Thyroiditis during pregnancy

Thyroid Disease & Pregnancy - NIDDK

On this page:

- What role do thyroid hormones play in pregnancy?

- Hyperthyroidism in Pregnancy

- Hypothyroidism in Pregnancy

- Postpartum Thyroiditis

- Is it safe to breastfeed while I’m taking beta-blockers, thyroid hormone, or antithyroid medicines?

- Thyroid Disease and Eating During Pregnancy

- Clinical Trials

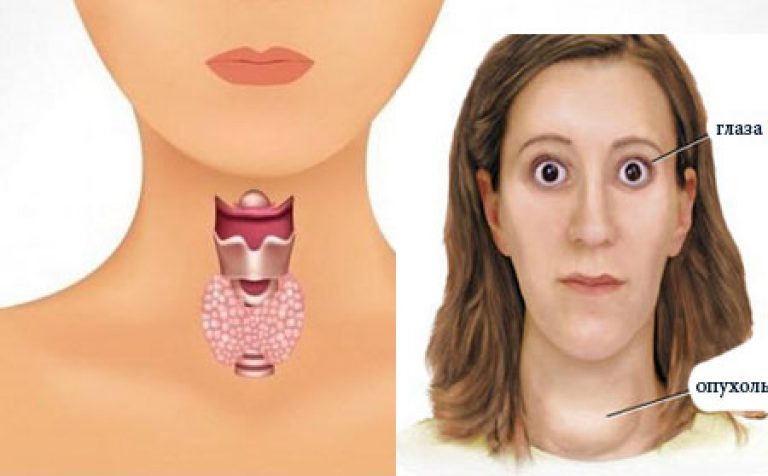

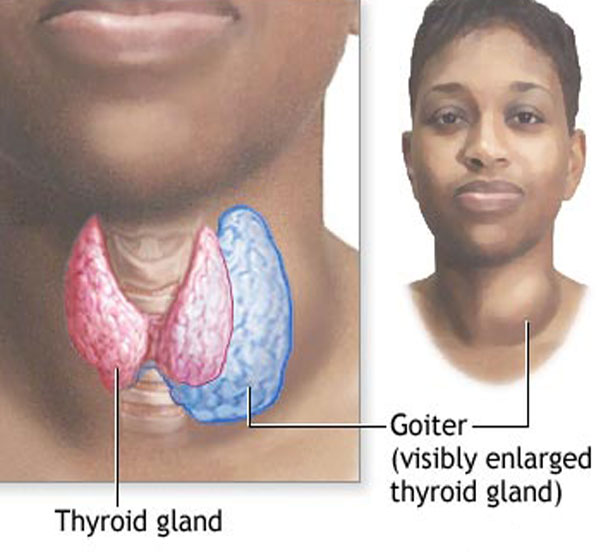

Thyroid disease is a group of disorders that affects the thyroid gland. The thyroid is a small, butterfly-shaped gland in the front of your neck that makes thyroid hormones. Thyroid hormones control how your body uses energy, so they affect the way nearly every organ in your body works—even the way your heart beats.

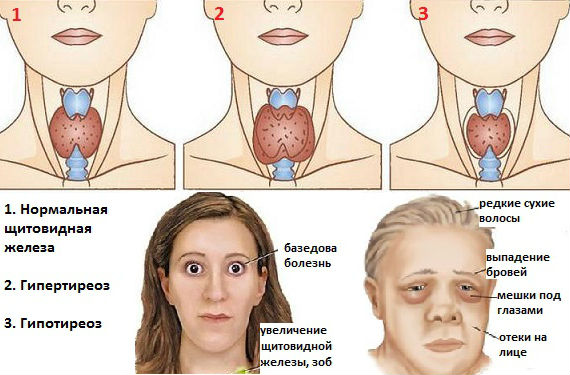

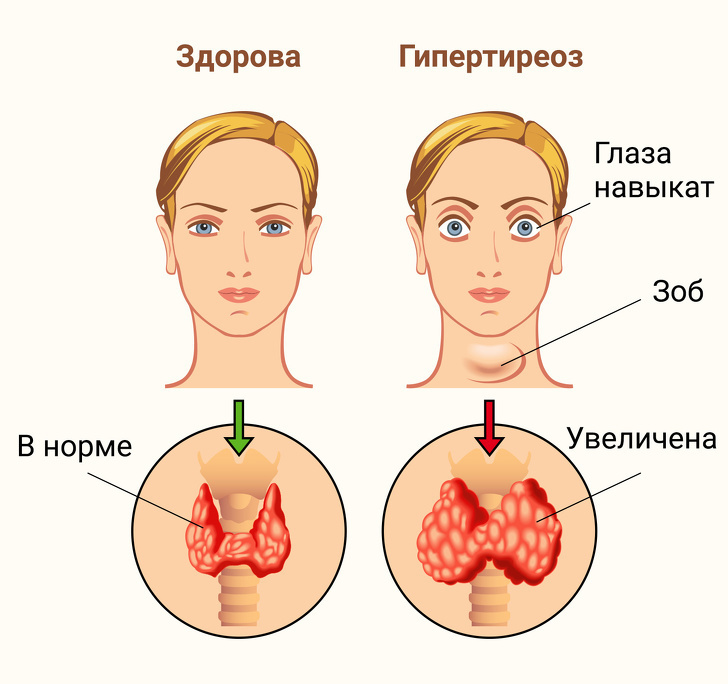

The thyroid is a small gland in your neck that makes thyroid hormones.Sometimes the thyroid makes too much or too little of these hormones. Too much thyroid hormone is called hyperthyroidism and can cause many of your body’s functions to speed up. “Hyper” means the thyroid is overactive. Learn more about hyperthyroidism in pregnancy. Too little thyroid hormone is called hypothyroidism and can cause many of your body’s functions to slow down. “Hypo” means the thyroid is underactive. Learn more about hypothyroidism in pregnancy.

If you have thyroid problems, you can still have a healthy pregnancy and protect your baby’s health by having regular thyroid function tests and taking any medicines that your doctor prescribes.

What role do thyroid hormones play in pregnancy?

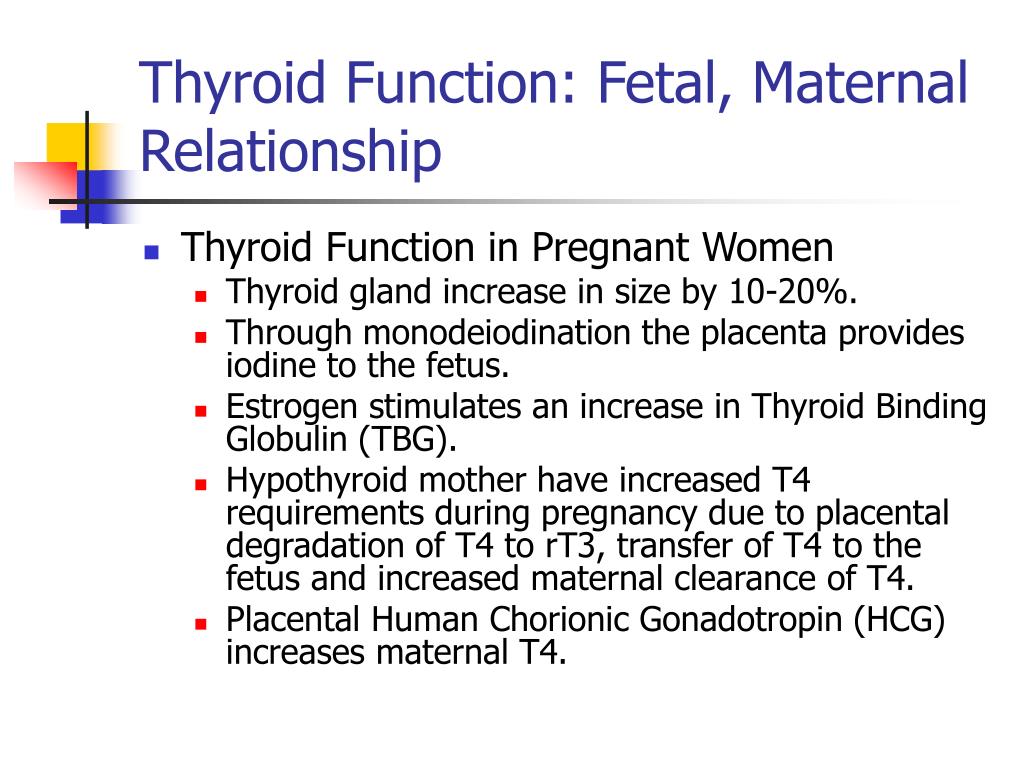

Thyroid hormones are crucial for normal development of your baby’s brain and nervous system. During the first trimester—the first 3 months of pregnancy—your baby depends on your supply of thyroid hormone, which comes through the placenta. At around 12 weeks, your baby’s thyroid starts to work on its own, but it doesn’t make enough thyroid hormone until 18 to 20 weeks of pregnancy.

Two pregnancy-related hormones—human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and estrogen—cause higher measured thyroid hormone levels in your blood. The thyroid enlarges slightly in healthy women during pregnancy, but usually not enough for a health care professional to feel during a physical exam.

The thyroid enlarges slightly in healthy women during pregnancy, but usually not enough for a health care professional to feel during a physical exam.

Thyroid problems can be hard to diagnose in pregnancy due to higher levels of thyroid hormones and other symptoms that occur in both pregnancy and thyroid disorders. Some symptoms of hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism are easier to spot and may prompt your doctor to test you for these thyroid diseases.

Another type of thyroid disease, postpartum thyroiditis, can occur after your baby is born.

Hyperthyroidism in Pregnancy

What are the symptoms of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy?

Some signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism often occur in normal pregnancies, including faster heart rate, trouble dealing with heat, and tiredness.

Other signs and symptoms can suggest hyperthyroidism:

- fast and irregular heartbeat

- shaky hands

- unexplained weight loss or failure to have normal pregnancy weight gain

What causes hyperthyroidism in pregnancy?

Hyperthyroidism in pregnancy is usually caused by Graves’ disease and occurs in 1 to 4 of every 1,000 pregnancies in the United States. 1 Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder. With this disease, your immune system makes antibodies that cause the thyroid to make too much thyroid hormone. This antibody is called thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin, or TSI.

1 Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder. With this disease, your immune system makes antibodies that cause the thyroid to make too much thyroid hormone. This antibody is called thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin, or TSI.

Graves’ disease may first appear during pregnancy. However, if you already have Graves’ disease, your symptoms could improve in your second and third trimesters. Some parts of your immune system are less active later in pregnancy so your immune system makes less TSI. This may be why symptoms improve. Graves’ disease often gets worse again in the first few months after your baby is born, when TSI levels go up again. If you have Graves’ disease, your doctor will most likely test your thyroid function monthly throughout your pregnancy and may need to treat your hyperthyroidism.1 Thyroid hormone levels that are too high can harm your health and your baby’s.

