What is a preterm baby

Premature birth - Symptoms and causes

Overview

A premature birth is a birth that takes place more than three weeks before the baby's estimated due date. In other words, a premature birth is one that occurs before the start of the 37th week of pregnancy.

Premature babies, especially those born very early, often have complicated medical problems. Typically, complications of prematurity vary. But the earlier your baby is born, the higher the risk of complications.

Depending on how early a baby is born, he or she may be:

- Late preterm, born between 34 and 36 completed weeks of pregnancy

- Moderately preterm, born between 32 and 34 weeks of pregnancy

- Very preterm, born at less than 32 weeks of pregnancy

- Extremely preterm, born at or before 25 weeks of pregnancy

Most premature births occur in the late preterm stage.

Products & Services

- Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

- Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to Your Baby's First Years

Symptoms

Your baby may have very mild symptoms of premature birth, or may have more-obvious complications.

Some signs of prematurity include the following:

- Small size, with a disproportionately large head

- Sharper looking, less rounded features than a full-term baby's features, due to a lack of fat stores

- Fine hair (lanugo) covering much of the body

- Low body temperature, especially immediately after birth in the delivery room, due to a lack of stored body fat

- Labored breathing or respiratory distress

- Lack of reflexes for sucking and swallowing, leading to feeding difficulties

The following tables show the median birth weight, length and head circumference of premature babies at different gestational ages for each sex.

| Weight, length and head circumference by gestational age for boys | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age | Weight | Length | Head circumference |

| 40 weeks | 7 lbs. , 15 oz. , 15 oz.(3.6 kg) | 20 in. (51 cm) | 13.8 in. (35 cm) |

| 35 weeks | 5 lbs., 8 oz. (2.5 kg) | 18.1 in. (46 cm) | 12.6 in. (32 cm) |

| 32 weeks | 3 lbs., 15.5 oz. (1.8 kg) | 16.5 in. (42 cm) | 11.6 in. (29.5 cm) |

| 28 weeks | 2 lbs., 6.8 oz. (1.1 kg) | 14.4 in. (36.5 cm) | 10.2 in. (26 cm) |

| 24 weeks | 1 lb., 6.9 oz. (0.65 kg) | 12.2 in. (31 cm) | 8.7 in. (22 cm) |

| Weight, length and head circumference by gestational age for girls | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age | Weight | Length | Head circumference |

| 40 weeks | 7 lbs. , 7.9 oz. , 7.9 oz.(3.4 kg) | 20 in. (51 cm) | 13.8 in. (35 cm) |

| 35 weeks | 5 lbs., 4.7 oz. (2.4 kg) | 17.7 in. (45 cm) | 12.4 in. (31.5 cm) |

| 32 weeks | 3 lbs., 12 oz. (1.7 kg) | 16.5 in. (42 cm) | 11.4 in. (29 cm) |

| 28 weeks | 2 lbs., 3.3 oz. (1.0 kg) | 14.1 in. (36 cm) | 9.8 in. (25 cm) |

| 24 weeks | 1 lb., 5.2 oz. (0.60 kg) | 12.6 in. (32 cm) | 8.3 in. (21 cm) |

Special care

If you deliver a preterm baby, your baby will likely need a longer hospital stay in a special nursery unit at the hospital. Depending on how much care your baby requires, he or she may be admitted to an intermediate care nursery or the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Doctors and a specialized team with training in taking care of preterm babies will be available to help care for your baby. Don't hesitate to ask questions.

Doctors and a specialized team with training in taking care of preterm babies will be available to help care for your baby. Don't hesitate to ask questions.

Your baby may need extra help feeding, and adapting immediately after delivery. Your health care team can help you understand what is needed and what your baby's care plan will be.

Request an Appointment at Mayo Clinic

Risk factors

Often, the specific cause of premature birth isn't clear. However, there are known risk factors of premature delivery, including:

- Having a previous premature birth

- Pregnancy with twins, triplets or other multiples

- An interval of less than six months between pregnancies

- Conceiving through in vitro fertilization

- Problems with the uterus, cervix or placenta

- Smoking cigarettes or using illicit drugs

- Some infections, particularly of the amniotic fluid and lower genital tract

- Some chronic conditions, such as high blood pressure and diabetes

- Being underweight or overweight before pregnancy

- Stressful life events, such as the death of a loved one or domestic violence

- Multiple miscarriages or abortions

- Physical injury or trauma

For unknown reasons, black women are more likely to experience premature birth than are women of other races. But premature birth can happen to anyone. In fact, many women who have a premature birth have no known risk factors.

But premature birth can happen to anyone. In fact, many women who have a premature birth have no known risk factors.

Complications

While not all premature babies experience complications, being born too early can cause short-term and long-term health problems. Generally, the earlier a baby is born, the higher the risk of complications. Birth weight plays an important role, too.

Some problems may be apparent at birth, while others may not develop until later.

Short-term complications

In the first weeks, the complications of premature birth may include:

-

Breathing problems. A premature baby may have trouble breathing due to an immature respiratory system. If the baby's lungs lack surfactant — a substance that allows the lungs to expand — he or she may develop respiratory distress syndrome because the lungs can't expand and contract normally.

Premature babies may also develop a lung disorder known as bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

In addition, some preterm babies may experience prolonged pauses in their breathing, known as apnea.

In addition, some preterm babies may experience prolonged pauses in their breathing, known as apnea. - Heart problems. The most common heart problems premature babies experience are patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) and low blood pressure (hypotension). PDA is a persistent opening between the aorta and pulmonary artery. While this heart defect often closes on its own, left untreated it can lead to a heart murmur, heart failure as well as other complications. Low blood pressure may require adjustments in intravenous fluids, medicines and sometimes blood transfusions.

- Brain problems. The earlier a baby is born, the greater the risk of bleeding in the brain, known as an intraventricular hemorrhage. Most hemorrhages are mild and resolve with little short-term impact. But some babies may have larger brain bleeding that causes permanent brain injury.

-

Temperature control problems.

Premature babies can lose body heat rapidly. They don't have the stored body fat of a full-term infant, and they can't generate enough heat to counteract what's lost through the surface of their bodies. If body temperature dips too low, an abnormally low core body temperature (hypothermia) can result.

