Induction versus natural labor

Natural Labour vs Induced Labour - 6 Main Differences

These days, it’s very common for parents-to-be to face an important decision: whether to induce labour or wait for labour to begin spontaneously.

An induction of labour is when labour is started artificially, usually with a synthetic form of oxytocin (Syntocinon or Pitocin).

Women and their partners should be aware that, for a low risk pregnancy, induction of labour introduces a number of risks to a potentially normal labour and birth.

Many parents are not aware of the reasons why waiting for labour to start without any interference is preferable, and beneficial, when there are no medical complications.

Unfortunately, it’s not as simple as having some medication and then having labour begin (and end) just as it would normally. The reality is actually very different.

Here are some of the many differences between a natural labour, which begins spontaneously, and one that is started artificially.

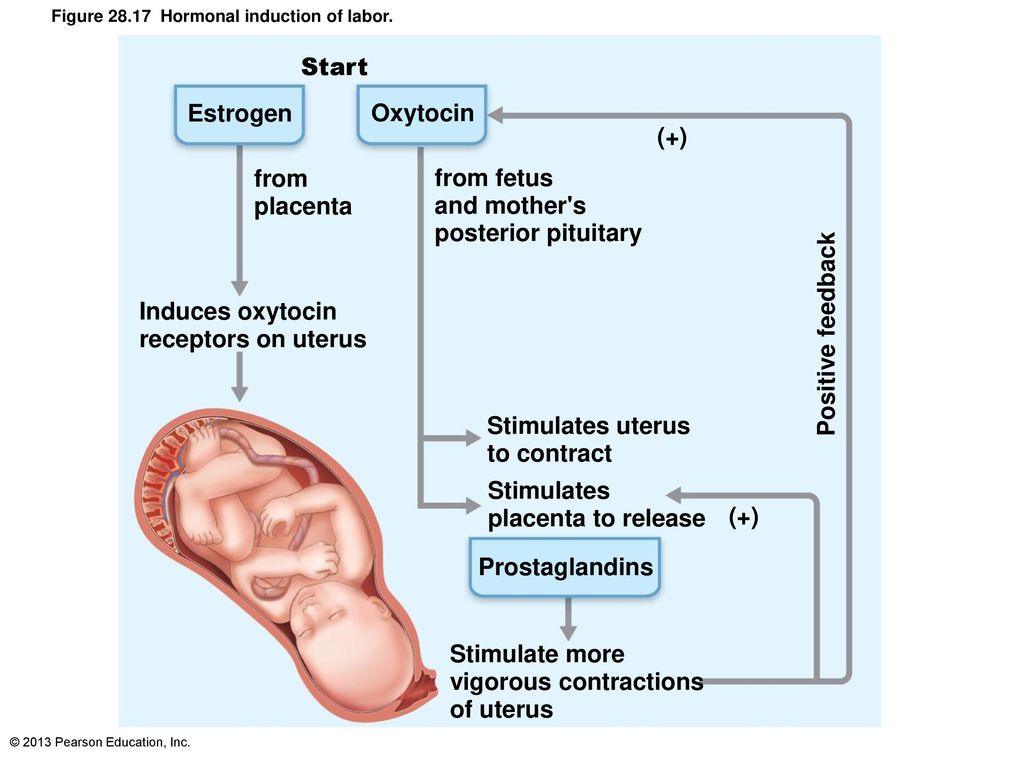

#1: Labour hormones work differently

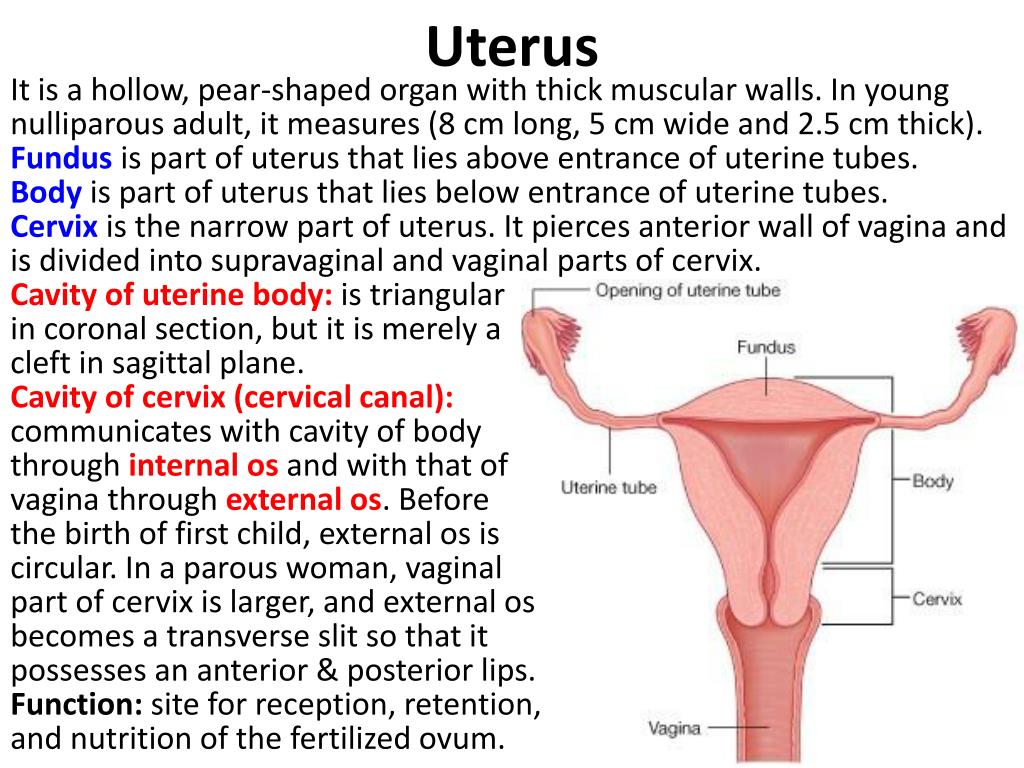

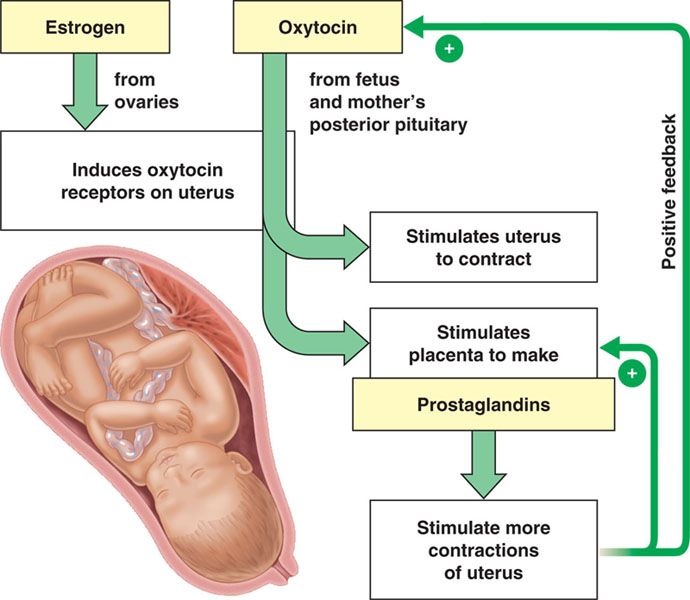

When you go into labour spontaneously, oxytocin is released to stimulate contractions in the uterus.

