Signs your baby is lactose intolerant

Lactose Intolerance Symptoms in Babies: What to Know

Cow’s milk can do a number on the tummy — in adults and children. While that doesn’t always stop us from eating a bowl of ice cream, we may pay for it later with that familiar stomach gurgling.

Usually, it’s the lactose in milk that’s the culprit of tummy troubles. If you’re lactose intolerant, your body can’t digest lactose — the sugar in dairy products. And as a result, drinking milk or eating dairy products like cheese or yogurt can cause symptoms ranging from stomach cramps to diarrhea.

Many adults live with a lactose intolerance. In fact, it’s estimated to affect as many as 30 to 50 million American adults. But more rarely, babies can have it as well.

Here’s what you need to know about lactose intolerance in babies, as well as how an intolerance affects breastfeeding and formula feeding.

Of course, if your baby appears to have trouble digesting dairy, this doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re lactose intolerant. Their symptoms could be caused by something else. (Nothing about parenthood is ever simple, is it?)

But typically, symptoms of a lactose intolerance in babies include:

- diarrhea (check out our guide to lactose intolerant baby poop)

- stomach cramping

- bloating

- gas

Since babies can’t talk, they can’t explain what’s bothering them. So it’s not always easy to tell when they’re having stomach issues.

Signs of stomach pain might include:

- clenching their fists

- arching their backs

- kicking or lifting their legs

- crying while passing gas

A bloated stomach may look slightly larger than normal and feel hard to the touch.

Another sign of lactose intolerance is symptoms starting shortly after feedings — within 30 minutes to 2 hours of consuming breast milk, milk-based formula, or solid foods containing dairy.

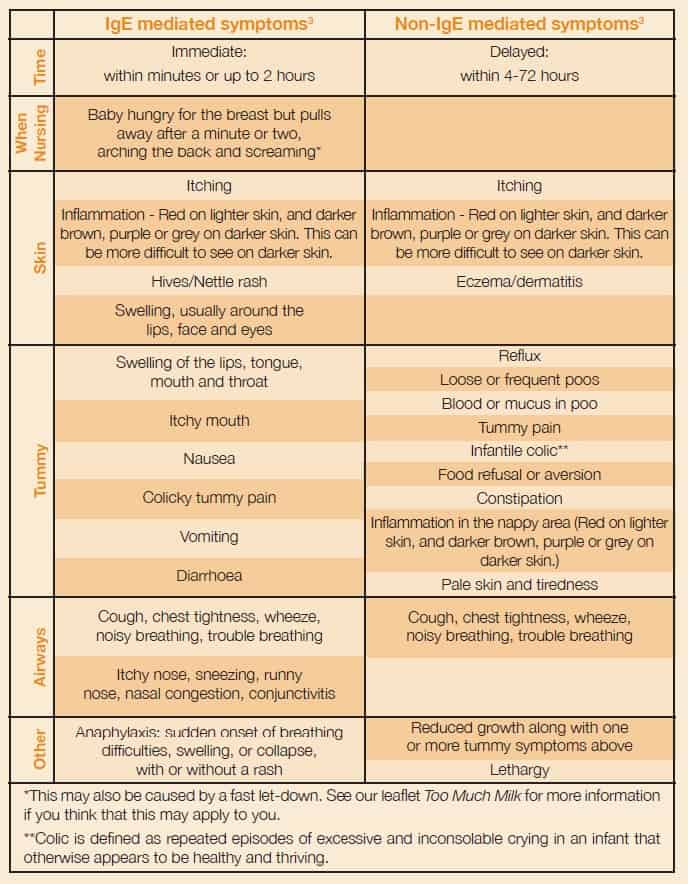

Keep in mind, too, that your baby might not have a problem with lactose, but rather a milk allergy.

Milk allergy symptoms are similar to symptoms of a lactose intolerance, but these conditions aren’t the same.

