What does a pelvis do

Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - pelvis

Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - pelvis | Pregnancy Birth and Baby beginning of content3-minute read

Listen

While everyone has a pelvis, the female pelvis differs from the male’s. Learn the anatomy of the female pelvis and how it undergoes unique changes to support pregnancy and childbirth.

What is the pelvis?

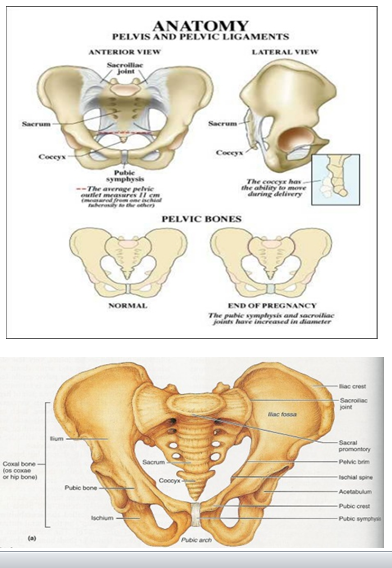

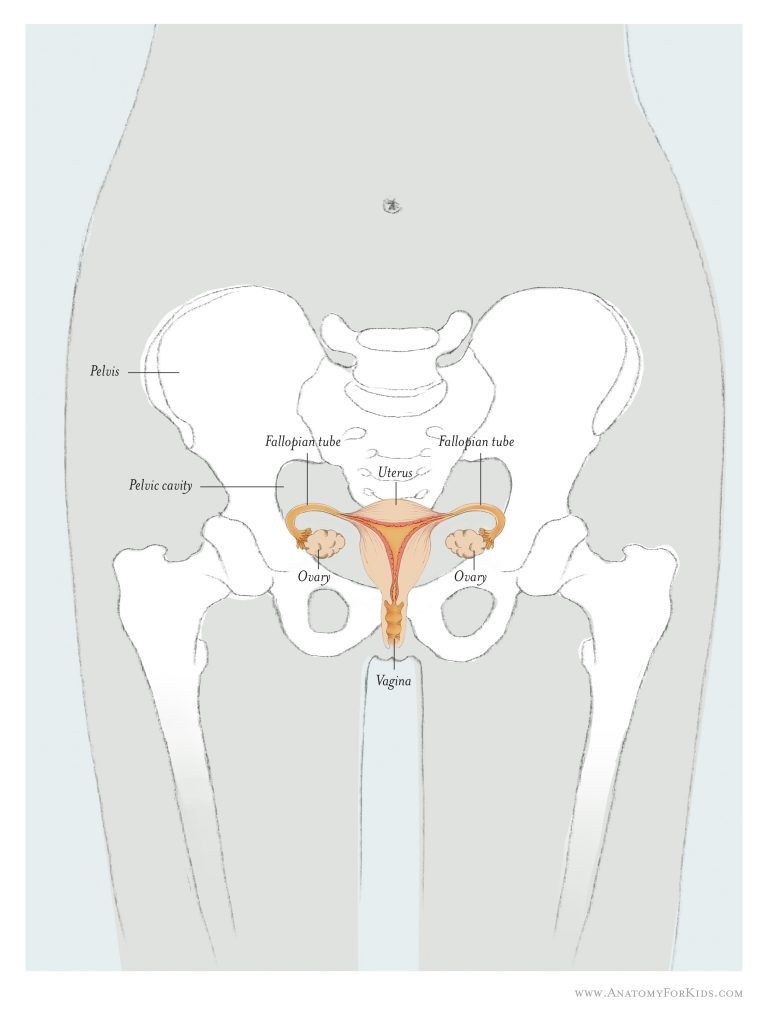

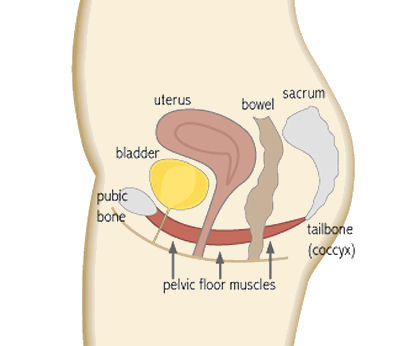

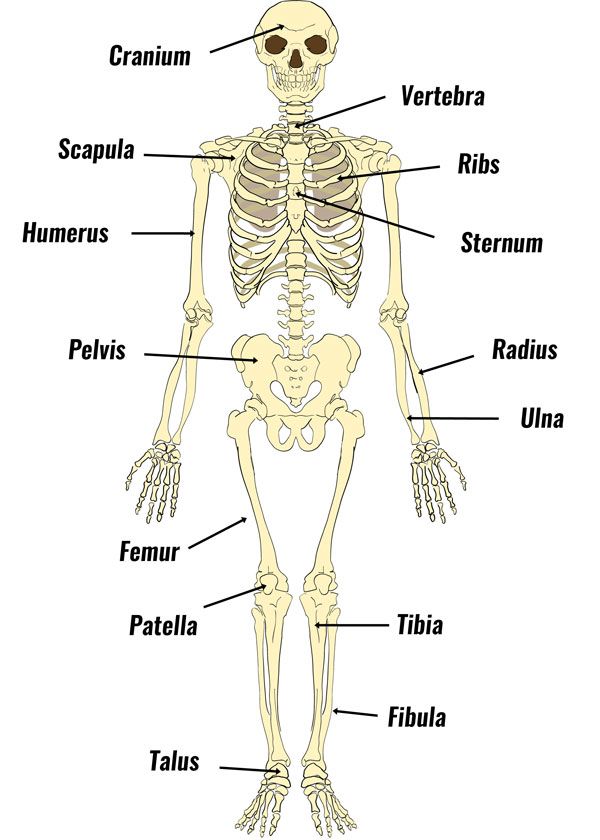

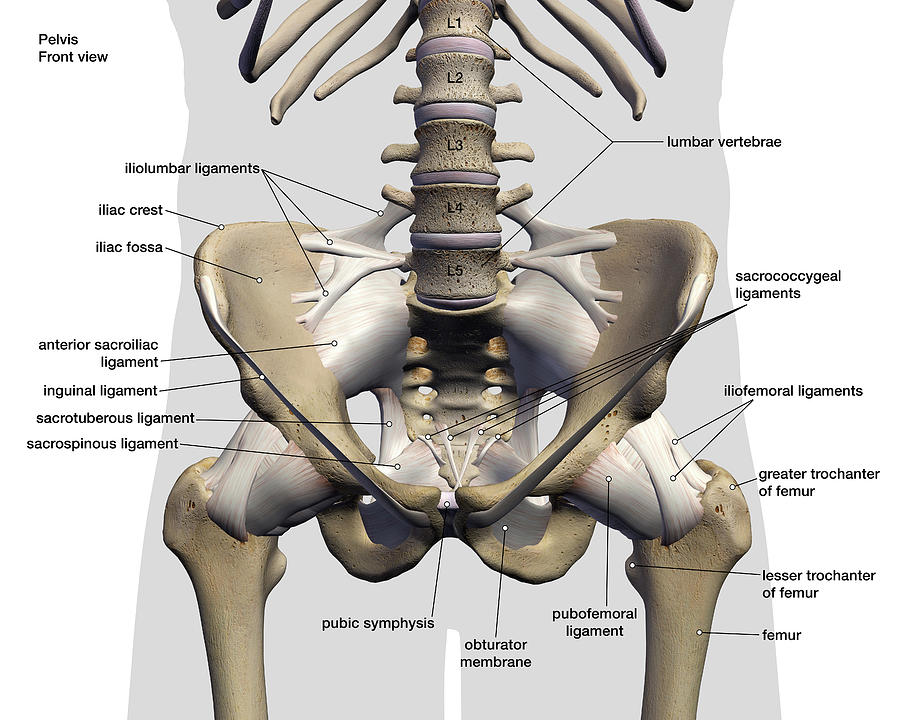

The pelvis is located in the middle of the human body, below the abdomen and above the thighs. It comprises the bony pelvis — which includes the hip bones —, pelvic cavity, pelvic floor, and perineum — the area of skin between the opening of the vagina and the anus. The bones around the pelvis are attached by several ligaments, comprised of tough and flexible tissue, and four joints. These help the pelvis to function.

What does the pelvis do?

