Child adoption in australia

What is the adoption process in Australia and why don't more children get adopted?

Asking people who want kids why they don't "just adopt" is a common refrain but actual adoption in Australia isn't all that common.

Just 334 adoptions were finalised in 2019-20.

So why don't more adoptions happen and what's really involved in the process?

There are a few reasons for this and we have to look at the three types of adoption to understand why.

Local adoption is probably what you think of when you hear the word "adoption". This is the adoption of children not known to their adoptive parents.

Known-child adoption means the child is already known to their adoptive parents (think foster carers or relatives).

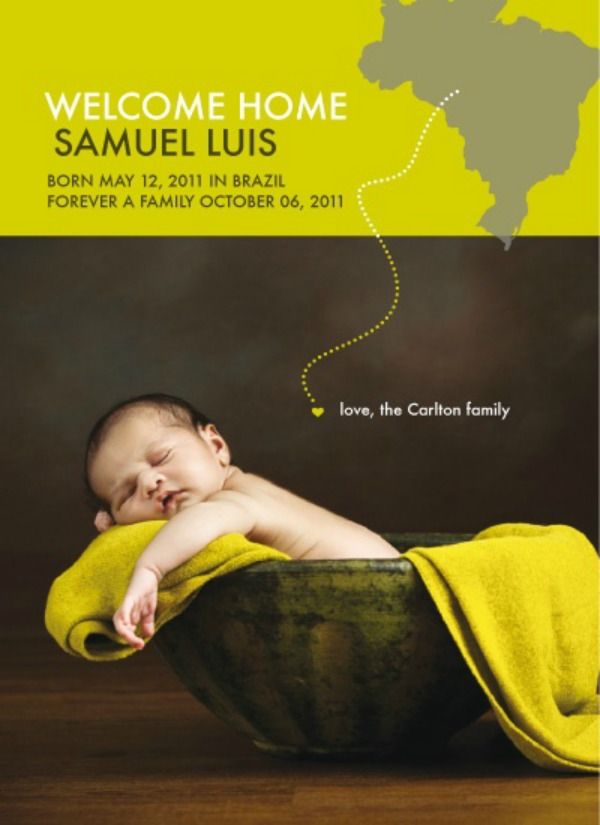

And then there's intercountry adoption, i.e.the adoption of children from overseas.

Known-child adoptions are rising but the other two are going down.

Intercountry adoption has decreased since the 1990s because of ethical concerns. To give you a sense of how few of these happen, only 37 intercountry adoptions were finalised in 2019-20.

"And local adoption has declined because we live in a different culture now compared to when there was forced adoption," explains Renee Carter, chief executive of Adopt Change.

"There isn't the stigma that used to exist around being a single mother. There aren't as many people choosing to place a child into adoption."

Just 48 local adoptions were completed in 2019-20.

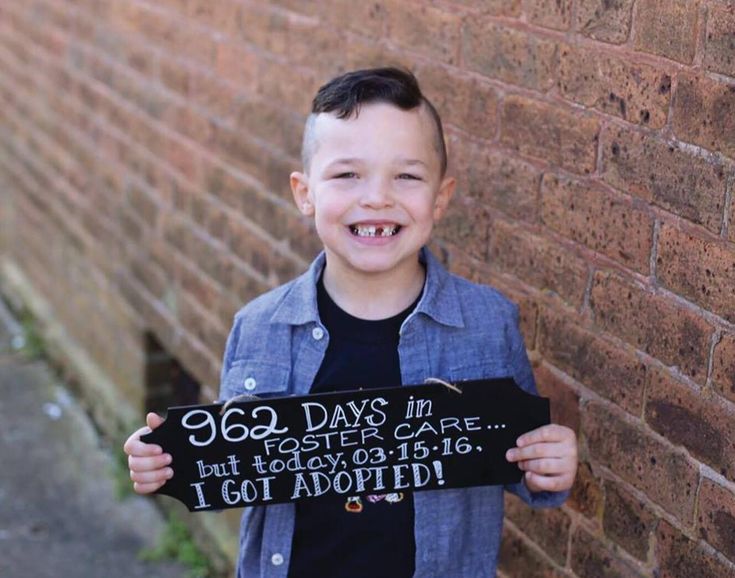

"Meanwhile, a number of states have been introducing legislation so that there's a timeframe of two years for having permanency plans, such as adoption, in place for children in care who can't return home," Ms Carter says.

