Trisomy 21 screening

Screening for Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome

You will be offered a screening test for Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome between 10 and 14 weeks of pregnancy. This is to assess your chances of having a baby with one of these conditions.

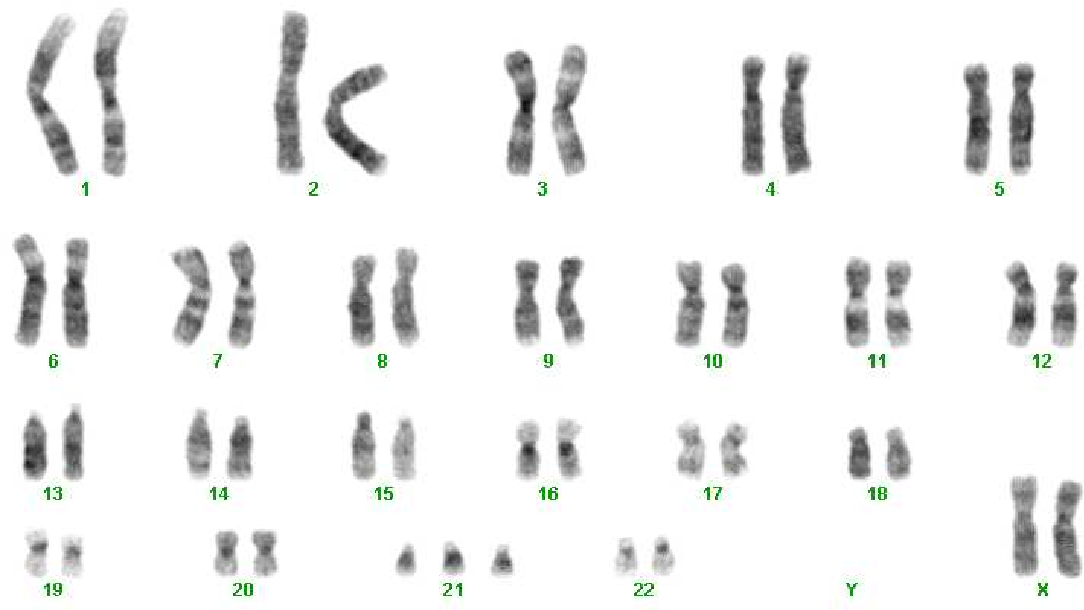

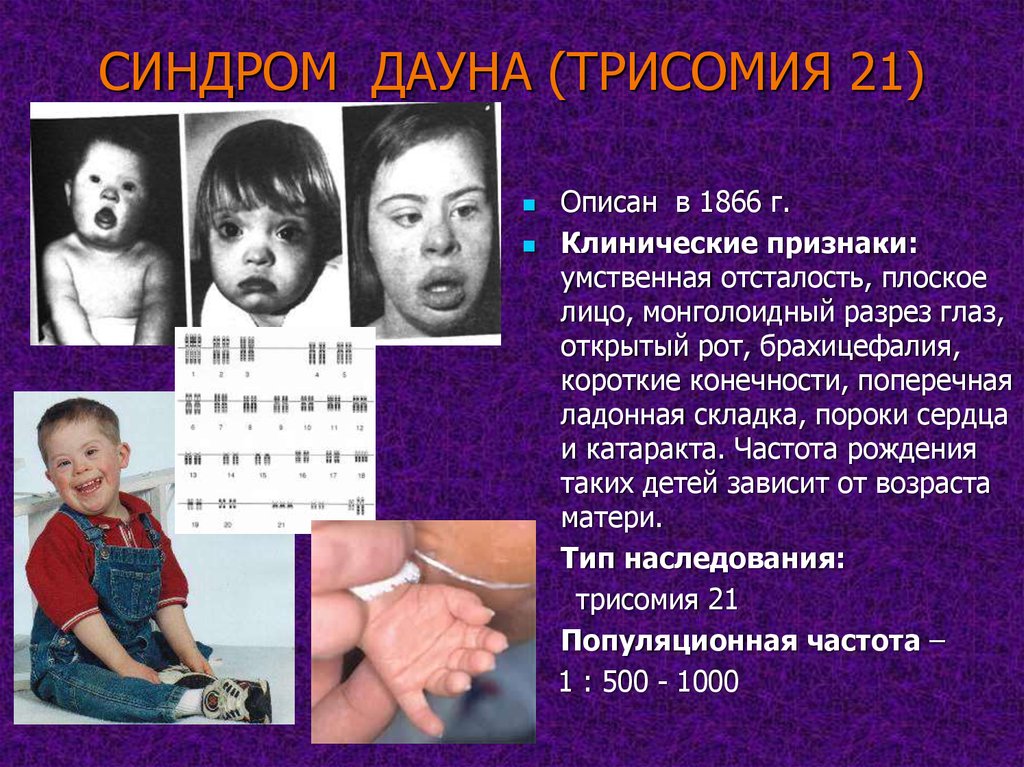

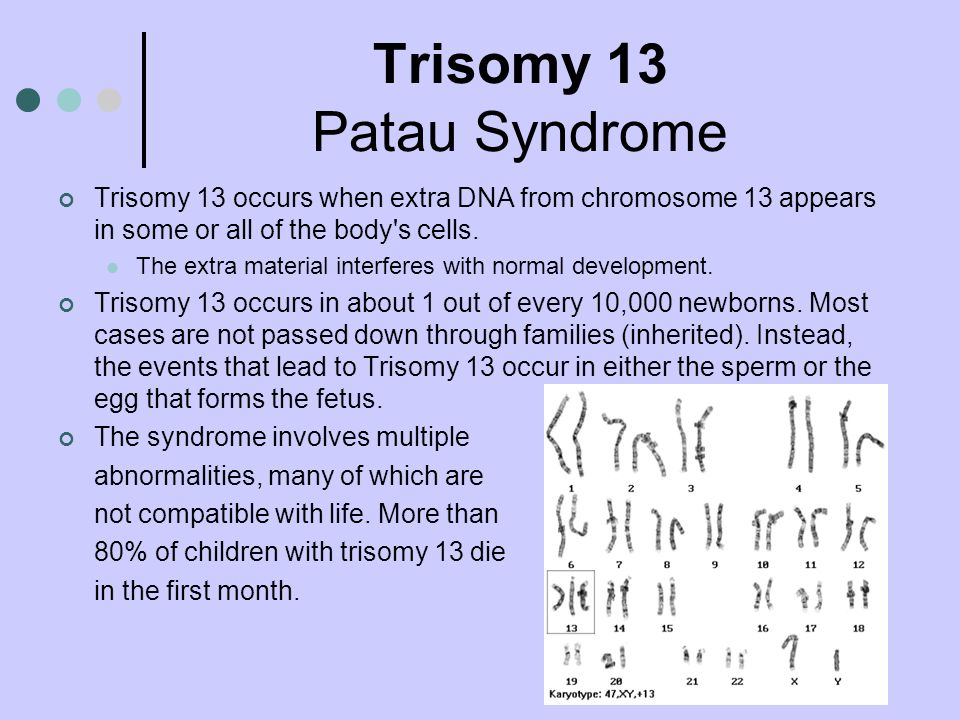

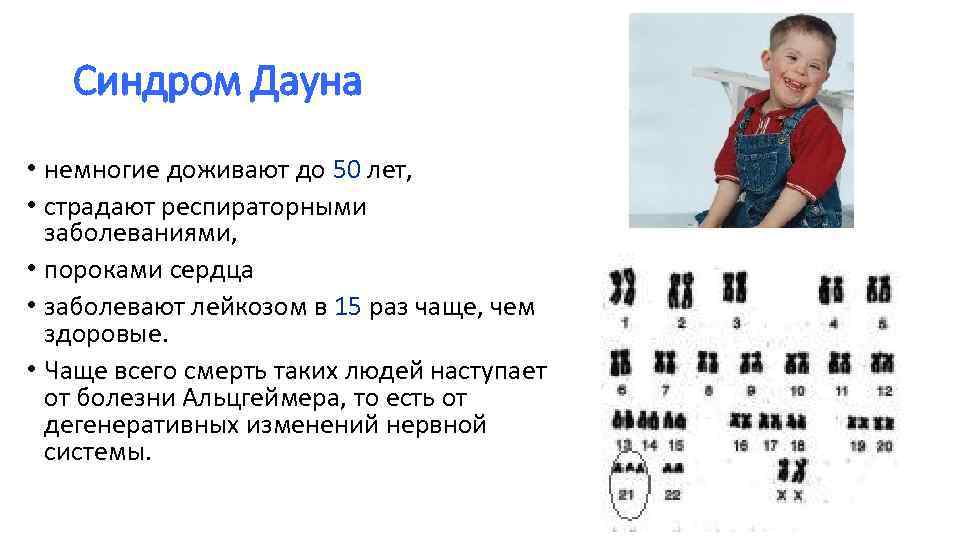

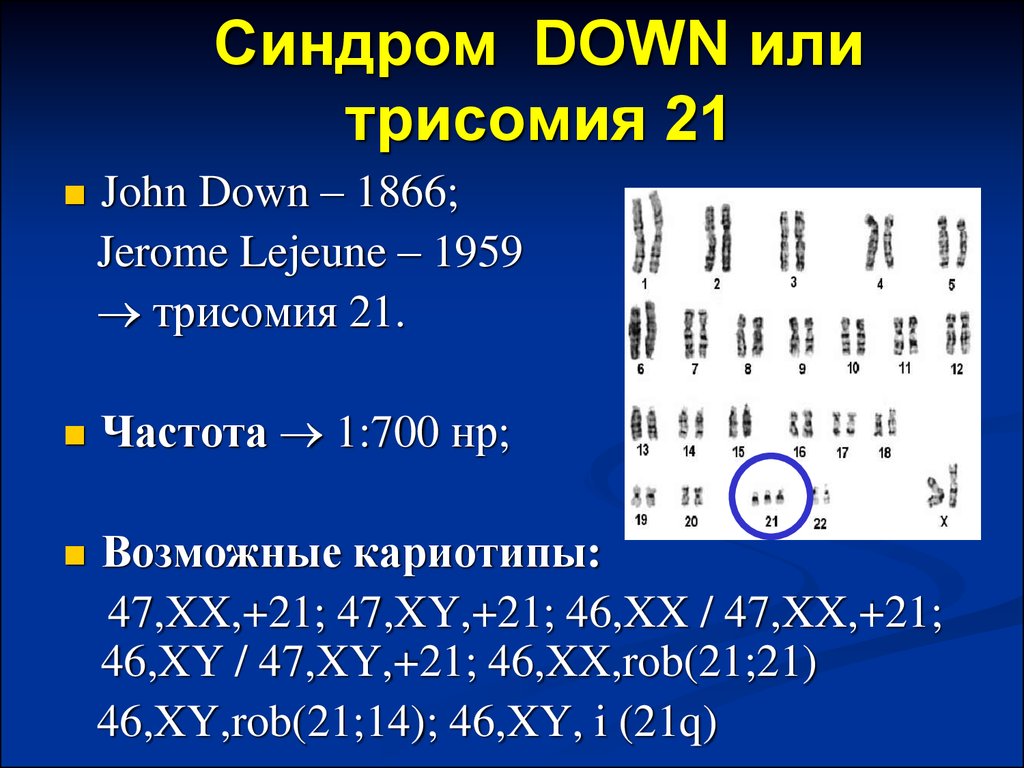

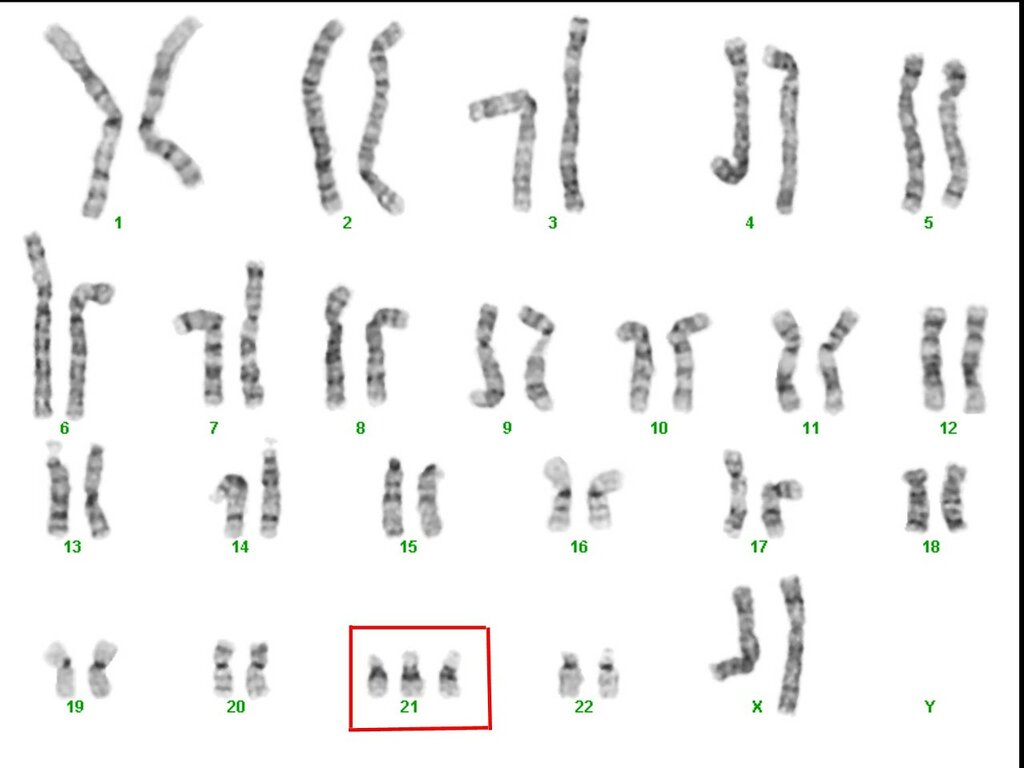

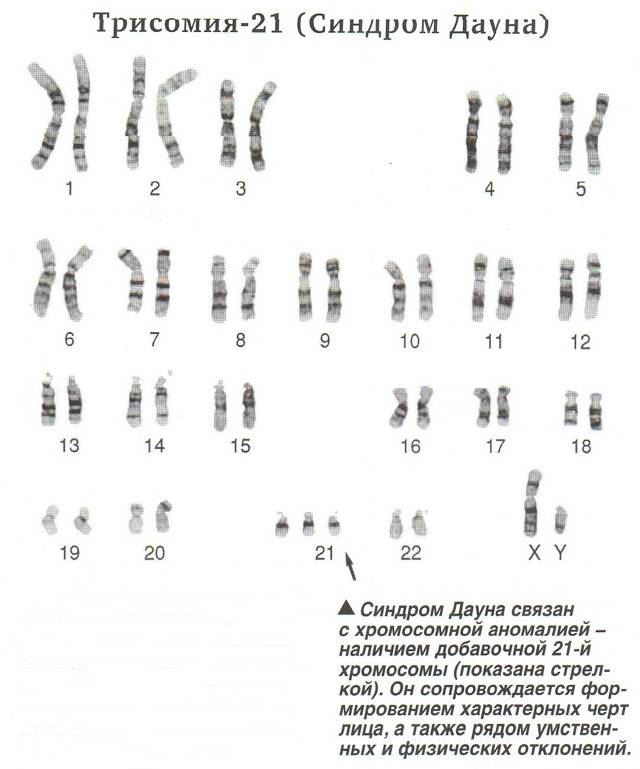