Premature babies can lose body heat rapidly. They don't have the stored body fat of a full-term infant, and they can't generate enough heat to counteract what's lost through the surface of their bodies. If body temperature dips too low, an abnormally low core body temperature (hypothermia) can result.Hypothermia in a premature baby can lead to breathing problems and low blood sugar levels. In addition, a premature infant may use up all of the energy gained from feedings just to stay warm. That's why smaller premature infants require additional heat from a warmer or an incubator until they're larger and able to maintain body temperature without assistance.

- Gastrointestinal problems. Premature infants are more likely to have immature gastrointestinal systems, resulting in complications such as necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). This potentially serious condition, in which the cells lining the bowel wall are injured, can occur in premature babies after they start feeding.

Premature babies who receive only breast milk have a much lower risk of developing NEC.

Premature babies who receive only breast milk have a much lower risk of developing NEC. -

Blood problems. Premature babies are at risk of blood problems such as anemia and newborn jaundice. Anemia is a common condition in which the body doesn't have enough red blood cells. While all newborns experience a slow drop in red blood cell count during the first months of life, the decrease may be greater in premature babies.

Newborn jaundice is a yellow discoloration in a baby's skin and eyes that occurs because the baby's blood contains excess bilirubin, a yellow-colored substance, from the liver or red blood cells. While there are many causes of jaundice, it is more common in preterm babies.

- Metabolism problems. Premature babies often have problems with their metabolism. Some premature babies may develop an abnormally low level of blood sugar (hypoglycemia). This can happen because premature infants typically have smaller stores of stored glucose than do full-term babies.

Premature babies also have more difficulty converting their stored glucose into more-usable, active forms of glucose.

Premature babies also have more difficulty converting their stored glucose into more-usable, active forms of glucose. - Immune system problems. An underdeveloped immune system, common in premature babies, can lead to a higher risk of infection. Infection in a premature baby can quickly spread to the bloodstream, causing sepsis, an infection that spreads to the bloodstream.

Long-term complications

In the long term, premature birth may lead to the following complications:

- Cerebral palsy. Cerebral palsy is a disorder of movement, muscle tone or posture that can be caused by infection, inadequate blood flow or injury to a newborn's developing brain either early during pregnancy or while the baby is still young and immature.

- Impaired learning. Premature babies are more likely to lag behind their full-term counterparts on various developmental milestones. Upon school age, a child who was born prematurely might be more likely to have learning disabilities.

- Vision problems. Premature infants may develop retinopathy of prematurity, a disease that occurs when blood vessels swell and overgrow in the light-sensitive layer of nerves at the back of the eye (retina). Sometimes the abnormal retinal vessels gradually scar the retina, pulling it out of position. When the retina is pulled away from the back of the eye, it's called retinal detachment, a condition that, if undetected, can impair vision and cause blindness.

- Hearing problems. Premature babies are at increased risk of some degree of hearing loss. All babies will have their hearing checked before going home.

- Dental problems. Premature infants who have been critically ill are at increased risk of developing dental problems, such as delayed tooth eruption, tooth discoloration and improperly aligned teeth.

- Behavioral and psychological problems. Children who experienced premature birth may be more likely than full-term infants to have certain behavioral or psychological problems, as well as developmental delays.

- Chronic health issues. Premature babies are more likely to have chronic health issues — some of which may require hospital care — than are full-term infants. Infections, asthma and feeding problems are more likely to develop or persist. Premature infants are also at increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

Prevention

Although the exact cause of preterm birth is often unknown, there are some things that can be done to help women — especially those who have an increased risk — to reduce their risk of preterm birth, including:

- Progesterone supplements. Women who have a history of preterm birth, a short cervix or both factors may be able to reduce the risk of preterm birth with progesterone supplementation.

-

Cervical cerclage. This is a surgical procedure performed during pregnancy in women with a short cervix, or a history of cervical shortening that resulted in a preterm birth.

During this procedure, the cervix is stitched closed with strong sutures that may provide extra support to the uterus. The sutures are removed when it's time to deliver the baby. Ask your doctor if you need to avoid vigorous activity during the remainder of your pregnancy.

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Related

Associated Procedures

Products & Services

Preterm birth: Case definition & guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of immunisation safety data

1. Howson C.P., Kinney M.V., Lawn J. March of Dimes, PMNCH, Save the Children, WHO; 2012. Born Too Soon: the global action report on preterm birth. [Google Scholar]

2. World Health Organization . 2010. ICD-10: international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, tenth revision. [Google Scholar]

3. Spong C.Y. Defining term pregnancy: recommendations from the Defining “Term” Pregnancy Workgroup. JAMA. 2013;309:2445–2446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. ACOG Committee Opinion No 579 Definition of term pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1139–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Working party to discuss nomenclature based on gestational age and birthweight. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45:730. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Villar J., Papageorghiou A.T., Knight H.E., Gravett M.G., Iams J., Waller S.A. The preterm birth syndrome: a prototype phenotypic classification. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Wijnans L., de Bie S., Dieleman J., Bonhoeffer J., Sturkenboom M. Safety of pandemic h2N1 vaccines in children and adolescents. Vaccine. 2011;29:7559–7571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Crider K.S., Whitehead N., Buus R.M. Genetic variation associated with preterm birth: a HuGE review. Genet Med. 2005;7:593–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Blondel B., Kogan M.D., Alexander G.R., Dattani N., Kramer M.S., Macfarlane A. The impact of the increasing number of multiple births on the rates of preterm birth and low birthweight: an international study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1323–1330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1323–1330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Felberbaum R.E. Multiple pregnancies after assisted reproduction – international comparison. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;15(Suppl. 3):53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Blondel B., Macfarlane A., Gissler M., Breart G., Zeitlin J., Group P.S. Preterm birth and multiple pregnancy in European countries participating in the PERISTAT project. BJOG. 2006;113:528–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Simmons L.E., Rubens C.E., Darmstadt G.L., Gravett M.G. Preventing preterm birth and neonatal mortality: exploring the epidemiology, causes, and interventions. Semin Perinatol. 2010;34:408–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Calderon-Margalit R., Sherman D., Manor O., Kurzweil Y. Adverse perinatal outcomes among immigrant women from Ethiopia in Israel. Birth. 2015;42:125–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Segal S., Gemer O., Yaniv M. The outcome of pregnancy in an immigrant Ethiopian population in Israel. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 1996;258:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arch Gynecol Obstet. 1996;258:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Alexander G.R., Tompkins M.E., Altekruse J.M., Hornung C.A. Racial differences in the relation of birth weight and gestational age to neonatal mortality. Public Health Rep. 1985;100:539–547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Lawn J.E., McClure E.M., Blencowe H. Elsevier; 2014. Birth outcomes: a global perspective. Jekel's epidemiology, biostatistics, preventive medicine, and public health; pp. 272–287. [Google Scholar]

