Reason for postpartum hemorrhage

Postpartum hemorrhage | March of Dimes

Postpartum hemorrhage (also called PPH) is a serious but rare condition when a woman has heavy bleeding after giving birth.

If you think you’re having PPH, call your health care provider or 911 immediately.

You may have PPH if you have heavy bleeding from the vagina that doesn’t slow or stop, blurred vision or chills, or if you feel weak or like you’re going to faint.

You’re more likely to have PPH if you’ve had it in the past or if you have certain medical conditions, especially conditions that affect the uterus (womb) or the placenta or conditions that affect how your blood clots.

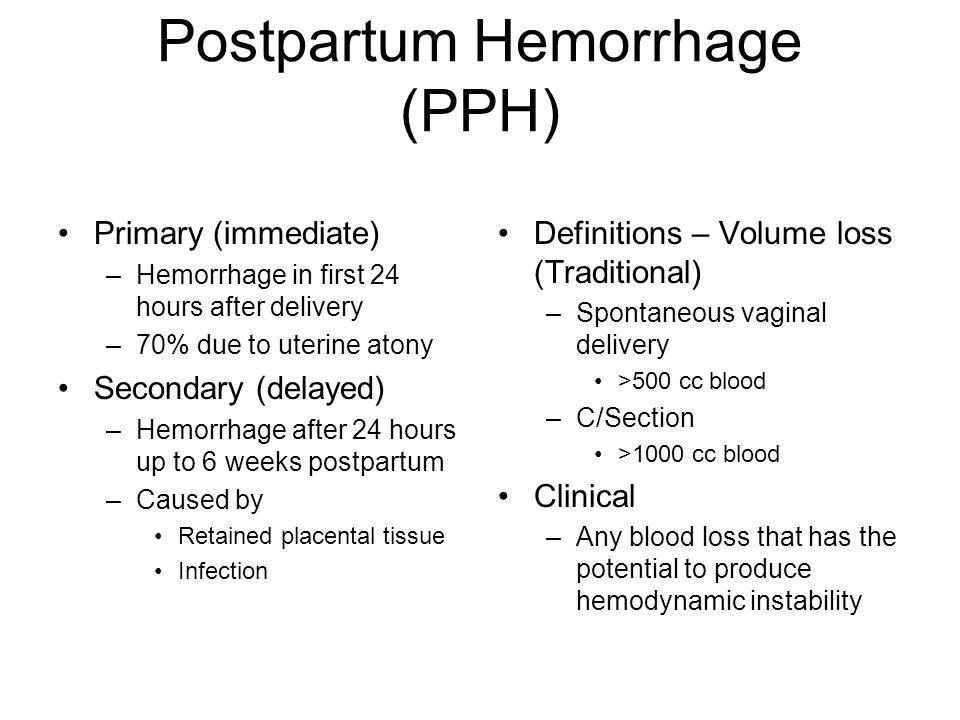

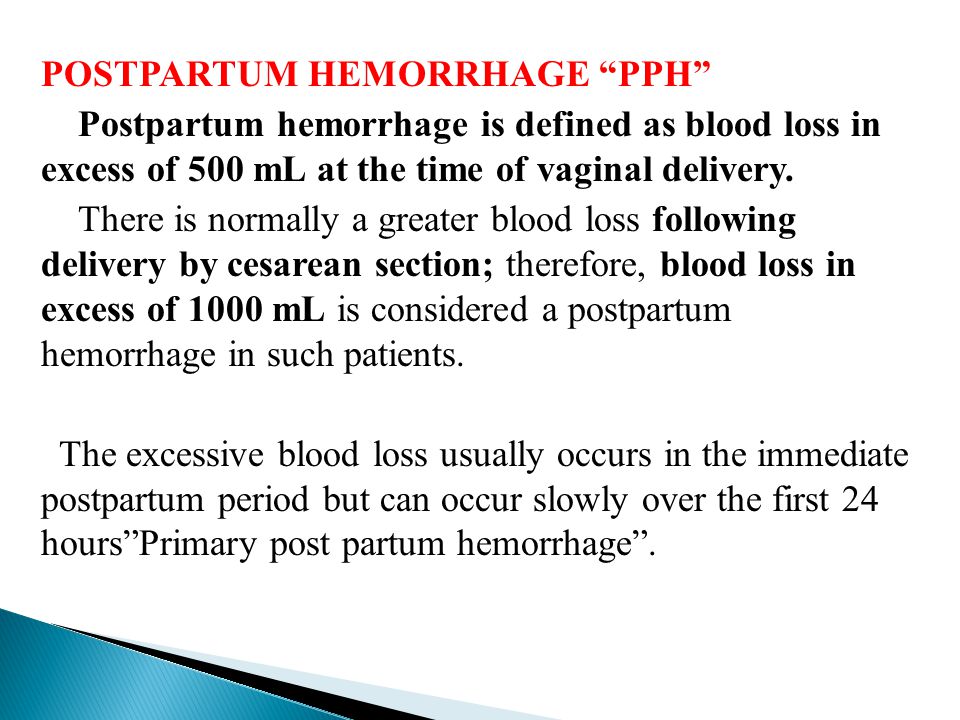

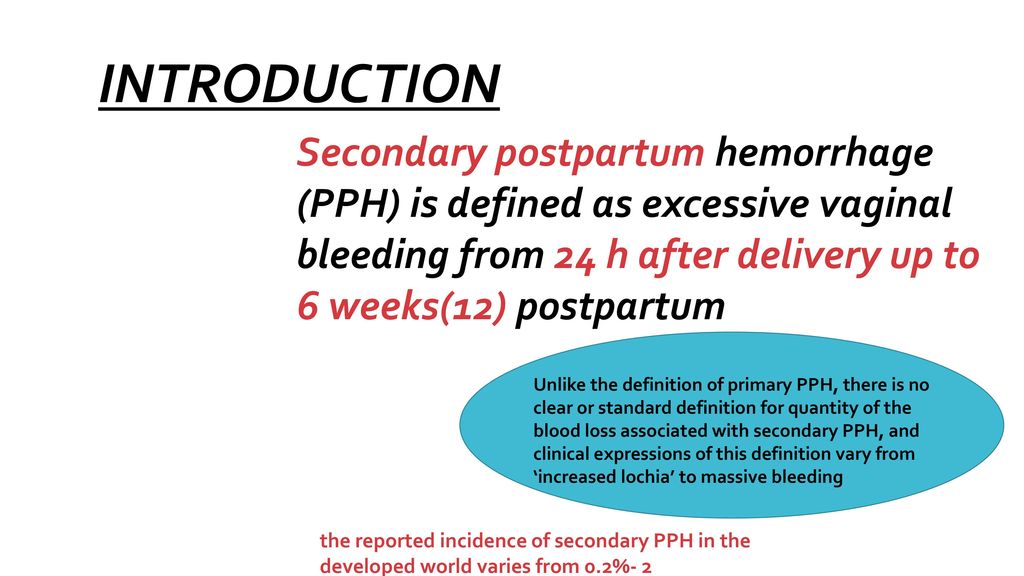

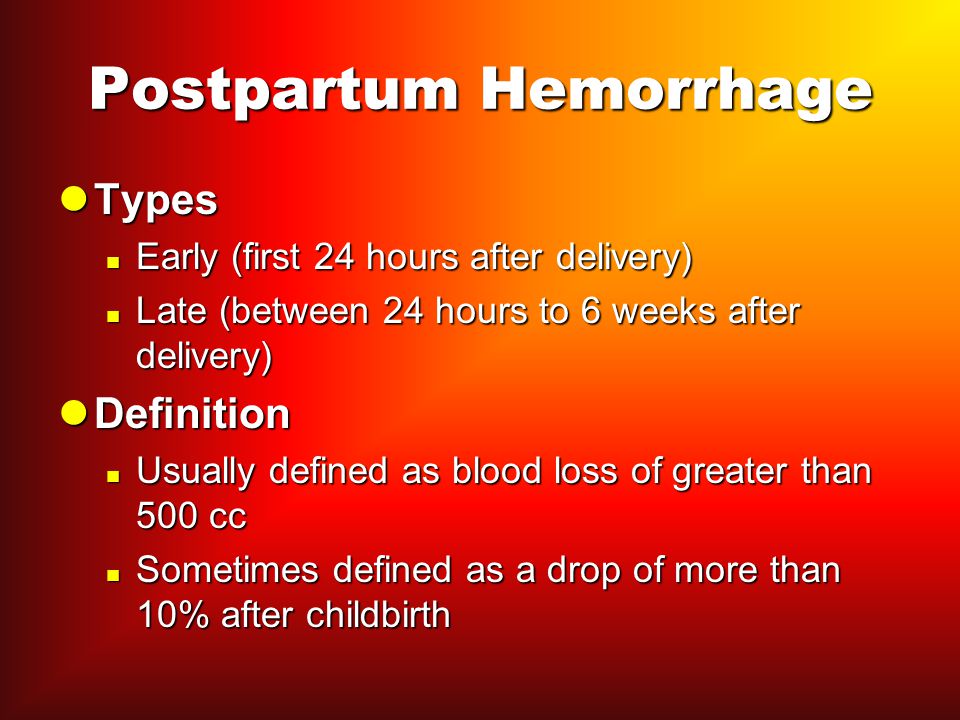

Postpartum hemorrhage (also called PPH) is when a woman has heavy bleeding after giving birth. It’s a serious but rare condition. It usually happens within 1 day of giving birth, but it can happen up to 12 weeks after having a baby. About 1 to 5 in 100 women who have a baby (1 to 5 percent) have PPH.

It’s normal to lose some blood after giving birth. Women usually lose about half a quart (500 milliliters) during vaginal birth or about 1 quart (1,000 milliliters) after a cesarean birth (also called c-section). A c-section is surgery in which your baby is born through a cut that your doctor makes in your belly and uterus (womb). With PPH, you can lose much more blood, which is what makes it a dangerous condition. PPH can cause a severe drop in blood pressure. If not treated quickly, this can lead to shock and death. Shock is when your body organs don’t get enough blood flow.

When does PPH happen?

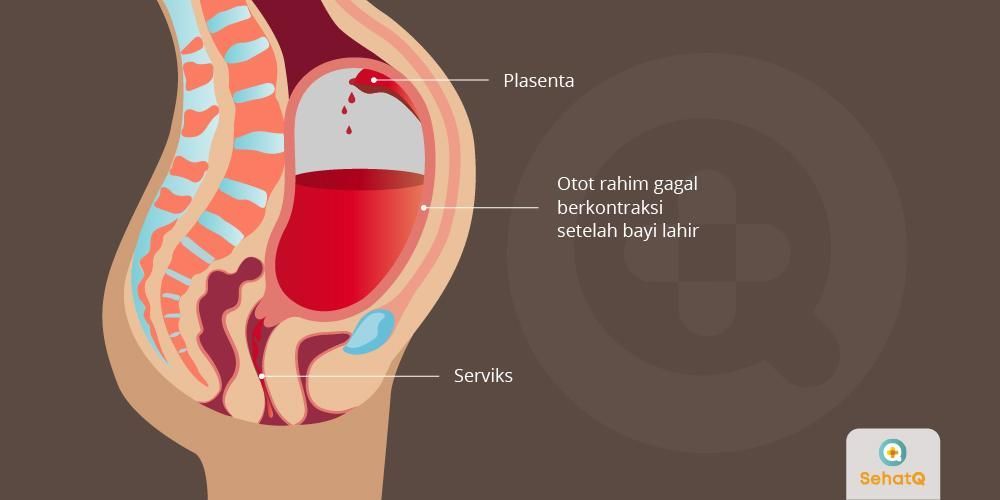

After your baby is delivered, the uterus normally contracts to push out the placenta. The contractions then help put pressure on bleeding vessels where the placenta was attached in your uterus. The placenta grows in your uterus and supplies the baby with food and oxygen through the umbilical cord. If the contractions are not strong enough, the vessels bleed more. It can also happen if small pieces of the placenta stay attached.

It can also happen if small pieces of the placenta stay attached.

How do you know if you have PPH?

You may have PPH if you have any of these signs or symptoms. If you do, call your health care provider or 911 right away:

- Heavy bleeding from the vagina that doesn’t slow or stop

- Drop in blood pressure or signs of shock. Signs of low blood pressure and shock include blurry vision; having chills, clammy skin or a really fast heartbeat; feeling confused dizzy, sleepy or weak; or feeling like you’re going to faint.

- Nausea (feeling sick to your stomach) or throwing up

- Pale skin

- Swelling and pain around the vagina or perineum. The perineum is the area between the vagina and rectum.

Are some women more likely than others to have PPH?

Yes. Things that make you more likely than others to have PPH are called risk factors. Having a risk factor doesn’t mean for sure that you will have PPH, but it may increase your chances. PPH usually happens without warning. But talk to your health care provider about what you can do to help reduce your risk for having PPH.

PPH usually happens without warning. But talk to your health care provider about what you can do to help reduce your risk for having PPH.

You’re more likely than other women to have PPH if you’ve had it before. This is called having a history of PPH. Asian and Hispanic women also are more likely than others to have PPH.

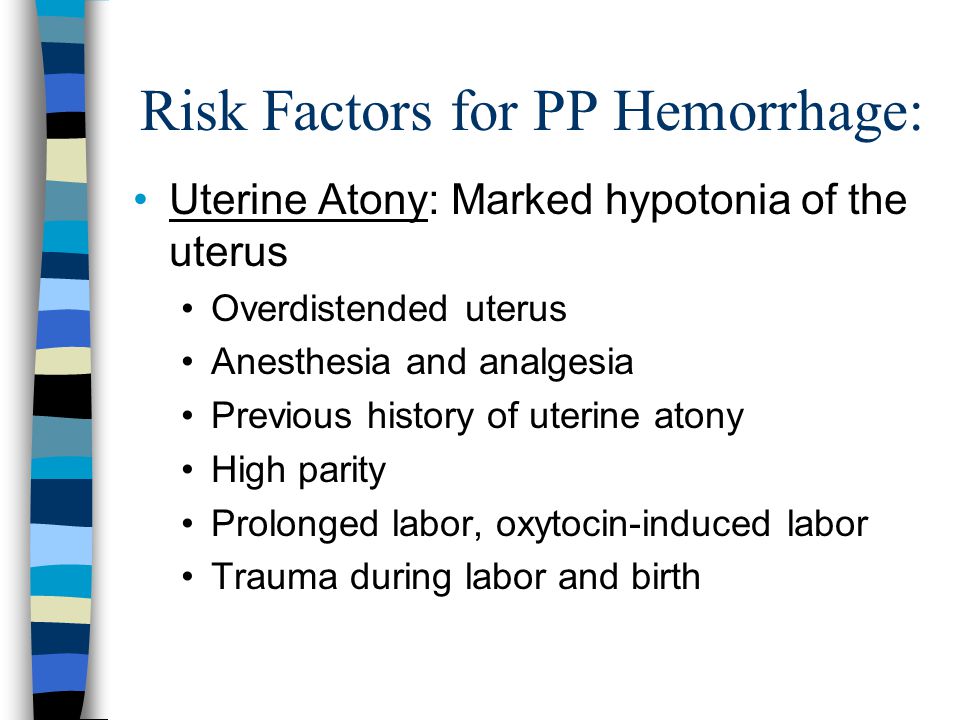

Several medical conditions are risk factors for PPH. You may be more likely than other women to have PPH if you have any of these conditions:

