How early can labor be induced

Labor induction - Mayo Clinic

Overview

Labor induction — also known as inducing labor — is prompting the uterus to contract during pregnancy before labor begins on its own for a vaginal birth.

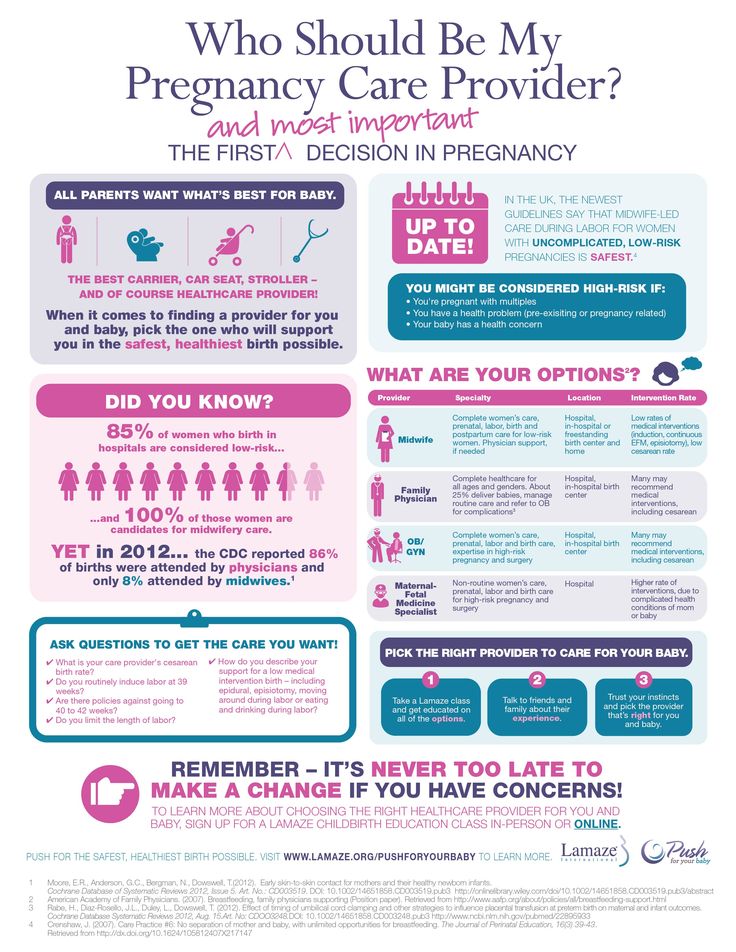

A health care provider might recommend inducing labor for various reasons, primarily when there's concern for the mother's or baby's health. An important factor in predicting whether an induction will succeed is how soft and expanded the cervix is (cervical ripening). The gestational age of the baby as confirmed by early, regular ultrasounds also is important.

If a health care provider recommends labor induction, it's typically because the benefits outweigh the risks. If you're pregnant, understanding why and how labor induction is done can help you prepare.

Products & Services

- Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Why it's done

To determine if labor induction is necessary, a health care provider will likely evaluate several factors. These include the mother's health and the status of the cervix. They also include the baby's health, gestational age, weight, size and position in the uterus. Reasons to induce labor include:

- Nearing 1 to 2 weeks beyond the due date without labor starting (postterm pregnancy).

- When labor doesn't begin after the water breaks (prelabor rupture of membranes).

- An infection in the uterus (chorioamnionitis).

- When the baby's estimated weight is less than the 10th percentile for gestational age (fetal growth restriction).

- When there's not enough amniotic fluid surrounding the baby (oligohydramnios).

- Possibly when diabetes develops during pregnancy (gestational diabetes), or diabetes exists before pregnancy.

- Developing high blood pressure in combination with signs of damage to another organ system (preeclampsia) during pregnancy. Or having high blood pressure before pregnancy, developing it before 20 weeks of pregnancy (chronic high blood pressure) or developing the condition after 20 weeks of pregnancy (gestational hypertension).

- When the placenta peels away from the inner wall of the uterus before delivery — either partially or completely (placental abruption).

- Having certain medical conditions. These include heart, lung or kidney disease and obesity.

Elective labor induction is the starting of labor for convenience when there's no medical need. It can be useful for women who live far from the hospital or birthing center or who have a history of fast deliveries.