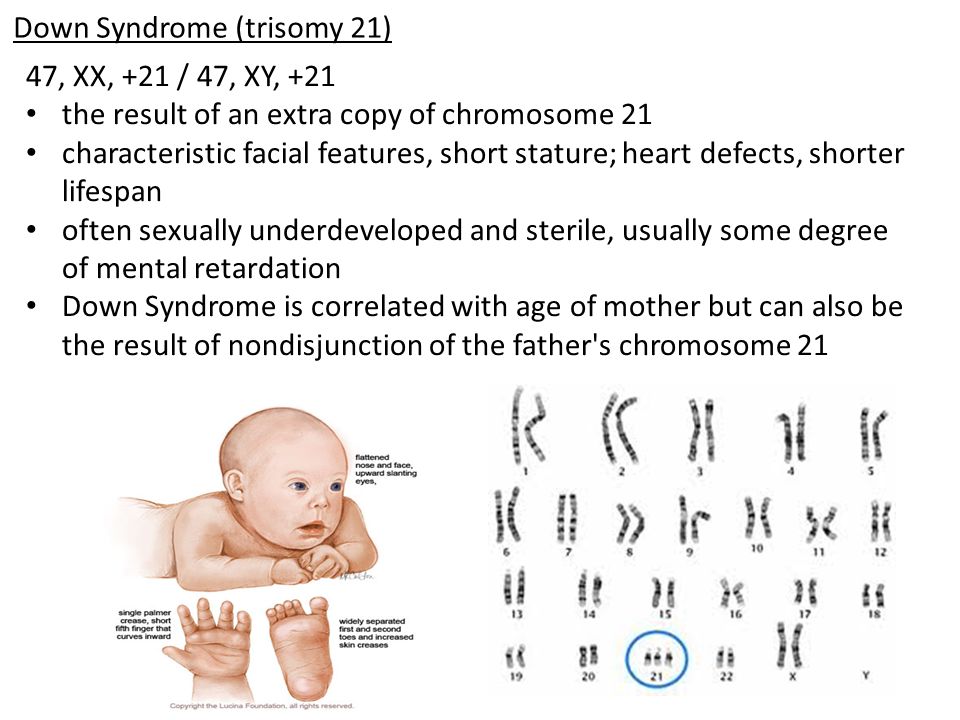

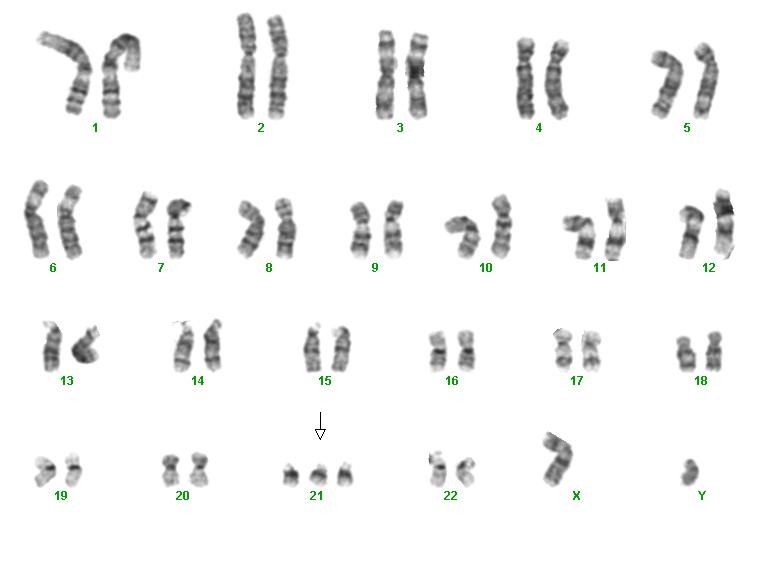

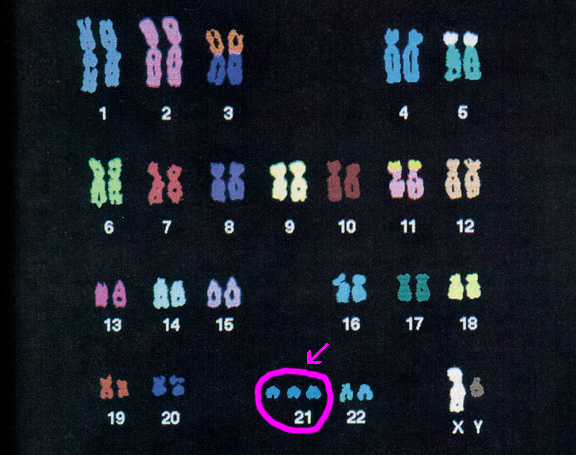

Down's syndrome is also called trisomy 21 or T21. Edwards' syndrome is also called trisomy 18 or T18, and Patau's syndrome is also called trisomy 13 or T13.

If a screening test shows that you have a higher chance of having a baby with Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome, you'll be offered further tests to find out for certain if your baby has the condition.

What are Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome?

