Triple screening for down syndrome

Understanding the Triple Test | Sonora Quest

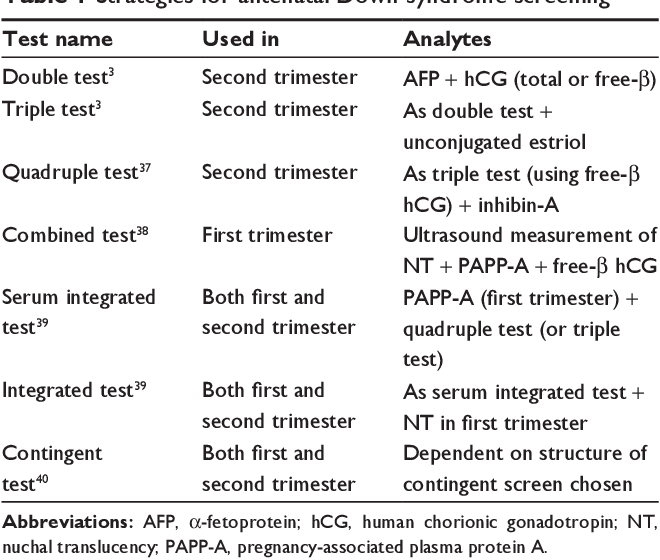

What is the Triple Test?The Triple Test is a blood test performed during pregnancy to help you and your physician learn more about your developing baby. Its purpose is to SCREEN for possible neural tube defects, Down syndrome and Trisomy 18 in the developing baby. The laboratory will measure three substances in your blood: alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and estriol.

AFP is a substance made by the baby that enters the amniotic fluid (the bag of water surrounding the baby) and the mother’s bloodstream. A small amount of AFP is normally found in the amniotic fluid and the mother’s blood. When the amount is high, it is a signal to your physician to look further for the possibility of a neural tube defect.

Estriol and hCG come from the developing baby and placenta and can be measured in the mother’s blood. A woman who is carrying a baby with Down syndrome may have lower blood levels of AFP and estriol and higher blood levels of hCG than women with unaffected babies. A woman who is carrying a baby with Trisomy 18 may have lower blood levels of AFP, estriol and hCG than women with unaffected babies. The AFP, estriol and hCG values are factored together with information about you (your age, gestational age, weight, race, and diabetic status) and risks for Down syndrome and Trisomy 18 are provided.

It is very important to remember that this is a SCREENING test and will not tell for certain that the baby has a problem.

Why should someone consider having a Triple Test?

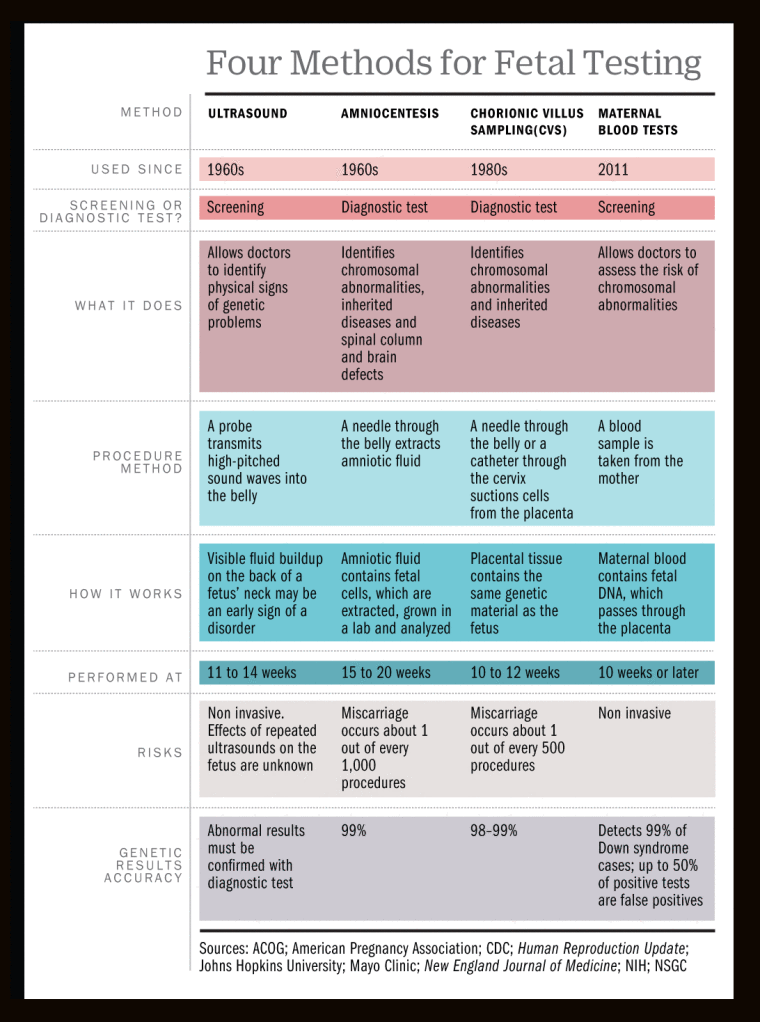

The Triple Test has been available to pregnant women for many years now and can provide you and your physician with the important information about your pregnancy. MSAFP (Maternal serum AFP) may lead to the detection of up to 85% of open neural tube defects when used in conjunction with diagnostic procedures such as ultrasound and amniocentesis. Abnormal Triple Test results followed by ultrasound and amniocentesis may lead to the detection of 60 to 70% of Down syndrome pregnancies and many Trisomy 18 pregnancies. In addition to providing information about potential neural tube defects, Down syndrome and Trisomy 18 the Triple Test may provide information that could help to identify twins, find certain other abnormalities that may be present and alert your physician to increased risks for other pregnancy complications.

In addition to providing information about potential neural tube defects, Down syndrome and Trisomy 18 the Triple Test may provide information that could help to identify twins, find certain other abnormalities that may be present and alert your physician to increased risks for other pregnancy complications.

A normal Triple Test is a SCREENING test and does not guarantee that you will have a healthy baby. The test is simply not able to detect every pregnancy with a neural tube defect, Down syndrome or Trisomy 18. Thus, some women with a normal Triple Test result may still have a baby with a neural tube defect, Down syndrome or Trisomy 18.

Who should have the Triple Test?

Triple Test screening may be offered to all pregnant women, regardless of their maternal age or family history. In most cases, the Triple Test provides reassurance that the baby is developing normally. It is important for you to understand the benefits and the limitations of the Triple Test. Discuss any questions or concerns with your physician.

Discuss any questions or concerns with your physician.

When do I get the Triple Test?