Oxytocin acts like a key to unlock the oxytocin receptors in your uterus.

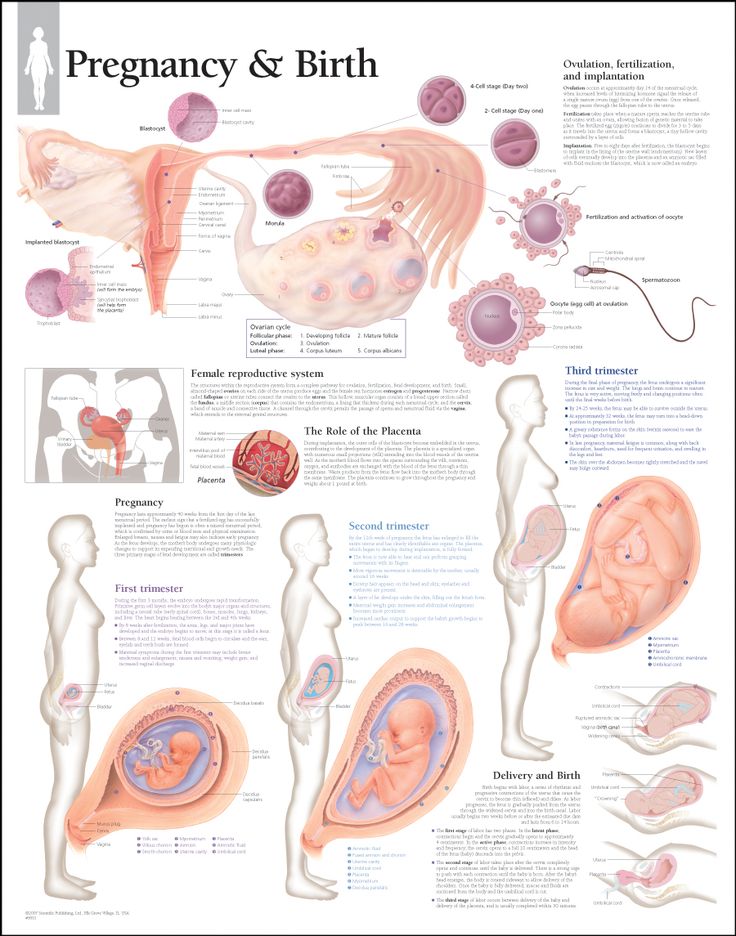

During the first and second trimesters of pregnancy, your uterus has few receptors, to protect you from going into labour too early.

As you reach full term, the number of receptors increases significantly.

Once labour begins, they are activated by the oxytocin in your bloodstream. Then they work effectively to contract the muscle and dilate the cervix.

The oxytocin is released in a pulsing action and comes in waves. This is so your uterus is not continuously contracting or having very strong contractions from the start.

Oxytocin levels also increase gradually. At the start of labour, contractions might come every 20-30 minutes, and last around 30 seconds.

As the tempo of labour increases, the contractions will get closer together (2-5 minutes apart) and longer (60-120 seconds in length).

This progression of natural labour usually happens over 10 or so hours, so that you have plenty of rest time between contractions, and your body is able to adjust to the intensity of contractions over time.

When you are induced, it’s likely to happen before your body and baby are ready.