Down's syndrome

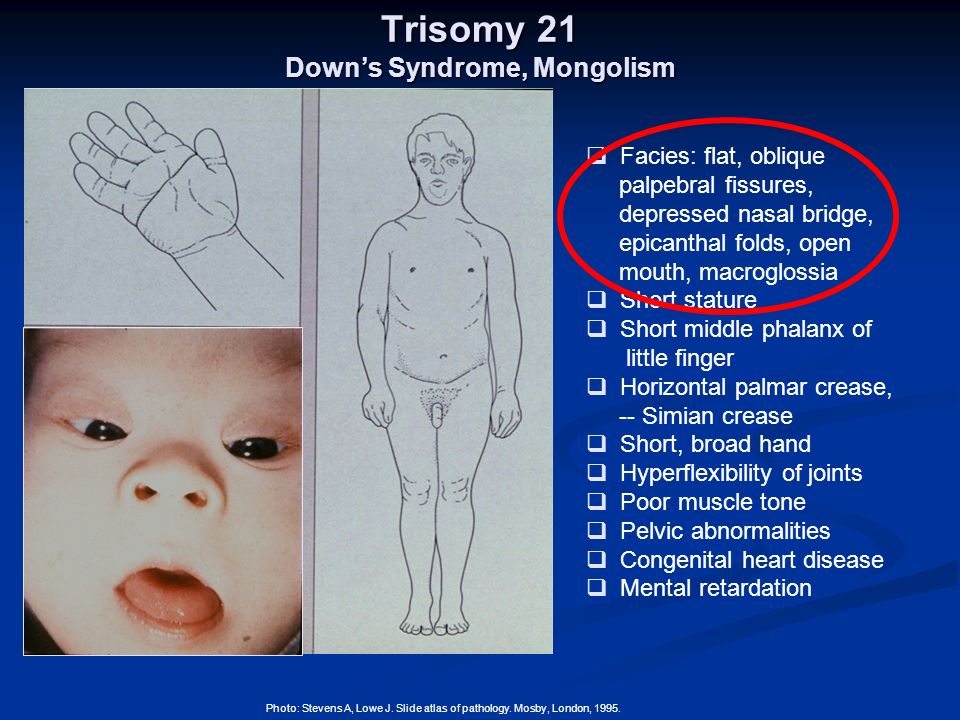

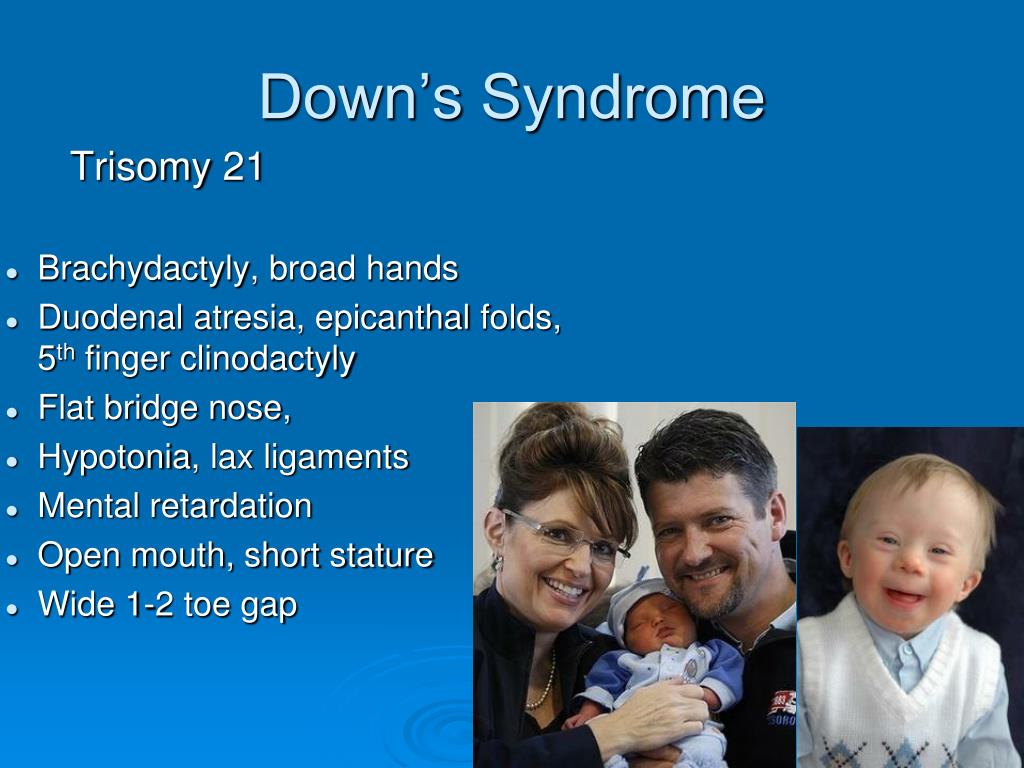

Down's syndrome causes some level of learning disability.

People with Down's syndrome may be more likely to have other health conditions, such as heart conditions, and problems with the digestive system, hearing and vision. Sometimes these can be serious, but many can be treated.

Read more about Down's syndrome

Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome

Sadly, most babies with Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome will die before or shortly after birth. Some babies may survive to adulthood, but this is rare.

All babies born with Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome will have a wide range of problems, which can be very serious. These may include major complications affecting their brain.

Read more about Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome.

What does screening for Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome involve?

Combined test

A screening test for Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome is available between weeks 10 and 14 of pregnancy. It's called the combined test because it combines an ultrasound scan with a blood test. The blood test can be carried out at the same time as the 12-week scan.

It's called the combined test because it combines an ultrasound scan with a blood test. The blood test can be carried out at the same time as the 12-week scan.

If you choose to have the test, you will have a blood sample taken. At the scan, the fluid at the back of the baby's neck is measured to determine the "nuchal translucency". Your age and the information from these 2 tests are used to work out the chance of the baby having Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome.

Obtaining a nuchal translucency measurement depends on the position of the baby and is not always possible. If this is the case, you will be offered a different blood screening test, called the quadruple test, when you're 14 to 20 weeks pregnant.

Quadruple blood screening test

If it was not possible to obtain a nuchal translucency measurement, or you're more than 14 weeks into your pregnancy, you'll be offered a test called the quadruple blood screening test between 14 and 20 weeks of pregnancy. This only screens for Down's syndrome and is not as accurate as the combined test.

This only screens for Down's syndrome and is not as accurate as the combined test.

20-week screening scan

For Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome, if you are too far into your pregnancy to have the combined test, you'll be offered a 20-week screening scan. This looks for physical conditions, including Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome.

Can this screening test harm me or my baby?

The screening test cannot harm you or the baby, but it's important to consider carefully whether to have this test.

It cannot tell you for certain whether the baby does or does not have Down's syndrome, Edward's syndrome or Patau's syndrome, but it can provide information that may lead to further important decisions. For example, you may be offered diagnostic tests that can tell you for certain whether the baby has these conditions, but these tests have a risk of miscarriage.

Do I need to have screening for Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome?

You do not need to have this screening test – it's your choice. Some people want to find out the chance of their baby having these conditions while others do not.

You can choose to have screening for:

- all 3 conditions

- Down's syndrome only

- Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome only

- none of the conditions

What if I decide not to have this test?

If you choose not to have the screening test for Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome, you can still choose to have other tests, such as a 12-week scan.

If you choose not to have the screening test for these conditions, it's important to understand that if you have a scan at any point during your pregnancy, it could pick up physical conditions.

The person scanning you will always tell you if any conditions are found.

Getting your results

The screening test will not tell you whether your baby does or does not have Down's, Edwards' or Patau's syndromes – it will tell you if you have a higher or lower chance of having a baby with one of these conditions.

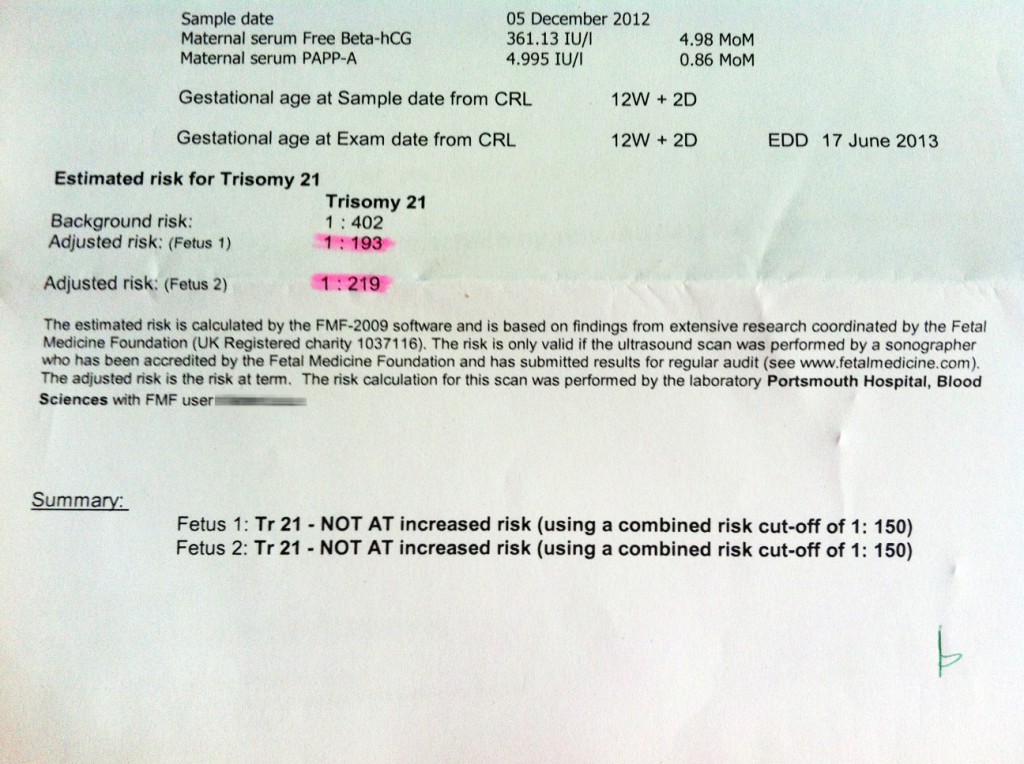

If you have screening for all 3 conditions, you will receive 2 results: 1 for your chance of having a baby with Down's syndrome, and 1 for your joint chance of having a baby with Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome.

If your screening test returns a lower-chance result, you should be told within 2 weeks. If it shows a higher chance, you should be told within 3 working days of the result being available.

This may take a little longer if your test is sent to another hospital. It may be worth asking the midwife what happens in your area and when you can expect to get your results.

You will be offered an appointment to discuss the test results and the options you have.

The charity Antenatal Results and Choices (ARC) offers lots of information about screening results and your options if you get a higher-chance result.