The Triple Test can be performed any time between 15 and 21.9 weeks after the first day of your last menstrual period. The highest detection rate for open neural defect is 16 to 18 weeks. The results of the test, with a full explanation, are generally available to your physician within 48 to 96 hours.

What is a Neural Tube Defect?

The neural tube is part of the unborn baby that develops into the spine and brain. In approximately one in every 500 developing babies, there is a defect in the development of the neural tube, resulting in either spina bifida or anencephaly. Spina bifida means, “open spine”. Children born with open spine require surgery to close the opening. They also may have various medical problems, such as trouble with bowel and bladder control, walking and learning. The degree of disability varies from one child to the next depending on the size and location of the opening. Anencephaly, a more severe abnormality involving incomplete development of the brain and skull, usually results in death before or shortly after birth.

Anencephaly, a more severe abnormality involving incomplete development of the brain and skull, usually results in death before or shortly after birth.

Am I at risk for having a baby with a Neural Tube Defect?

Any one can have a baby with neural tube defect. If someone in your family was born with a neural tube defect, you need to discuss this with your physician, since your baby has a greater risk of a neural tube defect. If you have no family history, then your risk is no greater than the general population risk. However, you should be aware that most babies with neural tube defects are born to parents with no family history to such problems.

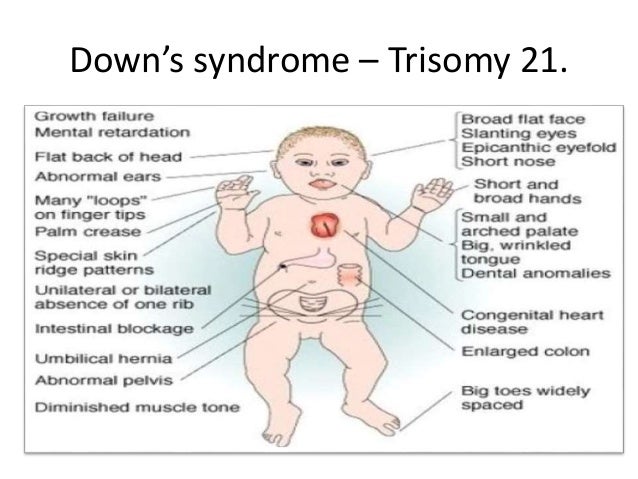

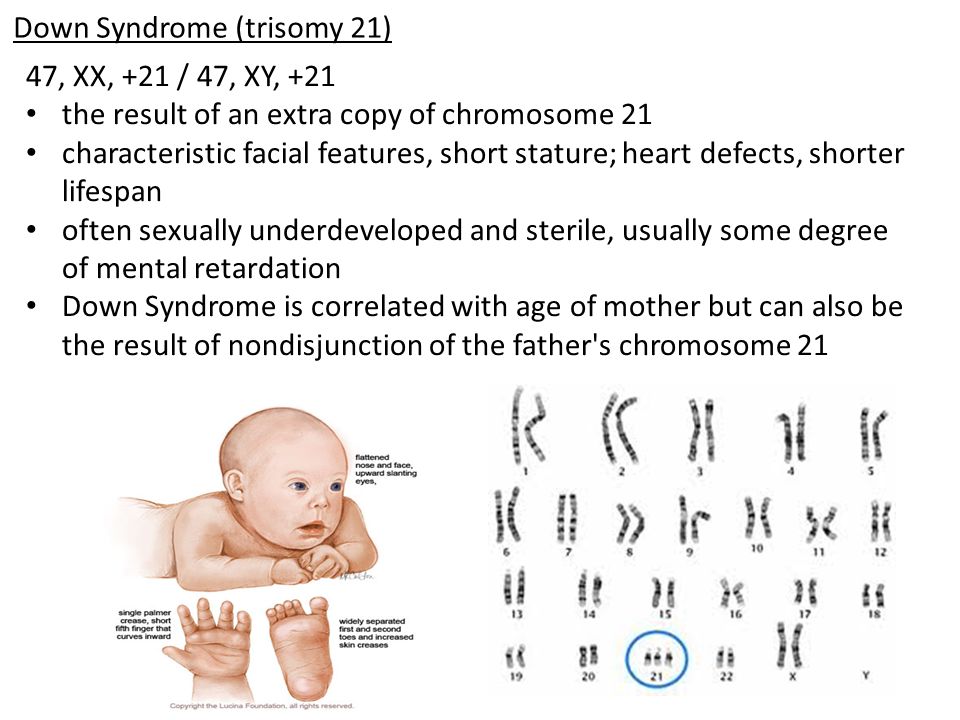

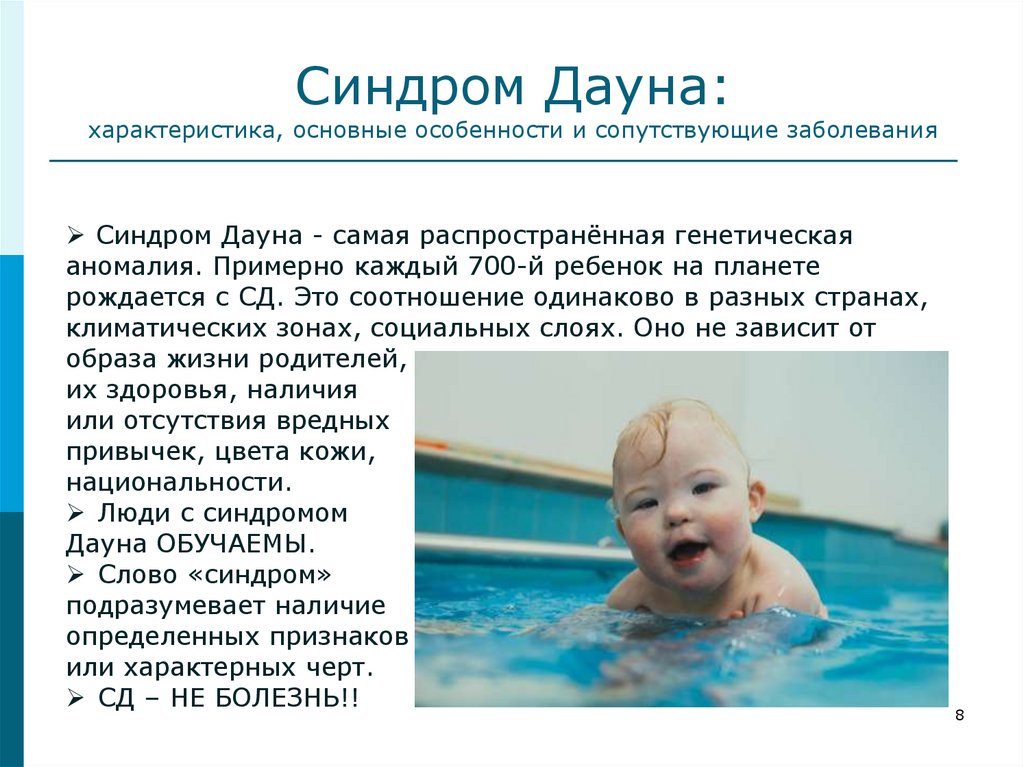

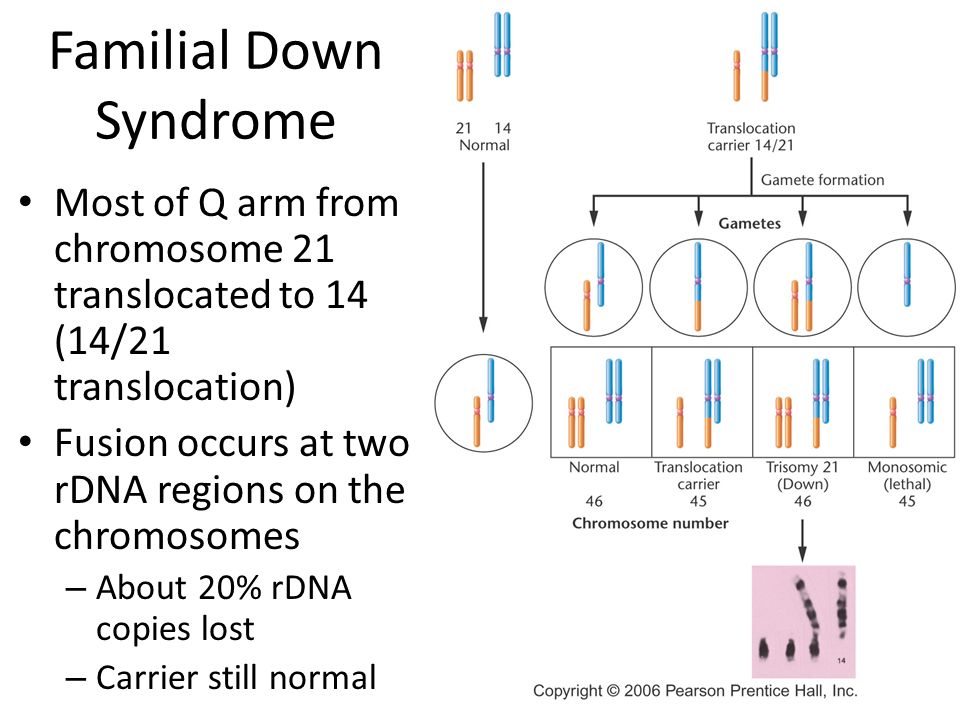

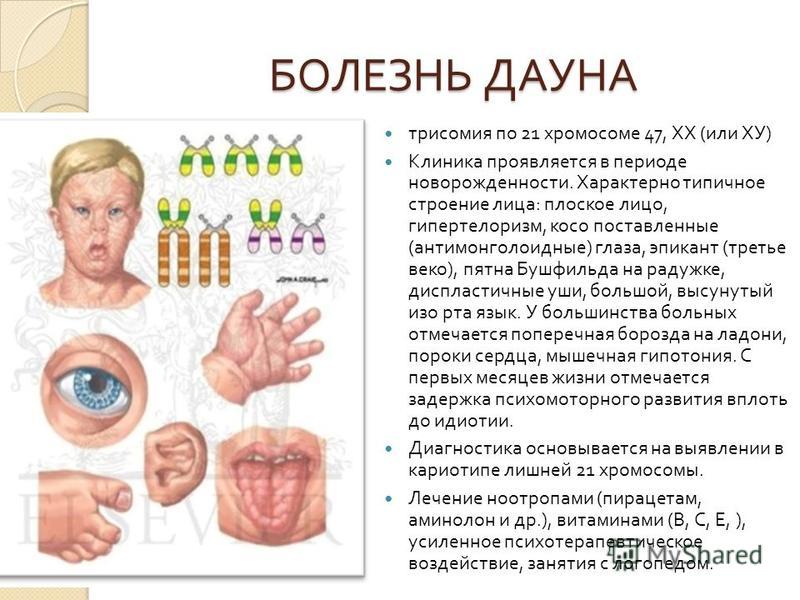

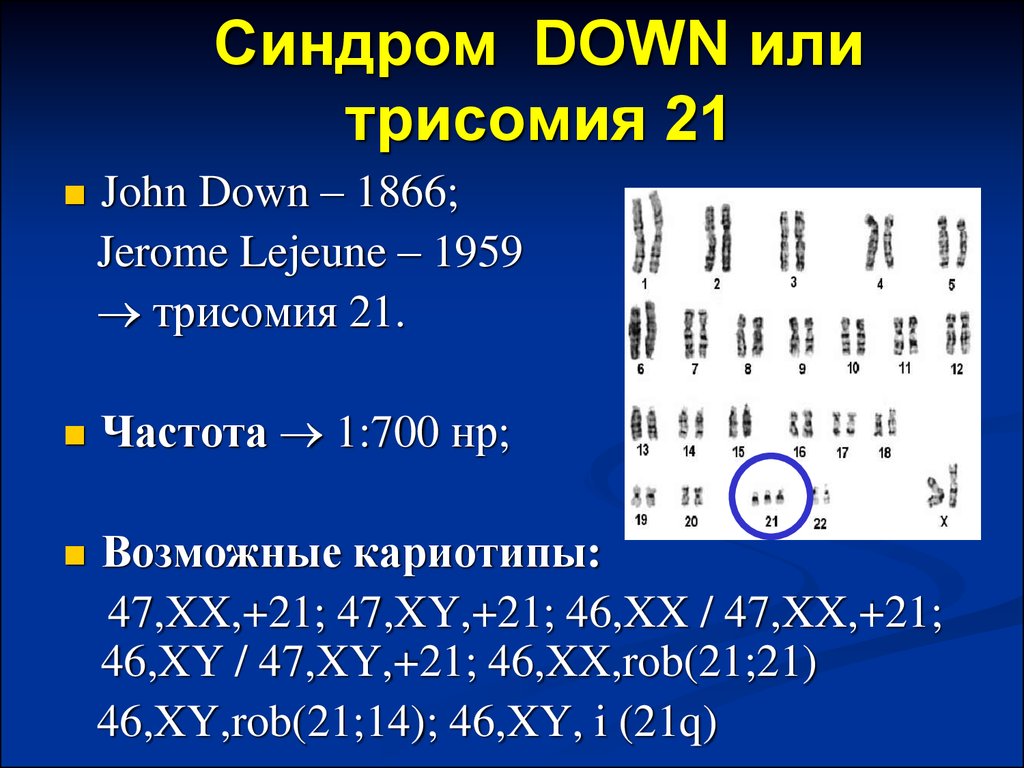

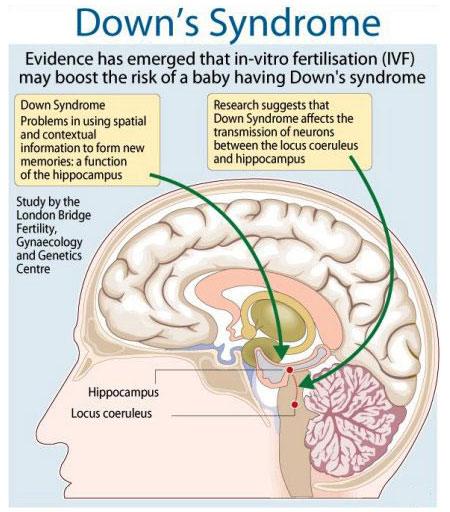

What is Down Syndrome?

