Lactose intolerance breastfeeding

Does breast milk contain lactose? Intolerance symptoms and tips

Lactose is a type of sugar that is present in the milk of all mammals, including humans. The lactose in human breast milk plays an important role in a baby’s development.

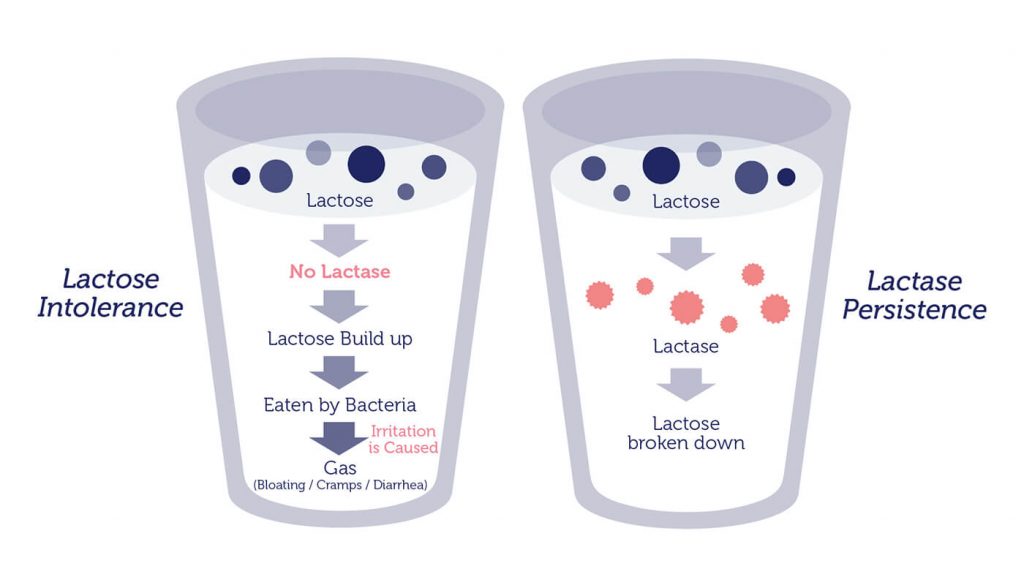

Lactose is actually a combination of two sugars. To digest lactose, the body needs to break it down into those two sugars, glucose and galactose, which are monosaccharides. The body can then absorb the sugars, allowing them to enter the bloodstream.

Both breast milk-fed and formula-fed babies can develop a condition called lactose overload. The symptoms are very similar to those of lactose intolerance, but the ways of managing the conditions are different. Proper diagnosis can help prevent potentially harmful complications.

This article reviews lactose in breast milk, what intolerance and overload look like, breastfeeding tips, and more.

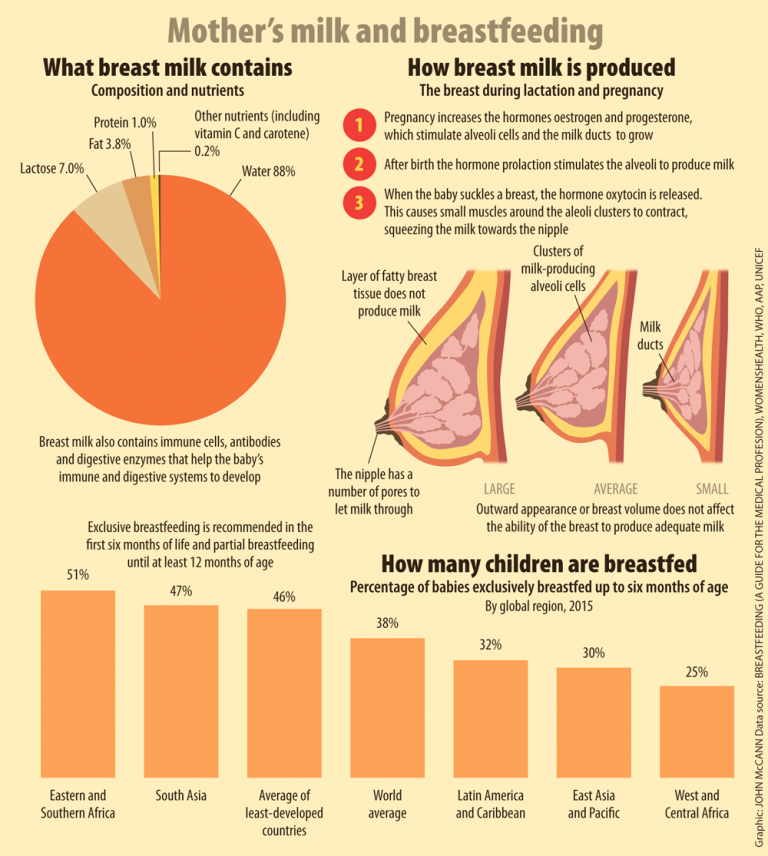

Lactose is a type of sugar that is present only in the milk of mammals, including humans. A human’s breast milk consists of about 7% lactose. This is about 7.5 grams (g) per 100 milliliters. The amount of lactose in human milk is actually higher than the roughly 5% in cow’s milk.

Lactose is not a simple sugar. Instead, it is a disaccharide. This means it is a combination of two different sugars, glucose and galactose.

To digest lactose, the body needs to break it down using an enzyme called lactase. The average full-term baby produces enough lactase to process about 1 liter of breast milk per day.

Lactose is a type of carbohydrate. Carbohydrates provide energy for infants, as well as for older children and adults.

In the first 6 months of life, an intake of about 60 g of carbohydrates per day provides babies with around 37% of their total food energy.

As babies reach 6–12 months of age, their carbohydrate needs increase to 95 g per day, which coincides with the introduction of solid foods. Babies of this age still get most of their energy from breast milk and formula, but some of it comes from the food they eat.

