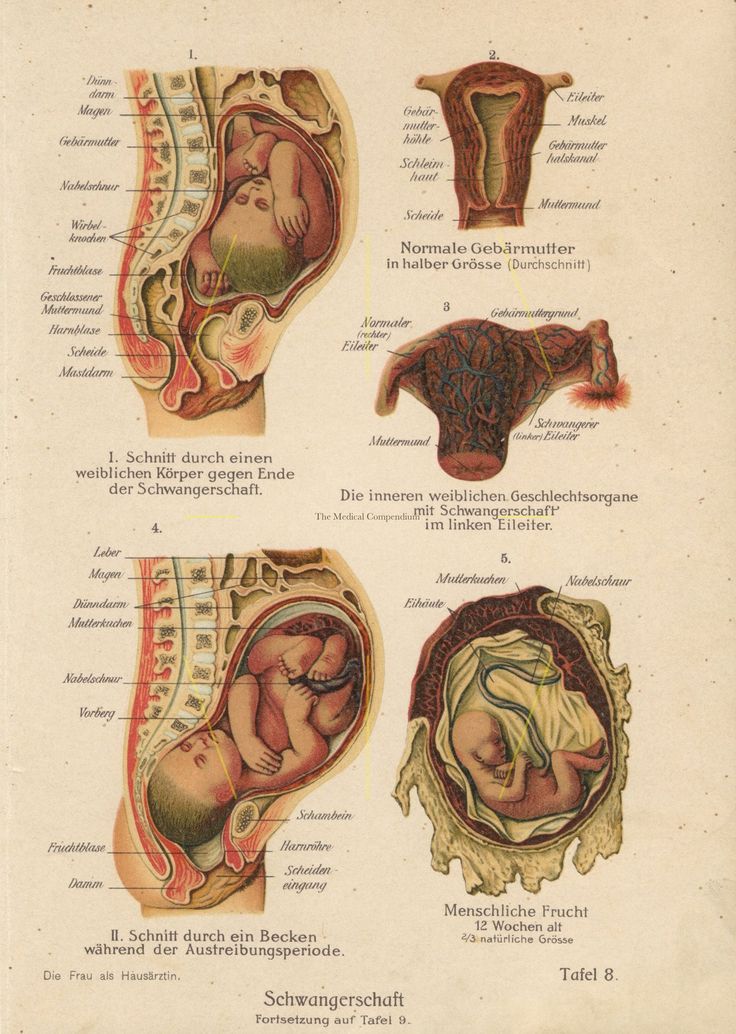

Pregnant women uterus

Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - uterus

Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - uterus | Pregnancy Birth and Baby beginning of content5-minute read

Listen

What does the uterus look like?

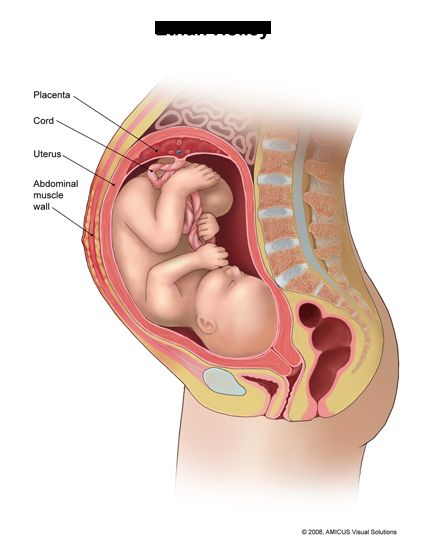

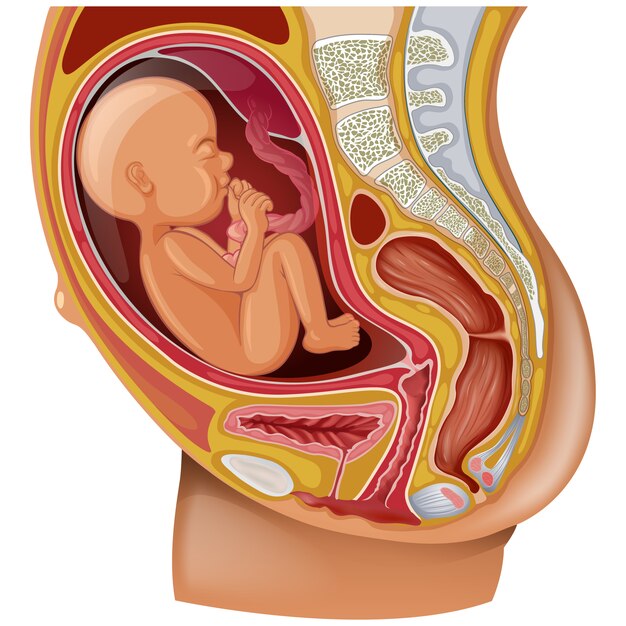

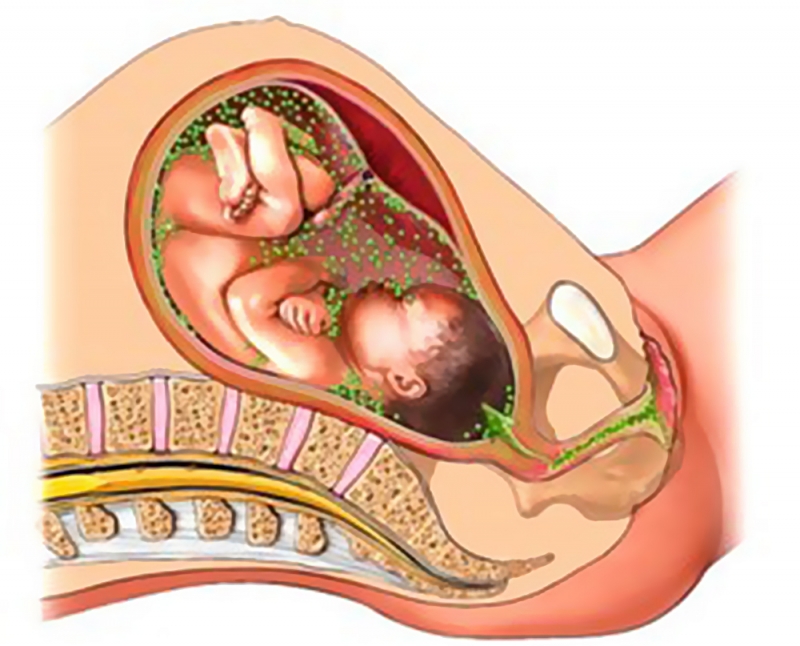

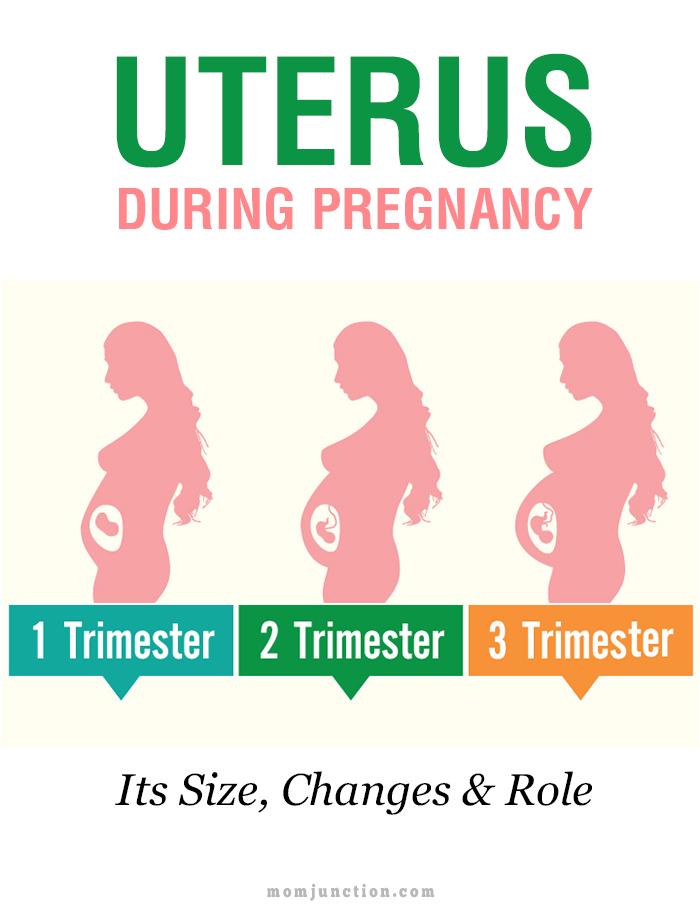

One of the most recognised changes in a pregnant woman’s body is the appearance of the ‘baby bump’, which forms to accommodate the baby growing in the uterus. The primary function of the uterus during pregnancy is to house and nurture your growing baby, so it is important to understand its structure and function, and what changes you can expect the uterus to undergo during pregnancy.