17. Blencowe H., Cousens S., Oestergaard M.Z., Chou D., Moller A.B., Narwal R. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet. 2012;379:2162–2172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Froen J.F., Cacciatore J., McClure E.M., Kuti O., Jokhio A.H., Islam M. Stillbirths: why they matter. Lancet. 2011;377:1353–1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Goldenberg R.L., Culhane J.F., Iams J.D., Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goldenberg R.L., Culhane J.F., Iams J.D., Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Kramer M.S., Papageorghiou A., Culhane J., Bhutta Z., Goldenberg R.L., Gravett M. Challenges in defining and classifying the preterm birth syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:108–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Goldenberg R.L., Gravett M.G., Iams J., Papageorghiou A.T., Waller S.A., Kramer M. The preterm birth syndrome: issues to consider in creating a classification system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:113–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Lawn J.E., Gravett M.G., Nunes T.M., Rubens C.E., Stanton C., Group G.R. Global report on preterm birth and stillbirth (1 of 7): definitions, description of the burden and opportunities to improve data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10(1 Suppl.):S1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Fedrick J., Anderson A.B. Factors associated with spontaneous pre-term birth. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1976;83:342–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1976;83:342–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Swamy G.K., Heine R.P. Vaccinations for pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:212–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Glezen W.P., Alpers M. Maternal immunization. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:219–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Munoz F.M. Maternal immunization: an update for pediatricians. Pediatr Ann. 2013;42:153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Fischer G.W., Ottolini M.G., Mond J.J. Prospects for vaccines during pregnancy and in the newborn period. Clin Perinatol. 1997;24:231–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Heinonen O.P., Shapiro S., Monson R.R., Hartz S.C., Rosenberg L., Slone D. Immunization during pregnancy against poliomyelitis and influenza in relation to childhood malignancy. Int J Epidemiol. 1973;2:229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Freda V.J. A preliminary report on typhoid, typhus, tetanus, and cholera immunizations during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1956;71:1134–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1956;71:1134–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Brent R.L. Risks and benefits of immunizing pregnant women: the risk of doing nothing. Reprod Toxicol. 2006;21:383–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Munoz F.M., Englund J.A. A step ahead. Infant protection through maternal immunization. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2000;47:449–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Bricks L.F. Vaccines in pregnancy: a review of their importance in Brazil. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo. 2003;58:263–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Kharbanda E.O., Vazquez-Benitez G., Lipkind H.S., Klein N.P., Cheetham T.C., Naleway A. Evaluation of the association of maternal pertussis vaccination with obstetric events and birth outcomes. JAMA. 2014;312:1897–1904. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Sukumaran L., McCarthy N.L., Kharbanda E.O., McNeil M.M., Naleway A.L., Klein N.P. Association of Tdap vaccination with acute events and adverse birth outcomes among pregnant women with prior tetanus-containing immunizations. JAMA. 2015;314:1581–1587. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

JAMA. 2015;314:1581–1587. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Lindsey B., Kampmann B., Jones C. Maternal immunization as a strategy to decrease susceptibility to infection in newborn infants. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26:248–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Zheteyeva Y.A., Moro P.L., Tepper N.K., Rasmussen S.A., Barash F.E., Revzina N.V. Adverse event reports after tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccines in pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:591e–597e. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Healy C.M. Vaccines in pregnant women and research initiatives. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55:474–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Castillo-Solorzano C., Reef S.E., Morice A., Vascones N., Chevez A.E., Castalia-Soares R. Rubella vaccination of unknowingly pregnant women during mass campaigns for rubella and congenital rubella syndrome elimination, the Americas 2001–2008. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(Suppl. 2):S713–S717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Amirthalingam G., Andrews N., Campbell H., Ribeiro S., Kara E., Donegan K. Effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in England: an observational study. Lancet. 2014;384:1521–1528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Amirthalingam G., Andrews N., Campbell H., Ribeiro S., Kara E., Donegan K. Effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in England: an observational study. Lancet. 2014;384:1521–1528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Donegan K., King B., Bryan P. Safety of pertussis vaccination in pregnant women in UK: observational study. BMJ. 2014;349:g4219. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Fell D.B., Platt R.W., Lanes A., Wilson K., Kaufman J.S., Basso O. Fetal death and preterm birth associated with maternal influenza vaccination: systematic review. BJOG. 2015;122:17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Richards J.L., Hansen C., Bredfeldt C., Bednarczyk R.A., Steinhoff M.C., Adjaye-Gbewonyo D. Neonatal outcomes after antenatal influenza immunization during the 2009 h2N1 influenza pandemic: impact on preterm birth, birth weight, and small for gestational age birth. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:1216–1222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Zaman K., Roy E. , Arifeen S.E., Rahman M., Raqib R., Wilson E. Effectiveness of maternal influenza immunization in mothers and infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1555–1564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

, Arifeen S.E., Rahman M., Raqib R., Wilson E. Effectiveness of maternal influenza immunization in mothers and infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1555–1564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Moro P.L., Broder K., Zheteyeva Y., Walton K., Rohan P., Sutherland A. Adverse events in pregnant women following administration of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine and live attenuated influenza vaccine in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, 1990–2009. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:146 e1–e1467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Brydak L.B., Nitsch-Osuch A. Vaccination against influenza in pregnant women. Acta Biochim Pol. 2014;61:589–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Steinhoff M.C., MacDonald N., Pfeifer D., Muglia L.J. Influenza vaccine in pregnancy: policy and research strategies. Lancet. 2014;383:1611–1613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Munoz F.M., Greisinger A.J., Wehmanen O.A., Mouzoon M.E., Hoyle J.C., Smith F.A. Safety of influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1098–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2005;192:1098–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Guidelines for Vaccinating Pregnant Women . 2014. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Guidelines for vaccinating pregnant women from the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices (ACIP) [Google Scholar]

