How to raise an emotional child

3 Do’s and Don’ts for Raising Emotionally Intelligent Kids

With these three steps, you can raise children who are bright, confident, and better able to navigate the intricacies of life.

With these three steps, you can raise children who are bright, confident, and better able to navigate the intricacies of life.

With these three steps, you can raise children who are bright, confident, and better able to navigate the intricacies of life.

As parents, we want the very best for our kids. We work hard to raise strong individuals who will go on to lead happy lives and have good moral standing. Sometimes, however, we find ourselves questioning our parenting choices, crossing our fingers and hoping we’re doing this whole parenting thing right.

Our hopes, dreams, and fears about parenting will never cease, but as it turns out, we don’t have to wing it and rely on hope alone anymore. With Emotion Coaching we now have a science-based roadmap for how to raise well-balanced, higher achieving, and emotionally intelligent children.

Research by Dr. John Gottman shows that emotional awareness and the ability to manage feelings will determine how successful and happy our children are throughout life, even more than their IQ. Being an Emotion Coach to our kids has positive and long-lasting effects, providing a buffer for the complexities of life that allows them to be more confident, intelligent, and well-rounded individuals.

Below are three do’s and don’ts for building your child’s emotional intelligence.

1. Do recognize negative emotions as an opportunity to connect.

Use your child’s negative emotions as an opportunity to connect, heal, and grow. Children have a hard time controlling their emotions. Stay compassionate, loving, and kind. Communicate empathy and understanding so that your child can begin to understand and piece together their heightened emotional state. Try saying, “It sounds like you’re frustrated! I totally get it,” or, “You seem so angry right now. Is it because Sandy took your toy? I completely understand why you’d be angry. ”

”

Don’t punish, dismiss, or scold your child for being emotional.

Negative emotions are age appropriate and will eventually subside as kids grow. By disregarding their feelings as insignificant or sending the message that their feelings are bad, you are in effect sending the message that they are bad. This damaging perception can stay with them throughout adulthood.

2. Do help your child label their emotions.

Help your child put words and meaning to how they’re feeling. Once children can appropriately recognize and label their emotions, they’re more apt to regulating themselves without feeling overwhelmed. Try using phrases like, “I can sense you’re getting upset” or, “It sounds like you’re really hurt.”

Don’t convey judgment or frustration.

Sometimes our kids can do or say things that are downright unacceptable and it’s hard to understand the emotions that seem unwarranted or irrational. But try putting yourself in your child’s shoes. Ask questions, seek understanding, and convey to them that you’re on their side, you support them, and you’re there to hold their hand through those moments where things feel overwhelming and tough.

Ask questions, seek understanding, and convey to them that you’re on their side, you support them, and you’re there to hold their hand through those moments where things feel overwhelming and tough.

3. Do set limits and problem-solve.

Help them find ways of responding differently in the future. Enlist their help in seeking alternative solutions to their struggles. Kids yearn for autonomy, and this is a great way to teach them that they are capable of self-regulating themselves in a world that seems unfair and particularly upsetting. Remind them that all emotions are acceptable but all behaviors are not. Here’s a great phrase to set limits and aid in problem solving: “I understand you’re upset, but hitting is not okay. How can you express your feelings without hitting next time?”

Don’t underestimate your child’s ability to learn and grow.

They have an innate capacity to develop into high functioning adults who can problem-solve and respond intelligently to life’s dilemmas. As children, however, they need a listening ear, a hand to hold, and a parent who can challenge them to reach from within and respond accordingly.

As children, however, they need a listening ear, a hand to hold, and a parent who can challenge them to reach from within and respond accordingly.

Being a parent is a challenging and never-ending job. With just three small steps, you can raise children who are bright, self-confident, and better able to navigate the intricacies of life with ease and confidence.

Subscribe below to receive useful tools for raising emotionally intelligent children directly to your inbox.

April Eldemire, LMFT

April Eldemire is a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist, Bringing Baby Home Educator, and couples expert in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. She is passionately devoted to helping couples achieve thriving relationships. For information on a Bringing Baby Home workshop, counseling services, or to subscribe to her Tip Sheet, visit her website.

We'll deliver the blog to you

Get our tips straight to your inbox, and master your relationships. ="wpforms-"]

="wpforms-"]

How to raise emotionally intelligent kids |

Nata Schepy

This post is part of TED’s “How to Be a Better Human” series, each of which contains a piece of helpful advice from people in the TED community; browse through all the posts here.

I’d like you to take a moment and imagine you’re four years old. You’re building a tower, and you’re really proud of it.

But then the next minute another child comes running along and kicks over your tower. You are outraged, and you feel all these feelings bubble up inside — hurt, panic, frustration and helplessness. Just then, an adult comes by.

They get close, get down to your level, and ask: “Honey, what happened?”

In their eyes, there’s compassion and you feel that their body is calm and regulated. And then all those feelings come bubbling out of you — frustration, anger, helplessness.

This adult says: “Tell me all about it. ” They don’t try and fix it, and they don’t say to you: “Don’t worry, you can build another one.” They just let you feel all that you’re feeling. Then they open their arms and you snuggle, take another deep breath, feel better and go back to building your tower.

” They don’t try and fix it, and they don’t say to you: “Don’t worry, you can build another one.” They just let you feel all that you’re feeling. Then they open their arms and you snuggle, take another deep breath, feel better and go back to building your tower.

If you were lucky, the adults in your life gave you lots of space to express how you feel without trying to fix what was going on.

Now I’d like you to try and remember being four years old and a time when you felt angry or sad or scared or you didn’t understand what was going on.

How did the adults in your life respond to you? If you were lucky, they gave you lots of space to express how you feel and listened to your worries and hurt without trying to fix what was going on.

