Pregnant teenagers giving birth

Teenage Pregnancy: Labor and Delivery

Labor is the process of giving birth. Delivery is the birth itself.

There are 3 Stages of Labor

Stage One

Stage Two

-

Starts when your cervix is 10 cm dilated.

-

Pushing the baby through the birth canal can take anywhere from 15 minutes to 2 hours.

-

This stage ends when the baby is delivered.

Stage Three

Things to Remember About Labor

-

Remember that no two labors are alike. Most women having their first baby are in labor anywhere from 14 to 19 hours.

-

If you think you are in labor, get in a comfortable position, drink a big glass of water and empty your bladder.

-

Keep track of how far apart your contractions are (from the start of one to the start of the next). You can use the last sheet of this Helping Hand.

-

If contractions do not get better within 30 minutes: call the Teen and Pregnant Clinic at 614-722-2450 and select option 2, OR CALL YOUR DELIVERY HOSPITAL.

True Labor

Contractions happen when the muscles of your uterus tighten. That causes pain. In true labor, contractions will help your baby through the birth canal.

True labor means your water has broken or your cervix is at least 4 cm dilated and changing with regular contractions.

When you are in true labor your contractions:

-

Get longer, stronger and closer together.

-

Are 60 to 120 seconds long (1 to 2 minutes). Contractions continue or increase with walking.

-

Can be felt in your back or entire abdomen.

-

Cause your cervix to soften, open and change.

You may have a “bloody show” (a pink tinged discharge from your vagina).

False Labor

When you are in false labor your contractions:

-

Are irregular.

They do not get longer, stronger, or closer together.

They do not get longer, stronger, or closer together. -

Are 30 to 60 seconds long.

-

Decrease with walking or taking a bath.

-

Sometimes feel like menstrual cramps.

-

Do not cause your cervix to change.

Braxton Hicks contractions are a mild tightening of your abdomen that comes and goes.

You should go to the Labor and Delivery area of your planned delivery hospital if you think you are in labor and you feel or see one or more of the following:

-

Contractions every 5 minutes, lasting at least a minute, and you have to stop to breathe to get through it.

-

Continuous leaking fluid or you think your water has broken.

-

More than a teaspoon of bright red blood.

-

Severe, constant pain or pressure in your abdomen or pelvic area.

-

Fewer than four fetal movements in an hour.

What Happens When You Go to the Hospital

-

If you think you have gone into labor, go directly to Labor and Delivery at your delivery hospital. DO NOT GO TO THE EMERGENCY ROOM FIRST.

-

If you are in active labor, the nurse will monitor the baby by putting a special belt on your belly. The belt “hears” and transmits the baby’s heartbeat. It will monitor your contractions, too. If the nurse cannot hear the baby well enough, a small internal wire monitor that attaches to the baby’s head will be placed. The monitor is easily removed after delivery and is safe for the baby.

-

The nurse will watch your contraction pattern and the baby’s heartbeat on a screen. This tells the doctors and nurses what is happening with your labor.

-

The nurse will check your cervix by doing a vaginal exam with her fingers. During most of your pregnancy, your cervix is closed. Your cervix will go from closed to 10 cm dilated (opened) as you have contractions.

You may begin pushing when your cervix is 10 cm dilated and you have the urge to push.

You may begin pushing when your cervix is 10 cm dilated and you have the urge to push.

Warning Signs of Complications

-

A constant low backache that happens with contractions.

-

Change in color or odor of your vaginal discharge.

-

More than 6 contractions in an hour if you are less than 37 weeks pregnant.

-

The baby is moving less than usual.

-

Pain when you urinate (pee).

-

Headaches that do not go away when you take Tylenol® (acetaminophen).

-

Blurred vision or vision changes.

Common Reasons for C-Sections

-

The baby is not tolerating the stress of labor well.

-

The baby is in the wrong position for birth (like breech).

-

You are not making progress in labor (your cervix is not dilating).

Pain Management in Labor

Epidural

An epidural contains medicine that will make your body numb from your breasts down. A small needle is placed in your lower back followed by a small catheter (a very small tube). The catheter is left in your back, and the needle is removed while you are in labor. The medication is given to you through this catheter. The medication never “runs out.”

Pros of Epidurals

Cons of Epidurals

-

The medicine can cause your blood pressure to drop which can cause changes in the baby’s heart rate. This is usually easily corrected.

-

You may not have the urge to push, and you may not push as effectively.

-

Labor may slow or stop; therefore, you might need medicine to restart your labor.

Spinal

This is very similar to an epidural but is used in a c-section. The medicine is given through a small needle into your spinal fluid which provides fast pain relief. The medicine lasts long enough for you to have your C-section.

The medicine lasts long enough for you to have your C-section.

General anesthesia

This is when you are given medicine to make you lose consciousness during a c-section. It is only used in emergencies and is generally avoided.