This can mean there aren’t enough receptors available in your uterus, and so a large amount of synthetic oxytocin is required to start labour and to keep contractions going over time.

The artificial oxytocin level is increased until you are having 3-4 contractions in a 10 minute period. Each contraction should last 40-60 seconds, and there should be at least a minute between each contraction.

Syntocinon or Pitocin is given to you continuously, via an IV drip.

Your uterus goes literally from standstill to contracting ‘X’ number of times in an hour.

This means the contractions are very long and strong from the start, and your body doesn’t get a break.

And of course, once you hop on the induction train, you can’t get off or make it stop.

You’re now committed to getting your baby out, even if that means via c-section.

Here are 5 Things Oxytocin Does That Syntocinon/Pitocin Doesn’t.

Are You Getting BellyBelly’s Pregnancy Week By Week Updates?

We think they’re the best on the internet!

Click to get the FREE weekly updates our fans are RAVING about.

#2: Contraction pain is different

The main difference between a natural and artificially started labour is the intensity of the contractions.

In a natural labour, oxytocin works to stimulate your uterus to contract and dilate the cervix.

As the cervix stretches, pain receptors send messages to the brain, which responds by releasing endorphins.

This substance is ten times more powerful than morphine and acts to counteract the sensation of pain.

As oxytocin levels increase, more endorphins are released.

When labour is induced, the artificial oxytocin used to stimulate contractions does not cross the blood-brain barrier.

Your body doesn’t receive signals to release the endorphins and you experience more intense pain.

Natural labour usually begins slowly, with a gradual build-up of spaced out contractions that are short and mild.

Over time, these contractions get closer together, longer, and more intense.

During an induced labour, this can’t happen – the pain begins immediately.

Your brain can’t respond to the pain of these contractions and is not able to ‘be involved’ in the labour.

As a result, you’re more likely to request pain relief, such as an epidural.

#3: Movement during labour is different

In a natural labour, women usually seek out the positions and places in which they feel most comfortable.

During early labour, you might want to move during contractions, which helps your baby to find the optimal position for birth.

In late labour and in transition, you might seek the comfort of a warm bath or shower.

Your partner or birth support can support you during the pushing stage, encouraging your baby to move down and using gravity to assist.

During an induced labour, it is recommended that you have constant monitoring at the beginning, and then intermittent monitoring, unless there is an indication of fetal distress.

This is because the labour is now high risk. You will also have an IV drip attached. These limit your ability to move freely and work with your body, and your baby, during labour.

You are less likely to have access to a shower and won’t be able to use a birth pool to ease the pain of contractions. If you have an epidural in place (which is more likely with an induction of labour), you will be either lying on your side or sitting up in bed.

This increases the risk of fetal distress and the likelihood of a c-section.

Read about Everything You Need To Know About Having An Epidural.

#4: The fetal ejection reflex only occurs in natural labour

The fetal ejection reflex was first discovered by Niles Newton in the 1960s.

The reflex involves a powerful and uncontrollable urge to push as if the body has flicked a switch and is ready to ‘eject’ the baby.

In a natural labour, oxytocin levels increase steadily, culminating in a huge flood of the hormone when the cervix is dilated.

This oxytocin peak stimulates the powerful and irresistible contractions that push the baby down and out.

This is the fetal ejection reflex.

Adrenaline is also released at the same time, to provide you with the energy and alertness you need to birth your baby.

During an induced labour, this oxytocin peak doesn’t happen.

The synthetic oxytocin is provided by a pump and cannot be increased to offer this boost at the end of labour.

If you are induced with synthetic oxytocin or have an epidural during labour, you will not experience a fetal ejection reflex.

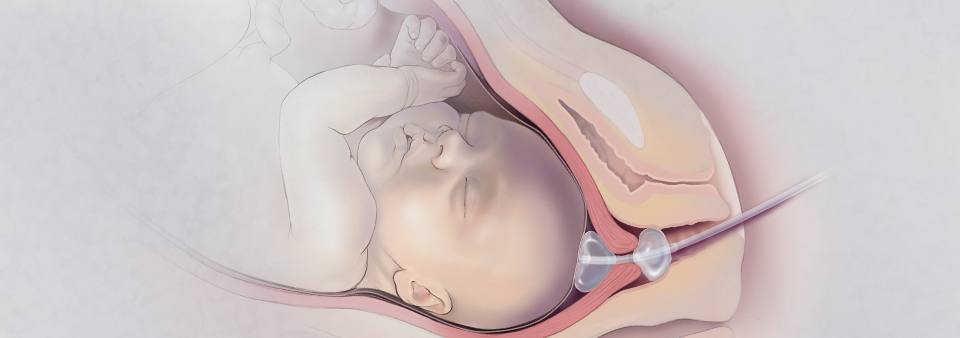

Women who have induced labours often require interventions at this stage of labour, such as ventouse or forceps (which also means an episiotomy), to help the baby be born.

#5: Natural oxytocin protects baby’s brain

In a natural labour, the oxytocin your body produces crossed the placenta.

The oxytocin ‘silences’ your baby’s brain during labour and protects it from damage that could occur due to oxygen deprivation.

As contractions begin slowly and build up, oxytocin levels also increase simultaneously.

This helps to keep your baby safe.

During an induced labour, the synthetic oxytocin interferes with your body’s ability to produce its own hormone.