If you have Graves’ disease, your doctor will most likely test your thyroid function monthly during your pregnancy.

Rarely, hyperthyroidism in pregnancy is linked to hyperemesis gravidarum—severe nausea and vomiting that can lead to weight loss and dehydration. Experts believe this severe nausea and vomiting is caused by high levels of hCG early in pregnancy. High hCG levels can cause the thyroid to make too much thyroid hormone. This type of hyperthyroidism usually goes away during the second half of pregnancy.

Less often, one or more nodules, or lumps in your thyroid, make too much thyroid hormone.

How can hyperthyroidism affect me and my baby?

Untreated hyperthyroidism during pregnancy can lead to

- miscarriage

- premature birth

- low birthweight

- preeclampsia—a dangerous rise in blood pressure in late pregnancy

- thyroid storm—a sudden, severe worsening of symptoms

- congestive heart failure

Rarely, Graves’ disease may also affect a baby’s thyroid, causing it to make too much thyroid hormone. Even if your hyperthyroidism was cured by radioactive iodine treatment to destroy thyroid cells or surgery to remove your thyroid, your body still makes the TSI antibody. When levels of this antibody are high, TSI may travel to your baby’s bloodstream. Just as TSI caused your own thyroid to make too much thyroid hormone, it can also cause your baby’s thyroid to make too much.

When levels of this antibody are high, TSI may travel to your baby’s bloodstream. Just as TSI caused your own thyroid to make too much thyroid hormone, it can also cause your baby’s thyroid to make too much.

Tell your doctor if you’ve had surgery or radioactive iodine treatment for Graves’ disease so he or she can check your TSI levels. If they are very high, your doctor will monitor your baby for thyroid-related problems later in your pregnancy.

Tell your doctor if you’ve had surgery or radioactive iodine treatment for Graves’ disease.An overactive thyroid in a newborn can lead to

- a fast heart rate, which can lead to heart failure

- early closing of the soft spot in the baby’s skull

- poor weight gain

- irritability

Sometimes an enlarged thyroid can press against your baby’s windpipe and make it hard for your baby to breathe. If you have Graves’ disease, your health care team should closely monitor you and your newborn.

How do doctors diagnose hyperthyroidism in pregnancy?

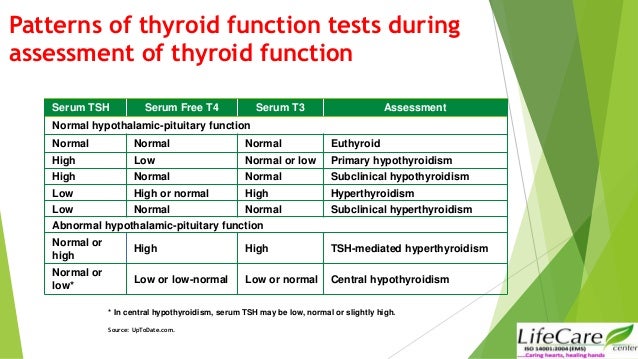

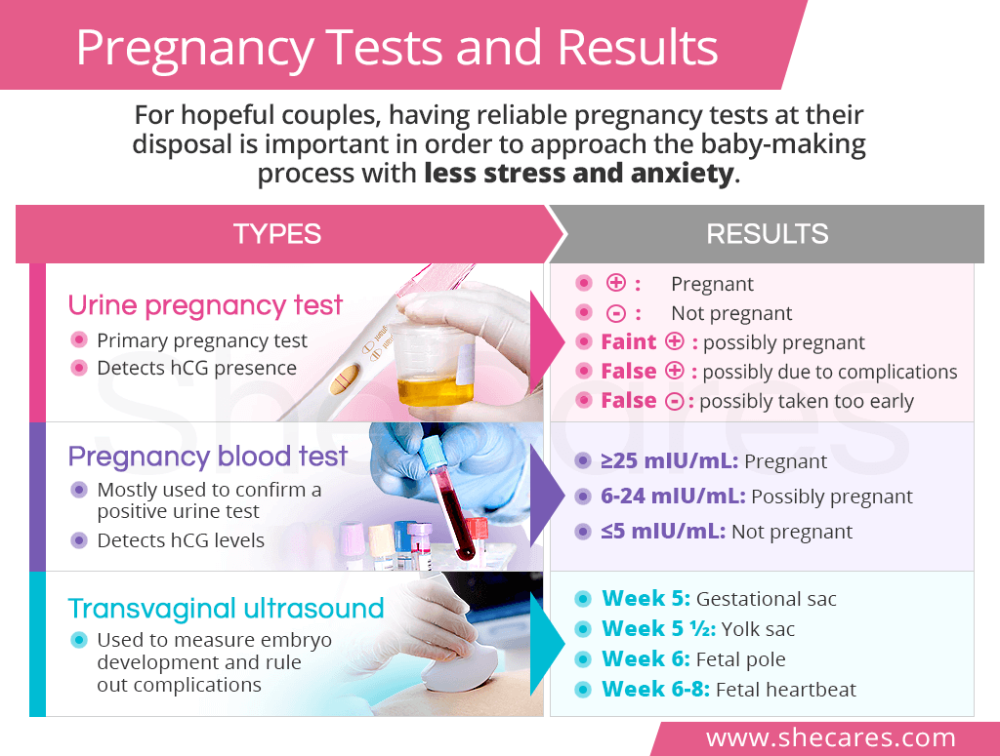

Your doctor will review your symptoms and do some blood tests to measure your thyroid hormone levels. Your doctor may also look for antibodies in your blood to see if Graves’ disease is causing your hyperthyroidism. Learn more about thyroid tests and what the results mean.

How do doctors treat hyperthyroidism during pregnancy?

If you have mild hyperthyroidism during pregnancy, you probably won’t need treatment. If your hyperthyroidism is linked to hyperemesis gravidarum, you only need treatment for vomiting and dehydration.

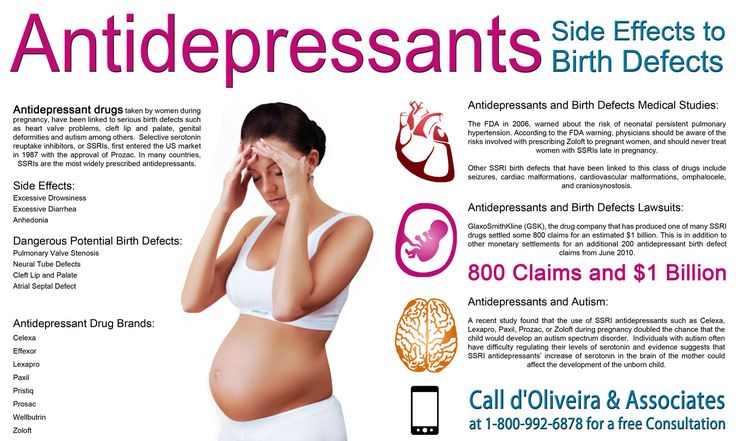

If your hyperthyroidism is more severe, your doctor may prescribe antithyroid medicines, which cause your thyroid to make less thyroid hormone. This treatment prevents too much of your thyroid hormone from getting into your baby’s bloodstream. You may want to see a specialist, such as an endocrinologist or expert in maternal-fetal medicine, who can carefully monitor your baby to make sure you’re getting the right dose.

Doctors most often treat pregnant women with the antithyroid medicine propylthiouracil (PTU) during the first 3 months of pregnancy. Another type of antithyroid medicine, methimazole, is easier to take and has fewer side effects, but is slightly more likely to cause serious birth defects than PTU. Birth defects with either type of medicine are rare. Sometimes doctors switch to methimazole after the first trimester of pregnancy. Some women no longer need antithyroid medicine in the third trimester.

Small amounts of antithyroid medicine move into the baby’s bloodstream and lower the amount of thyroid hormone the baby makes. If you take antithyroid medicine, your doctor will prescribe the lowest possible dose to avoid hypothyroidism in your baby but enough to treat the high thyroid hormone levels that can also affect your baby.

Antithyroid medicines can cause side effects in some people, including

- allergic reactions such as rashes and itching

- rarely, a decrease in the number of white blood cells in the body, which can make it harder for your body to fight infection

- liver failure, in rare cases

Stop your antithyroid medicine and call your doctor right away if you develop any of these symptoms while taking antithyroid medicines:

- yellowing of your skin or the whites of your eyes, called jaundice

- dull pain in your abdomen

- constant sore throat

- fever

If you don’t hear back from your doctor the same day, you should go to the nearest emergency room.

You should also contact your doctor if any of these symptoms develop for the first time while you’re taking antithyroid medicines:

- increased tiredness or weakness

- loss of appetite

- skin rash or itching

- easy bruising

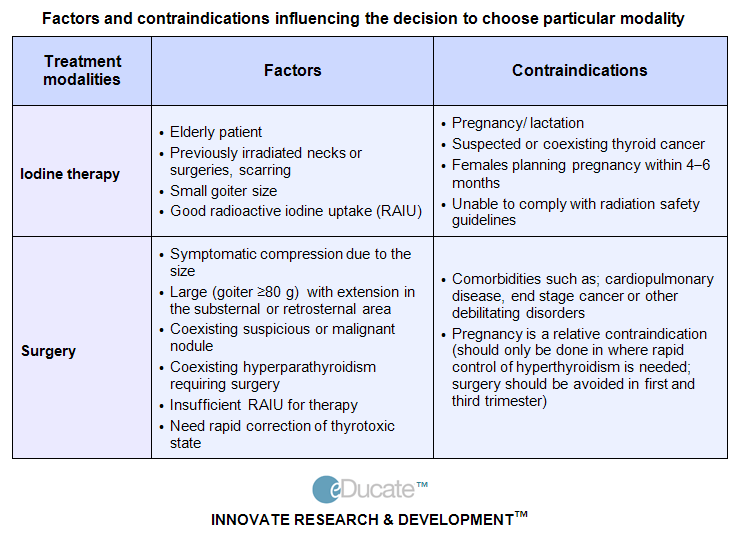

If you are allergic to or have severe side effects from antithyroid medicines, your doctor may consider surgery to remove part or most of your thyroid gland. The best time for thyroid surgery during pregnancy is in the second trimester.

Radioactive iodine treatment is not an option for pregnant women because it can damage the baby’s thyroid gland.