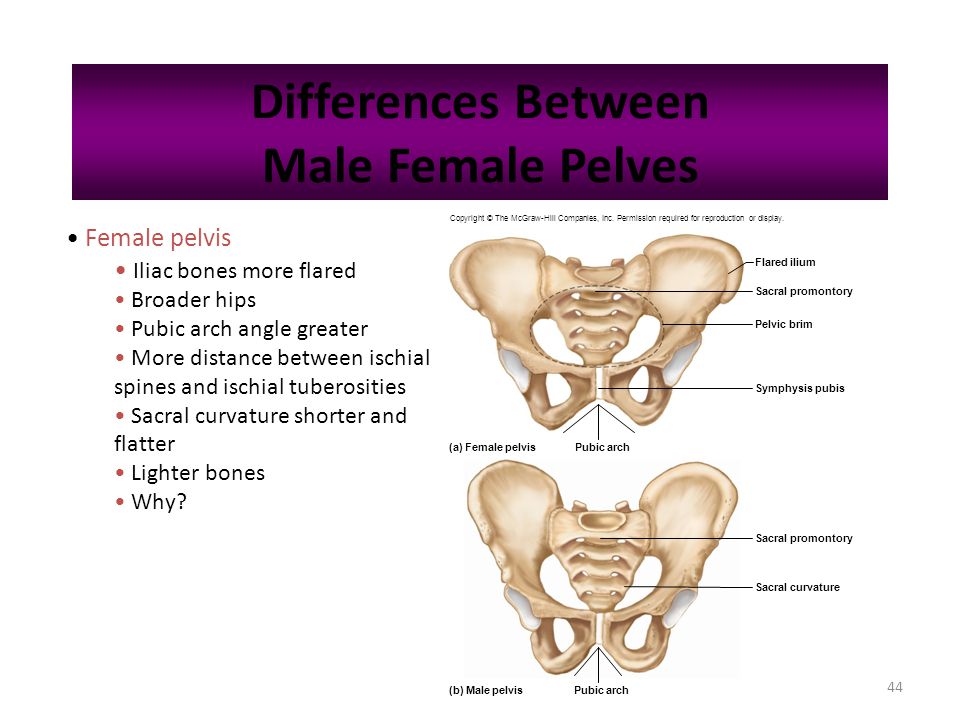

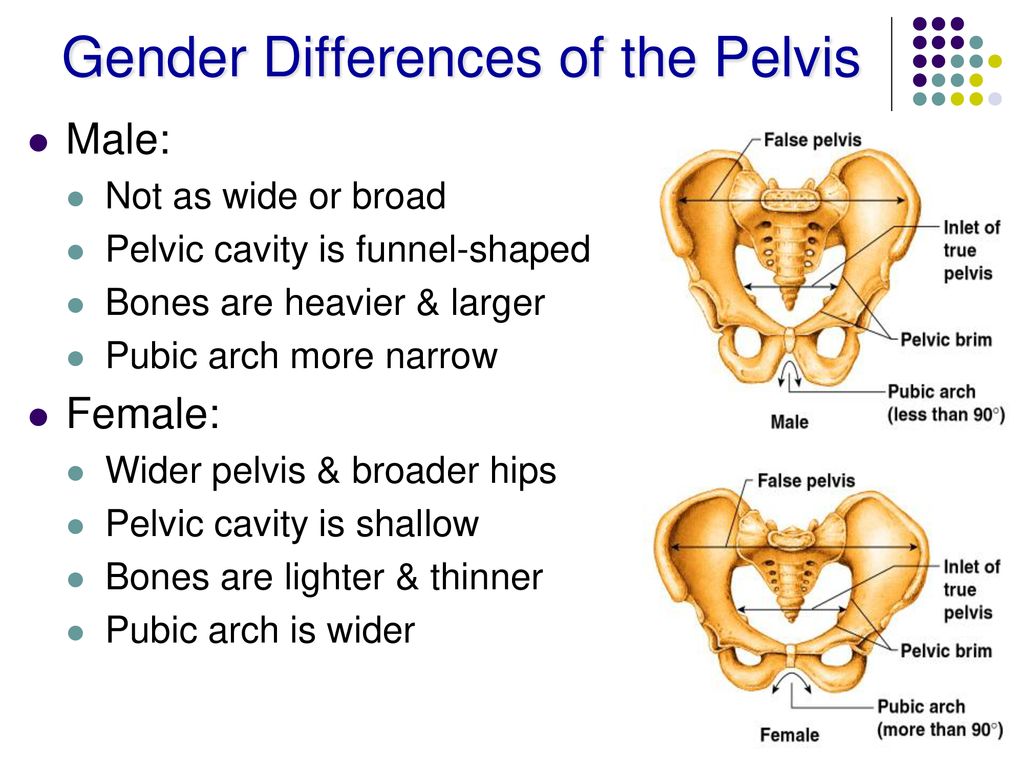

The pelvis has many roles, including holding the body upright so you can stand, walk and run. Additionally, a woman’s pelvis, which is wider, more rounded and has thinner bones than a male’s, helps women through pregnancy and childbirth.

How does the pelvis change during pregnancy?

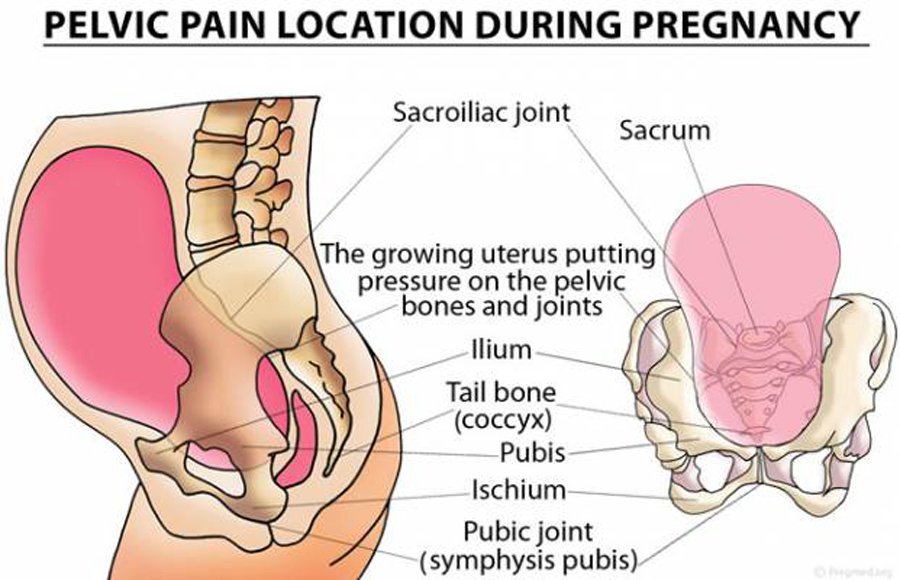

A pregnant woman’s pelvis changes through pregnancy. Its shape, position, and joint and ligament behaviour adjust to support the baby during pregnancy, making childbirth easier for both mother and baby. For example, a hormone named relaxin helps the pelvis relax during pregnancy and birth to accommodate the growing baby and to allow for an easier delivery.

Pelvic pain — a common condition in pregnancy

While changes to a pregnant woman’s pelvis help facilitate pregnancy and birth, they can cause discomfort. For instance, when the joints of the pelvis relax, a pregnant mother can feel less stable on her feet, and she may feel discomfort in her pelvis and lower back pain.

The following approaches have been shown to reduce pregnancy-related pelvic pain:

- applying heat packs to painful areas

- wearing low-heeled shoes

- avoid standing on one leg (sit down to get dressed, climb stairs one at a time)

- seeing a physiotherapist for exercise and posture advice

- avoiding standing or walking for long periods of time

- being careful about movements that stretch the hip, such as getting in and out of cars, sitting on low stools and squatting

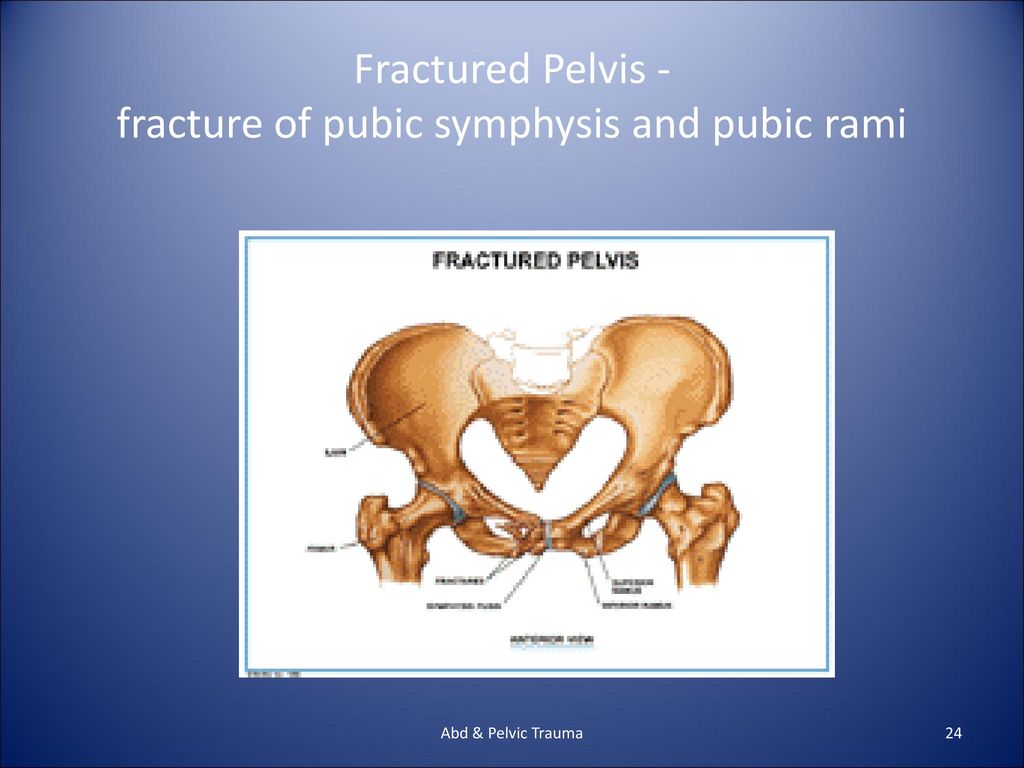

Although very rare, other injuries to the pelvis can occur during pregnancy and childbirth, including fractures. A pelvic injury such as a fracture requires prompt medical attention.

The pelvis and childbirth

For birth, a baby should ideally be positioned with their head down and facing the mother’s back. This position helps the baby descend through the pelvis and birth canal.

A baby who lies bottom or feet down in the pelvis during late pregnancy is said to be in breech position. Breech presentations increase the chance of a complicated vaginal birth and can lead to a caesarean section. While most babies naturally turn in the womb in time for labour, techniques performed by an obstetrician, such as an external cephalic version (ECV), can help the baby to turn.

