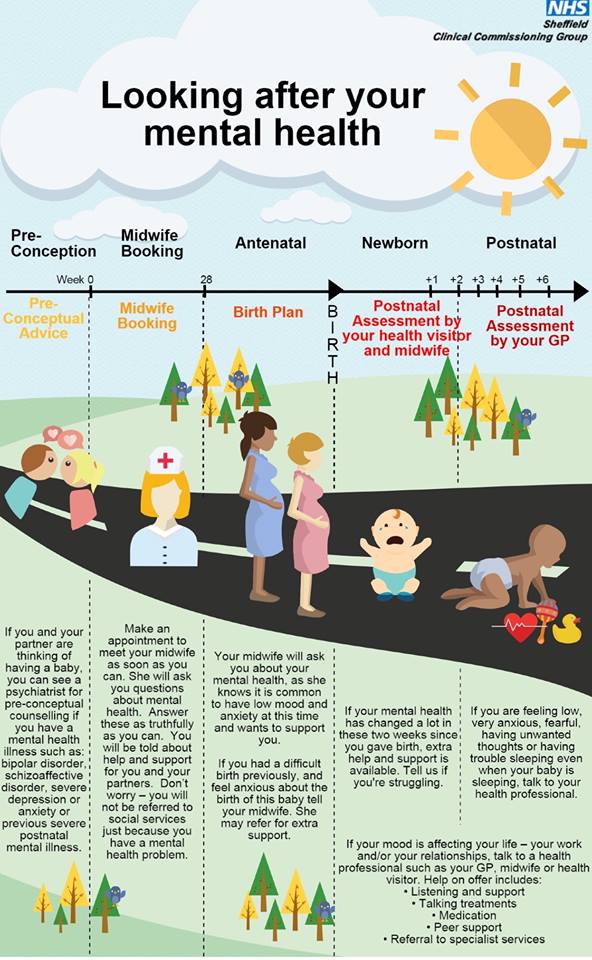

Antenatal depression and anxiety

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders. This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.

Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.

For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Drugs

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Misusing alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs can have both immediate and long-term health effects.The misuse and abuse of alcohol, tobacco, illicit drugs, and prescription medications affect the health and well-being of millions of Americans. NSDUH estimates allow researchers, clinicians, policymakers, and the general public to better understand and improve the nation’s behavioral health. These reports and detailed tables present estimates from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH).

Alcohol

Data:

- Among the 133.1 million current alcohol users aged 12 or older in 2021, 60.0 million people (or 45.1%) were past month binge drinkers.

The percentage of people who were past month binge drinkers was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (29.2% or 9.8 million people), followed by adults aged 26 or older (22.4% or 49.3 million people), then by adolescents aged 12 to 17 (3.8% or 995,000 people). (2021 NSDUH)

The percentage of people who were past month binge drinkers was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (29.2% or 9.8 million people), followed by adults aged 26 or older (22.4% or 49.3 million people), then by adolescents aged 12 to 17 (3.8% or 995,000 people). (2021 NSDUH) - Among people aged 12 to 20 in 2021, 15.1% (or 5.9 million people) were past month alcohol users. Estimates of binge alcohol use and heavy alcohol use in the past month among underage people were 8.3% (or 3.2 million people) and 1.6% (or 613,000 people), respectively. (2021 NSDUH)

- In 2020, 50.0% of people aged 12 or older (or 138.5 million people) used alcohol in the past month (i.e., current alcohol users) (2020 NSDUH)

- Among the 138.5 million people who were current alcohol users, 61.6 million people (or 44.4%) were classified as binge drinkers and 17.7 million people (28.8% of current binge drinkers and 12.8% of current alcohol users) were classified as heavy drinkers (2020 NSDUH)

- The percentage of people who were past month binge alcohol users was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (31.

4%) compared with 22.9% of adults aged 26 or older and 4.1% of adolescents aged 12 to 17 (2020 NSDUH)

4%) compared with 22.9% of adults aged 26 or older and 4.1% of adolescents aged 12 to 17 (2020 NSDUH) - Excessive alcohol use can increase a person’s risk of stroke, liver cirrhosis, alcoholic hepatitis, cancer, and other serious health conditions

- Excessive alcohol use can also lead to risk-taking behavior, including driving while impaired. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that 29 people in the United States die in motor vehicle crashes that involve an alcohol-impaired driver daily

Programs/Initiatives:

- STOP Underage Drinking interagency portal - Interagency Coordinating Committee on the Prevention of Underage Drinking

- Interagency Coordinating Committee on the Prevention of Underage Drinking

- Talk. They Hear You.

- Underage Drinking: Myths vs. Facts

- Talking with your College-Bound Young Adult About Alcohol

Relevant links:

- National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors

- Department of Transportation Office of Drug & Alcohol Policy & Compliance

- Alcohol Policy Information Systems Database (APIS)

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

Tobacco

Data:

- In 2020, 20.

7% of people aged 12 or older (or 57.3 million people) used nicotine products (i.e., used tobacco products or vaped nicotine) in the past month (2020 NSDUH)

7% of people aged 12 or older (or 57.3 million people) used nicotine products (i.e., used tobacco products or vaped nicotine) in the past month (2020 NSDUH) - Among past month users of nicotine products, nearly two thirds of adolescents aged 12 to 17 (63.1%) vaped nicotine but did not use tobacco products. In contrast, 88.9% of past month nicotine product users aged 26 or older used only tobacco products (2020 NSDUH)

- Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death, often leading to lung cancer, respiratory disorders, heart disease, stroke, and other serious illnesses. The CDC reports that cigarette smoking causes more than 480,000 deaths each year in the United States

- The CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health reports that more than 16 million Americans are living with a disease caused by smoking cigarettes

Electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use data:

- In 2021, 13.2 million people aged 12 or older (or 4.7%) used an e-cigarette or other vaping device to vape nicotine in the past month.

The percentage of people who vaped nicotine was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (14.1% or 4.7 million people), followed by adolescents aged 12 to 17 (5.2% or 1.4 million people), then by adults aged 26 or older (3.2% or 7.1 million people).

The percentage of people who vaped nicotine was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (14.1% or 4.7 million people), followed by adolescents aged 12 to 17 (5.2% or 1.4 million people), then by adults aged 26 or older (3.2% or 7.1 million people). - Among people aged 12 to 20 in 2021, 11.0% (or 4.3 million people) used tobacco products or used an e-cigarette or other vaping device to vape nicotine in the past month. Among people in this age group, 8.1% (or 3.1 million people) vaped nicotine, 5.4% (or 2.1 million people) used tobacco products, and 3.4% (or 1.3 million people) smoked cigarettes in the past month. (2021 NSDUH)

- Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2020 National Youth Tobacco Survey. Among both middle and high school students, current use of e-cigarettes declined from 2019 to 2020, reversing previous trends and returning current e-cigarette use to levels similar to those observed in 2018

- E-cigarettes are not safe for youth, young adults, or pregnant women, especially because they contain nicotine and other chemicals

Resources:

- Tips for Teens: Tobacco

- Tips for Teens: E-cigarettes

- Implementing Tobacco Cessation Programs in Substance Use Disorder Treatment Settings

- Synar Amendment Program

Links:

- Truth Initiative

- FDA Center for Tobacco Products

- CDC Office on Smoking and Health

- National Institute on Drug Abuse: Tobacco, Nicotine, and E-Cigarettes

- National Institute on Drug Abuse: E-Cigarettes

Opioids

Data:

- Among people aged 12 or older in 2021, 3.