A scheduled induction might help avoid delivery without help. In such cases, a health care provider will confirm that the baby's gestational age is at least 39 weeks or older before induction to reduce the risk of health problems for the baby.

As a result of recent studies, women with low-risk pregnancies are being offered labor induction at 39 to 40 weeks. Research shows that inducing labor at this time reduces several risks, including having a stillbirth, having a large baby and developing high blood pressure as the pregnancy goes on. It's important that women and their providers share in decisions to induce labor at 39 to 40 weeks.

It's important that women and their providers share in decisions to induce labor at 39 to 40 weeks.

Request an Appointment at Mayo Clinic

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free, and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips and current health topics, like COVID-19, plus expertise on managing health.

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which

information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with

other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could

include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected

health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health

information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of

privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on

the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on

the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Risks

Uterine incisions used during C-sections

Uterine incisions used during C-sections

A C-section includes an abdominal incision and a uterine incision. After the abdominal incision, the health care provider will make an incision in the uterus. Low transverse incisions are the most common (top left).

Labor induction carries various risks, including:

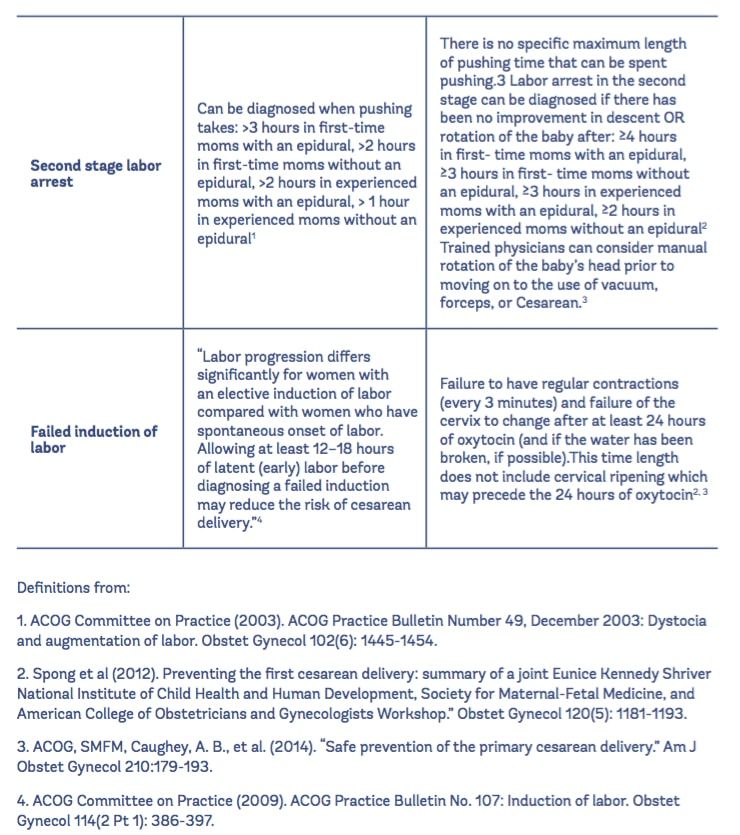

- Failed induction. An induction might be considered failed if the methods used don't result in a vaginal delivery after 24 or more hours. In such cases, a C-section might be necessary.