Conditions that affect the uterus

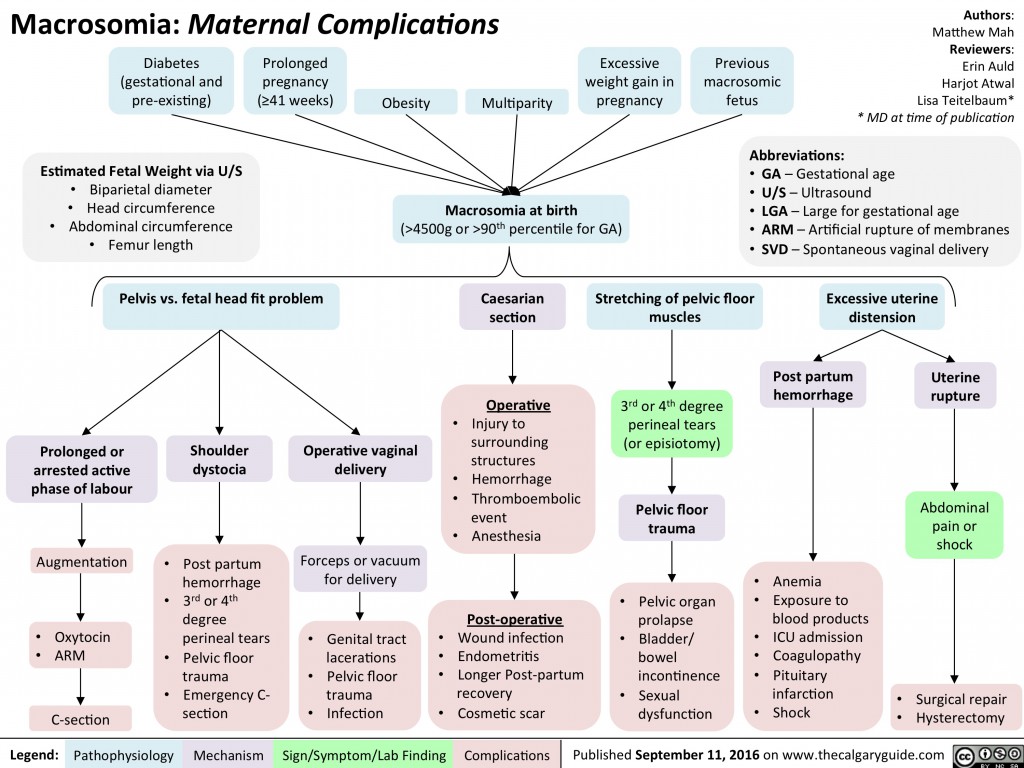

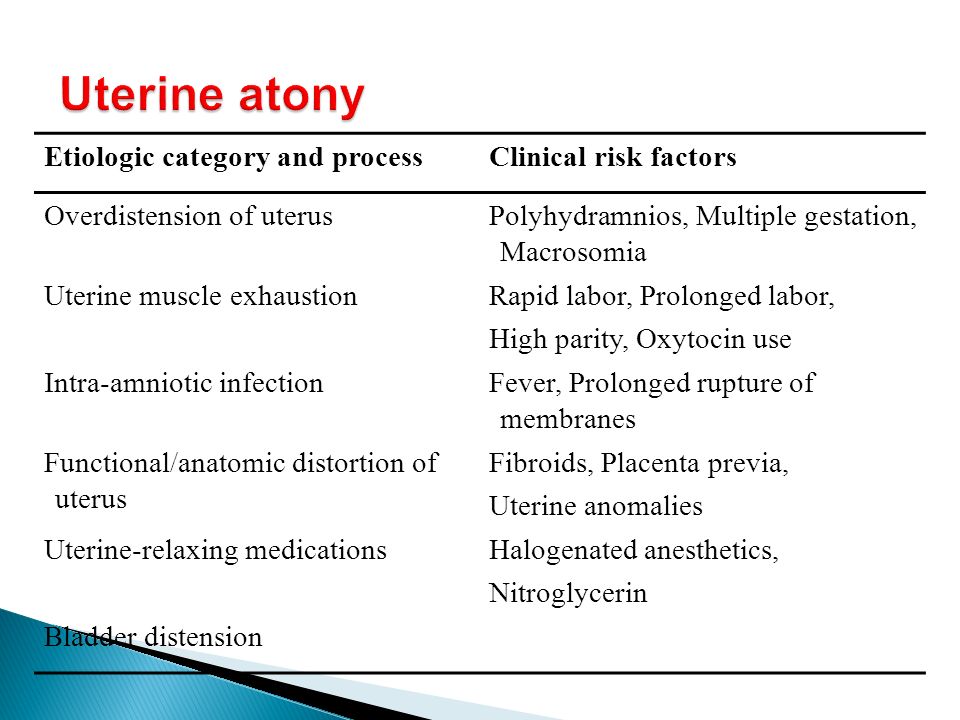

- Uterine atony. This is the most common cause of PPH. It happens when the muscles in your uterus don’t contract (tighten) well after birth. Uterine contractions after birth help stop bleeding from the place in the uterus where the placenta breaks away. You may have uterine atony if your uterus is stretched or enlarged (also called distended) from giving birth to twins or a large baby (more than 8 pounds, 13 ounces). It also can happen if you’ve already had several children, you’re in labor for a long time or you have too much amniotic fluid.

Amniotic fluid is the fluid that surrounds your baby in the womb.

Amniotic fluid is the fluid that surrounds your baby in the womb. - Uterine inversion. This is a rare condition when the uterus turns inside out after birth.

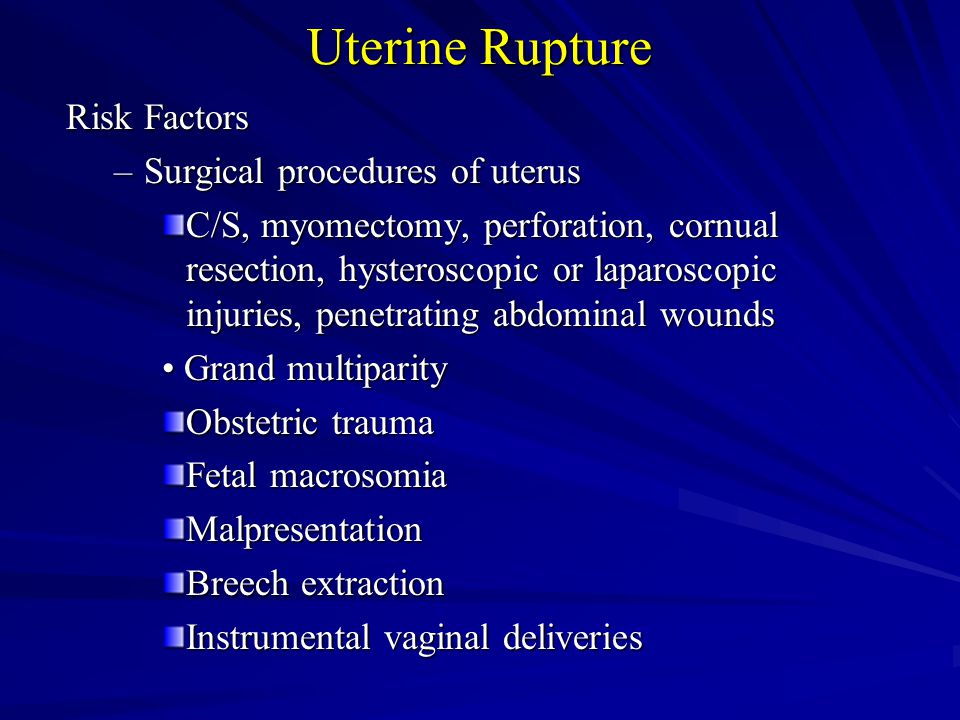

- Uterine rupture. This is when the uterus tears during labor. It happens rarely. It may happen if you have a scar in the uterus from having a c-section in the past or if you’ve had other kinds of surgery on the uterus.

Conditions that affect the placenta

- Placental abruption. This is when the placenta separates early from the wall of the uterus before birth. It can separate partially or completely.

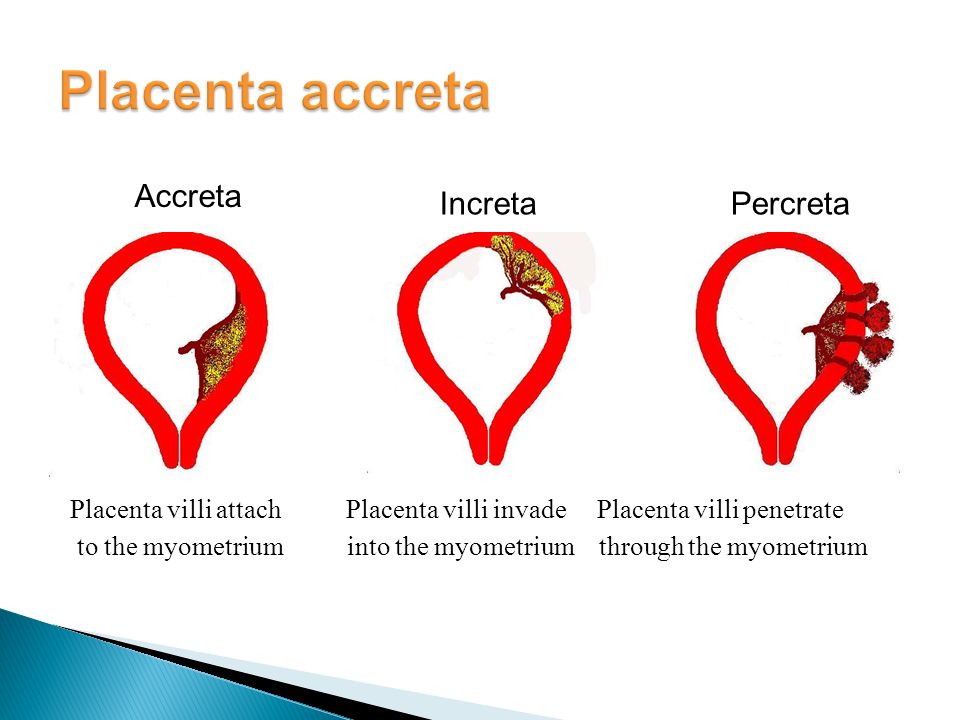

- Placenta accreta, placenta increta or placenta percreta. These conditions happen when the placenta grows into the wall of the uterus too deeply and cannot separate.

- Placenta previa. This is when the placenta lies very low in the uterus and covers all or part of the cervix.

The cervix is the opening to the uterus that sits at the top of the vagina.

The cervix is the opening to the uterus that sits at the top of the vagina. - Retained placenta. This happens if you don’t pass the placenta within 30 to 60 minutes after you give birth. Even if you pass the placenta soon after birth, your provider checks the placenta to make sure it’s not missing any tissue. If tissue is missing and is not removed from the uterus right away, it may cause bleeding.

Conditions during labor and birth

- Having a c-section

- Getting general anesthesia. This is medicine that puts you to sleep so you don’t feel pain during surgery. If you have an emergency c-section, you may need general anesthesia.

- Taking medicines to induce labor. Providers often use a medicine called Pitocin to induce labor. Pitocin is the man-made form of oxytocin, a hormone your body makes to start contractions.

- Taking medicines to stop contractions during preterm labor. If you have preterm labor, your provider may give you medicines called tocolytics to slow or stop contractions.

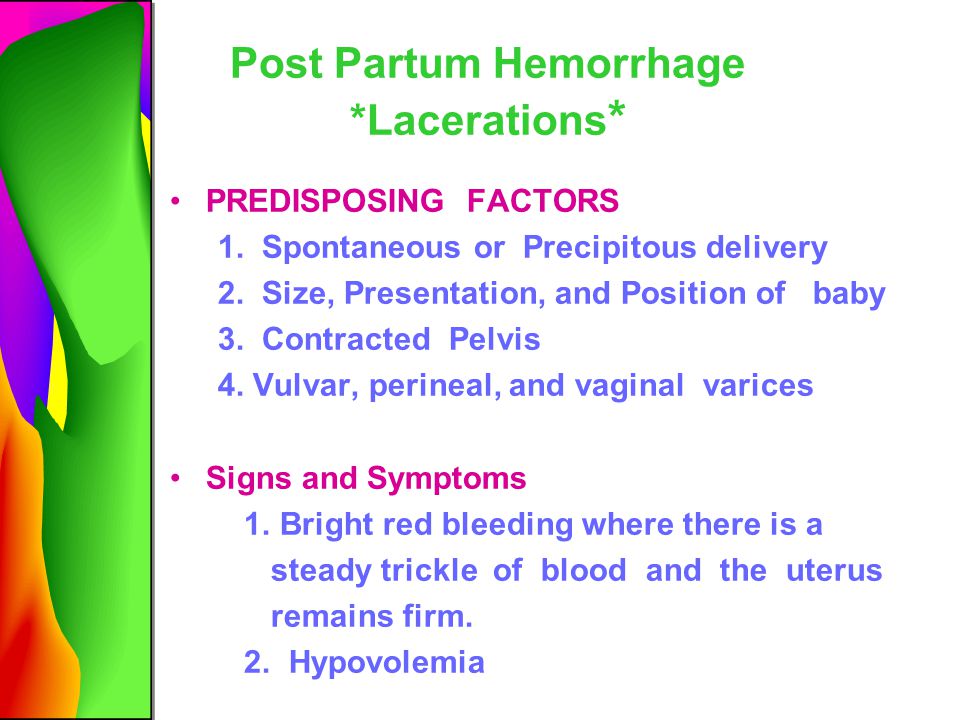

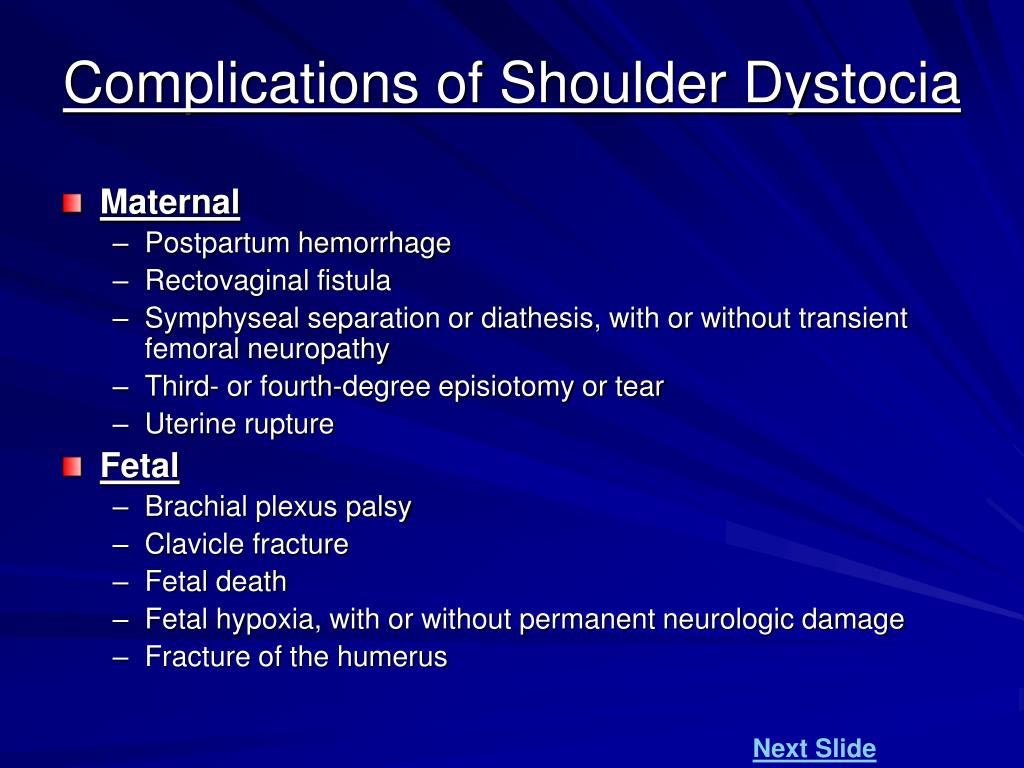

- Tearing (also called lacerations). This may happen if the tissues in your vagina or cervix are cut or torn during birth. The cervix is the opening to the uterus that sits at the top of the vagina. You may have tearing if you give birth to a large baby, your baby is born through the birth canal too quickly or you have an episiotomy that tears. An episiotomy is a cut made at the opening of the vagina to help let the baby out. Tearing also can happen if your provider uses tools, like forceps or a vacuum, to help move your baby through the birth canal during birth. Forceps look like big tongs. A vacuum is a soft plastic cup that attaches to your baby’s head. It uses suction to gently pull your baby as you push during birth.

- Having quick labor or being in labor a long time.

Labor is different for every woman. If you’re giving birth for the first time, labor usually takes about 14 hours. If you’ve given birth before, it usually takes about 6 hours. Augmented labor may also increase risk of PPH. Augmentation of labor means medications or other means are used to make more contractions of the uterus during labor.

Labor is different for every woman. If you’re giving birth for the first time, labor usually takes about 14 hours. If you’ve given birth before, it usually takes about 6 hours. Augmented labor may also increase risk of PPH. Augmentation of labor means medications or other means are used to make more contractions of the uterus during labor.

Other conditions

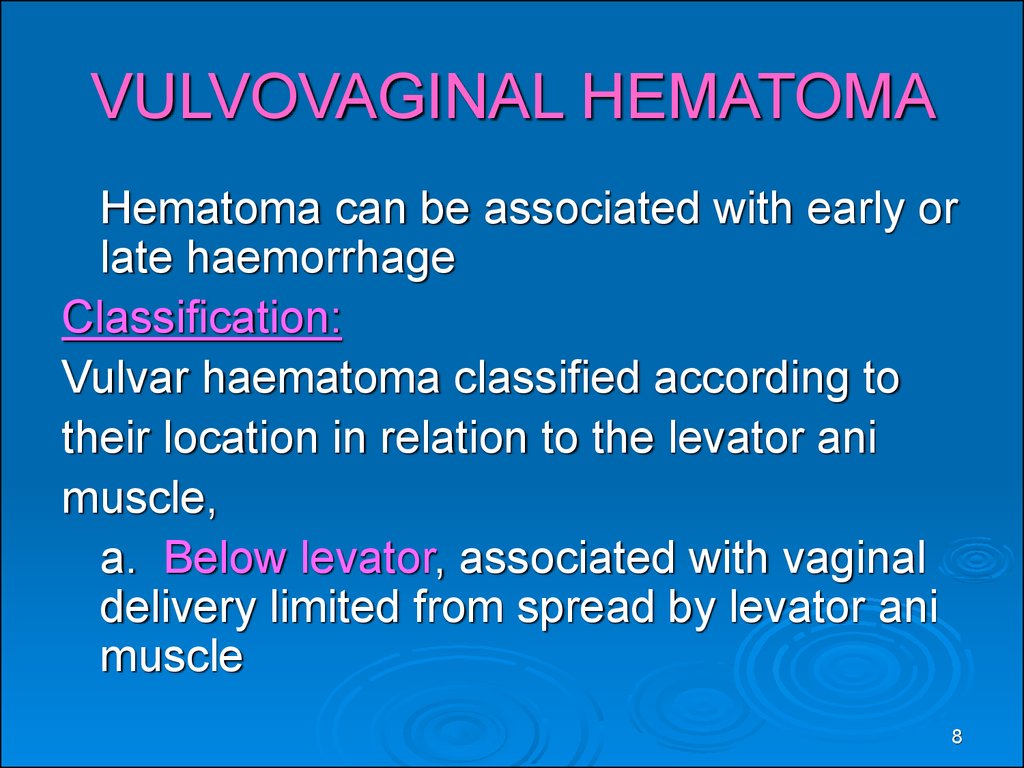

- Blood conditions, like von Willebrand disease or disseminated intravascular coagulation (also called DIC). These conditions can increase your risk of forming a hematoma. A hematoma happens when a blood vessel breaks causing a blood clot to form in tissue, an organ or another part of the body. After giving birth, some women develop a hematoma in the vaginal area or the vulva (the female genitalia outside of the body). Von Willebrand’s disease is a bleeding disorder that makes it hard for a person to stop bleeding. DIC causes blood clots to form in small blood vessels and can lead to serious bleeding.