49. Ballantyne J.W. Antenatal clinics and prematernity practice at the Edinburgh Royal Maternity Hospital in the years 1909–1915. Br Med J. 1916;1:189–192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Ballantyne J.W. The problem of the premature infant. Br Med J. 1902;1:1196–1200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Phelps D.L., Brown D.R., Tung B., Cassady G., McClead R.E., Purohit D.M. 28-day survival rates of 6676 neonates with birth weights of 1250 grams or less. Pediatrics. 1991;87:7–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Berkowitz G.S. An epidemiologic study of preterm delivery. Am J Epidemiol. 1981;113:81–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Battaglia F.C., Lubchenco L. O. A practical classification of newborn infants by weight and gestational age. J Pediatr. 1967;71:159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

O. A practical classification of newborn infants by weight and gestational age. J Pediatr. 1967;71:159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Tucker J., McGuire W. Epidemiology of preterm birth. BMJ. 2004;329:675–678. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Villar J., Cheikh Ismail L., Victora C.G., Ohuma E.O., Bertino E., Altman D.G. International standards for newborn weight, length, and head circumference by gestational age and sex: the Newborn Cross-Sectional Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Lancet. 2014;384:857–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Salomon L.J., Bernard J.P., Ville Y. Estimation of fetal weight: reference range at 20–36 weeks’ gestation and comparison with actual birth-weight reference range. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29:550–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Geerts L.T., Brand E.J., Theron G.B. Routine obstetric ultrasound examinations in South Africa: cost and effect on perinatal outcome – a prospective randomised controlled trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103:501–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103:501–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Blencowe H., Cousens S., Chou D., Oestergaard M., Say L., Moller A.B. Born too soon: the global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod Health. 2013;10(1 Suppl.):S2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Wilcox A.J. On the importance – and the unimportance – of birthweight. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1233–1241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Gardosi J., Chang A., Kalyan B., Sahota D., Symonds E.M. Customised antenatal growth charts. Lancet. 1992;339:283–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Gardosi J., Mongelli M., Wilcox M., Chang A. An adjustable fetal weight standard. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1995;6:168–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Papageorghiou A.T., Ohuma E.O., Altman D.G., Todros T., Cheikh Ismail L., Lambert A. International standards for fetal growth based on serial ultrasound measurements: the Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Lancet. 2014;384:869–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lancet. 2014;384:869–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Cooke R.W. Conventional birth weight standards obscure fetal growth restriction in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92:F189–F192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Hutcheon J.A., Zhang X., Cnattingius S., Kramer M.S., Platt R.W. Customised birthweight percentiles: does adjusting for maternal characteristics matter. BJOG. 2008;115:1397–1404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Hutcheon J.A., Platt R.W. The missing data problem in birth weight percentiles and thresholds for small-for-gestational-age. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:786–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Bethesda MEKSNIoCHaHD. Preterm Labor and Birth: Overview.

67. Blackmore C.A., Rowley D.L., Kiely J.L. From data to action: CDC's public health surveillance for women, infants and children. US Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1994. Preterm birth. [Google Scholar]

Preterm birth. [Google Scholar]

68. Fleischman A.R., Oinuma M., Clark S.L. Rethinking the definition of term pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:136–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Pereira A.P., Dias M.A., Bastos M.H., da Gama S.G., Leal Mdo C. Determining gestational age for public health care users in Brazil: comparison of methods and algorithm creation. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Rosenberg R.E., Ahmed A.S., Ahmed S., Saha S.K., Chowdhury M.A., Black R.E. Determining gestational age in a low-resource setting: validity of last menstrual period. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009;27:332–338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Ellertson C., Elul B., Ambardekar S., Wood L., Carroll J., Coyaji K. Accuracy of assessment of pregnancy duration by women seeking early abortions. Lancet. 2000;355:877–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Bracken H., Clark W., Lichtenberg E.S., Schweikert S.M., Tanenhaus J., Barajas A. Alternatives to routine ultrasound for eligibility assessment prior to early termination of pregnancy with mifepristone-misoprostol. BJOG. 2011;118:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Alternatives to routine ultrasound for eligibility assessment prior to early termination of pregnancy with mifepristone-misoprostol. BJOG. 2011;118:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. DiPietro J.A., Allen M.C. Estimation of gestational age: implications for developmental research. Child Dev. 1991;62:1184–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Chauhan K.P. Assessment of symphysio-fundal height (SFH) and its implication during antenatal period. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2:363–366. [Google Scholar]

75. Yang H., Kramer M.S., Platt R.W., Blondel B., Breart G., Morin I. How does early ultrasound scan estimation of gestational age lead to higher rates of preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:433–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Goldenberg R.L., Davis R.O., Cutter G.R., Hoffman H.J., Brumfield C.G., Foster J.M. Prematurity, postdates, and growth retardation: the influence of use of ultrasonography on reported gestational age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:462–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1989;160:462–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Blondel B., Morin I., Platt R.W., Kramer M.S., Usher R., Breart G. Algorithms for combining menstrual and ultrasound estimates of gestational age: consequences for rates of preterm and postterm birth. BJOG. 2002;109:718–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Breart G., Blondel B., Tuppin P., Grandjean H., Kaminski M. Did preterm deliveries continue to decrease in France in the 1980. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1995;9:296–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Henriksen T.B., Wilcox A.J., Hedegaard M., Secher N.J. Bias in studies of preterm and postterm delivery due to ultrasound assessment of gestational age. Epidemiology. 1995;6:533–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Kramer M.S., McLean F.H., Boyd M.E., Usher R.H. The validity of gestational age estimation by menstrual dating in term, preterm, and postterm gestations. JAMA. 1988;260:3306–3308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Rowlands S., Royston P. Estimated date of delivery from last menstrual period and ultrasound scan: which is more accurate. Br J Gen Pract. 1993;43:322–325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Br J Gen Pract. 1993;43:322–325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Buekens P., Delvoye P., Wollast E., Robyn C. Epidemiology of pregnancies with unknown last menstrual period. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1984;38:79–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. Gardosi J., Geirsson R.T. Routine ultrasound is the method of choice for dating pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:933–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84. Farr V., Kerridge D.F., Mitchell R.G. The value of some external characteristics in the assessment of gestational age at birth. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1966;8:657–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85. Dubowitz L.M., Dubowitz V., Goldberg C. Clinical assessment of gestational age in the newborn infant. J Pediatr. 1970;77:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. Mitchell D. Accuracy of pre- and postnatal assessment of gestational age. Arch Dis Child. 1979;54:896–897. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Parkin J. M., Hey E.N., Clowes J.S. Rapid assessment of gestational age at birth. Arch Dis Child. 1976;51:259–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

