How does culture influence parenting styles

Cultural Approaches to Parenting - PMC

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

- PMC3433059

Parent Sci Pract. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2013 Jan 1.

Published in final edited form as:

Parent Sci Pract. 2012 Jan 1; 12(2-3): 212–221.

Published online 2012 Jun 14. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2012.683359

PMCID: PMC3433059

NIHMSID: NIHMS385560

PMID: 22962544

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

This article first introduces some main ideas behind culture and parenting and next addresses philosophical rationales and methodological considerations central to cultural approaches to parenting, including a brief account of a cross-cultural study of parenting. It then focuses on universals, specifics, and distinctions between form (behavior) and function (meaning) in parenting as embedded in culture. The article concludes by pointing to social policy implications as well as future directions prompted by a cultural approach to parenting.

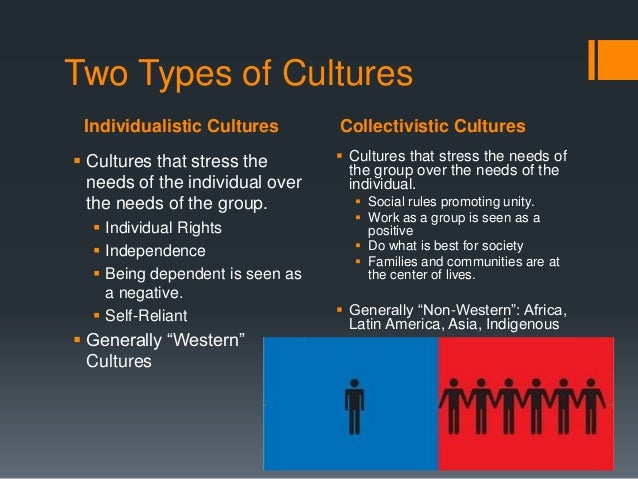

Every culture is characterized, and distinguished from other cultures, by deep-rooted and widely acknowledged ideas about how one needs to feel, think, and act as a functioning member of the culture. Cross-cultural study affirms that groups of people possess different beliefs and engage in different behaviors that may be normative in their culture but are not necessarily normative in another culture. Cultural groups thus embody particular characteristics that are deemed essential or advantageous to their members. These beliefs and behaviors tend to persist over time and constitute the valued competencies that are communicated to new members of the group. Central to a concept of culture, therefore, is the expectation that different cultural groups possess distinct beliefs and behave in unique ways with respect to their parenting. Cultural variations in parenting beliefs and behaviors are impressive, whether observed among different, say ethnic, groups in one society or across societies in different parts of the world. This article addresses the rapidly increasing research interest in cultural differences in parenting. It first takes up philosophical underpinnings, rationales, and methodological considerations central to cultural approaches to parenting, describes a cross-cultural study of parenting, and then addresses some core issues in cultural approaches to parenting, viz. universals, specifics, and the form-versus-function distinction. It concludes with an overview of social policy implications and future directions of cultural approaches to parenting.

Cultural variations in parenting beliefs and behaviors are impressive, whether observed among different, say ethnic, groups in one society or across societies in different parts of the world. This article addresses the rapidly increasing research interest in cultural differences in parenting. It first takes up philosophical underpinnings, rationales, and methodological considerations central to cultural approaches to parenting, describes a cross-cultural study of parenting, and then addresses some core issues in cultural approaches to parenting, viz. universals, specifics, and the form-versus-function distinction. It concludes with an overview of social policy implications and future directions of cultural approaches to parenting.

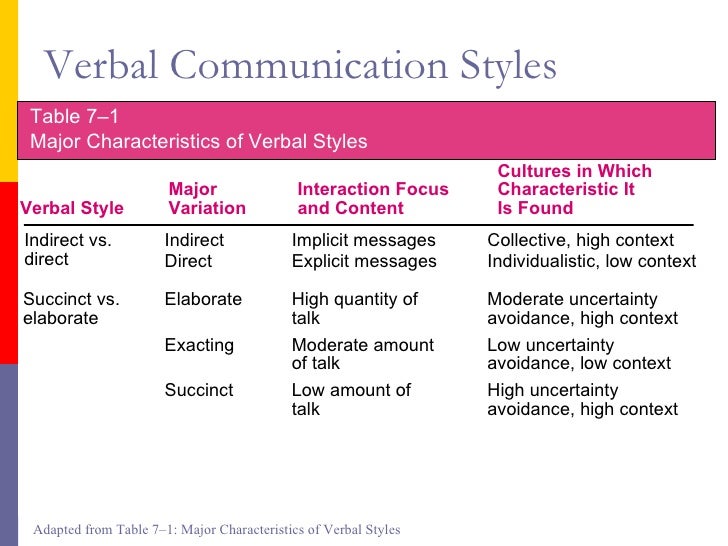

Culture is usefully conceived of as the set of distinctive patterns of beliefs and behaviors that are shared by a group of people and that serve to regulate their daily living. These beliefs and behaviors shape how parents care for their offspring. Thus, having experienced unique patterns of caregiving is a principal reason that individuals in different cultures are who they are and often differ so from one another. Culture helps to construct parents and parenting, and culture is maintained and transmitted by influencing parental cognitions that in turn are thought to shape parenting practices (Bornstein & Lansford, 2010; Harkness et al., 2007). Children’s experiences with their parents within a cultural context consequently scaffold them to become culturally competent members of their society. For example, European American and Puerto Rican mothers of toddlers believe in the differential value of individual autonomy versus connected interdependence, a contrast that in turn relates to mothers’ actual caregiving (Harwood, Schoelmerich, Schulze, & Gonzalez, 1999): Where European American mothers use suggestions (rather than commands) and other indirect means of structuring their children’s behavior, Puerto Rican mothers use more direct means of structuring, such as commands, physical positioning and restraints, and direct attempts to recruit their children’s attention.

Thus, having experienced unique patterns of caregiving is a principal reason that individuals in different cultures are who they are and often differ so from one another. Culture helps to construct parents and parenting, and culture is maintained and transmitted by influencing parental cognitions that in turn are thought to shape parenting practices (Bornstein & Lansford, 2010; Harkness et al., 2007). Children’s experiences with their parents within a cultural context consequently scaffold them to become culturally competent members of their society. For example, European American and Puerto Rican mothers of toddlers believe in the differential value of individual autonomy versus connected interdependence, a contrast that in turn relates to mothers’ actual caregiving (Harwood, Schoelmerich, Schulze, & Gonzalez, 1999): Where European American mothers use suggestions (rather than commands) and other indirect means of structuring their children’s behavior, Puerto Rican mothers use more direct means of structuring, such as commands, physical positioning and restraints, and direct attempts to recruit their children’s attention.

Parents normally organize and distribute their caregiving faithful to indigenous cultural belief systems and behavior patterns. Indeed, culturally constructed beliefs can be so powerful that parents are known to act on them, setting aside what their senses might tell them about their own children. For example, parents in most societies speak to babies and rightly see them as comprehending interactive partners long before infants produce language, whereas parents in some societies think that it is nonsensical to talk to infants before children themselves are capable of speech (Ochs, 1988).

Cultural cognitions and practices instantiate themes that communicate consistent cultural messages (Quinn & Holland, 1987). For example, in the United States personal choice is firmly rooted in principles of liberty and freedom, is closely bound up with how individuals conceive of themselves and make sense of their lives, and is a persistent and significant construct in the literature on parenting (Tamis-LeMonda & McFadden, 2010). Moreover, culture-specific patterns of childrearing can be expected to adapt to each society’s specific setting and needs. For example, young infants among the nomadic hunter-gatherer Aka are more likely to be held and fed in close proximity to their caregivers than are infants from Ngandu farming communities who are more likely to be left by themselves, even though these two traditional groups live close to one another in central Africa (Hewlett, Lamb, Shannon, Leyendecker, & Schoelmerich, 1998). Aka parents are reasoned to maintain closer proximity to infants because the group moves in search of food more frequently than do Ngandu.

Moreover, culture-specific patterns of childrearing can be expected to adapt to each society’s specific setting and needs. For example, young infants among the nomadic hunter-gatherer Aka are more likely to be held and fed in close proximity to their caregivers than are infants from Ngandu farming communities who are more likely to be left by themselves, even though these two traditional groups live close to one another in central Africa (Hewlett, Lamb, Shannon, Leyendecker, & Schoelmerich, 1998). Aka parents are reasoned to maintain closer proximity to infants because the group moves in search of food more frequently than do Ngandu.

Generational, social, and media images – culture -- of caregiving and childhood play formative roles in generating parenting cognitions and guiding parenting practices (Bornstein & Lansford, 2010). Parenting thus embeds cultural models and meanings into basic psychological processes which maintain or transform the culture (Bornstein, 2009). Reciprocally, culture expresses and perpetuates itself through parenting. Parents bring certain cultural proclivities to interactions with their children, and parents interpret even similar characteristics in children within their culture’s frame of reference; parents then encourage or discourage characteristics as appropriate or detrimental to adequate functioning within the group.

Reciprocally, culture expresses and perpetuates itself through parenting. Parents bring certain cultural proclivities to interactions with their children, and parents interpret even similar characteristics in children within their culture’s frame of reference; parents then encourage or discourage characteristics as appropriate or detrimental to adequate functioning within the group.

The move toward a culturally richer understanding of parenting has given rise to a set of important questions about parenting (Bornstein, 2001). What is normative parenting and to what extent does it vary with culture? What are the historical, economic, social, or other sources of cultural variation in parenting norms? How does culture embed into parenting cognitions and practices and manifest and maintain itself through parenting?

There is definite need and significance for a cultural approach to parenting science. Descriptively it is invaluable for revealing the full range of human parenting. The study of parenting across cultures also furnishes a check against an ethnocentric world view of parenting. Acceptance of findings from any one culture as “normative” of parenting is too narrow in scope, and ready generalizations from them to parents at large are blindingly uncritical. Comparison across cultures is also valuable because it augments an understanding of the processes through which biological variables fuse with environmental variables and experiences. Parenting needs to be considered in its socio-cultural context, and cultural study provides the variability necessary to expose process.

Acceptance of findings from any one culture as “normative” of parenting is too narrow in scope, and ready generalizations from them to parents at large are blindingly uncritical. Comparison across cultures is also valuable because it augments an understanding of the processes through which biological variables fuse with environmental variables and experiences. Parenting needs to be considered in its socio-cultural context, and cultural study provides the variability necessary to expose process.