Breech presentations increase the chance of a complicated vaginal birth and can lead to a caesarean section. While most babies naturally turn in the womb in time for labour, techniques performed by an obstetrician, such as an external cephalic version (ECV), can help the baby to turn.

Most babies naturally get into the 'head down' position in time for labour and birth. Certain positions for birth can help guide the baby down through the pelvis. For example, staying upright during contractions means that gravity is working to help the baby transition through the pelvis, and along the birth canal.

There are other ways to take advantage of the structure and function of the pelvis to assist in childbirth. Read more about positions for labour and birth.

Sources:

StatPearls Publishing (Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis), Department of Health (Pregnancy Care Guidelines), Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (Breech Presentation at the End of your Pregnancy), King Edward Memorial Hospital (Pregnancy, birth and your baby), Journal of Orthopedics, Traumatology and Rehabilitation (2014) (Pelvic trauma in women of reproductive age), European Spine Journal (Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain and its relationship with relaxin levels during pregnancy)Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Last reviewed: October 2020

Back To Top

Related pages

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - abdominal muscles

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - cervix

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - perineum and pelvic floor

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - uterus

Need further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Video call

- Contact us

- About us

- A-Z topics

- Symptom Checker

- Service Finder

- Subscribe to newsletters

- Sign in

- Linking to us

- Information partners

- Terms of use

- Privacy

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is funded by the Australian Government and operated by Healthdirect Australia.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby’s information and advice are developed and managed within a rigorous clinical governance framework.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Healthdirect Australia acknowledges the Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia and their continuing connection to land, sea and community. We pay our respects to the Traditional Owners and to Elders both past and present.

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Pelvic Bones - StatPearls

Matthew D. Burgess; Forshing Lui.

Burgess; Forshing Lui.

Author Information and Affiliations

Last Update: July 25, 2022.

Introduction

The bones of the pelvis are a critical part of the central portion of the skeleton. They serve as a transition from the axial skeleton and the appendicular skeleton of the lower body, serving as an attachment point for some of the strongest muscles in the human body while withstanding the forces generated by them. The curved nature of the pelvic bone creates a closed structure, itself lined with various muscles and housing various blood supplies, lymphatic structures, nerves, and organs, including the intestines, urinary bladder, and internal sex organs.