M., Hey E.N., Clowes J.S. Rapid assessment of gestational age at birth. Arch Dis Child. 1976;51:259–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. Ounsted M.K., Chalmers C.A., Yudkin P.L. Clinical assessment of gestational age at birth: the effects of sex, birthweight, and weight for length of gestation. Early Hum Dev. 1978;2:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89. Capurro H., Konichezky S., Fonseca D., Caldeyro-Barcia R. A simplified method for diagnosis of gestational age in the newborn infant. J Pediatr. 1978;93:120–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

90. Dubowitz L.M., Dubowitz V., Palmer P., Verghote M. A new approach to the neurological assessment of the preterm and full-term newborn infant. Brain Dev. 1980;2:3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91. Farr V., Mitchell R.G., Neligan G.A., Parkin J.M. The definition of some external characteristics used in the assessment of gestational age in the newborn infant. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1966;8:507–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Spinnato J.A., Sibai B.M., Shaver D.C., Anderson G.D. Inaccuracy of Dubowitz gestational age in low birth weight infants. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;63:491–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Spinnato J.A., Sibai B.M., Shaver D.C., Anderson G.D. Inaccuracy of Dubowitz gestational age in low birth weight infants. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;63:491–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93. von Voss H., Trampisch H.J., Grittern M. Simple and practical method for the determination of gestational age of newborns. J Perinat Med. 1985;13:207–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

94. Nicolopoulos D., Perakis A., Papadakis M., Alexiou D., Aravantinos D. Estimation of gestational age in the neonate: a comparison of clinical methods. Am J Dis Child. 1976;130:477–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

95. Eregie C.O. A new method for maturity determination in newborn infants. J Trop Pediatr. 2000;46:140–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96. Ballard J.L., Novak K.K., Driver M. A simplified score for assessment of fetal maturation of newly born infants. J Pediatr. 1979;95:769–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. Verhoeff F.H., Milligan P., Brabin B.J., Mlanga S., Nakoma V. Gestational age assessment by nurses in a developing country using the Ballard method, external criteria only. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1997;17:333–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ann Trop Paediatr. 1997;17:333–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98. Ballard J.L., Khoury J.C., Wedig K., Wang L., Eilers-Walsman B.L., Lipp R. New Ballard Score, expanded to include extremely premature infants. J Pediatr. 1991;119:417–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

99. International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). Guidelines for Clinical Safety assessment (E2a–e).

100. Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS). Reporting form for International Reporting of Adverse Drug Reactions.

101. Schulz K.F., Altman D.G., Moher D.S., Group C. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c332. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

102. Moher D., Cook D.J., Eastwood S., Olkin I., Rennie D., Stroup D.F. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of reporting of meta-analyses. Lancet. 1999;354:1896–1900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Quality of reporting of meta-analyses. Lancet. 1999;354:1896–1900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

103. Stroup D.F., Berlin J.A., Morton S.C., Olkin I., Williamson G.D., Rennie D. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Features of adaptation and development of premature babies. Doctor Plus Medical Center

The first year of a child's life is characterized by the most intensive growth and rapid development. But during this period, the body is extremely vulnerable, the defenses are weak and imperfect. This is especially true for children who were born prematurely and are considered premature.

Premature are children born at gestational age from 28 to 37 completed weeks, weighing from 1000 - 2500 grams, height 35 - 45 cm.

The reasons for their premature birth are varied: too young age and, accordingly, the mother's body; hemolytic disease of the fetus, which develops as a result of Rhesus conflict; pathological (not normal) course of pregnancy; previous abortions, illness, physical and mental trauma; harmful working conditions, the use of nicotine and alcohol.

What a premature baby looks like. Anatomical and physiological signs.

There are 4 degrees of prematurity, depending on the weight of the child:

Grade 1: 2500 -2001 grams Grade 3: 1500 - 1001 grams

Grade 2: 2000 – 1500 grams Grade 4: 1000 grams or less.

Since body weight may or may not correspond to the gestational age at the time of birth, premature babies are divided into 2 groups also according to these signs

• children whose physical development corresponds to the gestational age at the time of birth;

In premature babies, the subcutaneous fat layer is not sufficiently developed, i.e. they suffer more from overheating and hypothermia. The skin is thin, dry, wrinkled, abundantly covered with fluff. Insufficient maturity of blood vessels is manifested by the Harlequin symptom. If you put the baby on its side, the skin acquires a contrasting pink color.

The bones of the skull are malleable, not only a large, but also a small fontanel is open.

The auricles are soft - the cartilage in them has not yet formed, they are pressed to the head, and not separated from it, as in full-term ones.

The nails do not reach the edge of the phalanges of the fingers, the umbilical cord is located below the middle of the body, and not in the center.

The underdevelopment of the genital organs is indicative: in girls, the labia minora are not covered by the large ones. In boys, the testicles are not descended into the scrotum.

The child sucks badly, swallows with difficulty. The cry is weak, breathing is not rhythmic. Physiological jaundice often lasts up to 3-4 weeks.

The umbilical cord falls off much later, and the umbilical wound heals more slowly.

It has its own characteristics and physiological weight loss. It is restored only by 2-3 weeks of life, and the timing of weight recovery is directly dependent on the maturity of the child, i.e. not only the date of his birth, but also the degree of adaptation of the baby to environmental conditions.

In premature babies, the nerve centers that regulate the rhythm of breathing are not fully formed. The formation of lung tissue has not been completed, in particular, a substance that prevents the “falling off” of the lungs - Surfactant. Therefore, their respiratory rate is not constant. With anxiety, it reaches 60-80 in 1 minute, at rest and during sleep it becomes less frequent, respiratory arrests may even be observed. The expansion of the lungs due to an insufficient amount of Surfactant is slowed down, and respiratory failure may occur.

The heart rate also depends on the condition of the child and environmental conditions. With an increase in the ambient temperature and the child's anxiety, the heart rate increases to 200 beats per minute.