Down syndrome is a disorder caused by an extra chromosome, a structure that contains genetic material that determines physical and mental characteristics. Children with Down syndrome have abnormalities that may include mental retardation, heart defects and other health problems.

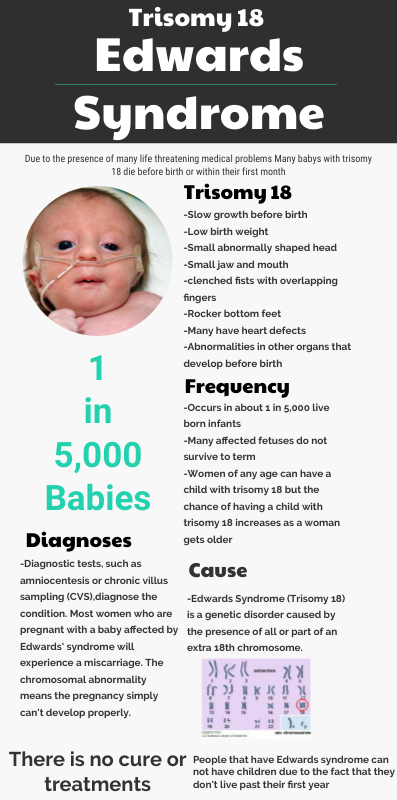

What is Trisomy 18?

Trisomy 18 is another disorder caused by an extra chromosome. Children with Trisomy 18 also have mental retardation, heart defects and other health problems but are more severely affected and generally die in early childhood. Trisomy 18 is much less common than Down syndrome.

Am I at risk for having a baby with Down Syndrome or Trisomy 18?

As with neural tube defects, anyone can have a child with Down syndrome or Trisomy 18. The chances of having a baby with Down syndrome or Trisomy 18 depend on your age. As a woman gets older, her chances increase. In general, a woman 35 years old or older is offered prenatal testing (amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling) based on her age alone.

What if my result is screen positive for Down Syndrome or Trisomy 18?

Low MSAFP and estriol combine with high hCG concentrations may be found in pregnancies with Down syndrome. Low levels of MSAFP, estriol and hCG are often found in pregnancies with Trisomy 18. These abnormal Triple Test results also may be due to a pregnancy that is less far along than what was thought previously. Following an abnormal result, some physicians may recommend an ultrasound to verify the baby’s age or amniocentesis to study the baby’s chromosomes.

These abnormal Triple Test results also may be due to a pregnancy that is less far along than what was thought previously. Following an abnormal result, some physicians may recommend an ultrasound to verify the baby’s age or amniocentesis to study the baby’s chromosomes.

What if my MSAFP result is elevated?

An elevated MSAFP result does not necessarily indicate that the baby has a neural tube defect. Since the levels of MSAFP depend, among other factors, on the age of the developing fetus, a test result may appear to be high, but may not be if the baby’s age has been miscalculated. There are also other possible causes, including twin pregnancy, vaginal bleeding and the presence of less common birth defects. Occasionally, MSAFP results are elevated for no apparent reason.

What does a negative screen mean?

A negative screen means that your baby probably does not have a neural tube defect, Down syndrome or Trisomy 18. Further testing is not required. A negative screen however, does not guarantee that your baby will not have some form of birth defect.

Further testing is not required. A negative screen however, does not guarantee that your baby will not have some form of birth defect.

←Back

The triple test as a screening technique for Down syndrome: reliability and relevance

1. Reynolds T, Penney M. The mathematical basis of multivariate risk analysis: with special reference to screening for Downs syndrome associated pregnancy. Ann Clin Biochem. 1990;27:452–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Spencer K. Accuracy of Down’s syndrome risks produced in a prenatal screening program. Ann Clin Biochem. 1999;36:101–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Wald NJ, Cuckle HS, Densem JW, et al. Maternal serum screening for Down’s syndrome in early pregnancy. BMJ. 1988;297:883–887. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Wald NJ, Cuckle HS, Densem JW, Kennard A, Smith D. Maternal serum screening for Down’s syndrome: the effect of routine ultrasound scan determination of gestational age and adjustment of maternal weight. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;99:144–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;99:144–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Department of Health UK National Screening Committee NHS Fetal Anomaly Screening Programme (NHS FASP): Report 2006/2008. Available from: http://fetalanomaly.screening.nhs.uk/standardsandpolicies/getdata.php?id=11016. Accessed Jan 26, 2010.

6. Harrison G, Goldie D. Second-trimester Down’s syndrome serum screening: double, triple or quadruple marker testing? Ann Clin Biochem. 2006;43:67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Fuchs K, Peipert J. First Trimester Down Syndrome Screening: Public Health Implications. Semin Perinatol. 2005;29:267–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Perinatal Institute for Maternal and Child Health 3 Stage contingency screening for Down’s syndrome – Stafford pilot – Final report to the UK National Screening Committee. Available from: http://www.pi.nhs.uk/screening/downs/index_downscreeningreport.htm.

9. Department of Health UK National Screening Committee National Down’s Syndrome Screening Programme for England: Antenatal Screening – Working Standards for Down’s Syndrome Screening 2007. Available from: http://fetalanomaly.screening.nhs.uk/standardsandpolicies/getdata.php?id=10849. Accessed Jan 26, 2010.

Available from: http://fetalanomaly.screening.nhs.uk/standardsandpolicies/getdata.php?id=10849. Accessed Jan 26, 2010.

10. Department of Health UK National Screening Committee NHS Fetal Anomaly Screening Programme – Screening for Down’s syndrome: UK NSC Policy recommendations 2007–2010: Model of Best Practice. Available from: http://fetalanomaly.screening.nhs.uk/standardsandpolicies/getdata.php?id=10848. Accessed Jan 26, 2010.

