Treatment for retained placenta

The Retained Placenta - PMC

1. Combs CA, Laros RK. Prolonged third stage of labour: morbidity and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:863–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Gordon JE, Gideon H, Wyon JB. Midwifery practices in rural Punjab, India. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1965;93:734–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Tandberg A, Albrechtsen S, Iverson DE. Manual removal of placenta. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Why Mothers Die. Report of the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths 1994–1996. London: The Stationary Office; 1998. Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths. [Google Scholar]

5. Harrison KA. Childbearing, health and social priorities: survey of 22,774 consecutive hospital births in Zaria, Northern Nigeria. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985;92(supp 5):100–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Brandt ML. The mechanism and management of the third stage of labour. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1933;25:662–667. [Google Scholar]

7. Herman A, Weinraub Z, Bukovsky I, et al. Dynamic ultrasonographic imaging of the third stage of labor: new perspectives into third stage mechanism. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:1496–1499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Deyer TW, Ashton-Miller JA, Van Baren PM, Pearlman MD. Myometrial contractile strain at uteroplacental separation during parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:156–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Krapp M, Baschat AA, Hankeln M, Gembruch U. Gray scale and color Doppler sonography in the third stage of labor for early detection of failed placental separation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;15:138–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Enkin MW, Wilkinson C. The Cochrane Library, Issue 3. Oxford: Update Software; 1999. Manual removal of placenta at caesarean section (Cochrane Review) [Google Scholar]

11. Weeks AD. The role of the placenta in dysfunctional labour. Transac N Eng Obstet Gynaecol Sac. (in press) [Google Scholar]

12. Romero R, Hsu YC, Athanassiadis AP, et al. Preterm delivery: a risk factor for retained placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:823–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Preterm delivery: a risk factor for retained placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:823–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Lye SJ, Ou C-W, Teoh T-G, et al. The molecular basis of labour and tocolysis. Fetal Mat Med Rev. 1998;10:121–136. [Google Scholar]

14. Weeks AD, Stewart P. The use of low dose mifepristone and vaginal misoprostol for first trimester termination of pregnancy. Br J Fam Plan. 1995;21:85–86. [Google Scholar]

15. Weeks AD, Stewart P. The use of mifepristone in combination with misoprostol for second trimester termination of pregnancy. Br J Fam Plan. 1995;21:43–44. [Google Scholar]

16. Hofmeyr GJ, Gulmezoglu AM. The Cochrane Library, Issue 1. Oxford: Update Software; 2000. Vaginal misoprostol for cervical ripening and labour induction in late pregnancy (Cochrane Review) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Schellenberg J-C, Liggins GC. Initiation of labour: uterine and cervical changes, endocrine changes. In: Chard T, Grudzinskas JG, editors. The Uterus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

18. Thornton S, Terzidou V, Clark A, Blanks A. Progesterone metabolite and spontaneous myometrial contractions in vitro. Lancet. 1999;353:1327–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Ledingham M-A, Thompson AJ, Greer IA, Norman JE. Nitric oxide in parturition. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;107:581–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Ramsay B, Sooranna SR, Johnson MR. Nitric oxide synthase activities in human myometrium and villous trophoblast throughout pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:249–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Thompson A, Telfer JF, Kohnen G, et al. Nitric oxide synthase activity and localisation do not change in uterus and placenta during human parturition. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:2546–2552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Sladek SM, Magness RR, Conrad KP. Nitric oxide and pregnancy. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:R441–R463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Carroll G, Belizan JM, Grant A, Gonzalez L, Campodonico L, Bergel E Grupo Argentino de Estudio de Placenta Retenida, author. Intra-umbilical vein injection and retained placenta: evidence from a collaborative large randomised controlled trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:179–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Intra-umbilical vein injection and retained placenta: evidence from a collaborative large randomised controlled trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:179–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Reyes FI, Winter JSD, Falman C. Postpartum disappearance of chorionic gonadotrophin from the maternal and neonatal circulations. Am J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985;153:486–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Johanson RB. Mechanism and management of placental non-separation. In: Kingdom J, Jauniaux E, O'Brien S, editors. The Placenta: Basic Science and Clinical Practice. London: RCOG Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

26. Dunstone SJ, Leibowitz CB. Conservative management of placenta praevia with a high risk of placenta accreta. Aus N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;38:429–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Arulkumaran S, Ng CSA, Ingemarsson I, Ratnam SS. Medical treatment of placenta accreta with methotrexate. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1986;65:285–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Prendiville WJ, Elbourne D, McDonald S. The Cochrane Library, Issue 3. Oxford: Update Software; 1998. Active versus expectant management of the third stage of labour (Cochrane Review) [Google Scholar]

The Cochrane Library, Issue 3. Oxford: Update Software; 1998. Active versus expectant management of the third stage of labour (Cochrane Review) [Google Scholar]

29. Bagley CM. A comparison of ‘active’ and ‘physiological’ management of the third stage of labour. Midwifery. 1990;6:3–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Donald I. Donald I. Practical Obstetric Problems. London: Lloyd-Luke Ltd; 1976. Postpartum Haemorrhage. [Google Scholar]

31. McDonald S. Physiology and management of the third stage of labour. In: Bennett VR, Brown LK, editors. Myles Textbook for Midwives. 13th edition. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. [Google Scholar]

32. Danielsson KG, Marions L, Rodriguez A, Spur BW, Wong PYK, Bygdeman M. Comparison between oral and vaginal administration of misoprostol on uterine contractility. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:275–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Ng PS, Chan ASM, Sin WK, Tang LCH, Cheung KB, Yeun PM. A multicentre randomized controlled trial of oral misoprostol and i. m. syntometrine in the management of the third stage of labour. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

m. syntometrine in the management of the third stage of labour. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Carroll G, Bergel E. The Cochrane Library, Issue 4. Oxford: Update Software; 2000. Umbilical vein injection for management of retained placenta (Cochrane Review) [Google Scholar]

35. Pipingas A, Hofmeyr GJ, Sesel KR. Umbilical vessel oxytocin administration for retained placenta: in-vitro study of various infusion techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:793–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Wilken-Jensen C, Strom V, Nielsen MD, Rosenkilde-Gram B. Removing placenta by oxytocin - a controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:155–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Hendricks CH, Brenner WE. Cardiovascular effects of oxytocic drugs used post partum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1970;108:751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Patient C, Davison JM, Charlton L, Baylis PH, Thornton S. The effect of labour and maternal oxytocin infusion on fetal plasma oxytocin concentration. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;106:1311–1313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;106:1311–1313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Huber MGP, Wildschut HIJ, Boer K, Kleiverda G, Hoek FJ. Umbilical vein administration of oxytocin for the mangement of retained placenta: It is effective? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:1216–1219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Kristiansen FV, Frost L, Kaspersen P, Moller BR. The effect of oxytocin injection into the umbilical vein for the management of retained placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156:979–980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Thiery M. The Cochrane Library, Issue 4. Oxford: Update Software; 2000. Management of retained placenta with oxytocin injection into the umbilical vein. Personal communication quoted in: Carroll G, Bergel E. (2000) Umbilical vein injection for management of retained placenta (Cochrane Review) [Google Scholar]

42. Calderale L, Dalle NF, Franzol R, Vitalini R. Eutile la somministrazione di ossitocina nella vena ombilicale per il tritamento della placenta ritenuta? G Ital Ostet Ginecol. 1994;16(5):283–286. [Google Scholar]

1994;16(5):283–286. [Google Scholar]

43. Frappell JM, Pearce JM, McParland P. Intra-umbilical vein oxytocin in the management of retained placenta: a random, prospective, double blind, placebo controlled study. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;8:322–424. [Google Scholar]

44. Hansen P, Jorgensen L, Dueholm M, Hansen S. Intraumbilical oxytocin in the treatment of retained placenta. Ugeskr Laeger. 1987;149:3318–3319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Selinger M, Mackenzie IZ, Dunlop P, James D. Intra-umbilical vein oxytocin in the management of retained placenta. A double blind placebo controlled study. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1986;7:115–117. [Google Scholar]

46. Gazvani MR, Luckas MJM, Drakeley AJ, Emery SJ, Alfirevic Z, Walkinshaw SA. Intraumbilical oxytocin for the management of retained placenta: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:203–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Bider D, Dulitzky M, Goldenberg M, Lipitz S, Mashlach S. Intraumbilical vein injection of prostaglandin F2alpha in retained placenta. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;64:59–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;64:59–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Chauhan P. Volume and site of injection of oxytocin solution is important in the medical treatment of retained placenta. Int J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;70:83. [Google Scholar]

Retained placenta: will medical treatment ever be possible?