"So there's been an increase in [known-child adoption because] carers who have had kids in their care for years [have been] formalising that through adoption."

The laws and requirements around adoption and who's allowed to adopt vary across Australia and based on adoption type.

If you'd like specific information tailored to your state or territory, check out the relevant government websites below:

- Victoria

- New South Wales

- Australian Capital Territory

- Queensland

- Northern Territory

- Western Australia

- Tasmania

- South Australia

Generally speaking, a prospective adoptive parent needs to be an adult who is "available and able to provide for the child until they turn 18," says Kay Berry, Barnardos Australia's head of adoptions.

This means they need to be in reasonable health, and must undergo police and working with children checks.

Upper age limits are generally less of a barrier these days; in 2019-20, 44 per cent of local adoptive parents were 40 and over.

"And it's even higher for known-child adoptions, so that is a shift, even looking back a few years ago," Ms Carter says.

But if you're looking at intercountry adoptions, age limits for prospective adoptive parents vary depending on the country you're looking to adopt from.

The acceptance of single adoptive parents depends on the place you're adopting from and on the individual case. This applies to both intercountry adoptions and adoptions from within Australia.

Before you begin the actual application process, experts say you should think about your motivation for adopting.

"This comes in all different forms, but a key part should be about helping a child in need because these are very vulnerable children," Ms Berry says.

Another big thing to consider is that Australia now practices open adoption, which means birth family contact is expected throughout children's lives. You'd need to be confident and comfortable with facilitating that.

Adoption is "open" in Australia, which means birth family contact is expected until the child turns 18. (Adobe Stock: conceptualmotion)

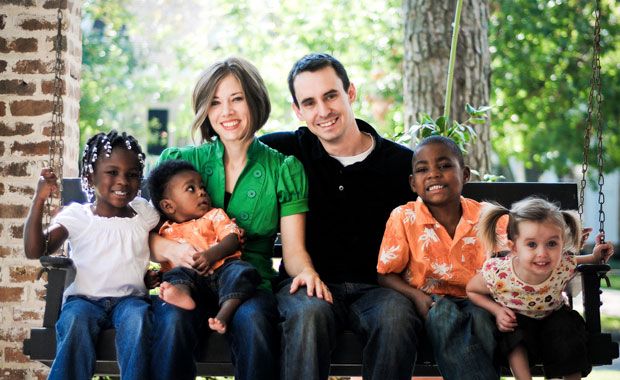

(Adobe Stock: conceptualmotion)Any child who comes into your care will have a history, and all children have different needs, though there are obvious differences between bringing a baby home versus an older child.

If you're adopting an infant, the expectation is generally that there will be a full-time carer at home for a certain time period, Ms Carter explains.

"Sometimes it suits prospective parents who need to keep working to have school-aged kids, and we have a huge need for homes for older children," she says.

If you think this could be right for you, Ms Berry says you should also be prepared for the fact that "older children often have more needs".

"Many have been in situations of domestic violence, many have delayed development and require specialist interventions … some children may have NDIS care plans."

And if you want to adopt a child with a different cultural background to you, Ms Berry says you need to be prepared to actively integrate their culture into your daily life.

"Involved" is the word Ms Berry lands on to describe the adoption application process.

"It can be quite an exposing thing because many people get to hear more about your lives than would normally be shared," she says.

Exactly how "involved" the process is depends on the pathway and adoption type you're considering.

The local and known-child adoption processes generally involve getting in touch with your relevant state department or an accredited adoption agency after doing your research.

Next come the information sessions, assessment and training (if you'd like more information on this, this NSW-specific website outlines this part of the process generally).

"The assessment part includes things like medical interviews and home checks," Ms Carter says.

Then, you wait to be matched. (More on how long this can take below.)

That's followed by placement and post-adoptive/placement support. Finally, the adoption is approved by the court in your jurisdiction.

There are heaps of variables for intercountry adoptions. For a better understanding of this process and the concerns that come with it, start with this official government website.

But generally, people looking to adopt children from overseas must meet the eligibility criteria of the state or territory they live in, as well as that of the partner country, go through a similar assessment and training process and finally be approved by a state or territory central authority, or meet immigration requirements.