Cultural Methods in Parenting Science

Some culture research in parenting compares group means on variables of interest, like parenting cognitions and practices or their child outcomes, using analyses of variance statistics. Other research looks at how culture moderates patterns of associations between variables across cultural groups. Both approaches require indicators that are clearly defined and measured in consistent ways. Cultural science, in addition to requirements of any good science, also brings with it unique issues and requirements (translation, sampling, and measurement equivalence, for example), and risks associated with this research are enhanced when it is conducted without full awareness and sensitivity to these specific concerns. For example, studies that compare cultural groups often require the collection of data in different languages, and the instruments used in such comparisons must be rendered equally valid across cultural groups (Peña, 2007). Furthermore, with any test of between-group differences, there is a chance that measures are not equivalent in the groups. Equivalences at many levels are important, and steps need to be taken to promote not only cross-linguistic appropriateness but also cross-cultural validity of instruments to achieve at least “adapted equivalence” (van de Vijver & Leung, 1997). Indeed, failure to do so creates problems in interpretation of findings that are as serious as lack of reliability and validity (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). If test measurement invariance is not tested and ensured, additional empirical and/or conceptual justification that the measures used have the same meaning in different cultural groups is required.

For example, studies that compare cultural groups often require the collection of data in different languages, and the instruments used in such comparisons must be rendered equally valid across cultural groups (Peña, 2007). Furthermore, with any test of between-group differences, there is a chance that measures are not equivalent in the groups. Equivalences at many levels are important, and steps need to be taken to promote not only cross-linguistic appropriateness but also cross-cultural validity of instruments to achieve at least “adapted equivalence” (van de Vijver & Leung, 1997). Indeed, failure to do so creates problems in interpretation of findings that are as serious as lack of reliability and validity (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). If test measurement invariance is not tested and ensured, additional empirical and/or conceptual justification that the measures used have the same meaning in different cultural groups is required.

Cultural comparisons of parenting usually involve quasi-experimental designs, in which samples are not randomly selected either from the world population or from national populations or (obviously) assigned to cultures. Interpreting findings is much more challenging in such designs than in experiments that are based on random assignment of participants. A major challenge that confronts cultural comparisons concerns how to isolate source(s) of potential effects and identify the presumed active cultural ingredient(s) that produced differences. Samples in different cultures can differ on many personological or sociodemographic characteristics that may confound parenting differences. For example, parents in different cultural groups may vary in modal patterns of personality, acculturation level, education, or socioeconomic status (Bornstein et al., 2007; Bornstein et al., 2012). Various procedures are available to untangle rival explanations for cultural comparisons, such as the inclusion of covariates in the research design to confirm or disconfirm specific alternative interpretations. By ruling out complementary accounts, it is possible to draw conclusions that are more firmly situated in culture. For example, culture influences teaching and expectations of children in mothers of Australian versus Lebanese descent all living in Australia apart from child gender, parity, and socioeconomic class (Goodnow, Cashmore, Cotton, & Knight, 1984).

Interpreting findings is much more challenging in such designs than in experiments that are based on random assignment of participants. A major challenge that confronts cultural comparisons concerns how to isolate source(s) of potential effects and identify the presumed active cultural ingredient(s) that produced differences. Samples in different cultures can differ on many personological or sociodemographic characteristics that may confound parenting differences. For example, parents in different cultural groups may vary in modal patterns of personality, acculturation level, education, or socioeconomic status (Bornstein et al., 2007; Bornstein et al., 2012). Various procedures are available to untangle rival explanations for cultural comparisons, such as the inclusion of covariates in the research design to confirm or disconfirm specific alternative interpretations. By ruling out complementary accounts, it is possible to draw conclusions that are more firmly situated in culture. For example, culture influences teaching and expectations of children in mothers of Australian versus Lebanese descent all living in Australia apart from child gender, parity, and socioeconomic class (Goodnow, Cashmore, Cotton, & Knight, 1984).

Other methodological questions threaten the validity of cultural comparisons (Matsumoto & van de Vijver, 2011). For example, it matters who is doing the study, their culture, their assumptions in asking certain questions, and so forth. Whether collaborators and scientists are “on the ground” in the culture and undertake adequate preliminary study to generate meaningful questions are also pertinent.

Similarity and Difference in Parenting across Cultures

The “story” of the cultural investigation of parenting is largely one of similarities, differences, and their meaning. In an illustrative study, we analyzed and compared natural mother-infant interactions in Argentina, Belgium, Israel, Italy, and the United States (Bornstein et al., 2012). Differences exist among the locales we recruited from in terms of history, beliefs, languages, and childrearing values. However, the samples were more alike than not in terms of modernity, urbanity, economics, politics, living standards, even ecology and climate. Thus, they created the possibility of identifying culture-unique and -general conclusions about childrearing. Mothers were primiparous, at least 18 years of age, and from intact families; infants were firstborn, term, healthy, and 5 months old. Our aims were to observe mothers and their infants under ecologically valid, natural, and unobtrusive conditions, and so we studied their usual routines in the familiar confines of their own homes. We videorecorded mother-baby dyads and then used mutually exclusive and exhaustive coding systems to comprehensively characterize frequency and duration of six maternal caregiving behavioral domains (nurture, physical, social, didactic, material, and language) and five corresponding infant developmental domains (physical, social, exploration, vocalization, and distress communication).

Thus, they created the possibility of identifying culture-unique and -general conclusions about childrearing. Mothers were primiparous, at least 18 years of age, and from intact families; infants were firstborn, term, healthy, and 5 months old. Our aims were to observe mothers and their infants under ecologically valid, natural, and unobtrusive conditions, and so we studied their usual routines in the familiar confines of their own homes. We videorecorded mother-baby dyads and then used mutually exclusive and exhaustive coding systems to comprehensively characterize frequency and duration of six maternal caregiving behavioral domains (nurture, physical, social, didactic, material, and language) and five corresponding infant developmental domains (physical, social, exploration, vocalization, and distress communication).

One question we asked concerned cultural similarities and differences in base rates of parenting in the six caregiving domains. We standardized maternal behavior frequency in terms of rate of occurrence per hour, pooled, normalized, and disaggregated the data by country, finally analyzing country means for parallel comparisons for different domains. Mothers differed in every domain assessed. Moreover, mothers in no one country surpassed mothers in all others in their base rates of parenting across domains. The fact that maternal behaviors vary significantly across these modern, industrialized, and comparable places underscores the role of cultural influence on everyday human experiences, even from the start of life. Of course, even greater variation is often revealed in starker contrasts. For example, mothers in rural Thailand do not know that their newborns can see, and so during the day swaddle infants in fabric hammocks that allow babies only a slit view of ceiling or sky (Kotchabhakdi, Winichagoon, Smitasiri, Dhanamitta, & Valyasevi, 1987). Awareness of alternative modes of development also enhances understanding of the nature of variation across cultures; cross-cultural comparisons show how. For example, U.S. mothers are often thought of as being highly verbal, but U.S. mothers actually fell at the bottom of our five-culture comparison.

Mothers differed in every domain assessed. Moreover, mothers in no one country surpassed mothers in all others in their base rates of parenting across domains. The fact that maternal behaviors vary significantly across these modern, industrialized, and comparable places underscores the role of cultural influence on everyday human experiences, even from the start of life. Of course, even greater variation is often revealed in starker contrasts. For example, mothers in rural Thailand do not know that their newborns can see, and so during the day swaddle infants in fabric hammocks that allow babies only a slit view of ceiling or sky (Kotchabhakdi, Winichagoon, Smitasiri, Dhanamitta, & Valyasevi, 1987). Awareness of alternative modes of development also enhances understanding of the nature of variation across cultures; cross-cultural comparisons show how. For example, U.S. mothers are often thought of as being highly verbal, but U.S. mothers actually fell at the bottom of our five-culture comparison.

A second question we asked concerned relations between parent-provided experiences and behavioral development in young infants (Bornstein et al., 2012). Across cultures, mothers and infants showed a noteworthy degree of attunement and specificity. Mothers who encouraged their infants’ physical development more had more physically developed infants as opposed to other outcomes; mothers who engaged infants more socially had infants who paid more attention to them; mothers who encouraged their infants more didactically had infants who explored more properties, objects, and events in the environment, as did babies whose mothers outfitted their environments in richer ways. That is, mothers and infants are not only in tune with one another, but their correspondences tend to be domain specific. Thus specific correspondences in mother-infant interaction patterns were widespread and similar in different cultural groups.

This kind of study continues the story of cultural approaches to parenting in terms of their traditional dual foci on similarities and differences. Mothers in different cultures differ in their mean levels of different domains of parenting infants, but mothers and infants in different cultures are similar in terms of mutual attunement of caregiving on the part of mothers and development in corresponding domains in infants. A shift in focus to the meaning of those similarities and differences advances the culture and parenting narrative.

Mothers in different cultures differ in their mean levels of different domains of parenting infants, but mothers and infants in different cultures are similar in terms of mutual attunement of caregiving on the part of mothers and development in corresponding domains in infants. A shift in focus to the meaning of those similarities and differences advances the culture and parenting narrative.

Culture-Common and Culture-Specific Parenting

The cultural approach to parenting has as one main goal to evaluate and compare culture-common and culture-specific modes of parenting. Evolutionary thinking appeals to the species-common genome, and the biological heritage of some psychological processes presupposes their universality (Norenzayan & Heine, 2005) as do shared historical and economic forces (Harris, 2001). At the same time, cultural psychology explores variation in core psychological processes by investigating the competing influences of divergent physical and social environments (Bornstein, 2010; van de Vijver & Leung, 1997). Psychological constructs, structures, functions, and processes like parenting can be universal and simultaneously reflect cultural moderation of their quantitative level or qualitative expression. Language illustrates this essential duality. An evolutionary model posits a language instinct from the perspective of an inborn and universal acquisition device, but diversity of environmental input plays a strong role in the acquisition of any specific language (Pinker, 2007). Some demands on parents are universal. For example, parents in all societies must nurture and protect their young (Bornstein, 2006). Other demands vary greatly across cultural groups. For example, parents in some societies play with babies and see them as interactive partners, whereas parents in other societies think that it is senseless for parents to play with infants (Bornstein, 2007).

Psychological constructs, structures, functions, and processes like parenting can be universal and simultaneously reflect cultural moderation of their quantitative level or qualitative expression. Language illustrates this essential duality. An evolutionary model posits a language instinct from the perspective of an inborn and universal acquisition device, but diversity of environmental input plays a strong role in the acquisition of any specific language (Pinker, 2007). Some demands on parents are universal. For example, parents in all societies must nurture and protect their young (Bornstein, 2006). Other demands vary greatly across cultural groups. For example, parents in some societies play with babies and see them as interactive partners, whereas parents in other societies think that it is senseless for parents to play with infants (Bornstein, 2007).