IV medicine

These medicines are given to you through an IV at the hospital. These medicines go into your bloodstream, but are safe for the baby. They can be tried first if you aren’t sure that you want an epidural. These medicines will not take the pain away, but they will “take the edge off.” These medicines can cause sedation and may affect breastfeeding.

Labor Log Worksheet

If you think you are in labor, record when contractions start and end below. Use the “Comments” area to write the strength of your contractions. This will help you decide if you should go to the hospital.

| Time Contraction Began | How long did it last? | How long from the beginning of one contraction to the beginning of the next | Comments (mile, moderate, sever) |

| Examples | |||

| 9:00 a. | 30 seconds | - | Massage helps |

| 9:08 a.m. | 45 seconds | 8 minutes | It was a hard one |

| When your labor begins, record your contractions below | |||

Teenage Pregnancy: Labor and Delivery (PDF)

HH-IV-142 6/14 Copyright 2014, Nationwide Children’s Hospital

Adolescent pregnancy

Adolescent pregnancy- All topics »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

- Resources »

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Multimedia

- Publications

- Questions & answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Popular »

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Monkeypox

- All countries »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

- Regions »

- Africa

- Americas

- South-East Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- WHO in countries »

- Statistics

- Cooperation strategies

- Ukraine emergency

- All news »

- News releases

- Statements

- Campaigns

- Commentaries

- Events

- Feature stories

- Speeches

- Spotlights

- Newsletters

- Photo library

- Media distribution list

- Headlines »

- Focus on »

- Afghanistan crisis

- COVID-19 pandemic

- Northern Ethiopia crisis

- Syria crisis

- Ukraine emergency

- Monkeypox outbreak

- Greater Horn of Africa crisis

- Latest »

- Disease Outbreak News

- Travel advice

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- WHO in emergencies »

- Surveillance

- Research

- Funding

- Partners

- Operations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Data at WHO »

- Global Health Estimates

- Health SDGs

- Mortality Database

- Data collections

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Dashboard

- Triple Billion Dashboard

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Highlights »

- Global Health Observatory

- SCORE

- Insights and visualizations

- Data collection tools

- Reports »

- World Health Statistics 2022

- COVID excess deaths

- DDI IN FOCUS: 2022

- About WHO »

- People

- Teams

- Structure

- Partnerships and collaboration

- Collaborating centres

- Networks, committees and advisory groups

- Transformation

- Our Work »

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Activities

- Initiatives

- Funding »

- Investment case

- WHO Foundation

- Accountability »

- Audit

- Budget

- Financial statements

- Programme Budget Portal

- Results Report

- Governance »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Election of Director-General

- Governing Bodies website

- Home/

- Newsroom/

- Fact sheets/

- Detail/

- Adolescent pregnancy

UNICEF/Versiani

© Credits

","datePublished":"2022-09-15T09:05:00. 0000000+00:00","image":"https://cdn.who.int/media/images/default-source/imported/adolescent-pregnancy.jpg?sfvrsn=792a9e8_0","publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"World Health Organization: WHO","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://www.who.int/Images/SchemaOrg/schemaOrgLogo.jpg","width":250,"height":60}},"dateModified":"2022-09-15T09:05:00.0000000+00:00","mainEntityOfPage":"https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy","@context":"http://schema.org","@type":"Article"};

0000000+00:00","image":"https://cdn.who.int/media/images/default-source/imported/adolescent-pregnancy.jpg?sfvrsn=792a9e8_0","publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"World Health Organization: WHO","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://www.who.int/Images/SchemaOrg/schemaOrgLogo.jpg","width":250,"height":60}},"dateModified":"2022-09-15T09:05:00.0000000+00:00","mainEntityOfPage":"https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy","@context":"http://schema.org","@type":"Article"};

Key facts

- As of 2019, adolescents aged 15–19 years in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) had an estimated 21 million pregnancies each year, of which approximately 50% were unintended and which resulted in an estimated 12 million births (1)(2).

- Data on childbirths among girls aged 10–14 are not widely available; limited available data from Angola, Bangladesh, Mozambique and Nigeria point to birth rates in this age group exceeding 10 births per 1000 girls as of 2020 (3).

- Based on 2019 data, 55% of unintended pregnancies among adolescent girls aged 15–19 years end in abortions, which are often unsafe in LMICs (1).

- Adolescent mothers (aged 10–19 years) face higher risks of eclampsia, puerperal endometritis and systemic infections than women aged 20–24 years, and babies of adolescent mothers face higher risks of low birth weight, preterm birth and severe neonatal condition.

- Preventing pregnancy among adolescents and pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity are foundational to achieving positive health outcomes across the life course and imperative for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) related to maternal and newborn health.