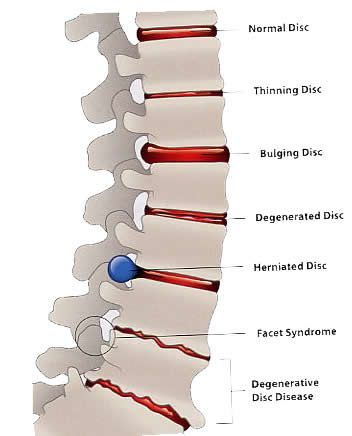

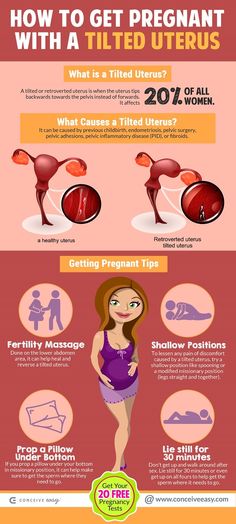

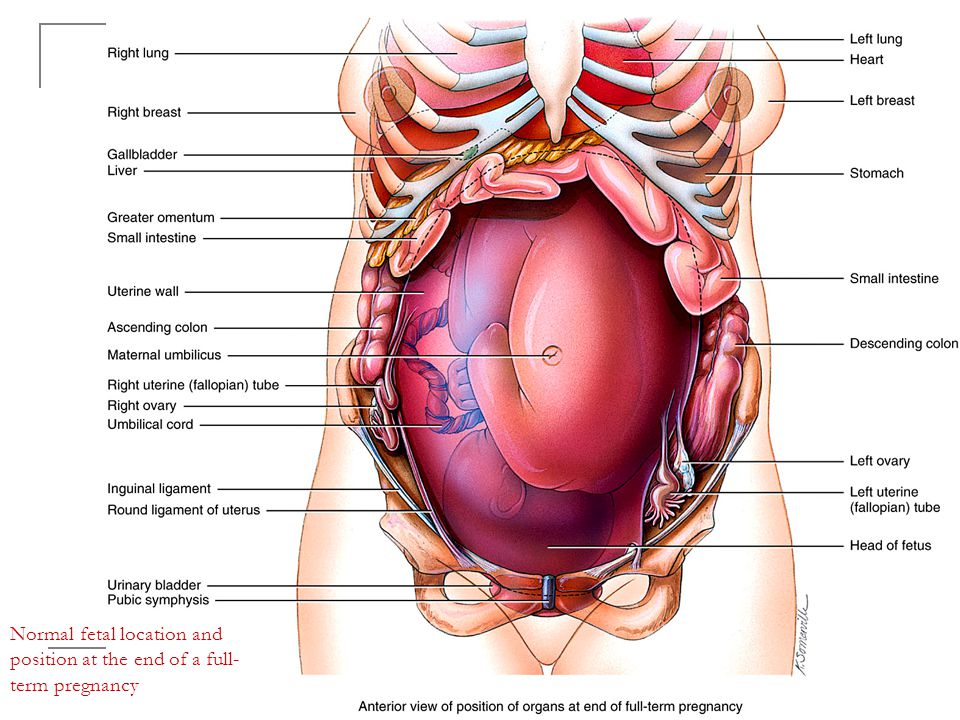

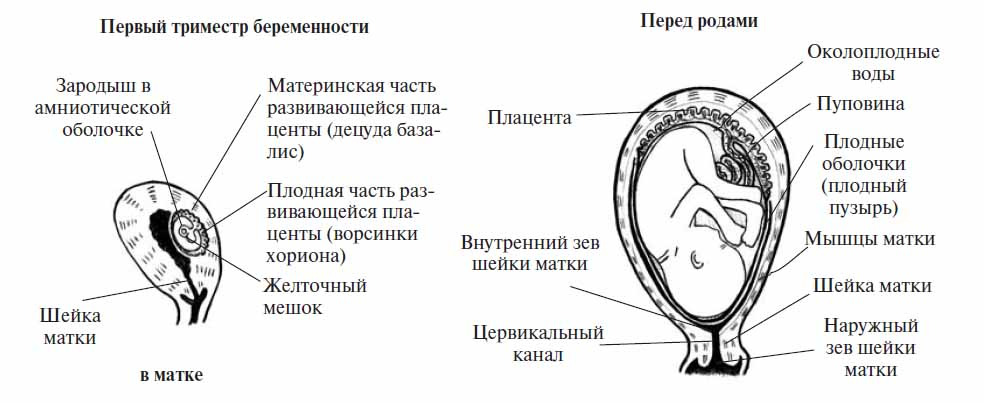

The uterus (also known as the ‘womb’) has a thick muscular wall and is pear shaped. It is made up of the fundus (at the top of the uterus), the main body (called the corpus), and the cervix (the lower part of the uterus ). Ligaments – which are tough, flexible tissue – hold it in position in the middle of the pelvis, behind the bladder, and in front of the rectum.

The uterus wall is made up of 3 layers. The inside is a thin layer called the endometrium, which responds to hormones – the shedding of this layer causes menstrual bleeding. The middle layer is a muscular wall. The outside layer of the uterus is a thin layer of cells.

Illustration showing the female reproductive system.The size of a non-pregnant woman's uterus can vary. In a woman who has never been pregnant, the average length of the uterus is about 7 centimetres. This increases in size to approximately 9 centimetres in a woman who is not pregnant but has been pregnant before. The size and shape of the uterus can change with the number of pregnancies and with age.

How does the uterus change during pregnancy?

During pregnancy, as the baby grows, the size of a woman’s uterus will dramatically increase. One measure to estimate growth is the fundal height, the distance from the pubic bone to the top of the uterus. Your doctor (GP) or obstetrician or midwife will measure your fundal height at each antenatal visit from 24 weeks onwards. If there are concerns about your baby’s growth, your doctor or midwife may recommend using regular ultrasound to monitor the baby.

Your doctor (GP) or obstetrician or midwife will measure your fundal height at each antenatal visit from 24 weeks onwards. If there are concerns about your baby’s growth, your doctor or midwife may recommend using regular ultrasound to monitor the baby.

Fundal height can vary from person to person, and many factors can affect the size of a pregnant woman’s uterus. For instance, the fundal height may be different in women who are carrying more than one baby, who are overweight or obese, or who have certain medical conditions. A full bladder will also affect fundal height measurement, so it’s important to empty your bladder before each measurement. A smaller than expected fundal height could be a sign that the baby is growing slowly or that there is too little amniotic fluid. If so, this will be monitored carefully by your doctor. In contrast, a larger than expected fundal height could mean that the baby is larger than average and this may also need monitoring.

As the uterus grows, it can put pressure on the other organs of the pregnant woman's body. For instance, the uterus can press on the nearby bladder, increasing the need to urinate.

For instance, the uterus can press on the nearby bladder, increasing the need to urinate.

How does the uterus prepare for labour and birth?

Braxton Hicks contractions, also known as 'false labour' or 'practice contractions', prepare your uterus for the birth and may start as early as mid-way through your pregnancy, and continuing right through to the birth. Braxton Hicks contractions tend to be irregular and while they are not generally painful, they can be uncomfortable and get progressively stronger through the pregnancy.

During true labour, the muscles of the uterus contract to help your baby move down into the birth canal. Labour contractions start like a wave and build in intensity, moving from the top of the uterus right down to the cervix. Your uterus will feel tight during the contraction, but between contractions, the pain will ease off and allow you to rest before the next one builds. Unlike Braxton Hicks, labour contractions become stronger, more regular and more frequent in the lead up to the birth.

How does the uterus change after birth?

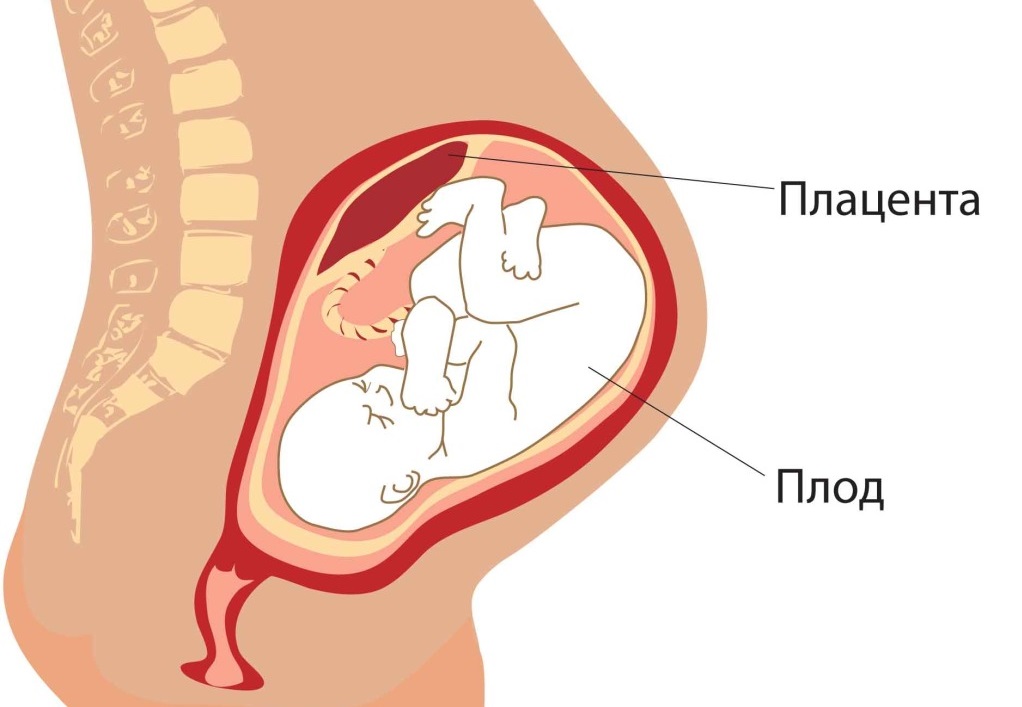

After the baby is born, the uterus will contract again to allow the placenta, which feeds the baby during pregnancy, to leave the woman’s body. This is sometimes called the ‘after birth’. These contractions are milder than the contractions felt during labour. Once the placenta is delivered, the uterus remains contracted to help prevent heavy bleeding known as ‘postpartum haemorrhage‘.

