Pregnancy shots for blood types

Rh factor: Rh negative and RhoGAM shot explained

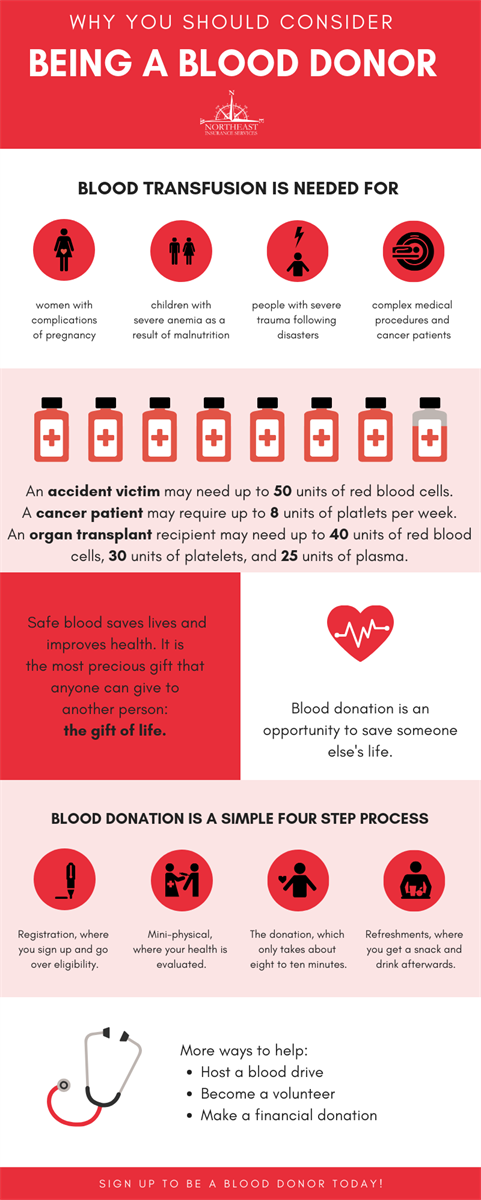

Rh factor is a protein that most people have on the surface of their red blood cells. If you don't have it, you're Rh negative, and you'll need to take certain precautions during your pregnancy. In most cases you'll need to get injections of Rh immune globulin (RhoGAM) to keep your body from developing antibodies to your baby's red blood cells. If your body has already developed antibodies (from a previous pregnancy, for example), it's too late to get RhoGAM, but your caregiver will carefully monitor your baby.

What is Rh factor?

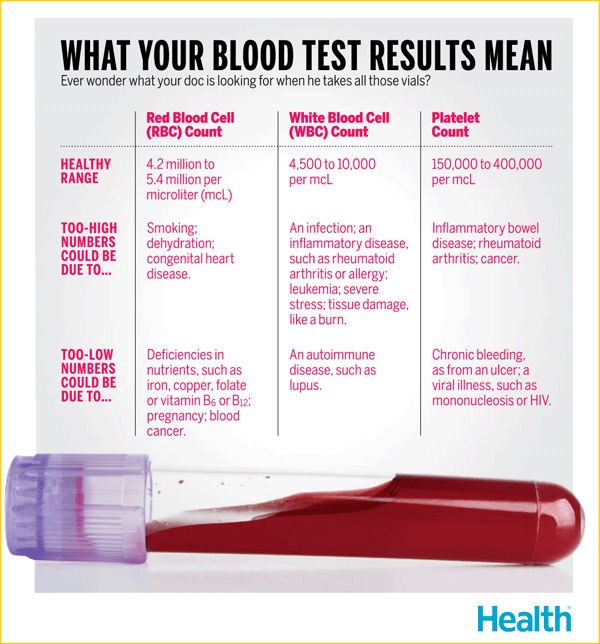

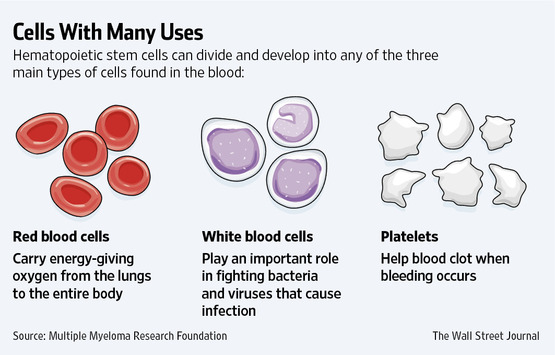

Rh factor (short for Rhesus factor) is a protein that most people have on the surface of their red blood cells.

