Overactive thyroid and pregnancy

Thyroid Disease & Pregnancy | NIDDK

On this page:

- What role do thyroid hormones play in pregnancy?

- Hyperthyroidism in Pregnancy

- Hypothyroidism in Pregnancy

- Postpartum Thyroiditis

- Is it safe to breastfeed while I’m taking beta-blockers, thyroid hormone, or antithyroid medicines?

- Thyroid Disease and Eating During Pregnancy

- Clinical Trials

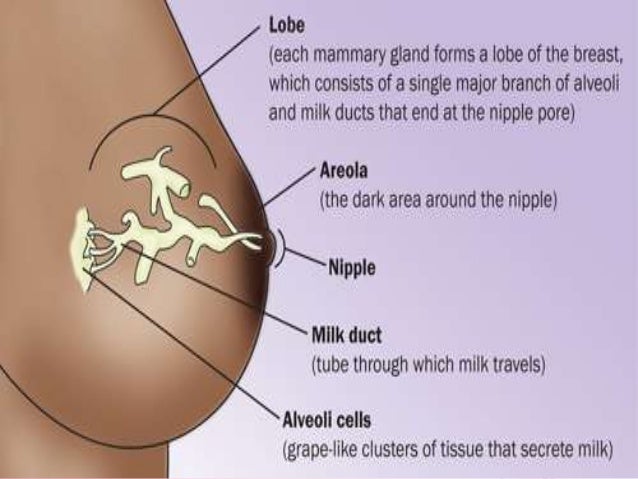

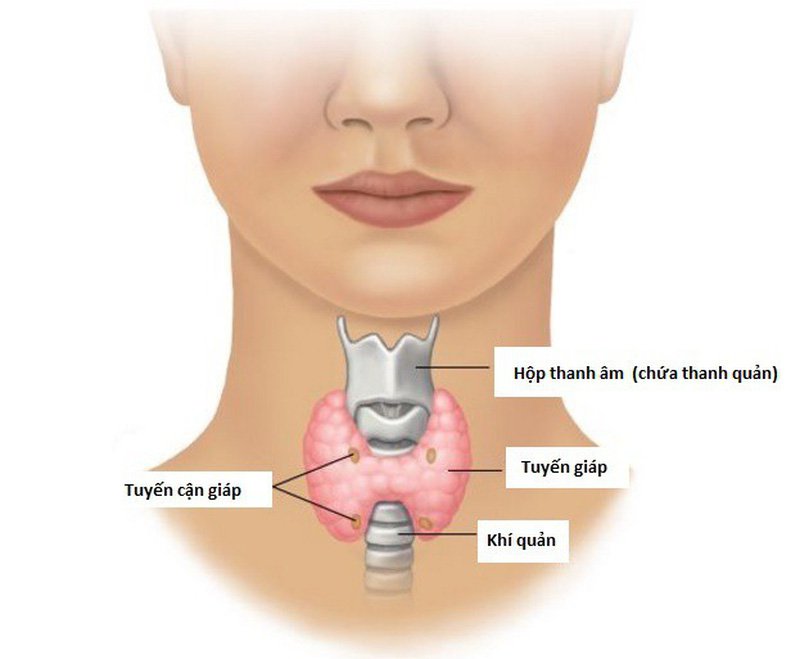

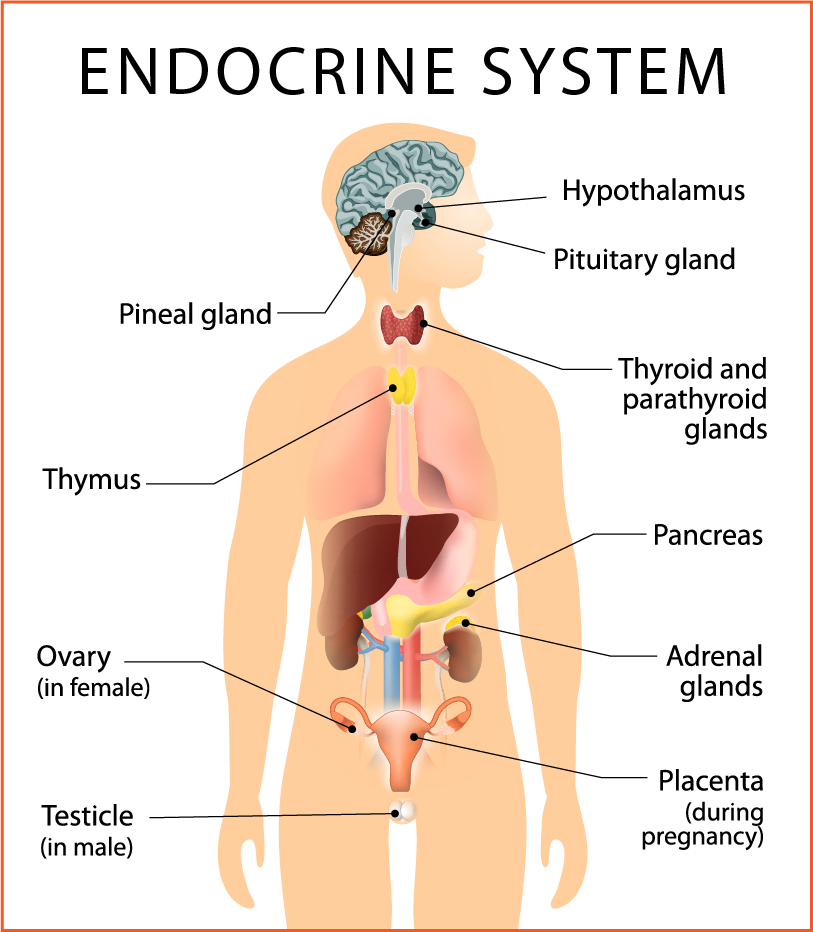

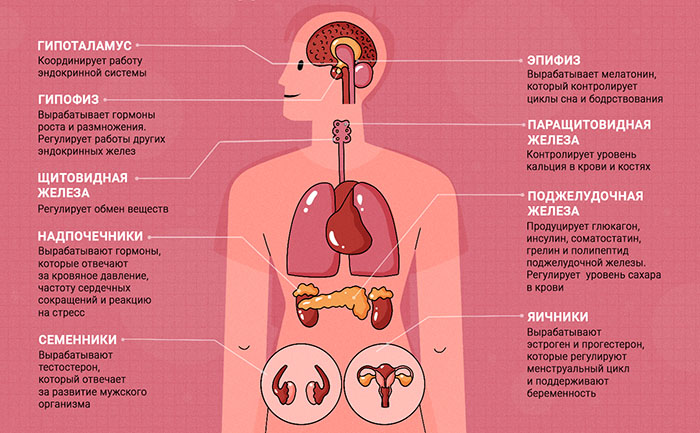

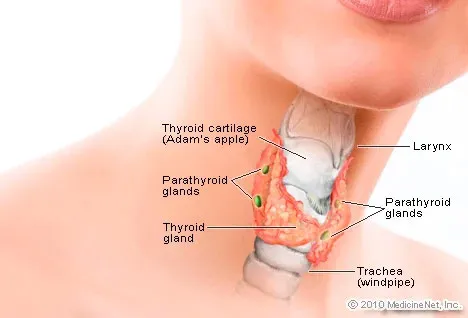

Thyroid disease is a group of disorders that affects the thyroid gland. The thyroid is a small, butterfly-shaped gland in the front of your neck that makes thyroid hormones. Thyroid hormones control how your body uses energy, so they affect the way nearly every organ in your body works—even the way your heart beats.

