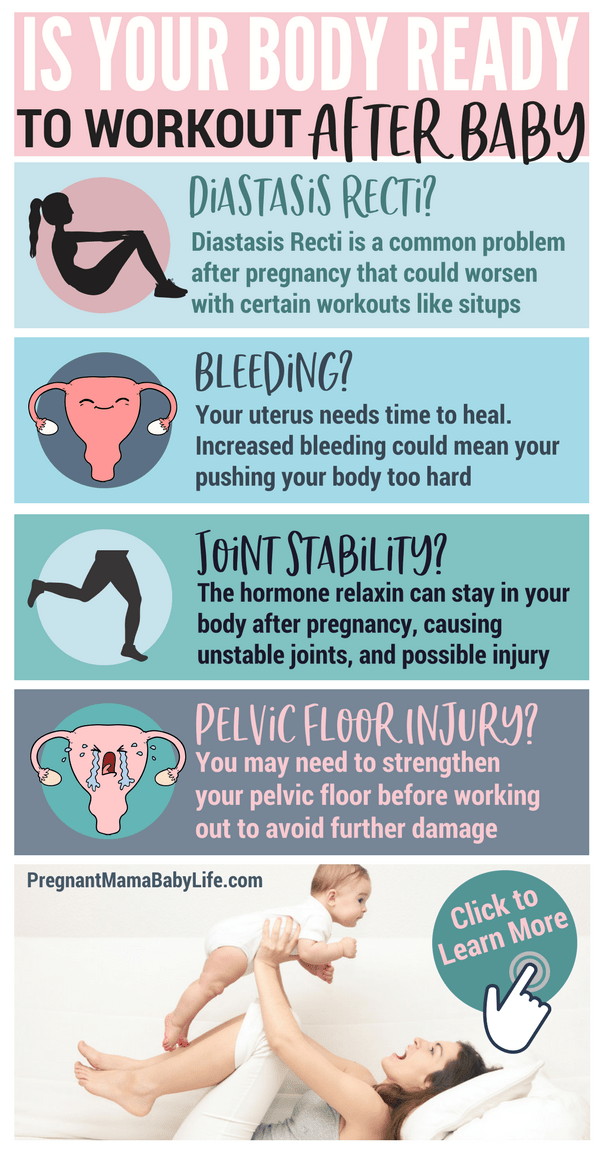

When does your pelvic spread during pregnancy

Pelvic alignment changes during the perinatal period

PLoS One. 2019; 14(10): e0223776.

Published online 2019 Oct 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223776

, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – original draft,1,*, Data curation, Project administration,2, Data curation, Methodology,3, Data curation, Investigation,3, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration,3 and , Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing4

Abimbola O. Famuyide, Editor

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

- Supplementary Materials

- Data Availability Statement

Background

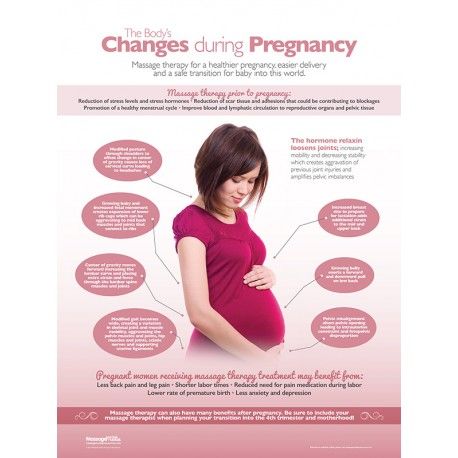

The function of the pelvic bones is to transfer load generated by body weight. Proper function of the pelvic bones can be disturbed by alignment changes that occur during pregnancy. Further, misalignment of the pelvic bones can lead to pain, urinary incontinence, and other complications. An understanding of the timing and nature of pelvic alignment changes during pregnancy may aid in preventing and treating these complications.

Objective

To investigate the changes in pelvic alignment during pregnancy and one month after childbirth.

Methods

This is a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. Pelvic measurements were obtained for 201 women at 12, 24, 30, and 36 weeks of pregnancy, and 1 month after childbirth. The anterior and posterior width of the pelvis (the distance between the bilateral anterior superior iliac spines and the bilateral posterior superior iliac spines), the anterior pelvic tilt, and pelvic asymmetry (the mean left and right pelvic tilt degrees and the bilateral difference of the anterior pelvic tilt) were measured. For the change in pelvic alignment, a Friedman test was conducted to determine any significant difference in the measurements over time.

Results

The anterior and posterior width of the pelvis became significantly wider with pregnancy progress and the anterior width of the pelvis at 1 month after childbirth remained wider than that at 12 weeks of pregnancy (p < 0.001). The anterior pelvic tilt increased during pregnancy and decreased after childbirth (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Some changes in pelvic alignment occur continuously during the perinatal period. Changes in the anterior width of the pelvis are not recovered at one month post-childbirth. Understanding these perinatal changes may help clinicians avert complications due to pelvic misalignment.

During pregnancy and after childbirth, significant changes occur to women’s bodies. Swelling of the abdomen with fetal growth and weight gain not only around the uterus but also in the whole body are major examples [1]. In addition, bone alignment changes, especially around the pelvis, occur in pregnancy [2,3]. A primary function of the pelvic bones is to transfer loads generated by body weight and gravity during activities of daily living [4]. This function is even more important during pregnancy because body weight increases over 10 kg in 40 weeks [5]. This important function requires that the pelvic bones are in a balanced position. Unfortunately, pelvic dislocation associated with pregnancy and childbirth has been reported [6].

This function is even more important during pregnancy because body weight increases over 10 kg in 40 weeks [5]. This important function requires that the pelvic bones are in a balanced position. Unfortunately, pelvic dislocation associated with pregnancy and childbirth has been reported [6].

The pelvis tilts forward as pregnancy progresses [1]. In addition, pregnancy-related hormones cause elasticity of the joints such as the sacroiliac joint, [7] and this increases the possibility of distortion of alignment. One previous study has reported a differing degree of pelvic anteversion in the right and left sides during pregnancy [8]. Multiple changes in pelvic alignment are closely related to pregnancy related ailments such as pelvic girdle pain [9]. For example, increased pelvic asymmetry during pregnancy is a risk factor for pregnancy-related sacroiliac joint pain [10]. The relatively small and flat sacroiliac joint of women compared with that of men, combined with the hormonal weakening of the ligaments and symphysis during pregnancy, may also lead to sacroiliac joint instability and pain [11]. Moreover, failed load transfer through the lumbopelvic region due to pelvic malalignment can cause low back pain [12,13] or loss of urethra closure and stress urinary incontinence [14]. Forward tilting of the pelvis is a risk factor for low back pain and pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy [15]. Furthermore, childbirth affects pelvic floor anatomy and increases the prevalence of urinary incontinence [16,17]. Accordingly, these changes significantly reduce the quality of life for many women.

Moreover, failed load transfer through the lumbopelvic region due to pelvic malalignment can cause low back pain [12,13] or loss of urethra closure and stress urinary incontinence [14]. Forward tilting of the pelvis is a risk factor for low back pain and pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy [15]. Furthermore, childbirth affects pelvic floor anatomy and increases the prevalence of urinary incontinence [16,17]. Accordingly, these changes significantly reduce the quality of life for many women.

Understanding the course of pelvic alignment changes during pregnancy and after childbirth is useful in providing medical advice for women. However, it is not clear when and how the changes of pelvic alignment occur. In our previous study, the differences in pelvic alignment among never-pregnant women, pregnant women, and postpartum women were investigated [18]. However, the study was not longitudinal in design and the changes in pelvic alignment during and after pregnancy were not assessed. A more thorough understanding of the timing and nature of gradual pelvic alignment changes and recovery during and after pregnancy may provide useful guidance for wellness during pregnancy and enable early detection of any pelvic abnormalities. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the changes in pelvic alignment during pregnancy and after childbirth.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the changes in pelvic alignment during pregnancy and after childbirth.