Be a part of the ABC Everyday community by joining our Facebook group.

The question of how long it takes is another difficult one to answer beyond "it depends".

But there are some general guides.

The median wait time for intercountry adoption is just under three years.

"And local adoption can take less time," Ms Carter says.

"With known adoptions, often the carer has had that child in their care already, but it still usually takes at least a couple of years [to complete].

"If you put your hand up for foster care, within a year that you start the process and go through authorisation, you can have a child in your home."

This article contains general information only. Refer to your local government for details around laws and requirements regarding adoption.

ABC Everyday in your inbox

Get our newsletter for the best of ABC Everyday each week

Posted , updated

New South Wales – Adopt Change

NSW Agencies

Where to Start

If you are considering taking on the permanent care of a child (including through adoption), we recommend you first read our information on How Adoption Works In Australia.

As each state has its own legislation, agencies and variables, the next step is to assess the options for providing a permanent home to a child in NSW and determine which is right for you.

Currently in NSW there are five possible pathways for providing a permanent home for a child:

- Local adoption

- Intercountry adoption

- Carer adoption (Adoption from foster care)

- Guardianship

- Long-term foster care

In NSW we operate a service called My Forever Family NSW, which is funded by NSW Government. Contact us to support you through exploring and starting the carer journey. Our details and information can be found on the My Forever Family page.

Local Adoption

The Department of Family and Community Services (FACS) is the government agency responsible for providing adoption services in NSW.

FACS does not approve very many people for local adoption, but aims to have a pool of applicants of varying backgrounds and characteristics approved for local adoption to enable us to meet the various needs of the children for whom adoption is being considered.

In NSW children might have an adoption plan made by the birth parent(s) to place them for adoption; children are usually under the age of two in these cases. The birth parents are involved in the selection of adoptive parents for their children.

Other approved adoption agencies

A number of accredited adoption agencies also provide adoption services in NSW.

The information in this fact sheet applies to Government processes. Please contact the agencies listed below for information about their adoption processes.

Anglicare Adoption Services

Call: 02 9890 6855

Australian Families for Children (AFC)

Call: 02 9389 1889

Barnardos Australia Adoptions (Find-a-Family)

Adoption of children from birth to 12 years

Call: 02 8596 5000

Family Spirit Adoption Services

Call: 8709 9333

Email: [email protected]

Intercountry Adoption

FACS also manages the applications and assessments for those applying to adopt children through one of Australia’s intercountry adoption programs.

The role of FACS is to ensure that those applying to adopt children through these programs meet the requirements for adoption, that they have received the appropriate training and information, and to ensure that appropriate post-adoption support is received.

Costs

There are administrative and legal costs relating to a local and intercountry adoption NSW.

Additionally, intercountry adoption involves costs such as air-fares when you travel to meet and bring home your child, and visa and immigration fees.

For both local and intercountry adoption you should also factor in the time you will spend away from the workforce in order to support, and form a relationship with, your adopted child when they return home with you.

More information about fees can be found in the Thinking About Adoption fact sheet.

Criteria

To adopt a child in NSW you must be at least 21 years of age, resident or domiciled in NSW and meet legislated eligibility criteria for adoption applicants which can be found in the Thinking About Adoption fact sheet.

If you wish to be approved for intercountry adoption you will need to indicate which country you are applying to, and meet the eligibility requirements for that country as well as the requirements for NSW.

Information about the various intercountry adoption programs and criteria can be found on the Intercountry Adoption Australia website.

Applying to Adopt a Child – Local and Intercountry Programs

In NSW the process for applying to adopt a child through either the local or intercountry programs is the same:

- Read the fact sheet Thinking About Adoption.

- Request an Adoption Information Package (details on how to do this are included in the Thinking About Adoption fact sheet)

- Complete and submit an Expression of Interest form

- If you meet the preliminary criteria you will be invited to attend a three-day Preparation for Adoption seminar in Sydney

- Complete a formal application (including medical reports, criminal record checks, personal references, birth and marriage certificates and if applicable certificate(s) of naturalisation)

- Undergo a detailed assessment.

This is carried out by an Adoption Assessor who will conduct a series of visits to your home to talk with you in-depth about your application, and prepare a report and recommendations about your suitability to adopt a child.

