How does family separation affect a child

What Are the Long-Term Effects of Separating Immigrant Children from Their Parents?

What Are the Long-Term Effects of Separating Immigrant Children from Their Parents?

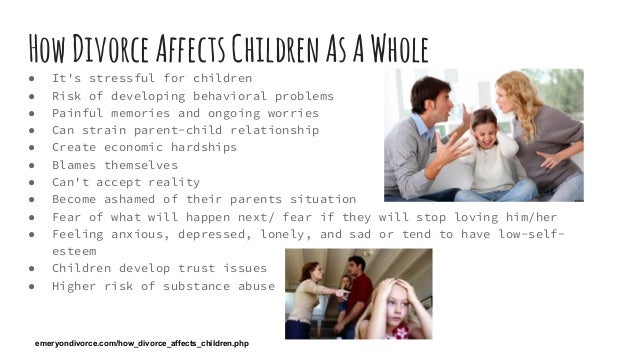

In the debate over the U.S. policy of separating detained immigrant children from their parents at the Mexican border, pediatric health care providers warn that the trauma will have long-term effects on the families, especially the children.

I recently talked with two of my colleagues at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) about the physical and mental impact such an experience can have on children and how parents and other caregivers can help them heal. Dr. Mary Fabio, director of the Refugee Health Program at CHOP, and Dr. Nancy Kassam-Adams, co-director of CHOP’s Center for Pediatric Traumatic Stress and the associate director of Behavioral Research at the Center for Injury Research at CIRP, offered insights about the challenges traumatized families face upon being reunited.

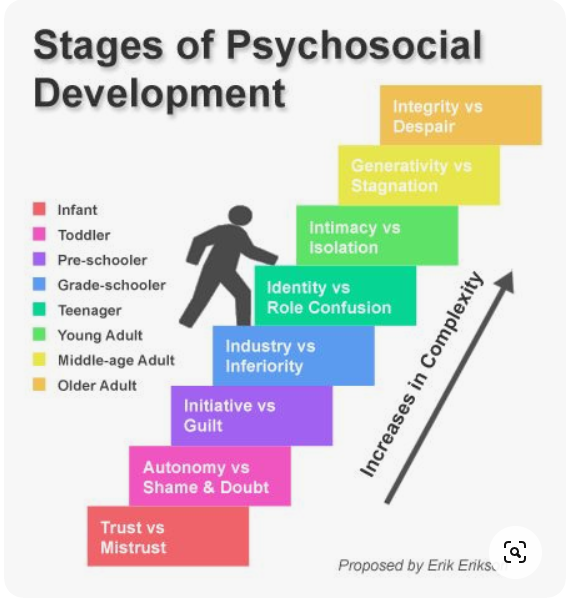

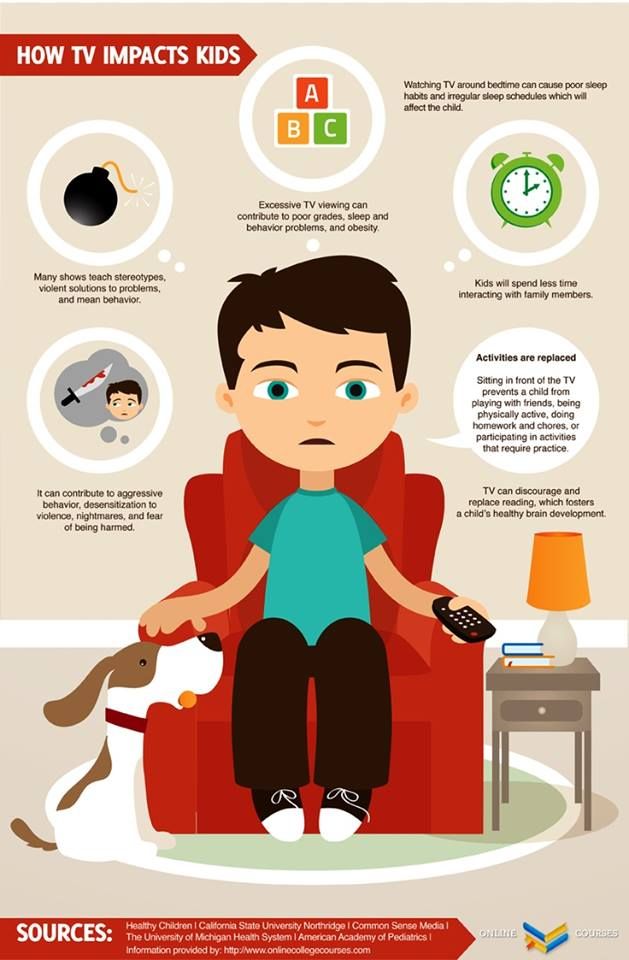

"The stress of being separated from their parents and surrounded by strangers in a strange place takes a physical and mental toll on children, and can even change their 'brain architecture,'" said Dr. Fabio. In fact, “it’s really hard to separate the mental and physical health aspects.”

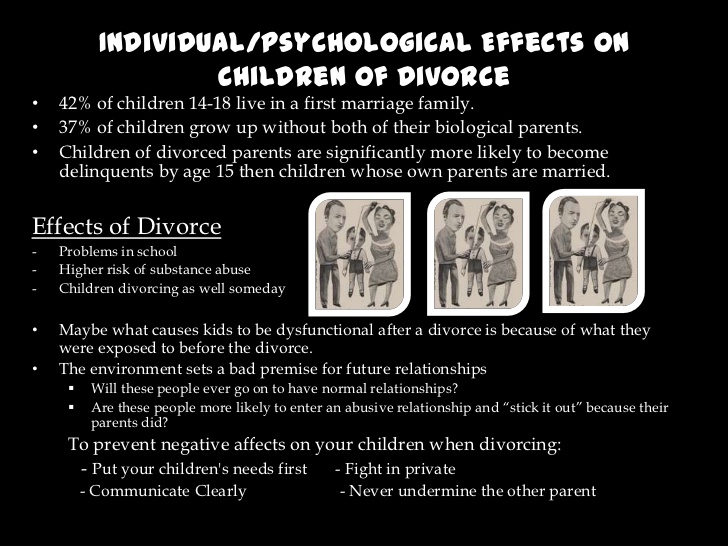

"For younger children, the trauma of being separated for their parents can result in attachment issues and lead to long-term emotional and cognitive problems," Dr. Fabio said. "Children who are separated from their parents at an older age often experience problems in school and may exhibit regressive behavior. Older children may develop anxiety, depression or behavioral problems. Some may even self-harm in order to cope," she added.