This study was part of a prospective, longitudinal cohort study that investigated the association between pelvic alignment and lumbopelvic pain during pregnancy. In the current study, the changes in pelvic alignment during pregnancy and after childbirth were investigated using the pelvic alignment information collected from participants in the longitudinal observational study. The present study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine (Approval number E2076). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with the guidelines.

Participants

Pregnant women were recruited at the obstetrics and gynecology clinics in Aichi Prefecture, Japan, between May 2014 and December 2014. The inclusion criteria were <12 weeks of pregnancy and a singleton pregnancy. Women with serious orthopedic disorders or neurological diseases such as after surgery for total hip arthroplasty or multiple sclerosis, respectively, were excluded. Those with high-risk pregnancies were also excluded. The obstetricians and midwives in the study’s implementation clinics checked whether the pregnant women fit the inclusion criteria or not for all pregnant women who came to the clinics for gynecological checkups. After being instructed about the study, particularly its purpose and methods, all participants gave written informed consent. In this way, 275 women who met the inclusion criteria for the survey and agreed to participate in the study were included. They were observed at 12, 24, 30 and 36 weeks of pregnancy and 1 month after childbirth. These periods were chosen for convenience to coincide with regular prenatal checkups.

The inclusion criteria were <12 weeks of pregnancy and a singleton pregnancy. Women with serious orthopedic disorders or neurological diseases such as after surgery for total hip arthroplasty or multiple sclerosis, respectively, were excluded. Those with high-risk pregnancies were also excluded. The obstetricians and midwives in the study’s implementation clinics checked whether the pregnant women fit the inclusion criteria or not for all pregnant women who came to the clinics for gynecological checkups. After being instructed about the study, particularly its purpose and methods, all participants gave written informed consent. In this way, 275 women who met the inclusion criteria for the survey and agreed to participate in the study were included. They were observed at 12, 24, 30 and 36 weeks of pregnancy and 1 month after childbirth. These periods were chosen for convenience to coincide with regular prenatal checkups.

Questionnaire

Personal characteristics (age, height, and weight before the pregnancy), and number of previous deliveries were obtained at the time of recruitment. A copy of the questionnaire, both in English and in Japanese is given as S2 File. We also recorded weight at the time of survey, method of childbirth, and duration of labor.

A copy of the questionnaire, both in English and in Japanese is given as S2 File. We also recorded weight at the time of survey, method of childbirth, and duration of labor.

Pelvic alignment

Pelvic alignment was assessed at 12, 24, 30, and 36 weeks of pregnancy, and 1 month after childbirth. Pelvic alignment was measured using a palpation meter (Performance Attainment Associates, USA). The length of the anterior and posterior pelvis and anterior pelvic tilt were measured bilaterally by placing the caliper tips of the palpation meter in contact with the ipsilateral anterior and posterior superior iliac spines (ASIS and PSIS). This method is valid, reliable, and cost-effective for calculating any changes or asymmetry in the patient’s anatomy [19,20]. During the pelvic alignment measurements, the subjects removed their shoes and stood with hands crossed in front of their chests. The lengths between both ASIS and both PSIS were measured in centimeters. Left and right anterior pelvic sagittal tilting was measured in degrees. The lengths between both ASIS and both PSIS were defined as the anterior width of pelvis and posterior width of pelvis, respectively. The mean left and right pelvic tilt degrees and the bilateral difference in pelvic tilt were defined as anterior pelvic tilt and pelvic asymmetry, respectively (). Fourteen midwives and physical therapists were trained as measurers and measured pelvic alignment of the women. Before taking the measurements, they learned the measurement method using the palpation meter and practiced repeatedly. In order to verify accuracy, nine primary measurers took separate measurements of pelvic alignment for one woman using the method outlined above. This verification procedure was repeated twice, two weeks apart. As a result, the measurement procedure showed acceptable intra- and inter-rater reliability with an Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) 1.1 of 0.989 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.971–0.996) and an ICC 2.1 of 0.992 (95% CI 0.972–0.999) for the measurements of the anterior and posterior pelvis length, and an ICC 1.

The lengths between both ASIS and both PSIS were defined as the anterior width of pelvis and posterior width of pelvis, respectively. The mean left and right pelvic tilt degrees and the bilateral difference in pelvic tilt were defined as anterior pelvic tilt and pelvic asymmetry, respectively (). Fourteen midwives and physical therapists were trained as measurers and measured pelvic alignment of the women. Before taking the measurements, they learned the measurement method using the palpation meter and practiced repeatedly. In order to verify accuracy, nine primary measurers took separate measurements of pelvic alignment for one woman using the method outlined above. This verification procedure was repeated twice, two weeks apart. As a result, the measurement procedure showed acceptable intra- and inter-rater reliability with an Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) 1.1 of 0.989 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.971–0.996) and an ICC 2.1 of 0.992 (95% CI 0.972–0.999) for the measurements of the anterior and posterior pelvis length, and an ICC 1. 1 of 0.998 (95% CI 0.995–0.999) and an ICC 2.1 of 0.998 (95% CI 0.992–1.000) for the anterior pelvic tilt in this study.

1 of 0.998 (95% CI 0.995–0.999) and an ICC 2.1 of 0.998 (95% CI 0.992–1.000) for the anterior pelvic tilt in this study.

Open in a separate window

Measurement points for pelvic alignment.

Statistical analysis

First, a normality test for all data was conducted to check if the data followed a normal distribution. Second, a Friedman test was conducted for each pelvic alignment measurement to determine any significant difference in the measurements over time. Third, Bonferroni correction for p-values was used to conduct the pairwise comparison of the 5 time points. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), with a significance threshold set at 0.05.

Participants with incomplete measurement data due to missed visits or delivery before 36 weeks of pregnancy were excluded from analyses. Complete data was obtained for 201 women. (). Demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in . They were observed at 12 (12. 9 ± 1.2 weeks), 24 (24.0 ± 0.9 weeks), 30 (30.0 ± 0.6 weeks), and 36 weeks of pregnancy (36.0 ± 0.3 weeks) and 1 month after childbirth (32.6 ± 5.6 days).

9 ± 1.2 weeks), 24 (24.0 ± 0.9 weeks), 30 (30.0 ± 0.6 weeks), and 36 weeks of pregnancy (36.0 ± 0.3 weeks) and 1 month after childbirth (32.6 ± 5.6 days).

Open in a separate window

Flow diagram of the participants.

Table 1

Demographic differences of participants.

| Total | |

|---|---|

| (N* = 201) | |

| Age (years) | 30.9 ± 4.5 |

| Height (cm) | 158.5 ± 5.7 |

| Body mass index before pregnancy (kg/m2) | 21. 0 ± 2.8 0 ± 2.8 |

| Weight before the pregnancy (kg) | 52.8 ± 7.5 |

| Weight at 12 weeks of pregnancy (kg) | 53.2 ± 7.6 |

| Weight at 24 weeks of pregnancy (kg) | 57.4 ± 7.4 |

| Weight at 30 weeks of pregnancy (kg) | 60.1 ± 7.6 |

| Weight at 36 weeks of pregnancy (kg) | 62.5 ± 7.5 |

| Weight at 1 month after childbirth (kg) | 56.3 ± 7.6 |

| Percentages of women with previous deliveries (%) | |

| Primipara | 43. 3 (N = 87) 3 (N = 87) |

| Second child | 38.8 (N = 78) |

| Third child | 14.9 (N = 30) |

| Fourth child | 2.0 (N = 4) |

| Fifth child | 0.5 (N = 1) |

| Sixth child | 0.5 (N = 1) |

| Percentage of people per method of childbirth | |

| Normal spontaneous vaginal delivery | 81.1 (N = 163) |

| Forceps delivery | 3. 0 (N = 6) 0 (N = 6) |

| Vacuum extraction delivery | 2.5 (N = 5) |

| Caesarean section | 11.9 (N = 24) |

| Epidural childbirth | 1.5 (N = 3) |

Open in a separate window

Age, Height, and Weight: Values are shown as mean ± standard deviation.