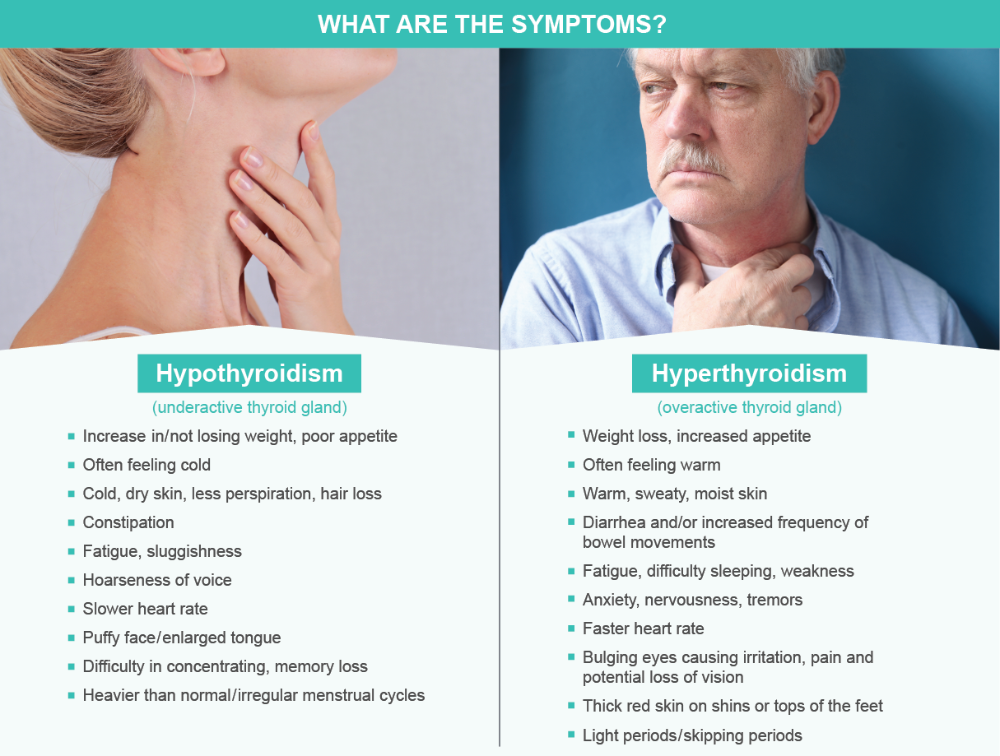

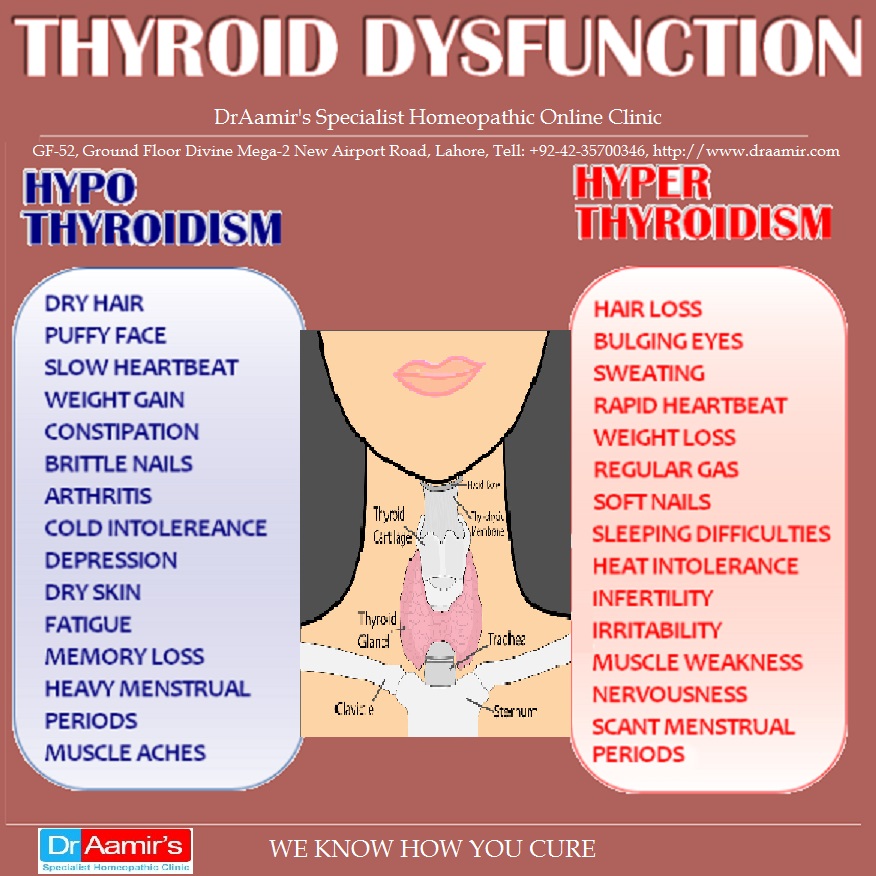

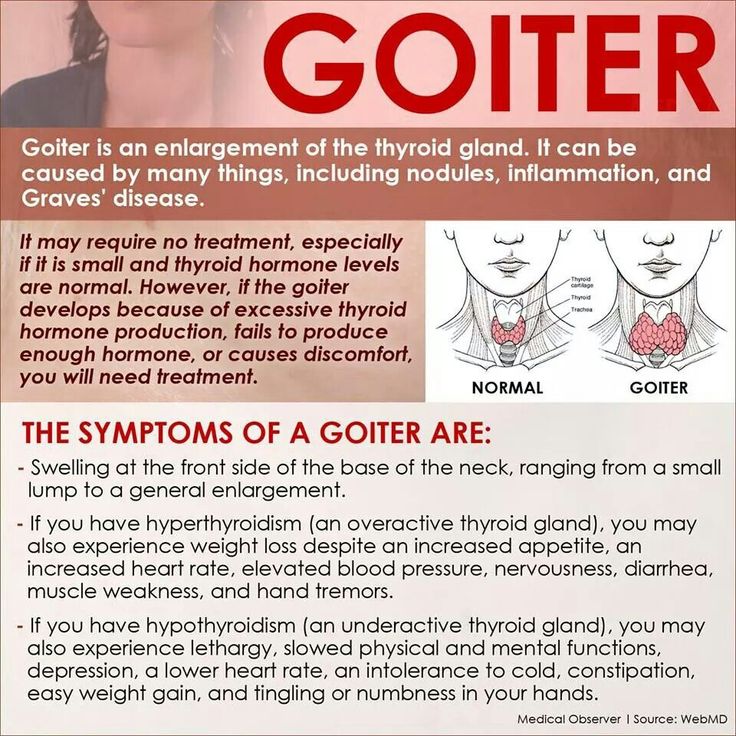

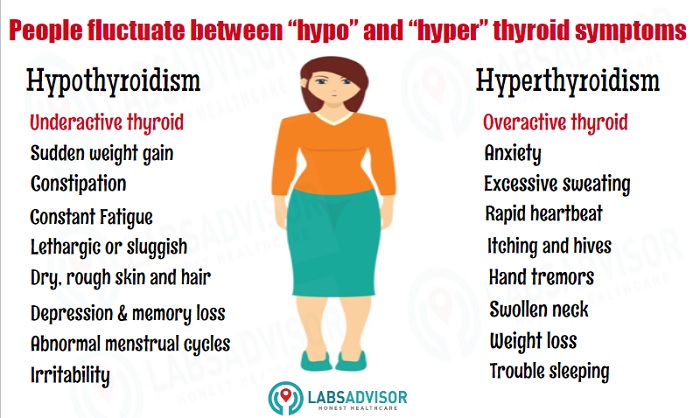

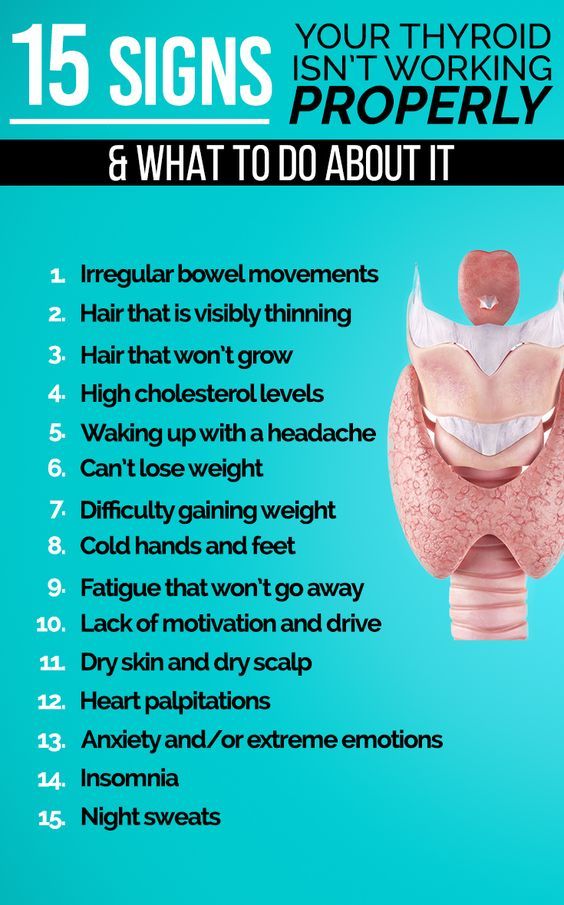

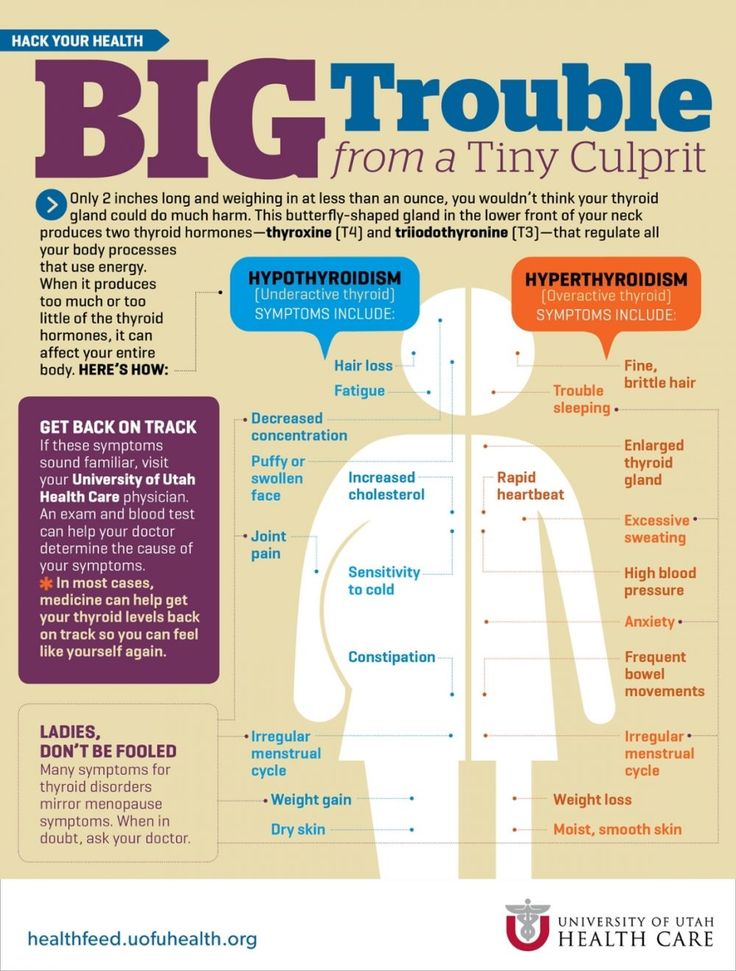

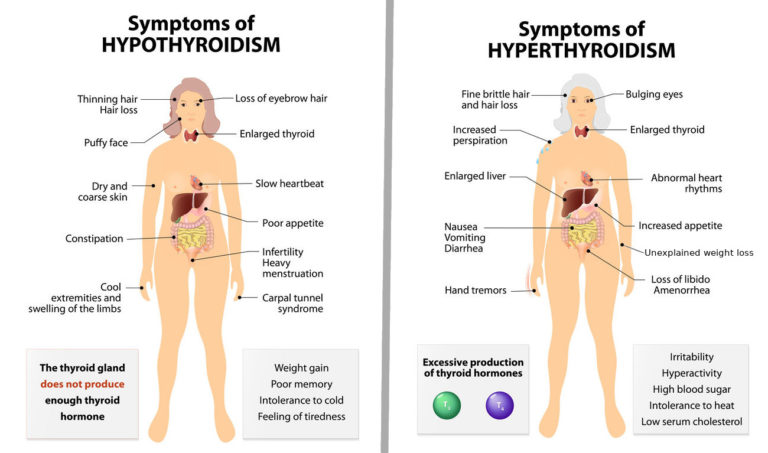

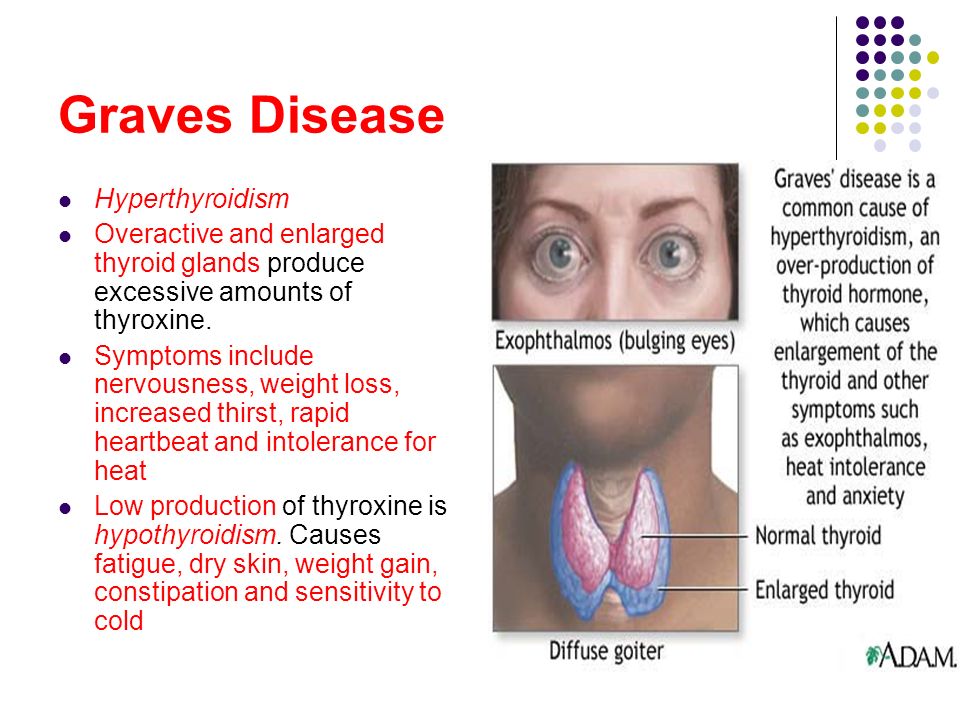

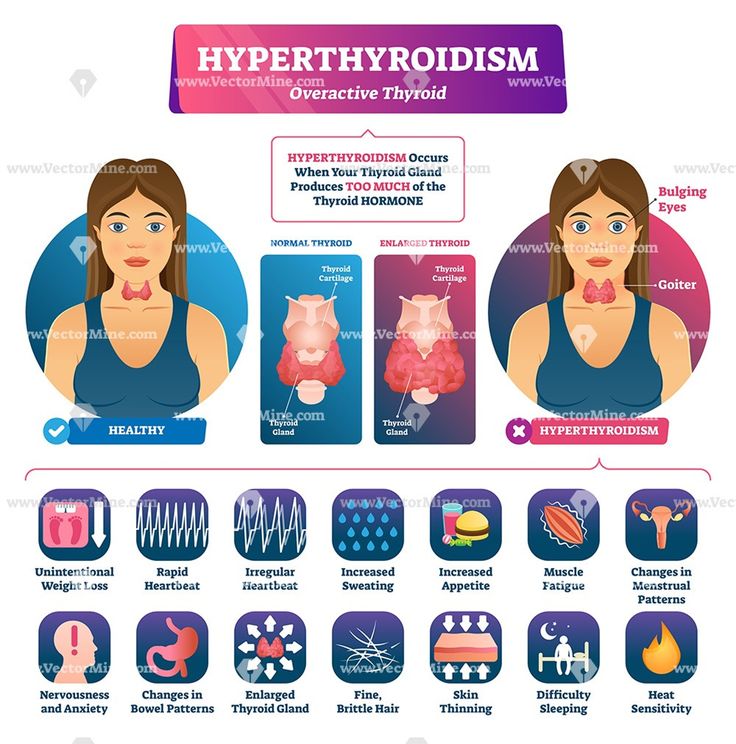

The thyroid is a small gland in your neck that makes thyroid hormones.Sometimes the thyroid makes too much or too little of these hormones. Too much thyroid hormone is called hyperthyroidism and can cause many of your body’s functions to speed up. “Hyper” means the thyroid is overactive. Learn more about hyperthyroidism in pregnancy. Too little thyroid hormone is called hypothyroidism and can cause many of your body’s functions to slow down. “Hypo” means the thyroid is underactive. Learn more about hypothyroidism in pregnancy.

If you have thyroid problems, you can still have a healthy pregnancy and protect your baby’s health by having regular thyroid function tests and taking any medicines that your doctor prescribes.

What role do thyroid hormones play in pregnancy?

Thyroid hormones are crucial for normal development of your baby’s brain and nervous system. During the first trimester—the first 3 months of pregnancy—your baby depends on your supply of thyroid hormone, which comes through the placenta. At around 12 weeks, your baby’s thyroid starts to work on its own, but it doesn’t make enough thyroid hormone until 18 to 20 weeks of pregnancy.

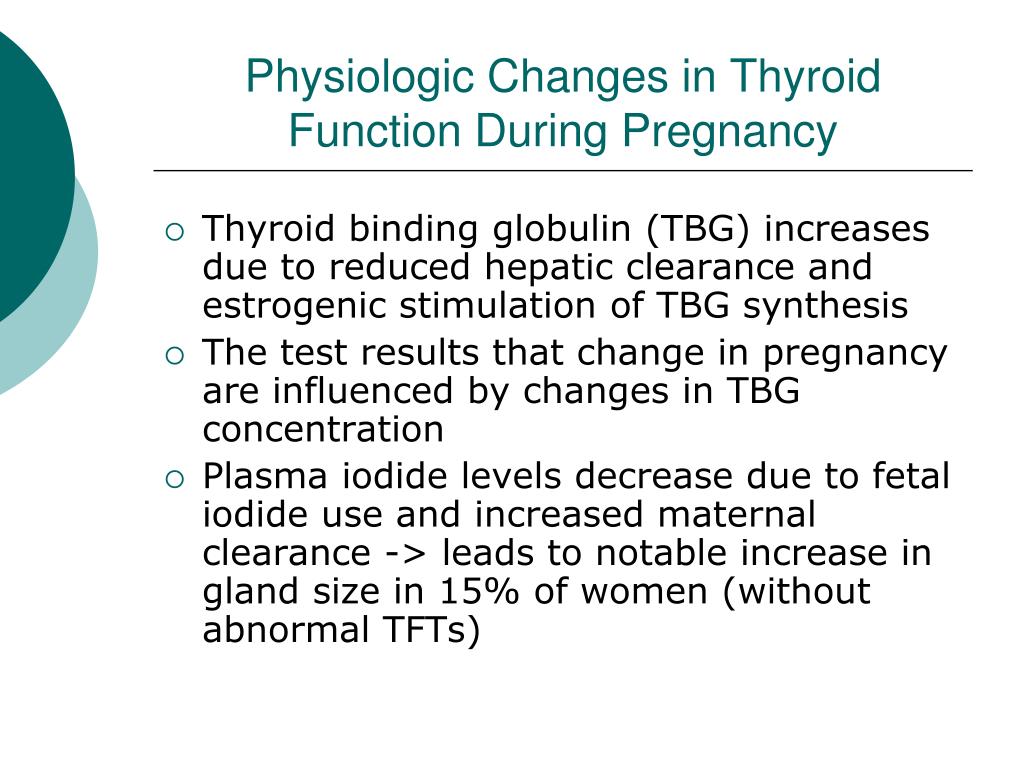

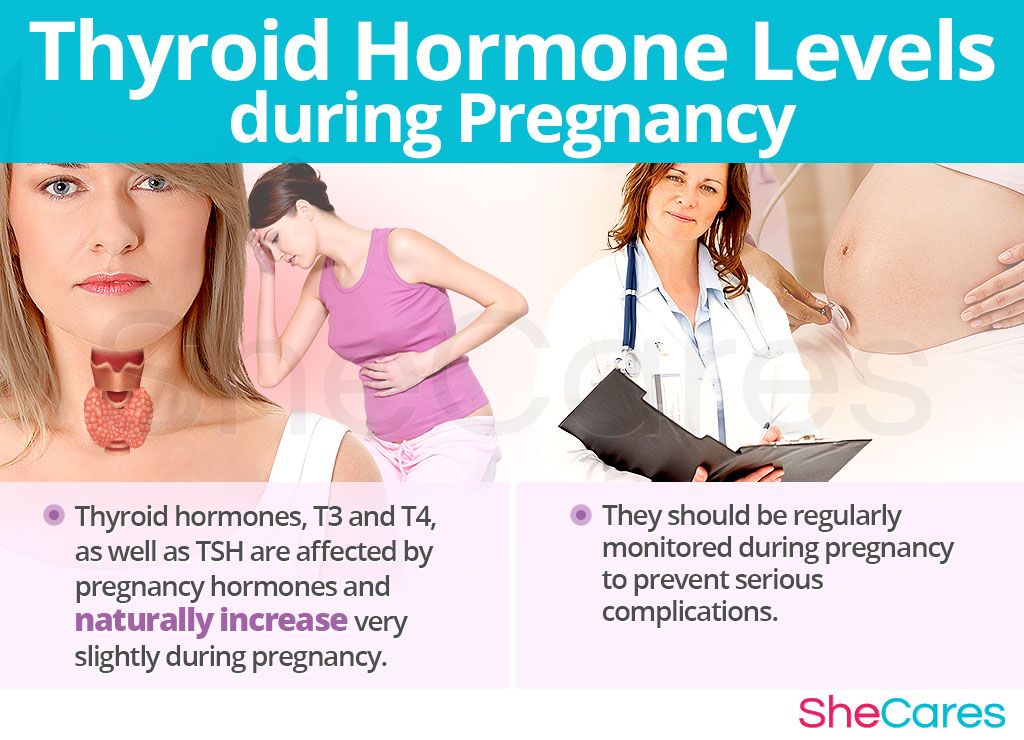

Two pregnancy-related hormones—human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and estrogen—cause higher measured thyroid hormone levels in your blood. The thyroid enlarges slightly in healthy women during pregnancy, but usually not enough for a health care professional to feel during a physical exam.

The thyroid enlarges slightly in healthy women during pregnancy, but usually not enough for a health care professional to feel during a physical exam.

Thyroid problems can be hard to diagnose in pregnancy due to higher levels of thyroid hormones and other symptoms that occur in both pregnancy and thyroid disorders. Some symptoms of hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism are easier to spot and may prompt your doctor to test you for these thyroid diseases.

Another type of thyroid disease, postpartum thyroiditis, can occur after your baby is born.

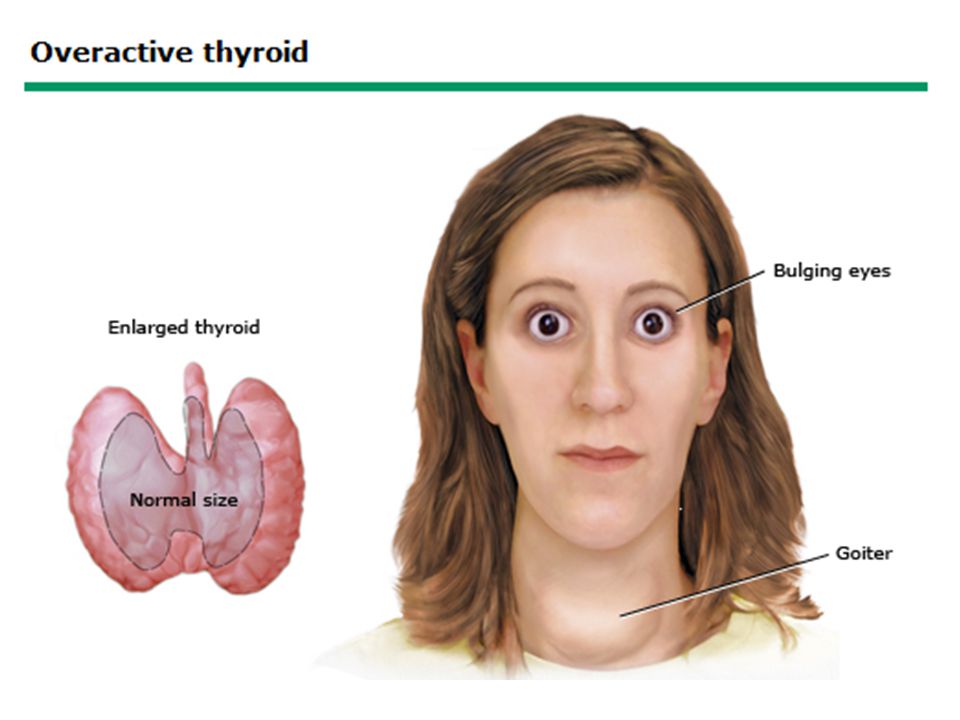

Hyperthyroidism in Pregnancy

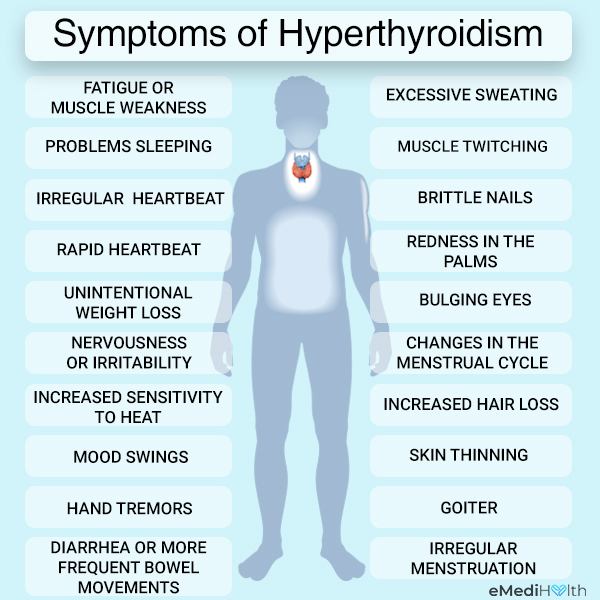

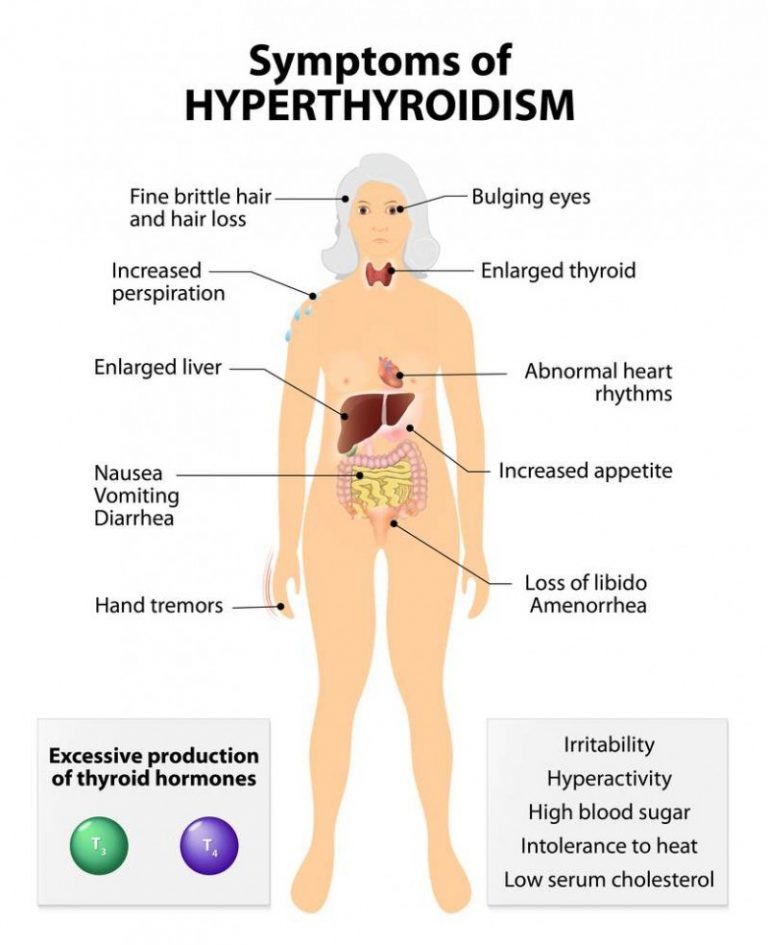

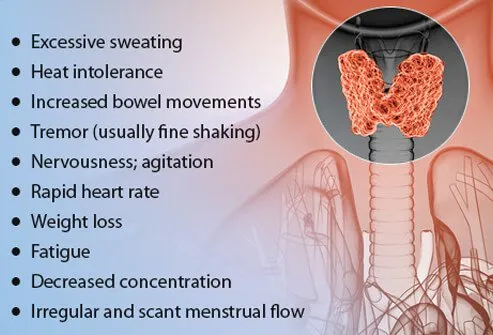

What are the symptoms of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy?