Possible results

Lower-chance result

If the screening test shows that the chance of having a baby with Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome is lower than 1 in 150, this is a lower-chance result. More than 95 out of 100 screening test results will be lower chance.

A lower-chance result does not mean there's no chance at all of the baby having Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome.

Higher-chance result

If the screening test shows that the chance of the baby having Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome is higher than 1 in 150 – that is, anywhere between 1 in 2 and 1 in 150 – this is called a higher-chance result.

Fewer than 1 in 20 results will be higher chance. This means that out of 100 pregnancies screened for Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome, fewer than 5 will have a higher-chance result.

A higher-chance result does not mean the baby definitely has Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome.

Will I need further tests?

If you have a lower-chance result, you will not be offered a further test.

If you have a higher-chance result, you can decide to:

- not have any further testing

- have a second screening test called non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) – this is a blood test, which can give you a more accurate screening result and help you to decide whether to have a diagnostic test or not

- have a diagnostic test, such as amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (CVS) straight away – this will tell you for certain whether or not your baby has Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome, but in rare cases can cause a miscarriage

You can decide to have NIPT for:

- all 3 conditions

- Down's syndrome only

- Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome only

You can also decide to have a diagnostic test after NIPT.

NIPT is completely safe and will not harm your baby.

Discuss with your healthcare professional which tests are right for you.

Whatever results you get from any of the screening or diagnostic tests, you will get care and support to help you to decide what to do next.

If you find out your unborn baby has Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome

If you find out your baby has Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome a specialist doctor (obstetrician) or midwife will talk to you about your options .

You can read more about what happens if antenatal screening tests find something.

You may decide to continue with the pregnancy and prepare for your child with the condition.

Or you may decide that you do not want to continue with the pregnancy and have a termination.

If you are faced with this choice, you will get support from health professionals to help you make your decision.

For more information see GOV.UK: Screening tests for you and your baby

The charity Antenatal Results and Choices (ARC) runs a helpline from Monday to Friday, 10am to 5.30pm on 020 7713 7486.

The Down's Syndrome Association also has useful information on screening.

The charity SOFT UK offers information and support through diagnosis, bereavement, pregnancy decisions and caring for all UK families affected by Edwards' syndrome (T18) or Patau's syndrome (T13).

First trimester screening - Mayo Clinic

Overview

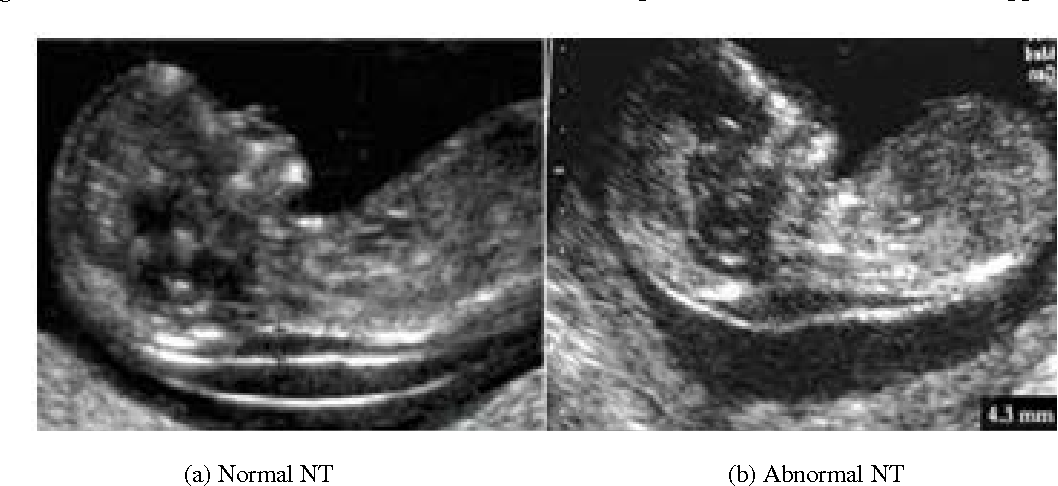

Nuchal translucency measurement

Nuchal translucency measurement

First trimester screening includes an ultrasound exam to measure the size of the clear space in the tissue at the back of a baby's neck (nuchal translucency). In Down syndrome, the nuchal translucency measurement is abnormally large — as shown on the left in the ultrasound image of an 11-week fetus. For comparison, the ultrasound image on the right shows an 11-week fetus with a normal nuchal translucency measurement.

In Down syndrome, the nuchal translucency measurement is abnormally large — as shown on the left in the ultrasound image of an 11-week fetus. For comparison, the ultrasound image on the right shows an 11-week fetus with a normal nuchal translucency measurement.

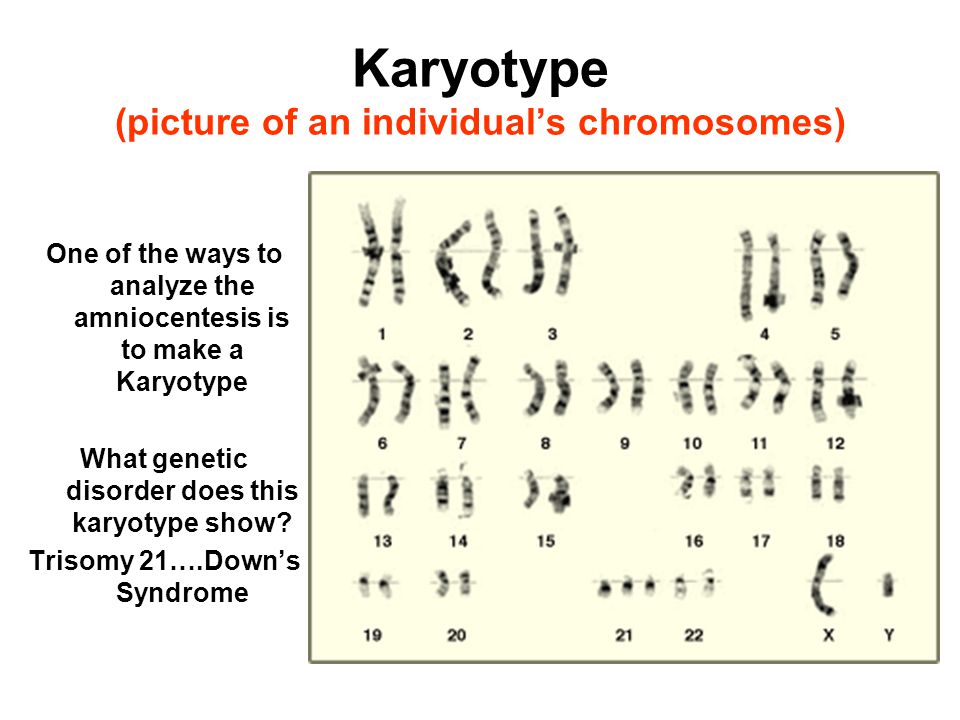

First trimester screening is a prenatal test that offers early information about a baby's risk of certain chromosomal conditions, specifically, Down syndrome (trisomy 21) and extra sequences of chromosome 18 (trisomy 18).

First trimester screening, also called the first trimester combined test, has two steps:

- A blood test to measure levels of two pregnancy-specific substances in the mother's blood — pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A (PAPP-A) and human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG)

- An ultrasound exam to measure the size of the clear space in the tissue at the back of the baby's neck (nuchal translucency)

Typically, first trimester screening is done between weeks 11 and 14 of pregnancy.

Using your age and the results of the blood test and the ultrasound, your health care provider can gauge your risk of carrying a baby with Down syndrome or trisomy 18.

If results show that your risk level is moderate or high, you might choose to follow first trimester screening with another test that's more definitive.

Products & Services

- Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

- Book: Obstetricks

Why it's done

First trimester screening is done to evaluate your risk of carrying a baby with Down syndrome. The test also provides information about the risk of trisomy 18.

Down syndrome causes lifelong impairments in mental and social development, as well as various physical concerns. Trisomy 18 causes more severe delays and is often fatal by age 1.

First trimester screening doesn't evaluate the risk of neural tube defects, such as spina bifida.

Because first trimester screening can be done earlier than most other prenatal screening tests, you'll have the results early in your pregnancy. This will give you more time to make decisions about further diagnostic tests, the course of the pregnancy, medical treatment and management during and after delivery. If your baby has a higher risk of Down syndrome, you'll also have more time to prepare for the possibility of caring for a child who has special needs.

This will give you more time to make decisions about further diagnostic tests, the course of the pregnancy, medical treatment and management during and after delivery. If your baby has a higher risk of Down syndrome, you'll also have more time to prepare for the possibility of caring for a child who has special needs.

Other screening tests can be done later in pregnancy. An example is the quad screen, a blood test that's typically done between weeks 15 and 20 of pregnancy. The quad screen can evaluate your risk of carrying a baby with Down syndrome or trisomy 18, as well as neural tube defects, such as spina bifida. Some health care providers choose to combine the results of first trimester screening with the quad screen. This is called integrated screening. This can improve the detection rate of Down syndrome.

First trimester screening is optional. Test results indicate only whether you have an increased risk of carrying a baby with Down syndrome or trisomy 18, not whether your baby actually has one of these conditions.

Before the screening, think about what the results will mean to you. Consider whether the screening will be worth any anxiety it might cause, or whether you'll manage your pregnancy differently depending on the results. You might also consider what level of risk would be enough for you to choose a more invasive follow-up test.

More Information

- Prenatal testing: Quick guide to common tests

Request an Appointment at Mayo Clinic

Risks

First trimester screening is a routine prenatal screening test. The screening poses no risk of miscarriage or other pregnancy complications.

How you prepare

You don't need to do anything special to prepare for first trimester screening. You can eat and drink normally before both the blood test and the ultrasound exam.

What you can expect

First trimester screening includes a blood draw and an ultrasound exam.

During the blood test, a member of your health care team takes a sample of blood by inserting a needle into a vein in your arm. The blood sample is sent to a lab for analysis. You can return to your usual activities immediately.

The blood sample is sent to a lab for analysis. You can return to your usual activities immediately.

For the ultrasound exam, you'll lie on your back on an exam table. Your health care provider or an ultrasound technician will place a transducer — a small plastic device that sends and receives sound waves — over your abdomen. The reflected sound waves will be digitally converted into images on a monitor. Your health care provider or the technician will use these images to measure the size of the clear space in the tissue at the back of your baby's neck.

The ultrasound doesn't hurt, and you can return to your usual activities immediately.

