How to help an antisocial child

Helping Your Child Move from Anti-Social to Pro-Social Behaviors

Contributed by:

Allison Davis Maxon, LMFT

We all enter the world ready to attach because this is how we get our most basic and primary needs met. The human infant, like other high functioning mammals, is completely dependent on their primary caregivers to get all of their needs met—survival, safety, food, shelter, stimulation, comfort. For us to understand where some of our children’s most challenging behaviors come from, we must first realize just how much neglect and trauma affect every aspect of a child’s development. We are social-emotional beings with an innate need to connect and form meaningful attachment relationships. Every interpersonal skill required for us to be successful in creating and sustaining these relationships must be learned.

Trauma and the Developing Child

Trauma, neglect, and multiple disruptions in attachment relationships have a significant negative impact on a child’s ability to learn appropriate interpersonal skills. In fact, many children who have had these experiences develop defensive strategies to avoid interpersonal relationships. The relationship challenges then result in the children remaining in high states of chronic distress where they are unable to get their most basic and primary needs for connection and attachment met. It is important to note that it is through the primary parent/child attachment relationship that children become pro-socialized. Humans have an extended childhood in order to maximize social, emotional, cognitive, and conscience facilitating experiences for each developmental stage of the child. Learning pro-social skills—how to get along with others, how to have empathy for those in distress, how to manage one’s own distress, how to take turns, how to live in community with others, how to share and show compassion—are all critical experiences that shape a child’s neurobiological development.

So what happens when children miss critical, sensory-rich, pro-socializing experiences? What often occurs when children have chronic and/or prolonged exposure to traumatic distress, multiple disruptions in attachment, neglect, interpersonal violence, institutional care, or maltreatment? Simply put, we see increased anti-social behaviors. It is imperative for both parents and professionals to clearly understand that children exhibiting anti-social behaviors like hitting, lying, stealing, hurting animals, manipulating, and defiance are giving a window into their early life experiences—experiences which would probably overwhelm you with terror and pain if you actually had to feel what the child felt during their suffering.

It is imperative for both parents and professionals to clearly understand that children exhibiting anti-social behaviors like hitting, lying, stealing, hurting animals, manipulating, and defiance are giving a window into their early life experiences—experiences which would probably overwhelm you with terror and pain if you actually had to feel what the child felt during their suffering.

If left unresolved, complex childhood trauma and developmental trauma will often work their way into the next generation. We know that 75 percent of perpetrators of child sexual abuse report to have themselves been sexually abused as children. (van der Kolk, 2005) Data tells us that most interpersonal trauma on children is perpetrated by adult victims of childhood trauma and neglect. (van der Kolk, 2005)

Experience Is the Architect of the Brain

Anti-social behaviors occur when children have been deprived of thousands upon thousands of sensory-rich, pro-socializing experiences that they would have received through primary parent/ child attachment experiences. The young child’s brain is experience dependent. The actual wiring of the brain’s circuitry is occurring through these numerous sensory-rich experiences with the primary attachment figure. The human brain is both malleable and mutable, such that its structural organization reflects the history of the organism. (Luu and Tucker, 1996) In essence, experience is the architect of the brain. This is true whether or not those early life experiences happen to be positive, responsive, and nurturing or negative, violent, and traumatic.

The young child’s brain is experience dependent. The actual wiring of the brain’s circuitry is occurring through these numerous sensory-rich experiences with the primary attachment figure. The human brain is both malleable and mutable, such that its structural organization reflects the history of the organism. (Luu and Tucker, 1996) In essence, experience is the architect of the brain. This is true whether or not those early life experiences happen to be positive, responsive, and nurturing or negative, violent, and traumatic.

For young children exposed to chronic states of distress in which their most basic needs for safety, attachment, and nurturance are not met, the result can be catastrophic for the developing self. These children may have both social-emotional skill deficits as well as neurobiological effects that have shaped the young brain to be trauma-reactive. Unmanageable distress for the infant and young child exposes their neurobiological system to increased levels of cortisol and adrenaline, which subsequently exposes their sensory system to being easily triggered into a dysregulated state. As a result, a simple directive or demand (“It’s time to do homework!”) can easily overwhelm a trauma-reactive child who has minimal ability to regulate her neurobiological states once triggered.

As a result, a simple directive or demand (“It’s time to do homework!”) can easily overwhelm a trauma-reactive child who has minimal ability to regulate her neurobiological states once triggered.

Anti-Social Behaviors as Survival Strategy

It is against this backdrop that we can more insightfully understand our children’s complex behaviors related to their history of deprivation, trauma, pain, and suffering. Lying, stealing, hoarding food, lack of empathy, and aggression are common behaviors for children who have experienced trauma. Traditional parenting interventions and techniques seek to change children’s behavior through principals of loss/punishment. For non-traumatized children, using punishment and emotional distance (such as time-outs or grounding in their room) to change a child’s behavior is effective. It is primarily effective because the child is attached to the parent and the parent is using years of attachment history to motivate the child to change.

For children with early chronic neglect and trauma, these traditional ideas of loss/punishment and emotional distance will be ineffective. The child has missed critical developmental milestones that would have given him the social, emotional, and cognitive competencies to learn from consequences, punishments, or emotional distance. Trust and truth-telling are the foundation of loving familial relationships. For children with no experience of permanence, safety, and nurturance, anti-social behaviors such as lying or manipulating were often necessary and effective survival strategies.

