How does poverty affect the development of a child

Poverty and its Effects on Children

Blog

01/28/2019

Children in Poverty – Effects of Poverty on Children

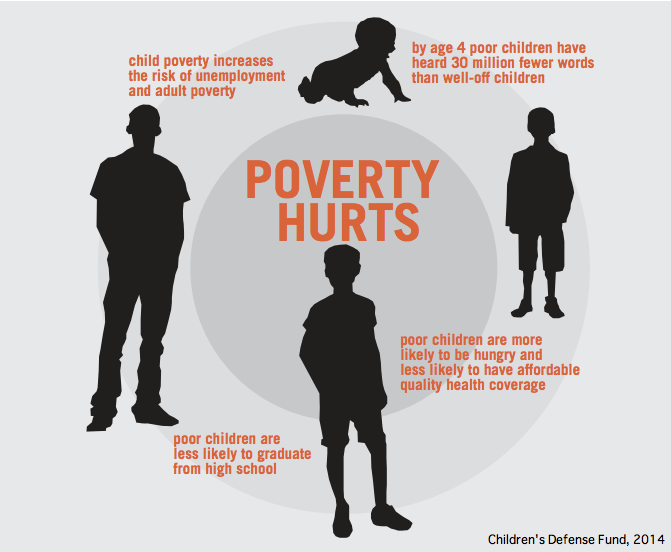

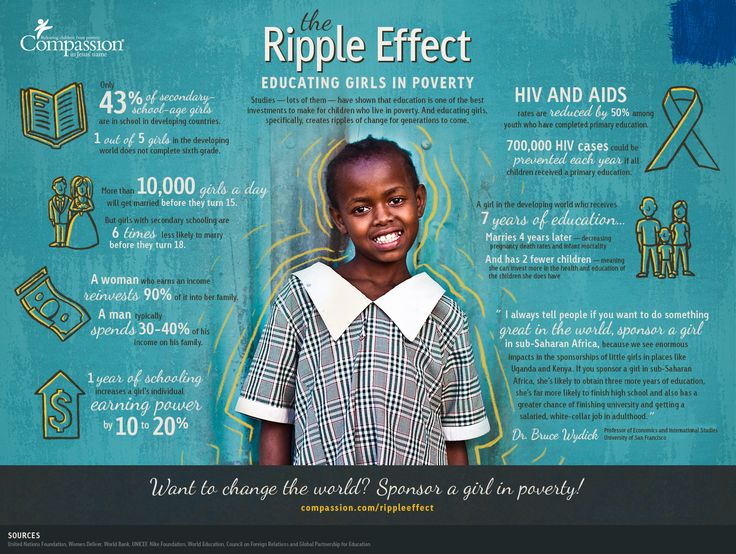

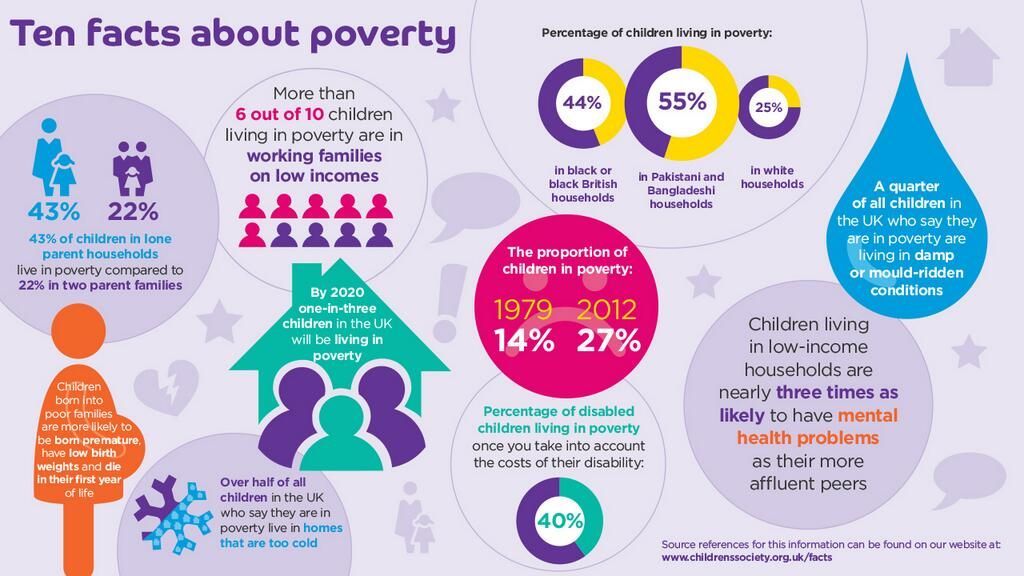

It’s no question that poverty and its effects harms communities and even entire countries, but did you know that socioeconomic status directly impacts children as well? Children living in poverty experience a wide variety of risk factors, ranging from health concerns to increased difficulties at school. Unfortunately, about 15 million children (approximately 21% of all children!) in the United States live in low-income families (incomes below the federal poverty line or poverty threshold), a measurement that has been shown to underestimate the needs of working families. Research shows that on average, families require a household income of about twice that amount to cover basic expenses. It is no secret that poverty in America is an epidemic that needs to be confronted head-on! Besides having difficulties meeting basic, everyday needs, here are just a few of the many other ways child poverty harms children of all ages:

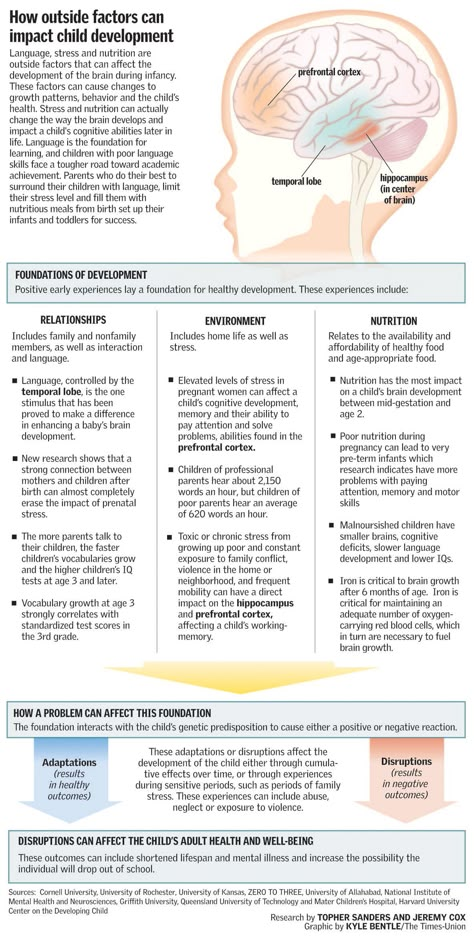

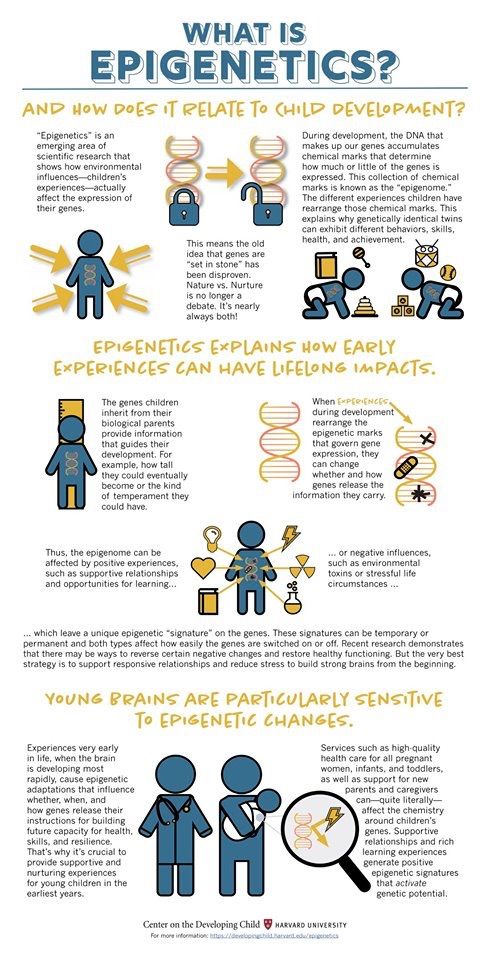

The Health Risks of Childhood PovertyMost are unaware of just how greatly low-income households & extreme poverty can influence child health and cognitive child development. However, poverty does indeed impact growth from early childhood, starting with brain development and other body systems. Poverty itself can negatively affect how the body and mind develop, and economic hardship can actually alter the fundamental structure of the child’s brain. Children who directly or indirectly experience risk factors associated with poverty have higher odds of experiencing poor health problems as adults such as heart disease, hypertension, stroke, obesity, certain cancers, and even a shorter life expectancy.