But many of us probably had the opposite experience. Maybe we were told “Stop being so stupid” or “You don’t need to cry.” You might have been sent to your room or to the corner or even been hit for making a mistake.

We still value IQ far more than we value EQ.

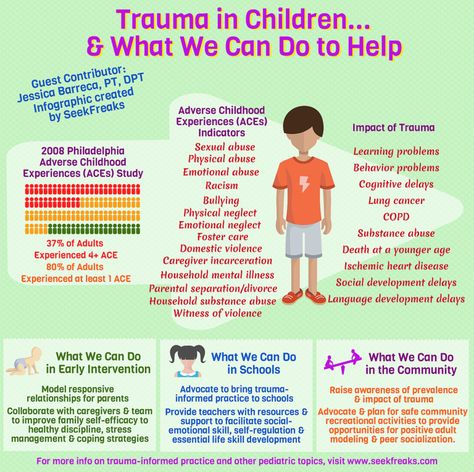

Why am I talking about children and feelings? We’ve seen a steady increase in psychological distress among adults — in Australia and around the world. And I see this increase in distress as being rooted in part in the messages we received as children around how to express feelings and emotions.

Of course, it’s easy to blame our parents for what they did or didn’t do. But the real issue is the lack of emotional literacy in our culture. We don’t teach parents how to respond to children’s feelings and emotions with empathy and compassion. We also don’t teach it in our kindergartens; we don’t teach it in our schools. We still value IQ far more than we value EQ.

My work over the last 16 years with families around attachment, trauma and connection has shown me that there are usually three ways we learn as kids to deal with feelings and emotions.

You might have been labeled as “naughty”, “too much” or “trouble” when all you were doing was responding to your environment.

The first way is repression. Perhaps as a child, you learnt that it wasn’t safe to express your feelings. You might have gotten shut down and told to stop crying. Or you were given a look that made you draw everything inside and push them down deep. The impact of repression on a child is that those feelings stay there.

And then as adults, those feelings can turn up again when life throws us a curveball. Those same feelings come up, but this time, we respond by having another glass of wine or spending hours mindlessly scrolling through Facebook or making ourselves so busy at work that we don’t have time to feel .

The second way is aggression. As a child if we felt really powerless or scared and we grew up in an authoritarian environment where we didn’t have a voice and couldn’t say how we felt, then those feelings would again bubble up inside us. At the point where they would tip over when we felt most frightened or threatened, then they might come out in the form of aggression, rage, loud words. You might have been labeled as “naughty”, “too much” or “trouble” when all you were doing was responding to your environment.

You might have been labeled as “naughty”, “too much” or “trouble” when all you were doing was responding to your environment.

And then as adults, those tendencies show up in bullying behavior. Or they can turn up in harsh critical thoughts about ourselves and others. Or it can show up as violence.

The third way is expression. If we grew up with an imprint that said “Feelings are welcome. I will accept all of you — the happy bits, the sad bits, the joyous bits, the bits that are angry. I’m not going to try and fix them; I’m just going to hold you,” then as adults when things feel hard, we reach for our journal and write down our thoughts. Or we call a friend and say: “Hey, can you listen to me?” Or we might go for a run, do some yoga, speak to our therapist and find a way to lean into the feelings, we feel them and let them go.

When I was a new parent, my game plan was “I’ll just keep them happy all the time.” But that’s a ridiculous thing to do.

I am a mother to three beautiful teenagers. When I first became a parent, like many of you, I had absolutely no clue about what I was doing. When it came to understanding their feelings and emotions, my game plan was “I’ll just keep them happy all the time.” But, as anyone who has kids realizes, that’s a ridiculous thing to do. It is impossible and incredibly exhausting to try to keep people happy all the time. So I learned that I needed to find a way to help my children thrive emotionally and also create harmony for them in our home.

I’m lucky enough to understand and study trauma, and I began to see that what we need as humans is a safe place to unpack all of who we are. We need boundaries and holding, but we also need empathy and compassion for those big feelings that rise within. Instead of trying to fix their problems and trying to make them happy all the time, I just got down low and said: “Tell me all about it.”

And I just listened. Sometimes there were tears; sometimes, rage or complaining. But every time my only job was to sit there and hold space for them.

Sometimes there were tears; sometimes, rage or complaining. But every time my only job was to sit there and hold space for them.

What I began to see was emotional intelligence developing in my children.

How do we expect our children to have empathy and compassion for other people if we don’t show them how?

One evening, I realized just how powerful this was. I was making dinner but I also had to go teach a class so I was doing the hustle that most parents do.

I was just about to go out the door when my youngest daughter, who was five at the time, came into the kitchen. She looked unhappy, and I could see that she’s feeling some feelings. I actually turned to her and said: “Honey, do you think you could hold onto your feelings for a few hours?” Of course, she looked at me like, “Are you kidding?”

At that moment my middle daughter, who was then 10, walked into the room. She said, “I’ll listen to your feelings”, and I’m like “OK. ” So my 10-year-old took the 5-year-old into the bedroom, and I thought, I’m going to be late for work because I need to see what happens here.

” So my 10-year-old took the 5-year-old into the bedroom, and I thought, I’m going to be late for work because I need to see what happens here.

I stood outside their door, and I heard my 10-year-old say: “Tell me all about it.” And the five-year-old started crying and complaining about all the things that had happened at school.

The 10-year-old was going, “Oh that’s hard. What else?” And then there was more complaining and then more tears and giggles and laughter and they came out of the room.

I saw my 10-year-old and said to her, “Honey, how was that for you?” She looked at me and said, “Well, Mama, I just did to her what you do for me.”

At that moment, I realized that children can’t be what they can’t see. How do we expect them to have empathy and compassion for other people if we don’t show them how? How can we expect them to treat others with kindness and respect if they don’t know what that feels like in their own bodies?