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016 Apr 14; 95(5): 501–504.

Published online 2016 Feb 4. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12848

1 and 1

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

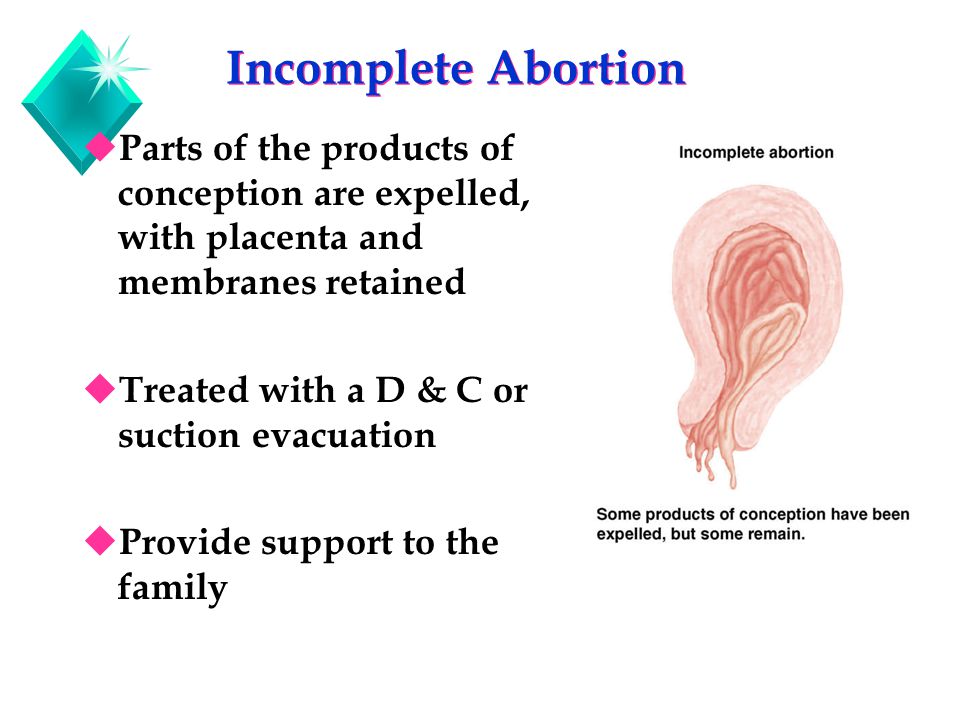

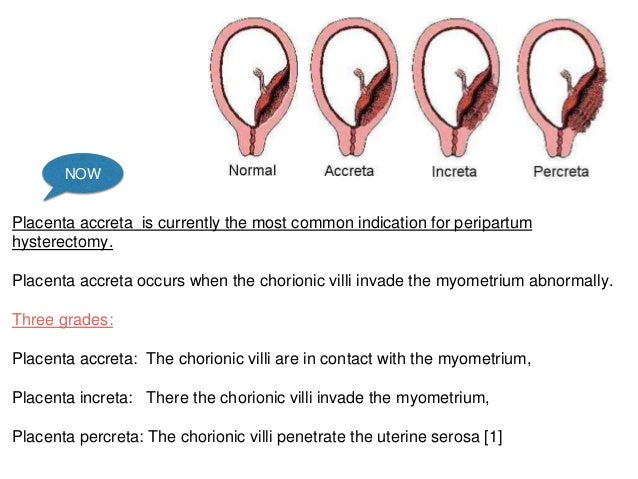

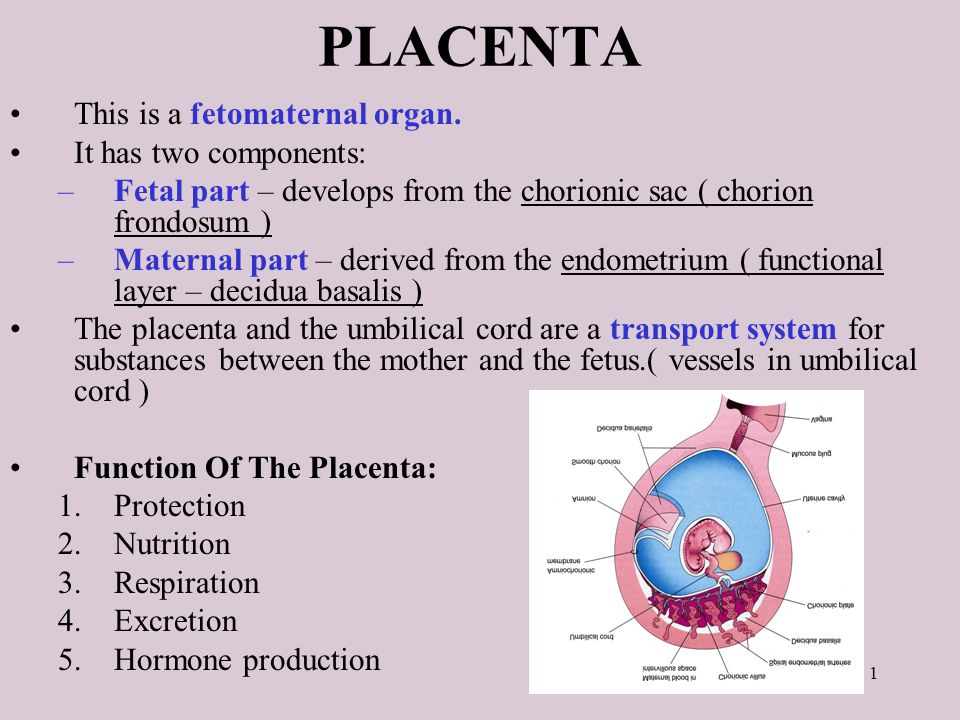

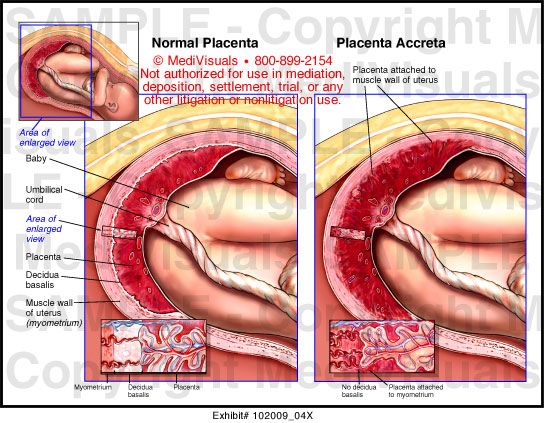

The standard treatment for retained placenta is manual removal whatever its subtype (adherens, trapped or partial accreta). Although medical treatment should reduce the risk of anesthetic and surgical complications, they have not been found to be effective. This may be due to the contrasting uterotonic needs of the different underlying pathologies. In placenta adherens, oxytocics have been used to contract the retro‐placental myometrium. However, if injected locally through the umbilical vein, they bypass the myometrium and perfuse directly into the venous system. Intravenous injection is an alternative but exacerbates a trapped placenta. Conversely, for trapped placentas, a relaxant could help by resolving cervical constriction, but would worsen the situation for placenta adherens. This confusion over medical treatment will continue unless we can find a way to diagnose the underlying pathology. This will allow us to stop treating the retained placenta as a single entity and to deliver targeted treatments.

However, if injected locally through the umbilical vein, they bypass the myometrium and perfuse directly into the venous system. Intravenous injection is an alternative but exacerbates a trapped placenta. Conversely, for trapped placentas, a relaxant could help by resolving cervical constriction, but would worsen the situation for placenta adherens. This confusion over medical treatment will continue unless we can find a way to diagnose the underlying pathology. This will allow us to stop treating the retained placenta as a single entity and to deliver targeted treatments.