The uterus will also continue to have contractions after the birth is completed, particularly during breastfeeding. This contracting and tightening of the uterus will feel a little like period cramps and is also known as 'afterbirth pains'.

Read more here about the first few days after giving birth.

Sources:

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (Labour and birth), StatPearls Publishing (Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis), Department of Health (Clinical practice guidelines: Pregnancy care), Better Health Channel Victoria (Pregnancy stages and changes), Mater Mother's Hospital (Labour and birth information), Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (The First Few Weeks Following Birth), Queensland Health (Queensland Clinical Guidelines – maternity and neonatal), King Edward Memorial Hospital (Fundal height: Measuring with a tape measure), Royal Hospital for Women (Fetal growth assessment (clinical) in pregnancy), MSD Manual (Female internal genital organs)Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Last reviewed: October 2020

Back To Top

Related pages

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - abdominal muscles

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - cervix

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - pelvis

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - perineum and pelvic floor

Need more information?

Prolapsed uterus - Better Health Channel

The pelvic floor and associated supporting ligaments can be weakened or damaged in many ways, causing uterine prolapse.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

Uterus, cervix & ovaries - fact sheet | Jean Hailes

This fact sheet discusses some of the health conditions that may affect a woman's uterus, cervix and ovaries.

Read more on Jean Hailes for Women's Health website

Uterine differences

Some people have a uterus with a different shape. If your uterus has a different shape, you may have difficulties becoming pregnant, recurrent miscarriages or premature birth.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Dilatation and curettage (D&C)

A D&C is an operation to lightly scrape the inside of the uterus (womb).

Read more on WA Health website

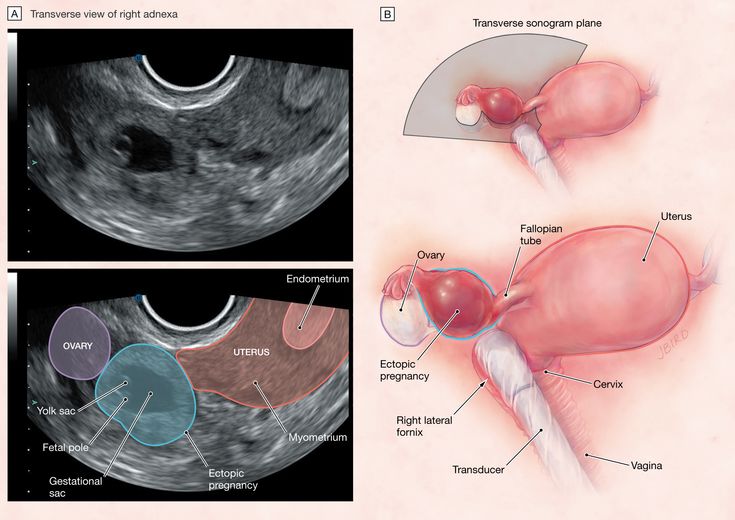

Ectopic pregnancy

An ectopic pregnancy occurs when a fertilised egg implants outside the uterus (womb)

Read more on WA Health website

Hormonal IUD (intrauterine device, Mirena®) | Body Talk

The hormonal IUD is a type of contraception and is placed inside the uterus by a specially trained doctor or nurse. Find out all the facts here.

Find out all the facts here.

Read more on Body Talk website

Placental abruption - Better Health Channel

Placental abruption means the placenta has detached from the wall of the uterus, starving the baby of oxygen and nutrients.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

Copper IUD (intrauterine device) | Body Talk

The copper IUD is a type of contraception and is placed inside the uterus by a specially trained doctor or nurse. Find out all the facts here.

Read more on Body Talk website

Placenta previa - Better Health Channel

Placenta previa means the placenta has implanted at the bottom of the uterus, over the cervix or close by.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

Mirena IUD | Hormonal IUD Mirena | IUD Mirena insertion | IUD Mirena cost | Mirena IUD Melbourne - Sexual Health Victoria

The hormonal intrauterine device (IUD) is a small contraceptive device that is put into the uterus (womb) to prevent pregnancy.

Read more on Sexual Health Victoria website

Disclaimer

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is not responsible for the content and advertising on the external website you are now entering.

OKNeed further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Video call

- Contact us

- About us

- A-Z topics

- Symptom Checker

- Service Finder

- Subscribe to newsletters

- Linking to us

- Information partners

- Terms of use

- Privacy

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is funded by the Australian Government and operated by Healthdirect Australia.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby’s information and advice are developed and managed within a rigorous clinical governance framework.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Healthdirect Australia acknowledges the Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia and their continuing connection to land, sea and community. We pay our respects to the Traditional Owners and to Elders both past and present.

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

Physiology, Pregnancy - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf

Introduction

Pregnancy is a state of having implanted products of conception located either in the uterus or elsewhere in the body. It ends through either spontaneous or elective abortion or delivery. During this time, the mother’s body goes through immense changes involving all organ systems to sustain the growing fetus. All medical providers must be aware of these alterations present in pregnancy to be able to provide the best possible care for both mother and fetus.

It ends through either spontaneous or elective abortion or delivery. During this time, the mother’s body goes through immense changes involving all organ systems to sustain the growing fetus. All medical providers must be aware of these alterations present in pregnancy to be able to provide the best possible care for both mother and fetus.

Issues of Concern

The female body goes through immense changes during a pregnancy that involve all organ systems in the body. These changes result in physiology that differs from that of a non-pregnant female. Additionally, abnormalities in the development of pregnancy can lead to further complications for both mother and fetus. With the maternal mortality rate in the United States reaching almost 18 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2009, a drastic increase from the 7.2 deaths per 100,000 in 1987, it has become more critical for all healthcare providers to understand the typical changes that accompany pregnancy, as well as recognize changes that go beyond typical pregnancy symptoms. [1]

[1]

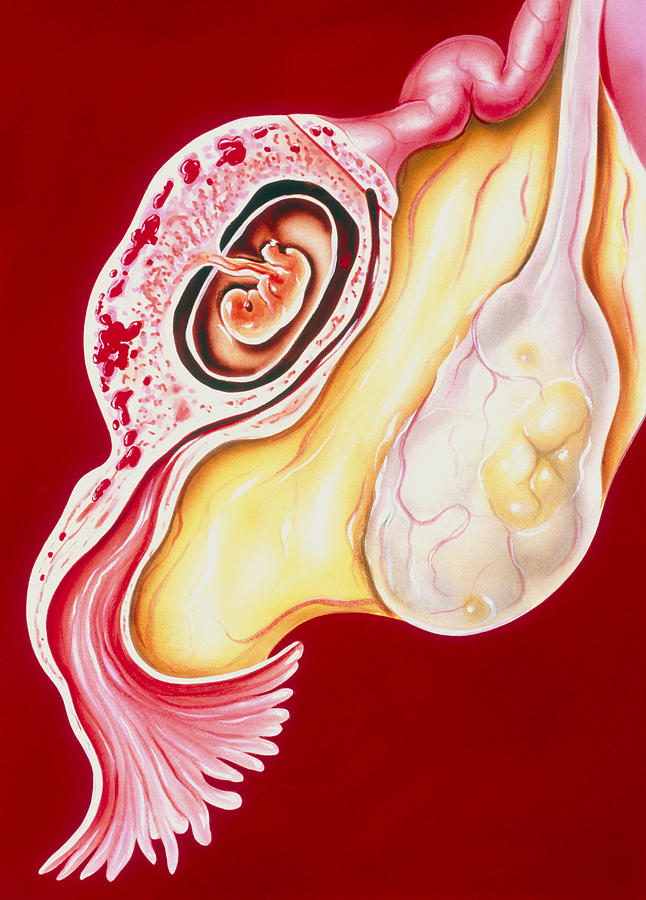

Cellular Level

The fertilization of an egg with a sperm starts the process of embryogenesis. The fertilized egg goes through several divisions to form a blastocyst. This blastocyst then initiates implantation with the maternal endometrium. Implantation triggers the uterine stroma to undergo decidualization to accommodate the embryo. This decidua supports embryo survival and appears to act as a barrier against immunologic responses. Additionally, upon implantation, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) begins to be secreted, allowing the sustenance of pregnancy. The blastocyst then begins the process of forming three distinct germ layers, including the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. At this stage, the blastocyst then becomes an embryo. The embryo goes through a process known as organogenesis, in which the majority of the major organ systems develop. After 8 weeks from implantation, or 10 weeks gestational age, the embryo is then termed a fetus until birth.[2]