Certain pregnancy and childbirth complications (like placenta accreta), surgery, sepsis (blood infection) and cancer can cause DIC.

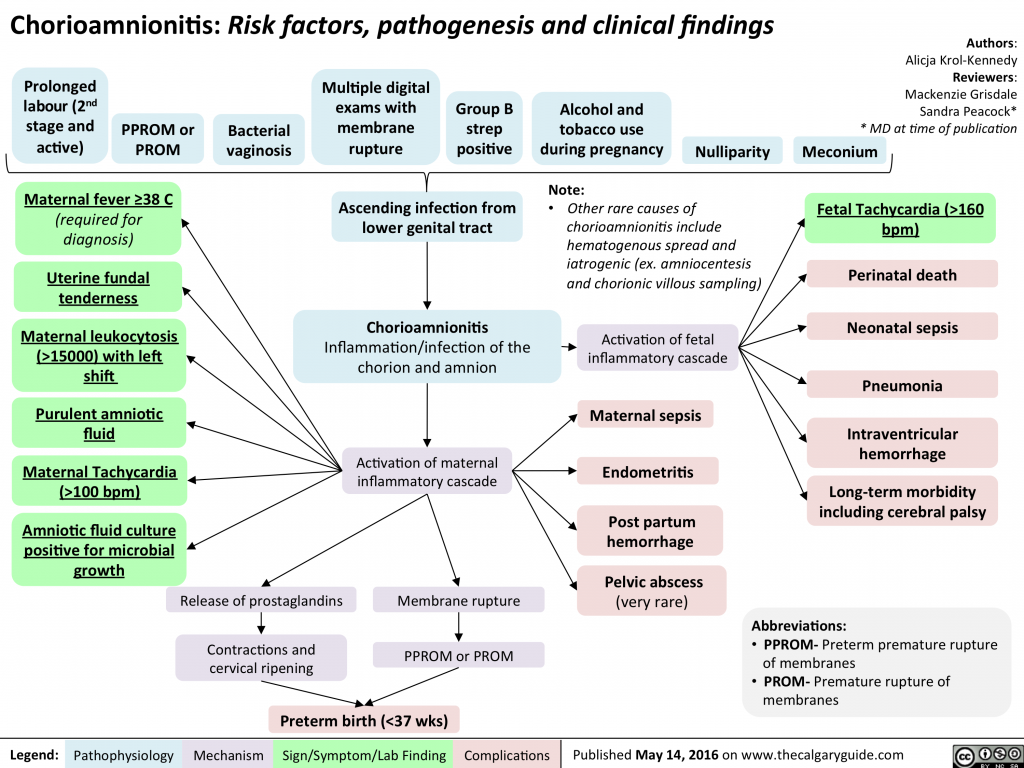

Certain pregnancy and childbirth complications (like placenta accreta), surgery, sepsis (blood infection) and cancer can cause DIC. - Infection, like chorioamnionitis. This is an infection of the placenta and amniotic fluid.

- Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (also called ICP). This is the most common liver condition that happens during pregnancy.

- Obesity. Being obese means you have an excess amount of body fat. If you’re obese, your body mass index (also called BMI) is 30 or higher. BMI is a measure of body fat based on your height and weight. To find out your BMI, go to www.cdc.gov/bmi.

- Preeclampsia or gestational hypertension. These are types of high blood pressure that only pregnant women can get. Preeclampsia is a condition that can happen after the 20th week of pregnancy or right after pregnancy. It’s when a pregnant woman has high blood pressure and signs that some of her organs, like her kidneys and liver, may not be working properly.

Signs of preeclampsia include having protein in the urine, changes in vision and severe headache. Gestational hypertension is high blood pressure that starts after 20 weeks of pregnancy and goes away after you give birth. Some women with gestational hypertension have preeclampsia later in pregnancy.

Signs of preeclampsia include having protein in the urine, changes in vision and severe headache. Gestational hypertension is high blood pressure that starts after 20 weeks of pregnancy and goes away after you give birth. Some women with gestational hypertension have preeclampsia later in pregnancy.

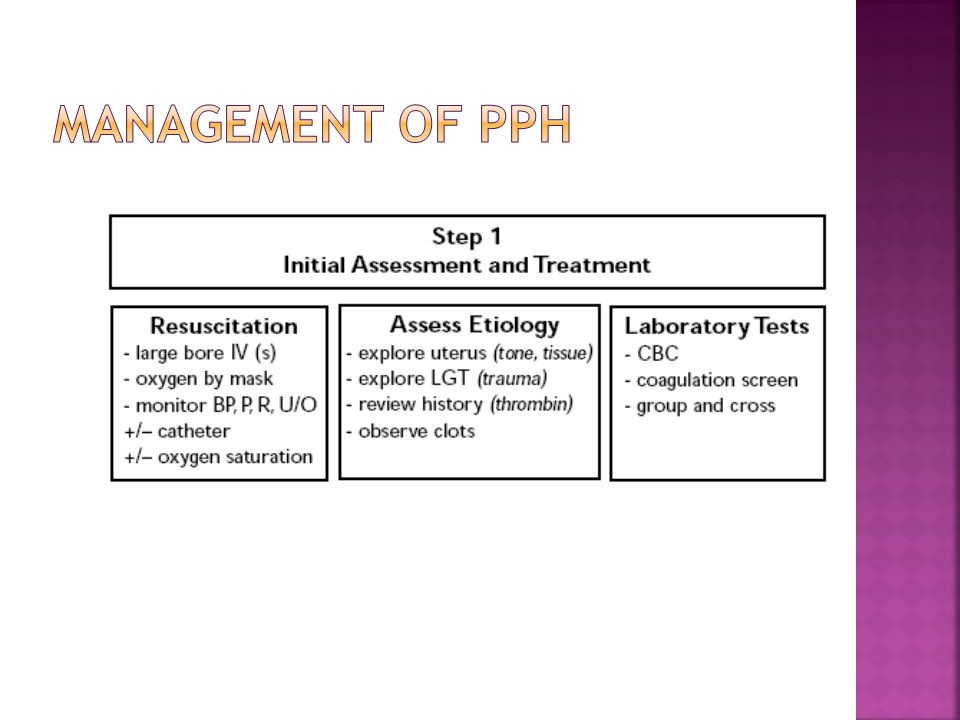

How is PPH tested for and treated?

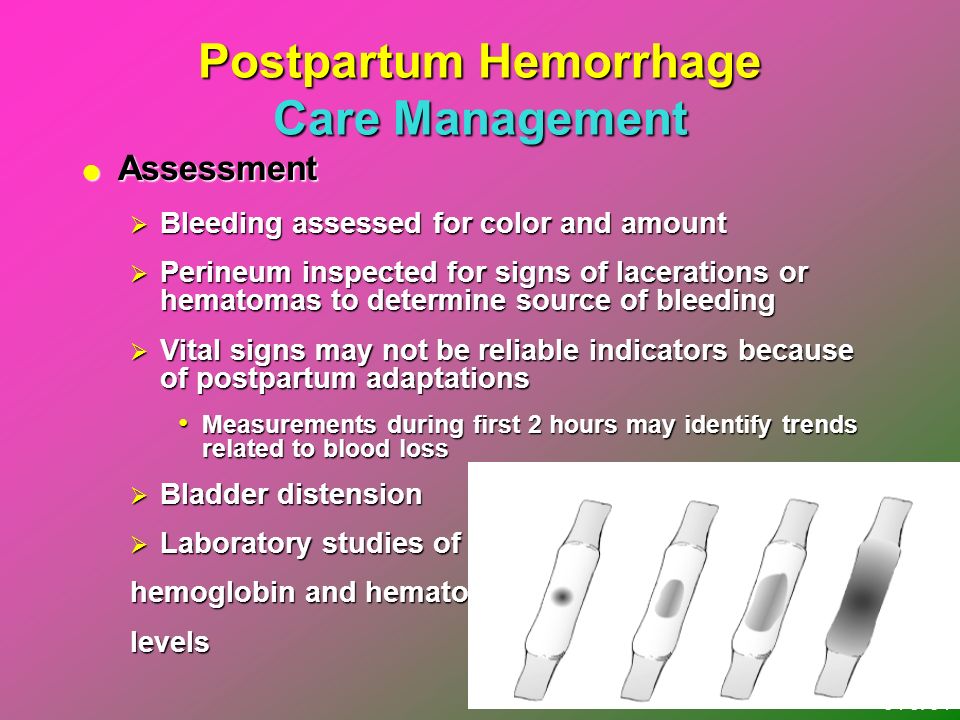

Your provider may use these tests to see if you have PPH or try to find the cause for PPH:

- Blood tests called clotting factors tests or factor assays

- Hematocrit. This is a blood test that checks the percent of your blood (called whole blood) that’s made up of red blood cells. Bleeding can cause a low hematocrit.

- Blood loss measurement. To see how much blood you’ve lost, your provider may weigh or count the number of pads and sponges used to soak up the blood.

- Pelvic exam. Your provider checks your vagina, uterus and cervix.

- Physical exam. Your provider checks your pulse and blood pressure.

- Ultrasound. Your provider can use ultrasound to check for problems with the placenta or uterus. Ultrasound is a test that uses sound waves and a computer screen to make a picture of your baby inside the womb or your pelvic organs.

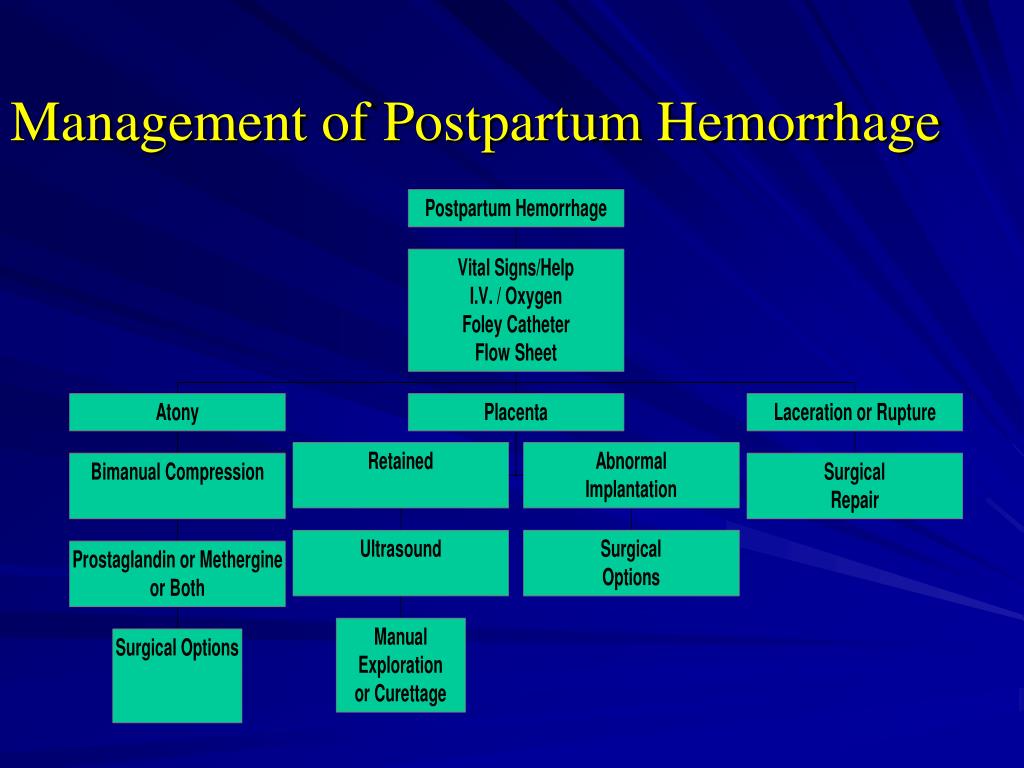

Treatment depends on what’s causing your bleeding. It may include:

- Getting fluids, medicine (like Pitocin) or having a blood transfusion (having new blood put into your body). You get these treatments through a needle into your vein (also called intravenous or IV), or you may get some directly in the uterus.

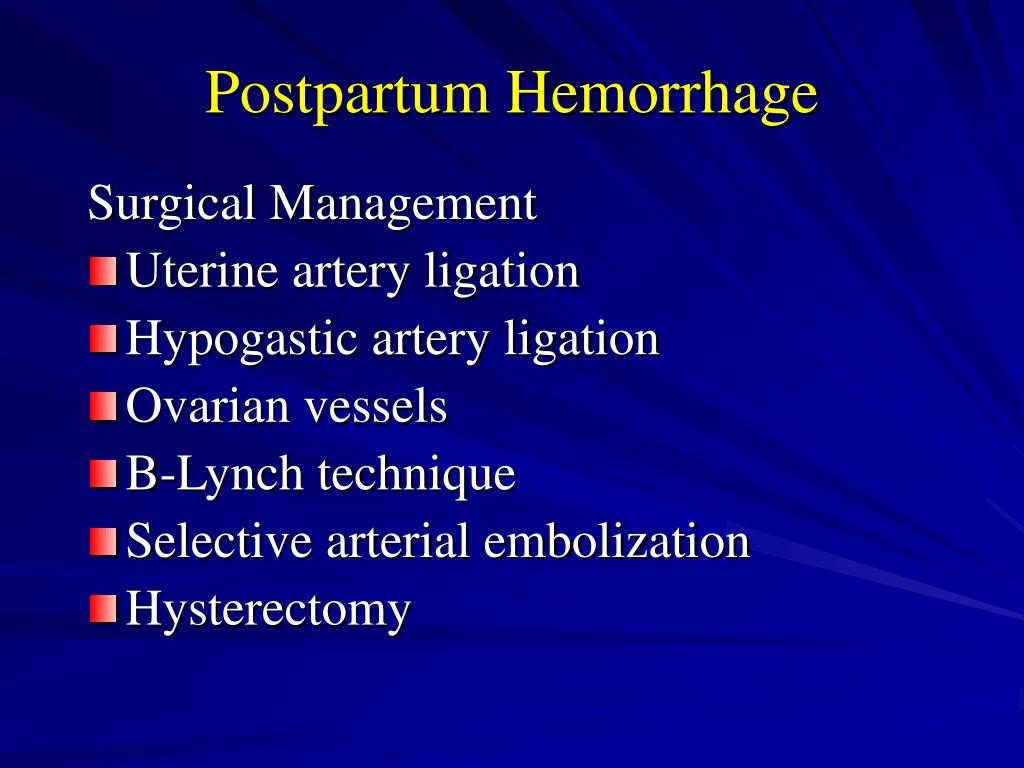

- Having surgery, like a hysterectomy or a laparotomy. A hysterectomy is when your provider removes your uterus. You usually only need a hysterectomy if other treatments don’t work. A laparotomy is when your provider opens your belly to check for the source of bleeding and stops the bleeding.

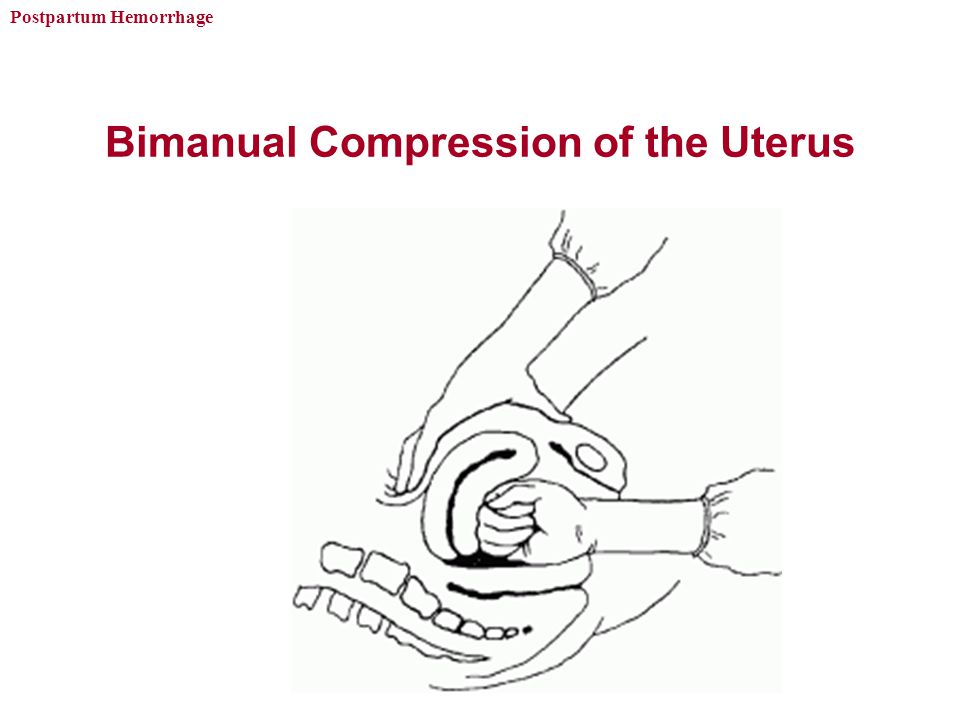

- Massaging the uterus by hand. Your provider can massage the uterus to help it contract, lessen bleeding and help the body pass blood clots. Your provider may also give you medications like oxytocin to make the uterus contract and lessen bleeding.

- Getting oxygen by wearing an oxygen mask

- Removing any remaining pieces of the placenta from the uterus, packing the uterus with gauze, a special balloon or sponges, or using medical tools or stitches to help stop bleeding from blood vessels.

- Embolization of the blood vessels that supply the uterus. In this procedure, a provider uses special tests to find the bleeding blood vessel and injects material into the vessel to stop the bleeding. It’s used in special cases and may prevent you from needing a hysterectomy.

- Taking extra iron supplements along with a prenatal vitamin may also help. Your provider may recommend this depending on how much blood was lost.

