What is the main cause of stillbirth

Stillbirth - Causes - NHS

A large proportion of stillbirths happen in otherwise healthy babies, and the reason often can't be explained. But there are some causes we do know about.

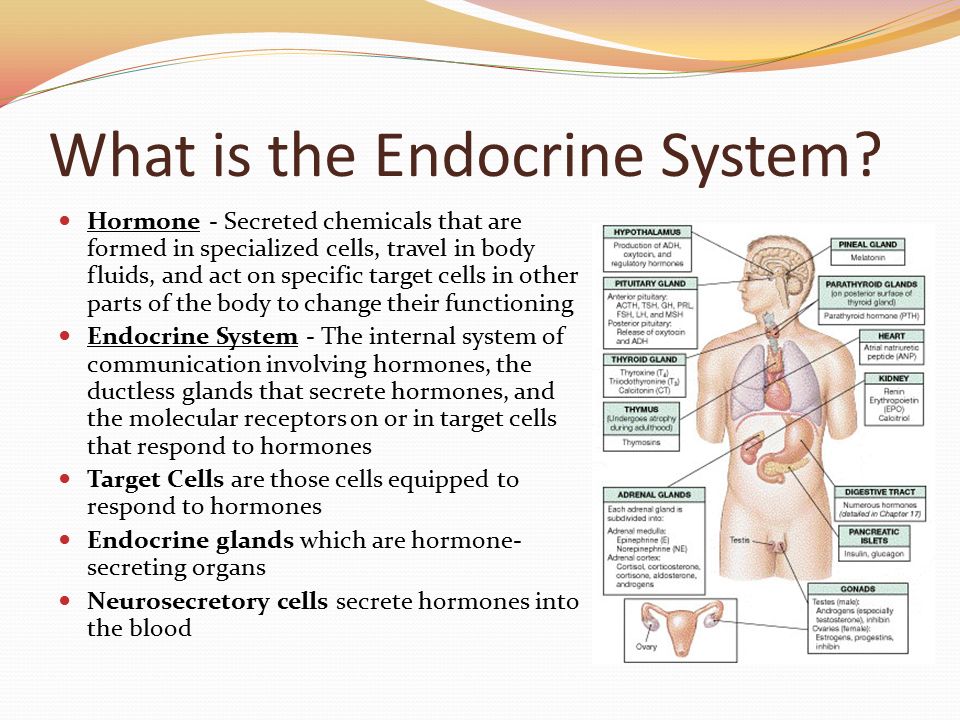

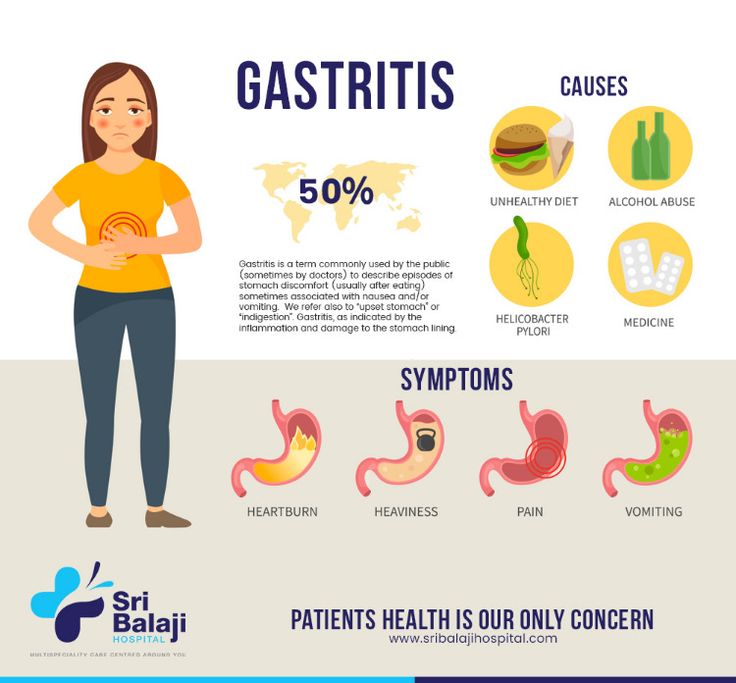

Complications with the placenta

Many stillbirths are linked to complications with the placenta. The placenta is the organ that links the baby's blood supply to the mother's and nourishes the baby in the womb.

If there have been problems with the placenta, stillborn babies are usually born perfectly formed, although often small.

With more research, it's hoped that placental causes may be better understood, leading to improved detection and better care for these babies.

Other causes of stillbirth

Other conditions that can cause or may be associated with stillbirth include:

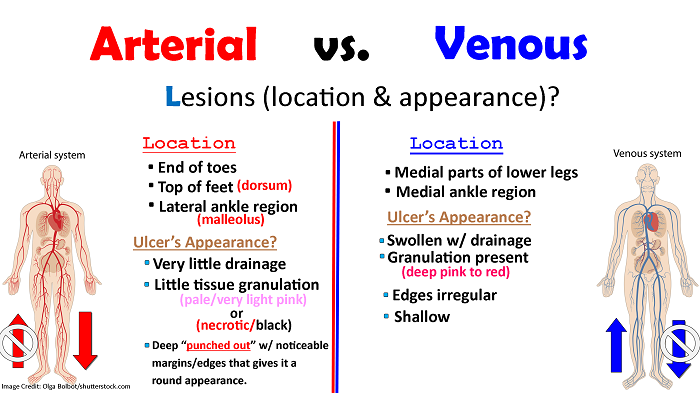

- bleeding (haemorrhage) before or during labour

- placental abruption – where the placenta separates from the womb before the baby is born (there may be bleeding or abdominal pain)

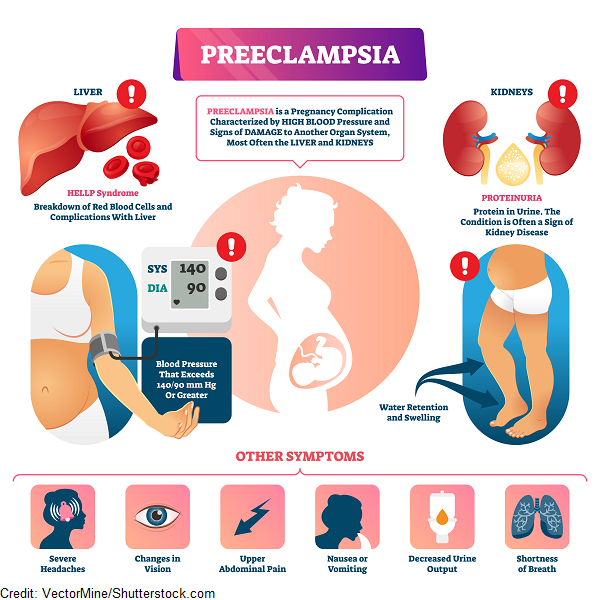

- pre-eclampsia – a condition that causes high blood pressure in the mother

- a problem with the umbilical cord, which attaches the placenta to the baby's tummy button – the cord can slip down through the entrance of the womb before the baby is born (cord prolapse) or can be wrapped around the baby and become knotted

- intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) or obstetric cholestasis – a liver disorder associated with severe itching during pregnancy

- a genetic physical defect in the baby

- pre-existing diabetes

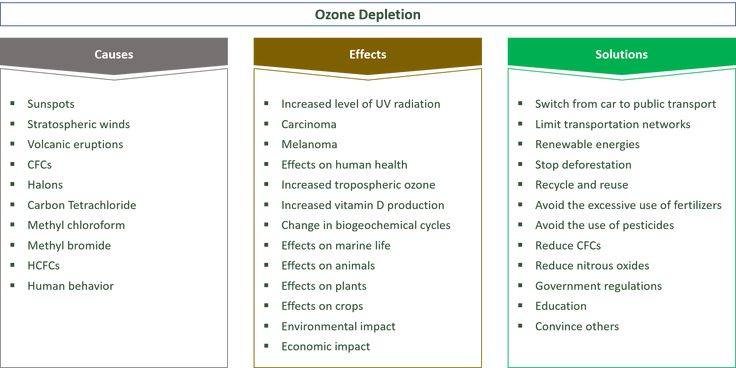

- an infection in the mother that also affects the baby

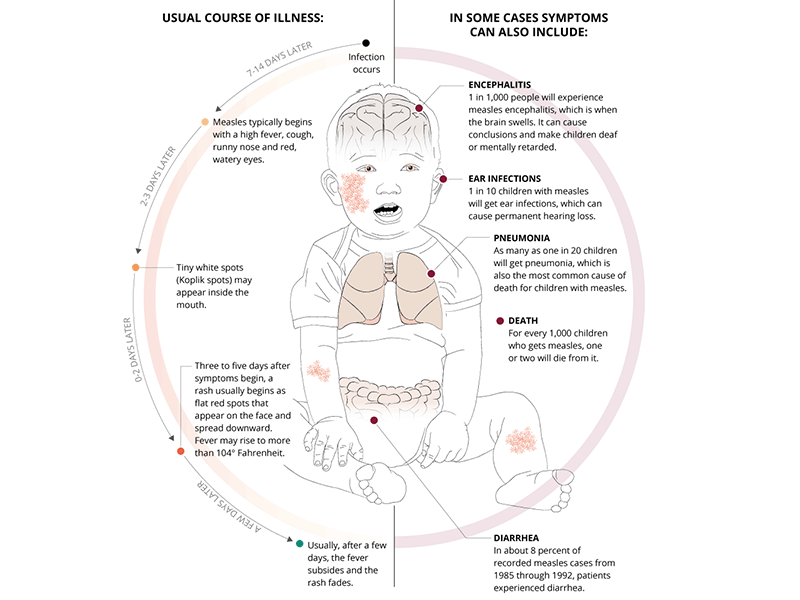

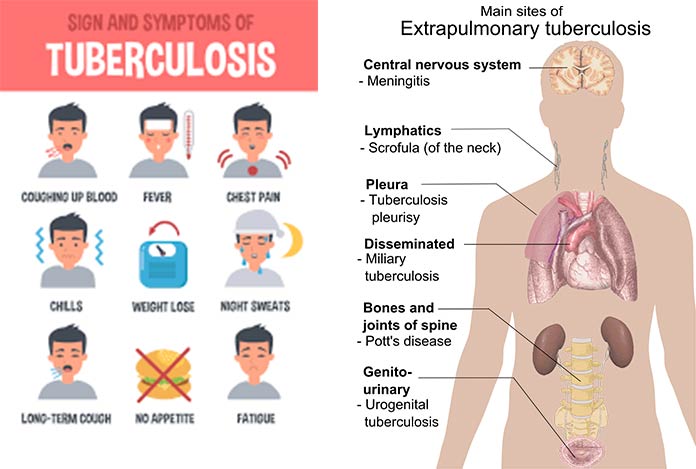

Infections

Usually this will be a bacterial infection that travels from the vagina into the womb (uterus). These bacteria include group B streptococcus, E. coli, klebsiella, enterococcus, Haemophilus influenza, chlamydia, and mycoplasma or ureaplasma.

Some bacterial infections, such as chlamydia and mycoplasma or ureaplasma, which are sexually transmitted infections, can be prevented by using condoms during sex.