The child has missed critical developmental milestones that would have given him the social, emotional, and cognitive competencies to learn from consequences, punishments, or emotional distance. Trust and truth-telling are the foundation of loving familial relationships. For children with no experience of permanence, safety, and nurturance, anti-social behaviors such as lying or manipulating were often necessary and effective survival strategies.

In addition, a child that is not securely attached to his primary caregiver will not be motivated to please his parent. In fact, the child could be motivated to frustrate or provoke their parent. Hitting, lying, stealing, and manipulating are quite common when children are defending themselves against attaching. These behaviors should be understood as a defensive strategy, a learned way of coping with terror and fright. For these children, attaching means flooding their sensory system with triggering sensations that feel overwhelming, disorganizing, or terrifying. It is important to note that children do not have insight into these triggers and dynamics; they are using defensive strategies to avoid more pain and distress.

It is important to note that children do not have insight into these triggers and dynamics; they are using defensive strategies to avoid more pain and distress.

Leading the Dance

What the child needs most in order to heal—a deep, meaningful, sustained primary attachment relationship—is the thing she fears the most. The inherent challenge for the parent who is parenting the child of loss, trauma, and multiple placements is that their traditional view of parenting (which is primarily based on the way they were parented themselves in combination with what is considered to be culturally acceptable) will be highly ineffective.

We are all social-emotional beings and we are deeply affected by the emotions of those around us. Most parents quickly feel exhausted, overwhelmed, or triggered by their child’s distressed states and maladaptive behaviors. Emotions are contagious. A child’s angry or hurtful behavior is often mirrored by a distressed parent. But the expression of parental frustration and anger in response to the child’s misbehavior has the effect of reinforcing the misbehavior. For the parent to begin to establish a meaningful, sustained primary attachment relationship with a trauma-reactive child, a new template must be formed. The parent must learn to lead a dance with the child that creates the primary parent/child attachment relationship, from which the child’s pro-social development can be nurtured.

For the parent to begin to establish a meaningful, sustained primary attachment relationship with a trauma-reactive child, a new template must be formed. The parent must learn to lead a dance with the child that creates the primary parent/child attachment relationship, from which the child’s pro-social development can be nurtured.

As the leader of the dance, the parent must be able to set the affective tone in which a trusted, committed, permanent relationship can be established, and eventually, over time, create the context in which healing can occur. The most critical component of this intimate dance between parent and child is the emotional tone and intelligence of the parent. It is the emotion of the parent that the child is experiencing through their senses (facial cues, body posture, tone of voice, etc.).

Parents with increased emotional intelligence are not just emotionally reacting to external stressors, but rather are able to model healthy ways of managing their own internal distress. For example a parent might say, “Mom is frustrated right now, I’m going to take a few minutes to calm down before we talk about how we’re going to solve this problem.” The parent takes a walk, calls a friend, rides a bike, plays basketball, reads, journals, or asks “Can anyone tell Mom a funny joke right now? I really need a good laugh.” Here the parent is both leading the emotional dance and modeling healthy emotional coping strategies. This is effective because the primary way children learn is through imitation.

For example a parent might say, “Mom is frustrated right now, I’m going to take a few minutes to calm down before we talk about how we’re going to solve this problem.” The parent takes a walk, calls a friend, rides a bike, plays basketball, reads, journals, or asks “Can anyone tell Mom a funny joke right now? I really need a good laugh.” Here the parent is both leading the emotional dance and modeling healthy emotional coping strategies. This is effective because the primary way children learn is through imitation.

As the leader of the dance, the trauma-informed parent allows for missteps by the child who has never successfully danced in any “permanent” way. A child who has had too many changes of partners is a child who will have developed many defensive strategies to avoid further psychic pain and trauma. Lying and manipulating behaviors help protect the child from becoming attached (remember their attachment experiences brought suffering, terror, fear, and loss). These children often prefer the dance of isolation to the continued suffering that occurs with the repeated rejection and loss of not having their primary attachment needs met.

A parent who is being nurturing and comforting might be met with anger and hostility from their child: “Get away from me! Leave me alone!” These missteps allow the parent to give voice to their child’s distress, acknowledging how painful, scary, and overwhelming learning the dance of attachment can be: “I know this is hard and that getting close is scary. I want you to know that I’m here for you.” Giving yourself and your child permission to make mistakes while you are learning these complex dance steps is critical. Practice levity, forgiveness, and really good self care!

Knowing Yourself

Since most parents have never experienced this amount of core trauma themselves, as they begin to intimately engage with their trauma-reactive child, the experience often feels overwhelmingly painful or distressing for the parent. This pain, though, can create a critical opportunity for parents to explore their own parenting history and style as they are now in the heat of the parent/child attachment dance. Personal intelligence and insight into one’s own mind, motivations, beliefs, and triggers are critical components to being able to lead the dance of attachment. As parents, many of our most impactful childhood experiences are encoded in implicit memory and are outside of conscious awareness. (To further explore one’s own parenting style and history, check out Parenting From the Inside Out by Dan Siegel and Mary Hartzell and Wounded Children, Healing Homes by Jayne Schooler, Betsy Keefer Smalley, and Timothy J. Callahan.)