At your first prenatal visit, your blood will be tested to determine your blood type and your Rh status. If you do have the Rh factor, as most people do, your status is Rh positive. (About 85 percent of Caucasians are Rh positive, as are 90 to 95 percent of African Americans and over 95 percent of American Indians and Asian Americans. )

If you don't have Rh factor, you're Rh negative, and you'll need to take certain precautions during your pregnancy.

Why is it a problem if I'm Rh negative?

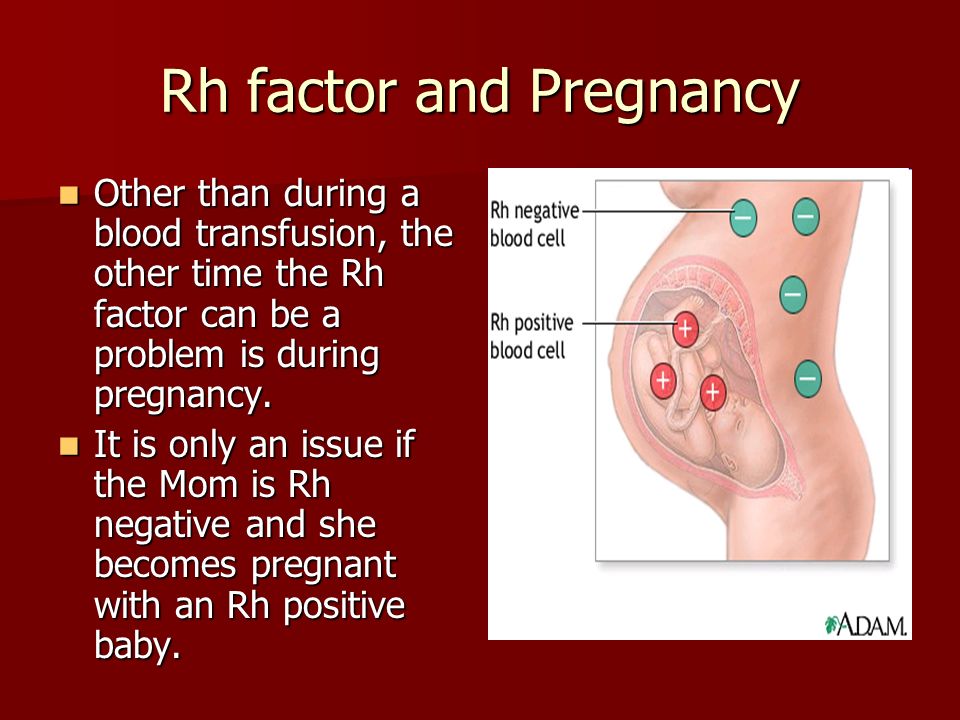

If you're Rh negative, there's a good chance that your blood could react with your baby's blood, which is likely to be Rh positive. (This is called Rh incompatibility.) You probably won't know this for sure until your baby is born, but in most cases you have to assume it's positive, just to be safe.

Being Rh incompatible isn't likely to harm you or your baby during your first pregnancy. But if your baby's blood directly interacts with yours (as it can at certain times during pregnancy and at birth), your immune system will start to produce antibodies against this Rh positive blood. If that happens, you'll become Rh sensitized — and the next time you're pregnant with an Rh positive baby, those antibodies may attack your baby's red blood cells.

How can I protect my baby if I'm Rh negative?