11. Department of Health UK National Screening Committe FASP Progress Update – Autumn 2009. Available from: http://fetalanomaly.screening.nhs.uk/standardsandpolicies/getdata.php?id=10848. Accessed Jan 26, 2010.

12. American College of Gynecologists New Recommendations for Down Syndrome: Screening Should Be Offered to All Pregnant Women. Available from: http://www.acog.org/from_home/publications/press_releases/nr01-02-07-1.cfm. Accessed Jan 26, 2010.

13. Driscoll DA, Morgan MA, Schulkin J. Screening for Down syndrome: changing practice of obstetricians. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:459.e1–e9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:459.e1–e9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Genetics in Family Medicine: The Australian Handbook for General Practitioners. Available from: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/file/your_health/egenetics/practioners/gems/sections/03%20%20Testing%20and%20pregnancy%20WEB.pdf. Accessed Jan 26, 2010.

15. Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada Prenatal Screening for Fetal Aneuploidy. Available from: http://www.sogc.org/guidelines/documents/187E-CPG-February2007.pdf. Accessed Jan 27, 2010.

16. Reynolds T. Downs syndrome screening is unethical: Views of today’s ethics committees. J Clin Path. 2003;56:268–270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Bell M, Stoneman Z. Reactions to prenatal testing: reflection of religiosity and attitudes toward abortion and people with disabilities. Am J Ment Retard. 2000;105:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Julian C, Huard P, Gouvernet J, Mattei JF, Ayme S. Physicians’ acceptability of termination of pregnancy after prenatal diagnosis in southern France. Prenat Diagn. 1989;9:77–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Prenat Diagn. 1989;9:77–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Bouchard L, Renaud M, Kremp O, Dallaire L. Selective abortion: a new moral order? Consensus and debate in the medical community. Int J Health Serv. 1995;25:65–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Stuck J, Faine J, Boldt A. The perceptions of Lutheran pastors toward prenatal genetic counseling and pastoral care. J Genet Couns. 2001;10:251–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Kuppermann M, Nease RF, Learman LA, Gates E, Blumberg B, Washington AE. Procedure-related miscarriages and Down syndrome-affected births: implications for prenatal testing based on women’s preferences. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:511–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Moyer A, Brown B, Gates E, Daniels M, Brown HD, Kuppermann M. Decisions about prenatal testing for chromosomal disorders: perceptions of a diverse group of pregnant women. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 1999;8:521–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Gudkov L, Tichtchenko P, Yudin B. Human genetic improvement: a comparison of Russian and British public perceptions. Bull Med Ethics. 1998;134:20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Human genetic improvement: a comparison of Russian and British public perceptions. Bull Med Ethics. 1998;134:20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Li Y, Shan Z, Teng W, et al. Maternal thyroid function abnormalities during pregnancy affect neuropsychological development of their children at 25–30 months. Clin Endocrinol. 2009 Oct 31; [Epub ahead of print] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Reynolds T. The Ethics of Antenatal Screening: Lessons from Canute. Clin Biochem Rev. 2009;30:187–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Walknowska J, Conte FA, Grumbach MM. Practical and theoretical implications of fetal/maternal lymphocyte transfer. Lancet. 1969;1:1119–1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Simpson JL, Elias S. Fetal cells in maternal blood: prospects for non-invasive prenatal diagnosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;731:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Lo YMD, Corbetta N, Chamberlain PF, et al. Presence of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum. Lancet. 1997;350:485–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1997;350:485–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Lo YMD, Hjelm NM, Fidler C, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of fetal RhD status by molecular analysis of maternal plasma. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1734–1738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Costa JM, Benachi A, Gautier E. New strategy for prenatal diagnosis of X-linked disorders. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Finning K, Martin P, Summers J, Massey E, Poole G, Daniels G. Effect of high throughput RhD typing of fetal DNA in maternal plasma on use of anti-RhD immunoglobulin in RhD negative pregnant women: prospective feasibility study. BMJ. 2008;336:816–818. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Lo YMD, Chiu RWK. Prenatal diagnosis: progress through plasma nucleic acids. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:71–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Lo YMD, Tsui NBY, Chiu RWK, et al. Plasma placental RNA allelic ratio permits noninvasive prenatal chromosomal aneuploidy detection. Nat Med. 2007;13:218–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Tong YK, Jin S, Chiu RWK, et al. Noninvasive prenatal detection of trisomy 21 by an epigenetic-genetic chromosome-dosage approach. Clin Chem. 2010;56:90–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Dawson A, Jones G, Matharu M, et al. Serum screening for Down’s syndrome: a summary of one year’s experience in South Wales. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:875–877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Benn PA, Chapman AR. Practical and ethical considerations of noninvasive prenatal diagnosis. JAMA. 2009;301:2154–2156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Wald NJ, Densem JW, George L, Muttukrishna S, Knight PG. Prenatal screening for Down’s syndrome using inhibin-A as a serum marker. Prenatal Diagn. 1996;16:143–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Spencer K, Souter V, Tul N, Snijders R, Nicolaides KH. A screening programme for trisomy 21 at 10–14 weeks using fetal NT, maternal serum free beta-hCG and PAPP-A. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999;13:231–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Wald NJ, Watt HC, Hackshaw AK. Integrated screening for Down’s syndrome based on tests performed during the first and second trimesters. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:461–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wald NJ, Watt HC, Hackshaw AK. Integrated screening for Down’s syndrome based on tests performed during the first and second trimesters. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:461–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Wright D, Bradbury I, Benn P, Cuckle H, Ritchie K. Contingent screening for Down syndrome is an efficient alternative to non-disclosure sequential screening. Prenatal Diagn. 2004;24:762–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Wald NJ, Rodeck C, Hackshaw AK, Walters J, Chitty L, Mackinson M. First and second trimester antenatal screening for Down’s syndrome: the results of the Serum, Urine and Ultrasound Screening Study (SURUSS) Health Technol Assess. 2003;7:1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Prenatal screening for trisomies of the second trimester of pregnancy (triple test)