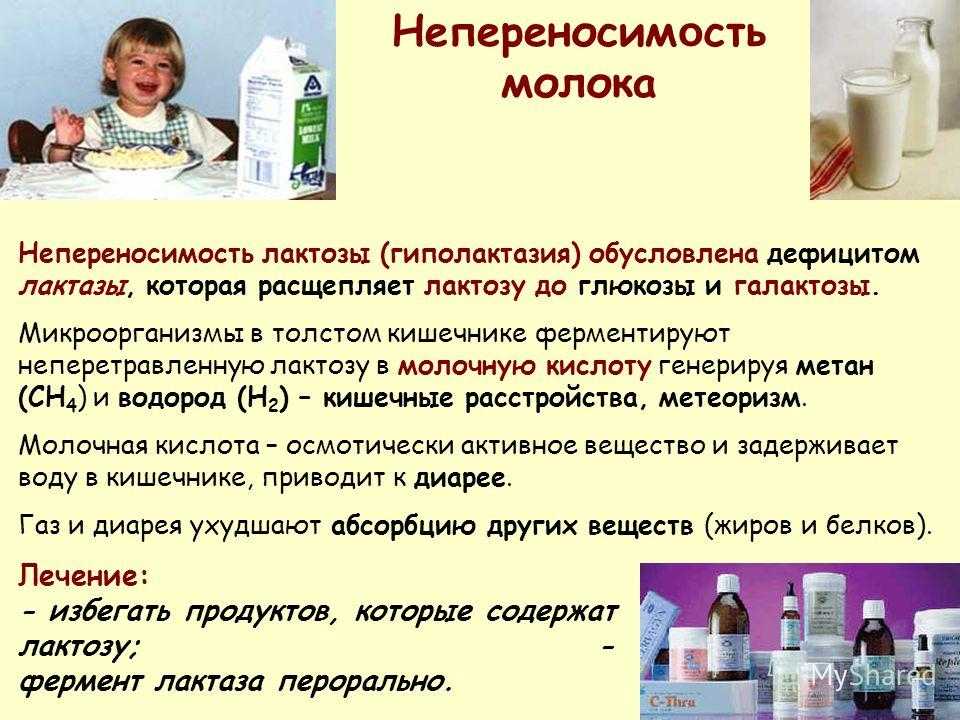

Lactose intolerance is a systemic digestive issue resulting from lactose malabsorption. A baby with lactose intolerance produces no lactase and therefore cannot break down lactose.

Very few babies are born with true lactose intolerance. Most babies can produce plenty of lactase, and their symptoms may have another explanation.

Around 1 in 30,000 babies in the United States are born with galactosemia, which is the inability to process galactose. It is a rare genetic condition that is fatal without treatment. All newborns can undergo screening for this condition.

Some babies develop a reaction to drinking breast milk, which causes flatulence and loose, explosive stool. These symptoms lead to fussiness in the baby. The symptoms resemble those of lactose intolerance, so parents, caregivers, and some doctors may believe the baby has lactose intolerance.

In some cases, a baby may experience these symptoms as a result of lactose overload.

Lactose overload causes similar symptoms to intolerance, but the cause is different. In lactose overload, the baby has no trouble processing a typical daily amount of lactose. The problem usually stems from consuming large volumes of breast milk. This may happen when a person has an oversupply of milk or when the time between feeds is long.

In lactose overload, the baby has no trouble processing a typical daily amount of lactose. The problem usually stems from consuming large volumes of breast milk. This may happen when a person has an oversupply of milk or when the time between feeds is long.

Distinguishing between these two conditions is an important part of diagnosis and can shape the treatment. Babies with an intolerance will need to switch to a lactose-free formula and avoid lactose altogether. Babies experiencing overload may need adjustments in how they eat.

According to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, most cases of lactose intolerance develop later in life. This may indicate that lactose overload is the more likely culprit for stomach discomfort in babies.

Learn more about lactose intolerance here.

Babies cannot tell their parents or caregivers what they experience, which can make it difficult to figure out what is going on. The symptoms of lactose overload and lactose intolerance are very similar.

A parent or caregiver can look for the following symptoms of lactose overload:

- difficulty settling

- a moderate to large amount of weight gain

- urination more than 10 times per day

- excessive daily bowel movements

- green, frothy, or explosive poop

- seemingly constant hunger

- gas

- diaper rash

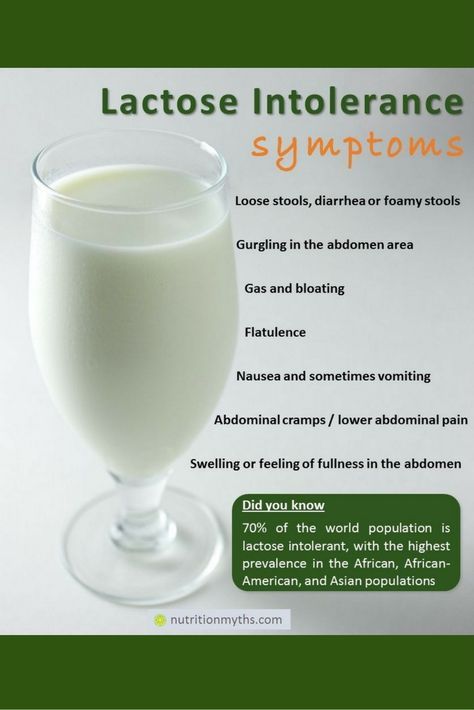

Lactose intolerance may produce the following symptoms:

- swelling in the belly

- irritability or screaming

- difficulty settling for feeds and frequently coming on and off the breast or bottle

- lack of weight gain

- diarrhea

- frothy, bulky, and watery poop

- diaper rash

- gas

- crying when passing stool

Symptoms can vary in severity from mild to severe. They may also come and go throughout the day and night.

