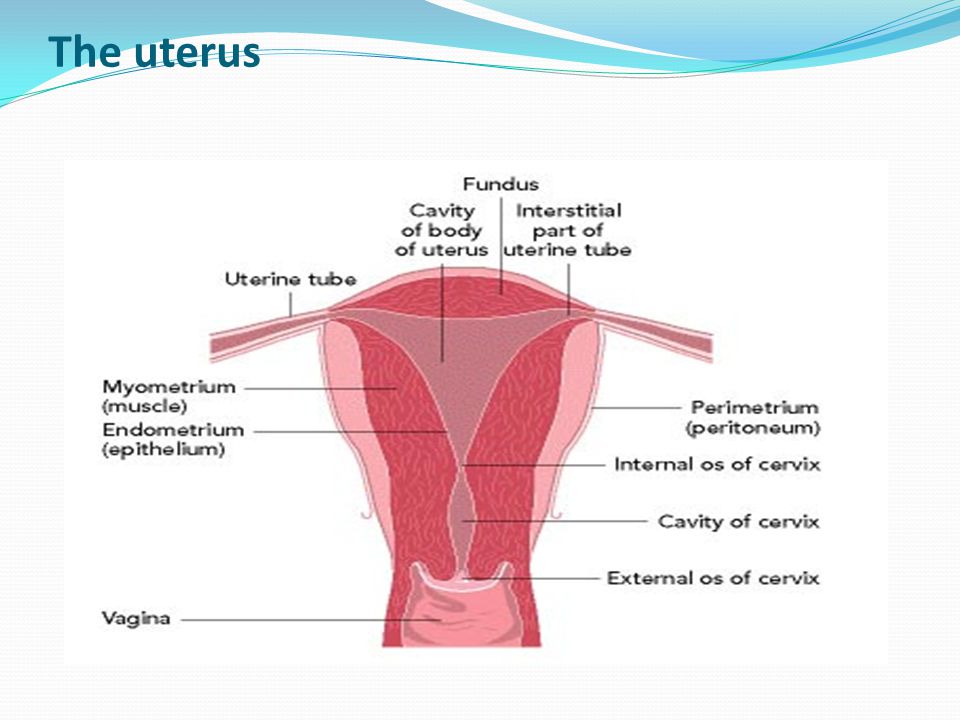

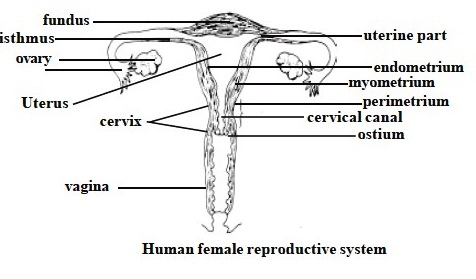

Uterus

The most important function of the uterus is to carry the fetus (unborn child) during pregnancy. The uterus is a truly unique organ: during pregnancy, it increases about 20 times. You can calculate it yourself: in a non-pregnant woman, the uterus weighs about 50-60 g, and by the end of pregnancy, its weight reaches 1 kg. After childbirth, the uterus contracts, decreasing to its normal size.

The uterus is located in the small pelvis, behind the pubis. In front of the uterus is the bladder, and behind the uterus is the intestines. During the examination on the gynecological chair, the gynecologist cannot see the uterus, but he can feel it and determine the size.

The uterus looks like a pouch turned upside down. The walls of the uterus are very thick and are made up of muscles. Thanks to these muscles, the birth of a child is possible. During childbirth, the muscles of the uterus begin to contract intensely, pushing the baby out.

