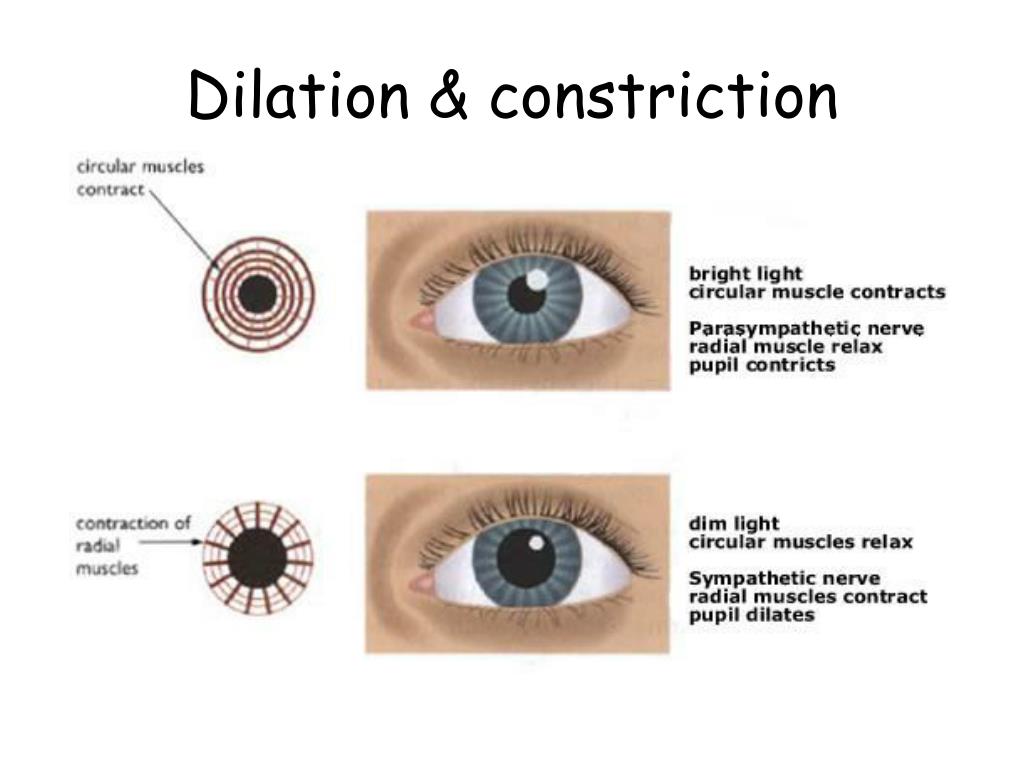

Contraction and dilation

Stages of labor and what to expect

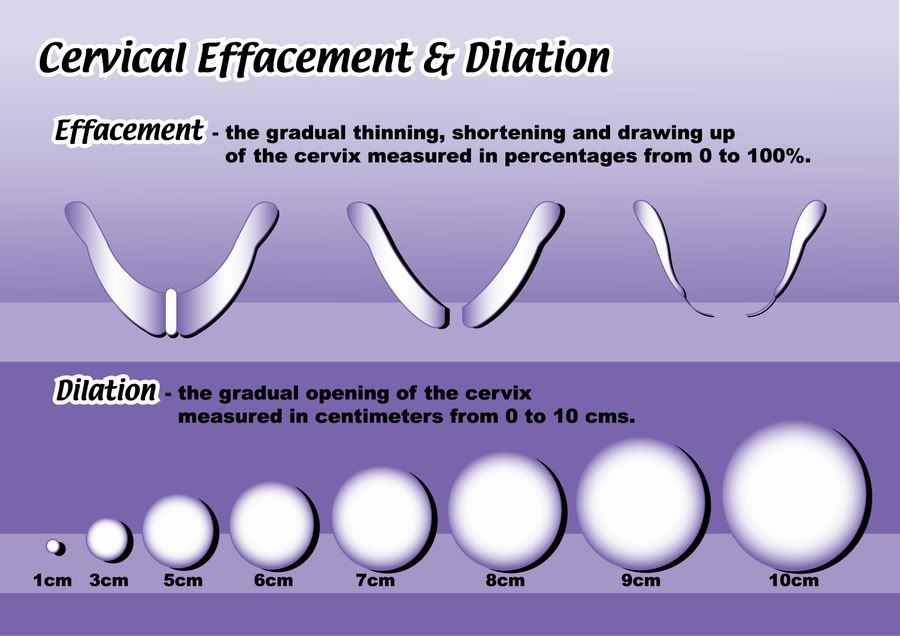

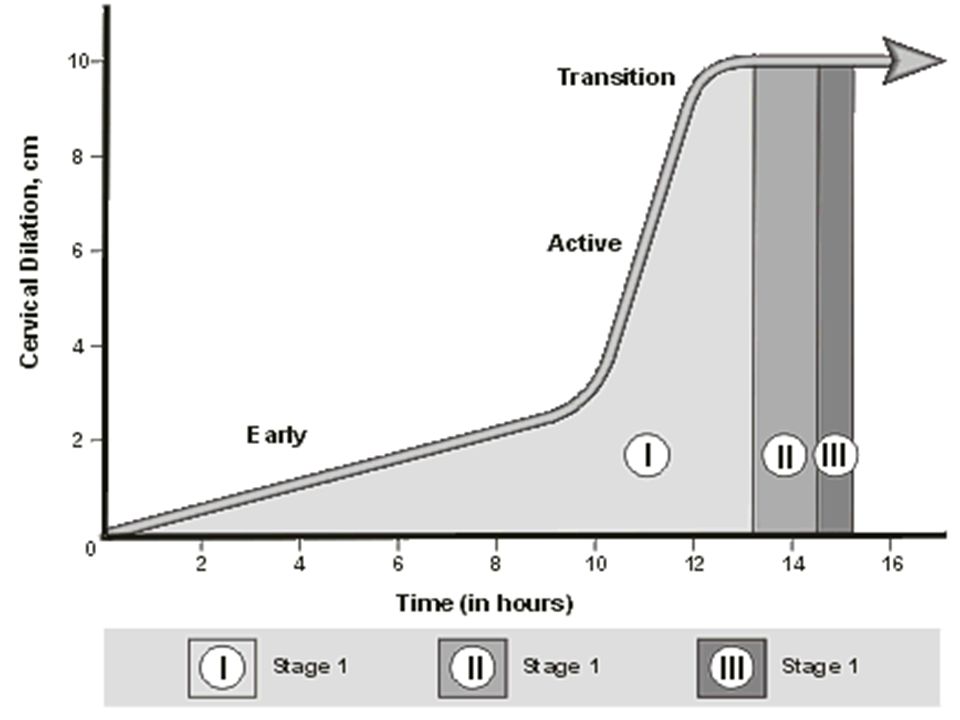

During labor, the cervix changes from a tightly closed entrance to a fully open exit for the baby.

Looking at a cervix dilation chart can help people to understand what’s happening at each stage of labor.

Each woman experience labor differently. In this article, we discuss in detail how the cervix is likely to change throughout the stages of labor, and what to expect at each stage.

