6 months premature baby development

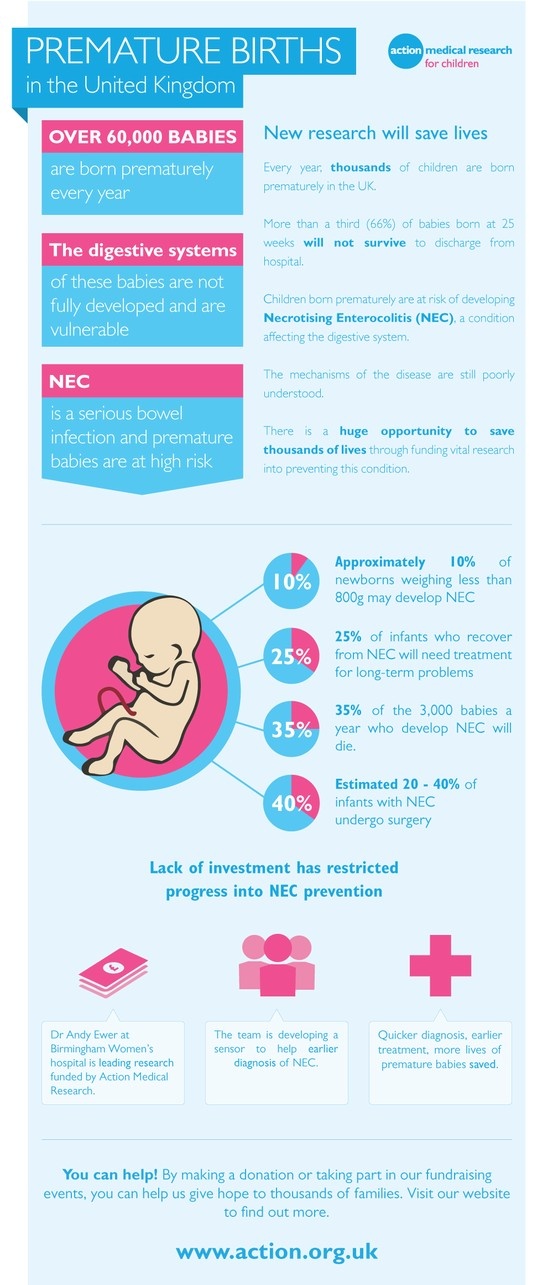

Your Preemie's Growth & Developmental Milestones

Was your baby born more than 3 weeks early? Read on for information from the American Academy of Pediatrics about developmental milestones for your preterm baby.

Keep in mind that babies develop at their own speed and in their own way. However, parents of preemies will need to adjust their baby's age to get a true sense of where their baby should be in his development.

Your Child's Progress

You know your child better than anyone else. Even with an adjusted age, you will want to see him move forward in his development. For example, your child should progress from pulling himself up, to standing, and then to walking. When you watch him carefully, you will see ways he is growing well. You will also know whether he needs more help.

Remember to take your child to his recommended well-child (health supervision) visits. At each visit, your child's doctor will check his progress and ask you about the ways you see your child growing. See the next section, Developmental Milestones.

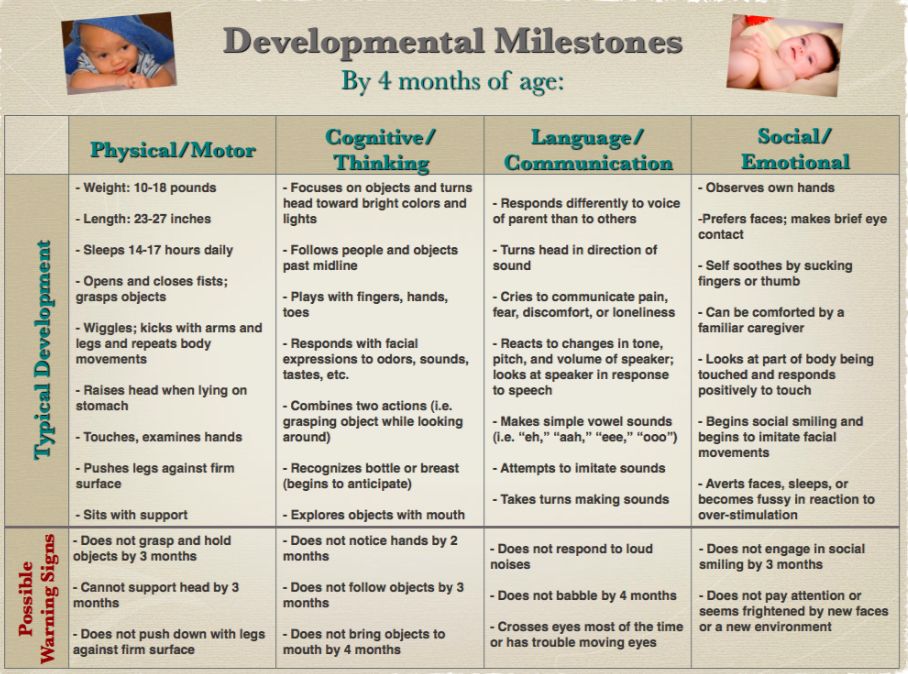

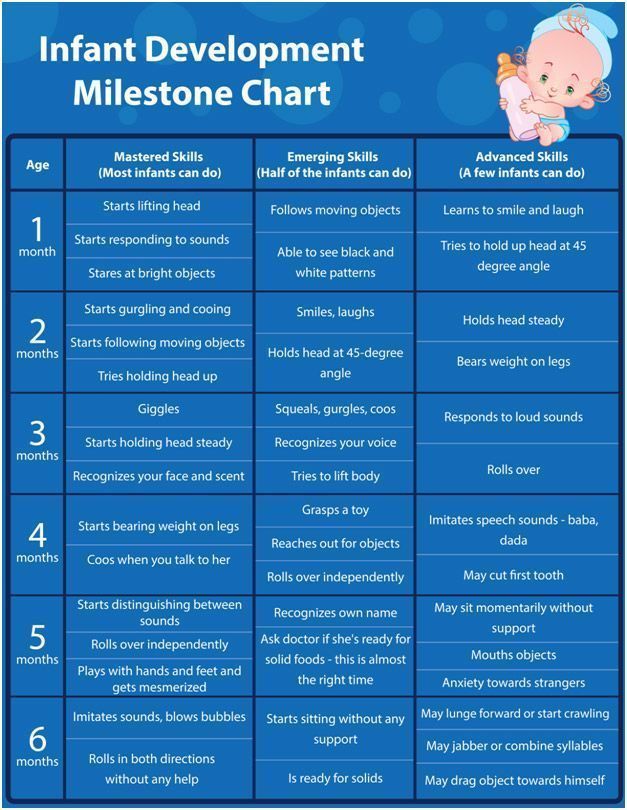

Developmental Milestones

Here is information about how babies and young children typically develop. Examples of developmental milestones for ages 1 month to 6 years are listed. The developmental milestones are listed by month or year first because well-child visits are organized this way.