Hypothyroidism in Pregnancy

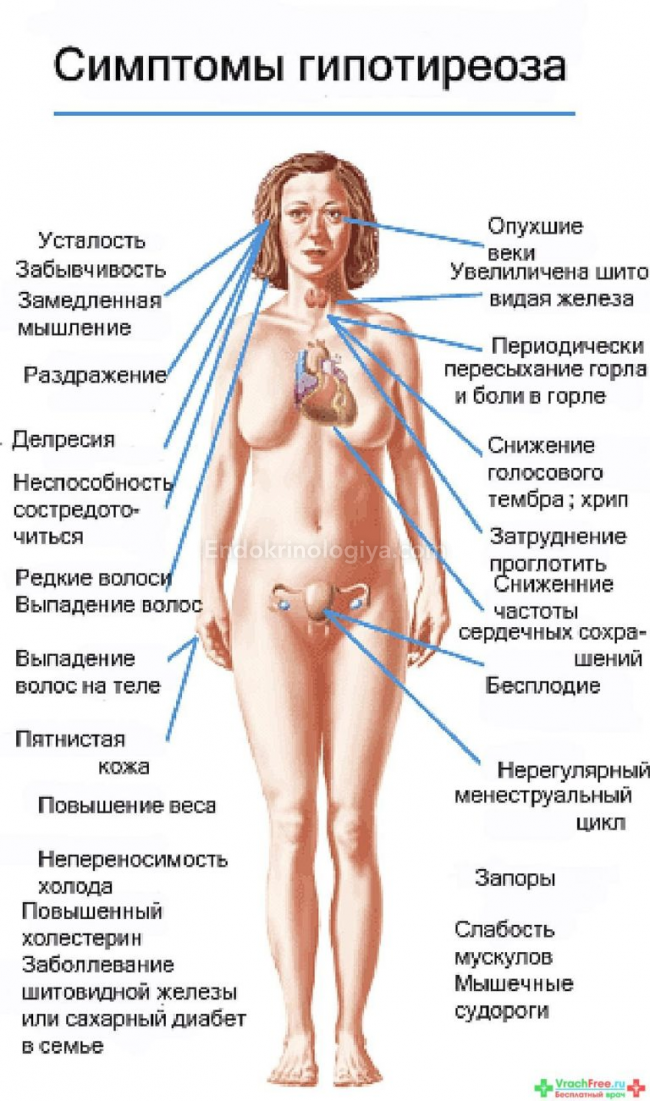

What are the symptoms of hypothyroidism in pregnancy?

Symptoms of an underactive thyroid are often the same for pregnant women as for other people with hypothyroidism. Symptoms include

- extreme tiredness

- trouble dealing with cold

- muscle cramps

- severe constipation

- problems with memory or concentration

Most cases of hypothyroidism in pregnancy are mild and may not have symptoms.

What causes hypothyroidism in pregnancy?

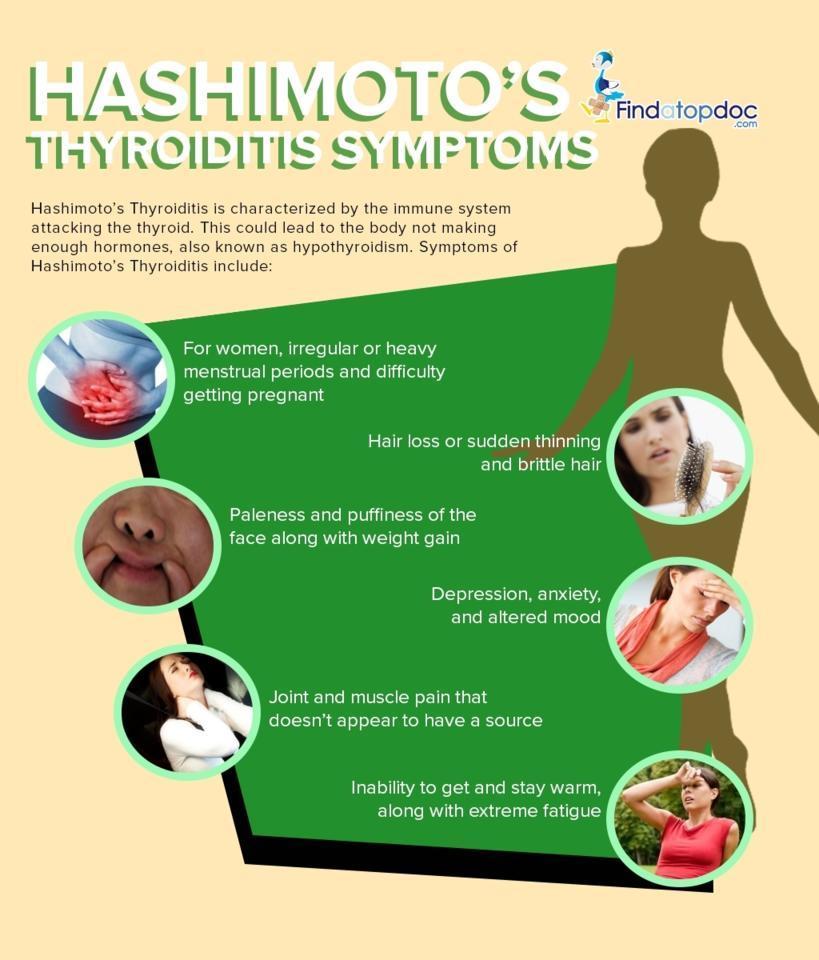

Hypothyroidism in pregnancy is usually caused by Hashimoto’s disease and occurs in 2 to 3 out of every 100 pregnancies.1 Hashimoto’s disease is an autoimmune disorder. In Hashimoto’s disease, the immune system makes antibodies that attack the thyroid, causing inflammation and damage that make it less able to make thyroid hormones.

How can hypothyroidism affect me and my baby?

Untreated hypothyroidism during pregnancy can lead to

- preeclampsia—a dangerous rise in blood pressure in late pregnancy

- anemia

- miscarriage

- low birthweight

- stillbirth

- congestive heart failure, rarely

These problems occur most often with severe hypothyroidism.

Because thyroid hormones are so important to your baby’s brain and nervous system development, untreated hypothyroidism—especially during the first trimester—can cause low IQ and problems with normal development.

How do doctors diagnose hypothyroidism in pregnancy?

Your doctor will review your symptoms and do some blood tests to measure your thyroid hormone levels. Your doctor may also look for certain antibodies in your blood to see if Hashimoto’s disease is causing your hypothyroidism. Learn more about thyroid tests and what the results mean.

How do doctors treat hypothyroidism during pregnancy?

Treatment for hypothyroidism involves replacing the hormone that your own thyroid can no longer make. Your doctor will most likely prescribe levothyroxine, a thyroid hormone medicine that is the same as T4, one of the hormones the thyroid normally makes. Levothyroxine is safe for your baby and especially important until your baby can make his or her own thyroid hormone.

Your thyroid makes a second type of hormone, T3. Early in pregnancy, T3 can’t enter your baby’s brain like T4 can. Instead, any T3 that your baby’s brain needs is made from T4. T3 is included in a lot of thyroid medicines made with animal thyroid, such as Armour Thyroid, but is not useful for your baby’s brain development. These medicines contain too much T3 and not enough T4, and should not be used during pregnancy. Experts recommend only using levothyroxine (T4) while you’re pregnant.

These medicines contain too much T3 and not enough T4, and should not be used during pregnancy. Experts recommend only using levothyroxine (T4) while you’re pregnant.

Some women with subclinical hypothyroidism—a mild form of the disease with no clear symptoms—may not need treatment.

Your doctor may prescribe levothyroxine to treat your hypothyroidism.If you had hypothyroidism before you became pregnant and are taking levothyroxine, you will probably need to increase your dose. Most thyroid specialists recommend taking two extra doses of thyroid medicine per week, starting right away. Contact your doctor as soon as you know you’re pregnant.

Your doctor will most likely test your thyroid hormone levels every 4 to 6 weeks for the first half of your pregnancy, and at least once after 30 weeks.1 You may need to adjust your dose a few times.

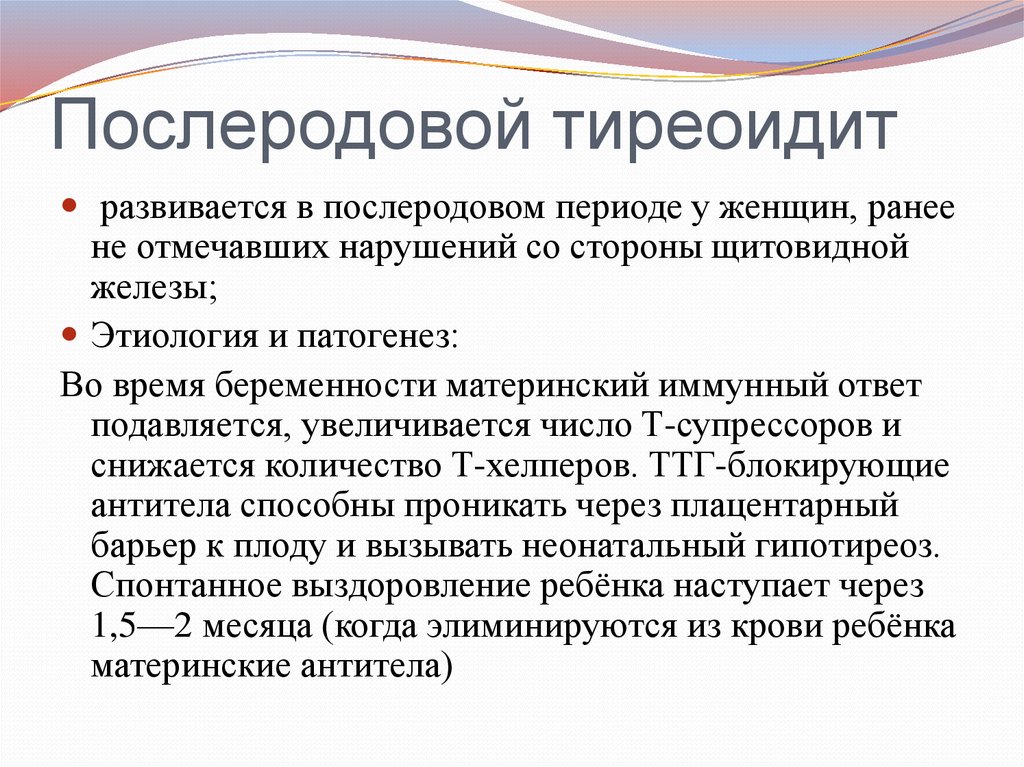

Postpartum Thyroiditis

What is postpartum thyroiditis?

Postpartum thyroiditis is an inflammation of the thyroid that affects about 1 in 20 women during the first year after giving birth1 and is more common in women with type 1 diabetes. The inflammation causes stored thyroid hormone to leak out of your thyroid gland. At first, the leakage raises the hormone levels in your blood, leading to hyperthyroidism. The hyperthyroidism may last up to 3 months. After that, some damage to your thyroid may cause it to become underactive. Your hypothyroidism may last up to a year after your baby is born. However, in some women, hypothyroidism doesn’t go away.

The inflammation causes stored thyroid hormone to leak out of your thyroid gland. At first, the leakage raises the hormone levels in your blood, leading to hyperthyroidism. The hyperthyroidism may last up to 3 months. After that, some damage to your thyroid may cause it to become underactive. Your hypothyroidism may last up to a year after your baby is born. However, in some women, hypothyroidism doesn’t go away.