Most of the time, the cervix is a small, tightly closed hole. It prevents anything from getting into or out of the uterus, which helps to protect the baby.

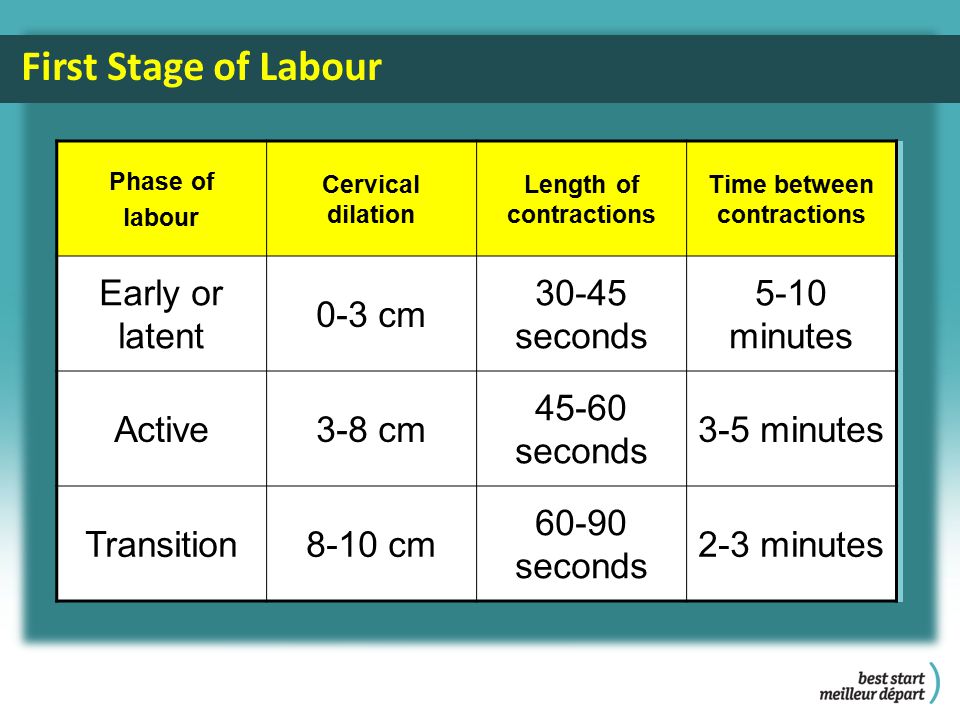

During labor, intense contractions of the uterus help move the baby down and eventually out of the pelvis, and into the vagina. These contractions put pressure on the cervix and cause it to expand slowly. Contractions tend to get stronger, closer together, and more regular as labor progresses.