Keywords: Retained placenta, medical treatment, way through medical treatment, delivery, postpartum hemorrhage

Abbreviation

- RP

- retained placenta

Key Message

We need to stratify treatment of retained placenta according to underlying cause.

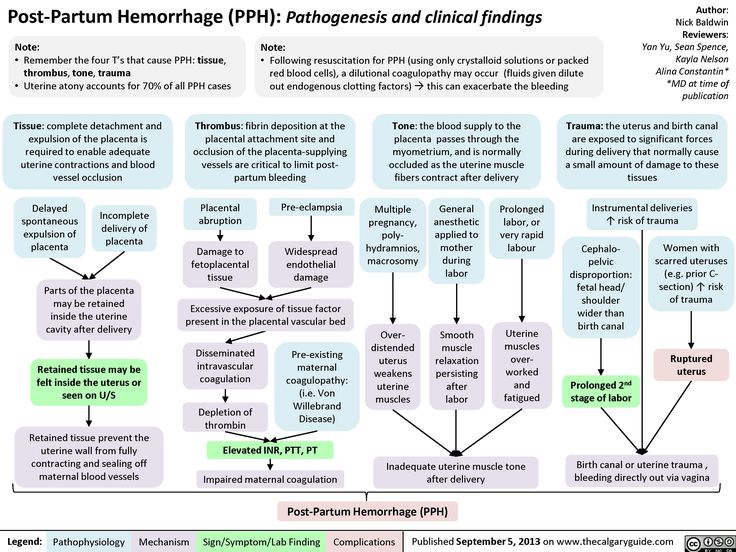

Obstetric hemorrhage remains a leading cause of maternal death worldwide 1 and retained placenta (RP) is a significant contributor 2. The incidence appears to be related to intrapartum intervention, as rates increase with both time and health system development 3. The rate currently in Europe is around 2–3%. If RP is not treated, it may lead to maternal death due to postpartum hemorrhage or sepsis. Historically, in the UK, RP led to the deaths of around seven women per 100 000 births 4, and in modern African settings, with delayed access for manual removal, the case fatality rate remains around 1% 5. It is clear, however, that many RPs will spontaneously deliver with time. Indeed, in the placebo arm of the largest randomized trial to date, 38% delivered spontaneously in the hour following recruitment, with 10% having blood loss of >1000 mL 6. Thus, there is a careful risk–benefit balance between waiting, which allows more spontaneous deliveries, and intervening to prevent blood loss and sepsis. It has been suggested that when considering PPH, the optimal time for manual removal is 18 min 7 but this does not take into consideration the adverse medical, neonatal or psychological effects of manual removal of placenta.

The incidence appears to be related to intrapartum intervention, as rates increase with both time and health system development 3. The rate currently in Europe is around 2–3%. If RP is not treated, it may lead to maternal death due to postpartum hemorrhage or sepsis. Historically, in the UK, RP led to the deaths of around seven women per 100 000 births 4, and in modern African settings, with delayed access for manual removal, the case fatality rate remains around 1% 5. It is clear, however, that many RPs will spontaneously deliver with time. Indeed, in the placebo arm of the largest randomized trial to date, 38% delivered spontaneously in the hour following recruitment, with 10% having blood loss of >1000 mL 6. Thus, there is a careful risk–benefit balance between waiting, which allows more spontaneous deliveries, and intervening to prevent blood loss and sepsis. It has been suggested that when considering PPH, the optimal time for manual removal is 18 min 7 but this does not take into consideration the adverse medical, neonatal or psychological effects of manual removal of placenta.

Herman et al. first documented the ultrasound findings in the normal third stage of labor and placenta adherens 8 and went on to describe the use of ultrasound for the diagnosis of the three known subtypes: placenta adherens, partial accreta and trapped placenta 9. However, following this description there has been no formal analysis of the utility of ultrasound in RP.

Currently, the standard treatment of RP is manual removal whatever the subtype, even though this has anesthetic and surgical risks. While treating RP with drugs would remove many of these risks, medical therapies have not been well investigated, partly because of a current inability to distinguish rapidly and accurately the various forms of RP on the labor ward. The use of medical therapies to treat RP, irrespective of the underlying subtype, has led to confusion.

Umbilical vein injection of oxytocin

Following the hypothesis that the pathogenesis of the RP adherens is due to the failure of contraction of the retro‐placental myometrium 8, umbilical vein injection (UVI) of oxytocics to counteract that inhibition seems to be a plausible remedy. However, conflicting advice on the use of UVI oxytocin to treat the RP has been issued by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) group in the UK. They recommended its use in 2007 because of Cochrane Reviews that showed that it was associated with significantly fewer manual removals when compared with UVI saline 10. Now, NICE has changed its advice and no longer recommends the use of UVI oxytocin, following a cost analysis and a finding that it tends to be associated with severe postpartum hemorrhage despite being an oxytocic 11. This is in keeping with other large controlled trials, including the Release Trial 6, that evaluated UVI oxytocin and demonstrated lack of significant overall benefit. Likewise, the administration of intravenous oxytocic agents to deliver an RP is not recommended unless the woman is bleeding excessively, although there is no conclusive evidence on this.

However, conflicting advice on the use of UVI oxytocin to treat the RP has been issued by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) group in the UK. They recommended its use in 2007 because of Cochrane Reviews that showed that it was associated with significantly fewer manual removals when compared with UVI saline 10. Now, NICE has changed its advice and no longer recommends the use of UVI oxytocin, following a cost analysis and a finding that it tends to be associated with severe postpartum hemorrhage despite being an oxytocic 11. This is in keeping with other large controlled trials, including the Release Trial 6, that evaluated UVI oxytocin and demonstrated lack of significant overall benefit. Likewise, the administration of intravenous oxytocic agents to deliver an RP is not recommended unless the woman is bleeding excessively, although there is no conclusive evidence on this.

UVI prostaglandins

There is also frustration with the use of other UVI agents. Meta‐analysis has demonstrated a significant reduction in the need for manual removal of the placenta (MROP) following UVI prostaglandin when compared with UVI oxytocin 10. Randomized controlled trials also showed that intravenous infusion of sulprostone also reduced the need for MROP when compared with placebo 12. However, there are only a few of these trials, with small sample sizes, and their effects were inconsistent or statistically insignificant. Therefore, UVI prostaglandins are currently not recommended.

Meta‐analysis has demonstrated a significant reduction in the need for manual removal of the placenta (MROP) following UVI prostaglandin when compared with UVI oxytocin 10. Randomized controlled trials also showed that intravenous infusion of sulprostone also reduced the need for MROP when compared with placebo 12. However, there are only a few of these trials, with small sample sizes, and their effects were inconsistent or statistically insignificant. Therefore, UVI prostaglandins are currently not recommended.

Nitroglycerin

The use of nitroglycerin for the trapped placenta is also clouded with uncertainty. One trial showed sublingual nitroglycerin to be associated with a significant reduction in manual removal of the placenta, when compared with placebo 13. However, this trial involved only 24 women and a subsequent larger study by the same team showed no significant benefit 14. Another small trial of intravenous nitroglycerin also demonstrated no benefit 15. We await with interest the outcome of the UK‐wide randomized controlled trial on the use of glycerin trinitrate for RP (GOT‐IT Trial).