Results

Your health care provider will use your age and the results of the blood test and ultrasound exam to gauge your risk of carrying a baby with Down syndrome or trisomy 18. Other factors — such as a prior Down syndrome pregnancy — also might affect your risk.

First trimester screening results are given as positive or negative and also as a probability, such as a 1 in 250 risk of carrying a baby with Down syndrome.

First trimester screening correctly identifies about 85 percent of women who are carrying a baby with Down syndrome. About 5 percent of women have a false-positive result, meaning that the test result is positive but the baby doesn't actually have Down syndrome.

When you consider your test results, remember that first trimester screening indicates only your overall risk of carrying a baby with Down syndrome or trisomy 18. A low-risk result doesn't guarantee that your baby won't have one of these conditions. Likewise, a high-risk result doesn't guarantee that your baby will be born with one of these conditions.

If you have a positive test result, your health care provider and a genetics professional will discuss your options, including additional testing. For example:

- Prenatal cell-free DNA (cfDNA) screening. This is a sophisticated blood test that examines fetal DNA in the maternal bloodstream to determine whether your baby is at risk of Down syndrome, extra sequences of chromosome 13 (trisomy 13) or extra sequences of chromosome 18 (trisomy 18).

Some forms of cfDNA screening also screen for other chromosome problems and provide information about fetal sex. A normal result might eliminate the need for a more invasive prenatal diagnostic test.

Some forms of cfDNA screening also screen for other chromosome problems and provide information about fetal sex. A normal result might eliminate the need for a more invasive prenatal diagnostic test. - Chorionic villus sampling (CVS). CVS can be used to diagnose chromosomal conditions, such as Down syndrome. During CVS, which is usually done during the first trimester, a sample of tissue from the placenta is removed for testing. CVS poses a small risk of miscarriage.

- Amniocentesis. Amniocentesis can be used to diagnose both chromosomal conditions, such as Down syndrome, and neural tube defects, such as spina bifida. During amniocentesis, which is usually done during the second trimester, a sample of amniotic fluid is removed from the uterus for testing. Like CVS, amniocentesis poses a small risk of miscarriage.

Your health care provider or a genetic counselor will help you understand your test results and what the results mean for your pregnancy.

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Related

Products & Services

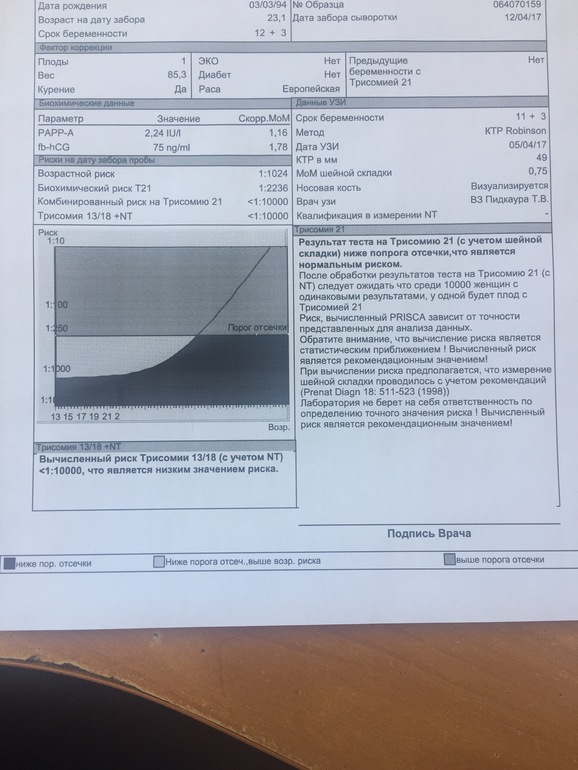

Prenatal screening for trisomies of the first trimester of pregnancy (Down syndrome), PRISCA

A non-invasive test that, based on certain laboratory markers and clinical data, allows using a computer program to calculate the likely risk of developing chromosomal diseases or other congenital anomalies of the fetus.

Due to limitations in the use of calculation methods for determining the risk of congenital fetal anomalies, it is not possible to calculate such risks in multiple pregnancies with 3 or more fetuses.

Russian synonyms

Biochemical screening of the 1st trimester of pregnancy, "double test" of the 1st trimester.

Synonyms English

Maternal Screen, First Trimester; Prenatal Screening I; PRISCA I (Prenatal Risk Calculation).

Research method

Solid-phase chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay ("sandwich" method), immunochemiluminescent analysis.

Units

MIU/mL (milli-international unit per milliliter), IU/l (international unit per liter).

What biomaterial can be used for research?

Venous blood.

How to properly prepare for an examination?

- Eliminate fatty foods 24 hours before the test.

- Avoid physical and emotional stress for 30 minutes prior to examination.

- Do not smoke for 30 minutes before the test.