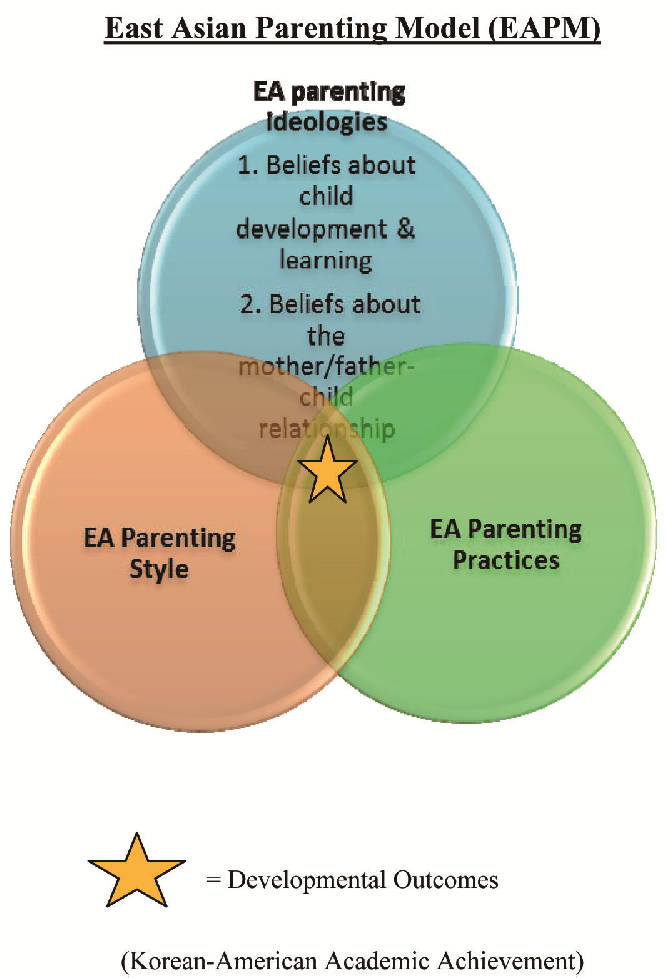

Culture-specific influences on parenting begin long before children are born, and they shape fundamental decisions about which behaviors parents should promote in their children and how parents should interact with their children (Bornstein, 1991; Whiting, 1963). Thus, caregiving varies among cultures in terms of opinions about the full range of caregiving and child development, including the significance of specific competencies for children’s successful adjustment, the ages expected for children to reach developmental milestones, when and how to care for children, and the like. For example, the United States and Japan are both child-centered modern societies with equivalently high standards of living and so forth, but U.S. American and Japanese parents value different childrearing goals which they express in different ways (Bornstein, 1989; Bornstein et al., 2012; Morelli & Rothbaum, 2007). American mothers try to promote autonomy, assertiveness, verbal competence, and self-actualization in their children, whereas Japanese mothers try to promote emotional maturity, self-control, social courtesy, and interdependence in theirs.

Thus, caregiving varies among cultures in terms of opinions about the full range of caregiving and child development, including the significance of specific competencies for children’s successful adjustment, the ages expected for children to reach developmental milestones, when and how to care for children, and the like. For example, the United States and Japan are both child-centered modern societies with equivalently high standards of living and so forth, but U.S. American and Japanese parents value different childrearing goals which they express in different ways (Bornstein, 1989; Bornstein et al., 2012; Morelli & Rothbaum, 2007). American mothers try to promote autonomy, assertiveness, verbal competence, and self-actualization in their children, whereas Japanese mothers try to promote emotional maturity, self-control, social courtesy, and interdependence in theirs.

Many parenting cognitions and practices are likely to be similar across cultures; indeed, similarities may reflect universals (in the sense of being common) even if they vary in form and the degree to which they are shaped by experience and influenced by culture. Such patterns of parenting might reflect inherent attributes of caregiving, historical convergences in parenting, or they could be a by-product of information dissemination via forces of globalization or mass media or migration that present parents today with increasingly similar socialization models, issues, and challenges. In the end, all peoples must help children meet similar developmental tasks, and all peoples (presumably) wish physical health, social adjustment, educational achievement, and economic security for their children, and so they parent in some manifestly similar ways. Furthermore, the mechanisms through which parents likely affect children are universal. For example, social learning theorists have identified the pervasive roles that conditioning and modeling play as children acquire associations that subsequently form the basis for their culturally constructed selves. By watching or listening to others who are already embedded in the culture, children come to think and act like them.

Such patterns of parenting might reflect inherent attributes of caregiving, historical convergences in parenting, or they could be a by-product of information dissemination via forces of globalization or mass media or migration that present parents today with increasingly similar socialization models, issues, and challenges. In the end, all peoples must help children meet similar developmental tasks, and all peoples (presumably) wish physical health, social adjustment, educational achievement, and economic security for their children, and so they parent in some manifestly similar ways. Furthermore, the mechanisms through which parents likely affect children are universal. For example, social learning theorists have identified the pervasive roles that conditioning and modeling play as children acquire associations that subsequently form the basis for their culturally constructed selves. By watching or listening to others who are already embedded in the culture, children come to think and act like them. Attachment theorists propose that children everywhere develop internal working models of social relationships through interactions with their primary caregivers and that these models shape children’s future social relationships with others throughout the balance of the life course (Sroufe & Fleeson, 1986). With so much emphasis on identification of differences among peoples, it is easy to forget that nearly all parents regardless of culture seek to lead happy, healthy, fulfilled parenthoods and to rear happy, healthy, fulfilled children.

Attachment theorists propose that children everywhere develop internal working models of social relationships through interactions with their primary caregivers and that these models shape children’s future social relationships with others throughout the balance of the life course (Sroufe & Fleeson, 1986). With so much emphasis on identification of differences among peoples, it is easy to forget that nearly all parents regardless of culture seek to lead happy, healthy, fulfilled parenthoods and to rear happy, healthy, fulfilled children.