Learn more about the color of baby poop here.

Doctors usually diagnose lactose intolerance in older children, although they may suggest avoiding breast milk or milk-based formula if a baby has symptoms. Doctors may recommend using a specialized lactose-free formula instead.

Doctors may recommend using a specialized lactose-free formula instead.

A doctor will typically look at a baby’s symptoms, family history, and diet. They will also perform a physical examination.

While lactose intolerance could explain the symptoms, a doctor may overlook lactose overload.

A baby with lactose intolerance will typically lose weight and become increasingly unwell as a result of missing key nutrients and calories from the lactose.

To help with diagnosis, a parent should discuss their nursing or formula-feeding habits with a doctor. This may help them determine whether the issue is lactose overload or intolerance.

People who breastfeed can take steps to help reduce the likelihood of lactose overload.

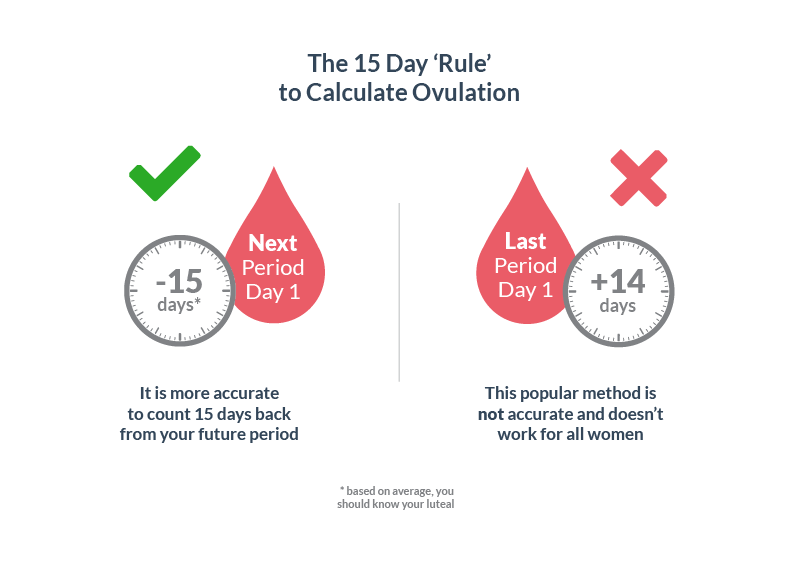

The nutritional makeup of breast milk changes as a baby feeds. Foremilk, the milk they get when they first start feeding, typically contains more sugar and less fat.

Hindmilk, the milk they get when finishing feeding from a breast, typically contains a higher amount of fat. The fat slows down the movement of milk through the digestive system, giving the body more time to absorb and process the lactose it contains.

The fat slows down the movement of milk through the digestive system, giving the body more time to absorb and process the lactose it contains.

Lactose overload can occur as a result of switching breasts too soon. In these scenarios, the baby gets mainly foremilk and limited hindmilk. This means they get primarily lactose, without the higher volumes of fat from the hindmilk.

To help prevent this imbalance, a person can try to empty one breast before switching sides. A person should check for signs that their baby is feeding well and is content. If they are, a person should delay switching sides.

If the problem continues, a person may need to try offering only one breast per feed. It may also help to reduce the time between feeds so the baby does not consume too much milk at once.

When making changes to breastfeeding patterns, caregivers should monitor the baby. Babies should produce 6–8 wet diapers per day and should gain weight steadily.

Learn more about breastfeeding here.

There is no treatment for lactose intolerance. Instead, doctors will typically recommend introducing soy-based formula and eliminating breast milk or milk-based formula from the baby’s diet.

The symptoms should start to clear once the baby stops consuming lactose.

Below are answers to some frequently asked questions about breast milk and lactose.

Is lactose intolerance the same as cow’s milk allergy?

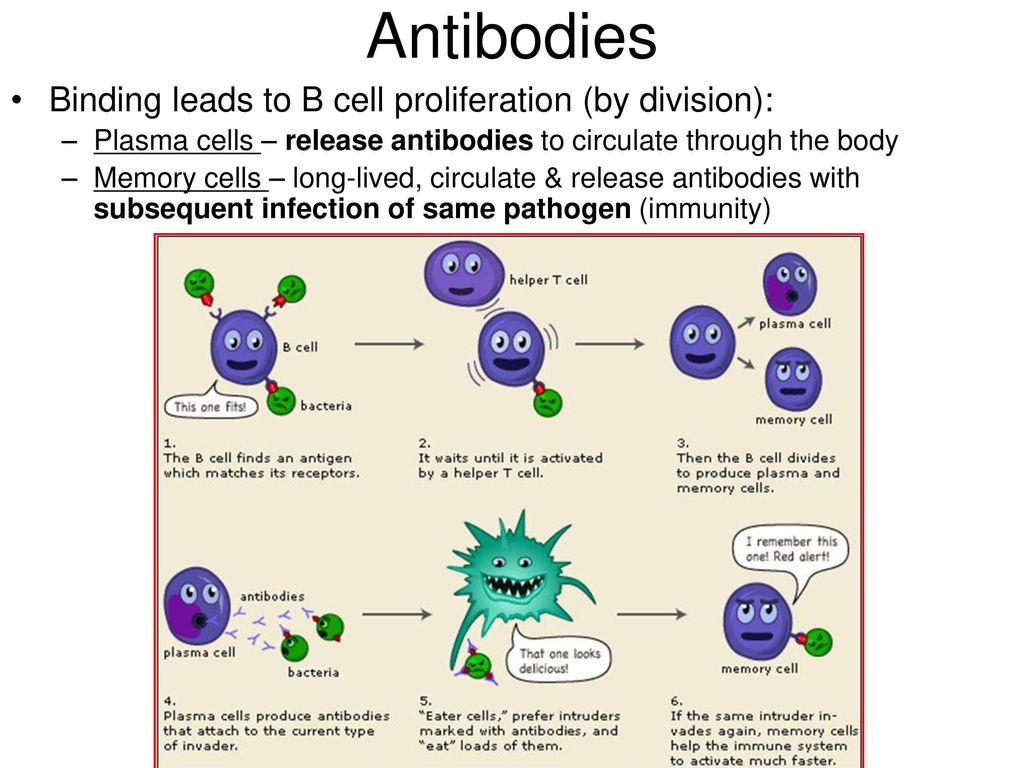

No. Lactose intolerance is an inability to process the lactose in milk. A milk allergy results from an overblown immune system response. The immune system mistakes milk protein for a foreign substance and attacks it, producing symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, hives, and eczema.