“Detention is a very stressful experience for children even when they are allowed to remain with their parents,” said Dr. Fabio. “Detention is not good in general.”

Fabio pointed out that in 2017 the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) stated its opposition to the conditions in which immigrant children are detained by the U.S.

More specifically, in June the AAP issued a statement in support of ending the forced separation of immigrant children from their parents. “The [AAP] agrees with ending this abhorrent practice, which drew widespread outcry among pediatricians, advocates, and the American public. Families should remain together,” the organization said. “As pediatricians, we know children fare best in community settings, under the direct care of parents who love them.”

“The [AAP] agrees with ending this abhorrent practice, which drew widespread outcry among pediatricians, advocates, and the American public. Families should remain together,” the organization said. “As pediatricians, we know children fare best in community settings, under the direct care of parents who love them.”

But for those children who have already endured separation from their parent—or continue to be—the road ahead will be a difficult one.

“Even when kids are reunited with their parents, complicating matters is that the parents may have been traumatized as well by their own experiences,” said Dr. Kassam-Adams.

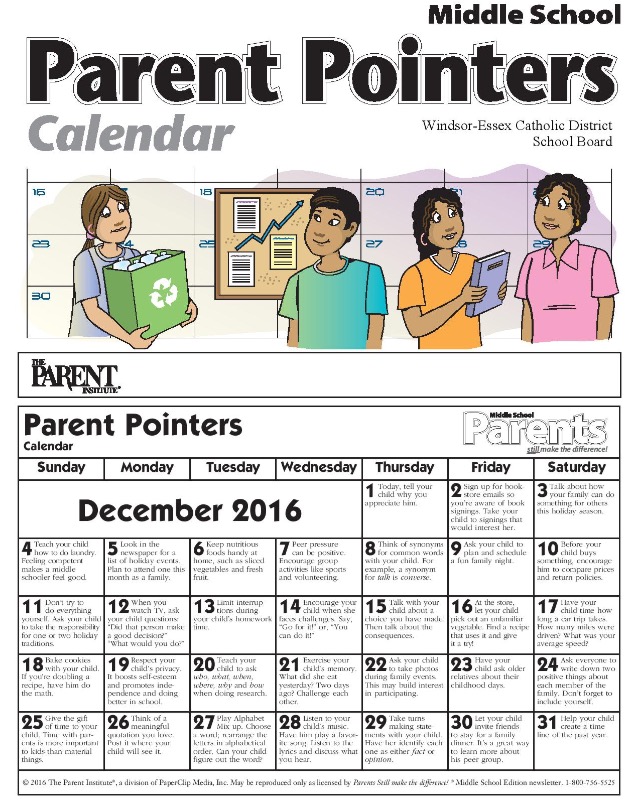

"To help children deal with the effects of the separation, parents and/or other caregivers should help them understand what happened to their family and reassure them that the experience wasn’t their fault," Dr. Kassam-Adams advised.

"Also important is finding ways to create routines and do things together as a family, like eating meals or playing games the child enjoys," Dr. Kassam-Adams said. "Family-bonding time may include things the family did together in the past or new activities to help reestablish a feeling of normalcy," she added.

Kassam-Adams said. "Family-bonding time may include things the family did together in the past or new activities to help reestablish a feeling of normalcy," she added.

"Children recovering from traumatic separation from their parents may be withdrawn, angry or even act aggressively towards parents and caregivers. When the adults in their lives understand where that behavior is coming from," said Kassam-Adams. They can respond with empathy even as they help the child gain control of problematic behaviors. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network has provided guidance and tips for caregivers in English and in Spanish.

She points out that, unfortunately, because the separation of families is a “human-created trauma,” it may take some time for children to regain trust in the adults around them.

US: Family Separation Harming Children, Families

Click to expand Image

Migrant families cross the Rio Grande to get across the border into the United States, to turn themselves in to authorities and ask for asylum, next to the Paso del Norte international bridge, near El Paso, Texas, Friday, May 31, 2019. © 2019 Christian Torrez/AP Photo © 2019 Christian Torrez / AP Photo

© 2019 Christian Torrez/AP Photo © 2019 Christian Torrez / AP Photo

(Washington, DC) – United States officials are separating migrant children from their families at the border, causing severe and lasting harm, Human Rights Watch said today. The US House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Reform will hold hearings on the government’s family separation policy on July 12, 2019.

Human Rights Watch interviews and analysis of court filings found that children are regularly separated from adult relatives other than parents. This means that children are often removed from the care of grandparents, aunts and uncles, and adult siblings even when they show guardianship documents or written authorization from parents. Parents have also been forcibly separated from their children in some cases, such as when a parent has a criminal record, even for a minor offense that has no bearing on their ability as caregivers. As a result, in cases reviewed by Human Rights Watch, children as young as 5 have been held in Border Patrol holding facilities without their adult caregivers.

“Congressional hearings are the first step in accounting for and addressing the enormous harms inflicted on children and their families in holding cells at the border,” said Michael Garcia Bochenek, senior children’s rights counsel at Human Rights Watch. “Senior immigration officials should take this opportunity to acknowledge these serious concerns and announce an immediate end to family separation.”