Overview

Adolescent pregnancy is a global phenomenon with clearly known causes and serious health, social and economic consequences. Globally, the adolescent birth rate (ABR) has decreased, but rates of change have been uneven across regions. There are also enormous variations in levels between and within countries. Adolescent pregnancy tends to be higher among those with less education or of low economic status. Further, there is slower progress in reducing adolescent first births amongst these and other vulnerable groups, leading to increasing inequity. Child marriage and child sexual abuse place girls at increased risk of pregnancy, often unintended. In many places, barriers to obtaining and using contraceptives prevent adolescents from avoiding unintended pregnancies. There is growing attention being paid to improving access to quality maternal care for pregnant and parenting adolescents. WHO works with partners to advocate for attention to adolescent pregnancy, to build an evidence base for action, to develop policy and programme support tools, to build capacity and to support countries to address adolescent pregnancy effectively.

Adolescent pregnancy tends to be higher among those with less education or of low economic status. Further, there is slower progress in reducing adolescent first births amongst these and other vulnerable groups, leading to increasing inequity. Child marriage and child sexual abuse place girls at increased risk of pregnancy, often unintended. In many places, barriers to obtaining and using contraceptives prevent adolescents from avoiding unintended pregnancies. There is growing attention being paid to improving access to quality maternal care for pregnant and parenting adolescents. WHO works with partners to advocate for attention to adolescent pregnancy, to build an evidence base for action, to develop policy and programme support tools, to build capacity and to support countries to address adolescent pregnancy effectively.

Scope of the problem

Every year, an estimated 21 million girls aged 15–19 years in developing regions become pregnant and approximately 12 million of them give birth (1).

Globally, ABR has decreased from 64.5 births per 1000 women in 2000 to 42.5 births per 1000 women in 2021. However, rates of change have been uneven in different regions of the world with the sharpest decline in Southern Asia (SA), and slower declines in the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) regions. Although declines have occurred in all regions, SSA and LAC continue to have the highest rates globally at 101 and 53.2 births per 1000 women, respectively, in 2021 (4).

There are enormous differences within regions in ABR as well. In LAC, for example, Nicaragua recorded the highest estimated ABR at 85.6 per 1000 adolescent girls in 2021, compared to 24.1 per 1000 adolescent girls in Chile (4). Even within countries, there are enormous variations, for example in Zambia the percentage of adolescent girls aged 15–19 who have begun childbearing (women who either have had a birth or are pregnant at the time of interview) ranged from 14. 9% in Lusaka to 42.5% in the Southern Province in 2018 (5). In the Philippines, this ranged from 3.5% in the Cordillera Administrative Region to 17.9% in the Davao Peninsula Region in 2017 (6).

9% in Lusaka to 42.5% in the Southern Province in 2018 (5). In the Philippines, this ranged from 3.5% in the Cordillera Administrative Region to 17.9% in the Davao Peninsula Region in 2017 (6).

While the estimated global ABR has declined, the actual number of childbirths to adolescents continues to be high. The largest number of estimated births to 15–19-year-olds in 2021 occurred in SSA (6 114 000), whereas far fewer births occurred in Central Asia (68 000). The corresponding number was 332 000 among adolescents aged 10–14 years in SSA, compared to 22 000 in South-East Asia (SEA) in the same year (4).

Context in which adolescent pregnancies occur

Studies of risk and protective factors related to adolescent pregnancy in LMICs indicate that levels tend to be higher among those with less education or of low economic status (7). Progress in reducing adolescent first births has been particularly slow amongst these vulnerable groups, leading to increasing inequity.

Several factors contribute to adolescent pregnancies and births. First, in many societies, girls are under pressure to marry and bear children. As of 2021, the estimated global number of child brides was 650 million: child marriage places girls at increased risk of pregnancy because girls who are married very early typically have limited autonomy to influence decision-making about delaying child-bearing and contraceptive use Second, in many places, girls choose to become pregnant because they have limited educational and employment prospects. Often in such societies, motherhood – within or outside marriage/union – is valued, and marriage or union and childbearing may be the best of the limited options available to adolescent girls.

Contraceptives are not easily accessible to adolescents in many places. Even when adolescents can obtain contraceptives, they may lack the agency or the resources to pay for them, knowledge on where to obtain them and how to correctly use them. They may face stigma when trying to obtain contraceptives. Further, they are often at higher risk of discontinuing use due to side effects, and due to changing life circumstances and reproductive intentions

They may face stigma when trying to obtain contraceptives. Further, they are often at higher risk of discontinuing use due to side effects, and due to changing life circumstances and reproductive intentions. Restrictive laws and policies regarding the provision of contraceptives based on age or marital status pose an important barrier to the provision and uptake of contraceptives among adolescents. This is often combined with health worker bias and/or lack of willingness to acknowledge adolescents’ sexual health needs.

Child sexual abuse increases the risk of unintended pregnancies. A WHO report dated 2020 estimates that 120 million girls aged under 20 years have experienced some form of forced sexual contact. This abuse is deeply rooted in gender inequality; it affects more girls than boys, although many boys are also affected. Estimates suggest that in 2020, at least 1 in 8 of the world’s children had been sexually abused before reaching the age of 18, and 1 in 20 girls aged 15–19 years had experienced forced sex during their lifetime.