3% (or 9.2 million people) misused opioids (heroin or prescription pain relievers) in the past year. Among the 9.2 million people who misused opioids in the past year, 8.7 million people misused prescription pain relievers compared with 1.1 million people who used heroin. These numbers include 574,000 people who both misused prescription pain relievers and used heroin in the past year. (2021 NSDUH)

3% (or 9.2 million people) misused opioids (heroin or prescription pain relievers) in the past year. Among the 9.2 million people who misused opioids in the past year, 8.7 million people misused prescription pain relievers compared with 1.1 million people who used heroin. These numbers include 574,000 people who both misused prescription pain relievers and used heroin in the past year. (2021 NSDUH) - Among people aged 12 or older in 2020, 3.4% (or 9.5 million people) misused opioids in the past year. Among the 9.5 million people who misused opioids in the past year, 9.3 million people misused prescription pain relievers and 902,000 people used heroin (2020 NSDUH)

- According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Understanding the Epidemic, an average of 128 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose

Resources:

- Medication-Assisted Treatment

- Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit

- TIP 63: Medications for Opioid Use Disorder

- Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Criminal Justice Settings

- Opioid Use Disorder and Pregnancy

- Clinical Guidance for Treating Pregnant and Parenting Women With Opioid Use Disorder and Their Infants

- The Facts about Buprenorphine for Treatment of Opioid Addiction

- Pregnancy Planning for Women Being Treated for Opioid Use Disorder

- Tips for Teens: Opioids

- Rural Opioid Technical Assistance Grants

- Tribal Opioid Response Grants

- Provider’s Clinical Support System - Medication Assisted Treatment Grant Program

Links:

- National Institute on Drug Abuse: Opioids

- National Institute on Drug Abuse: Heroin

- HHS Prevent Opioid Abuse

- Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America

- Addiction Technology Transfer Center (ATTC) Network

- Prevention Technology Transfer Center (PTTC) Network

Marijuana

Data:

- In 2021, marijuana was the most commonly used illicit drug, with 18.

7% of people aged 12 or older (or 52.5 million people) using it in the past year. The percentage was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (35.4% or 11.8 million people), followed by adults aged 26 or older (17.2% or 37.9 million people), then by adolescents aged 12 to 17 (10.5% or 2.7 million people).

7% of people aged 12 or older (or 52.5 million people) using it in the past year. The percentage was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (35.4% or 11.8 million people), followed by adults aged 26 or older (17.2% or 37.9 million people), then by adolescents aged 12 to 17 (10.5% or 2.7 million people). - The percentage of people who used marijuana in the past year was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (34.5%) compared with 16.3% of adults aged 26 or older and 10.1% of adolescents aged 12 to 17 (2020 NSDUH)

- Marijuana can impair judgment and distort perception in the short term and can lead to memory impairment in the long term

- Marijuana can have significant health effects on youth and pregnant women.

Resources:

- Know the Risks of Marijuana

- Marijuana and Pregnancy

- Tips for Teens: Marijuana

Relevant links:

- National Institute on Drug Abuse: Marijuana

- Addiction Technology Transfer Centers on Marijuana

- CDC Marijuana and Public Health

Emerging Trends in Substance Misuse:

- Methamphetamine—In 2019, NSDUH data show that approximately 2 million people used methamphetamine in the past year.

Approximately 1 million people had a methamphetamine use disorder, which was higher than the percentage in 2016, but similar to the percentages in 2015 and 2018. The National Institute on Drug Abuse Data shows that overdose death rates involving methamphetamine have quadrupled from 2011 to 2017. Frequent meth use is associated with mood disturbances, hallucinations, and paranoia.

Approximately 1 million people had a methamphetamine use disorder, which was higher than the percentage in 2016, but similar to the percentages in 2015 and 2018. The National Institute on Drug Abuse Data shows that overdose death rates involving methamphetamine have quadrupled from 2011 to 2017. Frequent meth use is associated with mood disturbances, hallucinations, and paranoia. - Cocaine—In 2019, NSDUH data show an estimated 5.5 million people aged 12 or older were past users of cocaine, including about 778,000 users of crack. The CDC reports that overdose deaths involving have increased by one-third from 2016 to 2017. In the short term, cocaine use can result in increased blood pressure, restlessness, and irritability. In the long term, severe medical complications of cocaine use include heart attacks, seizures, and abdominal pain.

- Kratom—In 2019, NSDUH data show that about 825,000 people had used Kratom in the past month. Kratom is a tropical plant that grows naturally in Southeast Asia with leaves that can have psychotropic effects by affecting opioid brain receptors.

It is currently unregulated and has risk of abuse and dependence. The National Institute on Drug Abuse reports that health effects of Kratom can include nausea, itching, seizures, and hallucinations.

It is currently unregulated and has risk of abuse and dependence. The National Institute on Drug Abuse reports that health effects of Kratom can include nausea, itching, seizures, and hallucinations.

Resources:

- Tips for Teens: Methamphetamine

- Tips for Teens: Cocaine

- National Institute on Drug Abuse

More SAMHSA publications on substance use prevention and treatment.

Last Updated: 01/05/2023

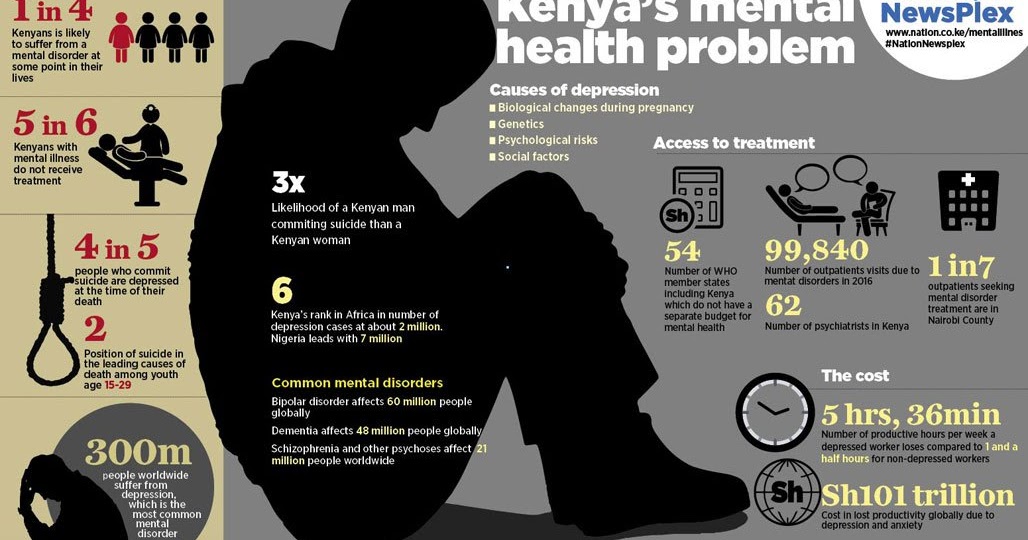

the role of family relations //Psychological newspaper

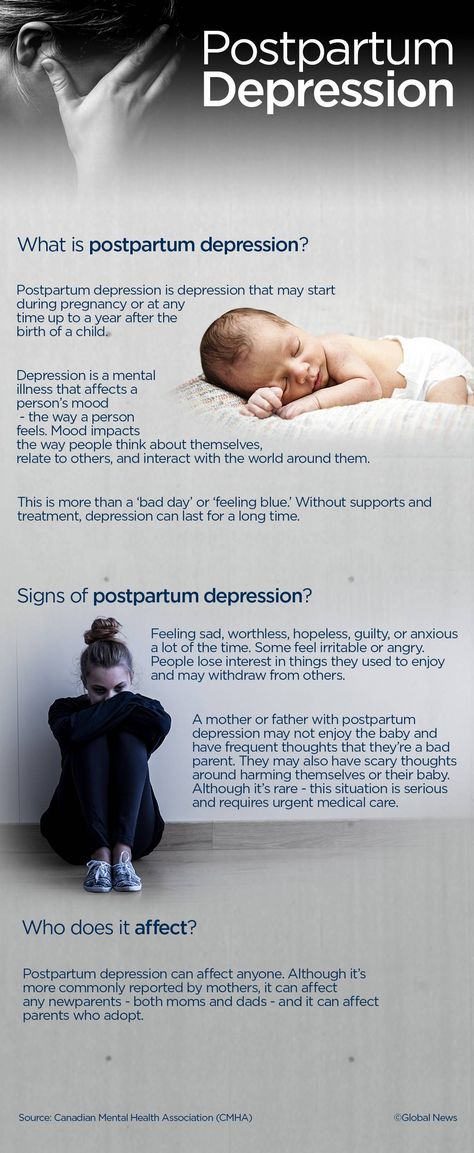

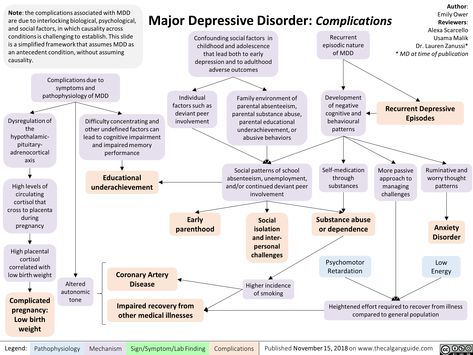

Depression is one of the most common psychopathological affective spectrum disorders during pregnancy and after childbirth [1]. According to the literature, the prevalence of depressive disorders during pregnancy and after childbirth is 7–15%. [2; 3]. However, in most cases, these disorders, for a number of reasons, remain undiagnosed [4].