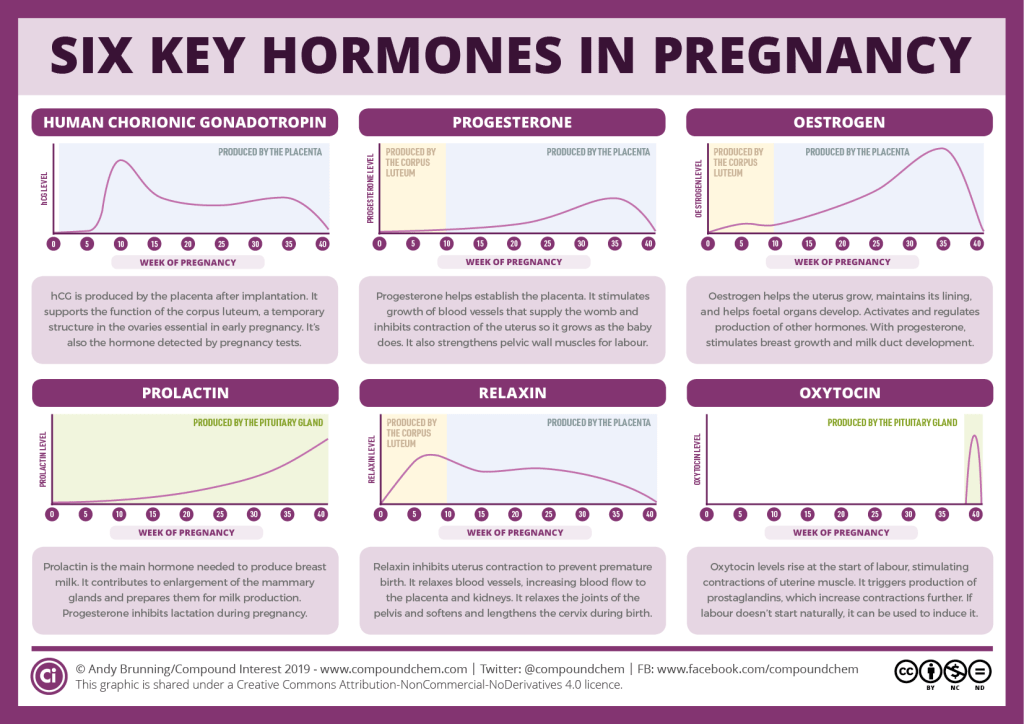

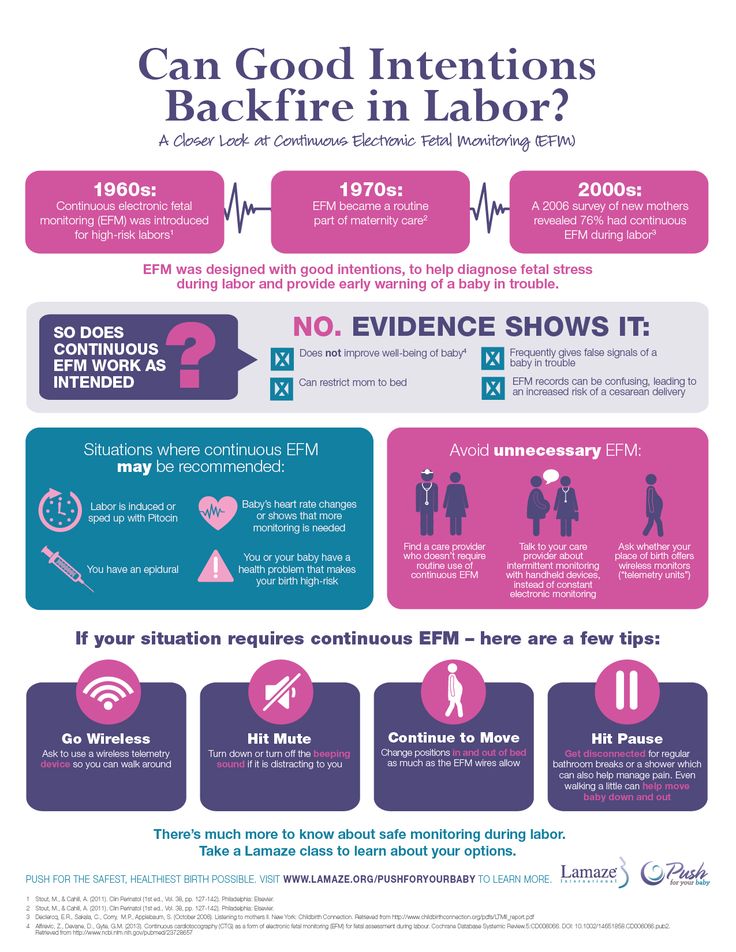

- Low fetal heart rate. The medications used to induce labor — oxytocin or a prostaglandin — might cause the uterus to contract too much, which can lessen the baby's oxygen supply and lower the baby's heart rate.

- Infection. Some methods of labor induction, such as rupturing the membranes, might increase the risk of infection for both mother and baby. The longer the time between membrane rupture and labor, the higher the risk of an infection.