Development

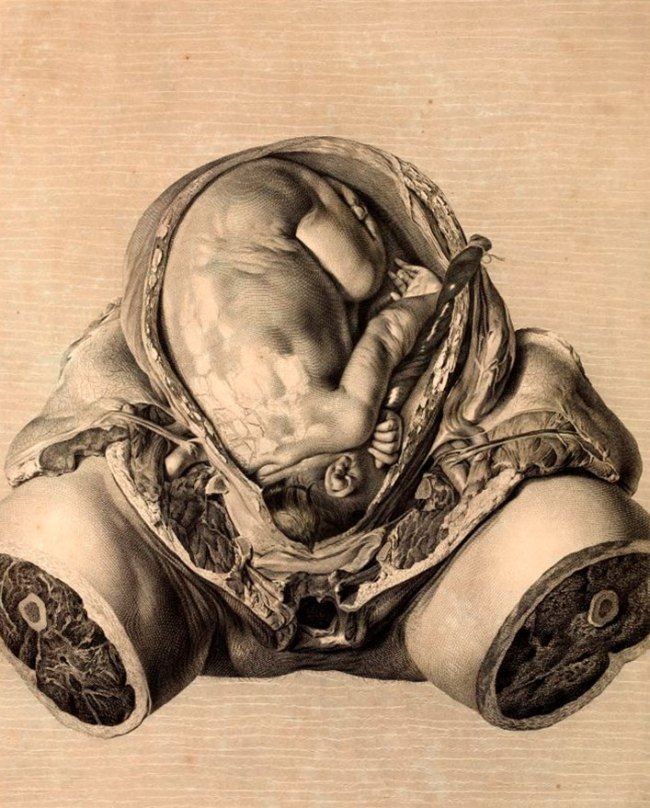

The duration of pregnancy, from implantation of a fertilized ovum to birth, is taken as 266 days. However, as pregnancy dating is typically from the first day of the last menstrual period, the duration of pregnancy is considered to be 280 days on average. This duration is the amount of time by which approximately half of all women will deliver their babies. Babies born from 37 0/7 weeks gestation to 38 6/7 weeks are considered early term. Those born between 39 0/7 weeks and 40 6/7 weeks are labeled full term. Babies born 41 0/7 weeks through 41 6/7 weeks are titled late-term. Any baby born at 42 0/7 weeks gestation and beyond is deemed post-term.[3]

However, as pregnancy dating is typically from the first day of the last menstrual period, the duration of pregnancy is considered to be 280 days on average. This duration is the amount of time by which approximately half of all women will deliver their babies. Babies born from 37 0/7 weeks gestation to 38 6/7 weeks are considered early term. Those born between 39 0/7 weeks and 40 6/7 weeks are labeled full term. Babies born 41 0/7 weeks through 41 6/7 weeks are titled late-term. Any baby born at 42 0/7 weeks gestation and beyond is deemed post-term.[3]

Organ Systems Involved

Pregnancy induces a coordinated response of multiple organ systems to support both mother and fetus.

Female Reproductive System [4]

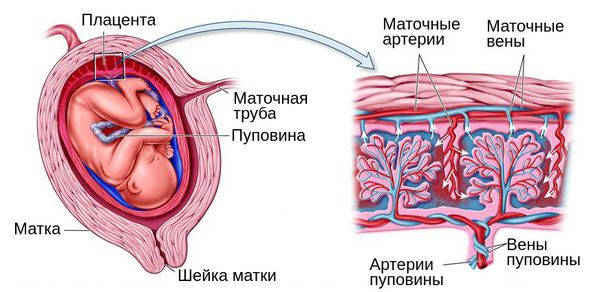

To accommodate a growing fetus, the uterus must undergo extreme structural changes and cellular hypertrophy. During this time, the uterus must maintain a passive noncontractile state; this occurs through elevated levels of progesterone, which act to relax smooth muscle—growth of the placenta results in uterine tissue and vascular remodeling. Hormonal signals, primarily estrogen, are responsible for initiating the uterine growth process during early pregnancy. The uterus increases from 70 g to 1100 g, with its volume capacity increasing from 10 mL to 5 L. Between weeks 12 and 16, the lower uterine corpus unfolds, allowing the uterus to become more spherical and giving room for amniotic sac expansion with minimal stretching of the uterus. When fetal growth rate begins to accelerate at 20 weeks, the uterus rapidly elongates, and the walls thin. The longitudinal diameter grows more rapidly than the left-right and anterior-posterior diameters, with the maximum rate of elongation happening between weeks 20 and 32. By 28 weeks, the maximum fetal growth rate has occurred, and the uterine tissue growth slows while continuing to stretch rapidly and become thin. Within several weeks of delivery, the uterus then returns to its pre-pregnancy structure.

Hormonal signals, primarily estrogen, are responsible for initiating the uterine growth process during early pregnancy. The uterus increases from 70 g to 1100 g, with its volume capacity increasing from 10 mL to 5 L. Between weeks 12 and 16, the lower uterine corpus unfolds, allowing the uterus to become more spherical and giving room for amniotic sac expansion with minimal stretching of the uterus. When fetal growth rate begins to accelerate at 20 weeks, the uterus rapidly elongates, and the walls thin. The longitudinal diameter grows more rapidly than the left-right and anterior-posterior diameters, with the maximum rate of elongation happening between weeks 20 and 32. By 28 weeks, the maximum fetal growth rate has occurred, and the uterine tissue growth slows while continuing to stretch rapidly and become thin. Within several weeks of delivery, the uterus then returns to its pre-pregnancy structure.

Cardiovascular [5]

During pregnancy, the cardiac output increases by 30 to 60%, with the majority of the increase occurring during the first trimester. The maximum output is reached between 20 and 24 weeks and is maintained until delivery. Initially, the increase in cardiac output is due to an increase in stroke volume. As the stroke volume decreases towards the end of the third trimester, an increase in heart rate acts to maintain the increased cardiac output.

The maximum output is reached between 20 and 24 weeks and is maintained until delivery. Initially, the increase in cardiac output is due to an increase in stroke volume. As the stroke volume decreases towards the end of the third trimester, an increase in heart rate acts to maintain the increased cardiac output.

Systemic vascular resistance decreases, resulting in decreased arterial blood pressure. Systolic blood pressure decreases by approximately 5 to 10 mm Hg, and diastolic blood pressure decreases by 10 to 15 mm Hg. This decrease reaches its lowest point at 24 weeks, at which point it slowly returns to pre-pregnancy levels. This decrease in arterial blood pressure is due to the elevated progesterone levels present during pregnancy. Progesterone leads to smooth muscle relaxation, thus decreasing vascular resistance.

Due to these physiological changes, bounding or collapsing pulses, as well as ejection systolic murmurs, are present in the majority of pregnant women. A third heart sound may be present, and ectopic beats and peripheral edema are also common. The changes in the position of the heart that occur as pregnancy progress lead to ECG changes that are considered normal findings in pregnancy. These include: atrial and ventricular ectopic beats, small Q waves and inverted T waves in lead III, ST-segment depression and T wave inversion in inferior and lateral leads, and left axis shift.

The changes in the position of the heart that occur as pregnancy progress lead to ECG changes that are considered normal findings in pregnancy. These include: atrial and ventricular ectopic beats, small Q waves and inverted T waves in lead III, ST-segment depression and T wave inversion in inferior and lateral leads, and left axis shift.

Pulmonary [6]

During pregnancy, the diaphragm elevates, resulting in a 5% decrease in total lung capacity (TLC). However, the tidal volume (TV) increases by 30 to 40%, thereby decreasing the expiratory reserve volume by 20%. Minute ventilation is similarly increased by 30 to 40%, owing to the fact that TV becomes increased while a constant respiratory rate is maintained.

The increase in minute ventilation that occurs during pregnancy allows for an increase in alveolar (PAO2) and arterial (PaO2) PO2 levels and a decrease in PACO2 and PaCO2. PaCO2 decreases from a pre-pregnancy level of 40 mm Hg to 30 mm Hg by 20 weeks. This decrease in PaCO2 creates an increased CO2 gradient between the fetus and mother, thus enhancing oxygen delivery and carbon dioxide removal in the fetus. This gradient is created by elevated progesterone levels, which appear to act to either increase the responsiveness of the respiratory system to CO2 or to be a primary stimulant. These changes are needed to accommodate the 15% increase in metabolic rate and the 20% increase in oxygen consumption that occurs during pregnancy.

This gradient is created by elevated progesterone levels, which appear to act to either increase the responsiveness of the respiratory system to CO2 or to be a primary stimulant. These changes are needed to accommodate the 15% increase in metabolic rate and the 20% increase in oxygen consumption that occurs during pregnancy.

Decreased PaCO2 levels, increased tidal volume, and decreased total lung capacity combine to result in dyspnea of pregnancy in approximately 60% to 70% of pregnant patients. This feeling is a subjective sensation of breathlessness with no hypoxia present. It is most common during the third trimester but can start at any time.

Gastrointestinal [6]

Elevated levels of estrogen, progesterone, and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) combine to bring about nausea and vomiting, commonly termed morning sickness. Hypoglycemia can be an additional cause of nausea. Morning sickness develops in over 70% of pregnancies and can occur at any time of day. It typically resolves by weeks 14 to 16 but persists beyond week 20 in about 10-20% of pregnant patients. If nausea and vomiting are severe enough to lead to ketosis and weight loss greater than or equal to 5% of pre-pregnancy weight, the term for this is hyperemesis gravidarum. In these patients, intravenous fluid and vitamin substitution may be necessary.

It typically resolves by weeks 14 to 16 but persists beyond week 20 in about 10-20% of pregnant patients. If nausea and vomiting are severe enough to lead to ketosis and weight loss greater than or equal to 5% of pre-pregnancy weight, the term for this is hyperemesis gravidarum. In these patients, intravenous fluid and vitamin substitution may be necessary.

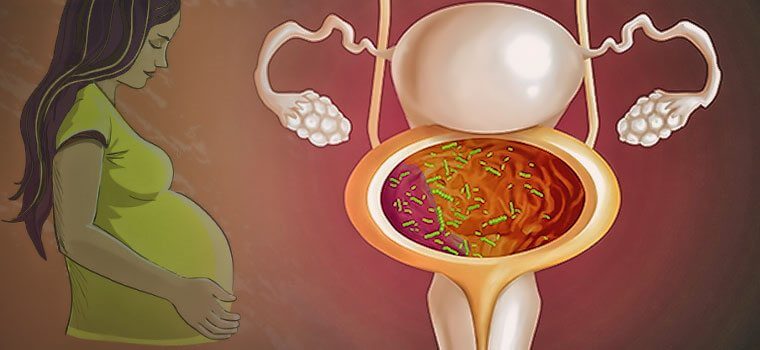

Elevated progesterone levels induce smooth muscle relaxation, leading to prolonged gastric emptying time. When combined with decreased gastroesophageal sphincter tone and upwards displacement of the stomach, reflux often occurs. Progesterone-mediated smooth muscle relaxation also leads to decreased motility in the large bowel, resulting in increased water absorption and constipation.