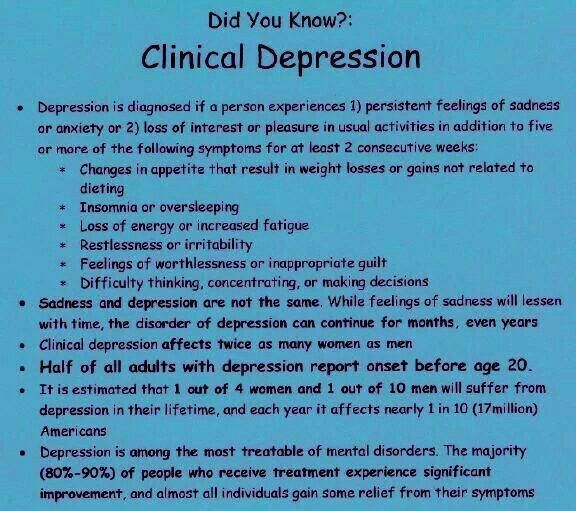

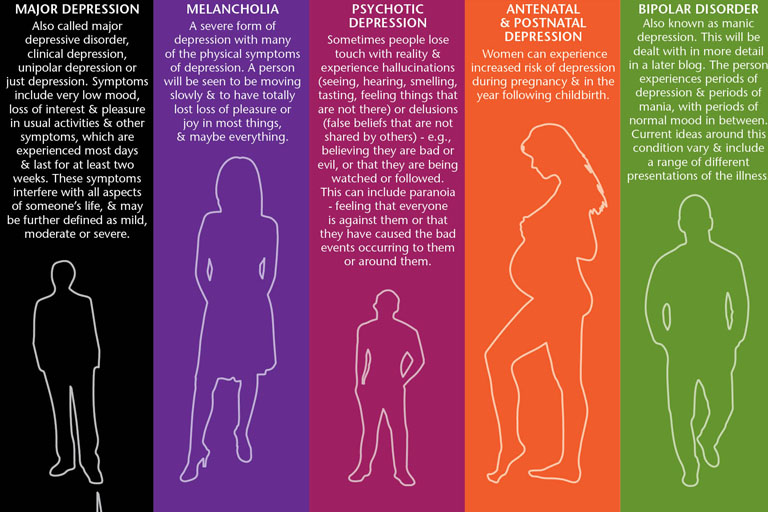

According to the DSM-5 (2013) criteria, antenatal and postnatal depression is considered to be non-psychotic depression that meets the criteria for a major depressive episode that develops during pregnancy or within the first six months after childbirth.