-

Uterine rupture. This is a rare but serious complication in which the uterus tears along the scar line from a prior C-section or major uterine surgery. Rarely, uterine rupture can also occur in women who have not had previous uterine surgery.

An emergency C-section is needed to prevent life-threatening complications. The uterus might need to be removed.

- Bleeding after delivery. Labor induction increases the risk that the uterine muscles won't properly contract after giving birth, which can lead to serious bleeding after delivery.

Labor induction isn't for everyone. It might not be an option if:

- You've had a C-section with a classical incision or major uterine surgery

- The placenta is blocking the cervix (placenta previa)

- Your baby is lying buttocks first (breech) or sideways (transverse lie)

- You have an active genital herpes infection

- The umbilical cord slips into the vagina before delivery (umbilical cord prolapse)

If you have had a C-section and have labor induced, your health care provider is likely to avoid certain medications to reduce the risk of uterine rupture.

How you prepare

Labor induction is typically done in a hospital or birthing center. That's because mother and baby can be monitored there, and labor and delivery services are readily available.

What you can expect

During the procedure

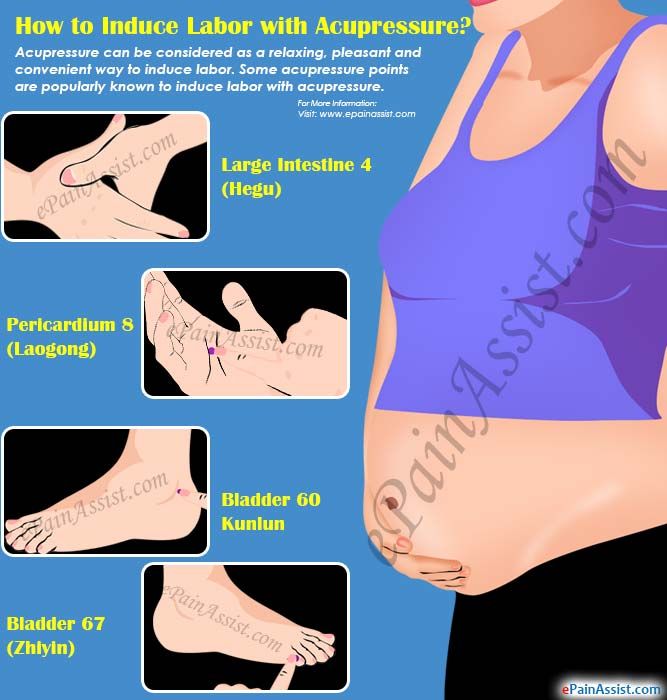

There are various ways of inducing labor. Depending on the circumstances, the health care provider might use one of the following ways or a combination of them. The provider might:

-

Ripen the cervix. Sometimes prostaglandins, versions of chemicals the body naturally produces, are placed inside the vagina or taken by mouth to thin or soften (ripen) the cervix. After prostaglandin use, the contractions and the baby's heart rate are monitored.

In other cases, a small tube (catheter) with an inflatable balloon on the end is inserted into the cervix. Filling the balloon with saline and resting it against the inside of the cervix helps ripen the cervix.

- Sweep the membranes of the amniotic sac.

With this technique, also known as stripping the membranes, the health care provider sweeps a gloved finger over the covering of the amniotic sac near the fetus. This separates the sac from the cervix and the lower uterine wall, which might help start labor.

With this technique, also known as stripping the membranes, the health care provider sweeps a gloved finger over the covering of the amniotic sac near the fetus. This separates the sac from the cervix and the lower uterine wall, which might help start labor. -

Rupture the amniotic sac. With this technique, also known as an amniotomy, the health care provider makes a small opening in the amniotic sac. The hole causes the water to break, which might help labor go forward.

An amniotomy is done only if the cervix is partially dilated and thinned, and the baby's head is deep in the pelvis. The baby's heart rate is monitored before and after the procedure.

- Inject a medication into a vein. In the hospital, a health care provider might inject a version of oxytocin (Pitocin) — a hormone that causes the uterus to contract — into a vein. Oxytocin is more effective at speeding up labor that has already begun than it is as at cervical ripening.

The provider monitors contractions and the baby's heart rate.

The provider monitors contractions and the baby's heart rate.