A milk allergy is a type of food allergy that occurs when the immune system overreacts to dairy. If your baby has a milk allergy, they may have an upset stomach and diarrhea. But they’ll also have symptoms that don’t occur with an intolerance:

- wheezing

- coughing

- swelling

- itching

- watery eyes

- vomiting

If you suspect a milk allergy — even a mild allergy — see your doctor. A milk allergy can advance and cause severe symptoms like a drop in blood pressure, trouble breathing, and anaphylaxis. According to Food Allergy Research and Education, milk allergies affect about 2.5 percent of children under 3 years old.

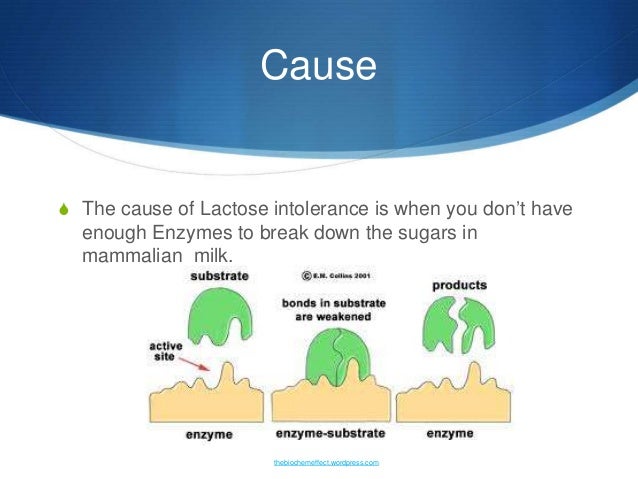

Most people with a lactose intolerance don’t develop symptoms until later in life when their body’s natural production of lactase — the enzyme that helps the body digest lactose — declines.

This decline doesn’t usually take place until later in childhood, during the teenage years, or in adulthood. So lactose intolerance in babies under age 1 is pretty rare — but it’s not impossible.

So lactose intolerance in babies under age 1 is pretty rare — but it’s not impossible.

Congenital lactase deficiency

Some babies have a lactose intolerance because they’re born without any lactase enzymes to begin with. This is known as congenital lactase deficiency, and if your baby has this deficiency, you’ll know it almost immediately after birth. They’ll have symptoms after drinking breast milk — which also contains lactose — or formula based in cow’s milk.

It’s unknown how many babies are born with this condition worldwide. Interesting fact: It seems to be most common in Finland, where about 1 in 60,000 newborns can’t digest lactose. (Note that this is still pretty rare!)

The cause of this deficiency is a mutation of the LCT gene, which essentially instructs the body to produce the enzyme needed to digest lactose. This is an inherited condition, so babies inherit this gene mutation from both of their parents.

Developmental lactase deficiency

Some premature infants are born with a developmental lactase deficiency. This is a temporary intolerance that occurs in infants born before their small intestines are fully developed (generally, before 34 weeks gestation).

This is a temporary intolerance that occurs in infants born before their small intestines are fully developed (generally, before 34 weeks gestation).

Also, some babies develop a temporary lactose intolerance after a viral illness, like gastroenteritis.

If your baby has signs of a lactose intolerance, don’t diagnose the condition yourself. Talk to your pediatrician. They’ll have more experience distinguishing between a lactose intolerance and a milk allergy.

Since a lactose intolerance is uncommon in infants, your doctor may refer you to an allergist to rule out a dairy allergy after also ruling out other common digestive issues.

The allergist may expose your baby’s skin to a small amount of milk protein, and then monitor their skin for an allergic reaction.

If your baby doesn’t have a milk allergy, your doctor may take a stool sample to check the acidity of their poop. Low acidity can be a sign of lactose malabsorption, and traces of glucose is evidence of undigested lactose.

Your doctor may also suggest removing lactose from their diet for 1 to 2 weeks to see if their digestive symptoms improve.

If diagnostic testing confirms a lactose intolerance, don’t immediately panic and stop breastfeeding. Whether you’re able to continue breastfeeding depends on the type of lactase deficiency.