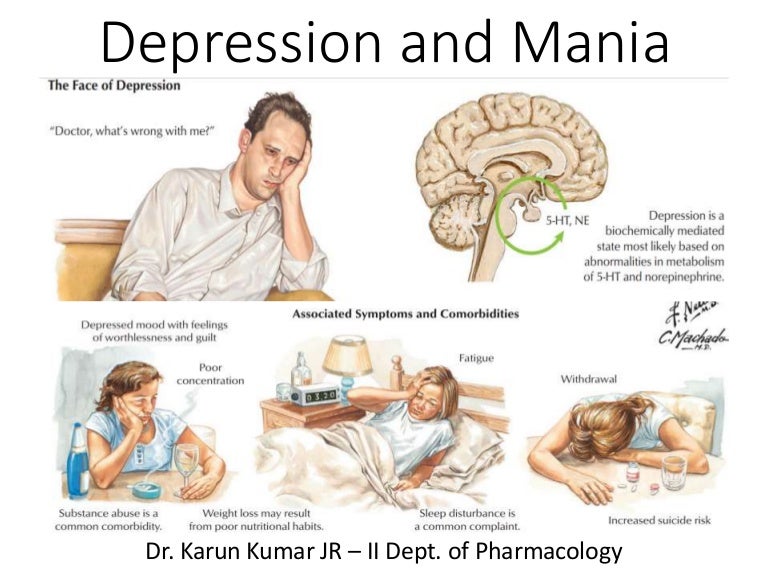

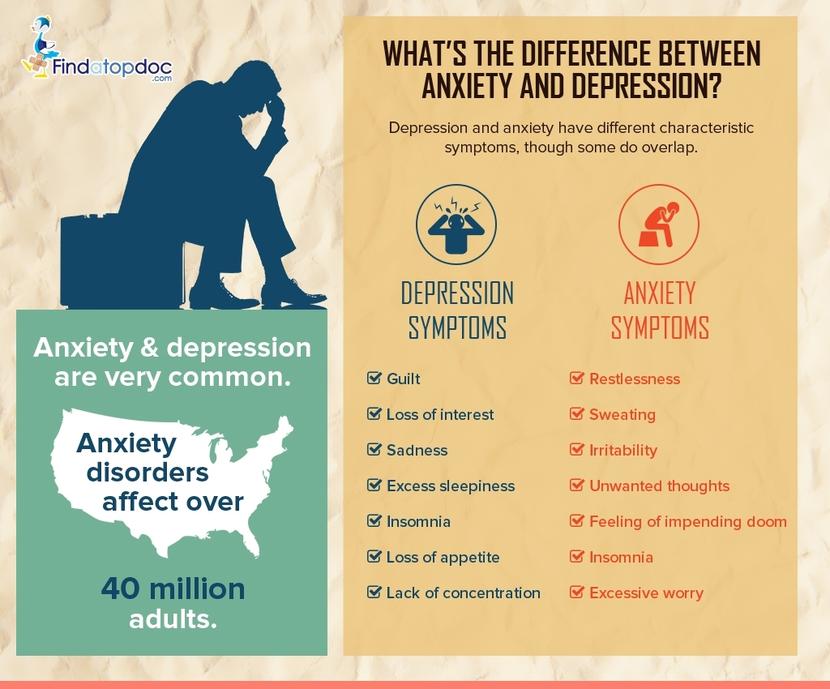

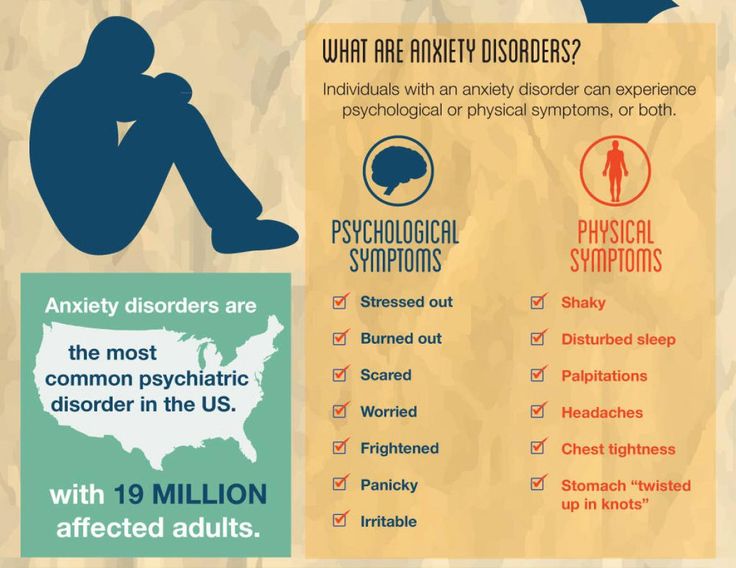

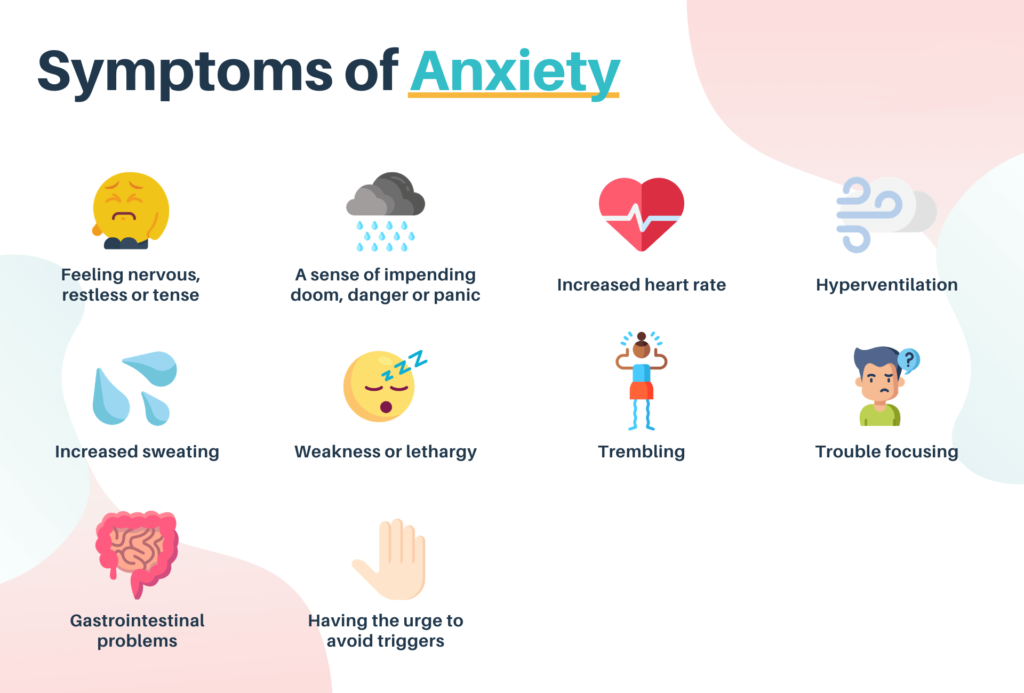

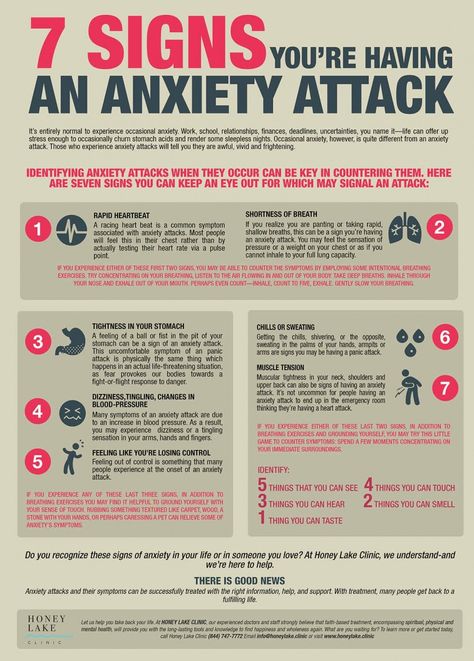

The leading psychopathological disorder in the clinical picture is a depressed mood, lasting more than two weeks, not reaching the degree of pronounced melancholy. Decreased mood is accompanied by a loss of self-confidence, unreasonable reproaches against oneself, and a sense of guilt. Women are often pessimistic about the future, but this attitude is not generalized, but limited only to the zone of certain events (relationship with her husband, upcoming birth, motherhood, child care, etc.). Patients, as a rule, are critical of their condition and are interested in resolving conflict situations. Depressive symptoms manifest themselves in complaints, in the statements of women, without significantly affecting their appearance and behavior. The dynamics of the state is characterized by the fact that a depressed mood does not acquire the properties of persistent depression, but is subject to significant fluctuations. It is important to note that a depressive disorder is often combined with anxiety and asthenic manifestations in the emotional sphere [5–7].

Currently, the point of view is accepted that a complex of biological, psychological and social factors is involved in the initiation of prenatal and postnatal depression [8; 9]. It is known that depression during pregnancy is regarded as a risk factor for the development of postpartum depression. In approximately one third of women, depression that occurs during pregnancy continues after childbirth [10; eleven]. Many studies point to the significant role of psychosocial factors [12–15]. Family relationships, as a rule, are the most important, significant for the individual, this explains their leading role in the formation of mental disorders [16; 17]. Meanwhile, even with a fairly harmonious relationship between the spouses, the family expecting the birth of a child is on the verge of serious changes, its functioning becomes unstable [18].

In this regard, the issue of studying family functioning in women with depressive disorders before and after childbirth is extremely relevant in order to clarify the role of the family relationship factor, namely the relationship with the spouse, in the formation of this pathology.

Purpose of study

To study the features of family functioning of women with depressive disorder during pregnancy and the postpartum period, as well as to conduct a comparative analysis of the data obtained in the two study groups.

Material and methods

On the basis of the Federal State Budgetary Institution "North-Western Federal Medical Research Center", the Department of Biological Therapy of the Mentally Ill of the Federal State Budgetary Institution "Psychoneurological Institute named after V.M. Bekhterev" and the antenatal clinic No. 8 ± 0.53) and 42 postpartum women (age 28.4 ± 0.46). Depressive disorders in women were diagnosed using the clinical and psychopathological method and psychodiagnostic methods: the Tsung scale for self-assessment of depression (T. G. Rybakova, T. I. Balashova, 1988) [1] and the Questionnaire of depressive states (I. G. Bespalko, 1995) [19]. The study of family functioning in groups was carried out using the FACES-III questionnaire “Family Adaptation and Cohesion Scale” [20].

When comparing the results, social characteristics (education, work, marital status, financial situation, etc.) were taken into account, in which the groups did not differ significantly.

Statistical data processing was carried out using the program Statistica version 7.0.

Results of study

The concept of "family adaptation" reflects the ability of the family to adapt to changing conditions of life, i.e. it is a characteristic of how flexible or, conversely, stable relations in the family. The concept of "Family cohesion" defines the type of emotional closeness of family members. Family adaptation and cohesion can be organized at extreme (disjointed and linked, rigid and chaotic) and balanced levels (structural and flexible, divided and connected). Extreme levels are usually viewed as problematic, leading to dysfunction of the family system, while balanced levels determine its success (see table and figure).

In the group of women with depressive disorder during pregnancy, there were 6 types of families (out of 16 possible): linked-chaotic (48%) disconnected-rigid (15%) disconnected-structural (13%) connected-chaotic (20%) connected-rigid (2%) bonded-flexible (2%). Thus, 63% have extreme values for both levels, and belong to the extreme type of functioning; 37% have extreme values for one of the levels, and belong to the average type of functioning.

Thus, 63% have extreme values for both levels, and belong to the extreme type of functioning; 37% have extreme values for one of the levels, and belong to the average type of functioning.

In the group of women with postpartum depression, the following 8 types of families were observed (out of 16 possible): linked-chaotic (20%), disconnected-rigid (16%), disconnected-structural (25%), disconnected-chaotic (15%), divided-chaotic (15%), connected-structural (6%), separated-structural (2%), disconnected-flexible (1%). Thus, 51% of families have extreme values for both levels and belong to the extreme type of functioning; 41% of families have extreme values for one of the levels, and belong to the average type of functioning; 8% belong to the balanced type of functioning.

Analysis of the results shows that the types of functioning of families in both groups do not differ significantly (p ≤ 0.01). Families of pregnant women and postpartum women with depressive disorders are characterized by the dominance of the extreme type of functioning and the absence of a balanced type.

The “family cohesion” parameter: families of pregnant women with depressive disorder 43.15 ± 0.79 are characterized by the “associated” type of family cohesion. And for the families of women with postpartum depression, the most characteristic is the “disunited” type of family cohesion 34.45 ± 2.07.

The parameter "family adaptation": the average values of the level of family adaptation in both groups belong to the "chaotic" (extreme) type (in the group of pregnant women 32.91 ± 1.02, in the group of women after childbirth 31.5 ± 1.85).

Talk

Thus, the data obtained indicate that in the families of women with depression, both in the prenatal and postnatal periods, there is a violation of family relationships. Moreover, the parameter "family cohesion" indicates the dynamics of the deterioration of relations. This reflects the fact that the family system is not able to reorganize to a new level of functioning (to accept new roles of “mother” and “father” for family members) and at the same time maintain harmonious marital relations.