I wonder:

- What would it be like if we actually supported parents with the tools and understanding to listen compassionately to their children?

- What would it be like if we actually helped parents unpack their own childhood, so they don’t have to carry that baggage and put it on their children’s shoulders?

- What would it be like if we supported and encouraged boys to cry and be vulnerable and girls to rage and find their voice and speak up for what they need?

- What if instead of harsh disciplines and punishments, we replaced them with compassionate listening and loving limits and boundaries?

- What would it look like if we took all of these ideas and placed them in our education system?

About 18 months ago, a colleague and I created Woodline Primary School. It’s set in the Geelong hinterlands on a beautiful farm with abundant nature. We have horses, chickens and veggie patches, and the philosophy of our school is to foster our students’ emotional well-being in a safe learning environment.

It’s set in the Geelong hinterlands on a beautiful farm with abundant nature. We have horses, chickens and veggie patches, and the philosophy of our school is to foster our students’ emotional well-being in a safe learning environment.

Sir Ken Robinson said the aims of education are to understand the world around us and the world within us. But what if we prioritized the world within?

Research shows that when children feel safe to learn — which means they feel free of judgment and criticism, they’re treated with kindness and respect, they have autonomy over their bodies and their learning, and they are given much love and celebrated for their unique differences — their neurological systems become fully operational and their capacity for growth and learning increases.

Our aim at Woodline is for children to learn about the world and also develop critical life skills such as emotional intelligence, growth mindset, critical thinking and a love of failure. Every time you fail, you realize, “Ah there are so many more options I haven’t yet explored!” More than anything, we want them to learn to be compassionate citizens of the Earth.

Every time you fail, you realize, “Ah there are so many more options I haven’t yet explored!” More than anything, we want them to learn to be compassionate citizens of the Earth.

The late great Sir Ken Robinson said that the aims of education are to understand the world around us and the world within us. But what if we prioritized the world within? Surely, the world around us would make so much more sense.

Just think: How different could the world be if we placed connection, heart and compassionate listening at the center of every one of our relationships?

This post was adapted from a TEDxDocklands Talk. Watch it here:

10 steps to increase your child's emotional intelligence

home

Parents

How to raise a child?

10 Steps to Raising Your Child's Emotional Intelligence

- Tags:

- Expert advice

- 1-3 years

- 3-7 years

- intelligence

Starting from childhood and throughout life, every person has to face a variety of difficulties and painful situations. In difficult times, it is natural to turn to loved ones for support. For a child, the closest people from whom he expects help are his parents. However, supporting another is not an easy task, requiring delicacy, skills in dealing with other people's feelings.

In difficult times, it is natural to turn to loved ones for support. For a child, the closest people from whom he expects help are his parents. However, supporting another is not an easy task, requiring delicacy, skills in dealing with other people's feelings.

In this article, I am a Parent will share with you an instruction-recommendation from psychologists on how to provide support without hurting your child. And he will tell you what to do is absolutely impossible.

1. Recognize the importance of the child's experience

Perhaps the loss of your favorite teddy bear seems like a small inconvenience to you. And for the child, it was his best friend, and the proposal to simply replace him with a new one will cause resentment or indignation.

Try not to respond to the child's problem with the words “it's not scary”, “nothing special happened”, “this is not a reason for tears”.

The child experiences such words as denying the importance of what is happening and devaluing his feelings. Since he cries, it means that in his eyes what happened deserves tears.

Since he cries, it means that in his eyes what happened deserves tears.

2. Let the child cry

When a loved one, especially a child, cries, it is often difficult for us to bear it. And then our first reaction is to do something to dampen the scale of his feelings. However, this makes things easier for the parents themselves.

The psyche of a child copes with losses in the same way as the psyche of an adult - at the first stage, he needs to grieve. Hug him and let him cry. The tears will soon dry up on their own, and the child will gain experience of healthy living of losses and insults, will be able to ask for the support of loved ones in the future and count on you in difficult moments of life.

3. Listen to the child

Do not rush to offer the child options for solving the problem or correcting the situation. First, let him talk, using the technique of active listening: ask clarifying questions. Check if you understand the problem correctly. And most importantly - let the child understand that his feelings are appropriate and have the right to exist. For example, you can say something like this: “I can see that you are very angry/sad/worried, and I can understand you. It's really outrageous/sad/scary when what happened to you happens."

And most importantly - let the child understand that his feelings are appropriate and have the right to exist. For example, you can say something like this: “I can see that you are very angry/sad/worried, and I can understand you. It's really outrageous/sad/scary when what happened to you happens."

4. Avoid the phrase "everything will be fine"

This phrase is often used to support another person. But by saying this, you are making a promise to your child that you cannot keep. You do not know how everything will be, and you cannot know - because you do not control the Universe. Thus, by saying this phrase, you take on a responsibility that you cannot bear, and you risk in the future to seem like a deceiver to the child: after all, you promised that everything would work out. Instead, you can express your intention to do everything in your power to improve the situation.

5. Be aware of your feelings and regulate their strength

Often parents take what happens to their children very close to their hearts. This is quite understandable - how not to worry if your baby, for example, is sick. And how can you not be angry if a teacher mocks your son at school?

This is quite understandable - how not to worry if your baby, for example, is sick. And how can you not be angry if a teacher mocks your son at school?

But your reaction should not overpower the child's reaction. By asking for support, he hopes to get protection from you and lean on you. To give him a foothold, you yourself must remain stable and relatively calm. This is especially true if the child is sick. A sobbing mother at the bedside will only make him feel guilty and exacerbate his already difficult situation.

If you feel that your emotions are running high, look for an opportunity to relieve emotional tension and then communicate with your child.

6. Help the child express his feelings

Situations in which the child turns to you for support, as a rule, are associated with strong emotions for him. It can be grief over a dead pet, anger at offenders, fear or shame.