In addition to brain development and health risks associated with holding low-socioeconomic status, a child’s mental health is at risk of being greatly affected as well. Low-income parents and children are more likely to be affected by challenges with mental health and mental illness. These mental health problems often impair overall academic achievement and the ability of children to succeed in school. The effects of poverty can place these children at a higher risk of involvement with child welfare and juvenile justice agencies.

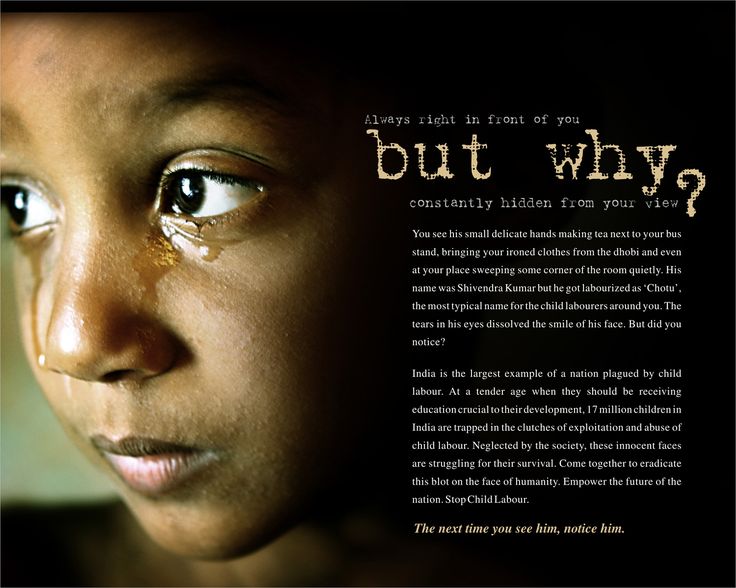

Unfortunately, children who are poor are more likely to be raised in impoverished neighborhoods. These types of neighborhoods that have concentrated poverty levels are often associated with difficulties in academics, behavioral and social issues, and worsening health. Additionally, these children are more likely to live in neighborhoods where they are exposed to environmental risk factors. These socioeconomic risk factors may include malnutrition, pollution, food insecurity, housing instability, economic hardship, led exposure, violence, and crime.

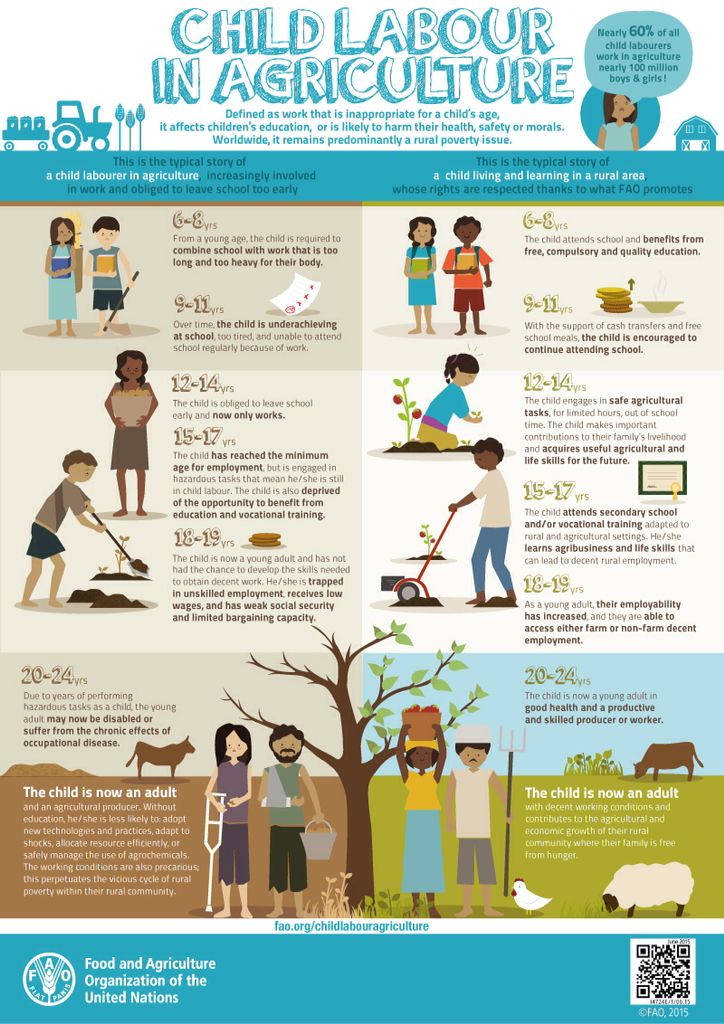

In regards to violence, even indirect exposure (such as witnessing a violent act or simply knowing of its occurrence) has shown to leave adverse developmental outcomes. As a result of family income inequality, poor children are also disproportionately more likely to attend schools in districts with fewer resources, less funding from local tax dollars, less parental involvement due to longer, lower wage working hours, facilities that are inadequate, and with school leadership that has a much higher turnover.

In addition to these macro-level factors that influence neighborhood schools, poverty affects the way children learn as well. For starters, children who directly or indirectly experience risk factors associated with poverty or low parental education have higher than a 90% chance of having 1 or more problems with speech, learning, and/or emotional development. Also, kids who are experiencing poverty at home often have difficulties focusing at school. (You cannot learn well on an empty stomach!) There are also often higher levels of stressors and issues that these young children are worried about after school, in addition to having to worry about completing their homework.

The Impact of Children in Poverty Within The FamilyBecause children grow within the context of a family unit, it is important to recognize how poverty affects the household as a whole. Firstly, parents living below the poverty level often have difficulties meeting basic economic needs for their families, such as paying for rent, food, utilities, clothing, education, accommodations, health care, health insurance, transportation, and child care. Living in poverty often means having limited access to health care, food and housing security, greater risk of school drop-out for children, homeless, unemployment due to lack of education or child care and, unfortunately, not reaching one’s full potential.

Living in poverty often means having limited access to health care, food and housing security, greater risk of school drop-out for children, homeless, unemployment due to lack of education or child care and, unfortunately, not reaching one’s full potential.