Form and Function in Cultural Approaches to Parenting

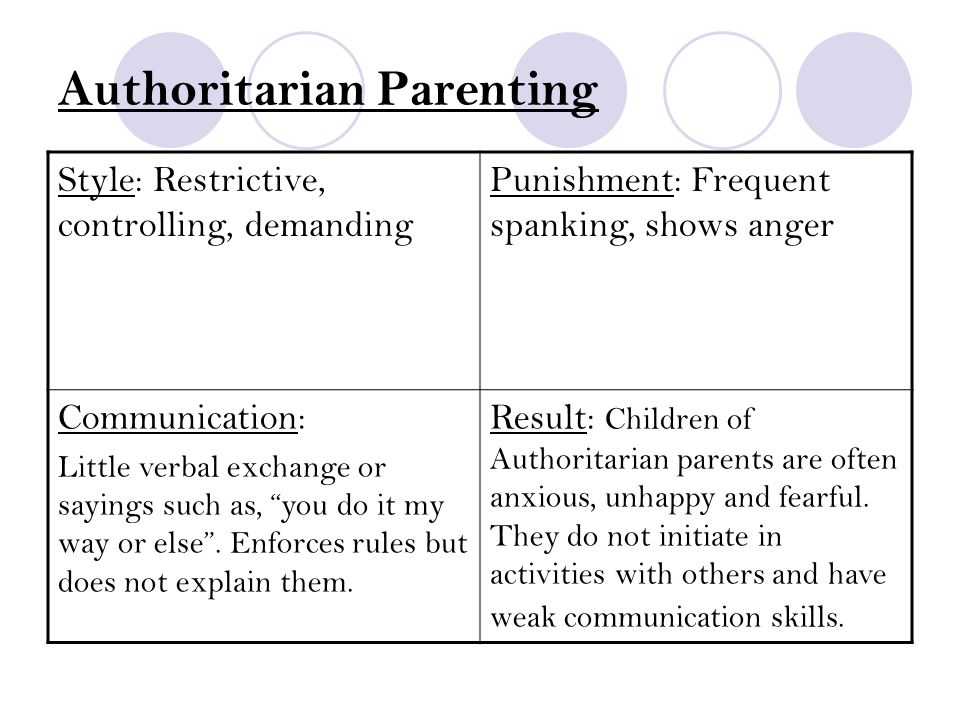

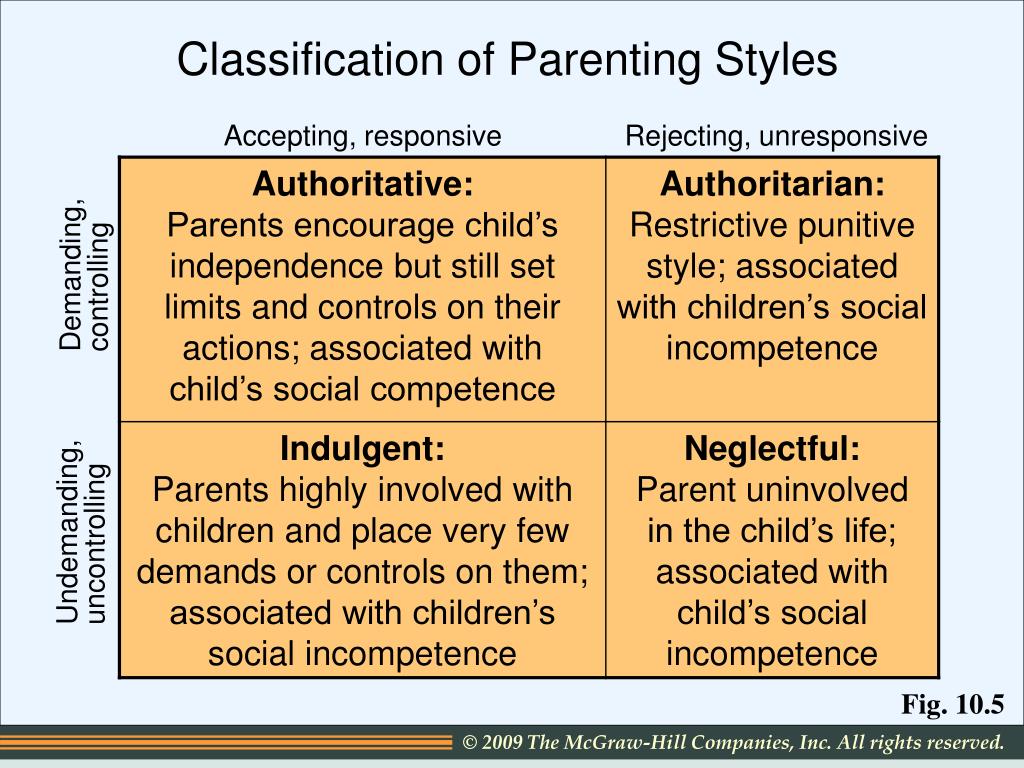

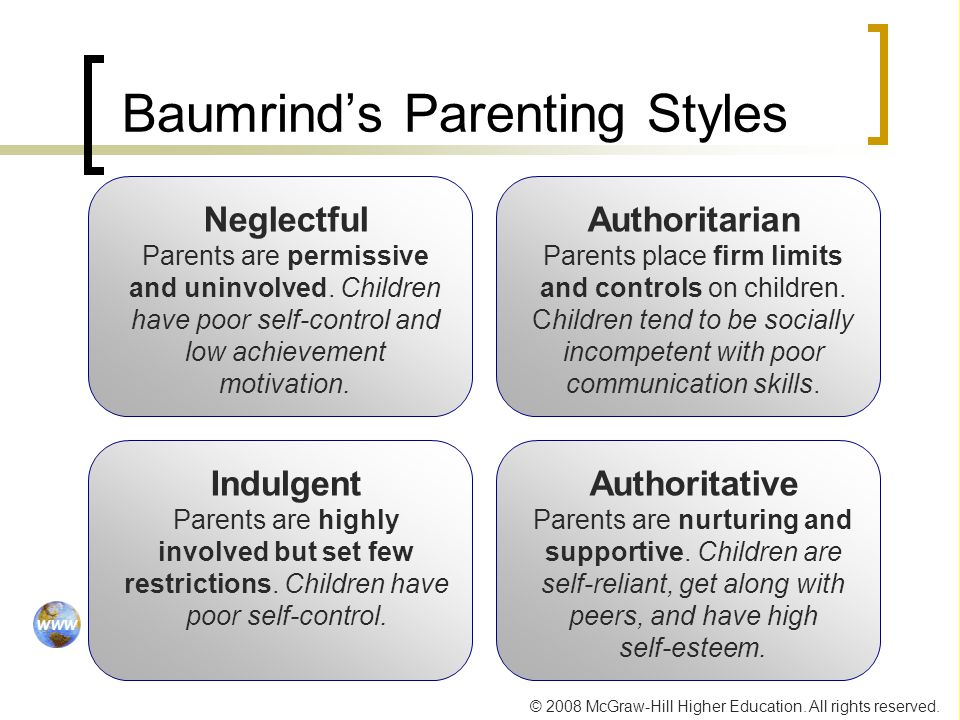

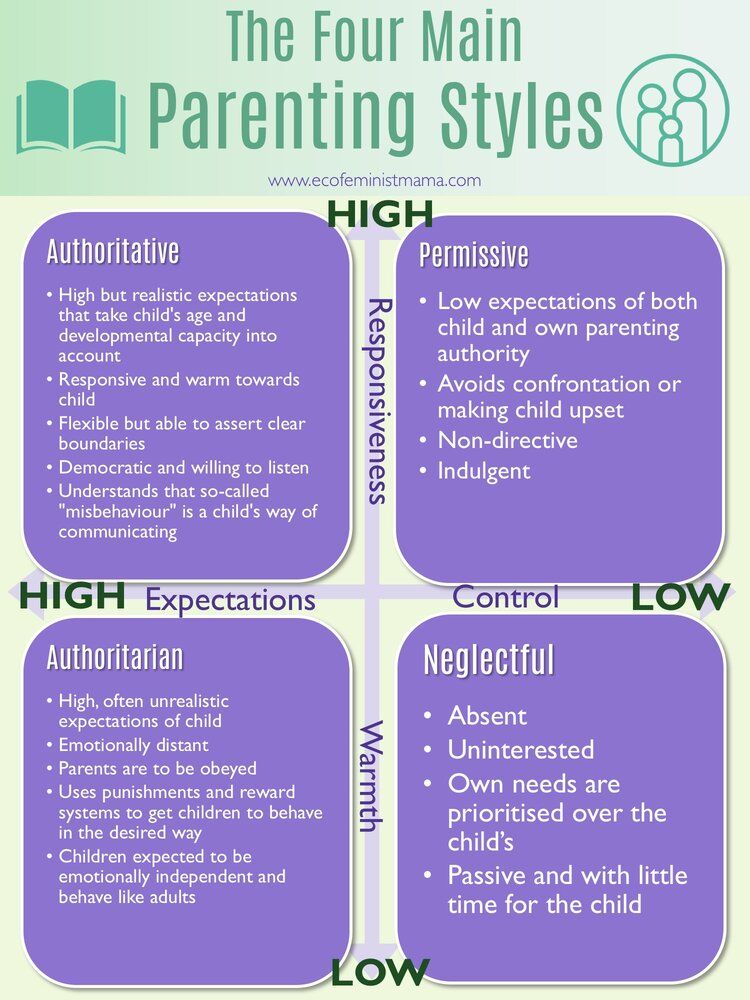

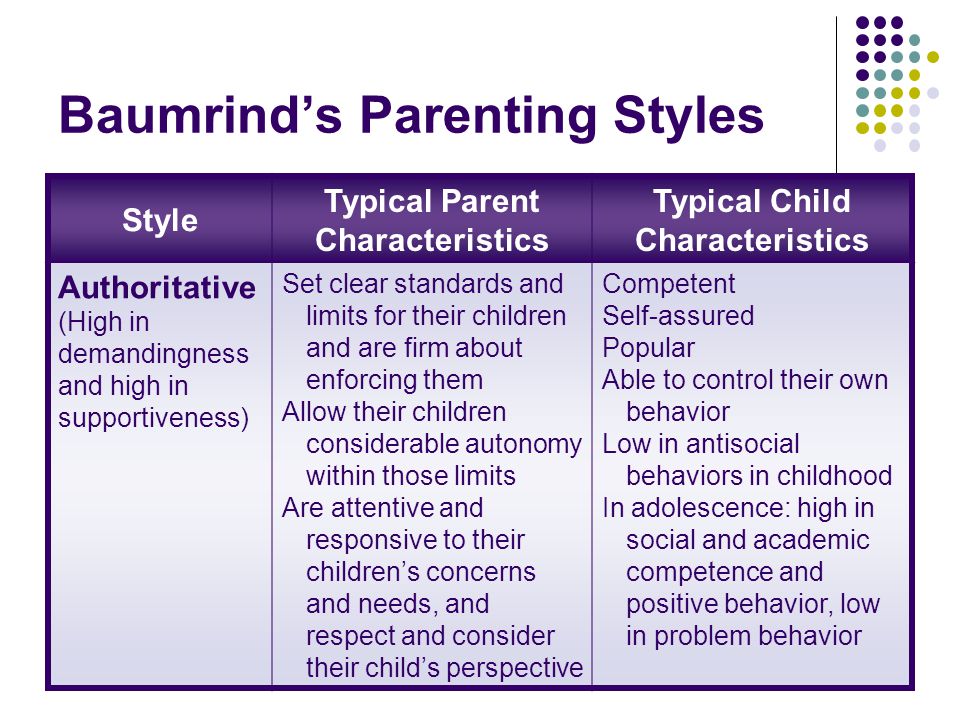

These general considerations of universals and specifics lead to a logic model that contrasts form with function in parenting. By form, I mean a parenting cognition or practice as instantiated; by function, I mean the purpose or construal or meaning attached to the form. A proper understanding of the function of parenting cognitions and practices requires situating them in their cultural context (Bornstein, 1995). When a particular parenting cognition or practice serves the same function and connotes the same meaning in different cultures, it likely constitutes a universal. For example, caregivers in (almost) all cultures routinely adjust their speech to very young children making it simpler and more redundant, presumably to support early language acquisition; child-directed speech constitutes a universal that adults find difficult to suppress (Papoušek & Bornstein, 1992). The same parenting cognition or practice can also assume different functions in different cultural contexts. Particular parental practices, such as harsh initiation rites, deemed less harmful to children in some cultures may be judged abusive in others. Conversely, different parenting cognitions and practices may serve the same function in different cultural contexts. For example, an authoritative parenting style (high warmth, high control) leads to positive outcomes in European American school children, whereas an authoritarian parenting style (low warmth, high control) leads to positive outcomes in African American and Hong Kong Chinese school children (Leung, Lau, & Lam, 1998).

When a particular parenting cognition or practice serves the same function and connotes the same meaning in different cultures, it likely constitutes a universal. For example, caregivers in (almost) all cultures routinely adjust their speech to very young children making it simpler and more redundant, presumably to support early language acquisition; child-directed speech constitutes a universal that adults find difficult to suppress (Papoušek & Bornstein, 1992). The same parenting cognition or practice can also assume different functions in different cultural contexts. Particular parental practices, such as harsh initiation rites, deemed less harmful to children in some cultures may be judged abusive in others. Conversely, different parenting cognitions and practices may serve the same function in different cultural contexts. For example, an authoritative parenting style (high warmth, high control) leads to positive outcomes in European American school children, whereas an authoritarian parenting style (low warmth, high control) leads to positive outcomes in African American and Hong Kong Chinese school children (Leung, Lau, & Lam, 1998). When different parenting cognitions or practices serve different functions in different settings, it is evidence for cultural specificity. Many different parenting practices appear to be adaptive but differently for different cultural groups (Ogbu, 1993). Thus, cultural study informs not only about quantitative aspects but also about qualitative meaning of parents’ beliefs and behaviors.

When different parenting cognitions or practices serve different functions in different settings, it is evidence for cultural specificity. Many different parenting practices appear to be adaptive but differently for different cultural groups (Ogbu, 1993). Thus, cultural study informs not only about quantitative aspects but also about qualitative meaning of parents’ beliefs and behaviors.

It is imperative to learn more about parenting and culture so that scientists, educators, and practitioners can effectively enhance parent and child development and strengthen families in diverse social groups. Insofar as some systematic universal relations obtain between how people parent and how children develop, the possibility exists for identifying some “best practices” in how to promote positive parenting and child development. Differences attached to the cultural meanings of particular behaviors can cause problems, however. For example, immigrant children may have parents who expect them to behave in one way that is encouraged at home (e. g., averting eye contact to show deference and respect) but then find themselves in a context where adults of the mainstream culture attach a different (often negative) meaning to the same behavior (e.g., appearing disinterested and unengaged with a teacher at school).

g., averting eye contact to show deference and respect) but then find themselves in a context where adults of the mainstream culture attach a different (often negative) meaning to the same behavior (e.g., appearing disinterested and unengaged with a teacher at school).