Therefore your baby is much more likely to be exposed to hypoxia (oxygen deprivation) during an induced labour.

Your baby will respond to this situation by showing symptoms of distress.

The most notable is when the heart rate does not pick up sufficiently after contractions.

If this continues, your care provider will recommend an emergency c-section to avoid possible brain damage to your baby.

#6: The third stage of labour is different

When your baby is born after a natural labour, your body is on an oxytocin high.

In fact, you’ll never experience an oxytocin high like this in your life.

Oxytocin, the ‘hormone of love’, is responsible for promoting the bonding that happens between you and your baby.

This bonding is critical for your baby’s survival, but also has an important effect on your body.

As the empty uterus contracts down, the placenta sheers away from the uterine wall.

Exposed blood vessels are clamped, and any post-birth bleeding should be minimal.

In most cases, this happens without any interference from care providers.

It is called a physiological or natural third stage.

Many hospitals prefer to give women an injection of synthetic oxytocin as the baby is being born.

This speeds up the third stage, and potentially reduces the risk of excessive bleeding after birth (postpartum haemorrhage).

However, women who have experienced a spontaneous, undisturbed labour are less likely to require this injection, as their own bodies will produce oxytocin in large enough amounts.

If you have an induced labour, you will not experience that last boost of oxytocin naturally.

The empty uterus might not be able to contract down effectively, increasing the risk of postpartum haemorrhage (PPH).

The injection would most likely be necessary, at this stage, to avoid potential PPH. Find out more about how inductions increase the risk of PPH.

Synthetic oxytocin can affect bonding

Below is a clip from the world’s most famous Obstetrician, Michel Odent.

He explains how, in an induced labour, bonding behaviours in the mother are affected, because the mother is not releasing her own oxytocin.

Sadly, the number of women going into labour naturally is decreasing at an alarming rate.

A growing amount of research appears to confirm Odent’s long-held beliefs.

When synthetic oxytocin interferes with natural labour hormones, it can influence a mother’s stress, mood, and behaviour.

Coupled with plummeting rates of breastfeeding (another source of natural oxytocin), could this have anything to do with our high rates of postnatal depression and anxiety?

Having a positive, empowered induction of labour

If you need to have an induction of labour, it is still possible to be empowered and have a positive experience.

See our article 8 Tips For A Positive Induction Of Labour.

You might also like to read Why All Inductions Aren’t The Same – 5 Different Induction Methods.

…

If you are presented with the option of an induction of labour, you might want to ask your care provider whether it’s required for a genuine medical reason. Ask, for example, if there is proof in the form of a test or abnormal results. Or whether waiting, with patience, is the better answer.

Ask, for example, if there is proof in the form of a test or abnormal results. Or whether waiting, with patience, is the better answer.

Inducing labor at full term: What makes sense?

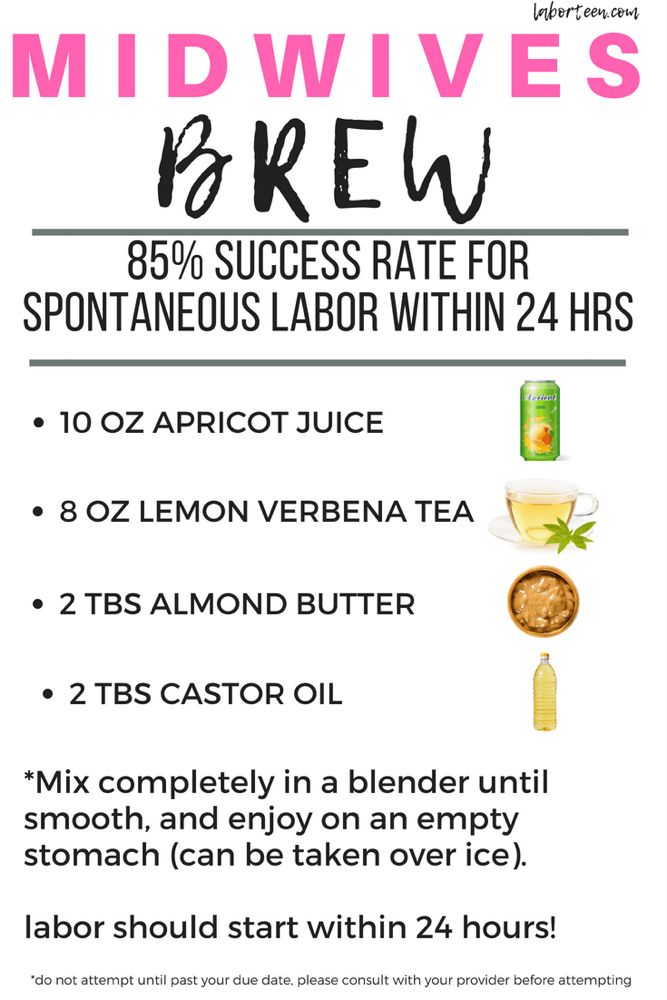

For generations, midwives and doctors have looked for ways to imitate human physiology and nudge women's bodies into giving birth. Synthetic hormones can be used to start and speed up labor. Soft balloons and seaweed sticks placed alongside the cervix can shape a pathway through the birth canal. Self-stimulation can spontaneously spark natural labor transmitters.

But the start of labor remains a complex and mysterious process. And part of this mystery is figuring out which women to induce, when to induce labor, and how. Now, a landmark study known as ARRIVE has brought a bit of clarity.