The WHO report titled Violence against women prevalence estimates 2018 notes that “adolescents aged 15–19 years (24%) are estimated to have already been subjected to physical and/or sexual violence from an intimate partner at least once in their lifetime, and 16% of adolescent girls and young women aged 15–24 have been subjected to this violence within the past 12 months.”

Preventing adolescent pregnancy and childbearing as well as child marriage is part of the SDG agenda with dedicated indicators, including indicator 3.7.2, “Adolescent birth rate (aged 10–14 years; aged 15–19 years) per 1000 women in that age group,” and 5.3.1, “Proportion of women aged 20–24 years married before the age of 18 years.”

Strategies and interventions related to adolescent pregnancy have focused on pregnancy prevention. However, there is growing attention being paid to improving access to and quality of maternal care for pregnant and parenting adolescents. Available data on access paints a mixed picture. Access to quality care depends on the geographic context and the social status of adolescents. Even where access is not limited, adolescents appear to receive a lower quality of both clinical care and interpersonal support than adult women do.

Access to quality care depends on the geographic context and the social status of adolescents. Even where access is not limited, adolescents appear to receive a lower quality of both clinical care and interpersonal support than adult women do.

WHO response

WHO works with partners to advocate for attention to adolescents, build the evidence and epidemiologic base for action, develop and test programme support tools, build capacity, and pilot initiatives in the small but growing number of countries that began to recognize the need to address adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health. As a result of these collective efforts, adolescent health has moved to the centre of the global health and development agenda. In this changed context, WHO continues its work on advocacy, evidence generation, tool development and capacity building, while working with partners within and outside the United Nations system to support countries to address adolescent pregnancy effectively in the context of their national programmes.

Adolescent pregnancy is a global phenomenon with clearly known causes and serious health, social and economic consequences to individuals, families and communities. There is consensus on the evidence-based actions needed to prevent it. There is growing global, regional and national commitment to preventing child marriage and adolescent pregnancy and childbearing. Nongovernmental organizations have led the effort in several countries. In a growing number of countries, governments are taking the lead to put in place large-scale programmes. They challenge and inspire other countries to do what is doable and urgently needs to be done – now.

References

- Sully EA, Biddlecom A, Daroch J, Riley T, Ashford L, Lince-Deroche N et al., Adding It Up: Investing in Sexual and Reproductive Health 2019. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2020.

- Darroch J, Woog V, Bankole A, Ashford LS. Adding it up: Costs and benefits of meeting the contraceptive needs of adolescents.

New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2016.

New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2016. - United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Fertility among young adolescents aged 10 to 14 years. New York: UNDESA, PD, 2020.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects, 2019 Revision: Age-specific fertility rates by region, subregion and country, 1950-2100 (births per 1,000 women) Estimates. Online Edition [cited 2021 Dec 10]. Available from: https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Fertility/

- Zambia Statistics Agency, Ministry of Health (MOH) Zambia, and ICF. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2018. Lusaka, Zambia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: Zambia Statistics Agency, Ministry; 2018.

- Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) and ICF. Philippines National Demographic and Health Survey 2017. Quezon City, Philippines, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: PSA and CF; 2018.

- Chung, W.

H, Kim, ME., Lee, J. Comprehensive understanding of risk and protective factors related to adolescent pregnancy in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Journal of Adolescence. 2018; 69: 180-188.

H, Kim, ME., Lee, J. Comprehensive understanding of risk and protective factors related to adolescent pregnancy in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Journal of Adolescence. 2018; 69: 180-188.

Pregnancy and childbirth in adolescence - Adolesmed

About 16 million women aged 15-19 give birth each year, accounting for about 11% of all births worldwide. 95% of these births occur in middle- and low-income countries. The average adolescent birth rate in middle-income countries is more than twice that of high-income countries, and five times higher in low-income countries. nine0003

Adolescent birth rate

in Eastern Europe and Central Asia

(number of live births per 1,000 women aged 15-19)

Source: Database TransMonEE http://www.transmonee.org/ 2014,

* World Bank database http :// data .

worldbank . org / indicators

While rates of teenage pregnancy are declining globally, there are significant regional and national variances. Early pregnancy occurs more frequently among the poorest and least educated adolescents. For some of these girls, pregnancy and childbirth is an expected and desired event, but not for everyone. nine0003

Risks for mother and child

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), pregnancy, abortion and childbirth during adolescence are among the leading causes of maternal and child mortality worldwide. The probability of stillbirth and death of newborns in adolescent mothers is 1.5 times higher than in women aged 20–29 years.