Learn more about the difference between lactose intolerance and dairy allergy.

Should I change my diet to reduce the lactose in my breast milk?

Dietary changes in a person who is breastfeeding do not affect the lactose levels of their breast milk. Eating a healthier diet, such as including more omega-3 fatty acids, may provide additional nutrients through the milk, but a person’s level of lactose will stay the same no matter what they eat.

A caregiver should contact a doctor if a baby:

- produces excessive gas or has bloating

- appears to be in discomfort much of the time

- stops eating

- does not appear to be growing or gains weight rapidly

- is vomiting, has bloody stools, and is producing fewer wet diapers

A doctor can help determine the cause of the symptoms and how to reduce them.

All milk from mammals, including humans, contains lactose. Human breast milk actually contains more lactose than cow’s milk. Full-term babies should have no issues with processing lactose.

Some babies may develop lactose overload as a result of consuming large volumes of breast milk in one feeding. Reducing the time between feedings may help the baby consume a more manageable amount of milk.

A person who is breastfeeding can let the baby empty one breast fully before starting on the other. This ensures that the baby gets the right balance of nutrients.

Although it is rare, babies may develop lactose intolerance, which means their bodies cannot process lactose effectively. Stopping breastfeeding and switching to a soy-based formula should help.

Stopping breastfeeding and switching to a soy-based formula should help.

Caregivers should consult a healthcare professional before making changes to feeding habits.

Does breast milk contain lactose? Intolerance symptoms and tips

Lactose is a type of sugar that is present in the milk of all mammals, including humans. The lactose in human breast milk plays an important role in a baby’s development.

Lactose is actually a combination of two sugars. To digest lactose, the body needs to break it down into those two sugars, glucose and galactose, which are monosaccharides. The body can then absorb the sugars, allowing them to enter the bloodstream.

Both breast milk-fed and formula-fed babies can develop a condition called lactose overload. The symptoms are very similar to those of lactose intolerance, but the ways of managing the conditions are different. Proper diagnosis can help prevent potentially harmful complications.

This article reviews lactose in breast milk, what intolerance and overload look like, breastfeeding tips, and more.

Lactose is a type of sugar that is present only in the milk of mammals, including humans. A human’s breast milk consists of about 7% lactose. This is about 7.5 grams (g) per 100 milliliters. The amount of lactose in human milk is actually higher than the roughly 5% in cow’s milk.

Lactose is not a simple sugar. Instead, it is a disaccharide. This means it is a combination of two different sugars, glucose and galactose.

To digest lactose, the body needs to break it down using an enzyme called lactase. The average full-term baby produces enough lactase to process about 1 liter of breast milk per day.

Lactose is a type of carbohydrate. Carbohydrates provide energy for infants, as well as for older children and adults.

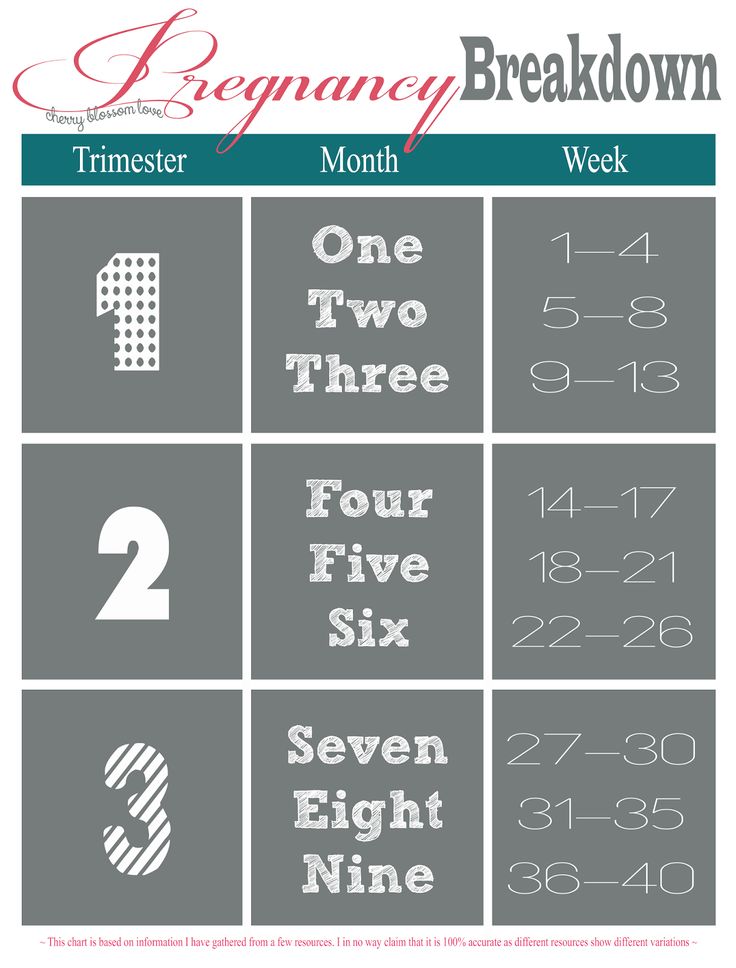

In the first 6 months of life, an intake of about 60 g of carbohydrates per day provides babies with around 37% of their total food energy.