Other possible future directions for a cultural parenting science would constitute a long agendum. Some will be procedural. Many studies rely on self-reports, and many survey parenting at only one point in time. Observations of actual practices constitute a vital complementary data base (Bornstein, Cote, & Venuti, 2001), and a developmental perspective offers insights into temporal processes of enculturation, parents tracking differential ontogenetic trajectories, and highlights intergenerational similarities and differences in parents and children from different cultures (Bornstein et al., 2010). Parenting modifies social and cognitive aspects of the developing individual and so the design of the brain. For example, assistance constitutes an important feature of family relationships for adolescents but has distinctive values in Latino and European heritage cultures. Youth in both ethnic groups show similar behavioral levels of helping but, via fMRI, different patterns of neural activity within the mesolimbic reward system: Latinos show more activity when contributing to family, and European Americans show more activity when gaining cash for themselves (Telzer, Masten, Berkman, Lieberman, & Fuligni, 2010). A future behavioral neuroscience of parenting will profitably include cultural variation (Barrett & Fleming, 2011; Bornstein, 2012).

Youth in both ethnic groups show similar behavioral levels of helping but, via fMRI, different patterns of neural activity within the mesolimbic reward system: Latinos show more activity when contributing to family, and European Americans show more activity when gaining cash for themselves (Telzer, Masten, Berkman, Lieberman, & Fuligni, 2010). A future behavioral neuroscience of parenting will profitably include cultural variation (Barrett & Fleming, 2011; Bornstein, 2012).

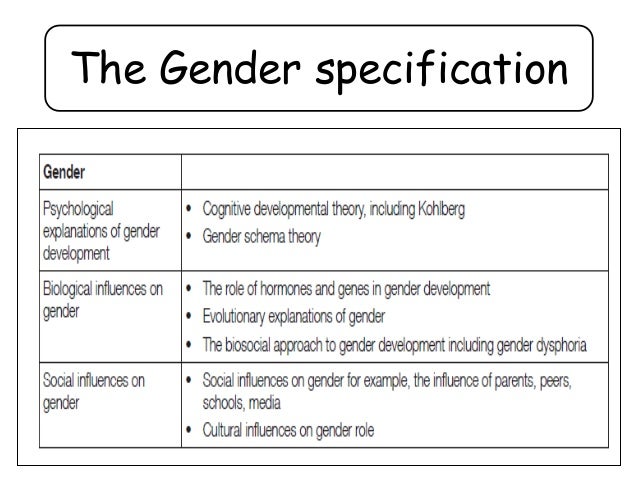

Parenting is thought to differ in mothers and fathers (and for girls and boys), but most parenting research still focuses on mothers. In many cultures, children spend large amounts of time with caregivers other than parents, and all contribute to the caregiving environment of the child. How caregiving is distributed amongst different stakeholders across cultures is not well understood, and future cultural research in parenting will benefit from an enlarged family systems perspective (Bornstein & Sawyer, 2006).

Thinking about parent-child relationships often highlights parents as agents of socialization; however, caregiving is a two-way street. Parent and child activities are characterized by intricate patterns of sensitive mutual understandings and unfolding synchronous transactions (Bornstein, 2006, 2009). Moreover, children’s appraisals of their parents affect parenting and child adjustment. Future research needs to attend to child effects, cultural normativeness, and construals of parenting as well as how culture moderates each. Parenting styles that are congruent with cultural norms appear to be effective in transmitting values from parents to children, perhaps because parenting practices that approach the cultural norm result in a childrearing environment that is more positive, consistent, and predictable and in one that facilitates children’s accurate perceptions of parents; children of parents who behave in culturally normative ways are also likely to encounter similar values in settings outside the family (e. g., in religious institutions, in the community) that reinforce their parenting experiences.

g., in religious institutions, in the community) that reinforce their parenting experiences.

Research on dynamic relations between culture and parenting is increasingly focused on which aspects of culture moderate parenting cognitions and practices and how they do so, as well as on when and why links between parenting cognitions and practices and children’s development are culturally general versus culturally specific. These new directions will move the field toward a deeper understanding, not just of which similarities obtain and which differences can be identified, but also of why, in whom, and under which conditions.

The cultural study of parenting is beneficially understood in a framework of necessary versus desirable demands. A necessary demand is that parents and children communicate with one another. Normal interaction and children’s healthy mental and socioemotional development depend on it. Not unexpectedly, communication appears to be a universal aspect of parenting and child development. A desirable demand is that parents and children communicate in certain ways adapted and faithful to their cultural context. Cultural studies tell us about parents’ and children’s mutual adjustments in terms of universally necessary and contextually desirable demands. Assumptions about the specificity and generality of parenting, and relations between parents and children, are advantageously tested through cultural research because neither parenting nor children’s development occurs in a vacuum: Both emerge and grow in a medium of culture. Variations in what is normative in different cultures help us to question our assumptions about what is universal and informs our understanding of how parent-child relationships unfold in ways both culturally universal and specific. That admirable goal notwithstanding, methodological challenges unique to this line of research loom large.

A desirable demand is that parents and children communicate in certain ways adapted and faithful to their cultural context. Cultural studies tell us about parents’ and children’s mutual adjustments in terms of universally necessary and contextually desirable demands. Assumptions about the specificity and generality of parenting, and relations between parents and children, are advantageously tested through cultural research because neither parenting nor children’s development occurs in a vacuum: Both emerge and grow in a medium of culture. Variations in what is normative in different cultures help us to question our assumptions about what is universal and informs our understanding of how parent-child relationships unfold in ways both culturally universal and specific. That admirable goal notwithstanding, methodological challenges unique to this line of research loom large.

It has been said that only two kinds of information are transmitted across generations: genes and culture. Parents are the final common pathway of both. We can ask, however, Which is the more meaningful and enduring? The biological view is that we are “gene machines,” created to pass on our genes. A child, even a grandchild, may resemble a parent in facial features or in a talent for music. However, as each generation passes the contribution of any parent’s genes is halved and it is pooled with those of many other parents. It does not take long to reach negligible proportions. Genes may be immortal, but the unique collection of genes which is any one parent crumbles away (Dawkins, 1976). Rather, what parents do, and how they prepare the next generation in their cultures, can live on, intact, long after their genes dissolve in the common pool.

We can ask, however, Which is the more meaningful and enduring? The biological view is that we are “gene machines,” created to pass on our genes. A child, even a grandchild, may resemble a parent in facial features or in a talent for music. However, as each generation passes the contribution of any parent’s genes is halved and it is pooled with those of many other parents. It does not take long to reach negligible proportions. Genes may be immortal, but the unique collection of genes which is any one parent crumbles away (Dawkins, 1976). Rather, what parents do, and how they prepare the next generation in their cultures, can live on, intact, long after their genes dissolve in the common pool.

Research supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NICHD. I thank P. Horn and C. Padilla.

- Barrett J, Fleming AS. All mothers are not created equal: Neural and psychobiological perspectives on mothering and the importance of individual differences. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry.

2011;52:368–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2011;52:368–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Bornstein MH. Cross-cultural developmental comparisons: The case of Japanese--American infant and mother activities and interactions. What we know, what we need to know, and why we need to know. Developmental Review. 1989;9:171–204. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, editor. Cultural approaches to parenting. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Form and function: Implications for studies of culture and human development. Culture and Psychology. 1995;1:123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Some questions for a science of “culture and parenting” (... but certainly not all) International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development Newsletter. 2001;1:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Parenting science and practice. In: Damon W, Renninger KA, Sigel IE, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4. Child psychology in practice. 6. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 893–949. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH.

On the significance of social relationships in the development of children’s earliest symbolic play: An ecological perspective. In: Gönçü A, Gaskins S, editors. Play and development. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2007. pp. 101–129. [Google Scholar]

On the significance of social relationships in the development of children’s earliest symbolic play: An ecological perspective. In: Gönçü A, Gaskins S, editors. Play and development. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2007. pp. 101–129. [Google Scholar] - Bornstein MH. Toward a model of culture↔parent↔child transactions. In: Sameroff A, editor. The transactional model of development. Washington, DC: APA; 2009. pp. 139–161. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, editor. The handbook of cultural developmental science. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Mother-infant attunement: A multilevel approach via body, brain, and behavior. In: Legerstee M, Haley D, Bornstein MH, editors. The developing infant mind: Integrating biology and experience. New York: Guilford; 2012. pp. xx–xx. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Cote LR, Haynes OM, Suwalsky JTD, Bakeman R. Modalities of infant-mother interaction in Japanese, Japanese American Immigrant, and European American dyads.

Child Development 2012 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Child Development 2012 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Bornstein MH, Cote LR, Venuti P. Parenting beliefs and behaviors in northern and southern groups of Italian mothers of young infants. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:663–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Lansford JE. Parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. The handbook of cross-cultural developmental science. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2010. pp. 259–277. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Park Y, Haynes OM, Suwalsky JTD, Azuma H, Bali S, Berti E, De Houwer A, de Zingman Galperin C, Kabiru M, Kwak K, Maital M, de Moura de Siedel ML, Nsamenang AB, Pêcheux M-G, Ruel J, Toda S, Venuti P, Vyt A. Unpublished ms. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2012. Infancy and Parenting in 11 Cultures: Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Cameroon, France, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kenya, South Korea, and the United States. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Sawyer J.

Family systems. In: McCartney K, Phillips D, editors. Blackwell handbook of early childhood development. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2006. pp. 381–98. [Google Scholar]

Family systems. In: McCartney K, Phillips D, editors. Blackwell handbook of early childhood development. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2006. pp. 381–98. [Google Scholar] - Bornstein MH, Suwalsky JTD, Putnick DL, Gini M, Venuti P, de Falco S, Zingman de Galperín C. Developmental continuity and stability of emotional availability in the family: Two ages and two genders in child-mother dyads from two regions in three countries. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2010;34:385–397. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins R. The selfish gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Goodnow JJ, Cashmore JA, Cotton S, Knight R. Mothers’ developmental timetables in two cultural groups. International Journal of Psychology. 1984;19:193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Harkness S, Super CM, Moscardino U, Rha J, Blom M, Huitrón B, …Palacios J. Cultural models and developmental agendas: Implications for arousal and self-regulation in early infancy.

Journal of Developmental Processes. 2007;2:5–39. [Google Scholar]

Journal of Developmental Processes. 2007;2:5–39. [Google Scholar] - Harris M. The rise of anthropological theory: A history of theories of culture. New York: Altamira Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood RL, Schoelmerich A, Schulze PA, Gonzalez Z. Cultural differences in maternal beliefs and behaviors. Child Development. 1999;70:1005–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewlett BS, Lamb ME, Shannon D, Leyendecker B, Scholmerich A. Culture and early infancy among central African foragers and farmers. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:653–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchabhakdi NJ, Winichagoon P, Smitasiri S, Dhanamitta S, Valyasevi A. The integration of psychosocial components in nutrition education in northeastern Thai villages. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health. 1987;1:16–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung K, Lau S, Lam W. Parenting styles and academic achievement: A cross-cultural study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1998;44:157–172. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto D, van de Vijver FJR, editors.