How long it takes for labor to start depends on how ripe the cervix is when the induction starts, the induction techniques used and how the body responds to them. It can take minutes to hours.

After the procedure

In most cases, labor induction leads to a vaginal birth. A failed induction, one in which the procedure doesn't lead to a vaginal birth, might require another induction or a C-section.

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Related

Products & Services

Medical reasons for inducing labor

Inducing labor (also called labor induction) is when your provider gives you medicine or breaks your water to make labor start.

Your provider may recommend inducing labor if your health or your baby’s health is at risk or if you’re 2 weeks or more past your due date.

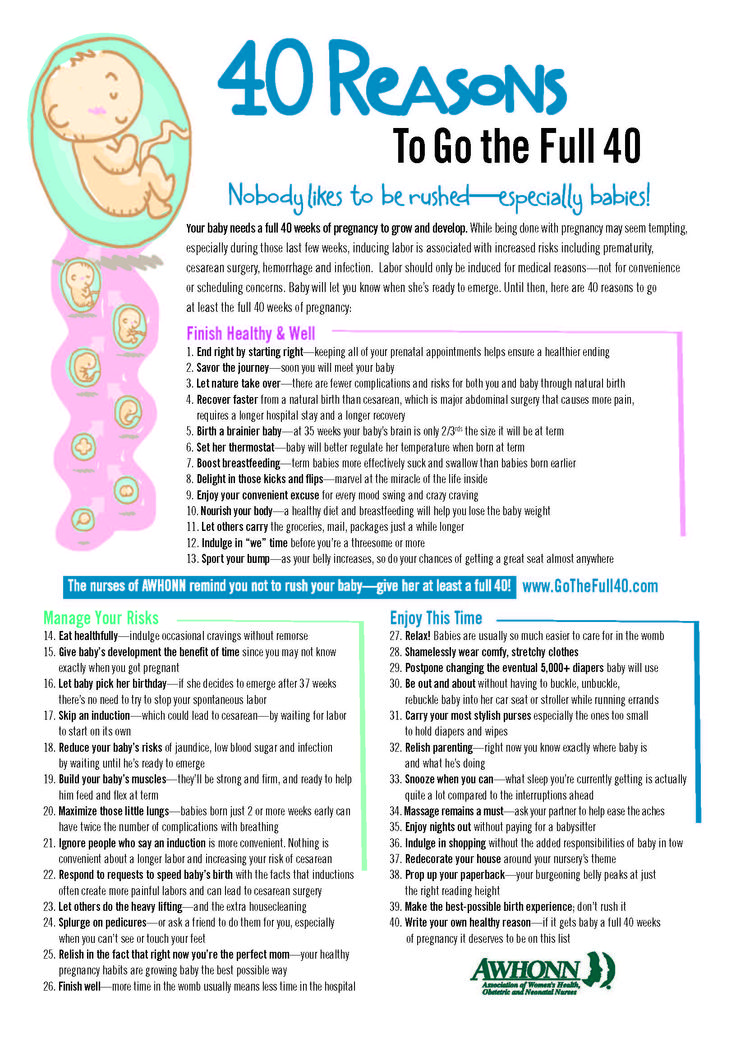

Inducing labor should only be for medical reasons. If your pregnancy is healthy, it’s best to wait for labor to start on its own.

If your provider recommends inducing labor, ask about waiting until at least 39 weeks to be induced so your baby has time to develop in the womb.

What is inducing labor?

Inducing labor (also called labor induction) is when your health care provider gives you medicine or uses other methods, like breaking your water (amniotic sac), to make your labor start. The amniotic sac (also called bag of waters) is the sac inside the uterus (womb) that holds your growing baby. The sac is filled with amniotic fluid. Contractions are when the muscles of your uterus get tight and then relax. Contractions help push your baby out of your uterus.

Your provider may recommend inducing labor if your health or your baby’s health is at risk or if you’re 2 weeks or more past your due date. For some women, inducing labor is the best way to keep mom and baby healthy. Inducing labor should be for medical reasons only.

If there are medical reasons to induce your labor, talk to your provider about waiting until at least 39 weeks of pregnancy. This gives your baby the time she needs to grow and develop before birth. Scheduling labor induction should be for medical reasons only.