Some signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism often occur in normal pregnancies, including faster heart rate, trouble dealing with heat, and tiredness.

Other signs and symptoms can suggest hyperthyroidism:

- fast and irregular heartbeat

- shaky hands

- unexplained weight loss or failure to have normal pregnancy weight gain

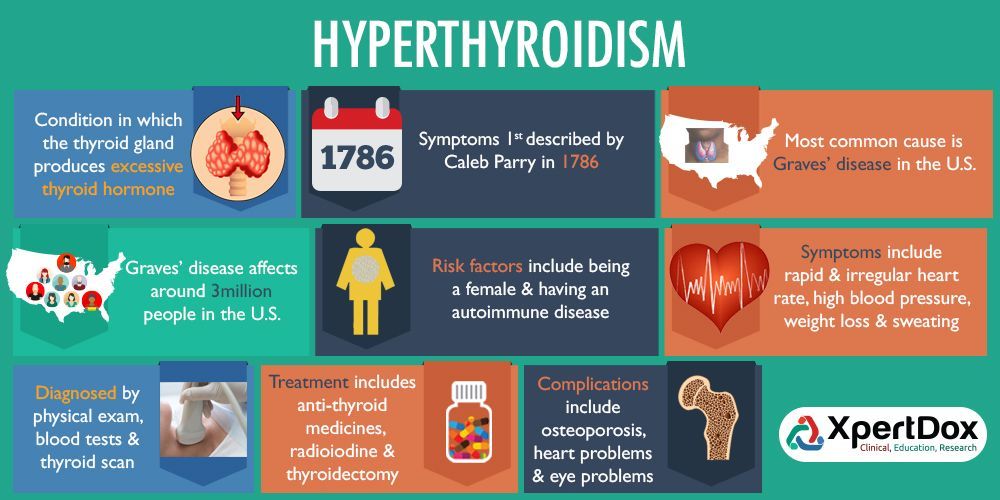

What causes hyperthyroidism in pregnancy?

Hyperthyroidism in pregnancy is usually caused by Graves’ disease and occurs in 1 to 4 of every 1,000 pregnancies in the United States. 1 Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder. With this disease, your immune system makes antibodies that cause the thyroid to make too much thyroid hormone. This antibody is called thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin, or TSI.

1 Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder. With this disease, your immune system makes antibodies that cause the thyroid to make too much thyroid hormone. This antibody is called thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin, or TSI.

Graves’ disease may first appear during pregnancy. However, if you already have Graves’ disease, your symptoms could improve in your second and third trimesters. Some parts of your immune system are less active later in pregnancy so your immune system makes less TSI. This may be why symptoms improve. Graves’ disease often gets worse again in the first few months after your baby is born, when TSI levels go up again. If you have Graves’ disease, your doctor will most likely test your thyroid function monthly throughout your pregnancy and may need to treat your hyperthyroidism.1 Thyroid hormone levels that are too high can harm your health and your baby’s.

If you have Graves’ disease, your doctor will most likely test your thyroid function monthly during your pregnancy.

Rarely, hyperthyroidism in pregnancy is linked to hyperemesis gravidarum—severe nausea and vomiting that can lead to weight loss and dehydration. Experts believe this severe nausea and vomiting is caused by high levels of hCG early in pregnancy. High hCG levels can cause the thyroid to make too much thyroid hormone. This type of hyperthyroidism usually goes away during the second half of pregnancy.

Less often, one or more nodules, or lumps in your thyroid, make too much thyroid hormone.

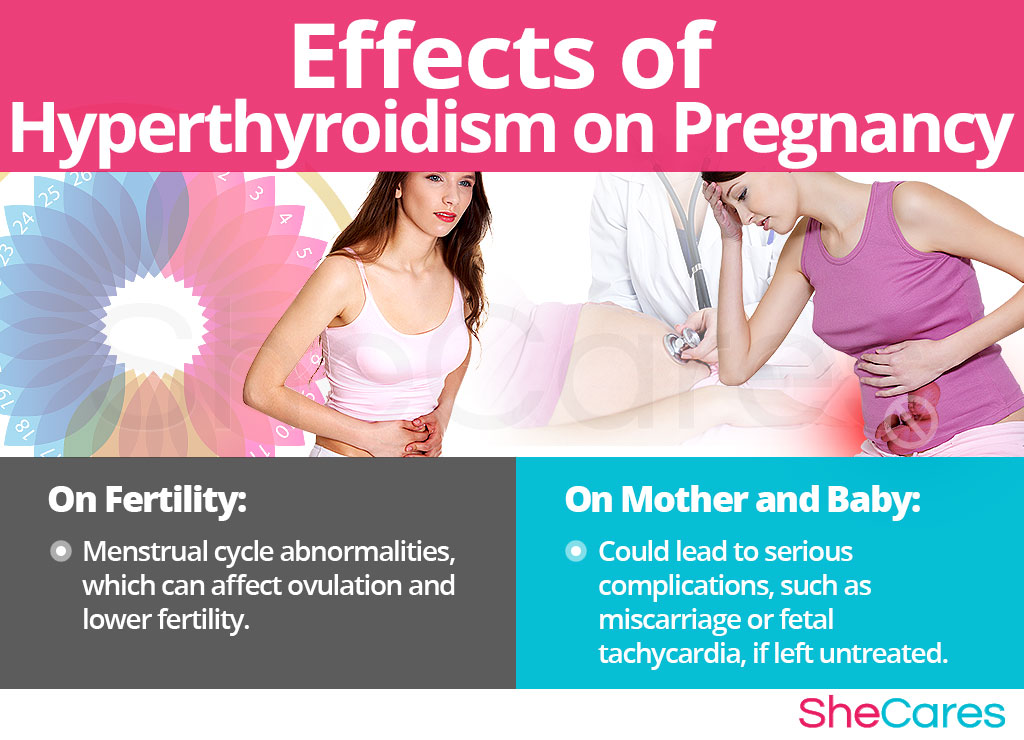

How can hyperthyroidism affect me and my baby?

Untreated hyperthyroidism during pregnancy can lead to

- miscarriage

- premature birth

- low birthweight

- preeclampsia—a dangerous rise in blood pressure in late pregnancy

- thyroid storm—a sudden, severe worsening of symptoms

- congestive heart failure

Rarely, Graves’ disease may also affect a baby’s thyroid, causing it to make too much thyroid hormone. Even if your hyperthyroidism was cured by radioactive iodine treatment to destroy thyroid cells or surgery to remove your thyroid, your body still makes the TSI antibody. When levels of this antibody are high, TSI may travel to your baby’s bloodstream. Just as TSI caused your own thyroid to make too much thyroid hormone, it can also cause your baby’s thyroid to make too much.

When levels of this antibody are high, TSI may travel to your baby’s bloodstream. Just as TSI caused your own thyroid to make too much thyroid hormone, it can also cause your baby’s thyroid to make too much.

Tell your doctor if you’ve had surgery or radioactive iodine treatment for Graves’ disease so he or she can check your TSI levels. If they are very high, your doctor will monitor your baby for thyroid-related problems later in your pregnancy.

Tell your doctor if you’ve had surgery or radioactive iodine treatment for Graves’ disease.An overactive thyroid in a newborn can lead to

- a fast heart rate, which can lead to heart failure

- early closing of the soft spot in the baby’s skull

- poor weight gain

- irritability

Sometimes an enlarged thyroid can press against your baby’s windpipe and make it hard for your baby to breathe. If you have Graves’ disease, your health care team should closely monitor you and your newborn.

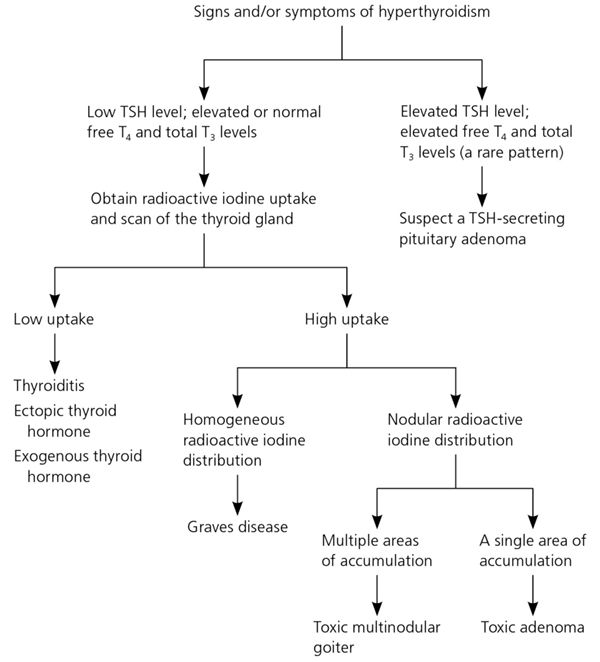

How do doctors diagnose hyperthyroidism in pregnancy?

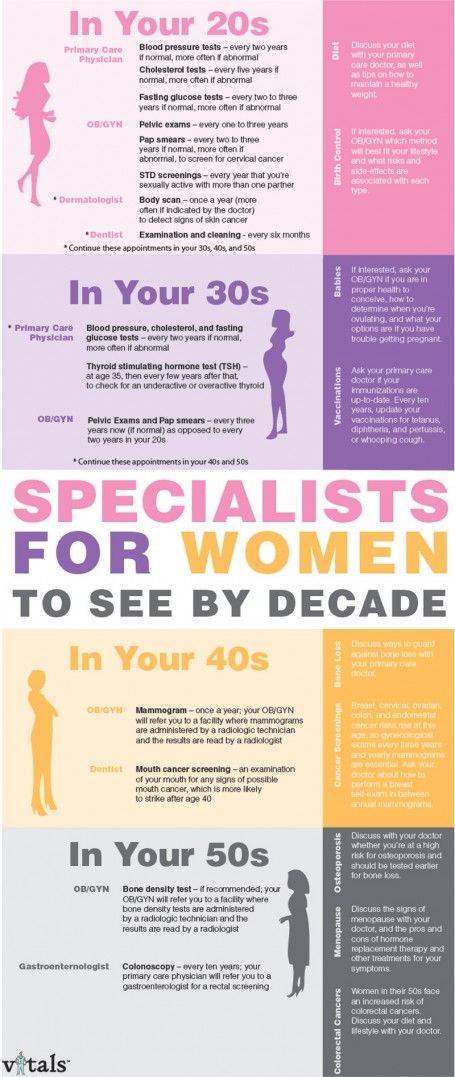

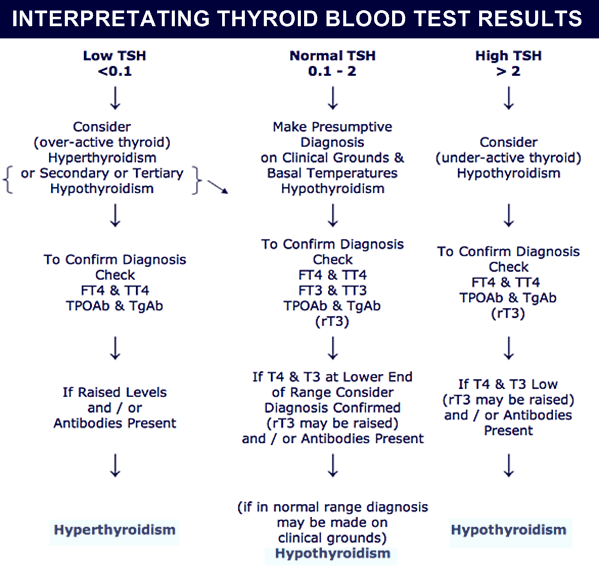

Your doctor will review your symptoms and do some blood tests to measure your thyroid hormone levels. Your doctor may also look for antibodies in your blood to see if Graves’ disease is causing your hyperthyroidism. Learn more about thyroid tests and what the results mean.

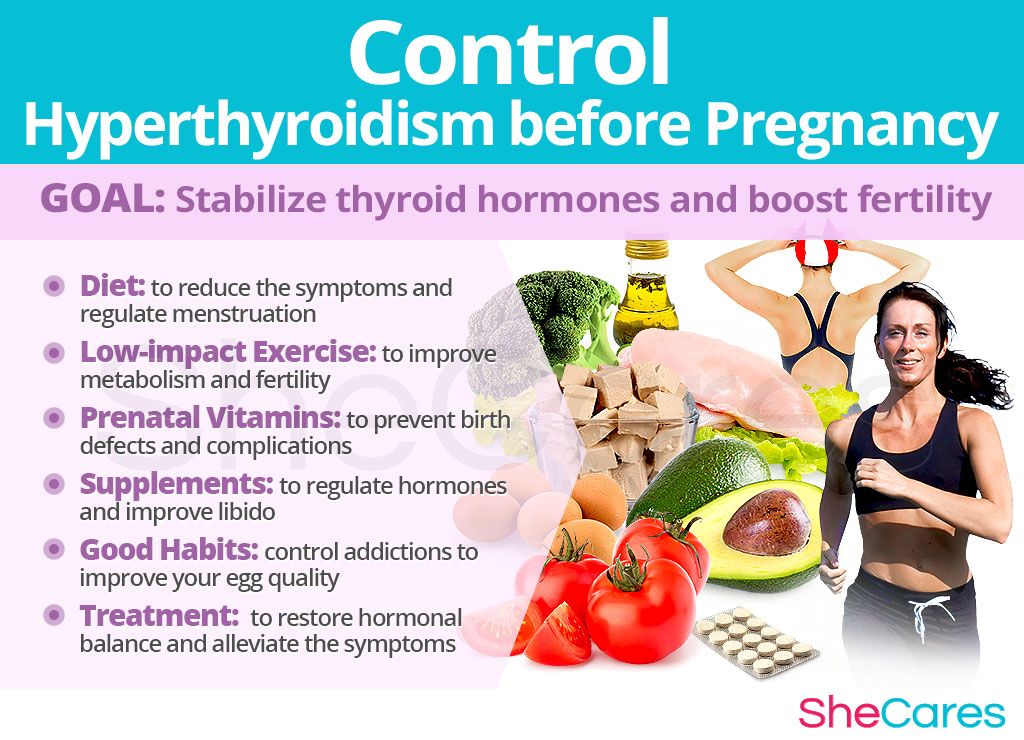

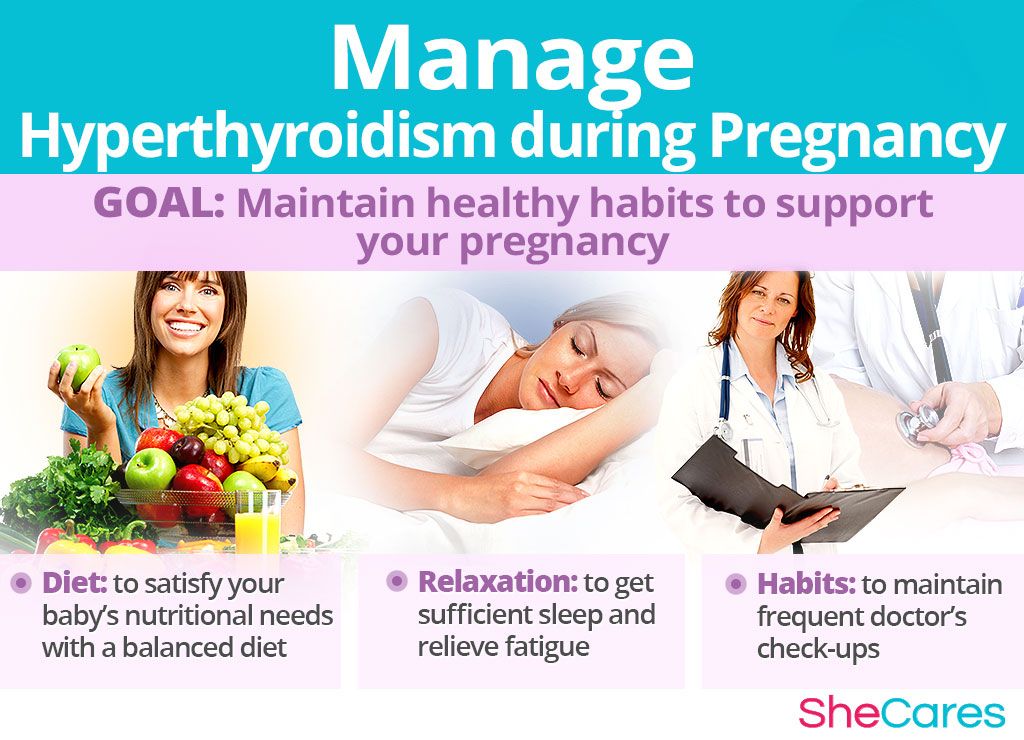

How do doctors treat hyperthyroidism during pregnancy?