* N represents number of persons.

The data other than anterior width of the pelvis in 12, 30 and 36 weeks of pregnancy did not follow a normal distribution. Thus, the Friedman test as a non-parametric test with Bonferroni correction was conducted.

According to the Friedman test, pelvic alignment was significantly changed during pregnancy and after childbirth (). The anterior width of the pelvis became significantly wider throughout the pregnancy period (12 vs. 24 weeks: 23.1 ± 2.8 cm vs. 24.0 ± 3.2 cm, respectively; p < 0.001, 24 vs. 30 weeks: 24.0 ± 3.2 cm vs. 24.8 ± 2.5 cm, respectively; p = 0.014, 30 vs. 36 weeks: 24.8 ± 2.5 cm vs. 25.4 ± 2.5 cm, respectively; p = 0.026) (). One month after childbirth, the anterior width of the pelvis was significantly narrower compared with week 24 (23.6 ± 3.1 cm vs. 24.0 ± 3.2 cm, respectively; p = 0.043), 30 (23.6 ± 3.1 cm vs. 24.8 ± 2.5 cm, respectively; p < 0.001) and 36 of pregnancy (23.6 ± 3.1 cm vs. 25.4 ± 2.5 cm, respectively; p < 0.001). On the other hand, the anterior pelvic width at one month post-delivery was significantly wider than that at 12 weeks of pregnancy (23.6 ± 3.1 cm vs. 23.1 ± 2.8 cm, respectively; p = 0.009).

24 weeks: 23.1 ± 2.8 cm vs. 24.0 ± 3.2 cm, respectively; p < 0.001, 24 vs. 30 weeks: 24.0 ± 3.2 cm vs. 24.8 ± 2.5 cm, respectively; p = 0.014, 30 vs. 36 weeks: 24.8 ± 2.5 cm vs. 25.4 ± 2.5 cm, respectively; p = 0.026) (). One month after childbirth, the anterior width of the pelvis was significantly narrower compared with week 24 (23.6 ± 3.1 cm vs. 24.0 ± 3.2 cm, respectively; p = 0.043), 30 (23.6 ± 3.1 cm vs. 24.8 ± 2.5 cm, respectively; p < 0.001) and 36 of pregnancy (23.6 ± 3.1 cm vs. 25.4 ± 2.5 cm, respectively; p < 0.001). On the other hand, the anterior pelvic width at one month post-delivery was significantly wider than that at 12 weeks of pregnancy (23.6 ± 3.1 cm vs. 23.1 ± 2.8 cm, respectively; p = 0.009).

Open in a separate window

Change of pelvic alignment during and after pregnancy.

There were no significant differences in the posterior width of the pelvis between weeks 12 and 24 (10. 7 ± 3.6 cm vs. 11.2 ± 3.7 cm, respectively; p = 0.403), 24 and 30 (11.2 ± 3.7 cm vs. 11.4 ± 3.3 cm, respectively; p = 1.00), and 30 and 36 (11.4 ± 3.3 cm vs. 11.7 ± 3.5 cm, respectively; p = 1.00) (). The increase in posterior width was significant between weeks 12 and 30 (10.7 ± 3.6 cm vs. 11.4 ± 3.3 cm, respectively; p = 0.034) and between 12 and 36 (10.7 ± 3.6 cm vs. 11.7 ± 3.5 cm, respectively; p < 0.001). At 1 month after childbirth, there was no significant difference in the posterior width of the pelvis compared with that during pregnancy.

7 ± 3.6 cm vs. 11.2 ± 3.7 cm, respectively; p = 0.403), 24 and 30 (11.2 ± 3.7 cm vs. 11.4 ± 3.3 cm, respectively; p = 1.00), and 30 and 36 (11.4 ± 3.3 cm vs. 11.7 ± 3.5 cm, respectively; p = 1.00) (). The increase in posterior width was significant between weeks 12 and 30 (10.7 ± 3.6 cm vs. 11.4 ± 3.3 cm, respectively; p = 0.034) and between 12 and 36 (10.7 ± 3.6 cm vs. 11.7 ± 3.5 cm, respectively; p < 0.001). At 1 month after childbirth, there was no significant difference in the posterior width of the pelvis compared with that during pregnancy.

The anterior pelvic tilt increased during pregnancy and had decreased by one month after childbirth. There were significant differences between 12 and 36 weeks of pregnancy (3.99 ± 5.53° vs. 5.29 ± 5.33°, respectively; p = 0.037) (). Some pelvic asymmetry was observed throughout the investigational period (). The asymmetry increased slightly during pregnancy, but the difference during pregnancy and after childbirth was not significant.

The current study investigated the changes in pelvic alignment during pregnancy and one month after childbirth. The results document continuous changes in pelvic alignment during this period.

Specifically, both the anterior and posterior pelvic joints continually open during pregnancy. The pelvis is known to open due to joint relaxation and swelling of the abdomen with fetal growth during pregnancy [1,21]. Although this opening is necessary for fetal growth and delivery, pelvic recovery after childbirth is required to avoid future problems such as pelvic organ prolapse [22]. According to our results, recovery is not complete even at 1 month after childbirth. The anterior width of the pelvis may be slower to recover than the posterior width. Generally, it is desirable that the anterior and posterior recover simultaneously in order to avoid body dysfunction. For example, instability of the pubic symphysis is a severe symptom that may require surgery [23]. The widening of the pelvis after childbirth might be related to pelvic organ prolapse [24]. Thus, various pelvic belts are used to augment pelvic stability via external compression and additional closure forces in lumbopelvic disorders where stability is compromised [25–27]. Moreover, the widening of the anterior pelvis itself is sometimes the cause of pelvic dysfunction such as a gapping joint [28]. To make matters worse, these pelvic dysfunctions caused by pregnancy continue long term as chronic pelvic or low back pain [29]. Therefore, we especially need to promote recovery in the anterior width of the pelvis after childbirth in order to reduce and prevent long-lasting disorders that lower the quality of life beyond the perinatal period.

Thus, various pelvic belts are used to augment pelvic stability via external compression and additional closure forces in lumbopelvic disorders where stability is compromised [25–27]. Moreover, the widening of the anterior pelvis itself is sometimes the cause of pelvic dysfunction such as a gapping joint [28]. To make matters worse, these pelvic dysfunctions caused by pregnancy continue long term as chronic pelvic or low back pain [29]. Therefore, we especially need to promote recovery in the anterior width of the pelvis after childbirth in order to reduce and prevent long-lasting disorders that lower the quality of life beyond the perinatal period.

Our results support the general consensus that the pelvis tilts forward with pregnancy progress and does not fully recover after childbirth. Forward pelvic tilting is a risk factor for low back and pelvic pain during pregnancy [15]. According to our results, clinicians and researchers need to pay attention to pain caused by pelvic tilting, especially in late pregnancy because the pelvic tilt was significantly larger than that seen at 12 weeks of pregnancy. Recently, pelvic asymmetry is gaining attention for its relationship to some physical disorders such as pelvic pain [30, 31]. According to the results of the current study, pelvic asymmetry does not change significantly during and after pregnancy. However, asymmetry of pelvic alignment does exist, and cannot be ignored during the perinatal period when elasticity of the joints increases [7]. Further investigation with more participants is needed to assess the pelvic changes in women who experience pelvic asymmetry during and after pregnancy.