Personal intelligence and insight into one’s own mind, motivations, beliefs, and triggers are critical components to being able to lead the dance of attachment. As parents, many of our most impactful childhood experiences are encoded in implicit memory and are outside of conscious awareness. (To further explore one’s own parenting style and history, check out Parenting From the Inside Out by Dan Siegel and Mary Hartzell and Wounded Children, Healing Homes by Jayne Schooler, Betsy Keefer Smalley, and Timothy J. Callahan.)

Teaching Pro-Social Behaviors

For the child with increased anti-social or maladaptive behaviors due to complex trauma, parents must make a paradigm shift away from traditional or punitive parenting strategies toward a style that uses attachment-facilitating interventions based on principals of addition and developmental need.

Developmentally, children must first have basic trust that their primary need for attachment, stability, safety, and nurturance will be met. To establish this basic trust, parents must use parenting interventions designed to add the pro-socializing, sensory-rich experiences the child needs. Through these experiences, children can learn social and emotional interpersonal skills that other children likely learned at much earlier ages. These interventions need to be both reactive (what the parent needs to do in response to the current behavior/situation) and pro-active (what the parent can practice with the child every day to add the pro-socializing experiences the child needs to learn self-regulation, impulse control, empathy, problem-solving skills, emotion recognition, regulation, and management).

To establish this basic trust, parents must use parenting interventions designed to add the pro-socializing, sensory-rich experiences the child needs. Through these experiences, children can learn social and emotional interpersonal skills that other children likely learned at much earlier ages. These interventions need to be both reactive (what the parent needs to do in response to the current behavior/situation) and pro-active (what the parent can practice with the child every day to add the pro-socializing experiences the child needs to learn self-regulation, impulse control, empathy, problem-solving skills, emotion recognition, regulation, and management).

For example, if my seven-year-old son consistently hits his younger sister when she takes his toy, how can I help him manage his aggressive impulses? First, I remove my child from the stimulating situation into a safe, non-stimulating environment and help him calm down. I have empathy for his distress and say, “It’s hard when someone takes your toy. ” Once he’s calm, I ask “Are you ready to solve the problem with your sister? Do you need mom’s help to solve the problem?”

” Once he’s calm, I ask “Are you ready to solve the problem with your sister? Do you need mom’s help to solve the problem?”

Children who do not regulate well and have missed critical developmental milestones will need the parents’ executive functioning to help them think through the social-emotional problems that occur in their daily interactions. If my son has missed thousands upon thousands of sensory-rich, pro-socializing experiences, of course he will hit his little sister when she takes his toy.

Next, I need to help him practice sharing, taking turns, and learning what to do when someone takes something from you so that the lived experience of sharing and problem solving is integrated into his neurobiological system. All children need to be able to first regulate their emotions before they can access their thinking and decision-making skills.

Since I know my son consistently struggles with being angry and impulsive, my pro-active strategy includes providing him with the sensory rich social-emotional experiences he needs to learn these critical relational and problem-solving skills. First I have to remember that he is not the problem! His aggressive, reactive, and impulsive behavior is the problem.

First I have to remember that he is not the problem! His aggressive, reactive, and impulsive behavior is the problem.

Traumatic memories are encoded and stored within the limbic structures of his brain. These same regions must be activated to create emotional arousal based on pleasure, excitement, and mutually enjoyable social interaction. I let him know that every day we’re going to have fun practicing what to do when someone takes your toy or makes you mad. The daily role play should begin with playful engagement—just me and my child playing with toys on the floor. Then I tell him to take my toy without asking. My responses vary from crying, to getting mad, to running away, to asking him to give it back.

Here I simply want him to experience the range of choices and options that I have in deciding how to respond. I remain mindful that because he is trauma-reactive, he is not thinking through his choices; he’s simply reacting in a state of distress. Next we practice Mom taking the toy from him, letting him know that the ultimate goal is for him to be able to put words to his feelings and tell me to please give back the toy. This targeted behavioral training is effective in improving social and emotional problem solving and conflict management over time. The practice is fun and experiential, and we take turns playing various roles. This allows the child’s sensory system to experience the pro-socializing behaviors that were missed at earlier stages and that are necessary to activate and change the limbic structures of his brain.

This targeted behavioral training is effective in improving social and emotional problem solving and conflict management over time. The practice is fun and experiential, and we take turns playing various roles. This allows the child’s sensory system to experience the pro-socializing behaviors that were missed at earlier stages and that are necessary to activate and change the limbic structures of his brain.

Using principals of addition and attachment-facilitating interventions will give my child the pro-socializing experiences he needs to heal, thrive, and become a productive member of society.