A 5-year-old Honduran boy held in the Clint Border Patrol Station in Texas told lawyers that when he and his father were apprehended at the border, “the immigration agents separated me from my father right away. I was very frightened and scared. I cried. I have not seen my father again.” He did not know how long he had been separated from his father: “I am frightened, scared, and sad.” In another case, an 8-year-old Honduran boy detained in Clint with his 6-year-old sister said, “They took us from our grandmother and now we are all alone.” He did not know how long they had been apart from their grandmother: “We have been here a long time. ”

”

Human Rights Watch interviewed 28 children and adults, and reviewed an additional 55 sworn declarations filed in court and taken from children and adults placed in holding cells at the Texas border between June 10 and 20, 2019. Human Rights Watch identified 22 cases in which one or more children described forced separation from a family member, usually within the first few hours after apprehension. Three Human Rights Watch lawyers took part in the teams that collected these declarations to make sure conditions were in compliance with a settlement agreement. The agreement sets the standards for conditions in which migrant children are held.

No federal law or regulation requires children to be systematically separated from extended family members upon apprehension at the border, and there is no requirement to separate a child from a parent unless the parent poses a threat to the child.

US border officials are required to identify children who are victims of trafficking – such as children who are transported for the purpose of exploitation – and to take steps to protect them, but all of the cases of family separation reviewed by Human Rights Watch involved children travelling with relatives to seek asylum, join other family members, or both, with no indication that they were trafficked.

In June 2018, the Trump administration announced an end to the government’s forcible family separation policy after images of children in cages, leaked recordings of border agents mocking crying children, and other news of the extent and impact of the administration’s policy prompted a public outcry.

The cases that Human Rights Watch reviewed demonstrate that forcible family separation is continuing. For relatives other than parents, forcible separation appears to be a routine practice, and for many children, separation from relatives who have served as primary caregivers can be as traumatic as separation from a parent.

Between July 2018 and February 2019, US border officials separated at least 200 children from parents. They often failed to give a clear reason for the separation, a New York Times review found; in some cases, agents separated families because of minor or very old criminal convictions.

Immigration authorities have never disclosed the number of relatives other than parents forcibly separated from children at the border.

Forcible separation is traumatic for children and adults alike. Separated children interviewed by Human Rights Watch described sleepless nights, difficulties in concentrating, sudden mood shifts, and constant anxiety, conditions they said began after immigration agents forcibly separated them from their family members.

Most separated children we interviewed reported having parents or other relatives in the US, but family members with whom Human Rights Watch spoke said border agents made no attempt to contact them.

To prevent harm to children and uphold the principle of family unity, Human Rights Watch urges that:

- The acting commissioner of US Customs and Border Protection should direct immigration agents to keep families together unless an adult presents a clear threat to a child or separation is otherwise in a child’s best interests. That determination should be made by a licensed child welfare professional, such as a social worker, psychologist, or psychiatrist with training and competence to work with children.

- The inspector general’s office of the Department of Homeland Security should systematically review all instances of family separation, including of family members other than parents, to determine whether separation was in the child’s best interests.

- Congress should prohibit the separation of families, including of children and their siblings, grandparents, aunts and uncles, or cousins, except when separation is in an individual child’s best interests.

“The border agency needs clear direction from the administration to end forcible family separation and other abusive practices,” Bochenek said. “And it’s up to Congress to provide the oversight to make sure the border agency complies.”

“Zero Tolerance” and Systematic Family Separation

In May 2018, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced a “zero tolerance” policy under which parents – including those seeking asylum – would be prosecuted for illegal entry, and their children forcibly removed from their parents’ custody and reclassified as “unaccompanied. ” White House chief of staff John Kelly told National Public Radio that month: “The children will be taken care of – put into foster care or whatever.”

” White House chief of staff John Kelly told National Public Radio that month: “The children will be taken care of – put into foster care or whatever.”

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) brought a court case to compel the US government to disclose how many children were separated from their parents under the policy. Authorities struggled to provide this information, eventually telling the court that more than 2,700 children had been forcibly separated from their parents in May and June 2018. On June 20, 2018, President Donald Trump issued an executive order that he said ended his administration’s forcible family separation policy.

A government report published in January 2019 found that “thousands” more children had been forcibly separated from their parents, and beginning much earlier, than the administration had previously acknowledged. A leaked draft policy document confirmed administration officials were discussing a family separation policy as of late 2017.

The government has acknowledged that forcible family separations continued after the executive order. In a court filing this February, it reported at least 245 separations between June 26, 2018, and February 5, 2019. By late May, the number had risen to 700, the ACLU reported. In some cases these were triggered by minor, nonviolent offenses – a 20-year-old nonviolent robbery conviction in one case and possession of a small amount of marijuana in another, in cases reviewed by the New York Times. Most of these cases did not list detailed reasons for the separation.

In a court filing this February, it reported at least 245 separations between June 26, 2018, and February 5, 2019. By late May, the number had risen to 700, the ACLU reported. In some cases these were triggered by minor, nonviolent offenses – a 20-year-old nonviolent robbery conviction in one case and possession of a small amount of marijuana in another, in cases reviewed by the New York Times. Most of these cases did not list detailed reasons for the separation.

These figures do not include the number of children who were forcibly separated from relatives other than parents.

Children Distraught Without Their Parents

Children described days of not knowing where their parents had been taken and when, if ever, they would be reunited. For example, a 17-year-old boy from El Salvador, interviewed in Clint, said that he and his mother had crossed an international bridge 16 days before. He said:

We presented ourselves to border patrol agents, who then separated us. They refused to explain why they were doing so. Since that moment, I have not known where my mother is. I have not known if my mother was in the United States or elsewhere, or even if she was alive. I have been extremely worried about her.

They refused to explain why they were doing so. Since that moment, I have not known where my mother is. I have not known if my mother was in the United States or elsewhere, or even if she was alive. I have been extremely worried about her.

Children Taken from Grandmothers, Aunts, and Uncles

A 12-year-old girl who travelled to the US with her grandmother and 8 and 4-year-old sisters said that border agents woke them up at 3 a.m. two days before she spoke with lawyers:

[T]he officers told us that our grandmother would be taken away. My grandmother tried to show the officers a paper signed by my parents saying that my grandmother had been entrusted to take care of us. The officers rejected the paperwork, saying that it had to be signed by a judge. Then the officers took my dear grandmother away. We have not seen her since that moment. . . . Thinking about this makes me cry at times. . . . My sisters are still upset because they love her so much and want to be with her.