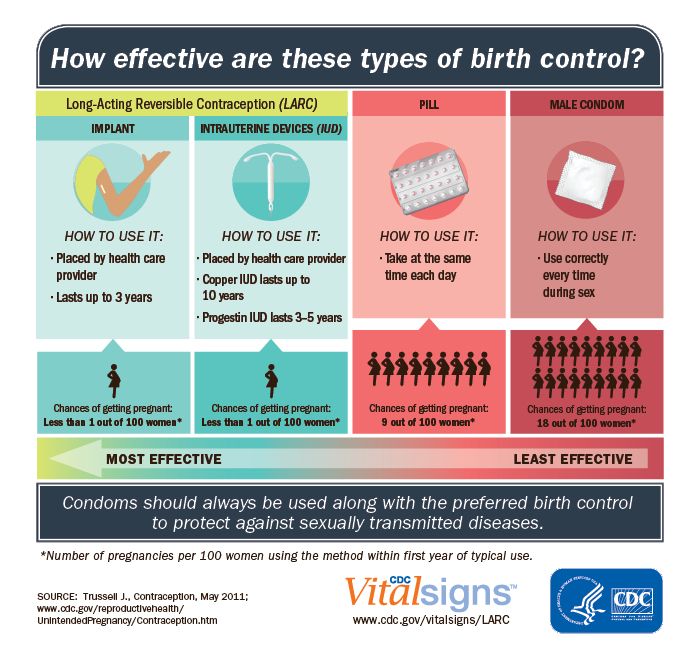

Fortunately, you can avoid becoming Rh sensitized by getting an injection of a drug called Rh immune globulin (RhoGAM). Doctors give it whenever there's a chance that your blood has been exposed to the baby's blood and also preventatively in the early third trimester and postpartum.

Doctors give it whenever there's a chance that your blood has been exposed to the baby's blood and also preventatively in the early third trimester and postpartum.

If you're Rh negative and you've been pregnant before but didn't get this shot, another routine prenatal blood test will tell you whether you already have the antibodies that attack Rh positive blood. (You could have them even if you miscarried the baby, had an abortion, or had an ectopic pregnancy.)

If you don't have the antibodies, then the shot will keep you from developing them.

If you do have the antibodies, it's too late to get the shot. Your provider will make a plan for you and your baby to be monitored through your pregnancy with blood work first and then possibly special ultrasound tests to detect fetal anemia. You may be referred to a maternal-fetal medicine specialist for consultation or treatment.

Advertisement | page continues below

What are the chances that my baby and I are Rh incompatible?

Rh status is inherited. If your baby's father is Rh positive — as most people are — you have about a 75 percent chance of having an Rh positive baby. So if you're Rh negative, it's likely that you and your baby are Rh incompatible. In fact, your healthcare practitioner will assume you are, just to be safe.

If your baby's father is Rh positive — as most people are — you have about a 75 percent chance of having an Rh positive baby. So if you're Rh negative, it's likely that you and your baby are Rh incompatible. In fact, your healthcare practitioner will assume you are, just to be safe.

There's no harm in getting the Rh immune globulin shot, even if it turns out that it wasn't necessary.

How could my baby's blood leak into mine?

Normally during pregnancy, your baby's blood stays separate from yours. The placenta allows for exchange of oxygen, nutrients, and fluids, but not red blood cells. In fact, your blood is not likely to intermingle in any significant way until you give birth. That's why Rh incompatibility is usually not a problem for your first baby: If your blood doesn't mix until you're in labor, the baby will be born before your immune system has a chance to produce enough antibodies to cause problems.

Times when your baby's blood can leak into yours:

Delivery: You'll need a shot after the birth if your newborn is found to be Rh positive. Since it's possible you were exposed to your baby's blood during delivery, the shot will prevent your body from making antibodies that could attack an Rh positive baby's blood during a future pregnancy.

Since it's possible you were exposed to your baby's blood during delivery, the shot will prevent your body from making antibodies that could attack an Rh positive baby's blood during a future pregnancy.

(Your delivery team will take a blood sample from your newborn's heel or from their umbilical cord just after they're born to test for several things, including Rh factor, if necessary.) Without treatment, there's about a 15 percent chance that you'll produce antibodies, but with treatment, the chance is close to 0 percent.

In the third trimester: A small number of Rh negative women (about 2 percent) somehow develop antibodies to their baby's Rh positive blood during their third trimester. So you'll also be given shot of Rh immune globulin at 28 weeks that covers you until childbirth.