This is carried out by an Adoption Assessor who will conduct a series of visits to your home to talk with you in-depth about your application, and prepare a report and recommendations about your suitability to adopt a child.

Approval

For local adoption, the final decision about your suitability to adopt is made by the Manager Caseworker Adoption & Permanent Care.

Intercountry adoption applicants’ approved assessment reports will be forwarded to the overseas adoption program for consideration, and the final decision as to whether your application is approved is made by the overseas adoption authority.

For more information about the process please refer to the FACS website.

Permanency Placement Principles

NSW has developed permanent placement principles to guide placing a child or young person who has been removed from their home for their well-being, safely in a permanent home.

The first step is to work intensively with the family to address the issues that led to their child’s removal. NSW is implementing a number of evidence-based programs with the aim of increasing the numbers of children who can safely return to live with their birth family.

NSW is implementing a number of evidence-based programs with the aim of increasing the numbers of children who can safely return to live with their birth family.

The guidelines set out the timeframes for when the Children’s Court must decide if returning a child to their parent is possible. If it is decided that it is not possible, then one of the following alternative permanency pathways will be sought for that child according to their situation and needs.

- Carer adoption (for non-Aboriginal children)

- parental responsibility to the Minister (long-term foster care)

Please note that adoption is not usually considered suitable for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (refer to the Placement Principle). Guardianship is the preferred permanency pathway for indigenous children. If Guardianship is not possible or suitable, then long-term foster care will usually be considered next rather than adoption.

If you are already a Foster Parent/Carer your Case Manager or other qualified person should discuss in detail the pros and cons of adoption, Guardianship and long-term foster care for your family. The following information provides an overview in summary.

The following information provides an overview in summary.

Guardianship

Under a Guardianship order, a child or young person is not in foster care or out of home care, but in the independent care of their guardian.

A guardian is a person who provides a caring, safe home for a child or young person until they turn 18 years old. Guardians have full care and responsibility for a child or young person in their care. The Children’s Court can make a guardianship order for a child or young person who needs care and protection or who is currently in out-of-home care.

Criteria

Guardianship is for a relative or kinship carer (or sometimes an authorised foster carer), who is considering seeking long-term full parental responsibility for a child or young person. Under a guardianship order, a guardian takes on full parental responsibility of the child or young person, making all decisions about their care until they reach 18 years of age.

Read more about Guardianship.

A guardian can be a relative or kinship carer, a family friend or an authorised carer who has an established and positive relationship with the child or young person. For Aboriginal children and young people, guardians who are not relatives or kin should be Aboriginal people in order to be considered ‘suitable persons’.

Applying to Become a Guardian

Anyone wanting to become a guardian will go through a detailed review and assessment process. This includes seeking the views of the child or young person, their family and their carer. Children or young people aged 12 years or older must give their written consent to a guardianship order being made, where they are capable of doing so.

The Children’s Court makes the final decision about a guardianship order being made.

If you would like to find out more about becoming a guardian, visit the Pathways to Permanency website or call the FACS Guardianship Information line on 1300 956 416.

Carer Adoption

If a child has lived with a carer for at least two consecutive years and restoration to their birth family or Guardianship to a member of their extended family is not considered appropriate, the Foster Parent/Carer may be able to apply to adopt the child in their care.

As with Guardianship, the views of the child or young person will be taken into consideration. Children or young people aged 12 years or older must give their written consent to an adoption order being made, where they are capable of doing so.

Applying

Foster Parents/Carers should let their Case Manager know that they wish to adopt.

Applicants should be aware that even for existing Foster Parents/Carers the assessment process is still rigorous and can be lengthy.

If you do not already have a child in your care, the FACS accredited adoption agencies listed above offer long-term foster care, with the possibility of being able to adopt the child in your care if it is considered in their best interest.

If you would like to find out more about carer adoption visit the Pathways to Permanency website or call the FACS Open Adoption Hotline on 1800 003 227.

Long-term Foster Care

Under the new NSW Permanency Placement Principles, long-term foster care is considered to be the least preferred option for the majority of children. However for some children, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, long-term foster carers will still be needed.

However for some children, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, long-term foster carers will still be needed.