Poverty Status and Stress

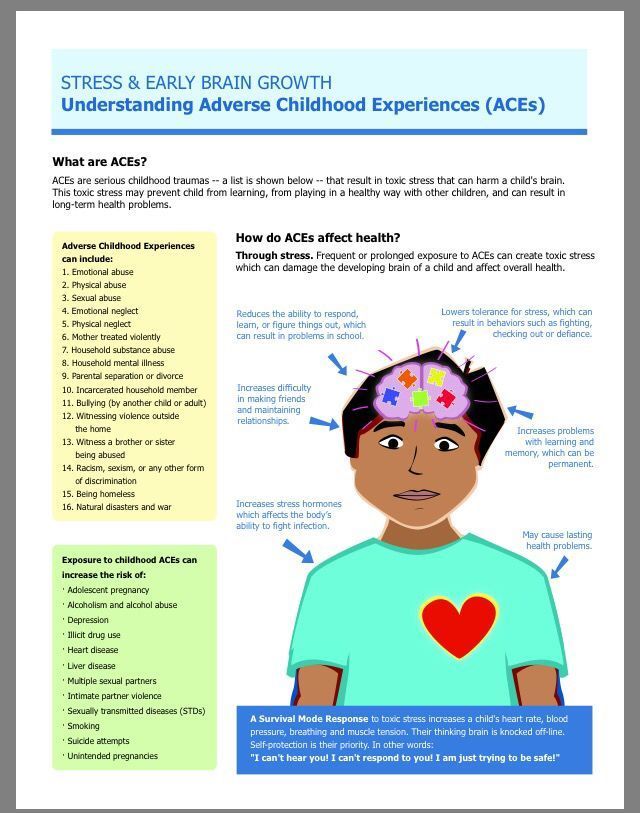

Additionally, stress and alienation have negative impacts connected to having little or no income. For parents, financial uncertainty is their major stressor when trying to meet their family’s basic needs. According to the “Stress in America” survey conducted by the American Psychological Association (2017), the proportion of adults who reported that stress impacts their physical and mental health and overall well-being is significantly growing.

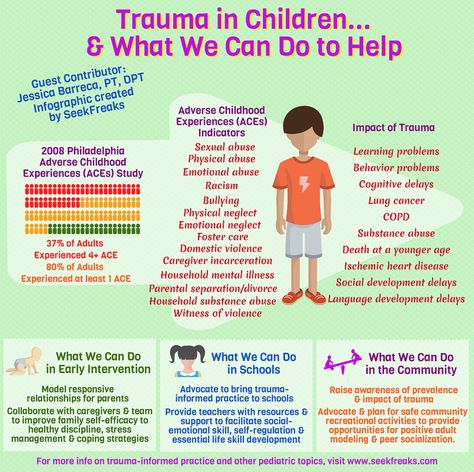

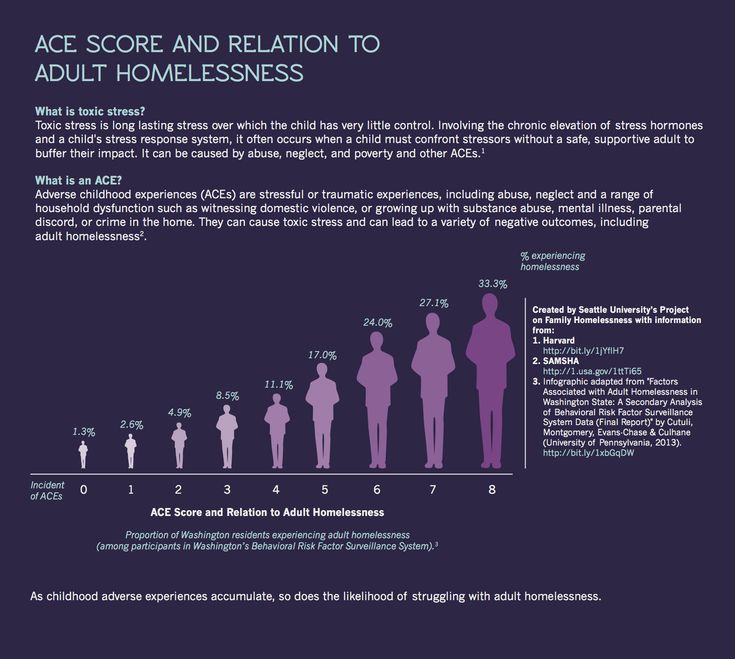

Unfortunately, poverty status and stress are two markedly consistent factors among perpetrators of child abuse, and they are intrinsically intertwined. While there are multiple causes of child maltreatment (such as mental illness, intimate partner violence, substance abuse, poor parenting skills, unmanaged anger, lack of coping strategies, or other individual issues), the correlation between poverty and stress, abuse, and neglect cannot be ignored. Children that experience these traumatic events (also known as adverse childhood experiences) are more likely to develop a variety of health problems, behavioral issues, or even substance abuse disorders down the road. The negative effects of adverse childhood experiences will only lead to further problems as the child develops from teen to adulthood.

Children that experience these traumatic events (also known as adverse childhood experiences) are more likely to develop a variety of health problems, behavioral issues, or even substance abuse disorders down the road. The negative effects of adverse childhood experiences will only lead to further problems as the child develops from teen to adulthood.

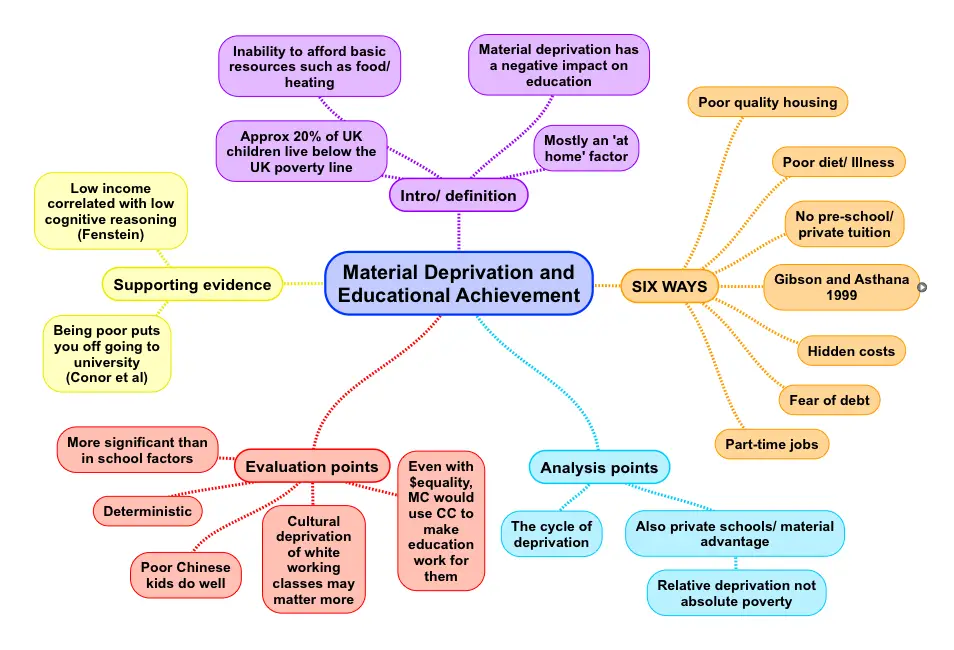

Multiple studies have found environmental complexities and material deprivations to be causes of serious physical abuse. For example, low income, uneducated caregivers, single parent households, an incarcerated parent, teen pregnancy, unemployment, and living in the midst of community violence are macro-level socioeconomic factors that undoubtedly lead to stress in the family.