If you have mild hyperthyroidism during pregnancy, you probably won’t need treatment. If your hyperthyroidism is linked to hyperemesis gravidarum, you only need treatment for vomiting and dehydration.

If your hyperthyroidism is more severe, your doctor may prescribe antithyroid medicines, which cause your thyroid to make less thyroid hormone. This treatment prevents too much of your thyroid hormone from getting into your baby’s bloodstream. You may want to see a specialist, such as an endocrinologist or expert in maternal-fetal medicine, who can carefully monitor your baby to make sure you’re getting the right dose.

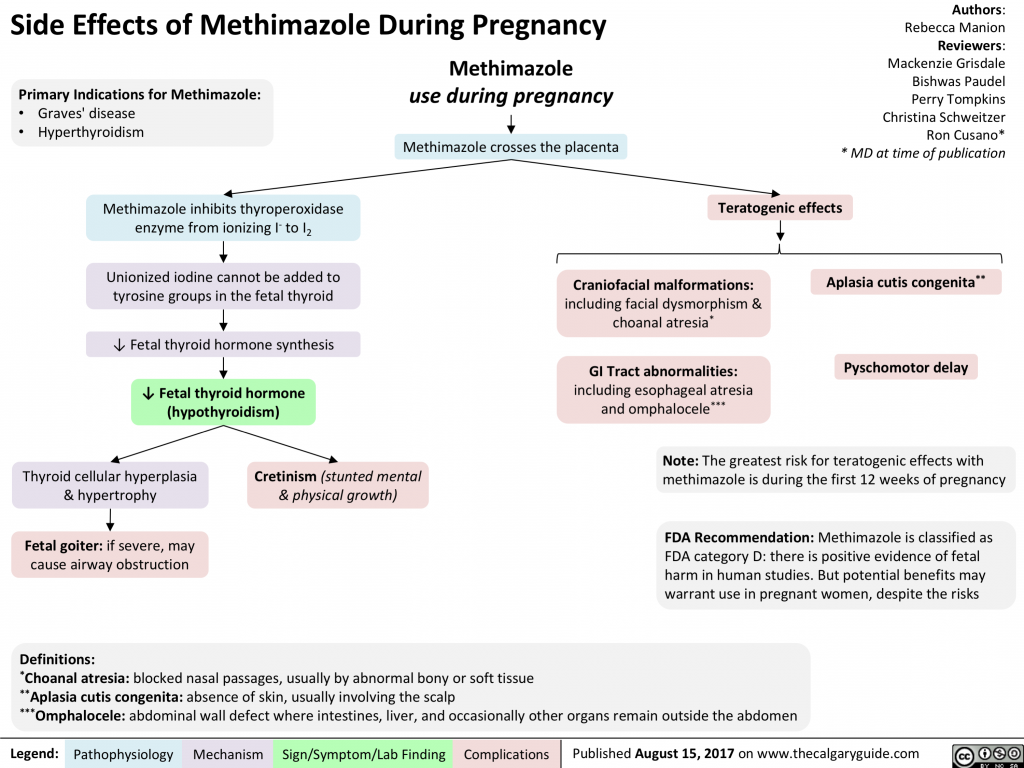

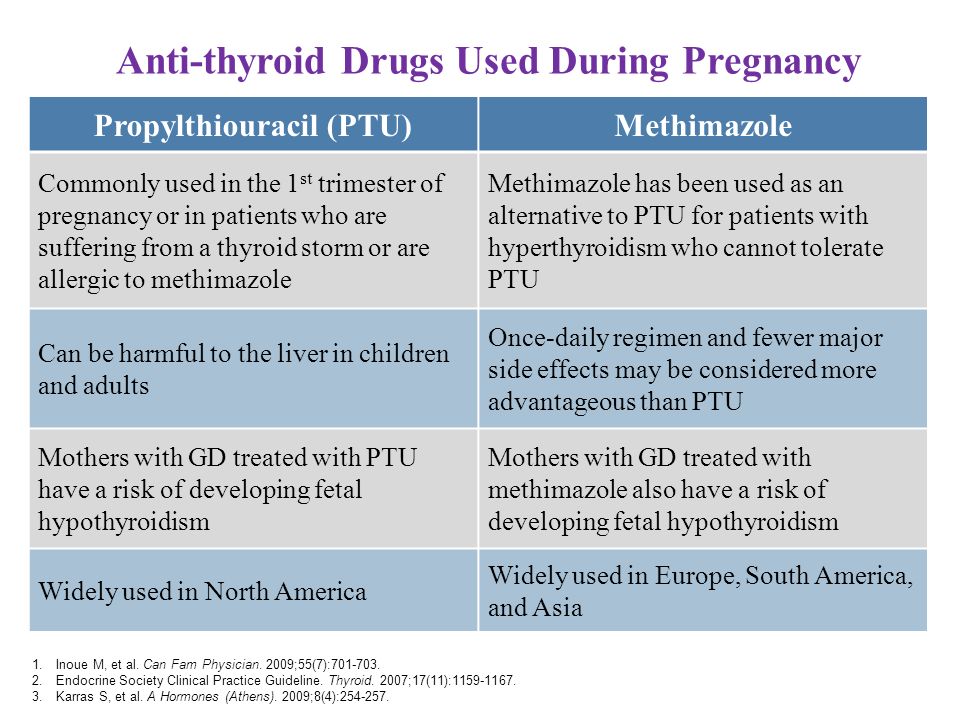

Doctors most often treat pregnant women with the antithyroid medicine propylthiouracil (PTU) during the first 3 months of pregnancy. Another type of antithyroid medicine, methimazole, is easier to take and has fewer side effects, but is slightly more likely to cause serious birth defects than PTU. Birth defects with either type of medicine are rare. Sometimes doctors switch to methimazole after the first trimester of pregnancy. Some women no longer need antithyroid medicine in the third trimester.

Small amounts of antithyroid medicine move into the baby’s bloodstream and lower the amount of thyroid hormone the baby makes. If you take antithyroid medicine, your doctor will prescribe the lowest possible dose to avoid hypothyroidism in your baby but enough to treat the high thyroid hormone levels that can also affect your baby.

Antithyroid medicines can cause side effects in some people, including

- allergic reactions such as rashes and itching

- rarely, a decrease in the number of white blood cells in the body, which can make it harder for your body to fight infection

- liver failure, in rare cases

Stop your antithyroid medicine and call your doctor right away if you develop any of these symptoms while taking antithyroid medicines:

- yellowing of your skin or the whites of your eyes, called jaundice

- dull pain in your abdomen

- constant sore throat

- fever

If you don’t hear back from your doctor the same day, you should go to the nearest emergency room.

You should also contact your doctor if any of these symptoms develop for the first time while you’re taking antithyroid medicines:

- increased tiredness or weakness

- loss of appetite

- skin rash or itching

- easy bruising

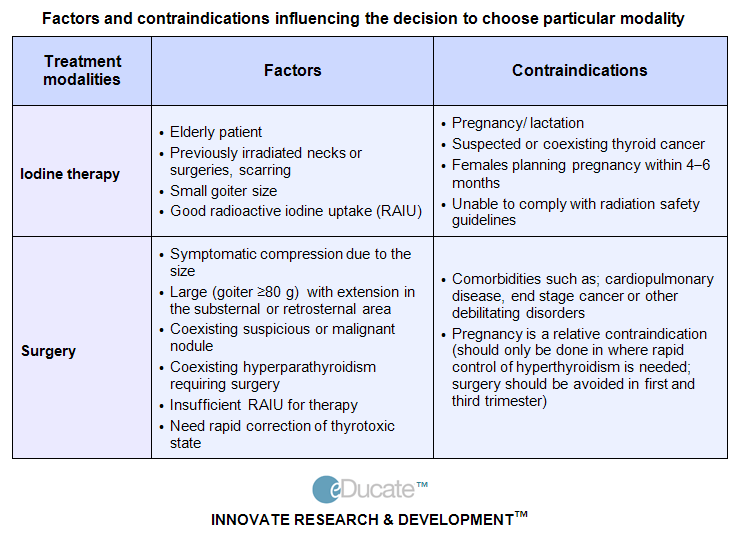

If you are allergic to or have severe side effects from antithyroid medicines, your doctor may consider surgery to remove part or most of your thyroid gland. The best time for thyroid surgery during pregnancy is in the second trimester.

Radioactive iodine treatment is not an option for pregnant women because it can damage the baby’s thyroid gland.

Hypothyroidism in Pregnancy

What are the symptoms of hypothyroidism in pregnancy?

Symptoms of an underactive thyroid are often the same for pregnant women as for other people with hypothyroidism. Symptoms include

- extreme tiredness

- trouble dealing with cold

- muscle cramps

- severe constipation

- problems with memory or concentration

Most cases of hypothyroidism in pregnancy are mild and may not have symptoms.

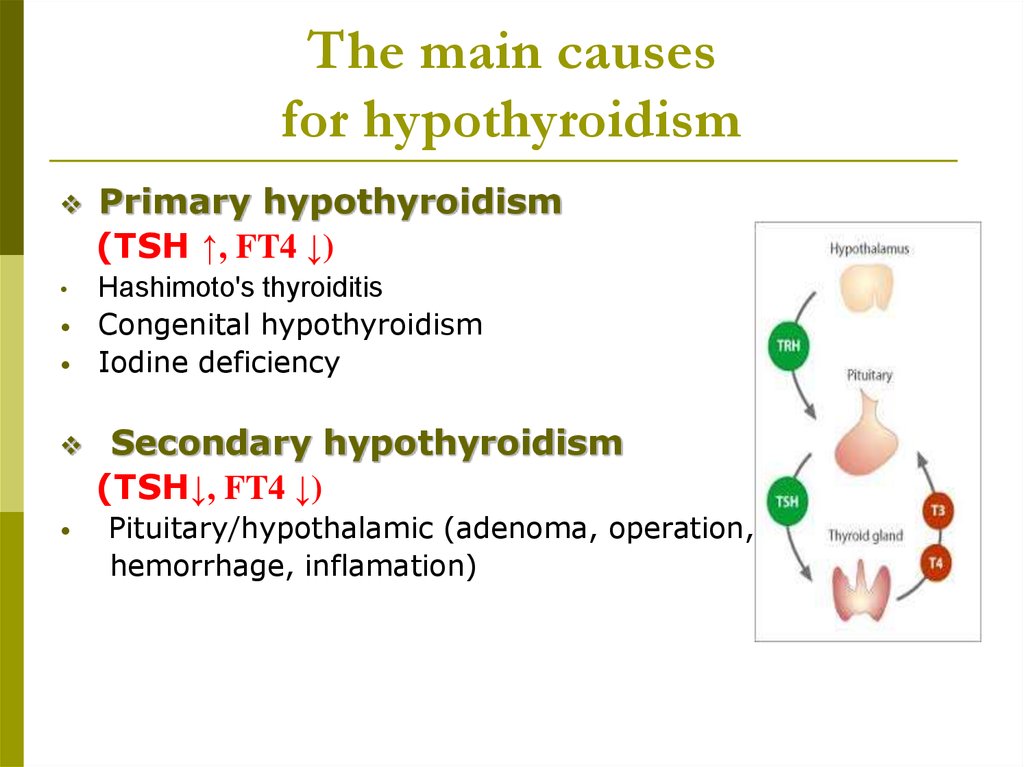

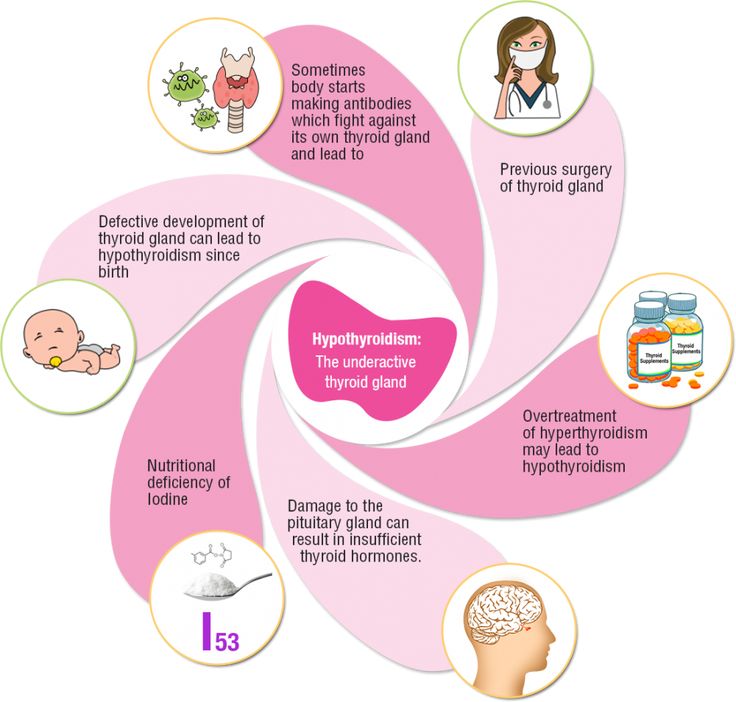

What causes hypothyroidism in pregnancy?

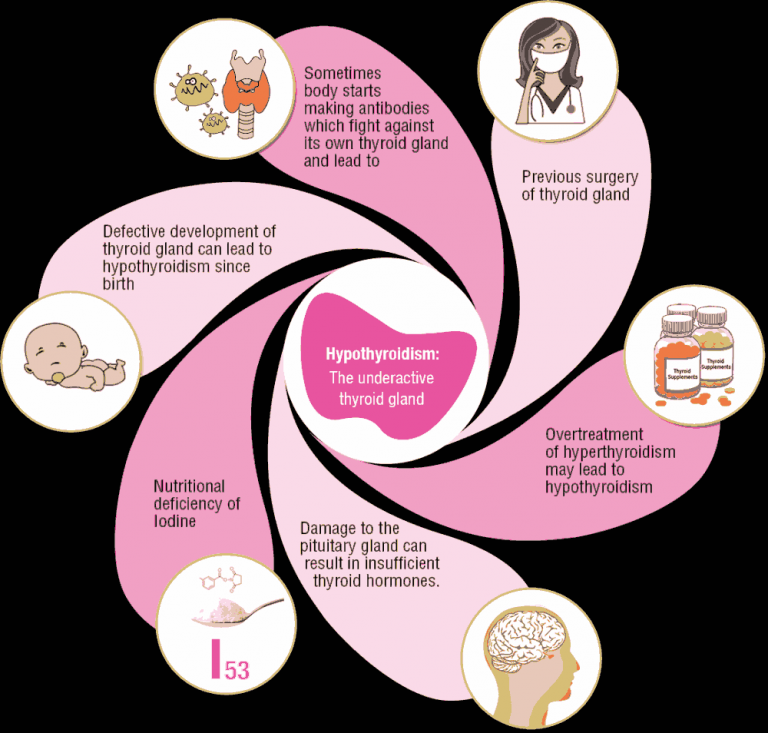

Hypothyroidism in pregnancy is usually caused by Hashimoto’s disease and occurs in 2 to 3 out of every 100 pregnancies.1 Hashimoto’s disease is an autoimmune disorder. In Hashimoto’s disease, the immune system makes antibodies that attack the thyroid, causing inflammation and damage that make it less able to make thyroid hormones.

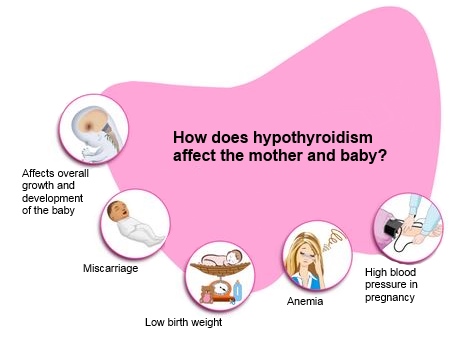

How can hypothyroidism affect me and my baby?

Untreated hypothyroidism during pregnancy can lead to

- preeclampsia—a dangerous rise in blood pressure in late pregnancy

- anemia

- miscarriage

- low birthweight

- stillbirth

- congestive heart failure, rarely

These problems occur most often with severe hypothyroidism.

Because thyroid hormones are so important to your baby’s brain and nervous system development, untreated hypothyroidism—especially during the first trimester—can cause low IQ and problems with normal development.

How do doctors diagnose hypothyroidism in pregnancy?

Your doctor will review your symptoms and do some blood tests to measure your thyroid hormone levels. Your doctor may also look for certain antibodies in your blood to see if Hashimoto’s disease is causing your hypothyroidism. Learn more about thyroid tests and what the results mean.

How do doctors treat hypothyroidism during pregnancy?

Treatment for hypothyroidism involves replacing the hormone that your own thyroid can no longer make. Your doctor will most likely prescribe levothyroxine, a thyroid hormone medicine that is the same as T4, one of the hormones the thyroid normally makes. Levothyroxine is safe for your baby and especially important until your baby can make his or her own thyroid hormone.