This gives your baby the time she needs to grow and develop before birth. Scheduling labor induction should be for medical reasons only.

What are medical reasons for inducing labor?

Your provider may recommend inducing labor if:

- Your pregnancy lasts longer than 41 to 42 weeks. After 42 weeks, the placenta may not work as well as it did earlier in pregnancy. The placenta grows in your uterus (womb) and supplies your baby with food and oxygen through the umbilical cord.

- Your placenta is separating from your uterus (also called placental abruption) or you have an infection in your uterus.

- Your water breaks before labor begins. This is called premature rupture of membranes (also called PROM).

- You have health problems, like diabetes, high blood pressure or preeclampsia or problems with your heart, lungs or kidneys. Diabetes is when your body has too much sugar (called glucose) in your blood. This can damage organs in your body, including blood vessels, nerves, eyes and kidneys.

High blood pressure is when the force of blood against the walls of the blood vessels is too high and stresses your heart. Preeclampsia is a serious blood pressure condition that can happen after the 20th week of pregnancy or after giving birth (called postpartum preeclampsia).

High blood pressure is when the force of blood against the walls of the blood vessels is too high and stresses your heart. Preeclampsia is a serious blood pressure condition that can happen after the 20th week of pregnancy or after giving birth (called postpartum preeclampsia). - Your baby has a stopped growing. Or your baby has oligohydramnios. This means your baby doesn’t have enough amniotic fluid.

- You have Rh disease and it causes problems with your baby’s blood.

What are the risks of scheduling labor induction for non-medical reasons?

Scheduling labor induction may cause problems for you and your baby because your due date may not be exactly right. Sometimes it’s hard to know exactly when you got pregnant. If you schedule labor induction and your due date is off by a week or 2, your baby may be born too early. Babies born early (called premature babies) may have more health problems at birth and later in life than babies born on time. This is why it’s important to wait until at least 39 weeks to induce labor.

This is why it’s important to wait until at least 39 weeks to induce labor.

If your pregnancy is healthy, it’s best to let labor begin on its own. If your provider talks to you about inducing labor, ask if you can wait until at least 39 weeks to be induced. This gives your baby’s lungs and brain all the time they need to fully grow and develop before he’s born.

If there are problems with your pregnancy or your baby’s health, you may need to have your baby earlier than 39 weeks. In these cases, your provider may recommend an early birth because the benefits outweigh the risks. Inducing labor before 39 weeks of pregnancy is recommended only if there are health problems that affect you and your baby.

If your provider recommends inducing labor, ask these questions:

- Why do we need to induce my labor?

- Is there a problem with my health or the health of my baby that may make inducing labor necessary before 39 weeks? Can I wait to have my baby closer to 39 weeks?

- How will you induce my labor?

- What can I expect when you induce labor?

- Will inducing labor increase the chance that I'll need to have a c-section?

- What are my options for pain medicine?

Last reviewed: September, 2018

See also: 39 weeks infographic

Induction of labor or induction of labor

The purpose of this information material is to familiarize the patient with the induction of labor procedure and to provide information on how and why it is performed.

In most cases, labor begins between the 37th and 42nd weeks of pregnancy. Such births are called spontaneous. If medications or medical devices are used before the onset of spontaneous labor, then the terms "stimulated" or "induced" labor are used in this case.

Labor should be induced when further pregnancy is for some reason unsafe for the mother or baby and it is not possible to wait for spontaneous labor to begin.

The purpose of stimulation is to start labor by stimulating uterine contractions.

When inducing labor, the patient must be in the hospital so that both mother and baby can be closely monitored.