See also: Maternal death

Last reviewed March 2020

Postpartum Hemorrhage: Prevention and Treatment

ANN EVENSEN, MD, JANICE M. ANDERSON, MD, AND PATRICIA FONTAINE, MD, MS

This is an updated version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(7):442-449

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

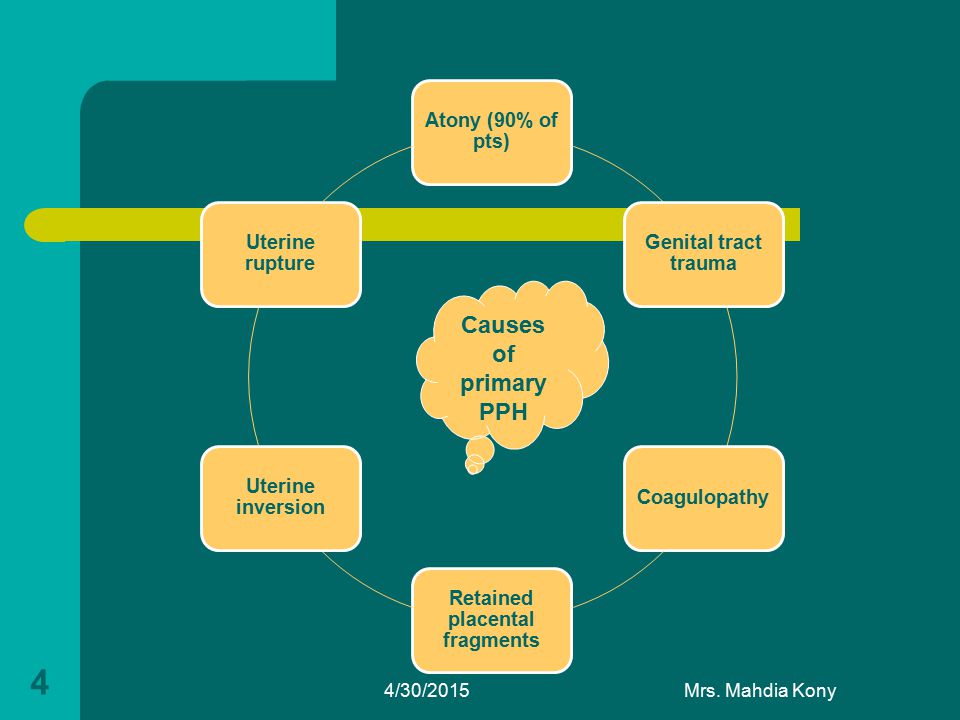

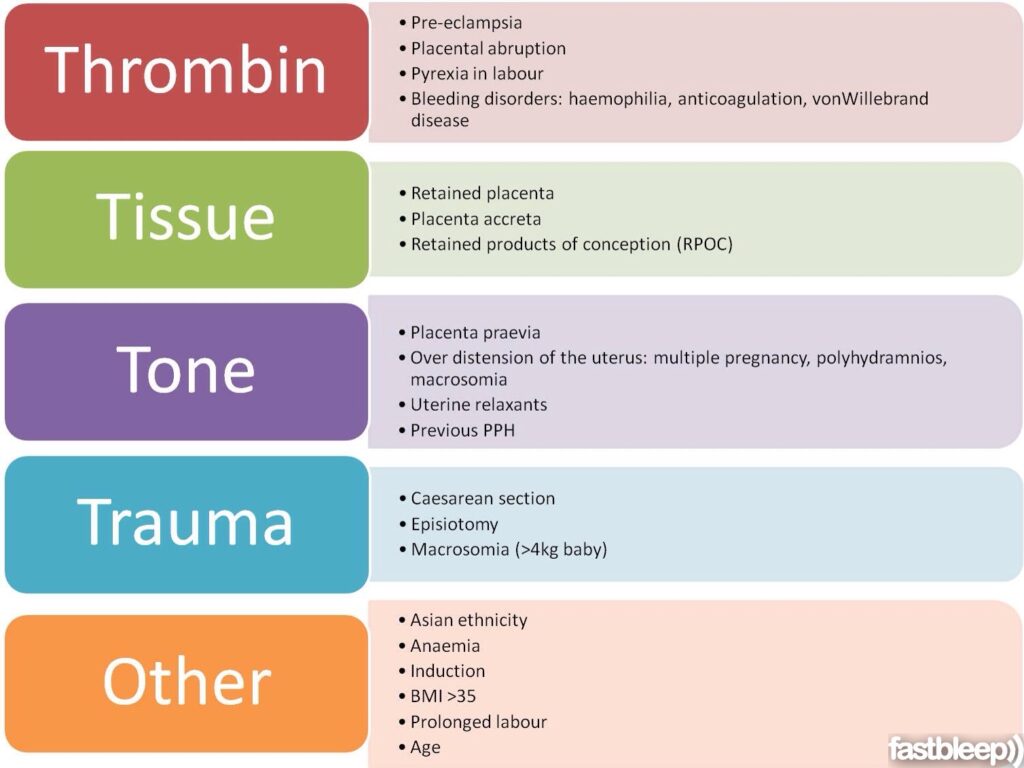

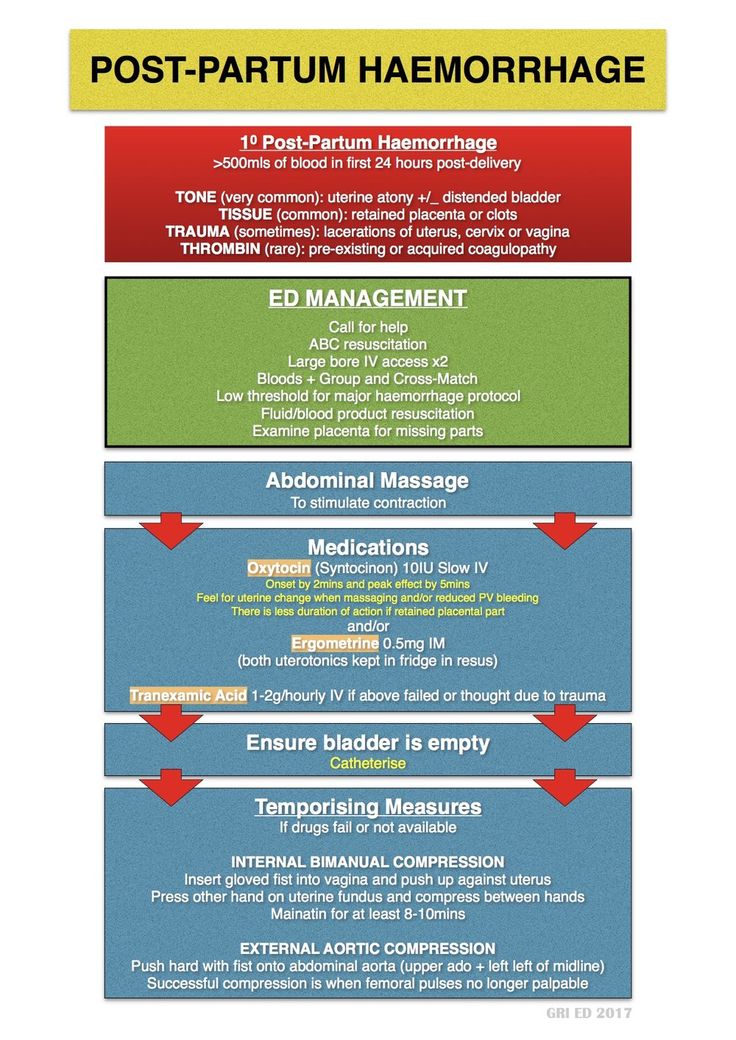

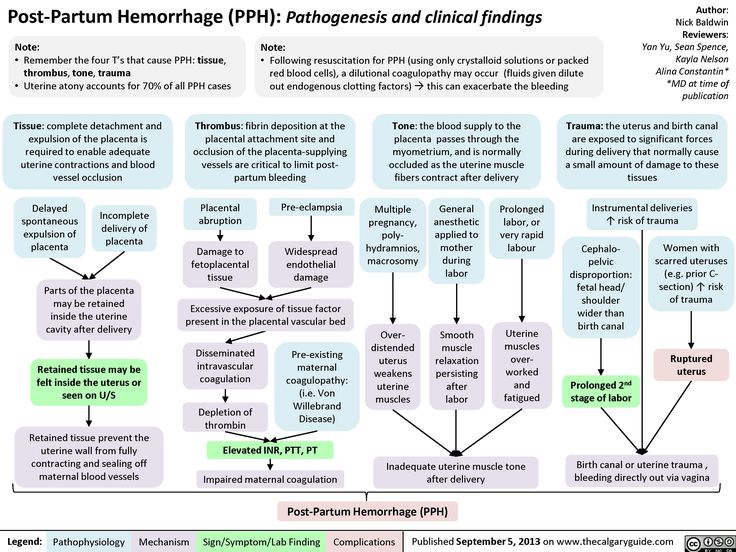

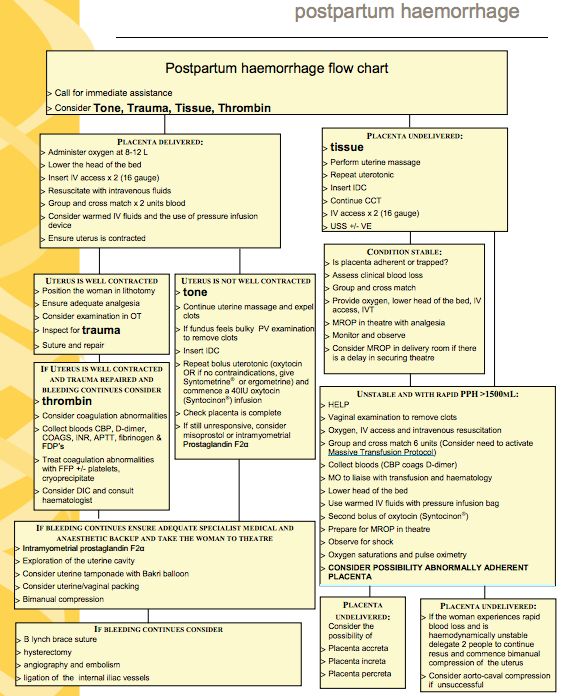

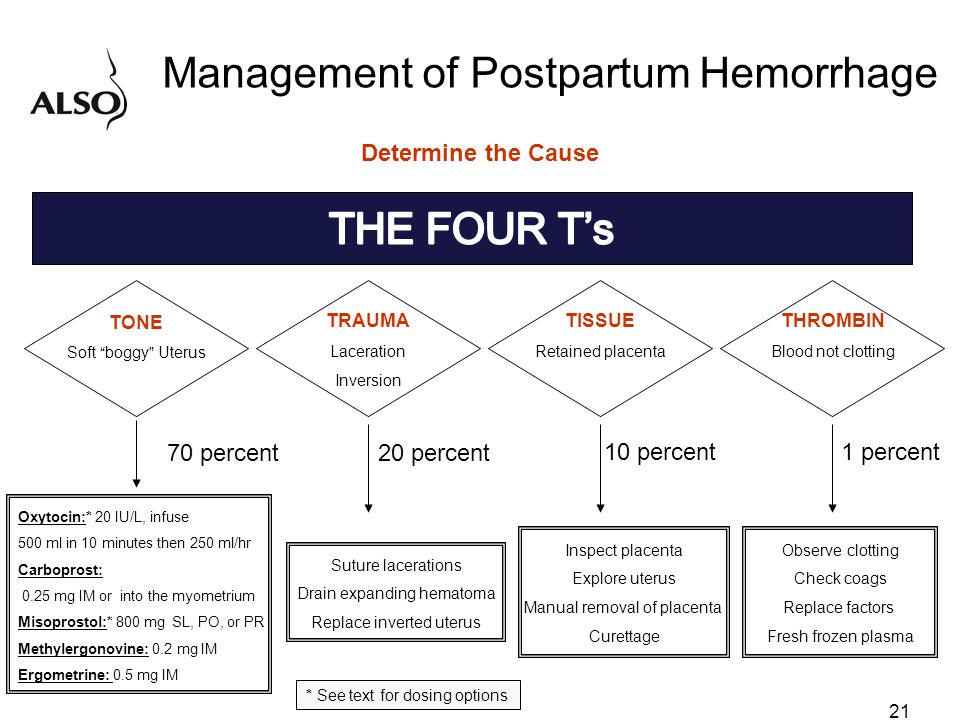

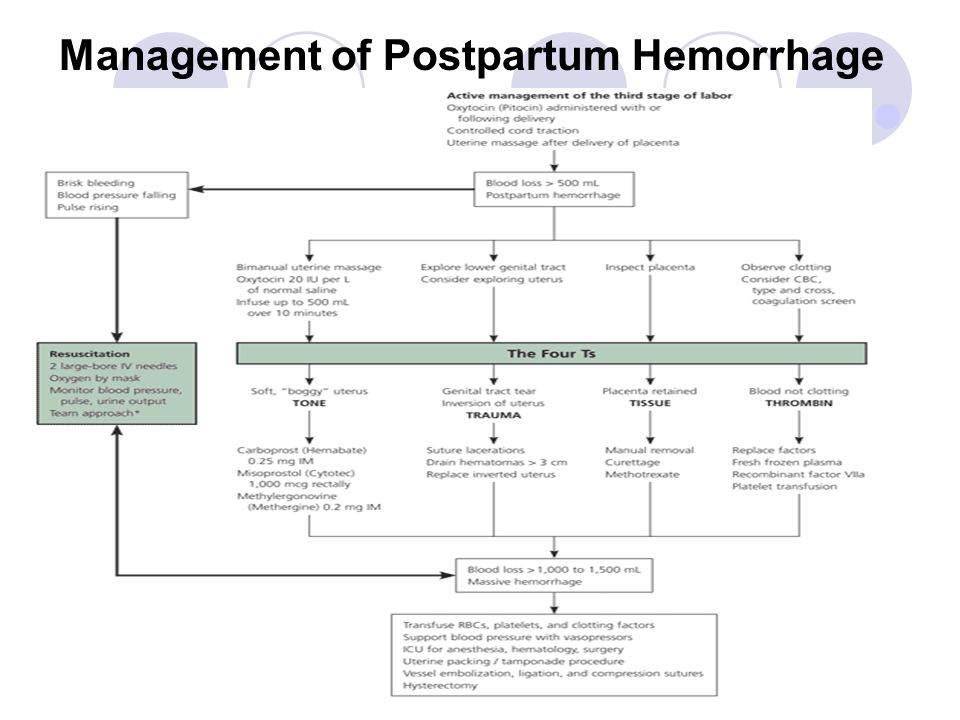

Postpartum hemorrhage is common and can occur in patients without risk factors for hemorrhage. Active management of the third stage of labor should be used routinely to reduce its incidence. Use of oxytocin after delivery of the anterior shoulder is the most important and effective component of this practice. Oxytocin is more effective than misoprostol for prevention and treatment of uterine atony and has fewer adverse effects. Routine episiotomy should be avoided to decrease blood loss and the risk of anal laceration. Appropriate management of postpartum hemorrhage requires prompt diagnosis and treatment. The Four T's mnemonic can be used to identify and address the four most common causes of postpartum hemorrhage (uterine atony [Tone]; laceration, hematoma, inversion, rupture [Trauma]; retained tissue or invasive placenta [Tissue]; and coagulopathy [Thrombin]). Rapid team-based care minimizes morbidity and mortality associated with postpartum hemorrhage, regardless of cause. Massive transfusion protocols allow for rapid and appropriate response to hemorrhages exceeding 1,500 mL of blood loss. The National Partnership for Maternal Safety has developed an obstetric hemorrhage consensus bundle of 13 patient- and systems-level recommendations to reduce morbidity and mortality from postpartum hemorrhage.

Use of oxytocin after delivery of the anterior shoulder is the most important and effective component of this practice. Oxytocin is more effective than misoprostol for prevention and treatment of uterine atony and has fewer adverse effects. Routine episiotomy should be avoided to decrease blood loss and the risk of anal laceration. Appropriate management of postpartum hemorrhage requires prompt diagnosis and treatment. The Four T's mnemonic can be used to identify and address the four most common causes of postpartum hemorrhage (uterine atony [Tone]; laceration, hematoma, inversion, rupture [Trauma]; retained tissue or invasive placenta [Tissue]; and coagulopathy [Thrombin]). Rapid team-based care minimizes morbidity and mortality associated with postpartum hemorrhage, regardless of cause. Massive transfusion protocols allow for rapid and appropriate response to hemorrhages exceeding 1,500 mL of blood loss. The National Partnership for Maternal Safety has developed an obstetric hemorrhage consensus bundle of 13 patient- and systems-level recommendations to reduce morbidity and mortality from postpartum hemorrhage.