In order to help your child express feelings, come up with a special ritual. If we are talking about a loss, you can hold a symbolic farewell ceremony: write a message on a piece of paper for a lost toy or pet, tie it to a string of a balloon and send it to the sky. Feelings towards offenders can be expressed through a letter or drawing, and then torn or burned.

If we are talking about a loss, you can hold a symbolic farewell ceremony: write a message on a piece of paper for a lost toy or pet, tie it to a string of a balloon and send it to the sky. Feelings towards offenders can be expressed through a letter or drawing, and then torn or burned.

7. Try not to take things personally

How does a parent feel when their child has problems at school? For example, if there was a conflict with a teacher or a child had a fight with a classmate?

It happens that the most vivid emotions in such a situation are shame and anger at the child for putting the parent in an uncomfortable position. We feel ashamed as if we were the ones who got into a fight, got an A, or the label of "loser" in class. Then our reaction is directed, first of all, to taking care of ourselves, and not about the child. Without understanding the reasons for what happened, we punish him or give advice on how to behave so that we don’t get into such stories again. At this point, childhood experiences may remain behind the scenes.

At this point, childhood experiences may remain behind the scenes.

Remind yourself that it is not you but your child who is in an uncomfortable situation and needs acceptance and support now. Postpone parenting “for later” and return to this issue when the feelings subside.

8. Choose the degree of intervention in the situation

Do not rush to school or to the parents of a neighbor boy in order to protect your child and solve problems for him. It is important for him to learn to respond to the challenges of the world around him, to defend himself and defend his interests.

If his problem is at the level of peers, it does not threaten life and health, and he has not yet tried all possible options - give him a chance to figure it out himself. If it doesn’t work, try to contact a psychologist so that the child can learn new ways of behavior in difficult situations with his help. If he has problems, for example, with a teacher, then the parent’s intervention is appropriate, and maybe even necessary, since in this case the conflict occurs at the “adult-child” level, and the alignment of forces is not equal.

9. Ask how you can help your child

wanted help from me? This advice is especially relevant if you are a parent of a teenager. They often react sharply when parents give advice as a help on how and what to do. By choosing this method of reaction, you risk only causing irritation in response.

10. Look together for ways out of the situation

Sometimes a child's problem can be solved by changing his behavior or relationships with others. For example, if he is teased for being too shy, or he is worried about learning difficulties. In such cases, you can help your child find ways to get out of a traumatic situation. Depending on the age of the child, you can use the composition of a healing fairy tale or story to search for resources. With teens, you can brainstorm, identify options for changing the situation, and come up with a plan of action.

Anna Kolchugina

Your parenting style

By answering the test questions, you will be able to find out what parenting style is typical for you, about its features, advantages and disadvantages, as well as get information about alternative parenting styles and their specifics .

Take the test

The key to raising an emotional child

Irina Balmanji

Over the past decade, scientists have found that success and happiness in all areas of life, including family relationships, is determined by awareness of one's emotions and the ability to cope with one's feelings.

This quality is called "emotional intelligence". From the point of view of education, it means that parents should understand the feelings of their children, be able to sympathize with them, calm them down and gently guide them.

"Emotional educators" teach the child the ability to cope with ups and downs. They allow him to express his negative emotions. They use emotional moments to teach him important life lessons and build a closer relationship with him

In The Emotional Intelligence of the Child, psychologist John Gottman explains what is "normal" and what issues are important at different ages. This information will allow you to better understand the feelings of your children and increase the effectiveness of emotional education.

First months

Child's emotional intelligence

When does a child's emotional relationship with parents begin? Some believe that in the womb, when the child feels her excitement or, conversely, calmness. Others - that immediately after birth, when his parents feed him, rock him to sleep and soothe him. Still others believe that this magical moment occurs a few weeks after birth, when the child for the first time truly smiles at his mother or father.

But most parents would agree that the real fun begins around three months of age, when children develop an interest in social interaction.

No matter how small a three-month-old baby, by observing and imitating, he acquires a huge amount of knowledge how to understand and express emotions. This means that by showing responsiveness and attention, parents can begin an active process of emotional education of their children.

Typically, parents go to great lengths to get and keep their babies' attention in the early stages of emotional communication. For example, parents often use the speech pattern described as "mother language" (although dads can speak it fluently).

For example, parents often use the speech pattern described as "mother language" (although dads can speak it fluently).

It includes raising the voice and slow repetitions accompanied by exaggerated facial expressions. Such a conversation with a child may seem ridiculous and excessive, but parents use it for a reason - it works! When infants are interacted with in this way, they perk up and pay closer attention to the adult.

Source

Most parents also have non-verbal "talks" with their babies. For example, a child sticks out his tongue - and the mother does the same. The baby coos or gurgles - the mother repeats the sound using the same pitch or rhythm.

Imitative talk is very important because it tells the child that the parent is paying close attention to him and responding to his feelings. At such moments, for the first time, the baby feels that the other person understands him, and this lays the foundation for an emotional connection.

As children learn to recognize and imitate their parents' emotional cues, they also develop another important developmental component: the ability to regulate the physiological arousal that results from social contact. Many psychologists believe that children do this by alternating phases of active communication. For some time they pay close attention to others and respond to their game, and then turn away and ignore any adult attempts to entertain them with toys.

Parents are perplexed by this variability, but there is some evidence that children switch off because they need to. For example, he may feel an increase in heart rate, and this physiological state suppresses him. Therefore, the child averts his eyes, turns his head away and does everything possible to avoid further contact. This is how he learns to calm down.

Advice to those who want to raise a child properly: pay attention and respond to the baby's moods.

If your child suddenly stops playing, give him time to rest. If he starts acting up in a situation where there is a lot of talk around and he is often picked up, take him to a separate room where he can calm down.