To apply to become a foster carer in NSW you can be single, married, in a de facto relationship or same-sex relationship. To be eligible you must be:

- ideally over the age of 25

- an Australian citizen or permanent resident

- in good health

- without a criminal record

Applying to become a foster carer

The Department has transferred most of the provision of out-of-home care to non-government agencies. You can find a list of these agencies below.

It is also possible to become a Foster Parent/Carer with the Department in some areas of NSW, and for specific groups of children. Currently, the Department is recruiting carers:

- who can offer emergency care

- who can offer emergency care who can offer short-term care

- to care for Aboriginal children

- to care for children with a disability

- to care for sibling groups (two or more children and/or young people).

As with Guardianship and Adoption, applicants must submit an expression of interest, attend pre-approval training, and go through a detailed assessment process.

Child Migration_eng

The Australian Embassy in Moscow can apply for one of the following subclass visas.

• Child (subclass 101) - For children of an Australian citizen; a person permanently residing in Australia; or an eligible New Zealand citizen

• Dependent Child (subclass 445) - For children with a parent in Australia on a Spouse Temporary visa and in the process of obtaining a permanent visa

• Adoption (Subclass 102) - For children who have been adopted or are being adopted by an Australian citizen, Australian resident or eligible New Zealand citizen at the time of adoption

• Orphan/Child left without parental care (relative) (subclass 117) - For children whose parents are deceased, incapacitated, or their whereabouts are unknown, and the children have an eligible sponsor

For more information on immigrant visas for children, please visit the Department's website.

• Immigration visas for children

• Reference material, immigration of children

How to submit an application

• Visa Application

The Australian Embassy in Moscow recommends applying for immigrant visas for children and dependent children by mail or courier.

1. Sending documents/application by mail or courier

If you apply by mail or courier we will send you confirmation of receipt of your application on the day we receive and register your documents. You must provide all documents listed in the checklist for applying for an immigrant child visa or a dependent child visa. Please check that the payment details are correct on the form, or attach proof of payment of the visa fee (if paid in Australia).

List of Required Documents

By clicking on this link List of Documents for Immigrant Child Visa you can find a list of documents required to be submitted to the Australian Embassy in Moscow for a child, adoption, orphan (relative) visa.

By clicking on this link List of Documents for Child Immigrant Visa subclass 445 , Dependent Child, you will find a list of documents required to be submitted to the Australian Embassy in Moscow for a Dependent Child visa.

List of required documents

By clicking on this link List of documents for a child immigrant visa, you can find a list of documents required to be submitted to the Australian Embassy in Moscow for a child, adoption, orphan (relative) visa.

By clicking on this link List of Documents for Immigrant Child Visa Subclass 445, Dependent Child, you will find a list of documents required to be submitted to the Australian Embassy in Moscow for a Dependent Child visa.

Medical requirements

All applicants for a permanent Australian visa must meet established medical requirements.

Please do not undergo a medical examination until you have been instructed to do so by a member of the Australian Embassy in Moscow.

You do not need to contact your application officer to check if he/she has received the results of your medical examination. The officer will contact you if no results have been received.

More information can be found here: Medical Requirements

June 2014

Australia: National Adoption Considerations | RefNews

Rethinking contemporary and historical adoption experiences will help thousands of children in foster care, says a new report from Australian experts.

Australia is known as the Land of the Lucky, but the almost 40,000 children in orphanages waiting for a permanent home with loving parents and the many spouses who want to adopt a child are hardly lucky.

Adoptions in Australia have declined by a staggering 97% over the past 40 years, from nearly 10,000 adoptions in 1971-72 to to just 339 in 2012-13, with almost a third of them made overseas. Other countries also experienced a decline in adoptions, albeit not much compared to Australia.

Are we really taking better care of children in need? Or is the fact that a large number of them are in shelters a sign that we have preferred ideological and bureaucratic concerns to their interests? A new report from the Australian Women's Forum "Adoption Rethink" shows that the latter is closer to the truth.

The report examines the decline in adoptions from various perspectives, including the current rise in legal abortions, feminist theory and media coverage. It tracks how this practice, once seen as a natural and obvious solution to the needs of children who are unable to be raised by their own parents, has fallen out of favor in recent decades, and how it affects the growing number of children being raised outside the family.