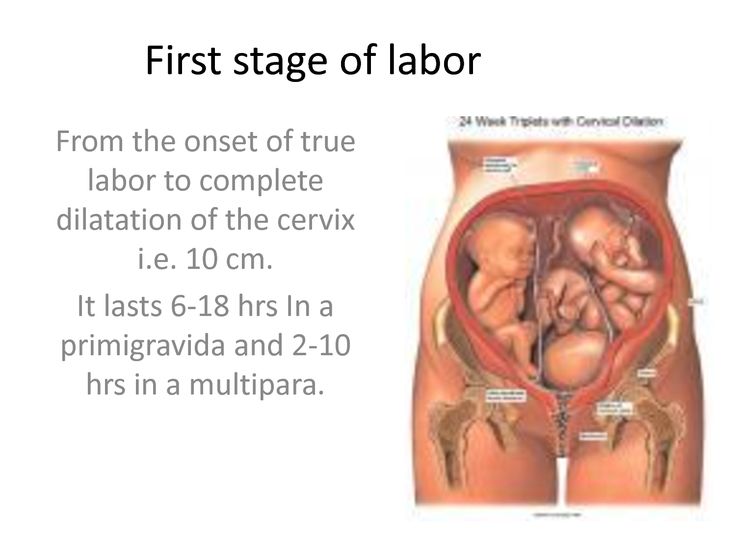

Most medical guides divide labor into three stages:

- Stage one: early, active, and transition labor.

Contractions begin, the cervix dilates, and the baby moves down in the pelvis. Stage one is complete when the cervix has dilated to 10 centimeters (cm).

- Stage two: The body begins pushing out the baby. During this stage, women often feel a strong urge to push. This stage ends with the birth of the baby.

- Stage three: Contractions push out the placenta. This stage ends with the delivery of the placenta, usually within a few minutes after the birth of the baby.

However, many women in labor may feel that they are experiencing many more stages than this.

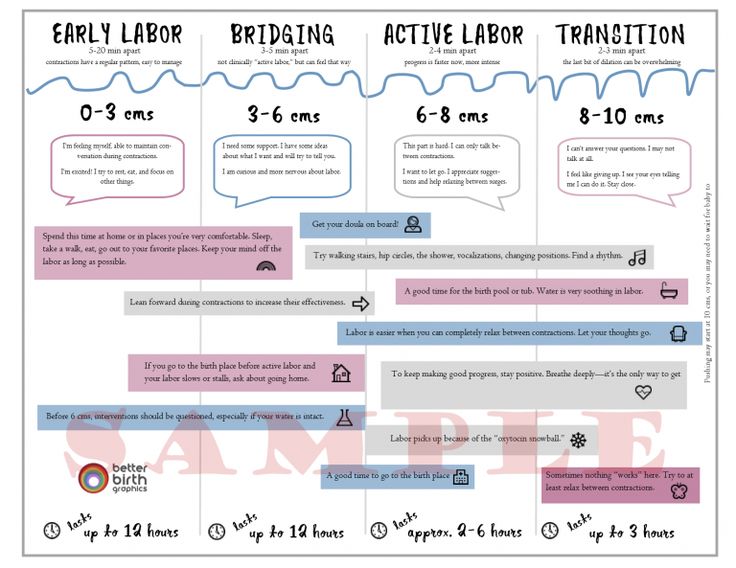

Stage one: early labor

In the early stages of labor, the cervix dilates to the following sizes:

- 1 cm, about the size of a cheerio

- 2 cm, the size of a small to medium-sized grape

- 3 cm, the size of a quarter

Late in pregnancy, the cervix may have already dilated several centimeters before a woman experiences any symptoms of labor.

Some women, particularly those who are giving birth for the first time, have difficulty telling whether labor has begun. This is because contractions in early labor are often mild and irregular, growing steadily more intense as the labor progresses and the cervix dilates.

This increase in intensity may take just a few hours or can take many days. Knowing whether this is actual labor can help people to prepare.

During true labor, a person’s contractions:

- are not just on one side of the body

- begin at the top of the uterus, and feel like they are pushing down

- get more intense and regular with time

- do not stop with rest or taking a warm shower

Some women may benefit from resting or eating a snack at this stage to ensure they have enough energy for the more tiring stages ahead.

Stage one: active labor

During the active stage of labor, the cervix dilates to the following sizes:

- 4 cm, the size of a small cookie, such as an Oreo

- 5 cm, the size of a mandarin orange

- 6 cm, the size of a small avocado or the top of a soda can

- 7 cm, the size of a tomato

Labor contractions become more intense and regular during active labor. Many women find that the main characteristic of active labor is that the contractions are extremely painful rather than uncomfortable.

Many women find that the main characteristic of active labor is that the contractions are extremely painful rather than uncomfortable.

At this stage of labor, some women may choose medication, such as an epidural to cope with the pain. Others prefer to manage the pain naturally. Changing positions, moving, and remaining hydrated can help with the pain of active labor.