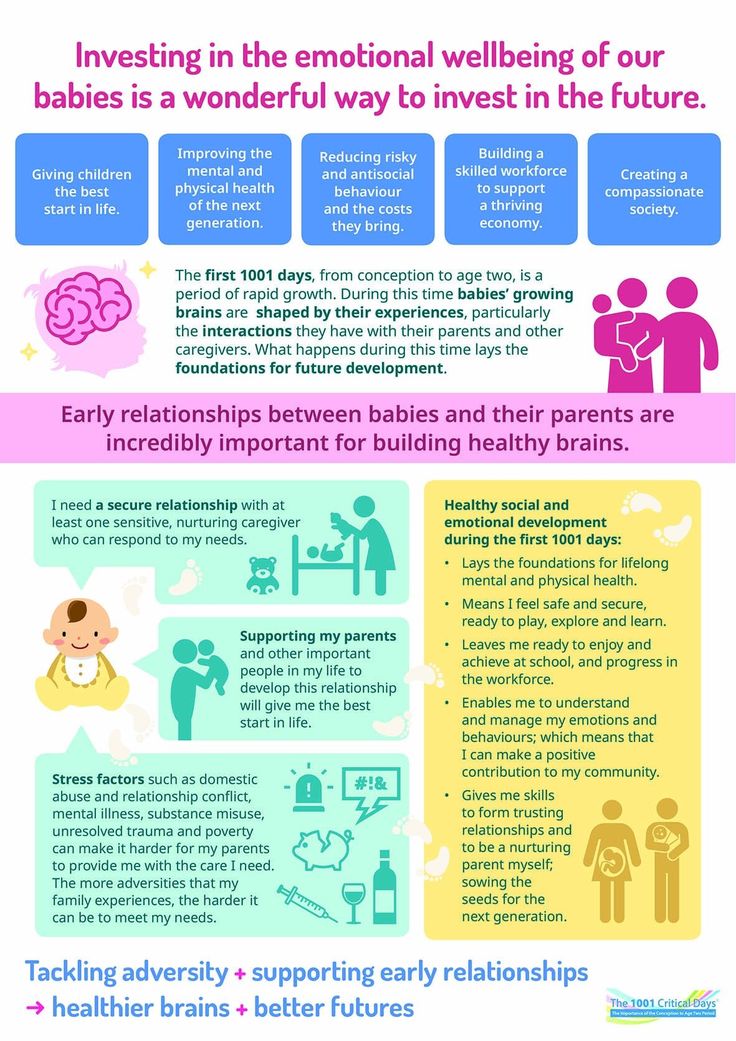

Additionally, inadequate bonding between the child and their caregivers, intimate partner violence in the home, a physical or mental disability (either the parent or the child), and other health problems (such as being born prematurely), are micro-level issues that place parents under tremendous mental stress, which may translate into abusive behavior. Younger children are more vulnerable to abuse as well, as 46.5% of child abuse fatality victims were younger than one year old, and 34.5% were between the ages of one and three (“Child Welfare Information Gateway,” n.d.).

Younger children are more vulnerable to abuse as well, as 46.5% of child abuse fatality victims were younger than one year old, and 34.5% were between the ages of one and three (“Child Welfare Information Gateway,” n.d.).

Furthermore, poor families living in poverty may not have access to adequate resources. Family income inequality creates high risk for neglect, criminal activity, and physical abuse due to additional stress in the home. While it is significant to note that most parents living in poverty or under stressful circumstances will not abuse or neglect their children, kids who grow up in poverty are at a greater risk for maltreatment overall.