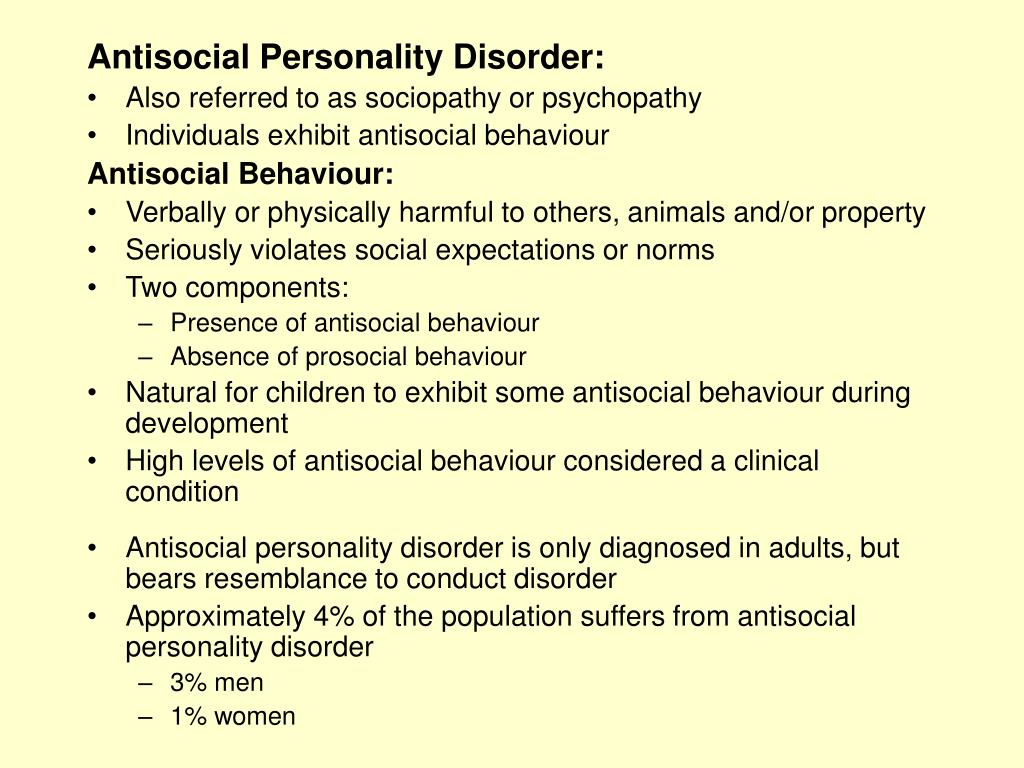

Antisocial Behavior: In Children

It’s normal for children to exhibit positive and negative social behaviors as they age and develop. Some kids lie, some rebel, some withdraw. Think the smart but introverted track star or the popular but rebellious class president.

But some children exhibit high levels of antisocial behaviors. They are hostile and disobedient. They may steal and destroy property. They might be verbally and physically abusive.

They might be verbally and physically abusive.

This type of conduct often means your child is showing signs of antisocial behavior. Antisocial behavior is manageable, but can lead to more severe problems in adulthood if left untreated. If you’re worried that your child has antisocial tendencies, read on to learn more.

Antisocial behavior is characterized by:

- aggression

- hostility toward authority

- deceitfulness

- defiance

These conduct problems usually show up in early childhood and during adolescence, and are more prevalent in young boys.

There is no current data that reveals the number of children who are antisocial, but previous research places the number between 4 and 6 million, and growing.

Risk factors for antisocial behavior include:

- school and neighborhood environment

- genetics and family history

- poor and negative parenting practices

- violent, unstable, or tumultuous home life

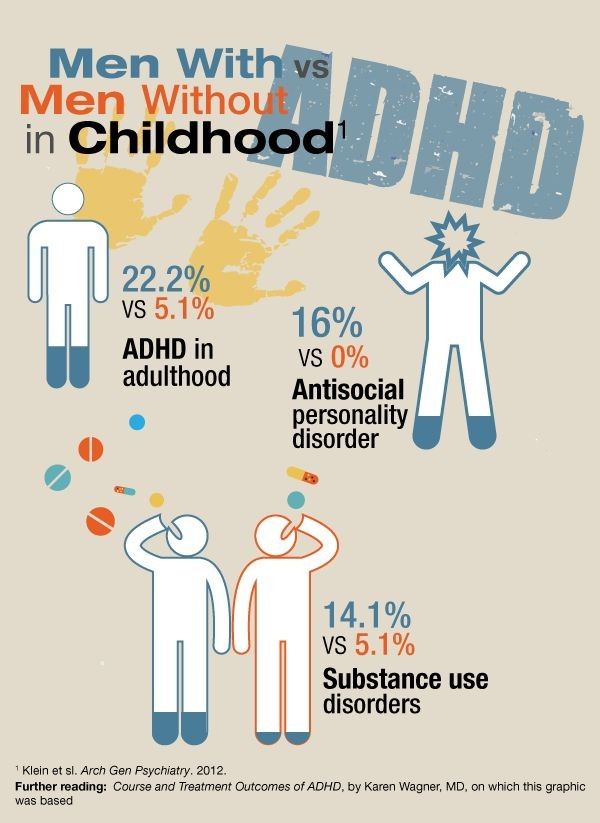

Hyperactivity and neurological problems can also cause antisocial behavior. Youth with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have been found to be at a higher risk of developing antisocial behavior.

Youth with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have been found to be at a higher risk of developing antisocial behavior.

Antisocial behavior can occasionally be identified in kids as young as 3 or 4 years old, and can lead to something more severe if not treated before age 9, or third grade.

