How to restrain a child in school

Inside a Training Course Where School Workers Learn How to Physically Restrain Students — ProPublica

This week’s ProPublica Illinois newsletter is written by Jennifer Smith Richards, a Chicago Tribune reporter who has been working with ProPublica Illinois reporters Jodi S. Cohen and Lakeidra Chavis to investigate the use of seclusion and restraint in Illinois public schools.

In the year that we’ve reported on restraint and seclusion, we have worked hard to become experts on the topic.

We’re not educators, but we are dedicated learners. We read books and studies about how to work with children who have behavior disorders, and we talked to academic experts and researchers across the country about seclusion, or confining students in a place they can’t leave, and physical restraint. We learned by observing, too. ProPublica Illinois reporting fellow Lakeidra Chavis and I spent two days watching a Crisis Prevention Institute, or CPI, training for educators in the Chicago suburbs.

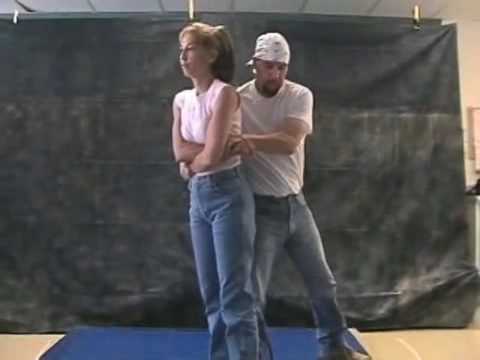

We saw school workers learn about verbal de-escalation and how to safely break free if a student grabs their hair or bites them. We saw how a CPI trainer walked them through standing and seated restraints and how to decide what type to use.

Get the Weekly Dispatch from ProPublica

A weekly breakdown of what our newsroom’s been working on.

Email address

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.But we wanted to learn by doing, too. So I asked my editors at the Chicago Tribune to send me to a five-day training in Peoria last March. They agreed that this would help me better understand what school employees are supposed to do during a crisis. The state currently requires school workers who use physical restraint to be trained at least once every two years and to be taught alternatives to restraint, including de-escalation techniques.

Therapeutic Crisis Intervention, a Cornell University-based program, did not want an observer in the small session but agreed to allow one of us to participate.

So I signed up.

I learned about how children cycle through a crisis and how to help them calm down when upset, and I practiced how to stand in a nonthreatening way. I acted out scenarios with the other class members, playing the role of the compassionate adult and then the irate child.

And then, when it was time to practice physical restraints, the trainers leading the class pulled out mats.

Four Ways Students are Restrained

The crisis-management systems commonly used in schools train employees in how to physically control students who pose a danger to themselves or others. Standing and seated restraints are typically taught; some systems also include restraints that take place on the floor.

The trainees got paired up to go through the motions of restraining a child: standing, sitting, how to do a “takedown” to the floor. Everyone else there had taken TCI courses before, knew the material and was preparing to teach the methods back at the residential facilities, psychiatric hospitals and schools where they worked.

I was the new student, which meant I had a lot of catching up to do. I spent the evenings studying in my hotel room.

The seriousness with which the trainers and the participants approached the physical training has stayed with me. The trainers began by issuing some dire warnings: Restraints gone wrong can be deadly. You should never restrain a child when your emotions aren’t in check. And do not deviate from the techniques being taught — the safety of the worker and the child depends on doing them correctly.

The participants went through most of the motions in silence. You could have heard a pin drop. I found myself holding my breath.

Having read the details of thousands of restraints that had taken place in Illinois public schools, seeing versions of those holds happen step-by-step in slow motion — with a willing adult, not a child, as the person being restrained — brought a critical point into focus for me: Restraint is intense. Forceful. Physically taxing. A child is being controlled with adult bodies.

At the end of the training, we took a written test on the material and then performed a graded role-playing scenario in which we had to pretend to debrief with a child after a crisis. (Yes, I passed both the test and the role-playing exercise.)

I’m not going to apply the training in my job, of course. But it was important for me to be there. When it came time for us to write about how schools in Illinois were using physical restraint, we understood those techniques, how they are taught, what it feels like — at least a little — to use them.

But it was important for me to be there. When it came time for us to write about how schools in Illinois were using physical restraint, we understood those techniques, how they are taught, what it feels like — at least a little — to use them.

That insight helped us to answer this question as we analyzed 50,000 pages of incident reports to write the project: Did the workers do what they’d been taught?