As babies reach 6–12 months of age, their carbohydrate needs increase to 95 g per day, which coincides with the introduction of solid foods. Babies of this age still get most of their energy from breast milk and formula, but some of it comes from the food they eat.

Babies of this age still get most of their energy from breast milk and formula, but some of it comes from the food they eat.

Lactose intolerance is a systemic digestive issue resulting from lactose malabsorption. A baby with lactose intolerance produces no lactase and therefore cannot break down lactose.

Very few babies are born with true lactose intolerance. Most babies can produce plenty of lactase, and their symptoms may have another explanation.

Around 1 in 30,000 babies in the United States are born with galactosemia, which is the inability to process galactose. It is a rare genetic condition that is fatal without treatment. All newborns can undergo screening for this condition.

Some babies develop a reaction to drinking breast milk, which causes flatulence and loose, explosive stool. These symptoms lead to fussiness in the baby. The symptoms resemble those of lactose intolerance, so parents, caregivers, and some doctors may believe the baby has lactose intolerance.

In some cases, a baby may experience these symptoms as a result of lactose overload.

Lactose overload causes similar symptoms to intolerance, but the cause is different. In lactose overload, the baby has no trouble processing a typical daily amount of lactose. The problem usually stems from consuming large volumes of breast milk. This may happen when a person has an oversupply of milk or when the time between feeds is long.

Distinguishing between these two conditions is an important part of diagnosis and can shape the treatment. Babies with an intolerance will need to switch to a lactose-free formula and avoid lactose altogether. Babies experiencing overload may need adjustments in how they eat.

According to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, most cases of lactose intolerance develop later in life. This may indicate that lactose overload is the more likely culprit for stomach discomfort in babies.

Learn more about lactose intolerance here.

Babies cannot tell their parents or caregivers what they experience, which can make it difficult to figure out what is going on. The symptoms of lactose overload and lactose intolerance are very similar.

A parent or caregiver can look for the following symptoms of lactose overload:

- difficulty settling

- a moderate to large amount of weight gain

- urination more than 10 times per day

- excessive daily bowel movements

- green, frothy, or explosive poop

- seemingly constant hunger

- gas

- diaper rash

Lactose intolerance may produce the following symptoms:

- swelling in the belly

- irritability or screaming

- difficulty settling for feeds and frequently coming on and off the breast or bottle

- lack of weight gain

- diarrhea

- frothy, bulky, and watery poop

- diaper rash

- gas

- crying when passing stool

Symptoms can vary in severity from mild to severe. They may also come and go throughout the day and night.

They may also come and go throughout the day and night.

Learn more about the color of baby poop here.

Doctors usually diagnose lactose intolerance in older children, although they may suggest avoiding breast milk or milk-based formula if a baby has symptoms. Doctors may recommend using a specialized lactose-free formula instead.

A doctor will typically look at a baby’s symptoms, family history, and diet. They will also perform a physical examination.

While lactose intolerance could explain the symptoms, a doctor may overlook lactose overload.

A baby with lactose intolerance will typically lose weight and become increasingly unwell as a result of missing key nutrients and calories from the lactose.

To help with diagnosis, a parent should discuss their nursing or formula-feeding habits with a doctor. This may help them determine whether the issue is lactose overload or intolerance.

People who breastfeed can take steps to help reduce the likelihood of lactose overload.

The nutritional makeup of breast milk changes as a baby feeds. Foremilk, the milk they get when they first start feeding, typically contains more sugar and less fat.

Hindmilk, the milk they get when finishing feeding from a breast, typically contains a higher amount of fat. The fat slows down the movement of milk through the digestive system, giving the body more time to absorb and process the lactose it contains.

Lactose overload can occur as a result of switching breasts too soon. In these scenarios, the baby gets mainly foremilk and limited hindmilk. This means they get primarily lactose, without the higher volumes of fat from the hindmilk.

To help prevent this imbalance, a person can try to empty one breast before switching sides. A person should check for signs that their baby is feeding well and is content. If they are, a person should delay switching sides.

If the problem continues, a person may need to try offering only one breast per feed. It may also help to reduce the time between feeds so the baby does not consume too much milk at once.

When making changes to breastfeeding patterns, caregivers should monitor the baby. Babies should produce 6–8 wet diapers per day and should gain weight steadily.

Learn more about breastfeeding here.

There is no treatment for lactose intolerance. Instead, doctors will typically recommend introducing soy-based formula and eliminating breast milk or milk-based formula from the baby’s diet.

The symptoms should start to clear once the baby stops consuming lactose.

Below are answers to some frequently asked questions about breast milk and lactose.

Is lactose intolerance the same as cow’s milk allergy?

No. Lactose intolerance is an inability to process the lactose in milk. A milk allergy results from an overblown immune system response. The immune system mistakes milk protein for a foreign substance and attacks it, producing symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, hives, and eczema.

Learn more about the difference between lactose intolerance and dairy allergy.

Should I change my diet to reduce the lactose in my breast milk?

Dietary changes in a person who is breastfeeding do not affect the lactose levels of their breast milk. Eating a healthier diet, such as including more omega-3 fatty acids, may provide additional nutrients through the milk, but a person’s level of lactose will stay the same no matter what they eat.

A caregiver should contact a doctor if a baby:

- produces excessive gas or has bloating

- appears to be in discomfort much of the time

- stops eating

- does not appear to be growing or gains weight rapidly

- is vomiting, has bloody stools, and is producing fewer wet diapers

A doctor can help determine the cause of the symptoms and how to reduce them.