Not all women who have postpartum thyroiditis go through both phases. Some only go through the hyperthyroid phase, and some only the hypothyroid phase.

What are the symptoms of postpartum thyroiditis?

The hyperthyroid phase often has no symptoms—or only mild ones. Symptoms may include irritability, trouble dealing with heat, tiredness, trouble sleeping, and fast heartbeat.

Symptoms of the hypothyroid phase may be mistaken for the “baby blues”—the tiredness and moodiness that sometimes occur after the baby is born. Symptoms of hypothyroidism may also include trouble dealing with cold; dry skin; trouble concentrating; and tingling in your hands, arms, feet, or legs. If these symptoms occur in the first few months after your baby is born or you develop postpartum depression, talk with your doctor as soon as possible.

If these symptoms occur in the first few months after your baby is born or you develop postpartum depression, talk with your doctor as soon as possible.

What causes postpartum thyroiditis?

Postpartum thyroiditis is an autoimmune condition similar to Hashimoto’s disease. If you have postpartum thyroiditis, you may have already had a mild form of autoimmune thyroiditis that flares up after you give birth.

Postpartum thyroiditis may last up to a year after your baby is born.How do doctors diagnose postpartum thyroiditis?

If you have symptoms of postpartum thyroiditis, your doctor will order blood tests to check your thyroid hormone levels.

How do doctors treat postpartum thyroiditis?

The hyperthyroid stage of postpartum thyroiditis rarely needs treatment. If your symptoms are bothering you, your doctor may prescribe a beta-blocker, a medicine that slows your heart rate. Antithyroid medicines are not useful in postpartum thyroiditis, but if you have Grave’s disease, it may worsen after your baby is born and you may need antithyroid medicines.

You’re more likely to have symptoms during the hypothyroid stage. Your doctor may prescribe thyroid hormone medicine to help with your symptoms. If your hypothyroidism doesn’t go away, you will need to take thyroid hormone medicine for the rest of your life.

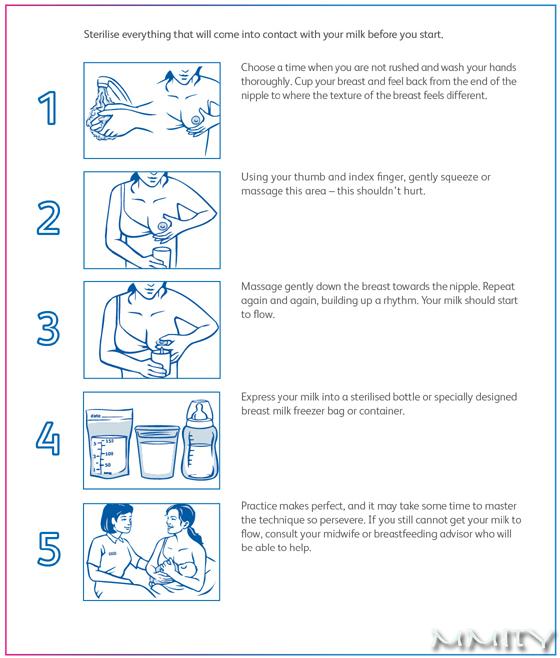

Is it safe to breastfeed while I’m taking beta-blockers, thyroid hormone, or antithyroid medicines?

Certain beta-blockers are safe to use while you’re breastfeeding because only a small amount shows up in breast milk. The lowest possible dose to relieve your symptoms is best. Only a small amount of thyroid hormone medicine reaches your baby through breast milk, so it’s safe to take while you’re breastfeeding. However, in the case of antithyroid drugs, your doctor will most likely limit your dose to no more than 20 milligrams (mg) of methimazole or, less commonly, 400 mg of PTU.

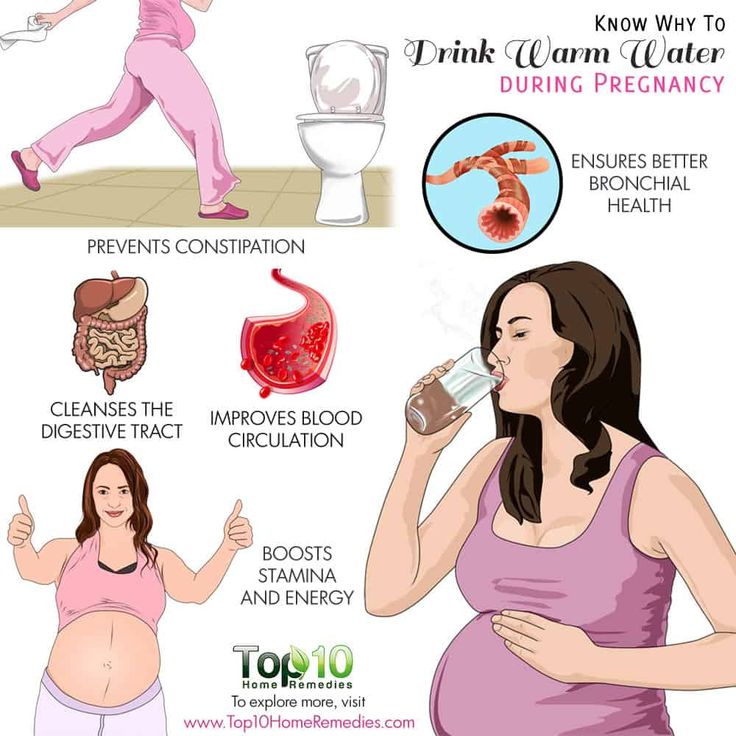

Thyroid Disease and Eating During Pregnancy

What should I eat during pregnancy to help keep my thyroid and my baby’s thyroid working well?

Because the thyroid uses iodine to make thyroid hormone, iodine is an important mineral for you while you’re pregnant. During pregnancy, your baby gets iodine from your diet. You’ll need more iodine when you’re pregnant—about 250 micrograms a day.1 Good sources of iodine are dairy foods, seafood, eggs, meat, poultry, and iodized salt—salt with added iodine. Experts recommend taking a prenatal vitamin with 150 micrograms of iodine to make sure you’re getting enough, especially if you don’t use iodized salt.1 You also need more iodine while you’re breastfeeding since your baby gets iodine from breast milk. However, too much iodine from supplements such as seaweed can cause thyroid problems. Talk with your doctor about an eating plan that’s right for you and what supplements you should take. Learn more about a healthy diet and nutrition during pregnancy.

During pregnancy, your baby gets iodine from your diet. You’ll need more iodine when you’re pregnant—about 250 micrograms a day.1 Good sources of iodine are dairy foods, seafood, eggs, meat, poultry, and iodized salt—salt with added iodine. Experts recommend taking a prenatal vitamin with 150 micrograms of iodine to make sure you’re getting enough, especially if you don’t use iodized salt.1 You also need more iodine while you’re breastfeeding since your baby gets iodine from breast milk. However, too much iodine from supplements such as seaweed can cause thyroid problems. Talk with your doctor about an eating plan that’s right for you and what supplements you should take. Learn more about a healthy diet and nutrition during pregnancy.

Clinical Trials

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and other components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conduct and support research into many diseases and conditions.

What are clinical trials, and are they right for you?

Clinical trials are part of clinical research and at the heart of all medical advances. Clinical trials look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease. Researchers also use clinical trials to look at other aspects of care, such as improving the quality of life for people with chronic illnesses. Find out if clinical trials are right for you.

What clinical trials are open?

Clinical trials that are currently open and are recruiting can be viewed at www.ClinicalTrials.gov.

References

Thyroid conditions during pregnancy | March of Dimes

The thyroid makes hormones that help your body work. If it makes too little or too much of these hormones, you may have problems during pregnancy.

Untreated thyroid conditions during pregnancy are linked to serious problems, including premature birth, miscarriage and stillbirth.

If your thyroid condition is treated during pregnancy, you can have a healthy pregnancy and a healthy baby.

Ask your health care provider if your thyroid medicine is safe to take during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Your medicine or dose may need to change.

What is the thyroid?

The thyroid is a tiny, butterfly-shaped gland in your neck. A gland is an organ that makes substances that help your body work. The thyroid makes hormones (chemicals) that play a big role in your health. For example, thyroid hormones can affect your heart rate (how fast your heart beats) and your metabolism (how well and fast your body processes what you eat and drink).

Sometimes the thyroid gland makes too much or too little of certain hormones. When this happens, you have a thyroid disorder. Some women have a thyroid disorder that begins before pregnancy (also called a pre-existing condition). Others may develop thyroid problems for the first time during pregnancy or soon after giving birth.

With treatment, a thyroid condition may not cause any problems during pregnancy. But untreated thyroid conditions can cause problems for you and your baby during pregnancy and after birth.

But untreated thyroid conditions can cause problems for you and your baby during pregnancy and after birth.

What are the main kinds of thyroid conditions?

There are two main kinds of thyroid conditions:

- Hyperthyroidism (“hyper” means too much). This is when the thyroid is overactive and makes too much thyroid hormone. This condition can cause many of your body’s functions to speed up. Hyperthyroidism during pregnancy usually is caused by an autoimmune disorder called Graves’ disease. Autoimmune disorders are health conditions that happen when antibodies (cells in the body that fight off infections) attack healthy tissue by mistake. If you have Graves’ disease, your immune system makes antibodies that cause your thyroid to make too much thyroid hormone. In rare cases, hyperthyroidism is linked to a severe form of morning sickness called hyperemesis gravidarum (excessive nausea and vomiting during pregnancy). Also in rare cases, hyperthyroidism can be caused by thyroid nodules.

These are lumps in your thyroid that make too much thyroid hormone.

These are lumps in your thyroid that make too much thyroid hormone. - Hypothyroidism (“hypo” means too little or not enough). This is when the thyroid is underactive and doesn’t make enough thyroid hormones, so many of your body’s functions slow down. Hypothyroidism during pregnancy usually is caused by an autoimmune disorder called Hashimoto’s disease. When you have Hashimoto’s disease, your immune system makes antibodies that attack your thyroid and damage it so it can’t produce thyroid hormones.

If you have a thyroid condition during pregnancy, treatment can help you have a healthy pregnancy and a healthy baby.

How are thyroid conditions during pregnancy diagnosed?

Health care providers don’t usually test your thyroid before or during pregnancy unless you’re at high risk of having a thyroid condition or you have signs or symptoms of one. If you have signs or symptoms of a thyroid condition, especially during pregnancy, tell your provider. Signs of a condition are things someone else can see or know about you, like that you have a rash or you’re coughing. Symptoms are things you feel yourself that others can’t see, like having a sore throat or feeling dizzy. Signs and symptoms of thyroid conditions may appear slowly over time. Many are signs and symptoms of other health conditions, so having one doesn’t always mean you have a thyroid problem.

Signs of a condition are things someone else can see or know about you, like that you have a rash or you’re coughing. Symptoms are things you feel yourself that others can’t see, like having a sore throat or feeling dizzy. Signs and symptoms of thyroid conditions may appear slowly over time. Many are signs and symptoms of other health conditions, so having one doesn’t always mean you have a thyroid problem.