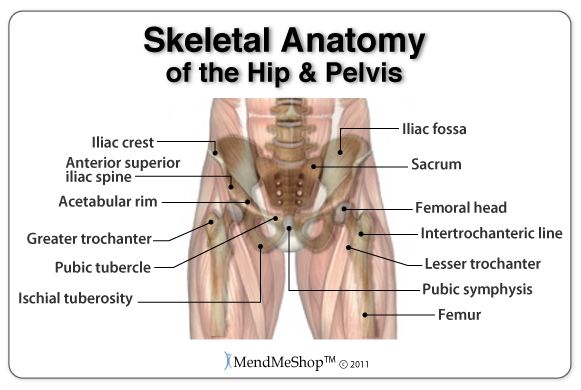

Structure and Function

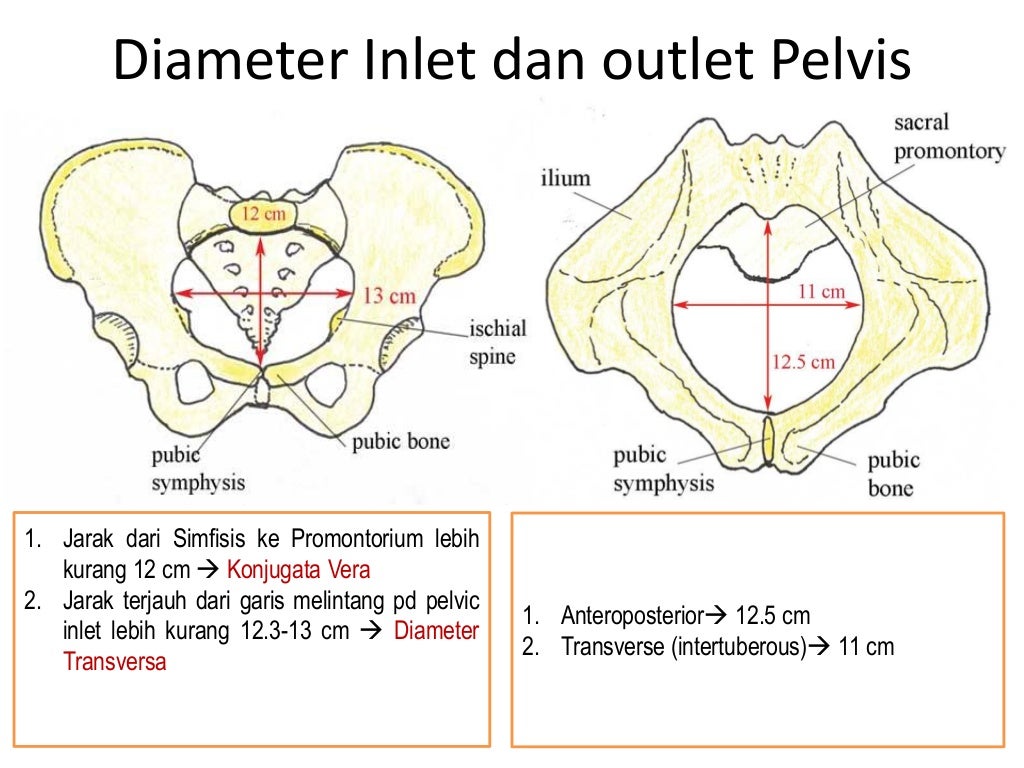

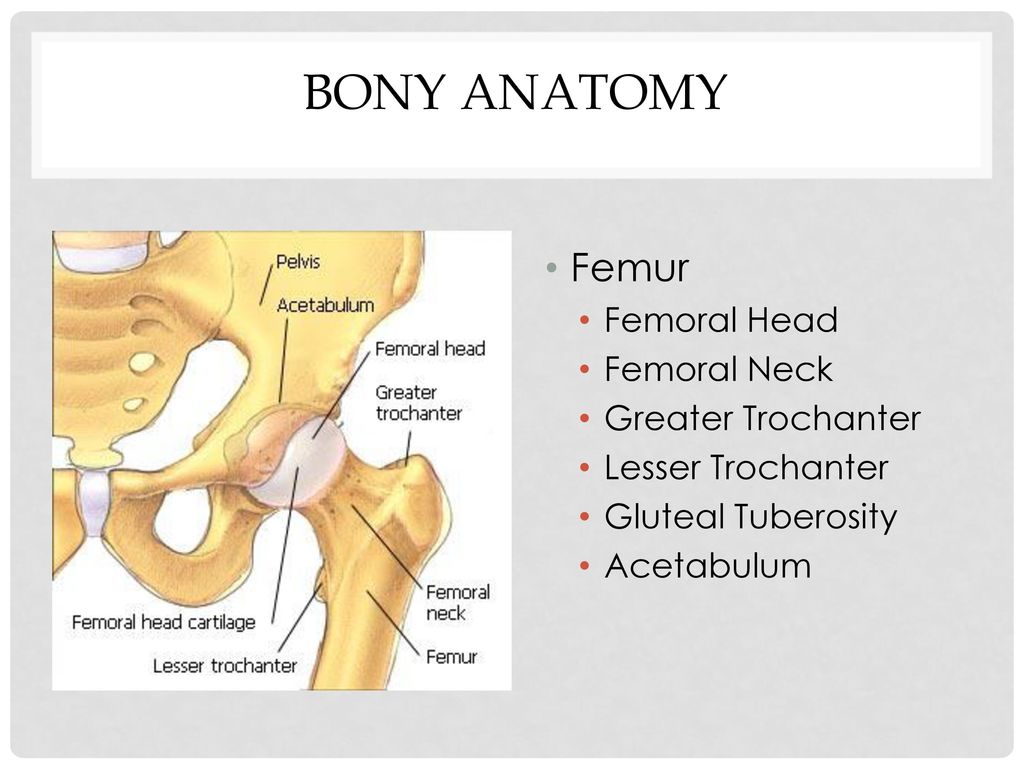

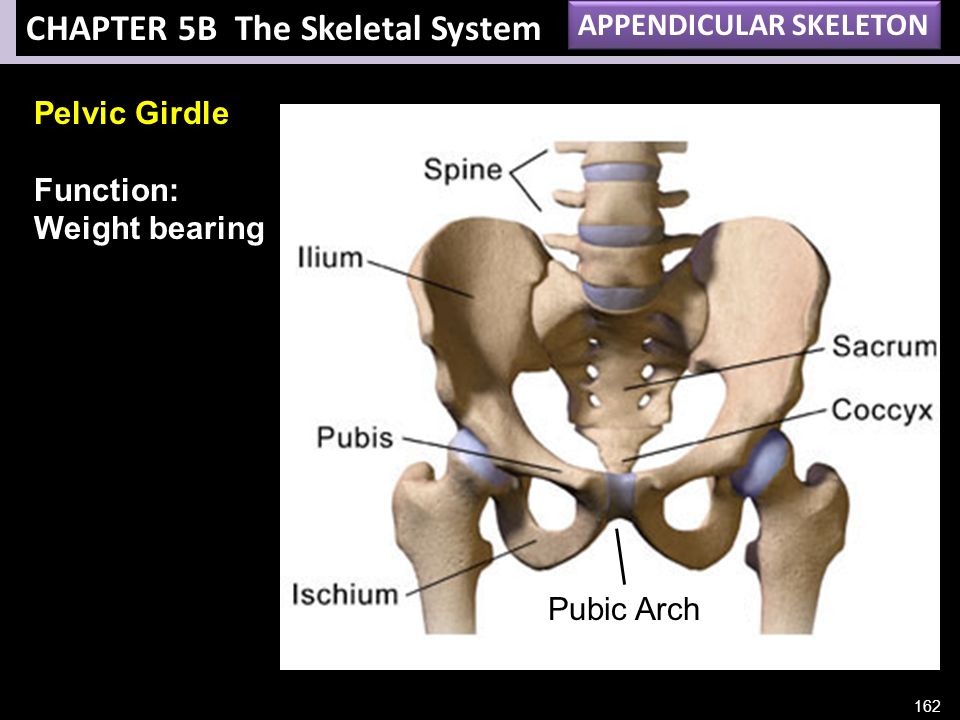

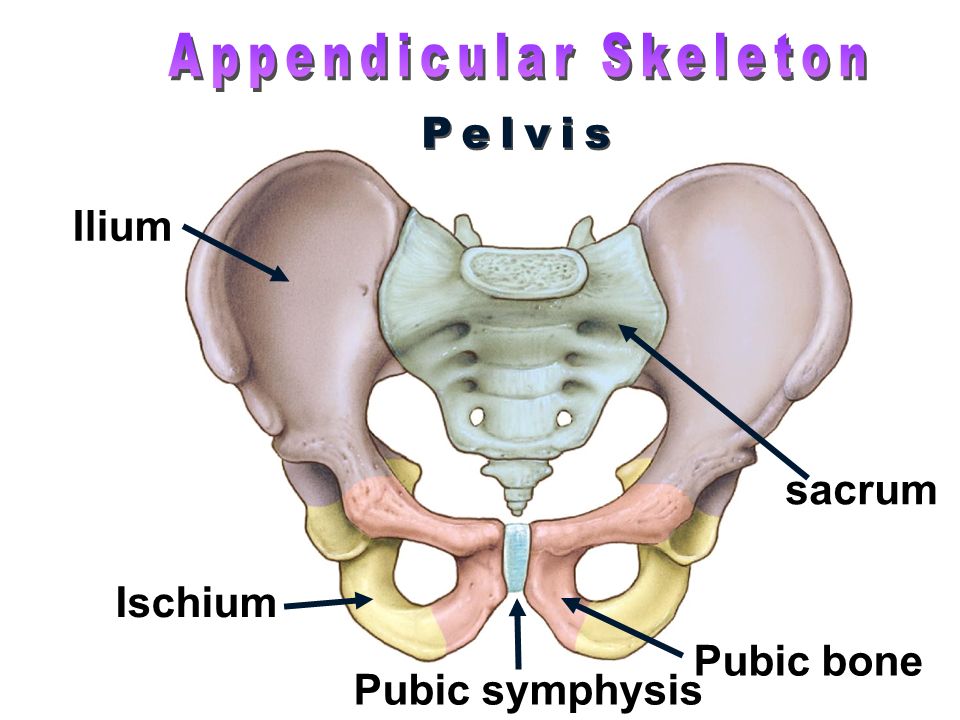

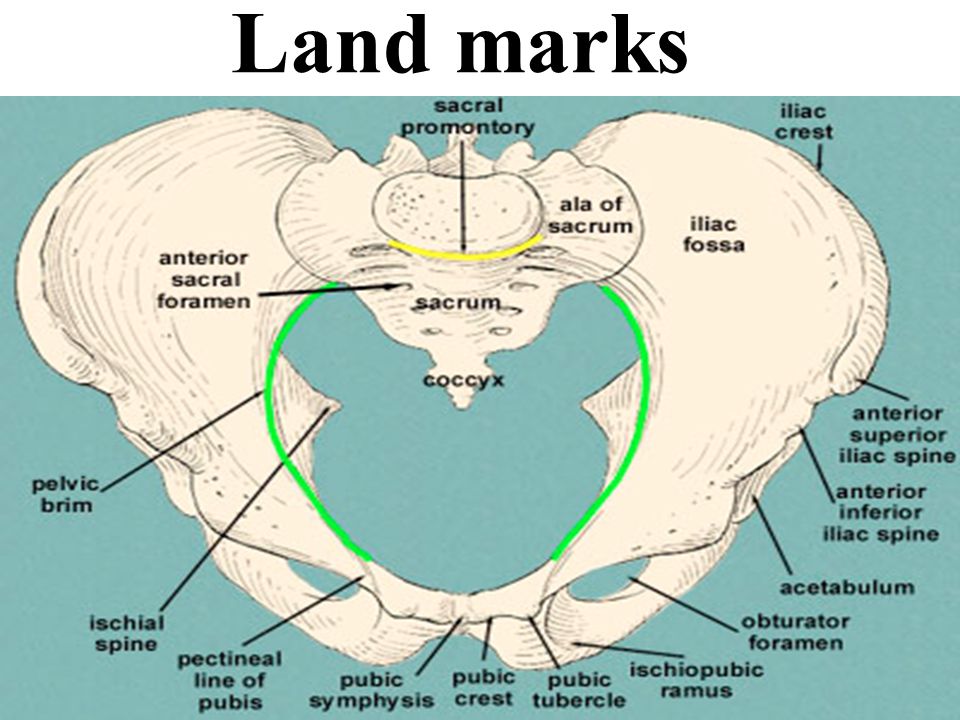

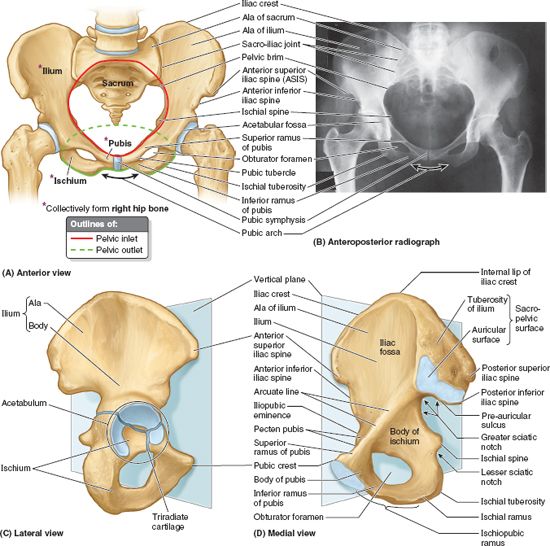

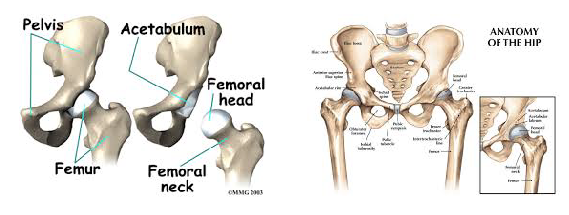

The pelvis is comprised of the large hip bone, the os coxae, on each side. The os coxae itself is composed of the ilium (the flat superior protuberance), ischium (the curved anterior protuberance), and pubis bones (the curved inferior protuberance). The os coxae attach anteriorly to each other at the pubic symphysis and posteriorly to each side of the sacrum, creating the sacroiliac joint. These three os coxae bones meet each other at the acetabulum, a medial structure that serves as an attachment point for the head of the femur. The pubis and ischium also articulate inferiorly at the ramal epiphyses, with their curving nature leaving an opening between them known as the obturator foramen. This foramen allows the obturator nerve to leave the pelvic cavity. Each of the pelvic bones also has many landmarks (i.e., tuberosities, notches) unique to the specific bone. The superior edge of the ilium is named the crest of the ilium, or, more commonly, the iliac crest, with a tuberosity below it on the ilium’s anterior edge known as the anterior inferior iliac spine. The ilium also has a posterior-inferior landmark known as the greater sciatic notch on it, with a subsequent lesser sciatic not being on the posterior-inferior side of the ischium.

The os coxae attach anteriorly to each other at the pubic symphysis and posteriorly to each side of the sacrum, creating the sacroiliac joint. These three os coxae bones meet each other at the acetabulum, a medial structure that serves as an attachment point for the head of the femur. The pubis and ischium also articulate inferiorly at the ramal epiphyses, with their curving nature leaving an opening between them known as the obturator foramen. This foramen allows the obturator nerve to leave the pelvic cavity. Each of the pelvic bones also has many landmarks (i.e., tuberosities, notches) unique to the specific bone. The superior edge of the ilium is named the crest of the ilium, or, more commonly, the iliac crest, with a tuberosity below it on the ilium’s anterior edge known as the anterior inferior iliac spine. The ilium also has a posterior-inferior landmark known as the greater sciatic notch on it, with a subsequent lesser sciatic not being on the posterior-inferior side of the ischium. On the anterior side of the same edge of the ischium is the tuberosity of the ischium.[1][2]

On the anterior side of the same edge of the ischium is the tuberosity of the ischium.[1][2]

The primary function of the pelvic bones is to transfer the load of the upper body onto the lower limbs while standing or walking. This function takes place through the connection of the axial and appendicular skeletons at the sacroiliac joint. When a man stands upright, the center of gravity lies in the center of the body. The pelvis transmits the weight to the femur and both lower extremities. The rigid structure of these bones also protects the organs that lie within their confinements. Such organs include the bladder, rectum, urethra, and uterus in females.[3]

Embryology

Pelvic bones begin their development as mesenchymal tissue of the embryonic lower limb buds. This mesenchyme begins extending out in three directions, corresponding to each of the three bones of the os coxae. The ischial and pubic masses migrate around the obturator nerve, fusing inferiorly to form the obturator foramen. Each pubic mass migrates medially to meet at the future pubic symphysis, while interactions with the primitive spinal column draw the iliac mass toward the sacrum derived from notochord mesenchyme. These mesenchymal masses then undergo endochondral ossification, with ilium, ischium, and pubis beginning primary ossification at third, fourth-to-fifth, and fifth-to-sixth months of gestation, respectively. Each bone’s primary center of ossification is near the future acetabulum, with the ossification process fanning out superiorly, inferiorly, and anteriorly in the direction of each bone. Sacral ossification begins in the third month, with each of the vertebrae having three centers of ossification. Secondary ossification occurs during the first year of life. Secondary ossification centers are at the articulation of the three pelvic bones in the acetabulum, the crest of the ilium, anterior inferior iliac spine, tuberosity of the ischium, symphysis pubis, and ramal epiphyses. These growth plates close during mid-puberty.