Recently, pelvic asymmetry is gaining attention for its relationship to some physical disorders such as pelvic pain [30, 31]. According to the results of the current study, pelvic asymmetry does not change significantly during and after pregnancy. However, asymmetry of pelvic alignment does exist, and cannot be ignored during the perinatal period when elasticity of the joints increases [7]. Further investigation with more participants is needed to assess the pelvic changes in women who experience pelvic asymmetry during and after pregnancy.

There were several limitations to the current study. First, the measurement of pelvic alignment of the participant was sometimes conducted by same measurer. Thus, the measurer might have remembered and been influenced by the previous result. Second, the timing of the measurements was not at equal intervals because visits were scheduled to coincide with the standard Japanese health checkups for pregnant women. Pre-pregnancy evaluations could not be standardized, and longer term follow-up after childbirth is necessary to fully assess pelvic recovery time. In addition, other factors that may affect pelvic alignment, such as the level of pregnancy-related hormones, daily activity, and job, were not investigated. However, despite these limitations, the changes in pelvic alignment during pregnancy and one month after childbirth were documented in this study. The cut-off value for recognizing pelvic alignment as abnormal has not been established. Thus, the current study was conducted to determine a reference value for abnormal pelvic alignment. Unfortunately, the data may not be sufficient for deciding the cut-off values. However, if the change of the pelvic alignment was markedly different from the results of the present study, it might be abnormal. Furthermore, future studies with a larger number of participants that limit the participants to being either primigravid or multigravid will provide more useful information. This is one of the few studies that have shown perinatal changes in pelvic alignment, and the results may help healthcare providers to prevent and treat complications due to pelvic opening, misalignment, and delayed postnatal recovery.

In addition, other factors that may affect pelvic alignment, such as the level of pregnancy-related hormones, daily activity, and job, were not investigated. However, despite these limitations, the changes in pelvic alignment during pregnancy and one month after childbirth were documented in this study. The cut-off value for recognizing pelvic alignment as abnormal has not been established. Thus, the current study was conducted to determine a reference value for abnormal pelvic alignment. Unfortunately, the data may not be sufficient for deciding the cut-off values. However, if the change of the pelvic alignment was markedly different from the results of the present study, it might be abnormal. Furthermore, future studies with a larger number of participants that limit the participants to being either primigravid or multigravid will provide more useful information. This is one of the few studies that have shown perinatal changes in pelvic alignment, and the results may help healthcare providers to prevent and treat complications due to pelvic opening, misalignment, and delayed postnatal recovery.

In the current longitudinal study, the changes in pelvic alignment during and after pregnancy were investigated. The results demonstrated that both the anterior and posterior width of the pelvis become significantly wider with pregnancy progress. The anterior width of the pelvis is not recovered at 1 month after childbirth, and it is still wider than that at 12 weeks of pregnancy. The anterior pelvic tilt increases during pregnancy, and especially from 12 weeks to 36 weeks of pregnancy, and then decreases 1 month after childbirth. Pelvic asymmetry was found to be present throughout during pregnancy and after childbirth, though no significant change observed. From the results of the current study, the average values and changes of pelvic alignment throughout the perinatal period were revealed. The data of the women that could have had special effects on pelvic alignment were excluded in the present study. Although it is difficult to declare the cut-off values, the data of the current study might be useful as a reference to check the change of the pelvic alignment in perinatal periods. If the trend of change of pelvic alignment of a pregnant woman was clearly different from the data of this study, the approach for reforming the alignment is still useful for avoiding perinatal related dysfunction. Consequently these details on pelvic alignment during and after pregnancy might be useful for assessing the perinatal risk of lumbopelvic disorders in women and for developing appropriate treatments for pelvic misalignment based on the time when any alignment changes occur.

If the trend of change of pelvic alignment of a pregnant woman was clearly different from the data of this study, the approach for reforming the alignment is still useful for avoiding perinatal related dysfunction. Consequently these details on pelvic alignment during and after pregnancy might be useful for assessing the perinatal risk of lumbopelvic disorders in women and for developing appropriate treatments for pelvic misalignment based on the time when any alignment changes occur.

S1 File

STROBE Statement.

Checklist of items that should be included in reports of cohort studies.

(DOC)

Click here for additional data file.(90K, doc)

S2 File

Questionnaire.

A copy of the questionnaire used, both in English and in Japanese.

(DOC)

Click here for additional data file.(59K, doc)

We especially appreciate the participant’s cooperation. This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number 15J07748, 18H05962. JSPS is an independent administrative institution, established by way of a national law for the purpose of contributing to the advancement of science in all fields of the natural and social sciences and the humanities (https://www.jsps.go.jp/english/). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number 15J07748, 18H05962. JSPS is an independent administrative institution, established by way of a national law for the purpose of contributing to the advancement of science in all fields of the natural and social sciences and the humanities (https://www.jsps.go.jp/english/). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number 15J07748, 18H05962 to SM. JSPS is an independent administrative institution, established by way of a national law for the purpose of contributing to the advancement of science in all fields of the natural and social sciences and the humanities (https://www.jsps.go.jp/english/). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Kishokai Medical Corporation support in the form of salaries for authors [FU, HH and MY], but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The specific roles of these authors are articulated in the ‘author contributions’ section.

Kishokai Medical Corporation support in the form of salaries for authors [FU, HH and MY], but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The specific roles of these authors are articulated in the ‘author contributions’ section.

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

1. Borg-Stein J, Dugan SA. Musculoskeletal disorders of pregnancy, delivery and postpartum. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2007;18: 459–476. 10.1016/j.pmr.2007.05.005 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Liddle SD, Pennick V. Interventions for preventing and treating low-back and pelvic pain during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9 10.1002/14651858.CD001139.pub4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Sipko T, Grygier D, Barczyk K, Eliasz G. The occurrence of strain symptoms in the lumbosacral region and pelvis during pregnancy and after childbirth. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33: 370–377. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.05.006 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33: 370–377. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.05.006 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Snijders CJ, Vleeming A, Stoeckart R. Transfer of lumbosacral load to iliac bones and legs Part 2: Loading of the sacroiliac joints when lifting in a stooped posture. Clin Biomech. 1993;8: 295–301. 10.1016/0268-0033(93)90003-Z [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 548: weight gain during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121: 210–212. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000425668.87506.4c [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Kharrazi FD, Rodgers WB, Kennedy JG, Lhowe DW. Parturition-induced pelvic dislocation: a report of four cases. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11: 277–81; discussion 281–282. 10.1097/00005131-199705000-00009 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Schauberger CW, Rooney BL, Goldsmith L, Shenton D, Silva PD, Schaper A. Peripheral joint laxity increases in pregnancy but does not correlate with serum relaxin levels. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174: 667–671. 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70447-7 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174: 667–671. 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70447-7 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Franklin ME, Conner-Kerr T. An analysis of posture and back pain in the first and third trimesters of pregnancy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28: 133–138. 10.2519/jospt.1998.28.3.133 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Mitchell DA, Esler DM. Pelvic instability—Painful pelvic girdle in pregnancy. Aust Fam Physician. 2009;38: 409–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Morino S, Ishihara M, Umezaki F, Hatanaka H, Aoyama T, Yamashita M, et al. Pelvic alignment risk factors associated with sacroiliac joint pain during pregnancy. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2018;45: 850–4. 10.12891/ceog4268.2018 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Vleeming A, Stoeckart R, Volkers AC, Snijders CJ. Relation between form and function in the sacroiliac joint. Part II: biomechanical aspects. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1990;15: 133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Al-Eisa E, Egan D, Deluzio K, Wassersug R. Effects of pelvic skeletal asymmetry on trunk movement: three-dimensional analysis in healthy individuals versus patients with mechanical low back pain. Spine. 2006;31: E71–79. 10.1097/01.brs.0000197665.93559.04 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Effects of pelvic skeletal asymmetry on trunk movement: three-dimensional analysis in healthy individuals versus patients with mechanical low back pain. Spine. 2006;31: E71–79. 10.1097/01.brs.0000197665.93559.04 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. The Malalignment Syndrome. In: Schamberger W, editor. Implications for Medicine and Sport. London, Churchill Livingstone, 2002. p. 29. [Google Scholar]

14. Lee D, Lee L-J. Stress urinary incontinence–a consequence of failed load transfer through the pelvic girdle? The 5th World Interdisciplinary Congress on Low Back and Pelvic Pain; Melbourne, Australia 2004. p. 1–14.