What does the study tell us about inducing labor?

This multicenter, randomized, controlled trial involving thousands of women compared outcomes of induced labor versus "expectant management" — just waiting for labor to begin. All participants in the study were expecting their first baby, and all were within one week of their due date. For most of the women, their cervix wasn't really open yet. No special methods were used to induce labor, just what was standard at each institution.

All participants in the study were expecting their first baby, and all were within one week of their due date. For most of the women, their cervix wasn't really open yet. No special methods were used to induce labor, just what was standard at each institution.

The results were interesting. For the baby, similar numbers of complications and need for intensive care occurred in both groups. However, when compared with waiting for labor, induction decreased the likelihood that the baby would need help with breathing. Breastfeeding success was no different between the two groups.

The big news? Inducing labor was associated with a lower rate of cesarean delivery (approximately 19% versus 22%).

What else is important to know?

It's worth pointing out that the overall rate of cesarean birth among women in the study is quite a bit lower than the national average. The study participants were also younger, more likely to be black or Hispanic, and more likely to have public insurance than the general population of women having their first baby. So these results would not apply to all women equally. Also, of all the patients who were initially eligible and asked to join the study, only about one-third chose to participate. It could be that women opting to participate in a study of induction of labor had a particular leaning that could skew the results. It also tells us that many women may not want to have labor induced. And, while the chance of cesarean was lower in the induced patients, labor took longer than it did for those women who waited for labor to kick in on its own.

So these results would not apply to all women equally. Also, of all the patients who were initially eligible and asked to join the study, only about one-third chose to participate. It could be that women opting to participate in a study of induction of labor had a particular leaning that could skew the results. It also tells us that many women may not want to have labor induced. And, while the chance of cesarean was lower in the induced patients, labor took longer than it did for those women who waited for labor to kick in on its own.

Doctors sometimes recommend inducing labor and birth for the benefit of the baby, mother, or both. Hypertensive diseases, including chronic high blood pressure and preeclampsia, are dangerous conditions that may require accelerated delivery. Over time, the health of the placenta that nourishes the fetus can deteriorate, leading to lack of growth and low amniotic fluid levels. When problems like these occur, inducing birth is appropriate. Other conditions — such as diabetes requiring insulin and, at times, the age of the mother — may be good reasons to induce. But even without a medical reason, the ARRIVE trial tells us it may actually be safer to induce labor in some women than to wait for labor to happen.

But even without a medical reason, the ARRIVE trial tells us it may actually be safer to induce labor in some women than to wait for labor to happen.

Should a woman choose to have labor induced?

So, should a woman choose to be induced? The answer may be yes if she is having her first baby, is not opposed to the idea of inducing labor, and is within one week of her due date. However, the benefits become less clear if her characteristics differ from those of the study participants in the ARRIVE trial. It's best for a woman to discuss the options with her health care team.

We also don't yet know how the longer labor and length of hospital stay associated with induction affect the cost of care. And most labor and delivery units are not built or staffed appropriately to accommodate the increase in occupancy that would result if many more first-time mothers were induced at full term. So, while the ARRIVE trial has answered some critical questions about inducing labor, some of the mystery remains.

Induction of labor in women with normal pregnancies of 37 weeks or more

Does a policy of inducing labor at 37 weeks or more of gestation reduce the risks for infants and their mothers compared with a policy of waiting until a later gestational age or until Will there be indications for labor induction?

This review was originally published in 2006 and subsequently updated in 2012 and 2018.

What is the problem?

The average pregnancy lasts 40 weeks from the start of a woman's last menstrual period. Pregnancies lasting more than 42 weeks are described as "post-term" and therefore the woman and her doctor may decide to give birth by induction. Factors associated with postnatal pregnancy and delayed delivery include obesity, first birth, and maternal age over 30 years.

Why is this important?

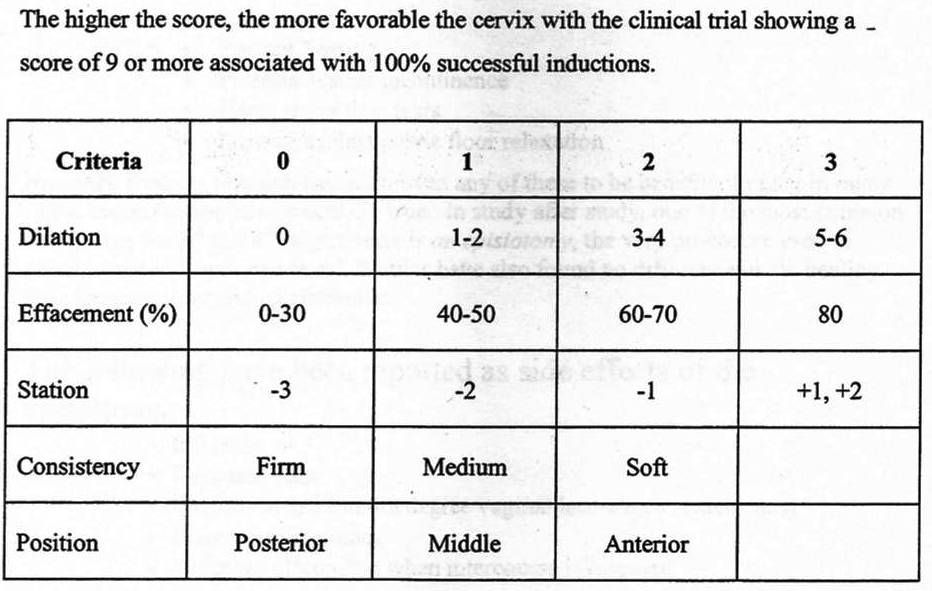

Protracted (term) pregnancy may increase risks for infants, including greater risk of death (before or shortly after birth). However, induction (stimulation or induction) of labor can also pose risks to mothers and their babies, especially if the woman's cervix is not ready for delivery. Current diagnostic methods cannot predict risks to babies or their mothers per se, and many hospitals have specific policies regarding how long a pregnancy can last.