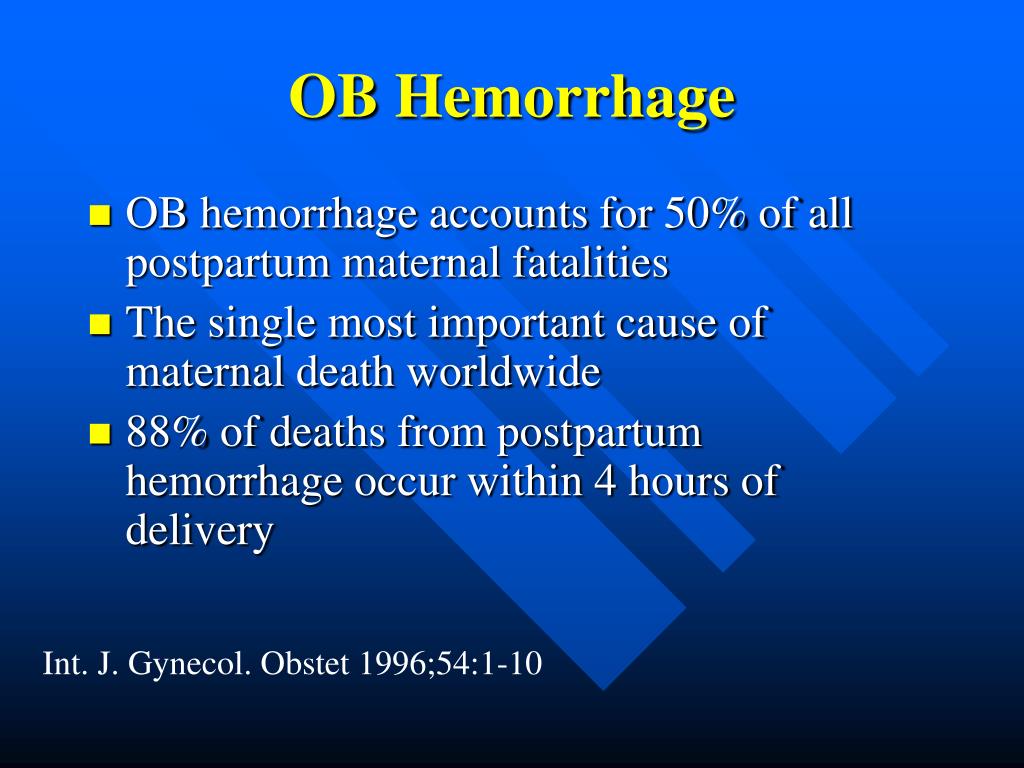

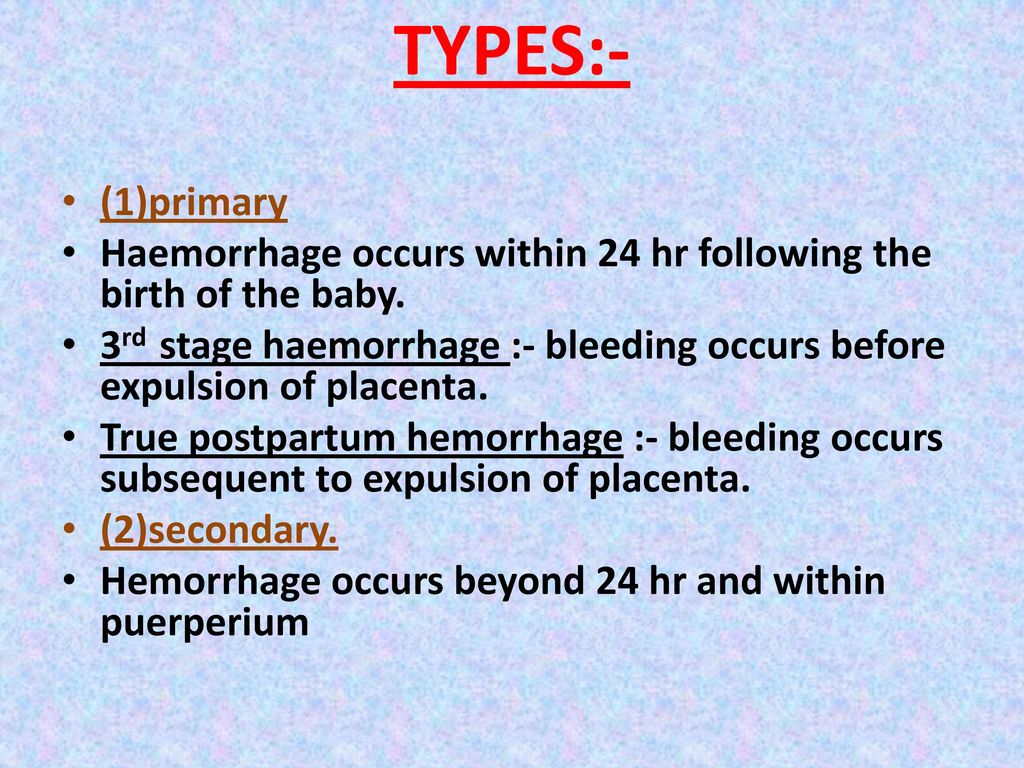

Approximately 3% to 5% of obstetric patients will experience postpartum hemorrhage.1 Annually, these preventable events are the cause of one-fourth of maternal deaths worldwide and 12% of maternal deaths in the United States.2,3 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists defines early postpartum hemorrhage as at least 1,000 mL total blood loss or loss of blood coinciding with signs and symptoms of hypovolemia within 24 hours after delivery of the fetus or intrapartum loss.4,5 Primary postpartum hemorrhage may occur before delivery of the placenta and up to 24 hours after delivery of the fetus. Complications of postpartum hemorrhage are listed in Table 13,6,7; these range from worsening of common postpartum symptoms such as fatigue and depressed mood, to death from cardiovascular collapse.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Routinely use active management of the third stage of labor, preferably with oxytocin (Pitocin). This practice will decrease the risks of postpartum hemorrhage and a postpartum maternal hemoglobin level lower than 9 g per dL (90 g per L), and reduce the need for manual removal of the placenta. | A | 11, 12, 16, 18 |

| Oxytocin is the most effective treatment for postpartum hemorrhage, even if already used for labor induction or augmentation or as part of active management of the third stage of labor. | A | 8, 23, 24 |

In women with postpartum hemorrhage, tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron) given within the first three hours after birth reduces mortality due to bleeding, but not overall mortality. | B | 25 |

| Avoid routine episiotomy, which increases the risk of blood loss and anal sphincter tears, unless urgent delivery is necessary and the perineum is thought to be a limiting factor. | A | 26 |

| When needed, use massive transfusion protocols to decrease the risk of dilutional coagulopathy and other postpartum hemorrhage complications. | C | 7, 39 |

| Interdisciplinary team training with realistic simulation should be used to improve perinatal safety. | C | 47, 48 |

| Anemia |

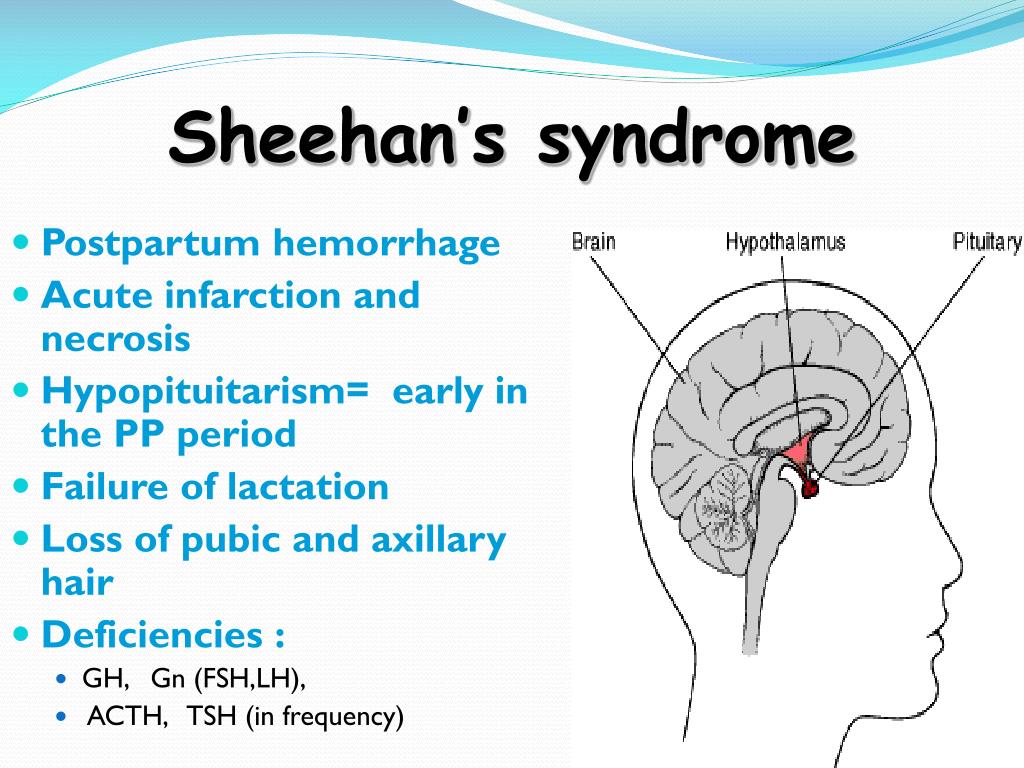

Anterior pituitary ischemia with delay or failure of lactation (i. e., Sheehan syndrome or postpartum pituitary necrosis) e., Sheehan syndrome or postpartum pituitary necrosis) |

| Blood transfusion |

| Death |

| Dilutional coagulopathy |

| Fatigue |

| Myocardial ischemia |

| Orthostatic hypotension |

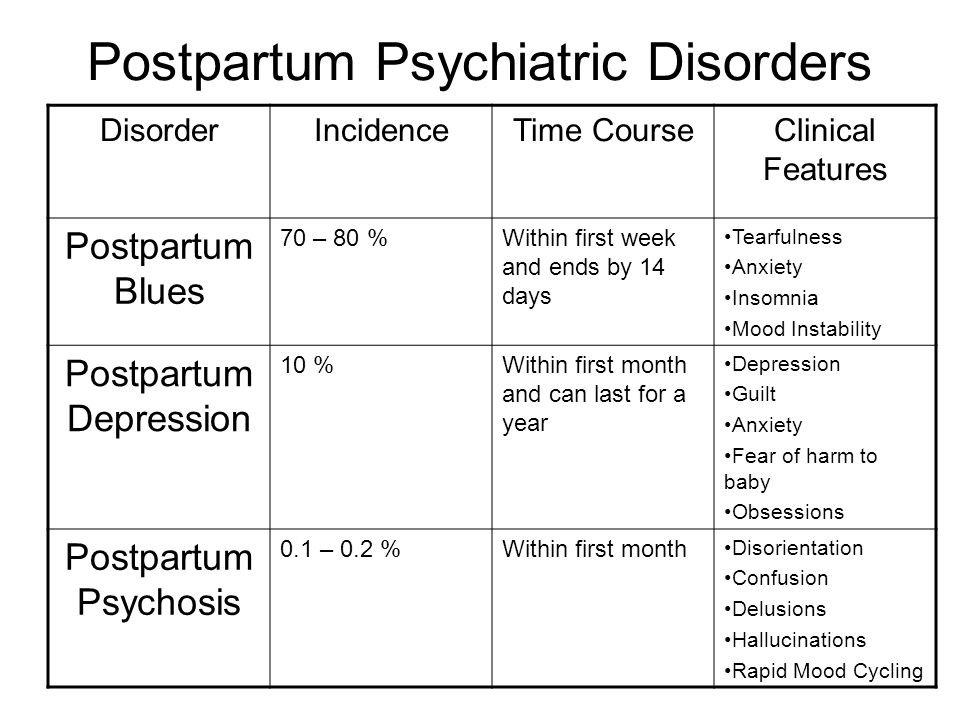

| Postpartum depression |

This review presents evidence-based recommendations for the prevention of and appropriate response to postpartum hemorrhage and is intended for physicians who provide antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care.

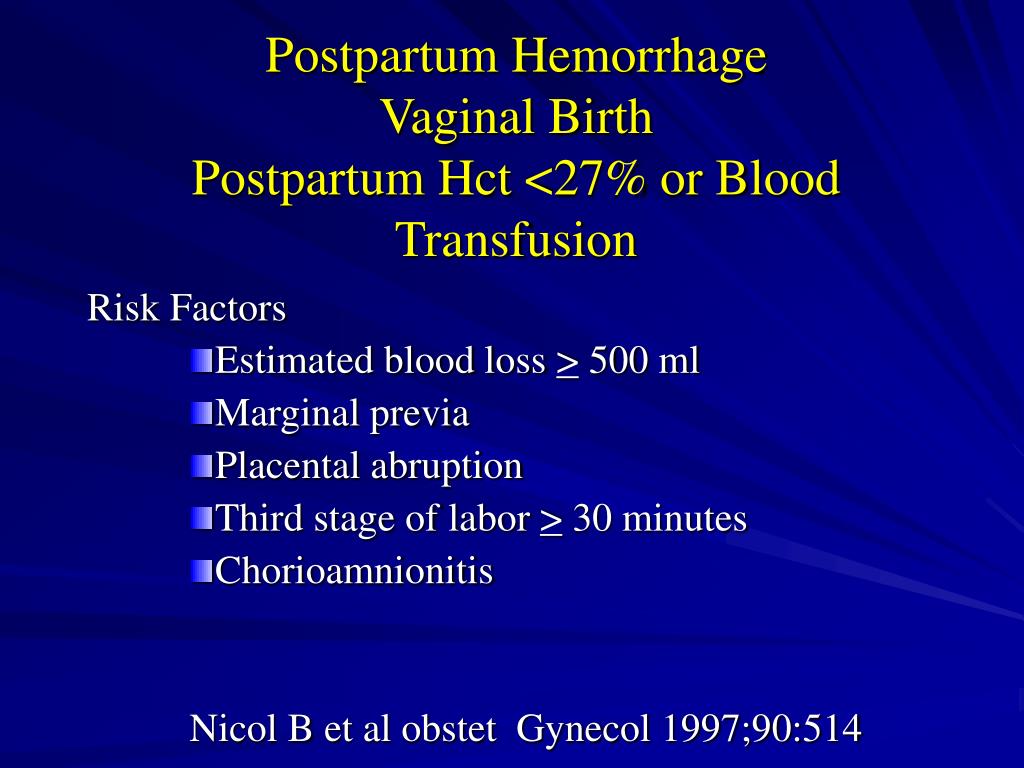

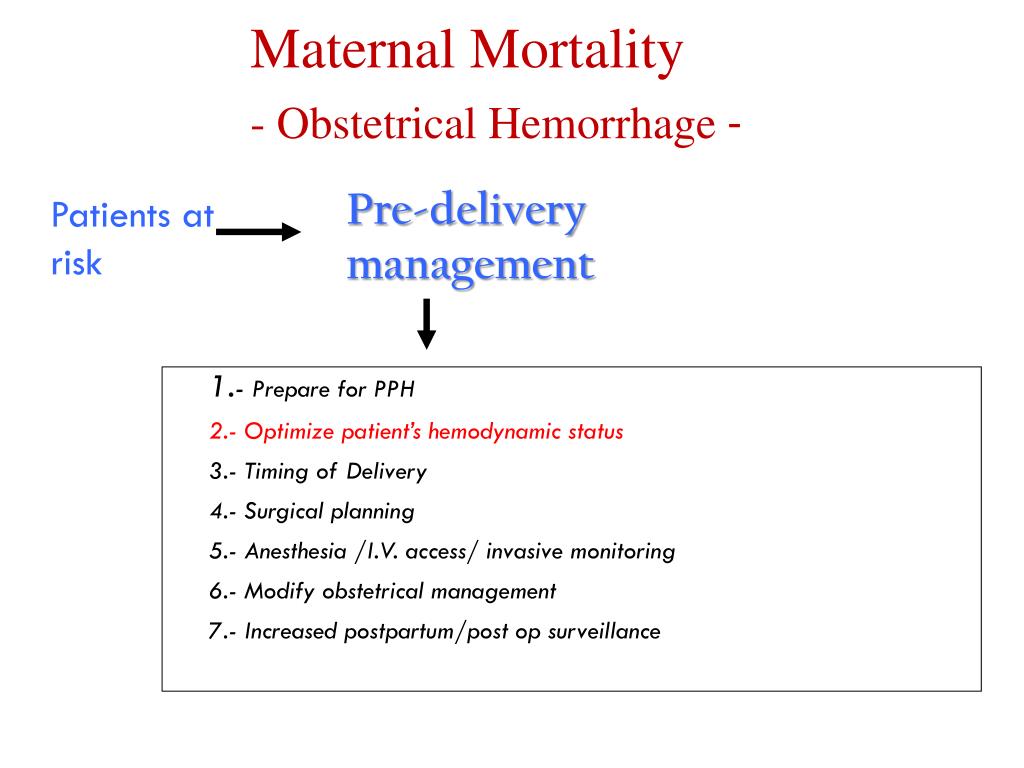

Prevention

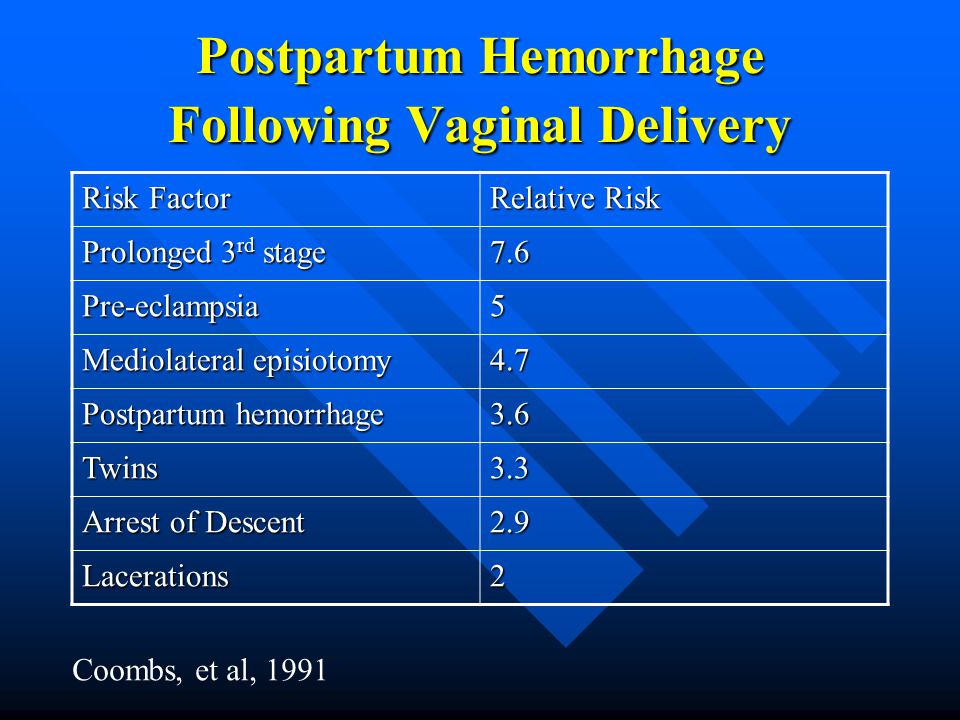

Risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage are listed in Table 2.8 However, 20% of postpartum hemorrhage occurs in women with no risk factors, so physicians must be prepared to manage this condition at every delivery.9 Strategies for decreasing the morbidity and mortality associated with postpartum hemorrhage are listed in Table 3,6,10–14 including the choice to deliver infants in women at high risk of hemorrhage at facilities with immediately available surgical, intensive care, and blood bank services.