In another case, a woman who had raised her niece said border agents told her the notarized guardianship papers she showed them were “no good in the United States.” Agents told her she should expect to be separated from her niece once they were transferred from the Ursula Processing Center in McAllen, Texas, the facility frequently called the perrera, meaning “dog kennel,” because of its chain-link-fence holding pens.

An 11-year-old boy who travelled to the US with his 3-year-old brother and their 18-year-old uncle to escape gang violence in Honduras said that border agents separated him and his brother from their uncle when they were apprehended, about three weeks before Human Rights Watch spoke to him in Clint:

The border agents made us sit in a circle, then we were placed on trucks and transported. I don’t know to where. My uncle identified himself as our uncle. The agents told us we would be separated. This was so sad for me. I don’t know where they sent my uncle. We were not allowed to say goodbye to each other.

We were not allowed to say goodbye to each other.

Human Rights Watch identified many other such cases in our own interviews and the declarations we reviewed. For instance:

- A 12-year-old girl from Guatemala said that border agents separated her from her aunt and cousin when the three entered the United States at the beginning of June, 15 days before she spoke with lawyers while in the Clint border station.

- An 8-year-old boy told lawyers he came to the United States with his aunt, who had been taking care of him back home in Guatemala. He said that after border agents separated him from his aunt three days earlier, “I cried and they did not tell me where I was going.”

- A 12-year-old girl from El Salvador said she and her 7-year-old sister were separated from their grandmother the previous day, after they crossed into the United States and reported to Border Patrol officers.

Siblings Forced Apart

A 17-year-old girl from El Salvador told lawyers she entered the United States with her 8-month-old son and her older sister. Border agents “separated [my sister and me] shortly after we arrived in the US about three weeks ago and I have not been allowed to speak with her ever since.”

Border agents “separated [my sister and me] shortly after we arrived in the US about three weeks ago and I have not been allowed to speak with her ever since.”

A 16-year-old girl from El Salvador, interviewed in Clint, said that she and her 5-month-old daughter were separated from her 20-year-old sister and her sister’s 3-year-old son when they were apprehended three days before she spoke to lawyers in Clint. Border agents later told her that her sister and nephew had been released and sent to live with family members.

A 14-year-old Guatemalan girl said that immediately after she and her 18-year-old sister crossed the river to enter the United States – she was not sure how long ago – border agents “lined us up and checked our skin and our hair. That is when they took my sister away from me and now I’m very worried about her. I don’t know where she is or if she is ok.”

Adult Caregivers Returned to Mexico Without Children

Human Rights Watch has previously identified family separations occurring in the context of the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) or “Remain in Mexico” policy, under which tens of thousands of primarily Latin American asylum seekers have been returned to Mexico to wait while their claims are pending in the United States. In the context of the MPP, agents separate families who had been traveling together at the border. Children, including some with mental health concerns, were separated from non-parental guardians by Border Patrol, classified as “unaccompanied alien children,” and detained alone. Meanwhile, their adult family members were sent to Mexico for the duration of their asylum cases, which can take months or years. Staying in contact is especially difficult for families separated under the MPP, since those forced to wait in Mexico may not have access to a cell phone or landline.

In the context of the MPP, agents separate families who had been traveling together at the border. Children, including some with mental health concerns, were separated from non-parental guardians by Border Patrol, classified as “unaccompanied alien children,” and detained alone. Meanwhile, their adult family members were sent to Mexico for the duration of their asylum cases, which can take months or years. Staying in contact is especially difficult for families separated under the MPP, since those forced to wait in Mexico may not have access to a cell phone or landline.

Families Split Up During Their Time in Border Holding Cells

If both parents are travelling together, fathers are frequently split from the rest of the family. For example, a 23-year-old Honduran man said he, his wife, and their two children were all in the same border station: “I was separated from my family almost immediately. I have only seen my wife and children one time in the three days that I have been here. ” A 5-year-old girl told lawyers her father was separated from her and her mother when they were held in McAllen.

” A 5-year-old girl told lawyers her father was separated from her and her mother when they were held in McAllen.

Teenagers who are held in the same border station as their parents often stated that they were separated if they and their parents are different genders. In such cases, even though they and their parents are in the same facility, they recounted having little or no contact with their parents. For example:

- A 15-year-old girl from Honduras said that she was separated from her father in the two holding cells where they were detained. “I’m in a mixed unit with fathers and their children, so I’m not sure why I can’t be with my dad,” she told lawyers.

- “I was separated from my mother for five days and I was very frightened because I didn’t know what was happening to me or my mother,” a 16-year-old Guatemalan boy said.

- A 16-year-old Honduran girl said that she and her father were held in separate cells without any contact for two days. “I did not see my father again until .

. . they called us out to be fingerprinted and photographed. We were not allowed to see each other before then even though my father repeatedly requested to see me,” the girl said.

. . they called us out to be fingerprinted and photographed. We were not allowed to see each other before then even though my father repeatedly requested to see me,” the girl said.

Border agents sometimes split children between parents, assigning one or more to each parent during their time in a holding cell. “Our family is kept in separate cells, one son with me and one son with my wife,” a 29-year-old Guatemalan man said. A Honduran woman, also 29, said that when she, her husband, and their two children were apprehended, “[m]y daughter and I were separated from my husband and son almost immediately. I’ve only seen my husband and son one time since we arrived three days ago.”

Some of the children held in border stations have children themselves, and some have travelled to the United States with spouses or long-term partners.

In one such case, a 16-year-old girl said that after she and her fiancé, along with their one-year-old daughter, fled gang violence in El Salvador, border agents separated her fiancé from her and her daughter. She told lawyers:

She told lawyers:

We were all very upset. Our baby was crying. I was crying. My fiancé was crying. We asked the guards why they were taking our family apart, and they yelled at us. They were very ugly and mean to us. They yelled at him in front of everyone to sit down and stop asking questions. We have not seen him since.