Other opportunities: And you'll need a shot any other time that your baby's blood might mix with yours, including if you have:

- Amniocentesis

- Chorionic villus sampling (CVS)

- A miscarriage

- An abortion

- An ectopic pregnancy

- A molar pregnancy

- A stillbirth

- An external cephalic version (ECV, a procedure to manually turn a baby who is in breech position)

- An injury to your abdomen during pregnancy

- Vaginal bleeding

If you find yourself in any of these situations, remind your caregiver that you're Rh negative, and make sure you get the shot within 72 hours.

How does the shot prevent me from developing antibodies?

The Rh immune globulin shot consists of a small dose of antibodies, collected from blood donors. These antibodies kill any Rh positive blood cells in your system, which seems to keep your immune system from developing its own antibodies. The donated antibodies are just like yours, but the dose isn't large enough to cause problems for your baby.

This is called passive immunization: For it to work, you need to get the shot no more than 72 hours after any potential exposure to your baby's blood. The protection will last for 12 weeks. If your practitioner suspects that more than an ounce of your baby's blood mixed with yours (say, if you've had an accident), you might need a second shot. If necessary, special blood tests can be done to measure exactly how much fetal blood has mixed with yours.

You'll get the injection in the muscle of your arm or buttocks. You may have some soreness at the injection site or a slight fever. There are no other known side effects. The shot is safe whether your baby's blood is really Rh positive or not.

There are no other known side effects. The shot is safe whether your baby's blood is really Rh positive or not.

What will happen to my baby if I develop the antibodies?

First, keep in mind that this is highly unlikely if you're receiving good prenatal care and are being treated with Rh immune globulin when necessary. Even without treatment, your chances of developing the antibodies and becoming Rh sensitized are only about 50 percent even after several Rh incompatible pregnancies.

If you didn't get the shot, though, and you became Rh sensitized and your next baby is Rh positive, your antibodies can cross the placenta and attack the Rh factor in your baby's Rh positive blood as if it's a foreign substance, destroying his red blood cells and causing significant anemia. In rare cases, a more serious condition, called hemolytic disease of the fetus (HDFN) can develop if an Rh negative mother does not receive Rh immune globulin treatment and her child is positive. This condition greatly increases the risk of severe anemia, jaundice, congestive heart failure, or even death.

The good news is that doctors are finding new ways to save babies who develop Rh disease. Your practitioner can monitor your level of antibodies and keep tabs on your baby's condition during pregnancy to see whether they're developing the disease. She may check on the condition of your baby's red blood cells using Doppler ultrasound or amniocentesis.

If your baby is doing well, you might be able to carry them to term without complications. After birth, they may be given what's called an exchange transfusion to replace their diseased Rh positive red blood cells with healthy Rh negative cells. This stabilizes the level of red blood cells and minimizes further damage by antibodies circulating in their bloodstream.

Over time these donated Rh negative blood cells will die off and all your baby's red blood cells will be Rh positive again, but by that time, the attacking antibodies will be gone.

If your baby's in distress or severely anemic, they might be delivered early or given transfusions through the umbilical cord. The survival rate for babies who receive a transfusion in utero is as high as 80 to 100 percent, unless they have hydrops (a complication caused by severe anemia), in which case the chances of survival are about 40 to 70 percent.

The survival rate for babies who receive a transfusion in utero is as high as 80 to 100 percent, unless they have hydrops (a complication caused by severe anemia), in which case the chances of survival are about 40 to 70 percent.

What about future pregnancies?

Once you're sensitized, you have the antibodies forever. And you produce more with each pregnancy, so the risk of Rh disease is higher for each subsequent baby.

Your Rh status is one of many things your early blood test will determine. Learn what else your provider will be checking in our article on Common first trimester blood tests.

Learn more:

- Prenatal tests: An overview

- Checklist: First trimester

- Growth chart of baby's length and weight

Rh Incompatibility - familydoctor.org

Rh incompatibility is a mismatched blood type between a pregnant mother and the baby she is carrying. It is rarely serious or life threatening, thanks to early diagnosis and treatment during pregnancy.

Rh factor is a protein located in red blood cells. People who have that protein are Rh-positive. Most people are Rh-positive. People without the protein are Rh-negative. You inherit your blood type from your parents.