Most adolescent girls are not yet physically developed enough for safe pregnancy and childbirth. In early adolescence, girls are still growing, and their pelvises do not reach the size of adult women's pelvises. As a result, there is a high probability of disruption of normal labor activity. During pregnancy, nutrient requirements increase, which, in turn, can lead to slower growth of the girl. Finally, even if a pregnant teenage girl is physically ready for pregnancy, she most often lacks social and emotional maturity. Often a young mother has a negative attitude towards her unborn child, she refuses to breastfeed her baby and cannot provide him with proper care. nine0003

As a result, there is a high probability of disruption of normal labor activity. During pregnancy, nutrient requirements increase, which, in turn, can lead to slower growth of the girl. Finally, even if a pregnant teenage girl is physically ready for pregnancy, she most often lacks social and emotional maturity. Often a young mother has a negative attitude towards her unborn child, she refuses to breastfeed her baby and cannot provide him with proper care. nine0003

Pregnancy and childbirth in women under 18–20 years of age often occur with complications such as early and late gestosis, miscarriage, the threat of spontaneous abortion (miscarriage), impaired uterine contractility during childbirth, the birth of underweight children, fetal hypoxia during pregnancy and childbirth. The complicated course of childbirth occurs in most young women in labor.

Pregnant teenage girls are more likely to smoke and drink alcohol than older women, which can lead to many problems for the baby after birth. Children born to teenage mothers are more likely to have low birth weight and more likely to experience health problems compared to children born to older mothers. Children of adolescent mothers often have an age delay in the development of psychomotor skills, a high level of diseases of the central nervous system. nine0003

Children born to teenage mothers are more likely to have low birth weight and more likely to experience health problems compared to children born to older mothers. Children of adolescent mothers often have an age delay in the development of psychomotor skills, a high level of diseases of the central nervous system. nine0003

Social consequences of pregnancy for the adolescent mother

Even if the birth ended without harm to the reproductive and somatic health of the young mother, the psychological and social consequences can be very undesirable. Pregnancy can leave a girl out of school and prevent her from continuing her education after giving birth, which can lead to long-term unemployment or limit opportunities for well-paid and decent work. nine0003

A pregnant teenage girl and a young mother often find themselves in a difficult life situation due to the partner's refusal to share responsibility for the child and the lack of support from parents and other loved ones. Unable to support themselves and their children, young mothers often leave their children in the care of the state.

Unable to support themselves and their children, young mothers often leave their children in the care of the state.

Young mothers are more likely than older mothers to develop postpartum depression, and may experience mental health problems due to lack of support from family and friends, isolation from friends and family members, financial difficulties. nine0003

Most teenagers do not plan or expect pregnancy. Therefore, the very suspicion of a possible pregnancy can cause psychological shock. A girl may be faced with a difficult choice to keep or terminate the pregnancy, and this, with any decision, can lead to depression, and under the most unfavorable circumstances, suicide.

Pregnancy during adolescence can be the cause of an unplanned marriage. Often, persons entering into marriage as teenagers are characterized by a lower level of education, social status, and official position. Incomes in such families are low, and the families themselves often break up due to various reasons, including socio-economic ones. nine0003

nine0003

Based on WHO materials, UNICEF manual "Adolescents at risk of HIV infection: A participant's book" Kyiv. 2012., and UNFPA manuals “Reproductive health counseling for adolescents and youth” Minsk, 2011.

Early teenage pregnancy and childbirth

For inquiries please contact:

Kyiv (Poznyaki)

st. A. Akhmatova 31

+38(096) 683-06-18

+38(063) 217-14-64

Sign up for a consultation

General information. In medical practice, there are episodes when young pregnant women need obstetric care (a primipara is called young if she gave birth before the age of 18). Her pregnancy proceeds, undoubtedly, in unusual conditions associated with the immaturity of adaptive mechanisms.

The heavy burden on the immature, fragile body due to pregnancy is a serious test. nine0003