In another case, a 15-year-old girl who fled Guatemala with her husband and their 8-month-old son said that they requested asylum at the border crossing: “We told them we were travelling as a family and wanted to [remain] together. However, [my husband] was separated from us, and I do not know where he is now. I have not heard from him and I am worried about him.”

Trauma of Forcible Separation

A 15-year-old Guatemalan boy told Human Rights Watch he felt “really desperate and heartbroken and worried” after he was forcibly separated from his father after border agents apprehended them. He described the two months he had been apart from his father:

It is really difficult to be apart from my dad. I don’t know when I will be able to see him, and it makes me really sad. Because I am thinking about my dad and being apart from him, I have difficulty concentrating in class. It’s hard for me to pay attention to what I should be doing. I feel anxious and worried a lot. There are days I don’t have any appetite. I never had a problem eating before, and I think if I weren’t so sad about being apart from my dad I wouldn’t have a problem with eating now. . . . When I start thinking about what happened, I feel sad and I start to cry. This never happened before. . . . This is new. It’s caused by the stress I’m under now.

I don’t know when I will be able to see him, and it makes me really sad. Because I am thinking about my dad and being apart from him, I have difficulty concentrating in class. It’s hard for me to pay attention to what I should be doing. I feel anxious and worried a lot. There are days I don’t have any appetite. I never had a problem eating before, and I think if I weren’t so sad about being apart from my dad I wouldn’t have a problem with eating now. . . . When I start thinking about what happened, I feel sad and I start to cry. This never happened before. . . . This is new. It’s caused by the stress I’m under now.

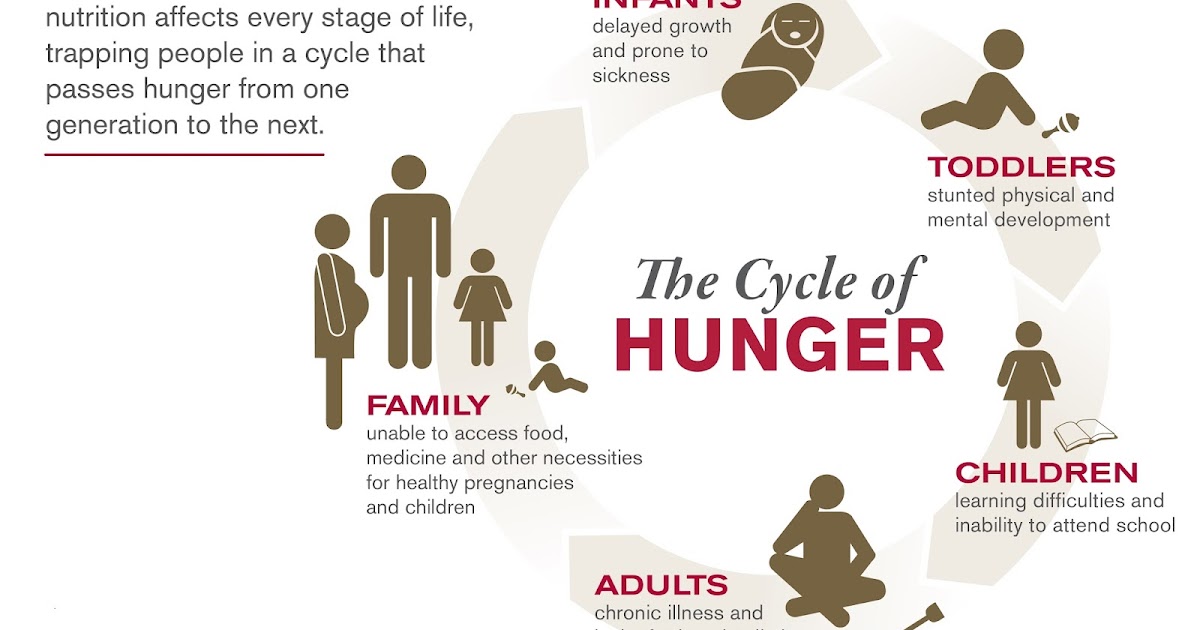

Family separation causes severe and long-lasting harm. As the American Academy of Pediatrics has noted: “highly stressful experiences, like family separation, can cause irreparable harm, disrupting a child’s brain architecture and affecting his or her short- and long-term health. This type of prolonged exposure to serious stress – known as toxic stress – can carry lifelong consequences for children. ”

”

“This kind of stress makes children susceptible to acute and chronic conditions such as extreme anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, hypertension and heart disease,” two pediatricians wrote in the Houston Chronicle last year.