General information about the study

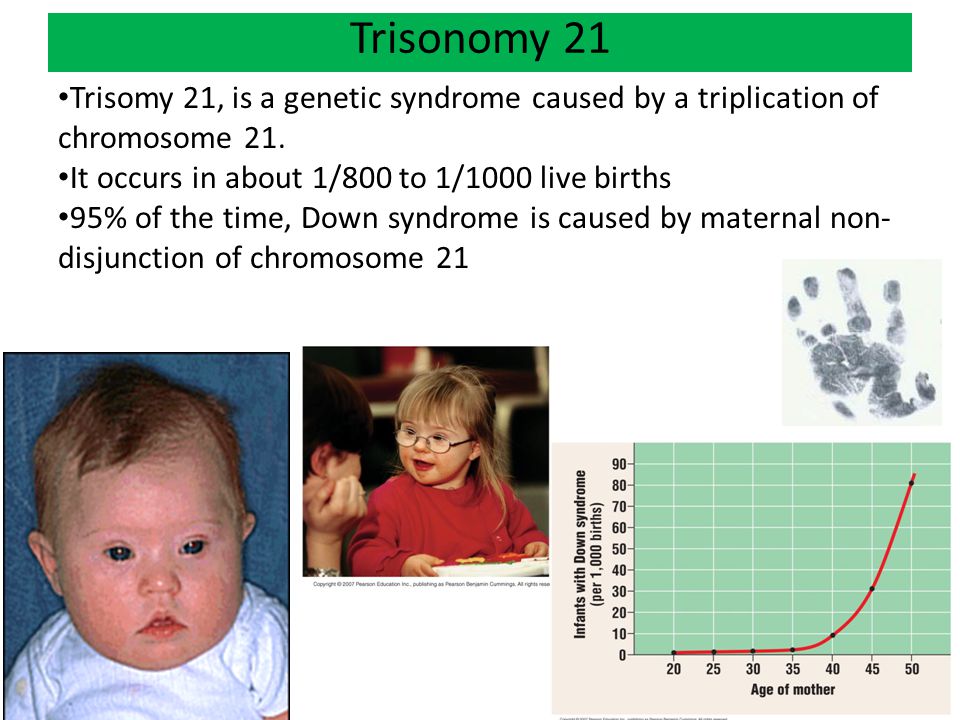

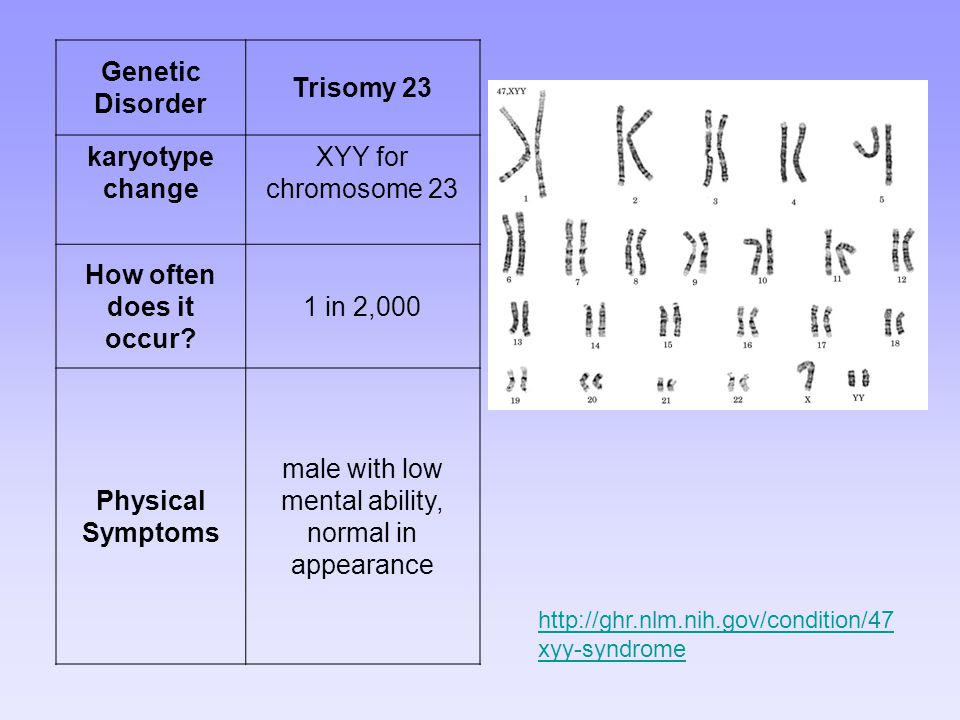

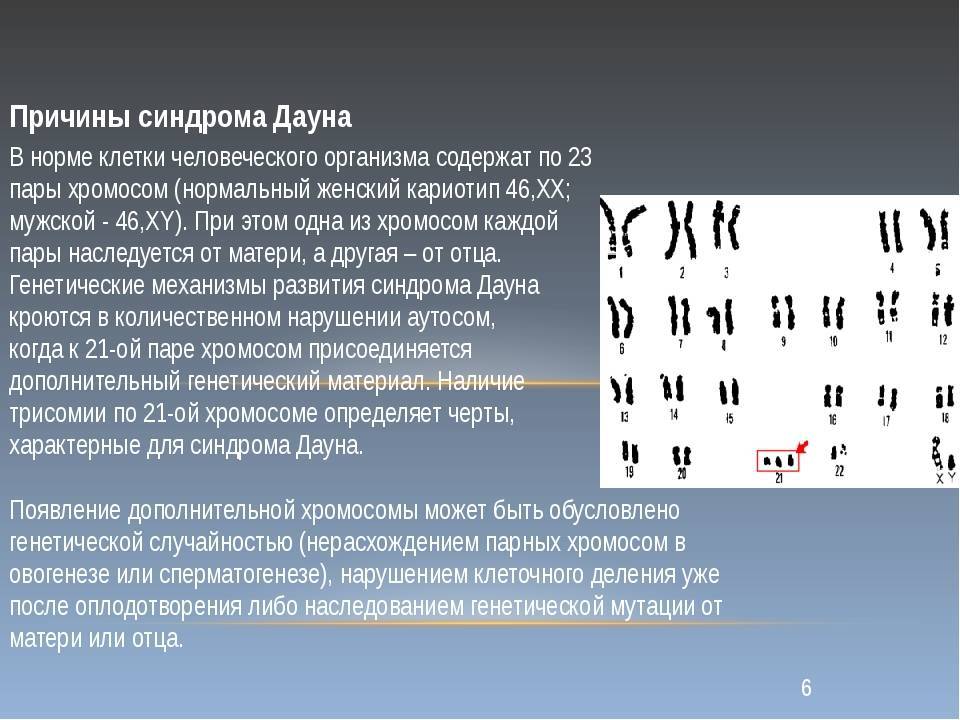

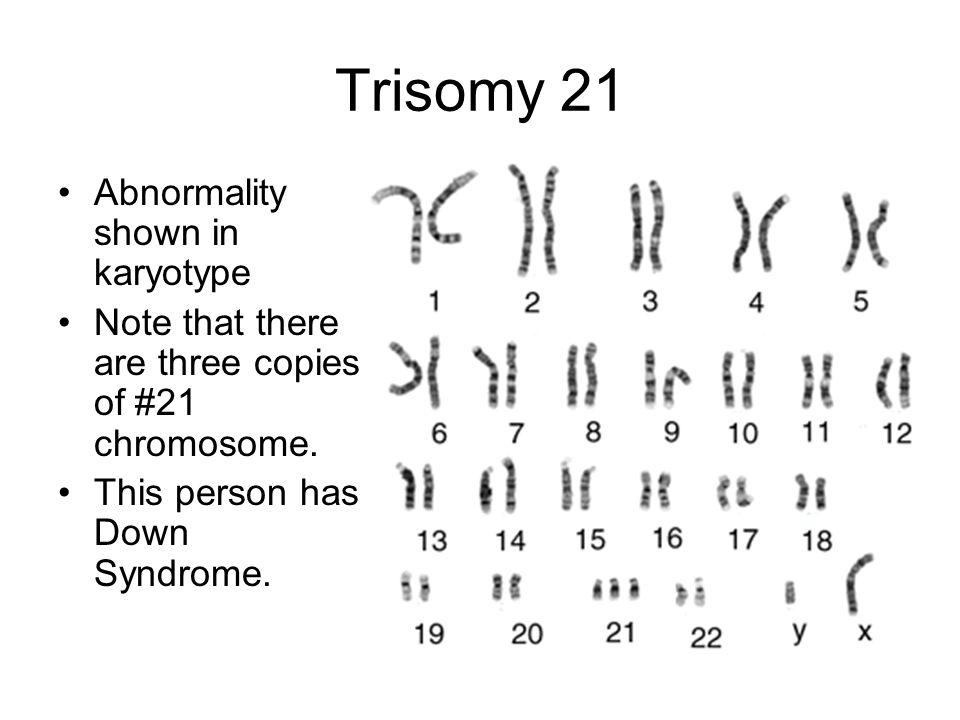

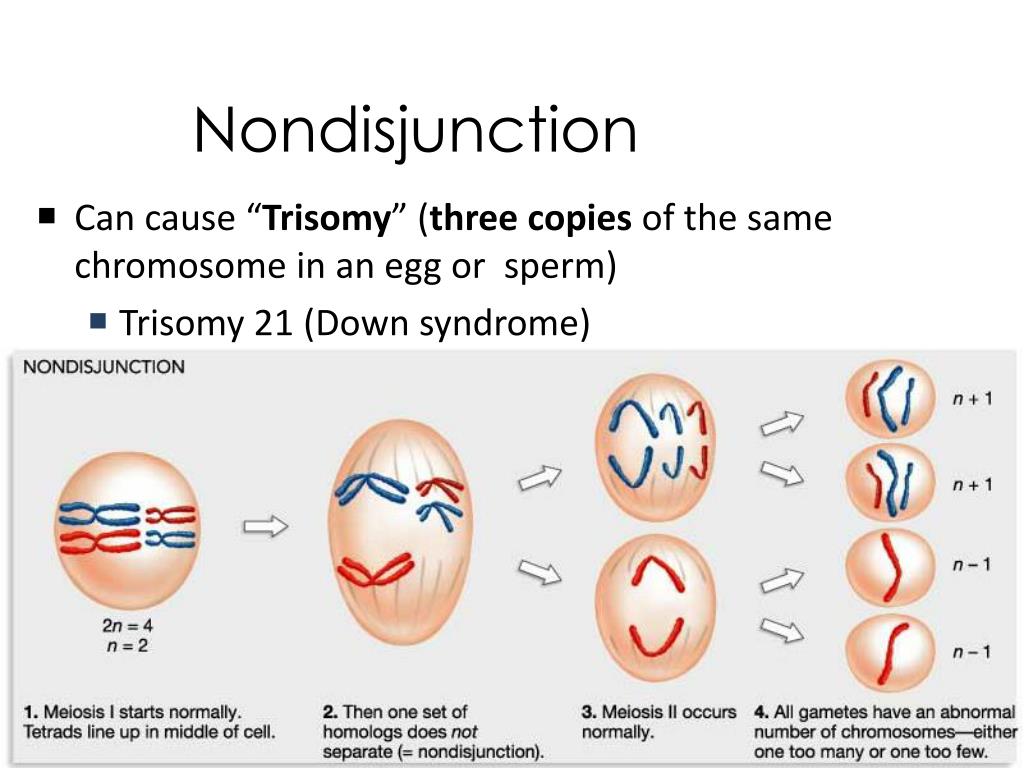

Down's disease is a chromosomal disease associated with a violation of cell division (meiosis) during the maturation of sperm and eggs, which leads to the formation of an additional 21st chromosome. The frequency in the population is 1 case per 600-800 births. The risk of a chromosomal abnormality increases with the age of the woman in labor and does not depend on the state of health of the mother of the child, environmental factors. Edwards syndrome (trisomy 18) and Patau syndrome (trisomy 13) are less related to maternal age, with a population frequency of 1 in 7,000 births. Accurate prenatal diagnosis of genetic diseases requires invasive procedures that are associated with a high likelihood of complications, therefore, safe research methods are used for mass screening to identify low or high risk of chromosomal abnormalities and assess the feasibility of further testing.

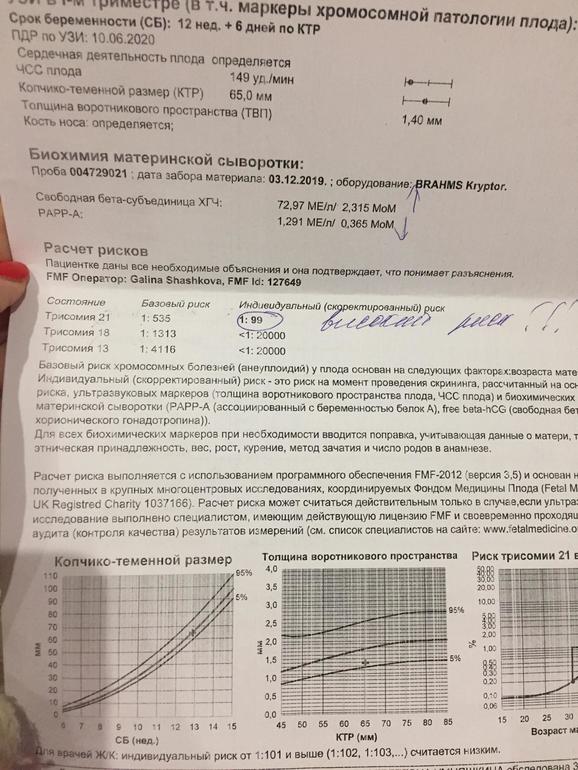

Prenatal screening for first trimester trisomies is performed to determine the likely risk of fetal chromosomal abnormalities, trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), and trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome) and trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome) between weeks 10 and 13 th week and 6 days of pregnancy. It is calculated using the PRISCA (Prenatal Risk Calculation) computer program developed by Typolog Software (Germany) and having an international certificate of conformity. For the study, the content of the free beta subunit of chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) in the blood of a pregnant woman is determined.

For the study, the content of the free beta subunit of chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) in the blood of a pregnant woman is determined.

Enzyme PAPP-A ensures proper growth and development of the placenta. Its content in the blood increases with the course of pregnancy. The level of PAPP-A does not significantly depend on such parameters as the sex and weight of the child. In the presence of a chromosomal abnormality with fetal malformations, its concentration in the blood decreases significantly from the 8th to the 14th week of pregnancy. It decreases most sharply with trisomy on the 21st, 18th and 13th chromosomes. In Down syndrome, the PAPP-A level is an order of magnitude lower than in a normal pregnancy. An even sharper decrease in the concentration of PAPP-A in the mother's blood serum is observed if the fetus has a genetic pathology with multiple malformations - Cornelia de Lange syndrome. However, after 14 weeks of gestation, the value of determining PAPP-A as a risk marker for chromosomal abnormalities is lost, since its level then corresponds to the norm even in the presence of pathology.

For screening, clinical data (age of the pregnant woman, body weight, number of fetuses, presence and characteristics of IVF, mother's race, bad habits, presence of diabetes mellitus, medications taken), ultrasound data (coccyx-parietal size (CTE) and thickness collar space (NTP), the length of the nasal bone). If ultrasound data is available, the gestational age is calculated by the CTE value, and not by the date of the last menstruation.

After the study and calculation of the risk, a scheduled consultation with an obstetrician-gynecologist is carried out.

The results of a screening study cannot serve as criteria for making a diagnosis and as a reason for artificial termination of pregnancy. Based on them, a decision is made on the advisability of prescribing invasive methods for examining the fetus. At high risk, additional examinations are necessary, including chorion puncture, amniocentesis with a genetic study of the material obtained.

What is research used for?

- For screening of pregnant women to assess the risk of fetal chromosomal pathology - trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), Edwards syndrome.

When is the test ordered?