In premature newborns, asphyxia and cerebral hemorrhage occur more often. They are more likely to suffer from acute respiratory diseases, intestinal infections, which is due to weak immunity and insufficient development of many adaptive reactions.

These babies are more likely than full-term babies to develop anemia (anemia).

Especially during the period when intensive growth and weight gain begins (2-3 months). With proper nutrition of the child and the mother, if she breastfeeds, these phenomena quickly pass. In the case when anemia is of a protracted nature, it is necessary to prescribe iron preparations.

The further development of the child is determined not only by the degree of prematurity, but also in many respects, by the state of his health for a given period of time.

If the child is practically healthy, from the 2nd month of life, he gains weight and height in the same way as full-term ones. By the end of the 1st year, the weight increases by 5-10 times compared to the weight at birth.

The average height is 70-77 cm.

The nervous system of premature babies is also more immature. The development of various skills, their intellectual development lags behind by 1-2 months.

These children sit down later, start walking later, they may have anomalies in the structure of the foot, curvature of the legs, and spine. If children are born very premature and often get sick, their development slows down by about a year. In the future, it levels off, approximately to preschool age.

If you have suffered intrauterine malnutrition, i.e. the nutrition of the fetus was disturbed for some reason - diseases of the mother, anomalies in the development of the child itself, anomalies in the development of the umbilical cord and placenta, then its central nervous system can recover for a long time (therefore, the observation of a neurologist is very important).

There may be lability of the nervous system (mood changes easily, often gives in to emotions, conflicts with other people are not uncommon), night terrors, enuresis (urinary incontinence), lack of appetite, a tendency to nausea.

However, in general, premature babies grow up as quite normal people.

Care of a premature baby after discharge from the maternity hospital.

For a child born prematurely, dispensary observation is established at the place of residence up to 7 years.

Periodic consultations of specialists are obligatory, first of all - a neurologist, as well as a surgeon, an otolaryngologist, an ophthalmologist

From the age of 2-4 weeks, rickets is prevented (ultraviolet

irradiation - quartzization, the addition of vitamin D to food, massage, hardening).

The most adequate type of nutrition for a premature baby is breastfeeding. But given that the baby can suck out an insufficient amount of breast milk, you can supplement it with expressed milk or adapted mixtures.

From 4 months - vegetable purees, 5 months. - porridge, 6 months. - give meat soufflé.

Correction of protein and fat deficiency is carried out by adding the required amount of kefir and cottage cheese, starting with 5 ml, gradually increasing the dosage.

The room in which a premature baby lives should be bright, dry and thoroughly ventilated. The optimum room temperature is 20-22 *. S. Walks are very important. Sufficient exposure to fresh air prevents the development of pathological conditions.

In winter, walks start from the age of 2 months at an air temperature not lower than -8, -10*C. The duration of the walk is from 15 minutes to 2 hours. In summer, a child can spend all the intervals between feedings during the day in the fresh air. On windy, rainy and very hot days (more than 30*C), it is better for children to sleep indoors with windows open or on the veranda.

Daily warm baths are helpful. When bathing premature babies, the water temperature should be at least 37*C.

Vaccination of premature babies is carried out strictly according to an individual schedule, it depends on the state of health, physical and neuropsychic development of the child.

When organizing care for a child born prematurely, one should take into account the functional characteristics of the body.

In conclusion, let us say: as long-term observations show, despite all the peculiarities, with good care, due attention of parents and doctors, premature babies develop successfully and after a year they catch up with their peers.

Your baby was born prematurely | Regional Perinatal Center

Premature babies

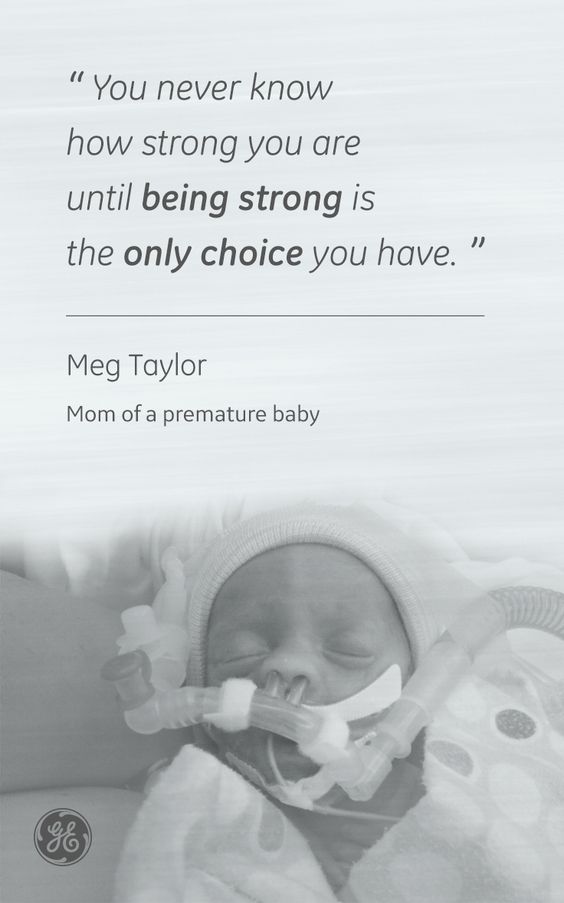

If your baby is born too early, the joy of having a baby can be overshadowed by health concerns and thoughts about the possible consequences.

Instead of returning home with the baby, holding him and caressing him, you will have to stay in the department, learn to cope with the fear of touching the baby, realize the need for treatment and various manipulations, get used to the complex equipment that surrounds him.

In this situation, not only your baby needs help, you need it too! The best assistants are your loved ones, their love and care, as well as professional advice and recommendations from doctors and psychologists. This section of articles will help you improve your knowledge of preterm infant care, development and nutrition.

This section of articles will help you improve your knowledge of preterm infant care, development and nutrition.

Your help for the baby

Previously, parents were often not allowed into the neonatal unit and, especially, into the intensive care unit because of the fear of infection of the baby, but now the contact of the parent with the child is recognized as desirable and is prohibited only in exceptional cases (for example, if parents have acute infections)

Close communication between you and your baby is very important from the first days of his life. Even very immature premature babies recognize the voices and feel the touch of their parents.