Cross-cultural research methods in psychology. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; [Google Scholar]

Cross-cultural research methods in psychology. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; [Google Scholar] - Morelli GA, Rothbaum F. Situating the child in context: Attachment relationships and self-regulation in different cultures. In: Kitayama S, Cohen D, editors. Handbook of cultural psychology. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 500–527. [Google Scholar]

- Norenzayan A, Heine SJ. Psychological universals across cultures: What are they and how do we know? Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:763–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochs E. Culture and language development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu JU. Differences in cultural frame of reference. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1993;16:483–506. [Google Scholar]

- Papoušek H, Bornstein MH. Didactic interactions: Intuitive parental support of vocal and verbal development in human infants. In: Papoušek H, Jürgens U, Papoušek M, editors. Nonverbal vocal communication.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1992. pp. 209–229. [Google Scholar]

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1992. pp. 209–229. [Google Scholar] - Peña ED. Lost in translation: Methodological considerations in cross-cultural research. Child Development. 2007;78:1255–1264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinker S. The stuff of thought. New York: Viking; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn N, Holland D. Culture and cognition. In: Holland D, Quinn N, editors. Cultural models in language and thought. New York: Cambridge University; 1987. pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Fleeson J. Attachment and the construction of relationships. In: Hartup W, Rubin Z, editors. Relationships and development. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1986. pp. 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-Lemonda CS, McFadden KE. The United States of America. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of cultural developmental sciences. New York: Psychology Press; 2010. pp. 299–322. [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, Masten CL, Berkman ET, Lieberman MD, Fuligni AJ. Gaining while giving: An fMRI study of the rewards of family assistance among White and Latino youth.

Social Neuroscience. 2010;5:508–518. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Social Neuroscience. 2010;5:508–518. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Vandenberg RJ, Lance CH. A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and ecommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods. 2000;3:4–69. [Google Scholar]

- van de Vijver F, Leung K. Methods and data analysis for cross-cultural research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting BB, editor. Six cultures: Studies of child rearing. New York, NY: Wiley; 1963. [Google Scholar]

Role of Culture in the Influencing of Parenting Styles

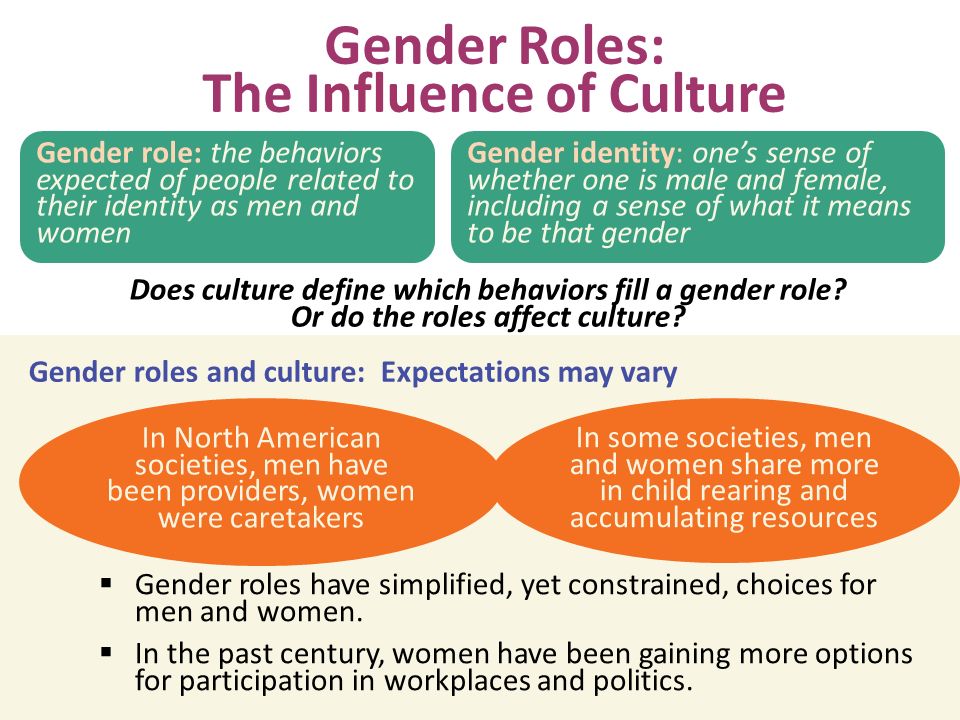

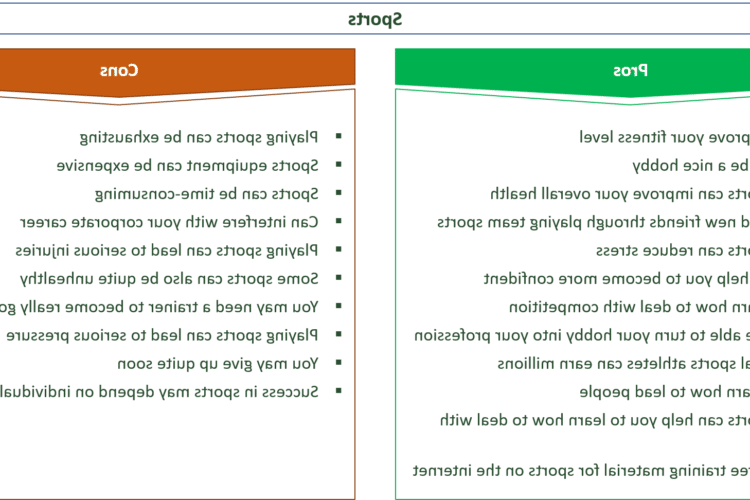

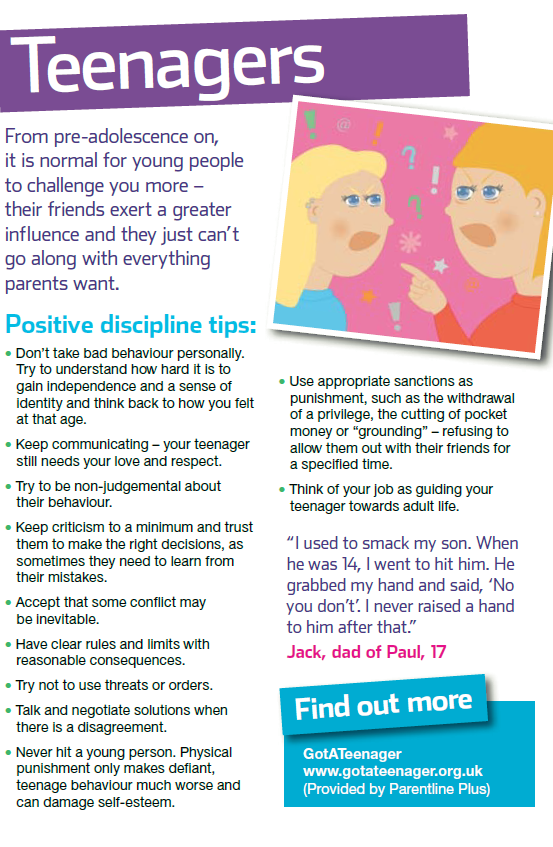

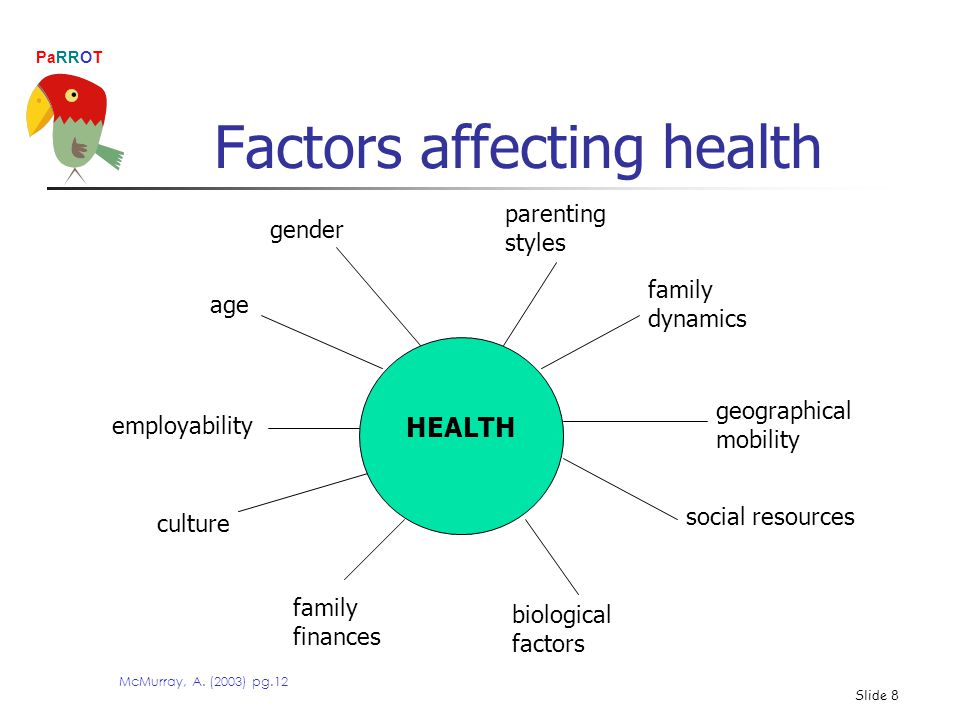

Parents from around the world have universal feelings of love, affection and hope for their children, but cultural values and expectations can color how these emotions are communicated. Making broad-sweeping generalizations about a particular culture's parenting style is a mistake, though, because many factors, including family traditions, personality and personal circumstances, affect parenting. Nonetheless, learning about cultural differences in parenting can illuminate the things you're doing right in your home, and offer some positive alternatives for those things you'd like to change.

Nonetheless, learning about cultural differences in parenting can illuminate the things you're doing right in your home, and offer some positive alternatives for those things you'd like to change.

Attachment and Independence

Cultural norms play a large role in determining the level of attachment parents and children feel. For example, Pamela Druckerman, author of "Raising Bebe: One American Mother Discovers the Wisdom of French Parenting," notes that French parents encourage more independence in their children than American parents. French children, for example, attend summer camps starting as early as age 6. Most American parents cringe at the thought of sending young children away with strangers. American parents subscribing to the attachment theory of child development may co-sleep with babies and children, and practice baby wearing. Many European parents would consider these habits odd or confining.

Authority

Child Rearing Beliefs & Practices in Indian Culture

Learn More

How much control parents exert over children can also be influenced by culture. In traditional Chinese culture, for example, parents place emphasis on respect for authority, devotion to parents and high achievement, according to the Francis McClelland Institute in Tucson, Arizona. Children are expected to put family first and remain obedient to parents. Physical punishment is an acceptable means of achieving these goals. Many American parents adapt an authoritative parenting style, which blends setting limits with providing support.