For example, if your baby develops a lactose intolerance after a viral illness, the general recommendation is to continue breastfeeding. Breast milk can give their immune system a boost and help heal their gut.

If your infant has developmental lactase deficiency due to a premature birth, this condition only lasts a few weeks or months. So your baby may eventually drink milk-based formula or breast milk with no problem, although you’ll need to use lactose-free infant formula in the meantime.

But breastfeeding isn’t an option if your baby has a congenital lactase deficiency. The lactose in your breast milk can cause severe diarrhea and lead to dehydration and electrolyte loss. You’ll need to feed your baby with lactose-free infant formula.

You’ll need to feed your baby with lactose-free infant formula.

Lactose intolerance following a viral illness or a premature birth is usually temporary — hooray! — and your baby’s body may eventually produce normal levels of the lactase enzyme to digest the sugar in milk.

But a congenital lactase deficiency is a lifelong condition, and you’ll need to modify your little one’s diet to avoid symptoms.

The good news is that lactose-free infant formulas contain nutrients — like calcium, vitamin D, and vitamin A — that babies receive from drinking lactose-based products. (And there’s never been a better time to grow up with lactose intolerance, as so many people are going dairy-free by choice.)

Foods to avoid

When you buy food for your baby, read labels and don’t purchase items containing lactose (whey, milk by-products, nonfat dry milk powder, dry milk solids, and curds).

Popular baby-friendly foods that may contain lactose include:

- yogurt

- prepared oatmeal

- formula

- instant mashed potatoes

- pancakes

- biscuits (including teething biscuits)

- cookies

- pudding

- sherbet

- ice cream

- cheese

Q: If my baby’s lactose intolerant and I’m breastfeeding, will it help if I quit eating lactose or will I still have to switch to a dairy-free formula?

A: Taking dairy or lactose out of your diet will not reduce the lactose in your breast milk. Breast milk naturally contains lactose.

Breast milk naturally contains lactose.

Depending on the type of lactose intolerance your baby has, you may have to switch to a lactose-free formula. Some lactose intolerance is a short-term situation and will resolve over time. Congenital lactose intolerance will not go away and your child will have to remain lactose free for their whole life.

Please make all changes to your baby’s diet with the assistance of your healthcare provider.

— Carissa Stephens, RN

Answers represent the opinions of our medical experts. All content is strictly informational and should not be considered medical advice.

Was this helpful?

An inability to digest the sugar in milk can be uncomfortable for a baby, but diarrhea, gas, and stomach pain don’t always mean lactose intolerance. These symptoms could indicate a milk allergy, general digestive problems common in the first 3 months of life, or something else.

If you believe that your baby has trouble digesting milk, see your pediatrician for a diagnosis. And take heart — while a diagnosis may seem daunting at first, it’ll put you well on your way to having a happier, less fussy baby.

And take heart — while a diagnosis may seem daunting at first, it’ll put you well on your way to having a happier, less fussy baby.

Lactose Intolerance Symptoms in Babies: What to Know

Cow’s milk can do a number on the tummy — in adults and children. While that doesn’t always stop us from eating a bowl of ice cream, we may pay for it later with that familiar stomach gurgling.

Usually, it’s the lactose in milk that’s the culprit of tummy troubles. If you’re lactose intolerant, your body can’t digest lactose — the sugar in dairy products. And as a result, drinking milk or eating dairy products like cheese or yogurt can cause symptoms ranging from stomach cramps to diarrhea.

Many adults live with a lactose intolerance. In fact, it’s estimated to affect as many as 30 to 50 million American adults. But more rarely, babies can have it as well.

Here’s what you need to know about lactose intolerance in babies, as well as how an intolerance affects breastfeeding and formula feeding.

Of course, if your baby appears to have trouble digesting dairy, this doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re lactose intolerant. Their symptoms could be caused by something else. (Nothing about parenthood is ever simple, is it?)

But typically, symptoms of a lactose intolerance in babies include:

- diarrhea (check out our guide to lactose intolerant baby poop)

- stomach cramping

- bloating

- gas

Since babies can’t talk, they can’t explain what’s bothering them. So it’s not always easy to tell when they’re having stomach issues.