If an Rh-positive baby’s blood passes to its Rh-negative mother during pregnancy (or delivery), the mother’s body will attack the baby’s red blood cells. Typically, this is not a concern for a live birth with a first pregnancy. It poses a greater risk in later pregnancies. This is because the mother develops antibodies to attack Rh-positive blood types in future children.

Rh incompatibility isn’t harmful to the pregnant mother. However, it can cause mild to serious medical problems for the baby. Doctors treat the condition by injecting the mother with a Rh incompatibility medicine that protects the baby’s red blood cells.

Path to improved health

In most cases, Rh incompatibility is avoidable with preventive care. Your doctor will check your blood type during your first pregnancy visit. If you have Rh-negative blood, you will be given an injection of Rh immunoglobulin. This happens at around week 28 of your pregnancy. It will be done again within 72 hours of your baby’s birth. It may also be done after a miscarriage, an abortion, or an amniocentesis (a gene screening test done during pregnancy). These are all cases in which the mother and baby’s blood could mix.

If you have Rh-negative blood, you will be given an injection of Rh immunoglobulin. This happens at around week 28 of your pregnancy. It will be done again within 72 hours of your baby’s birth. It may also be done after a miscarriage, an abortion, or an amniocentesis (a gene screening test done during pregnancy). These are all cases in which the mother and baby’s blood could mix.

According to the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), all pregnant women should have blood typing and Rh testing on their first visit to their doctor for pregnancy care. AAFP recommends retesting between the 24th and 28th weeks of pregnancy.

Rh immunoglobulin will not harm your baby. The injection may cause you to have mild soreness around the injection site. For some pregnant women, common side effects of the medicine include

- Headache

- Mild fever

- Mild pain

- Swelling or redness at the site of the injection

More serious side effects include:

- Severe allergic reaction

- Back pain

- Problems with your urine

- Rapid heartbeat

- Nausea

- Fever

- Trouble breathing

- Unexplained weight gain

- Swelling

- Fatigue

- Yellowing of the eyes or skin

Things to consider

Most Rh-positive babies born from a first-time pregnancy to an Rh-negative mother are not affected by Rh incompatibility. This is because the baby’s blood doesn’t usually pass to the mother’s bloodstream until the time of the birth (vaginal or cesarean section). Exceptions may occur if the mother:

This is because the baby’s blood doesn’t usually pass to the mother’s bloodstream until the time of the birth (vaginal or cesarean section). Exceptions may occur if the mother:

- Had a previous pregnancy that ended in miscarriage or had an abortion.

- Had pregnancy screening tests, such as amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (genetic tests that require inserting a needle into the mother’s womb to sample the baby’s cells).

- Had bleeding during her pregnancy.

- Had to have the baby manually rotated from a breech position before her labor started.

- Experienced a blunt trauma injury to her abdomen during her pregnancy.

Once an Rh-positive baby’s blood enters an Rh-negative mother’s bloodstream, a mother’s future Rh-positive babies are at risk for certain medical problems (unless the mother received an Rh immunoglobulin injection). Without that preventive treatment, Rh incompatibility destroys your baby’s red blood cells (hemolytic anemia) during pregnancy. Red blood cells are filled with iron-rich protein (hemoglobin) that supplies oxygen to your baby. Your baby’s red blood cells die faster than his or her body can make new ones.

Red blood cells are filled with iron-rich protein (hemoglobin) that supplies oxygen to your baby. Your baby’s red blood cells die faster than his or her body can make new ones.

Without enough red blood cells, your newborn baby won’t get enough oxygen. The baby could suffer from mild conditions, such as anemia (low blood count) and jaundice (yellowing of the eyes and skin). It could also lead to more serious conditions, such as brain damage and heart failure. It’s possible for a baby to die during the pregnancy if too many of their red blood cells have been destroyed.

Questions to ask your doctor

- Does my unborn baby’s blood have to be tested during pregnancy or just mine?

- Does the father’s blood type matter?

- Is blood typing done on pregnant women of all ages?

- What happens if I do not receive the final Rh immunoglobulin injection before my baby is born?