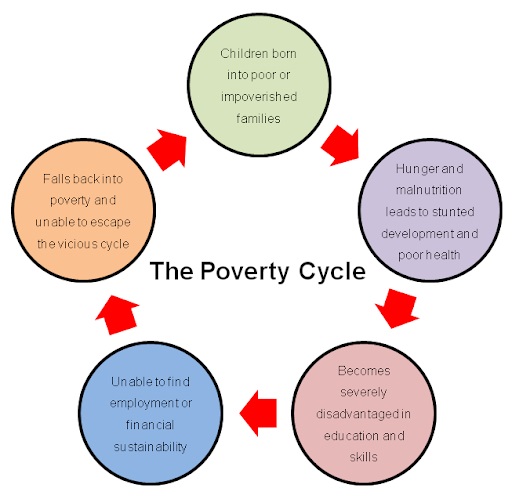

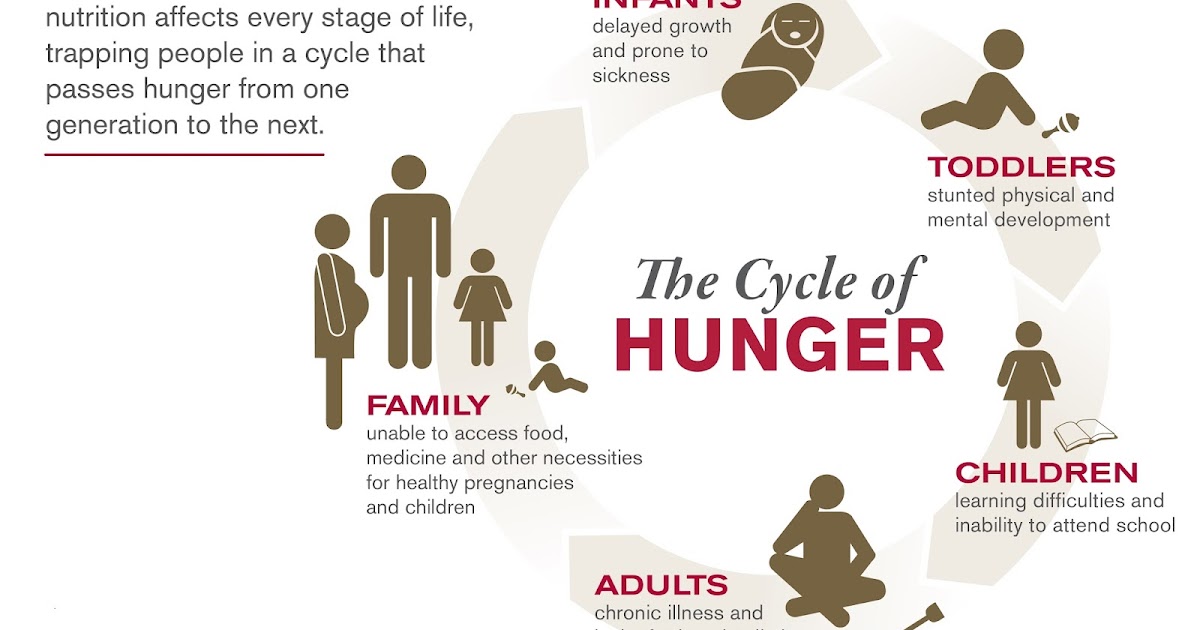

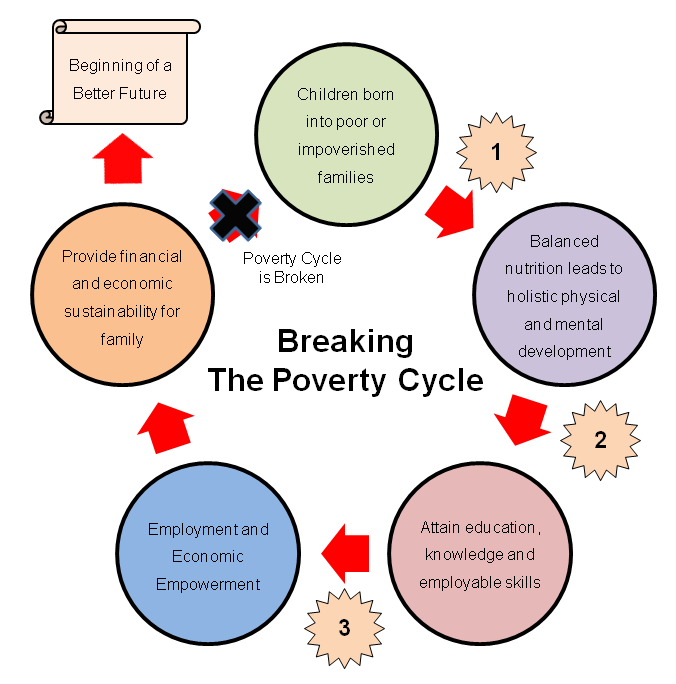

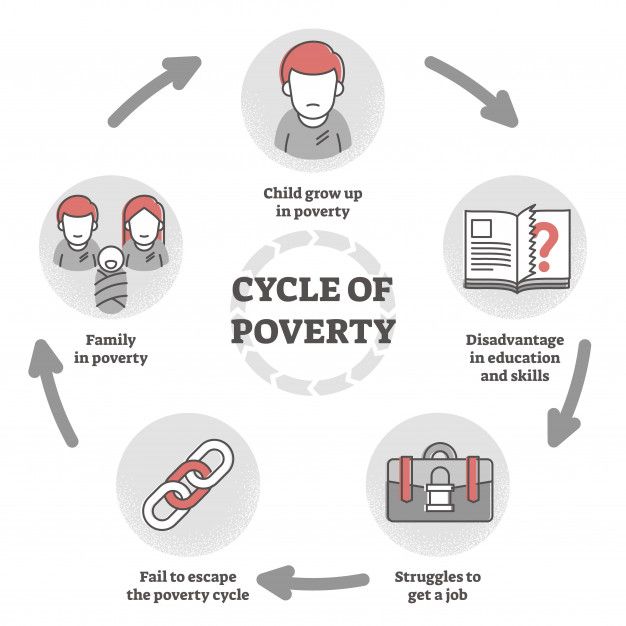

The Cycle of Poverty

You may have heard the term, “The Cycle of Poverty.” The cycle of intergenerational poverty refers to the idea that poor parents raise their children in poverty, who are then more likely to become poor parents themselves. It is important to keep in mind that children are more vulnerable to negative consequences of poverty, than adults. While various types of risk factors exist for impoverished households (such as including single parent or single income households and low parental education), the best protection against further increasing the child poverty rate is access to the labor market, quality childcare, and adequate employment and education for parents.

While various types of risk factors exist for impoverished households (such as including single parent or single income households and low parental education), the best protection against further increasing the child poverty rate is access to the labor market, quality childcare, and adequate employment and education for parents.

In fact, according to Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child, it is best and more useful to intervene right at the start of development, rather than to try to fix things later. In other words, if we provide the right tools for parents and poor families in need, their children will have greater chances to get out of poverty and become successful as adults. Children who live in poverty are affected by one or more risk factors that have been linked to academic failure and poor health, a perfect combination for remaining in the cycle of poverty. According to the National Center for Children in Poverty (2017), between three and 16 percent of children are affected by poverty in combination with another risk factor. An example of a risk factor may include single parent households or parents with no or low education (1.7 million). These alarming numbers will continue to rise if no adequate intervention is used.

An example of a risk factor may include single parent households or parents with no or low education (1.7 million). These alarming numbers will continue to rise if no adequate intervention is used.

Today, the leading strategy to break the cycle of poverty in families is the two-generation approach, which aims to improve the family’s economic growth and circumstances by supporting parents both as workers and as parents. If low-income parents are provided with the opportunity to receive higher education, then they will be given the chance they need to compete for higher pay.

Furthermore, if low-income parents are provided with quality child care and access to resources like children’s therapy, then their children’s development will improve. Additionally, while we mentioned the numerous health outcomes that can arise from growing up in poverty, studies have shown that ending intergenerational poverty can greatly reduce these odds. Overall, by helping both generations reach their highest potential, we are helping multiple generations reach economic growth in order to escape the cycle of intergenerational poverty.

Overall, by helping both generations reach their highest potential, we are helping multiple generations reach economic growth in order to escape the cycle of intergenerational poverty.

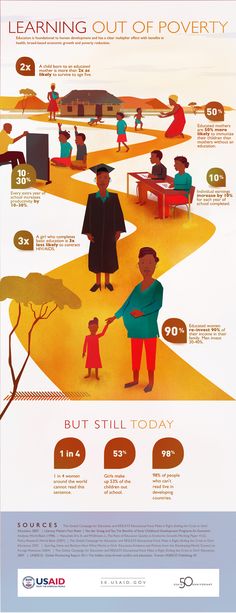

Parental Education as Protective Factor

Children who attend child care at an early age and whose parents have a high educational attainment, experience positive developmental benefits at a higher rate, compared to children who do not, including:

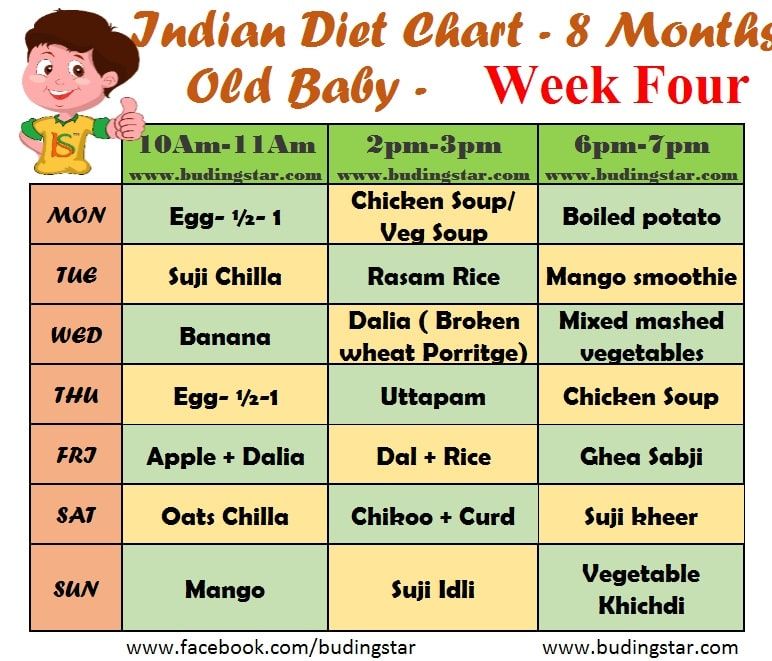

- By age 18 months, there is a significant difference in vocabulary between children whose parents have a high educational attainment and attend a high-quality child care, compared to children whose parents have a low educational attainment and low income. By age 3, children whose parents have a college degree have a vocabulary 2-3 times larger than children whose parents did not earn a high school diploma.

- By age 3, children with employed parents have a vocabulary of about 575 words compared to children with unemployed parents, who have a vocabulary of about 300 words.

- Children with educated parents have someone in their own home who understands the struggles associated with academics and can help them push through the everyday obstacles.

- Overall, parental education is indeed a significant predictor of child achievement. For example, in an analysis of data from several large-scale developmental studies, researchers concluded that maternal education was linked significantly to children’s intellectual outcomes even in the face of poverty. Additionally, an examination of the direct effects of parental education, but not income, on children’s standardized achievement scores found that both parental education and household income exerted indirect effects on parents’ achievement-fostering behaviors, and subsequently children’s achievement, through their effects on parents’ educational expectations.

By helping parents gain the resources and support needed to pursue an education, we can not only help them and their children, but their entire family and community for generations to come.

School as a Protective Factor

Likewise, it is no mystery that children’s own education is a tremendous protective factor in poverty as well. However, you may be surprised to learn that even school attendance alone can help change the course of their lives! Primarily, it has been said that “Every child is one caring adult away from a success story.” Attending a school in which there is at least one adult who cares — whether that is a teacher, school social worker, counselor, principal, or administrative assistant — can cultivate resilience in children.

What you can do – TODAY!Along these same lines, you can choose to be that positive, caring adult in a young child’s life! You can volunteer to be a mentor, classroom aide, a CASA (Court Appointed Special Advocate) for foster youth, work at an after school club, invite your own child’s friends over more often, volunteer in your communities child abuse prevention program, or even be a foster or adoptive parent! You can truly make a difference in a child’s life.

Another big way that you and your family can help a young child, family, or even whole community is by giving, both of your time and finances! Donate to an organization that serves children in poverty, or sign up to volunteer at an event. Some individuals have even gone to their local school district and paid overdue lunch fees for students! Remember, it’s hard to learn when you’re hungry, and food insecurity disproportionately impacts low income families living below the poverty line! To make an effort towards poverty reduction, donate to local food banks, free clothing closets, and diaper banks. Tutoring children in need is also a huge way to help children’s lives and make a difference in reducing the growing poverty rate!