Each pubic mass migrates medially to meet at the future pubic symphysis, while interactions with the primitive spinal column draw the iliac mass toward the sacrum derived from notochord mesenchyme. These mesenchymal masses then undergo endochondral ossification, with ilium, ischium, and pubis beginning primary ossification at third, fourth-to-fifth, and fifth-to-sixth months of gestation, respectively. Each bone’s primary center of ossification is near the future acetabulum, with the ossification process fanning out superiorly, inferiorly, and anteriorly in the direction of each bone. Sacral ossification begins in the third month, with each of the vertebrae having three centers of ossification. Secondary ossification occurs during the first year of life. Secondary ossification centers are at the articulation of the three pelvic bones in the acetabulum, the crest of the ilium, anterior inferior iliac spine, tuberosity of the ischium, symphysis pubis, and ramal epiphyses. These growth plates close during mid-puberty. [1]

[1]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Many blood vessels are contained within the cavity created by the pelvic bones. These vessels include the common iliac artery, external and internal iliac artery, superior and inferior gluteal artery, obturator artery, superior vesical artery, and internal pudendal artery, along with their accompanying veins. Some of these arteries and their branches, such as the internal iliac, remain within the pelvic cavity while others travel out, such as the gluteals and external iliac, to supply regions such as the buttocks and lower limbs, respectively. The gonadal and uterine arteries will also run through and into the pelvic cavity, respectively, depending upon sex. Major lymph nodes in this region include the obturator, common iliac, external and internal iliac, hypogastric, superior rectal, presacral, presacral, promontory, and perirectal nodes. Nodes with the corresponding vasculature appear in pairs, one being on the anatomical left and the other on the anatomical right. Pelvic lymph nodes are a common site of prostatic and gynecologic cancer metastasis.[4][5][6][7]

Pelvic lymph nodes are a common site of prostatic and gynecologic cancer metastasis.[4][5][6][7]

Nerves

The pelvic bones, and the girdle made by them, house nerves from the lumbar and sacral plexuses. Nerves of the lumbar plexus contained in the pelvis include the genitofemoral, lateral femoral cutaneous, obturator, and femoral nerves. The genitofemoral pierces through the psoas muscle posterior-to-anterior to reach the genital region on the anterior face of the pelvis. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve leaves the spine and transverses the pelvis exiting under the anterior brim of the crest of the ilium to reach the thigh. The obturator nerve descends medially to the psoas to leave the pelvis through the obturator foramen. The femoral nerve runs between the psoas and the iliacus, emerging from the pelvis above the pubis to continue into the anterior thigh.[2][8]

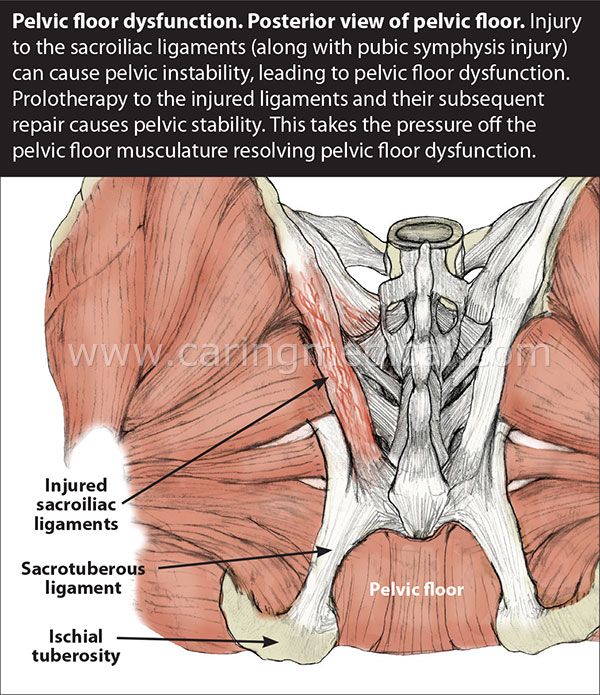

Sacral plexus nerves of the pelvis include the sciatic, superior, and inferior gluteal, posterior femoral, and pudendal nerves. The first four of these nerves all leave the pelvis traveling under the greater sciatic notch, serving innervations on the posterior gluteal and thigh regions. The superior gluteal nerve gives innervations to the gluteus minimus and medius, while the inferior gluteal innervated the gluteus maximus, which extends the hip. The pudendal nerve travels within the pelvic girdle, sending interventions to various sphincters and genitalia structures. This nerve commonly gets injured during the vaginal delivery of children.[9]

The first four of these nerves all leave the pelvis traveling under the greater sciatic notch, serving innervations on the posterior gluteal and thigh regions. The superior gluteal nerve gives innervations to the gluteus minimus and medius, while the inferior gluteal innervated the gluteus maximus, which extends the hip. The pudendal nerve travels within the pelvic girdle, sending interventions to various sphincters and genitalia structures. This nerve commonly gets injured during the vaginal delivery of children.[9]

Muscles

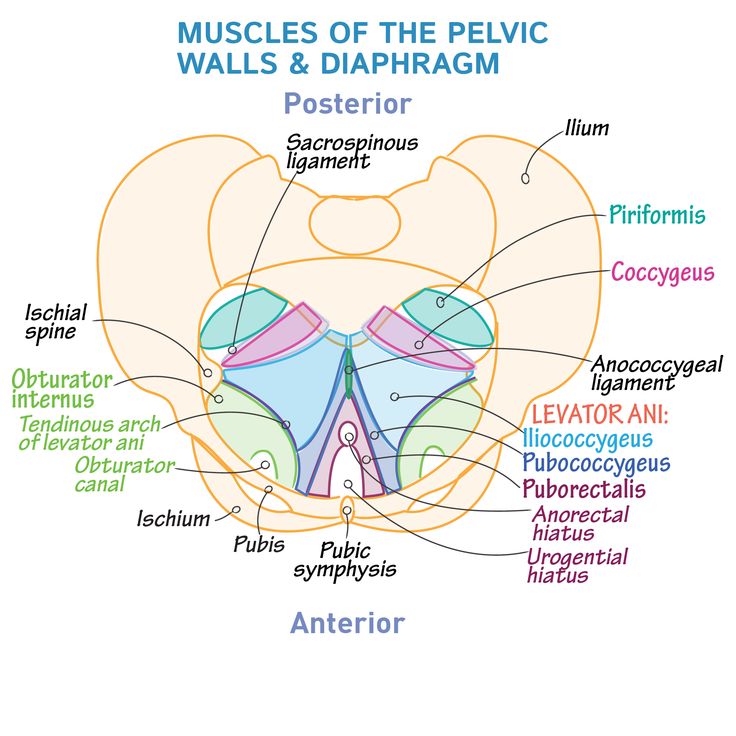

The muscles around the pelvis are essential in maintaining the stability of the pelvic girdle, maintaining an erect posture, and assisting the movement of the trunk and lower extremities.