Families of pregnant women with depression, as well as families of women with postpartum depression, are characterized by:

- blurred borders;

- the absence of a clearly defined leader;

- a tendency to make impulsive decisions, subject to the prevailing circumstances at the time of the decision;

- ambiguity of the roles of family members, often passing from one family member to another;

- lack of clearly defined rules;

- the distance of relations between family members, which differ in the autonomy of each of them;

- emotional disunity, insufficient attachment to each other of family members, inconsistency in their behavior;

- a tendency to separate spending free time, a difference in interests, the absence of mutual friends;

- inability to jointly solve everyday problems, lack of desire and skills to support each other.

Doctors often explain the presence of depressive disorders in women both in the prenatal and postnatal periods as “hormonal” changes. However, not all pregnant women with hormonal dysfunctions have emotional disorders, although changes in hormone levels create a favorable background for the development of depressive disorders by increasing emotional reactivity, reducing the stability of the emotional background, mental and physical asthenia. Our observations show that biological factors are involved to a greater extent in the pathogenesis, and psychological - in the etiology of depressive disorders. This can be confirmed by the fact that family psychotherapy reduces psychopathological symptoms [21].

However, not all pregnant women with hormonal dysfunctions have emotional disorders, although changes in hormone levels create a favorable background for the development of depressive disorders by increasing emotional reactivity, reducing the stability of the emotional background, mental and physical asthenia. Our observations show that biological factors are involved to a greater extent in the pathogenesis, and psychological - in the etiology of depressive disorders. This can be confirmed by the fact that family psychotherapy reduces psychopathological symptoms [21].

Our results support this assumption. In the families of pregnant women with depressive disorder and women with postpartum depression, disharmony of marital relations, violations of the family structure were revealed. This makes it possible to consider such families as dysfunctional, which is both a cause and a consequence of the development of depressive disorders in women of these families.

Attention should be paid to the extremely important mental state of the mother in the perinatal period for the development of the child. With depressive disorders, the mother is not able to establish a full and adequate interaction with the prenate and the baby. In the prenatal period, a pregnant woman can ignore the fact of pregnancy and continue to lead a former lifestyle, use psychoactive substances (alcohol, drugs, nicotine) and drugs, do not follow the recommendations of doctors or, conversely, against the background of somatization of anxiety, often visit specialists, exaggerate bodily sensations and etc. In such cases, the pregnant woman often lacks or insufficiently formed the psychological “image of the child” and “herself as a mother”, which disrupts the formation of the “mother-child” dyad in the prenatal period.

With depressive disorders, the mother is not able to establish a full and adequate interaction with the prenate and the baby. In the prenatal period, a pregnant woman can ignore the fact of pregnancy and continue to lead a former lifestyle, use psychoactive substances (alcohol, drugs, nicotine) and drugs, do not follow the recommendations of doctors or, conversely, against the background of somatization of anxiety, often visit specialists, exaggerate bodily sensations and etc. In such cases, the pregnant woman often lacks or insufficiently formed the psychological “image of the child” and “herself as a mother”, which disrupts the formation of the “mother-child” dyad in the prenatal period.

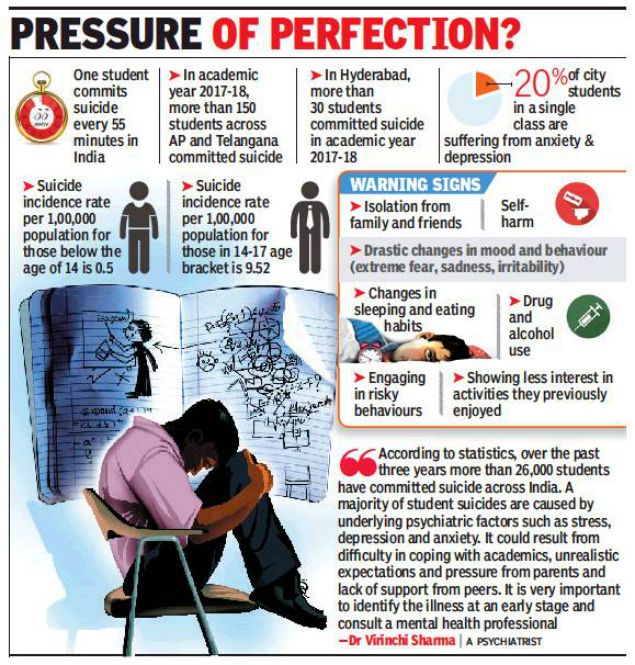

Children whose mothers experienced a depressive disorder during pregnancy or after childbirth differ from healthy children in that they cry more often, wake up, worry, they may have various psychosomatic reactions. In infancy, they have an increased level of cortisol, and cortisol continues to be produced in excess at an older age. Thus, their body is in a state of “toxic stress” [22–24].

Thus, their body is in a state of “toxic stress” [22–24].

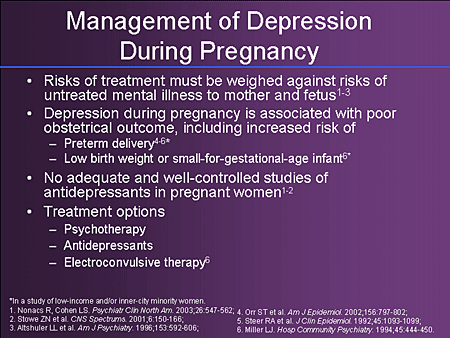

The main methods of treatment of depressive disorders include psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. The general rule is the use of medicines only if the risk of complications for the pregnant woman (woman after childbirth) or the fetus (child) in case of refusal to use medicines exceeds the risk of their side effects. In this regard, psychotherapeutic methods for the treatment of depressive disorders in women in the perinatal period should be the methods of first choice. It is the family approach in psychotherapy that represents the best treatment option, since it is pathogenetic and allows achieving a stable therapeutic effect [25].

Conclusions

1. It is necessary to carry out psychological diagnostics (screening) in pregnant women and women after childbirth using specially directed scales to detect depressive disorders.

2. Psychosocial factors contribute to the formation of a system of "circular dependencies" and, in turn, support a depressive mood background. Psychocorrective and psychotherapeutic measures should be aimed at breaking the formed circular dependencies.

Psychocorrective and psychotherapeutic measures should be aimed at breaking the formed circular dependencies.

3. For the implementation of psychological prevention of depression during pregnancy and postpartum depression and when planning measures for psychological correction and psychotherapy, it is necessary to take into account not only the clinical features of the manifestation of depression, but also the context of family and social functioning of women during pregnancy and after childbirth.

4. When choosing tactics for the treatment of depression in pregnant women and in women after childbirth, psychotherapeutic methods and psychocorrective influences should be preferred. Psychopharmacotherapy should be used only for vital indications.

Literature

- Balashova T. N., Rybakova T. G. Clinical and psychological characteristics and diagnosis of affective disorders in alcoholism: Methodological recommendations of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation.

L.: NIPNI im. V. M. Bekhtereva, 1988. S. 19–22.

L.: NIPNI im. V. M. Bekhtereva, 1988. S. 19–22. - Dougherty L. R. et al. Maternal psychopathology and early child temperament predict young children's salivary cortisol 3 years later // Abnorm Child. psycho. 2013. Vol. 41, No. 4. P. 531–542.

- Shulman H. B., Gilbert B. C., Lansky A. The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): current methods and evaluation of 2001 response rates // Public Health Rep. 2006 Vol. 121. R. 74–83.

- Smulevich A. B. Depression in somatic and mental diseases. M.: Medical Information Agency, 2003. 432 p.

- Kolesnikov I. A. Depressive disorders during pregnancy // Psychotherapy. 2008. No. 5. S. 8.

- Krasnov VN Disorders of the affective spectrum. M: Practical medicine, 2011. 432 p.

- Nuller Yu. L., Mikhalenko IN Affective psychoses. L.: Medicine, 1988. 264 p.

- Lee A. M. et al. Prevalence, course, and risk factors for antenatal anxiety and depression // Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Vol.

110, No. 5. P. 1102–1112.

110, No. 5. P. 1102–1112. - World Health Organization. Maternal mental health. 2015. URL: http://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/maternal_mental_health/en/ (Accessed 02/01/2015).

- Eidemiller EG, Yustickis V. Psychology and psychotherapy of the family. 4th ed. St. Petersburg: Piter, 2008. 672 p.

- Bennett H. A. et al. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review // Obstet. Gynecol. 2004 Vol. 103, No. 4. P. 698–709.