The symptoms your child might exhibit include:

- abusive and harmful to animals and people

- lying and stealing

- rebellion and violating rules

- vandalism and other property destruction

- chronic delinquency

Research shows that childhood antisocial behavior is associated with a higher rate of alcohol and drug abuse in adolescence. This is because of shared genetic and environmental influences.

Severe forms of antisocial behavior can lead to conduct disorder, or an oppositional defiant disorder diagnosis. Antisocial children may also drop out of school and have trouble maintaining a job and healthy relationships.

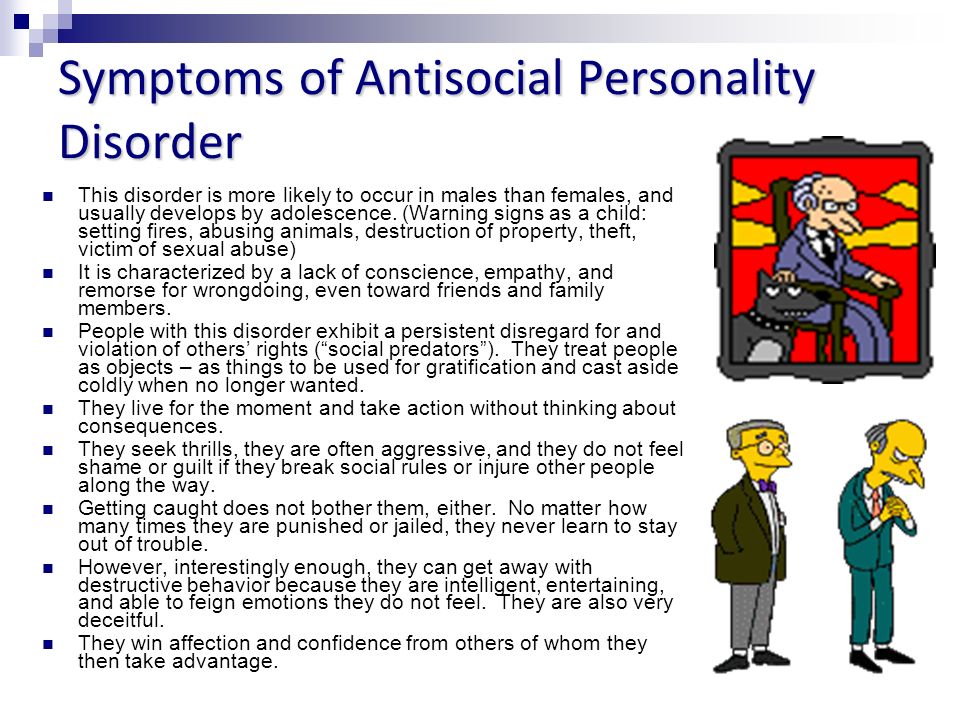

The behavior could also lead to antisocial personality disorder in adulthood. Adults living with antisocial personality disorder often display antisocial behavior and other conduct disorder symptoms before age 15.

Adults living with antisocial personality disorder often display antisocial behavior and other conduct disorder symptoms before age 15.

Some signs of antisocial personality disorder include:

- lack of conscience and empathy

- disregard and abuse of authority and people’s rights

- aggression and violent tendencies

- arrogance

- using charm to manipulate

- lack of remorse

Early intervention is key to preventing antisocial behavior. The Center for Effective Collaboration and Practice suggests that schools develop and implement three different prevention strategies.

1. Primary prevention

This would include engaging students in school-wide activities that could deter antisocial behavior, such as:

- teaching conflict resolution

- anger management skills

- emotional literacy

2. Secondary prevention

This targets students who are at risk for developing antisocial tendencies and engaging them in individualized activities, including:

- specialized tutoring

- small group social skills lessons

- counseling

- mentoring

3.

Tertiary prevention (treatment)

Tertiary prevention (treatment)The third step is continuing intensive counseling. This treats antisocial students and students with chronic patterns of delinquency and aggression. The center suggests that families, counselors, teachers, and others coordinate efforts to treat children with antisocial behavior.

Other ways to treat antisocial behavior include:

- problem solving skills training

- cognitive behavioral therapy

- behavioral family intervention

- family therapy and adolescent therapy

Parents can also undergo parent management training to address any negative parenting issues that may contribute to the child’s antisocial behaviors.

Research has found that warmth and affection, reasonable discipline, and an authoritative parenting style have positive outcomes for children. This can help them create positive relationships and improve school performance.

It is normal for children and teenagers to exhibit some antisocial tendencies, like being withdrawn or mildly rebellious. But for some kids, those tendencies can signal something more alarming.

But for some kids, those tendencies can signal something more alarming.

Speak with your child if you’re worried about their behavior so you can have a better sense of what’s happening from their perspective. Make sure to also speak with a doctor so you can come up with an effective plan to treat your child’s antisocial behavior.

It’s important you address conduct problems as early in childhood as possible to prevent a more severe diagnosis in the future.

Share on Pinterest

Antisocial behavior: how to react to parents

A difficult age is difficult not only for the parents of a teenager, but also, first of all, for himself. Rapid growth, hormonal surges and mood swings create a big burden on the child. What do parents need to know about undesirable and sometimes dangerous behavior of a teenager? Is it possible to avoid extreme manifestations of antisocial behavior?