If he starts acting up in a situation where there is a lot of talk around and he is often picked up, take him to a separate room where he can calm down.

If the child cannot calm down on his own, do everything you can to help him. You have to try and fail until you find the strategy that best suits your child's temperament. Common methods include dimming lights, motion sickness, and gentle conversation.

Those parents who understand that children need to switch from active stimulation to more quiet activities increase the emotional intelligence of their children more effectively.

Parents who help children cope with feelings of discomfort teach them important lessons. Firstly, children learn that their strong negative emotions affect the world around them (parents react to crying), and secondly, that having experienced a strong emotion, you can calm down.

Six to eight months

For babies, this is a period of great exploration, a time when they discover a vast world of objects, people and places. At the same time, they find new ways to express themselves and share feelings such as joy, curiosity, fear, and disappointment with the world around them. This opens up new possibilities for emotional education.

At the same time, they find new ways to express themselves and share feelings such as joy, curiosity, fear, and disappointment with the world around them. This opens up new possibilities for emotional education.

One of the major developmental leaps that usually occurs by six months is the baby's ability to divert attention by keeping in mind an image of an object or person that he is no longer looking at.

In the past, he could only think about the object or person on which his attention was focused. Now he can look at the toy clown with pleasure, and then look at his parents to see if they share his pleasure.

To stimulate the development of emotional intelligence, respond to your child's suggestions to play with objects and imitate his emotional reactions. He will increasingly share his feelings and emotions with you.

Retrieved

By eight months, babies usually begin to crawl and explore their immediate surroundings. They already distinguish between the people they encounter, along with this, the first fears appear. Most likely, it is at this time that you will notice the first cases of "anxiety because of someone else." Just yesterday, the child smiled at strangers at the checkout in the store, and now he hides his face, buried in his mother's shoulder.

Most likely, it is at this time that you will notice the first cases of "anxiety because of someone else." Just yesterday, the child smiled at strangers at the checkout in the store, and now he hides his face, buried in his mother's shoulder.

Between six and eight months, the baby begins to understand the words you speak much better. And although there are still a few months left before he speaks, the baby already understands a lot and fulfills such requests as: "Go get a polar bear and bring it to me."

All of these new abilities—physical mobility and the ability to switch attention, the child’s special attachment to parents, understanding of spoken language, and fear of the unknown—appear together with a skill that psychologists call “response to social cues”: a child, faced with a certain object or phenomenon, turns to parents for emotional information.

For example, approaching an unfamiliar dog, he may hear his mother say: “No, don’t go there!” He already knows how to understand the combination of the mother's words, her tone of voice and facial expression and concludes that his action is potentially dangerous. Or, heading towards a robot that makes loud noises, he can look back at his mother and see that she is smiling. So the child understands that the robot is safe and can be played with.

Or, heading towards a robot that makes loud noises, he can look back at his mother and see that she is smiling. So the child understands that the robot is safe and can be played with.

Parents occupy a unique place in the child's emotional life: they become a "criterion of his safety", so the child explores the world around him more actively. He knows he can trust parental cues such as facial expressions, tone of voice, and body language.

To strengthen the emotional connection with infants of this age, you must become a mirror for your children, that is, return to them the feelings that they express.

It is equally important to help the child learn the names of his feelings. Watch your child closely and don't forget to say things like, "You're sad (fun, scared, etc.) right now, aren't you?" or: “You are very tired. Would you like to sit on my lap for a while?" If you correctly recognized his feelings, he will understand you and show it.

Be prepared that you won't always understand your child, but don't worry, this is normal and fortunately children are very tolerant. Remember that your baby is looking at you and waiting for emotional signals from you.

Remember that your baby is looking at you and waiting for emotional signals from you.

Nine to twelve months

This is the period when children begin to understand that people can share their thoughts and feelings. For example, handing a broken toy to dad and hearing from him: “Oh, the balloon burst. This is very bad. You're sad, aren't you?" the child realizes that his father knows how he feels.

Now he understands that he and his dad can have the same thoughts and feelings and that he can share them with his parents. This undoubtedly strengthens the emerging emotional bond between parents and the child.

At the same time, the child begins to realize that the people and objects in his life have a certain permanence. For example, a baby understands that if a ball rolls under a chair and is not visible, this does not mean that it does not exist; if mom left the room and does not hear me, she remains a part of my world and will return soon.

An emerging understanding of the permanence of objects and people touches on an important aspect of your child's development: his growing attachment to specific people, namely his parents. Now that he is sure that his parents exist, even if they are not around, he can miss them and demand that they stay.

Now that he is sure that his parents exist, even if they are not around, he can miss them and demand that they stay.

The child may start crying and screaming a lot if he sees you, for example, put on a coat and are about to leave. When you leave, he feels that you must be somewhere, but he doesn't know exactly where, and this can upset him. In addition, children at this age still have a poorly developed sense of time, so it is difficult for a child to understand how long you will be gone.

Source

You can help a child of this age cope with the anxiety he feels about leaving you by simply reassuring him that you will return when you are about to leave. Remember: a one-year-old baby, although not yet able to speak, already understands a lot, so your assurances can help him.

Also, don't forget that he is watching your emotions, so if you are anxious or afraid to leave him, he can pick up your feelings and feel the same way.

You can also teach your child to be away from you. To do this, allow him to explore the premises of your house on his own. For example, if he crawls into another (safe from your point of view) room, do not immediately run to see what is happening there, let him be alone.

To do this, allow him to explore the premises of your house on his own. For example, if he crawls into another (safe from your point of view) room, do not immediately run to see what is happening there, let him be alone.

If you are in one room and need to go to another, tell your child where you are going and that you will be back very soon. Gradually, he must understand that his parents can leave, that nothing terrible will happen, and if they say they will return, they can be trusted.