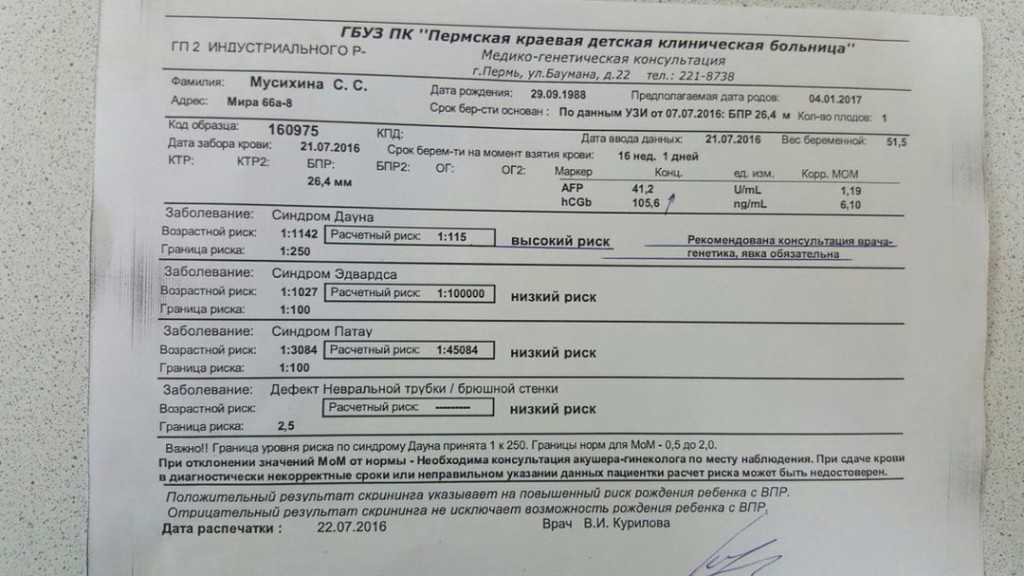

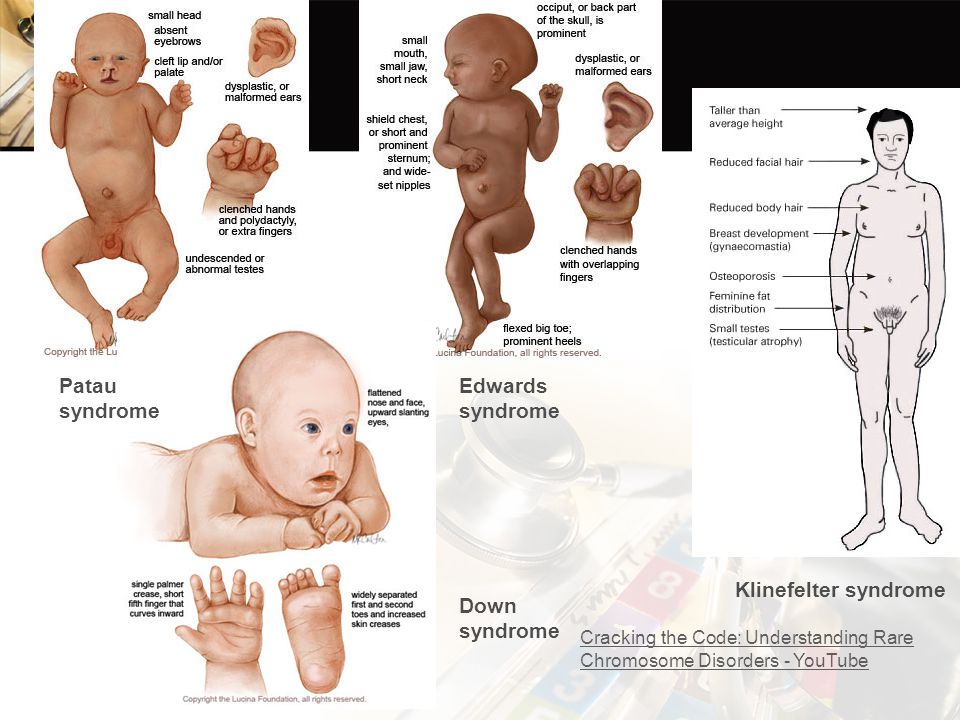

Prenatal screening for trisomy of the second trimester of pregnancy is also called a triple test - this is a study that allows you to determine the likely risk of developing chromosomal diseases such as Down's disease, Edwards syndrome, Patau syndrome, neural tube defects, and other fetal anomalies.

What are the dangers of genetic abnormalities for the fetus

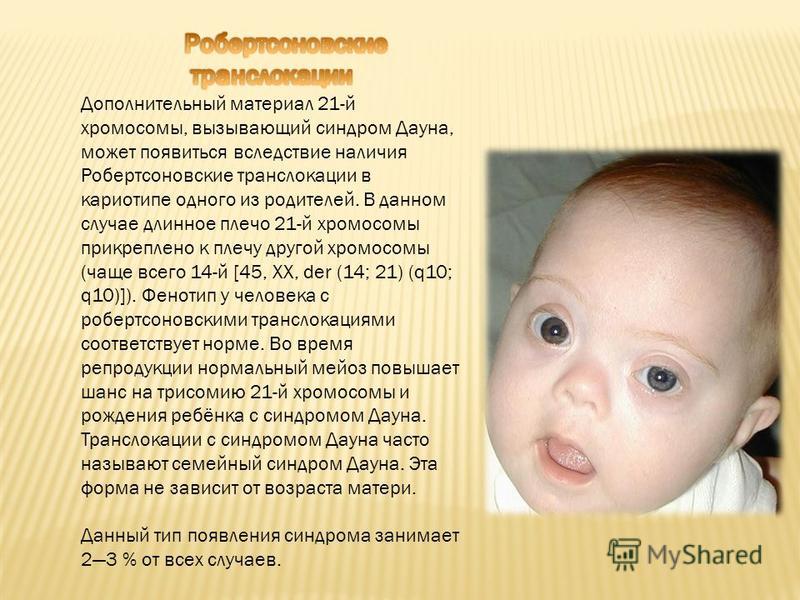

Down syndrome is the most common genetic anomaly. Children with this diagnosis have serious physical and mental abnormalities, half of the newborns are diagnosed with heart disease. Immediately or over time, problems with vision, with the thyroid gland, with hearing may appear. Statistics say that every 700-800th child is born with this pathology. This fact does not depend on the lifestyle of the parents, their state of health or ecology. Scientists have found that the cause lies in the trisomy of the 21st chromosome (the presence of three homologous chromosomes instead of a pair).

Edwards syndrome is also a chromosomal anomaly; with the full form of this disease, oligophrenia develops to a complicated degree; with a mosaic form, it may not manifest itself so clearly. In the case of this syndrome, the woman in labor has trisomy on the 18th chromosome.

Patau's syndrome is also characterized by physical defects and mental retardation. The disease is caused by trisomy on the 13th chromosome.

The disease is caused by trisomy on the 13th chromosome.

One of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in newborns is neural tube defects (NTDs), including anencephaly and spina bifida. The first defect is a gross malformation of the brain, the second is a malformation of the spine, often combined with defects in the development of the spinal cord.

How is the triple test done?