Adolescence now begins earlier both physiologically and psychologically. Parents often notice adolescent manifestations already at 9-11 year old children.

Parents often notice adolescent manifestations already at 9-11 year old children.

Rebellion of the body

In adolescence, a lot of processes go on at the same time at different levels - physiological, psychological and social. From the point of view of physiology, a person becomes an adult sexually mature biological organism, the body is changing rapidly, and the sensations are not always comfortable. At this time, well-being often worsens, immunity decreases, hormonal status jumps, and the load on internal organs increases. In adolescents, chronic severe illnesses become aggravated or begin. At this time, a person is more vulnerable.

There is also neurophysiology - a teenager is undergoing a serious restructuring of the brain, rejecting extra connections that were not involved before that time, and activating new connections.

"Disassembled" brain

The brain changes as quickly as the body, and temporarily "loses" some functions. In the frontal region, as well as in other areas responsible for self-control and the choice of a behavior strategy, a lot of random neural connections are formed that can be destroyed instantly. The information that was imprinted in memory with the help of these connections is lost. A teenager seems to be balancing on the verge between childhood and adulthood.

The information that was imprinted in memory with the help of these connections is lost. A teenager seems to be balancing on the verge between childhood and adulthood.

Even in the simplest, everyday situations, he may feel confused and behave inappropriately, because the old patterns of behavior have already been rejected, and new ones have not yet formed. In a sense, we can say that during adolescence there are periods when the brain is in a "disassembled" state - it has been taken apart and has not yet been reassembled in a new way.

At this time, the child may experience difficulties with criticality, with assessing the consequences of his actions, with forecasting. The most complex and late maturing brain structures, which are responsible for goal setting and forecasting, turn out to be vulnerable and do not work very well in a state of restructuring.

Mastering social connections

Socially, a teenager turns his back on the microcosm of his family and faces the big world, society. The main events in his life begin to take place among peers. What he is mainly interested in is relationships among friends, who is friends with whom, who likes who, who does not like who, who framed or helped out whom.

The main events in his life begin to take place among peers. What he is mainly interested in is relationships among friends, who is friends with whom, who likes who, who does not like who, who framed or helped out whom.

The task of age is the development of complex social ties, familiarity in practice with such phenomena as group hierarchy, group pressure, place in a group.

This is a very complex world, and it's good if you manage to master it. Some parents are very happy if their child, instead of hanging out with peers, sits and reads smart books. And psychologists in this case, on the contrary, express concern, because this may indicate problems with socialization. So it's normal if at this age a child is more interested in feelings and relationships than schoolwork.

Complex reactions

Adolescents' behavior is often unpredictable. In one day or even an hour, they can show completely opposite reactions:

- purposefulness and perseverance combined with impulsiveness;

- irrepressible thirst for activity can be replaced by apathy;

- increased self-confidence, categorical judgments alternate with vulnerability and self-doubt;

- swagger in behavior is sometimes combined with shyness;

- romantic moods often border on cynicism, prudence;

- tenderness, affection does not exclude cruelty;

- the need for communication struggles with the desire to be alone.

Risk factors

At a transitional age, a teenager begins to explore the space around him and does not always have the opportunity for constructive activities that would reveal the strength of his "I". He is going through a period of searching for forms of manifestation of his strength and energy, combined with a decrease in intellectual activity, his state of "readiness for a feat" can lead to deviant manifestations. Even under favorable conditions and in the normal version of development, adolescence carries an asocial charge.

There are many reasons for the emergence of antisocial behavior - these are upbringing, heredity, training, environment. But there are a number of main factors that influence the emergence and development of asocial forms of behavior in adolescence.

Biological - manifests itself in the form of physical features, for example, external unattractiveness, various defects, hearing, speech.

Psychological - manifests itself in neuropsychiatric abnormalities, and also depends on the temperament and the state of the individual: this is increased suggestibility, and psychopathy, and increased excitability of the nervous system.

Social - expressed in the adolescent's relationship with society (how he communicates with family and friends).

What can provoke antisocial behavior?

- Experience of resentment, loneliness, own uselessness, alienation and misunderstanding.

- Actual or imaginary loss of parental love, unrequited love, jealousy.

- Experiences associated with a difficult situation in the family, with the death, divorce or departure of parents from the family.

- Feelings of guilt, shame, offended pride, self-accusation (including those associated with domestic violence: often a teenager feels guilty about what is happening and is afraid to talk about it).

- Fear of shame, ridicule or humiliation.

- Fear of punishment (for example, due to early pregnancy, serious misconduct), fear of the consequences of failure in some activity (for example, failure in exams).

- Love failures, difficulties in sexual relations, pregnancy.

- Feelings of revenge, anger, protest, threat or extortion.

- Desire to attract attention to oneself, arouse sympathy, avoid unpleasant consequences, get away from a difficult situation, influence another person.

- Sympathy or imitation of comrades, idols, heroes of books or films, following "fashion".

- Unfulfilled needs for self-affirmation, for belonging to a significant group.

Forms of antisocial behavior

Deviant behavior is associated with a violation of age-appropriate social norms and established rules of behavior in the family and school.