Stage one: transition phase

During the transition phase of labor, the cervix dilates to the following sizes:

- 8 cm, the size of an apple

- 9 cm, the size of a donut

- 10 cm, the size of a large bagel

For many women, transition is the most challenging stage. However, it is also the shortest. Some people begin feeling an urge to push during the transition stage. It is also common to feel overwhelmed, hopeless, or unable to cope with the pain. Some women vomit.

Some women find that the coping strategies that worked well in the earlier stages of labor are no longer useful. Transition tends to be short and is a sign that the baby will soon arrive. Moving, changing positions, and visualization exercises can help.

Transition tends to be short and is a sign that the baby will soon arrive. Moving, changing positions, and visualization exercises can help.

The cervix continues dilating during transition, and transition ends when the cervix has fully dilated.

Stage two: full dilation and pushing

Once the cervix has reached 10 cm, it is time to push the baby out. Contractions continue but also produce a strong urge to push. This urge might feel like an intense need to have a bowel movement.

This stage can last anywhere from a few minutes to a few hours. It is often longer for those giving birth for the first time.

Historically, doctors told women to push according to a schedule, to count to 10, and to remain on their backs. Today, the advice is very different, and research says it is safe for women to push according to their body’s cues and for as long as feels comfortable.

Pushing from a standing or squatting position may also help speed things along. Allowing people to push from a range of positions gives the medical staff better access to the woman and baby should they need to assist with the delivery for any reason.

As a woman delivers the baby, she may feel an intense burning and stretching as her vagina and perineum stretch to accommodate the baby. This sensation typically lasts just a few minutes, though some women tear during this process.

Stage three: after the birth

Share on PinterestAfter delivery, the cervix will start to contract to its previous size.

A few minutes after the birth, a woman may experience weaker contractions. After a contraction or two, the body should expel the placenta.

If the body does not entirely expel the placenta, a doctor or midwife may have to help deliver it. Sometimes, they will give a woman an injection of synthetic oxytocin to speed up delivery and prevent excessive bleeding.

Shortly after delivery, the cervix begins contracting back down to its previous size. This process can take several days to several weeks.

As the uterus and cervix shrink, many women will feel some contractions. Most women bleed for several weeks after giving birth.

Labor is different for each woman. It typically lasts longer with a first birth, but the length and type of labor vary greatly between individuals.

Some people experience labor that consists of a weaker type of contraction for days or weeks before giving birth. Others give birth in a matter of minutes, while some labors take days. Most fall somewhere in the middle.

Labor often starts slowly, becoming progressively more intense. It may also start and stop, or slow during moments of stress or intrusion.

Visualizing the cervix expanding might help some people understand the source of labor pain, offering a sense of control and deeper insight into the processes of labor.

Signs, Progression & What To Expect

What to expect during labor and delivery.How does labor work?

As your pregnancy begins to wrap up, your body will prepare for labor and delivery. This is the process through which your baby will be born. Labor is often different for each person. Some have quick labors and some long, difficult labors. Other people may even experience labor that stalls or stops, leading to medical intervention.

Labor is often different for each person. Some have quick labors and some long, difficult labors. Other people may even experience labor that stalls or stops, leading to medical intervention.

Early labor

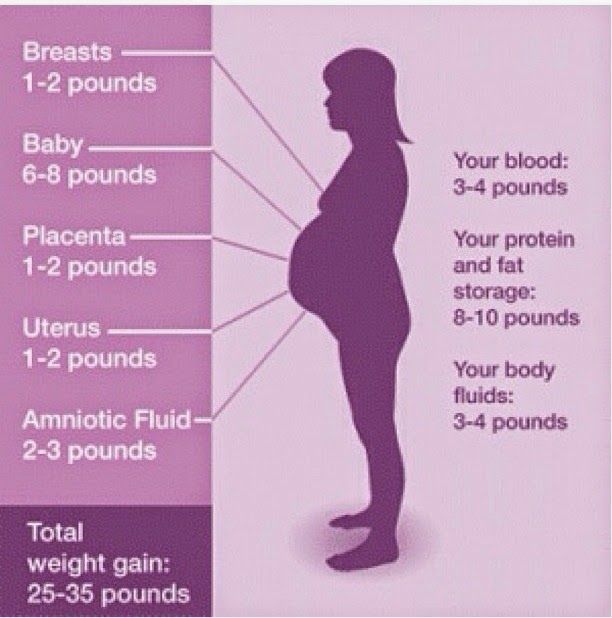

The average labor lasts 12 to 24 hours for a first birth and is typically shorter (eight to 10 hours) for other births. Throughout this time, you’ll experience three stages of labor. The first stage of labor is usually the longest and it ranges from when you first go into labor until your cervix is open. The beginning of this stage is called early labor. Early labor is described as dilating from 0 to 6 centimeters.

Active labor

As you progress and your contractions become stronger, you’ll move into the second part of the first stage of labor called active labor. Active labor is dilating from 6 to 8 centimeters and then transitioning into the second stage as you dilate 8 to 10 centimeters. Your contractions will become even stronger during active labor and your cervix will open up quickly. The second stage of labor is when you push. This is the phase of your labor when you will actually give birth to your baby.