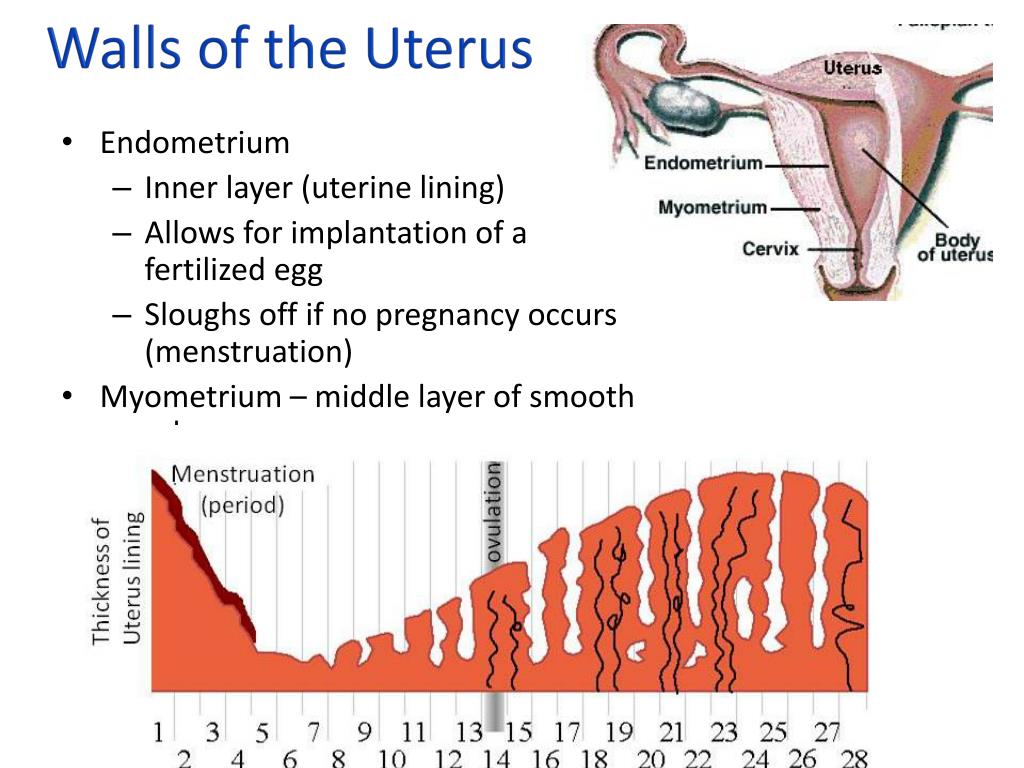

There is a small cavity inside the uterus. In the uterine cavity is the endometrium - the inner layer of the uterus. Every month, the endometrium is shed from the uterine cavity, coming out through the vagina. This is menstruation, or menstruation.

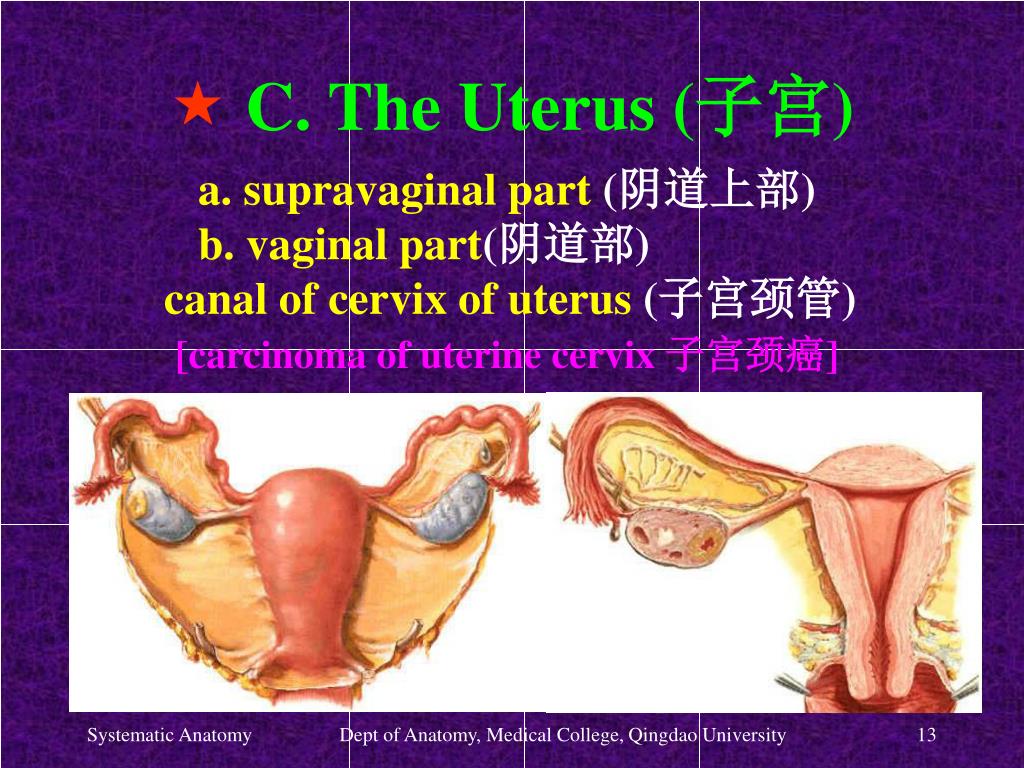

Cervix

The cervix is the continuation of the uterus, its lower part, which also consists of muscles and separates the uterus from the vagina.