Closed adoptions, stolen generations

At the forefront of this recent story are women who abandoned their children at birth in a time when single mothers were viewed with disapproval. Sometimes these women were under pressure to give up babies without knowing the adoptive parents or expecting to ever see their child again. These women speak of their grief and the wound they have received. Already grown children, who were adopted / adopted under the same “closed” regime, also complained about their painful “quest” to find their biological parents, their full identity. Studies conducted among such people revealed a high level of mental disorders in them.

These women speak of their grief and the wound they have received. Already grown children, who were adopted / adopted under the same “closed” regime, also complained about their painful “quest” to find their biological parents, their full identity. Studies conducted among such people revealed a high level of mental disorders in them.

Historical errors that lead us to speak of the Stolen Generations (separating Aboriginal children from their families), lost innocents (the "export" of 7,000 children from the UK in the early 20th century) and Lost Australians (hundreds of thousands of Australians who spent their childhoods in orphanages) have also contributed to the bleak notion of adoption over the past ten years.

At the same time, the population of children who could benefit from adoption has also changed. Early 19In the 1970s, at least half of the adoptions involved the children of young unmarried women. They, themselves almost children, were encouraged, even forced to give away a child they could not raise alone, and instead encouraged to strive to complete their education, find a job and get married. Now those norms have changed with benefits, abortions and birth control pills.

Now those norms have changed with benefits, abortions and birth control pills.

Is another lost generation on the way?

Today's picture is very different from the past. Most children in Australia (and similar countries) in need of foster parents have been taken from their biological parents due to physical, sexual or emotional abuse, neglect, and placed in foster homes. The number of these children has doubled over the past decade, however, despite this, it takes an average of four years to adopt a child into a foster family.

At a time when dramas about foreign adoptions fill the pages of magazines and newspapers, the uncertain future of these children is a growing scandal that calls for urgent action.

Rethinking Adoption reports that of 39,621 children in foster care in mid-2012, two out of three were in a state of permanent family-to-family transfer for two or more years, with an increasing number of children continually returning to the system . “Thus, children in foster care live in a state of more frequent change and instability, which leads to more complex needs and behaviors.”

“Thus, children in foster care live in a state of more frequent change and instability, which leads to more complex needs and behaviors.”

Becky Hope, in her book All In a Day's Work, cited in the report, emphasizes the critical importance of stable, loving care during the earliest periods of a child's life:

who do not get their basic needs met in reciprocal, loving care, and who are forced to scramble through life on their own, suffer visible devastating effects of brain development even before they are a year old.

It has also been found that children who experience severe lack of parental attention as infants and are placed in long-term foster care before six months of age are able to generally make more progress than if they are adopted after six months.

Children need stability to form secure attachments, but guardianship, no matter how well it is done, is temporary in nature. While there has been an increase in permanent guardianship cases in Australia (and similar instruments elsewhere), a recent study in Queensland found that such arrangements "do not provide enough stability for children". On the one hand, the rights of guardians can be challenged by the family of origin, on the other hand, they do not give children the same sense of belonging to the family, unlike adoption.

On the one hand, the rights of guardians can be challenged by the family of origin, on the other hand, they do not give children the same sense of belonging to the family, unlike adoption.

Gregory Pike, director of the Center for Bioethics and Culture in Adelaide, also comments on this situation in the report “Rethinking Adoption”: adoptions. The cost to society and government of caring for these children and treating the traumatic consequences of their situation is enormous.

Adoption: open and closed

(Ed. With a closed adoption, the adoptive family can keep the fact that the child is not a parent, with an open adoption is not a priority)

In Australia in 2011-12, 95% of local adoptions were open - this is a continuing upward trend that has covered 80% of adoptions since 1998.

Although some adoptions did not really take into account the needs of the birth mothers (fathers were usually not in this picture at all) and the child, in the age of open adoptions, every effort is made to respect the rights and feelings of all participants in the “adoption triangle” . In any case, it is the adoptive parents who now suffer their own stigma for being on a side with a dark history, which has negatively impacted a significant number of people.

In any case, it is the adoptive parents who now suffer their own stigma for being on a side with a dark history, which has negatively impacted a significant number of people.

There is a tendency to exaggerate this influence.