The second stage of labor is when you push. This is the phase of your labor when you will actually give birth to your baby.

Afterbirth

The third stage is the point when you deliver the placenta. This is also called afterbirth.

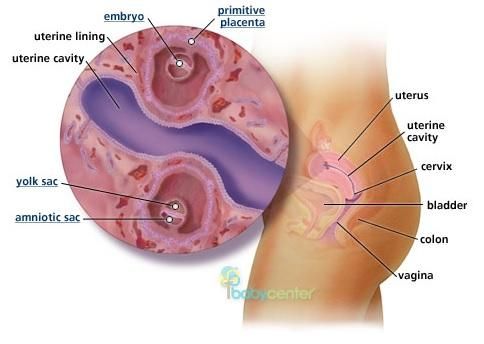

During these stages, your body prepares for childbirth by going through dilation and effacement.

- Dilation: This is a process where your cervix stretches and opens to make way for your baby’s birth. Dilation is measured from 1 to 10 centimeters. Your provider will do a vaginal exam to check how dilated you are throughout your labor. You’ll be 10 centimeters dilated in the second stage of labor for the delivery of your baby.

- Effacement: The cervix not only stretches during labor but it also becomes thinner. The shortening and thinning of your cervix are measured in percentages. You’ll progress from 0% to 100% effacement during your labor.

Think of your cervix as a round doorway that needs to stretch outward and get thinner before your baby can pass through it. This stretching and thinning are caused by contractions. Contractions can be described in a variety of ways ranging from uncomfortable, period-like cramps to a painful tightening of your abdomen. You might also feel a dull ache in your back and lower abdomen, as well as pressure in your pelvis.

This stretching and thinning are caused by contractions. Contractions can be described in a variety of ways ranging from uncomfortable, period-like cramps to a painful tightening of your abdomen. You might also feel a dull ache in your back and lower abdomen, as well as pressure in your pelvis.

When you have a contraction, it’s actually the muscles of your uterus tightening at regular intervals to dilate and efface (open and thin) your cervix. During contractions, your abdomen becomes hard. Between contractions, your uterus relaxes and your abdomen becomes soft. Even though they can be painful, each contraction helps move you forward through your labor.

How will I know I’m in labor?

It can be difficult to know when you’re in true labor. First-time parents, in particular, might mistake other symptoms or irregular practice contractions (called Braxton Hicks contractions) for true labor. True labor has a pattern and progresses steadily over time.

When you’re in true labor, you’ll notice a pattern in your contractions. Instead of the irregular Braxton Hicks contractions you might have felt during your pregnancy that showed up and then went away randomly, these contractions will keep coming for an extended period of time. There are three things you’ll want to look for when you are in true labor.

Instead of the irregular Braxton Hicks contractions you might have felt during your pregnancy that showed up and then went away randomly, these contractions will keep coming for an extended period of time. There are three things you’ll want to look for when you are in true labor.

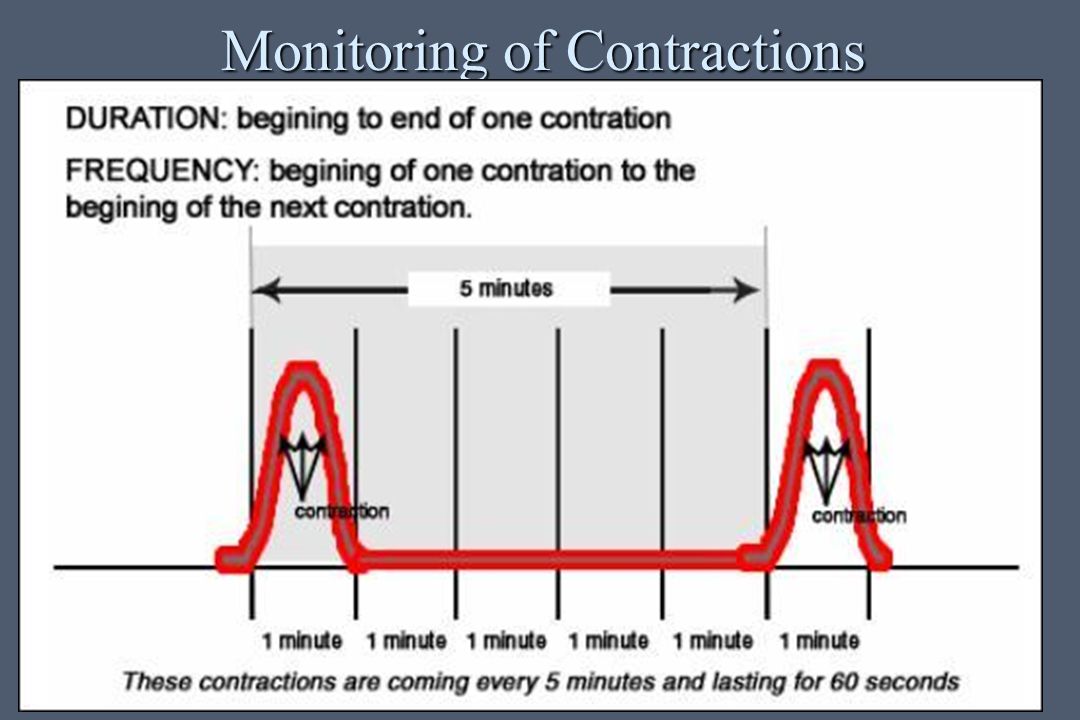

- Frequency: How often are your contractions happening? Keep track of them with a journal or labor app on your phone to make sure they're coming at regular intervals.