For a preterm baby, it is important to use the baby's adjusted age when tracking development until 2 years of age so that his growth and progress take into account that he was born early.

What is your child's adjusted age?______________________. See milestone for the adjusted age in the next section.

NOTE: Ask your baby's doctor about Early Intervention (EI)—extra care some babies and children receive to help them develop.

At 1 Month (4 Weeks)

Social

Looks at parent; follows parent with eyes

Has self-comforting behaviors, such as bringing hands to mouth

Starts to become fussy when bored; calms when picked up or spoken to

Looks briefly at objects

Language

Makes brief, short vowel sounds

Alerts to unexpected sound; quiets or turns to parent's voice

Shows signs of sensitivity to environment (such as excessive crying, tremors, or excessive startles) or need for extra support to handle activities of daily living

Has different types of cries for hunger and tiredness

Motor

Moves both arms and both legs together

Holds chin up when on tummy

Opens fingers slightly when at rest

At 2 Months (8 Weeks)

Social

Language

- Makes short cooing sounds

Motor

Opens and shuts hands

Briefly brings hands together

Lifts head and chest when lying on tummy

Keeps head steady when held in a sitting position

At 4 Months (16 Weeks)

Social

Language

Motor

Supports self on elbows and wrists when on tummy

Rolls over from tummy to back

Keeps hands unfisted

Plays with fingers near middle of body

Grasps objects

At 6 Months (24 Weeks)

Social

Language

- Babbles, making sounds such as “da," “ga," “ba," or “ka"

Motor

Sits briefly without support

Rolls over from back to tummy

Passes a toy from one hand to another

Rakes small objects with 4 fingers to pick them up

Bangs small objects on surface

At 9 Months (36 Weeks)

Social

Uses basic gestures (such as holding out arms to be picked up or waving bye-bye)

Looks for dropped objects

Plays games such as peekaboo and pat-a-cake

Turns consistently when name called

Language

Says “Dada" or “Mama" nonspecifically

Looks around when hearing things such as “Where's your bottle?" or “Where's your blanket?"

Copies sounds that parent or caregiver makes

Motor

Sits well without support

Pulls to stand

Moves easily between sitting and lying

Crawls on hands and knees

Picks up food to eat

Picks up small objects with 3 fingers and thumb

Lets go of objects on purpose

Bangs objects together

At 12 Months (48 Weeks, or 1 Year)

Social

Language

Uses “Dada" or “Mama" specifically

Uses 1 word other than Mama, Dada, or a personal name

Follows directions with gestures, such as motioning and saying, “Give me (object).

"

"

Motor

Takes first steps

Stands without support

Drops an object into a cup

Picks up small object with 1 finger and thumb

Picks up food to eat

At 15 Months (60 Weeks, or 1 ¼ Years)

Social

Imitates scribbling

Drinks from cup with little spilling

Points to ask something or get help

Looks around after hearing things such as “Where's your ball?" or “Where's your blanket?"

Language

Uses 3 words other than names

Speaks in what sounds like an unknown language

Follows directions that do not include a gesture

Motor

Squats to pick up object

Crawls up a few steps

Runs

Makes marks with crayon

Drops object into and takes it out of a cup

At 18 Months (72 Weeks, or 1½ Years)

Social

Engages with others for play

Helps dress and undress self

Points to pictures in book or to object of interest to draw parent's attention to it

Turns to look at adult if something new happens

Begins to scoop with a spoon

Uses words to ask for help

Language

Motor

Walks up steps with 2 feet per step when hand is held

Sits in a small chair

Carries toy when walking

Scribbles spontaneously

Throws a small ball a few feet while standing

At 24 Months (2 Years)

Social

Plays alongside other children

Takes off some clothing

Scoops well with a spoon

Language

Uses at least 50 words

Combines 2 words into short phrase or sentence

Follows 2-part instructions

Names at least 5 body parts

Speaks in words that are about 50% understandable by strangers

Motor

Kicks a ball

Jumps off the ground with 2 feet

Runs with coordination

Climbs up a ladder at a playground

Stacks objects

Turns book pages

Uses hands to turn objects such as knobs, toys, or lids

Draws lines

At 2½ Years

Social

Urinates in a potty or toilet

Spears food with fork

Washes and dries hands

Increasingly engages in imaginary play

Tries to get parents to watch by saying, “Look at me!"

Language

- Uses pronouns correctly

Motor

Walks up steps, alternating feet

Runs well without falling

Copies a vertical line

Grasps crayon with thumb and fingers instead of fist

Catches large balls

At 3 Years

Social

Enters bathroom and urinates by herself

Puts on coat, jacket, or shirt without help

Eats without help

Engages in imaginative play

Plays well with others and shares

Language

Uses 3-word sentences

Speaks in words that are understandable to strangers 75% of the time

Tells you a story from a book or TV

Compares things using words such as bigger or shorter

Understands prepositions such as on or under

Motor

Pedals a tricycle

Climbs on and off couch or chair

Jumps forward

Draws a single circle

Draws a person with head and 1 other body part

Cuts with child scissors

At 4 Years

Social

Enters bathroom and has bowel movement by himself

Brushes teeth

Dresses and undresses without much help

Engages in well-developed imaginative play

Language

Answers questions such as “What do you do when you are cold?" or “What do you do when you are you sleepy?"