Signs of stomach pain might include:

- clenching their fists

- arching their backs

- kicking or lifting their legs

- crying while passing gas

A bloated stomach may look slightly larger than normal and feel hard to the touch.

Another sign of lactose intolerance is symptoms starting shortly after feedings — within 30 minutes to 2 hours of consuming breast milk, milk-based formula, or solid foods containing dairy.

Keep in mind, too, that your baby might not have a problem with lactose, but rather a milk allergy.

Milk allergy symptoms are similar to symptoms of a lactose intolerance, but these conditions aren’t the same.

A milk allergy is a type of food allergy that occurs when the immune system overreacts to dairy. If your baby has a milk allergy, they may have an upset stomach and diarrhea. But they’ll also have symptoms that don’t occur with an intolerance:

- wheezing

- coughing

- swelling

- itching

- watery eyes

- vomiting

If you suspect a milk allergy — even a mild allergy — see your doctor. A milk allergy can advance and cause severe symptoms like a drop in blood pressure, trouble breathing, and anaphylaxis. According to Food Allergy Research and Education, milk allergies affect about 2.5 percent of children under 3 years old.

Most people with a lactose intolerance don’t develop symptoms until later in life when their body’s natural production of lactase — the enzyme that helps the body digest lactose — declines.

This decline doesn’t usually take place until later in childhood, during the teenage years, or in adulthood. So lactose intolerance in babies under age 1 is pretty rare — but it’s not impossible.

Congenital lactase deficiency

Some babies have a lactose intolerance because they’re born without any lactase enzymes to begin with. This is known as congenital lactase deficiency, and if your baby has this deficiency, you’ll know it almost immediately after birth. They’ll have symptoms after drinking breast milk — which also contains lactose — or formula based in cow’s milk.

It’s unknown how many babies are born with this condition worldwide. Interesting fact: It seems to be most common in Finland, where about 1 in 60,000 newborns can’t digest lactose. (Note that this is still pretty rare!)

The cause of this deficiency is a mutation of the LCT gene, which essentially instructs the body to produce the enzyme needed to digest lactose. This is an inherited condition, so babies inherit this gene mutation from both of their parents.

Developmental lactase deficiency

Some premature infants are born with a developmental lactase deficiency. This is a temporary intolerance that occurs in infants born before their small intestines are fully developed (generally, before 34 weeks gestation).

Also, some babies develop a temporary lactose intolerance after a viral illness, like gastroenteritis.

If your baby has signs of a lactose intolerance, don’t diagnose the condition yourself. Talk to your pediatrician. They’ll have more experience distinguishing between a lactose intolerance and a milk allergy.

Since a lactose intolerance is uncommon in infants, your doctor may refer you to an allergist to rule out a dairy allergy after also ruling out other common digestive issues.

The allergist may expose your baby’s skin to a small amount of milk protein, and then monitor their skin for an allergic reaction.

If your baby doesn’t have a milk allergy, your doctor may take a stool sample to check the acidity of their poop. Low acidity can be a sign of lactose malabsorption, and traces of glucose is evidence of undigested lactose.

Low acidity can be a sign of lactose malabsorption, and traces of glucose is evidence of undigested lactose.

Your doctor may also suggest removing lactose from their diet for 1 to 2 weeks to see if their digestive symptoms improve.

If diagnostic testing confirms a lactose intolerance, don’t immediately panic and stop breastfeeding. Whether you’re able to continue breastfeeding depends on the type of lactase deficiency.

For example, if your baby develops a lactose intolerance after a viral illness, the general recommendation is to continue breastfeeding. Breast milk can give their immune system a boost and help heal their gut.

If your infant has developmental lactase deficiency due to a premature birth, this condition only lasts a few weeks or months. So your baby may eventually drink milk-based formula or breast milk with no problem, although you’ll need to use lactose-free infant formula in the meantime.