However, induction (stimulation or induction) of labor can also pose risks to mothers and their babies, especially if the woman's cervix is not ready for delivery. Current diagnostic methods cannot predict risks to babies or their mothers per se, and many hospitals have specific policies regarding how long a pregnancy can last.

What evidence did we find?

We searched for evidence (July 17, 2019) and identified 34 randomized controlled trials in 16 different countries involving more than 21,500 women (mostly at low risk of complications). The trials compared a policy of induction of labor after 41 completed weeks of gestation (>287 days) with a policy of waiting (expectant management).

Labor induction policies were associated with fewer perinatal deaths (22 trials, 18 795 babies). Four perinatal deaths occurred in the induction policy group compared with 25 perinatal deaths in the expectant management group. Fewer stillbirths occurred in the induction group (22 trials, 18,795 infants): two in the induction group and 16 in the expectant management group.

Women in the induction of labor groups in the included studies were probably less likely to deliver by caesarean section than in the expectant management groups (31 studies, 21,030 women), and there was probably little or no difference when compared with assisted vaginal delivery (22 studies, 18,584 women).

Fewer infants were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in the induction policy group (17 trials, 17,826 infants; high-certainty evidence). A simple test of the baby's health status (Apgar score) at five minutes after birth was likely to be more favorable in the induction groups than expectant management (20 trials, 18,345 infants).

An induction policy may make little or no difference for women who have had a perineal injury, and likely has little or no effect on the number of women with postpartum hemorrhage or breastfeeding at hospital discharge. We are uncertain about the effect of induction or expectant management on length of stay in the maternity hospital due to the very low certainty of the evidence.

Among newborns, the number of children with trauma or encephalopathy was similar in both groups (moderate and low-certainty evidence, respectively). None of the studies reported the development of neurodevelopmental problems during follow-up of children and postpartum depression in women. Only three trials reported some measure of maternal satisfaction.

What does this mean?

An induction policy compared to expectant management is associated with fewer infant deaths and probably fewer caesarean sections; and probably has little or no effect on assisted vaginal delivery. Determining the best time to offer induction of labor to women at 37 weeks' gestation or more requires further study, as well as further study of women's risk profiles and their values and preferences. Discussing the risks of induction of labor, including benefits and harms, can help women make an informed choice between induction of labor, especially if the pregnancy lasts more than 41 weeks, or expectant management—waiting and/or waiting until labor is induced. Women's understanding of induction, procedures, their risks and benefits is important to influence their choice and satisfaction.

Women's understanding of induction, procedures, their risks and benefits is important to influence their choice and satisfaction.

Translation notes:

Translation: Alekseeva Lada Igorevna. Editing: Prosyukova Ksenia Olegovna and Ziganshina Lilia Evgenievna. Russian translation project coordination: Cochrane Russia - Cochrane Russia, Cochrane Geographic Group Associated to Cochrane Nordic. For questions related to this translation, please contact us at: [email protected]

Natural and induced labor: 6 main differences

Translation: Doula Lyubov Shraibman, Novosibirsk

Author: Sam McCulloch

Currently, many future parents are wondering - what is better: to induce labor with the help of induction or wait for their spontaneous onset? Induced labor begins before the onset of spontaneous labor - usually with the introduction of a synthetic form of oxytocin. However, in a low-risk pregnancy, this can provoke a number of complications both in the birth itself and for the newborn baby. Many parents simply do not know why waiting for labor to begin on their own is preferable. Unfortunately, this is not an obvious difference: there are labors that begin with the introduction of drugs and labors that begin (and end) on their own - in fact, these processes are very different. Here are just a few of the many differences between spontaneous labor and those that are artificially induced.

Many parents simply do not know why waiting for labor to begin on their own is preferable. Unfortunately, this is not an obvious difference: there are labors that begin with the introduction of drugs and labors that begin (and end) on their own - in fact, these processes are very different. Here are just a few of the many differences between spontaneous labor and those that are artificially induced.

# 1: The same birth hormones work differently

When labor begins spontaneously, oxytocin is secreted to stimulate contractions. Oxytocin acts as a key to unlock certain receptors in the uterus. During the first and second trimesters of pregnancy, there are only a few of these receptors in the uterus, which protects you from an early onset of labor. By the end of pregnancy, the number of receptors increases significantly. And when labor begins, they are activated under the influence of oxytocin in the blood, causing the uterus to contract effectively and the cervix to dilate. Oxytocin is secreted and released in waves, so that the contraction of the uterus is not constant, and strong contractions do not begin immediately. The level of oxytocin also increases gradually, so that at the beginning of labor, contractions can be every 20-30 minutes, lasting about 30 seconds. As the labor progresses, the intervals between contractions become shorter (from 2 to 5 minutes), and their duration increases (up to 60-120 seconds). This progression of natural childbirth usually lasts about 10 hours, so usually at the beginning of labor a woman has enough time to rest between contractions and the body has time to adapt to the intensity of uterine contractions. Induced labor begins before the uterus and baby are ready for it. At this time, the uterus does not yet have a sufficient number of receptors, which means that more synthetic oxytocin will be required - both for the onset of labor and for the progression of contractions. Doctors will increase the level of artificial oxytocin until the frequency of contractions reaches 3-4 in a 10-minute period.