Dr. Pike reviewed local and international reports on adoption outcomes for biological mothers, adopted children and parents, including those who belonged to the "closed" age. The literature provides a much more detailed picture than is evident from media reports of people who have gone through negative or unhappy experiences.

Undoubtedly, some mothers who were forced to give up children suffered, but “a significant amount of uncertainty exists about how common these outcomes were and how they relate to the characteristics of adoption and its process,” Pike says. There is evidence that finding and reuniting with a child has a healing effect.

Looking at the problems of adopted children, he found the following: Although adopted children represent the largest proportion of patients with mental disorders, the actual proportion of "adoptees" in a society with such problems is very small. Foster children face significant challenges in addition to those typically experienced by children in early childhood and adolescence, however, there is evidence that foster children have incredible resilience and there is official evidence of their ability to "catch up" on various occasions. For some adopted children, their experiences prior to adoption were often difficult and sometimes traumatic, and these experiences were associated with later outcomes. When compared with their peers who remained in the shelters, the "adoptees" had better physical and mental health and better circumstances in education and socialization. The key issues for adopted children were attachment, self-determination, search and recovery.

Foster children face significant challenges in addition to those typically experienced by children in early childhood and adolescence, however, there is evidence that foster children have incredible resilience and there is official evidence of their ability to "catch up" on various occasions. For some adopted children, their experiences prior to adoption were often difficult and sometimes traumatic, and these experiences were associated with later outcomes. When compared with their peers who remained in the shelters, the "adoptees" had better physical and mental health and better circumstances in education and socialization. The key issues for adopted children were attachment, self-determination, search and recovery.

Little research has been done on foster parents and their problems.

International adoption

Despite the bad reputation and availability of reproductive technology, it appears that many couples would be happy to adopt a child if given the option. Frustrated by the barriers to adoption in Australia, they often turn to orphanages in developing countries. Here again they have to wait up to five years.

Frustrated by the barriers to adoption in Australia, they often turn to orphanages in developing countries. Here again they have to wait up to five years.

Obviously, special care must be taken to ensure that the adoption of a child in another country and culture serves his best interests. Pike says: “In the case of all adoptions, and according to the Hague Convention on Adoption, cross-country adoption should be used only in cases where the biological parents (parent) or relatives do not have the ability or desire to properly care for the child. Only if there are no suitable facilities available to provide ongoing care in the State where the child was born, should ethical inter-country adoption be considered in the best interests of the child.”

Tony Abbot's government in Australia has taken steps to expedite these adoptions by creating a new national agency that will be operational by mid-2015 to negotiate adoptions with most countries.

However, each country has its own special obligations to its children, and those under the care of the state deserve a new plan. Barnados Australia, a leading non-governmental agency for the protection of child survivors of abuse, urges Abbott to set a goal for open adoptions in every state.

Barnados Australia, a leading non-governmental agency for the protection of child survivors of abuse, urges Abbott to set a goal for open adoptions in every state.

So why delay?

According to a report by Martin Nary, UK Government Adoption Adviser, important factors include: take him to meetings with his parent or parents while the court decides the future of the child. This represents a shocking mistake with devastating consequences for children and society that will last for decades."

- Parents are given priority: the needs of the parents, not the rights of the children, are the priority.

-Loss of sense of urgency when a child is placed in care.

-Social workers: the need for a balance of social workers who have maturity (not necessarily skill level) and experience in the care and development of children and young workers who may be qualified. Everyone needs to be trained in a real child protection situation and taught to understand the priorities of the child, the need to act immediately, and so on.

Pike also noted that ideology plays a key role: there are a number of references in Australian sources to an anti-adoptive mentality in some educational institutions "and perhaps among professionals who are key intermediaries", such as employees of government welfare departments. A 2005 government report on foreign adoption noted that attitudes in these departments ranged from "indifference to hostility".

Feminist ideas about patriarchy and its "dominant prescriptions" are also included. Combined with revelations about previous scandals and forced adoptions, this has shaped public opinion that children should not be separated from their parents.

This is basically a reasonable principle: the child must be with the parents and reasonable steps must be taken to ensure that they can stay together. However, when a child is neglected or abused, despite the help of relatives and the intervention of the authorities, there must come a time when the best interests of the child dictate the need for his removal from the family.