But breastfeeding isn’t an option if your baby has a congenital lactase deficiency. The lactose in your breast milk can cause severe diarrhea and lead to dehydration and electrolyte loss. You’ll need to feed your baby with lactose-free infant formula.

The lactose in your breast milk can cause severe diarrhea and lead to dehydration and electrolyte loss. You’ll need to feed your baby with lactose-free infant formula.

Lactose intolerance following a viral illness or a premature birth is usually temporary — hooray! — and your baby’s body may eventually produce normal levels of the lactase enzyme to digest the sugar in milk.

But a congenital lactase deficiency is a lifelong condition, and you’ll need to modify your little one’s diet to avoid symptoms.

The good news is that lactose-free infant formulas contain nutrients — like calcium, vitamin D, and vitamin A — that babies receive from drinking lactose-based products. (And there’s never been a better time to grow up with lactose intolerance, as so many people are going dairy-free by choice.)

Foods to avoid

When you buy food for your baby, read labels and don’t purchase items containing lactose (whey, milk by-products, nonfat dry milk powder, dry milk solids, and curds).

Popular baby-friendly foods that may contain lactose include:

- yogurt

- prepared oatmeal

- formula

- instant mashed potatoes

- pancakes

- biscuits (including teething biscuits)

- cookies

- pudding

- sherbet

- ice cream

- cheese

Q: If my baby’s lactose intolerant and I’m breastfeeding, will it help if I quit eating lactose or will I still have to switch to a dairy-free formula?

A: Taking dairy or lactose out of your diet will not reduce the lactose in your breast milk. Breast milk naturally contains lactose.

Depending on the type of lactose intolerance your baby has, you may have to switch to a lactose-free formula. Some lactose intolerance is a short-term situation and will resolve over time. Congenital lactose intolerance will not go away and your child will have to remain lactose free for their whole life.

Please make all changes to your baby’s diet with the assistance of your healthcare provider.

— Carissa Stephens, RN

Answers represent the opinions of our medical experts. All content is strictly informational and should not be considered medical advice.

Was this helpful?

An inability to digest the sugar in milk can be uncomfortable for a baby, but diarrhea, gas, and stomach pain don’t always mean lactose intolerance. These symptoms could indicate a milk allergy, general digestive problems common in the first 3 months of life, or something else.

If you believe that your baby has trouble digesting milk, see your pediatrician for a diagnosis. And take heart — while a diagnosis may seem daunting at first, it’ll put you well on your way to having a happier, less fussy baby.

Lactose intolerance | Symptoms, complications, diagnosis and treatment

People with lactose intolerance are unable to fully digest the lactose in milk. As a result, they develop diarrhea, gas, and bloating after eating or consuming dairy products. The condition, also called lactose malabsorption, is usually harmless, but its symptoms can be uncomfortable. Most people with lactose intolerance can manage the condition without giving up all dairy products.

The condition, also called lactose malabsorption, is usually harmless, but its symptoms can be uncomfortable. Most people with lactose intolerance can manage the condition without giving up all dairy products.

Lactase deficiency, an enzyme produced in the small intestine, is usually responsible for lactose intolerance. Many people have low lactase levels but can digest dairy products without problems. If you are actually lactose intolerant, lactase deficiency leads to symptoms after you eat dairy products.

Signs and symptoms of lactose intolerance usually begin 30 minutes to two hours after eating or drinking foods containing lactose. General signs and symptoms include:

- Diarrhea

- Nausea and sometimes vomiting

- Abdominal cramps

- Inflate

- Gases

Make an appointment with your doctor if you often experience symptoms of lactose intolerance after eating dairy products, especially if you are worried about getting enough calcium.

Causes

Lactose intolerance occurs when the small intestine does not produce enough enzyme (lactase) to digest milk sugar (lactose).