Renal [6]

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is activated in early pregnancy, consequently increasing sodium reabsorption. However, an increased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) acts to maintain sodium plasma levels. Additionally, elevated progesterone and prostacyclin, along with angiotensin I receptor modification in pregnancy, leads to a relative resistance to angiotensin II. This state acts to balance the vasoconstrictive effect of angiotensin and allows for vasodilation of the renal arteries mediated by relaxin stimulation of endothelium to synthesize nitric oxide.

This state acts to balance the vasoconstrictive effect of angiotensin and allows for vasodilation of the renal arteries mediated by relaxin stimulation of endothelium to synthesize nitric oxide.

Due to renal vasodilation, both the GFR and renal plasma flow increase. The GFR increases 50% starting in early pregnancy, and this increase remains until delivery. The decrease in systemic vascular resistance results in both afferent and efferent arterioles experiencing decreased vascular resistance, thus maintaining glomerular hydrostatic pressure—the resulting increased renal blood flow results in an increase in kidney size. Progesterone acts to reduce ureteral tone, peristalsis, and contraction pressure, thereby dilating the ureters.

The elevation in GFR acts to decrease blood urea nitrogen and creatinine by 25%. The elevated GFR, combined with increased glomerular capillary permeability to albumin, results in an increase of fractional excretion of protein to as much as 300 mg/day. Less effective tubular reabsorption of both glucose and urea results in increased excretion rates.

Less effective tubular reabsorption of both glucose and urea results in increased excretion rates.

Hematology [6]

In pregnancy, the RBC volume increases by 20% to 30%, while the plasma volume increases by 45 to 55%. This disproportionate volume increase leads to dilutional anemia with decreased hematocrit. WBC count increases to 6 to 16 million/mL and can be as high as 20 million/mL during and shortly after labor. Platelet concentration decreases slightly due to the increased plasma volume but typically stays within normal limits. A small proportion of women (5 to 10%) will have platelet levels between 100 and 150 billion/L without any pathology present. Fibrinogen and factors VII – X levels increase, but the clotting and bleeding times remain unchanged. However, increased venous stasis and damaged vessel endothelium result in higher rates of thromboembolic events during pregnancy. The increase in the risk of thromboembolic events starts in the first trimester and continues at least 12 weeks postpartum.

Endocrine [6]

The increased levels of estrogen in pregnancy result in a stimulation of thyroid-binding globulin, which then increases levels of thyroxine (T4) and tri-iodothyronine (T3). Free T3 and T4 levels are slightly altered, but remain relatively constant, with a slight decrease in the second and third trimesters. TSH levels decrease somewhat in the first trimester due to the weakly stimulating effect of hCG on the thyroid but increase again by the end of the first trimester. Despite the changes, pregnancy is considered to be a euthyroid state.

During pregnancy, there is an increase in hormone production by the adrenal glands. The reduced vascular resistance and blood pressure stimulate the RAA system, resulting in a three-fold increase in aldosterone by the end of the first trimester and a ten-fold increase by the end of the third trimester. There is also an increase in the production of cortisol, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), corticosteroid-binding globulin (CGB), and deoxycorticosterone, resulting in a hyper cortisol state. By the end of the third trimester, total cortisol levels are three times higher than in non-pregnant women. By the end of pregnancy, the placenta contributes to the increased cortisol state due to its production of corticotropin-releasing hormone, thus helping to trigger labor.

By the end of the third trimester, total cortisol levels are three times higher than in non-pregnant women. By the end of pregnancy, the placenta contributes to the increased cortisol state due to its production of corticotropin-releasing hormone, thus helping to trigger labor.

The increased levels of estradiol in pregnancy result in an increase in prolactin, with serum prolactin levels increasing ten-fold by the end of pregnancy. This increased production induces growth in the pituitary gland caused by the proliferation of cells in the anterior lobe. Oxytocin levels, produced by the posterior pituitary, increase throughout pregnancy and peak at term. Elevated estrogen, progesterone, and inhibin act to inhibit the production of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), making these levels undetectable.

Musculoskeletal and Dermatologic [6]

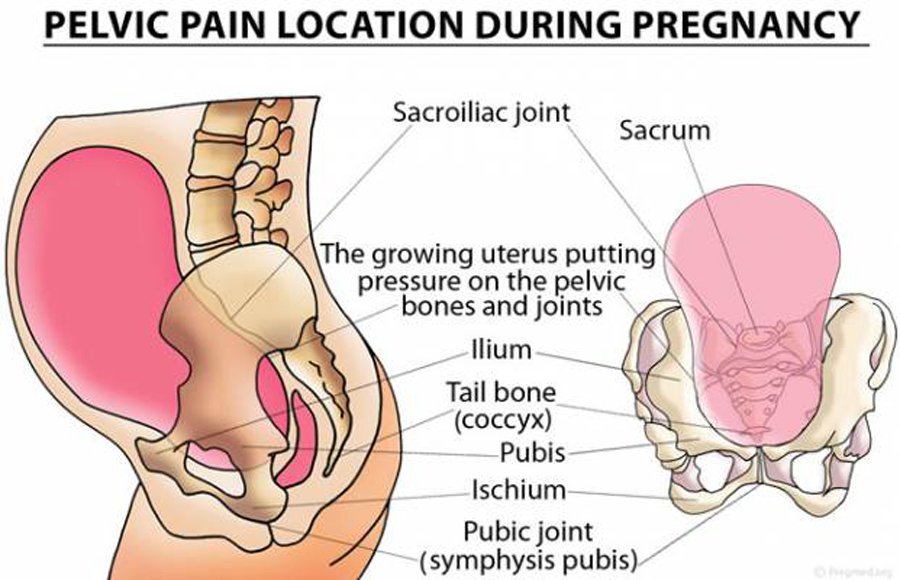

The shift in the center of gravity that occurs with pregnancy results in increased lordosis of the lower back and flexion in the neck. This shift in posture can cause lower back strain that worsens as the pregnancy progresses. Increased mobility and widening of the sacroiliac joints and pubic symphysis occur, as well as joint laxity in the lumbar spine. Carpal tunnel syndrome is a common occurrence in pregnancy due to compression of the median nerve.

This shift in posture can cause lower back strain that worsens as the pregnancy progresses. Increased mobility and widening of the sacroiliac joints and pubic symphysis occur, as well as joint laxity in the lumbar spine. Carpal tunnel syndrome is a common occurrence in pregnancy due to compression of the median nerve.

Increased estrogen levels result in spider angiomata and palmar erythema. Elevated melanocyte-stimulating hormones and steroid hormones lead to hyperpigmentation of the face, nipples, perineum, abdominal line, and umbilicus.

Metabolism [6]

The placenta produces human placental lactogen (hPL), which acts to supply nutrition to the fetus. It induces lipolysis to increase free fatty acids, which are preferentially used by the pregnant mother for fuel. It also acts as an insulin antagonist to induce a diabetogenic state. This activity prompts hyperplasia of pancreatic beta-cells to create increased insulin levels and protein synthesis. In early pregnancy, maternal insulin sensitivity increases, followed by resistance in the second and third trimesters.

Total serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels increase during pregnancy due to increased synthesis in the liver and decreased activity of lipoprotein lipase. LDL cholesterol increases throughout pregnancy, with a 50% increase by term. HDL cholesterol increases during the first half of pregnancy and then falls in the third trimester while still staying above non-pregnant levels. The increase in triglycerides is essential for supplying the mother’s energy while sparing glucose for the fetus. The increased LDL levels are crucial for placental steroidogenesis.

There are increased caloric and nutritional requirements during pregnancy, including increased requirements for protein, iron, calcium, folate, and other vitamins and minerals. The protein requirement in pregnancy increases from 60 g/day to 70 to 75 g/day, as the amino acids are transported to the developing fetus. The calcium requirement increases to 1.5 g/day, due to the fetus's requirement of 30 g of calcium. Maternal serum levels of calcium are maintained in pregnancy, with fetal needs being met by increased intestinal absorption starting at week 12.

Function

The primary function of pregnancy is to allow for the growth and development of the fetus. All changes that occur within the mother’s body are intended to allow for this growth, as well as for the development of the placenta to nourish the fetus and sustain the pregnancy.