Uses 4-word sentences

Speaks in words that are 100% understandable to strangers

Draws recognizable pictures

Follows simple rules when playing a board or card game

Tells parent a story from a book

Motor

Hops on one foot

Climbs stairs while alternating feet without help

Draws a person with at least 3 body parts

Draws a simple cross

Unbuttons and buttons medium-sized buttons

Grasps pencil with thumb and fingers instead of fist

At 5 and 6 Years

Social

Language

Motor

Balances on one foot

Hops and skips

Is able to tie a knot

Draws a person with at least 6 body parts

Prints some letters and numbers

Can copy a square and a triangle

At School Age

Ongoing Issues Your Child May Face

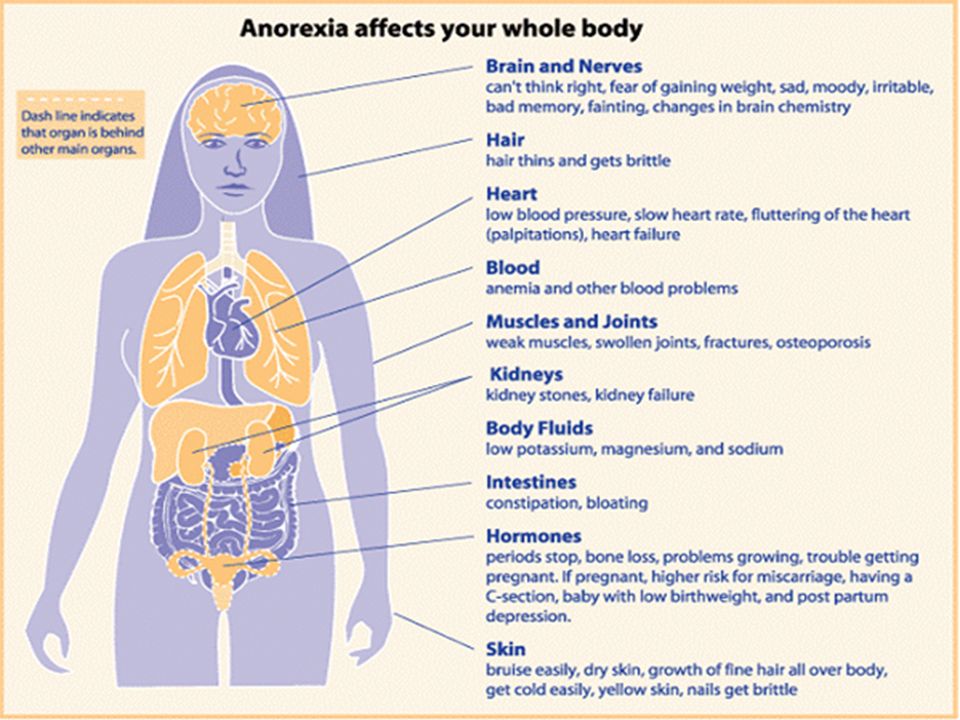

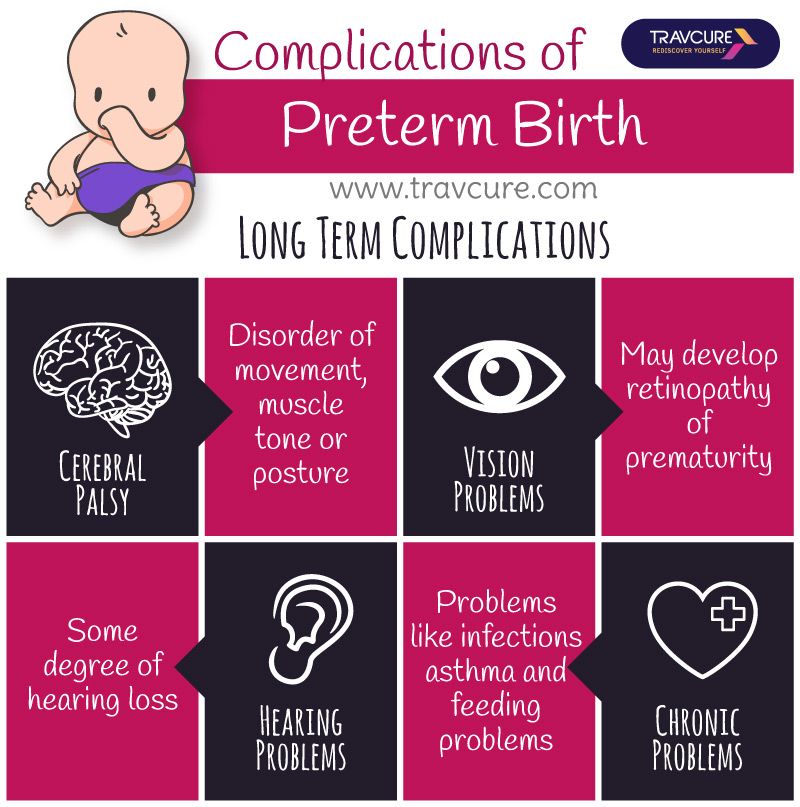

As preterm babies get older, some of them may face ongoing physical problems (such as asthma or cerebral palsy). They may also face developmental challenges (such as difficulties paying attention or lack of motor control). This may be especially true for babies who were very small at birth.

They may also face developmental challenges (such as difficulties paying attention or lack of motor control). This may be especially true for babies who were very small at birth.

Once your child reaches school age, it will be important for you to work closely with his teacher and other school staff to identify any areas of concern. They can also help you find the right resources for help. If the school does not have the resources your child needs, his teachers can help you find local groups or programs to help him do well in school. You are not alone! Your child's teachers and health care team are dedicated to helping you meet all his health and educational needs.

All children will babble before they say real words. All children will pull up to a stand before they walk. We are sure that children will develop in these patterns. However, children can reach these stages in different ways and at different times. This is especially true if they were born preterm. Take some time to think about your child's development and answer the following questions. Contact your child's doctor if you have any questions about your child's development.

Contact your child's doctor if you have any questions about your child's development.

Your Child's Development

How does my child like to communicate?

How does he let me know what he is thinking and feeling?

How does my child like to explore how to use his body?

Does he prefer using his fingers and hands (small muscles)?

Does he prefer using his arms and legs (large muscles)?

How does my child respond to new situations?

Does he jump right in?

Does he prefer to hang back and look around before he feels safe?

How does my child like to explore?

What kinds of objects and activities interest him?

What do those interests tell me about him?

What are my child's strengths?

In what ways does my child need more support?

The information contained on this Web site should not be used as a substitute for the medical care and advice of your pediatrician. There may be variations in treatment that your pediatrician may recommend based on individual facts and circumstances.

There may be variations in treatment that your pediatrician may recommend based on individual facts and circumstances.

Milestones of First 18 Months

Written by Jennifer D'Angelo Friedman

All parents are concerned about their children hitting certain milestones on time. But when your baby comes early, those first few months and years can be a time of watching and waiting. Because preemies face greater health risks, you may worry more about whether your child will do certain things on time.

Laurel Bear, MD, a pediatrician at the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, can ease your concerns. Premature babies have the same milestones as babies born on time -- if you adjust the typical timeline for their early birth, she says.

'Adjusted Age' Explained

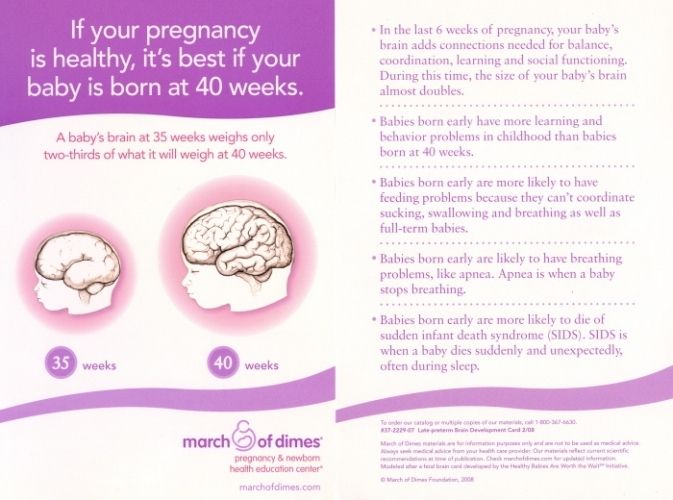

Newborns who've spent less than 37 weeks in the womb are considered premature. A normal pregnancy lasts about 40 weeks.

To figure out what a child should be doing and when, it's important to look at their adjusted age (also known as the corrected age). That's based on Mom’s original due date, Bear says.

That's based on Mom’s original due date, Bear says.