Your thyroid makes a second type of hormone, T3. Early in pregnancy, T3 can’t enter your baby’s brain like T4 can. Instead, any T3 that your baby’s brain needs is made from T4. T3 is included in a lot of thyroid medicines made with animal thyroid, such as Armour Thyroid, but is not useful for your baby’s brain development. These medicines contain too much T3 and not enough T4, and should not be used during pregnancy. Experts recommend only using levothyroxine (T4) while you’re pregnant.

These medicines contain too much T3 and not enough T4, and should not be used during pregnancy. Experts recommend only using levothyroxine (T4) while you’re pregnant.

Some women with subclinical hypothyroidism—a mild form of the disease with no clear symptoms—may not need treatment.

Your doctor may prescribe levothyroxine to treat your hypothyroidism.If you had hypothyroidism before you became pregnant and are taking levothyroxine, you will probably need to increase your dose. Most thyroid specialists recommend taking two extra doses of thyroid medicine per week, starting right away. Contact your doctor as soon as you know you’re pregnant.

Your doctor will most likely test your thyroid hormone levels every 4 to 6 weeks for the first half of your pregnancy, and at least once after 30 weeks.1 You may need to adjust your dose a few times.

Postpartum Thyroiditis

What is postpartum thyroiditis?

Postpartum thyroiditis is an inflammation of the thyroid that affects about 1 in 20 women during the first year after giving birth1 and is more common in women with type 1 diabetes. The inflammation causes stored thyroid hormone to leak out of your thyroid gland. At first, the leakage raises the hormone levels in your blood, leading to hyperthyroidism. The hyperthyroidism may last up to 3 months. After that, some damage to your thyroid may cause it to become underactive. Your hypothyroidism may last up to a year after your baby is born. However, in some women, hypothyroidism doesn’t go away.

The inflammation causes stored thyroid hormone to leak out of your thyroid gland. At first, the leakage raises the hormone levels in your blood, leading to hyperthyroidism. The hyperthyroidism may last up to 3 months. After that, some damage to your thyroid may cause it to become underactive. Your hypothyroidism may last up to a year after your baby is born. However, in some women, hypothyroidism doesn’t go away.

Not all women who have postpartum thyroiditis go through both phases. Some only go through the hyperthyroid phase, and some only the hypothyroid phase.

What are the symptoms of postpartum thyroiditis?

The hyperthyroid phase often has no symptoms—or only mild ones. Symptoms may include irritability, trouble dealing with heat, tiredness, trouble sleeping, and fast heartbeat.

Symptoms of the hypothyroid phase may be mistaken for the “baby blues”—the tiredness and moodiness that sometimes occur after the baby is born. Symptoms of hypothyroidism may also include trouble dealing with cold; dry skin; trouble concentrating; and tingling in your hands, arms, feet, or legs. If these symptoms occur in the first few months after your baby is born or you develop postpartum depression, talk with your doctor as soon as possible.

If these symptoms occur in the first few months after your baby is born or you develop postpartum depression, talk with your doctor as soon as possible.

What causes postpartum thyroiditis?

Postpartum thyroiditis is an autoimmune condition similar to Hashimoto’s disease. If you have postpartum thyroiditis, you may have already had a mild form of autoimmune thyroiditis that flares up after you give birth.

Postpartum thyroiditis may last up to a year after your baby is born.How do doctors diagnose postpartum thyroiditis?

If you have symptoms of postpartum thyroiditis, your doctor will order blood tests to check your thyroid hormone levels.

How do doctors treat postpartum thyroiditis?

The hyperthyroid stage of postpartum thyroiditis rarely needs treatment. If your symptoms are bothering you, your doctor may prescribe a beta-blocker, a medicine that slows your heart rate. Antithyroid medicines are not useful in postpartum thyroiditis, but if you have Grave’s disease, it may worsen after your baby is born and you may need antithyroid medicines.

You’re more likely to have symptoms during the hypothyroid stage. Your doctor may prescribe thyroid hormone medicine to help with your symptoms. If your hypothyroidism doesn’t go away, you will need to take thyroid hormone medicine for the rest of your life.

Is it safe to breastfeed while I’m taking beta-blockers, thyroid hormone, or antithyroid medicines?

Certain beta-blockers are safe to use while you’re breastfeeding because only a small amount shows up in breast milk. The lowest possible dose to relieve your symptoms is best. Only a small amount of thyroid hormone medicine reaches your baby through breast milk, so it’s safe to take while you’re breastfeeding. However, in the case of antithyroid drugs, your doctor will most likely limit your dose to no more than 20 milligrams (mg) of methimazole or, less commonly, 400 mg of PTU.

Thyroid Disease and Eating During Pregnancy

What should I eat during pregnancy to help keep my thyroid and my baby’s thyroid working well?

Because the thyroid uses iodine to make thyroid hormone, iodine is an important mineral for you while you’re pregnant. During pregnancy, your baby gets iodine from your diet. You’ll need more iodine when you’re pregnant—about 250 micrograms a day.1 Good sources of iodine are dairy foods, seafood, eggs, meat, poultry, and iodized salt—salt with added iodine. Experts recommend taking a prenatal vitamin with 150 micrograms of iodine to make sure you’re getting enough, especially if you don’t use iodized salt.1 You also need more iodine while you’re breastfeeding since your baby gets iodine from breast milk. However, too much iodine from supplements such as seaweed can cause thyroid problems. Talk with your doctor about an eating plan that’s right for you and what supplements you should take. Learn more about a healthy diet and nutrition during pregnancy.

During pregnancy, your baby gets iodine from your diet. You’ll need more iodine when you’re pregnant—about 250 micrograms a day.1 Good sources of iodine are dairy foods, seafood, eggs, meat, poultry, and iodized salt—salt with added iodine. Experts recommend taking a prenatal vitamin with 150 micrograms of iodine to make sure you’re getting enough, especially if you don’t use iodized salt.1 You also need more iodine while you’re breastfeeding since your baby gets iodine from breast milk. However, too much iodine from supplements such as seaweed can cause thyroid problems. Talk with your doctor about an eating plan that’s right for you and what supplements you should take. Learn more about a healthy diet and nutrition during pregnancy.

Clinical Trials

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and other components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conduct and support research into many diseases and conditions.

What are clinical trials, and are they right for you?

Clinical trials are part of clinical research and at the heart of all medical advances. Clinical trials look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease. Researchers also use clinical trials to look at other aspects of care, such as improving the quality of life for people with chronic illnesses. Find out if clinical trials are right for you.

What clinical trials are open?

Clinical trials that are currently open and are recruiting can be viewed at www.ClinicalTrials.gov.

References

Hyperthyroidism in Pregnancy | American Thyroid Association

WHAT ARE THE NORMAL CHANGES IN THYROID FUNCTION ASSOCIATED WITH PREGNANCY?

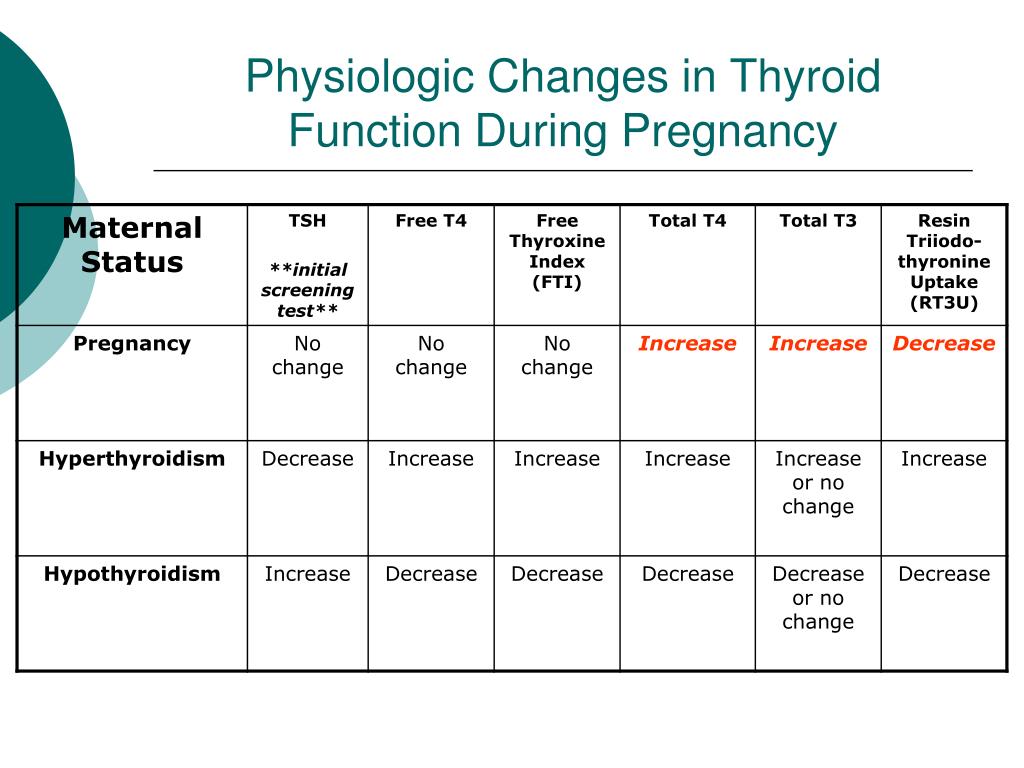

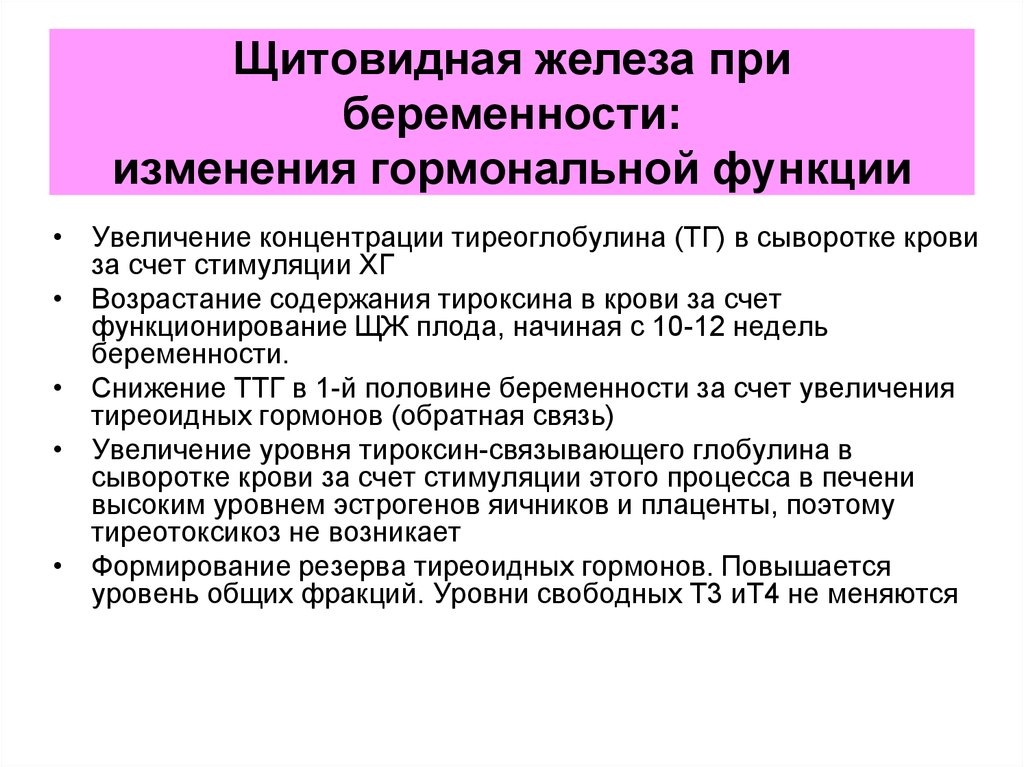

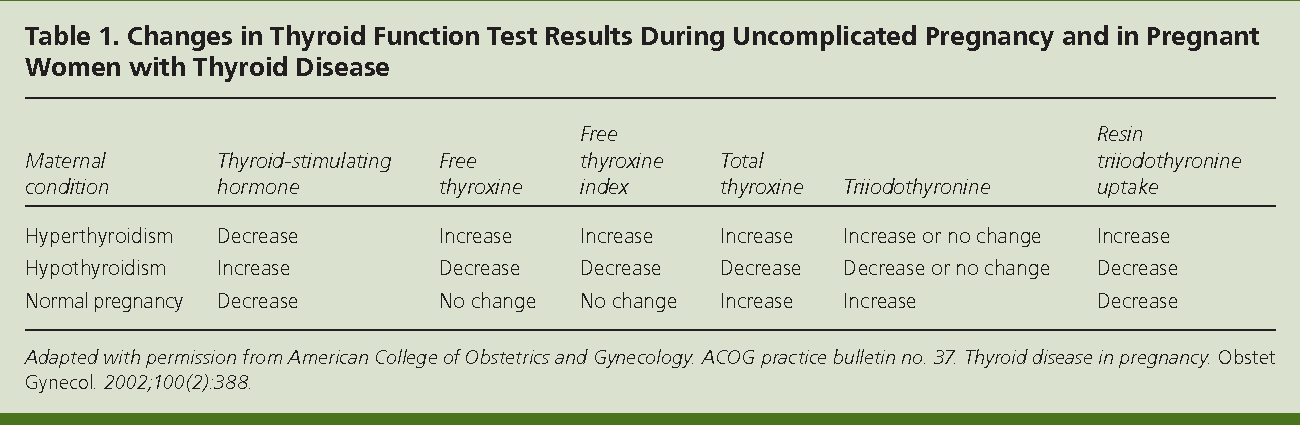

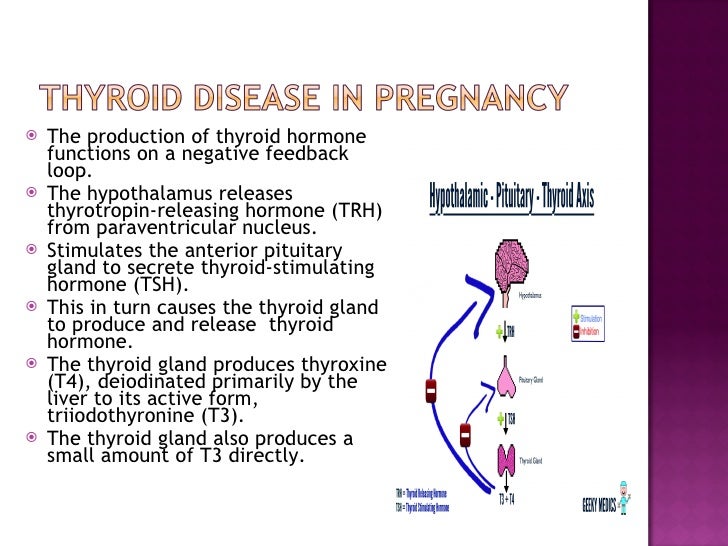

HORMONE CHANGES. A normal pregnancy results in a number of important physiological and hormonal changes that alter thyroid function. These changes mean that laboratory tests of thyroid function must be interpreted with caution during pregnancy. Thyroid function tests change during pregnancy due to the influence of two main hormones: human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), the hormone that is measured in the pregnancy test and estrogen, the main female hormone. HCG can weakly turn on the thyroid and the high circulating hCG levels in the first trimester may result in a slightly low TSH. When this occurs, the TSH will be slightly decreased in the first trimester and then return to normal throughout the duration of pregnancy. Estrogen increases the amount of thyroid hormone binding proteins in the serum which increases the total thyroid hormone levels in the blood since >99% of the thyroid hormones in the blood are bound to these proteins. However, measurements of “Free” hormone (that are not bound to protein, representing the active form of the hormone) usually remain normal. The thyroid is functioning normally if the TSH and Free T4 remain in the trimester-specific normal ranges throughout pregnancy.

HCG can weakly turn on the thyroid and the high circulating hCG levels in the first trimester may result in a slightly low TSH. When this occurs, the TSH will be slightly decreased in the first trimester and then return to normal throughout the duration of pregnancy. Estrogen increases the amount of thyroid hormone binding proteins in the serum which increases the total thyroid hormone levels in the blood since >99% of the thyroid hormones in the blood are bound to these proteins. However, measurements of “Free” hormone (that are not bound to protein, representing the active form of the hormone) usually remain normal. The thyroid is functioning normally if the TSH and Free T4 remain in the trimester-specific normal ranges throughout pregnancy.

SIZE CHANGES. The thyroid gland can increase in size during pregnancy (enlarged thyroid = goiter). However, pregnancy-associated goiters occur much more frequently in iodine-deficient areas of the world. It is relatively uncommon in the United States. If very sensitive imaging techniques (ultrasound) are used, it is possible to detect an increase in thyroid volume in some women. This is usually only a 10-15% increase in size and is not typically apparent on physical examination by the physician. However, sometimes a significant goiter may develop and prompt the doctor to measure tests of thyroid function.

If very sensitive imaging techniques (ultrasound) are used, it is possible to detect an increase in thyroid volume in some women. This is usually only a 10-15% increase in size and is not typically apparent on physical examination by the physician. However, sometimes a significant goiter may develop and prompt the doctor to measure tests of thyroid function.

WHAT IS THE THYROID GLAND?

The thyroid gland is a butterfly-shaped endocrine gland that is normally located in the lower front of the neck. The thyroid’s job is to make thyroid hormones, which are secreted into the blood and then carried to every tissue in the body. Thyroid hormone helps the body use energy, stay warm and keep the brain, heart, muscles, and other organs working as they should.

WHAT IS THE INTERACTION BETWEEN THE THYROID FUNCTION OF THE MOTHER AND THE BABY?