Mechanism

The menstrual cycle ranges from 26 to 35 days, with 28 days being the average duration. Menstrual bleeding begins on the first day of the menstrual cycle, and the heaviest flow occurs, on average, on day 2. The beginning of the menstrual cycle comprises the follicular phase, during which FSH from the pituitary gland stimulates the development of a primary ovarian follicle. This follicle induces estrogen production, allowing the uterine lining to proliferate. A spike in LH, triggered by the estrogen surge, stimulates ovulation and begins the luteal phase. The greatest probability of conception occurs in the follicular phase, one day before ovulation. However, the fertile phase spans the time between 5 days before and the day of ovulation. After ovulation, the corpus luteum secretes progesterone, maintaining the endometrial lining for a fertilized ovum. If fertilization does not occur or the fertilized ovum does not implant into the endometrial lining, then the corpus luteum degenerates, progesterone levels fall, and the endometrial lining sloughs off to begin the menstrual cycle again. [7]

After ovulation, the corpus luteum secretes progesterone, maintaining the endometrial lining for a fertilized ovum. If fertilization does not occur or the fertilized ovum does not implant into the endometrial lining, then the corpus luteum degenerates, progesterone levels fall, and the endometrial lining sloughs off to begin the menstrual cycle again. [7]

If a fertilized ovum successfully implants into the endometrium, the trophoblast cells proliferate into syncytiotrophoblast cells and begin to produce hCG.[7] This sustains the corpus luteum to maintain the secretion of progesterone and estrogen, allowing the pregnancy to develop. The syncytiotrophoblast, along with the cytotrophoblast and extraembryonic mesoderm, goes on to form the placenta. The primary purpose of the placenta is to sustain the pregnancy and meet the demands of the fetus. The placental membrane allows for the exchange of nutrients and gases between the fetus and the mother’s body, acting as the fetal respiratory, gastrointestinal, endocrine, renal, hepatic, and immune systems. [8]

[8]

Pregnancy ends with the delivery of the fetus. There are several theories as to how labor initiates. Some studies show that labor becomes triggered by the withdrawal of progesterone and mechanical stretch experienced by the uterine wall.[4] Other studies suggest that inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandins, are vital in initiating uterine contractions.[9] Oxytocin then goes on to sustain contractions during labor and delivery.[10]

Related Testing

Indications for testing to confirm pregnancy, either through urine or serum sample, include a female of child-bearing age with amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain, abdominal pain, syncope, lightheadedness, dizziness, hypotension, tachycardia, nausea or vomiting, vaginal discharge, or urinary symptoms. Levels of hCG in a viable intrauterine pregnancy double approximately every 48 hours in early pregnancy. Levels peak around 10 to 12 weeks gestation, then decline to a steady state after 15 weeks.[11] Ultrasound confirmation of early pregnancy is utilized when an individual has a positive pregnancy test along with pelvic pain, abdominal pain, or vaginal bleeding. [12]

[12]

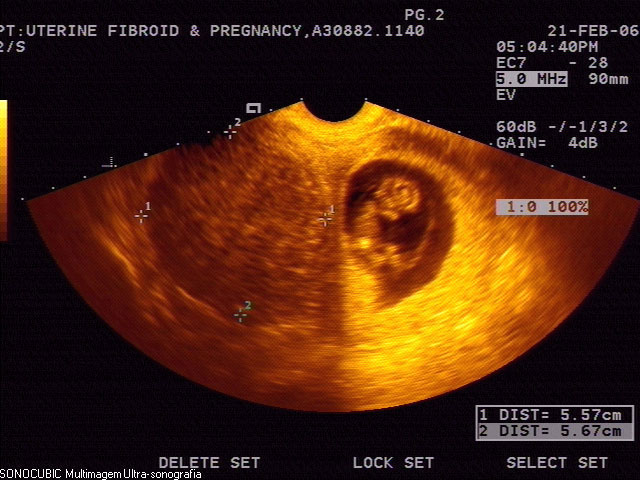

Confirmation of a viable pregnancy occurs with an ultrasound, which shows a gestational sac on transvaginal ultrasound at five weeks or with an hCG level of 1,500 to 2,000 mIU/mL. Fetal heart motion is visible on transvaginal ultrasound at six weeks or with hCG levels starting at 5,000 to 6,000 mIU/mL.[12]

Pathophysiology

As the purpose of the placenta is to support and maintain the pregnancy, any abnormality in placenta formation can result in adverse outcomes for both mother and fetus. Abnormalities can be in the form of the structure of the placenta, the location of the placenta, and the implantation of the placenta.

Preeclampsia appears to involve both maternal and fetal factors, leading to abnormal development of the vasculature in the placenta; this ultimately leads to under-perfusion, resulting in hypoxia and growth restriction. Maternal endothelial dysfunction, believed to be due to antiangiogenic factors, leads to increased vascular permeability, with activation of the coagulation cascade, vasoconstriction, and microangiopathic hemolysis. These factors lead to the clinical manifestations of preeclampsia, including hypertension, proteinuria, seizure, cerebral hemorrhage, DIC, renal failure, pulmonary edema, uteroplacental insufficiency, placental abruption, premature delivery, and increased rate of cesarean section deliveries. Preeclampsia falls into two categories, preeclampsia without severe features and preeclampsia with severe features. To be diagnosed without severe features, third-trimester blood pressure greater than 140/90 mm Hg on two occasions at least 6 hours apart is needed, as well as proteinuria over 300 mg/24 hours or protein to creatinine ratio greater than 0.3. Women with preeclampsia without severe features are managed with delivery at 37 weeks. If diagnosed before 37 weeks, they are closely monitored as inpatients, although outpatient monitoring can be utilized if there are no other comorbidities. To be diagnosed as preeclampsia with severe features, blood pressure must be greater than 160/110 mm Hg in addition to proteinuria.

These factors lead to the clinical manifestations of preeclampsia, including hypertension, proteinuria, seizure, cerebral hemorrhage, DIC, renal failure, pulmonary edema, uteroplacental insufficiency, placental abruption, premature delivery, and increased rate of cesarean section deliveries. Preeclampsia falls into two categories, preeclampsia without severe features and preeclampsia with severe features. To be diagnosed without severe features, third-trimester blood pressure greater than 140/90 mm Hg on two occasions at least 6 hours apart is needed, as well as proteinuria over 300 mg/24 hours or protein to creatinine ratio greater than 0.3. Women with preeclampsia without severe features are managed with delivery at 37 weeks. If diagnosed before 37 weeks, they are closely monitored as inpatients, although outpatient monitoring can be utilized if there are no other comorbidities. To be diagnosed as preeclampsia with severe features, blood pressure must be greater than 160/110 mm Hg in addition to proteinuria. Alternatively, blood pressure can be greater than 140/90 mm Hg on two occasions with at least one other feature, including renal insufficiency, thrombocytopenia, pulmonary edema, impaired liver function, or cerebral or visual disturbances. These patients should be delivered at 34 weeks and should receive treatment with magnesium sulfate for seizure prophylaxis. If blood pressure is greater than 160/110 mm Hg, antihypertensives should be used to decrease the risk of stroke.[13][14]

Alternatively, blood pressure can be greater than 140/90 mm Hg on two occasions with at least one other feature, including renal insufficiency, thrombocytopenia, pulmonary edema, impaired liver function, or cerebral or visual disturbances. These patients should be delivered at 34 weeks and should receive treatment with magnesium sulfate for seizure prophylaxis. If blood pressure is greater than 160/110 mm Hg, antihypertensives should be used to decrease the risk of stroke.[13][14]

Approximately 10% of patients with preeclampsia with severe features will go on to develop HELLP syndrome—these patients present with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets. Hypertension and proteinuria do not need to be present in these patients. These patients diagnosed after 34 0/7 weeks should be delivered once stabilized. If diagnosed before 34 weeks, these women should be delivered 24 to 48 hours after betamethasone administration. They should also be administered magnesium sulfate until 24 hours postpartum. [15][14]

[15][14]

Eclampsia is diagnosed when grand mal seizures occur in a preeclamptic patient. It can occur in women both with and without severe features. Eclampsia appears to occur when there is a breakdown in autoregulation of cerebral circulation due to endothelial dysfunction, hyperperfusion, and brain edema. Treatment includes seizure management and prophylaxis, blood pressure control, and delivery once the patient has been stabilized and convulsions controlled.[14]

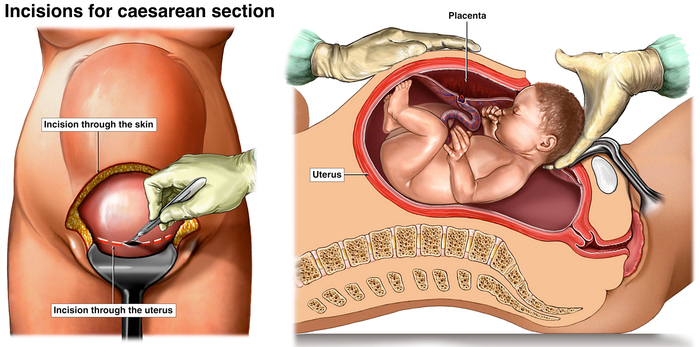

Placenta previa occurs with abnormal implantation of the placenta covering the internal cervical os. It can be considered complete, in which the internal os is completely covered by the placenta, partial previa, with the placenta covering a portion of the internal os, or marginal previa, where the edge of the placenta approaches the margin of the os. The placenta is considered low-lying when it is in the lower uterine segment but does not extend to the internal os. During the third trimester, the lower uterine segment begins thinning, leading to disruption in the placental attachment and painless bleeding. This bleeding irritates the uterus, stimulating uterine contractions that cause further separation and bleeding. As the cervix dilates and effaces during labor, placental separation and unavoidable bleeding occur, which may result in hemorrhage and shock. These patients are managed with pelvic rest after 20 weeks, decreased physical activity, and cesarean delivery between 36 and 37 weeks.[16]

This bleeding irritates the uterus, stimulating uterine contractions that cause further separation and bleeding. As the cervix dilates and effaces during labor, placental separation and unavoidable bleeding occur, which may result in hemorrhage and shock. These patients are managed with pelvic rest after 20 weeks, decreased physical activity, and cesarean delivery between 36 and 37 weeks.[16]

Placenta accreta occurs when the placenta invades into the uterine wall during implantation. If the invasion extends to the myometrium, the term for the condition is placenta increta. If the invasion extends further through the myometrium and into the serosa, this is considered placenta percreta. Placenta percreta may also invade into surrounding organs, such as the bladder or rectum. In these conditions, the placenta is unable to separate from the uterine wall properly, which can lead to hemorrhage and shock. As such, this condition can lead to the need for a hysterectomy at the time of delivery. [17]

[17]

Clinical Significance

Understanding changes that occur during pregnancy is critical for the proper management of pregnant patients. They encounter many physical changes that can create physical, mental, and emotional strain for the patient. It is essential to remain sensitive to these changes when providing care.