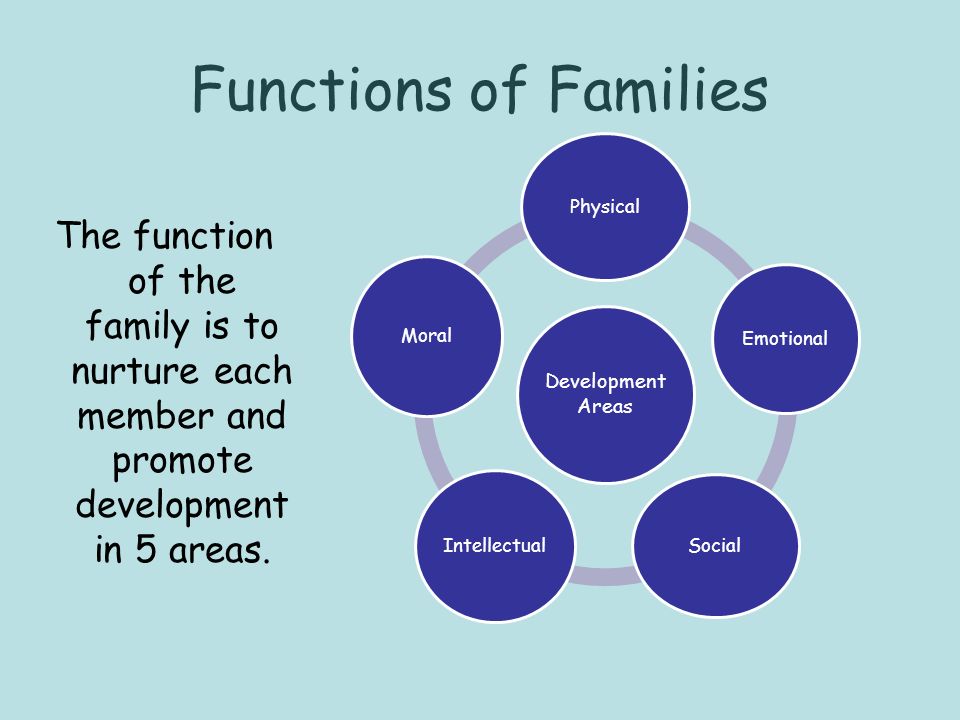

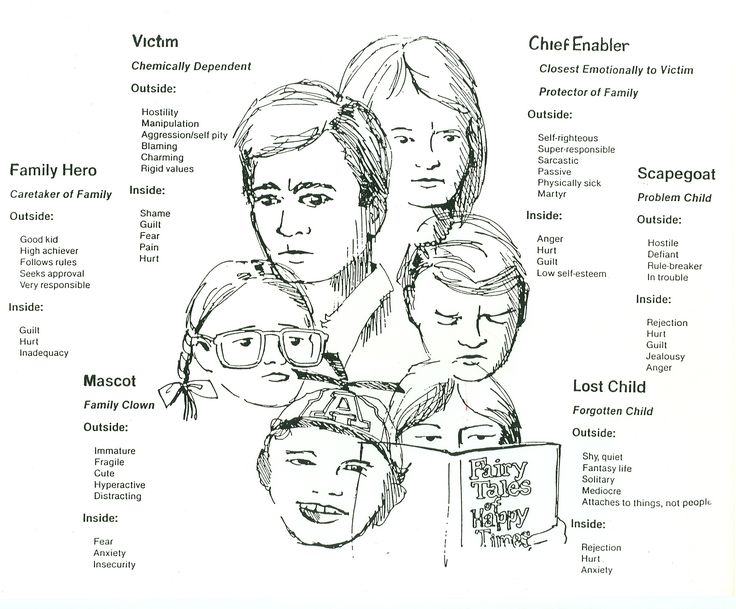

How does the family influence the formation of a child's personality

Why does a child's success in life directly depend on the family environment? Are there criteria by which you can evaluate the relationship between children and parents? What do adults need to know about in order for their child to have their own happy family in the future? These questions are answered by Ekaterina Kushnikova, a psychologist at the Yu.V. Nikulin Center for the Promotion of Family Education.

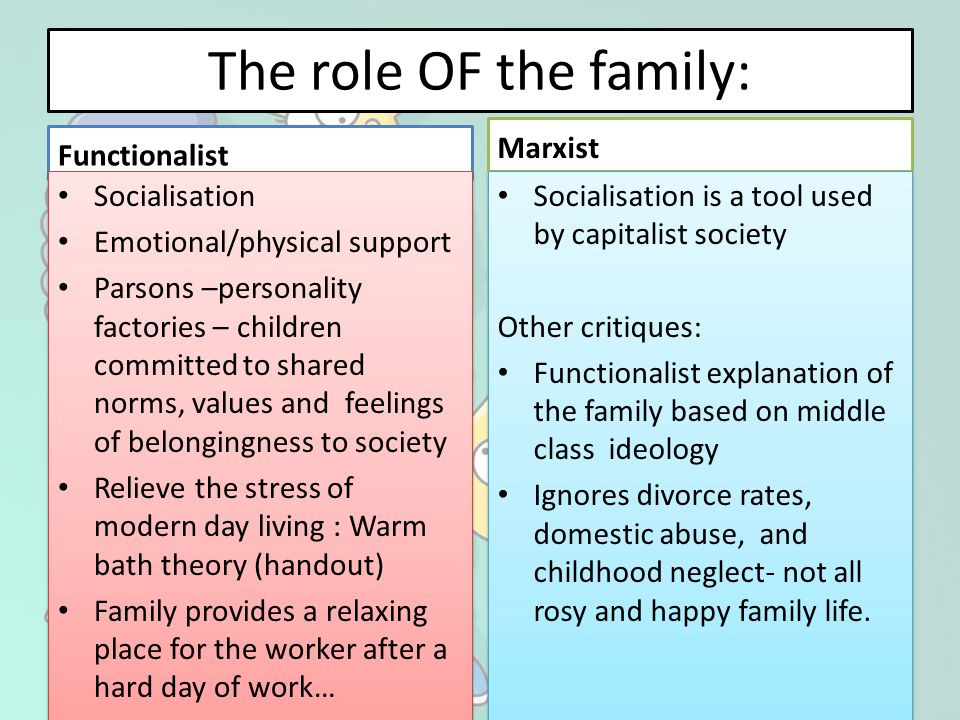

Everything starts with family

Traditionally, the main institution of a person's upbringing, starting from his birth and ending with the formation of a person, is the family. There, the child receives love, support and acceptance from the parents, learns to establish trusting relationships with the closest environment, observes the relationships between family members and takes them as the basis for their future relationships. The family is the basis for the formation of a sense of security, and it is from it that the instillation of certain qualities, ideas and views in the child begins. " It is in the family that the child spends 70% of his time. Children usually tend to copy the behavior of other people, most often those with whom they are in the closest contact ,” notes Ekaterina .

There, the child receives love, support and acceptance from the parents, learns to establish trusting relationships with the closest environment, observes the relationships between family members and takes them as the basis for their future relationships. The family is the basis for the formation of a sense of security, and it is from it that the instillation of certain qualities, ideas and views in the child begins. " It is in the family that the child spends 70% of his time. Children usually tend to copy the behavior of other people, most often those with whom they are in the closest contact ,” notes Ekaterina .