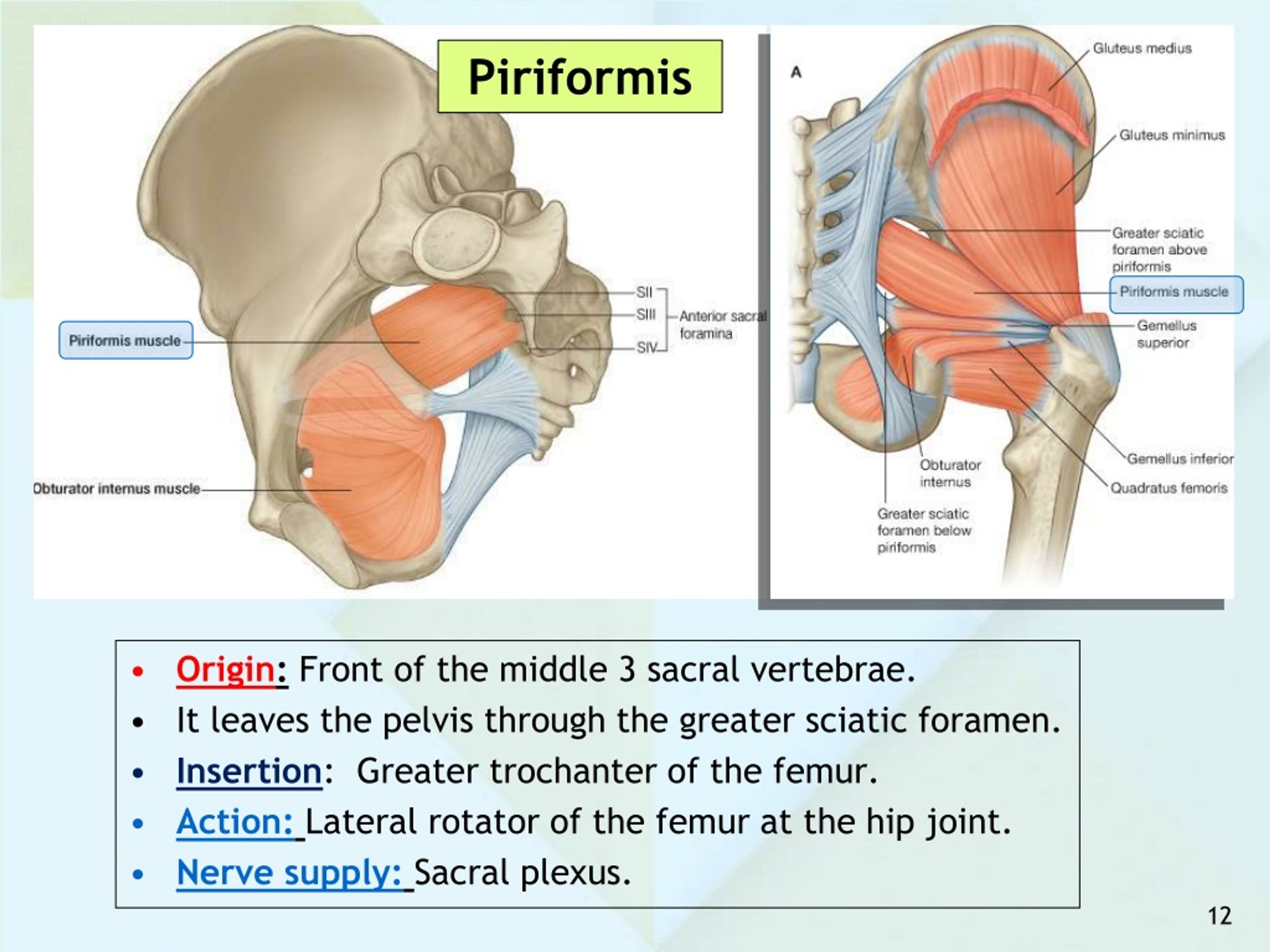

The internal iliac crest serves as the origin of the Iliacus muscle, which travels inferiorly and meets with the psoas, which originates above the pelvis but travels down through it, to make the iliopsoas. This muscle eventually exits the pelvis and inserts itself upon the femur. The piriformis is another muscle that originates inside of the pelvis and inserts externally on the femur.[10]

The piriformis is another muscle that originates inside of the pelvis and inserts externally on the femur.[10]

The pubic symphysis serves as an attachment point for both abdominal muscles, including the rectus abdominis, internal and external obliques, and transversus abdominis, as well as muscles of the adductor compartment of the leg, including the adductor brevis/longus/magnus, gracilis, and pectineus. Attached along the inferior edges of the pubis running posteriorly to the sacrum are the pelvic floor muscles, which include the puborectalis, iliococcygeal, ischiococcygeus, pubococcygeus, external anal sphincter muscles, and levator ani. The obturator internus muscles also have insertions on the internal side of the pubis and travel on the pelvic floor muscles, eventually leaving the greater sciatic notch and inserting on the posterior surface of the femur. The obturator externus travels from the anterior face of the pubis posteriorly to insert on the backside of the femur as well. The gluteal muscles, quadratus femoris, and semitendinosus muscles all also have attachments on the pelvic bones. The inguinal ligament, a common anatomical landmark involved with a hernia, runs from the anterior portion of the iliac spine to the front of the pubic symphysis.[11][12][13][14]

The gluteal muscles, quadratus femoris, and semitendinosus muscles all also have attachments on the pelvic bones. The inguinal ligament, a common anatomical landmark involved with a hernia, runs from the anterior portion of the iliac spine to the front of the pubic symphysis.[11][12][13][14]

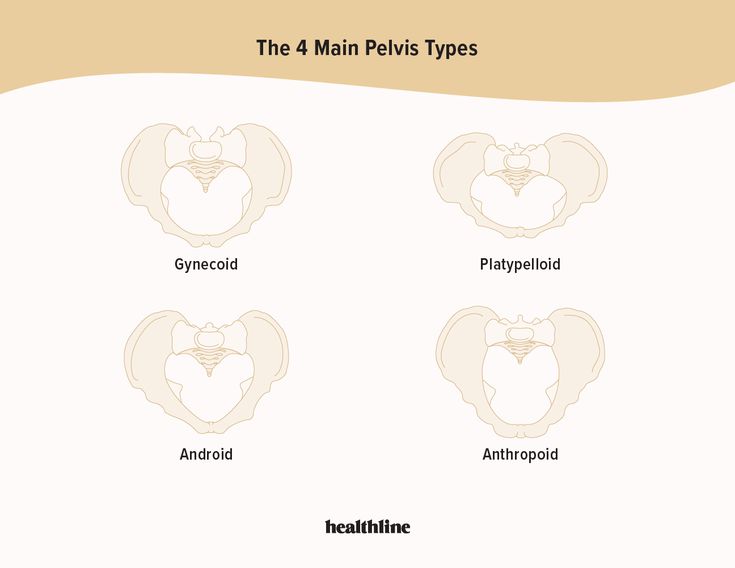

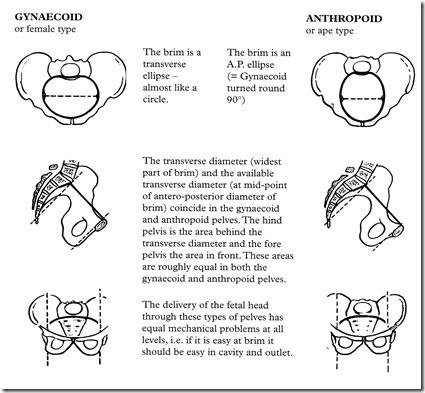

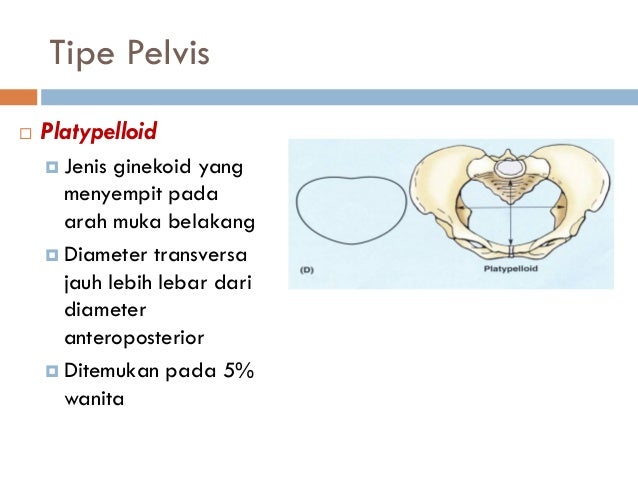

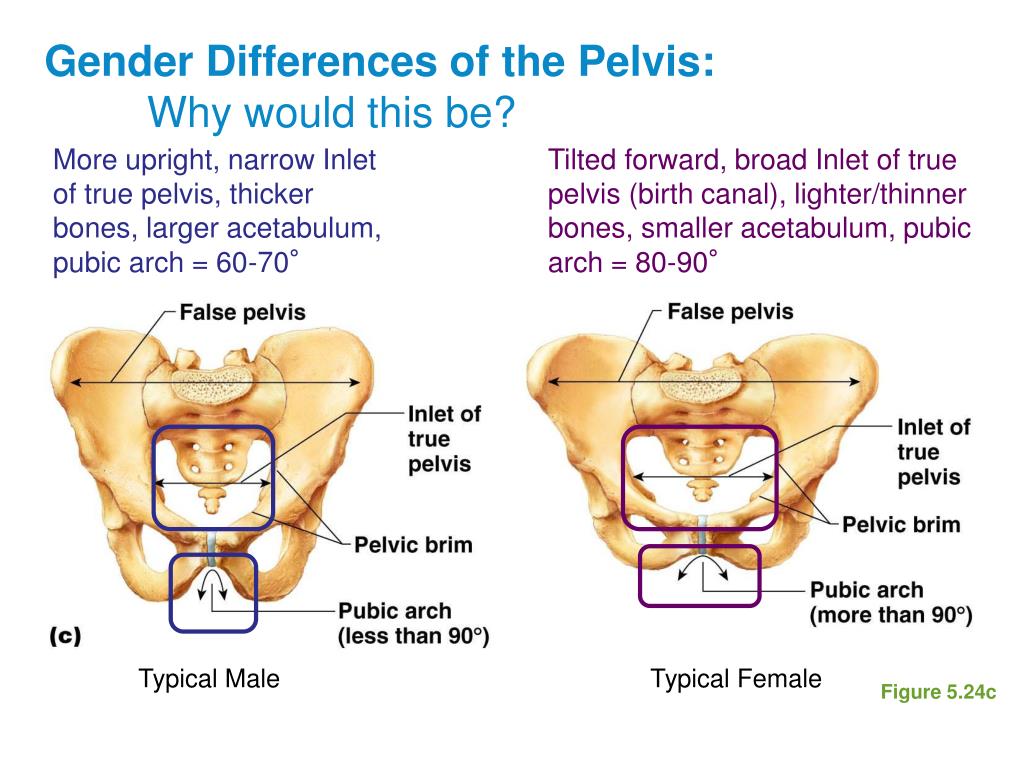

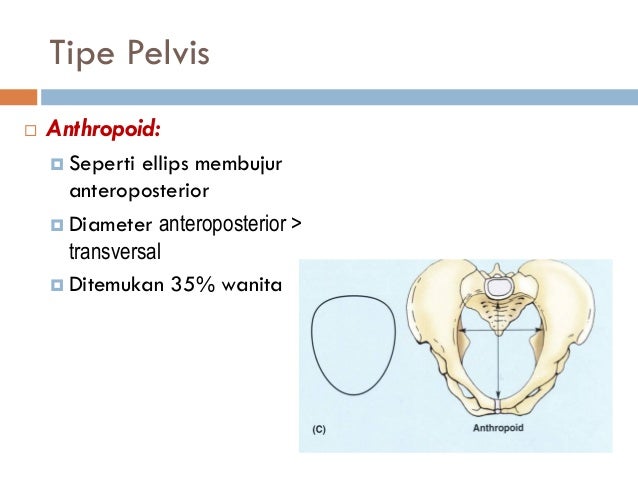

Physiologic Variants

The pelvis in females is very different from that of males; this is very important for females to provide an adequate birth canal for the large head of the fetus during birth. To achieve these means, the female pelvis is generally broader and shallower (gynecoid shape). The birth canal has to be rounded and more spacious. The sciatic notch is much wider with shorter symphysis pubis, and the pubic bones have a much broader angle with each other. The female coccyx is more mobile, and the sacrum is shorter and less curved.