The newborn needs this contact. Studies have shown that it greatly contributes to the faster adaptation of an immature child to new conditions and the stabilization of his condition. The baby's resistance to therapy increases, he absorbs large amounts of food and quickly begins to suck on his own. Contact with the child is important for parents. Taking part in the care of the baby, they feel their involvement in what is happening and quickly get used to a new role, especially when they see how he reacts to their presence.

Contact with the child is important for parents. Taking part in the care of the baby, they feel their involvement in what is happening and quickly get used to a new role, especially when they see how he reacts to their presence.

By constantly and attentively observing the baby, parents can notice the smallest changes in his condition before others. In addition, communication in the hospital is a good practice that will undoubtedly come in handy after discharge. For parents, early physical contact with the baby is very valuable, because it allows them to feel him, despite the incubator and other obstacles, and show him their love.

Treatment in the neonatal intensive care unit requires parents to have full confidence in all medical staff.

Nursing premature babies in the hospital

Many premature babies cannot breathe, suckle and regulate their body temperature sufficiently after birth. Only in the last weeks of pregnancy is the maturation of the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, brain, which regulates and coordinates the work of all organs and systems.

Constant attention requires fluid loss due to the immaturity of the skin of premature babies and the insufficiency of thermoregulation processes. Modern approaches focused on nursing premature babies help to cope with these problems.

Heat regulation incubator

Premature babies are very susceptible to temperature fluctuations. At the same time, clothing can interfere with the monitoring of the baby's condition and its treatment. That is why an incubator is used to provide the conditions necessary for premature babies. It maintains a certain temperature and humidity, which change as the child grows. When the body weight of a premature infant reaches 1500-1700 g, he can be transferred to a heated bed, and after reaching a weight of 2000, most premature babies can do without this support. There are no strict rules here: when nursing children with low body weight, doctors are guided by the severity of the condition of each premature baby and its degree of maturity.

In incubators, very young premature babies are placed in special "nests" - soft hemispheres in which the baby feels comfortable and assumes a position close to intrauterine. It must be protected from bright lights and loud noises. For this purpose, special screens and coatings are used.

Critical treatments during the first days of life of premature babies with low and very low birth weight:

Use of an incubator or heated bed.

Oxygen supply for respiratory support.

If necessary, artificial ventilation of the lungs or breathing using the CPAP system.

Intravenous administration of various drugs and fluids.

Carrying out parenteral nutrition with solutions of amino acids, glucose and fat emulsions.

Don't worry: not all premature babies need such extensive treatment!

Mechanical ventilation and CPAP for respiratory support

When it comes to nursing, oxygen supply is of the utmost importance for premature babies. In a child born before the 34-35th week of pregnancy, the ability of the lungs to work independently is not yet sufficiently developed. The use of a constant flow of air with oxygen, which maintains a positive airway pressure (CPAP), leads to an increase in blood oxygen saturation.

In a child born before the 34-35th week of pregnancy, the ability of the lungs to work independently is not yet sufficiently developed. The use of a constant flow of air with oxygen, which maintains a positive airway pressure (CPAP), leads to an increase in blood oxygen saturation.

This new method made it possible to dispense with the majority of even very immature children without mechanical ventilation. The need for intubation of children has disappeared: during treatment with CPAP, oxygen is supplied through short tubes - cannulas that are inserted into the nasal passages. CPAP or mechanical ventilation is continued until the lungs can function at full capacity on their own.

In order for the lungs to expand and remain in this state in the future, a surfactant is needed - a substance that lines the alveoli from the inside and reduces surface tension. Surfactant is produced in sufficient quantities starting from the 34-35th week of pregnancy. Basically, it is by this time that the formation of the lungs is completed. If the baby was born earlier, modern technologies allow the introduction of surfactant into the lungs of premature babies immediately after their birth.

If the baby was born earlier, modern technologies allow the introduction of surfactant into the lungs of premature babies immediately after their birth.

Parenteral nutrition - giving nutrient solutions by vein

Premature babies, especially those born weighing less than 1500 g, are not able to get and absorb enough nutrients, even when fed through a tube. For the rapid growth of the baby, a large amount of nutrition is needed, and the size of the stomach is still very small, and the activity of digestive enzymes is also reduced. Therefore, such children are given parenteral nutrition.

Special nutrients are injected into a vein using infusion pumps that deliver solutions slowly at a predetermined rate. In this case, amino acids necessary for building proteins, fat emulsions and glucose, which are sources of energy, are used. These substances are also used for the synthesis of a number of hormones, enzymes and other biologically active substances. Additionally, minerals and vitamins are introduced.

Additionally, minerals and vitamins are introduced.

Gradually, the volume of enteral nutrition increases, and parenteral nutrition decreases until it is completely canceled.

Premature infants with gastrointestinal disease require parenteral nutrition for a longer period of time.

By the time your grown baby is discharged from the hospital, everything should be well prepared at home. And this applies not only to the environment, clothes and means of caring for the child.

All family members must be ready to receive the baby. Of course, the main care will fall on the shoulders of the parents. Although you have already gained some experience in the hospital, it is important to feel the support of others, especially in the early days.

Older children can also help. The discharge of your baby is a great joy that you want to share with all your relatives.

While you are getting used to your new role, it is important that nothing distracts you from communicating with your child. Now all the care and responsibility for the baby lies entirely with you. Everything you need to take care of him should be at hand.

Now all the care and responsibility for the baby lies entirely with you. Everything you need to take care of him should be at hand.

Getting ready to be discharged from the hospital

Before you are discharged, you must make sure that:

- A crib, a bathtub and a place for changing clothes are prepared, and preferably a changing table. A crib should be placed in the parents' bedroom, the child should not be left alone even at night. A stroller is also required. you have baby milk that was recommended by the doctor before discharge (if the child is on mixed or artificial feeding). As a rule, this is a specialized medical product. You need a certain number of small bottles and teats of the appropriate size, as well as a sterilizer. All premature babies will need pacifiers.

- You have fully mastered breastfeeding or bottle feeding.

- If your baby is not suckling all the required amount of milk from the breast and is supplementing from a bottle, you have purchased a breast pump that you have learned to use; you may also need it if you have a lot of breast milk.

- You have asked your doctor how often your child's weight should be monitored.

- If your baby still needs medicines, you have enough medicines at home. And you know exactly how and when to give them to your child.