In so many cases, the answer was no. The training made it clear that physical restraint should be used only in a safety emergency, but we documented thousands of times when school employees restrained children for inappropriate reasons.

When students refused to come in from the playground or balked at putting away a toy from home, staff members used restraint to control them. I thought back to the warnings the trainers had issued against performing restraint when you’re angry or frustrated. I thought back to those moments on the mats when the trainees were holding down arms and legs and how, even when the person being restrained offered no resistance, the act felt so visceral, so invasive.

I thought back to those moments on the mats when the trainees were holding down arms and legs and how, even when the person being restrained offered no resistance, the act felt so visceral, so invasive.

Even before we published our story on physical restraint, Illinois schools had begun to change their practices in response to our reporting. As part of emergency actions the Illinois State Board of Education took the day after we published our initial story about seclusion, the agency restricted the types of restraint that could be used. Permanent rules are in the works now.

We’ll continue to report on what’s happening. Thanks for reading — and learning — with us.

To tell us about seclusion or restraint practices at your child’s school, email us.

Read More

Here's What You Need to Know About Restraint and Seclusion In Schools : NPR

LA Johnson/NPR

When students pose a threat to themselves or others, educators sometimes need to restrain them or remove them to a separate space. That's supposed to be a last resort, and it's a controversial practice. As we've reported recently, school districts don't always follow state laws or federal reporting requirements.

That's supposed to be a last resort, and it's a controversial practice. As we've reported recently, school districts don't always follow state laws or federal reporting requirements.

Though there are guidelines around restraint and seclusion in schools, there are no federal laws governing how they can be used. And they're most often used on students with disabilities or special needs, and boys, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

Jennifer Tidd's son falls into both those categories. He has autism and behavioral issues, and over three years — from 2013 to 2016 — he was restrained or secluded more than 400 times by his Fairfax County, Va., school, according to an investigation by member station WAMU. Tidd says the repeated seclusions traumatized her son, causing him to hate school and making him more violent and distrusting of authority figures.

"He would poop and pee himself to get out of the seclusion room — he was so desperate to get out," she recalls. "This is a child who was completely potty trained since he was 5. ... That to me, for a nonverbal person, that's absolute desperation."

"This is a child who was completely potty trained since he was 5. ... That to me, for a nonverbal person, that's absolute desperation."

These practices are covered by a patchwork of policies, guidelines and regulations that differ from school district to school district. That can make it difficult to understand when, why and how often students are secluded and restrained.

Often, educators told WAMU, they don't want to seclude and restrain students, but when students become a danger to themselves, other students or teachers, many feel like they don't have other options. Some educators have reported experiencing significant injuries on the job as a result of violent student behaviors.

Here's what we know about how these methods are used, and how they're regulated:

What does "seclusion and restraint" mean?

Restraint means to restrict a student's movement by holding them, by using a device to keep them still (straps, for example), or through medication. Physical restraint can mean anything from holding a child's arm to pulling their whole body down.

Physical restraint can mean anything from holding a child's arm to pulling their whole body down.

Seclusion means to isolate a student in a room or space that they're physically prevented from leaving. Seclusion spaces and rooms vary between schools and districts. Some schools have makeshift spaces that operate like time-out corners. Usually, the student is not completely enclosed in those spaces and people can easily see in and out.

Other schools have separate seclusion rooms. Some seclusion rooms in Fairfax County, for example, are built like Russian nesting dolls — rooms within rooms. The innermost room is reserved for students with more egregious behavior issues. That room is concrete and about the size of a closet. Inside, there are no chairs to sit on and no windows on the walls. The doors have small windows and large magnetic locks.

How seclusion and restraint are regulated

The U.S. Department of Education's Office for Civil Rights requires that school districts report every time a student is restrained or secluded. And while tens of thousands of cases are reported, many suspect those numbers fall short.

And while tens of thousands of cases are reported, many suspect those numbers fall short.

According to an Education Week analysis of data from the 2013-14 school year, nearly 80% of districts reported that they never secluded or restrained special education students. That number includes New York City, the nation's largest school district.

For years, Fairfax County Public Schools also told the government that it never secluded or restrained students. But the WAMU investigation found hundreds of cases recorded in internal documents and letters that schools sent to parents.

The Government Accountability Office, a federal watchdog, is conducting an investigation into the quality of the data that school districts are reporting. Jackie Nowicki, a director at the GAO, says media accounts and testimony from lawmakers have raised "concerns that seclusion and restraint [have] continued to be chronically underreported."

At the state level, regulation varies widely.