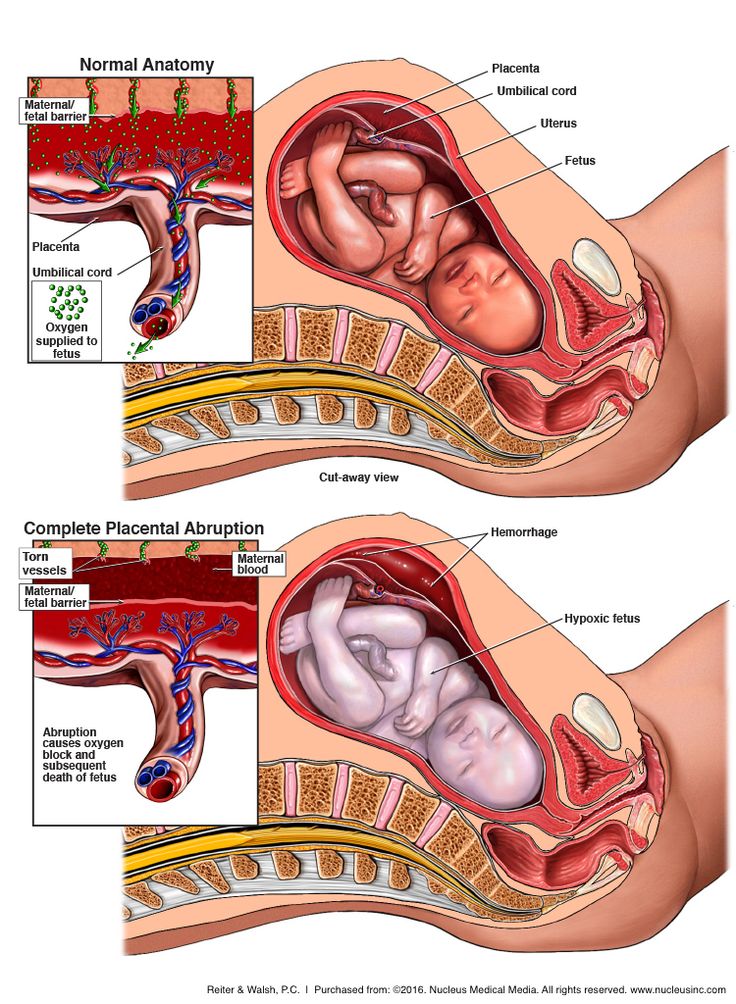

It is likely that the various medical treatments for RP do not work for a number of reasons. The first reason is the lack of accurate diagnosis of the RP subtypes. Although RP is a group of pathologies, it has a common presentation and has been therefore treated as a single entity. It is important to get the type of RP right before prescribing uterotonics instead of relaxants. For, although uterotonics like oxytocin can treat placenta adherens by contracting the retro‐placental myometrium, they are likely to exacerbate trapped placenta by increasing cervical constriction. In contrast, relaxants can counteract uterine or cervical constriction to deliver a trapped placenta, but they would worsen placenta adherens and possibly precipitate hemorrhage by increasing uterine relaxation. Neither uterotonics nor relaxants can treat a partial accreta, but continuous cord traction on an accreta, following a false impression that a medication administered might help, could also lead to severe hemorrhage or uterine inversion.

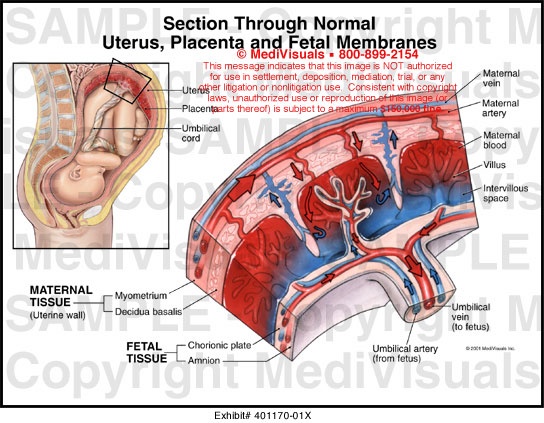

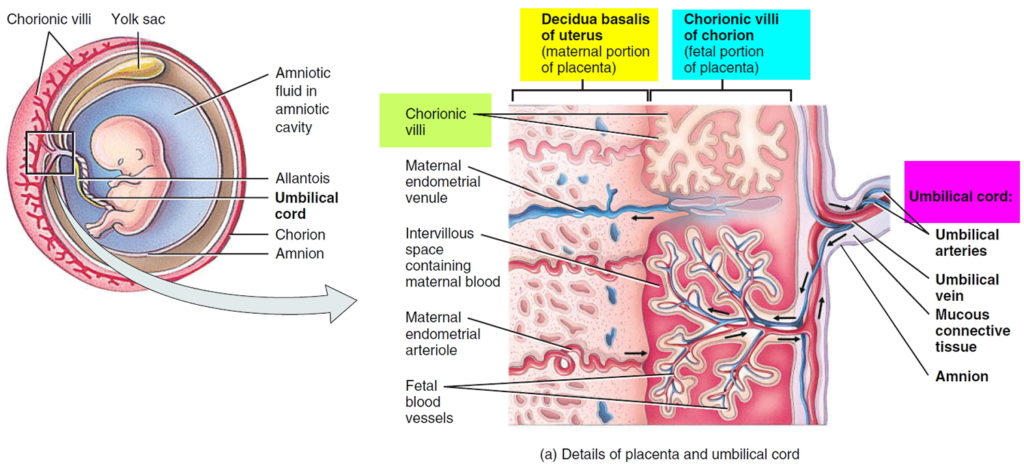

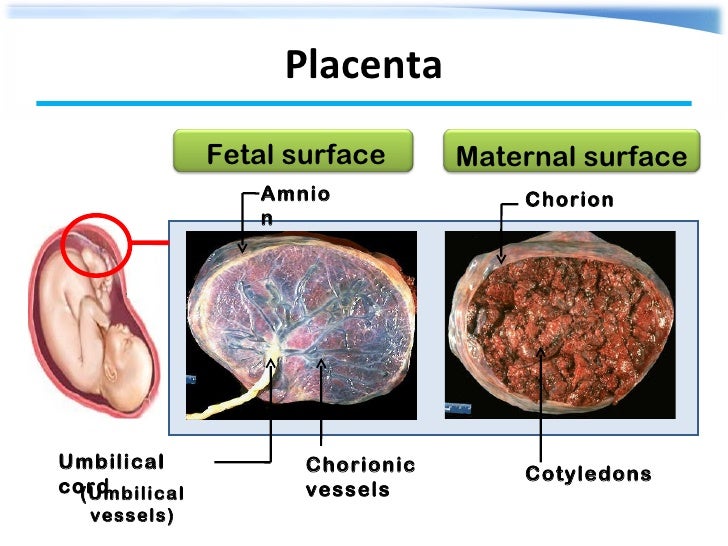

The second reason may be that UVI agents probably go to the wrong place. After passing up the umbilical vein they perfuse through the placenta villi into the radial veins in the uterus without reaching the retro‐placental myometrium. It is only on the second pass around the body that they reach the myometrial capillaries and initiate the desired myometrial contraction. By this stage the concentration is likely to be very low and no longer directed at just the retroplacental myometrium (see Figure ).

Open in a separate window

Blood flow from umbilical veins to fetal capillaries.

Effective medical therapy for RP should avoid the surgical and anesthetic risks associated with the current standard treatment of manual removal. However, it can only be made to work if the reasons for its failure are adequately addressed. UVI may not directly enter the myometrial capillary bed and alternative forms of directed treatment, possibly using nanoparticles, may provide a better way of delivering oxytocics to the retro‐placental myometrium. But the main problem is our inability to differentiate between the various pathologies underlying RP, each of which has a different, and conflicting, treatment requirement. The confusion over medical treatment will continue unless we stop treating the RP as a single entity and start tailoring the treatment to the underlying pathology. This will take an effective way of diagnosing the type – probably using a mixture of uterine ultrasound and Doppler of the uterine vessels. Until then, the medical treatment of RP is likely to continue to elude us.

But the main problem is our inability to differentiate between the various pathologies underlying RP, each of which has a different, and conflicting, treatment requirement. The confusion over medical treatment will continue unless we stop treating the RP as a single entity and start tailoring the treatment to the underlying pathology. This will take an effective way of diagnosing the type – probably using a mixture of uterine ultrasound and Doppler of the uterine vessels. Until then, the medical treatment of RP is likely to continue to elude us.

No specific funding.

Akol AD, Weeks AD. Retained placenta: will medical treatment ever be possible? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2016; 95:501–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Conflict of interest

The authors have stated explicitly that there are no conflicts of interest in connection with this article.

1. Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tunçalp Ö, Moller A‐B, Daniels J, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e323–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e323–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Moodley J, Pattinson RC, Fawcus S, Schoon MG, Moran N, Shweni PM. The confidential enquiry into maternal deaths in South Africa: a case study. BJOG. 2014;121(Suppl 4):53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Cheung WM, Hawkes A, Ibish S, Weeks AD. The retained placenta: historical and geographical rate variations. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;31:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Kerr RS, Weeks AD. Lessons from 150 years of UK maternal hemorrhage deaths. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94:664–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. John CO, Orazulike N, Alegbeleye J. An appraisal of retained placenta at the university of port harcourt teaching hospital: a five‐year review. Niger J Med. 2015;24:99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Weeks AD, Alia G, Vernon G, Namayanja A, Gosakan R, Majeed T, et al. Umbilical vein oxytocin for the treatment of retained placenta (Release Study): a double‐blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:141–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lancet. 2010;375:141–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Magann EF, Evans S, Chauhan SP, Lanneau G, Fisk AD, Morrison JC. The length of the third stage of labor and the risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:290–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Herman A, Weinraub Z, Bukovsky I, Arieli S, Zabow P, Caspi E, et al. Dynamic ultrasonographic imaging of the third stage of labor: new perspectives into third‐stage mechanisms. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:1496–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Herman A. Complicated third stage of labor: time to switch on the scanner. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;15:89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Nardin JM, Weeks A, Carroli G. Umbilical vein injection for management of retained placenta. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;5:CD001337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, Intrapartum care: care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth. NICE clinical guideline 190 [press release]. London: RCOG Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

London: RCOG Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

12. van Beekhuizen HJ, de Groot AN, De Boo T, Burger D, Jansen N, Lotgering FK. Sulprostone reduces the need for the manual removal of the placenta in patients with retained placenta: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:446–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Bullarbo M, Tjugum J, Ekerhovd E. Sublingual nitroglycerin for management of retained placenta. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;91:228–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Bullarbo M, Bokstrom H, Lilja H, Almstrom E, Lassenius N, Hansson A, et al. Nitroglycerin for management of retained placenta: a multicenter study. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:321207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Visalyaputra S, Prechapanich J, Suwanvichai S, Yimyam S, Permpolprasert L, Suksopee P. Intravenous nitroglycerin for controlled cord traction in the management of retained placenta. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;112:103–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

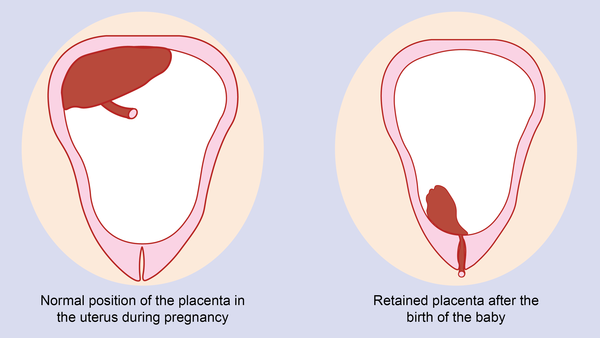

Delayed placenta separation - causes, symptoms, diagnosis and treatment

Delayed placenta separation is a complication of the third stage of labor, a condition in which the placenta does not fully or partially exfoliate from the uterine walls. Clinically, it can be manifested by pathological bleeding or the absence of bloody discharge normal for this period, soreness, or the absence of attempts. In this case, the standing of the bottom of the uterus corresponds to the period after the expulsion of the fetus, the connection of the umbilical cord with the uterus is indirectly determined. The diagnosis is established on the basis of the results of a physical examination, ultrasound. Most often, manual separation of the placenta or surgical treatment is performed. nine0005

Clinically, it can be manifested by pathological bleeding or the absence of bloody discharge normal for this period, soreness, or the absence of attempts. In this case, the standing of the bottom of the uterus corresponds to the period after the expulsion of the fetus, the connection of the umbilical cord with the uterus is indirectly determined. The diagnosis is established on the basis of the results of a physical examination, ultrasound. Most often, manual separation of the placenta or surgical treatment is performed. nine0005

General

According to the WHO definition, retained placenta is diagnosed if separation does not occur within half an hour after the end of the second stage of labour. The incidence of pathology is 0.8-1.2% of all births. This complication is more often recorded in multiparous, especially those with a history of caesarean section. The disease is a serious problem of modern obstetrics, as it is often accompanied by postpartum hemorrhage. Bleeding is the cause of maternal death in a quarter of cases, 30% of which are the result of delayed separation of the placenta. nine0005

Bleeding is the cause of maternal death in a quarter of cases, 30% of which are the result of delayed separation of the placenta. nine0005

Delayed separation of the placenta

Causes

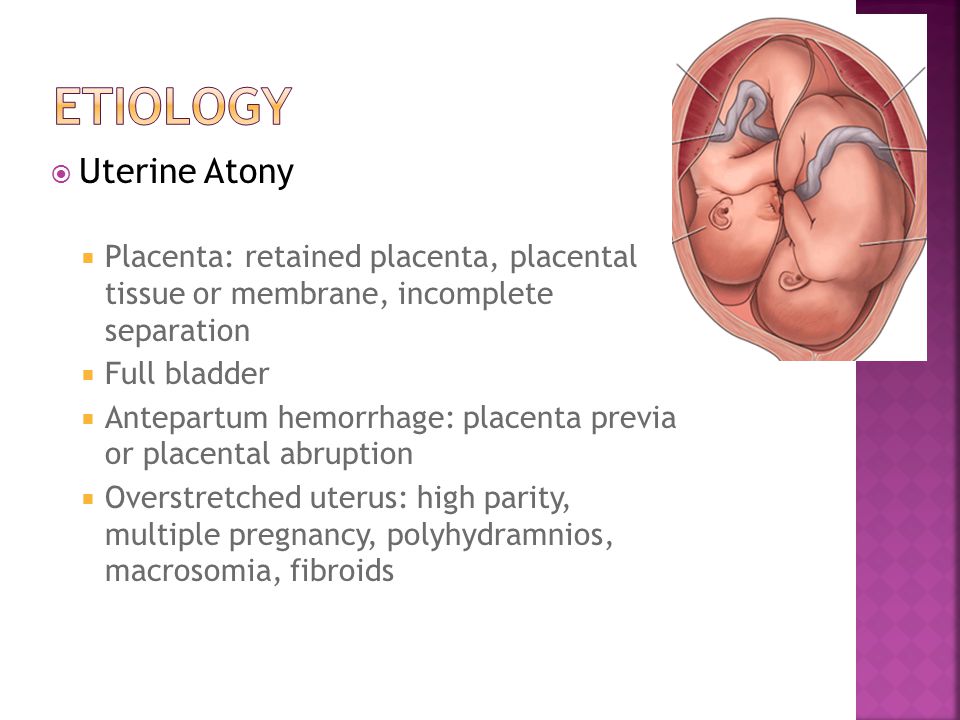

The etiology of delayed separation of the placenta has not been fully understood. Violations of detachment of the placenta and its parts in the afterbirth period, on the one hand, may be due to defects in uterine contractile activity, on the other hand, due to excessively tight attachment of the child's place. Most women in labor fail to detect any visible disorders. The main causes of pathology include:

- Hypotension of the uterus. nine0004 Weak contractions of the uterine muscles are not enough to start the process of separation of the placenta, even if the placenta does not have specific features that prevent detachment. In the presence of predisposing conditions, a slight decrease in contractile function can become a trigger for the development of pathology.