Other infections that can cause stillbirths include:

- rubella – commonly known as German measles

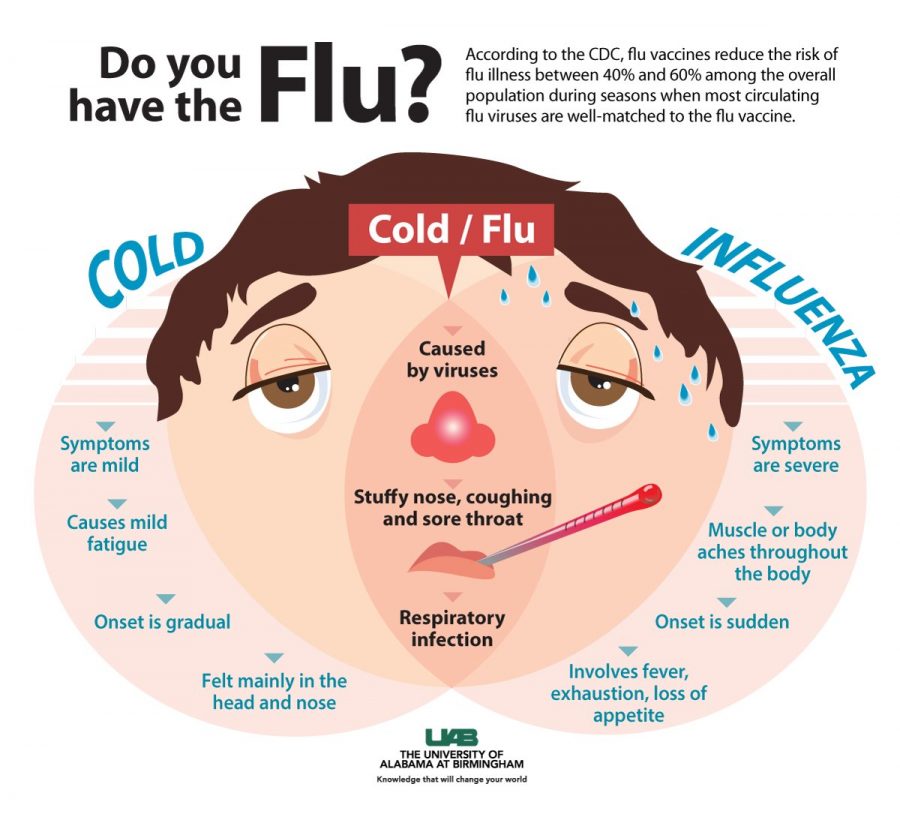

- flu – it's recommended that all pregnant women have the seasonal flu vaccine, regardless of stage of pregnancy

- parvovirus B19 – this causes slapped cheek syndrome, a common childhood infection that's dangerous for pregnant women

- coxsackie virus – this can cause hand, foot and mouth disease in humans

- cytomegalovirus – a common virus spread through bodily fluids, such as saliva or urine, which often causes few symptoms in the mother

- herpes simplex – the virus that causes genital herpes and cold sores

- listeriosis – an infection that usually develops after eating food contaminated by listeria bacteria (see foods to avoid in pregnancy)

- leptospirosis – a bacterial infection spread by animals such as mice and rats

- Lyme disease – a bacterial infection spread by infected ticks

- Q fever – a bacterial infection caught from animals such as sheep, goats and cows

- toxoplasmosis – an infection caused by a parasite found in soil and cat faeces

- malaria – a serious tropical disease spread by mosquitoes

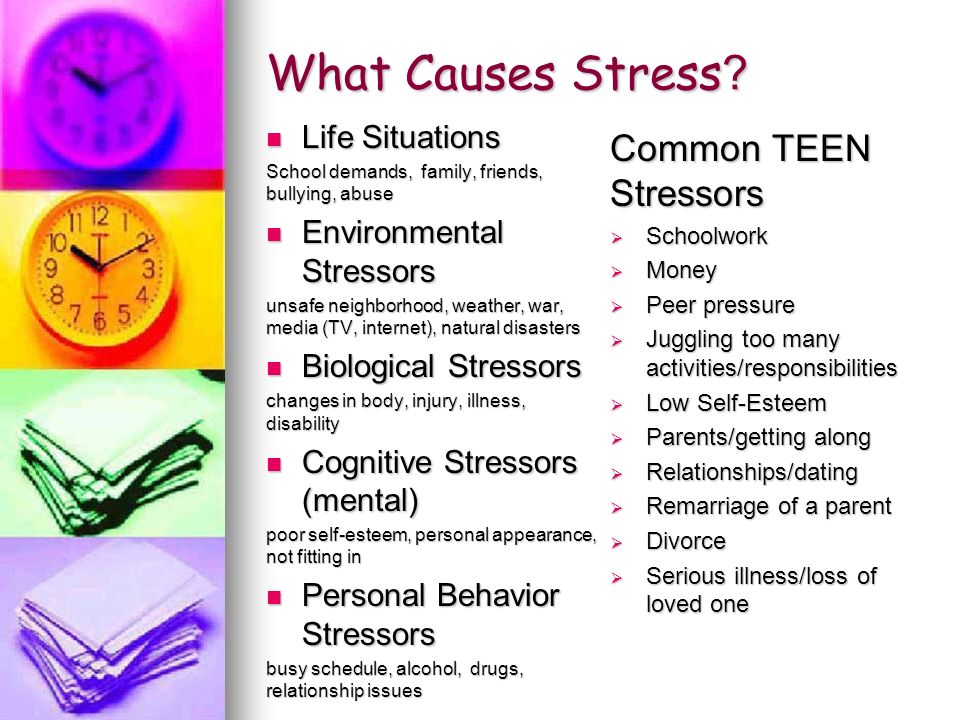

Increased risk

There are also a number of things that may increase your risk of having a stillborn baby, including:

- having twins or a multiple pregnancy

- having a baby who doesn't grow as they should in the womb

- being over 35 years of age

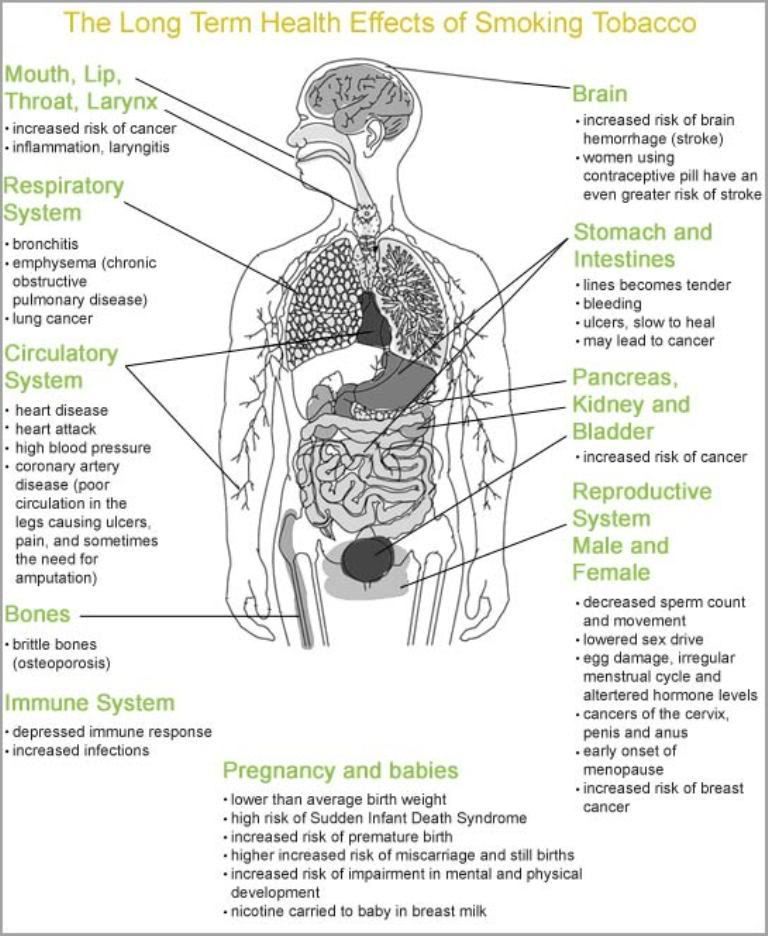

- smoking, drinking alcohol or misusing drugs while pregnant

- being obese – having a body mass index above 30

- having a pre-existing physical health condition, such as epilepsy

Your baby's growth

Your midwife will check the growth and wellbeing of your baby at each antenatal appointment and plot the baby's growth on a chart.

Every baby is different and should grow to the size that's normal for them. Some babies are naturally small, but all babies should continue to grow steadily throughout pregnancy.

If a baby is smaller than expected or their growth pattern tails off as the pregnancy continues, it may be because the placenta isn't working properly. This increases the risk of stillbirth.

Problems with a baby's growth should be picked up during antenatal appointments.

Your baby's movements

It's important to be aware of your baby's movements and know what's normal for your baby.

Tell your midwife immediately if you notice the baby's movements slowing down or stopping. Don't wait until the next day.

See preventing stillbirth for more information.

Page last reviewed: 16 March 2021

Next review due: 16 March 2024

Stillbirth: Definition, Causes & Prevention

Overview

What is a stillbirth?

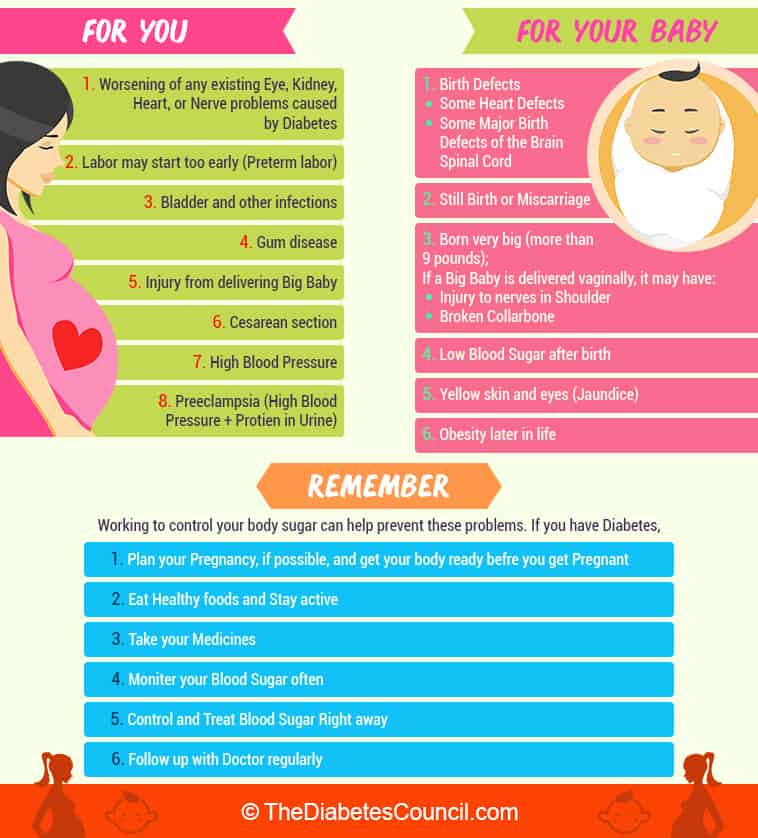

A stillbirth is when a fetus dies after the mother’s 20th week of pregnancy. The fetus may have died in the uterus weeks or hours before labor. Rarely, the fetus may die during labor. Although prenatal care has drastically improved over the years, the reality is stillbirths still happen and often go unexplained.

The fetus may have died in the uterus weeks or hours before labor. Rarely, the fetus may die during labor. Although prenatal care has drastically improved over the years, the reality is stillbirths still happen and often go unexplained.