A law in Washington state calls for schools to follow up with parents after a student is restrained or secluded, to "address the behavior that precipitated the restraint or isolation and [review] the incident with the staff member who administered the restraint or isolation. "

"

Colorado requires that school districts conduct an annual review of every incident from the preceding year. And Michigan has banned the use of mechanical and chemical restraints in schools.

Other state laws are much less specific. In Virginia, a recently passed measure simply requires that the state Board of Education develop regulations around restraint and seclusion that are consistent with federal guidelines. Some states only govern the use of seclusion and restraint for students with special needs, and many do not have reporting requirements.

What are the alternatives to restraint and seclusion?

Restraint and seclusion can take a toll on students. Oregon Public Broadcasting's Rob Manning told the story of a Vancouver, Wash., student who was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder after repeated restraints and seclusions.

Students and educators can also be injured, and in a few tragic cases, students have even died. That's what happened at a school run by Grafton Integrated Health Network, a Virginia-based nonprofit that manages private schools and adult group homes for people with disabilities and behavioral issues.

In December 2004, a 13-year-old student with autism died while being restrained at a Grafton facility. Now, the organization uses a trauma-informed care approach that doesn't rely on seclusion or restraint.

"The whole idea is when someone is at their worst, we need to be at our best," says Kim Sanders, who has worked at Grafton for 30 years.

According to Sanders, in 2003, the year before the student died, Grafton served about 220 children and adults but had more than 6,600 incidents of restraint and about 1,500 instances of seclusion.

"Our toolbox was full of restraint and seclusion. That was sort of the go-to technique that we used," Sanders says.

Now, teachers are coached to empathize with students and think about what someone would need if they were having a bad day.

"Most people would say [they need] space, someone to be kind to me, maybe to read a book ... go for a walk," Sanders says. "No one is going to say, 'Well actually, I need someone to hold me against my will or lock me in a room by myself. ' That's not what any of us would want."

' That's not what any of us would want."

Grafton's method also requires teachers to learn about students' patterns of behavior and learning styles to help individualize their approaches to education.

According to Sanders, in the last five years, the organization has greatly reduced its use of seclusion and restraint.

The Education Department has been funding the development of a program called Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, or PBIS. It's a framework designed to help schools improve educational outcomes for students with disabilities and emotional and behavioral disorders. According to George Sugai, one of PBIS's senior advisors, the program provides strategies that are designed to reduce the need for restraint and seclusion.

Sugai, who's an emeritus professor of special education at the University of Connecticut, also says it's important to note that seclusion and restraint shouldn't be used as the sole intervention for students with challenging behavior. Instead, he encourages teachers to seek more therapeutic responses to students, such as having conversations about why they behaved in certain ways.

Instead, he encourages teachers to seek more therapeutic responses to students, such as having conversations about why they behaved in certain ways.

Sugai explains this with an example: "When I work with a school and they say, 'Oh, my gosh [a student] has been in the office 17 times and we have had to restrain [the student] 14 times,' I say, 'Well, what interventions do you have in place,' " to help them understand their anger?

Sugai says many schools don't have alternatives in place to prevent behaviors that result in the use of seclusion and restraint, and many lack alternative interventions. This is something his organization is hoping to change.

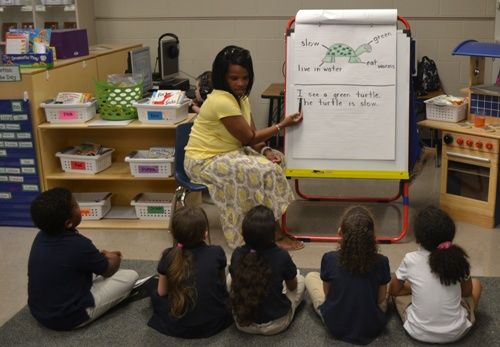

How to keep a child interested in learning after school

One of the most difficult tasks for parents these days is getting their children to do their homework. Over the past few years, the learning process has completely changed: today, teachers give homework, stimulating creativity in their implementation. Now, homework is not a question-and-answer task, it stimulates conceptual and analytical thinking. Also today there are many distractions. So this balance is quite fragile! Another important aspect is that the tasks are often complicated and children need the help of parents or teachers to complete them.

Also today there are many distractions. So this balance is quite fragile! Another important aspect is that the tasks are often complicated and children need the help of parents or teachers to complete them.