There is a channel in the center of the cervix called the cervical canal. Through this channel, the endometrium is excreted during menstruation, and through it the spermatozoa enter the uterus, and then meet with the egg. The cervical canal is very narrow, but during childbirth it expands to allow the baby to leave the uterus.

The gynecologist can see the lower part of the cervix, as well as the external opening of the cervical canal during examination on the gynecological chair. In order to have a good look at the cervix, the gynecologist uses a speculum.

The cervix is subject to various diseases: erosion and pseudo-erosion of the cervix (ectopia), cervical dysplasia, cervical cancer, inflammation of the cervix (cervicitis), etc. In order to identify these diseases in time, every woman should regularly visit a gynecologist and take a smear for cytology at least once every 2 years.

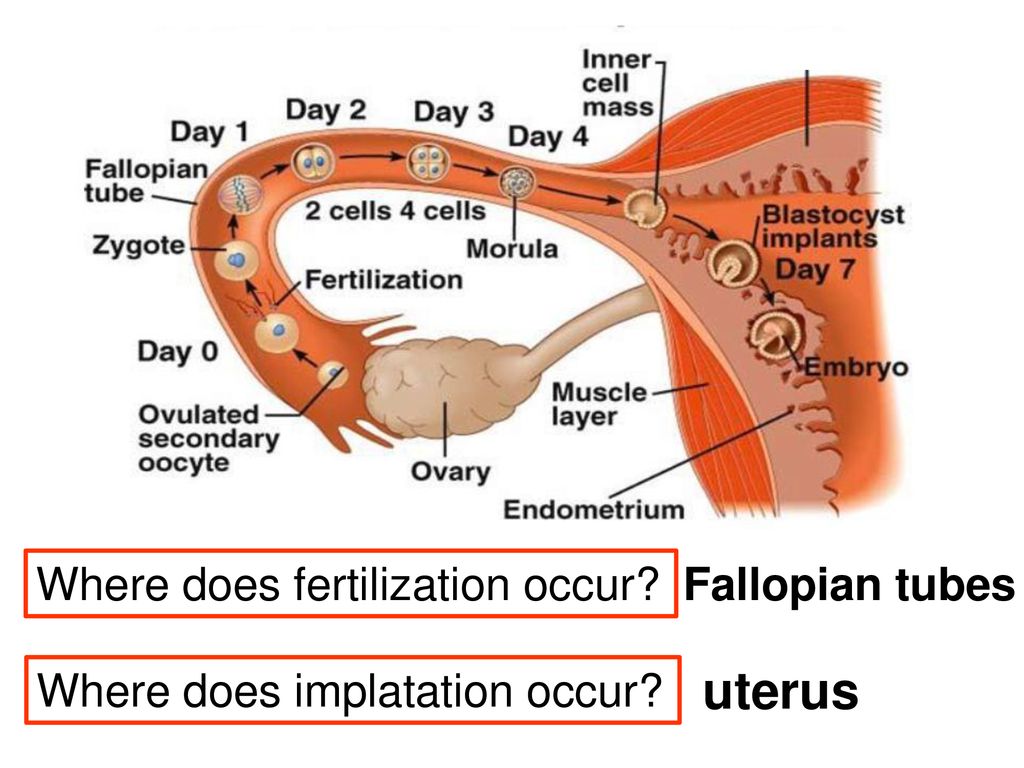

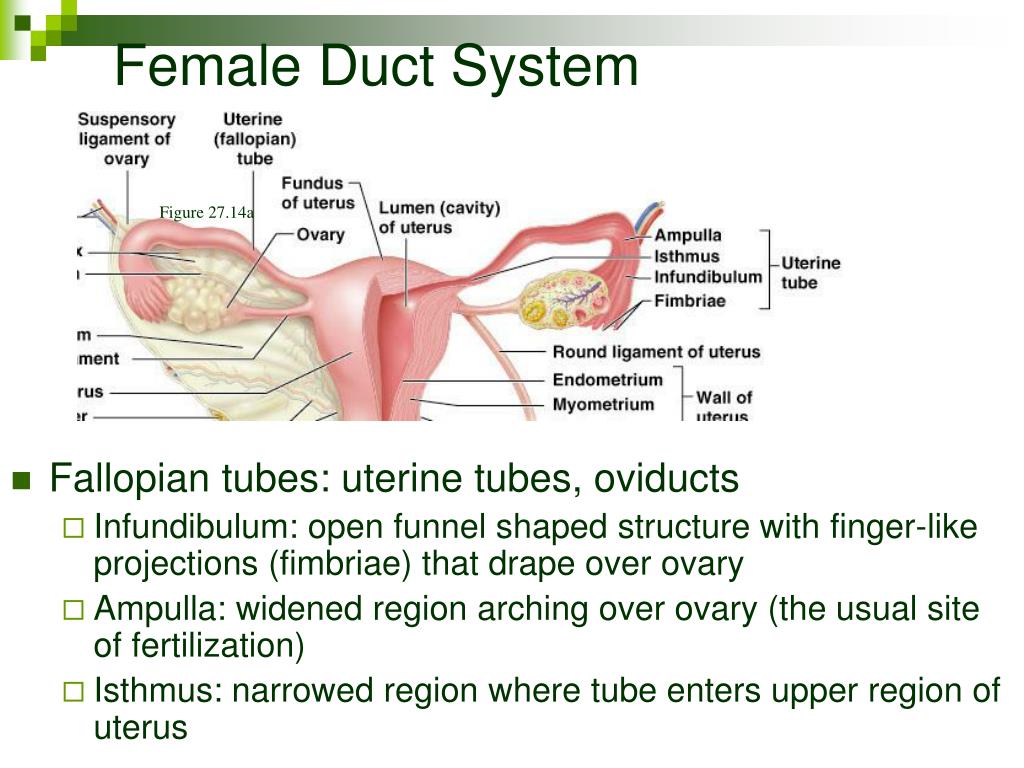

Fallopian tubes

Every woman has 2 fallopian tubes: to the left and to the right of the uterus. Fallopian tubes are also called fallopian tubes, after the scientist Fallopius, who first described them. The fallopian tubes connect to the uterine cavity on the sides, at the top of the uterus.

It is in the fallopian tubes that the meeting of the spermatozoon and the ovum most often takes place. Having united in one cell, they move towards the uterus in order to attach in its cavity and continue their development.

Having united in one cell, they move towards the uterus in order to attach in its cavity and continue their development.

Inflammation of the fallopian tubes can lead to their obstruction. If the fallopian tubes are blocked, then the sperm and egg cannot meet, and pregnancy in this case is impossible.

Fallopian tubes are normally not visible on ultrasound. During examination and palpation, the gynecologist also cannot palpate the fallopian tubes. In order to determine the condition of the fallopian tubes, hysterosalpingography is used.