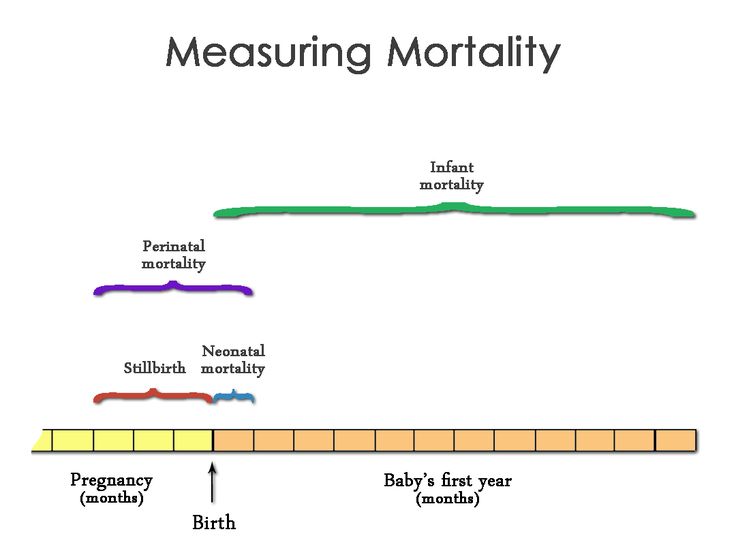

A stillbirth is classified as either an early stillbirth, a late stillbirth, or a term stillbirth. Those types are determined by the number of weeks of pregnancy:

- Early stillbirth: The fetus dies between 20 and 27 weeks.

- Late stillbirth: The fetus dies between 28 and 36 weeks.

- Term stillbirth: The fetus dies the 37th week or after.

How common are stillbirths?

A stillbirth occurs in about one of 160 births (about 24,000 babies per year in the United States).

Who is at risk of having a stillbirth?

A stillbirth can happen to pregnant people of any age, background, or ethnicity. They can be unpredictable — 1 in 3 cases go unexplained. There are some ways you can reduce your risk, though. You’re more likely to have a stillbirth if you:

You’re more likely to have a stillbirth if you:

- Smoke, drink alcohol, or use recreational drugs.

- Are over the age of 35.

- Have poor prenatal care.

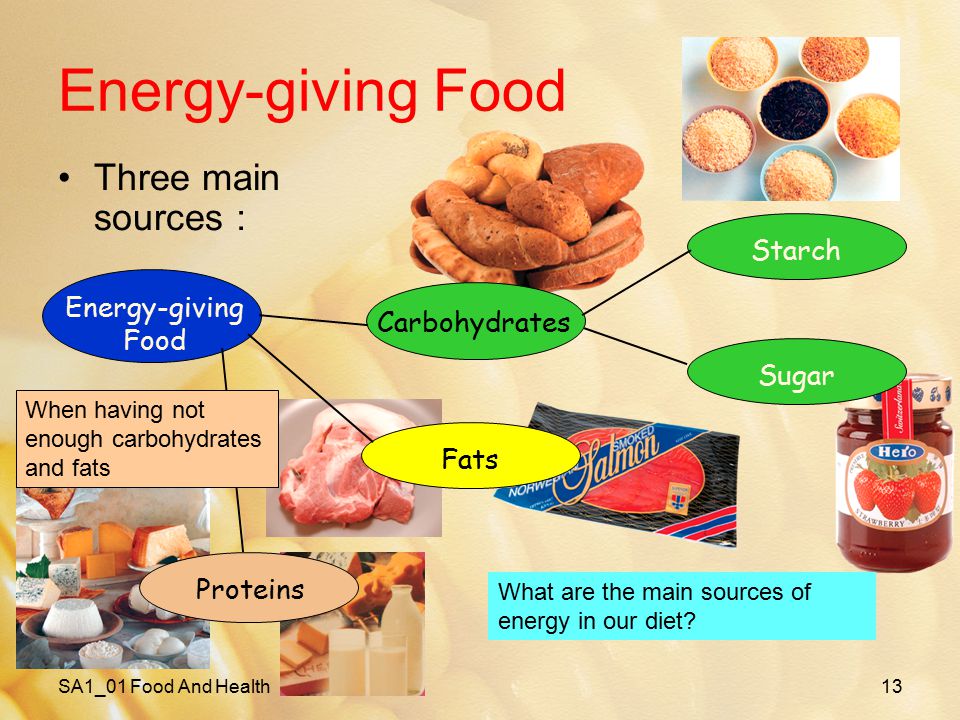

- Are malnourished.

- Are Black.

- Are having multiple births (twins or more).

- Have a preexisting health condition.

- Have obesity (body mass index above 30).

What’s the difference between a stillbirth and a miscarriage?

Like a stillbirth, a miscarriage is also a pregnancy loss. However, while a stillbirth is the loss of a fetus after 20 weeks of pregnancy, a miscarriage happens before the 20th week.

Symptoms and Causes

What causes a stillbirth?

The cause of the stillbirth is vital not only for the healthcare providers to know, but for the parents to help with the grieving process. The cause is not always known (1 in 3 stillbirths cannot be explained), but the most likely causes include:

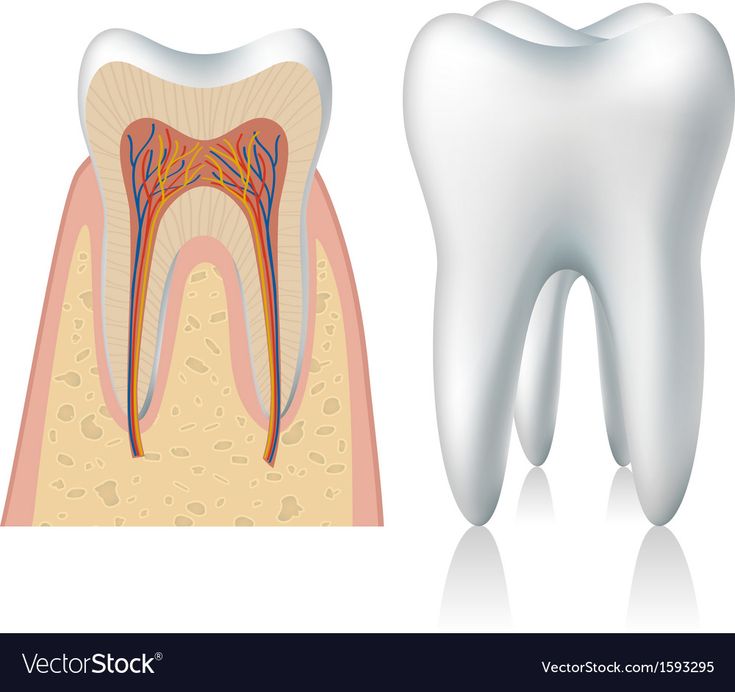

- Problems with the placenta and/or the umbilical cord.

Your placenta is an organ that lines your uterus when you’re pregnant. Through it and the umbilical cord, the fetus gets blood, oxygen and nutrients. Any problems with your placenta or umbilical cord and the fetus will not develop properly.

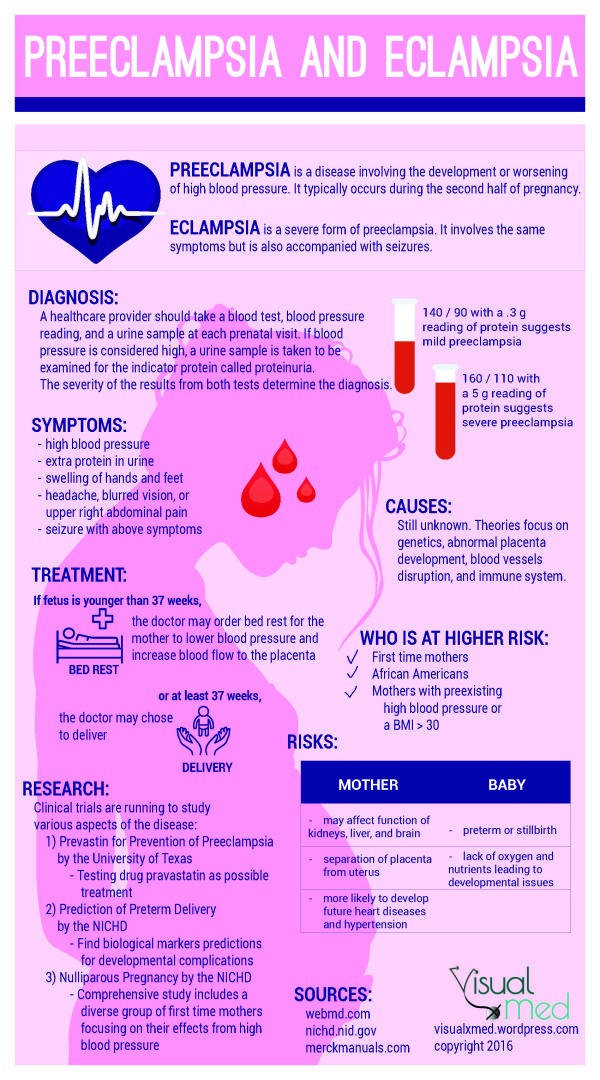

Your placenta is an organ that lines your uterus when you’re pregnant. Through it and the umbilical cord, the fetus gets blood, oxygen and nutrients. Any problems with your placenta or umbilical cord and the fetus will not develop properly. - Preeclampsia. Preeclampsia is high blood pressure and swelling that often happens late in pregnancy. If you have preeclampsia, you have twice the risk of placental abruption or stillbirth.

- Lupus. A person who has lupus is at risk of having a stillbirth.

- Clotting disorders. A person with a blood clotting disorder like hemophilia is at a high risk.

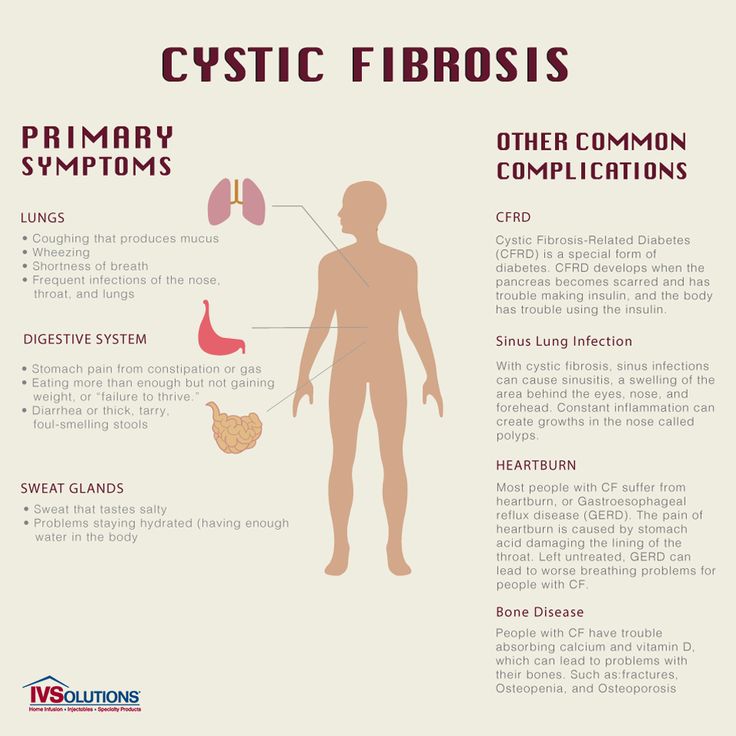

- The pregnant person's medical conditions. Other illnesses can sometimes cause stillbirths. The list includes diabetes, heart disease, thyroid disease, or a viral or bacterial infection.

- Lifestyle. If your lifestyle includes drinking, using recreational drugs and/or smoking, you’re more likely to have a stillbirth.

- Birth defects. One or more birth defects cause about 25% of stillbirths. Birth defects are rarely discovered without a thorough examination of the fetus, including an autopsy.