Oxytocin is secreted and released in waves, so that the contraction of the uterus is not constant, and strong contractions do not begin immediately. The level of oxytocin also increases gradually, so that at the beginning of labor, contractions can be every 20-30 minutes, lasting about 30 seconds. As the labor progresses, the intervals between contractions become shorter (from 2 to 5 minutes), and their duration increases (up to 60-120 seconds). This progression of natural childbirth usually lasts about 10 hours, so usually at the beginning of labor a woman has enough time to rest between contractions and the body has time to adapt to the intensity of uterine contractions. Induced labor begins before the uterus and baby are ready for it. At this time, the uterus does not yet have a sufficient number of receptors, which means that more synthetic oxytocin will be required - both for the onset of labor and for the progression of contractions. Doctors will increase the level of artificial oxytocin until the frequency of contractions reaches 3-4 in a 10-minute period. In addition, each contraction should last 40-60 seconds, with minute intervals between them. Synthetic oxytocin during induced labor is administered intravenously by drip, in a continuous mode. As a result, the uterus, which was at rest, immediately goes into the mode of several contractions per hour. This means that the contractions will be very long and strong from the very beginning, and the body will have no time to rest. And of course, once you've jumped on the induction train, you can't get off it or make it stop. By agreeing to induction, you are agreeing that the baby will be born soon, even if this requires a caesarean section.

In addition, each contraction should last 40-60 seconds, with minute intervals between them. Synthetic oxytocin during induced labor is administered intravenously by drip, in a continuous mode. As a result, the uterus, which was at rest, immediately goes into the mode of several contractions per hour. This means that the contractions will be very long and strong from the very beginning, and the body will have no time to rest. And of course, once you've jumped on the induction train, you can't get off it or make it stop. By agreeing to induction, you are agreeing that the baby will be born soon, even if this requires a caesarean section.

# 2: Pain during contractions is perceived and experienced differently

The main difference between natural and induced labor is the intensity of uterine contractions. In natural childbirth, oxytocin causes the uterus to contract and the cervix to dilate. As the cervix opens, pain receptors send signals to the brain, and it responds by releasing endorphins. This substance is ten times more powerful than morphine and neutralizes the sensation of pain. The higher the level of oxytocin, the more endorphin will be released. However, the synthetic oxytocin used in induced labor does not cross the blood-brain barrier. The body will not know that endorphins are required and the sensation of pain will be more intense. Natural labor usually begins slowly, with long intervals between contractions, and the contractions themselves are short and mild at the very beginning. Over time, the contractions become more frequent and longer, becoming more intense. But such a scenario is impossible with induced labor - severe pain begins immediately. At the same time, the brain does not respond to this pain and is not able to participate in childbirth, releasing endorphins. And most likely, to relieve pain, you may need something instead of endorphins - for example, an epidural anesthesia.

This substance is ten times more powerful than morphine and neutralizes the sensation of pain. The higher the level of oxytocin, the more endorphin will be released. However, the synthetic oxytocin used in induced labor does not cross the blood-brain barrier. The body will not know that endorphins are required and the sensation of pain will be more intense. Natural labor usually begins slowly, with long intervals between contractions, and the contractions themselves are short and mild at the very beginning. Over time, the contractions become more frequent and longer, becoming more intense. But such a scenario is impossible with induced labor - severe pain begins immediately. At the same time, the brain does not respond to this pain and is not able to participate in childbirth, releasing endorphins. And most likely, to relieve pain, you may need something instead of endorphins - for example, an epidural anesthesia.

# 3: Different birth behavior

During natural childbirth, women seek and find positions and positions in which they feel most comfortable. At the very beginning of labor, some women prefer to move during contractions, helping the baby to get into the optimal position for birth. At the end of the first stage of labor and during the transition phase, a woman may need the comfort of a warm bath or shower. Then a partner or doula can become a physical support during pushing, helping the baby move through the birth canal with the help of gravity. Induced labor requires constant monitoring of the fetus - usually with the help of CTG. Oxytocin is administered through a drip, which limits a woman's ability to move freely and be in contact with her body and baby during labor. Most likely, using a shower and a pool to relieve labor pain in induced labor will not work. With an epidural, the woman can either lie on her side or sit up in bed. This, in turn, increases the risk of fetal distress and increases the likelihood of a caesarean section.

At the very beginning of labor, some women prefer to move during contractions, helping the baby to get into the optimal position for birth. At the end of the first stage of labor and during the transition phase, a woman may need the comfort of a warm bath or shower. Then a partner or doula can become a physical support during pushing, helping the baby move through the birth canal with the help of gravity. Induced labor requires constant monitoring of the fetus - usually with the help of CTG. Oxytocin is administered through a drip, which limits a woman's ability to move freely and be in contact with her body and baby during labor. Most likely, using a shower and a pool to relieve labor pain in induced labor will not work. With an epidural, the woman can either lie on her side or sit up in bed. This, in turn, increases the risk of fetal distress and increases the likelihood of a caesarean section.