Remember to constantly show your child that you understand his feelings. This way you make him feel safe and strengthen the emotional connection.

Toddlers (1 to 3 years old)

Toddlers are a fun and exciting time when your child develops a sense of self and becomes independent. But this period is also called the two-year crisis: children become much more confident in themselves and begin to contradict you.

At this time, their speech skills are actively developing, but the words you will most often hear are “No!”, “Mine!”, “I myself!” or "I will!" At this time, emotional education becomes an important tool with which parents can help the baby cope with the emerging feelings of disappointment and anger.

As with all stages of development, parents need to look at conflicts and problems from the child's point of view. The main task of the development of the baby at this age is to assert himself as an independent being, so try to avoid situations that will make him feel that he has no power and no control.

At this age, children should be given the opportunity to make a choice several times a day.

Instead of saying, "It's cold outside, you should put on your coat," say, "What would you like to wear today? Jacket or sweater? Set boundaries so that your baby is safe and you are calm.

Simultaneously with self-affirmation, babies become more and more interested in other children. Toddlers older than a year old may be very attracted to each other, but they do not yet have the necessary social skills to play well together. Attempts to play together are often problematic given the "baby ownership rules" which state: 1) if I see it, it's mine; 2) if it's yours and I want it, then it's mine and 3) if it's mine, then it's mine forever.

Parents should understand that this is not greed, but an expression of the baby's developing sense of self. Children of this age can only consider their own point of view and do not understand that others may think differently. So the idea of having to share just doesn't make sense to them.

Source

There is also a positive side to toddler conflicts over toys and the emotional fireworks they usually lead to. Episodes like this offer amazing opportunities for emotional upbringing.

You can help your child recognize and verbalize anger or frustration. (“You go crazy when someone takes your doll,” or “You are frustrated that you can’t get that ball right now.”) You can then work with your child to look for ways to solve the problem (for example, introduce him to the idea of playing queues).

At the same time, it is important to set limits on inappropriate behavior. If the conflict escalates into a fight, the fighter can be told that "we don't hit or hurt our buddies because we're angry" and then sympathize with the victim and reassure her.

Don't forget to praise and reward your baby every time he makes the slightest attempt at an exchange, but especially don't expect him to do it often. At this age, as a rule, parallel games are more successful, where each child has his own space and can play separately from other children.

You can never completely avoid toddler conflicts over toys. But for the sake of peace of mind, you can keep these episodes to a minimum. Explain to your children that they can take toys to a friend or kindergarten only if they share them.

If your baby is waiting for friends at home, take with him some toys that are especially dear to him, which he does not want to give to others. Then, before the guest arrives, solemnly hide them. This will give the child a sense of power and control that he aspires to.

Preschool (from four to seven years old)

By the age of four, children are already "at you" with the world around them. They meet new friends, actively explore the environment and learn a lot of new and interesting things.

With experience comes new challenges: Kindergarten is fun, but caregivers generally expect the child to sit quietly in the group and focus on the task. The child already knows how to behave with friends, but sometimes they still drive him crazy and hurt his feelings. And now, when he is old enough to understand the horrors of fire, war, robbers and death, he tries his best not to be crushed by fear of these events.

To cope with new problems, the child needs to be able to manage his emotions. One of the most important tasks that children face at this age is the need to learn how to suppress inappropriate behavior, focus and motivate themselves to achieve a goal.

Nowhere do children develop the skills to manage their emotions as well as in relationships with peers. It is here that they learn to accurately formulate their thoughts in order to exchange information, and to clarify them if others do not understand them. They learn to speak and play in turn, to share. They learn how to find a common language during the game, to enter into conflicts and resolve them, how to understand the feelings, desires and aspirations of other people.

They learn how to find a common language during the game, to enter into conflicts and resolve them, how to understand the feelings, desires and aspirations of other people.

Friendship is a fertile ground for the emotional development of babies, so give your children more opportunities to connect with friends one on one.

Retrieved

Play activities for children of this age are best done in pairs. This is because children between the ages of four and seven often find it difficult to figure out how to manage relationships with more than one person at the same time.

As a parent, this can be frustrating, especially if you see two children rejecting a third who tries to join the game. But you must understand that rejection does not necessarily mean ill will.

It's just that kids want to protect the game they've created as a couple, and because they can't put their feelings into words that a third child can understand and accept ("I'm sorry, Billy, but a couple is the biggest social unit we can cope at this stage of their development”), they tend to resort to more rude and harsh tactics: “Go away, Billy. We don't play with you!"

We don't play with you!"

Some children may do the same to their parents, saying, “Go away, dad! I do not love you anymore. I love only my mother!” In fact, this means that he enjoys the closeness that he currently has with his mother. Dad shouldn't take this rudeness to heart.

In fact, young children can be very fickle. It is not uncommon for two children to reject a third, and a few minutes later regroup and invite the newly rejected child to join in their new game.

What is the best way to react if you see that your child is excluding a third person from the game? If you want to instill in him kindness and sensitivity to the feelings of other people, then you should tell him how to manage your social relations as politely as possible. Teach your child simple words he can use to explain the situation. For example: “Now I only want to play with someone. But then I can play with you."

If your child is the one currently expelled, it is important that you acknowledge their feelings, especially if they are upset or angry about the situation. Then help him think of ways to solve the problem, such as inviting another child to play or finding something fun to do alone.

Then help him think of ways to solve the problem, such as inviting another child to play or finding something fun to do alone.

In addition to teaching important social skills, friendship between young children gives them the opportunity to fantasize: create characters and act out life situations.

Young friends often use fantasies to help each other work through complicated problems and experiences from everyday life. This contributes to their emotional development, helping to access hidden feelings.