For the first 18-20 weeks of pregnancy, the baby is completely dependent on the mother for the production of thyroid hormone. By mid-pregnancy, the baby’s thyroid begins to produce thyroid hormone on its own. The baby, however, remains dependent on the mother for ingestion of adequate amounts of iodine, which is essential to make the thyroid hormones. The World Health Organization recommends iodine intake of 250 micrograms/day during pregnancy to maintain adequate thyroid hormone production. Because iodine intakes in pregnancy are currently low in the United States, the ATA recommends that US women who are planning pregnancy, pregnant, or breastfeeding should take a daily supplement containing 150 mcg of iodine.

The baby, however, remains dependent on the mother for ingestion of adequate amounts of iodine, which is essential to make the thyroid hormones. The World Health Organization recommends iodine intake of 250 micrograms/day during pregnancy to maintain adequate thyroid hormone production. Because iodine intakes in pregnancy are currently low in the United States, the ATA recommends that US women who are planning pregnancy, pregnant, or breastfeeding should take a daily supplement containing 150 mcg of iodine.

Hyperthyroidism & Pregnancy

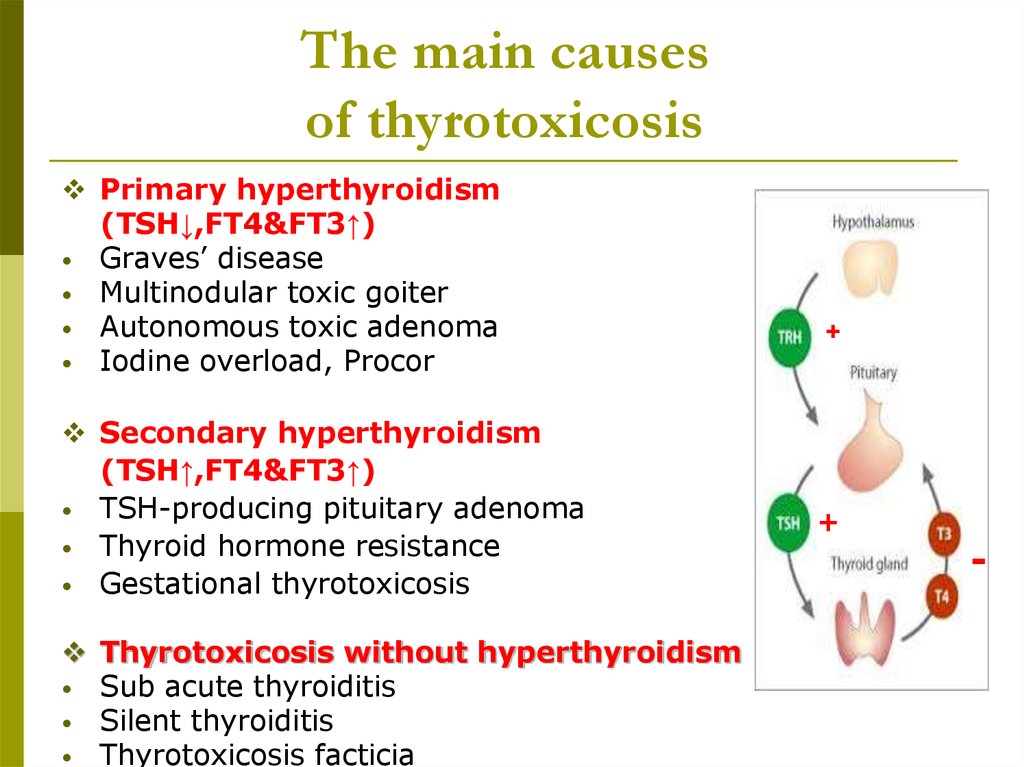

WHAT ARE THE MOST COMMON CAUSES OF HYPERTHYROIDISM DURING PREGNANCY?

Overall, the most common cause of hyperthyroidism in women of childbearing age is Graves’ disease (see Graves’ Disease brochure), which occurs in 0.2% of pregnant patients. In addition to other usual causes of hyperthyroidism (see Hyperthyroidism brochure), very high levels of hCG, seen in severe forms of morning sickness (hyperemesis gravidarum), may cause transient hyperthyroidism in early pregnancy. The correct diagnosis is based on a careful review of history, physical exam and laboratory testing.

The correct diagnosis is based on a careful review of history, physical exam and laboratory testing.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS OF GRAVES' DISEASE/ HYPERTHYROIDISM TO THE MOTHER?

Graves’ disease may present initially during the first trimester or may be exacerbated during this time in a woman known to have the disorder. In addition to the classic symptoms associated with hyperthyroidism, inadequately treated maternal hyperthyroidism can result in early labor and a serious complication known as pre-eclampsia. Additionally, women with active Graves’ disease during pregnancy are at higher risk of developing very severe hyperthyroidism known as thyroid storm. Graves’ disease often improves during the third trimester of pregnancy and may worsen during the post partum period.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS OF GRAVES' DISEASE/ HYPERTHYROIDISM TO THE BABY?

The risks to the baby from Graves’ disease are due to one of three possible mechanisms:

- UNCONTROLLED MATERNAL HYPERTHYROIDISM: Uncontrolled maternal hyperthyroidism has been associated with fetal tachycardia (fast heart rate), small for gestational age babies, prematurity, stillbirths and congenital malformations (birth defects).

This is another reason why it is important to treat hyperthyroidism in the mother.

This is another reason why it is important to treat hyperthyroidism in the mother. - EXTREMELY HIGH LEVELS OF THYROID STIMULATING IMMUNOGLOBLULINS (TSI): Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder caused by the production of antibodies that stimulate the thyroid gland referred to as thyroid stimulating immunoglobulins (TSI). These antibodies do cross the placenta and can interact with the baby’s thyroid. High levels of maternal TSI’s have been known to cause fetal or neonatal hyperthyroidism, but this is uncommon (only 1-5% of women with Graves’ disease during pregnancy). Fortunately, this typically only occurs when the mother’s TSI levels are very high (many times above normal). Measuring TSI in the mother with Graves’ disease is recommended in early pregnancy and, if initially elevated, again around weeks 18-22.When a mother with Graves’ disease requires antithyroid drug therapy during pregnancy, fetal hyperthyroidism is rare because antithyroid drugs also cross the placenta and can prevent the fetal thyroid from becoming overactive.

Of potentially more concern to the baby is when the mother has been treated for Graves’ disease (for example radioactive iodine or surgery) and no longer requires antithyroid drugs. It is very important to tell your doctor if you have been treated for Graves’ Disease in the past so proper monitoring can be done to ensure the baby remains healthy during the pregnancy.

Of potentially more concern to the baby is when the mother has been treated for Graves’ disease (for example radioactive iodine or surgery) and no longer requires antithyroid drugs. It is very important to tell your doctor if you have been treated for Graves’ Disease in the past so proper monitoring can be done to ensure the baby remains healthy during the pregnancy. - ANTI-THYROID DRUG THERAPY (ATD). Methimazole (Tapazole) or propylthiouracil (PTU) are the ATDs available in the United States for the treatment of hyperthyroidism (see Hyperthyroidism brochure). Both of these drugs cross the placenta and can potentially impair the baby’s thyroid function and cause fetal goiter. Use of either drug in the first trimester of pregnancy has been associated with birth defects, although the defects associated with PTU are less frequent and less severe. Definitive therapy (thyroid surgery or radioactive iodine treatment) may be considered prior to pregnancy in order to avoid the need to use PTU or methimazole in pregnancy.

When ATDs are required, PTU is preferred until week 16 of pregnancy. It is recommended that the lowest possible dose of ATD be used to control maternal hyperthyroidism in order to minimize the development of hypothyroidism in the baby. Overall, the benefits to the baby of treating a mother with hyperthyroidism during pregnancy outweigh the risks if therapy is carefully monitored.

When ATDs are required, PTU is preferred until week 16 of pregnancy. It is recommended that the lowest possible dose of ATD be used to control maternal hyperthyroidism in order to minimize the development of hypothyroidism in the baby. Overall, the benefits to the baby of treating a mother with hyperthyroidism during pregnancy outweigh the risks if therapy is carefully monitored.

WHAT ARE THE TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR A PREGNANT WOMAN WITH GRAVES' DISEASE/ HYPERTHYROIDISM?

Mild hyperthyroidism (slightly elevated thyroid hormone levels, minimal symptoms) often is monitored closely without therapy as long as both the mother and the baby are doing well. When hyperthyroidism is severe enough to require therapy, anti-thyroid medications are the treatment of choice, with PTU being preferred in the first trimester. The goal of therapy is to keep the mother’s free T4 in the high-normal to mildly elevated range on the lowest dose of antithyroid medication. Addition of levothyroxine to ATDs (“block-and-replace”) is not recommended. Targeting this range of free hormone levels will minimize the risk to the baby of developing hypothyroidism or goiter. Maternal hypothyroidism should be avoided. Therapy should be closely monitored during pregnancy. This is typically done by following thyroid function tests (TSH and thyroid hormone levels) monthly.

Targeting this range of free hormone levels will minimize the risk to the baby of developing hypothyroidism or goiter. Maternal hypothyroidism should be avoided. Therapy should be closely monitored during pregnancy. This is typically done by following thyroid function tests (TSH and thyroid hormone levels) monthly.

In patients who cannot be adequately treated with anti-thyroid medications (i.e. those who develop an allergic reaction to the drugs), surgery is an acceptable alternative. Surgical removal of the thyroid gland is safest in the second trimester.

Radioiodine is contraindicated to treat hyperthyroidism during pregnancy since it readily crosses the placenta and is taken up by the baby’s thyroid gland. This can cause destruction of the gland and result in permanent hypothyroidism.

Beta-blockers can be used during pregnancy to help treat significant palpitations and tremor due to hyperthyroidism. They should be used sparingly due to reports of impaired fetal growth associated with long-term use of these medications. Typically, these drugs are only required until the hyperthyroidism is controlled with anti-thyroid medications.

Typically, these drugs are only required until the hyperthyroidism is controlled with anti-thyroid medications.

WHAT IS THE NATURAL HISTORY OF GRAVES' DISEASE AFTER DELIVERY?

Graves’ disease typically worsens in the postpartum period or may occur then for the first time. When new hyperthyroidism occurs in the first months after delivery, the cause may be either Graves’ disease or postpartum thyroiditis and testing with careful follow-up is needed to distinguish between the two. Higher doses of anti-thyroid medications may be required during this time. As usual, close monitoring of thyroid function tests is necessary.

CAN THE MOTHER WITH GRAVES' DISEASE, WHO IS BEING TREATED WITH ANTI-THYROID DRUGS, BREASTFEED HER INFANT?

Yes. Although very small quantities of both PTU and methimazole are transferred into breast milk, total daily doses of up to 20mg methimazole or 450mg PTU are considered safe and monitoring of the breastfed infants’ thyroid status is not required.

Click ‘+’ button to see all topics

PDF Resources

Hyperthyroidism in Pregnancy Brochure PDF

Hyperthyroidism in Pregnancy FAQ

Articles

Vibhavasu Sharma, MD, FACE Albany Medical College, Albany, NY August 13, 2020 Thyroid disease…

Read More

From Clinical Thyroidology® for the Public: GUEST BLOG FROM THE IODINE GLOBAL NETWORK Timing matters for…

Read More

October 2, 2018—The American Thyroid Association (ATA) will hold its 88th Annual Meeting on October…

Read More

More Articles on Hyperthyroidism in Pregnancy

FURTHER INFORMATION

For information on thyroid patient support organizations, please visit the Patient Support Links section on the ATA website at www.thyroid.org

Diseases of the thyroid gland during pregnancy

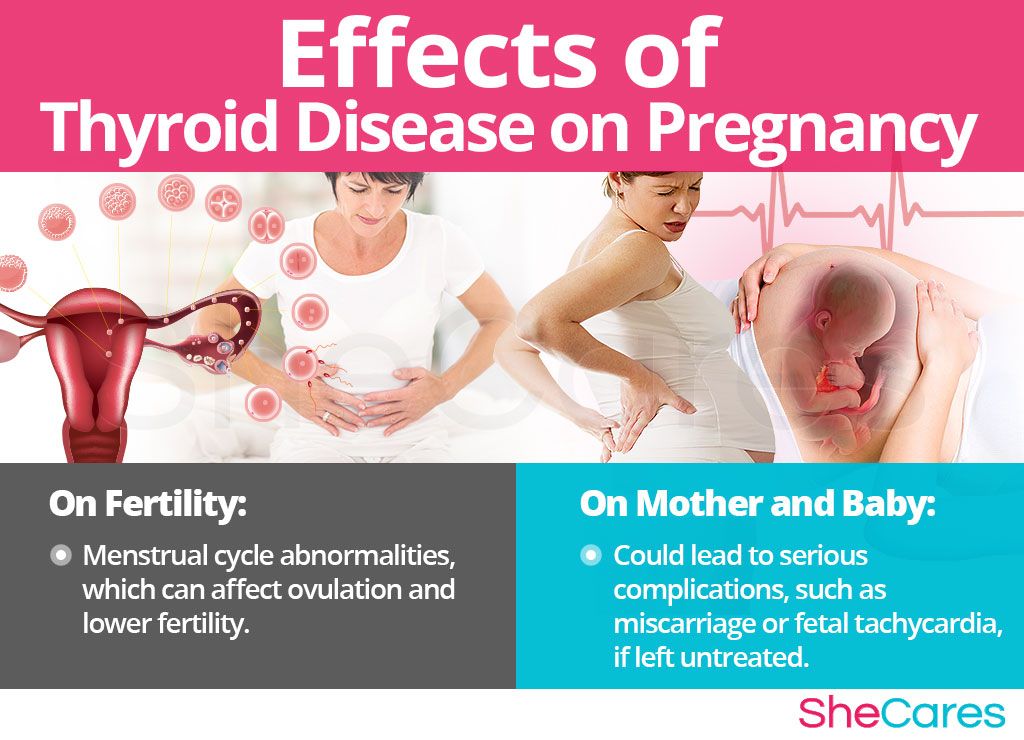

Diseases of the thyroid gland (TG) are a common pathology in women at a young, reproductive age and occur 5-10 times more often than in men. Violation of the normal functioning of the thyroid gland (hypothyroidism or thyrotoxicosis, i.e. lack or excess of thyroid hormones in the body) can cause menstrual irregularities, anovulation (lack of ovulation), and lead to infertility.

Violation of the normal functioning of the thyroid gland (hypothyroidism or thyrotoxicosis, i.e. lack or excess of thyroid hormones in the body) can cause menstrual irregularities, anovulation (lack of ovulation), and lead to infertility.

Early detection and timely correction of thyroid diseases in women with infertility planning ART programs (assisted reproductive technologies) is extremely important. this will minimize the adverse impact on fertility (the ability to produce viable offspring), the state of the ovarian reserve (follicular reserve - the number of eggs potentially ready for fertilization at a given time) and the quality of oocytes, will increase the effectiveness of ART programs, reduce the risk of early reproductive losses (spontaneous abortions , miscarriage, etc.).

Today, in the era of improving family planning methods, the development of information technology, an important factor is to increase the knowledge of women planning pregnancy about possible thyroid diseases and the consequences that they can have in relation to the development of pregnancy, its course and direct impact on the fetus. Timely seeking medical help in highly qualified medical institutions even at the stage of pregnancy planning will allow correcting existing disorders in time, improving fertility rates and future pregnancy outcomes.

Timely seeking medical help in highly qualified medical institutions even at the stage of pregnancy planning will allow correcting existing disorders in time, improving fertility rates and future pregnancy outcomes.

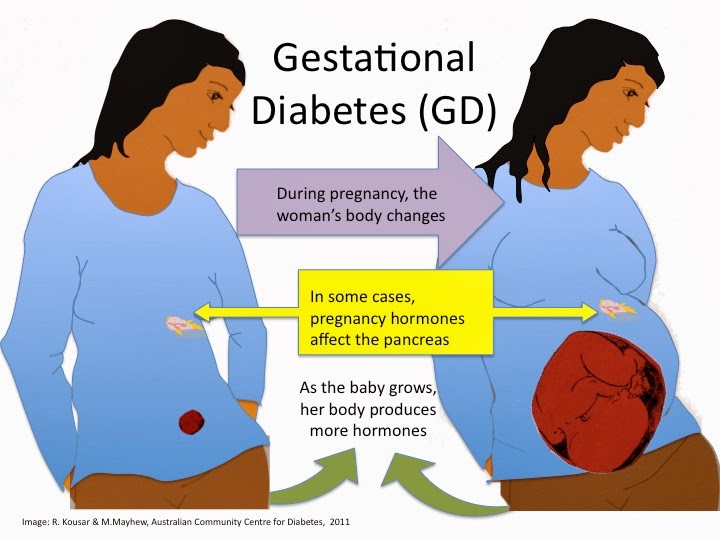

You should know that already from the first weeks of pregnancy there are significant changes in the functioning of the thyroid gland (an increase in the production of thyroid hormones by 30-50%) under the influence of various endogenous stimulating factors. This physiological mechanism of "increased work" of the thyroid gland during pregnancy is quite understandable and justified, because. until the moment when the fetus's own thyroid gland begins to function, the entire embryogenesis (the physiological process during which the formation and development of the embryo occurs), incl. the formation of the central nervous system occurs with the participation of maternal thyroid hormones!

So, the most powerful thyroid stimulator in the first trimester of pregnancy is hCG (chorionic gonadotropin).

- The hormone begins to be produced by the chorion tissue after implantation of the embryo as early as 6-8 days after fertilization of the egg and is one of the most important indicators of the presence and successful development of pregnancy.