To detect an anomaly at an early stage, screening is carried out between 14 and 22 weeks of gestation. Blood is taken from a woman in labor as a biomaterial. The day before, fatty foods are contraindicated for the patient, half an hour before the study, it is required to exclude physical and emotional overstrain, as well as smoking.

During the test, the level of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), alpha-fetoprotein and free estriol is checked. According to these indicators, one can judge the successful course of pregnancy or identify violations of the development of the fetus.

The study takes into account age, weight, number of fetuses, race, bad habits, the presence of diabetes and medications taken. At the end of the test, the pregnant woman is prescribed a consultation with an obstetrician-gynecologist.

Important! Based on the results of screening, they do not make a diagnosis, nor are they a reason for artificial termination of pregnancy. The test makes it possible to determine the need for invasive methods for examining the fetus. If the risks of an anomaly are high, then a mandatory additional study is prescribed.

Where to get prenatal screening for trisomy II trimester

You can conduct a study quickly and comfortably at any convenient branch of the Medical Commission No. 1 network. The centers are located in 7 districts of the city, equipped with their own modern laboratories and have all the necessary licenses. We employ certified professionals with extensive experience. The test results will be ready as soon as possible.

Make an appointment at a convenient time on our website or by phone +7 (812) 380-82-54

Book an appointment >>>

Get tested for Down syndrome in the 2nd trimester of pregnancy

Test material Blood serum

Home visit available

Synonyms: Triple test of the second trimester of pregnancy.

Maternal Screen, Second Trimester; Prenatal Screening II, PRISCA II, Prenatal Risk Calculation.

Attention! For this study, the results of ultrasound are required!

Biochemical screening of the second trimester of pregnancy "triple test" of the second trimester consists of the following tests:

Brief description of the study "Prenatal screening for trisomy 2 trimesters of pregnancy, PRISCA-2"

PRISCA-2 - biochemical screening of the 2nd trimester of pregnancy (recommended at 16-18 weeks of pregnancy). Assessment of the risk of Down syndrome (trisomy 21), Edwards syndrome (trisomy 18) and neural tube defect (NTD) in the fetus. Includes a "triple test" of the 2nd trimester and the calculation of the statistical risk of fetal chromosomal pathology based on the obtained biochemical parameters, the results of fetal fetometry (ultrasound) and individual data of the pregnant woman using the PRISCA software.

Assessment of the risk of Down syndrome (trisomy 21), Edwards syndrome (trisomy 18) and neural tube defect (NTD) in the fetus. Includes a "triple test" of the 2nd trimester and the calculation of the statistical risk of fetal chromosomal pathology based on the obtained biochemical parameters, the results of fetal fetometry (ultrasound) and individual data of the pregnant woman using the PRISCA software.

Research results are quantified using the PRISCA software.

The determination of hCG, AFP and free estriol is used to screen pregnant women in the second trimester of pregnancy to assess the risk of chromosomal abnormalities and fetal neural tube defects. The study is carried out between 15 and 20 weeks of pregnancy. The optimal timing for 2nd trimester screening is between 16 and 18 weeks of pregnancy.

Conducting a comprehensive examination at 11-14 weeks of gestation, including ultrasound and determination of maternal serum markers (hCG free beta subunit and PAPP-A), followed by a complex software calculation of the individual risk of giving birth to a child with a chromosomal pathology, is recommended for all pregnant women by order of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation No. 1130-n of October 20, 2020 “On approval of the procedure for providing medical care in the field of obstetrics and gynecology ...). With normal 1st trimester screening results, a separate AFP determination can be used in the 2nd trimester to rule out a neural tube defect (see Test #92), or a complete PRISCA 2nd trimester profile. A triple biochemistry test with complex software risk calculation in the 2nd trimester may be particularly appropriate for borderline risk assessment results in 1st trimester screening, and also if, for some reason, 1st trimester screening was not performed on time.

1130-n of October 20, 2020 “On approval of the procedure for providing medical care in the field of obstetrics and gynecology ...). With normal 1st trimester screening results, a separate AFP determination can be used in the 2nd trimester to rule out a neural tube defect (see Test #92), or a complete PRISCA 2nd trimester profile. A triple biochemistry test with complex software risk calculation in the 2nd trimester may be particularly appropriate for borderline risk assessment results in 1st trimester screening, and also if, for some reason, 1st trimester screening was not performed on time.

PRISCA (developed by Typolog Software, distributed by Siemens) is an EU-certified (CE-certified) and registered for use in the Russian Federation program that supports risk calculation for screening examinations of the 1st and 2nd trimesters of pregnancy. The risk calculation is carried out using a combination of biochemical markers informative for the corresponding period and ultrasound indicators. 1st trimester ultrasound data performed at 11-13 weeks of gestation can be used to calculate risks in the PRISCA program during 2nd trimester biochemical screening. At the same time, the PRISCA program will conduct an integrated risk calculation taking into account the value of NT (thickness of the nuchal space of the fetus) relative to the median values of this indicator for the gestational age at the date of its measurement in the 1st trimester.

1st trimester ultrasound data performed at 11-13 weeks of gestation can be used to calculate risks in the PRISCA program during 2nd trimester biochemical screening. At the same time, the PRISCA program will conduct an integrated risk calculation taking into account the value of NT (thickness of the nuchal space of the fetus) relative to the median values of this indicator for the gestational age at the date of its measurement in the 1st trimester.

Critical to a correct calculation is the accuracy of the individual data provided, the qualifications of the ultrasound provider in performing prenatal screening ultrasound measurements, and the quality of the laboratory tests.

Description of the pathologies detected in the study "Prenatal screening for trisomies of the 2nd trimester of pregnancy, PRISCA-2"

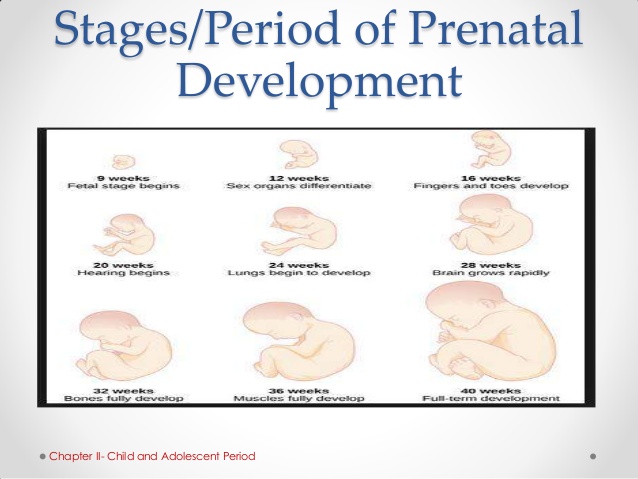

Down syndrome (trisomy 21) half of the cases) and the severity of manifestations. It is characterized by intellectual retardation, impaired bone growth, a characteristic phenotype and other physical features. The birth rate of children with Down syndrome is approximately 1:750. The risk of having a baby with Down syndrome depends on the age of the mother. For women under the age of 25, the probability of having a child with Down syndrome is 1/1400, up to 30 years old - 1/1000, at 35 years old the risk increases to 1/350, at 42 years old - up to 1/60, and at 49years - up to 1/12. However, since young women generally have many more children, the majority (80%) of all Down syndrome patients are actually born to young women under the age of 35. Therefore, screening studies to assess the risk of this anomaly are included in the list of recommended examinations for all pregnant women in the 1st trimester (Order of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation No. 1130-n of 10/20/2020). Edwards syndrome (trisomy 18) is characterized by gross physical anomalies and intellectual retardation. This is a lethal condition: 50% of sick children die in the first two months of life, 95% - during the first year of life.