15. Casagrande D, Gugala Z, Clark SM, Lindsey RW. Low Back Pain and Pelvic Girdle Pain in Pregnancy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23: 539–549. 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00248 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Urbankova I, Grohregin K, Hanacek J, Krcmar M, Feyereisl J, Deprest J, et al. The effect of the first vaginal birth on pelvic floor anatomy and dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2019. 10.1007/s00192-019-04044-2 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Int Urogynecol J. 2019. 10.1007/s00192-019-04044-2 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Gyhagen M, Akervall S, Molin M, Milsom I. The effect of childbirth on urinary incontinence: a matched cohort study in women aged 40–64 years. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2019. 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.05.022 . [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Yamaguchi M, Morino S, Nishiguchi S, Fukutani N, Tashiro Y. Comparison of Pelvic Alignment among Never-Pregnant Women, Pregnant Women, and Postpartum Women (Pelvic Alignment and Pregnancy). J Womens Health Care. 2016;5 10.4172/2167-0420.1000309 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Gnat R, Saulicz E, Biały M, Kłaptocz P. Does Pelvic Asymmetry always Mean Pathology? Analysis of Mechanical Factors Leading to the Asymmetry. J Hum Kinet. 2009;21: 23–32. 10.2478/v10078-09-0003-8 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Azevedo DC, Santos H, Carneiro RL, Andrade GT. Reliability of sagittal pelvic position assessments in standing, sitting and during hip flexion using palpation meter. J Bodywork Move Ther. 2014;18: 210–214. 10.1016/j.jbmt.2013.05.017 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J Bodywork Move Ther. 2014;18: 210–214. 10.1016/j.jbmt.2013.05.017 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. MacLennan AH. The role of the hormone relaxin in human reproduction and pelvic girdle relaxation. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl. 1991;88: 7–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Nygaard I. Pelvic floor recovery after childbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125: 529–530. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000705 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Arner JW, Albers M, Zuckerbraun BS, Mauro CS. Laparoscopic Treatment of Pubic Symphysis Instability With Anchors and Tape Suture. Arthrosc Tech. 2018;7:e23–e7. 10.1016/j.eats.2017.08.045 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Stein TA, Kaur G, Summers A, Larson KA, DeLancey JO. Comparison of bony dimensions at the level of the pelvic floor in women with and without pelvic organ prolapse. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2009;200:241 e1–5. 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.10.040 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Mens JM, Pool-Goudzwaard A, Stam HJ. Mobility of the pelvic joints in pregnancy-related lumbopelvic pain: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009;64: 200–208. 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181950f1b [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Mens JM, Pool-Goudzwaard A, Stam HJ. Mobility of the pelvic joints in pregnancy-related lumbopelvic pain: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009;64: 200–208. 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181950f1b [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Vleeming A, Buyruk HM, Stoeckart R, Karamursel S, Snijders CJ. An integrated therapy for peripartum pelvic instability: a study of the biomechanical effects of pelvic belts. American J obstet and gynec. 1992;166: 1243–1247. 10.1016/S0002-9378(11)90615-2 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Fishburn S. Pelvic girdle pain: updating current practice. Pract Midwife. 2015;18: 12–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Mens JM. Does a pelvic belt reduce hip adduction weakness in pregnancy-related posterior pelvic girdle pain? A case-control study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017; 53: 575–581. 10.23736/S1973-9087.17.04442-2 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Pedrazzini A, Bisaschi R, Borzoni R, Simonini D, Guardoli A. Post partum diastasis of the pubic symphysis: a case report. Acta Biomed. 2005;76: 49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Acta Biomed. 2005;76: 49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Elden H, Gutke A, Kjellby-Wendt G, Fagevik-Olsen M, Ostgaard HC. Predictors and consequences of long-term pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: a longitudinal follow-up study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016; 17: 276 10.1186/s12891-016-1154-0 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

31. Damen L, Buyruk HM, Guler-Uysal F, Lotgering FK, Snijders CJ, Stam HJ. Pelvic pain during pregnancy is associated with asymmetric laxity of the sacroiliac joints. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80: 1019–1024. 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.801109.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - pelvis

Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - pelvis | Pregnancy Birth and Baby beginning of content3-minute read

Listen

While everyone has a pelvis, the female pelvis differs from the male’s. Learn the anatomy of the female pelvis and how it undergoes unique changes to support pregnancy and childbirth.

Learn the anatomy of the female pelvis and how it undergoes unique changes to support pregnancy and childbirth.

What is the pelvis?

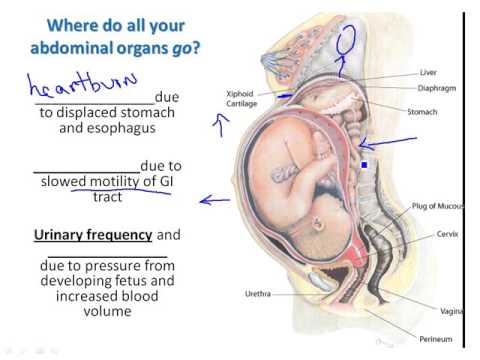

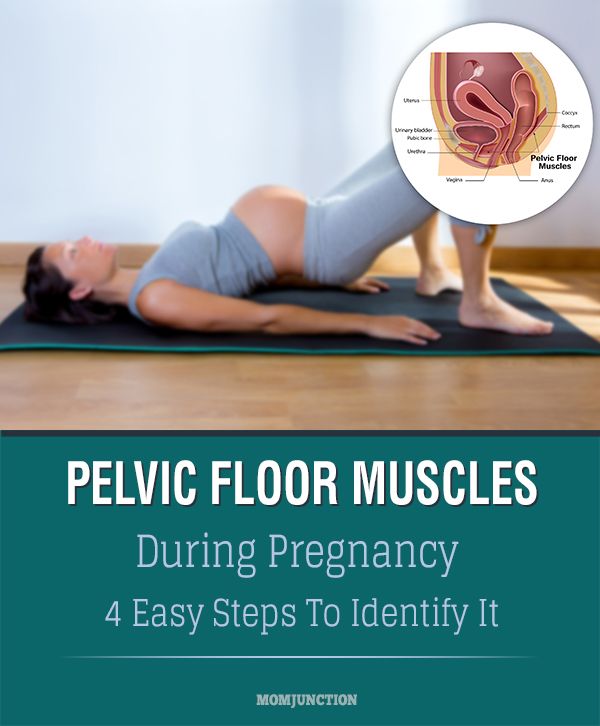

The pelvis is located in the middle of the human body, below the abdomen and above the thighs. It comprises the bony pelvis — which includes the hip bones —, pelvic cavity, pelvic floor, and perineum — the area of skin between the opening of the vagina and the anus. The bones around the pelvis are attached by several ligaments, comprised of tough and flexible tissue, and four joints. These help the pelvis to function.