Additionally, we can help achieve extreme poverty reduction by spreading awareness of the effects of poverty on children! Talk to your friends, family, government representatives, school officials, and community members about the harmful effects and impacts of growing up in poverty. Be an advocate for children’s lives by supporting children’s rights, change, and hope in your own community and neighborhood! Share this article on social media, as well as factsheets, and other information about childhood poverty and how widespread it truly is in the United States. No child should grow up in poverty – let’s all do our part to help!

Be an advocate for children’s lives by supporting children’s rights, change, and hope in your own community and neighborhood! Share this article on social media, as well as factsheets, and other information about childhood poverty and how widespread it truly is in the United States. No child should grow up in poverty – let’s all do our part to help!

https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/five-numbers-to-remember-about-early-childhood-development/

http://people.auc.ca/brodbeck/4007/article9.pdf

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27244844

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26787551

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9299837

https://www.samhsa.gov/capt/practicing-effective-prevention/prevention-behavioral-health/adverse-childhood-experiences

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15982107

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. By continuing to use our site you agree to our Privacy Policy. ACCEPT

ACCEPT

5 Ways Poverty Harms Children

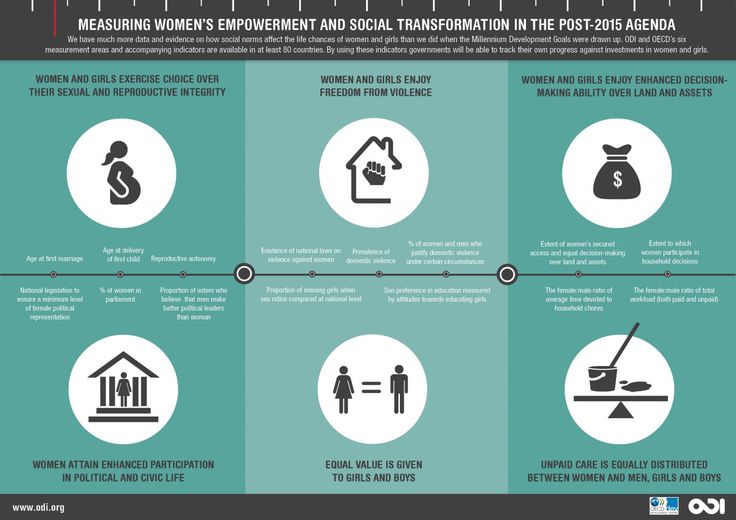

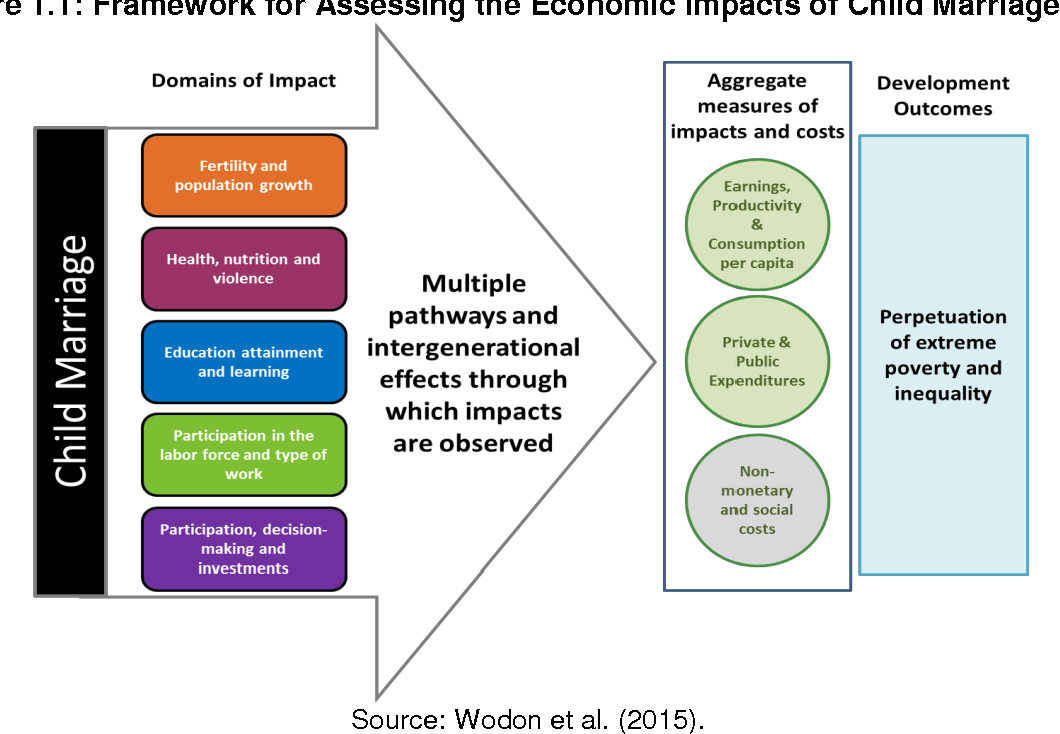

Fifty years ago, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared a War on Poverty, and introduced legislation aiming to reduce the national poverty rate. As shown in this chart, in 1964, 23 percent of U.S. children lived in poverty. Since then, the rate has fluctuated quite a bit, but the latest child poverty rate (22 percent, for 2012) is barely lower than it was when the War began. Poverty rates for black and Hispanic children (at 39 and 34 percent, respectively) are even higher. Below, we highlight five ways poverty is harmful to children, and why it’s imperative to continue this fight.

1 Poverty harms the brain and other body systems.

How developmental science understands child poverty has changed a great deal in recent years. Poverty, for children, is not simply a matter of getting by with less of the essentials of life. Particularly at its extremes, poverty can negatively affect how the body and mind develop, and can actually alter the fundamental architecture of the brain. Children who experience poverty have an increased likelihood, extending into adulthood, for numerous chronic illnesses, and for a shortened life expectancy.

Children who experience poverty have an increased likelihood, extending into adulthood, for numerous chronic illnesses, and for a shortened life expectancy.

2 Poverty creates and widens achievement gaps.

Children growing up in poverty, when compared with their economically more secure peers, fall behind early. Starting in infancy, gaps are evident in key aspects of learning, knowledge, and social-emotional development. When left unaddressed, these early gaps become progressively wider. Early optimal development tends to open doors to further optimal development, while impoverished development tends to close those doors. So, poor children lag behind their peers at entry to kindergarten, in reading ability at the end of third grade, in the important self-monitoring skills often called “executive functioning,” and in school attendance in eighth grade. Poor children are more likely to drop out of school, or fail to obtain post- secondary education.

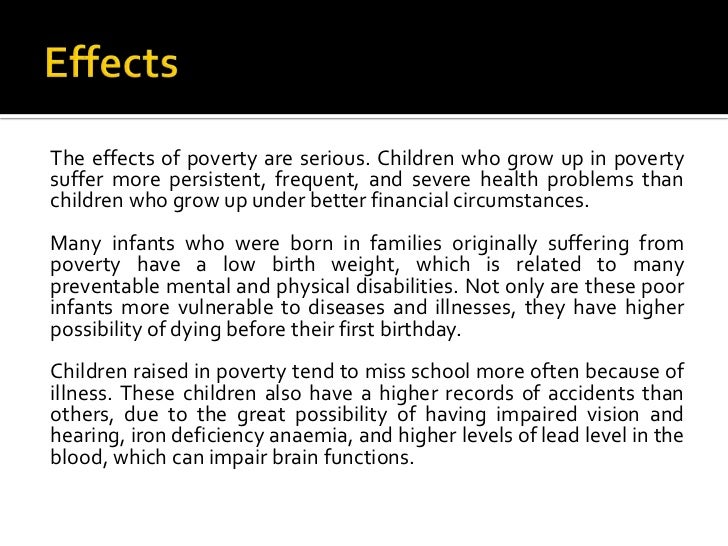

3 Poverty leads to poor physical, emotional, and behavioral health.

Even when poverty doesn’t directly alter human biological systems, we know that growing up poor increases the likelihood that children will have poor health, including poor emotional and behavioral health. Poverty works in multiple ways to constrict children’s opportunities and expose them to threats to well-being. Poor children are more likely to lack “food security,” as well as have diets that are deficient in important nutrients. Rates of several chronic health conditions, such as asthma, are higher among poor children. They areless likely to receive preventive medical and dental care.