The birth rate of children with Down syndrome is approximately 1:750. The risk of having a baby with Down syndrome depends on the age of the mother. For women under the age of 25, the probability of having a child with Down syndrome is 1/1400, up to 30 years old - 1/1000, at 35 years old the risk increases to 1/350, at 42 years old - up to 1/60, and at 49years - up to 1/12. However, since young women generally have many more children, the majority (80%) of all Down syndrome patients are actually born to young women under the age of 35. Therefore, screening studies to assess the risk of this anomaly are included in the list of recommended examinations for all pregnant women in the 1st trimester (Order of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation No. 1130-n of 10/20/2020). Edwards syndrome (trisomy 18) is characterized by gross physical anomalies and intellectual retardation. This is a lethal condition: 50% of sick children die in the first two months of life, 95% - during the first year of life. Girls are affected 3-4 times more often than boys. The frequency of occurrence of this anomaly in the population ranges from one case per 6,000 births to one case per 10,000 births (about 10 times less than Down syndrome).

Girls are affected 3-4 times more often than boys. The frequency of occurrence of this anomaly in the population ranges from one case per 6,000 births to one case per 10,000 births (about 10 times less than Down syndrome).

Patau's syndrome (trisomy 13) , characterized by the presence of an extra chromosome 13, is manifested by severe malformations, most of these children die in the first weeks and months of life. The frequency of occurrence is about 1:5000-10000 births.

Neural tube defects (NTDs) in most cases result from failure to close or reopen the ends of the neural tube. Depending on the location of the defect, either anencephaly or a malformation of the spine (spina bifida) is formed, which can be clinically manifested by paralysis of the lower extremities, bladder, rectum, etc. The pathogenesis is multifactorial: the occurrence of NTD is due to both hereditary factors and exposure environmental factors. The incidence of NTD varies by population (from 0. 2 to 2 per 1000 newborns).

2 to 2 per 1000 newborns).

Principles for determining the risk of fetal chromosomal pathology

Based on complex multicenter examinations, the most significant biochemical markers were determined, the level of which in maternal blood significantly deviates in one direction or another from the average values in the presence of the indicated types of chromosomal pathology in the fetus, as well as indicators of fetal ultrasound , correlating with the frequency of detection of chromosomal abnormalities. The reference values and medians of these indicators at different stages of normal pregnancy were determined (the median corresponds to the value of the indicator for the "average" woman, 50% of women with the same gestational age have values below, and the other 50% - above the median).

1. Biochemical markers

Biochemical markers used in prenatal screening are substances synthesized by the fetus or placenta that enter the mother's bloodstream. 1st trimester of pregnancy: free beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (see test No. 189) and PAPP-A (see test No. 161), which make it possible to judge the risk of having a child with Down syndrome (an increase in free β-hCG and decrease in PAPP-A) and Edwards syndrome (characterized by a decrease in free β-hCG and a decrease in PAPP-A). 2nd trimester of pregnancy: AFP (see test No. 92), total β-hCG (see test no. 66) and free estriol (see test no. 134). This complex of markers makes it possible to judge the risk of having a child with Down syndrome (an increase in β-hCG, a decrease in free estriol, a decrease in AFP), Edwards syndrome (a decrease in β-hCG, a decrease in free estriol, a decrease in AFP), a neural tube defect (an increase in AFP).

1st trimester of pregnancy: free beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (see test No. 189) and PAPP-A (see test No. 161), which make it possible to judge the risk of having a child with Down syndrome (an increase in free β-hCG and decrease in PAPP-A) and Edwards syndrome (characterized by a decrease in free β-hCG and a decrease in PAPP-A). 2nd trimester of pregnancy: AFP (see test No. 92), total β-hCG (see test no. 66) and free estriol (see test no. 134). This complex of markers makes it possible to judge the risk of having a child with Down syndrome (an increase in β-hCG, a decrease in free estriol, a decrease in AFP), Edwards syndrome (a decrease in β-hCG, a decrease in free estriol, a decrease in AFP), a neural tube defect (an increase in AFP).

2. Ultrasound parameters

Of particular importance for assessing the risk of chromosomal pathology is such an indicator of ultrasound as the thickness of the collar space (the width of the accumulation of subcutaneous fluid on the back of the fetal neck; synonyms: TVP, width of the cervical fold, width of the cervical transparency, collar zone, NT, Nuchal Translucency). Measurement of the collar space is carried out up to 14 weeks of pregnancy, optimally 11-13 weeks of pregnancy. Accurate measurement of TVP requires the qualification of an ultrasound doctor and is performed according to modern developed standards on high-resolution equipment. Down syndrome is characterized by an increase in TVP. 1st trimester ultrasound data can be used to calculate risk for 2nd trimester biochemical screening. The PRISCA program allows you to calculate the combined risk, taking into account the MoM TVP for the gestational age at the date of measurement of TVP in the 1st trimester.

Measurement of the collar space is carried out up to 14 weeks of pregnancy, optimally 11-13 weeks of pregnancy. Accurate measurement of TVP requires the qualification of an ultrasound doctor and is performed according to modern developed standards on high-resolution equipment. Down syndrome is characterized by an increase in TVP. 1st trimester ultrasound data can be used to calculate risk for 2nd trimester biochemical screening. The PRISCA program allows you to calculate the combined risk, taking into account the MoM TVP for the gestational age at the date of measurement of TVP in the 1st trimester.

3. Correction factors

In addition to the gestational age, the concentration of biochemical markers in the blood of a pregnant woman depends on the number of fetuses, ethnicity, weight of the woman (with increasing weight, the volume of fluid increases, and the concentration of markers decreases due to dilution), the presence of diabetes mellitus (with insulin-dependent diabetes, the risk of a neural tube defect is increased and there is a trend towards a lower level of AFP), smoking, the fact of pregnancy due to IVF.