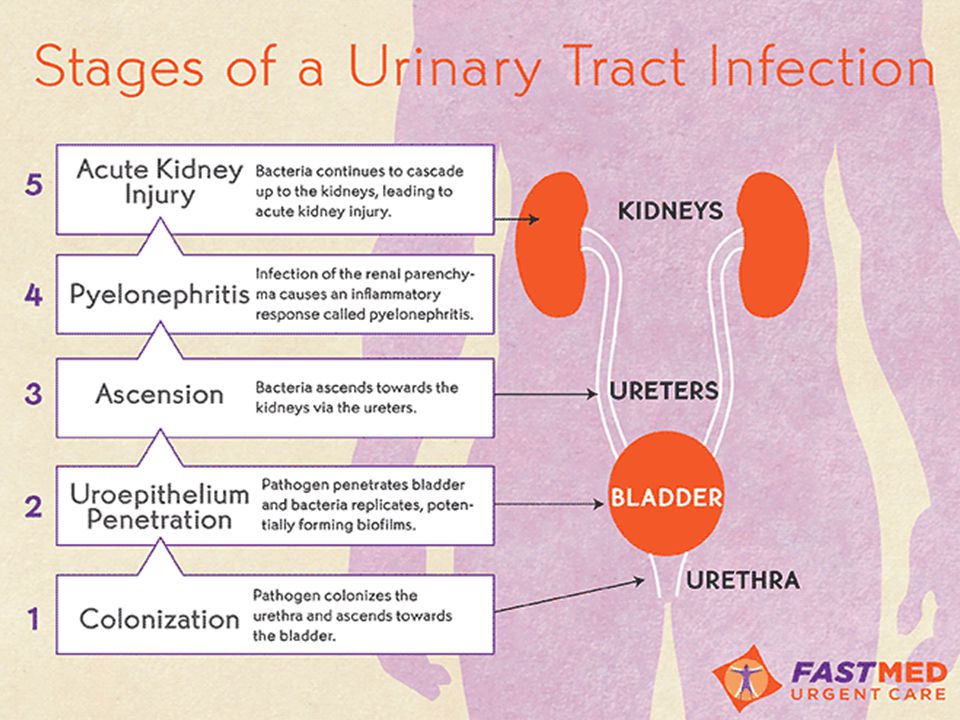

- Infection. An infection between week 24 and week 27 can cause fetal death. Usually, it’s a bacterial infection that travels from your vagina to your uterus. Common bacteria include Group B Streptococcus, E. coli, klebsiella, enterococcus, Haemophilus influenza, chlamydia and mycoplasma or ureaplasma. Additional problems include rubella, the flu, herpes, Lyme disease and malaria, among others. Some infections go unnoticed until there are serious complications.

- Trauma. Trauma such as a car crash can result in a stillbirth.

- Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP). Also known as obstetric cholestasis, this is a liver disorder that includes severe itching.

What physical symptoms does the mother have after stillbirth?

If you have a fever, bleeding, chills, or pain, be sure to contact your healthcare provider right away because these may be signs of an infection.

Will I lactate after a stillbirth?

After the delivery of the placenta, the milk-producing hormones may be activated (lactation). You might start to produce breast milk. Unless you have preeclampsia, you can take medicines called dopamine agonists that may stop your breasts from producing milk. You can also choose to let the lactation stop naturally.

Does stillbirth cause infertility?

No. A stillbirth does not cause infertility and it doesn’t indicate that there is a problem with it.

Diagnosis and Tests

How is the diagnosis made?

Usually, you’ll notice that the fetus isn’t as active as it used to be. An ultrasound will confirm if the fetus has passed.

How can I find out what caused my stillbirth?

To discover the cause, your healthcare provider will perform one or more of the following tests:

- Blood Tests. Blood tests will show if you have preeclampsia, obstetric cholestasis or diabetes.

- Examination of the umbilical cord, membranes and placenta.

These tissues attach to your fetus. An abnormality could prevent the fetus from receiving oxygen, blood and nutrients.

These tissues attach to your fetus. An abnormality could prevent the fetus from receiving oxygen, blood and nutrients. - Tests for infection. Healthcare providers will take a sample of your urine, blood, or cells from your vagina or cervix to test for infection.

- Thyroid function test. This test will determine if there’s something wrong with your thyroid gland.

- Genetic tests. Your healthcare provider will take a sample of the umbilical cord to determine if the fetus had genetic problems such as Down’s syndrome.

Your healthcare provider will also review medical records and the circumstances surrounding the stillbirth. With your consent, an autopsy can be performed to determine the cause of fetal death. An autopsy is a surgical procedure performed by a skilled pathologist. Incisions are made carefully to avoid disfigurement, and the incisions are surgically repaired afterward. You have the right to limit the autopsy to eliminate any incisions on your baby that are uncomfortable for you. Be sure to write these requests on the autopsy permission form.

Be sure to write these requests on the autopsy permission form.

Some hospitals don't perform autopsies, so your baby may have to be transported to another hospital. Be sure you feel comfortable with where your child is being taken. You also have the right to deny an autopsy, if that is your wish.

An autopsy may be legally required in some cases, including when:

- A baby died within 24 hours of a surgical operation.

- A healthcare provider can't certify the cause of death.

- A baby was alive and then died suddenly.

Management and Treatment

What happens after a stillborn baby passes away?

If the fetus passes away before you’re in labor, you have three options:

- Induced labor.

- Natural birth.

- Cesarean section.

Induced labor. Healthcare providers recommend induced labor as the best option after a stillbirth. It should be done immediately if you:

- Have severe preeclampsia (high blood pressure).

- Have a serious infection.

- Have a broken amniotic sac (the bag of water around the fetus).

- Have any clotting disorder.

The labor is induced using medicine dispensed in one of five ways:

- A tablet inserted into your vagina.

- A gel inserted into your vagina.

- A swallowed tablet.

- A drip into a vein.

- A Foley bulb. A mechanical balloon that widens the cervix.

Natural birth. Waiting for birth to happen naturally is an option but, as time goes by, the fetal body may deteriorate in your uterus. The fetus may look different than you expect. The deterioration also makes it more difficult to determine the cause of death.

Cesarean section. A cesarean section is not recommended because it’s not as safe as a natural birth or induced labor.

What happens after a stillborn baby is delivered?

You'll be able to hold your baby, and your healthcare providers will allow you as much time as you need to spend with your child. You may feel uncomfortable with this idea at first.

You may feel uncomfortable with this idea at first.

You may want to ask for any mementos and keepsakes of your child, such as a blanket, a lock of your child’s hair, the hospital ID bracelet, etc. You can take pictures. This may also be uncomfortable, but it may be a cherished possession at a later time and may help you during your grieving process. Most hospitals will issue the family a birth certificate, but make sure you ask and request that it include the baby's handprints and footprints.

Prevention

Can a stillbirth be prevented?

Usually, a stillbirth can't be prevented. It often occurs because the fetus wasn't developing normally. Generally, improving your health, including managing preexisting conditions and lifestyle choices, increases your chances of a successful pregnancy. You’re also less likely to have a stillbirth if, when you know you’re high-risk, you’re carefully monitored through routine ultrasounds and/or fetal heart rate monitoring. If your healthcare provider finds a problem, they can have your baby delivered early if necessary.

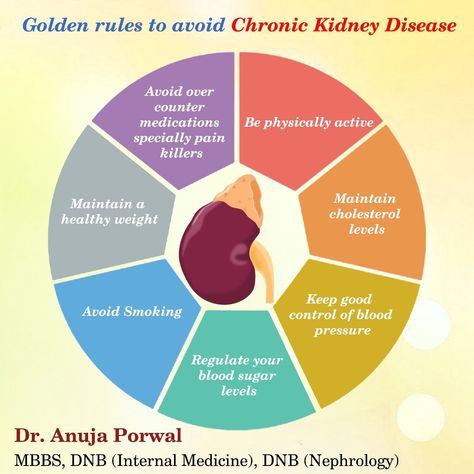

How can I reduce my risk of having a stillbirth?

Because the reason why a stillbirth happens isn't always understood, it is difficult to prevent. However, there are some steps you can take to increase your chances of having a healthy baby:

- Avoid recreational drugs, smoking and drinking alcohol.

- Contact your healthcare provider if there’s any bleeding during the second half of your pregnancy.

- Do what’s called a daily “kick count.” Around 26-28 weeks, familiarize yourself with fetal movements. Figure out what’s normal for the fetus. Then, if they stop acting normally, contact your healthcare provider.

- Before you get pregnant, work toward a weight that's healthy for you. If you’re already pregnant, talk with your healthcare provider about diet and exercise options.

- Protect yourself against infections.

- Avoid certain foods including some types of fish and some types of cheese. Also, double-check to make sure that any meat or poultry you eat is thoroughly cooked.

- Report any stomach pain, itching, or vaginal bleeding immediately.

- Sleep on your side, not your back. If you’ve been pregnant for 28 weeks or more, sleeping on your back can double the risk of stillbirth. It’s not completely clear why that makes a difference, but experts suspect that it has something to do with the flow of blood and oxygen to the fetus.

- Get routine tests, including your blood pressure and urine. These will help your healthcare provider see if there are any illnesses or conditions that may affect the health of your baby.

Can the food I eat prevent stillbirth?

Unfortunately, eating or avoiding a specific food can’t guarantee you won’t have a stillbirth. However, there are some foods you should stay away from to improve the chances of a healthy pregnancy in general. Avoid the following:

- Mold-ripened soft cheeses and soft blue cheeses.

- Unpasteurized milk and unpasteurized milk products.

- Raw or undercooked meat.

- Liver products.

- Pâté.

- Game meats.

- Raw or partially cooked eggs.

- Duck, goose or quail eggs.

- Swordfish, marlin, shark and raw shellfish.

- Limit caffeinated drinks and herbal teas.

Outlook / Prognosis

When should I see my healthcare provider after the natural birth or induced labor?

You’ll likely have a follow-up appointment with your healthcare provider a few weeks later. At that time the post-mortem and test results will be discussed and you can voice concerns about future pregnancies.

Can I get pregnant after I've delivered a stillborn baby?

Yes. Most people who deliver stillborn babies go on to have normal pregnancies and births. If the stillbirth was caused by a birth defect or umbilical cord problem, the chances of another stillbirth is slight. If the cause was an illness the pregnant person has or a genetic disorder, the risk is somewhat higher. The chance that your next pregnancy will result in stillbirth is about 3%, which means that most post-stillbirth pregnancies result in healthy babies.

How long after a stillbirth should I get pregnant again?

Discuss the timing of your next pregnancy with your healthcare provider to make sure you are physically ready to begin a new pregnancy. Some healthcare providers recommend waiting a certain amount of time (from six months to one year) before trying to conceive again. Some studies have shown that people who wait at least one year to conceive may have less depression and anxiety during a later pregnancy.

Statistics show that about 60% of couples take up to six months to conceive after delivery of a stillborn baby, and another 30% take up to 12 months. Don't be surprised if things don't happen quickly.

Living With

Is a funeral necessary after a stillbirth?

After the death of your baby, one of the first decisions you will be faced with is whether or not to need to arrange a funeral.

The type of arrangements you make may play an important role in the grieving process. It is a decision that only you and the other parent can make together. You may find that you need time to make your decisions and arrangements. It is quite common for families to take up to a week (and sometimes longer) to make arrangements. This is okay.

You may find that you need time to make your decisions and arrangements. It is quite common for families to take up to a week (and sometimes longer) to make arrangements. This is okay.

No matter what your choice is, you have the right to change your mind. Be sure you ask whoever is carrying out your arrangements about how long you have to make any changes.