Resources

National Institutes of Health, MedlinePlus: Rh incompatibility

National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Rh Incompatibility

Copyright © American Academy of Family Physicians

This information provides a general overview and may not apply to everyone. Talk to your family doctor to find out if this information applies to you and to get more information on this subject.

Talk to your family doctor to find out if this information applies to you and to get more information on this subject.

Pregnancy and Rhesus

- Specialist doctor's advice.

- PCR diagnostics - determination of the Rh factor of the fetus in the blood of a Rh-negative mother by a genetic method.

- Phenotyping.

- Intravenous administration of immunoglobulin by dosed titration.

- Lymphocytoimmunotherapy (LIT).

- Resonator introduction.

All parents dream of having a healthy baby. Many risks associated with the health of the baby are now manageable. This means that some, even very serious and dangerous diseases are preventable, the main thing is not to waste time. For example, the situation associated with the development of hemolytic disease in the fetus and newborn. Many have heard that in the presence of Rh-negative blood in the mother, it is possible to develop an immunological conflict between the mother and the fetus in the Rh system, which later causes a severe hemolytic disease, from which the baby may already suffer in utero, but few can explain in detail what is it, and what to do if it directly concerns you.

First, let's figure out what the Rh factor is.

Rh factor is a special complex of proteins (also called D-antigen) that is located on the surface of red blood cells. It can be determined by laboratory methods (blood test). Most people in the population have the D antigen. Such people are said to be Rh-positive. A minority of the population (about 15-18%) do not have D antigen in their blood cells; such people are called Rh-negative.

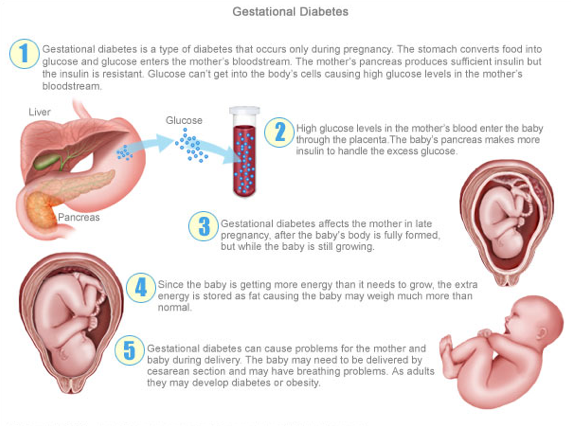

Rh factor is inherited, and a child can inherit it from both mother and father. If the mother is Rh-negative and the father is Rh-positive, there is a high chance that the child will inherit the father's Rh-positive father. Then it turns out that the mother does not have the D-antigen in the blood, but the fetus has it. The mother's immune system can perceive the fetal erythrocytes penetrating into her blood as foreign, and begin to fight them by synthesizing antibodies. These antibodies have a very low molecular weight, are able to cross the placenta into the fetal circulation and destroy fetal red blood cells, causing hemolytic disease in the fetus. Such a pathological condition in which the synthesis of antibodies occurs is called Rh immunization.

Such a pathological condition in which the synthesis of antibodies occurs is called Rh immunization.

Why is Rh immunization dangerous?

The main role of erythrocytes is the transport of oxygen to the organs and tissues of the body. With the massive destruction of these cells, the organs of the fetus begin to experience oxygen starvation. But that is not all. With the breakdown of red blood cells, a special substance is released - bilirubin, which has a toxic effect on the heart, liver, nervous system of the fetus. Bilirubin turns the baby's skin yellow (“jaundice”). In severe cases, bilirubin, exerting its toxic effect on brain cells, causes irreversible consequences, up to severe disability and death of the baby.

The level of danger increases with each successive pregnancy. The mother’s immune system has the ability to “remember” foreign proteins (Rhesus antigen of the fetus) and, during repeated pregnancy, responds with an even faster and more massive release of antibodies that can very quickly penetrate the placenta into the baby’s bloodstream and lead to severe intrauterine suffering and even death of the baby even before birth.