Most often it manifests itself in the form of aggression, unwillingness to learn, demonstrating one's negativity to one's inner circle. Such behavior may be accompanied by leaving home, vagrancy, and even an attempt to settle scores with life. Alcohol, drugs, and delinquency appear in the life of a teenager.

Addictive behavior is characterized by an escape from existing problems, leaving "into your own world". This may be accompanied by a flight into the body (eating disorders), a flight into work (workaholism), a flight into fantasy (computer games), a flight into religious sects, or into sex.

This may be accompanied by a flight into the body (eating disorders), a flight into work (workaholism), a flight into fantasy (computer games), a flight into religious sects, or into sex.

Despite the fact that there are many factors and causes of antisocial behavior, it is quite possible to avoid it. The earlier parents begin to prevent the manifestation of asocial forms of behavior in children, the greater the chance that the child will enter adulthood, bypassing this state.

You need to pay attention if the child:

- is rude, insolent, goes home without informing them;

- lies;

- needs money;

- becomes addicted to alcohol;

- stops communicating with parents and does not respond to demands and requests;

- cannot cope with the school curriculum due to absenteeism, homework not done.

What to do?

Prevention of deviant behavior is, first of all, trust in the family and close communication with the child. It is family conflicts that often lead to irreparable consequences. It is necessary to start prevention from an early age, from childhood to explain to the child what is good and what is bad, that problems can and should be solved, and not run away from them.

It is family conflicts that often lead to irreparable consequences. It is necessary to start prevention from an early age, from childhood to explain to the child what is good and what is bad, that problems can and should be solved, and not run away from them.

The child first of all seeks understanding and support from his parents; In order for parents to give him this support, there must be trust in the relationship. This means that he does not have the feeling that his parents are interfering in his affairs, he lets them into his life voluntarily. You need to believe in a child - this is the main thing. It is of great importance for a difficult teenager to experience happiness, the joy of success. This is the greatest incentive for self-improvement.

What practical steps can be taken to avoid antisocial behavior? What can parents do during this difficult period?

- To inform the child and increase his psychological literacy about those intrapersonal problems that he encountered.

Scientific data, the experience of other people can help here. To teach a child to cope with life's difficulties, with personal experiences and stressful situations and help him build the right life priorities.

Scientific data, the experience of other people can help here. To teach a child to cope with life's difficulties, with personal experiences and stressful situations and help him build the right life priorities. - Listen and hear the child, tell him that you went through the same problems as him. This will not only develop trust, but will also defuse the situation well (using the “metaphor parenting” technique. The easiest and most effective way to find a common language with a teenager is to communicate with him in the language of metaphors).

- Recognize and respect each child's personality, promote the free development and improvement of his spiritual world. It is extremely important that the child never feel lonely, he must have confidence in himself and his loved ones.

- Help the child find the kind of activity where he can realize himself and be successful. Engage the child in various sections, send the child to sports or a creative group. It is necessary to direct his interests and energy in a positive direction.

- Do not abuse punishments and prohibitions. Use constructive and appropriate incentives and punishments. Talk and explain with the child, but do not set conditions, do not demand ideal behavior.

- To develop the cognitive interest of the child. Involve children in different activities.

- Find the strengths and qualities of a teenager and use and develop them correctly. Notice even minor changes in behavior, since antisocial behavior appears episodically at first. Comprehensively introduce changes in the daily routine, in society and leisure of a teenager.

If you cannot find a common language with a difficult child on your own, you can turn to the help of a psychologist. Professional counseling will help the child and parents resolve intra-family conflicts.

Useful Resources

All-Russian Children's Helpline: 8-800-2000-122

Psychological counseling, emergency and crisis psychological assistance for children in difficult life situations, adolescents and their parents (free of charge, around the clock).

Hotline "A child in danger" of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation: 8-800-200-19-10. Children, their parents, as well as all caring citizens who have information about a crime committed or being prepared against a minor or underage child, can call the free, round-the-clock phone number.

Foundation for the support of children in difficult life situations.

Information portal about all kinds of addictions related to computer and mobile devices.

Help line "Children ONLINE".

Specialized pages of the website of the Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution "Center for the Protection of the Rights and Interests of Children": "Childhood Support", "Your Right", "Information Security", "Value of Life".

Sources:

Memo “Parents on the Psychological Security of Children and Adolescents” by the Federal State Budgetary Institution “Center for the Protection of Rights and Interests of Children”

Portal “Orthodoxy and Mir”

FBUZ “Center for Hygienic Education” Rospotrebnadzor

“To make our children happy. Adolescents” (CLEVER, PSYCHOLOGIES. 2014)

Adolescents” (CLEVER, PSYCHOLOGIES. 2014)

Adolescent antisocial behavior: how to respond?

home

Parents

How to raise a child?

Antisocial behavior of a teenager: how to respond?

- Tags:

- Expert advice

- age features

- child safety

- antisocial behavior

- teens

Adolescence is full of surprises and surprises. This is due to a mismatch of desires and opportunities: the child already wants to be an adult, but does not yet have the resource for this. It often happens that calm children suddenly begin to commit antisocial acts. What pushes teenagers to such behavior and how should parents react to it?