4 Poor children are more likely to live in neighborhoods with concentrated poverty, which is associated with numerous social ills.

While direct causal links between neighborhood poverty and children’s outcomes are challenging to identify in research, scholars have found that growing up in neighborhoods with concentrated poverty is associated with negative academic outcomes, more social and behavioral problems, and poorer health and physical fitness outcomes. Poor children are more likely to live in neighborhoods where they are exposed to environmental toxins and other physical hazards, including crime and violence. In the case of violence, evenindirect exposure — witnessing, or simply hearing of its occurrence — has been linked with adverse developmental outcomes. Poor children are also disproportionately likely to attend schools in districts with fewer resources, with facilities that are grossly inadequate, and with school leadership that is more transient.

Poor children are more likely to live in neighborhoods where they are exposed to environmental toxins and other physical hazards, including crime and violence. In the case of violence, evenindirect exposure — witnessing, or simply hearing of its occurrence — has been linked with adverse developmental outcomes. Poor children are also disproportionately likely to attend schools in districts with fewer resources, with facilities that are grossly inadequate, and with school leadership that is more transient.

5 Poverty can harm children through the negative effects it has on their families and the home environment.

While the strengths of poor families are often overlooked, parents experience numerous challenges that can affect their own emotional well-being, as well as their children’s. Poor parents report higher stress, aggravation, and depressive symptoms than do higher-income parents. Parents with scarce economic resources face difficulty planning, preparing, and providing for their families’ material needs. Children in poor families have fewer books and other educational resources at home, and they are less likely to experience family outings, activities, and programs that can enrich learning opportunities. Their families are more likely to experience housing instability. Direct evidence that additional income can improve children’s lives comes from several experimental evaluations: programs that increased family income showed improvements in children’s social and academic outcomes.

Children in poor families have fewer books and other educational resources at home, and they are less likely to experience family outings, activities, and programs that can enrich learning opportunities. Their families are more likely to experience housing instability. Direct evidence that additional income can improve children’s lives comes from several experimental evaluations: programs that increased family income showed improvements in children’s social and academic outcomes.

Children from poor families are retarded in brain development

There is growing evidence that poverty affects the physical development of a child's brain. A study by American scientists for the first time aims to establish a causal relationship between the social position of parents and the development of the brain of their children, reports The Guardian.

Read Hi-Tech at

Columbia University's Neurocognitive and Development Laboratory, led by Dr. Kimberley Noble, is a center of excellence for research into how poverty affects the brains of the next generation. “For decades, sociologists have looked at socioeconomic backgrounds and their impact on cognition, using IQ tests, for example,” says Noble. As a result of the research, it turned out that children from poor families do not cope with such cognitive tasks as remembering faces, pictures, and vocabulary tests.

“For decades, sociologists have looked at socioeconomic backgrounds and their impact on cognition, using IQ tests, for example,” says Noble. As a result of the research, it turned out that children from poor families do not cope with such cognitive tasks as remembering faces, pictures, and vocabulary tests.

In 2005, Dr. Noble and colleagues recruited 60 Philadelphia elementary school children (30 middle-class children and 30 who were at or just above the poverty line) and gave them a series of cognitive tests, each linked to a specific department. brain. Among other things, the tests measured the development of language skills and the executive functions of the brain - a set of mental processes responsible for working memory, reasoning and self-control. It turned out that children from low-income families performed significantly worse on tests than their middle-class peers.

Physiologists are also sounding the alarm. In another study, neuroscientist Martha Farah examined 283 MRI scans. As a result, she found that children from poor, less educated families tend to have thinnings in the prefrontal cortex—a part of the cortex strongly associated with the executive functioning of the brain—compared to more affluent children. This may explain the poor academic performance and low IQ of underprivileged children.

As a result, she found that children from poor, less educated families tend to have thinnings in the prefrontal cortex—a part of the cortex strongly associated with the executive functioning of the brain—compared to more affluent children. This may explain the poor academic performance and low IQ of underprivileged children.

The Developing Human Connectome Project

To prove the relationship, Dr. Noble and several other researchers are designing a nationwide study that will include 1,000 low-income families. Families will be divided into two groups: one will receive a cash payment of $333 per month, and the rest will receive $20 per month. The new study will run for five years, with payments starting shortly after the children are born and continuing until the children are three years old. Their maturation will take place under the supervision of researchers.

These studies show that there is no specific factor responsible for brain and intellectual deficiencies, but rather poverty in general. If scientists can prove that poverty affects the physiology of the brain, it will help bring the problem to the attention of the government.

If scientists can prove that poverty affects the physiology of the brain, it will help bring the problem to the attention of the government.

“In 20-30 years the US will stop using sex for reproduction”

Case studies

Dutch scientists have discovered 40 genes responsible for the development of intelligence. In the long term, this will help to understand whether the intellectual evolution of man continues.

Poverty and the Brain: How Lack of Money Affects Development - Ideonomics - Smart about the Essentials

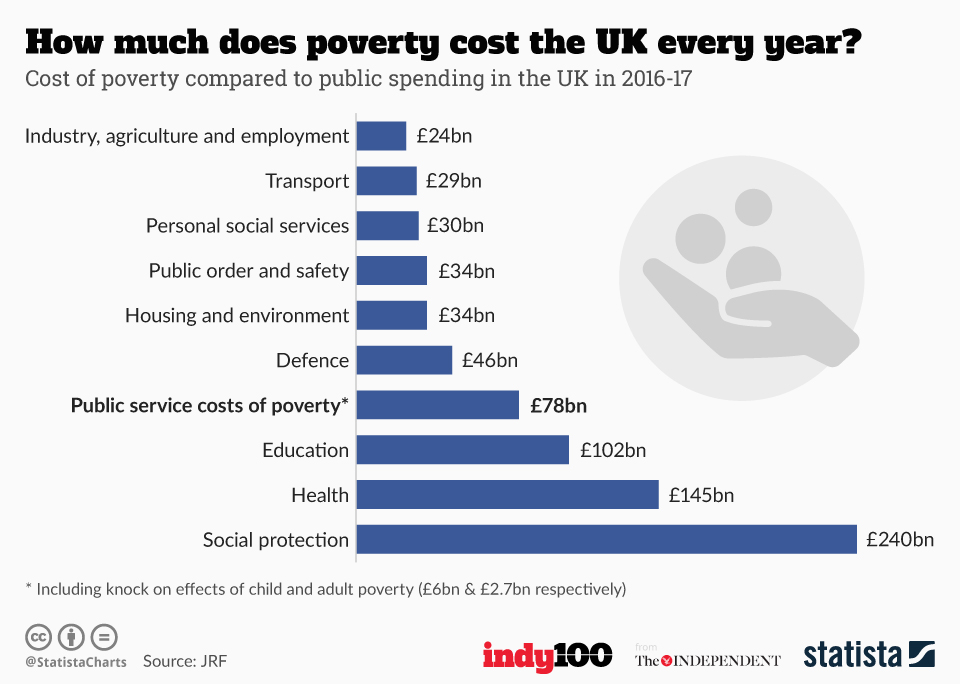

Photo: Santiago Sito/FlickrFor a "rich" country by world standards, there are too many poor people in the UK. 14 million people - a fifth of the population - live in poverty. Of these, 1.5 million do belong to the category of beggars who cannot afford even the most necessary things for life.