Labor induction methods

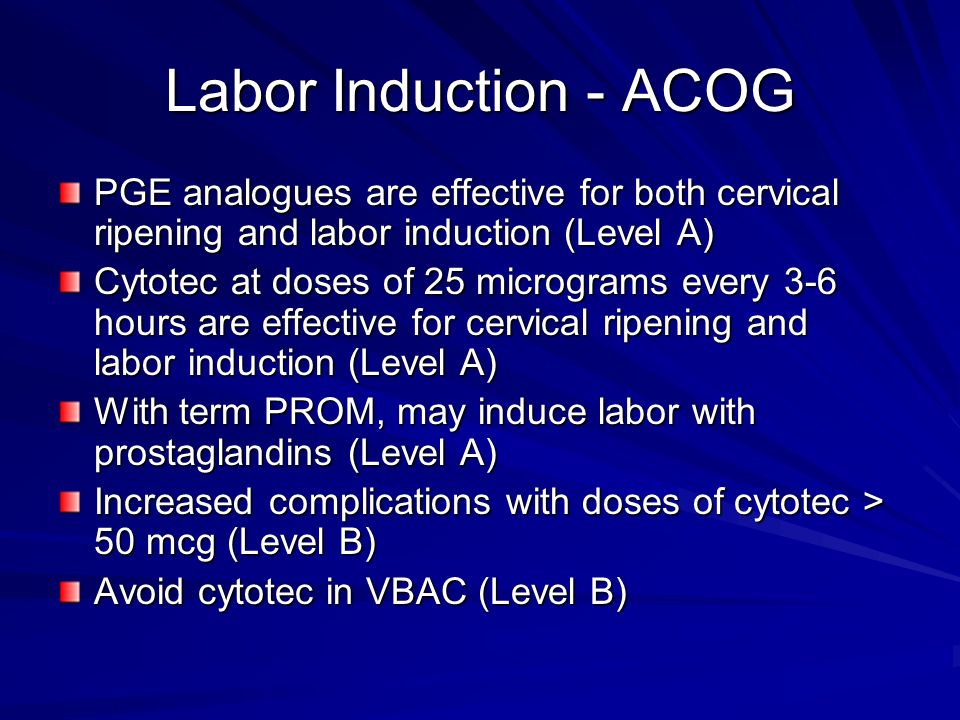

The choice of labor induction method depends on the maturity of the cervix of the patient, which is assessed using the Bishop scale (when viewed through the vagina, the position of the cervix, the degree of its dilatation, consistency, length, and the position of the presenting part of the fetus in the pelvic area are assessed). Also important is the medical history (medical history) of the patient, for example, a past caesarean section or operations on the uterus.

Also important is the medical history (medical history) of the patient, for example, a past caesarean section or operations on the uterus.

The following methods are used to induce (stimulate) labor:

- Oral misoprostol is a drug that is a synthetic analogue of prostaglandins found in the body. It prepares the body for childbirth, under its action the cervix becomes softer and begins to open.

- Balloon Catheter - A small tube is placed in the cervix and the balloon attached to the end is filled with fluid to apply mechanical pressure to the cervix. When using this method, the cervix becomes softer and begins to open. The balloon catheter is kept inside until it spontaneously exits or until the next gynecological examination.

- Amniotomy or opening of the fetal bladder - in this case, during a gynecological examination, when the cervix has already dilated sufficiently, the fetal bladder is artificially opened. When the amniotic fluid breaks, spontaneous uterine contractions will begin, or intravenous medication may be used to stimulate them.

- Intravenously injected synthetic oxytocin - acts similarly to the hormone of the same name produced in the body. The drug is given by intravenous infusion when the cervix has already dilated (to support uterine contractions). The dose of the drug can be increased as needed to achieve regular uterine contractions.

When is it necessary to induce labor?

Labor induction is recommended when the benefits outweigh the risks.

Induction of labor may be indicated in the following cases:

- The patient has a comorbid condition complicating pregnancy (eg, high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, preeclampsia, or some other condition).

- The duration of pregnancy is already exceeding the norm - the probability of intrauterine death of the fetus increases after the 42nd week of pregnancy.

- Fetal problems, eg, problems with fetal development, abnormal amount of amniotic fluid, changes in fetal condition, various fetal disorders.

- If the amniotic fluid has broken and uterine contractions have not started within the next 24 hours, there is an increased risk of inflammation in both the mother and the fetus. This indication does not apply in case of preterm labor, when preparation of the baby's lungs with a special medicine is necessary before delivery.

- Intrauterine fetal death.

What are the risks associated with labor induction?

Labor induction is not usually associated with significant complications.

Occasionally, after receiving misoprostol, a patient may develop fever, chills, vomiting, diarrhea, and too frequent uterine contractions (tachysystole). In case of too frequent contractions to relax the uterus, the patient is injected intravenously relaxing muscles uterus medicine. It is not safe to use misoprostol if you have had a previous caesarean section as there is a risk of rupture of the uterine scar.