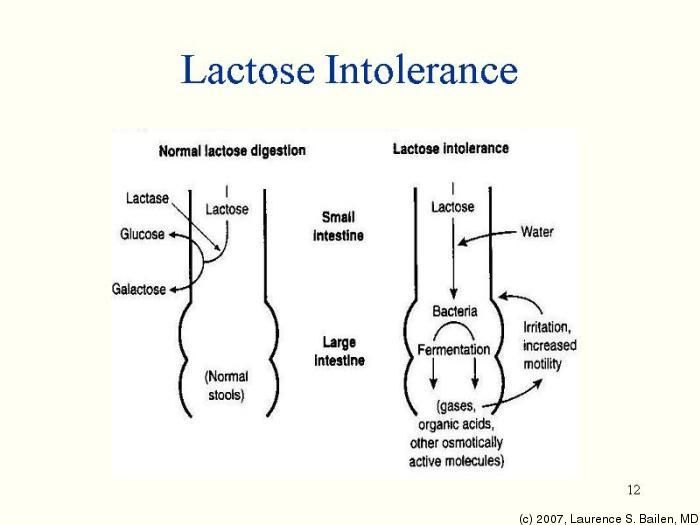

Normally, lactase converts milk sugar into two simple sugars, glucose and galactose, which are absorbed into the bloodstream through the intestinal lining.

If you are lactase deficient, the lactose in food moves to the large intestine instead of being processed and absorbed. In the colon, normal bacteria interact with undigested lactose, causing the signs and symptoms of lactose intolerance.

There are three types of lactose intolerance. Various factors cause lactase deficiency underlying each type.

Primary lactose intolerance

This is the most common type of lactose intolerance. People with primary lactose intolerance begin their lives by producing large amounts of lactase, a must for babies who get all their nutrients from milk. As children replace milk with other foods, their lactase production usually decreases but remains high enough to digest the amount of dairy in a normal adult diet.

As children replace milk with other foods, their lactase production usually decreases but remains high enough to digest the amount of dairy in a normal adult diet.

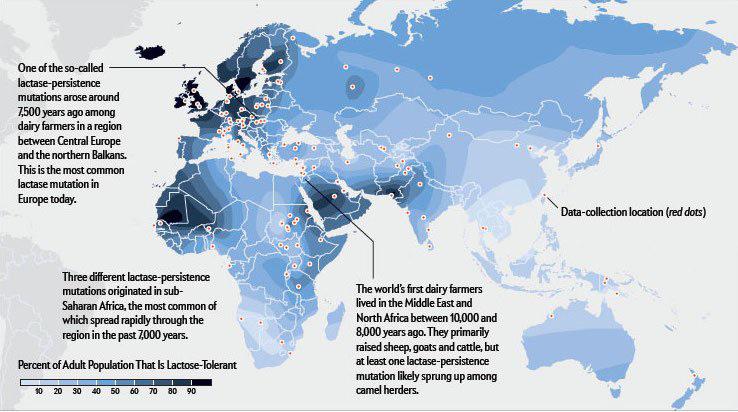

In primary lactose intolerance, lactase production drops dramatically, making it difficult for adults to digest dairy products. Primary lactose intolerance is genetically determined, which occurs in a significant proportion of people of African, Asian, or Hispanic ancestry. This condition is also common among Mediterranean or South European ancestry.

Secondary lactose intolerance

This form of lactose intolerance occurs when the small intestine reduces its production of lactase after illness, injury, or surgery involving the small intestine. Diseases associated with secondary lactose intolerance include celiac disease, bacterial overgrowth, and Crohn's disease. Treating the underlying disorder can restore lactase levels and improve symptoms and signs, although this may take some time.

Congenital or developing lactose intolerance

This disorder is passed from generation to generation in a form of inheritance called autosomal recessive. Premature babies may also be lactose intolerant due to insufficient lactase levels.

Factors that may make you or your child more likely to become lactose intolerant, include:

- Growing up. Lactose intolerance usually appears in adulthood. This disease is rare in children and young children.

- Ethnos. Lactose intolerance is most common in African, Asian, Hispanic, and American Indian people.

- Premature birth. Babies born prematurely may have low lactase levels because the small intestine does not develop lactase-producing cells until late in the third trimester.