- Belyaeva E. N., Vasserman L. I., Mazo G. E. Clinical and psychological diagnostics and assessment of the factor of family relations in patients with postpartum depression // Sib. psychol. magazine 2011. No. 42. P. 6–13.

- Belyaeva E. N., Wasserman L. I., Zazerskaya I. E. Postpartum depression: clinical and psychological diagnosis and assessment of the role of the psychosocial factor // Bul. FTsSKE them. V. A. Almazova. 2011. No. 6. S. 29–32.

- Dobryakov I. V., Kolesnikov I. A. Perinatal psychotherapy of the family // Mental health.

2010. V. 8, No. 7. S. 24–27.

2010. V. 8, No. 7. S. 24–27. - Beck C. T. A meta-analysis of predictors of postpartum depression // Nurs. Res. 1996 Vol. 45, No. 5. P. 297–303.

- Wasserman L.I., Ababkov V.A., Trifonova E.A. Coping with stress: theory and psychodiagnostics: Study method. allowance. St. Petersburg: Rech, 2010. 192 p.

- Eidemiller E. G., Dobryakov I. V., Nikolskaya I. M. Family diagnosis and family psychotherapy. SPb., 2006. 352 p.

- Dobryakov I.V., Kolesnikov I.A. Depression during pregnancy // Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S. S. Korsakov. 2008. V. 108, No. 7. S. 91–97.

- Bespalko I. G. Questionnaire for the psychological diagnosis of depressive states: Method. NIPNI recommendations. V. M. Bekhtereva. SPb., 1995. 23 p.

- Shamanina M. V. Depressive states in the postpartum period: Abstract of the thesis. dis. … cand. honey. Sciences. SPb., 2014. 24 p.

- Dobryakov IV Perinatal psychotherapy of the family // Vestn. new medical technologies.

2009. V. 16, No. 4. S. 191–192. 315

2009. V. 16, No. 4. S. 191–192. 315 - Cooklin A. R., Rowe H. J., Fisher J. R. Employee entitlements during pregnancy and maternal psychological well-being // Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007 Vol. 47, No. 6. P. 483–490.

- Poggi D. E., Sandman C. A. Prenatal psychobiological predictors of anxiety risk in preadolescent children // Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012. Vol. 37, No. 8. P. 1224-1233.

- Shonkoff J. P., Garner A. S. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress // Pediatrics. 2012. Vol. 129, No. 1. P. 232–246.

- Kolesnikov I. A. Neurotic depressive disorders and family functioning in pregnant women: Abstract of the thesis. dis. … cand. honey. Sciences. St. Petersburg, 2010. 26 p.

Source: Kolesnikov I.A., Belyaeva E.N., Dobryakov I.V., Zazerskaya I.E., Wasserman L.I. Depressive disorders in women during pregnancy and after childbirth: the role of family relations // Proceedings of the All-Russian scientific and practical conference with international participation "Modern problems of clinical psychology and personality psychology". - Novosibirsk: CPI NSU, 2017. - 318 p.

- Novosibirsk: CPI NSU, 2017. - 318 p.

Postpartum depression, tragedy and loss - Extempore

Know, sympathize, effectively help

Both in traditional cultures and in modern society, the first days after the birth of a child are considered a time of “pure” happiness. The image of a happy mother with a newborn is not only a win-win stamp in the advertising industry, but also the most common "style icon" for women who are expecting a baby. But the postpartum period also has a dark side: in the first days, weeks, months, a woman is vulnerable and prone to the development of psycho-emotional and mental disorders

. But gone are the days when the prerogative of the doctor was exclusively medical care. Now the close relationship between the psyche and physical health is generally recognized; modern treatment protocols and recommendations in various fields of medicine include sections aimed at optimizing the psycho-emotional state of patients. An integral approach is important in obstetrics and gynecology as in no other medical specialty. When providing medical assistance to a woman of any age, at any stage of her life path and reproductive history, it is appropriate to remember the words of an ancient thinker: "You cannot heal the body without healing the soul." In this article, we look at the causes, symptoms, and treatments for postpartum depression, presenting common psychological reactions of parents to the birth of a seriously ill child, a child with a birth defect or stillbirth, or to the death of a newborn child. We will discuss how to properly help parents in cases where the beginning of motherhood, by the will of fate, turned out to be not cloudless.

An integral approach is important in obstetrics and gynecology as in no other medical specialty. When providing medical assistance to a woman of any age, at any stage of her life path and reproductive history, it is appropriate to remember the words of an ancient thinker: "You cannot heal the body without healing the soul." In this article, we look at the causes, symptoms, and treatments for postpartum depression, presenting common psychological reactions of parents to the birth of a seriously ill child, a child with a birth defect or stillbirth, or to the death of a newborn child. We will discuss how to properly help parents in cases where the beginning of motherhood, by the will of fate, turned out to be not cloudless.

Continuum of postpartum mental disorders

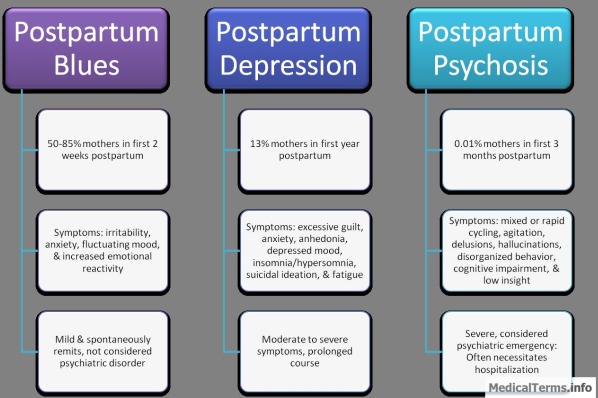

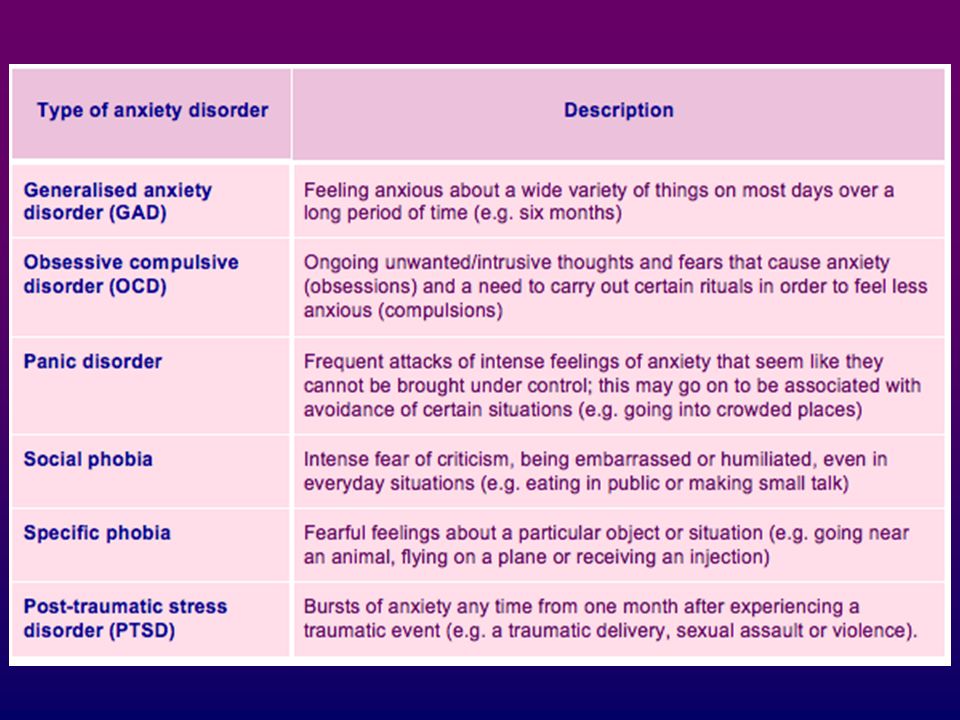

According to modern concepts, mental disorders in women associated with childbirth can be roughly divided into three main categories according to severity: the so-called "postpartum depression", non-psychotic postpartum depression and postpartum psychoses.

"Postpartum spleen", which is characterized by mild symptoms of low mood, tearfulness without any apparent reason, anxious anxiety, hypersensitivity, is experienced, according to various sources, from 26% to 85% of puerperas. Such blues usually reach their peak on the fourth or fifth day after childbirth, can last from several hours to several days, and normally disappear by the tenth day of the postpartum period.