Knowing that fantasy can open the door to the thoughts and worries of a young child, parents of children of this age involved in emotional education can use games.

Children usually project their ideas, wishes, frustrations and fears onto dolls. Parents can encourage the child to explore their feelings and convince him of something, simply by responding to the words of the toy. Here is an example of such a conversation.

Child: This bear is an orphan because his parents no longer need him.

Papa: Are mama and papa bear gone?

Child: Yes, they are gone.

Dad: Will they come back?

Child: Never.

Dad: Why did they leave?

Child: The bear was bad.

Dad: What did he do?

Child: He got angry with the mother bear.

Dad: I think it's okay to get angry sometimes. She will be back.

Child: Yes. She's already on her way.

Dad (takes another bear and speaks in the voice of a mother bear): I went to take out the garbage. I'm already back.

Child: Hello, Mom!

Dad: You were crazy, and that's okay. Sometimes I go crazy too.

Child: I know that.

Source

Another example. Your child wants to be bigger and stronger, so he says: “I used to be small, but now I can lift the crib from one side. Do you know that Superman can even fly?" This means that the child practically asked permission to become Superman in order to explore feelings such as strength and self-confidence. You can contribute and encourage his fantasy by simply saying, “Nice to meet you, Superman. Are you going to fly right now?"

You can contribute and encourage his fantasy by simply saying, “Nice to meet you, Superman. Are you going to fly right now?"

Children can incorporate real-life situations into their play. Don't be surprised if, in the midst of playing with a Barbie doll or imitating superheroes, your child suddenly says: "I'm afraid to stay with this nanny again" or: "How old will I be when I die?"

The origin of children's ideas will most likely remain a mystery to you, but one thing is clear - something in the game scenario stirred up the child's emotions, and he wants to share them. The intimacy and spontaneity of the game allows him to feel safe next to you and raise one or another delicate issue to the surface.

If the child pauses the play in order to explore the emotion, then you should also pause the play and talk to him about the fear involved.

As you talk to your children about their fears, remember to use basic emotional education techniques: help them recognize and label their fear when it comes up, talk about it empathetically and sensitively, and come up with ways to deal with various threats together.

For example, if your child is afraid of fire, say, “House fire is really scary. That's why we have a smoke detector that will alert us if something catches fire."

Primary school age (eight to twelve years old)

At this time, children begin to enter into large social groups and fall under their influence. Now they notice which peers are in and who are not in the group. At this age, children actively develop cognitive abilities and they learn about the power of intellect over emotions.

Your child is becoming more and more influenced by peers, and you may notice that one of the main motivations of his life is the desire to avoid awkwardness at all costs.

Children of this age begin to worry about the style of their clothes, the type of backpack and how their peers feel about what they are doing. The child will go to any lengths not to draw attention to himself, especially if his friends tease him or criticize his actions.

Source

Conformity at this age is quite healthy, although it often irritates parents who want their children to be leaders, not performers. It means that your child is getting better at recognizing social cues and acquiring a skill that will serve him throughout his life. Between eight and twelve, this is especially important because children in this age group can tease and humiliate mercilessly.

It means that your child is getting better at recognizing social cues and acquiring a skill that will serve him throughout his life. Between eight and twelve, this is especially important because children in this age group can tease and humiliate mercilessly.

Children quickly learn that if they are being teased, it is best not to react emotionally at all. Protesting, yelling, complaining to a teacher, or getting angry when a hat is stolen or called names can lead to further humiliation or expulsion from the group. Therefore, in order to maintain dignity, it is better to turn the other cheek.

Understanding the situation, children produce an "ectomy of emotions", removing feelings from the sphere of relationships with peers. Most children master this skill, but those who learn to control their emotions at an early age achieve the greatest success.

A "cold-blooded" attitude towards peer relationships can mislead parents who were good emotional educators.

Mothers and fathers often mistakenly believe that all their children need to do in case of conflict with peers is to share their feelings with another child and come to an agreement. This strategy works well in preschool, but in school, when showing emotion is considered a social nuisance, it can end in disaster.

This strategy works well in preschool, but in school, when showing emotion is considered a social nuisance, it can end in disaster.

Children who have been emotionally trained become perceptive enough to understand this. They are able to recognize the signals of their peers and act accordingly.

Closer to the age of ten, many children become much more capable of logical reasoning. They often react as if they don't have heads, but computers. Tell a nine-year-old child to "pick up your socks" - and he can pick them up, and then put them back, explaining this by saying that he "was not told to put them away."

Insolence and mockery of the adult world are characteristic of children who see life in black and white or divide everything into right and wrong. Think about it: a ten-year-old child suddenly becomes aware of all the arbitrary and illogical standards of life, and life begins to seem crazy to him. He considers adults to be hypocrites.

At this age, your child is concerned about morality and justice, so he can come up with "pure worlds" for himself, where all people are equal, there is no place for war and where there can be no tyranny. The child may begin to despise the adult world with its atrocities. He doubts, he challenges, he starts to think for himself.

The child may begin to despise the adult world with its atrocities. He doubts, he challenges, he starts to think for himself.

The irony is that at the same time the child adheres to the unreasonable and tyrannical standards of his peer group. For example, your daughter may stand up for the human right to freedom of expression and at the same time limit her wardrobe to one style of sweater. She may be deeply concerned about animal cruelty and at the same time take part in a conspiracy to keep a classmate out of a basketball game.

How should parents respond to such inconsistency? Pay no attention and consider this time as a period of research. Know that strict adherence to the often arbitrary rules dictated by peers is part of normal and healthy development. Your child's behavior means that he is able to recognize the standards and values accepted in the peer group, and this allows him to become part of it.

If you find out that your child is involved in bullying another child that you think is unfair, tell him how you feel. Use this precedent to convey to him your values of kindness and honesty. If your child has not shown cruelty, you should not be especially harsh or severely punish him.