- Diseases affecting the small intestine. Small intestinal problems that can cause lactose intolerance include bacterial overgrowth, celiac disease, and Crohn's disease.

- Some treatments for cancer. If you've had radiation therapy for abdominal cancer or intestinal complications from chemotherapy, you're at increased risk of lactose intolerance.

Lactase deficiency - articles from the specialists of the clinic "Mother and Child"

what is it

The main food of babies is milk (breast or formula). It contains many different nutrients (proteins, fats, carbohydrates), which, with the help of special digestive enzymes, are broken down into simple components and digested. But in young children, the gastrointestinal tract is still immature, there are few enzymes in it, others are not at all or they are not yet working at full capacity. When the baby grows up, there will be more enzymes, the digestive system will mature, but for now there may be various problems with it.

All milk (women's, cow's, goat's, artificial mixtures) and dairy products contain the carbohydrate lactose, also called "milk sugar". In order for lactose to be absorbed, the lactase enzyme must break it down, but if the child has little or no lactase enzyme, then lactose is not broken down and remains in the intestine. As a result, there is always a large amount of milk sugar in the intestines, which begins to ferment, and where there is fermentation, conditionally pathogenic flora actively reproduces. What we feel during fermentation: intestinal motility increases (it rumbles), plus gas formation increases (the stomach swells). But in an adult, this is usually a one-time situation due to some inaccuracies in nutrition, and it quickly passes. But in babies, everything is different, especially since they lack the enzyme not once, but constantly. What it looks like: The milk sugar lactose retains water, hence loose stools. In the child’s stomach, “rumbles and boils”, colic begins, the stool becomes frothy, greens, mucus and even blood may appear in it. If at first the stool was liquid, then constipation appears, and all this changes in a circle: yesterday there was diarrhea, today and tomorrow there is no stool at all, the day after tomorrow it is liquid again.

And the most unpleasant thing is endless colic and endless crying, there is no rest for both the parents themselves and the baby. Mom at some point notices that the baby is crying just after feeding, and then a variety of advice falls upon her. “Your milk is bad, better give the mixture,” says the beloved mother-in-law. “Only breasts and nothing else!” - advise breastfeeding gurus. As a result, the mother tries one thing or the other, but neither breast milk nor artificial mixture gives relief to the child. Colic, crying and problems with the stomach and stool continue. The parents are in a panic because they don't understand what is going on. In fact, this is a typical picture of bright lactase deficiency (LN), or insufficient production of the lactase enzyme.

various reasons

There are several types of lactase deficiency, and it is with them that confusion arises.

Congenital lactase deficiency is a genetic and very rare disease (one case in several thousand newborns), it is difficult to confuse it with something, since it is very difficult. The diagnosis is made in the maternity hospital or in the first days after birth, the child does not have lactase at all, he quickly loses weight, he is immediately started to be fed intravenously or through a tube. Some experts (but not doctors) on breastfeeding read once that congenital lactase deficiency is an extremely rare disease, and that’s all - they further began to assure young mothers: “In fact, LN is extremely rare, you don’t have it, you don’t need to listen to doctors ", etc. Yes, congenital LN is a rare disease, but the key word here is "congenital", and there are other types of lactase deficiency.

Transient lactase deficiency in infants . And this is exactly the condition that occurs very often. The baby was born, and so far he still has little lactase enzyme, plus little normal intestinal microflora. Hence the colic, and loose stools, and mucus, and greenery, and crying, and the nerves of the parents. After a while, the child's digestive system will fully mature, all enzymes will begin to work actively, the intestines will be populated with what is needed, and "lactase deficiency" will disappear. Therefore, such a LN is called "transient", that is, temporary, or passing. It passes for someone a month after birth, for someone longer - after six to seven months, and there are children in whom lactase deficiency completely disappears only by the year.