- Due to the effects of CG, there is a significant increase in the production of thyroid hormones by the thyroid gland. By the 18-20th week of pregnancy, with the participation of a number of other mechanisms, there is a significant increase in the total content of thyroid hormones in the body of a pregnant woman.

- In 20-30% of women, there is even the development of the so-called state of "transient gestational hyperthyroidism" (does not require drug correction).

- In the II-III trimesters of pregnancy, thyroid hormones return to normal levels.

Iodine is a unique and the only microelement that is involved in the formation of thyroid hormones: it is part of the thyroid hormones - tri-iodine-thyronine (T3) and tetra (= four) -iodine-thyronine, T4).

The fetal thyroid gland matures only by 16-17 weeks of pregnancy and begins to function independently. For the full-fledged work of the fetal glands and the formation of its own thyroid hormones, it needs iodine, which it receives only from the mother! By transplacental transfer or with mother's milk during lactation. Thyroid hormones are necessary for the fetus for the full development and maturation of all its organs (primarily in the early stages of embryogenesis), as well as for the adequate formation of the central nervous system and the correct adaptation of the newborn to extrauterine life.

During pregnancy, iodine excretion in the urine and transfer through the placenta increases, which causes additional indirect stimulation of the woman's thyroid gland. However, in conditions of iodine deficiency (the entire territory of the Russian Federation!) in a pregnant woman against the background of increased loss in iodine, the connection of powerful compensatory mechanisms may not be enough to ensure a significant increase in the production of thyroid hormones of the thyroid gland, which often leads to the development of a goiter in a pregnant woman (an increase in the size of the thyroid gland / gland above normal indicators - 18 cm3).

Iodine deficiency during pregnancy can affect the development of the fetus and lead to perinatal complications (pathological conditions and diseases of the fetus after the 28th week and during the neonatal period) - spontaneous abortions, stillbirths, congenital malformations, endemic cretinism (dementia), goiter / congenital decrease in thyroid function (hypothyroidism) in a newborn, in later life - endemic goiter, irreversible decline in mental abilities (intellectual and neurological development), reduced fertility.

In view of the above, it becomes clear that the need for iodine in a pregnant woman increases, and she needs adequate iodine intake during pregnancy (at a dose of at least 250 mcg / day as part of iodine preparations according to WHO recommendations) for the full functioning of her own thyroid gland, as well as (with an increase in gestation) the formed thyroid gland of the fetus.

It should be emphasized once again that in the presence of adequate amounts of the main component of the synthesis of thyroid hormones - iodine - there will be no adverse effects on the course of pregnancy and fetal development!

Already at the stage of pregnancy planning, it is advisable for women to prescribe individual iodine prophylaxis with physiological doses of iodine (200 mcg / day - for example, one tablet of Iodomarin or IodBalance daily). Prevention of iodine deficiency in children under 1 year of age - breastfeeding and mother taking iodine preparations at a dose of 250 mcg / day for the entire period of feeding or mixtures for full-term children with an iodine content of 100 mcg / l.

Prevention of iodine deficiency in children under 1 year of age - breastfeeding and mother taking iodine preparations at a dose of 250 mcg / day for the entire period of feeding or mixtures for full-term children with an iodine content of 100 mcg / l.

Diseases of the thyroid gland in women leading to either a decrease in function (HYPOTHYROISISM) or an increase in its function (THYROTOXICOSIS) can lead to impaired fertility and be a risk factor for pregnancy complications and fetal developmental disorders.

Hypothyroidism

In a situation where a woman has thyroid disease even before pregnancy, leading to a decrease in her function (hypothyroidism), physiological hyperstimulation of the thyroid gland during pregnancy (on its own or in IVF programs) to one degree or another affects her reserve possibilities, and even the use of powerful compensatory mechanisms is insufficient to ensure such a significant increase in the production of thyroid hormones during pregnancy.

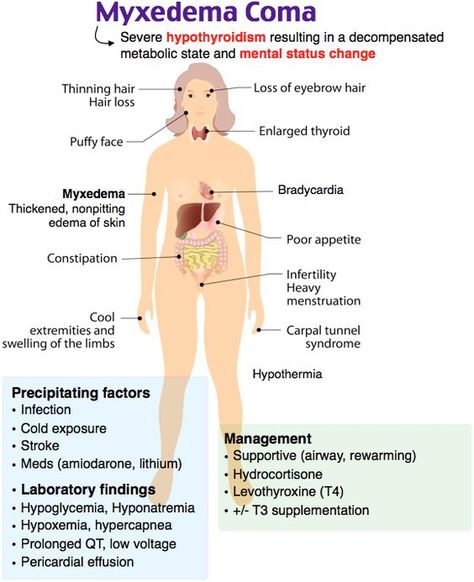

Hypothyroidism during pregnancy is the most dangerous for the development of the fetus and, first of all, damage to the central nervous system, intrauterine death, the formation of congenital malformations, as well as the birth of a child with low weight, neurological diseases in the newborn. The state of hypothyroidism in the mother increases the risk of spontaneous abortion, postpartum hemorrhage, preeclampsia (impaired cerebral circulation, which can lead to cerebral edema, increased intracranial pressure, and functional disorders of the nervous system).

Assessment of thyroid function is performed for all women with reproductive disorders (infertility, miscarriage, etc.). Timely correction of thyroid dysfunction is carried out by an endocrinologist at the stage of preparation for ART programs!

Compensated hypothyroidism is not a contraindication for pregnancy planning, incl. in ART programs! (in women with compensated hypothyroidism during pregnancy and an increase in the need for thyroid hormones, the dose of levothyroxine (L-T4), which they took before pregnancy, is immediately increased by about 30-50%).

Thyroid function is assessed only by the level of thyroid-stimulating hormone ("TSH") in the blood (a hormone secreted by the anterior pituitary gland - a gland located on the lower surface of the brain and which has a direct stimulating effect on the functioning of the thyroid gland).

As mentioned above, normal early pregnancy is characterized by a highly normal or even elevated level of thyroid hormones, and therefore, “according to the principle of negative feedback”, a low or even suppressed (in 20-30% of women) TSH level will be noted: < 2.5 honey/l.

Screening for thyroid dysfunction should be carried out as early as possible: it is better during the determination (beta-subunit of hCG for pregnancy detection!

It is advisable to monitor the level of TSH and T4 in the blood every 4 weeks in the first trimester, and then as needed. Adequate replacement therapy is considered to maintain the level of TSH at the lower limit of the reference values for the corresponding gestational age.

Thyrotoxicosis

Thyrotoxicosis (increased function of the thyroid gland) develops relatively rarely during pregnancy (1-2 per 1000 pregnancies). Almost all cases of thyrotoxicosis in pregnant women are associated with Graves' disease (GD or toxic diffuse goiter, a chronic autoimmune disorder in which there is an increase and hyperfunction of the thyroid gland) with the development of hyperthyroidism against the background of the stimulating effect of hCG. If a woman had Graves' disease before pregnancy, then the risk of an exacerbation (recurrence) of the disease is high in the early period of pregnancy.

Inadequate treatment of thyrotoxicosis is associated with the development of complications: spontaneous abortion, delayed intrauterine development of the fetus, stillbirth, premature birth, preeclampsia, heart failure.

If a woman with Graves' disease plans to undergo ART programs, then only against the background of stable normalization of thyroid function (at least after 24 months, i. e. 18 months of treatment + normal thyroid hormone levels for at least 6 months without treatment!). Inadequately treated Greivas disease is clearly associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, in particular the risk of miscarriage, in ART programs!

e. 18 months of treatment + normal thyroid hormone levels for at least 6 months without treatment!). Inadequately treated Greivas disease is clearly associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, in particular the risk of miscarriage, in ART programs!

Assessment of thyroid function is carried out by the level of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), blood thyroid hormones (T4, T3) with an assessment of the titer of "thyroid-stimulating" antibodies in the blood (anti-rTTH antibodies should be significantly increased!).

According to modern concepts, thyrotoxicosis on the background of Graves' disease is not an indication for abortion, since effective and relatively safe methods of conservative treatment of this disease have now been developed.

If a pregnant woman (including a young woman with preserved ovarian reserve and planning ART) has thyrotoxicosis, the main goal of treatment is to prescribe thyreostatics (drugs that suppress the synthesis of thyroid hormones) in the minimum effective dose for maintaining the level of T4 at the upper limit of normal or slightly above normal. Propylthiouracil (PTU) is considered the drug of choice (taking into account safety for the fetus) in the first trimester, and thiamazole (tyrosol) in an equivalent dose is used from the second trimester. The level of T4, TK is monitored every 4 weeks.

Propylthiouracil (PTU) is considered the drug of choice (taking into account safety for the fetus) in the first trimester, and thiamazole (tyrosol) in an equivalent dose is used from the second trimester. The level of T4, TK is monitored every 4 weeks.

With an increase in the duration of pregnancy, the severity of thyrotoxicosis naturally decreases and the need for drugs decreases, which, as a rule, are completely canceled in most women in the third trimester of pregnancy. When taking low doses of PTU (100 mg / day) or tyrosol (5-10 mg), breastfeeding is quite safe for the baby. However, in 2-3 months after delivery, in most cases, a relapse (aggravation) of thyrotoxicosis develops, requiring an increase in the dose of thyreostatic.

Radioactive iodine therapy (I-131) can be an alternative treatment for thyrotoxicosis in a woman outside of pregnancy (including a young woman with preserved ovarian reserve and planning ART) against the background of Graves' disease (or its relapse after therapy with thyreostatics). After radioactive iodine therapy, planning an independent pregnancy or conducting ART programs is possible only 12 months after the end of treatment, during the entire period of treatment (12 months) it is necessary to use effective methods of contraception - radioactive iodine therapy during pregnancy and lactation is contraindicated!

After radioactive iodine therapy, planning an independent pregnancy or conducting ART programs is possible only 12 months after the end of treatment, during the entire period of treatment (12 months) it is necessary to use effective methods of contraception - radioactive iodine therapy during pregnancy and lactation is contraindicated!

It should be known that in women of advanced reproductive age (over 35) with reduced ovarian reserve, the treatment of choice for Graves' disease is surgical removal of the thyroid gland (thyroidectomy). This treatment tactic is recognized as the most effective and safe and makes it possible to plan ART as soon as possible! The tactics of long-term treatment with thyreostatics (more than 1.5 years) and follow-up (6 months) to confirm stable normalization of thyroid function, as well as a high probability of recurrence of thyrotoxicosis during pregnancy in ART programs, is not justified in women of late reproductive age.

Often in the postpartum period there is an exacerbation of thyroid disease (in 5-9% of all women), which occurred in the mother before conception. Therefore, after childbirth, such women should continue to be observed by an endocrinologist.

Therefore, after childbirth, such women should continue to be observed by an endocrinologist.

Postpartum thyroiditis

This condition is characterized by temporary dysfunction of the thyroid gland that occurs during the first year after childbirth. The pathogenesis (mechanism of the onset and development of the disease) of postpartum thyroiditis is an autoimmune inflammation of the thyroid gland that develops against the background of a genetic predisposition (a clear relationship has been established with the HLA-A26 / BW46 / BW67 / A1 / B8 genes in women with this disease). The main significance in the development of postpartum thyroiditis is assigned to the immune reaction, or the "rebound" phenomenon, which consists in a sharp increase in the activity of the immune system after its long known physiological suppression during pregnancy, which in predisposed individuals can provoke the development of autoimmune thyroid disease.

The classic clinical picture includes a three-phase process.

Initially, 8-12 weeks after birth, transient hyperthyroidism develops (increased levels of thyroid hormones in the blood), due to the release of ready-made thyroid hormones stored in the thyroid gland into the blood, lasts an average of 1-2 months, no specific treatment is required.

This is followed by a phase of recovery of thyroid function, culminating in a phase of hypothyroidism (decrease in thyroid function), which already requires the appointment of thyroid hormone replacement therapy (L-T4).

The hypothyroid phase has a large number of symptoms: depression, irritability, dry skin, asthenia, fatigue, headache, decreased ability, concentration, constipation, muscle and joint pain.

Blood hormones (TSH, T4) are monitored every 4 weeks. After 6-8 months, thyroid function is usually restored.

Make an appointment

Thyroid disorders and pregnancy | Burumkulova

In their practice, both endocrinologists and obstetrician-gynecologists often encounter various thyroid diseases in pregnant women, which is of significant clinical and scientific interest both for studying the pathology of these disorders and in terms of their treatment.

As you know, pregnancy often leads to goiter. An increase in the size and volume of the thyroid gland during pregnancy is observed due to both a more intensive blood supply to the thyroid tissue and an increase in the mass of the thyroid tissue. 3 factors can stimulate thyroid function during pregnancy: an increase in the degree of binding of thyroid hormones (TG) to blood proteins, an increase in the level of chorionic gonadotropin (CG) in the blood of pregnant women, and an insufficient supply of iodine to the thyroid gland due to increased excretion of iodine in the urine during pregnancy (see . picture).

Increased binding of TG to blood proteins. More than 99% of TG circulating in the blood is bound to plasma proteins: thyroxine-binding globulin (TSG), thyroxine-binding prealbumin and albumin. The relative distribution of the amount of TG binding to various binding proteins directly depends on the degree of their affinity and concentration. 80% of TG is associated with TSH. The bound and inactive TG fractions are in equilibrium with the "free" unbound fraction, which represents only a small fraction of all circulating TG: 0.03-0.04% for free thyroxine (swT 4 ) and 0.3-0.5% for free triiodothyronine (swt 3 ). However, it is this fraction that provides all the metabolic and biological activity of TH.

The bound and inactive TG fractions are in equilibrium with the "free" unbound fraction, which represents only a small fraction of all circulating TG: 0.03-0.04% for free thyroxine (swT 4 ) and 0.3-0.5% for free triiodothyronine (swt 3 ). However, it is this fraction that provides all the metabolic and biological activity of TH.

During pregnancy, already a few weeks after conception, the serum level of TSH progressively increases as a result of stimulation by a significant amount of estrogens produced by the placenta. Then the level of TSH reaches a plateau, which is maintained until the moment of delivery. Conversely, the level of 2 other circulating binding proteins tends to decrease, mainly as a result of passive

Scheme of thyroid stimulation during pregnancy

dilution due to increased vascular pool (blood depot).

Increased TSH production during pregnancy results in an increase in total TG levels. The levels of total T 4 (vb 4 ) and T 3 (vb 3 ) increase significantly during the first half of pregnancy and reach a plateau by the 20th week, remaining at the same level thereafter. Transient decrease in the amount of svt 4 and svTz on the feedback principle stimulates the release of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and restoration of homeostasis of the level of free forms of TG.

Transient decrease in the amount of svt 4 and svTz on the feedback principle stimulates the release of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and restoration of homeostasis of the level of free forms of TG.

Adequate maintenance of thyroid homeostasis is disturbed in about 1/3 of pregnant women, which leads to the development of a state of relative hypothyroxinemia.

Stimulation of thyroid function during pregnancy hCG. CG is secreted by the placenta only in primates. It is produced in large quantities by placental syncytiotrophoblasts, especially in the first quarter of pregnancy. The most important function of hCG is the stimulation of steroidogenesis, first in the corpus luteum, then in the placenta.

The value of hCG for thyroid stimulation in women during pregnancy is not fully understood. It is known that there is a correlation between the suppression of TSH secretion and an increase in the concentration of hCG, as well as between the level of hCG and the level of fT 4 . CG is able to have a direct stimulating effect on the mother's thyroid gland (and this effect is most pronounced at the end of the first trimester of pregnancy) due to the molecular similarity of CG to TSH. Acting in early pregnancy as a weak 'analogue' of TSH, hCG is responsible for the slight increase in serum FTT levels 4 and svt 3 and, as a result, for a decrease in serum TSH levels. In the vast majority of healthy pregnant women, the stimulatory effect of CG on the thyroid gland is short and insignificant. However, in 1-2% of all pregnant women during the first trimester of pregnancy, there is a decrease in the concentration of TSH and an increase in the level of sT 3 , which is accompanied by a clinic of thyrotoxicosis. This syndrome is called ''gestational transient thyrotoxicosis'' (GTT).

CG is able to have a direct stimulating effect on the mother's thyroid gland (and this effect is most pronounced at the end of the first trimester of pregnancy) due to the molecular similarity of CG to TSH. Acting in early pregnancy as a weak 'analogue' of TSH, hCG is responsible for the slight increase in serum FTT levels 4 and svt 3 and, as a result, for a decrease in serum TSH levels. In the vast majority of healthy pregnant women, the stimulatory effect of CG on the thyroid gland is short and insignificant. However, in 1-2% of all pregnant women during the first trimester of pregnancy, there is a decrease in the concentration of TSH and an increase in the level of sT 3 , which is accompanied by a clinic of thyrotoxicosis. This syndrome is called ''gestational transient thyrotoxicosis'' (GTT).

Possible reasons for the increase in the level of CG and the development of GTT may be the following: 1) unbalanced production of CG due to transient overexpression of the gene encoding the P-subunit of CG; 2) changes in the degree of glycosylation of the CG molecule, which in turn leads to a prolongation of its half-life; 3) an increase in the mass of placental trophoblast syncytial cells in some women (for example, in multiple pregnancies). In multiple pregnancy, the concentration of hCG increases in proportion to the number of placentas.

In multiple pregnancy, the concentration of hCG increases in proportion to the number of placentas.

GTT is often accompanied by uncontrollable vomiting of pregnant women (hyperemesis gravidatum), which makes its diagnosis difficult due to the fact that nausea and vomiting are in principle characteristic of early pregnancy. This condition is usually transient and resolves by the second trimester of pregnancy. The diagnosis of HTT is made on the basis of an elevated level of hCG, a slightly suppressed concentration of TSH, an increase in serum levels of fT 4 and FT 3 to the levels characteristic of hyperthyroidism. Treatment with thyreostatics GTT is not indicated; with severe clinical symptoms, only a short course of β-blockers is sufficient.