For example, when a baby is born 2 months premature, and is now 4 months old, "we’re not going to expect them to be doing what a 4-month-old is doing. We’re really looking at what a 2-month-old should be doing,” she says.

Most preemies do catch up to their peers who were born on time, but it’s important to be patient, Bear says. A baby who’s faced significant medical issues may need a little more time to reach her milestones.

“We look at them and say, ‘This little baby spent a long time trying to survive.’ What should this baby be doing? I give them a little bit of a break. You may be 6 months old, but you spent 2 months in the hospital.”

The earlier an infant arrives, the longer she may need to catch up -- but most do get there, Bear says. A baby born at 36 weeks may not be caught up at 6 months, but may be at within the normal range by 12 months. A baby born at 26 weeks or less may not catch up until they’re 2-and-a-half or 3 years old.

The First 18 Months Adjusted: A Timeline

Just like with full-term babies, milestones for premature infants can vary. But Bear says some key things should happen around the following times:

2 months adjusted

- Begins to control her head

- Makes sounds like cooing and different cries

- Smiles at people

- Recognizes parents and caregivers

4 months adjusted

- Lifts her head up and looks around while on her tummy

- Rolls over

- Follows faces and objects

6 months adjusted

- Sits on her own

- Gets on her hands and knees

- Starts to crawl

- Looks at toys

- Is curious about things out of reach

- Babbles consonant and vowel combinations (dada, baba, mama)

9 months adjusted:

- Crawls everywhere

- Pulls to stand

- Understands “no”

- Copies sounds and gestures

- Has more vocal variety

- Plays peek-a-boo

12 months adjusted

- Cruises along furniture

- Begins taking solo steps

- Starts to stand alone

- Picks up small items

- Responds to simple questions like “Where’s Daddy?”

- Tries to say words you say

- Uses simple gestures, like shaking her head “no” or waving “bye-bye”

- Cries when parents leave

- Has favorite things, like a stuffed animal or blanket

- Begins to say Mama with meaning (she knows Mama is Mama)

15 months adjusted

- Walks with coordination

- Squats

- Can do shape sorters or simple puzzles

- Has three words besides Mama and Dada she uses to name things or to ask for things

- Looks at or points to pictures in books

- Follows more directions

18 months adjusted

- Walks up stairs

- Begins to run

- Pulls a toy when walking

- Can undress

- Drinks from a cup and eats with a spoon

- Has a vocabulary of about 18 words

- Says and shakes her head “no”

- Points to what she wants

Every Baby Is Different

Even after adjusting for age, it’s important to remember that no two babies are the same.

The key is to look at each baby individually, says Martha Caprio, MD, associate professor at NYU Langone Medical Center. Parents might call one week worried that their baby hasn’t reached a milestone like rolling over, then report back that it happened a week later. Most babies will get to their developmental goals, she says.

“When parents don’t use the [age] adjusted milestones, that’s when it becomes an issue,” Caprio says.

Premature puberty in children

Premature sexual development (PPR) is the early onset of the formation of secondary sexual characteristics in children: up to 8 years in girls and up to 9 years in boys.

Symptoms of precocious puberty

The onset of sexual development is characterized by physical and emotional changes that usually do not go unnoticed by parents. Early sexual development in girls under 8 years of age is manifested by an increase in the mammary glands, the appearance of pubic and armpit hair, and the appearance of acne. Boys under 9years, the testicles and penis increase, the voice “breaks”, sexual hair appears, and acne also occurs. An increase in the level of sex hormones in the blood leads to an increased rate of bone development, in girls, fatty tissue is redistributed according to the female type (hips are rounded, a waist appears), in boys muscle mass increases. It happens that the first symptom that attracts attention is the acceleration of growth: a child who used to be the same height as his peers or shorter suddenly begins to grow rapidly, ahead of other children.

Boys under 9years, the testicles and penis increase, the voice “breaks”, sexual hair appears, and acne also occurs. An increase in the level of sex hormones in the blood leads to an increased rate of bone development, in girls, fatty tissue is redistributed according to the female type (hips are rounded, a waist appears), in boys muscle mass increases. It happens that the first symptom that attracts attention is the acceleration of growth: a child who used to be the same height as his peers or shorter suddenly begins to grow rapidly, ahead of other children.

Causes and forms of precocious puberty

There are two types of PPR. Central PPR is a premature “switching on” of the central mechanisms that regulate puberty (sexual development). Its other name is gonadotropin-dependent PPR (due to the action of gonadotropic hormones of the pituitary gland). The central mechanisms for regulating sexual development are located in the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, where hormones are produced that act on the hormone-producing cells of the ovaries and testicles, stimulating the production of sex hormones in them - estrogens in girls and androgens in boys (see figure).

Scheme of regulation of sexual development. The hypothalamus produces gonadotropin-releasing hormone (Gn-RH), which triggers the synthesis of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) in the pituitary gland. LH and FSH, in turn, act on the sex glands, stimulating the synthesis of androgens in the testicles and estrogens in the ovaries.

"Premature start" may be the result of organic damage to the nervous system, a consequence of trauma, the presence of a volumetric formation in the brain. Sometimes it happens that the examination does not reveal serious organic causes, and in this case the so-called idiopathic (“causeless”) central PPR is established.

The second type of PPR is peripheral. Peripheral PPR is characterized by the fact that the ovaries or testicles (testicles) themselves begin to produce an increased amount of sex hormones. The cause may be hormone-producing cysts, volumetric formations.

It is also worth noting that there is a division of PPR into full and incomplete forms. In the full form, sex hormones act on all organs and tissues dependent on them, therefore, in such cases, not only the appearance of secondary sexual characteristics is noted, but also the increase and development of the uterus and ovaries in girls, the penis and testicles in boys, growth processes are accelerated.