- Duration: How long are each of your contractions? As your labor continues, your contractions will last longer and longer. Use a stopwatch, watch a clock or keep the timer on your phone handy so you can record the length of each contraction.

- Intensity: Are your contractions getting stronger? Contractions can get stronger and you might feel them more intensely as you move through the stages of labor. Keep track of how your contractions feel over time.

Are there any signs that I will go into labor soon?

Many women have several pre-labor signs that might hint that labor will start soon. These signs of labor include:

These signs of labor include:

- Backaches.

- Diarrhea.

- Weight loss.

- Nesting (cleaning and organizing your home).

No one knows for sure what causes labor to start, but several hormonal and physical changes may point to the beginning of labor.

What are Braxton Hicks contractions?

Often called practice contractions, Braxton Hicks are irregular contractions that don’t cause cervical change. Think of them as a test run for the real thing. They can start happening at the end of your pregnancy and can startle people into thinking they’re in labor. This is called false labor.

A Braxton Hicks contraction will feel like a sudden, sharp tightening of your abdominal muscles. Even though this is very similar to how a contraction feels, Braxton Hicks contractions don’t follow a pattern or progress over time. They may also stop when you lay down or relax. When you start to experience these practice contractions, keep track of them. Writing them down is the best way to tell the difference between true and false labor.

What is lightening?

Lightening is the process where your baby settles or lowers into your pelvis. This can happen a few weeks or a few hours before labor. When this happens, you may experience some increased lower pelvic pressure. Because your uterus rests on your bladder more after lightening, you might also feel the need to urinate more frequently. You might notice that you’re not as short of breath once your baby drops.

What’s the mucus plug and what does it mean when it falls out?

During pregnancy, a thick piece of mucus called a plug blocks the cervical opening. This plug keeps your uterus closed off from the birth canal and the outside of your body and prevents bacteria from traveling into your uterus. When your cervix begins to soften, thin, and open, the mucus is expelled into your vagina. Not every mucus plug will look the same. Possible colors of the mucus plug can include:

- Clear.

- Pink.

- Slightly bloody.

Labor could start shortly after you lose your mucus plug or it could begin several weeks later.

How do I time my contractions?

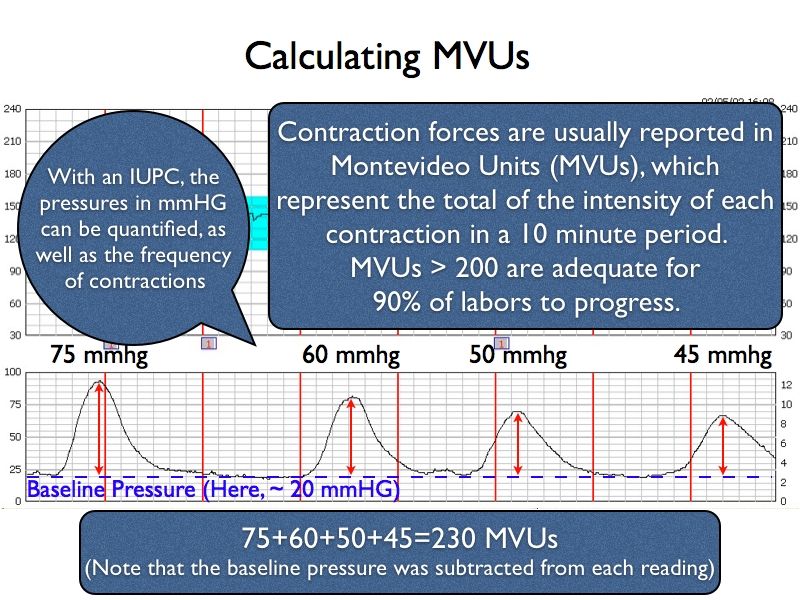

Once you’re in labor, it’s important to keep track of your contractions. Your healthcare provider will need to know how long your contractions are lasting (duration), how often they’re happening (frequency) and how intense they are. When you’re timing your contractions, you will want to have a way to record each one – pen and paper or through an app on your phone – and a timer or clock. Make sure you keep track of each contraction from start to end, as well as the time between each contraction. This second measurement will help your provider know the frequency of your contractions.

It can be difficult to record the intensity of your contractions. This can really vary from person to person. Often, an easy way to keep track of the intensity of your contractions is to record when you cannot walk, talk or laugh during contractions.