The use of a balloon catheter increases the risk of inflammation inside the uterus.

When using oxytocin, the patient may rarely experience a decrease in blood pressure, tachycardia (rapid heartbeat), hyponatremia (lack of sodium in the blood), which may result in headache, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, depression strength and sleepiness.

Induction of labor compared with spontaneous labor increases the risk of prolonged labor, the need for instrumental intervention

(use of vacuum or forceps), postpartum hemorrhage, uterine rupture, the onset of too frequent uterine contractions and the associated deterioration of the fetus, prolapse umbilical cord, as well as premature detachment of the placenta.

If induction of labor is not successful

The time frame for induction of labor may vary from patient to patient, on average labor begins within 24-72 hours. Sometimes more than one method is required.

The methods used do not always work equally quickly and in the same way on different patients. If the cervix does not dilate as a result of induction of labor, your doctor will tell you about your next options (which may include inducing labor later, using a different method, or delivering by caesarean section).

If the cervix does not dilate as a result of induction of labor, your doctor will tell you about your next options (which may include inducing labor later, using a different method, or delivering by caesarean section).

ITK833

This informational material was approved by the Women's Clinic on 01/01/2022.

Induction of labor in women with a normal pregnancy of 37 weeks or more

Does an induction policy at 37 weeks' gestation or more reduce the risks for infants and their mothers compared with a policy of waiting until later gestational age or until there is an indication for induction of labor?

This review was originally published in 2006 and subsequently updated in 2012 and 2018.

What is the problem?

The average pregnancy lasts 40 weeks from the start of a woman's last menstrual period. Pregnancies lasting more than 42 weeks are described as "post-term" and therefore the woman and her doctor may decide to give birth by induction. Factors associated with postnatal pregnancy and delayed delivery include obesity, first birth, and maternal age over 30 years.

Factors associated with postnatal pregnancy and delayed delivery include obesity, first birth, and maternal age over 30 years.

Why is this important?

Protracted (term) pregnancy may increase risks for infants, including greater risk of death (before or shortly after birth). However, induction (stimulation or induction) of labor can also pose risks to mothers and their babies, especially if the woman's cervix is not ready for delivery. Current diagnostic methods cannot predict risks to babies or their mothers per se, and many hospitals have specific policies regarding how long a pregnancy can last.

What evidence did we find?

We searched for evidence (July 17, 2019) and identified 34 randomized controlled trials in 16 different countries involving more than 21,500 women (mostly at low risk of complications). The trials compared a policy of induction of labor after 41 completed weeks of gestation (>287 days) with a policy of waiting (expectant management).

Labor induction policies were associated with fewer perinatal deaths (22 trials, 18 795 babies). Four perinatal deaths occurred in the induction policy group compared with 25 perinatal deaths in the expectant management group. Fewer stillbirths occurred in the induction group (22 trials, 18,795 infants): two in the induction group and 16 in the expectant management group.

Women in the induction of labor groups in the included studies were probably less likely to deliver by caesarean section than in the expectant management groups (31 studies, 21,030 women), and there was probably little or no difference when compared with assisted vaginal delivery (22 studies, 18,584 women).

Fewer infants were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in the induction policy group (17 trials, 17,826 infants; high-certainty evidence). A simple test of the baby's health status (Apgar score) at five minutes after birth was likely to be more favorable in the induction groups than expectant management (20 trials, 18,345 infants).

An induction policy may make little or no difference for women who have had a perineal injury, and likely has little or no effect on the number of women with postpartum hemorrhage or breastfeeding at hospital discharge. We are uncertain about the effect of induction or expectant management on length of stay in the maternity hospital due to the very low certainty of the evidence.

Among newborns, the number of children with trauma or encephalopathy was similar in both groups (moderate and low-certainty evidence, respectively). None of the studies reported the development of neurodevelopmental problems during follow-up of children and postpartum depression in women. Only three trials reported some measure of maternal satisfaction.

What does this mean?

An induction policy compared to expectant management is associated with fewer infant deaths and probably fewer caesarean sections; and probably has little or no effect on assisted vaginal delivery.