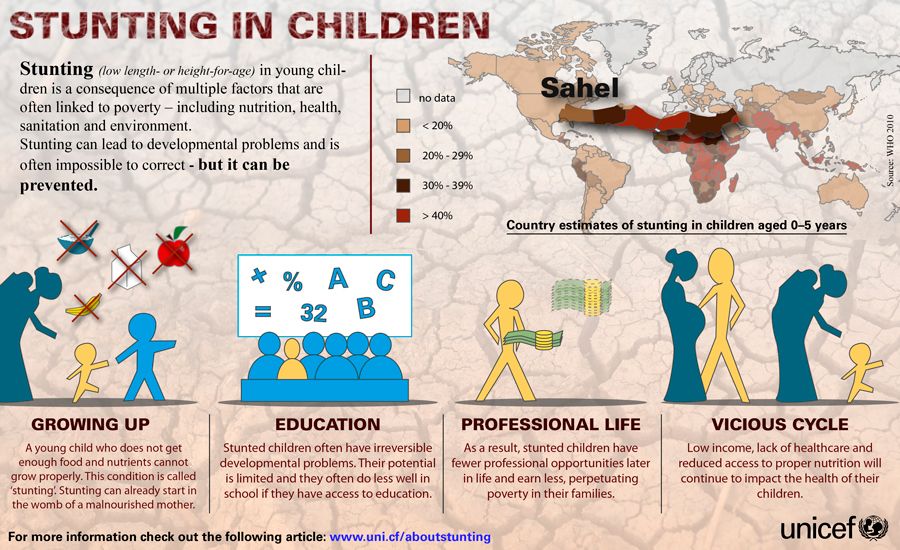

Poverty affects children far beyond material disadvantage. “Children perceive poverty as an environment that is detrimental to their mental, physical, emotional and spiritual development,” notes UNICEF. Clearly, psychological research is important in this area, especially how poverty affects children and adults.

Clearly, psychological research is important in this area, especially how poverty affects children and adults.

The psychological consequences for children growing up in poverty are severe. A 2009 study published in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience found striking differences in prefrontal cortex activity among children aged 9-10 years old, differing only in their socioeconomic status, which is critical for complex cognition. The response of the prefrontal cortex of many poor children to various tests resembled that of some stroke victims. "Children with lower socioeconomic levels exhibit physiological brain patterns similar to those who suffered frontal lobe damage in adulthood," said UC Berkeley psychology professor and lead researcher Robert Knight.

A life of poverty can cause problems with self-regulation and behavioral difficulties (which have been reported among poorer children), as well as difficulties in reasoning. “This is a wake-up call,” Knight continues. “It's not just that these kids are poor and more likely to get health problems, but that their brains can't fully develop because of the stressful and rather poor environment associated with low socioeconomic status: less books, less reading, less games, less museum visits.”

“It's not just that these kids are poor and more likely to get health problems, but that their brains can't fully develop because of the stressful and rather poor environment associated with low socioeconomic status: less books, less reading, less games, less museum visits.”

Since then, many other studies have shown that poverty damages the brains of children. In 2014, experiments led by Michelle Tin revealed a clear deficit in verbal and visuospatial memory among poor children. A year later, an article in JAMA Pediatrics noted "unstable brain development" in low-income children. These developmental delays in the frontal and temporal lobes were associated with significantly lower performance on math and reading tests. The researchers found that the development of the hippocampus, which is responsible for memory, was particularly affected by the stress experienced by these children.

This influence can be long lasting. A longitudinal study published by Gary Evans in PNAS in 2016 found that people who were poor as children were more likely to have memory deficits and psychological disorders. Meanwhile, a 2019 long-term study of nearly 4,000 families in Canada by Paul Hastings found that living in poor urban neighborhoods during childhood is associated with a double risk of developing psychosis spectrum disorders in adulthood.

Meanwhile, a 2019 long-term study of nearly 4,000 families in Canada by Paul Hastings found that living in poor urban neighborhoods during childhood is associated with a double risk of developing psychosis spectrum disorders in adulthood.

These studies paint a very bleak picture of the effects of poverty. But not all children are equally affected by poverty—for example, not every needy child has been shown to be deficient in prefrontal cortex function. This suggests that there are also protective factors. Further research in this area suggests that overall stress levels as well as the behavior of loved ones play a big role.

Something as simple as planting more trees in schools in disadvantaged areas can help, according to a 2018 University of Illinois study published by a group at the University of Illinois. Ming Kuo and her colleagues assessed the number of trees and the level of grass cover in the schoolyards of 318 elementary schools (in which 87% of children were in the low-income family category) and found a correlation with math and reading scores: the more trees, the better the results. Referring to other work on the relationship between the number of trees and academic achievement, Kuo believes that there is a significant relationship between the two. “If you don't provide air conditioning or heating in a school, it's not surprising that children will react the same way. But for the first time, we began to suspect that the lack of greens could partly explain their poor test scores,” she says.

Referring to other work on the relationship between the number of trees and academic achievement, Kuo believes that there is a significant relationship between the two. “If you don't provide air conditioning or heating in a school, it's not surprising that children will react the same way. But for the first time, we began to suspect that the lack of greens could partly explain their poor test scores,” she says.

A British study published the same year confirmed these findings. It involved 4,758 11-year-olds living in urban areas of England and found that children living in greener areas performed better on tests of spatial working memory (an effect that persisted in both high and low areas). "Our findings suggest a positive role for green space in cognitive functioning," says researcher Eirini Flury from University College London. What could this role be? Perhaps greenery calms the brain and restores the ability to concentrate.

Adjusting the lives of the families of those children who grow up in poverty should also help. The team that has studied prefrontal cortex deficits believe it could theoretically be prevented or reversed. It was previously found that children from poor families hear 30 million fewer words by their fourth birthday than children from middle-class families. The team notes that simple conversations with children can increase the performance of the prefrontal cortex, so they say the key to changing developmental outcomes is to simply emphasize to parents the importance of communicating with their children.

The team that has studied prefrontal cortex deficits believe it could theoretically be prevented or reversed. It was previously found that children from poor families hear 30 million fewer words by their fourth birthday than children from middle-class families. The team notes that simple conversations with children can increase the performance of the prefrontal cortex, so they say the key to changing developmental outcomes is to simply emphasize to parents the importance of communicating with their children.

Children raised in families of low socioeconomic status are more likely to develop chronic diseases in adulthood, but again this is not inevitable. A caring, considerate, and emotionally supportive mother can mitigate the impact of poverty on physical health, according to a 2011 study by G.E. Miller and published in Psychological Science.

Sophie Wickham of the University of Liverpool argues in a 2014 paper that how people perceive levels of stress, trust, and social support influences the impact of poverty on levels of depression and paranoia. This highlights the potential role of the community in poverty alleviation for its individual members. A study in two Birmingham boroughs found that community resilience to hardships such as unemployment and low income could be improved, and that this primarily depended on relationships “not just between members of the community, but also between organizations, especially between the sector volunteers, the local economy and the public sector.”

This highlights the potential role of the community in poverty alleviation for its individual members. A study in two Birmingham boroughs found that community resilience to hardships such as unemployment and low income could be improved, and that this primarily depended on relationships “not just between members of the community, but also between organizations, especially between the sector volunteers, the local economy and the public sector.”

Of course, the most obvious way to deal with the negative psychological effects of poverty is to deal with poverty itself.

According to research published in PNAS last year, easing financial hardship can make a big difference. This work, which studied low-income people who were categorized as "chronically indebted", found that one-off debt relief reduced participants' anxiety and improved their cognitive functioning. This allowed them to make better financial decisions months later. The researchers argue that thoughts and worries about unpaid debts are so draining that they drive a person into a poverty trap.