What does the pelvis do?

The pelvis has many roles, including holding the body upright so you can stand, walk and run. Additionally, a woman’s pelvis, which is wider, more rounded and has thinner bones than a male’s, helps women through pregnancy and childbirth.

How does the pelvis change during pregnancy?

A pregnant woman’s pelvis changes through pregnancy. Its shape, position, and joint and ligament behaviour adjust to support the baby during pregnancy, making childbirth easier for both mother and baby. For example, a hormone named relaxin helps the pelvis relax during pregnancy and birth to accommodate the growing baby and to allow for an easier delivery.

For example, a hormone named relaxin helps the pelvis relax during pregnancy and birth to accommodate the growing baby and to allow for an easier delivery.

Pelvic pain — a common condition in pregnancy

While changes to a pregnant woman’s pelvis help facilitate pregnancy and birth, they can cause discomfort. For instance, when the joints of the pelvis relax, a pregnant mother can feel less stable on her feet, and she may feel discomfort in her pelvis and lower back pain.

The following approaches have been shown to reduce pregnancy-related pelvic pain:

- applying heat packs to painful areas

- wearing low-heeled shoes

- avoid standing on one leg (sit down to get dressed, climb stairs one at a time)

- seeing a physiotherapist for exercise and posture advice

- avoiding standing or walking for long periods of time

- being careful about movements that stretch the hip, such as getting in and out of cars, sitting on low stools and squatting

Although very rare, other injuries to the pelvis can occur during pregnancy and childbirth, including fractures. A pelvic injury such as a fracture requires prompt medical attention.

A pelvic injury such as a fracture requires prompt medical attention.

The pelvis and childbirth

For birth, a baby should ideally be positioned with their head down and facing the mother’s back. This position helps the baby descend through the pelvis and birth canal.

A baby who lies bottom or feet down in the pelvis during late pregnancy is said to be in breech position. Breech presentations increase the chance of a complicated vaginal birth and can lead to a caesarean section. While most babies naturally turn in the womb in time for labour, techniques performed by an obstetrician, such as an external cephalic version (ECV), can help the baby to turn.

Most babies naturally get into the 'head down' position in time for labour and birth. Certain positions for birth can help guide the baby down through the pelvis. For example, staying upright during contractions means that gravity is working to help the baby transition through the pelvis, and along the birth canal.

There are other ways to take advantage of the structure and function of the pelvis to assist in childbirth. Read more about positions for labour and birth.

Sources:

StatPearls Publishing (Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis), Department of Health (Pregnancy Care Guidelines), Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (Breech Presentation at the End of your Pregnancy), King Edward Memorial Hospital (Pregnancy, birth and your baby), Journal of Orthopedics, Traumatology and Rehabilitation (2014) (Pelvic trauma in women of reproductive age), European Spine Journal (Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain and its relationship with relaxin levels during pregnancy)Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Last reviewed: October 2020

Back To Top

Related pages

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - uterus

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - perineum and pelvic floor

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - cervix

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - abdominal muscles

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth

Need further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Video call

- Contact us

- About us

- A-Z topics

- Symptom Checker

- Service Finder

- Linking to us

- Information partners

- Terms of use

- Privacy

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is funded by the Australian Government and operated by Healthdirect Australia.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is provided on behalf of the Department of Health

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby’s information and advice are developed and managed within a rigorous clinical governance framework. This website is certified by the Health On The Net (HON) foundation, the standard for trustworthy health information.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

Pain in the pubic region during pregnancy

Subscribe to our Instagram! Useful information about pregnancy and childbirth from leading obstetricians and gynecologists in Moscow and foreign experts: https://www.instagram.com/roddompravda/

Tips and opinions from leading child professionals: https://www. instagram.com/emc.child/

instagram.com/emc.child/

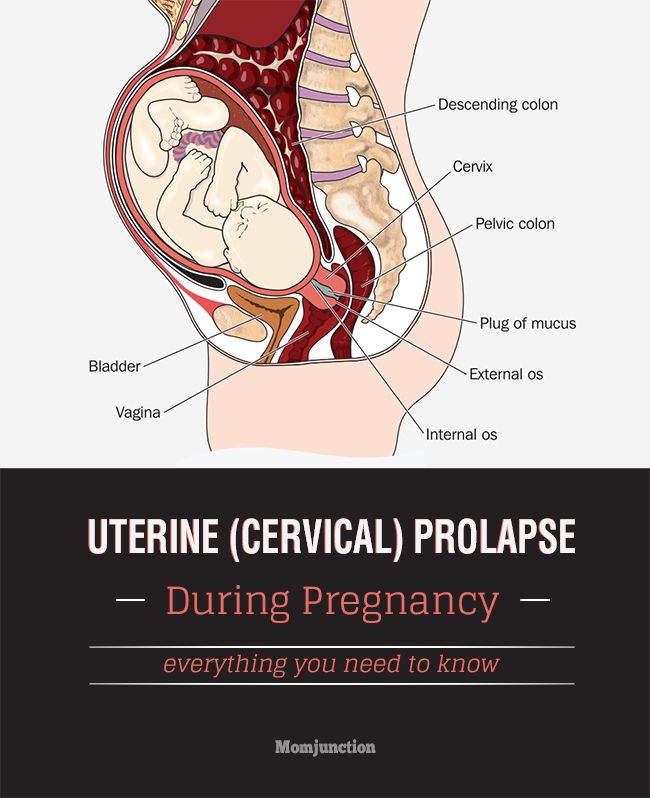

The pubic bone is one of the three bones that make up the pelvic bone. Two pubic bones, forming the pubic articulation (symphysis), form the anterior wall of the pelvis. The pubic bone in women with a regular physique has the form of a roller about the thickness of the thumb, which is curved and forms a pubic eminence. This bone hangs in a kind of arch over the entrance to the vagina.

The main cause of pain in the pubic bone is the divergence and increased mobility of the pubic symphysis. To refer to pathological changes in the pubic symphysis of the pelvis during pregnancy and after childbirth, the following terms are used: symphysiopathy, symphysitis, arthropathy of pregnant women, divergence and rupture of the pubic symphysis, dysfunction of the pubic symphysis. The most commonly used terms are "symphysitis" or "symphysiopathy".

So, symphysiopathy is a disease associated with a pronounced softening of the pubic joint under the influence of the hormone relaxin, which is produced during pregnancy. The process of softening the interosseous joints is natural, it helps the child to pass more easily through the bone pelvis during childbirth. The diagnosis of "symphysiopathy" is made when severe pain appears, the pubic joint swells, greatly stretches, becomes mobile, and the pubic bones diverge excessively. One of the striking, characteristic symptoms of this pathology is that it is impossible to raise the leg in the prone position. In addition to acute pain in the pubis, there are difficulties when walking up the stairs, it becomes difficult to turn from side to side on the bed and get up from the sofa, and the gait changes and becomes like a "duck". According to most doctors, the cause of symphysiopathy is a lack of calcium, an increased concentration of the hormone relaxin, and increased physical activity on the bones of the pelvic region. In addition, the development of symphysiopathy can be provoked by a serious sports injury or a fracture of the pelvic bones.

The process of softening the interosseous joints is natural, it helps the child to pass more easily through the bone pelvis during childbirth. The diagnosis of "symphysiopathy" is made when severe pain appears, the pubic joint swells, greatly stretches, becomes mobile, and the pubic bones diverge excessively. One of the striking, characteristic symptoms of this pathology is that it is impossible to raise the leg in the prone position. In addition to acute pain in the pubis, there are difficulties when walking up the stairs, it becomes difficult to turn from side to side on the bed and get up from the sofa, and the gait changes and becomes like a "duck". According to most doctors, the cause of symphysiopathy is a lack of calcium, an increased concentration of the hormone relaxin, and increased physical activity on the bones of the pelvic region. In addition, the development of symphysiopathy can be provoked by a serious sports injury or a fracture of the pelvic bones.