Therefore, the risk factors for an Rh-negative woman are:

- Previous birth of an Rh-positive child (unless a special drug, anti-Rhesus immunoglobulin, was administered after the birth)

- Past fetal deaths

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Miscarriages and abortions

- Transfusion of Rh-incompatible blood before pregnancy

The first pregnancy in an Rh-negative woman is usually uneventful. Therefore, there is a tendency to keep the first pregnancy, in no case interrupting it, unless there are serious medical indications for this.

What to do?

Fortunately, it should be noted that worldwide the incidence of hemolytic disease of the fetus in newborns due to Rh conflict is decreasing. And this happens because the methods of Rh prophylaxis are widely introduced into practice, which is carried out for Rh-negative women during pregnancy and after the birth of a Rh-positive baby. Yes, as in the case of all diseases without exception, it is easier to prevent a problem than to treat the consequences of an already developed severe Rh conflict.

To date, the only (and effective) preventive method to prevent this pathology is the introduction of a special drug - anti-D-immunoglobulin.

Preventive vaccination is carried out twice - during pregnancy (prenatal prophylaxis) and immediately after childbirth (postnatal prophylaxis).

Let's dwell on this in more detail.

The prenatal prophylaxis step is intended to protect an existing pregnancy.

If the pregnancy proceeds without complications ("everything goes according to plan"), the woman is given prophylactic administration of anti-D-immunoglobulin at 28-32 weeks of pregnancy. A specially set dose is introduced, which provides protection for the baby until the end of pregnancy. This is planned prenatal prophylaxis.

Emergency prenatal prophylaxis is carried out in the event of dangerous situations that greatly increase the risk of developing a Rh conflict. These situations include:

- Complications of pregnancy: miscarriage; threatened miscarriage with bloody discharge

- Abdominal injury during pregnancy (e.

g. after a fall or car accident)

g. after a fall or car accident) - Therapeutic and diagnostic interventions during pregnancy: amniocentesis, chorionic biopsy, cordocentesis

In these cases, additional administration of the drug may be required to protect the fetus.

Stage postpartum prophylaxis aims to protect your future pregnancy.

If the baby is found to be Rh-positive after delivery, the mother is given another injection of anti-D-immunoglobulin. The drug should be administered as soon as possible, no later than 72 hours after delivery. If the vaccination is given later, its effectiveness is reduced and you cannot be sure that you did everything that was necessary to protect your next baby.

Attention! Women should receive the same prophylaxis with anti-D-immunoglobulin if:

- a miscarriage occurred at 5-6 weeks of gestation or more

- an abortion was performed at 5-6 weeks of gestation or more

- an operation was performed for an ectopic pregnancy

pregnancy and your unborn child. The introduction of the drug must also be made in the first 72 hours.

The introduction of the drug must also be made in the first 72 hours.

The protective effect of anti-D-immunoglobulin lasts only up to 12 weeks, therefore, with each subsequent pregnancy, repeated prophylactic administration is necessary.

Don't worry if you are Rh negative. Follow all the doctor's instructions and you will have a healthy baby!

Kozlyakova Olga Vladimirovna,

Head of Obstetric Immunohematology GCT

Candidate of Medical Sciences 9016

? WHO Responsible

1. Can pregnant women be vaccinated against COVID-19?

Short answer: yes. Pregnant women can be vaccinated against COVID-19. Vaccines provide reliable protection against serious diseases caused by coronavirus. Pregnant women, if not already vaccinated, should have access to WHO-approved vaccines, as COVID-19 during pregnancy puts them at higher risk of serious illness and premature birth.

Pregnant women, if not already vaccinated, should have access to WHO-approved vaccines, as COVID-19 during pregnancy puts them at higher risk of serious illness and premature birth.

Growing evidence of safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccinationduring pregnancy suggests that the benefits of vaccination during pregnancy outweigh the potential risks. Vaccination against COVID-19 before or during pregnancy is particularly important in settings with moderate or high risk of transmission in a particular community, and for women with an increased individual risk of infection or severe disease.

2. How does COVID-19 affect pregnant women?

Numerous studies show that pregnant women with COVID-19severe disease develops more often than in non-pregnant women. This means that pregnant women who are infected with the coronavirus are more likely to require hospitalization, intensive care, and invasive ventilation to help breathe easier. In addition, compared with healthy pregnant women, pregnant women with COVID-19 have an increased risk of preterm birth and babies requiring intensive care. They may also have an increased risk of stillbirth and maternal death.