In addition to remaining sensitive to providing compassionate care, knowing the physiologic changes of pregnancy are essential when determining whether an apparent pathology is indeed pathological versus a normal finding in a pregnant patient. Many lab value limits are adjusted in pregnancy due to the changes in hormones and organ functioning. Hypotension and tachycardia become more prevalent throughout pregnancy, requiring careful considerations in the treatment of a pregnant trauma patient.

Overall, understanding the physiology of pregnancy allows all providers, not only OB/GYNs, to provide the best possible care.

Review Questions

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Comment on this article.

References

- 1.

Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Ko JY, Farr SL, Tong VT, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. Maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States: where are we now? J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014 Jan;23(1):3-9. [PMC free article: PMC3880915] [PubMed: 24383493]

- 2.

Zhang S, Lin H, Kong S, Wang S, Wang H, Wang H, Armant DR. Physiological and molecular determinants of embryo implantation. Mol Aspects Med. 2013 Oct;34(5):939-80. [PMC free article: PMC4278353] [PubMed: 23290997]

- 3.

Bhat RA, Kushtagi P. A re-look at the duration of human pregnancy. Singapore Med J. 2006 Dec;47(12):1044-8. [PubMed: 17139400]

- 4.

Myers KM, Elad D. Biomechanics of the human uterus. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2017 Sep;9(5) [PubMed: 28498625]

- 5.

Hu H, Pasca I. Management of Complex Cardiac Issues in the Pregnant Patient. Crit Care Clin. 2016 Jan;32(1):97-107.

[PubMed: 26600447]

[PubMed: 26600447]- 6.

Soma-Pillay P, Nelson-Piercy C, Tolppanen H, Mebazaa A. Physiological changes in pregnancy. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2016 Mar-Apr;27(2):89-94. [PMC free article: PMC4928162] [PubMed: 27213856]

- 7.

Mihm M, Gangooly S, Muttukrishna S. The normal menstrual cycle in women. Anim Reprod Sci. 2011 Apr;124(3-4):229-36. [PubMed: 20869180]

- 8.

Guttmacher AE, Maddox YT, Spong CY. The Human Placenta Project: placental structure, development, and function in real time. Placenta. 2014 May;35(5):303-4. [PMC free article: PMC3999347] [PubMed: 24661567]

- 9.

Ravanos K, Dagklis T, Petousis S, Margioula-Siarkou C, Prapas Y, Prapas N. Factors implicated in the initiation of human parturition in term and preterm labor: a review. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2015;31(9):679-83. [PubMed: 26303116]

- 10.

Arrowsmith S, Wray S. Oxytocin: its mechanism of action and receptor signalling in the myometrium.

J Neuroendocrinol. 2014 Jun;26(6):356-69. [PubMed: 24888645]

J Neuroendocrinol. 2014 Jun;26(6):356-69. [PubMed: 24888645]- 11.

Montagnana M, Trenti T, Aloe R, Cervellin G, Lippi G. Human chorionic gonadotropin in pregnancy diagnostics. Clin Chim Acta. 2011 Aug 17;412(17-18):1515-20. [PubMed: 21635878]

- 12.

Knez J, Day A, Jurkovic D. Ultrasound imaging in the management of bleeding and pain in early pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014 Jul;28(5):621-36. [PubMed: 24841987]

- 13.

El-Sayed AAF. Preeclampsia: A review of the pathogenesis and possible management strategies based on its pathophysiological derangements. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;56(5):593-598. [PubMed: 29037542]

- 14.

Kattah AG, Garovic VD. The management of hypertension in pregnancy. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013 May;20(3):229-39. [PMC free article: PMC3925675] [PubMed: 23928387]

- 15.

Haram K, Svendsen E, Abildgaard U. The HELLP syndrome: clinical issues and management.

A Review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009 Feb 26;9:8. [PMC free article: PMC2654858] [PubMed: 19245695]

A Review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009 Feb 26;9:8. [PMC free article: PMC2654858] [PubMed: 19245695]- 16.

Martinelli KG, Garcia ÉM, Santos Neto ETD, Gama SGND. Advanced maternal age and its association with placenta praevia and placental abruption: a meta-analysis. Cad Saude Publica. 2018 Feb 19;34(2):e00206116. [PubMed: 29489954]

- 17.

Bartels HC, Postle JD, Downey P, Brennan DJ. Placenta Accreta Spectrum: A Review of Pathology, Molecular Biology, and Biomarkers. Dis Markers. 2018;2018:1507674. [PMC free article: PMC6051104] [PubMed: 30057649]

Changes in the cervix during pregnancy

Pregnancy is always pleasant, but sometimes not planned. And not all women have time to prepare for it, to be fully examined before its onset. And the detection of diseases of the cervix already during pregnancy can be an unpleasant discovery.

The cervix is the lower segment of the uterus in the form of a cylinder or cone. In the center is the cervical canal, one end of which opens into the uterine cavity, and the other into the vagina. On average, the length of the cervix is 3–4 cm, the diameter is about 2.5 cm, and the cervical canal is closed. The cervix has two parts: lower and upper. The lower part is called the vaginal, because it protrudes into the vaginal cavity, and the upper part is supravaginal, because it is located above the vagina. The cervix is connected to the vagina through the vaginal fornices. There is an anterior arch - short, posterior - deeper and two lateral ones. Inside the cervix passes the cervical canal, which opens into the uterine cavity with an internal pharynx, and is clogged with mucus from the side of the vagina. Mucus is normally impervious to infections and microbes, or to spermatozoa. But in the middle of the menstrual cycle, the mucus thins and becomes permeable to sperm.

In the center is the cervical canal, one end of which opens into the uterine cavity, and the other into the vagina. On average, the length of the cervix is 3–4 cm, the diameter is about 2.5 cm, and the cervical canal is closed. The cervix has two parts: lower and upper. The lower part is called the vaginal, because it protrudes into the vaginal cavity, and the upper part is supravaginal, because it is located above the vagina. The cervix is connected to the vagina through the vaginal fornices. There is an anterior arch - short, posterior - deeper and two lateral ones. Inside the cervix passes the cervical canal, which opens into the uterine cavity with an internal pharynx, and is clogged with mucus from the side of the vagina. Mucus is normally impervious to infections and microbes, or to spermatozoa. But in the middle of the menstrual cycle, the mucus thins and becomes permeable to sperm.

Outside, the surface of the cervix has a pinkish tint, it is smooth and shiny, durable, and from the inside it is bright pink, velvety and loose.

The cervix during pregnancy is an important organ, both in anatomical and functional terms. It must be remembered that it promotes the process of fertilization, prevents infection from entering the uterine cavity and appendages, helps to "endure" the baby and participates in childbirth. That is why regular monitoring of the condition of the cervix during pregnancy is simply necessary.

During pregnancy, a number of physiological changes occur in this organ. For example, a short time after fertilization, its color changes: it becomes cyanotic. The reason for this is the extensive vascular network and its blood supply. Due to the action of estriol and progesterone, the tissue of the cervix becomes soft. During pregnancy, the cervical glands expand and become more branched.

Screening examination of the cervix during pregnancy includes: cytological examination, smears for flora and detection of infections. Cytological examination is often the first key step in the examination of the cervix, since it allows to detect very early pathological changes that occur at the cellular level, including in the absence of visible changes in the cervical epithelium. The examination is carried out to identify the pathology of the cervix and the selection of pregnant women who need a more in-depth examination and appropriate treatment in the postpartum period. When conducting a screening examination, in addition to a doctor's examination, a colposcopy may be recommended. As you know, the cervix is covered with two types of epithelium: squamous stratified from the side of the vagina and single-layer cylindrical from the side of the cervical canal. Epithelial cells are constantly desquamated and end up in the lumen of the cervical canal and in the vagina. Their structural characteristics make it possible, when examined under a microscope, to distinguish healthy cells from atypical ones, including cancerous ones.

The examination is carried out to identify the pathology of the cervix and the selection of pregnant women who need a more in-depth examination and appropriate treatment in the postpartum period. When conducting a screening examination, in addition to a doctor's examination, a colposcopy may be recommended. As you know, the cervix is covered with two types of epithelium: squamous stratified from the side of the vagina and single-layer cylindrical from the side of the cervical canal. Epithelial cells are constantly desquamated and end up in the lumen of the cervical canal and in the vagina. Their structural characteristics make it possible, when examined under a microscope, to distinguish healthy cells from atypical ones, including cancerous ones.

During pregnancy, in addition to physiological changes in the cervix, some borderline and pathological processes may occur.

Under the influence of hormonal changes that occur in a woman's body during the menstrual cycle, cyclic changes also occur in the cells of the epithelium of the cervical canal. During the period of ovulation, the secretion of mucus by the glands of the cervical canal increases, and its qualitative characteristics change. With injuries or inflammatory lesions, sometimes the glands of the cervix can become clogged, a secret accumulates in them and cysts form - Naboth follicles or Naboth gland cysts that have been asymptomatic for many years. Small cysts do not require any treatment. And pregnancy, as a rule, is not affected. Only large cysts that strongly deform the cervix and continue to grow may require opening and evacuation of the contents. However, this is very rare and usually requires monitoring during pregnancy.