| Antepartum hemorrhage |

| Augmented labor |

| Chorioamnionitis |

| Fetal macrosomia |

| Maternal anemia |

| Maternal obesity |

| Multifetal gestation |

| Preeclampsia |

| Primiparity |

| Prolonged labor |

| Readiness by every unit | |

| Have a hemorrhage cart with medications, supplies, checklist, and instruction cards immediately available | |

| Establish a response team and know who to call when help is needed | |

| Establish massive and emergency release transfusion protocols | |

| Institute unit education on protocols and run unit-based drills | |

| Recognition and prevention efforts for every patient | |

| Antenatal assessment | |

| Screen for and treat anemia antenatally | |

| Screen for sickle cell disease and thalassemia in women of African, Southeast Asian, or Mediterranean descent | |

| Obtain sonograms for women at high risk of invasive placenta | |

| Perform delivery in facility with blood bank and in-house surgical services if the patient has a high risk of hemorrhage | |

| Identify Jehovah's Witnesses and other patients who decline blood products | |

| Intrapartum management | |

| Use active management of the third stage of labor in every delivery | |

| Avoid routine episiotomy | |

| Avoid instrumented deliveries, especially forceps | |

| Use perineal warm compresses | |

| Measure cumulative blood loss and track postpartum vital signs | |

| Response for every hemorrhage | |

| Use an emergency management plan with checklists | |

| Provide support program for patients, families, and staff | |

| Reporting and systems learning for every unit | |

| Establish a culture of huddles and postevent debriefs | |

| Complete a multidisciplinary review for systems issues | |

| Establish a perinatal quality improvement committee | |

The most effective strategy to prevent postpartum hemorrhage is active management of the third stage of labor (AMTSL). AMTSL also reduces the risk of a postpartum maternal hemoglobin level lower than 9 g per dL (90 g per L) and the need for manual removal of the placenta.11 Components of this practice include: (1) administering oxytocin (Pitocin) with or soon after the delivery of the anterior shoulder; (2) controlled cord traction (Brandt-Andrews maneuver) to deliver the placenta; and (3) uterine massage after delivery of the placenta.11 Placental delivery can be achieved using the Brandt-Andrews maneuver, in which firm traction on the umbilical cord is applied with one hand while the other applies suprapubic counterpressure15(eFigure A).

AMTSL also reduces the risk of a postpartum maternal hemoglobin level lower than 9 g per dL (90 g per L) and the need for manual removal of the placenta.11 Components of this practice include: (1) administering oxytocin (Pitocin) with or soon after the delivery of the anterior shoulder; (2) controlled cord traction (Brandt-Andrews maneuver) to deliver the placenta; and (3) uterine massage after delivery of the placenta.11 Placental delivery can be achieved using the Brandt-Andrews maneuver, in which firm traction on the umbilical cord is applied with one hand while the other applies suprapubic counterpressure15(eFigure A).

The individual components of AMTSL have been evaluated and compared. Based on existing evidence, the most important component is administration of a uterotonic drug, preferably oxytocin.12,16 The number needed to treat to prevent one case of hemorrhage 500 mL or greater is 7 for oxytocin administered after delivery of the fetal anterior shoulder or after delivery of the neonate compared with placebo. 16 The risk of postpartum hemorrhage is also reduced if oxytocin is administered after placental delivery instead of at the time of delivery of the anterior shoulder.17 Dosing instructions are provided in Table 4.6

16 The risk of postpartum hemorrhage is also reduced if oxytocin is administered after placental delivery instead of at the time of delivery of the anterior shoulder.17 Dosing instructions are provided in Table 4.6

| Medication | Dosage | Prevention | Treatment | Contraindications and cautions | Mechanism of action | Adverse effects | Cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-line agent | |||||||

| Oxytocin (Pitocin) | Prevention: 10 IU IM or 5 to 10 IU IV bolus | + | + | Overdose or prolonged use can cause water intoxication | Stimulates the upper segment of the myometrium to contract rhythmically, constricting spiral arteries and decreasing blood flow through the uterus | Rare | $1 ($13) for 10 units of injectable solution |

| Treatment: 20 to 40 IU in 1 L normal saline, infuse 500 mL over 10 minutes then 250 mL per hour | Possible hypotension with IV use following cesarean delivery | ||||||

| Second-line agents | |||||||

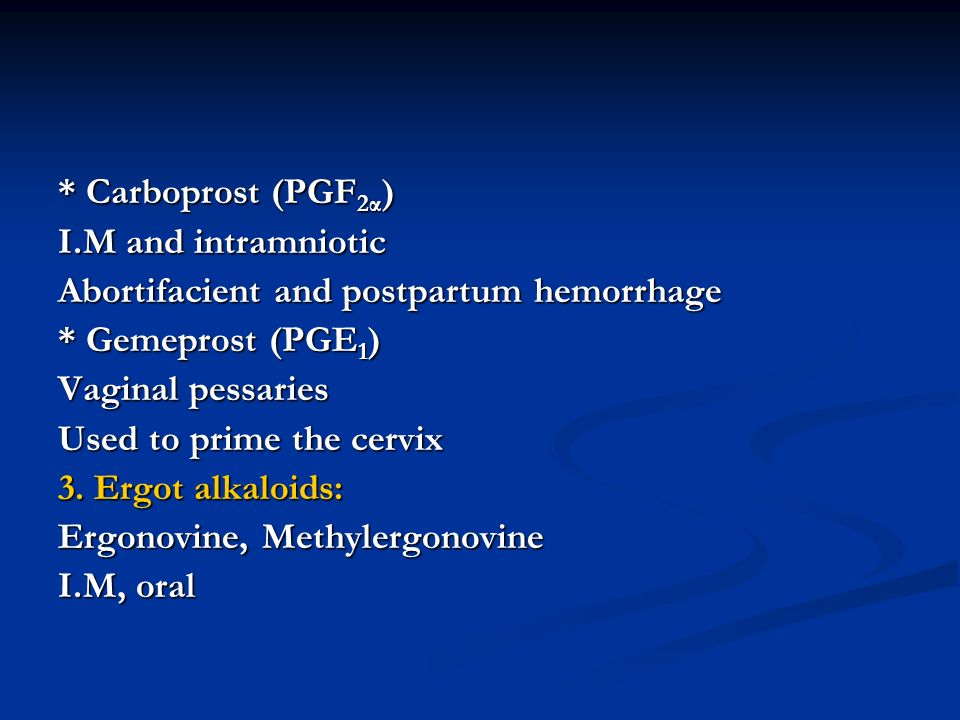

| Carboprost (Hemabate), a prostaglandin F2-alpha analogue | 250 mcg IM or into myometrium, repeated every 15 to 90 minutes for a total dose of 2 mg | – | + | Avoid in patients with asthma or significant renal, hepatic, or cardiac disease | Improves uterine contractility by increasing the number of oxytocin receptors and causes vasoconstriction | Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea | NA ($270) for 250 mcg of injectable solution |

| Methylergonovine (Methergine) | 0. | – | + | Avoid in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including chronic hypertension | Causes vasoconstriction and contracts smooth muscles and upper and lower Segments of the uterus tetanically | Nausea, vomiting, and increased blood pressure | $9 (NA) for 0.2 mg of injectable solution |

| Use with caution in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection who are receiving protease inhibitors | |||||||

| Misoprostol (Cytotec),† a prostaglandin E1 analogue | Prevention: 600 mcg orally Treatment: 800 to 1,000 mcg rectally or 600 to 800 mcg sublingually or orally | Use only when oxytocin is not available | + | Use with caution in patients with cardiovascular disease | Causes generalized smooth muscle contraction | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, pyrexia, and shivering | $1 ($5) per 200-mcg tablet |

| Tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron)† | 1 g intravenously over 10 minutes, may be repeated after 30 minutes | – | + | Use within three hours of onset of bleeding | Inhibits breakdown of fibrin and fibrinogen by plasmin | May increase risk of thrombosis and cause visual defects | $24 ($50) |

| Use with caution in patients with renal impairment and with other clotting factors such as prothrombin complex concentrate | |||||||

An alternative to oxytocin is misoprostol (Cytotec), an inexpensive medication that does not require injection and is more effective than placebo in preventing postpartum hemorrhage. 12 However, most studies have shown that oxytocin is superior to misoprostol.12,18 Misoprostol also causes more adverse effects than oxytocin—commonly nausea, diarrhea, and fever within three hours of birth.12,18

12 However, most studies have shown that oxytocin is superior to misoprostol.12,18 Misoprostol also causes more adverse effects than oxytocin—commonly nausea, diarrhea, and fever within three hours of birth.12,18

The benefits of controlled cord traction and uterine massage in preventing postpartum hemorrhage are less clear, but these strategies may be helpful.15,19,20 Controlled cord traction does not prevent severe postpartum hemorrhage, but reduces the incidence of less severe blood loss (500 to 1,000 mL) and reduces the need for manual extraction of the placenta.21

Diagnosis and Management

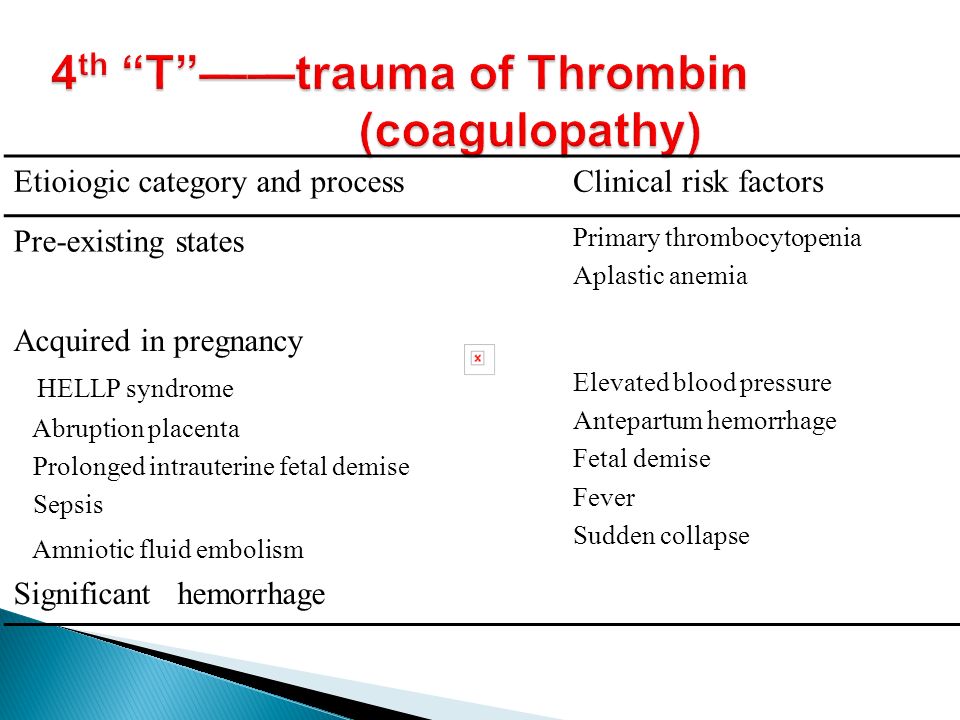

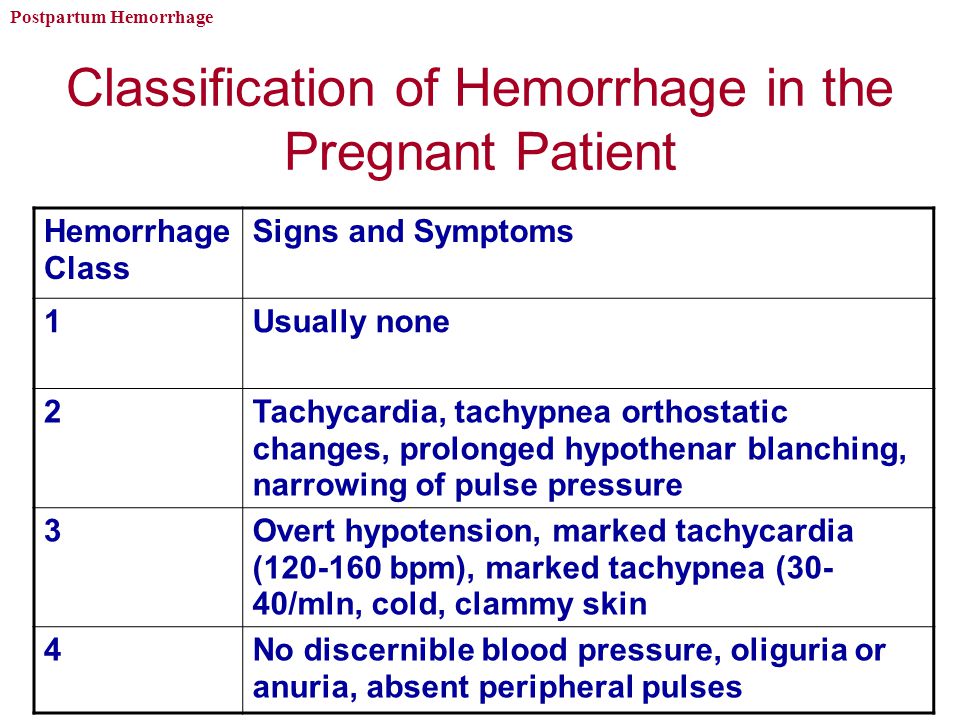

Diagnosis of postpartum hemorrhage begins with recognition of excessive bleeding and targeted examination to determine its cause (Figure 16). Cumulative blood loss should be monitored throughout labor and delivery and postpartum with quantitative measurement, if possible.22 Although some important sources of blood loss may occur intrapartum (e. g., episiotomy, uterine rupture), most of the fluid expelled during delivery of the infant is urine or amniotic fluid. Quantitative measurement of postpartum bleeding begins immediately after the birth of the infant and entails measuring cumulative blood loss with a calibrated underbuttocks drape, or by weighing blood-soaked pads, sponges, and clots; combined use of these methods is also appropriate for obtaining an accurate measurement.22 Healthy pregnant women can typically tolerate 500 to 1,000 mL of blood loss without having signs or symptoms.9 Tachycardia may be the earliest sign of postpartum hemorrhage. Orthostasis, hypotension, nausea, dyspnea, oliguria, and chest pain may indicate hypovolemia from significant hemorrhage. If excess bleeding is diagnosed, the Four T's mnemonic (uterine atony [Tone]; laceration, hematoma, inversion, rupture [Trauma]; retained tissue or invasive placenta [Tissue]; and coagulopathy [Thrombin]) can be used to identify specific causes (Table 56).

g., episiotomy, uterine rupture), most of the fluid expelled during delivery of the infant is urine or amniotic fluid. Quantitative measurement of postpartum bleeding begins immediately after the birth of the infant and entails measuring cumulative blood loss with a calibrated underbuttocks drape, or by weighing blood-soaked pads, sponges, and clots; combined use of these methods is also appropriate for obtaining an accurate measurement.22 Healthy pregnant women can typically tolerate 500 to 1,000 mL of blood loss without having signs or symptoms.9 Tachycardia may be the earliest sign of postpartum hemorrhage. Orthostasis, hypotension, nausea, dyspnea, oliguria, and chest pain may indicate hypovolemia from significant hemorrhage. If excess bleeding is diagnosed, the Four T's mnemonic (uterine atony [Tone]; laceration, hematoma, inversion, rupture [Trauma]; retained tissue or invasive placenta [Tissue]; and coagulopathy [Thrombin]) can be used to identify specific causes (Table 56). Regardless of the cause of bleeding, physicians should immediately summon additional personnel and begin appropriate emergency hemorrhage protocols.

Regardless of the cause of bleeding, physicians should immediately summon additional personnel and begin appropriate emergency hemorrhage protocols.

| Pathology | Specific cause | Approximate incidence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Tone | Atonic uterus | 70 |

| Trauma | Lacerations, hematomas, inversion, rupture | 20 |

| Tissue | Retained tissue, invasive placenta | 10 |

| Thrombin | Coagulopathies | 1 |

TONE (UTERINE ATONY)

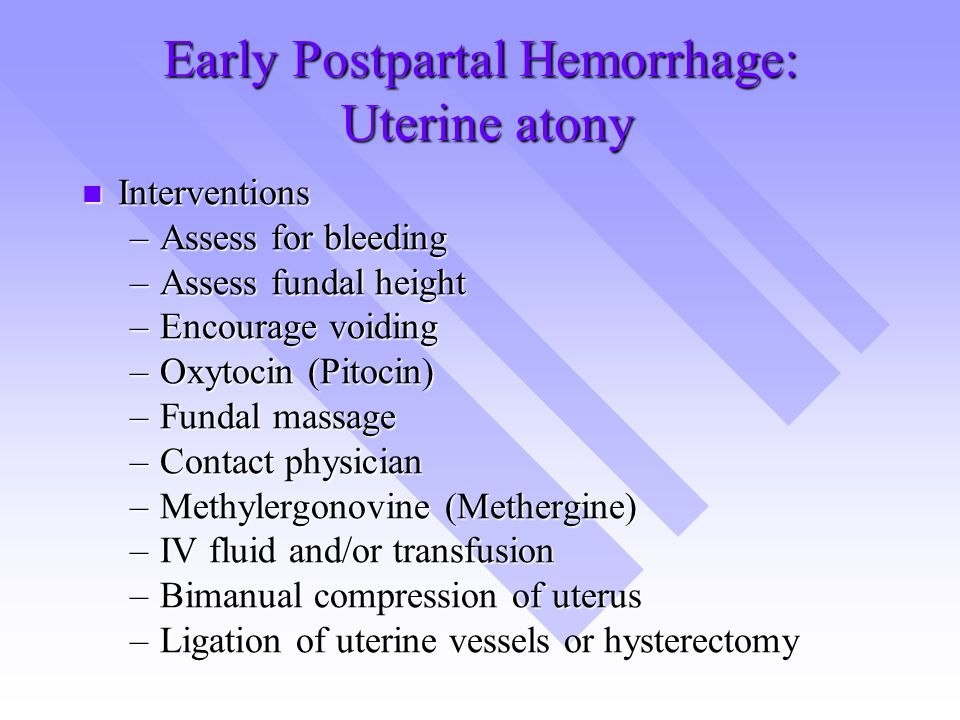

Uterine atony is the most common cause of postpartum hemorrhage. 9 Brisk blood flow after delivery of the placenta unresponsive to transabdominal massage should prompt immediate action including bimanual compression of the uterus and use of uterotonic medications (Table 46). Massage is performed by placing one hand in the vagina and pushing against the body of the uterus while the other hand compresses the fundus from above through the abdominal wall (eFigure B).