Your provider gives you a physical exam and a blood test to check for thyroid conditions. The blood test measures the levels of thyroid hormones and thyroid stimulating hormone (also called TSH) in your body. TSH is a hormone that tells your thyroid gland to make thyroid hormones. If you think you may have a thyroid condition, ask your provider about testing.

Are you at risk for having a thyroid condition during pregnancy?

You’re at higher risk for a thyroid condition during pregnancy than other women if you:

- Are currently being treated for a thyroid condition or you have thyroid nodules or a goiter.

A goiter is a swollen thyroid gland that can make your neck look swollen.

A goiter is a swollen thyroid gland that can make your neck look swollen. - Have had a thyroid condition in the past (including after giving birth), or you’ve had a baby who had a thyroid condition

- Have an autoimmune disorder or you have a family history of autoimmune thyroid disease, like Graves’ disease or Hashimoto’s disease. Family history means that the condition runs in your family (people in your family have or have had the condition). Use the March of Dimes family health history form and share it with your provider. The form helps you keep a record of any health conditions and treatments that you, your partner and everyone in both of your families has had. It can help your provider check for health conditions that may affect your pregnancy. If you have a family history of thyroid or autoimmune conditions, ask your provider about testing.

- Have type 1 diabetes. Diabetes is a condition in which your body has too much sugar (called glucose) in the blood. Type 1 diabetes is a kind of preexisting diabetes, which means you have it before you get pregnant.

If you have type 1 diabetes, your pancreas stops making insulin. Insulin is a hormone that helps keep the right amount of glucose in your body.

If you have type 1 diabetes, your pancreas stops making insulin. Insulin is a hormone that helps keep the right amount of glucose in your body. - Have had high-dose neck radiation or treatment for hyperthyroidism. Radiation is a kind of energy. It travels as rays or particles in the air.

If you’ve had a thyroid condition or think you’re at risk for having a thyroid condition, ask your provider about testing.

What are signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism?

Hyperthyroidism that’s untreated or not treated correctly is linked to problems for women and babies during pregnancy and after birth.

Problems for women can include:

- Preeclampsia. This is a serious blood pressure condition that can happen after the 20th week of pregnancy or after giving birth (also called postpartum preeclampsia). It’s when a woman has high blood pressure and signs that some of her organs, like her kidneys and liver, may not be working normally.

Blood pressure is the force of blood that pushes against the walls of your arteries. Arteries are blood vessels that carry blood away from your heart to other parts of the body. High blood pressure (also called hypertension) is when the force of blood against the walls of the blood vessels is too high. It can stress your heart and cause problems during pregnancy.

Blood pressure is the force of blood that pushes against the walls of your arteries. Arteries are blood vessels that carry blood away from your heart to other parts of the body. High blood pressure (also called hypertension) is when the force of blood against the walls of the blood vessels is too high. It can stress your heart and cause problems during pregnancy. - Pulmonary hypertension. This is a kind of high blood pressure that happens in the arteries in your lungs and on the right side of your heart.

- Placental abruption. This is a serious condition in which the placenta separates from the wall of the uterus before birth. The placenta grows in your uterus (womb) and supplies the baby with food and oxygen through the umbilical cord.

- Heart failure. This is when your heart can’t pump enough blood to the rest of your body.

- Thyroid storm. This is when your symptoms suddenly get much worse.

.jpg) It’s a rare, but life-threatening condition during pregnancy. Pregnant women who have thyroid storm are at high risk of heart failure.

It’s a rare, but life-threatening condition during pregnancy. Pregnant women who have thyroid storm are at high risk of heart failure.

Problems for babies can include:

- Premature birth. This is birth that happen too early, before 37 weeks of pregnancy.

- Goiter

- Low birthweight. This is when a baby is born weighing less than 5 pounds, 8 ounces.

- Thyroid problems. Antibodies that cause Graves’ disease cross the placenta during pregnancy. If you have Graves’ disease during pregnancy, your baby is at risk for thyroid conditions during and after birth. If you had treatment for Graves’ disease with radioactive iodine before pregnancy, your baby is at risk for Graves’ disease.

- Miscarriage or stillbirth. Miscarriage is when a baby dies in the womb before 20 weeks of pregnancy. Stillbirth is when a baby dies in the womb after 20 weeks of pregnancy.

How can hypothyroidism affect pregnancy?

Untreated hypothyroidism during pregnancy is linked to problems for women and babies during pregnancy and after birth.

Problems for women can include:

- Anemia. This is when you don’t have enough healthy red blood cells to carry oxygen to the rest of your body.

- Gestational hypertension. This is high blood pressure that starts after 20 weeks of pregnancy and goes away after you give birth.

- Preeclampsia

- Placental abruption

- Postpartum hemorrhage (also called PPH). This when a woman has heavy bleeding after giving birth. It’s a serious but rare condition. It usually happens within 1 day of giving birth, but it can happen up to 12 weeks after having a baby.

- Myxedema, a rare condition caused by severe, untreated hypothyroidism that can cause you to go into a coma and can cause death

- Heart failure.

This is when your heart doesn’t pump blood as well as it should. Heart failure cause by hypothyroidism is rare.

This is when your heart doesn’t pump blood as well as it should. Heart failure cause by hypothyroidism is rare.

Problems for babies can include:

- Infantile myxedema, a condition that’s linked to severe hypothyroidism. It can cause dwarfism, intellectual disabilities and other problems. Dwarfism (also called little people) is a condition in which a person is very short (less than 4 feet 10 inches as an adult). Intellectual disability causes a lower-than-average intelligence and a lack of skills needed to function in daily life.

- Low birthweight.

- Problems with growth and brain and nervous system development. The nervous system is made up of your brain, spinal cord and nerves. Your nervous system helps you move, think and feel. Untreated hypothyroidism, especially when it happens during the first trimester, can cause low IQ in a baby.

- Thyroid problems. This is rare, but it can happen in babies of women with Hashimoto’s disease because the antibodies can cross the placenta during pregnancy.

- Miscarriage or stillbirth

What is postpartum thyroiditis?

In about 1 to 21 in 100 women (1 to 21 percent), the thyroid becomes swollen in the first year after giving birth. This is an autoimmune condition called postpartum thyroiditis. It can cause your thyroid to be overactive, underactive and even a combination of both.

How are thyroid conditions treated during pregnancy and while breastfeeding?

Many medicines used to treat thyroid conditions during pregnancy are safe for your baby. Thyroid medicines can help keep the right level of thyroid hormones in your body. Your provider gives you blood tests during pregnancy to check your TSH and T4 levels to make sure your medicine is at the right amount (also called dose). T4 is a hormone made by your thyroid.

If you’re taking medicine for a thyroid condition before pregnancy, talk to your provider before you get pregnant. Your provider may want to adjust or change your medicine to make sure it’s safe for your baby. If you’re already taking thyroid medicine when you get pregnant, keep taking it and talk to your provider about it as soon as possible.

If you’re already taking thyroid medicine when you get pregnant, keep taking it and talk to your provider about it as soon as possible.

Treating hyperthyroidism. If you have mild hyperthyroidism, you may not need treatment. If it’s more severe, you may need to take an antithyroid medicine. This medicine causes your thyroid to make less thyroid hormone.

Most providers treat pregnant women with an overactive thyroid with antithyroid medicines called propylthiouracil in the first trimester and methimazole in the second and third trimesters. The timing of these medicines is important. Propylthiouracil after the first trimester can lead to liver problems. And methimazole in the first trimester may increase the risk of birth defects. Birth defects are health conditions that are present at birth. They change the shape or function of one or more parts of the body. Birth defects can cause problems in overall health, how the body develops, or how the body works.

Providers sometimes use radioactive iodine to treat hyperthyroidism. Pregnant women shouldn’t take this medicine because it can cause thyroid problems in the baby.

Pregnant women shouldn’t take this medicine because it can cause thyroid problems in the baby.

Antithyroid medicines are safe to take at low doses while you’re breastfeeding.

Treating hypothyroidism. Levothyroxine is the most common medicine used to treat an underactive thyroid during pregnancy. Levothyroxine replaces the thyroid hormone T4, which your own thyroid isn’t making or isn’t making enough of. It’s safe to take this medicine during pregnancy. Thyroid medicines that contain the T3 hormone aren’t safe to use during pregnancy.

If you had hypothyroidism before getting pregnant, you most likely need to increase the amount of medicine you take during pregnancy. Talk to your health care provider about your medicine as soon as you find out you’re pregnant. Your provider can check to make sure you’re taking the right dose by checking your TSH levels during pregnancy.

Talk to your provider about taking levothyroxine or other medicine to treat hypothyroidism while breastfeeding.

More information

- American Thyroid Association

- MotherToBaby

Last reviewed: February, 2019

See also: Prescription medicine during pregnancy

changes in modern medical and diagnostic paradigms

The problem of the relationship between autoimmune thyroid disease and reproductive disorders has become more and more discussed in recent years. Clinical and experimental studies have shown that impaired thyroid function leads to severe pregnancy complications: spontaneous pathological abortion, stillbirth, miscarriage, fetal abnormalities. This relationship was confirmed not only in women with thyrotoxicosis and hypothyroidism, but also in women with preserved thyroid function, in whose blood serum high titers of antibodies (AT) to thyroperoxidase (AT-TPO), thyroglobulin (AT-TG) and thyroid-stimulating receptors were detected. hormone (AT-rTTH) [1].

The prevalence of primary overt hypothyroidism among pregnant women is 2%, subclinical - up to 15% [2]. Hypothyroidism during pregnancy is most dangerous for the development of the fetus and, first of all, for its central nervous system (CNS) [3]. Moreover, the disease of the mother has a more adverse effect on the formation and functioning of the central structures of the fetal brain than hypothyroidism caused by a violation of the laying of the thyroid gland of the fetus [4, 5]. This is explained by the fact that in the first half of pregnancy (up to 18–20 weeks) the fetal thyroid gland practically does not function, neuronal migration and other important early stages of intrauterine brain development largely depend on the intake of maternal thyroid hormones from the mother.

Hypothyroidism during pregnancy is most dangerous for the development of the fetus and, first of all, for its central nervous system (CNS) [3]. Moreover, the disease of the mother has a more adverse effect on the formation and functioning of the central structures of the fetal brain than hypothyroidism caused by a violation of the laying of the thyroid gland of the fetus [4, 5]. This is explained by the fact that in the first half of pregnancy (up to 18–20 weeks) the fetal thyroid gland practically does not function, neuronal migration and other important early stages of intrauterine brain development largely depend on the intake of maternal thyroid hormones from the mother.