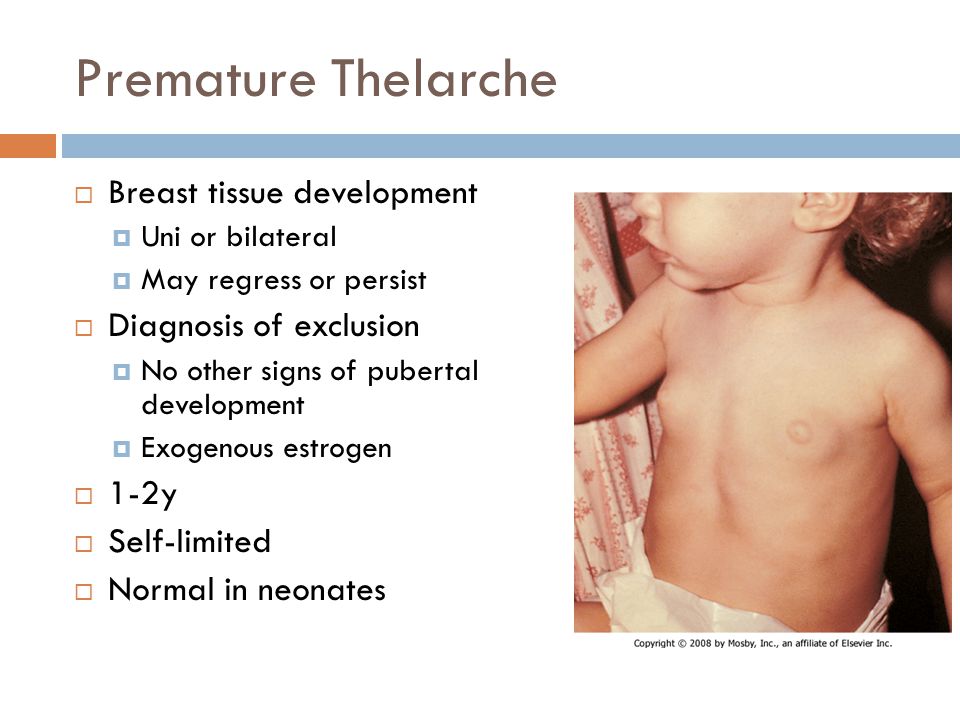

An incomplete form of premature sexual development is distinguished either by the isolated appearance of the mammary glands in girls (thelarche), or the isolated appearance of pubic hair growth (adrenarche, pubarche) in the absence of other signs of sexual development.

Complications and consequences

PPR can be associated with great psycho-emotional stress for the child: at an age when the desire to be like friends in everything is natural, the child begins to differ sharply from other children, which can become a source of complexes and difficulties in communication.

Another significant complication in PPR is the deterioration of the growth prognosis. The advance in the growth of peers is due to the accelerated maturation of bones. A “growth leap” occurs early in a child, growth zones close earlier and therefore the final height of children with BPD may be below average.

Diagnostic methods

The appearance of signs of sexual development in girls under 8 years of age and in boys under 9 years of age is a reason to contact a pediatric endocrinologist.

In order to establish whether or not there is a PPR and to understand the causes of the changes that have appeared, the doctor conducts an examination with an assessment of the degree of sexual development, measurement of growth and growth rate. The anamnesis of the child's life is examined in order to identify possible causes that led to the PPR. Further, a study is carried out, which includes an assessment of the hormonal profile, determination of bone age, ultrasound examination of the gonads, MRI (if necessary). Often, a special laboratory test may be required to assess the functional activity of the central link that regulates the function of the gonads. This is due to the fact that the gonadotropic hormones of the pituitary gland are secreted into the blood in a pulsed mode, and taking blood simply on an empty stomach may not always reflect their true level. Therefore, for differential diagnosis between the central and peripheral forms of PPR, according to indications, a test is performed with a drug that allows to assess the maximum level of gonadotropic blood hormones.

Often, a special laboratory test may be required to assess the functional activity of the central link that regulates the function of the gonads. This is due to the fact that the gonadotropic hormones of the pituitary gland are secreted into the blood in a pulsed mode, and taking blood simply on an empty stomach may not always reflect their true level. Therefore, for differential diagnosis between the central and peripheral forms of PPR, according to indications, a test is performed with a drug that allows to assess the maximum level of gonadotropic blood hormones.

Treatment of precocious puberty in girls and boys

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (Gn-RH) analogs are used to treat the central form of precocious puberty. With regular administration, this drug blocks the secretion of the pituitary sex hormones (LH and FSH). The most common regimen for administering the drug is intramuscular injection once every 28 days. Treatment with GnRH analogs is generally well tolerated. During the first month of treatment, there may be an increase in signs of sexual development, decreasing if the correct regimen is observed. Side effects are rare and include headache, menopausal symptoms, and possible inflammation at the injection site.

During the first month of treatment, there may be an increase in signs of sexual development, decreasing if the correct regimen is observed. Side effects are rare and include headache, menopausal symptoms, and possible inflammation at the injection site.

Peripheral forms of PPR require a different approach to treatment. In these cases, therapy with GnRH analogs is ineffective, since in these variants of PPR there is no increased pubertal secretion of gonadotropic hormones from the pituitary gland. The choice of treatment tactics depends on the cause of PPR. In some cases, surgery may be required (removal of a cyst or tumor) or the possibility of using drugs that block the effect of sex steroids on target organs may be considered.

Central precocious sexual development: to treat or not to treat?

The decision on the need for therapy of central PPR is decided individually. Treatment has several goals: on the one hand, to stop the effect of sex hormones on bone tissue and improve growth prognosis, on the other hand, to remove the negative impact on the psycho-emotional background of the child. Therefore, when deciding on the treatment of CPPR, the doctor evaluates several factors: the age and height of the child at the time of diagnosis, the rate of progression of signs of sexual development, the degree of psychological readiness of the child for sexual development.

Therefore, when deciding on the treatment of CPPR, the doctor evaluates several factors: the age and height of the child at the time of diagnosis, the rate of progression of signs of sexual development, the degree of psychological readiness of the child for sexual development.

Sexual development: talking to a child

Not only the attending physician, but also parents should discuss with the child what is happening with his body. It is very important to make it clear to the child that he is normal and that the changes that his body undergoes are natural, albeit somewhat premature. Before the age of 8, sexual development can be scary for children, but if they feel confident and supported by their parents, then it will be much easier for them to accept the situation.

Precocious puberty: causes, diagnosis, treatment | #01/14

Part 2. See the beginning of the article in No. 11, 2013

False PPR

False or LH-RH-independent PPR is understood as the development of secondary sexual characteristics associated with autonomous excess production of steroids by the adrenal glands and gonads. The most common cause of this form of PPR is congenital adrenal dysfunction (CHD). Less commonly, hormonally active tumors originating from the above organs, as well as tumors that secrete hCG (chorionepitheliomas, hepatomas, teratomas).

The most common cause of this form of PPR is congenital adrenal dysfunction (CHD). Less commonly, hormonally active tumors originating from the above organs, as well as tumors that secrete hCG (chorionepitheliomas, hepatomas, teratomas).

Congenital adrenal dysfunction is a group of autosomal recessive hereditary diseases caused by genetic defects in steroidogenesis enzymes. The main link in the pathogenesis is a violation of the synthesis of cortisol and / or aldosterone. A persistent negative feedback cortisol deficiency stimulates the secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which causes hyperplasia of the adrenal cortex, producing excessive amounts of androgens.

In the vast majority of cases, there is a deficiency of the enzyme 21-hydroxylase, 10 times less often - a deficiency of 11β-hydroxylase. At present, numerous point mutations of genes have been found that determine one or another deficiency, which correlates with the clinic of gluco- and mineralococticoid insufficiency and severe virilization.

At birth, the external genital organs of girls have a heterosexual structure: varying degrees of clitoral hypertrophy, fused labia majora resemble the scrotum, forming a single urogenital opening at the base of the clitoris (urogenital sinus).

The formation of the external genitalia in boys takes place according to the isosexual type: the penis is enlarged, the scrotum is wrinkled and pigmented, erections appear early. In the first years of life, due to the anabolic action of androgens, children grow rapidly, their skeletal muscles develop, their voice coarsens, male-type hair appears on the face, chest, abdomen, limbs. In both sexes, the differentiation of the skeleton is significantly accelerated.