Thus, it is very important that parents play a significant role in supervising their children's homework. It should also be noted that children remember more when they work conscientiously on homework, because this is a repetition, which means consolidating the material studied in class. Moreover, with the active participation of parents in doing homework for children, this becomes an interesting game.

An important task for every parent is to ensure that children have a sincere interest in doing homework. If not, then why not? Check out tips on how to get your kids interested in doing homework and improve their academic performance.

Give the kids some rest after school

Children need time to relax because they spend all day reading books. They are already tired and forcing them to read books again will only lead to hatred towards them. You should give the children some time to rest before doing homework. Let them play for a while, watch TV, or do something constructive for relaxation and a change of scenery before doing their homework. In case homeschooling you can schedule classes, with rest intervals, according to the school plan.

You should give the children some time to rest before doing homework. Let them play for a while, watch TV, or do something constructive for relaxation and a change of scenery before doing their homework. In case homeschooling you can schedule classes, with rest intervals, according to the school plan.

Give children a comfortable place to do homework

Children do not have to do homework at the table all the time - they get bored much earlier than parents think, and therefore it is important to keep their interest. Let the children choose their own place. Let them feel comfortable while doing their homework. If you have chosen a private tutor, make sure that the child and the tutor will be given a separate room for study, assignments and homework.

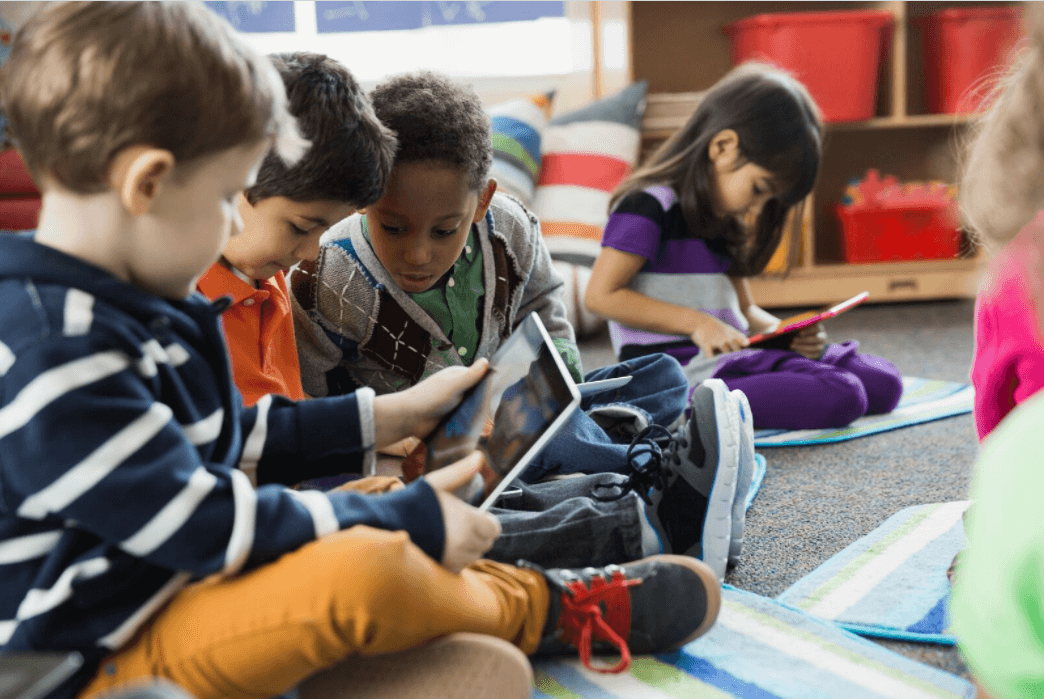

Working with electronic devices

Technology has changed our lives for the better. As a result, students are often assigned homework that requires the use of the Internet, resulting in the need to use computers and tablets. Instead of looking for solutions to problems, you can let your children control their devices and only help them find solutions to homework problems. This makes homework more interesting and allows children to gain additional knowledge. Please note that you must constantly monitor your children's computer usage.

Instead of looking for solutions to problems, you can let your children control their devices and only help them find solutions to homework problems. This makes homework more interesting and allows children to gain additional knowledge. Please note that you must constantly monitor your children's computer usage.

Homework deadlines

You must set homework deadlines for your children so they can follow them and do their homework ahead of time. There may be exceptions, but make sure the kids stick to the deadlines. Homework time has a significant impact on children. If the time frame is too vague, then the children will quickly get tired and bored. For young children, homework should be no more than half an hour, depending on the child. If homework is expected to take longer, talk to teachers so kids don't hate doing homework because it's too much.