Clinical Significance

A weakness of muscles of the pelvis, such as in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, will result in an abnormal waddling type of gait. A unilateral weakness of the hip abductor muscles or subluxation of a hip joint will cause a Trendelenburg gait. An analysis of how a patient walks can give clues to the underlying problems related to the structure and function of the pelvis.

A unilateral weakness of the hip abductor muscles or subluxation of a hip joint will cause a Trendelenburg gait. An analysis of how a patient walks can give clues to the underlying problems related to the structure and function of the pelvis.

Surgeries performed on pelvic structures may be complicated by excessive bleeding or hematoma formation. Surgery may also be complicated by infection and abscess formation. In the pelvis, hematoma or abscess usually remains localized in the retroperitoneal space just in front of the iliopsoas muscles. The presentation is often related to compression of the femoral plexus or the femoral nerve in the retroperitoneal space. The patient will present with postoperative weakness of the hip flexors and knee extensors with or without the involvement of the obturator muscles, depending on whether it is compression of the femoral plexus or the femoral nerve.

A female with a male type (android) of the pelvis will encounter problems during childbirth, which is one of the most prevalent indications for a caesarian section. [15]

[15]

Review Questions

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Comment on this article.

Figure

Pelvis, Male, Ilium, Arcuate Line, Pubis, Ischium, Pubis Arch, Sacrum,. Contributed by Gray's Anatomy Plates

Figure

Pelvis, Female, Pubic Arch, Brim of lesser Pelvis,. Contributed by Gray's Anatomy

Figure

Compilation of 6 images detailing anatomy of female pelvic cavity. Contributed by Gray's Anatomy Plates (Public Domain)

Figure

Pelvic nerves. Image courtesy S Bhimji MD

Figure

Pelvic bones. Image courtesy O.Chaigasame

References

- 1.

Verbruggen SW, Nowlan NC. Ontogeny of the Human Pelvis. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2017 Apr;300(4):643-652. [PubMed: 28297183]

- 2.

Navarro-Zarza JE, Villaseñor-Ovies P, Vargas A, Canoso JJ, Chiapas-Gasca K, Hernández-Díaz C, Saavedra MÁ, Kalish RA. Clinical anatomy of the pelvis and hip. Reumatol Clin.

2012 Dec-2013 Jan;8 Suppl 2:33-8. [PubMed: 23228531]

2012 Dec-2013 Jan;8 Suppl 2:33-8. [PubMed: 23228531]- 3.

DeLancey JO. What's new in the functional anatomy of pelvic organ prolapse? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Oct;28(5):420-9. [PMC free article: PMC5347042] [PubMed: 27517338]

- 4.

Spratt DE, Vargas HA, Zumsteg ZS, Golia Pernicka JS, Osborne JR, Pei X, Zelefsky MJ. Patterns of Lymph Node Failure after Dose-escalated Radiotherapy: Implications for Extended Pelvic Lymph Node Coverage. Eur Urol. 2017 Jan;71(1):37-43. [PMC free article: PMC5571898] [PubMed: 27523595]

- 5.

Ohashi H, Kikuchi S, Aota S, Hakozaki M, Konno S. Surgical anatomy of the pelvic vasculature, with particular reference to acetabular screw fixation in cementless total hip arthroplasty in Asian population. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2017 Jan 01;25(1):2309499016685520. [PubMed: 28498719]

- 6.

Lawton CA, Michalski J, El-Naqa I, Buyyounouski MK, Lee WR, Menard C, O'Meara E, Rosenthal SA, Ritter M, Seider M.

RTOG GU Radiation oncology specialists reach consensus on pelvic lymph node volumes for high-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009 Jun 01;74(2):383-7. [PMC free article: PMC2905150] [PubMed: 18947938]

RTOG GU Radiation oncology specialists reach consensus on pelvic lymph node volumes for high-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009 Jun 01;74(2):383-7. [PMC free article: PMC2905150] [PubMed: 18947938]- 7.

Charoenkwan K, Kietpeerakool C. Retroperitoneal drainage versus no drainage after pelvic lymphadenectomy for the prevention of lymphocyst formation in women with gynaecological malignancies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jun 29;6(6):CD007387. [PMC free article: PMC6353272] [PubMed: 28660687]

- 8.

O'Rahilly R, Müller F, Meyer DB. The human vertebral column at the end of the embryonic period proper. 4. The sacrococcygeal region. J Anat. 1990 Feb;168:95-111. [PMC free article: PMC1256893] [PubMed: 2182589]

- 9.

Xiaoqiang L, Xuerong Z, Juan L, Mathew BS, Xiaorong Y, Qin W, Lili L, Yingying Z, Jun L. Efficacy of pudendal nerve block for alleviation of catheter-related bladder discomfort in male patients undergoing lower urinary tract surgeries: A randomized, controlled, double-blind trial.

Medicine (Baltimore). 2017 Dec;96(49):e8932. [PMC free article: PMC5728874] [PubMed: 29245259]

Medicine (Baltimore). 2017 Dec;96(49):e8932. [PMC free article: PMC5728874] [PubMed: 29245259]- 10.

Cho JY, Moon H, Park S, Lee BJ, Park D. Isolated injury to the tibial division of sciatic nerve after self-massage of the gluteal muscle with massage ball: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 May;98(19):e15488. [PMC free article: PMC6531083] [PubMed: 31083184]

- 11.

Lee SC, Endo Y, Potter HG. Imaging of Groin Pain: Magnetic Resonance and Ultrasound Imaging Features. Sports Health. 2017 Sep/Oct;9(5):428-435. [PMC free article: PMC5582693] [PubMed: 28850315]

- 12.

Otcenasek M, Krofta L, Baca V, Grill R, Kucera E, Herman H, Vasicka I, Drahonovsky J, Feyereisl J. Bilateral avulsion of the puborectal muscle: magnetic resonance imaging-based three-dimensional reconstruction and comparison with a model of a healthy nulliparous woman. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Jun;29(6):692-6. [PubMed: 17523155]

- 13.

Nacion AJD, Park YY, Yang SY, Kim NK.

Critical and Challenging Issues in the Surgical Management of Low-Lying Rectal Cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2018 Aug;59(6):703-716. [PMC free article: PMC6037599] [PubMed: 29978607]

Critical and Challenging Issues in the Surgical Management of Low-Lying Rectal Cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2018 Aug;59(6):703-716. [PMC free article: PMC6037599] [PubMed: 29978607]- 14.

Reiner CS, Weishaupt D. Dynamic pelvic floor imaging: MRI techniques and imaging parameters. Abdom Imaging. 2013 Oct;38(5):903-11. [PubMed: 22349892]

- 15.

Abitbol MM. The shapes of the female pelvis. Contributing factors. J Reprod Med. 1996 Apr;41(4):242-50. [PubMed: 8728076]

Pelvic tilt - treatment, symptoms, causes, diagnosis

The pelvis is one of the most important, although sometimes overlooked, parts of the skeleton.

The pelvis is shaped like a basket with a tip and contains many vital organs, including the intestines and bladder. In addition, the pelvis is in the center of gravity of the skeleton. If the body is compared to a pencil balancing horizontally on a finger, its point of balance (center of gravity) will be the pelvis.

Therefore, it is obvious that the position of the pelvis greatly affects the posture. This is the same as if the central block in the tower is displaced, in which case all blocks above the displacement are at risk of falling. And if you compare the central unit with a box, then the tilt can lead to the box falling out. Similar mechanisms take place when the pelvis is tilted, and the contents of the pelvis are shifted forward. As a result, there is a protruding abdomen and bulging of the buttocks. Since the pelvis is the junction of the upper and lower torso, it plays a key role in body movement and balance. The pelvic bones support the most important supporting part of the body - the spine. In addition, the pelvis allows the lower limbs and torso to move in a coordinated manner (in tandem). When the pelvis is in a normal position, various movements are possible, twisting, tilting and movement biomechanics are balanced and the distribution of load vectors is even. Displacement (skew) of the pelvis from normal positions causes dysfunctional disorders of the spine, as there is a change in the axis of distribution of loads during movement. For example, if there is an axle shift in a car, then the wheels wear out quickly. Something similar happens in the spine, there are leverage effects and excessive load on certain points, which lead to rapid wear of the structures of the spine. Therefore, often the main cause of pain in the back and neck is a change in the position of the pelvis (displacement, distortion). A change in position changes biomechanics, which can lead to degenerative changes in the spine, to disc herniation, scoliosis, osteoarthritis, spinal canal stenosis, sciatica, etc. Pelvic tilt also leads to pain and dysfunction in the neck, neck pain radiating to the shoulders, arms, contributes to the development of carpal tunnel syndrome and other problems in the limbs.