Do no harm!

Children who have a variety of social experiences, are able to cope with difficulties, enjoy diverse social interactions, as a rule, respond positively to changes taking place around them and are able to better adapt to a new environment. If the parents did not pay due attention to the child, did not teach him to adequately respond to stimuli in a given situation, then most likely he will have difficulties with adaptation and problems in communicating with friends and peers.

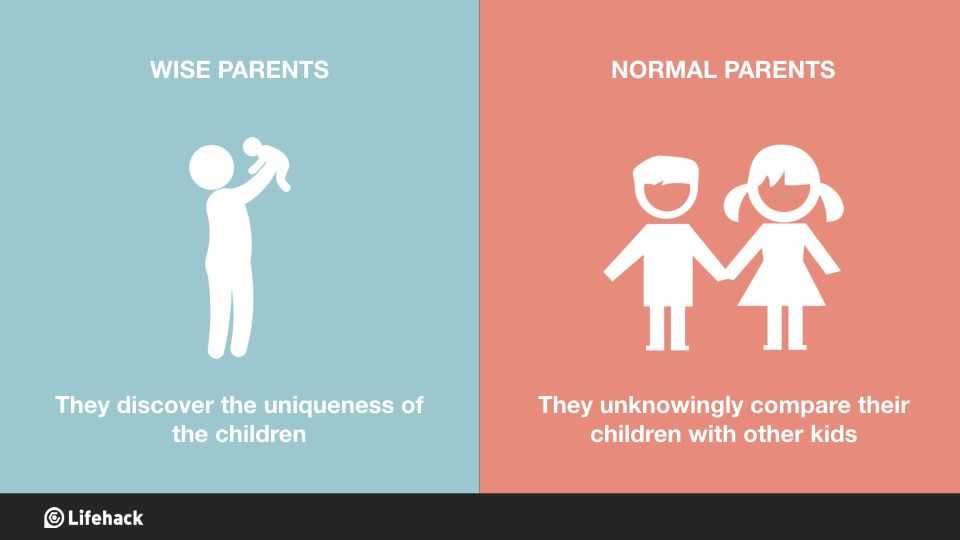

“If a parent is inattentive to the characteristics of a child, is prone to a directive style of upbringing, does not accept his child as he is, but tries to drive him into the framework of his own expectations, most likely, the relationship between such a parent and a child will not become trusting, there will often be conflicts. At the same time, overprotection is also fraught with possible difficulties in socialization. A child whose parents overprotected him will experience anxiety, fear of everything new and unknown. He will be cautious, shy and timid" - says the specialist.

What is needed for the happiness of the child

On the example of families where there were no problems in the relationship between parents and children, a number of criteria can be distinguished:

- Parents accept children as they are.

- Parents try to understand their emotions and states and report them to family members in the correct form, do not hesitate to talk about their feelings.

- Parents respect the needs and requirements of all family members.

- Parents form a relationship with their child through shared activities such as cooking, playing sports, making crafts. They adhere to intra-family traditions: someone leaves the city on holidays, and someone makes toys with their own hands or goes skiing in winter.

- Parents are sincerely interested in the experiences of the child.

- Parents do not form expectations and do not impose them on their child; do not realize their unfulfilled desires through the child.

“If, for example, a mother dreamed of being a ballerina, then it is not at all necessary that her daughter would want to be the prima ballerina of the Bolshoi Theatre. Any violent influence negatively affects the child and, undoubtedly, will further affect the child-parent relationship, ”the specialist notes .

Children are unique and special, and only careful attitude, love and acceptance can become the key to the formation of trusting parent-child relationships and maintaining parental authority in the eyes of the child.

Source

Press Service of the Department of Labor and Social Protection of the Population of the City of Moscow

Influence of the style of family upbringing on the personality of the child

What role a child occupies in the family and how his communication with relatives develops directly depends on what he will become in the future, how he will look at the world and interact with people around him. The family is the cradle of a child's development. Knowing about the different styles of family education, their pros and cons, will allow you to develop your own style and create harmonious family relationships.

The role of the family in shaping the child's personality

Relationships within the family are often perceived by the child as a role model. Most psychologists are sure that it is the flaws of upbringing in childhood that cause difficulties in communication in adulthood. The formation of the personality of the baby directly depends on what model of education is characteristic of his family.

Parents have a huge influence on their baby, since it is they, and not educators, coaches or teachers, who spend most of the time with the child, and their communication model becomes an example to follow.

There are many classifications of family education styles, which are based on various criteria for relationships within the family. In this article we will introduce you to the classifications proposed by the following authors:

- J. Bolnwin;

- G. Craig;

- D. Elder;

- L.G. Sagotovskaya;

- E.G. Eidemiller.

Styles of family education according to J. Baldwin

In the classification of J. Baldwin, two styles of education are distinguished. The division between democratic and controlling style was based on such criteria as the nature of the requirements for the child, the degree of control, emotional support and evaluation.

| Democratic parenting style | Supervisory parenting style |

| There is a high level of trust in the family, everyone is ready to help each other. | A large number of prohibitions and rules. The child is perceived as a member of the family who does not have his own opinion and must listen to his parents in everything. The level of trust in the family is low. |

Research by psychologists has shown that children who were brought up in families with a democratic style of upbringing most often have the following characteristics:

- Tendency to leadership;

- Comprehensive development;

- Social activity;

- Sociability;

- Lack of empathy, lack of altruism.

In families with a controlling parenting style, children grow up:

- Suggestible;

- Obedient;

- Non-initiative;

- Alarming.

Such "pure" family parenting options are rare, most families adhere to a mixed style.

G. Craig's classification of parenting styles

Family parenting styles according to G. Craig can be divided on the basis of two criteria: the degree of parental control and the trusting relationship in the family. The researcher identifies four main styles of education:

- The authoritative style of family education is one of the most harmonious. This parental position is based on trust in your child, but the level of control remains at a high level. As a result, friendly relations are established in the family, and the baby gets enough freedom for self-realization. Children in such families usually grow up purposeful and self-confident, as well as capable of self-control.