Is there anything I can do to cope with contractions?

As you approach the end of your pregnancy, it’s a good idea to talk to your healthcare provider about different ways to deal with pain and discomfort during labor. There are several options your provider will discuss with you to relieve pain.

There are several options your provider will discuss with you to relieve pain.

There are also ways to deal with the discomforts of labor at home or without medication, including:

- Distract yourself by taking a walk, going shopping or watching a movie.

- Soak in a warm tub or take a warm shower. Make sure to ask your healthcare provider if you should take a tub bath if your bag of water has broken.

- Sit on a birth ball.

- Listen to music.

- Dim the lights.

- Use aromatherapy.

- Get a massage.

- Stay in an upright position. This can help with the descent and rotation of your baby.

- Try to sleep if it’s evening. You’ll want to store up your energy before active labor and delivery.

How will I know when my water breaks?

You may be familiar with the common phrase “my water broke.” This is actually the rupturing of your amniotic membrane. During pregnancy, your baby is inside a fluid-filled sac, also called your bag of water. When this membrane breaks, you might feel a sudden gush or trickle of fluid. Like many parts of labor and childbirth, this experience can be different for each person. The fluid is usually odorless and may look clear or straw-colored.

When this membrane breaks, you might feel a sudden gush or trickle of fluid. Like many parts of labor and childbirth, this experience can be different for each person. The fluid is usually odorless and may look clear or straw-colored.

Unlike urine leakage that some pregnant women experience, this won’t stop. The amniotic fluid will often continue to leak.

If your water breaks, call your healthcare provider. Let your provider know what time your water broke, the amount (trickle or gush), the color of the fluid and the odor. Don't use tampons if your water has broken. Your labor might start right after your water breaks. Some women are already in labor when their water breaks while others don’t experience the first stage of labor for a while after their water breaks.

When should I call my healthcare provider or go to the hospital?

If you ever have any questions, it’s always a good idea to call your healthcare provider. Your provider can answer any questions you have about true labor versus false labor and discuss how you’re feeling. When you start to notice that you’re having regular contractions, call your provider to talk about when you should go to the hospital. Some women are able to stay home throughout early labor, while others may need to come in sooner.

When you start to notice that you’re having regular contractions, call your provider to talk about when you should go to the hospital. Some women are able to stay home throughout early labor, while others may need to come in sooner.

You should also call your healthcare provider if you:

- Think your water has broken. This could be a sudden gush of fluid or a trickle of fluid that leaks steadily.

- Are bleeding (more than spotting).

- Experience contractions that are very uncomfortable and have been coming every five minutes, lasting for one minute and have been like this for one hour.

What happens when I get to the hospital?

When you get to the hospital, you will check in at the labor and delivery desk. Most people will be seen in a triage room first. This is part of the admission process. It’s usually recommended that you only bring one person with you to the triage room.

From the triage room, you will be taken to the labor, delivery and recovery (LDR) room. You’ll be asked to wear a hospital gown. Your pulse, blood pressure and temperature will be checked. An external fetal monitor will be placed on your abdomen for a short time to check for uterine contractions and measure your baby’s heart rate. Your healthcare provider will also examine your cervix to see how far labor has progressed. An intravenous (IV) line might be placed into a vein in your arm to deliver fluids and medications.

You’ll be asked to wear a hospital gown. Your pulse, blood pressure and temperature will be checked. An external fetal monitor will be placed on your abdomen for a short time to check for uterine contractions and measure your baby’s heart rate. Your healthcare provider will also examine your cervix to see how far labor has progressed. An intravenous (IV) line might be placed into a vein in your arm to deliver fluids and medications.

What does it mean to have labor induced?

Labor doesn’t always start naturally or progress as it should. In these cases, your provider might talk to you about inducing labor. This is a medical procedure where labor is started by your healthcare provider. This could happen if you:

- Are past your due date.

- Have health complications like high blood pressure, preeclampsia, infection or diabetes.

- Had your water break but labor didn’t start.

- Have low levels of amniotic fluid.

Your labor can be advanced or induced in several ways. Your provider will advise you about the best and safest option depending on your health. Inducing labor can be done by using:

Your provider will advise you about the best and safest option depending on your health. Inducing labor can be done by using:

- Medications (oxytocin) given through an IV (directly into your vein).

- Breaking your amniotic sac (water).

- Separating the amniotic membrane (the sac of fluid the baby is inside within your uterus) from your uterine wall. This is also called sweeping the membrane.

- Softening your cervix and encouraging it to open with a medication that can be placed directly in your vagina.

Labor induction can take longer than spontaneous labor because the cervical ripening process takes time.

What are the different types of delivery?

There are two main types of delivery: vaginal and cesarean section (C-section). During vaginal birth, your baby will pass naturally through the birth canal. A C-section is a surgical procedure where your provider makes an incision (cut) in your abdomen and delivers the baby in an operating room. Vaginal delivery is the most common type of birth. However, sometimes you might need a C-section for a variety of reasons, including:

Vaginal delivery is the most common type of birth. However, sometimes you might need a C-section for a variety of reasons, including:

- If your baby is not in the head-down position.