In psychology, behavior in which generally accepted norms are ignored or violated, and harms the adolescent himself, society, and property, is called antisocial. Or deviant. What is considered deviant behavior?

1. Risky behavior

It can be caused by a desire to stand out, intra-family conflicts, personal and age characteristics, as well as the inefficiency of the leisure system. Risky behavior includes:

Risky behavior includes:

- Roofing - moving along the high points of buildings

- Stalking - exploration of abandoned or unfinished buildings

- Dangerous selfie - a photo taken at the risk of life, for example, on the edge of a roof or with a firearm in hand

- Digging - research of underground utilities

- Hooking - passage on the roof of a train or between cars

2. Aggressive behavior

It should be noted that increased aggressiveness is typical of childhood and adolescence. Most often it is formed in children who have difficulties of a personal and social nature. Often the aggressors were once victims, but now they repeat the actions of their offenders - a vicious circle is obtained. What is considered aggressive behavior?

- Fighting, hitting, spanking

- Taunts

- Violent practical jokes

- Collective disregard

- Spreading rumors

- Threats

3. Dependent behavior

Dependent behavior

There are a huge number of addictions, and they are all divided into chemical (alcohol, nicotine, drugs) and process (Internet addiction, food addiction, gambling addiction).

Formation of addiction is a process influenced by many factors:

- family situation

- low self-esteem

- low motivation for learning

- bad relationships with peers

4. Suicidal behavior

This is one of the manifestations of antisocial behavior that causes the greatest concern in the modern world. According to the World Psychiatric Association, the most vulnerable group is adolescents and young people from 15 to 19years. The cause of self-harm and suicidal behavior can be:

- any difficult situation for teenagers,

- unhappy love,

- quarrel with a significant peer or adult,

- a case of suicide in the environment (even if it was the lead singer of a favorite group),

- academic failure,

- conflicts within the family;

- bullying at school

5. Delinquent behavior

Delinquent behavior

Delinquent behavior is a mixture of everything listed above with a direct violation of the law (we are not talking about criminal liability). What is delinquent behavior?

- Theft, theft

- Fraud

- Extortion

- Vandalism, damage to property

- Arson

- Fighting

- Hooliganism

- Bulling

- Cruelty to animals

All this is a teenager's cry for help. Deviant behavior is always a sign that a teenager cannot cope on his own with what is happening inside him.

Factors that influence the formation of antisocial behavior do not change depending on the type of deviation:

- the need for communication (and for adolescence, intimate-personal communication with peers is the leading activity)

- personal characteristics, for example, inadequately low self-esteem or pathological risk appetite,

Unsatisfied need for attention and acceptance.

But first of all, of course, this is family trouble, and not necessarily in the form in which we are accustomed to imagine it. For a teenager, a negative assessment of the parents or their misunderstanding of his interests is enough.

The family situation always has a very strong influence on the formation of deviant behavior. The main risk factor here is permissiveness or, conversely, too strict restrictions on the child within the family, inconsistency in parental requirements, and domestic violence (including emotional violence). The parent is the main adult in the life of the child, the authority that gives direction for development.

If a parent sees that something is happening to the child, that he/she has gotten "out of hand", got into "bad company" and started to commit antisocial acts, one should not hesitate. It is necessary to seek help from a psychologist whose specialty is working with adolescents. We must be prepared for the fact that the work, most likely, will be carried out comprehensively - both with the child and with the family, because the behavior of a teenager is an illustration of the problems of his family. The antisocial behavior of a child does not mean at all that he grows up in a bad family, that parents do not properly fulfill their parental responsibilities, but it is an indicator that something needs to be changed.

The antisocial behavior of a child does not mean at all that he grows up in a bad family, that parents do not properly fulfill their parental responsibilities, but it is an indicator that something needs to be changed.

Read also

Teen parties: features and dangers

Happy child: deviant behavior

How to react?

How should a parent react if their child does something that deviates from the norm? First of all, refuse to assess the child. You can evaluate his actions, his words, but not his personality. He is your child, he remains good, despite the act that he committed. And with this act he asks for help.

The first parental impulse is usually in the spirit of “Punish! Ban!”, but this is not quite the right position. Of course, it is possible to punish and prohibit, but this will only aggravate the already suffering child-parent relationship. Punishment in adolescence is not the best strategy, because it causes even more protest and rejection in a teenager. This is the age when problems can only be solved through constructive dialogue.

This is the age when problems can only be solved through constructive dialogue.

A ban on antisocial activities is unlikely to bear fruit. Firstly, the teenager had already guessed that it was impossible to do this, but he did it anyway, and secondly, the peculiarity of deviant behavior is the change of one of its types to another. For example, a teenager was a hooker, his parents forbade him, he obeyed and started drinking. Parents found out, forbade him, and instead of drinking alcohol, he began to fight with his peers. And so on. This chain can continue indefinitely until the main problem, the very reason why the teenager behaves this way, is eliminated. Therefore, bans will not solve the problem.

Antisocial behavior in adolescence is not uncommon, but not the norm either. Of course, age characteristics leave their mark on the behavior of teenagers, and in many respects they influence the formation of deviant behavior, but, despite this, such a problem must be urgently addressed together with a qualified specialist.