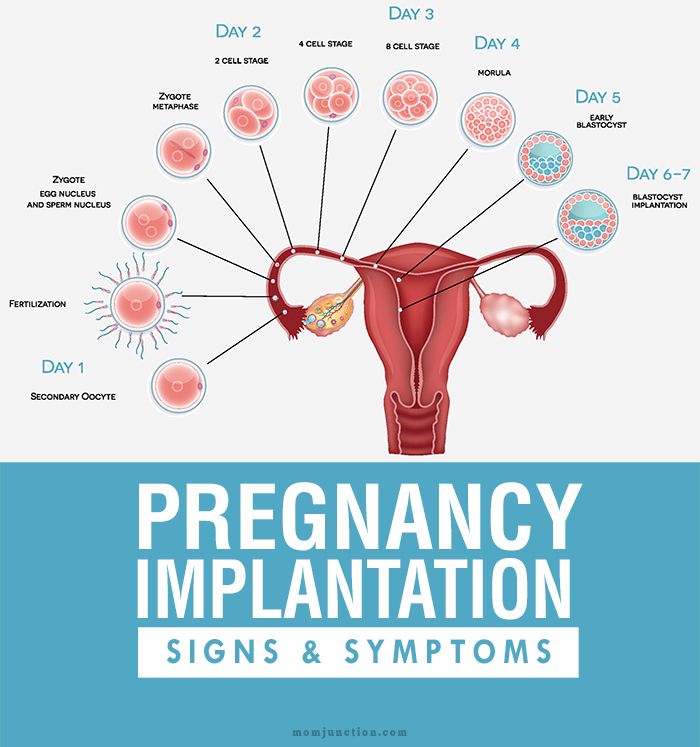

Pregnancy in girls under 8 years of age becomes possible in case of accelerated puberty. At the age of 9 to 16 years, pregnancy can occur even in cases where the dynamics of puberty is not ahead of the norm.

At the age of 9 to 16 years, pregnancy can occur even in cases where the dynamics of puberty is not ahead of the norm.

Classification of pregnancy. A distinction is made between pregnancy that occurred before puberty (violent ovulation occurs long before puberty) and pregnancy in a woman who has already entered puberty. In these two groups, the features of the course of pregnancy and childbirth and, of course, the tactics of their management differ significantly. In particular, during pregnancy and childbirth during puberty, there are fewer complications than at a younger age. nine0003

In addition, cases of pregnancy that occur in girls without signs of precocious puberty (on the one hand) and those who have them (on the other) are to be distinguished. With premature puberty, pregnancy often occurs with its true variant than with pathological (on the basis of a tumor, etc.).

The effect of pregnancy on a girl's body. There is no doubt that pregnancy, if it occurs at a young age, accelerates the processes of somatic and puberty. The secretion of estrogen and progesterone is not inferior to that of adult pregnant women. nine0003

The secretion of estrogen and progesterone is not inferior to that of adult pregnant women. nine0003

Changes in the bone pelvis are especially evident, which during pregnancy in 13-15-year-olds can reach the size characteristic of 16-18 years old. However, the outer conjugate increases more slowly than the other outer dimensions. Of the young primiparous, 10.7% of births proceed in the presence of an anatomically narrowed pelvis; at the same time, to a greater extent than in adult women, hydrophilicity and elasticity of the ligamentous apparatus, symphysis and cartilaginous zones are expressed. All this provides some flexibility of the bone ring. nine0003

We have to observe how in a girl without pronounced secondary sexual characteristics before pregnancy, they appear even if the pregnancy was terminated at an early date.

As for the mental reactions of young pregnant women, according to our observations, they correspond to age, but do not outstrip it. Psychopathies and psychoses are rare, mostly with rape (reactive psychosis). A number of character traits revealed in this group are explained by the shortcomings of education. So, after polling 79underage pregnant women, they stated the predominance of their independent character, a tendency to experiment, impracticality, poverty of the emotional world, bad manners.

A number of character traits revealed in this group are explained by the shortcomings of education. So, after polling 79underage pregnant women, they stated the predominance of their independent character, a tendency to experiment, impracticality, poverty of the emotional world, bad manners.

Features of the course of pregnancy in adolescence. Pregnancy proceeds, as a rule, favorably. Its duration is 38 ± 0.9 weeks, i.e., slightly less than in adult women. Prematurity is 3%. Overlapping is almost not observed. Multiple pregnancy in young is less common (1: 100) than in older age groups. nine0003

Early toxicosis was diagnosed by us in isolated cases. Complication of pregnancy by late toxicosis is observed, according to our data, in 0.5%, which is 20 times less than usual. In the literature, there are completely different figures for the frequency of late toxicosis: 46-65.29%.

According to the opinion of the cited authors, pregnancy at a young age is generally complicated by 40-70%. This is significantly different from our data (no more than 5%), as well as from the opinion of W. Stockel, M. Shash and L. Kovacs (1967). Such a significant difference in the nature of the course of pregnancy is undoubtedly due to different tactics of management, in particular, the regular medical supervision adopted in the IMMI clinic throughout pregnancy and carefully observed preventive hospitalization. nine0003

This is significantly different from our data (no more than 5%), as well as from the opinion of W. Stockel, M. Shash and L. Kovacs (1967). Such a significant difference in the nature of the course of pregnancy is undoubtedly due to different tactics of management, in particular, the regular medical supervision adopted in the IMMI clinic throughout pregnancy and carefully observed preventive hospitalization. nine0003

Diagnosis of early pregnancy. Diagnosis of pregnancy at a young age is based on the identification of the same alleged, probable and undoubted signs as in adult women, however, the diagnosis is often established with a delay, that is, with the appearance of precisely reliable signs.

The main obstacle to correct and timely diagnosis is the young pregnant woman herself, who, due to a number of circumstances, either does not suspect pregnancy or hides the appearance of dubious (subjective) signs of pregnancy. Sometimes a person whom the girl especially trusts learns about pregnancy for the first time: a school teacher, a pioneer leader, etc.