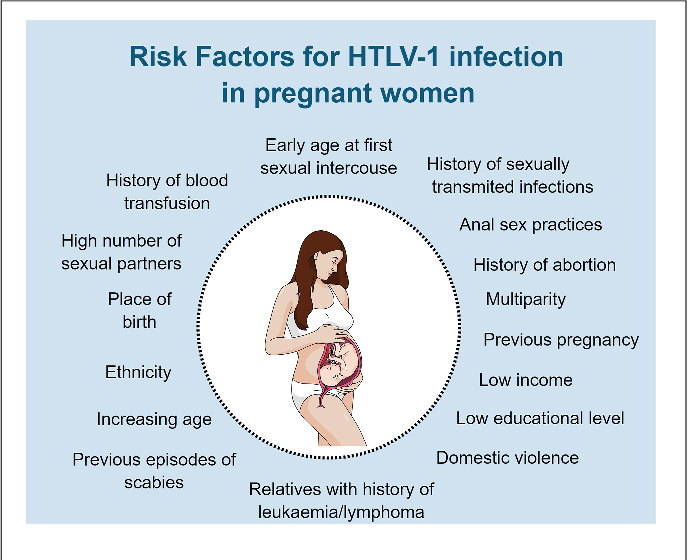

In recent years, special attention has been paid to the relationship between the carriage of antibodies to the thyroid gland and reproductive function in women. The frequency of detection of thyroid antibodies (AB-TPO, AB-TG) in pregnant women according to various sources is 10-20% [6]. It was noted that in women with elevated levels of thyroid antibodies, even in the euthyroid state, the frequency of complications of pregnancy and childbirth is significantly higher. In 16% of pregnant women with antibodies to the thyroid gland and normal levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) in the first trimester, there was an increase in TSH by more than 4 mU/l, and 33-50% developed postpartum thyroiditis [7]. A number of researchers have presented evidence of the negative impact of subclinical changes in the level of TSH in the presence of AB-TPO carriage on the incidence of obstetric complications - this is an increased risk of preterm birth and spontaneous pathological abortions, intrauterine growth retardation, gestational hypertension and other pathologies [8]. The association between the carriage of Ab-TPO and the risk of preterm birth (1.7-fold increase) was identified in two prospective population-based studies that included a total of 7585 pregnant women from two Dutch cohorts [9].

In 16% of pregnant women with antibodies to the thyroid gland and normal levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) in the first trimester, there was an increase in TSH by more than 4 mU/l, and 33-50% developed postpartum thyroiditis [7]. A number of researchers have presented evidence of the negative impact of subclinical changes in the level of TSH in the presence of AB-TPO carriage on the incidence of obstetric complications - this is an increased risk of preterm birth and spontaneous pathological abortions, intrauterine growth retardation, gestational hypertension and other pathologies [8]. The association between the carriage of Ab-TPO and the risk of preterm birth (1.7-fold increase) was identified in two prospective population-based studies that included a total of 7585 pregnant women from two Dutch cohorts [9].

Recently, there have been controversies in the scientific community related to the interpretation of laboratory tests to assess thyroid function during pregnancy. This is primarily due to the fact that during pregnancy there is a change in the metabolism of thyroid hormones and a dynamically changing interaction between the pituitary-thyroid systems of the mother and fetus. Currently available immunometric methods for the determination of thyroid hormones are essentially approximate and evaluative tests, are not direct methods for determining the concentration of the hormone and are very sensitive to changes in the level of binding proteins. In this regard, it is extremely relevant to use high-performance liquid chromatography in combination with tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) to develop reliable and accurate trimester-specific intervals for thyroid hormones during pregnancy.

In this review, we presented the modern principles of diagnostics and therapeutic approaches to pregnancy management in women with autoimmune thyroid pathology.

Pathogenesis

According to the literature, it is known that autoimmune diseases occur in 3-8% of the world's population [10], develop up to 10 times more often in women than in men, and are characterized by a long course. Great interest is currently being paid to the diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune diseases of the thyroid gland, especially in women, since this pathology has been actively progressing in recent decades [11] and affects the reproductive status [12]. Currently, there is no single point of view on the role of antibodies to thyroid tissue in the genesis of reproductive dysfunction in women. In the general population, an average of 10% of pregnant women are carriers of AT-TPO [13].

AIT is an HLA-associated disease. At the same time, atrophic and hypertrophic forms of AIT are associated with different haplotypes. However, the triggering processes in chronic AIT are not completely clear. In the blood of patients with AIT, as a rule, antibodies to various thyroid antigens are detected, most often AB-TPO, AT-TG, less often - blocking AB-rTTG. In addition, at the onset of the disease, stimulating AT-rTTH can also be detected transiently. Nevertheless, one of the controversial points in the mechanism of development of AIT is the role of antithyroid antibodies. According to researchers, Ab-TPO can lead to the formation of immune complexes that promote the release of biologically active substances that cause destructive changes in the thyroid gland, reducing its function [14]. According to other authors, AT-TPO is an indicator of destructive manifestations of the thyroid gland, and AT-TG is the result of compensatory mechanisms of the body, since the level of these antibodies depends on the number of stimulated receptors for thyroid hormones [15].

At the moment, it has been proven that the incidence of antithyroid antibodies does not coincide with the prevalence of both overt and subclinical hypothyroidism. This fact indicates that AT can be detected even in individuals who do not have functional or structural changes in the thyroid gland [16]. According to J. Hollowell et al. [17], AB-TPO was found in 12% of the examined patients without thyroid diseases and AB-TG in 10% [17]. At the same time, some researchers consider the detection of Ab-TPO to be a sign of a possible dysfunction of the thyroid gland in the future, and even low titers of these antibodies correlate with lymphoid infiltration of the thyroid tissue. Foreign researchers argue that an elevated level of AT-TPO is a statistically significant sign of AIT, and the presence of thyroid-specific antibodies in the blood serum (AT-TG 1:100 and above, AT-TPO 1:32 and above) is an indicator of autoimmune damage to the thyroid gland [ 17]. According to the research work of G. Karanikas et al. [19], elevated titers of AT-TPO correlate with a high frequency of production of Th/Tc1 cytokines by T cells, which are responsible for the damage to thyroid cells.

However, despite the significant interest of researchers in this pathology, there is currently no consensus on the etiology of AIT. Some scientists suggest genetic predisposition as the dominant cause in the development of AIT [20], in particular, when studying the genes of the HLA system, a combination with the genes HLA-B8, HLA-DR3, HLA-DR4 was indicated [21].

5 new gene variants TPO , ATXN2 , BACh3 , MAGI3 and KALRN associated with carriage of AT-TPO . The combination of these gene variants was associated with an increased risk of developing hypothyroidism and a reduced risk of developing goiter. Variations in the MAGI3 and BACh3 genes are associated with an increased risk of hyperthyroidism, and the MAGI3 variant is also associated with an increased risk of hypothyroidism [22].

A separate point for discussion is microchimerism (MC) - the presence in the tissues and / or circulatory system of the “host organism” of a small number of genetically distinct cells capable of long-term persistence. The presence of microchimeric cells in a woman's body is a common occurrence and a consequence of a normal pregnancy. The long-term consequences of this phenomenon have become the subject of close attention relatively recently. Currently, MC is considered as one of the promising theories of the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. This phenomenon is associated with the risk of developing thyroid dysfunction as a result of its autoimmune damage, and can also have a direct impact on the course of subsequent pregnancies and the implementation of autoimmune reactions. Fetal and maternal microchimeric cells are able to persist in the body for a long time and can be detected in the blood and tissues decades after the end of pregnancy [23–25]. Mc is more often detected in thyroid tissue and peripheral blood in patients with autoimmune thyroid disorders than in healthy individuals [26]. It is assumed that Mc is able to provoke a local immune reaction against maternal antigens in the gland tissue, and also be a target for the maternal immune system. The prevalence of suspected genetic markers among mother-infant couples with fetal M.Ch. also supports the involvement of MH in the pathogenesis of autoimmune thyroid disorders. This phenomenon is considered as one of the attractive hypotheses of the genesis of autoimmune thyroid disorders, which could explain the prevalence of the incidence among women of reproductive age and frequent manifestations in the postpartum period.

Autoimmune thyroiditis and pregnancy

When pregnancy occurs in women who are carriers of Ab-TPO without impaired thyroid function, the risk of developing hypothyroidism and relative gestational hypothyroxinemia increases, which can lead to a number of perinatal and obstetric complications [27]. The pathogenesis of these disorders remains unclear to date. It is possible that antithyroid antibodies are a marker of generalized autoimmune dysfunction, which results in spontaneous pathological abortion. According to the literature, 30-50% of AT carriers develop thyroid dysfunction after childbirth. According to different authors, thyroid dysfunction in the postpartum period can develop in women even in the absence of antibodies to the thyroid gland. Thus, there are no clear prognostic criteria for the development of thyroid dysfunction both during pregnancy, in the postpartum period, and throughout life.

Diagnostic difficulties

Thyroid dysfunction can occur at any stage of pregnancy, it should be borne in mind that the principles of diagnosis and treatment of thyroid diseases in pregnant women differ significantly from those generally accepted. There are various methods of screening for thyroid dysfunction: from a simple examination of only high-risk pregnant women, to a total screening of all pregnant women, regardless of the gestational age. On the one hand, given the prevalence and potential danger of thyroid disorders during pregnancy, a number of professional associations and communities recommend an assessment of thyroid function in all pregnant women and women planning pregnancy. On the other hand, researchers from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology argued as early as 2002 that proposals for routine screening of pregnant women are premature in the absence of data showing improved outcomes with levothyroxine sodium therapy [28]. Current work in this area shows mixed results. We now have the report of the Cochrane Research Group, which published in 2015 an analysis of two randomized controlled trials involving 26,408 women (one study included 21,839women and others - 4562) [29]. The authors report that universal screening for thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy increased the number of women diagnosed with hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism and, as a result, increased the number of patients treated for these conditions.

However, routine screening and follow-up treatment failed to identify clear benefits or negative responses for women and/or their children. No change in the proportion of women with preeclampsia and preterm birth (based on a study of 4562 women), the number of children with disabilities (intelligence quotient (IQ) less than 85 at age 3) - a study of 794 children born to mothers with hypothyroidism). Although the studies included large sample sizes, no clear differences in outcomes for mothers and their children were found between routine screening and screening at the time of seeking care (case finding) or no screening at all. Thus, it is clear that more research and evidence is needed to evaluate the potential short-term and long-term advantages or disadvantages of various screening methods.

It is important to clarify that the detection of an increase in the level of TSH is not always synonymous with a decrease in the concentration of free thyroxine 4 (svT 4 ). Most often, an elevated TSH level in a pregnant woman is detected when the content of fT 4 is normal - this is regarded as subclinical hypothyroidism. Conversely, a low level of fT 4 can be detected against the background of a normal TSH level - a similar situation is called isolated hypothyroxinemia (IH). IG of pregnant women is rare, if it is established in the first trimester, therapy with levothyroxine sodium may be recommended. The rationale for the appointment of therapy is the proven association of IG at the beginning of pregnancy with disorders of the neuropsychic development of the child. But at the moment, there are no studies demonstrating a clinically significant improvement in neurocognitive functions in children born to mothers with IH due to treatment. Therapy with levothyroxine sodium is not recommended for IG detected in the II and III trimesters of pregnancy. Since the minimum level of svt is 4 often observed and physiologically determined at the end of pregnancy, there is a high risk of developing iatrogenic thyrotoxicosis in the absence of evidence of the potential beneficial effect of levothyroxine sodium therapy.