How should I communicate with my other children after a stillbirth?

You may find your children are a comfort, a worry, or just too hard to deal with. These are normal reactions. Take time to grieve and say goodbye to the child you lost. You will eventually feel normal feelings for your living children again, and the bond you have with them may possibly become stronger.

No matter how much you may want to shelter your children from pain, they can sense the emotion around them. Honesty is the best way to help your children cope with this painful experience. Children have a different understanding of death at different developmental stages.

What can I do to cope with a stillbirth?

Take as much time as you need to heal physically and emotionally after a stillbirth. Regardless of the stage of pregnancy during which your loss occurred, you are still a parent and the life you nurtured was real. It is completely normal for you to experience depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Above all, don't blame yourself. Give yourself time to cope, grieve and accept your devastating loss.

Counseling is available. Pregnancy loss support groups may also be a good resource for both parents. Ask your healthcare provider for more information about counseling and support groups.

What questions should I ask my healthcare provider after a stillbirth?- What was the cause of the stillbirth?

- Is there anything else I can do to prevent a stillbirth in the future?

- Do you recommend a psychiatrist?

- Do you recommend a counselor?

- Do you recommend a support group?

- How soon do you recommend I get pregnant again?

- Does this hospital keep records of stillbirths?

- Can I get a copy of the records/birth certificate?

- When should I return for another appointment?

- How will I be cared for in the next pregnancy?

A note from Cleveland Clinic

A stillbirth can be devastating. It can be overwhelming and depressing for the parents, their children, the grandparents, and other family members and friends. The grieving can be even worse when a stillbirth happens for no known reason. Remember that it’s normal to have difficulty coping. Access mental health professionals if you need help.

It can be overwhelming and depressing for the parents, their children, the grandparents, and other family members and friends. The grieving can be even worse when a stillbirth happens for no known reason. Remember that it’s normal to have difficulty coping. Access mental health professionals if you need help.

Stay in contact with your healthcare providers before, during and after your pregnancy. Share your worries and ask questions. Do your best to avoid risk factors such as smoking and drinking. Also, remember that if you’ve had a stillbirth, you can get pregnant again. There is a 3% chance of another stillbirth.

Modern views on the problem of classification and determination of the causes of stillbirth

Modern views on the problem of classification and determination of the causes of stillbirth Website of the publishing house "Media Sfera"

contains materials intended exclusively for healthcare professionals. By closing this message, you confirm that you are a registered medical professional or student of a medical educational institution.

All orders placed after December 29, 2022 will be shipped on January 10, 2023.

Volkov V.G.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tula State University

Kastor M.V.

Medical Institute of Tula State University, Tula, Russia

Modern views on the problem of classification and determination of the causes of stillbirth

Authors:

Volkov V.G., Kastor M.V. nine0006

More about the authors

Magazine: Russian Bulletin of an obstetrician-gynecologist. 2020;20(3): 29‑34

DOI: 10.17116/rosakush30202003129

How to quote:

Volkov V.G., Kastor M.V. Modern views on the problem of classification and determination of the causes of stillbirth. nine0035 Russian Bulletin of an obstetrician-gynecologist. 2020;20(3):29‑34.

Volkov VG, Kastor MV. Modern view of classification and determination of the causes of stillbirth. Russian Bulletin of Obstetrician-Gynecologist. 2020;20(3):29‑34. (In Russ.).

2020;20(3):29‑34. (In Russ.).

https://doi.org/10.17116/rosakush30202003129

Read metadata

The review presents modern approaches to the classification of causes of stillbirth and associated conditions (risk factors), in particular, the approach adopted by the World Health Organization in the context of the application of the International Classification of Diseases of the 10th revision. A systematic review of other existing classification systems that have been used in the world in recent years has been carried out. A comparison was made of individual world indicators related to the causes of stillbirth with those existing in Russia. The problems of the causes of stillbirth are discussed, in particular, the role of intrauterine fetal hypoxia and placental insufficiency, which most often mask the true causes of stillbirth. Foreign experience in building predictive mathematical models - stillbirth calculators and the possibility of their application are also considered. nine0006

nine0006

Keywords:

stillbirth

perinatal mortality

risk factors for stillbirth

classification of causes of stillbirth

stillbirth calculator

Authors:

Volkov V.G.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tula State University

Kastor M.V.

Medical Institute, Tula State University, Tula, Russia

References:

- Heazell A. Stillbirth — a challenge for the 21st century. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:1:388. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1181-8

- WHO application of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) to perinatal deaths (ICD-PS). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

- Leisher S, Teoh Z, Reinebrant H, Allanson E, Blencowe H, Erwich J, Frøen J, Gardosi J, Gordijn S, Gülmezoglu A, Heazell A, Korteweg F, Lawn J, McClure E, Pattinson R, Smith G, Tunçalp Ӧ, Wojcieszek A. and Flenady V. Classification systems for causes of stillbirth and neonatal death, 2009—2014: an assessment of alignment with characteristics for an effective global system.

BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:1:269. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1040-7

BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:1:269. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1040-7 - Humphrey-Murto S, Varpio L, Wood TJ, Gonsalves C, Ufholz L.A, Mascioli K, Wang C, Foth T. The use of the Delphi and other consensus group methods in medical education research: A Review. Acad. Med. 2017;92:10:1491-1498. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000001812

- Wojcieszek A, Reinebrant H, Leisher S, Allanson E, Coory M, Erwich J, Frøen J, Gardosi J, Gordijn S, Gulmezoglu M, Heazell A, Korteweg F, McClure E, Pattinson R, Silver R, Smith G, Teoh Z, Tunçalp Ö. and Flenady V. Characteristics of a global classification system for perinatal deaths: a Delphi consensus study. B M C Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:1:223. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0993-x

- Frøen J, Pinar H, Flenady V, Bahrin S, Charles A, Chauke L, Day K, Duke C, Facchinetti F, Fretts R, Gardener G, Gilshenan K, Gordijn S, Gordon A, Guyon G, Harrison C, Koshy R, Pattinson R, Petersson K, Russell L, Saastad E, Smith G.

and Torabi R. Causes of death and associated conditions (Codac) — a utilitarian approach to the classification of perinatal deaths. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. nine0073 2009;9:1:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-9-22

and Torabi R. Causes of death and associated conditions (Codac) — a utilitarian approach to the classification of perinatal deaths. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. nine0073 2009;9:1:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-9-22 - Sharma B, Prasad G, Aggarwal N, Siwatch S, Suri V, Kakkar N. Aetiology and trends of rates of stillbirth in a tertiary care hospital in the north of India over 10 years: a retrospective study. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;126(4):14-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15850

- Firth C, Petherick E, Oddie SJ. Infant deaths from congenital anomalies: novel use of Child Death Overview Panel data. nine0072 Arch DisChild. 2018;103:11:1027-1032. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2017-314256

- Basu M, Johnsen I, Wehberg S, Sørensen R, Barington T, Nørgård B. Causes of death among full term stillbirths and early neonatal deaths in the Region of Southern Denmark. J Perinat Med. 2018;46:2:197-202. https://doi.

org/10.1515/jpm-2017-0171

org/10.1515/jpm-2017-0171 - Yerlikaya G, Akolekar R, McPherson K, Syngelaki A, Nicolaides K. Prediction of stillbirth from maternal demographic and pregnancy characteristics. nine0072 Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48:5:607-612. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.17290

- Haruyama R, Gilmour S, Ota E, Abe SK, Rahman MM, Nomura S, Miyasaka N, Shibuya K. Causes and risk factors for singleton stillbirth in Japan: Analysis of a nationwide perinatal database, 2013–2014. Science Rep. 2018;8:1:4117. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22546-9

- Reinebrant H, Leisher S, Coory M, Henry S, Wojcieszek A, Gardener G, Lourie R, Ellwood D, Teoh Z, Allanson E, Blencowe H, Draper E, Erwich J, Frøen J, Gardosi J, Gold K, Gordijn S, Gordon A, Heazell A, Khong T, Korteweg F, Lawn J, McClure E, Oats J, Pattinson R, Pettersson K, Siassakos D, Silver R, Smith G, Tunçalp Ö. and Flenady V. Making stillbirths visible: a systematic review of globally reported causes of stillbirth.

nine0072 BJOG: Intl J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;125:2:212-224. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14971

nine0072 BJOG: Intl J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;125:2:212-224. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14971 - Kurtser M.A., Kutakova Yu.Yu., Songolova E.N., Belousova A.V., Kask L.N., Chemezov A.S. Syndrome of sudden fetal death. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2011;7-1:79-83.

- Shchegolev A.I., Tumanova U.N., Shuvalova M.P., Frolova O.G. Comparative analysis of stillbirths in the Russian Federation in 2010 and 2012. Russian Bulletin of Perinatology and Pediatrics. nine0073 2015;60:3:58-62.

- Konovalov O.E., Kharitonov A.K. Modern trends in perinatal and neonatal mortality in the Moscow region. Bulletin of RUDN University. Series: Medicine; 2016;1:135-140.

- Korotova S.V., Fatkullina I.B., Namzhilova L.S., Li-Wan-Hai A.V., Borgolov A.V., Fatkullina Yu.N. A modern view on the problem of antenatal fetal death. Siberian medical journal (Irkutsk). 2014;7:5-10.

- Tumanova U.N., Schegolev A.I. Placental lesions in the genesis of stillbirth (literature review).

nine0072 International Journal of Applied and Basic Research. 2017;3:77-81.

nine0072 International Journal of Applied and Basic Research. 2017;3:77-81. - Barinova I.V. Pathogenesis of antenatal death: phenotypes of fruit losses and thanatogenesis. Russian Bulletin of an obstetrician-gynecologist. 2015;15:1:68-78. https://doi.org/10.17116/rosakush301515168-76

- Granatovich N.N., Frolova E.R. Regional aspects of stillbirth. Bulletin of new medical technologies. 2018; 25:3:223-226.

- Martynenko P.G., Volkov V.G., Granatovich N.N., Khromushin V.A. Analysis of risk factors for perinatal mortality and the level of medical care. nine0072 Bulletin of new medical technologies. 2008;15:3:213-214.

- Martynenko P.G., Volkov V.G., Khromushin V.A. Predicting preterm birth: results of algebraic modeling based on constructive logic. Bulletin of new medical technologies. 2009;17:1:210-213.

- Gazieva I.A., Remizova I.I., Chistyakova G.N., Deryabina E.G. Prognostic significance of clinical, anamnestic, microbiological and biochemical factors in the genesis of early reproductive losses not associated with fetal chromosomal abnormalities.

nine0072 Russian Bulletin of an obstetrician-gynecologist. 2014;14:5:54-59.

nine0072 Russian Bulletin of an obstetrician-gynecologist. 2014;14:5:54-59. - Helgadóttir LB, Turowski G, Skjeldestad FE, Jacobsen AF, Sandset PM, Roald B, Jacobsen EM. Classification of stillbirths and risk factors by cause of death - a case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92:3:325-333. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12044

- Shlyakhtenko T.N., Alyabyeva E.A., Arzhanova O.N., Selkov S.A., Pluzhnikova T.A., Chepanov S.V. Antiphospholipid syndrome in miscarriage. nine0072 Journal of Obstetrics and Women's Diseases. 2015;64:5:69-76.

- Trudell A, Tuuli M, Colditz G, Macones G, Odibo A. A stillbirth calculator: Development and internal validation of a clinical prediction model to quantify stillbirth risk. PLoS ONE. 2017; 12:3:e0173461. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173461

- Dicke G.B. Tobacco smoking among women and a strategy for successful smoking cessation during pregnancy. Pharmateka. 2014;4:76-79.