Often, the first diagnosis of pregnancy is made by the district pediatrician during examination and palpation of the abdomen.

Diagnostic errors in establishing pregnancy at a young age are a fairly common phenomenon. Even at the stage of acquaintance with the anamnesis, the assurances of the relatives accompanying the girl that "pregnancy is impossible here" lead to a medical error.

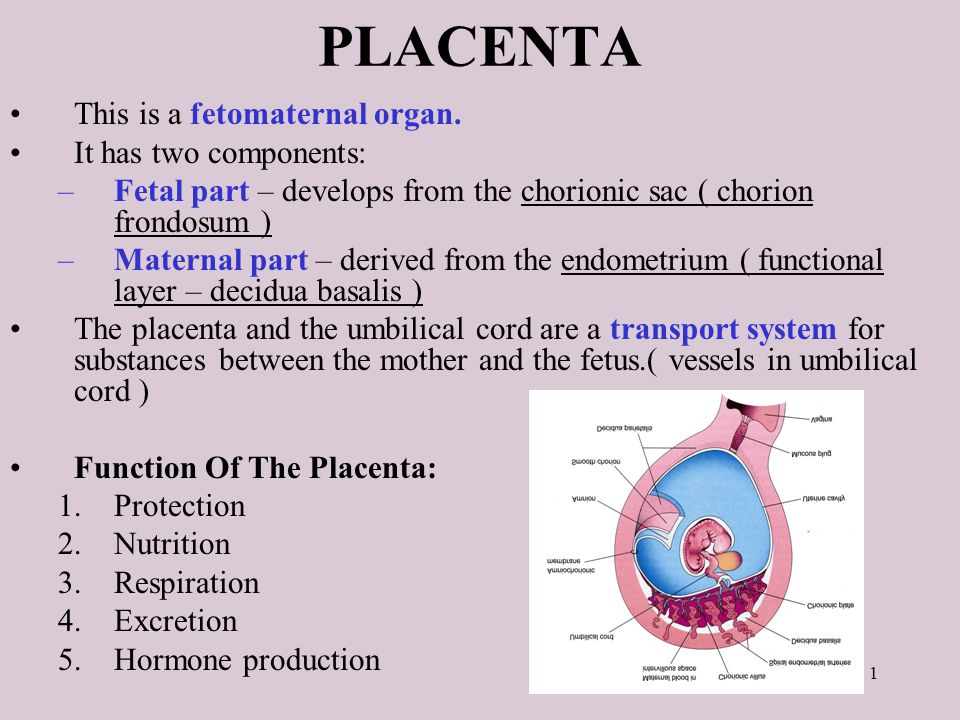

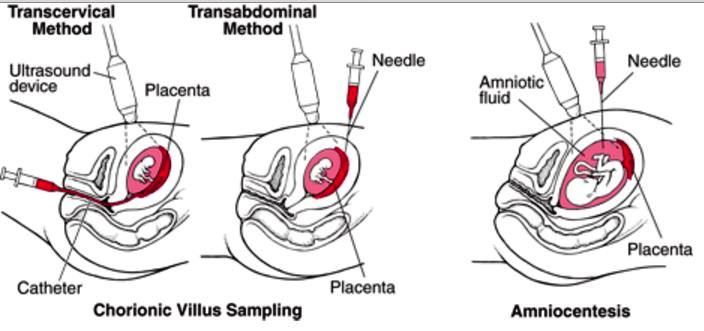

The integrity of the hymen or the absence of its integrity is not of decisive diagnostic value. Characteristically, in the first trimester of pregnancy, there is insufficient softening of the uterus, some lag in its size from the timing of the delay in menstruation, and a moderate severity of a group of probable signs based on ascertaining softening of the isthmus. nine0109 In addition to the generally accepted clinical diagnostic methods, one should not forget about the existence of such additional methods as the determination of placental lactogen, chorionic gonadotropin, abdominal radiography, ultrasound diagnostics, phono- and electrocardiography of the fetus.

In the process of differential diagnosis, it becomes necessary to distinguish pregnancy from the following diseases: anomalies in the development of the uterus, kidney prolapse, tumors of the small pelvis or abdominal cavity, obesity (often accompanied by amenorrhea), primary ectopic pregnancy (often in the right fallopian tube). nine0003

Pregnancy management. The very fact of establishing a pregnancy diagnosis imposes additional responsibility on the doctor for the fate of a young mother and her child. First of all, we have to resolve the issue of the possibility of carrying pregnancy and giving birth with minimal damage to health. The decision must be strictly individual. The age of the girl and the gestational age are decisive. Stereotypical decisions aimed at, say, unconditional termination of pregnancy can be harmful, as there are situations, especially in the second trimester, in which the risk associated with termination outweighs the health damage from the burden of pregnancy and childbirth. nine0003

nine0003

In healthy girls of 15-17 years of age in the first trimester, a positive decision on the issue of leaving the pregnancy is preferable, because pregnancy and childbirth are usually successful. At the same time, the risk of complications associated with induced abortion at a young age is greater than in adult women. In the presence of serious illnesses or the occurrence of complications that threaten health, an abortion is undertaken according to the relevant indications.