Secondary lactase deficiency. This condition appears if a person has had some kind of intestinal infection, and it does not matter whether it is an adult or a baby. For some time after the illness, the child does not tolerate milk (any), and then with proper nutrition and sometimes even without treatment, everything quickly passes.

Lactase deficiency in adults. There are people in whom the lactase enzyme begins to be lacking only in adulthood, this happens for various reasons: for some, lactase ceases to be produced in the right amount after some kind of illness, for other people, the activity of this enzyme simply fades over time by itself. yourself. As a result, at some age, a person begins to tolerate milk and dairy products poorly, although before that everything was fine. The symptoms are the same as in babies: he drank milk and after that the stomach rumbles, boils, and the stool is liquid. Sooner or later, a person realizes that milk is not his product, and simply stops drinking it in its pure form.

what to do

If there is transient lactase deficiency, then what to do with it? First you need to understand if it exists at all. Why does the child have problems with the stomach, stool, why does he cry all the time? Is it neurology, common colic, errors in the mother's diet, an inappropriate mixture (if the baby is bottle-fed), improper breastfeeding technique, lactase deficiency, or a reaction to the weather? It can be difficult to figure it out right away, but if the tests show that there is lactase deficiency, then it is most likely in it. Now what to do next - treat it, wait for the enzymes to mature, or something else? Firstly, everything here will depend on how much the enzyme is lacking and, therefore, on how much LN worries the child and parents. Some children lack the enzyme quite a bit, so their colic is mild and children cry quite normally. Plus, the violation of the stool is also not very bright: there are a couple of times a slightly liquefied stool, but that's all. In other children, the lack of lactase is more pronounced, the child does not cry, but simply yells after each feeding, if at first he gained weight well, then after two months the increase is minimal, problems with stools begin in parallel (day - constipation, day - diarrhea), stool sometimes green, sometimes with mucus. Atopic dermatitis appears on the skin (the skin is the first to react to problems with the gastrointestinal tract). Parents have no rest day or night: the baby cries - he is fed - he cries again, they try to calm him down in other ways. But nothing helps. Mom and dad are in a panic, and no one has the strength anymore.

If parents see that the child may have signs of lactase deficiency, that he needs help, first of all, you need to look for a good doctor. Only an experienced pediatrician will be able to figure out why the baby has colic or green stools, what the numbers in the tests say, and what is the norm for one baby and the pathology for another. And of course, it is not necessary to cancel breastfeeding and immediately prescribe lactose-free or low-lactose artificial mixtures (even as a supplement). By itself, milk sugar lactose is very necessary for a child, when lactose is broken down, its components (glucose and galactose) go to the development of the brain, retina, for the life of normal intestinal microflora. So do not completely eliminate this sugar, you need to help it break down. With a strongly pronounced LN, the missing enzyme is given before each feeding (it has long been learned to produce and it is sold in pharmacies), with a dim clinic, its dose can be reduced. And it is also possible that there is lactase deficiency (even according to tests), but it does not need to be treated, there are almost no symptoms.

But what cannot be done is to listen to non-specialists who deny either lactase deficiency itself or its treatment. They see the cause of all problems with the child's stomach and stool either in the wrong technique of breastfeeding, or partially admit that there is immaturity of the enzyme, but this is natural and will pass by itself. Yes, for some, LN is expressed easily and will pass quickly, but what about those parents whose child yells day and night, covered with a crust from atopic dermatitis and stopped gaining weight? Wait for the time to come and the enzymes to mature? Alas, with pronounced lactase deficiency (even if transient), enterocytes (intestinal cells) often suffer, so it is simply necessary to help such a child.

If you see that your baby has signs of lactase deficiency, look for a doctor who is committed to maintaining breastfeeding and has extensive experience. He will definitely help to find out why the baby is crying, why he has a stomach ache or has problems with stool. And then the life of the parents and the child will return to normal.

"Transient" (temporary) lactase deficiency in someone passes a month after birth, in someone longer - after six to seven months, and there are children in whom lactase deficiency completely disappears only by the age of one

If the tests show that there is a lactase deficiency, then the matter is most likely in it.