9 Brisk blood flow after delivery of the placenta unresponsive to transabdominal massage should prompt immediate action including bimanual compression of the uterus and use of uterotonic medications (Table 46). Massage is performed by placing one hand in the vagina and pushing against the body of the uterus while the other hand compresses the fundus from above through the abdominal wall (eFigure B).

Uterotonic agents include oxytocin, ergot alkaloids, and prostaglandins. Oxytocin is the most effective treatment for postpartum hemorrhage, even if already used for labor induction or augmentation or as part of AMTSL.8,23,24 The choice of a second-line uterotonic should be based on patient-specific factors such as hypertension, asthma, or use of protease inhibitors. Although it is not a uterotonic, tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron) may reduce mortality due to bleeding from postpartum hemorrhage (but not overall mortality) when given within the first three hours and may be considered as an adjuvant therapy. 25[updated] Table 4 outlines dosages, cautions, contraindications, and common adverse effects of uterotonic medications and tranexamic acid.6

25[updated] Table 4 outlines dosages, cautions, contraindications, and common adverse effects of uterotonic medications and tranexamic acid.6

TRAUMA

Lacerations and hematomas due to birth trauma can cause significant blood loss that can be lessened by hemostasis and timely repair. Episiotomy increases the risk of blood loss and anal sphincter tears; this procedure should be avoided unless urgent delivery is necessary and the perineum is thought to be a limiting factor.26

Vaginal and vulvar hematomas can present as pain or as a change in vital signs disproportionate to the amount of blood loss. Small hematomas can be managed with ice packs, analgesia, and observation. Patients with persistent signs of volume loss despite fluid replacement, as well as those with large (greater than 3 to 4 cm) or enlarging hematomas, require incision and evacuation of the clot.27 The involved area should be irrigated and hemostasis achieved by ligating bleeding vessels, placing figure-of-eight sutures, and creating a layered closure, or by using any of these methods alone.

Uterine inversion is rare, occurring in only 0.04% of deliveries, and is a potential cause of postpartum hemorrhage.27 AMTSL does not appear to increase the incidence of uterine inversion, but invasive placenta does.27,28 The contributions of other conditions such as fundal implantation of the placenta, fundal pressure, and undue cord traction are unclear.27 The inverted uterus usually appears as a bluish-gray mass protruding from the vagina. Patients with uterine inversion may have signs of shock without excess blood loss. If the placenta is attached, it should be left in place until after reduction to limit hemorrhage.27 Every attempt should be made to quickly replace the uterus. The Johnson method of reduction begins with grasping the protruding fundus with the palm of the hand, directing the fingers toward the posterior fornix.27 The uterus is returned to position by lifting it up through the pelvis and into the abdomen (eFigure C). Once the uterus is reverted, uterotonic agents can promote uterine tone and prevent recurrence. If initial attempts to replace the uterus fail or contraction of the lower uterine segment (contraction ring) develops, the use of magnesium sulfate, terbutaline, nitroglycerin, or general anesthesia may allow sufficient uterine relaxation for manipulation.28

Once the uterus is reverted, uterotonic agents can promote uterine tone and prevent recurrence. If initial attempts to replace the uterus fail or contraction of the lower uterine segment (contraction ring) develops, the use of magnesium sulfate, terbutaline, nitroglycerin, or general anesthesia may allow sufficient uterine relaxation for manipulation.28

Uterine rupture can cause intrapartum and postpartum hemorrhage.29 Although rare in an unscarred uterus, clinically significant uterine rupture occurs in 0.8% of vaginal births after cesarean delivery via low transverse uterine incision.30 Induction and augmentation increase the risk of uterine rupture, especially for patients with prior cesarean delivery.31 Before delivery, the primary sign of uterine rupture is fetal bradycardia.31,32 Other signs and symptoms of uterine rupture are listed in eTable A.

| Abdominal tenderness |

| Circulatory collapse |

| Elevation of presenting fetal part |

| Fetal bradycardia* |

| Increasing abdominal girth |

| Loss of uterine contractions |

| Maternal tachycardia |

| Vaginal bleeding |

TISSUE

Retained tissue (i. e., placenta, placental fragments, or blood clots) prevents the uterus from contracting enough to achieve optimal tone. Classic signs of placental separation include a small gush of blood, lengthening of the umbilical cord, and a slight rise of the uterus. The mean time from delivery to placental expulsion is eight to nine minutes.33 Longer intervals are associated with an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage, with rates doubling after 10 minutes.33 Retained placenta (i.e., failure of the placenta to deliver within 30 minutes) occurs in less than 3% of vaginal deliveries.34,35 If the placenta is retained, consider manual removal using appropriate analgesia.35 Injecting the umbilical vein with saline and oxytocin does not clearly reduce the need for manual removal.35–37 If blunt dissection with the edge of the gloved hand does not reveal the tissue plane between the uterine wall and placenta, invasive placenta should be considered.

e., placenta, placental fragments, or blood clots) prevents the uterus from contracting enough to achieve optimal tone. Classic signs of placental separation include a small gush of blood, lengthening of the umbilical cord, and a slight rise of the uterus. The mean time from delivery to placental expulsion is eight to nine minutes.33 Longer intervals are associated with an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage, with rates doubling after 10 minutes.33 Retained placenta (i.e., failure of the placenta to deliver within 30 minutes) occurs in less than 3% of vaginal deliveries.34,35 If the placenta is retained, consider manual removal using appropriate analgesia.35 Injecting the umbilical vein with saline and oxytocin does not clearly reduce the need for manual removal.35–37 If blunt dissection with the edge of the gloved hand does not reveal the tissue plane between the uterine wall and placenta, invasive placenta should be considered.

Invasive placenta (placenta accreta, increta, or percreta) can cause life-threatening postpartum hemorrhage.13,34,35 The incidence has increased with time, mirroring the increase in cesarean deliveries.13,34 In addition to prior cesarean delivery, other risk factors for invasive placenta include placenta previa, advanced maternal age, high parity, and previous invasive placenta.13,34 Treatment of invasive placenta can require hysterectomy or, in select cases, conservative management (i.e., leaving the placenta in place or giving weekly oral methotrexate).13

THROMBIN (COAGULATION DEFECTS)

Coagulation defects can cause a hemorrhage or be the result of one. These defects should be suspected in patients who have not responded to the usual measures to treat postpartum hemorrhage or who are oozing from puncture sites. A coagulation defect should also be suspected if blood does not clot in bedside receptacles or red-top (no additives) laboratory collection tubes within five to 10 minutes. Coagulation defects may be congenital or acquired (eTable B). Evaluation should include a platelet count and measurement of prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen level, fibrin split products, and quantitative d-dimer assay. Physicians should treat the underlying disease process, if known, and support intravascular volume, serially evaluate coagulation status, and replace appropriate blood components using an emergency release protocol to improve response time and decrease risk of dilutional coagulopathy.7,38,39 [updated]

Coagulation defects may be congenital or acquired (eTable B). Evaluation should include a platelet count and measurement of prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen level, fibrin split products, and quantitative d-dimer assay. Physicians should treat the underlying disease process, if known, and support intravascular volume, serially evaluate coagulation status, and replace appropriate blood components using an emergency release protocol to improve response time and decrease risk of dilutional coagulopathy.7,38,39 [updated]

| Acquired |

| Amniotic fluid embolism |

| Consumptive coagulation secondary to excessive bleeding of any origin |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation secondary to abruption |

| Fetal demise |

| HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzyme levels, and low platelet levels) syndrome |

| Placental abruption |

| Preeclampsia with severe features |

| Sepsis |

| Use of anticoagulants such as aspirin or heparin |

| Chronic or congenital |

| Hemophilia |

| Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura |

| Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura |

| Von Willebrand disease |

Ongoing or Severe Hemorrhage

Significant blood loss from any cause requires immediate resuscitation measures using an interdisciplinary, stage-based team approach. Physicians should perform a primary maternal survey and institute care based on American Heart Association standards and an assessment of blood loss.14,40 Patients should be given oxygen, ventilated as needed, and provided intravenous fluid and blood replacement with normal saline or other crystalloid fluids administered through two large-bore intravenous needles. Fluid replacement volume should initially be given as a bolus infusion and subsequently adjusted based on frequent reevaluation of the patient's vital signs and symptoms. The use of O negative blood may be needed while waiting for type-specific blood.

Physicians should perform a primary maternal survey and institute care based on American Heart Association standards and an assessment of blood loss.14,40 Patients should be given oxygen, ventilated as needed, and provided intravenous fluid and blood replacement with normal saline or other crystalloid fluids administered through two large-bore intravenous needles. Fluid replacement volume should initially be given as a bolus infusion and subsequently adjusted based on frequent reevaluation of the patient's vital signs and symptoms. The use of O negative blood may be needed while waiting for type-specific blood.

Elevating the patient's legs will improve venous return. Draining the bladder with a Foley catheter may improve uterine atony and will allow monitoring of urine output. Massive transfusion protocols to decrease the risk of dilutional coagulopathy and other postpartum hemorrhage complications have been established. These protocols typically recommend the use of four units of fresh frozen plasma and one unit of platelets for every four to six units of packed red blood cells used. 7,39

7,39

Uterus-conserving treatments include uterine packing (plain gauze or gauze soaked with vasopressin, chitosan, or carboprost [Hemabate]), artery ligation, uterine artery embolization, B-lynch compression sutures, and balloon tamponade.7,41–43 Balloon tamponade (in which direct pressure is applied to potential bleeding sites via a balloon that is inserted through the vagina and cervix and inflated with sterile water or saline), uterine packing, aortic compression, and nonpneumatic antishock garments may be used to limit bleeding while definitive treatment or transport is arranged.7,41,44 Hysterectomy is the definitive treatment in women with severe, intractable hemorrhage.

Follow-up of postpartum hemorrhage includes monitoring for ongoing blood loss and vital signs, assessing for signs of anemia (fatigue, shortness of breath, chest pain, or lactation problems), and debriefing with patients and staff. Many patients experience acute and posttraumatic stress disorders after a traumatic delivery. Individual, trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy can be offered to reduce acute traumatic stress symptoms.45 Debriefing with staff may identify necessary systems-level changes (Table 3).6,10–14

Individual, trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy can be offered to reduce acute traumatic stress symptoms.45 Debriefing with staff may identify necessary systems-level changes (Table 3).6,10–14

Systems Approach to Prevention and Treatment

Complications of postpartum hemorrhage are common, even in high-resource countries and well-staffed delivery suites. Based on an analysis of systems errors identified in The Joint Commission's 2010 Sentinel Event Alert, the commission recommended that hospitals establish protocols to enable an optimal response to changes in maternal vital signs and clinical condition. These protocols should be tested in drills, and systems problems that interfere with care should be fixed through their continual refinement.46 In response, The Council on Patient Safety in Women's Health Care outlined essential steps that delivery units should take to decrease the incidence and severity of postpartum hemorrhage14(Table 36,10–14). The creation of a hemorrhage cart with supplies, and the use of huddles, rapid response teams, and massive transfusion protocols are among the recommendations. Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics (ALSO) training can be part of a systems approach to improving patient care. The use of interdisciplinary team training with in situ simulation, available through the ALSO program and from TeamSTEPPS (Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety), has been shown to improve perinatal safety.47,48

The creation of a hemorrhage cart with supplies, and the use of huddles, rapid response teams, and massive transfusion protocols are among the recommendations. Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics (ALSO) training can be part of a systems approach to improving patient care. The use of interdisciplinary team training with in situ simulation, available through the ALSO program and from TeamSTEPPS (Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety), has been shown to improve perinatal safety.47,48

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key term postpartum hemorrhage. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Also searched were the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Essential Evidence Plus, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reports, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, and the National Guideline Clearinghouse. Search dates: October 12, 2015, and January 19, 2016.

Search dates: October 12, 2015, and January 19, 2016.

This article is one in a series on “Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics (ALSO),” initially established by Mark Deutchman, MD, Denver, Colo. The coordinator of this series is Larry Leeman, MD, MPH, ALSO Managing Editor, Albuquerque, N.M.

Sitemap

|

|

On the classification of postpartum hemorrhage: an invitation to discussion | Dobrokhotova Yu.

E., Kozlov P.V., Seliverstova O.M.

E., Kozlov P.V., Seliverstova O.M. On the classification of postpartum haemorrhage: an invitation to discussion

May 25, 2018

Share material print Add to favorites- Dobrokhotova Yu.E. 1 ,

- Kozlov P.V. 1 ,

- Seliverstova O.M. 2

one

RNIMU them. N.I. Pirogov of the Ministry of Health of Russia, Moscow, Russia

N.I. Pirogov of the Ministry of Health of Russia, Moscow, Russia

2

Russian National Research Medical University named after N. I. Pirogov Ministry of Health of Russia, Moscow

Obstetric haemorrhage remains the leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality worldwide. The article provides information on the classifications of postpartum hemorrhage adopted by international professional communities and in the Russian Federation. Most professional organizations, including the International Federation of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, recommend classifying postpartum hemorrhage as early (primary), occurring within the first 24 hours after birth, and late (secondary), occurring between 24 hours and 6 weeks. after childbirth. In the United States, the period of late postpartum hemorrhage has been increased to 12 weeks. A discussion was proposed on the advisability of clarifying the classification of postpartum hemorrhage adopted in the Russian Federation in terms of etiology and regulated algorithms for obstetric management of postpartum hemorrhage. The necessity of increasing the period of early postpartum hemorrhage up to 24 hours and the period of late postpartum hemorrhage from 24 hours to 6 weeks is considered, which will bring the domestic classification into line with the etiology of postpartum hemorrhage, obstetric management tactics and accepted international standards.

after childbirth. In the United States, the period of late postpartum hemorrhage has been increased to 12 weeks. A discussion was proposed on the advisability of clarifying the classification of postpartum hemorrhage adopted in the Russian Federation in terms of etiology and regulated algorithms for obstetric management of postpartum hemorrhage. The necessity of increasing the period of early postpartum hemorrhage up to 24 hours and the period of late postpartum hemorrhage from 24 hours to 6 weeks is considered, which will bring the domestic classification into line with the etiology of postpartum hemorrhage, obstetric management tactics and accepted international standards.

Key words: postpartum hemorrhage, childbirth complications, early postpartum hemorrhage, late postpartum hemorrhage, classification.

On the classification of postpartum haemorrhages: an invitation to a discussion

Dobrokhotova Yu.E., Kozlov P. V., Seliverstova O.M.

V., Seliverstova O.M.

Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University, Moscow

Postpartum haemorrhages remain the leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality in the world. The article provides information on the classification of postpartum haemorrhages (PPH), adopted by international professional communities and

in the Russian Federation. Most professional societies, including the International Federation of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, recommend the classification of postpartum haemorrhages for early (primary) bleeding, which develop within the first 24 hours after delivery, and late (secondary) bleeding, which develop from 24 hours to 6 weeks after delivery. In the US, the time interval for late postpartum hemorrhage is increased up to 12 weeks. A discussion is proposed on the advisability of clarifying the classification of postpartum haemorrhages, from the point of view of etiology and approved algorithms of obstetric management of PPH. The need to increase the time interval in the classification of early postpartum hemorrhage to 24 hours and for late postpartum hemorrhages from 24 hours to 6 weeks is considered. Expansion of the interval and diagnosis of early postpartum haemorrhages will help to bring into compliance the domestic classification and the etiology of haemorrhages, obstetric tactics of management and accepted international standards.

Expansion of the interval and diagnosis of early postpartum haemorrhages will help to bring into compliance the domestic classification and the etiology of haemorrhages, obstetric tactics of management and accepted international standards.

Key words: postpartum haemorrhage, birth complications, early postpartum haemorrhage, late postpartum haemorrhage, classification.

For citation: Dobrokhotova Yu.E., Kozlov P.V., Seliverstova O.M. On the classification of postpartum haemorrhages:

an invitation to a discussion // RMJ. 2018. No. 5(I). P. 61–63.

Keywords:

For citation: Dobrokhotova Yu.E., Kozlov P.V., Seliverstova O.M. On the classification of postpartum hemorrhage: an invitation to discussion. breast cancer. Mother and child. 2018;26(5(I)):61-63.

The article provides information on the classifications of postpartum hemorrhage. A discussion was proposed on the advisability of clarifying the classification of postpartum hemorrhage adopted in the Russian Federation in terms of etiology and regulated algorithms for obstetric management of postpartum hemorrhage.