- Chursina O.A., Konstantinova O.D., Sennikova Zh.V., Demina L.M., Loginova E.A. The influence of active and passive smoking on the course of pregnancy and childbirth. Russian Bulletin of an obstetrician-gynecologist. 2019;19:4:47-52. https://doi.org/10.17116/rosakush30191904147

- Ryzhkov V.V., Kopylov A.V., Koltunov E.N., Kulakova E.V., Kontlokova O.R. Perinatal aspects of intrauterine infections. Russian Bulletin of an obstetrician-gynecologist. 2017;17:4:33-36. https://doi.org/10.17116/rosakush301717433-36

- Belova A.V., Astsaturova O.R., Naumenko N.S., Nikonov A.P. Genital herpes and pregnancy. Archive of Obstetrics and Gynecology named after V.F. Snegirev. 2017;4:3:124-130.

- Krasnopolsky V.I., Zarochentseva N.V., Mikaelyan A.V., Keshchyan L.V., Lazareva I.N. The role of human papillomavirus infection in the pathology of pregnancy and outcome for the newborn (modern concepts). Russian Bulletin of an obstetrician-gynecologist.

2016;16:2:30-36. https://doi.org/10.17116/rosakush301616230-36

2016;16:2:30-36. https://doi.org/10.17116/rosakush301616230-36 - Volkov V.G. Perinatal mortality among HIV-infected pregnant women. HIV infection and immunosuppression. 2017;9:3:98-102. https://doi.org/10.22328/2077-9828-2017-9-3-98-102

- Askhakov M.S., Chebotarev V.V., Chebotareva N.V. Modern approach of obstetricians-gynecologists to the treatment of chlamydial infection in pregnant women and its validity. Modern problems of science and education. 2018;3:62. https://doi.org/10.17513/spno.27686 nine0201

Close metadata

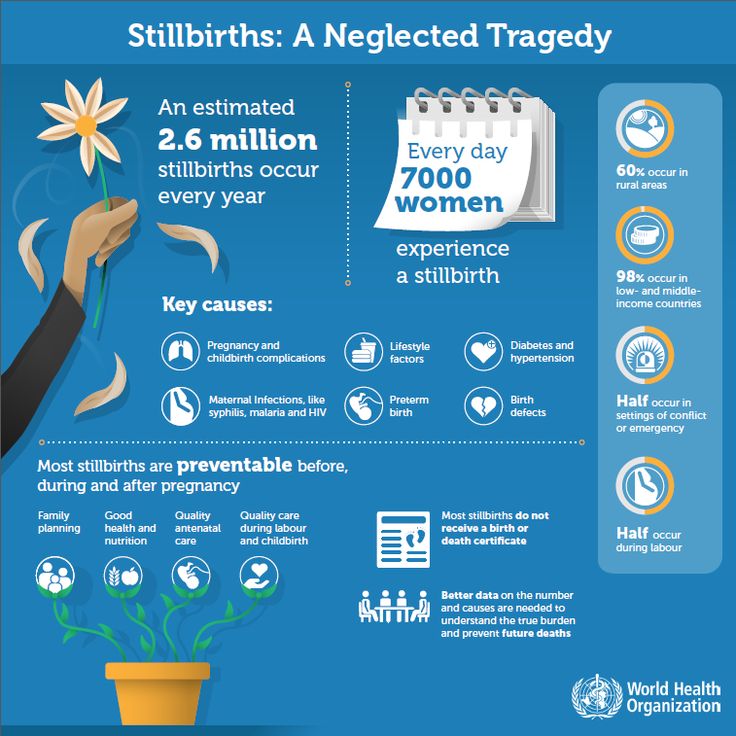

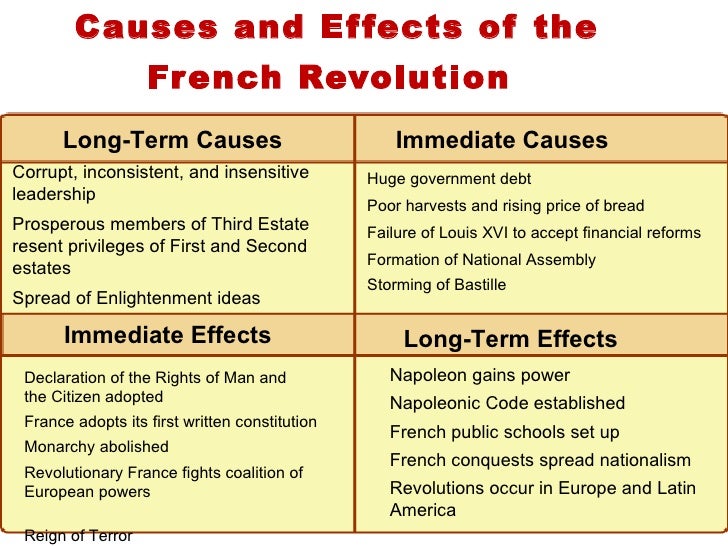

Stillbirth (SR) remains a significant global problem, with more than 2.6 million cases worldwide each year, 98% of which occur in low- or middle-income countries. MR is a negative socio-psychological factor and worsens the reproductive prognosis [1].

Within the framework of the International Classification of Diseases X Revision (ICD-10), the cause of death is determined in stages, in accordance with the development of the initial clinical conditions that led to the death. The principles for applying the ICD-10 to cases of perinatal deaths (PS) are set out in the official WHO document, the ICD-PS [2]. nine0006

The principles for applying the ICD-10 to cases of perinatal deaths (PS) are set out in the official WHO document, the ICD-PS [2]. nine0006

The underlying disease or condition of the fetus (child) is defined in ICD-10 as the disease or condition that caused the pathological chain that led to death. This is the only reported cause of death and should therefore be reported as accurately as possible.

In 2016, a working group of WHO experts jointly decided on the underlying structure of the ICD-PS in preparation for the ICD-11. During the preparatory work, a systematic review was made of more than 80 existing PS classification systems used in the world in 2009—2014 [3]. A survey was also conducted using the Delphi method [4], which identified 17 main characteristics of an effective PS classification system, and the relationships between these key characteristics and existing classification systems (table) [5] were analyzed.

Key features of an effective PS classification system [5] The consensus reached allowed for the advocacy of changes to existing ICD-10 codes in order to optimize the mechanisms for determining the causes of PS. It was determined that the PS classification system should be globally applicable, based on existing ICD-10 rules and be compatible with the ICD-11 under development. nine0006

It was determined that the PS classification system should be globally applicable, based on existing ICD-10 rules and be compatible with the ICD-11 under development. nine0006

When analyzing the available classification systems for MR and PS, it turned out that 82% of them satisfy 4 or less characteristics out of 17. The best of the available classification systems, Causes of Death and Associated Conditions (CODAC), satisfies only 9 characteristics out of 17 [6].

Among the shortcomings in the classification of causes of MR and PS in ICD-10, the authors of the CODAC system indicate that ignoring the consistent identification of the fetus as a separate whole (instead, the umbilical cord, placenta, membranes are considered separately) leads to the absence of special codes for many significant lesions of the placenta, etc. Therefore, the classification system for MR and PS cannot be based solely on the revision and refinement of ICD-10 codes. The effectiveness of a PS classification system cannot be due solely to the simplicity of such a system, the strict definition and differentiability of rubrics, and even statistical reliability - otherwise one would have to prefer a classification system containing as little information as possible. A utilitarian approach to the classification of MR and PS should take into account the majority of clinically diverse causes of PS, while maintaining simplicity and reproducibility of the main rubrics, preserving important details through extensive subrubs (multilevel). nine0006

A utilitarian approach to the classification of MR and PS should take into account the majority of clinically diverse causes of PS, while maintaining simplicity and reproducibility of the main rubrics, preserving important details through extensive subrubs (multilevel). nine0006

The CODAC system contains 94 subheadings (577 in the full version). The cause of MR according to CODAC is an event, disease, or condition of sufficient severity, intensity, and duration that a significant proportion of MR cases can be expected among similar clinical situations.

CODAC MR comorbid condition is an event, disease, or condition of sufficient severity, intensity, and duration to contribute to explaining the cause of MR in a significant proportion of MR cases among similar clinical situations. nine0006

CODAC death mechanisms are biological pathways or chains of events initiated by the cause of MR that consistently and irreversibly lead to the same outcome.

It should be emphasized that only the causes and associated conditions of MR are coded in CODAC, not the mechanisms. For example, placental infarction (the cause of MR) initiates hypoxic-ischemic disorders leading to damage to the fetal brain. Placental infarction can also lead to placental abruption (the cause of MR), although not immediately, hypoxic-ischemic damage to the fetal brain also develops before this. In the considered cases, placental infarction and placental abruption can be considered the cause of MR, but not damage to the fetal brain (mechanism of death). nine0006

For example, placental infarction (the cause of MR) initiates hypoxic-ischemic disorders leading to damage to the fetal brain. Placental infarction can also lead to placental abruption (the cause of MR), although not immediately, hypoxic-ischemic damage to the fetal brain also develops before this. In the considered cases, placental infarction and placental abruption can be considered the cause of MR, but not damage to the fetal brain (mechanism of death). nine0006

The CODAC system was developed specifically for national PS monitoring in the UK and continues to be widely used throughout the world [7–11].

According to the British report in 2013, 47% of cases of PS were attributed to unknown causes of death, in 2014 - 46% of cases [3]. On average, according to WHO data for 2009-2016. [12], even in high-income countries, MR remains unexplained in 37.1% of cases. In 14.4% of cases, the cause of MR was complications of childbirth associated with bleeding; at 9.3% of cases - placental complications; in 8. 4% of cases - intrauterine malformations (CM). Perinatal hypoxia as a cause of MR is not found in all reports, in the 5 highest quality reports on MR it is indicated in only 1.0%.

4% of cases - intrauterine malformations (CM). Perinatal hypoxia as a cause of MR is not found in all reports, in the 5 highest quality reports on MR it is indicated in only 1.0%.

In the Russian Federation, the causes of MR and concomitant conditions of the fetus and mother are coded in certificates of perinatal death according to the rules of ICD-10 (form 106-2/u-08). In 2008-2011 in Moscow, an analysis was made of 1320 cases of MR with symptoms of intrauterine hypoxia. In 96.1% of cases, placental insufficiency took the leading place in the structure of the causes of hypoxia, including chronic in 74% of cases (extragenital diseases or pregnancy complications accompanied by fetal growth retardation, fetal growth retardation with fetodysplasia), in 19.9% of cases are acute (premature detachment of a normally located placenta, bleeding with placenta previa, uterine rupture).

The pathology of the umbilical cord could also be the cause of hypoxia (6.1%). The majority of patients (88%) with chronic placental insufficiency were observed in the antenatal clinic, in 87. 6% of pregnant women, premature detachment of a normally located placenta was diagnosed at the prehospital stage. In 3.9% of cases, the causes of intrauterine hypoxia, which led to antenatal fetal death, were not established. All fetuses in this group underwent post-mortem examination, which revealed only indirect causes of MR. In this regard, the term “sudden fetal death syndrome” was introduced into scientific circulation by analogy with the syndrome of sudden infant death [13]. nine0006

6% of pregnant women, premature detachment of a normally located placenta was diagnosed at the prehospital stage. In 3.9% of cases, the causes of intrauterine hypoxia, which led to antenatal fetal death, were not established. All fetuses in this group underwent post-mortem examination, which revealed only indirect causes of MR. In this regard, the term “sudden fetal death syndrome” was introduced into scientific circulation by analogy with the syndrome of sudden infant death [13]. nine0006

According to the data on MR, in the Russian Federation for 2010-2012. intrauterine hypoxia was recorded in 73-74% of cases, intranatal hypoxia - in 7-10% of cases. At the same time, in 38–40%, the cause of intrauterine hypoxia was the pathology of the placenta and umbilical cord, including in 13–14% it was placental abruption [14]. Similar trends are also typical for 2012–2014. [15].