10-15% of women develop mild to moderate postpartum non-psychotic depressive disorder, and 1-2% develop postpartum psychosis, a mood disorder accompanied by signs such as loss of contact with reality, hallucinations, severe thinking disorder and abnormal behavior . Postpartum depression deserves special attention because of its prevalence, and also because it occurs at a critical time in the life of a mother, her baby, and family. There is evidence that risk factors for postpartum depression (PDP) do not differ from risk factors for non-postpartum depression. This is the presence of psychopathology in history and psychological disorders during pregnancy, insufficient social support, poor relationships in marriage, recent traumatic events in life. In addition, cohort and case-control studies have identified the following risk factors for PPD: unintended pregnancy, unemployment, failure to breastfeed, maternal antenatal thyroid dysfunction, history of infertility, paternal depression, and having two or more children. However, an insignificant relationship was found between the occurrence of PPD and complications during childbirth, mistreatment of a woman in the past, low family income, and low professional status.

This is the presence of psychopathology in history and psychological disorders during pregnancy, insufficient social support, poor relationships in marriage, recent traumatic events in life. In addition, cohort and case-control studies have identified the following risk factors for PPD: unintended pregnancy, unemployment, failure to breastfeed, maternal antenatal thyroid dysfunction, history of infertility, paternal depression, and having two or more children. However, an insignificant relationship was found between the occurrence of PPD and complications during childbirth, mistreatment of a woman in the past, low family income, and low professional status.

In order to successfully overcome postpartum depression, a woman needs the support of her friends, relatives, and medical and social workers. However, the difficulty in getting help is that most women and their families do not realize that support and treatment are needed. That is why the main role in identifying cases of PRD falls on medical workers - both obstetrician-gynecologists of antenatal clinics and maternity hospitals, and the first link - family medicine doctors and pediatricians.

For example, the antenatal care provider of a pregnant woman should regularly monitor psychosocial and biological risk factors for PPD and PPD (see above) and provide pregnant women and their partners with information about the nature of postpartum mood disorders. Some of these tasks can be performed by the "School of Motherhood"; promising is the cooperation of an obstetrician-gynecologist and a prenatal psychologist.

PPD often goes unrecognized because many primary care physicians tend to view it as a temporary and natural response to the stress of having a baby, especially for nulliparous women. Many cases have been described where depression builds up over several months, and treatment is delayed until there is an indication for emergency hospitalization. The manifestation of emotional disorders in the first days after childbirth may be noticed by an obstetrician-gynecologist, and in the following weeks and months - by a pediatrician or nurse who patronizes the child, or by a family doctor.

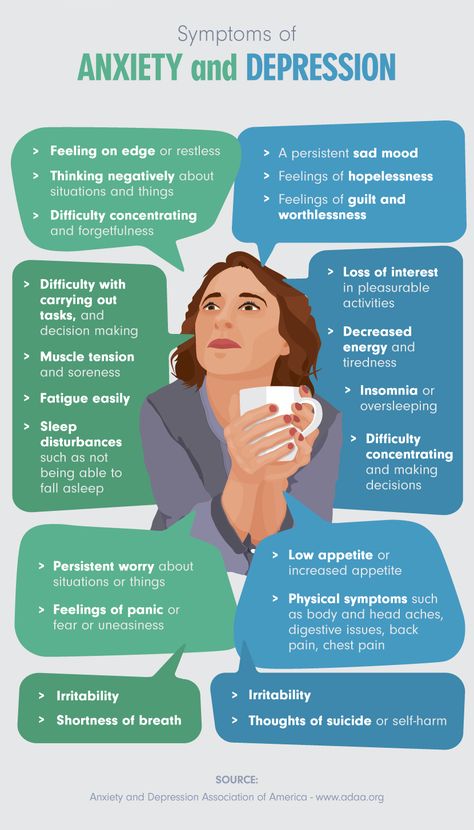

For the timely diagnosis of postpartum mental disorders, doctors should pay attention not only to medical aspects, but also ask questions about the condition and mood of the mother, about the difficulties she faces. It is important to create a trusting atmosphere conducive to the patient's frankness. A list of symptoms will help differentiate normal, transient emotional changes from postpartum depression and psychosis.

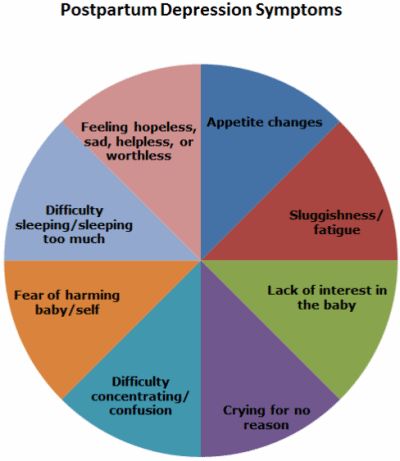

Symptoms of postpartum depression:

- Loss of interest or pleasure in life.

- Lack of energy or motivation, even for routine activities.

- Increased tearfulness, tearfulness.

- Feeling of anxiety, irritation, anxiety.

- Feeling of worthlessness, hopelessness, exaggerated sense of guilt; feeling that life is meaningless, fear for oneself, suicidal thoughts.

- Vegetative symptoms: loss of libido, appetite, sleep disturbance (difficulty falling asleep, restless sleep, increased sleep duration).

- Unexplained weight loss or gain.

- Psychosomatic symptoms, most often headaches.

- Symptoms associated with the child: fear for the child, disgust for the child, desire to harm him.

Identification of PPD requires not only knowledge, but also life wisdom from the doctor. So, when a doctor is trying to determine whether the presence of a symptom is a sign of depression or a normal postpartum reaction, he should take into account all the circumstances. For example, a woman's emotional exhaustion and her irritability may be normal in the presence of restless twins of two weeks old, but not when the child is four months old, he develops correctly, gains weight well and sleeps peacefully at night. Another example: some absent-mindedness quite fits into the picture of the “norm” in the first days of the postpartum period, but the situation when a woman in a conversation often loses her train of thought or makes considerable efforts to make even a minor decision is certainly a cause for concern.

Questions to help health workers identify postpartum depression:

- How are you feeling lately?

- How do you assess your condition? Do you have enough energy for daily activities? Is there severe, unusual fatigue?

- Do you enjoy activities that normally bring you joy?

- Do you find it easy to focus your attention (for example, on talking, reading, or watching TV)?

Principles of treatment for PPD

Untreated postpartum depression can be prolonged and have a detrimental effect not only on the patient's psyche, but also on the relationship between mother and child, as well as on the cognitive and emotional development of the baby. Therefore, postpartum depression and postpartum psychosis should be treated in the same way as outside pregnancy, but always taking into account the peculiarities associated with taking medications while breastfeeding. Consider the main methods of treatment of PRD.

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapy is the subject of much debate, with limited evidence. The results of a double-blind, randomized controlled trial showed that transdermal estrogen (with a cyclic progestogen) was more effective than placebo in the treatment of moderate to severe postpartum depression. However, its use may be limited due to concerns about side effects, especially the development of endometrial hyperplasia and thrombosis. However, there is no evidence of the effectiveness of natural progesterone or synthetic progestogens in the treatment of PPD.