For example, if there is an axle shift in a car, then the wheels wear out quickly. Something similar happens in the spine, there are leverage effects and excessive load on certain points, which lead to rapid wear of the structures of the spine. Therefore, often the main cause of pain in the back and neck is a change in the position of the pelvis (displacement, distortion). A change in position changes biomechanics, which can lead to degenerative changes in the spine, to disc herniation, scoliosis, osteoarthritis, spinal canal stenosis, sciatica, etc. Pelvic tilt also leads to pain and dysfunction in the neck, neck pain radiating to the shoulders, arms, contributes to the development of carpal tunnel syndrome and other problems in the limbs.

Causes of pelvic tilt (displacement)

First of all, pelvic tilt is caused by a normal muscle imbalance. Technology is developing very quickly and a sedentary lifestyle is one of the main reasons for the development of imbalance, because our body requires a certain amount of movement that it does not receive. Prolonged sitting and low physical activity are sufficient conditions for the development of muscle imbalances leading to pelvic tilt and, as a result, the appearance of dysfunctional disorders in the spine and the occurrence of back pain.

Prolonged sitting and low physical activity are sufficient conditions for the development of muscle imbalances leading to pelvic tilt and, as a result, the appearance of dysfunctional disorders in the spine and the occurrence of back pain.

Accidents and injuries are common causes of pelvic tilt , e.g. side impact, heavy lifting while twisting, falling to one side, carrying heavy loads from the side, e.g. carrying a child on the hip or carrying a heavy bag constantly on one shoulder. In women, the pelvis is less stable from birth than in men, since a certain flexibility and elasticity of the pelvic structures is necessary for the normal course of pregnancy and childbirth. Therefore, pregnancy is often the main cause of pelvic displacement in women.

Injury to the pelvic muscles is the most common cause of misalignment. Injured muscles tend to thicken and shift in order to protect the surrounding structures. If the muscles in the pelvic area, such as the sacrum, are damaged, then the tightening of the muscles will lead to an effect on the ligaments attached to the pelvis and joints. As a result, structures such as the sacroiliac joints will also have a certain disposition. Muscle compaction after damage persists until the muscle is fully restored and during this period of time the pelvis remains in an abnormal position.

As a result, structures such as the sacroiliac joints will also have a certain disposition. Muscle compaction after damage persists until the muscle is fully restored and during this period of time the pelvis remains in an abnormal position.

Difference in leg length can also cause pelvic tilt and in such cases the tilt can be from right to left or vice versa. But the displacement can also be forward or backward, or it can be twisting of the pelvis.

Many conditions can lead to muscle spasms that cause pelvic twist. Disc herniation can cause muscle spasm of an adaptive nature and, in turn, in antalgic scoliosis with functional pelvic tilt . Active people often experience tension in the calf muscles, which in turn creates tension around the pelvis. Surgery such as hip replacement can also cause the pelvis to reposition itself.

Because the pelvis is one of the most stressed areas of the body due to movement and weight support, movements that cause pain and stiffness are a clear indicator of pelvic alignment problems. Back pain in particular is a common indicator of pelvic tilt . In addition to participation in the movement in the pelvic cavity are: part of the digestive organs, nerves, blood vessels, reproductive organs. Therefore, in addition to back pain, there may be other symptoms, such as numbness, tingling, bladder and bowel problems, or reproductive problems. Most often, changes in the following muscles lead to pelvic disposition:

Back pain in particular is a common indicator of pelvic tilt . In addition to participation in the movement in the pelvic cavity are: part of the digestive organs, nerves, blood vessels, reproductive organs. Therefore, in addition to back pain, there may be other symptoms, such as numbness, tingling, bladder and bowel problems, or reproductive problems. Most often, changes in the following muscles lead to pelvic disposition:

M. Psoas major (lumbar muscle) anatomically can lead to extension and flexion of the hip, which leads to an anterior displacement of the pelvis.

M.Quadriceps (quadriceps), especially the rectus muscle, can lead to hip flexion.

M.Lumbar erectors may cause lumbar extension.

M. Guadratus lumborum with bilateral compaction can cause an increase in lumbar extension.

M.Hip adductors (adductors of the thigh) can cause the pelvis to tilt forward as a result of internal rotation of the hip. This leads to shortening of the adductor muscles.

M. Gluteus maximus (gluteus maximus) is responsible for hip extension and is an antagonist of the psoas major muscle.

M.Hamstrings The muscle of the back of the thigh, this muscle can be hardened. The muscle can be weak, at the same time hardened due to the fact that it is a synergist of the gluteus maximus muscle and this can be of a compensatory nature. The deep muscles of the abdominal wall, including the transversus abdominis and internal obliques, may become tense due to weakening of the lumbar erectors muscles

Symptoms

Symptoms of a misalignment (misalignment) of the pelvis can be both moderate and severe and significantly impair the functionality of the body. With moderate misalignment, a person may feel unsteady when walking or frequent falls are possible.

The most common symptoms are pain:

- In the lower back (radiating to the leg)

- Pain in the hip, sacroiliac joints or groin

- Pain in the knee, ankle or foot Achilles tendon

- Pain in shoulders, neck

If the pelvis is displaced for a long time, then the body will correct and compensate for the biomechanical disturbance and asymmetry and the corresponding adaptation of the muscles, tendons and ligaments will occur. Therefore, treatment may take some time. In addition, pelvic tilt can be difficult to correct, as a pathological stereotype of movements is formed over time. The longer the period of pelvic tilt, the longer it takes to restore normal muscle balance.

Therefore, treatment may take some time. In addition, pelvic tilt can be difficult to correct, as a pathological stereotype of movements is formed over time. The longer the period of pelvic tilt, the longer it takes to restore normal muscle balance.

Diagnosis and treatment

Pelvic tilt is usually well diagnosed on physical examination of the patient. If it is necessary to diagnose changes in the spine or hip joints, instrumental examination methods are prescribed, such as radiography or MRI (CT).

There are various options for the treatment of pelvic tilt and these methods depend on the cause of the pelvic tilt. In the treatment of, for example, twisting of the pelvis, it is necessary to reduce muscle damage. For this, various methods of physiotherapy, NSAIDs can be used. If the skew of the pelvis is due to the difference in the length of the limbs, then it is necessary to use individual insoles or surgical methods of treatment.

But, in any case, the treatment of pelvic tilt is effective only in combination with the impact on the pathogenetic links that led to a change in the position of the pelvis and a violation of biomechanics (physiotherapy, massage, manual therapy and exercise therapy). Exercise therapy is the leading treatment for pelvic disposition, especially when muscle problems are the cause of the pelvic tilt.

1. Transverse pelvis \ ConsultantPlus

1. Transverse pelvis

This form of the pelvis is more common in slender tall women with signs of hyperandrogenism. The sexual formula looks like: Me (menarche) - 15 - 18 years old, Ma (mamma) - 1 - 2 points, Ah (axillary hair growth) - 5 - 6 points, Ri (hair growth to the navel, on the hips and buttocks) - by male type. Morphogram: height (P) less than arm span (PP) - P < PP; the lower size (HP) is larger than the height - HP R. It is characterized by a decrease in the transverse dimensions of the small pelvis by 0.6 - 1. 0 cm or more, a relative shortening or increase in the direct size of the entrance and the narrow part of the cavity. The entrance to the small pelvis has a rounded or longitudinal-oval shape, the wings of the ilium are slightly deployed, the pubic arch is narrow.

0 cm or more, a relative shortening or increase in the direct size of the entrance and the narrow part of the cavity. The entrance to the small pelvis has a rounded or longitudinal-oval shape, the wings of the ilium are slightly deployed, the pubic arch is narrow.

In the diagnosis of a transversely narrowed pelvis, the most important is the determination of the transverse diameter of the sacral rhombus (less than 10 cm), the transverse size of the plane of entry into the pelvis (the transverse dimension of the plane of entry into the pelvis is equal to distantia cristarum or 14 - 15 cm can be subtracted from distantia cristarum to determine it) , the transverse diameter of the pelvic outlet (less than 10.5 cm), the width and height of the symphysis and the depth of the pelvis.

With a transversely narrowed pelvis, the width of the symphysis is less than 12.5 cm, the height of the symphysis is 6.5 cm or more, the transverse dimension of the pelvic outlet is less than 9see

On vaginal examination, the ischial spines converge and the terminal lines are relatively easy to reach, and the pubic angle is acute. In 50% of women with a transversely narrowed pelvis, there is a flattening of the sacrum and an increase in its height up to 10 cm or more. An accurate diagnosis of this form of the pelvis and especially the degree of its narrowing is possible only with the use of X-ray pelvimetry, computed X-ray pelvimetry or magnetic resonance imaging. Radiographically, three forms of the transversely narrowed pelvis are distinguished: with an increase in the direct diameter of the entrance, with a shortening of the direct size of the wide part of the cavity, with a decrease in the interosseous diameter. However, the mechanism of insertion of the head, which is peculiar only to this form of the pelvis, quite accurately states the shape of the pelvis.

In 50% of women with a transversely narrowed pelvis, there is a flattening of the sacrum and an increase in its height up to 10 cm or more. An accurate diagnosis of this form of the pelvis and especially the degree of its narrowing is possible only with the use of X-ray pelvimetry, computed X-ray pelvimetry or magnetic resonance imaging. Radiographically, three forms of the transversely narrowed pelvis are distinguished: with an increase in the direct diameter of the entrance, with a shortening of the direct size of the wide part of the cavity, with a decrease in the interosseous diameter. However, the mechanism of insertion of the head, which is peculiar only to this form of the pelvis, quite accurately states the shape of the pelvis.

The biomechanism of labor with a transversely narrowed pelvis can occur in the same way as with normal pelvic sizes. If the straight diameters exceed the transverse ones, then:

1) the head, bending, enters the entrance to the small pelvis with an arrow-shaped suture in a straight size and makes a translational movement to the exit plane.