In aldosterone deficiency, the disease is acute. The disease manifests itself from the first weeks after birth and poses a serious threat to health. Clinically, this form is characterized by vomiting, dehydration, and a decrease in blood pressure (BP). In the blood, the amount of sodium decreases and potassium increases, the level of renin is high.

With a deficiency of 11β-hydroxylase, along with the above symptoms, an increase in blood pressure is detected, which can complicate the course of the disease. Girls in prepuberty and puberty lack secondary female sexual characteristics and menstruation.

In the blood, the level of renin is reduced, and sodium can be increased.

Hormonal diagnosis is based on determining the level of 17-hydroxyprogesterone. With 21-hydroxylase deficiency, it is many times higher than normal. In patients with 11β-hydroxylase deficiency, the increase in 17-hydroxyprogesterone is less.

The main goal of treatment is to suppress the excess production of ACTH. For this purpose, glucocorticoids are selected or combined with mineralcorticoids [11].

Van Wyck-Grombach syndrome occurs in children with long-term undiagnosed primary hypothyroidism. By the time PPR symptoms appear, children have a classic picture of severe hypothyroidism: chondrodystrophic physique, significant growth retardation, muscle hypotonia, a low, rough voice, and psychomotor retardation.

The diagnosis was confirmed by low levels of thyroid hormones (T3 and T4) and a sharp increase in pituitary thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH).

In girls, the first signs of PPR are an increase in the mammary glands, in some with lactorrhea, the appearance of menarche. Adrenarche (pubic and axillary hair growth) is uncharacteristic. All patients have high levels of prolactin, as for gonadotropins (LH and FSH), they moderately increased. Ultrasound examination (ultrasound) of the small pelvis in all cases visualizes polycystic ovaries.

A feature of the PPR clinic in boys with this syndrome is a moderate increase in testicles with a weak androgenization of the body, which corresponds to a moderate increase in testosterone levels.

In both sexes, bone maturation lagged behind biological age.

Replacement therapy with thyroid drugs causes a regression of the symptoms of PPR.

Androgen-secreting tumors of the adrenal glands (androsteromas) are, as a rule, adrenocarcinomas. Rarely seen in children. In early adolescence, the frequency of adrenocarcinomas increases in children with Wiedemann-Beckwith syndrome (visceromegaly, macroglossia, hemihypertrophy) and Li-Fraumeni syndrome (multiple malignant neoplasms).

Rarely seen in children. In early adolescence, the frequency of adrenocarcinomas increases in children with Wiedemann-Beckwith syndrome (visceromegaly, macroglossia, hemihypertrophy) and Li-Fraumeni syndrome (multiple malignant neoplasms).

In children with adrenocarcinomas, abnormal expression of tumor markers and a decrease in the expression of factors that suppress tumor growth, the genes of which are localized on the long arm of the 11th chromosome, were revealed. Abnormalities of this chromosome are found in most patients with adrenocorcinoma.

In boys, a clinical picture is observed according to the type of isosexual sexual development: muscle mass increases, growth rate increases, secondary hair growth, erections appear, and the voice timbre changes. However, the volume of the testicles does not increase.

Girls show signs of virilization: apocrine glands (sweat, sebaceous, hair follicles) are activated, body weight increases due to muscle tissue, and the clitoris hypertrophies. Boys and girls grow faster.

Boys and girls grow faster.

Estrogen-producing tumors of the adrenal glands (corticoestromas) are very rare in children. In girls, in this case, they proceed according to the type of isosexual PPR, and in boys in the clinic, the leading symptom is gynecomastia.

The study of the hormonal profile is characterized by an increase in the level of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) and juvenile levels of LH and FSH. In some cases, the concentration of testosterone, estradiol increases. Ultrasound is used in the diagnosis of adrenal tumors.

Steroid-secreting gonadal tumors are rare in childhood. In older girls, arrhenoblastomas (malignant tumors) are found, located in the cortical layer or hilum of the ovary. Undifferentiated tumors have a more pronounced virilizing effect, while differentiated ones have both a weakly pronounced masculinizing and feminizing effect. A granulosa cell tumor of the ovaries, often of benign origin, secretes a large amount of estrogen, causing isosexual PPR. Excess estrogen causes menstrual syndrome - from scanty to heavy bleeding, pigmentation of the areola, hardening of the glandular tissue, hypertrophy and swelling of the vulva. The amount of estradiol is sharply increased with pre-pubertal LH and FSH levels.

Excess estrogen causes menstrual syndrome - from scanty to heavy bleeding, pigmentation of the areola, hardening of the glandular tissue, hypertrophy and swelling of the vulva. The amount of estradiol is sharply increased with pre-pubertal LH and FSH levels.

In boys, testosterone-secreting leidigoma is rare. This is a benign tumor that affects one testicle. Outwardly, it is enlarged, bumpy, dense consistency. Androgenization syndrome develops rapidly.

Sertolioma is a neoplasm containing Sertoli cells. In this case, the release of estradiol into the blood increases, which forms gynecomastia in boys, accelerates growth and bone maturation.

The level of gonadotropic hormones in both tumors of the testicles corresponds to the age of children [12].

Follicular ovarian cysts are a common cause of PPR in girls. However, they are also found in healthy girls in the prepubertal period. The diameter of these cysts is from 0.5 to 1.5 cm. The presence of a cyst in the ovaries is not a sign of pathology. But in some cases, the cystic tissue begins to prematurely and excessively produce estradiol. As a rule, these cysts are 3-4 cm in size. Follicular cysts may be accompanied by irregular scanty sanious discharge from the genital tract, hypertrophy and swelling of the skin of the vulva, increased vaginal folding, moderate pigmentation and swelling of the nipples. The size of the uterus and bone maturation correspond to the passport age. The cause that causes the formation and persistence of follicular cysts may be a transient rise in gonadotropins (mainly FSH). Ovarian cysts are found on pelvic ultrasound. In most cases, follicular cysts spontaneously regress after 1.5–2 months and the PPR clinic disappears. Surgical treatment is subject to cysts of large sizes or occurring with complications [13].

But in some cases, the cystic tissue begins to prematurely and excessively produce estradiol. As a rule, these cysts are 3-4 cm in size. Follicular cysts may be accompanied by irregular scanty sanious discharge from the genital tract, hypertrophy and swelling of the skin of the vulva, increased vaginal folding, moderate pigmentation and swelling of the nipples. The size of the uterus and bone maturation correspond to the passport age. The cause that causes the formation and persistence of follicular cysts may be a transient rise in gonadotropins (mainly FSH). Ovarian cysts are found on pelvic ultrasound. In most cases, follicular cysts spontaneously regress after 1.5–2 months and the PPR clinic disappears. Surgical treatment is subject to cysts of large sizes or occurring with complications [13].