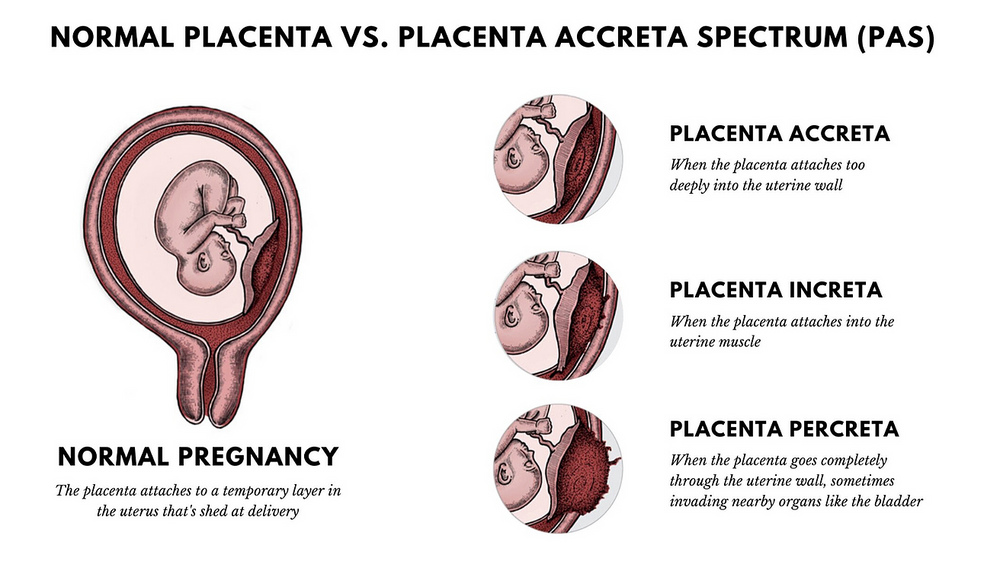

- Tight attachment of the placenta. Due to the depletion of the basal layer of the decidua and is characterized by a stronger than normal connection with the uterine walls without the germination of the chorionic villi into the myometrium. With the pathology under consideration, the force of uterine contractions is not enough to completely separate the placenta, which leads to bleeding. nine0020

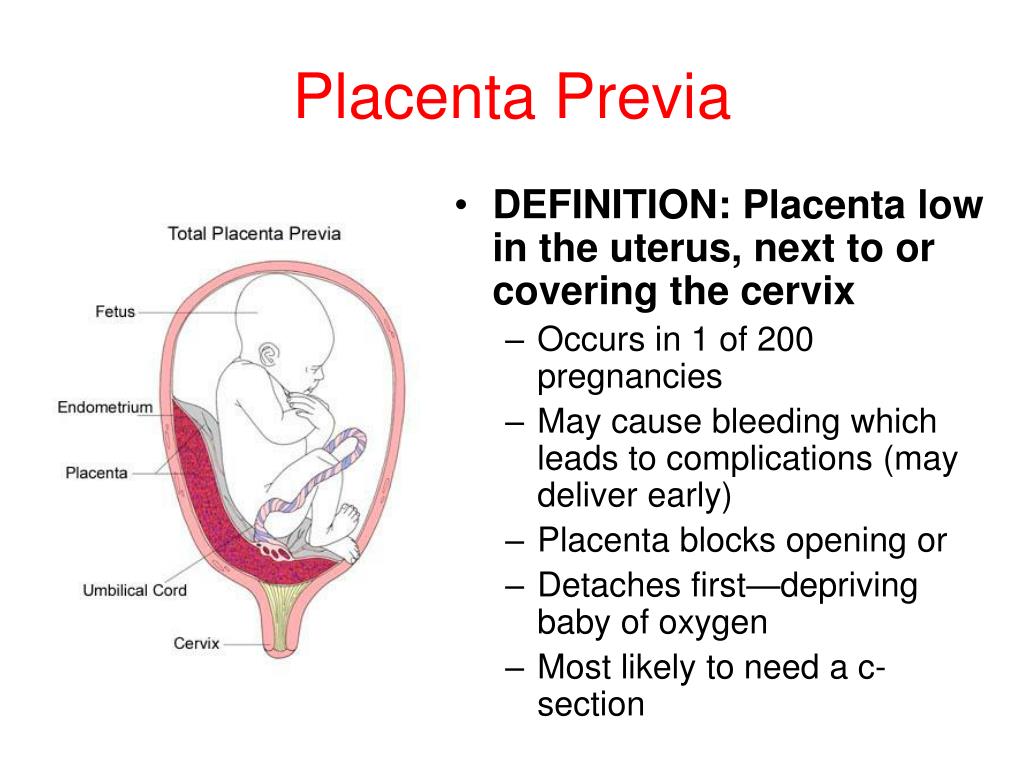

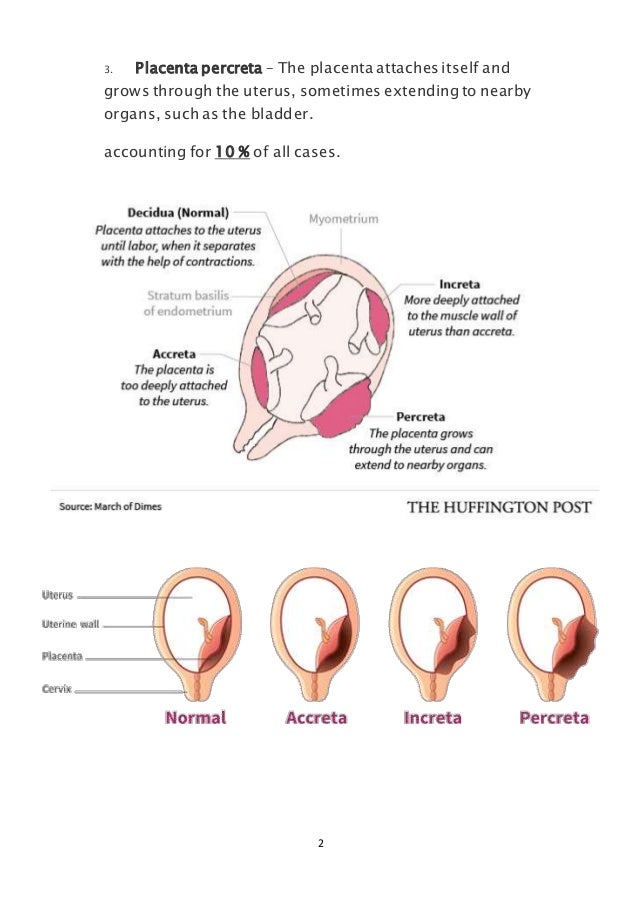

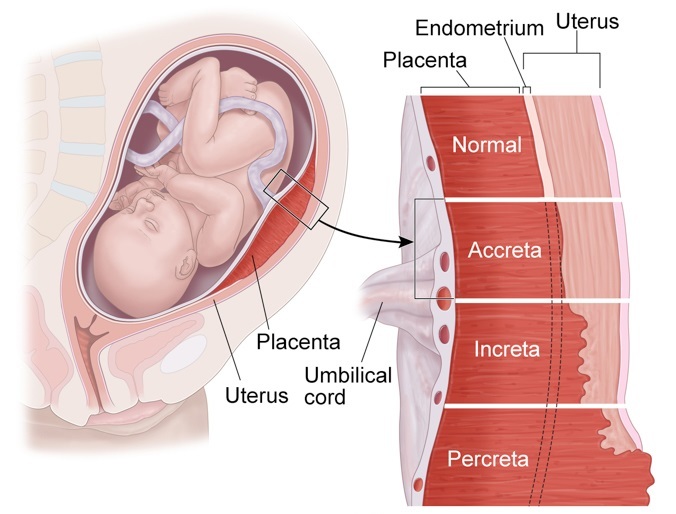

- True placental accreta. Also associated with underdevelopment of the basal layer, however, in this case, there is invasion of the villi into the muscle tissue, and in rare cases, the serosa of the uterus. More common with placenta previa. Spontaneous detachment of the adherent child's place is impossible, manual separation can lead to perforation of the uterine wall.

- Anomalies in the development of the placenta. Delayed detachment is often observed with developmental anomalies (lobed, two- and three-lobed or with additional lobules) of the placenta.

The separation of the afterbirth is difficult with the so-called "membraneous" placenta, which is characterized by a slight thickness and a large attachment area, often extending to the entire uterine wall. nine0020

The separation of the afterbirth is difficult with the so-called "membraneous" placenta, which is characterized by a slight thickness and a large attachment area, often extending to the entire uterine wall. nine0020

The most significant risk factors are the endometritis transferred before the onset of pregnancy, obstetric history (surgery on the uterus, abortions, multiple births), indicating traumatic injuries. Inflammation and trauma lead to anatomical and histological changes in the uterus, which negatively affects placentogenesis and myometrial tone. Predisposing conditions include hyperandrogenism, malformations of the uterus (bicornuate uterus, intrauterine septum), volumetric formations (myoma, nodular adenomyosis). nine0005

Pathogenesis

Normally, after the birth of the fetus, afterbirth contractions appear, in which contractions spread to the entire uterus, including the placental site (previously, the muscles of this zone did not function). Labor activity leads to detachment of the child's place in the area of the spongy layer of the mucosa (with the preservation of the basal layer), and then to its exit to the outside. The separation of the placenta is accompanied by damage to blood vessels, physiological bleeding. After his birth, the uterus contracts, which helps to stop the bleeding. nine0005

Labor activity leads to detachment of the child's place in the area of the spongy layer of the mucosa (with the preservation of the basal layer), and then to its exit to the outside. The separation of the placenta is accompanied by damage to blood vessels, physiological bleeding. After his birth, the uterus contracts, which helps to stop the bleeding. nine0005

In the presence of unfavorable factors and predisposing conditions, detachment is difficult. With partial detachment, if the process started, but for some reason stopped, the gaping vessels of the uncontracted uterus become a source of pathological blood loss. Ingrown chorionic villi deep into the myometrium lead to thinning of the uterine wall, so an attempt to manually separate the placenta quickly ends in trauma, accompanied by intense bleeding.