Find the perfect time to do homework

Some children are active in the evening, while others work faster towards the night. As a parent, you should determine the ideal time for doing homework. If the child is not active in the evening, doing homework will not interest him and it will take more time to complete it. Even when hiring a private tutor, make sure that the classes take place at the most appropriate time.

As a parent, you should determine the ideal time for doing homework. If the child is not active in the evening, doing homework will not interest him and it will take more time to complete it. Even when hiring a private tutor, make sure that the classes take place at the most appropriate time.

By following these tips, children will be motivated to do their homework and improve their school performance. Since doing homework is important for all children, make sure your child is interested in doing it and is applying the information learned in school.

By following these simple tips, you can improve your children's learning and help them learn anything faster .

3 working cases from the teacher's practice

Oh, how many on-duty phrases teachers have when they make remarks to those guys from the back. “So, Kamchatka, listen carefully!” and the like. And those in Kamchatka would have listened more attentively, but only they are busy eating food or drinking Baikal soda, or something like that. And in the deathly working silence of the class, you can hear the creak of lightning on the backpack, and after it the deafening rustle of an opening pack of chips follows.

And in the deathly working silence of the class, you can hear the creak of lightning on the backpack, and after it the deafening rustle of an opening pack of chips follows.

CONTENT:

Case #1. “Take administrative action or be treated like a human being?”

Case #2. “Create working pairs and distribute by class”

Case №3. “Put a strong and a weak child together”

In pedagogical practice, teachers quite often go to their colleagues’ lessons: gain experience, see what and how to present, be inspired and bring something that was not in the subject before. By the way, I will write about this, but in another article. As you might guess, there is no universal way to work with such groups, but we love to come up with moves, don't we? So let's take a look at specific ways to activate the attention of students together!

Case #1. “Take administrative action or be treated like a human being?”

I'm at an introductory lesson at a new school and get into a Russian class. I took a chair. And instead of sitting next to the lead teacher, I left for the last desks. Firstly, the review is no worse than in front. Secondly, you do not once again callus on the eyes of children, and at some point they forget about your presence, and become more natural.

I took a chair. And instead of sitting next to the lead teacher, I left for the last desks. Firstly, the review is no worse than in front. Secondly, you do not once again callus on the eyes of children, and at some point they forget about your presence, and become more natural.

So, the children received a task for 10 minutes: to write an essay on the topic “What if this is not true?”. Someone writes hard. Here are a couple of girls at the first desk trying to discuss something, but the teacher quickly interrupts them and reminds them that the work is individual. Here is a boy from the second desk of the third row trying to look up the spelling of a word in the dictionary from the last lesson, but he also fails, because he was caught red-handed.

What is the situation with those who sat at the back of the desk?

The last desk of the first row - a couple of guys are quietly fooling around, drawing some drawings and passing it forward. They also eat French fries with ketchup, even managed to make a small cup from bottle caps during their independent work. The boy behind the last desk of the central row reads a book and pulls out sweets from under the floor, which he successfully cracks. Two more guys at the back of the third row are playing dots.

The boy behind the last desk of the central row reads a book and pulls out sweets from under the floor, which he successfully cracks. Two more guys at the back of the third row are playing dots.

What's the problem here? How to keep students interested in the lesson? Are the kids not focused? Or are they not interested in the subject? Or are they malnourished during recess?

In fact, this issue needs to be sorted out in the second step.

The first action should be to respond to their "wrongdoing". If something is prohibited by the charter of the school, for example, then the reaction should be formal, for example, “you can’t eat in the classroom!”.

If there is no such strictness, then you can connect the "human factor": something like, "I understand that you are hungry, but it upsets me that ... (further in the sense)". Or: “if you didn’t have enough communication for a change, then I would ask you to leave, since your conversations PERSONALLY interfere with me” and send you to the corridor until the meal or conversation is completed.

I agree, it looks manipulative, but we need a lively reaction from the children. The mistake of the teacher in this case was to work only with the visible group - the one that was in his field of vision, and the focus of the lesson was focused on the children of the first two or three rows.

How to expand this field and focus? There can be many methods here. The most effective is walking around the classroom when you give independent work. Children need to see that you are at any point in the class and at any time. Although you can come up with your own ways of organizing attention in the lesson, the main thing is to include all the children in the process and not forget about anyone.