Increased levels of thyroid hormones during pregnancy are regarded as a physiological process of adaptation, but, according to recent studies, excessively high concentrations of fT 4 have no less negative effect on the child's CNS than its low content: hyperthyroxinemia can contribute to a decrease in the IQ of the child and a decrease in gray volume substances [30]. In this regard, it is necessary to take a very balanced approach to the appointment of levothyroxine sodium and evaluate the justification for any medical interventions during pregnancy, taking into account not only the health of the woman, but also the child.

In view of the fact that during pregnancy there is a change in the activity of the thyroid gland and the interaction of the pituitary-thyroid systems of the mother and the fetus changes dynamically, an accurate assessment of the function of the thyroid gland in the mother remains a difficult task at the present time. There is an active discussion in the scientific community and a single agreement has not yet been reached regarding the meaning of the “norm” and, accordingly, the tactics of management. The principal point of discussion is the issue of determining diagnostic reference levels and interpreting the results of laboratory tests to assess hormonal status during pregnancy.

The TSH level is the first to respond to an increase in thyroid activity during pregnancy: there is a downward shift in the TSH level, while both the lower (by about 0.1-0.2 mU / l) and the upper limit of the maternal TSH level (by about 0 .5–1.0 mU/l) relative to the standard limits of TSH [31]. The greatest decrease in serum TSH levels is observed during the first trimester (the peak of TSH secretion by the 8th week of pregnancy) due to direct stimulation of the placental human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) TSH receptor, thereby directly increasing the production of thyroid hormones. In the future, as pregnancy progresses, the level of TSH gradually increases and reaches a maximum in the third trimester, but generally remains lower than in non-pregnant women [32]. Since the concentration of hCG is higher in a multiple pregnancy than in a single pregnancy, the decrease in the boundaries of the control interval for the TSH level in this case is more significant [31].

Over the past two decades, a number of recommendations and guidelines have been published regarding aspects of the diagnosis and treatment of thyroid diseases during pregnancy and the postpartum period. It is accepted by the American Thyroid Association (ATA) that reference intervals for TSH levels during pregnancy should be narrowed by the high value, and since 2011, trimester-specific TSH levels have been used in many countries around the world and in our country. Note that the ATA recommendations were based on the results of 6 cohort studies conducted in the United States and some European countries, and it was also separately stipulated that these standards are offered only for laboratories that, for whatever reason, do not have their own established standards. Recommended trimester-specific reference intervals for TSH were as follows: 1st trimester 0.1–2.5 mU/L; II trimester 0.2-3 mU/l; III trimester 0.3-3 mU/l.

European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of thyroid diseases during pregnancy, published in 2012, demonstrate the agreement of the expert community to reduce the upper limits of trimester-specific reference ranges for TSH levels in pregnant women [33]. It is these ranges that are currently used by domestic clinicians to assess the function of the thyroid gland and as target when performing replacement therapy for pregnant women with hypothyroidism. In 2017, updated ATA clinical guidelines were released, which revised the reference TSH values for pregnant women. This is based on recent screening studies showing that pregnancy in general is characterized by relatively low TSH levels in virtually all populations, but the extent of this decline varies greatly between different racial and ethnic groups. It is also necessary to take into account differences in iodine availability. Studies involving pregnant women in Asia, India, and some European countries have demonstrated significant geographical heterogeneity in the intensity of the fall in TSH levels in the first trimester, revealing the predominance of a slight decrease in upper values [34–37]. Similar data were obtained from studies of pregnant women in Korea — a moderate decrease in TSH in the first trimester by 0.

5–1.0 mU/l [38]. A recent study of 4800 pregnant women in China showed that although a downward shift in the TSH reference range occurred at weeks 7–12, the upper reference limit was not significantly lowered from 5.31 to 4.34 mU/L [ 35].

Most research groups recognize the limited utility of the current trimester-specific ranges for TSH, as they are based on populations with adequate iodine intake, and the sample included women without thyroid A.T. The relevance of conducting national studies in order to establish population reference values of thyroid hormones, taking into account iodine intake, the presence of antibodies to thyroid tissue and, according to some studies, body mass index becomes obvious.

Thus, taking into account the accumulated data and the latest ATA recommendations, at present, the ideal option is to use TSH “normal” intervals for pregnant women, defined for a specific region (country), taking into account ethnic and geographical characteristics. Unfortunately, in Russia at present there are no data from national population studies of TSH levels and clinical recommendations based on them for the diagnosis and treatment of thyroid diseases during pregnancy. In such a situation, the ATA clinical guidelines suggest that professionals use a TSH level of 4 mU/L as the upper “normal” reference value, which for most laboratory tests represents a decrease in the upper population TSH value of about 0.5 mU/L.

Determining the level of T 4 during pregnancy

Free T 4 is the biologically active part of the total T 4 , which is only about 0.03%, and the main volume of the hormone is associated with serum proteins, primarily with thyroxin-binding globulin (TSG). Determination of the content of fT 4 in the vast majority of laboratories is carried out by immunometric methods, the accuracy of the results of which depends on many factors: dilution, temperature, buffer composition, AT affinity, etc. [39]. Currently available immunometric methods for the determination of thyroid hormones are essentially approximate and evaluative tests (do not give an accurate indication of the hormone concentration) and are very sensitive to changes in the level of binding proteins [40]. Determining the content of fT 4 during pregnancy is associated with methodological difficulties arising as a result of biochemical changes occurring in the mother's body [41]. Serum of pregnant women is characterized by higher concentrations of TSH, which peaks around the 16th week of pregnancy, non-esterified fatty acids and lower levels of albumin compared to non-pregnant women. High concentrations of TSH tend to lead to higher total T 4 and, accordingly, to a regular, from a methodological point of view, underestimation of the level of svt 4 [42]. As a result, clinicians need to differentiate between true hypothyroxinemia in pregnant women, which requires the appointment of replacement therapy with levothyroxine sodium, and methodically determined underestimation of the level of FTT 4 , which does not require any intervention.

Because serum levels of fT 4 fluctuate significantly during pregnancy and there is wide variability between measurement methods, interpretation of measured values of fT 4 requires both method specific and trimester specific ranges.

The possibility of using new HPLC-MS/MS technology to develop reliable and proven trimester-specific intervals for thyroid hormones during pregnancy has been widely discussed. The emergence and development of HPLC-MS/MS technology provides high performance, almost 100% specificity, and the necessary sensitivity compared to immunoassay methods [43, 44]. Currently, MS/MS technology is widely used for routine diagnostics in endocrinological laboratories, and primarily for determining the main spectrum of steroids, as well as their numerous metabolites.

Subclinical hypothyroidism (SH) during pregnancy

Observational studies covering more than the last three decades show that FH statistically significantly increases obstetric risk, the incidence of pregnancy complications and adverse outcomes for the child, primarily for its CNS [45]. At the same time, there is no evidence that treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism during pregnancy with levothyroxine sodium improves cognitive functions in a child. This was demonstrated in the CATS study, which screened thyroid function in 21,846 pregnant women [46]. More recently, a prospective 5-year study conducted in the United States evaluated the results of treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism, detected for the first time in the first trimester of pregnancy [47]. A total of 9 screeningsOf 7,288 pregnant women, the study included 677 women with SH, defined as an increase in TSH levels of more than 4.0 mU/l with a normal FTS concentration of 4 . An analysis of the "breakpoint" - IQ score in children under 5 years of age - did not reveal the benefits of treating subclinical hypothyroidism during pregnancy: therapy with levothyroxine sodium did not lead to a clinically significant improvement in cognitive functions in children under 5 years of age. As well as no benefits of therapy with levothyroxine sodium in relation to the course of pregnancy and reducing the risk of obstetric complications have been identified.

Some results of the study are of interest, for example, a dynamic assessment of thyroid hormones in the first trimester - a trend towards a decrease in the content of fT 9 was noted0069 4 only when the TSH level is 4.8 mU/l or more.

If FH is detected in a woman trying to conceive naturally in the absence of anti-thyroid antibodies, therapy with low doses of levothyroxine sodium (25–50 mcg) may be recommended to avoid progression of hypothyroidism in the event of pregnancy.

If FH is diagnosed in a woman planning IVF, levothyroxine sodium is recommended to achieve a TSH level of less than 2.5 mU/L. There is insufficient evidence that levothyroxine sodium therapy improves pregnancy success after assisted reproductive technologies in women who carry TPO antibodies without reducing thyroid function. However, the administration of levothyroxine sodium in this situation may be considered in light of its potential benefits compared to its minimal risk. In such cases, 25–50 micrograms of levothyroxine sodium is a typical starting dose.

Treatment

Available evidence supports the benefit of initiating therapy as early as possible. Therefore, with manifest hypothyroidism first detected during pregnancy, it is necessary to promptly prescribe levothyroxine sodium. The calculation of the dose of the drug for starting treatment is defined as 2.3 μg per 1 kg of body weight per day with the first control of the TSH level after 2 weeks. In the future, to correct therapy, control determinations of TSH levels should be performed every 4 weeks throughout the first half of pregnancy (up to 16-20 weeks of pregnancy) and at least once in the period from the 26th to the 32nd week. The goal of hypothyroidism therapy is to maintain TSH levels within trimester-specific reference intervals (if defined), and if this is not available, then it is reasonable to maintain TSH levels below 2.5 mU/L [31]. It has not been confirmed that achieving a lower TSH level (less than 1. 5 mU/L) is associated with the clinical benefit of such therapy [48]. If a woman is already receiving levothyroxine sodium, its dose should be increased by 30-50%.

In the presence of an increased risk of developing hypothyroidism during pregnancy, only dynamic monitoring is recommended, in particular, this applies to patients with euthyroidism and carriage of antibodies to thyroid tissue or after surgical treatment (thyroid resection, hemithyroidectomy) or radioiodine therapy for thyroid disease. Based on the conclusions made on the basis of studies on the treatment of hypothyroidism during pregnancy, it can be recommended to monitor the level of TSH in these women every 4 weeks during the first half of pregnancy, then it is considered sufficient to control the level of TSH in the period of 26-32 weeks of pregnancy [31, 49]. Since it has not been proven that levothyroxine sodium therapy can reduce the risk of preterm birth and spontaneous pathological termination of pregnancy in AT carriers of pregnant women without thyroid dysfunction, prophylactic treatment with levothyroxine sodium preparations is not carried out in this group [31].