Symptoms

Subjective signs of delayed separation of the placenta include prolonged, painful, ineffective attempts after the birth of a child or their complete absence. An objective sign is intense bleeding observed with partial separation. If detachment of the placenta does not occur at all, even in a partial volume (for example, with a complete increment), bloody discharge from the birth canal may be absent.

An objective sign is intense bleeding observed with partial separation. If detachment of the placenta does not occur at all, even in a partial volume (for example, with a complete increment), bloody discharge from the birth canal may be absent.

Complications

The most common complication of delayed separation of the placenta is bleeding. Significant blood loss leads to such a potentially fatal complication as hemorrhagic shock, accompanied by multiple organ failure. Massive bleeding often develops when professional medical care is not provided in time (the risk increases sharply during childbirth outside a medical institution). nine0005

Other frequent complications of this pathology include purulent-inflammatory diseases (postpartum endometritis, pelvioperitonitis, obstetric sepsis), which can be the result of both surgical treatment and retention of placenta fragments in the uterine cavity. In addition, the remaining ingrown placenta can become a source of late postpartum hemorrhage, uterine rupture during a subsequent pregnancy.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of retained placenta is made by the obstetrician if there is no discharge of the placenta within thirty minutes after the birth of the infant with appropriate results of the physical examination. To establish the causes of the pathological condition (which determines the choice of treatment tactics), an ultrasound examination is additionally used. nine0005

- Clinical examination. Signs of delayed separation of the placenta are determined by the shape and location of the uterus, the mobility of the umbilical cord. If separation has not occurred, the uterus is rounded, the bottom is located at the navel (Schroeder's sign), the outer segment of the umbilical cord does not lengthen (Alfeld's sign). The umbilical cord retracts with pressure over the womb (Kyustner-Chukalov's sign), after inhalation (Dovzhenko's sign), straining (Klein's sign).

- Ultrasonography. nine0004 Ultrasound of the uterus is prescribed for the diagnosis of placenta accreta.

Ultrasound signs of this pathology include deformation of the internal contour of the uterine cavity, its uneven expansion, and the absence of a hypoechoic layer between the myometrium and the placenta. Ultrasound angiography reveals hypervascularization of the anterior wall, chaotic branching of vessels.

Ultrasound signs of this pathology include deformation of the internal contour of the uterine cavity, its uneven expansion, and the absence of a hypoechoic layer between the myometrium and the placenta. Ultrasound angiography reveals hypervascularization of the anterior wall, chaotic branching of vessels.

If the placenta is retained, the volume of blood lost is estimated (abnormal blood loss is more than 400-500 ml). If a surgical operation is necessary, a coagulogram and a clinical blood test are examined. Differential diagnosis is carried out with a delay in the birth of the separated placenta, primarily with its infringement due to uneven or spastic contractions of the myometrium. nine0005

Treatment of delayed separation of the placenta

Conservative therapy

Therapeutic measures to promote the separation of the placenta are carried out only in the absence of pathological bleeding, and can last for 20-30 minutes. With the ineffectiveness of conservative treatment, surgical methods are used; in case of pathological blood loss, replacement blood transfusion is performed. Therapy is aimed at strengthening uterine contractions and includes:

With the ineffectiveness of conservative treatment, surgical methods are used; in case of pathological blood loss, replacement blood transfusion is performed. Therapy is aimed at strengthening uterine contractions and includes:

- Bladder catheterization. Since the muscular layer of the bladder is closely connected with the nerve fibers of the uterine muscles, irritation of the urothelial receptors leads to a reflex contraction of the myometrium. Catheterization normalizes the course of the afterbirth period of childbirth, contributes to the timely separation and release of the placenta.

- Medicines. Intravenous or intramuscular administration of uterotonic drugs (oxytocin preparations are preferred) in combination with cord traction is indicated to enhance labor activity. In parallel, intravenous transfusion of crystalloid solutions is performed to correct possible blood loss. nine0020

Surgical treatment

Surgical treatment of delayed separation can be performed non-surgical or operatively. Treatment tactics depend on the cause of the pathology. Surgical intervention should be carried out in a timely manner, before the onset of generalized coagulopathy against the background of massive bleeding (otherwise, the operation aggravates the severity of the condition). In order to stop bleeding, embolization of the uterine vessels, the imposition of hemostatic sutures are used. nine0005

Treatment tactics depend on the cause of the pathology. Surgical intervention should be carried out in a timely manner, before the onset of generalized coagulopathy against the background of massive bleeding (otherwise, the operation aggravates the severity of the condition). In order to stop bleeding, embolization of the uterine vessels, the imposition of hemostatic sutures are used. nine0005

- Handbook. In case of tight attachment of the child's place or other reasons for the delay in its detachment (with the exception of true increment), manual separation of the placenta is performed with its subsequent removal to the outside. To avoid traumatic shock, intravenous anesthesia is performed before manipulation. Antibiotics (penicillin, cephalosporin) are used to prevent septic complications.

- Surgery. nine0004 Indicated for failure of conservative bleeding management, true increment. The volume can vary from organ-preserving surgery (excision of the area of a partially ingrown child with affected myometrium and subsequent plasty) to radical (extirpation of the uterus, supravaginal amputation) with complete ingrowth, intractable bleeding.

Forecast and prevention

In case of timely started adequate treatment, the prognosis for life is favorable. The possibility of further implementation of the reproductive function largely depends on the presence of complications, the cause of the delay in the separation of the placenta. Primary prevention consists in the fight against abortion, the treatment of inflammatory diseases and the correction of endocrine disorders at the stage of preconception preparation. An important aspect of secondary prevention is a planned obstetric ultrasound during the gestation period, which allows early detection of placental accreta and the choice of tactics of labor management. nine0005

Delayed placenta - causes, symptoms, diagnosis and treatment

Delayed placenta is a complication of the third stage of labor, a condition in which the placenta does not fully or partially exfoliate from the uterine walls. Clinically, it can be manifested by pathological bleeding or the absence of bloody discharge normal for this period, soreness, or the absence of attempts. In this case, the standing of the bottom of the uterus corresponds to the period after the expulsion of the fetus, the connection of the umbilical cord with the uterus is indirectly determined. The diagnosis is established on the basis of the results of a physical examination, ultrasound. Most often, manual separation of the placenta or surgical treatment is performed. nine0005

In this case, the standing of the bottom of the uterus corresponds to the period after the expulsion of the fetus, the connection of the umbilical cord with the uterus is indirectly determined. The diagnosis is established on the basis of the results of a physical examination, ultrasound. Most often, manual separation of the placenta or surgical treatment is performed. nine0005

General

According to the WHO definition, retained placenta is diagnosed if separation does not occur within half an hour after the end of the second stage of labour. The incidence of pathology is 0.8-1.2% of all births. This complication is more often recorded in multiparous, especially those with a history of caesarean section. The disease is a serious problem of modern obstetrics, as it is often accompanied by postpartum hemorrhage. Bleeding is the cause of maternal death in a quarter of cases, 30% of which are the result of delayed separation of the placenta. nine0005

Delayed separation of the placenta

Causes

The etiology of delayed separation of the placenta has not been fully understood. Violations of detachment of the placenta and its parts in the afterbirth period, on the one hand, may be due to defects in uterine contractile activity, on the other hand, due to excessively tight attachment of the child's place. Most women in labor fail to detect any visible disorders. The main causes of pathology include:

Violations of detachment of the placenta and its parts in the afterbirth period, on the one hand, may be due to defects in uterine contractile activity, on the other hand, due to excessively tight attachment of the child's place. Most women in labor fail to detect any visible disorders. The main causes of pathology include:

- Hypotension of the uterus. nine0004 Weak contractions of the uterine muscles are not enough to start the process of separation of the placenta, even if the placenta does not have specific features that prevent detachment. In the presence of predisposing conditions, a slight decrease in contractile function can become a trigger for the development of pathology.