Incomplete PPR forms

Premature isolated thelarche (PT), an enlargement of the mammary glands in girls, is the most common benign variant of PPR. In most cases, it is observed at the age of 6-24 months in girls who are breastfed, in small and preterm girls. Rarely found after reaching 3 years of age.

In most cases, it is observed at the age of 6-24 months in girls who are breastfed, in small and preterm girls. Rarely found after reaching 3 years of age.

The reason for the increase in the mammary glands is considered to be a high level of gonadotropic hormones (especially FSH). The peak concentration of FSH after birth lasts up to 6 months and then slowly begins to decline by 2–3 years. At preschool age, in such patients, follicles are detected in the ovaries, reaching the size of adult women. Some authors associate this with dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary system. FSH activates the enzyme aromatase, which leads to increased production of estrogens from testosterone in the granulosa tissue of the follicle. Other causes of isolated thelarche may be periodic estrogen surges or increased sensitivity of the receptor apparatus of the mammary glands to estrogens.

Enlarged mammary glands are palpable on one or both sides. Some girls have moderate estrogenization of the vulva. There are no other secondary sexual characteristics.

There are no other secondary sexual characteristics.

With isolated thelarch, the growth rate is not disturbed (5-6 cm per year), the bone age corresponds to the chronological one. Most often, the process regresses on its own and does not require medical intervention, but at the same time, thelarche that appears may be the first sign of true or false PPR, so all girls with thelarche must be re-examined (at least 2 times a year).

If thelarche is combined with accelerated bone age, but there are no other signs of precocious puberty, this condition is assessed as an intermediate form of PPR and requires more careful monitoring (quarterly) with monitoring of ovarian ultrasound, bone age.

Premature adrenarche (PA) is the appearance of isolated pilosis on the pubis and / or armpits in girls under 8 years old, and in boys up to 9 years old. It is more common in girls aged 6-8 years. PA may be a variant of the norm, given that the maturation of the reticular zone of the adrenal cortex begins at 6 years of age. While the secretion of GnRH, responsible for the onset of puberty, starts later. The cause of pubertal hair growth is an increase in the production of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and its DHEA-S, as well as delta-4-androstenedione, testosterone precursors that stimulate pubic and axillary hair growth. In girls, PA may be associated with excessive peripheral conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (increased aromatase activity). In the absence of other signs of androgenization of the body - acceleration of growth, maturation of the skeleton, prepubertal size of the uterus and ovaries, and in boys testicles, normal testosterone levels and moderately increased DHEA-S, the prognosis is favorable and sexual development does not deviate from the norm.

While the secretion of GnRH, responsible for the onset of puberty, starts later. The cause of pubertal hair growth is an increase in the production of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and its DHEA-S, as well as delta-4-androstenedione, testosterone precursors that stimulate pubic and axillary hair growth. In girls, PA may be associated with excessive peripheral conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (increased aromatase activity). In the absence of other signs of androgenization of the body - acceleration of growth, maturation of the skeleton, prepubertal size of the uterus and ovaries, and in boys testicles, normal testosterone levels and moderately increased DHEA-S, the prognosis is favorable and sexual development does not deviate from the norm.

However, in some children, PA can be triggered by excessive production of ACTH (hydrocephalus, meningitis, etc.). There is more and more evidence of the association of PA with non-classical forms of congenital adrenal dysfunction (CHD) and, in particular, a deficiency in the activity of the enzyme 21-hydroxylase and less often 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase.

In the presence of a virilizing disease, clinical signs of androgenization appear: in girls - clitoral hypertrophy, high posterior perineal commissure, hirsutism, development of the muscular system; in boys - voice change, penis enlargement, activation of the sebaceous and sweat glands. These children show accelerated growth and bone age.

Girls with premature adrenarche should be at risk for developing polycystic ovary syndrome. This group of patients requires corrective therapy with glucocorticoids [14].

Differential diagnosis

Primary diagnosis is based on a thorough history taking and assessment of the degree of sexual development of the child according to the Tanner-Marshal classification. Early puberty in males in the maternal and paternal family is characteristic of testotoxicosis. The presence in the family of brothers with PPR or sisters with symptoms of virilization is more common in VDKN.

From the anamnesis, it is necessary to find out the time of appearance of secondary sexual characteristics, the speed of their progression. In girls, the degree of development of the mammary glands and areola, the condition of the skin, external genitalia, and the presence of bloody discharge are assessed.

In girls, the degree of development of the mammary glands and areola, the condition of the skin, external genitalia, and the presence of bloody discharge are assessed.

In boys, the degree of masculinization, the presence of pubic and axillary hair, the degree of change in the external genitalia (the size of the penis, testicles).

For both sexes, growth performance is assessed by calculating the coefficient of standard deviation (SD).

Early onset and rapid onset of symptoms are typical of testotoxicosis and hypothalamic hamartoma. Clinical symptoms of hypothyroidism associated with PPR suggest Van Wyck–Grombach syndrome.

When a history of congenital anomalies of the central nervous system, trauma, inflammation is indicated, one should think about the cerebral form of PPR.

The study of bone age (X-ray of the hand), more than another indicator that correlates with the stage of sexual development of the child, is mandatory for assessing the degree of PPR. If the bone age is more than 2 SD ahead of the passport age, this indicates an excess of sex steroids. A significant acceleration of bone maturation is characteristic of central forms of PPR, as well as androgen-secreting tumors of the adrenal glands, VDKN. In isolated forms of PPR (premature thelarche and adrenarche), bone age corresponds to chronological age.

If the bone age is more than 2 SD ahead of the passport age, this indicates an excess of sex steroids. A significant acceleration of bone maturation is characteristic of central forms of PPR, as well as androgen-secreting tumors of the adrenal glands, VDKN. In isolated forms of PPR (premature thelarche and adrenarche), bone age corresponds to chronological age.

The tumor variant of cerebral PPR is excluded using computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These research methods are included in the mandatory standard of the survey plan.

Pelvic ultrasonography should be performed in all girls with suspected PPR. The size of the ovaries and uterus should be comparable to the level of sex hormones. Bilateral ovarian enlargement is a reliable sign of the central form of PPR.

Ovarian structure, follicle diameter, fundus-cervix ratio, uterine-endometrial length are important evaluative parameters, but many experts believe that they are not decisive in the differential diagnosis between PT and central forms of PPR. The ovaries can be asymmetrically enlarged in girls with peripheral forms of PPR [15].

The ovaries can be asymmetrically enlarged in girls with peripheral forms of PPR [15].

In boys, MRI or CT is preferable for detecting adrenal masses.

To clarify the form of PPR, the levels of gonadotropic hormones, estrogens and androgens are determined. The levels of LH, FSH and estradiol reflect the state of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal system, the concentration of DHEA and DHEA-S - the secretory activity of the adrenal glands.

For differential diagnosis between the central and false forms of PPR, in all cases, a functional test with LH-WG should be performed. With true PPR, the test with Diferelin causes a pubertal response of LH and FSH. In children with peripheral forms of PPR, gonadotropins do not respond to stimulation.