- An authoritarian parenting style most often leads to strained intra-family relationships. It is based on total control. A child in a family where this style of upbringing is followed becomes fearful, irritable, aggressive, dependent.

- The liberal style of family education is characterized by a low level of control over children and trusting relationships within the family.

The behavior of the child is practically not regulated, but at the same time, children learn to control themselves. Growing up, children most often become active and creative individuals.

The behavior of the child is practically not regulated, but at the same time, children learn to control themselves. Growing up, children most often become active and creative individuals. - With an indifferent parenting style, the child is given the maximum level of freedom. Adults devote little time to children, so relationships within such families are not warm. Using this style of family parenting is fraught with the risk that the child may grow up hostile and anti-social.

Styles of parenting according to D. Elder

D. Elder distinguishes seven types of family education. The classification criteria are the degree of control and pressure on the child.

| Style of family education | Control level |

| Autocratic parenting style | Maximum (total control and suppression of the will of the child) |

| Authoritarian parenting style | High level of control (parents make decisions, but the child can express his opinion) |

| Democratic parenting style | Moderate (every family member has the right to vote) |

| Egalitarian parenting style | Self-control (the rights and obligations of adults and children are completely equal) |

| Permissive parenting style | Low supervision |

| Permissive parenting style | Lack of control (complete freedom of action of the child) |

| Ignoring parenting style | Complete lack of control and interest in the child's life |

The degree of control over the actions of the child is a very important indicator of the style of family education.

How much freedom a child is given in childhood depends on whether he grows up self-confident, active and enterprising, or, on the contrary, becomes an anxious and inactive person.

Classification of family education styles L.G. Sagotovskoy

This classification describes six possible parenting styles that differ in the degree of emotionality of the relationship between adults and the child, as well as the role of children in family life.

- The child is the main concern and goal of adult life;

- The child is the object of pedagogical efforts;

- Child helper, small adult;

- The child is a friend, an independent person;

- Child - "empty place";

- The child is a nuisance.

Variants of pathological styles of family education (EG Eidemiller)

The author of this classification identifies styles of family education that are abnormal and have a negative impact on the development of the child's personality. Parenting styles differ in the level of adult participation in the lives of children, the degree of control and attention of parents to the individual characteristics of the child.

Parenting styles differ in the level of adult participation in the lives of children, the degree of control and attention of parents to the individual characteristics of the child.

- Hypo-custody is insufficient care for a child. Children in such a situation are left to themselves, contacts within the family are minimal and superficial. The extreme degree of hypoprotection is neglect and pedagogical neglect.

- Dominant overprotection - excessive concern for the child in conjunction with complete control of behavior. In such families there are a huge number of prohibitions. As a result, children may grow up to be dependent and lack of initiative.

- Indulgent overprotective parenting is a parenting style that prioritizes the child's desires and successes. Parents fulfill all the whims of their baby. Often, children who grew up in such “hothouse” conditions have a hard time in adulthood.

- Emotional rejection. With this parenting style, adults do not want to participate in the lives of children, often resorting to punishment.

Such "cold" parents may consider it their duty only to provide for the child and do not care about the emotional well-being of the baby.

Such "cold" parents may consider it their duty only to provide for the child and do not care about the emotional well-being of the baby. - Excessive requirements. Sometimes parents impose too many responsibilities on the child and demand from him what he is not yet capable of. This attitude towards the crumbs as a small adult often leads to increased anxiety and depression.

- Inconsistency. The chaotic style of family education, which may arise due to the lack of a single position among parents or their fear of seeming unloving to the baby. Floating boundaries of what is permitted and inconsistency develop in the child impulsiveness, insecurity, instability of self-esteem. A kid who does not have a clear picture of the world does not get the feeling of security and predictability he needs.

Advice for parents

In this article we have told you about different styles of parenting. Although each of the authors gave the styles their own name and used different classification criteria, they all talked about the same thing. In the traditional classification, which generalizes the options proposed earlier, four main types of family education are presented: authoritarian (powerful), democratic (respectful), indulgent (overprotective), conniving (indifferent). Their features are clearly shown in the video:

In the traditional classification, which generalizes the options proposed earlier, four main types of family education are presented: authoritarian (powerful), democratic (respectful), indulgent (overprotective), conniving (indifferent). Their features are clearly shown in the video:

The authoritarian parenting style assumes that the word of the parents for the child is the law. Few children can retain their individuality at the same time, most often the baby grows up distrustful, withdrawn, dependent. During adolescence, the child may experience rebelliousness and antisocial behavior.

If you notice an authoritarian pattern of behavior behind you, try to change your attitude towards the child. It is necessary to reduce the pressure on the baby and pay attention to his own needs and desires.

Another extreme is the permissive style of family education, in which everything is allowed for the child. Often parents use this parenting style to show their love, but this strategy does not lead to positive results. The absence of parental authority and any restrictions inadequately overestimates the child's self-esteem, which can lead to communication difficulties.

Often parents use this parenting style to show their love, but this strategy does not lead to positive results. The absence of parental authority and any restrictions inadequately overestimates the child's self-esteem, which can lead to communication difficulties.

The child's development is negatively affected by both total parental control and lack of discipline. Restrictions and prohibitions are very important for the baby. They teach him to control his actions and behave within the framework of social norms.

The most harmonious style of family education is the democratic style. It is a combination of discipline and respect for the freedom of the child. Adults do not infringe on the rights of children, and they, in turn, have a number of responsibilities. Close trusting relationships are established within the family. As a result, children grow up sociable, self-confident and independent.

Conclusions

The influence of the style of family education on the formation of a child's personality is an extremely important and urgent problem.

The opinion of all family members is taken into account when solving important issues. The child is perceived as an independent person.

The opinion of all family members is taken into account when solving important issues. The child is perceived as an independent person.