Use this precedent to convey to him your values of kindness and honesty. If your child has not shown cruelty, you should not be especially harsh or severely punish him.

If your child is complaining about being excluded from a group or being treated unfairly by peers, you can use emotional coaching techniques to help them deal with feelings of sadness and anger. After overcoming negative emotions, try to look for a solution to the problem together. For example, you can explore the ways in which a person creates and maintains friendships.

Do not try to prove to your child that his desire to dress and act like other children is stupid. Recognize his desire to be accepted by his peers and help him achieve this.

If your child makes fun of the rules of the adult world, don't take that criticism to heart. Brashness, sarcasm, and contempt for adult values are normal behavior at this age.

If your child is really rude to you, tell him about it, but in a special way. (“When you laugh at my hair, I feel that you do not respect me.”) This way you can instill in him such values as kindness and mutual respect in the family. Frondering notwithstanding, children at this age, like everyone else, want to feel emotionally connected to their parents and need their loving guidance.

(“When you laugh at my hair, I feel that you do not respect me.”) This way you can instill in him such values as kindness and mutual respect in the family. Frondering notwithstanding, children at this age, like everyone else, want to feel emotionally connected to their parents and need their loving guidance.

Adolescence

In adolescence, children are concerned with the question of self-identification: who am I? who am I becoming? who am I supposed to be? Therefore, do not be surprised if at some point your child loses interest in family affairs, and relationships with friends come to the fore. In the end, it is through friendship outside the usual boundaries of the house that he finds out who he is.

The path of self-exploration is not always smooth. Hormonal changes can cause uncontrolled and drastic mood changes. At this age, children are very vulnerable and exposed to many dangers. But since this is a natural and inevitable part of human development, the study continues.

One of the major challenges adolescents face in their research is the integration of mind and emotions. If the rational character of Star Trek, Mr. Spock, can serve as a symbol of children of primary school age, then Captain Kirk in the role of commander of the starship Enterprise can be a symbol of adolescents. Kirk is constantly faced with situations where his very sensitive, human side is opposed to logic and experience.

Most often, adolescents face a similar situation in matters of sexuality and self-esteem. A girl is attracted to a boy whom she doesn't really respect. (“He’s so cute. Unfortunately, as soon as he opens his mouth, he ruins everything.”) And the boy catches himself expressing an opinion that he protested against when he heard it from his father. (“I can’t believe it! I talk just like my dad!”)

Suddenly, a teenager realizes that the world is not only black and white, that it consists of many shades of gray.

Adolescence is a difficult period for both a child who is looking for his own way, and for his parents. Now your child is forced to do most of the research without you.

Now your child is forced to do most of the research without you.

Source

Social educator Michael Riera writes: “Until now, you have played the role of a manager in a child’s life: arranging trips and visits to doctors, scheduling extracurricular activities and weekends, helping with and checking homework. He told you about school life, and you were usually the first person he approached with "important" questions. And suddenly, without warning or explanation, you were dismissed from your position. Now, if you want to continue to have a meaningful impact, you have to fight, develop new strategies and put in a lot of effort to get hired again, but already as a consultant.”

How should you play the role of consultant? How can you stay close enough to be an emotional nurturer and still allow your child to develop independently as a fully-fledged adult needs? Here are some tips.

1. Recognize that adolescence is a time when children move away from their parents. Parents need to understand that teenagers need privacy. Eavesdropping on conversations, reading a diary, or too many leading questions sends the message to your child that you don't trust him and creates a barrier to communication.

Parents need to understand that teenagers need privacy. Eavesdropping on conversations, reading a diary, or too many leading questions sends the message to your child that you don't trust him and creates a barrier to communication.

As well as respecting your child's privacy, you must respect the child's right to feel anxious and dissatisfied from time to time. Give your child space to experience deep feelings, let him feel sad, angry, anxious, or discouraged, and don't ask questions like "What's wrong with you?" because they imply that you don't approve of his emotions.

There is another danger: if a teenager suddenly opens his heart to you, try not to show that you instantly understood everything. Your child has encountered a problem for the first time, it seems to him that his experience is unique, and if adults show that they are well aware of the motives of his behavior, the child feels offended. So take the time to listen and hear your teenager. Do not assume that you already know and understand everything he wants to say.

Adolescence is also a time when individuality develops. Your child may choose a style of clothing, hairstyle, music, art and language that you do not like, so always remember that you do not need to approve his choice, you just need to accept it.

2. Be respectful. Imagine for a moment that your best friend began to treat you the way many parents treat their children. How do you feel when you are constantly corrected, reminded of shortcomings, or teased about the most sensitive topics? What should you do if your friend gives you long-winded lectures and explains with condemnation what and how you should do with your life? Most likely, you will decide that this person does not respect you too much and does not care about your feelings.

Of course, you shouldn't treat teenagers as friends (child-parent relationships are much more complicated), but your children certainly deserve as much respect as your buddies. So don't tease, criticize or hurt your children. Communicate your values concisely and without judgment.

Communicate your values concisely and without judgment.

If you have conflicts over your child's behavior, don't label them with common labels (lazy, greedy, careless, selfish). Speak in terms of specific actions. For example, tell him how his actions affected you. (“You hurt me a lot when you leave without washing the dishes because I have to do your job.”)

3. Encourage independent decision making and continue to be your child's emotional educator . Choosing the right degree of participation in a teenager's life is one of the most difficult tasks that parents face.

A teenager should say more often: “The choice is yours”, express confidence in the correctness of his judgments and try not to show hidden resistance under the guise of warning a possible unfavorable outcome of the case.

You should encourage his independence and from time to time allow the teenager to make unwise (but not dangerous) decisions.

Remember that a teenager can learn not only from his successes, but also from his mistakes.