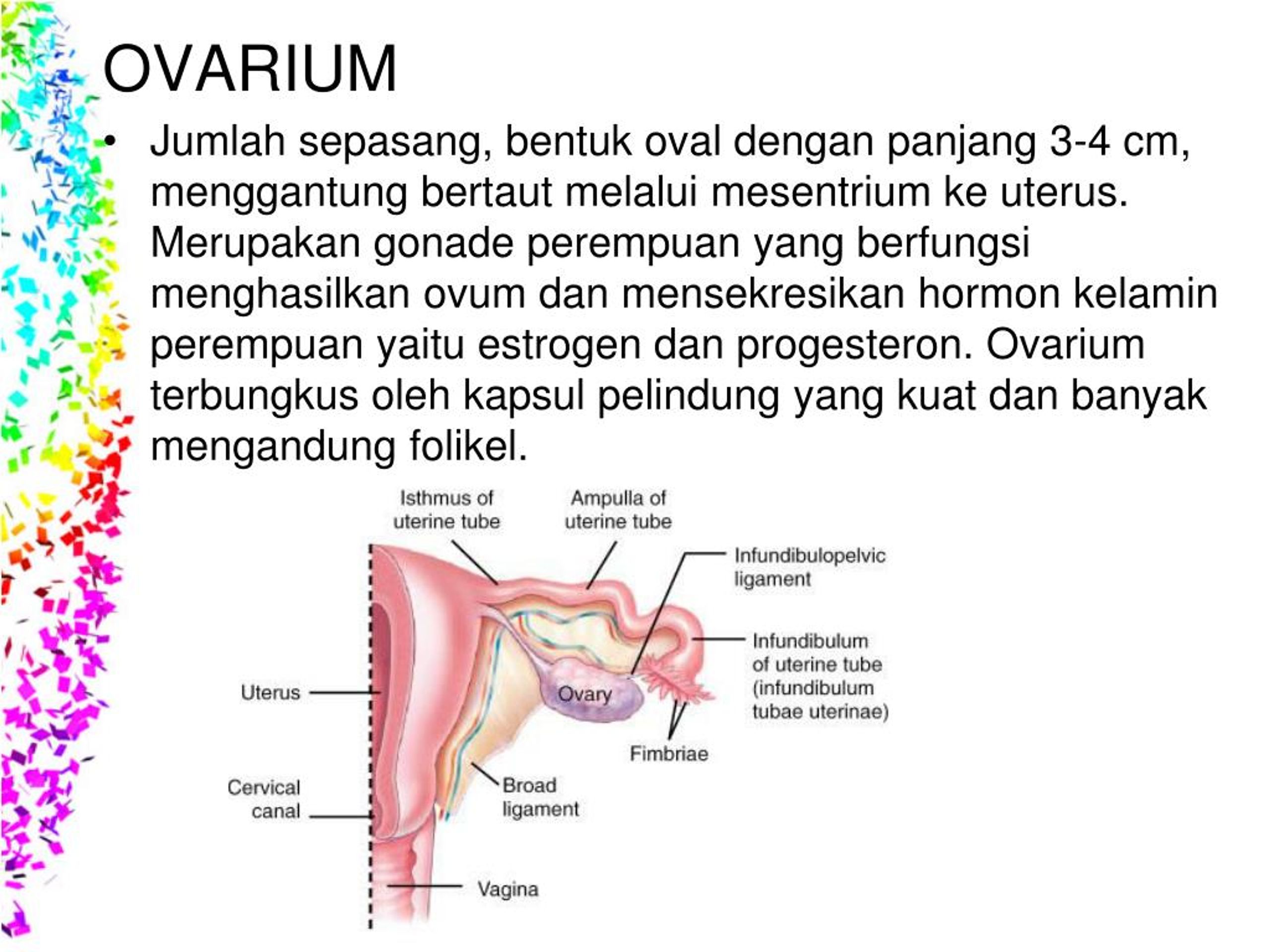

Ovaries

Every woman has 2 ovaries: right and left. From the moment of puberty (from about 12-13 years old), every month an egg matures in one of the ovaries. The ovum is the "half" of the unborn child, which, when combined with the second "half" - the sperm, forms an embryo.

The egg matures inside a vesicle called a follicle. When the follicle reaches a certain size, it bursts and an egg is released from it. This moment is called ovulation. It is on the day of ovulation that a woman can become pregnant.

This moment is called ovulation. It is on the day of ovulation that a woman can become pregnant.

Another important feature of the ovaries is the ability to produce sex hormones. Sex hormones affect the menstrual cycle: without them, the maturation of the follicle in the ovary, ovulation, and even menstruation are impossible.

After 45-50 years, when the ovaries stop working, they no longer ovulate and no longer produce sex hormones. Menstruation also stops due to lack of hormones. This condition is called menopause, or menopause.

During a gynecological examination, the gynecologist cannot see the ovaries, but can feel them as well as the uterus. If you are still a virgin, then the gynecologist can feel the ovaries through the anus, and if you are already sexually active, then through the vagina.

How to catch a queen ant

Please enable JavaScript in your browser!

Reception of orders through the site around the clock. Delivery throughout Russia.

Delivery throughout Russia.