The successive period, completing the great act of the birth of a person, is the most serious for the mother the period of childbirth. G.G. Genter Obstetric hemorrhage remains the leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality worldwide. More than half of maternal deaths occur within 24 hours of childbirth. According to the WHO (2012), about 140,000 women a year die from postpartum hemorrhage, i.e., one woman every 4 minutes [1]. More than 80% in the structure of obstetric hemorrhage is occupied by postpartum hemorrhage. Measures for the prevention of bleeding and obstetric tactics in the world are defined [1-7] and do not have fundamental differences. However, the issue of classification of postpartum obstetric hemorrhage, in our opinion, requires clarification.

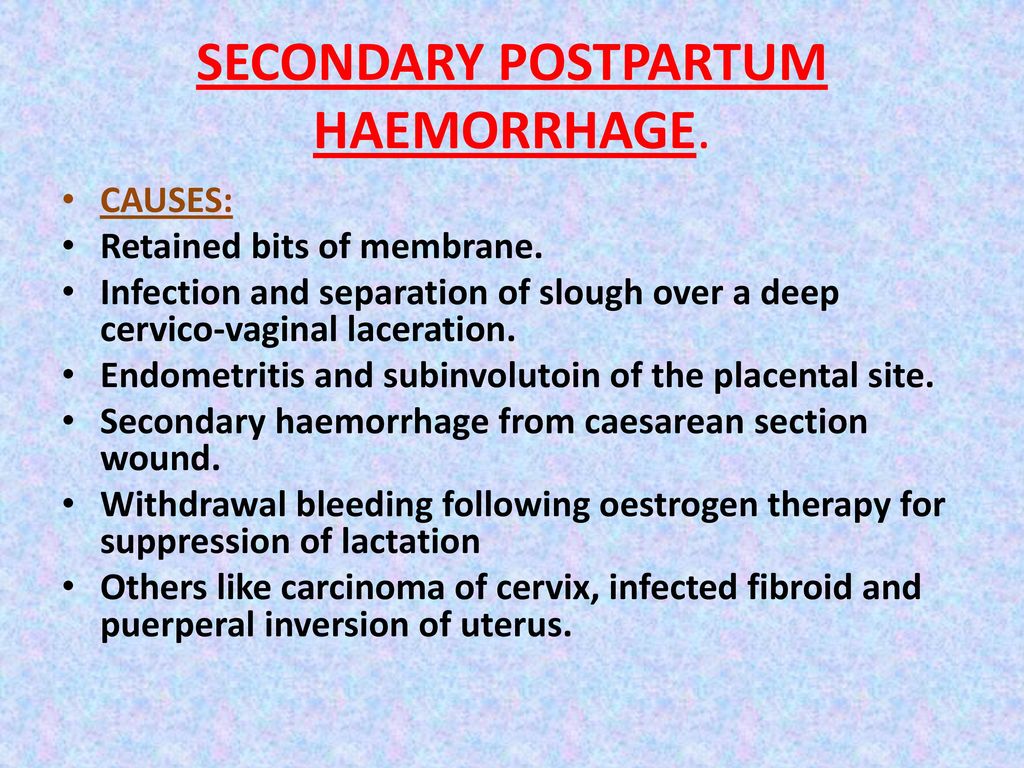

Many professional communities, including The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), recommend classifying postpartum hemorrhage into early (primary), realized within the first 24 hours after childbirth, and late (secondary) occurring between 24 hours and 6 weeks.

after childbirth [6–8].

after childbirth [6–8]. In the definition of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) [5], the period of late postpartum hemorrhage is increased to 12 weeks.

The causes of postpartum hemorrhage are fundamentally different. In the vast majority of cases, early postpartum hemorrhage (EPK) is directly related to the act of childbirth and is realized in the next few minutes (with external bleeding) or hours (in cases of formation of retroperitoneal hematomas, with defects in observation, etc.), usually within 24 hours. In 70-80% of cases, the causes of PKK are uterine atony, associated, in particular, with myometrial hyperextension, retention of placental tissue, uterine trauma, damage to the tissues of the birth canal and uterine eversion (very rare), as well as coagulopathy caused by congenital (primary) hemostasis defects or irrational use of anticoagulants.

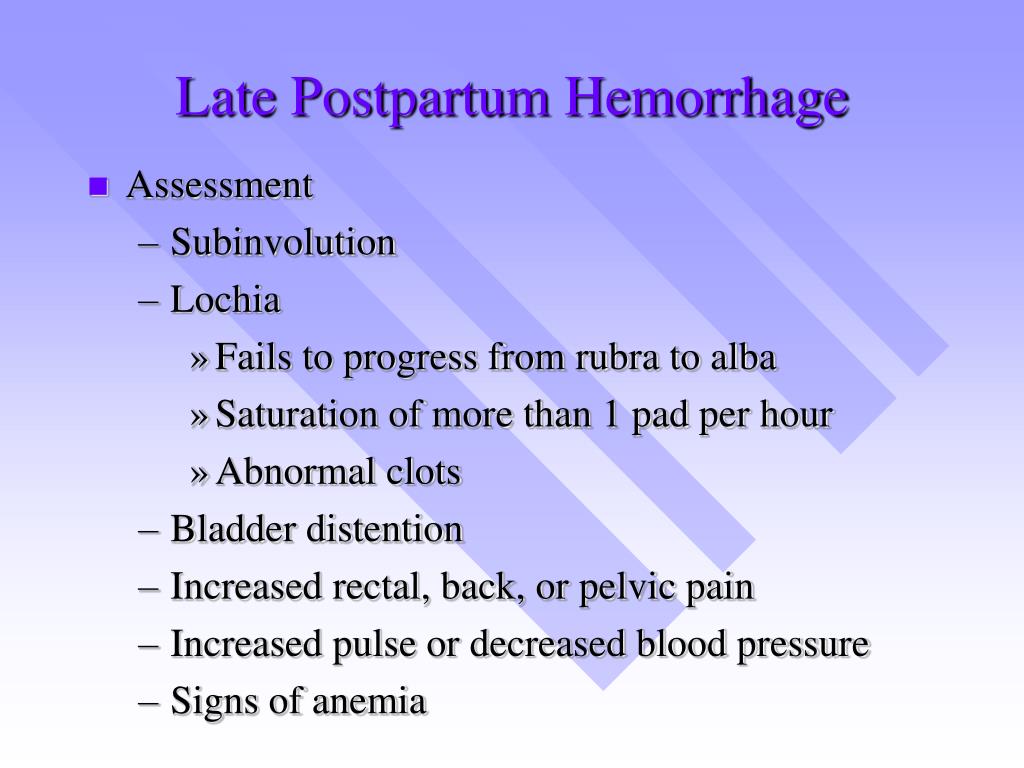

Late (secondary) postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) occurs, as a rule, not earlier than 2 days of the postpartum period and is associated with subinvolution of the placental bed against the background of an infectious process, retention of inflammatory detritus or placental tissues with the formation of placental polyps.

Thus, this classification is more etiological, since it implies the causes of postpartum hemorrhage.

Thus, this classification is more etiological, since it implies the causes of postpartum hemorrhage. In the Russian Federation, the classification of postpartum hemorrhage based on the time of their occurrence and referring PPH to the early postpartum period, which is 2 hours, and during vaginal delivery, as a rule, coincides with the patient's stay in the maternity ward, has become widespread. With the development of bleeding after 2 hours, i.e. after the transfer of the puerperal to the postpartum department, it is classified as later [3]. According to the order of the Ministry of Health of Russia No. 572n dated November 1, 2012 (as amended on January 12, 2016) “On approval of the Procedure for the provision of medical care in the field of obstetrics and gynecology (with the exception of the use of assisted reproductive technologies)” and the International Classification of Diseases of the 10th revision (ICD-10) postpartum haemorrhage (O.72) is classified both by time of occurrence (O72.

0 haemorrhage in the third stage of labour, O72.1 other haemorrhage in the early postpartum period) and by etiology (O72.2 late or secondary postpartum hemorrhage, O72.3 postpartum coagulation defect, afibrinogenemia, fibrinolysis).

0 haemorrhage in the third stage of labour, O72.1 other haemorrhage in the early postpartum period) and by etiology (O72.2 late or secondary postpartum hemorrhage, O72.3 postpartum coagulation defect, afibrinogenemia, fibrinolysis). Indeed, classifying postpartum hemorrhage according to the time of their occurrence, we mean the moment of diagnosis of blood loss. However, the causes of early and so-called "late" postpartum hemorrhages, realized, or rather diagnosed, within a few hours after delivery, are identical.

An obvious criterion for the early diagnosis of pathological blood loss is the amount of external bleeding. However, pathological blood loss is not always synonymous with external blood loss. So, with traumatic damage to the uterus with the formation of a retroperitoneal hematoma, external bleeding is insignificant and early diagnosis of pathological blood loss is difficult. In these cases, symptoms of blood loss and shock may take several hours to appear.

In cases of undiagnosed retention of part of the placenta or uterine injury, including rupture of the cervix with good contractile activity of the uterus, the amount of external bleeding may not be pronounced and pathological blood loss is diagnosed later, as a rule, with external massage of the uterus before transferring the puerperal to the postpartum department.

The reasons for the "belated" diagnosis of bleeding after caesarean section may be a violation of the evacuation of lochia and hyperdistension of the uterus, accompanied by a decrease in its contractile activity and an increase in volume. These cases of "late" bleeding, or rather untimely diagnosis, are, as a rule, a defect in observation, i.e., iatrogenic. Rarely, delivery by caesarean section may be complicated by the formation of a retroperitoneal hematoma and the development of shock and delayed bleeding associated with consumption coagulopathy.

Thus, if pathological blood loss is detected or realized more than 2 hours after delivery, bleeding is classified as late. However, from an etiological point of view, such bleeding is early, since the causes of its occurrence are directly related to the process of childbirth. According to our data, about 5% of bleedings directly related to the process of childbirth are diagnosed more than 2 hours after delivery, and this primarily concerns bleeding after caesarean section.

Unfortunately, the reason for the delayed diagnosis of bleeding is often inadequate follow-up in the early postpartum period. And so far, despite the development of modern technologies and the pharmaceutical industry, the famous Russian obstetrician G. G. Genter's saying is relevant: period" [9].

Thus, the classification of PKK, which is common in domestic obstetrics, as occurring within 2 hours after childbirth, is not fully consistent with the etiology. In our opinion, a nominal increase in the implementation period, or, more precisely, diagnosis, of the PKK to 24 hours will allow us to consider the domestic classification as etiological.

An equally weighty argument in favor of increasing the period for early hypotonic bleeding is the unification of obstetric management tactics. The classification of any pathology implies or should imply a clear algorithm of actions. Thus, measures for postpartum hemorrhage correspond to uniform standards both in the world and in the Russian Federation [1, 3, 6].

Regulated algorithms for managing early hypotonic bleeding are associated with the volume of blood loss, the effectiveness of successive stages of care, but not with the time of bleeding onset. In order to avoid discrepancy between the diagnosis and obstetric tactics, in our opinion, it is advisable to classify bleeding directly related to complications of the birth act and diagnosed within 24 hours of the postpartum period as PKK.

Regulated algorithms for managing early hypotonic bleeding are associated with the volume of blood loss, the effectiveness of successive stages of care, but not with the time of bleeding onset. In order to avoid discrepancy between the diagnosis and obstetric tactics, in our opinion, it is advisable to classify bleeding directly related to complications of the birth act and diagnosed within 24 hours of the postpartum period as PKK. Late (secondary) bleeding is realized in the period from 24 hours to 6-12 weeks. postpartum period [1, 5–7, 10]. The frequency of AUC is 0.01-2%. The risk of bleeding is usually associated with an inflammatory process in the uterus, a secondary decrease in contractile activity, subinvolution, and impaired rejection of the decidual tissue, usually occurring within 7–9 days. A common cause of PPP is the retention of placental fragments, which usually undergo necrosis, become covered with fibrin, and take the form of placental polyps. Rejection of a placental polyp can cause PPP throughout the postpartum period [10–12].

Extremely rare causes of PPK include congenital defects in hemostasis, choriocarcinoma, pseudoaneurysms of the uterine arteries, and arteriovenous fistulas [12]. PPP usually occurs within 1-2 weeks. after childbirth and not earlier than 2-3 days.

It should be said that many domestic obstetricians did not give a clear temporal definition of late bleeding, but pointed to the etiological factors of their occurrence [9, 11]. For example, N. S. Baksheev adhered to the etiological classification of postpartum hemorrhage. In his opinion, PKK, as a result of a violation of the motor function of the uterus (hypotension, placental remnants), injuries of the birth canal, tumors of the uterus and hemostasis defects, are realized within 24 hours after childbirth [10]. V. E. Radzinsky adheres to a similar definition of the PKK [13].

Thus, we consider it appropriate to discuss the need to increase the bleeding period of PKK to 24 hours and the period of PKK from 24 hours in the classification of bleeding

up to 6 weeks, i.

e. up to 42 days of the postpartum period included in the maternal mortality statistics. An increase in the period of implementation and diagnosis of PKK will make it possible to bring the domestic classification into line with the etiology of postpartum hemorrhage, obstetric management tactics and accepted international standards.

e. up to 42 days of the postpartum period included in the maternal mortality statistics. An increase in the period of implementation and diagnosis of PKK will make it possible to bring the domestic classification into line with the etiology of postpartum hemorrhage, obstetric management tactics and accepted international standards. Share material print Add to favorites

1. WHO recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. Geneva: WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee.

2. Kurtser M. A., Breslav I. Yu., Kutakova Yu. Yu. et al. Hypotonic postpartum hemorrhage. The use of ligation of the internal iliac arteries and embolization of the uterine arteries in the early postpartum period // Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012. No. 7. P.36–41 [Kurcer M.A., Breslav I. Yu., Kutakova Yu.Yu. i dr. Gipotonicheskie postlerodovy'e krovotecheniya. Ispol`zovanie perevyazki vnutrennix podvzdoshny`x arterij i e`mbolizacii matochny`x arterij v rannem poslerodovom periode // Akusherstvo i ginekologiya. 2012. No. 7. S.36–41 (in Russian)].

Ispol`zovanie perevyazki vnutrennix podvzdoshny`x arterij i e`mbolizacii matochny`x arterij v rannem poslerodovom periode // Akusherstvo i ginekologiya. 2012. No. 7. S.36–41 (in Russian)].

3. Prevention, treatment and management algorithm for obstetric bleeding // Clinical recommendations of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Letter of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation dated May 29, 2014 No. 15-4/10/2-3881 [Profilaktika, lechenie i algoritm vedeniya pri akusherskix krovotecheniyax // Klinicheskie rekomendacii MZ RF. Letter of the Ministerstva zdravooxraneniya RF dated May 29, 2014 No. 15–4/10/2–3881 (in Russian)].

4. Savelyeva G. M., Kurtser M. A., Breslav I. Yu. et al. Experience in using the Haemonetics Cell Saver 5+ device in obstetric practice // Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013. No. 9. P.64–71 [Savel'eva G.M., Kurcer M. A., Breslav I. Yu. i dr. Opy`t ispol`zovaniya apparata Haemonetics Cell Saver 5+ v akusherskoj praktike // Akusherstvo i ginekologiya. 2013. No. 9. S.64–71 (in Russian)].

2013. No. 9. S.64–71 (in Russian)].

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Postpartum hemorrhage // Practice Bulletin. Obstet Gynecol 2017. Vol. 130(4). P.168–186. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002351

6. FIGO guidelines. Prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage in low-resource settings FIGO Safe Motherhood and Newborn Health (SMNH) Committee // Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012. Vol. 117. P.108–111.

7. Corton M. M. Williams Obstetrics 24th ed. 2014. P.1376.

8. Sentilhes L., Vayssière C., Deneux-Tharaux C. et al. Postpartum hemorrhage: guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF): in collaboration with the French Society of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care (SFAR) // Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016. Vol. 198. P.12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.12.012

31–1933. 298+318+240 p. [Genter G. G. Akusherskij seminarij: v 3 t. L.–M.: Gosizdat, 1931–1933. 298+318+240s. (in Russian)].

10. Baksheev N. S. Uterine bleeding in obstetrics. 2nd ed. Kyiv: Health, 1970. 452 p. [Baksheev N. S. Matochny`e krovotecheniya v akusherstve. 2nd ed. Kiev: Zdorov'ya, 1970. 452 s. (in Russian)].

Baksheev N. S. Uterine bleeding in obstetrics. 2nd ed. Kyiv: Health, 1970. 452 p. [Baksheev N. S. Matochny`e krovotecheniya v akusherstve. 2nd ed. Kiev: Zdorov'ya, 1970. 452 s. (in Russian)].

11. Gruzdev V.S. Course of obstetrics and women's diseases. Berlin: State Publishing House R.S.F.S.R., 1922. 626 p. [Gruzdev V. S. Kurs akusherstva i zhenskix boleznej. Berlin: Gosizdat R.S.F.S.R.,1922.626s. (in Russian)].

12. Akladios C. Y., Sananes N., Gaudineau A. et al. Secondary postpartum hemorrhage // J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2014. Vol. 43 (10). P.1161–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.jgyn.2014.10.008

13. Radzinsky V. E. Guide to practical exercises in obstetrics: textbook / ed. V. E. Radzinsky. M.: GEOTAR-Media, 2007. 656 p. [Radzinskij V. E. Rukovodstvo k prakticheskim zanyatiyam po akusherstvu: uchebnoe posobie / rod red. V. E. Radzinsky. M.: GE'OTAR-Media, 2007. 656 s. (in Russian)].

Content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. 0 International License.

0 International License.

Get the pdf version of article

Download article All articles of the issueSimilar articles

04/25/2019

Neurasthenic syndrome in general medical practice. Therapy options

Share post

30.04.2020

Features of the updated classification of epileptic seizure and epilepsy

Share post

29.10.2019

Epidemiology of primary brain tumors in children on the example of Krasnoyarsk

Share post

28.

Practice

Practice