At what stage of pregnancy do they occur?

The disease begins gradually or suddenly during pregnancy, childbirth or after childbirth. Most often, women begin to feel pain in the area of the pubic joint in the third trimester of pregnancy. This is due to the fact that the places of adhesions of the pubic bones, their ligaments and cartilage, soften under the influence of the hormone relaxin. This hormone of pregnancy naturally softens the bony joints, which is necessary to facilitate the passage of the child's bone pelvis and birth canal at the time of childbirth.

Most often, women begin to feel pain in the area of the pubic joint in the third trimester of pregnancy. This is due to the fact that the places of adhesions of the pubic bones, their ligaments and cartilage, soften under the influence of the hormone relaxin. This hormone of pregnancy naturally softens the bony joints, which is necessary to facilitate the passage of the child's bone pelvis and birth canal at the time of childbirth.

Some women begin to complain of pain in the pelvic bones some time after giving birth. This may be the result of traumatic childbirth (imposition of obstetrical forceps, shoulder dystocia, excessive separation of the hips during childbirth, etc.) or physical exertion (lifting a heavy baby stroller up the stairs, prolonged motion sickness in the arms of a well-fed baby, etc.). It is recommended to limit physical activity, wear an orthopedic bandage, consult a traumatologist. Complaints usually recur after the next pregnancy. In a small proportion of patients, pain persists for a long time.

When can this be considered the norm, and when not?

Obstetricians-gynecologists do not consider a slight soreness of the pubic joint to be a pathology, but if the pain is acute, restricting the movements of the pregnant woman, accompanied by edema, then we can talk about pathology. Pain can be quite strong and especially manifest itself while walking, turning the body to the right and left in a sitting position and even lying down. In this case, you need to urgently consult a doctor and undergo an ultrasound diagnosis (ultrasound) to determine the size of the divergence of the pubic bones. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also used, which allows assessing the state of the symphysis, the state of the bone tissue, as well as soft tissues.

With ultrasound, the degree of divergence (diastasis) of the pubic bones is determined. The severity of the clinical picture largely depends on the degree of divergence of the pubic bones, and therefore there are three degrees of divergence of the pubic branches: in the first degree - by 6-9 mm, in the second - by 10-20 mm, in the third - more than 20 mm. The severity of the symptoms of the disease varies from mild discomfort to unbearable pain.

The severity of the symptoms of the disease varies from mild discomfort to unbearable pain.

How can pain be relieved?

There are some recommendations that will help reduce bone pain during pregnancy, if the cause of its occurrence is the divergence of the pubic bones. Be sure to wear a bandage, especially in later pregnancy. The bandage takes on most of the load, thereby releasing pressure from the pubic joint. Limitation of heavy physical exertion is indicated for any manifestations of pain, lying down more often, walking less and being in a sitting position for no longer than 30-40 minutes. In severe cases, before and sometimes after childbirth, a woman may be shown strict bed rest. Moreover, the bed should not be hard and flat.

Since the appearance of symphysiopathy is associated not only with a large production of the hormone relaxin, but also with a lack of calcium in the body, the expectant mother is prescribed calcium preparations and complex vitamins for pregnant women, which contain all the necessary vitamins and trace elements in the right amount and proportions. There is evidence that pain is reduced during acupuncture and physiotherapy.

There is evidence that pain is reduced during acupuncture and physiotherapy.

In especially severe cases of symphysiopathy, the pregnant woman is hospitalized.

What is the danger of this condition?

The occurrence of symphysiopathy is due to several reasons. This is a lack of calcium in the body of the future mother, and an excess amount of the hormone relaxin, and the individual structural features of the woman's body, and possible hereditary or acquired problems of the musculoskeletal system.

With an unexpressed clinical picture of the disease, with an expansion of the pubic fissure up to 10 mm, normal pelvic sizes, a small fetus, childbirth can be carried out through the birth canal, avoiding the use of physical force, such as the Christeller maneuver. With a pronounced stretching of the pubic symphysis, pain syndrome, especially with anatomical narrowing of the pelvis, a large fetus, there is a danger of rupture of the pubic symphysis, and the method of choice in this case is caesarean section. This is due to the fact that during natural delivery, the bones can disperse even more and the woman subsequently will not be able to walk at all.

This is due to the fact that during natural delivery, the bones can disperse even more and the woman subsequently will not be able to walk at all.

Prevention

The body of a healthy woman is able to independently cope with all the difficulties of the pregnancy period. First of all, the expectant mother should include enough foods containing calcium in her diet, as well as take vitamins for pregnant women.

For the prevention of symphysiopathy, the use of a prenatal bandage is recommended, which supports the abdomen and prevents excessive stretching of the ligaments and muscles. Prophylactic antenatal bandage is usually recommended from 25 weeks of gestation, when the abdomen begins to actively grow.

In order to ensure the plasticity of the ligaments and muscles, as well as the flexibility of the joints, special exercises must be done even during the planning of pregnancy. Yoga gives good results.

Narrow pelvis during pregnancy (childbirth): causes, types

Until the 16th century, it was believed that the pelvic bones diverge during childbirth, and the fetus is born, resting its legs against the bottom of the uterus. In 1543, the anatomist Vesalius proved that the bones of the pelvis were fixed, and doctors turned their attention to the problem of a narrow pelvis.

In 1543, the anatomist Vesalius proved that the bones of the pelvis were fixed, and doctors turned their attention to the problem of a narrow pelvis.

Despite the fact that recently gross deformities of the pelvis and high degrees of its narrowing are rare, the problem of a narrow pelvis has not lost its relevance today due to the acceleration and increase in body weight of newborns.

Causes

Narrowing or deformity of the pelvis can be caused by:

- congenital anomalies of the pelvis,

- childhood malnutrition,

- diseases suffered in childhood: rickets, poliomyelitis, etc.

- diseases or injuries of bones and joints of the pelvis: fractures, tumors, tuberculosis.

- spinal deformities (kyphosis, scoliosis, coccyx deformity).

- One of the factors in the formation of a transversely narrowed pelvis is acceleration, which during puberty leads to a rapid growth of the body in length while lagging behind the growth of transverse dimensions.

Species

Anatomically narrow is a pelvis in which at least one of the main dimensions (see below) is 1.5-2 cm or more smaller than normal.

However, it is not the dimensions of the pelvis that are most important, but the ratio of these dimensions to the dimensions of the fetal head. If the fetal head is small, then even with some narrowing of the pelvis, there may not be any discrepancy between it and the head of the child being born, and childbirth occurs naturally without any complications. In such cases, the anatomically narrowed pelvis is functionally sufficient.

Complications in childbirth can also occur with normal pelvic sizes - in cases where the fetal head is larger than the pelvic ring. In such cases, the movement of the head through the birth canal stops: the pelvis is practically narrow, functionally insufficient. Therefore, there is such a thing as0003 clinically (or functionally) narrow pelvis . Clinically narrow pelvis is an indication for caesarean section in childbirth.

True anatomically narrow pelvis occurs in 5-7% of women. The diagnosis of a clinically narrow pelvis is established only in childbirth on the basis of a combination of signs that make it possible to identify the disproportion of the pelvis and head. This type of pathology occurs in 1-2% of all births.

How is the pelvis measured?

In obstetrics, the study of the pelvis is very important, since its structure and size are decisive for the course and outcome of childbirth. The presence of a normal pelvis is one of the main conditions for the correct course of childbirth.