- When examining pregnant women in the first trimester (the analysis is recommended at a gestation period of 10 weeks - 13 weeks 6 days), especially in the presence of risk factors for the development of pathology:

- over 35 years of age;

- history of miscarriage and severe pregnancy complications;

- chromosomal pathologies, Down's disease or congenital malformations in previous pregnancies;

- hereditary diseases in the family;

- past infections, radiation exposure, taking in early pregnancy or shortly before it drugs that have a teratogenic effect.

What do the results mean?

Reference values

- Pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A)

| Week of pregnancy | Reference values |

| 8th-9th | 0. |

| 9th-10th | 0.32 - 2.42 MIU/ml |

| 10-11th | 0.46 - 3.73 MIU/ml |

| 11-12th | 0.79 - 4.76 MIU/ml |

| 12-13th | 1.03 - 6.01 MIU/ml |

| 13th-14th | 1.47 - 8.54 MIU/ml |

- Free beta human chorionic gonadotropin (free beta hCG)

| Week of pregnancy | Reference values |

| 8th-9th | 23. |

| 9th-10th | 23.58 - 193.13 ng/mL |

| 11-12th | 17.4 - 130.38 ng/mL |

| 12-13th | 13.43 - 128.5 ng/mL |

| 13th-14th | 14.21 - 114.7 ng/mL |

| 14-15th | 8.91 - 79.44 ng/mL |

15-16th | 5.78 - 62.07 ng/mL |

| 16-17th | 4.67 - 50.05 ng/mL |

| 17th-18th | 3. |

| 18-19th | 3.84 - 33.3 ng/mL |

PRISCA calculates the likelihood of malformations based on the results of a pregnancy examination. For example, the ratio 1:400 shows that, according to statistics, one out of 400 pregnant women with similar values of indicators has a child with a corresponding malformation.

What can influence the result?

- The result is affected by the accuracy of the information provided and the conclusions of the ultrasound diagnosis.

- A false-positive result (high risk) in some cases may be associated with an increase in the beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin against the background of placental dysfunction, threatened abortion.

Important Notes

- The laboratory must have accurate data on gestational age and all factors needed to calculate rates.

Incomplete or inaccurate data provided may cause serious errors in risk calculations.

Incomplete or inaccurate data provided may cause serious errors in risk calculations.

The use of invasive diagnostic methods (chorionic biopsy, amniocentesis, cordocentesis) is not recommended if screening tests are normal and there are no changes on ultrasound. - The results of prenatal screening, even at a high calculated risk, cannot serve as a basis for artificial termination of pregnancy.

Also recommended

- Pregnancy - 1st trimester

- Beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (beta hCG)

- Plasma pregnancy-associated protein A (PAPP-A)

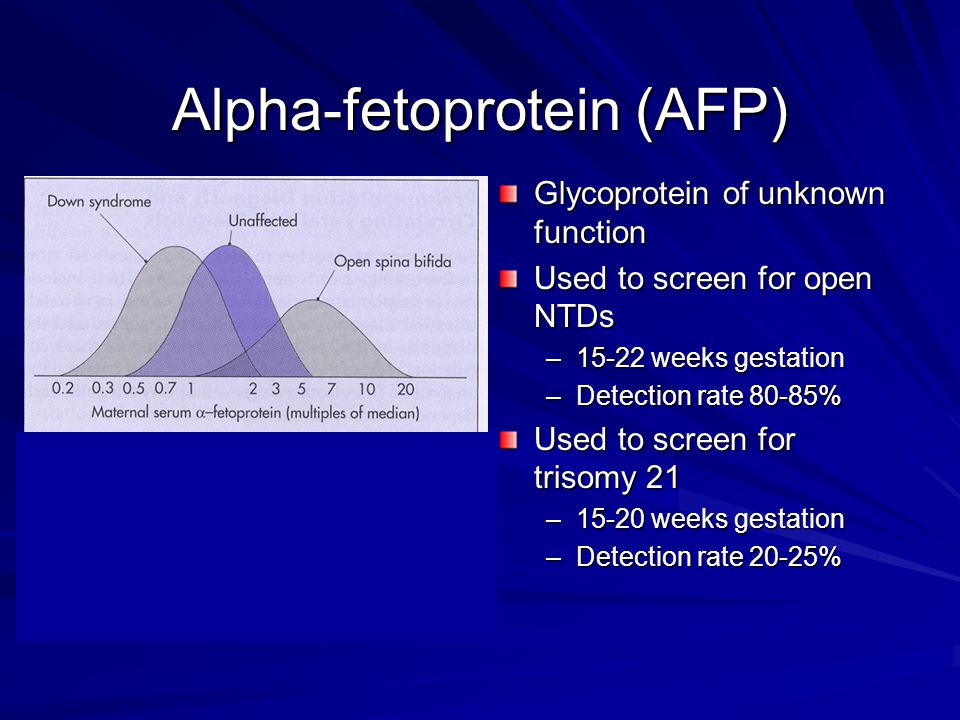

- Alpha-fetoprotein (alpha-FP)

- Free estriol

- Placental lactogen

- Progesterone

- Cytological examination of the hormonal background (with the threat of termination of pregnancy, cycle disorders)

Who orders the examination?

Obstetrician-gynecologist, medical geneticist.

Literature

- Durkovic J., Andelic L., Mandic B., Lazar D. False Positive Values of Biomarkers of Prenatal Screening on Chromosomopathy as Indicators of a Risky Pregnancy. // Journal of Medical Biochemistry. – Volume 30, Issue 2, Pages 126–130.

- Muller F., Aegerter P., et al. Software for Prenatal Down Syndrome Risk Calculation: A Comparative Study of Six Software Packages. // Clinical Chemistry - August 1999 vol. 45 no. 8 - 1278-1280.

How to decipher first trimester screening

Question: “Hello. Pregnancy 12 weeks. The first ultrasound screening: KTR - 54 mm, TVP (collar space thickness) - 1 mm. The length of the nasal bone is 2.4 mm. Venous circulation is not changed. ( This refers to the blood flow in the venous duct and the fact that there is no reverse blood flow - Guzov II.) "Blood for hCG - 3.59" . (That is, if you look at the MoM, then this is 3.5 times higher than the average median value - Guzov I. I.)

I.)

"PAPP-A 0.75 (i.e. slightly reduced). Combined risk for Down's syndrome (i.e. trisomy 21) - 1:244 . Is this very serious? What other examination is needed? Does taking medications Lutein, Metipred affect the result?

Igor Ivanovich Guzov, obstetrician-gynecologist, PhD, founder of the Center for Immunology and Reproduction, answers your questions.

I'll start from the end right away. Taking medication can sometimes affect the result. But Lutein is a drug prescribed, most likely, by an ophthalmologist. Probably, due to the fact that there are some problems with the retina, there may be some trophic changes there. And Metipred was probably prescribed by an obstetrician-gynecologist. Here you need to understand why such therapy is prescribed? It should not affect the analysis results so much directly.

Conclusion: combined screening 1 to 244. You did not write how old you are. Pregnancy 12 weeks.

I just want to show how we analyze and what we prescribe in such cases.

So, this coccygeal-parietal size (KTR) is 54 mm. When calculating risks, it is the main one for determining the gestational age with an accuracy of one day. Because ovulation can come a little earlier, a little later. But there is a fairly stable indicator, which in the period of 11-12 weeks is subject to the smallest spread of fluctuations. Because general biological processes mainly work here, and individual characteristics, differences in fetal growth begin to appear over long periods. And then the coccyx-parietal size is the main indicator for calculating risks, according to which the gestational age is calculated.

If there is a coccygeal-parietal size, then the risks are calculated in this way: the gestational age is taken (average for a given size), and based on this period, which is calculated according to the KTR, the gestational age is considered.

Can there be any errors here?

Sometimes they can, because the coccyx-parietal size is the size of the baby from the top of the head to the tailbone. Accordingly, it may depend on the degree of flexion of the spine. The child can shrink a little - and then he can shrink a little. It can bend a little - and then it will be a little more.

But in general, it is a fairly reliable indicator by which the gestational age is calculated. When calculating the risks, and this is already a program, the gestational age is considered according to the coccygeal-parietal size. Further, already in relation to this gestational age, all other indicators are calculated.

These figures are 3.59; 0.75 are values expressed in MoM. This is an English abbreviation for multiple of median, which translates as "a multiple of the median".

What do you mean?

Let's say we calculated the gestational age. Let's say it was 11 weeks 3 days, or 11 weeks 4 days, or 12 weeks at the time of the analysis. We get this by the coccyx-parietal size. Within the program, there are figures calculated for each laboratory that characterize the average median value of the indicator for this particular day, calculated by the coccygeal-parietal size.

We get this by the coccyx-parietal size. Within the program, there are figures calculated for each laboratory that characterize the average median value of the indicator for this particular day, calculated by the coccygeal-parietal size.

Next, we compare the biochemical figure that was obtained for the average figure for a given day of pregnancy, and make an adjustment for a number of indicators. This is, first of all, the weight of a pregnant woman. Race has a certain meaning. The presence of certain factors matters, for example, whether the pregnancy occurred as a result of IVF. There are correction factors depending on whether there is diabetes mellitus and so on.

There are a number of indicators that the operator enters into the system, places in the appropriate "windows" of the program. As a result, we get MoM. For the program, the thickness values of the collar space are also calculated in MoM. Usually this is not indicated: there is a thickness of the collar space of 1 mm - this thickness of the collar space is translated into MoM, and then MoM goes for mathematical calculation by the program.

The length of the nasal bone is 2.4 mm. This can also be translated into MoMs, but some programs simply take into account "yes" or "not", "+" or "-", whether the nasal bone is or not. It may not be here.

When we analyze all these things, we begin to analyze what the ultrasound shows. Ultrasound examination in your case is good.

The thickness of the collar spaces and is also sometimes called the “neck crease”. The collar space is the area of the back of the neck at a given time in a prenatal baby. It shouldn't be too thick. If there is a thickening of this collar space, then this indicates that the area of \u200b\u200bthe back surface of the child's neck may be edematous. This may increase the risks that are calculated by screening associated with Down syndrome. In your case, this is a good value.

Nasal bone in many cases where there is a risk of an increased risk of Down syndrome, it may be either reduced or absent. In this case, the nasal bone is present.

In this case, the nasal bone is present.

Venous blood flow . You write: "Venous circulation is not changed." This refers to the venous duct. This is such a vessel that exists in the intrauterine fetus, which (if a little primitive) drives blood from the placenta, from the umbilical cord towards the fetal heart.