They may also have an increased risk of stillbirth and maternal death.

Pregnant women of mature age (35 years or older), who are overweight, or who have conditions such as diabetes or hypertension may be at an even higher risk of serious adverse health outcomes.

3. Are COVID-19 vaccines effective during pregnancy?

Studies have found that COVID-19 vaccines are highly effective in preventing severe illness, hospitalizations, and deaths from COVID-19. Given experience with other vaccines during pregnancy, scientists expect all WHO-approved COVID-19 vaccines towill work equally effectively regardless of the presence or absence of pregnancy.

In addition, studies have shown that pregnant women who are vaccinated against COVID-19 develop antibodies that pass into the cord blood of babies. This suggests that children may also be protected as a result of mothers being vaccinated.

4. What is known about the safety of COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy?

Although pregnant women were not included in initial clinical trials of COVID-19 vaccines, the database of evidence of the safety of vaccination during pregnancy is constantly expanding.

In several countries where vaccination against COVID-19 is widely used during pregnancy, pregnant women are monitored closely. At the same time, they did not have any problems associated with the course of pregnancy.

Thus, as of February 2022, more than 198,000 pregnant women were under observation after vaccination in the USA. Most of them received Pfizer-BioNTech, BNT162b2 and Moderna mRNA-1273 vaccines. The study did not find any adverse outcomes associated with vaccination during pregnancy.

In the UK, as of February 2022, more than 100,000 pregnant women have been vaccinated against COVID-19. Most of them were vaccinated with mRNA vaccines; approximately 10 percent received the AstraZeneca AZD1222 vaccine. Data analysis revealed similar rates of birth outcome in both vaccinated and unvaccinated pregnant women.

All vaccines covered by WHO advance recommendations have been tested in animals. These studies did not demonstrate any harmful effects of vaccination in pregnant animals and their young.

None of the vaccines covered by the WHO interim recommendations contain the live virus that causes COVID-19. This means that vaccines are basically incapable of infecting pregnant women or their children.

5. Should women who are trying to conceive be vaccinated against COVID-19?

Yes. Pre-vaccination is an important tool to protect women and their children from COVID-19 during pregnancy. Women who are trying to get pregnant can get vaccinated against COVID-19. A growing body of data has not revealed any negative effect of vaccination on fertility or the ability to conceive. In vaccine clinical trials and in a large study of couples trying to conceive, pregnancy rates were similar for those who received COVID-19 vaccines and those who did not.

WHO does not recommend postponing or terminating pregnancy due to COVID-19 vaccination. According to experts, no pregnancy tests should be done before vaccination.

6. So, in summary, what do pregnant women and those who plan to get pregnant need to know about COVID-19 vaccinations?

Given the significant risks associated with COVID-19 during pregnancy, it is critical that pregnant women and those who are planning to become pregnant have access to WHO-approved COVID-19 vaccines as soon as possible to help protect their health and the health of their children. Current evidence suggests that if pregnant women are not already vaccinated, the benefits of vaccination against COVID-19during pregnancy outweighs any potential risks.

Current evidence suggests that if pregnant women are not already vaccinated, the benefits of vaccination against COVID-19during pregnancy outweighs any potential risks.

Pregnant women and those who plan to become pregnant should be informed in a timely manner about the risks of contracting COVID-19 during pregnancy, the benefits of vaccination, and the factors that indicate the benefits of vaccination:

• Infection with COVID-19 during pregnancy can lead to consequences: Available evidence suggests that pregnant women with COVID-19 are at increased risk of severe illness, premature birth, and likely other adverse pregnancy outcomes such as stillbirth.

• COVID-19 vaccines are extremely effective, providing strong protection against serious illness and death due to coronavirus infection. Pregnant women appear to receive the same level of protection from vaccination as non-pregnant women.

• New data on the safety of vaccination during pregnancy are encouraging: to date, animal studies, observation of pregnant women who have received vaccines, and experience with vaccines with similar components have not revealed any safety problems during pregnancy.