# 4: Fetal ejection reflex

The fetal ejection reflex was first described by Niles Newton in the 1960s. The fetal ejection reflex is a powerful and uncontrollable desire to push, as if a switch has been flipped in the body, and it is ready to "push" the child. In natural childbirth, the level of oxytocin constantly increases, reaching peak values when the cervix is fully dilated. This surge of oxytocin causes powerful and irresistible uterine contractions that push the baby down and out - this is the fetal ejection reflex. At this time, adrenaline is also released, which provides a woman with energy and stimulates the increased attention that is needed when a child is born. There is no oxytocin peak in induced labor. Synthetic oxytocin enters the body through a dropper, at the same rate, and at the end of contractions, its concentration does not increase. It is almost impossible to experience the fetal ejection reflex in labor with synthetic oxytocin or epidural anesthesia. Therefore, often induced labor requires additional intervention at the stage of pushing, such as a vacuum extractor or forceps (which also means an episiotomy).

The fetal ejection reflex is a powerful and uncontrollable desire to push, as if a switch has been flipped in the body, and it is ready to "push" the child. In natural childbirth, the level of oxytocin constantly increases, reaching peak values when the cervix is fully dilated. This surge of oxytocin causes powerful and irresistible uterine contractions that push the baby down and out - this is the fetal ejection reflex. At this time, adrenaline is also released, which provides a woman with energy and stimulates the increased attention that is needed when a child is born. There is no oxytocin peak in induced labor. Synthetic oxytocin enters the body through a dropper, at the same rate, and at the end of contractions, its concentration does not increase. It is almost impossible to experience the fetal ejection reflex in labor with synthetic oxytocin or epidural anesthesia. Therefore, often induced labor requires additional intervention at the stage of pushing, such as a vacuum extractor or forceps (which also means an episiotomy).

# 5: Endogenous oxytocin protects the child's brain from hypoxia

When labor begins on its own, endogenous oxytocin crosses the placenta to the baby. This oxytocin "calms" the baby's brain during contractions and protects it from damage that can result from a lack of oxygen. Oxytocin levels rise at the same time as labor starts, which helps protect the baby's brain. In induced labor, synthetic oxytocin interferes with the female body's ability to produce its own, endogenous oxytocin. Therefore, in induced labor, it is more likely that the child may suffer from hypoxia. The baby may develop symptoms of distress - most often insufficient recovery of the child's heart rhythm after a contraction is detected. If these symptoms are present, an emergency caesarean section may be required to avoid possible damage to the baby's brain.

# 6: Differences in the third stage of labor

When a child is born as a result of natural childbirth, oxytocin fills the entire body - in fact, such a high level of this hormone will never be repeated in a lifetime. The love hormone oxytocin is responsible for the formation of bonding - this is a special form of attachment that occurs between mother and baby. The survival of the child directly depends on the strength of this attachment, but it also has a significant impact on the female body. As the empty uterus contracts and descends, the placenta separates from the walls of the uterus. Blood vessels contract and postpartum bleeding is minimal. In most cases, this happens without any intervention from the medical staff and is called the physiological course of the third stage of labor. Many hospitals prefer to give women injections of synthetic oxytocin immediately after the baby is born, to speed up the third period and reduce the risk of postpartum hemorrhage. However, women who give birth spontaneously do not usually need such injections because their own bodies produce oxytocin in large quantities. In induced labor, this oxytocin peak may not be present immediately after the birth of the baby.

The love hormone oxytocin is responsible for the formation of bonding - this is a special form of attachment that occurs between mother and baby. The survival of the child directly depends on the strength of this attachment, but it also has a significant impact on the female body. As the empty uterus contracts and descends, the placenta separates from the walls of the uterus. Blood vessels contract and postpartum bleeding is minimal. In most cases, this happens without any intervention from the medical staff and is called the physiological course of the third stage of labor. Many hospitals prefer to give women injections of synthetic oxytocin immediately after the baby is born, to speed up the third period and reduce the risk of postpartum hemorrhage. However, women who give birth spontaneously do not usually need such injections because their own bodies produce oxytocin in large quantities. In induced labor, this oxytocin peak may not be present immediately after the birth of the baby. An empty uterus may not contract as efficiently, increasing the risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Thus, in the third stage of induced labor, oxytocin may indeed be required to prevent postpartum hemorrhage.

An empty uterus may not contract as efficiently, increasing the risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Thus, in the third stage of induced labor, oxytocin may indeed be required to prevent postpartum hemorrhage.

How to have a positive experience with induced labor?

If for some reason you need induction of labor, you can try to make this experience positive. Ask your doctor - is induction required for medical reasons and is there evidence for this in the form of tests or test results? Or is patiently waiting for the spontaneous onset of labor to be the best solution? It is difficult to compare natural and induced labor, because what happens depends on many factors, and there is no guarantee that the simplest choice is the right one. The best thing you can do is to make sure that you have considered all the possible risks, and that you make a choice carefully and judiciously, and not because it is more convenient. Links to sources: Comparison of maternal and neonatal outcomes in induced labor: https://www.