- Articles

- How to catch a queen ant

There is a wonderful time for which both ants and myrmkeepers are preparing equally zealously. This is the period when winged individuals leave their native anthill to mate and give rise to new colonies. It is then that you need to look for queens that have flown away, which have dropped their wings and are looking for shelter, because every ant lover knows that one of the best such shelters is his personal formicarium. How to prepare for this crucial moment, what to take with you and when to expect it? Now we'll find out.

- Preparation . Ants prepare for the flight all year round, accumulating food supplies and fattening larvae (especially queen bees). Still would! From how well-fed the uterus will be, its future fate depends on whether it will be able to grow its own helpers or not.

The worldkeeper must also eat well during this period - after all, he will have to travel, perhaps, several kilometers before he finally meets the desired object of his hunt. However, to meet is still half the battle, you need to catch and put it where the uterus can survive the journey to the house. What should be in your worldkeeper backpack? Of course, test tubes.

The worldkeeper must also eat well during this period - after all, he will have to travel, perhaps, several kilometers before he finally meets the desired object of his hunt. However, to meet is still half the battle, you need to catch and put it where the uterus can survive the journey to the house. What should be in your worldkeeper backpack? Of course, test tubes.

It is advisable to take not glass, but plastic in the field - such test tubes will not break under unforeseen circumstances. In the absence of test tubes, you can limit yourself to different-sized syringes. Now the most important thing is that your womb transfer structure needs to conserve water - rolled up cotton wool will do a good job of this. At the same time, it is not at all necessary to make a classic incubator with water and cotton, moreover, due to shaking and temperature differences, the liquid can leak and flood your catch! Moisten the cotton wool and push it into the end of the tube will be enough.

The time of flight is an unpredictable phenomenon, therefore, a backpack full of test tubes is sometimes superfluous. No one knows whether you will meet queen ants on a walk or not. If they are unexpectedly found, you can use any jar / box, putting leaves of herbaceous plants, wet moss or a napkin (and even a piece of newspaper) soaked in the nearest puddle to moisten.

Anyway, after the capture, your prey will have to be relocated to more worthy conditions.

- Year . Finally, the long-awaited moment has arrived! From the anthill, which you regularly visited to check if the ants were ready to fly, winged individuals appeared. Among them are large queens! They caught a dozen, no less, now they need to be transplanted into incubators and wait for the ants. Or not? Of course not. Established queens will shed their wings and begin nest-laying in the same way as their normal counterparts, but their eggs will either not develop or will grow into males.

But why? One condition was simply not met: for a full-fledged flight, the queen must mate with the male, but this did not happen - she did not even have time to fly away from the nest, let alone meet her “soul mate”.

But why? One condition was simply not met: for a full-fledged flight, the queen must mate with the male, but this did not happen - she did not even have time to fly away from the nest, let alone meet her “soul mate”.

In order to get a supply of sperm for many years of life, some queens even mate with several males and only then break off their wings and look for a place to live. Therefore, only wingless queens should be caught - this will serve as a guarantee that they are fertilized and will give life to worker ants.

- Timing . If you walk for a long time, carefully contemplating the ground under your feet, someday luck will smile at you, and the treasured uterus will be found. It is better to look for them away from human habitation: in the forest, in the meadow, in the field. You should not delve into the wilds - female ants are very often found on roads and open areas that are not overgrown with grass.

In any case, if you are a real worldkeeper, always carry a couple of test tubes in your pocket. However, this does not mean at all that you can catch someone in the snow in January, because each type of ant flies in a strictly defined period. All Russian ants conditionally fly from late April to October, but in order to search for specific queens, it is important to know exactly when you can meet them.

In any case, if you are a real worldkeeper, always carry a couple of test tubes in your pocket. However, this does not mean at all that you can catch someone in the snow in January, because each type of ant flies in a strictly defined period. All Russian ants conditionally fly from late April to October, but in order to search for specific queens, it is important to know exactly when you can meet them.

The flight relay starts at the end of April in the steppe regions of our country. At this time, everyone's favorite reapers fly - ants of the genus Messor.

In May they are joined by Tapinoma erraticum, various wood borers (Camponotus), higher formics (Formica rufa/polyctena). June-July is the time for the flight of Serviformica, Tetramorium, numerous Lasius, slave owners - Raptiformica sanguinea and Polyergus rufescens. Some of these species can be found in August, and even in early September. Autumn is given to representatives of the genera Myrmica (whose overwintered queens are also found in spring) and Solenopsis.