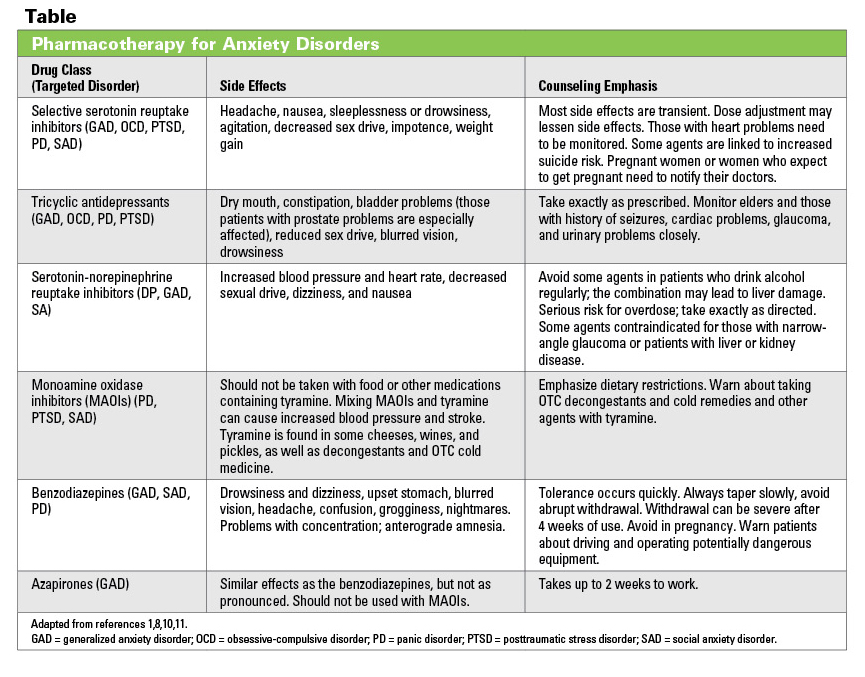

Antidepressants

A randomized controlled trial of antidepressant therapy for postpartum depression conducted at a community health facility in Manchester showed a beneficial effect of fluoxetine in combination with at least one session of modified cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in women with mild postpartum depression. Evidence from a case-control study in the United States suggests that both selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are effective in treating postpartum depression. The results of a small case series study suggest that SSRIs are no less effective in patients with postpartum depression than in other groups of patients.

The results of a small case series study suggest that SSRIs are no less effective in patients with postpartum depression than in other groups of patients.

Physiotherapy and exercise

There are no data on the use of electroshock therapy (ECT) for postpartum depression. Although there is strong evidence supporting the role of physical activity in reducing depression in the general population, the role of exercise in relation to postpartum depression has not been well studied.

Postpartum depression counseling

The application of this method is within the competence of a medical psychologist or psychotherapist. However, the acquisition of non-directive counseling skills (supportive listening without giving opinions or recommendations) by obstetrician-gynecologists and pediatricians and the application of these methods in practice confirmed the effectiveness in reducing the incidence of PPD compared with generally accepted practice of care.

Non-directive counseling advice for a mother:

- Take care of your baby while putting aside all other concerns.

- Create an environment at home in which the child will be the center of attention of the whole family.

- Touch your baby more often, hold him in your arms.

- Think of a child.

- Go out for a walk every day.

- Maintain physical activity.

- Establish a healthy nutritious diet.

- Watch your appearance.

- Keep a personal diary.

- Discuss your emotional difficulties with family members.

- Remember that if the above measures do not help, you should contact a medical psychologist or psychotherapist.

Practical Family Counseling

Today, the practice of individual or group consultations on the issues of upbringing and the formation of parenting skills, consultations on the quality of the relationship between mother and child has gained wide popularity. An additional benefit of such activities is the reduction of symptoms of depression and a positive effect on the overall health of the woman or couple. For example, several studies clearly show that teaching mothers who have developed postpartum depression how to communicate with their children has a positive effect on the bond between mother and child. A small, randomized controlled trial showed that attending baby massage sessions had a significant positive impact on both mother-child interactions and the reduction of maternal symptoms of depression.

An additional benefit of such activities is the reduction of symptoms of depression and a positive effect on the overall health of the woman or couple. For example, several studies clearly show that teaching mothers who have developed postpartum depression how to communicate with their children has a positive effect on the bond between mother and child. A small, randomized controlled trial showed that attending baby massage sessions had a significant positive impact on both mother-child interactions and the reduction of maternal symptoms of depression.

There is currently no specific treatment for postpartum psychosis. Since this disorder is affective in nature, therapies commonly used to treat affective psychoses are suitable for its treatment.

Advanced problem

All parents hope for a healthy child, and if these hopes are not met (the newborn is premature, or seriously ill, or has a birth defect/malformation, or the child is stillborn or dies shortly after birth), this can be a huge shock.

In the first stages of reaction to this unexpected situation, parents often experience emotional shock.

This is usually followed by a stage of acceptance, and then humility, when the parents gradually adapt to what happened and learn to cope with the situation. Throughout this time, the support of medical professionals and psychologists plays a very important role. From the outset, healthcare professionals should follow these guidelines:

- Establish and maintain close contact with parents as early as possible.

- Support parents and provide them with reliable information about the causes of illness or a birth defect/malformation.

- Be very careful about the information parents receive (any premature diagnosis by a health worker thoughtlessly, or even a casual remark about a child's prognosis, can cause parents to panic).

- Encourage the participation of both parents in all discussions regarding the child's condition and future prognosis - this will allow parents to improve relations between themselves and avoid their disunity, misunderstanding or misinterpretation of the information you provide.

By the way, according to some data, fathers recover faster after a shock than mothers.

By the way, according to some data, fathers recover faster after a shock than mothers.

In addition to feelings of grief and disappointment, parents may have difficulty seeing the handicap (or signs of prematurity) of their baby.

This does not mean that the separation of mother and baby should be encouraged - on the contrary, it is very important to establish and maintain their close contact.

Reminder for health workers

Help for parents of a child born with a serious illness or birth defect

- Allow parents to contact their child and encourage such contact.

- Be prepared to answer questions from parents.

- Be prepared to repeat information or answer the same questions over and over.

- Be prepared for outbursts of anger and frustration directed at healthcare workers.

- Encourage the mother to express milk for her newborn, talk about the importance of breast milk for the baby.

- Emphasize the importance of the mother's involvement in the care of the baby.

- Promise that you, as a health worker, will always be ready to help the mother adjust to the needs of the "special" child and arrange care for him. Say more often: "I'll be there, I'll help."

- If it is not possible to involve the mother in care, give the parents a photograph of the sick child.

The joint motto of parents and health workers should be the words: "Acceptance and overcoming."

Parents' reaction to the death of a child

Parents of a deceased child are often overcome with intolerance and anger, and even in hopeless cases they may blame medical professionals for what happened.

The main signs of parental reaction to the death of a child are the following:

- Experience of different stages of grief.

- Strong desire for answers or explanations for the cause of death.

- Unwillingness to contact with medical workers.

- Visual or auditory hallucinations (eg, the mother may hear the crying of a dead child).

- Negative feelings towards other children.

- Despair at the onset of lactation.

- Feeling of guilt, own inferiority.

- Deterioration of relations between parents and other family members.

Obviously, families in which a child has died need the help of specialists. Health care providers can do a lot to help these families deal with grief.

If the child has died…

- Allow parents to see the deceased child (for example, let them hold the child disconnected from life support equipment).

- Invite parents to keep some things that will remind them of their child.

- Make a list of institutions to which you can refer your family.

- Provide the mother with adequate postpartum care, but discharge her from the hospital if there are no medical contraindications.

- If discharge is not possible, allow the mother's relatives to stay with her in the room for the first night.

- Provide appropriate counseling support throughout the mother's hospital stay; if possible, involve a medical psychologist or psychotherapist.

- Inform other staff caring for the woman (to avoid inappropriate questions).

- Convince parents of the need for an autopsy; inform and explain to them the results of the autopsy.

- Involve the parents in organizing the funeral and support them if possible.

- Send information about what happened to the antenatal clinic, focus on the mother's condition.

- Do not talk about a new pregnancy (this prohibition remains until enough time has passed for the parents to mourn and come to terms with the loss of the child).

Support is the most important part of helping a family cope with a loss, at the beginning of the process of returning to normal life. It is important for the health worker to take the time to talk to and listen to the parents. Sometimes the need to maintain contact with the doctor who observed the deceased child remains with the parents for many years - in this way they seem to maintain contact with the lost baby.

It is important for the health worker to take the time to talk to and listen to the parents. Sometimes the need to maintain contact with the doctor who observed the deceased child remains with the parents for many years - in this way they seem to maintain contact with the lost baby.

Let's summarize what was said in this article. 10-15% of all women experience postpartum depression. A woman who has recently given birth needs the help of everyone around her. It is important for healthcare professionals to diagnose postpartum depression early in order to provide the patient with the necessary individualized support and treatment. Continuous psychological support for parents of children born with a serious illness, malformation or death is just as important as quality medical care.

Complaint and Lawsuit Prevention: 10 Do's for Physicians in Difficult Situations

To prevent complaints and civil lawsuits, healthcare professionals are encouraged to use the 10-Never rule.