Case #2. “Create work pairs and distribute to the class”

I had a situation in one of the classes in which I worked. Children 12-13 years old, seventh grade, and this group was the most dependent on phones. There is no longer such total control on the part of parents as before, but they have not yet developed the ability to stop in time. Phones, smart watches, tablets are becoming a very important and integral part of their lives.

Phones, smart watches, tablets are becoming a very important and integral part of their lives.

The boy sitting at the back of the desk constantly spent time on his phone or watch (what he did with them, I don't know anymore). At the same time, a neighbor on the desk was included in this. Both strongly dropped out of the process. And, if he had good inclinations, and he could quickly catch up, then for the girl this became a very serious problem.

What steps should be taken to keep students interested? This is a big question for discussion. At our school, it is customary to come up with not one, but several solutions and try until it works.

First, I replaced their desk with a blank wall for a desk without a wall. That is, now, when he lowered his hands with the phone under the desk, I could always see everything.

Here it is, victory, I thought, but children are just as inventors as adults. Then the military-sports game "who will outwit whom" began. Pencil cases with which he covered the phone, long-sleeved sweaters for smart watches, small headphones, hats and much more were used.

It dawned on me that this is all a consequence of another problem, the problem is that the child was simply not in the field of the lesson, and when you are not in the field, then you are looking for ways to entertain yourself or entertain yourself. Here's what I did to keep students engaged in class.

I made the decision to do a massive class transfer and see what happens. During the next 2-3 lessons, I singled out for myself active children who set the working atmosphere in the classroom. I got about 12.9 of them0003

Next, I formed pairs and distributed them evenly throughout the class. It turned out two pairs for each of the three rows, while the active guys sat at the last desks too. This helped me not only to keep the attention of the children in the lesson who were sitting in front, but also to those who were in the back, as they kept their hands outstretched.

Gradually distracted children (including the boy with gadgets) began to turn on. To enhance the effect of the children who bothered me the most, I sat closer to me in order to monitor all the notes and notes in their notebooks along the way. Three months later, the children pulled up the subject and the defocus became much less.

Three months later, the children pulled up the subject and the defocus became much less.

Another important thing: such groups should be mixed as soon as in some location you begin to notice stagnation or deterioration in the results. This is necessary for strong children as well.

If this is such an effective method, why isn't everyone using it?

There are several reasons:

- this requires enormous efforts from the teacher;

- the school should be allowed to seat children in the way that the subject teacher considers in his lessons;

- children need to know very well and follow their results in EVERY lesson.

Case #3. “Putting a strong and a weak child together”

My class is made up of children who have decided early enough on the path of development and areas that give them pleasure.

So, a few years ago, when they were in the 8th grade, many of them had problems with various subjects: T. stopped understanding what was happening in history lessons, N. could not understand the basics of chemistry, Y. encountered difficulties in algebra and geometry, and M. completely ceased to understand biology, and so on.

stopped understanding what was happening in history lessons, N. could not understand the basics of chemistry, Y. encountered difficulties in algebra and geometry, and M. completely ceased to understand biology, and so on.

I know my children very well, and it was not a matter of laziness or lack of attention, it was due to the fact that after the 7th, many subjects undergo qualitative changes in content and in how they should be taught at school.

Indeed, lagging children are nothing new. And at the next teachers' meeting, where teachers voiced questions about academic performance, our joint efforts came up with the following method: to highlight not only the weaknesses, but also the strengths of the child, because a child cannot be weak in all areas. Are there any among them who are good at at least one subject?

We got that the same T. was very strong in physics and chemistry, N. was strong in the humanities, Y. showed good results in biology, and M. already in the eighth grade was a strong mathematician and programmer. After that, as a class teacher, I collected all the information from myself and reduced it to a table in which the rows were occupied by children with their strong and weak subjects, and the columns were the subjects themselves.

After that, as a class teacher, I collected all the information from myself and reduced it to a table in which the rows were occupied by children with their strong and weak subjects, and the columns were the subjects themselves.

Further, at the intersections, I entered the name of the student who should be seated together with someone from the class during this lesson. The result was a table where Y. and M. sat together in biology and mathematics, T. and N. in physics and history also ended up at the same desk.

At the same time, teachers were given instructions that if specific children discuss a topic in class, then they should not be forbidden. Then T. helped N. draw out physics, N. helped T. deal with history, Y. helped M. with biology, and the latter, in turn, improved Y.'s results in algebra and geometry.

The work is scrupulous, and for its implementation it is necessary to observe children a lot, communicate with leading teachers about their progress, but this is what a class teacher is needed to help and improve the results of their students as much as possible.