Thus, it is important for clinicians to know that the symptoms of thyrotoxicosis during pregnancy have specific differences and may result not only from an autoimmune process in the thyroid gland, but also from hormonal changes inherent in pregnancy itself.

Reduced availability of iodine while increasing the need for it during pregnancy. The increased need for iodine during pregnancy is due to two factors. On the one hand, during pregnancy, there is an additional loss of iodine from the mother's body due to increased renal clearance of iodide, on the other hand, the loss of iodide in the second half of pregnancy increases due to the fact that part of the maternal pool of inorganic iodide is consumed by the fetoplacental complex and is used for synthesis TG thyroid of the fetus.

For women living in countries with sufficient iodine intake (such as Japan, the United States or Scandinavia), iodine loss during pregnancy is not significant, since daily iodine intake is more than 150-200 mcg/day and remains satisfactory in throughout the entire pregnancy.

At the same time, in regions with moderate and severe iodine deficiency in the biosphere, which include the vast majority of Russia, reduced iodine intake (less than 100 µg/day) is a rather severe factor in thyroid stimulation during pregnancy.

The risk of developing thyroid disease during pregnancy is higher in women with a history of goiter (diffuse or nodular), and the number and size of the nodules may increase during pregnancy. Repeated pregnancy leads to a further increase in the size of the thyroid gland and increased nodulation.

In 1989, D. Glinoer et al. proposed a hypothesis according to which increased thyroid stimulation during pregnancy can lead to the formation of diffuse non-toxic goiter (DNG), and pregnancy is one of the factors causing pathological changes in the thyroid gland.

In clinical practice, the following biochemical parameters have been proposed to detect increased thyroid stimulation during pregnancy.

— Presence of relative hypothyroxinemia observed in about 1/3 of all pregnant women. For its diagnosis, certain ratios T 4 /TSG are recommended.

- Increased secretion of T 3 , manifested in an increase in the ratio of T 3 / T 4 more than 0. 025 and reflecting the stimulation of the thyroid gland in conditions of iodine deficiency.

025 and reflecting the stimulation of the thyroid gland in conditions of iodine deficiency.

- Change in the concentration of TSH in the blood. After the initial phase of suppression of the TSH level due to the high secretion of CG at the end of the first trimester of pregnancy, the TSH level progressively increases and its concentration by the time of delivery doubles in relation to the initial one. The increase in TSH levels usually remains within the normal range (<4 mU/L).

- Change in the concentration of thyroglobulin (Tg) in the blood serum. The serum level of Tg is a sensitive indicator of thyroid stimulation, which often increases during pregnancy: its increase is already observed in the first trimester, but is most pronounced in the third trimester and by the time of delivery. By the time of delivery, 60% of pregnant women have an elevated level of Tg in the blood.

An increase in Tg concentration correlates with other indicators of thyroid stimulation, such as a slight increase in TSH levels and an increase in the ratio of T 3 /T 4 more than 0. 025. The presence of a correlation between the level of Tg and the volume of the thyroid gland (according to ultrasound - ultrasound confirms that the level of Tg in the blood is a fairly reliable biochemical marker of the goiterogenic effect of pregnancy.

025. The presence of a correlation between the level of Tg and the volume of the thyroid gland (according to ultrasound - ultrasound confirms that the level of Tg in the blood is a fairly reliable biochemical marker of the goiterogenic effect of pregnancy.

intellectual and physical development of the child.As is known, the thyroid gland of the fetus acquires the ability to concentrate iodine and synthesize iodothyronines at 10-12 weeks of intrauterine development.0103 4 , vT 4 and TSH reach adult levels around the 36th week of pregnancy.

The issue of placental permeability for triglycerides has been debatable for a long time. It is currently assumed that maternal and fetal thyroid glands are regulated autonomously, but not independently of each other. Apparently, the transplacental transfer of TG from the mother's body to the fetus is observed only at an early stage of intrauterine development.

In addition, the activity of the thyroid gland of the fetus is completely dependent on the intake of iodine from the mother's body. As a result of both insufficient intake of iodine in the mother’s body and a low intrathyroid iodine reserve, fetal thyroid stimulation occurs, which is reflected in a significant increase (compared with those of the mother) in the levels of neonatal TSH and Tg, as well as the development of goiter in the fetus. The development of hypothyroidism in the prenatal and neonatal periods can lead to an irreversible decrease in the child's mental development up to endemic cretinism.

As a result of both insufficient intake of iodine in the mother’s body and a low intrathyroid iodine reserve, fetal thyroid stimulation occurs, which is reflected in a significant increase (compared with those of the mother) in the levels of neonatal TSH and Tg, as well as the development of goiter in the fetus. The development of hypothyroidism in the prenatal and neonatal periods can lead to an irreversible decrease in the child's mental development up to endemic cretinism.

For the treatment of DND during pregnancy in regions with insufficient iodine intake, it is advisable to recommend iodine intake at the rate of 150-250 mcg/day. To do this, you can use the Antistrumine drug available in the pharmacy network (1000 μg of potassium iodide in 1 tablet), 1 tablet 1-2 times a week.

Another iodine preparation is "Potassium iodide-200" tablets, manufactured by Berlin-Chemie. They must be taken daily. An alternative may be imported multivitamins containing a daily dose of iodine (150 micrograms). As a rule, these prescriptions will be enough to prevent further growth of the goiter and even achieve a reduction in its volume.0003

As a rule, these prescriptions will be enough to prevent further growth of the goiter and even achieve a reduction in its volume.0003

In the presence of a large goiter before pregnancy or with its rapid growth at the beginning of pregnancy, a combination of iodine and thyroid hormones is justified: either Thyreocomb containing 70 µg T 4 , 10 µg T 3 and 150 µg iodine, or 50-100 mcg T 4 daily and additionally 1 tablet of antistrumine 2-3 times a week. This allows you to quickly and effectively restore the normal function of the mother's thyroid gland and prevent the goiter effect of pregnancy.

The development of hyperthyroidism during pregnancy is relatively rare and occurs in 0.05-3% of pregnant women. In most cases, its cause is diffuse toxic goiter (DTG), while toxic adenoma or multinodular toxic goiter are much less common.

The main difficulty in diagnosing thyrotoxicosis during pregnancy is that many clinical symptoms and signs of thyrotoxicosis can be masked by manifestations of a normal pregnancy (tachycardia, weakness, irritability, vegetative disorders, etc. ).

).

Diagnosis of DTG must be confirmed by history, ultrasound of the thyroid gland, as well as the study of the levels of TSH, sT 3 and especially sT 4 in the blood.

A typical error in the interpretation of the results of the study of hormonal function in pregnant women can be considered the determination of levels of vT 9vT 4 and vT 3 , which does not reflect the true functional state of the thyroid gland.

Thyrostatic drugs (mercasolil, methimazole, propylthiouracil) are preferred in all countries for the treatment of DTG in pregnant women. Surgical treatment is recommended only in exceptional cases, such as severe side effects, very large goiter, suspected malignancy, or the need to use high doses of thyreostatics to maintain maternal euthyroidism. The optimal time for subtotal resection of the thyroid gland is the second trimester of pregnancy. The appointment of iodides during pregnancy is contraindicated because of the risk of developing hypothyroidism in the fetus and goiter due to the Wolf-Chaikov effect.

What principles should be followed when treating a pregnant woman with DTG?

- The choice of a specific thyreostatic is determined both by the doctor's personal experience and the availability of a particular drug. In our country, mercasolil (1-methyl-2-mercaptoimidazole) or its analogues (methimazole, thiamazole) are more often used to treat DTG during pregnancy. Abroad, in a similar situation, preference is given to propylthiouracil (6-propyl-2-thiouracil). At present, a preparation of this group under the name Propicil (Kali-Khemi) has been registered and made available in Russia.

The frequency of side effects of therapy is the same for propylthiouracil and mercazolil. Both drugs cross the placenta, and excessive doses of them can cause the development of hypothyroidism and goiter in utero and neonatal periods.

Prescribing propylthiouracil during pregnancy nevertheless has a number of advantages. Firstly, the kinetics of propylthiouracil does not change during pregnancy, secondly, the half-life of propylthiouracil from the blood does not depend on the presence of hepatic or renal insufficiency, thirdly, propylthiouracil binds to proteins to a greater extent compared to mercazolil and has limited lipophilicity, which hinders its penetration through biological membranes such as the placenta and mammary gland epithelium.

- Clinical improvement in treatment with thionamides appears already by the end of the 1st week of therapy, and euthyroidism is achieved after 4-6 weeks. As a result of the well-known immunosuppressive effect of pregnancy, manifested by an increase in the number of T-suppressors and a decrease in the number of T-helpers, DTG during pregnancy tends to spontaneous remission. Knowledge of this feature of the course of thyrotoxicosis during pregnancy makes it possible to control the function of the thyroid gland of the mother with the help of relatively low initial and maintenance doses of thyreostatics. The drugs should be administered at the lowest possible initial dosage (no higher than 10-15 mg of mercazolil or 100 mg of propylthiouracil per day) with the transition to a maintenance dose (2.5 mg/day for mercazolil and 50 mg/day for propylthiouracil).

- Treatment according to the "block and replace" method with high doses of thionamides in combination with replacement therapy T 4 during pregnancy is contraindicated.

With this regimen T 4 only maintains euthyroidism in the mother, at the same time it can cause hypothyroidism in fetus, since high doses of thyreostatics, in contrast to T 4 , easily pass through the placenta.

With this regimen T 4 only maintains euthyroidism in the mother, at the same time it can cause hypothyroidism in fetus, since high doses of thyreostatics, in contrast to T 4 , easily pass through the placenta. - The use of p-adrenergic antagonists during pregnancy complicated by the development of thyrotoxicosis is undesirable, since they can cause a decrease in placental mass, intrauterine growth retardation, postnatal bradycardia and hypoglycemia, and also weaken the response to hypoxia, p-blockers can only be used for a short the period for preparation for surgical treatment or with the development of a thyrotoxic crisis.

- The optimal method for monitoring the effectiveness of the treatment of thyrotoxicosis during pregnancy is to determine the concentration of SvTz and SvT 4 in the blood. The levels of svT 4 and svT 3 in the blood serum of the mother during treatment with thyreostatics should be maintained at the upper limit of the norm in order to avoid hypothyroidism in the fetus.

Due to the physiological changes in TSH secretion during the various phases of pregnancy, the TSH blood level is not a reliable criterion for judging the adequacy of treatment. At the same time, a very high level of TSH indicates the development of drug-induced hypothyroidism and requires immediate withdrawal or reduction of the dose of thionamides. Recommended by a number of authors, ultrasound determination of the size of the thyroid gland of the fetus and the study of the level of TSH, T 3 T 4 in the blood of the fetus, unfortunately, is available only to a small circle of highly specialized medical institutions and cannot yet be widely used.

- If there is stable compensation in the last months of pregnancy, thyreostatic drugs can be canceled. At the same time, one should be aware of the frequent recurrence of thyrotoxicosis in the postpartum period.

- During lactation, thionamides may pass into breast milk, with mercazolil to a greater extent than propylthiouracil.

However, there is evidence that low doses of thionamides (up to 15 mg mercazolil and 150 mg propylthiouracil) taken by a woman while breastfeeding do not appear to affect the infant's thyroid function.

However, there is evidence that low doses of thionamides (up to 15 mg mercazolil and 150 mg propylthiouracil) taken by a woman while breastfeeding do not appear to affect the infant's thyroid function.

Why is it so important to treat thyrotoxicosis during pregnancy?

Pregnancy thyrotoxicosis increases the risk of stillbirth, preterm labor or preeclampsia. There is also an increase in the incidence of neonatal mortality and the likelihood of a child being born with a lack of body weight. Decompensated thyrotoxicosis can cause and aggravate cardiovascular insufficiency in the mother, as well as contribute to the development of a thyrotoxic crisis during labor pains and attempts.

It should be noted that the above complications are more often observed in the development of thyrotoxicosis during pregnancy than in the case of pregnancy in women with previously treated DTG. There is no doubt that adequate control and treatment of thyrotoxicosis in the mother are the main factor in improving the prognosis of pregnancy and childbirth.

Children born to mothers with decompensated DTG have an increased risk of congenital malformations and other fetal disorders (6%). At the same time, in children whose mothers during pregnancy were in a state of drug euthyroidism during treatment with methimazole, the frequency of fetal disorders is similar to that among children of healthy euthyroid mothers (< 1%).

There is no information in the literature about the teratogenic effects of propylthiouracil, while: methimazole is extremely rarely accompanied by a congenital malformation of the skin (aplasi cutis). Studies of the intellectual development of children exposed to thyreostatics during fetal development also did not reveal deviations from normal indicators.

All of these data suggest that untreated maternal thyrotoxicosis may cause congenital malformations of the fetus and other complications of pregnancy, and that the benefits of thyreostatic treatment outweigh any possible teratogenic effects associated with these drugs.

Infants whose mothers suffered from autoimmune thyrotoxicosis during pregnancy may develop fetal or neonatal hyperthyroidism:

Intrauterine thyrotoxicosis develops when the function of the mature thyroid gland of the fetus is stimulated by a large amount of immunoglobulins and maternal blood. This condition may develop only after about the 25th week of pregnancy. Fetal thyrotoxicosis can be established by measuring the heart rate (above 160 per minute), determining the level of TSH or integral TG level obtained by amniocentesis or cordocentesis, as well as ultrasound, which allows establish the presence of goiter in the fetus. The basis of the treatment of fetal thyrotoxicosis is its temporary administration of thyrostatic therapy to the mother, and the heart rate is reduced!!! fetus during treatment should be within 140 beats per minute. 9lasts 2-3 months, may be a placenta! passage of thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins. The clinical symptoms of neonatal thyrotoxicosis are tachycardia, hypersensitivity, growth retardation, increased bone age, goiter (not always), premature, craniostenosis, increased mortality and morbidity.

Neonatal hyperthyroidism requires the earliest and most active treatment with thionamides. Newborns are prescribed methimazole (0.5-1 mg / kg body weight per day) or propylthiouracil (5-10 mg / kg body weight per day) in 3 divided doses. It is possible to prescribe propranolol to slow down the heart rate and reduce catecholamine activity. In severe disease, a saturated solution of iodide (1 drop of solution per day for no more than 3 weeks) can be given to inhibit the release of previously synthesized triglycerides.

In severe cases, the addition of glucocorticoids is necessary, which, in addition to the general effect, also have the ability to block the conversion of T 4 vT 3 .

The most common causes of primary hypothyroidism in pregnant women are chronic autoimmune thyroiditis (AIT) and the condition after thyroid resection for DTG and various forms of goiter. Hypothyroidism due to AIT in most cases is detected and compensated before pregnancy, but sometimes its debut coincides with pregnancy.

In order to detect AIT during pregnancy, it is necessary to examine pregnant women with suspected thyroid dysfunction for the presence of antibodies to thyroglobulin and thyroid peroxidase in the blood serum.

As previously described, due to the immunosuppressive effects of pregnancy, previously diagnosed AIT may tend to remit during pregnancy with relapse in the postpartum period.

The most typical symptoms of hypothyroidism during pregnancy are weakness, increased dryness of the skin, fatigue and constipation, however, it should be remembered that these symptoms can also be manifestations of pregnancy itself in the absence of a decrease in thyroid function. The diagnosis of hypothyroidism during pregnancy is made on the basis of a decrease in the level of fT 4 and increased serum TSH levels.

The selection of an adequate dose of T 4 is carried out under the control of the level of TSH and sT 4 in the blood serum (100-150 mcg of T 4 per day). Until recently, it was believed that pregnant women with previously treated hypothyroidism do not need to increase the dose of T 4 on the basis that the increased need for thyroid hormones is compensated by an increase in their concentration in the blood serum and a decrease in the metabolic conversion of T 4 . However, it has now become clear that women suffering from hypothyroidism and receiving T 4 replacement therapy often need to increase the dose of T 4 during pregnancy.

Until recently, it was believed that pregnant women with previously treated hypothyroidism do not need to increase the dose of T 4 on the basis that the increased need for thyroid hormones is compensated by an increase in their concentration in the blood serum and a decrease in the metabolic conversion of T 4 . However, it has now become clear that women suffering from hypothyroidism and receiving T 4 replacement therapy often need to increase the dose of T 4 during pregnancy.

Probable reasons for the increase in the need for triglycerides during pregnancy can be both an increase in body weight with increasing gestational age, and adaptive regulation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid gland, as well as possible changes in peripheral metabolism T 4 due to the presence of feto-placental complex.

Inadequate treatment of maternal hypothyroidism can lead to pregnancy complications such as anemia, preeclampsia, placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, and cardiovascular dysfunction. In addition, in the fetus and neonate with congenital hypothyroidism, transplacental passage of maternal T 4 during early pregnancy may play a critical role in normal brain development.

In addition, in the fetus and neonate with congenital hypothyroidism, transplacental passage of maternal T 4 during early pregnancy may play a critical role in normal brain development.

Blocking antibodies to TSH receptors that cross the placenta to the fetus can cause fetal and neonatal hypothyroidism (similar to fetal and neonatal hyperthyroidism). It is important to note that children of mothers suffering from hypothyroidism with the presence of antibodies that block the TSH receptor have an increased risk of developing intrauterine or postpartum hypothyroidism, even if the mother reaches the euthyroid state after T replacement therapy 4 .

Fetal hypothyroidism is accompanied by intrauterine growth retardation, bradycardia, delayed development of ossification nuclei, as well as impaired development of the fetal central nervous system.