- If your baby is too large to naturally pass through your pelvis.

- If your baby is in distress.

- If the placenta blocks your cervix (a condition called placenta previa).

- If you have health issues or complications that make a C-section the safest option.

- If there’s an emergency situation that requires your baby to be delivered quickly.

In many cases, a cesarean delivery is not determined until after labor begins.

How long will I be in the hospital?

The length of your hospital stay can depend on the hospital where you deliver your baby and the type of delivery you have. Typically, you will stay in the hospital longer if you have a C-section delivery because it's a surgical procedure. You may also need to stay in the hospital for a longer period of time if you experience any complications or health issues during your delivery.

A note from Cleveland Clinic:

You're bound to a lot of feelings as you prepare to deliver your baby. It's normal to feel both excited and nervous. Discussing the signs and symptoms with your healthcare provider can help you know what to expect. Your partner and healthcare team are here to support you and will help you remain as comfortable as possible through the delivery process.

Rules for reducing and expanding fractions

- Arithmetic

- Geometry

- tables

- Arithmetic

- Rules for reducing and expanding fractions

To solve certain problems, it is often necessary to convert fractions using the extension method or the reduction method .

Since the value of a fraction remains unchanged, if the numerator and denominator of this fraction are multiplied or divided by the same non-zero number taken, the fraction can be changed depending on current requirements.

Fraction expansion

A fraction transformation in which the numerator and denominator are multiplied by a number with the same value is called fraction expansion .

| 1 2 | = | 1 × 2 2 × 2 | = | 2 4 |

Two-fourths fraction obtained by expansion by two.

| 1 5 | = | 1 × 5 5 × 5 | = | 5 25 |

Five twenty-fifths fraction obtained by expanding by five.

| 7 8 | = | 7 × 3 8 × 3 | = | 21 24 |

Fraction twenty-one twenty-fourths, obtained by expansion by three.

Fraction reduction

A fraction conversion in which the numerator and denominator are divided by a number with the same value is called fraction reduction .

| 2 4 | = | 2 : 2 4 : 2 | = | 1 2 |

One-half fraction obtained by reducing two-fourths by two.

| 5 25 | = | 5 : 5 25 : 5 | = | 1 5 |

One-fifth fraction obtained by reducing five from five-twenty-fifths.

| 21 24 | = | 21:3 24:3 | = | 7 8 |

Fraction seven-eighths, obtained by reducing by three from the fraction twenty-one twenty-fourth.

© 2012 – 2022

Reduction and "expansion" of fractions, Comparison of fractions; reduction to a common denominator

Reduction and “expansion” of a fraction

The value of a fraction will not change if the numerator and denominator of the fraction are multiplied by the same number.

For example,

This transformation of a fraction is called "expanding" the fraction. The fraction is obtained by expanding by 6 from the fraction

The value of the fraction will not change if the numerator and denominator of the fraction are divided by the same number.

For example This conversion is called fraction reduction.

A fraction can only be reduced if the numerator and denominator have the same divisors (ie if they are not coprime). The reduction can be done gradually or immediately at the GCD.

Example: Reduce a fraction Applying the sign of divisibility by 4, we see that 4 is a common divisor of the numerator and denominator. Reducing by 4 we have

Reducing by 4 we have

27 and 36 have a common divisor of 9, reducing by 9 we have Further reduction is impossible (3 and 4 are coprime numbers).

We get the same result if we find the GCD of numbers 108 and 144. It is equal to 36. Reducing by 36 we get

After reducing by GCD we get an irreducible fraction

Comparison of fractions; reduction to a common denominator

Of two fractions with the same numerator, the fraction with the smaller denominator is larger. For example:

;

Of two fractions with the same denominator, the larger fraction is the one with the larger numerator.

For example:

To compare two fractions that have different numerator and denominator, you need to convert one or both fractions so that their denominators become the same. To do this, you can, for example, expand the first fraction by the denominator of the second, and the second by the denominator of the first.

Example. Compare fractions Expand the first fraction by 12 and the second by 8; we have:

Now the denominators are the same. Comparing the numerators, we see that the second fraction is greater than the first.

Comparing the numerators, we see that the second fraction is greater than the first.

The applied conversion of fractions is called bringing them to a common denominator.

To reduce several fractions to a common denominator, you can expand each of them by the product of the denominators of the others. For example, to reduce the fraction

to a common denominator, we expand the first by 5 6=30, the second 8 5=40, the third 8 6=48.

We get the common denominator will be the product of the denominators of all given fractions (8 6 5=240).

This common denominator is the simplest and in many cases the most practical. Its only inconvenience is that the common denominator can be quite large, while it can be chosen to be smaller. Namely, any common multiple (in particular, LCM) of these denominators can be taken as a common denominator. Then you need to expand each fraction by a quotient obtained from dividing the common multiple by the denominator of the fraction taken (this quotient is called an additional factor).