An increase in DHEA-S is characteristic of premature adrenarche. An excess of adrenal androgens is possible with virilizing forms of VDKN, tumors of the adrenal glands and ovaries [16].

The tumor cause of PPR requires a study for the presence of AFP, beta-hCG, CEA.

Treatment

The main goal of PPR treatment is the elimination of the clinical symptoms of the disease, the normalization of the secretion of steroid hormones that accelerate bone maturation and the closure of growth zones to achieve socially acceptable growth.

Treatment of true PPR involves blocking the impulse secretion of LH-RH. An indication for the appointment of synthetic analogues of GnRH is an early age and rapid dynamics of bone maturation. With a slowly progressive disease, this treatment should be carefully approached.

Triptorelin has been clinically tested in Russia. The drug is administered intramuscularly, the frequency of administration is 1 time every 28 days. Children weighing less than 20 kg - 1.875 mg, more than 20 kg - 3.75 mg.

Normalization of the FSH level is noted after 3 weeks, a decrease in the size of the testicles and uterus from the 6th month of treatment. Inhibition of growth rate and skeletal maturation is observed by the end of the 1st year of treatment. The growth forecast is improving. The drug is well tolerated by patients. During treatment, constant monitoring of changes in bone age, growth rate, and the standard deviation coefficient (SDS) of growth is necessary [17].

The growth forecast is improving. The drug is well tolerated by patients. During treatment, constant monitoring of changes in bone age, growth rate, and the standard deviation coefficient (SDS) of growth is necessary [17].

The data confirm the expediency of drug-induced isolated thelarche against the background of reduced thyroid function, with Van Wyck–Grombach syndrome, hormone replacement therapy with thyroid hormones is indicated. The criterion for the adequacy of treatment are normal readings of TSH and free T4.

With McCune-Albright-Braytsev syndrome, pathogenetic therapy has not been developed. In cases of frequent massive bleeding, it is possible to use cyproterone in a daily dose of 70-100 mg. The drug has an antiproliferative effect on the endometrium, which leads to the cessation of menstruation. To reduce hyperestrogenemia, an aromatase activity inhibitor is used - testolactone at a dose of 20–40 mg / kg per day or tamoxifen, which blocks estrogen receptors.![]()

Tactics for the treatment of testotoxicosis involves the appointment, firstly, medroxyprogesterone (inhibition of testosterone synthesis), secondly, ketoconazole (inhibition of the synthesis of hormones of the gonads and adrenal glands) or a combination of testolactone and spironolactone (aromatase inhibition and androgen receptor blockade). Ketoconazole is prescribed at a dose of 30 mcg/kg per day per os. The use of the drug may be accompanied by adrenal insufficiency and impaired liver function. With a late start of treatment, with a bone age that has reached 12–13 years, a picture of true PPR may develop, in this case, therapy with synthetic analogues of LH-RH is performed [10].

Functional ovarian cysts in most cases undergo spontaneous regression within four months. With the formation of follicular cysts in utero or in newborn girls, treatment is usually not carried out. Resection of the ovary or laparoscopic exfoliation with suturing of the walls is performed if cysts with a diameter of more than 8 cm are detected.

Surgical methods of treatment are used in children with PPR, which develops against the background of hormonally active tumors of the adrenal glands, ovaries, and volumetric formations of the central nervous system, however, in some patients, the removal of neoplasms does not lead to regression of PPR. Hypothalamic hamartoma is removed only for strict neurosurgical indications. In the presence of focal and cerebral symptoms, surgery or radiation therapy corresponding to the type of tumor is performed. It must be remembered that radiation exposure or surgical intervention on the bottom of the 3rd ventricle can provoke PPR [10]. For this reason, such children should be constantly monitored by an endocrinologist. In cases where the leading clinical manifestation of the disease is only the symptoms of PPR, only conservative treatment is possible.

In girls with heterosexual precocious puberty against the background of VDKN, if necessary, surgical correction of the external genital organs is performed. A penis-shaped or hypertrophied clitoris is recommended to be resected immediately after diagnosis, regardless of the age of the child [17].

A penis-shaped or hypertrophied clitoris is recommended to be resected immediately after diagnosis, regardless of the age of the child [17].

Further management of patients

All children diagnosed with precocious puberty should be monitored continuously (at least once every 3-6 months) before and throughout the entire period of physiological puberty. Treatment of true PPR with triptorelin is carried out continuously until the onset of puberty, since the cessation of its administration causes the resumption of the disease. The study of bone age is controlled with any form of PPR once a year.

Literature

- Prete G., Couto-Silva A., Trivin. C. et al. Idiopathic central precocious puberty in girls: presentation factors // PMC. 2008.

- Kobozeva NV, Kuznetsova MN, Gurkin Yu. A. Gynecology of children and adolescents. St. Petersburg, 1988. 295 p.

- Dedov II, Semicheva TV, Peterkova VA Sexual development of children: norm and pathology.

M., 2002. 232 p.

M., 2002. 232 p. - Jospe N. Precocious Puberty. MD, 2012. www.merckmanuals.com.

- Kotwal N., Yanamandra U., Menon A. S. et al. Central precocious puberty due to hypothalamic hamartoma in a six-month-old infant girl // PMC. 2012.

- Upreti V., Bhansali A., Mukherjee K. K. et al. True precocious puberty with vision loss // PMC. 2009.

- Pagon R. A., Adam M. P., Bird T. D. et al. GeneReviews™, Russell-Silver Syndrome. University of Washington, Seattle, 1993–2013.

- Stephen M. D., Zage P. E., Waguespack S. G. Gonadotropin-Dependent Precocious Puberty: Neoplastic Causes and Endocrine Considerations // PMC. 2011.

- Berberoglu M. Precocious Puberty and Normal Variant Puberty: Definition, etiology, diagnosis and current management // J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2009, June, 1 (4): 164–174.

- Peterkova V. A.

, Semicheva T. V., Gorelyshev S. K., Lozovaya Yu. V. Premature sexual development. Clinic, diagnosis, treatment. A guide for doctors. M., 2013. 40 p.

, Semicheva T. V., Gorelyshev S. K., Lozovaya Yu. V. Premature sexual development. Clinic, diagnosis, treatment. A guide for doctors. M., 2013. 40 p. - Lowe L, Wong K. Precocious puberty in boys. www.urolog.kz

- Lee P. Precocious puberty in girls. www.urolog.kz

- Faizah M. Z., Zuhanis A. H., Rahmah R. et al. Precocious puberty in children: A review of imaging findings // PMC. 2012.

- Semicheva T.V. Premature sexual development (clinical, hormonal, molecular-genetic aspects. Dis. Doc. Med. Sci. M., 1998.

- Bajpai A., Menon P. S. N. Contemporary issues in precocious puberty // PMC. 2011.

- Reisch N., Hogler W., Parajes S. et al. A diagnosis not to be missed: Non-classic steroid 11β-hydroxylase deficiency presenting with premature adrenarche and hirsutism // PMC. 2013.

- Precocious puberty By Mayo Clinic staff.