Despite the fact that the percentage of unexplained MR in the Russian Federation is more than 2 times lower compared to foreign indicators, a high percentage of causes associated with hypoxia and placental insufficiency deprives these data of specificity. Thus, the authors of the CODAC system rightly note that no MR classification system by itself compensates for the lack of data and selection errors (the most easily observed conditions, which in fact may not be associated with MR at all, can be indicated as reasons) [6]. nine0006

Thus, the authors of the CODAC system rightly note that no MR classification system by itself compensates for the lack of data and selection errors (the most easily observed conditions, which in fact may not be associated with MR at all, can be indicated as reasons) [6]. nine0006

Apparently, this is precisely why the CODAC system, although there is continuity with the ICD, does not contain intrauterine hypoxia (code P20 according to ICD-10) and placental insufficiency (code P02.2 according to ICD-10) in any rubric. According to CODAC rules, they should be attributed to mechanisms, not causes of death.

This discrepancy can also be explained by the relatively rare conduct of a comprehensive analysis, covering, in addition to the results of a pathoanatomical study, all stages of the development of the initial clinical conditions that led to MR [16]. It draws attention to the fact that, according to foreign clinical data, unexplained antenatal losses account for 42%, according to the results of autopsies - 17-50% of cases of antenatal death. However, up to 2 / 3 clinically unclear losses are explained during autopsy and examination of the placenta.

However, up to 2 / 3 clinically unclear losses are explained during autopsy and examination of the placenta.

In a study by U.N. Tumanova and A.I. Shchegolev [17] discusses the ambiguity of the term "placental insufficiency" and the vagueness of the criteria for placental infarction, in connection with which the authors ask the question: is placental pathology the cause of fetal death or only contributes to its development. A full-fledged morphological study of all components of the placenta (placental disc, umbilical cord, membranes), including macroscopic, histological, immunohistochemical, molecular genetic tests, is recognized as desirable [17]. An example of this approach is another study in which, depending on the degree of maturity of the villous tree of the placenta, two phenotypes of antenatal fetal losses are distinguished, which differ in pathogenesis and thanatogenesis and have a peculiar combination of placental, fetal, and maternal factors. The author of this study also acknowledges that fetal hypoxia is not necessarily the cause of fetal death, it may be a natural consequence of another (main) cause of antenatal death, for example, maternal pathology (preeclampsia, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, autoimmune conditions, etc.) [eighteen]. nine0006

The author of this study also acknowledges that fetal hypoxia is not necessarily the cause of fetal death, it may be a natural consequence of another (main) cause of antenatal death, for example, maternal pathology (preeclampsia, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, autoimmune conditions, etc.) [eighteen]. nine0006

Many domestic and foreign researchers note that the phenomenon of fetal death is caused by many factors and it is impossible to single out one of them that would unequivocally lead to MR [5, 6, 16, 19—22]. Of course, this is in conflict with the main characteristics of an effective FP classification system, indicated in the table above, namely the need to record the single most important factor that led to death, and at the same time the possibility of fixing concomitant factors that are clearly distinguishable from the cause of death. nine0006

An analysis of 150 puerperas (including 38 with MR) made it possible to identify the most significant clinical, anamnestic and laboratory risk factors for reproductive losses (not associated with chromosomal abnormalities). Among them, the age is over 35; the presence of miscarriages in history; the presence of conditionally pathogenic Ureaplasma urealyticum in high titer; the absence of protective IgG to the rubella virus during pregnancy; an elevated level of glucose in the venous plasma, indicating a violation of carbohydrate metabolism [22]. nine0006

Among them, the age is over 35; the presence of miscarriages in history; the presence of conditionally pathogenic Ureaplasma urealyticum in high titer; the absence of protective IgG to the rubella virus during pregnancy; an elevated level of glucose in the venous plasma, indicating a violation of carbohydrate metabolism [22]. nine0006

Further search for specific markers (factors of prognostic significance), evaluation of their independent significance and correlations with other indicators are needed in order to further clarify the impact on the perinatal outcome of the mother's condition and other conditions during pregnancy and childbirth [20, 21]. The identification of predictors should be carried out not only in groups of pregnant women with risk factors, but in the entire population [16, 21].

According to Norwegian researchers, when studying risk factors and causes of MR according to CODAC, it was found that about 68% of all MR were caused by placental pathology (almost 50%) or associated with it (18%), the cause of MR remained unknown in 19. 4% of cases. Smoking (OR=3.4; [95% CI 2.3-5.0]) and prematurity (OR=29.8; [95% CI 16.6-53.3]) were the main risk factors regardless of the cause of MR. ) [23].

4% of cases. Smoking (OR=3.4; [95% CI 2.3-5.0]) and prematurity (OR=29.8; [95% CI 16.6-53.3]) were the main risk factors regardless of the cause of MR. ) [23].

Multiple pregnancies, arterial hypertension, and diabetes mellitus were found to be the most significant risk factors in puerperas with placental or unknown cause of MR. Among women with placental causes of MR, prothrombin gene polymorphism F2 (rs179963) and combined thrombophilia were also significant factors. In the subgroup of puerperas with non-placental causes of MR, the antiphospholipid syndrome was a significant risk factor (10–14% of cases of miscarriage, compared with 20–24% in domestic cases) [24]. nine0006

Analysis of almost 380 thousand births, incl. more than 2.1 thousand cases of MR for the period 2013-2014 in Japan showed that the causes of MR remained unexplained in 25-40% of cases (depending on the term of delivery). Most of the remaining cases were due to placental disorders. The risk of MR was increased in preterm birth - adjusted relative risk ( ARR) = 3. 78; [95% CI 3.31-4.32]), as well as at the first birth - ARR = 1.19; [95% CI 1.05–1.35]. The body weight of the puerperal is below normal, gestational hypertension and oligohydramnios were also contributing factors [11]. nine0006

78; [95% CI 3.31-4.32]), as well as at the first birth - ARR = 1.19; [95% CI 1.05–1.35]. The body weight of the puerperal is below normal, gestational hypertension and oligohydramnios were also contributing factors [11]. nine0006

A large US study published in 2017 aimed to create a clinical MR predictive tool that combines all relevant objective maternal risk factors to identify women who need additional antenatal examinations and increased medical supervision . The obtained mathematical model, created on the basis of the analysis of more than 64 thousand cases of singleton pregnancies in the II trimester according to 1999-2009, was called the "MP calculator". Maternal age, skin color (race), first birth, body mass index (BMI), smoking, chronic hypertension, and pregestational diabetes were identified as predictor parameters. The model showed modest differences compared to simple risk factor assessment (66% sample coverage with 95% CI 0.60-0.72 and 64% sample coverage with 95% CI 0. 58-0.70, respectively, at p = 0, 25). At the same time, this MR calculator demonstrated clinically significant efficiency and ease of use [25]. nine0006

58-0.70, respectively, at p = 0, 25). At the same time, this MR calculator demonstrated clinically significant efficiency and ease of use [25]. nine0006

In the British model of the MR calculator, built on the basis of an analysis of more than 110 thousand cases of singleton pregnancies in the first and second trimesters, according to the data of 2006-2015, in addition to the factors taken into account in the American model, the presence of preterm births and miscarriages was also taken into account in history. Some more rare factors were also taken into account (artificial conception, autoimmune conditions - systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome). The model predicted 31% of MRs associated with placental disorders and 26% of unexplained MRs ( р =0.1) [10].

Unfortunately, all these models in their original form cannot be used in Russia. The North American, West European, East Asian and East European populations differ significantly, for example, the race factor for central Russia loses its significance. The conditions and quality of medical care in different countries differ. It is difficult to identify bad habits in domestic practice, especially in the early stages of pregnancy, for example, up to 25% of smoking pregnant women hide this habit, fearing a doctor's condemnation [26]. At the same time, it has been repeatedly and reliably proven that in the Russian Federation, as in other countries, active and passive smoking are significant risk factors for the development of complications during pregnancy and childbirth [27]. nine0006

The conditions and quality of medical care in different countries differ. It is difficult to identify bad habits in domestic practice, especially in the early stages of pregnancy, for example, up to 25% of smoking pregnant women hide this habit, fearing a doctor's condemnation [26]. At the same time, it has been repeatedly and reliably proven that in the Russian Federation, as in other countries, active and passive smoking are significant risk factors for the development of complications during pregnancy and childbirth [27]. nine0006

The main drawback of the considered calculators is the lack of transparent criteria for selecting significant risk factors that can be applied to another group or population in order to correct the model. For example, in the Russian Federation, intrauterine [28] and maternal infections are quite common among pregnant women (herpes infection in 7–19% [29], human papillomavirus infection in 2–34% [30], HIV [31], chlamydial infection in 2–11% [32]). The MR calculators mentioned do not take into account all of these factors. nine0006

nine0006

A simple decrease in the number of indicators (exclusion of individual factors), given the sample coverage in the original models at a level significantly less than 70%, will lead to a significant decrease in the reliability of the forecast.

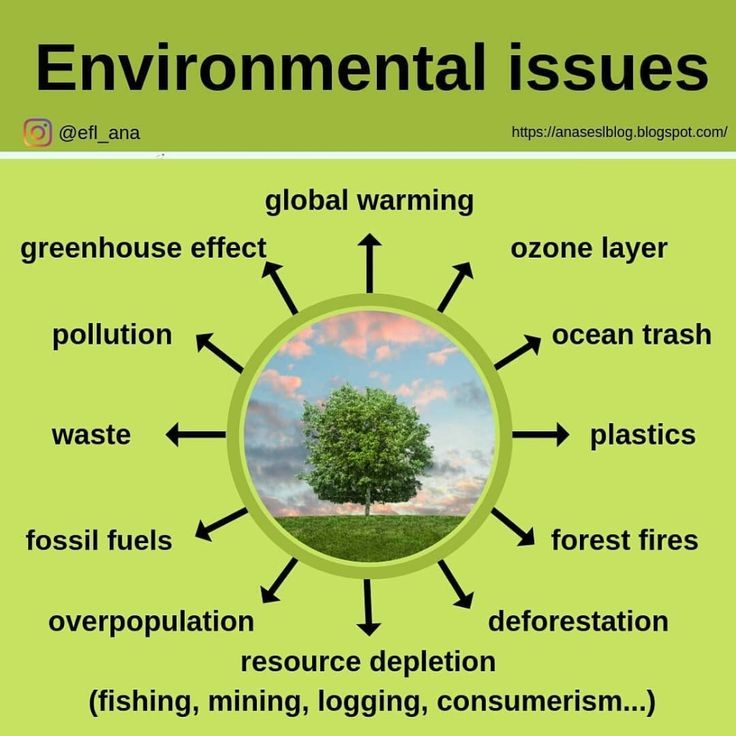

The performed analysis allows us to draw the following conclusion:

— development and application of various MR classifications are naturally associated with the introduction of systems for predicting this outcome of pregnancy and childbirth;

- continued work is needed to combine maternal factors with various biomarkers in order to create effective screening procedures to prevent MR, including antenatal fetal death; nine0006

— due to the multifactorial nature of the MR phenomenon and the predominance of specific risk factors in different countries and regions, further in-depth analysis of regional features of observations of the course of pregnancy and childbirth ending with MR remains relevant.