Women who received levothyroxine sodium therapy before pregnancy should reduce the dose of the drug to baseline after delivery with TSH control after 6 weeks. If levothyroxine sodium is first started during pregnancy (especially when the dose of the drug is ≤50 µg/day), then after delivery, treatment should be discontinued with TSH control also after 6 weeks [31]. Current clinical practice is mainly focused on preventing the negative consequences of low thyroid hormone levels during pregnancy. At the same time, recent research data have shown that both low and high concentrations of thyroid hormones have a negative impact on the development of the fetal brain and its morphological structure, and are also closely associated with neuropsychiatric disorders in children and adolescents [30, 50, 51 ].

In 2016, the results of a prospective cohort population study integrated into the Generation R Study (Rotterdam, the Netherlands) were published, in which the association of maternal thyroid function with the child's IQ (assessed using non-verbal intelligence tests) and brain morphology (assessed using magnetic -resonance tomography, MRI) [30].

IQ data were obtained from 3839 children, and MRI of the brain was performed on 646 children. Concentration of svt 4 in maternal serum showed an inverted U-shaped relationship with IQ and gray matter volume in the child. Equally for both low and high concentrations of fT 4 , this association corresponded to a reduction in the average level of IQ by 1.4–3.8 points. At the same time, the level of maternal TSH was not associated with a decrease in the level of children's IQ or disturbances in brain morphology. All associations remained similar after excluding women with overt hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. Established relationship between the level of svt 4 mother and child's cortical volume suggest that levothyroxine sodium therapy during pregnancy, which is often initiated in women with subclinical hypothyroidism, may be associated with a potential risk of adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in the child when the goal of treatment is to maintain the level of svt 4 at the upper limit of normal.

Micronutrients and autoimmune thyroiditis

It seems appropriate to consider separately the issue of prescribing micronutrients to patients with AIT. Iodine in a physiological dose (about 200 mcg/day) is not able to induce the development of hypothyroidism and does not adversely affect thyroid function in the already existing hypothyroidism caused by AIT. In the presence of antibodies to the thyroid gland and in the absence of a decrease in its function, it is recommended to prescribe iodine preparations for the entire period of pregnancy and lactation [52]. When prescribing drugs containing iodine in pharmacological doses (more than 1 mg / day) to patients with AIT, one should be aware of the possible risk of manifestation of hypothyroidism (or an increase in the need for thyroid hormones in subclinical and overt hypothyroidism) and monitor thyroid function. Currently, discussions are underway about the positive effect of selenium, however, in accordance with the 2017 ATA recommendations, the administration of selenium preparations to pregnant women with high titers of Ab-TPO is not recommended [31]. Further research is needed on this topic.

The urgency of the problem of diagnosing and treating hypothyroidism in women of reproductive age is determined by the high incidence of infertility, obstetric and perinatal complications, since reduced thyroid function plays an important role. A pregnant woman with hypothyroidism has an increased risk of obstetric complications: intrauterine fetal death, hypertension, placental abruption, perinatal complications. Thyroid hormone therapy significantly improves pregnancy outcomes. Hypothyroidism in pregnant women is an absolute indication for the appointment of replacement therapy at a calculated dose of 2.3 μg per 1 kg of body weight per day. If a woman with compensated hypothyroidism plans pregnancy, the dose of levothyroxine sodium should be increased immediately after its onset by 25-30%. In the future, the control of the adequacy of therapy is carried out by the level of thyroid-stimulating hormone, which must be carried out every 6-8 weeks.

The management of subclinical hypothyroidism and the appointment of replacement therapy remain debatable. Based on the opinion of the majority of experts, given the presence of proven potential risks for the mother and fetus, it is recommended to start replacement therapy with levothyroxine sodium with a subclinical increase in the level of thyroid-stimulating hormone against the background of the presence of an increased titer of antibodies to the thyroid gland.

Recent considerations suggest that the upper trimester-specific cut-off values for thyroid-stimulating hormone can be increased and a thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 4 mU/L can be used.

Since geographic and ethnic differences in the population influence thyroid-stimulating hormone levels in pregnant women, this should be taken into account when developing reference intervals along with iodine intake and anti-thyroid tissue antibody carriage using high performance liquid chromatography in combination with tandem mass spectrometry.

Funding source. Search and analytical work during the preparation of the manuscript was carried out with the financial support of the Russian Science Foundation grant No. 17-75-30035 “Autoimmune endocrinopathies with multiple organ lesions: genomic, postgenomic and metabolomic markers. Genetic risk prediction, monitoring, early predictors, personalized correction and rehabilitation.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Credits

Nadezhda Mikhailovna Platonova — https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6388-1544; eLibrary SPIN: 4053-3033

Makolina Natalia Pavlovna — https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3805-7574; eLibrary SPIN: 7210-9512

Rybakova Anastasia Andreevna — e-mail: [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1248-9099; eLibrary SPIN: 8275-6161

Ekaterina Anatolyevna Troshina — https://orcid. org/0000-0002-8520-8702; eLibrary SPIN: 8821-8990

Corresponding author: Rybakova Anastasia Andreevna — https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1248-9099;br />eLibrary SPIN: 8275-6161

How to detect autoimmune thyroiditis | Directory of medical laboratory Optimum (Sochi, Adler)

- Home

- How to recognize the disease

- Pregnancy and childbirth

- Autoimmune thyroiditis in pregnancy

More about the doctor

Autoimmune thyroiditis (Hashimoto's disease) is an autoimmune disease that affects the thyroid gland. Lack of therapy leads to tissue destruction and insufficiency of its function. Against the background of pregnancy, autoimmune thyroiditis can complicate its course, as well as lead to impaired fetal development.

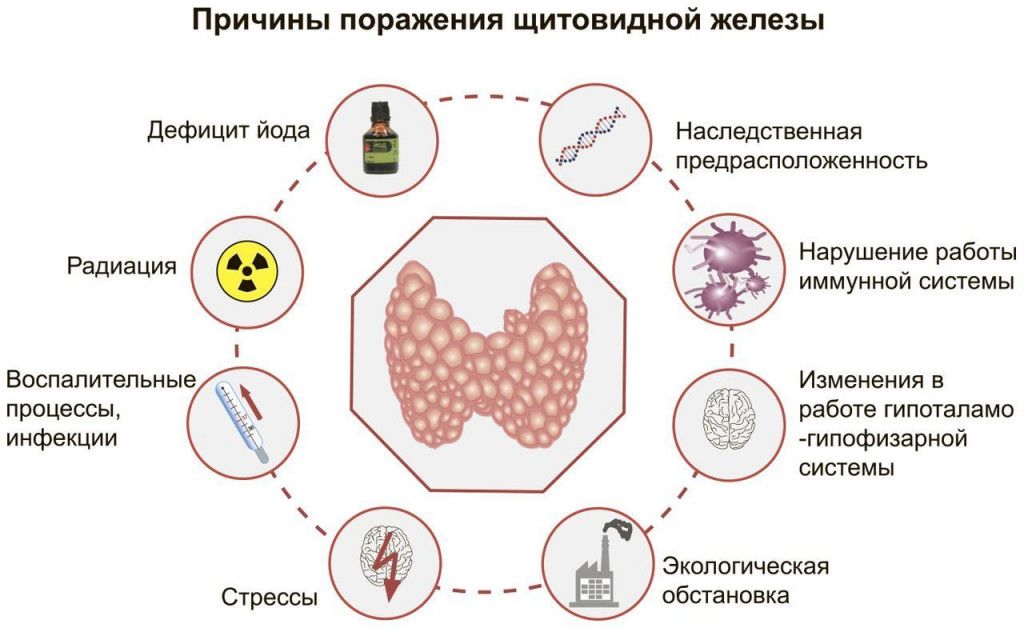

Causes of development

The main reason for development is the launch of the production of antibodies by the body against thyroid cells. As a result, thyrocytes are destroyed and do not produce the necessary hormones. As the disease progresses, the remaining cells fail to perform their function, leading to hypothyroidism.

Provoking factors include:

- Hereditary predisposition.

- Past infection.

- Traumatic effect.

- Excessive sun exposure.

- Radiation exposure.

Pathogenesis

From the early stages of pregnancy, a natural decrease in immune forces is noted, which leads to a slowdown in the production of antibodies by the woman's body. Their reduction stops the destruction of the thyroid gland. In addition, the hormonal background stabilizes and the patient's well-being improves.

Deterioration of health is noted after the birth of a child. There is a massive death of thyroid cells and the development of severe hypothyroidism.

Symptoms

Clinical manifestations develop gradually in most cases. They depend on the course of the disease.

Hypertrophic form is accompanied by the appearance of nervous excitability, irritability, tearfulness, tremor, sweating, diarrhea, tachycardia, exophthalmos, high blood pressure.

In the atrophic form , the patient suffers from weakness, lethargy with memory impairment, constant chills, headaches, decreased appetite, weight loss, decreased blood pressure and heart rate, and hair loss.

During pregnancy, autoimmune thyroiditis causes an increase in the tone of the uterus, the development of pain, excessive weight gain, the appearance of edema and impaired formation of the thyroid gland, as well as the brain in the fetus.

After childbirth with autoimmune thyroiditis, lactation is inhibited.

Methods of diagnosis

The diagnosis begins with the clarification of the patient's complaints, medical history, and clarification of provoking factors. The thyroid gland is examined with its palpation. The hypertrophic variant is characterized by an increase in the size of the organ. It is painless, compacted and not soldered to the surrounding tissues. With hypothyroidism, the thyroid gland decreases in size and differs from a healthy one in greater density.

The main diagnostic methods necessary for making a diagnosis include:

- Performing a blood test to determine the level of hormones. With autoimmune thyroiditis, the level of antibodies to thyroglobulin, TSH increases, and also in the stage of hyperthyroidism, the level of T3, T4 increases. In hypothyroidism, T3 and T4 are reduced. Control of the hormonal profile is indicated from the moment of establishing pregnancy and until delivery on a monthly basis.

- Ultrasound . Pregnant women are shown to perform it every two months. The disease is characterized by a change in the structure with a decrease in tissue density, its heterogeneity, as well as the formation of cystic inclusions.

- Thyroid puncture . If a malignant process or rapid growth of individual formations is suspected, a puncture is performed followed by a histological examination.

Treatment

- The treatment of autoimmune thyroiditis is based on taking hormonal drugs. The patient is prescribed funds based on the level of hormones.

- For treatment use replacement therapy with constant dosage adjustment. The dose of the drug increases if the concentration of TSH increases.

- In thyrotoxicosis, the appointment of symptomatic agents to reduce the severity of tachycardia, diarrhea and mental disorders is indicated.

- Surgical treatment is used only with the rapid growth of the thyroid gland with a sharp deterioration in well-being caused by compression of the vessels and trachea.

Possible complications

If untreated during pregnancy, there is a high rate of complications. Among them, the most frequently noted threat of abortion, spontaneous miscarriage and possible fetal malformations.