All milk from mammals, including humans, contains lactose. Human breast milk actually contains more lactose than cow’s milk. Full-term babies should have no issues with processing lactose.

Some babies may develop lactose overload as a result of consuming large volumes of breast milk in one feeding. Reducing the time between feedings may help the baby consume a more manageable amount of milk.

Reducing the time between feedings may help the baby consume a more manageable amount of milk.

A person who is breastfeeding can let the baby empty one breast fully before starting on the other. This ensures that the baby gets the right balance of nutrients.

Although it is rare, babies may develop lactose intolerance, which means their bodies cannot process lactose effectively. Stopping breastfeeding and switching to a soy-based formula should help.

Caregivers should consult a healthcare professional before making changes to feeding habits.

Lactose insufficiency - articles from the specialists of the clinic "Mother and Child"

what it is

The main food of babies is milk (breast or formula). It contains many different nutrients (proteins, fats, carbohydrates), which, with the help of special digestive enzymes, are broken down into simple components and digested. But in young children, the gastrointestinal tract is still immature, there are few enzymes in it, others are not at all or they are not yet working at full capacity. When the baby grows up, there will be more enzymes, the digestive system will mature, but for now there may be various problems with it.

When the baby grows up, there will be more enzymes, the digestive system will mature, but for now there may be various problems with it.

All milk (women's, cow's, goat's, artificial mixtures) and dairy products contain the carbohydrate lactose, also called "milk sugar". In order for lactose to be absorbed, the lactase enzyme must break it down, but if the child has little or no lactase enzyme, then lactose is not broken down and remains in the intestine. As a result, there is always a large amount of milk sugar in the intestines, which begins to ferment, and where there is fermentation, conditionally pathogenic flora actively reproduces. What we feel during fermentation: intestinal motility increases (it rumbles), plus gas formation increases (the stomach swells). But in an adult, this is usually a one-time situation due to some inaccuracies in nutrition, and it quickly passes. But in babies, everything is different, especially since they lack the enzyme not once, but constantly. What it looks like: The milk sugar lactose retains water, hence loose stools. In the child’s stomach, “rumbles and boils”, colic begins, the stool becomes frothy, greens, mucus and even blood may appear in it. If at first the stool was liquid, then constipation appears, and all this changes in a circle: yesterday there was diarrhea, today and tomorrow there is no stool at all, the day after tomorrow it is liquid again. And the most unpleasant thing is endless colic and endless crying, there is no rest for both the parents themselves and the baby. Mom at some point notices that the baby is crying just after feeding, and then a variety of advice falls upon her. “Your milk is bad, better give the mixture,” says the beloved mother-in-law. “Only breasts and nothing else!” - advise breastfeeding gurus. As a result, the mother tries one thing or the other, but neither breast milk nor artificial mixture gives relief to the child. Colic, crying and problems with the stomach and stool continue. The parents are in a panic because they don't understand what is going on.

In fact, this is a typical picture of bright lactase deficiency (LN), or insufficient production of the lactase enzyme.

In fact, this is a typical picture of bright lactase deficiency (LN), or insufficient production of the lactase enzyme.

various reasons

There are several types of lactase deficiency, and it is with them that confusion arises.

Congenital lactase deficiency is a genetic and very rare disease (one case in several thousand newborns), it is difficult to confuse it with something, since it is very difficult. The diagnosis is made in the maternity hospital or in the first days after birth, the child does not have lactase at all, he quickly loses weight, he is immediately started to be fed intravenously or through a tube. Some experts (but not doctors) on breastfeeding read once that congenital lactase deficiency is an extremely rare disease, and that’s all - they further began to assure young mothers: “In fact, LN is extremely rare, you don’t have it, you don’t need to listen to doctors ", etc. Yes, congenital LN is a rare disease, but the key word here is "congenital", and there are other types of lactase deficiency.

Transient lactase deficiency in infants . And this is exactly the condition that occurs very often. The baby was born, and so far he still has little lactase enzyme, plus little normal intestinal microflora. Hence the colic, and loose stools, and mucus, and greenery, and crying, and the nerves of the parents. After a while, the child's digestive system will fully mature, all enzymes will begin to work actively, the intestines will be populated with what is needed, and "lactase deficiency" will disappear. Therefore, such a LN is called "transient", that is, temporary, or passing. It passes for someone a month after birth, for someone longer - after six to seven months, and there are children in whom lactase deficiency completely disappears only by the year.

Secondary lactase deficiency. This condition appears if a person has had some kind of intestinal infection, and it does not matter whether it is an adult or a baby. For some time after the illness, the child does not tolerate milk (any), and then with proper nutrition and sometimes even without treatment, everything quickly passes.