If a schoolgirl has a full term pregnancy, then school attendance is undesirable for ethical and pedagogical reasons. In addition, the study load adversely affects the formation of gestational dominance and can be an etiological moment in the development of late toxicosis of pregnant women. We must not forget that the need for frequent hospitalization also does not favor the continuation of studies. nine0003

The girl is registered in the antenatal clinic and periodically (at least 3 times during pregnancy) goes to the antenatal department, where an in-depth monitoring of her health and the development of the fetus is carried out. Preventive or curative measures are taken as needed; in particular, foci of latent infection are eliminated and the vagina is sanitized. Particular attention in the hospital is given to physio-psycho-prophylactic preparation for childbirth, since this is difficult to implement in the antenatal clinic. nine0003

Preventive or curative measures are taken as needed; in particular, foci of latent infection are eliminated and the vagina is sanitized. Particular attention in the hospital is given to physio-psycho-prophylactic preparation for childbirth, since this is difficult to implement in the antenatal clinic. nine0003

Given that at a young age, childbirth occurs 1-2 weeks earlier than in adult women, the last admission to the hospital should be made no later than 36-37 weeks of pregnancy. During this time, the next examination is carried out, preparations for childbirth are carried out and a plan for their maintenance is drawn up.

Course of childbirth. The course and outcomes of childbirth significantly depend on the girl's belonging to a certain age group. If at the age of 14 and younger the percentage of severe complications is high (15), then in the group of 15-17 years the percentage of complications decreases sharply (1-2). nine0003

In parturient women under 14 years of age, the following structure of the main complications in childbirth can be outlined:

a) clinical discrepancy between the fetal head and the mother's pelvis,

b) weakness of labor activity,

c) injuries of the birth canal,

d) hypotonic bleeding (listed in descending order).

At the same time, in women in labor 15-17 years old, the structure of complications is somewhat different:

a) rapid delivery,

b) primary weakness of labor,

c) rupture of the cervix and perineum,

d) hypotonic bleeding.

Thus, most of the complications owe their genesis to a violation of the contractility of the uterus, due to both the immaturity of the regulatory links and the inferiority of the executive tissues (myometrium).

Birth management. Delivery of young pregnant women should be carried out in highly qualified institutions, preferably those with specialists with relevant experience and round-the-clock anesthesia and pediatric services. The doctor and midwife require a special approach to the young woman in labor, dictated by the need to reckon with the unusual position, emotional lability, low threshold of pain sensitivity and the constant threat of complications for the mother and fetus. nine0003

In the first stage of labor, in parallel with careful monitoring of the dynamics of structural changes in the cervix (external methods are preferred, for example, the Rogovin method), it is necessary to prescribe antispasmodic agents, thereby reducing pain.

The use of anesthesia is based on a sufficient choice of means. The widespread use of painkillers is not justified in cases where there is a high possibility of a clinical discrepancy between the fetal head and the mother's pelvis. For the same reasons, the appointment of strong uterine stimulants is contraindicated. nine0003

Surgical interventions among young women in labor are undertaken no more often than usual in clinical practice: perineotomy - in 12%, obstetric forceps - in 1%, caesarean section - in 0.5%. Vacuum extraction of the fetus is not used at all. Those authors who point to a high incidence of late toxicosis in young pregnant women, naturally, give a high percentage of operative delivery (17-22%).

In pregnant women under the age of 14 years (especially younger than 12), it is more likely than at an older age to tend to delivery by caesarean section in a planned manner at term 39-40 weeks. The determining circumstances are the size of the pelvis, the nature of the presentation, the estimated weight of the fetus and the state of health of the girl. 1-3 hours before the production of caesarean section, the fetal bladder is opened. This achieves gradual emptying of the uterus and, consequently, the prevention of hypotonic bleeding and lochiometers.

1-3 hours before the production of caesarean section, the fetal bladder is opened. This achieves gradual emptying of the uterus and, consequently, the prevention of hypotonic bleeding and lochiometers.

If the doctor has a hope for a spontaneous completion of labor, then at first he conducts labor conservatively; in the future, the appearance of complications makes it necessary to proceed with operative delivery. With modern anesthesia, a caesarean section poses no greater risk for a pregnant woman under 14 years of age than, for example, delivery per vias naturales or a fetus-destroying operation. In addition, during the abdominal surgery, it is possible to revise the pelvic organs, in particular, to assess the condition of the ovaries. nine0003

Transfer to the postpartum department after spontaneous delivery and examination of the soft birth canal is usually carried out not after 2-4 hours, but after 10-12 hours due to fear of not noticing the onset of hypotonic bleeding.

m.

m.