This blood flow must be in one direction, that is, from the umbilical cord towards the fetal heart. Because the child, through this venous duct, actually receives arterial blood, which is further distributed throughout the body. The fetal heart at this stage is very, very small, so if there is a reverse flow, then this reverse flow means that the blood has come to the heart and gone back. This may indicate that there are problems with the emerging valvular apparatus of the heart of the fetus. That is, there is an increased risk of anomalies in the structure of the cardiovascular system, in particular violations of the valvular apparatus.

The child is still very, very small, its size is only 54 mm, it is a small “boy the size of a finger”. We cannot see if he has some kind of valvular disorder or not, but the presence of reversed blood flow, indicating that the blood came to the heart and went back - may indicate the presence of disorders in the formation of the valvular apparatus of the heart in the fetus.

We cannot see if he has some kind of valvular disorder or not, but the presence of reversed blood flow, indicating that the blood came to the heart and went back - may indicate the presence of disorders in the formation of the valvular apparatus of the heart in the fetus.

Why does reversed blood flow and nuchal thickening affect the risk of Down syndrome?

This is due to the fact that this trisomy of the 21st pair (Down's syndrome) is often accompanied by a number of anomalies in the child's body, and in a very large percentage of cases there are violations of the formation of the heart and cardiovascular system in the child, that is heart defects can be. And just heart defects can disrupt the blood flow in the body of the fetus, and this will be accompanied by an expansion of the thickness of the collar space and the presence of reverse blood flow.

In the future, always, if we see a reverse flow, we control after 15 weeks of pregnancy on a good ultrasound machine the valvular apparatus. Then we can clearly see whether there are any defects or not. This is what we look at in first trimester screening.

Then we can clearly see whether there are any defects or not. This is what we look at in first trimester screening.

This assessment of the general anatomy of the fetus shows that your baby is well formed, and there are no ultrasound signs that something is going wrong.

What is missing in ultrasound? And what, according to modern standards, should be included in the ultrasound examination of the first trimester ?

It is imperative to check the blood flow of the uterine arteries, because in this screening we look not only for disorders associated with chromosomal abnormalities. We also look at the risks associated with impaired placental function. Therefore, the determination of blood flow in the uterine arteries, which is absolutely safe for the fetus, is currently, I believe, an indispensable component in ultrasound screening of the first trimester of pregnancy.

If there is a violation, a decrease in uterine blood flow inside the arteries at this time, we can identify increased risks associated with a number of complications in the second half of pregnancy, even longer. These are intrauterine growth retardation, the risk of preeclampsia, the risk of antenatal fetal death, the risk of prematurity for long periods.

These are intrauterine growth retardation, the risk of preeclampsia, the risk of antenatal fetal death, the risk of prematurity for long periods.

A whole range of these risks can be calculated if we include an additional indicator inside this screening. That is, ultrasound screening includes determining the blood flow of the uterine arteries. This is a very significant moment. We talked about this, but now we are talking about what we need to do in connection with this analysis.

When we evaluate the biochemical risk, we get hCG 3.59. That is, in this case, hCG is 3.6 times higher than the median.

PAPP-A is slightly reduced, 0.75, i.e. 75% of the conditional median.

If we take the direction of all these indicators: an increase in the level of hCG, a slight decrease in the level of PAPP-A, then we have scissors that can be characteristic in their pattern for an increased risk of trisomy 21 pair. But since the risk of trisomy for the 21st pair is a purely algebraic or arithmetic study, that is, several MoMs are laid down: TVP, the presence of a nasal bone, MoM for hCG and MoM for PAPP-A. Accordingly, all this is evaluated together, and we get the total risk - 1 to 244, as if they are telling you that everything is fine, and nothing needs to be done.

Accordingly, all this is evaluated together, and we get the total risk - 1 to 244, as if they are telling you that everything is fine, and nothing needs to be done.

It probably is. Because the program thinks so. She thinks stupidly, but this program takes into account the fact that there is a completely normal unaltered structure of the fetus, but it is theoretically possible to assume that there may be a problem associated with some kind of chromosomal anomaly, but there are no heart defects.

And then this ultrasound of normal TP, normal nasal bone, and normal blood circulation can lower the alarm threshold when we get these numbers.

Often the antenatal clinic doctor just looks at the report and says that you are fine, or that you have something. Of course, with such a ratio of indicators, I would simply recommend somehow removing this “worm of doubt” about any problems.

In such a situation, firstly, I would recommend a consultation with a geneticist, and we wrote to you about it. Also, I would still recommend taking, if possible, blood for NIPT. This is exactly the case when NIPT (non-invasive prenatal screening) helps to remove the last “worms of doubt”: what if there is something, some problems regarding chromosomal abnormalities.

Also, I would still recommend taking, if possible, blood for NIPT. This is exactly the case when NIPT (non-invasive prenatal screening) helps to remove the last “worms of doubt”: what if there is something, some problems regarding chromosomal abnormalities.

With this ratio of indicators, in my opinion, the probability of any chromosomal abnormalities, in particular trisomy 21, has a fairly low risk. But this risk is greater than the average for the population. Your individual risk is 1 in 244, and the population risk could be 1 in 500, 1 in 600. That is, if this individual risk is greater than the population average risk, if you approach this analytically and see what is best to do, I in this case, I would recommend donating blood for NIPT, and if there are no problems with it for the 21st pair, then the issue can be closed. Most likely, everything is fine.

In any case, with such a ratio of indicators, I would recommend an ultrasound examination also at 16 weeks of pregnancy. Just in case, in order to make sure that everything is correctly formed there.

Just in case, in order to make sure that everything is correctly formed there.

Let's assume that everything will be fine (I'm almost sure that everything will be fine there according to these chromosomal parameters), what else can be associated with a higher than the average for the population figure of hCG?

Why can the level of hCG be 3.5 times higher?

Very often the cause is absolutely physiological. Perhaps this is due to the fact that the genes that provide placentation, inherited from the father by the child, work this way. We said in one of our previous conversations that sometimes higher hCG numbers are just a characteristic of some men. Since hCG and the numbers associated with placentation are largely controlled by the genes inherited by the child from his dad. Very often there are higher numbers associated with the fact that the child received such a gene, and is not associated with any chromosomal abnormalities or any other problems.

Our task, the task of the obstetrician-gynecologist, is not to miss the problem. If there are any indicators that can characterize an increase in the risk of problems, it is better to check it. We say that this can be a completely normal option. But what if it could be unrelated to the father's genetics? What other options?

There may also be a situation when there were 2 fertilized eggs. That fertilized egg stopped developing because there was some kind of problem, the second fertilized egg continues to develop. The "vanished twin" may continue to give its increased hCG figure for some time, and this may give an increase to this MoMa. Is it possible.

It must be remembered that hCG is a human chorionic hormone. During pregnancy, it has its own specific dynamics. It turns out that in the early stages of pregnancy, it begins to be produced literally from the first days of pregnancy. But it begins to enter the mother's blood after implantation after about 7-9 days of pregnancy. At least after 10 days of pregnancy, we already see small positive values. When implantation occurred, there was contact between the mother's body and the child's body, the fetus completely immersed in the uterine mucosa and sent a signal to the mother's body - hCG.

At least after 10 days of pregnancy, we already see small positive values. When implantation occurred, there was contact between the mother's body and the child's body, the fetus completely immersed in the uterine mucosa and sent a signal to the mother's body - hCG.

This hormone stops menstruation, causes the corpus luteum (that is, the structure inside the ovary formed after ovulation) to produce progesterone. The first week of pregnancy develops due to the fact that the hormone progesterone, which is very important for it, produced by the corpus luteum inside the ovary, continues to produce progesterone, ensuring the preparation of the uterine mucosa, ensuring the normal development of the fetus in early pregnancy.

Therefore, as the primary fetal villi develop, when the implantation process is underway, we see a sharp and quite high increase in hCG levels occurring in the first 8-10 weeks of pregnancy. Around this time, it reaches very high values, while ensuring the development of pregnancy.

At the same time, the need for hCG disappears in the baby, because as the placenta forms, the placenta itself begins to produce progesterone.

If we take the concentration of progesterone, then approximately 7-8 weeks of pregnancy is the period when the corpus luteum begins to "lose its ground" and produces less progesterone, and the placenta itself produces more and more progesterone. After 11-12 weeks of pregnancy, the production of the corpus luteum does not matter. The placenta produces so much progesterone that there are situations when, for example, some kind of tumor is found on the ovaries and they are removed, and the pregnancy continues to develop normally.

During IVF, when a donor egg is used, when there are no own eggs, that is, the work of the ovary in a woman is completely turned off due to menopause or early menopause, or due to the removal of the ovaries, progesterone support goes up to about 12-13, maybe, 14 weeks. And then this support is not needed, because the child himself, by producing progesterone, fully meets his needs.

And that's why you don't need HCG during these times when you're screening. He starts to fall. If you keep it at higher numbers, then in some cases this is a sign, an “alarm signal”, that something is missing. This is how HCG works.

When we usually evaluate the numbers of such an indicator, we say that it is good that there is a lot of progesterone. And when there is a lot of hCG, this is often “not healthy”, because the child can give an alarm signal to the mother’s body by giving higher numbers of hCG to the mother’s body.

I believe that in order for us to be completely sure that everything is going well, it is better to additionally look at the blood flow in the uterine arteries. And look all the same indicator called placental growth factor (PLGF). And then this screening will be complete and complete. And we will not miss the situation, which is typical for an increase in the risk of problems at long stages of pregnancy, we will have time to prescribe the prevention of placental dysfunction. Usually in such cases, low-dose aspirin is prescribed.

Usually in such cases, low-dose aspirin is prescribed.

This is the standard international practice that I have described. Therefore, I would go this route. And in order to still not guess when the risk of trisomy for the 21st pair is higher than the average risk for the population. Since we now have such a powerful, significant and much more informative study in this regard as NIPT, I would recommend turning it in just in case. So that you don’t have to constantly think about what happened in the first trimester.

I would recommend doing these things: look at the blood flow in the uterine arteries, get a placental growth factor test, get an NIPT test. Just in order to completely protect you from the risk of all problems, and at the same time predict placental function, do not miss any things.

These are 0.75 MoM according to PAPP-A. PAPP-A is a completely placental indicator that largely characterizes how well the placentation went. It is slightly reduced, but not critically reduced.

17 - 1.54 MIU/ml

17 - 1.54 MIU/ml  65 - 162.5 ng/ml

65 - 162.5 ng/ml  33 - 42.81 ng/mL

33 - 42.81 ng/mL