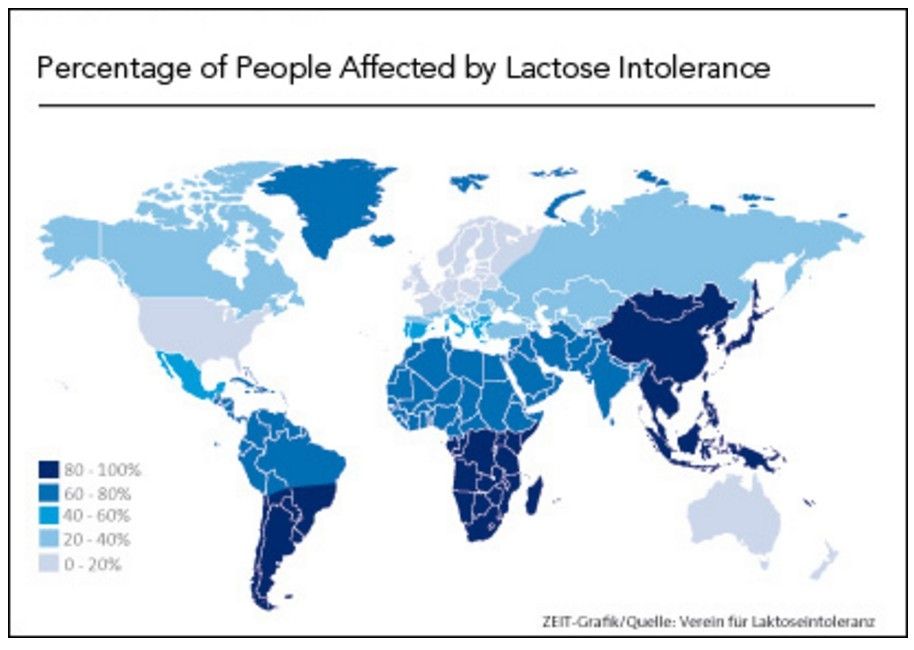

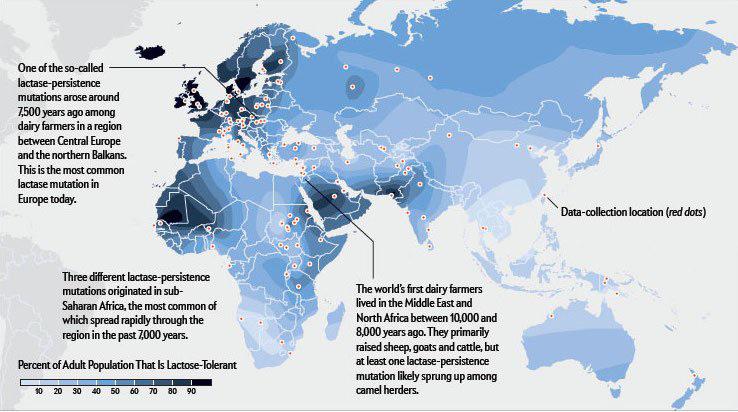

Lactase deficiency in adults. There are people in whom the lactase enzyme begins to be lacking only in adulthood, this happens for various reasons: for some, lactase ceases to be produced in the right amount after some kind of illness, for other people, the activity of this enzyme simply fades over time by itself. yourself. As a result, at some age, a person begins to tolerate milk and dairy products poorly, although before that everything was fine. The symptoms are the same as in babies: he drank milk and after that the stomach rumbles, boils, and the stool is liquid. Sooner or later, a person realizes that milk is not his product, and simply stops drinking it in its pure form.

what to do

If there is transient lactase deficiency, then what to do with it? First you need to understand if it exists at all. Why does the child have problems with the stomach, stool, why does he cry all the time? Is it neurology, common colic, errors in the mother's diet, an inappropriate mixture (if the baby is bottle-fed), improper breastfeeding technique, lactase deficiency, or a reaction to the weather? It can be difficult to figure it out right away, but if the tests show that there is lactase deficiency, then it is most likely in it. Now what to do next - treat it, wait for the enzymes to mature, or something else? Firstly, everything here will depend on how much the enzyme is lacking and, therefore, on how much LN worries the child and parents. Some children lack the enzyme quite a bit, so their colic is mild and children cry quite normally. Plus, the violation of the stool is also not very bright: there are a couple of times a slightly liquefied stool, but that's all. In other children, the lack of lactase is more pronounced, the child does not cry, but simply yells after each feeding, if at first he gained weight well, then after two months the increase is minimal, problems with stools begin in parallel (day - constipation, day - diarrhea), stool sometimes green, sometimes with mucus. Atopic dermatitis appears on the skin (the skin is the first to react to problems with the gastrointestinal tract). Parents have no rest day or night: the baby cries - he is fed - he cries again, they try to calm him down in other ways.

Now what to do next - treat it, wait for the enzymes to mature, or something else? Firstly, everything here will depend on how much the enzyme is lacking and, therefore, on how much LN worries the child and parents. Some children lack the enzyme quite a bit, so their colic is mild and children cry quite normally. Plus, the violation of the stool is also not very bright: there are a couple of times a slightly liquefied stool, but that's all. In other children, the lack of lactase is more pronounced, the child does not cry, but simply yells after each feeding, if at first he gained weight well, then after two months the increase is minimal, problems with stools begin in parallel (day - constipation, day - diarrhea), stool sometimes green, sometimes with mucus. Atopic dermatitis appears on the skin (the skin is the first to react to problems with the gastrointestinal tract). Parents have no rest day or night: the baby cries - he is fed - he cries again, they try to calm him down in other ways. But nothing helps. Mom and dad are in a panic, and no one has the strength anymore.

But nothing helps. Mom and dad are in a panic, and no one has the strength anymore.

If parents see that the child may have signs of lactase deficiency, that he needs help, first of all, you need to look for a good doctor. Only an experienced pediatrician will be able to figure out why the baby has colic or green stools, what the numbers in the tests say, and what is the norm for one baby and the pathology for another. And of course, it is not necessary to cancel breastfeeding and immediately prescribe lactose-free or low-lactose artificial mixtures (even as a supplement). By itself, milk sugar lactose is very necessary for a child, when lactose is broken down, its components (glucose and galactose) go to the development of the brain, retina, for the life of normal intestinal microflora. So do not completely eliminate this sugar, you need to help it break down. With a strongly pronounced LN, the missing enzyme is given before each feeding (it has long been learned to produce and it is sold in pharmacies), with a dim clinic, its dose can be reduced. And it is also possible that there is lactase deficiency (even according to tests), but it does not need to be treated, there are almost no symptoms.

And it is also possible that there is lactase deficiency (even according to tests), but it does not need to be treated, there are almost no symptoms.