In traditional Chinese culture, for example, parents place emphasis on respect for authority, devotion to parents and high achievement, according to the Francis McClelland Institute in Tucson, Arizona. Children are expected to put family first and remain obedient to parents. Physical punishment is an acceptable means of achieving these goals. Many American parents adapt an authoritative parenting style, which blends setting limits with providing support.

Family Structure and Care

In the U.S., the nuclear family is considered the ideal structure for raising children, but in many parts of the world, extended family and community members take a much larger role in child care and parenting, according to Meredith Small, author of "Kids: How Biology and Culture Shape the Way We Raise Children." Small, an anthropologist and expert on cultural variations in parenting, has discovered many surprising benefits to a communal approach to child-rearing. Additionally, parents vary in who they go to for parenting wisdom. In many traditional cultures, parents learn how to parent from their elders. In the U.S., parents are more likely to rely on the opinions of experts.

In many traditional cultures, parents learn how to parent from their elders. In the U.S., parents are more likely to rely on the opinions of experts.

Values

Chinese Culture & Parenting

Learn More

Cultural norms can significantly impact which values parents deem important and how they share those values with children. Most Europeans, for example, take a fairly relaxed view of alcohol and sex, while giving low priority to religion. Asian and Middle Eastern parents usually encourage traditional values of morality and virtue. When it comes to parental values, the U.S. is truly a melting pot, with parental views ranging from highly conservative to permissive.

Health and Care

Even ideas about health, nutrition and basic hygiene are often influenced by culture. In the United States, for example, Asian and Latino women are more likely to breastfeed and for longer periods than white or African-American women, according to the Early Head Start National Resource Center. Pasta, a staple in Italy, is viewed by many American moms as a starchy, simple carbohydrate with limited nutrition.

Pasta, a staple in Italy, is viewed by many American moms as a starchy, simple carbohydrate with limited nutrition.

The influence of the style of family education on the personality of the child

What role a child occupies in the family and how his communication with relatives develops directly depends on what he will become in the future, how he will look at the world and interact with people around him. The family is the cradle of a child's development. Knowing about the different styles of family education, their pros and cons, will allow you to develop your own style and create harmonious family relationships.

The role of the family in shaping the personality of the child

Relationships within the family are often perceived by the child as a role model. Most psychologists are sure that it is the flaws of upbringing in childhood that cause difficulties in communication in adulthood. The formation of the personality of the baby directly depends on what model of education is characteristic of his family.

Parents have a huge influence on their baby, since it is they, and not educators, coaches or teachers, who spend most of the time with the child, and their communication model becomes an example to follow.

There are many classifications of family education styles, which are based on various criteria for relationships within the family. In this article, we will introduce you to the classifications proposed by the following authors:

- J. Bolnwin;

- G. Craig;

- D. Elder;

- L.G. Sagotovskaya;

- E.G. Eidemiller.

Styles of family education according to J. Baldwin

In the classification of J. Baldwin, two styles of education are distinguished. The division between democratic and controlling style was based on such criteria as the nature of the requirements for the child, the degree of control, emotional support and evaluation.

| Democratic parenting style | Supervisory parenting style |

| There is a high level of trust in the family, everyone is ready to help each other. | A large number of prohibitions and rules. The child is perceived as a member of the family who does not have his own opinion and must listen to his parents in everything. The level of trust in the family is low. |

Research by psychologists has shown that children who were brought up in families with a democratic style of upbringing most often have the following characteristics:

- Tendency to leadership;

- Comprehensive development;

- Social activity;

- Sociability;

- Lack of empathy, lack of altruism.

In families with a controlling parenting style, children grow up:

- Suggestible;

- Obedient;

- Non-initiative;

- Alarming.

Such "pure" family parenting options are rare, most families adhere to a mixed style.

Classification of parenting styles by G. Kraig

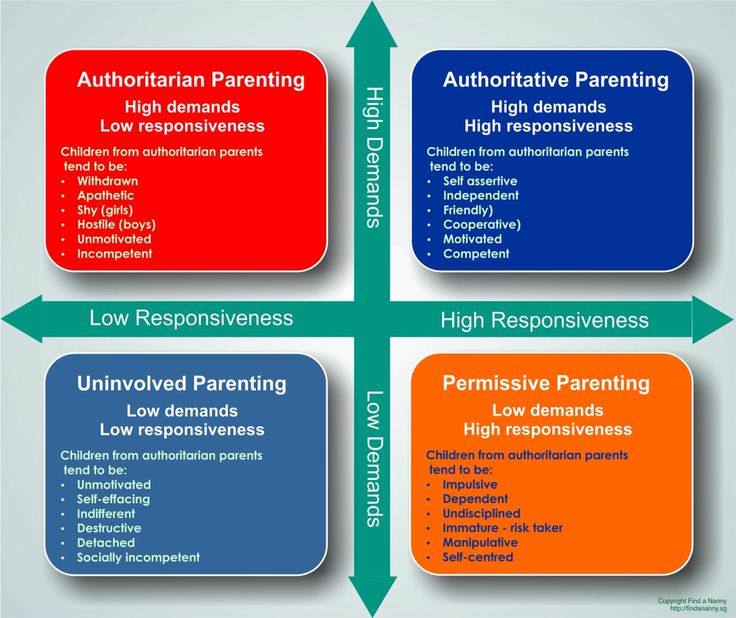

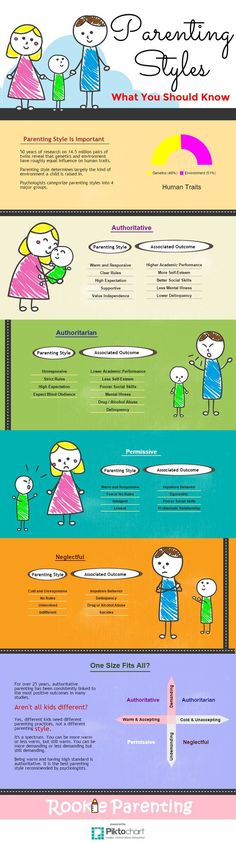

Styles of family education according to G. Kraig can be divided on the basis of two criteria: the degree of parental control and the trusting relationship in the family. The researcher identifies four main styles of education:

- The authoritative style of family education is one of the most harmonious. This parental position is based on trust in your child, but the level of control remains at a high level. As a result, friendly relations are established in the family, and the baby gets enough freedom for self-realization. Children in such families usually grow up purposeful and self-confident, as well as capable of self-control.

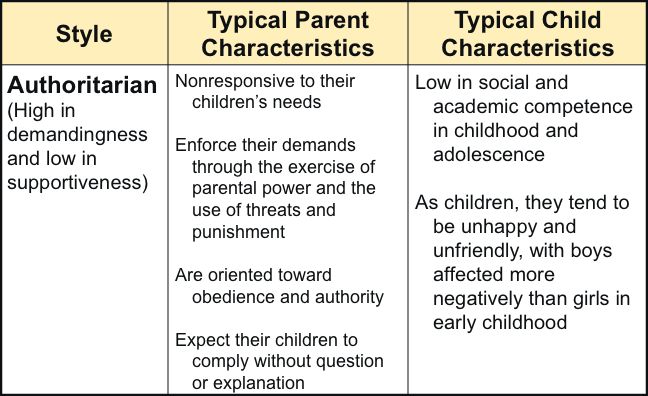

- An authoritarian parenting style most often leads to strained intra-family relationships. It is based on total control. A child in a family where this style of upbringing is followed becomes fearful, irritable, aggressive, dependent.

- The liberal style of family education is characterized by a low level of control over children and trusting relationships within the family.

The behavior of the child is practically not regulated, but at the same time, children learn to control themselves. Growing up, children most often become active and creative individuals.

The behavior of the child is practically not regulated, but at the same time, children learn to control themselves. Growing up, children most often become active and creative individuals. - With an indifferent parenting style, the child is given the maximum level of freedom. Adults devote little time to children, so relationships within such families are not warm. Using this style of family parenting is fraught with the risk that the child may grow up hostile and anti-social.

Styles of parenting according to D. Elder

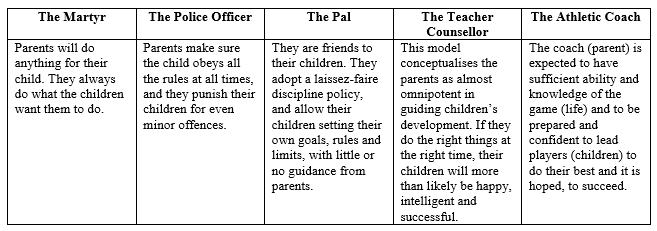

D. Elder distinguishes seven types of family education. The classification criteria are the degree of control and pressure on the child.

| Style of family education | Control level |

| Autocratic parenting style | Maximum (total control and suppression of the will of the child) |

| Authoritarian parenting style | High level of control (parents make decisions, but the child can express his opinion) |

| Democratic parenting style | Moderate (every family member has the right to vote) |

| Egalitarian parenting style | Self-control (the rights and obligations of adults and children are completely equal) |

| Permissive parenting style | Low supervision |

| Permissive parenting style | Lack of control (complete freedom of action of the child) |

| Ignoring parenting style | Complete lack of control and interest in the child's life |

The degree of control over the actions of the child is a very important indicator of the style of family education.

How much freedom a child is given in childhood depends on whether he grows up self-confident, active and enterprising, or, on the contrary, becomes an anxious and inactive person.

Classification of family education styles L.G. Sagotovskoy

This classification describes six possible parenting styles that differ in the degree of emotionality of the relationship between adults and the child, as well as the role of children in family life.

- The child is the main concern and goal of adult life;

- The child is the object of pedagogical efforts;

- Child helper, small adult;

- The child is a friend, an independent person;

- Child - "empty place";

- The child is a nuisance.

Variants of pathological styles of family education (EG Eidemiller)

The author of this classification identifies styles of family education that are abnormal and have a negative impact on the development of the child's personality. Parenting styles differ in the level of adult participation in the lives of children, the degree of control and attention of parents to the individual characteristics of the child.

Parenting styles differ in the level of adult participation in the lives of children, the degree of control and attention of parents to the individual characteristics of the child.

- Hypo-custody is insufficient care for a child. Children in such a situation are left to themselves, contacts within the family are minimal and superficial. The extreme degree of hypoprotection is neglect and pedagogical neglect.

- Dominant overprotection - excessive care for the child in conjunction with complete control of behavior. In such families there are a huge number of prohibitions. As a result, children may grow up to be dependent and lack of initiative.