During the period of ovulation, the secretion of mucus by the glands of the cervical canal increases, and its qualitative characteristics change. With injuries or inflammatory lesions, sometimes the glands of the cervix can become clogged, a secret accumulates in them and cysts form - Naboth follicles or Naboth gland cysts that have been asymptomatic for many years. Small cysts do not require any treatment. And pregnancy, as a rule, is not affected. Only large cysts that strongly deform the cervix and continue to grow may require opening and evacuation of the contents. However, this is very rare and usually requires monitoring during pregnancy.

Quite often, in pregnant women, during a mirror examination of the vaginal part, polyps cervix. The occurrence of polyps is most often associated with a chronic inflammatory process. As a result, a focal proliferation of the mucosa is formed, sometimes with the involvement of muscle tissue and the formation of a pedicle. They are mostly asymptomatic. Sometimes they are a source of blood discharge from the genital tract, more often of contact origin (after sexual intercourse or defecation). The size of the polyp is different - from millet grain rarely to the size of a walnut, their shape also varies. Polyps are single and multiple, their stalk is located either at the edge of the external pharynx, or goes deep into the cervical canal. Sometimes during pregnancy there is an increase in the size of the polyp, in some cases quite fast. Rarely, polyps first appear during pregnancy. The presence of a polyp is always a potential threat of miscarriage, primarily because it creates favorable conditions for ascending infection. Therefore, as a rule, more frequent monitoring of the cervix follows. The tendency to trauma, bleeding, the presence of signs of tissue necrosis and decay, as well as questionable secretions require special attention and control. Treatment of cervical polyps is only surgical and during pregnancy, in most cases, treatment is postponed until the postpartum period, since even large polyps do not interfere with childbirth.

They are mostly asymptomatic. Sometimes they are a source of blood discharge from the genital tract, more often of contact origin (after sexual intercourse or defecation). The size of the polyp is different - from millet grain rarely to the size of a walnut, their shape also varies. Polyps are single and multiple, their stalk is located either at the edge of the external pharynx, or goes deep into the cervical canal. Sometimes during pregnancy there is an increase in the size of the polyp, in some cases quite fast. Rarely, polyps first appear during pregnancy. The presence of a polyp is always a potential threat of miscarriage, primarily because it creates favorable conditions for ascending infection. Therefore, as a rule, more frequent monitoring of the cervix follows. The tendency to trauma, bleeding, the presence of signs of tissue necrosis and decay, as well as questionable secretions require special attention and control. Treatment of cervical polyps is only surgical and during pregnancy, in most cases, treatment is postponed until the postpartum period, since even large polyps do not interfere with childbirth.

The most common pathology of the cervix in women is erosion . Erosion is a defect in the mucous membrane. True erosion is not very common. The most common pseudo-erosion (ectopia) is a pathological lesion of the cervical mucosa, in which the usual flat stratified epithelium of the outer part of the cervix is replaced by cylindrical cells from the cervical canal. Often this happens as a result of mechanical action: with frequent and rough sexual intercourse, desquamation of the stratified squamous epithelium occurs. Erosion is a multifactorial disease. The reasons may be:

- genital infections, vaginal dysbacteriosis and inflammatory diseases of the female genital area;

- is an early onset of sexual activity and a frequent change of sexual partners. The mucous membrane of the female genital organs finally matures by the age of 20-23. If an infection interferes with this delicate process, erosion is practically unavoidable;

- is an injury to the cervix.

The main cause of such injuries is, of course, childbirth and abortion;

The main cause of such injuries is, of course, childbirth and abortion; - hormonal disorders;

- , cervical pathology may also occur with a decrease in the protective functions of immunity.

The presence of erosion does not affect pregnancy in any way, as well as pregnancy on erosion. Treatment during pregnancy consists in the use of general and local anti-inflammatory drugs for inflammatory diseases of the vagina and cervix. And in most cases, just dynamic observation is enough. Surgical treatment is not carried out throughout the entire pregnancy, since the excess of risks and benefits is significant, and after treatment during childbirth, there may be problems with opening the cervix.

Almost all women with various diseases of the cervix safely bear and happily give birth to beautiful babies!

Attention! Prices for services in different clinics may vary. To clarify the current cost, select the clinic

The administration of the clinic takes all measures to update the prices for programs in a timely manner, however, in order to avoid possible misunderstandings, we recommend that you check the cost of services by phone / with the managers of the clinic

Clinical Hospital IDKMother and Child Clinic Enthusiastov Samara

All directionsSpecialist consultations (adults)Specialist consultations (children)Molecular genetics laboratoryGeneral clinical examinationsProcedural roomOther gynecological operationsTelemedicine for adultsTherapeutic examinationsAdult ultrasound examinations

01.

Specialist consultations (adults)

02.

Specialist consultations (children)

03.

Molecular genetics laboratory

04.

06.

Other gynecological operations

07.

Adult Telemedicine

08.

Therapeutic Research

09.

Adult Ultrasound

Nothing found

The administration of the clinic takes all measures to timely update the price list posted on the website, however, in order to avoid possible misunderstandings, we advise you to clarify the cost of services and the timing of the tests by calling

Increased uterine tone during pregnancy

placenta and umbilical cord, through which the fetus is nourished. Of course, smoking by itself is unlikely to lead to hypertonicity, but in combination with other factors, it may well

If the job is constantly stressful, hazardous, or physically demanding, quit as soon as possible. If this is not possible, use your rights, which are enshrined in the labor legislation of the Russian Federation

Hypertonicity must be distinguished from Braxton-Hicks contractions: it lasts much longer than these training contractions and usually does not go away on its own (or goes away only after some long time)

what is hypertonicity

The main tissue that makes up the uterus is muscle, and according to the laws of physiology, muscle tissue contracts under the influence of any factor. Slightly the uterus contracts in women every month during menstruation, much stronger during labor pains. The uterus can also contract during pregnancy, doctors call this condition hypertonicity. What it looks like: suddenly, at some point, a woman feels that her stomach is tense, becomes hard, as if “hardening”. This state lasts for a long time - half an hour, an hour, half a day or even all day. Additionally, discomfort (or pain) in the lower back or sacrum may also appear. It is clear that such tension in the abdomen worries the mother, because since the uterus is contracting, then perhaps there is a threat of termination of pregnancy. But here it all depends on how much and how often the stomach tenses.

Braxton-Hicks contractions

It turns out that the stomach can tense up not only when there is a threat of miscarriage. Starting from the end of the second trimester, the expectant mother can feel the so-called training contractions (Brexton-Hicks contractions) - the stomach also tenses with them for a while, as if “hardening”, - in general, the sensations are the same as with hypertonicity. But the main difference between such contractions and hypertonicity is that they last for a very short time (a few seconds - a couple of minutes) and pass by themselves, as well as if you change the position of the body or take a shower. Braxton-Hicks contractions occur up to about ten times a day, and by the end of pregnancy they appear even more often. These contractions are completely normal during pregnancy, and they do not indicate any threat of interruption. It’s just that with their help, the uterus, as it were, prepares (trains) for childbirth.

where does hypertonicity come from

Hypertonicity can appear in any trimester of pregnancy. In the early stages, it occurs more often due to the fact that there is not enough progesterone, a hormone that is needed for the normal course of pregnancy. Another cause of hypertonicity is some changes in the uterine wall, for example, fibroids (a knot of uterine muscle tissue), endometriosis (growth of the uterine mucosa into the thickness of the wall), and inflammatory diseases. In these situations, the wall of the uterus is not able to stretch as it should. At later dates, hypertonicity can develop, on the contrary, with overstretching of the uterus (with polyhydramnios, large fetuses, multiple pregnancies). Very often, hypertonicity is provoked by some kind of physical activity too strong for a woman, for example, if, in a fit of “nesting”, the mother suddenly began to move and rearrange something in the apartment herself, or she simply moved for a very long time without resting. Someone hypertonicity occurs after psychological overstrain.

how to recognize hypertonicity

Hypertonicity must be distinguished from Braxton-Hicks contractions - as mentioned earlier, it lasts much longer than these training contractions and usually does not go away by itself (or goes away only after some long time). But if the mother cannot understand whether she has hypertension or not, you should consult a doctor. If there is still an increased tone of the uterus, the doctor, simply by placing his hand on his stomach, will feel a seal, tension, up to the feeling of a stone at hand. In addition, you can always do an ultrasound, on which, with hypertonicity, areas of local thickening of the muscular layer of the uterus are visible, and also look at the cervix, by the state of which you can also judge whether there is a threat of abortion or not.

what to do in case of hypertonicity

If it appears, first of all you need to:

1. Calm down and lie down if possible. Do not panic, extra stress will not bring any benefits, especially since without consulting a doctor it is still not clear whether there is hypertonicity and how pronounced it is. Or maybe it's a false alarm? In addition, you can use relaxation techniques (breathing, auto-training, etc.).

2. Call your doctor. Of course, the doctor will not make a diagnosis in absentia, but since he knows the history of the expectant mother, her real or possible problems, he will be able to give the right direction for further action.

3. If it is not possible to contact your doctor, you can contact any clinic or antenatal clinic where pregnant women are treated. If medical institutions are already closed (late evening, at night), you can call an ambulance - she will take you to the nearest hospital or maternity hospital (you can also get there by taxi).

4. Hypertonicity is well eliminated by special medicines that relax the uterus (tocolytics), and if the doctor has prescribed them, then you should not be afraid to take them: they help quickly enough and do not harm the child.