- You know which warning signs to look out for.

- After the baby is discharged, a pediatrician and a neonatologist will look after the baby, to whom you will give the discharge summary from the hospital.

- You know how the hospital from which your child is being discharged will provide follow-up care after discharge.

- You know which specialists and how often should examine your baby (oculist, neuropathologist, etc.).

- All the emergency phone numbers you need are at your fingertips.

When can a child go home

This question is very difficult to answer because all children are different. The stay in the hospital can last from 6 days to 6 months, depending on the degree of prematurity of the child, the severity of his condition, as well as the presence of certain complications.

Of course, all parents look forward to the moment when the baby can be brought home. Long-term nursing of a premature baby is often a difficult test for you. But we must not forget that safety comes first, and the baby can be discharged home only when the doctors are confident in the stability of his condition. It is certainly in your interest as well.

The rate of increase in body weight and length

Weight gain is the main indicator of the growth of the baby and the adequacy of the treatment. The weight of the child, especially in the first days and weeks of life, is influenced by a number of factors: the presence of milk in the stomach (immediately after feeding), the time of bowel movement, the degree of filling of the bladder, the presence of edema. Therefore, if an edematous child does not gain weight for several days, and perhaps even loses it, do not worry. It should be remembered that children grow unevenly and periods of high weight gain alternate with lower ones. It is better to focus not on weight gain per day, but on the dynamics of this indicator over several days or a week.

It is better to focus not on weight gain per day, but on the dynamics of this indicator over several days or a week.

It is currently accepted that in the interval corresponding to 28-34 weeks of pregnancy, the normal weight gain of the child is 16-20 g/kg per day. Then it is reduced to 15 g/kg.

It is also important to take into account the rate of increase in body length. With malnutrition, at first the child gains less weight (or even loses it), and with a more pronounced deficiency of nutrients, his growth is also disturbed.

The weight must not only increase at a certain rate, but must also correspond to the length of the baby. An important parameter characterizing the development of the baby is an increase in the circumference of the head. The brain most actively increases in size during the first 12–18 months of life. But an excessively rapid increase in head circumference, as well as a slowdown in its increase, indicate neurological disorders.

A premature baby can be discharged from the hospital if:

- he is able to independently maintain the required body temperature;

- does not need breathing support and constant monitoring of the work of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems;

- can suck out the required amount of nutrition on its own;

- does not need round-the-clock monitoring and frequent determination of biochemical or other indicators;

- maintenance treatment can be done at home;

- he will be under the supervision of a local pediatrician and neonatologist at the place of residence.

The decision to discharge home is made for each patient individually. In addition to the state of health of the baby, the degree of preparedness of parents, their ability to provide high-level care for a premature baby is also taken into account.

Feeding a premature baby after discharge

Breastfeeding is the ideal way to feed premature babies.

However, if the baby was born much premature and his birth weight did not exceed 1800-2000 g, his high nutritional requirements cannot be met by breastfeeding. The growth rate will be insufficient. Moreover, over time, the content of many nutrients, including protein, in milk decreases. And it is the main material for building organs, and primarily brain tissue. Therefore, proteins must be supplied to the body of a premature infant in the optimal amount.

In addition, premature babies have a significantly increased need for calcium and phosphorus, which are essential for bone formation.

In order for the baby's nutrition to be complete even after being discharged from the hospital, special additives - "enrichers" are introduced into breast milk in a certain amount, already less than in the hospital. They make up for the lack of protein in it, as well as some vitamins and minerals. As a result, the child receives them in the optimal amount. The duration of their use will be determined by your doctor. If there is not enough milk or it does not exist at all, children born prematurely should be transferred to artificial feeding. Complementary feeding of premature babies is carried out with special children's dairy products designed for children with low birth weight. This baby milk is ideally suited to both the ability of immature children to digest and assimilate nutrients, and their needs.

Premature infant milk contains more protein, fat and carbohydrates than term infant milk, resulting in a higher calorie content. In specialized baby milk, the concentration of many minerals is higher, especially iron, zinc, calcium, phosphorus, as well as vitamins, including vitamin D. Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids of the Omega-3 and Omega-6 classes are introduced into such products, which are necessary for proper development of the brain and organ of vision, as well as nucleotides that contribute to the optimal development of immunity. However, when the child reaches a certain weight (2000-2500 g), you should gradually switch to feeding with standard baby milk, but not completely. Specialized baby milk can be present in the diet of a premature baby for several months. This time, as well as the volume of the product, will be determined by the doctor. He will answer all your questions about how to feed your baby.

Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids of the Omega-3 and Omega-6 classes are introduced into such products, which are necessary for proper development of the brain and organ of vision, as well as nucleotides that contribute to the optimal development of immunity. However, when the child reaches a certain weight (2000-2500 g), you should gradually switch to feeding with standard baby milk, but not completely. Specialized baby milk can be present in the diet of a premature baby for several months. This time, as well as the volume of the product, will be determined by the doctor. He will answer all your questions about how to feed your baby.

At present, specialized children's dairy products have been developed and used to feed premature babies after discharge from the hospital. In its composition, it occupies an intermediate position between a specialized product for premature babies and regular baby milk. Your baby will be transferred to such baby milk while still in the hospital. You will continue to give it to your child at home, and the doctor, watching him, will tell you when it will be possible to switch to regular standard baby milk. If the baby was born with a very low body weight or is not gaining weight well, special baby milk can be used for a long time - up to 4 months, 6 or even 9months. The beneficial effect of such children's dairy products on the growth and development of the child has been proven in scientific studies.

You will continue to give it to your child at home, and the doctor, watching him, will tell you when it will be possible to switch to regular standard baby milk. If the baby was born with a very low body weight or is not gaining weight well, special baby milk can be used for a long time - up to 4 months, 6 or even 9months. The beneficial effect of such children's dairy products on the growth and development of the child has been proven in scientific studies.

Feeding needs for premature babies

Higher caloric intake because they need to gain weight faster than term babies.

More protein as premature babies grow faster.

More calcium and phosphorus for bone building.

More trace elements and vitamins for growth and development.

A premature baby grows faster than a term baby. Nutrition for such children is calculated taking into account body weight at birth, the age of the baby and its growth rate. As a rule, the calorie content of the daily diet is about 120-130 calories per 1 kg of body weight.