- Indulgent overprotection is a parenting style that puts the child's desires and success at the forefront. Parents fulfill all the whims of their baby. Often, children who grew up in such “hothouse” conditions have a hard time in adulthood.

- Emotional rejection. With this parenting style, adults do not want to participate in the lives of children, often resorting to punishment.

Such "cold" parents may consider it their duty only to provide for the child and do not care about the emotional well-being of the baby.

Such "cold" parents may consider it their duty only to provide for the child and do not care about the emotional well-being of the baby. - Excessive requirements. Sometimes parents impose too many responsibilities on the child and demand from him what he is not yet capable of. This attitude towards the crumbs as a small adult often leads to increased anxiety and depression.

- Inconsistency. The chaotic style of family education, which may arise due to the lack of a single position among parents or their fear of seeming unloving to the baby. Floating boundaries of what is permitted and inconsistency develop in the child impulsiveness, insecurity, instability of self-esteem. A kid who does not have a clear picture of the world does not get the feeling of security and predictability he needs.

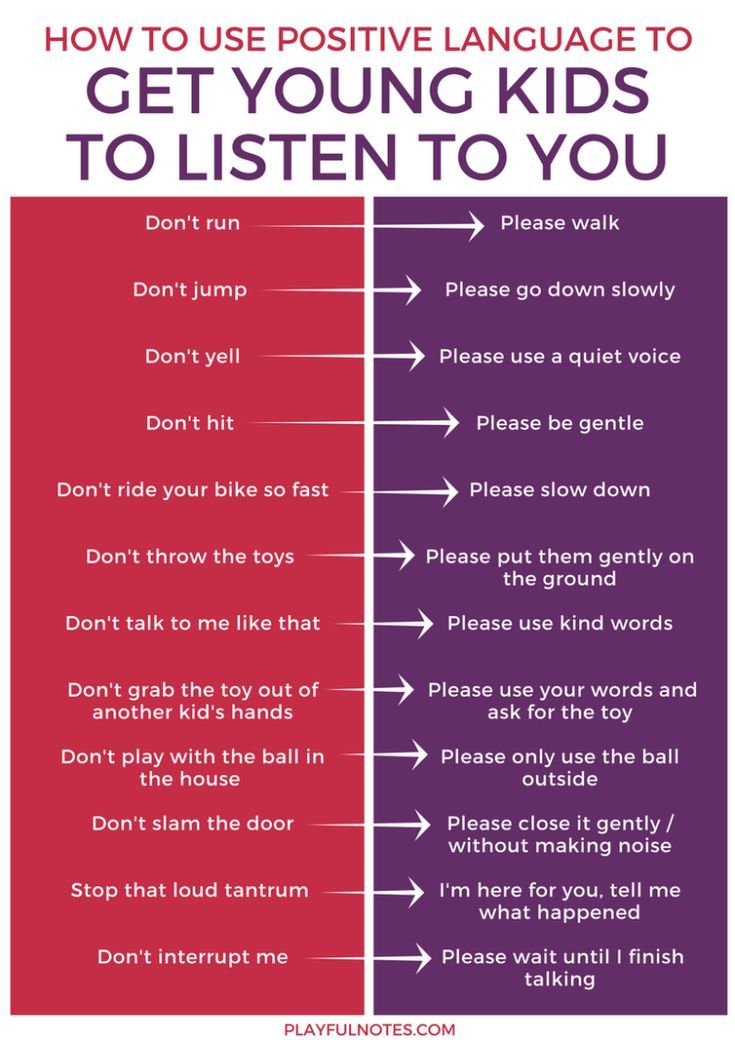

Advice for parents

In this article we have told you about the different styles of parenting. Although each of the authors gave the styles their own name and used different classification criteria, they all talked about the same thing. In the traditional classification, which generalizes the options proposed earlier, four main types of family education are presented: authoritarian (powerful), democratic (respectful), indulgent (overprotective), conniving (indifferent). Their features are clearly shown in the video:

In the traditional classification, which generalizes the options proposed earlier, four main types of family education are presented: authoritarian (powerful), democratic (respectful), indulgent (overprotective), conniving (indifferent). Their features are clearly shown in the video:

The authoritarian parenting style assumes that the word of the parents for the child is the law. Few children can retain their individuality at the same time, most often the baby grows up distrustful, withdrawn, dependent. During adolescence, the child may experience rebelliousness and antisocial behavior.

If you notice an authoritarian pattern of behavior behind you, try to change your attitude towards the child. It is necessary to reduce the pressure on the baby and pay attention to his own needs and desires.

The other extreme is the permissive style of family upbringing, in which everything is allowed for the child. Often parents use this parenting style to show their love, but this strategy does not lead to positive results. The absence of parental authority and any restrictions inadequately overestimates the child's self-esteem, which can lead to communication difficulties.

Often parents use this parenting style to show their love, but this strategy does not lead to positive results. The absence of parental authority and any restrictions inadequately overestimates the child's self-esteem, which can lead to communication difficulties.

The child's development is negatively affected by both total parental control and lack of discipline. Restrictions and prohibitions are very important for the baby. They teach him to control his actions and behave within the framework of social norms.

The most harmonious style of family education is the democratic style. It is a combination of discipline and respect for the freedom of the child. Adults do not infringe on the rights of children, and they, in turn, have a number of responsibilities. Close trusting relationships are established within the family. As a result, children grow up sociable, self-confident and independent.

Conclusions

The influence of the style of family education on the formation of a child's personality is an extremely important and urgent problem. What style you follow when raising your baby directly affects his self-esteem, sociability, activity, independence and, in general, his attitude to the world. The most harmonious and effective is the democratic style of education, which is based on equality, mutual respect, care and love.

What style you follow when raising your baby directly affects his self-esteem, sociability, activity, independence and, in general, his attitude to the world. The most harmonious and effective is the democratic style of education, which is based on equality, mutual respect, care and love.

Conclusion

We are confident that every parent wants only the best for their child and is aware of their responsibility for their development. A favorable climate in the family, love and respect - this is what a baby needs to be self-confident and enjoy exploring the world. Bringing your child to classes at the Constellation Montessori Children's Center, you can be sure that here he will be treated as a unique person, respect his feelings and appreciate his freedom of choice.

Article prepared by psychologist

Safonova Maria

The influence of the style of family education on the formation of the child's personality

05 Mar 2021 at 11:41 District online newspaper Nashe Otradnoe SVAO Moscow

A person is born, grows and most of his life is inextricably linked with the family. Happiness and a sense of fullness of life largely depend on family relationships. Olga Savchuk, psychologist of the Dialogue Family Center, tells.

Happiness and a sense of fullness of life largely depend on family relationships. Olga Savchuk, psychologist of the Dialogue Family Center, tells.

Family education plays an important role in the spiritual, moral and social formation of the younger generation. It is based on the principles of mutual understanding and mutual respect, where a child for parents is not only an object of education and training, but also a subject with their own rights and obligations.

The family is the first social group of different ages in which he learns to communicate, learns how men and women behave in various situations of interaction. In the family, children learn to assimilate the values, parameters of assessments and self-assessments, the norms that their parents supply and by which they begin to evaluate themselves, as well as their image as possessing certain features and qualities. It is in the family that the child masters almost all types of social activities: communication, work, teaching.

The family environment combines the personal characteristics of the parents, the conditions in which the family lives and the style of upbringing. Many factors influence the formation of upbringing in the family: the family’s lifestyle, the level of culture and education, ideas about raising parents, the parent’s emotional involvement in the process interaction with the child, the nature of the control of the child's behavior by the parents, the number of prohibitions, control and guardianship by adults.

The main goal of family education is the development of such important personality traits that will help her cope with the difficulties encountered in life.

Important tasks in education are the development of creativity, intellect, culture, physical health, primary work experience.

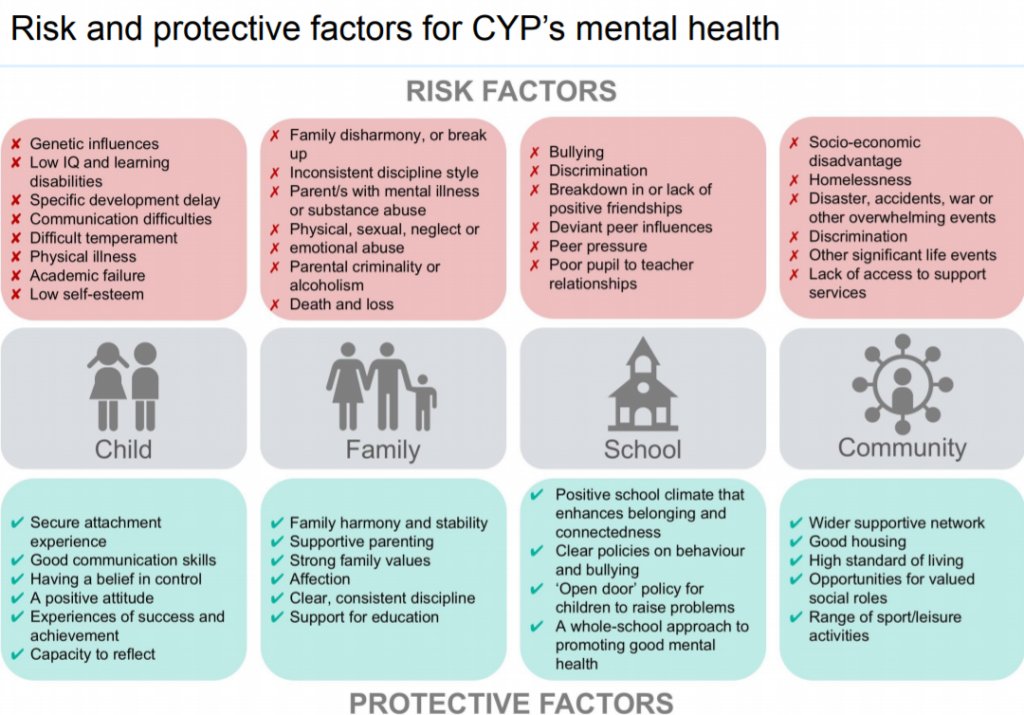

What are the consequences of an unstable upbringing style and disruption of emotional ties in the family:

— to an increase in deviant forms of behavior among children and youth

- increase in crime

- drug addiction

- suicide

Influence of parenting style on the development of the child's personality:

connivance - to the development of inadequate ideas about oneself; the lack of parental attention makes it impossible to believe in oneself, and the courage to cope with emerging life difficulties, in adequate self-esteem, self-confidence and the ability to follow certain rules of behavior are the most important moments in communication between parents and children.

The opinion of all family members is taken into account when solving important issues. The child is perceived as an independent person.

The opinion of all family members is taken into account when solving important issues. The child is perceived as an independent person.