Author contributions:

Research concept and design — V. G. Volkov;

G. Volkov;

Collection and processing of material - M.V. Castor;

Statistical processing - M.V. Castor; nine0006

Writing the text - V.G. Volkov, M.V. Castor; editing - V.G. Volkov.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Stillbirths in the constituent entities of the Russian Federation in 2010

To improve the organization and quality of perinatal care, it is necessary to have a clear understanding of the number and causes of perinatal losses, the level and structure of which need to be systematically analyzed, since they reflect the quality of obstetric and neonatal care. nine0006

Stillbirth is an important component of perinatal mortality, therefore, an analysis of its level and causes is of great importance both for reducing the stillbirth rate itself and for perinatal mortality in general.

This report is based on the analysis of Rosstat data for 2000-2010, when, in accordance with the recommendations of the World Health Organization, stillborns with a gestational age of 28 weeks or more, weighing 1000 g or more, were subject to registration. nine0006

nine0006

Describing the dynamics of stillbirths in the Russian Federation for 2000-2010, one should note the annual fluctuations in the absolute number of stillbirths, although this did not affect the stillbirth rates (the number of stillbirths after 28 weeks of gestation per 1000 live and dead births). The maximum number (9043) of stillbirths was registered in 2003, the minimum (7934) in 2006. In total, 194,605 stillbirths were registered during the entire post-Soviet period (1991–2010) [1]. nine0006

The average values of the stillbirth rate in the Russian Federation tend to steadily decrease (Table 1). Thus, from 2000 to 2010 it decreased by 32.1%, and from 2006 to 2010 — by 13.3%.

The highest stillbirth rates are currently observed in Nigeria and Pakistan (42 and 47 stillbirths per 1000 births), and the lowest rates are in Finland and Singapore (2 stillbirths per 1000 births) [2].

Stillbirth rates in the Russian Federation vary across federal districts. The lowest (4.29‰) stillbirths are observed in the North Caucasian Federal District (see figure). Figure 1. Stillbirth rates in the federal districts of the Russian Federation in 2010 . The highest level (5.32‰), exceeding the national average by 15.2%, was registered in the Far Eastern Federal District.

The lowest (4.29‰) stillbirths are observed in the North Caucasian Federal District (see figure). Figure 1. Stillbirth rates in the federal districts of the Russian Federation in 2010 . The highest level (5.32‰), exceeding the national average by 15.2%, was registered in the Far Eastern Federal District.

Analyzing stillbirth rates in the constituent entities of the Russian Federation, one should note their significant differences. The average stillbirth rate among 83 subjects in 2010 was 4.62‰, while there is an asymmetric distribution of the trait. nine0006

The minimum level of stillbirths (2.28‰) was observed in the Republic of Adygea, and the maximum (6.82‰) in the Republic of Altai. In this regard, to analyze the regional features of the stillbirth rate, it is advisable to divide the existing range of values into three parts, including 33% of the range of differences [3]:

- 2.28-3.79‰ - low level;

- 3.80-5.31‰ - average level;

- 5. 32-6.82‰ - high level.

32-6.82‰ - high level.

Distribution of subjects by stillbirth rate is presented in tab. 2. Almost all federal districts, with the exception of the Far East, are characterized by the predominance of subjects with an average stillbirth rate. Although in the Central Federal District there are 8 subjects (out of 18) with a high level and only one (Belgorod region - 3.77‰) - with a low level of stillbirth. In the Northwestern Federal District (11 subjects), 4 subjects have a high level, 7 have an average level, and there are no regions with a low rate. Among the 14 subjects of the Volga District, only one (Penza region - 3.53‰) has a low stillbirth rate. Far Eastern District (9subjects) has 7 regions with a high and one with a low (Kamchatsky Krai - 2.83‰) and an average (Chukotka Autonomous Okrug) stillbirth rate. In general, in the Russian Federation, there are 10 (12%) regions with a low, 42 (50.6%) - with an average, and 31 (37.4%) - with a high level of stillbirth.

The stillbirth rate consists of two components: antenatal stillbirth (death occurred before the onset of labor) and intrapartum (death occurred during childbirth; Table 3). According to O.G. Frolova et al., [4] analysis of the ratios of antenatal and intranatal stillbirths allows us to assess the quality and completeness of medical care for a pregnant woman and a newborn at its different stages. nine0006

According to O.G. Frolova et al., [4] analysis of the ratios of antenatal and intranatal stillbirths allows us to assess the quality and completeness of medical care for a pregnant woman and a newborn at its different stages. nine0006

Antenatal and intrapartum stillbirths contribute differently to the overall stillbirth rate (see Table 3) . The proportion of antenatal losses is 4.2–5.5 times higher than the rates of intranatal death. A characteristic feature is also a steady decrease (by 20.1% from 2005 to 2010) in the proportion of intranatal dead fetuses among all stillbirths, which is associated with the widespread introduction of modern obstetric technologies and operative delivery in the interests of the fetus. A decrease in the proportion of intrapartum stillbirth is naturally accompanied by an increase in its antenatal component. nine0006

In this regard, data on stillbirths should be analyzed separately for antenatal clinics and maternity hospitals. Accounting for this information can increase the responsibility of maternity hospital staff for adverse perinatal outcomes, as well as allow the management of the service to most objectively assess the level of perinatal care and promptly eliminate its defects [5].

Thus, according to statistical reports, in many regions of the country, most cases of antenatal fetal death occur in a maternity hospital, which indicates an extremely unfavorable situation with prenatal care in the departments of pathology of pregnant obstetric institutions [6]. nine0006

The main contingent of women with antenatal mortality are socially disadvantaged pregnant women [7]. Given this, the increase in the proportion of prenatal death of the fetus in the structure of stillbirth and perinatal mortality may be an indicator of the social disadvantage of the population. Moreover, intrauterine fetal death is a significant risk factor for coagulopathic bleeding during labor and the postpartum period, as well as one of the causes of maternal death. The frequency of pathological obstetric blood loss in "dead fetus syndrome" reaches 21.0% [8]. nine0006

The average values of the antenatal stillbirth rate in the Russian Federation in 2010 amounted to 4.05‰. Its minimum level (0. 87‰) is observed in the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic, and the maximum (7.14‰) in the Chechen Republic. Based on these values, the low level of antenatal stillbirth corresponds to the range of 0.87–2.96‰, the average level corresponds to 2.97–5.05‰, and the high level corresponds to 5.06–7.14‰.

87‰) is observed in the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic, and the maximum (7.14‰) in the Chechen Republic. Based on these values, the low level of antenatal stillbirth corresponds to the range of 0.87–2.96‰, the average level corresponds to 2.97–5.05‰, and the high level corresponds to 5.06–7.14‰.

In general, in the Russian Federation there are 8 regions with a low, 67 with an average and 8 with a high level of antenatal mortality (Table 4). In the Central Federal District, 15 subjects have average indicators, one (Bryansk region) - low (2.83‰) and two (Kostroma and Smolensk regions) - high (5.88‰ and 5.3‰, respectively). In the Northwestern Federal District, 10 subjects have average rates and one (Vologda Oblast) has a high rate (5.46‰). In the Siberian and Far Eastern districts, there is one region each with low rates (Tomsk Oblast - 2.41‰ and Kamchatka Krai - 2.31‰, respectively) and one each with high rates (Republic of Altai - 5.41‰ and Sakhalin Oblast - 5, 29‰ respectively). All 6 regions of the Urals District have an average level of antenatal mortality.

All 6 regions of the Urals District have an average level of antenatal mortality.

The average level of intrapartum stillbirth in Russia in 2010 reached 0.71‰. The maximum value (2.2‰) was noted in the Magadan region. In a number of regions, in particular the Nenets and Chukotka Autonomous Okrugs, cases of intrapartum fetal death have not been registered. In this regard, the low level of intrapartum mortality corresponds to the range of 0-0.73‰, the average - 0.74-1.46‰, high - 1.47-2.2‰. nine0006

Based on these values, in 2010 in the Russian Federation there were 36 regions with a low, 39 with an average, and 8 with a high level of intrapartum mortality (Table 5). High rates of intrapartum mortality were noted in the Magadan, Kaluga, Ryazan and Nizhny Novgorod regions, the Jewish Autonomous Region, the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic, the Republics of Mordovia and Khakassia.

In this regard, one can point to the data of I.A. Kamaeva et al., [9] according to which about 2 / 3 (57. 6%) intranatal losses in the Nizhny Novgorod Region in 1995-2005. can be classified as preventable, and in half (51%) of observations there was a low quality of dispensary observation of pregnant women, i.e. to reduce perinatal mortality, it is necessary to improve assistance to pregnant women at the stage of contacting the antenatal clinic.

6%) intranatal losses in the Nizhny Novgorod Region in 1995-2005. can be classified as preventable, and in half (51%) of observations there was a low quality of dispensary observation of pregnant women, i.e. to reduce perinatal mortality, it is necessary to improve assistance to pregnant women at the stage of contacting the antenatal clinic.

An important factor in assessing the activities of health authorities and institutions is the characterization of the causes of death. According to the regulatory documents in force in 2010, in all cases of stillbirth at a gestational age of at least 28 weeks, medical certificates of perinatal death were drawn up (form No. 106-2 / y-98), on the basis of which the statistical form A-05 of Rosstat was formed. This form is a cross-table, in which the pathology of the fetus or newborn (the original cause of death) is presented horizontally, and the extragenital pathology of the mother, complications from the placenta, umbilical cord and membranes, complications of childbirth and delivery, which caused (contributed to) the onset of death, vertically fetus or newborn. Reduced, and also without division into antenatal and intranatal mortality, the statistical form A-05 of Rosstat is presented in tab. 6.

Reduced, and also without division into antenatal and intranatal mortality, the statistical form A-05 of Rosstat is presented in tab. 6.

The most common cause of stillbirth, according to Rosstat, is "Intrauterine hypoxia" (R20 ICD-10) and "Asphyxia during childbirth" (R21 ICD-10) - 391.9 per 100,000 live births and stillbirths (see Table. 6) , which is 84.9% of all cases of stillbirth. Antenatal hypoxia was recorded 7.2 times more often than intrapartum. The second place is occupied by "Congenital anomalies (malformations), deformities and chromosomal disorders" (Q00-Q99 ICD-10) - 21.6 per 100,000 births (4.7%). At the same time, congenital heart defects account for 15.7% of the total number of developmental anomalies. In third place (2%) - "Endocrine and metabolic disorders". "Infectious diseases" (P35-P39ICD-10), including congenital sepsis, account for 1.9% of the causes of stillbirth.

On the part of the mother, placenta pathology is the most common cause - 209 per 100,000 live births and stillbirths, which is 45. 3% of all observations.

3% of all observations.

15.2% involve maternal conditions unrelated to pregnancy, and 24.8% of stillbirths (114.7 per 100,000 live births and stillbirths) have no maternal cause. In our opinion, in this case we are most likely talking about the absence of an entry in paragraph 23 in the “Medical certificate of perinatal death”. 20 years ago A.G. Talalaev and G.A. Samsygin [10] noted that in 1 / 3 cases of perinatal mortality is due to insufficient level of obstetric care for practically healthy women, since in 1 / 3 women with perinatal death, neither initial diseases nor pathology were detected during pregnancy.

Therefore, a thorough and detailed analysis of the causes of stillbirth is necessary, and primarily on the basis of data from pathoanatomical studies of autopsy material.

Nevertheless, the analysis of regional features of stillbirth indicates that in a number of subjects of the Russian Federation, significant progress has been made in reducing stillbirth rates from "controlled" causes, which can be prevented with correct and timely prenatal diagnosis, sufficient qualifications of specialists and material equipment of institutions healthcare.