- Tight attachment of the placenta. Due to the depletion of the basal layer of the decidua and is characterized by a stronger than normal connection with the uterine walls without the germination of the chorionic villi into the myometrium. With the pathology under consideration, the force of uterine contractions is not enough to completely separate the placenta, which leads to bleeding.

nine0020

nine0020 - True placental accreta. Also associated with underdevelopment of the basal layer, however, in this case, there is invasion of the villi into the muscle tissue, and in rare cases, the serosa of the uterus. More common with placenta previa. Spontaneous detachment of the adherent child's place is impossible, manual separation can lead to perforation of the uterine wall.

- Anomalies in the development of the placenta. Delayed detachment is often observed with developmental anomalies (lobed, two- and three-lobed or with additional lobules) of the placenta. The separation of the afterbirth is difficult with the so-called "membraneous" placenta, which is characterized by a slight thickness and a large attachment area, often extending to the entire uterine wall. nine0020

The most significant risk factors are the endometritis transferred before the onset of pregnancy, obstetric history (surgery on the uterus, abortions, multiple births), indicating traumatic injuries. Inflammation and trauma lead to anatomical and histological changes in the uterus, which negatively affects placentogenesis and myometrial tone. Predisposing conditions include hyperandrogenism, malformations of the uterus (bicornuate uterus, intrauterine septum), volumetric formations (myoma, nodular adenomyosis). nine0005

Inflammation and trauma lead to anatomical and histological changes in the uterus, which negatively affects placentogenesis and myometrial tone. Predisposing conditions include hyperandrogenism, malformations of the uterus (bicornuate uterus, intrauterine septum), volumetric formations (myoma, nodular adenomyosis). nine0005

Pathogenesis

Normally, after the birth of the fetus, afterbirth contractions appear, in which contractions spread to the entire uterus, including the placental site (previously, the muscles of this zone did not function). Labor activity leads to detachment of the child's place in the area of the spongy layer of the mucosa (with the preservation of the basal layer), and then to its exit to the outside. The separation of the placenta is accompanied by damage to blood vessels, physiological bleeding. After his birth, the uterus contracts, which helps to stop the bleeding. nine0005

In the presence of unfavorable factors and predisposing conditions, detachment is difficult. With partial detachment, if the process started, but for some reason stopped, the gaping vessels of the uncontracted uterus become a source of pathological blood loss. Ingrown chorionic villi deep into the myometrium lead to thinning of the uterine wall, so an attempt to manually separate the placenta quickly ends in trauma, accompanied by intense bleeding.

With partial detachment, if the process started, but for some reason stopped, the gaping vessels of the uncontracted uterus become a source of pathological blood loss. Ingrown chorionic villi deep into the myometrium lead to thinning of the uterine wall, so an attempt to manually separate the placenta quickly ends in trauma, accompanied by intense bleeding.

Symptoms

Subjective signs of delayed separation of the placenta include prolonged, painful, ineffective attempts after the birth of a child or their complete absence. An objective sign is intense bleeding observed with partial separation. If detachment of the placenta does not occur at all, even in a partial volume (for example, with a complete increment), bloody discharge from the birth canal may be absent.

Complications

The most common complication of delayed separation of the placenta is bleeding. Significant blood loss leads to such a potentially fatal complication as hemorrhagic shock, accompanied by multiple organ failure. Massive bleeding often develops when professional medical care is not provided in time (the risk increases sharply during childbirth outside a medical institution). nine0005

Massive bleeding often develops when professional medical care is not provided in time (the risk increases sharply during childbirth outside a medical institution). nine0005

Other frequent complications of this pathology include purulent-inflammatory diseases (postpartum endometritis, pelvioperitonitis, obstetric sepsis), which can be the result of both surgical treatment and retention of placenta fragments in the uterine cavity. In addition, the remaining ingrown placenta can become a source of late postpartum hemorrhage, uterine rupture during a subsequent pregnancy.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of retained placenta is made by the obstetrician if there is no discharge of the placenta within thirty minutes after the birth of the infant with appropriate results of the physical examination. To establish the causes of the pathological condition (which determines the choice of treatment tactics), an ultrasound examination is additionally used. nine0005

nine0005

- Clinical examination. Signs of delayed separation of the placenta are determined by the shape and location of the uterus, the mobility of the umbilical cord. If separation has not occurred, the uterus is rounded, the bottom is located at the navel (Schroeder's sign), the outer segment of the umbilical cord does not lengthen (Alfeld's sign). The umbilical cord retracts with pressure over the womb (Kyustner-Chukalov's sign), after inhalation (Dovzhenko's sign), straining (Klein's sign).

- Ultrasonography. nine0004 Ultrasound of the uterus is prescribed for the diagnosis of placenta accreta. Ultrasound signs of this pathology include deformation of the internal contour of the uterine cavity, its uneven expansion, and the absence of a hypoechoic layer between the myometrium and the placenta. Ultrasound angiography reveals hypervascularization of the anterior wall, chaotic branching of vessels.

If the placenta is retained, the volume of blood lost is estimated (abnormal blood loss is more than 400-500 ml). If a surgical operation is necessary, a coagulogram and a clinical blood test are examined. Differential diagnosis is carried out with a delay in the birth of the separated placenta, primarily with its infringement due to uneven or spastic contractions of the myometrium. nine0005

If a surgical operation is necessary, a coagulogram and a clinical blood test are examined. Differential diagnosis is carried out with a delay in the birth of the separated placenta, primarily with its infringement due to uneven or spastic contractions of the myometrium. nine0005

Treatment of delayed separation of the placenta

Conservative therapy

Therapeutic measures to promote the separation of the placenta are carried out only in the absence of pathological bleeding, and can last for 20-30 minutes. With the ineffectiveness of conservative treatment, surgical methods are used; in case of pathological blood loss, replacement blood transfusion is performed. Therapy is aimed at strengthening uterine contractions and includes:

- Bladder catheterization. Since the muscular layer of the bladder is closely connected with the nerve fibers of the uterine muscles, irritation of the urothelial receptors leads to a reflex contraction of the myometrium.

Catheterization normalizes the course of the afterbirth period of childbirth, contributes to the timely separation and release of the placenta.

Catheterization normalizes the course of the afterbirth period of childbirth, contributes to the timely separation and release of the placenta. - Medicines. Intravenous or intramuscular administration of uterotonic drugs (oxytocin preparations are preferred) in combination with cord traction is indicated to enhance labor activity. In parallel, intravenous transfusion of crystalloid solutions is performed to correct possible blood loss. nine0020

Surgical treatment

Surgical treatment of delayed separation can be performed non-surgical or operatively. Treatment tactics depend on the cause of the pathology. Surgical intervention should be carried out in a timely manner, before the onset of generalized coagulopathy against the background of massive bleeding (otherwise, the operation aggravates the severity of the condition). In order to stop bleeding, embolization of the uterine vessels, the imposition of hemostatic sutures are used. nine0005

nine0005

- Handbook. In case of tight attachment of the child's place or other reasons for the delay in its detachment (with the exception of true increment), manual separation of the placenta is performed with its subsequent removal to the outside. To avoid traumatic shock, intravenous anesthesia is performed before manipulation. Antibiotics (penicillin, cephalosporin) are used to prevent septic complications.

- Surgery. nine0004 Indicated for failure of conservative bleeding management, true increment. The volume can vary from organ-preserving surgery (excision of the area of a partially ingrown child with affected myometrium and subsequent plasty) to radical (extirpation of the uterus, supravaginal amputation) with complete ingrowth, intractable bleeding.

Forecast and prevention

In case of timely started adequate treatment, the prognosis for life is favorable. The possibility of further implementation of the reproductive function largely depends on the presence of complications, the cause of the delay in the separation of the placenta.