Deviations in the structure of the pelvis, especially a decrease in its size, complicate the course of natural childbirth, and sometimes represent insurmountable obstacles for them. Therefore, when registering a pregnant woman with a antenatal clinic and upon admission to a maternity hospital, in addition to other examinations, it is imperative to measure the external dimensions of the pelvis. Knowing the shape and size of the pelvis, it is possible to predict the course of childbirth, possible complications, and make a decision on the admissibility of spontaneous childbirth.

Knowing the shape and size of the pelvis, it is possible to predict the course of childbirth, possible complications, and make a decision on the admissibility of spontaneous childbirth.

Pelvic examination includes examination, palpation of the bones and measurement of the pelvis.

In a standing position, examine the so-called lumbosacral rhombus, or Michaelis rhombus (Fig. 1). Normally, the vertical size of the rhombus is on average 11 cm, the transverse size is 10 cm. In case of violation of the structure of the small pelvis, the lumbosacral rhombus is not clearly expressed, its shape and dimensions are changed.

After palpation of the pelvic bones, it is measured using a pelvis meter (see Fig. 2a and b).

Basic measurements of the pelvis:

- Interosseous size. The distance between the superior anterior iliac spines ([1] in Fig. 2a) is normally 25-26 cm.

- The distance between the most distant points of the iliac crests ([2] in Fig.

2a) is 28-29 cm, between the greater trochanters of the femur ([3] in Fig. 2a) is 30-31 cm.

2a) is 28-29 cm, between the greater trochanters of the femur ([3] in Fig. 2a) is 30-31 cm. - External conjugate - the distance between the supra-sacral fossa (the upper corner of the Michaelis rhombus) and the upper edge of the pubic symphysis (Fig. 2b) - 20-21 cm.

The first two measurements are measured with the woman lying on her back with her legs extended and moved together; the third size is measured with the legs shifted and slightly bent. The external conjugate is measured with the woman lying on her side with the lower leg bent at the hip and knee joints and the overlying leg extended.

Some pelvic measurements are determined during a vaginal examination.

When determining the size of the pelvis, it is necessary to take into account the thickness of its bones, it is judged by the value of the so-called Solovyov index - the circumference of the wrist joint. The average value of the index is 14 cm.

If the Solovyov index is greater than 14 cm, it can be assumed that the pelvic bones are massive and the size of the small pelvis is smaller than expected. If it is necessary to obtain additional data on the size of the pelvis, its compliance with the size of the fetal head, deformation of the bones and their joints, an x-ray examination of the pelvis is performed. But it is made only under strict indications. The size of the pelvis and its correspondence to the size of the head can also be judged by the results of an ultrasound examination.

If it is necessary to obtain additional data on the size of the pelvis, its compliance with the size of the fetal head, deformation of the bones and their joints, an x-ray examination of the pelvis is performed. But it is made only under strict indications. The size of the pelvis and its correspondence to the size of the head can also be judged by the results of an ultrasound examination.

Influence of a narrow pelvis on the course of pregnancy and childbirth

The adverse effect of a narrowed pelvis on the course of pregnancy is felt only in its last months. The fetal head does not descend into the small pelvis, the growing uterus rises up and makes breathing much more difficult. Therefore, shortness of breath appears early at the end of pregnancy, it is more pronounced than during pregnancy with a normal pelvis.

In addition, a narrow pelvis often leads to an incorrect position of the fetus - transverse or oblique. In 25% of women in labor with a transverse or oblique position of the fetus, there is usually a pronounced narrowing of the pelvis to one degree or another. Breech presentation of the fetus in parturient women with a narrowed pelvis occurs three times more often than in parturient women with a normal pelvis.

Breech presentation of the fetus in parturient women with a narrowed pelvis occurs three times more often than in parturient women with a normal pelvis.

Management of pregnancy and childbirth with a narrow pelvis

Pregnant women with a narrow pelvis are at high risk for the development of complications, and in the antenatal clinic should be specially registered. Early detection of fetal position anomalies and other complications is necessary. It is important to accurately determine the term of childbirth in order to prevent over-pregnancy, which is especially unfavorable with a narrow pelvis. 1-2 weeks before delivery, pregnant women with a narrow pelvis are recommended to be hospitalized in the pathology department to clarify the diagnosis and choose a rational method of delivery.

The course of childbirth with a narrow pelvis depends on the degree of narrowing of the pelvis. With a slight narrowing, medium and small size of the fetus, births through the natural birth canal are possible . During childbirth, the doctor carefully monitors the function of the most important organs, the nature of the labor forces, the condition of the fetus and the degree of correspondence between the head of the fetus and the pelvis of the woman in labor, and, if necessary, promptly resolves the issue of a caesarean section.

During childbirth, the doctor carefully monitors the function of the most important organs, the nature of the labor forces, the condition of the fetus and the degree of correspondence between the head of the fetus and the pelvis of the woman in labor, and, if necessary, promptly resolves the issue of a caesarean section.

Absolute indication for caesarean section is:

- anatomically narrow pelvis III-IV degree of narrowing;

- the presence of bone tumors in the pelvis, preventing the passage of the fetus;

- severe pelvic deformities as a result of trauma or disease;

- ruptures of the pubic symphysis or other injuries of the pelvis that occurred during previous births.

In addition, the combination of a narrow pelvis with:

- large fetal size,

- post-pregnancy,

- chronic fetal hypoxia,

- breech presentation,

- anomalies in the development of the genital organs,

- uterine scar after caesarean section and other operations,

- indicating the presence of infertility in the past,

- nulliparous older than 30, etc.

Caesarean section is performed at the end of pregnancy before or with the onset of labor.

References

- Chi P., Wang XJ. [Significance of the intact of the fascia propria in protection of pelvic plexus during total mesorectal excision]. // Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi - 2021 - Vol24 - N4 - p.297-300; PMID:33878817

- Shih HS., Winstein CJ., Kulig K. Young adults with recurrent low back pain demonstrate altered trunk coordination during gait independent of pain status and attentional demands. // Exp Brain Res - 2021 - Vol - NNULL - p.; PMID:33871659

- Carannante F., Bianco G., Lauricella S., Mascianà G., Caricato M., Capolupo GT. TaTME approach as a rescue during a laparoscopic TME for high rectal cancer. A case report. // Int J Surg Case Rep - 2021 - Vol82 - NNULL - p.105870; PMID:33857768

- Baek SJ., Piozzi GN., Kim SH. Optimizing outcomes of colorectal cancer surgery with robotic platforms. // Surg Oncol - 2021 - Vol37 - NNULL - p.

101559; PMID:33839441

101559; PMID:33839441 - Shimizu J., Iba K., Emori M., Sasaki M., Yamashita T. Reconstruction Using Free Vascularized Fibular Grafts after Wide Resection of Humerus Chondrosarcoma in a Patient with Cleidocranial Dysplasia. // Case Rep Orthop - 2021 - Vol2021 - NNULL - p.2302879; PMID:33747589

- Del Gutiérrez Delgado MP., Mera Velasco S., Turiño Luque JD., González Poveda I., Ruiz López M., Santoyo Santoyo J. Outcomes of robotic-assisted vs conventional laparoscopic surgery among patients undergoing resection for rectal cancer: an observational single hospital study of 300 cases. // J Robot Surg - 2021 - Vol - NNULL - p.; PMID:33743145

- Flynn J., Larach JT., Kong JCH., Warrier SK., Heriot A. Robotic versus laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. // Int J Colorectal Dis - 2021 - Vol - NNULL - p.; PMID:33718972

- Ziati J., Souadka A., Benkabbou A., Boutayeb S., Ahmadi B., Amrani L., Mohsine R., Anass Majbar M. Transanal total mesorectal excision for patients with rectal cancer : a Systematic review and meta-analysis .