But what cannot be done is to listen to non-specialists who deny either lactase deficiency itself or its treatment. They see the cause of all problems with the child's stomach and stool either in the wrong technique of breastfeeding, or partially admit that there is immaturity of the enzyme, but this is natural and will pass by itself. Yes, for some, LN is expressed easily and will pass quickly, but what about those parents whose child yells day and night, covered with a crust from atopic dermatitis and stopped gaining weight? Wait for the time to come and the enzymes to mature? Alas, with pronounced lactase deficiency (even if transient), enterocytes (intestinal cells) often suffer, so it is simply necessary to help such a child.

If you see that your baby has signs of lactase deficiency, look for a doctor who is committed to maintaining breastfeeding and has extensive experience. He will definitely help to find out why the baby is crying, why he has a stomach ache or has problems with stool. And then the life of the parents and the child will return to normal.

He will definitely help to find out why the baby is crying, why he has a stomach ache or has problems with stool. And then the life of the parents and the child will return to normal.

"Transient" (temporary) lactase deficiency in someone passes a month after birth, in someone longer - after six to seven months, and there are children in whom lactase deficiency completely disappears only by the age of one

If the tests show that there is a lactase deficiency, then the matter is most likely in it.

Milk sugar lactose is very necessary for a child: when lactose is broken down, its components (glucose and galactose) go to the development of the brain, retina, for the life of normal intestinal microflora

Parent's note

1. In infants, transient (temporary) lactase deficiency is most common.

2. Symptoms of lactase deficiency usually appear some time after birth. These are colic, frequent crying, increased gas formation, stool - either constipation or diarrhea (over time it becomes frothy, greens, mucus and even blood may appear in it).

3. The simplest study that can reveal lactase deficiency is the analysis of feces for carbohydrates.

4. It is usually not necessary to cancel breastfeeding or partially replace it with lactose-free or low-lactose formulas. You can give the missing enzyme from the outside.

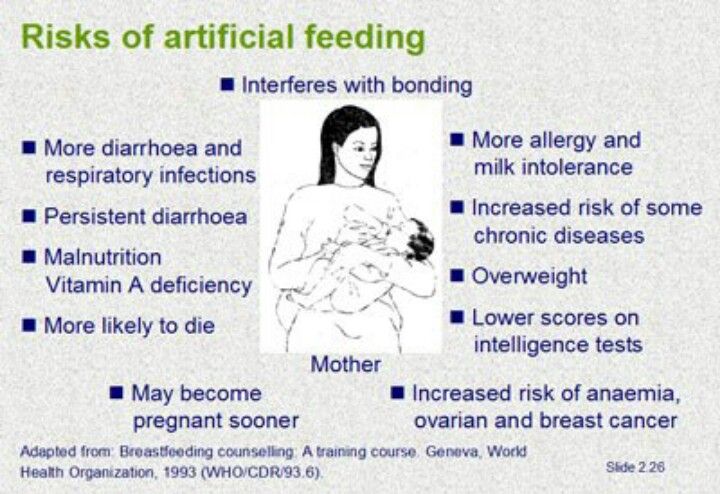

Breastfeeding and Lactose Intolerance

Infant formula companies like to use this label to their advantage, such as in ads for Similac Sensitive®: For restless behavior and gas caused by lactose intolerance. Many children sometimes act up and suffer from colic. But if it seems to you that whims and bloating have become more frequent, this may be a sign that the baby needs a different milk formula. You can trust Similac Sensitive to start effective development of your children's digestive systems."

In fact, you can't trust the advice of infant formula companies about breastfeeding, as it's in their best interest to have a mother replace her breast milk with artificial formula. Would you go to a tobacco company for advice on how to quit smoking? Probably not.

Would you go to a tobacco company for advice on how to quit smoking? Probably not.

Many newborn babies spit up and suffer from colic because their digestive system is still immature, it has just begun the transition from intrauterine nutrition (where it received nutrients through the placenta) to self-digestion of milk.

Starting with a small amount of colostrum, it is easier for a newborn's digestive system to accept more breast milk later on. After the milk has “come”, the next step in the nursing mother is transitional milk (a mixture of colostrum and milk), and a little later mature milk, about 7-10 days after the birth of the baby.

Although breast milk is much easier to digest than formula milk, occasional regurgitation, restless behavior and gas are to be expected in all newborns, whether breastfed or formula fed. Many mothers worry about their babies having frequent watery stools, but this is normal for exclusively breastfed babies.

In addition to an immature digestive system, regurgitation and gas, and even belching, can also be caused by supplements such as fluoride or iron, or gastrointestinal illnesses (eg, stomach flu).

Mothers of babies suffering from gas go to the doctor with questions about how to avoid bloating or spitting up, and in most cases doctors cannot give an answer. Doctors simply hate these kinds of questions, because for most of them they cannot give an exact answer: what caused it and how to treat it. Unhappy baby - unhappy parents, especially if they see that they can do nothing to improve his well-being.

Over time, most children's digestive system matures and they outgrow the symptoms - some earlier, some later, but most by 3-4 months. Of course, when your child is ill or in pain, even a couple of minutes seem like an eternity.

What you need to know about breastfeeding and lactose intolerance:

Lactose is a sugar found in all dairy products, including breast milk and formula.

Lactose intolerance is caused by a lack of the enzyme lactase, which breaks down lactose (milk sugar) for easier digestion in the intestines.

All babies are already born with lactose in their intestines. As they grow and are weaned, the amount of the lactase enzyme decreases. This is why sometimes lactose intolerance can show up before the age of 3-4 years, because around this age weaning is natural.

As they grow and are weaned, the amount of the lactase enzyme decreases. This is why sometimes lactose intolerance can show up before the age of 3-4 years, because around this age weaning is natural.

"Primary lactose intolerance" is the inability to digest the lactose found in all dairy products, including both breast milk and formula. This deviation is very rare and is congenital. It is estimated that only 1 in 85,000 children is born with galactosemia. Children with this genetic disorder can become overweight, dehydrated, and unhealthy from the start. They need to be fed a dairy-free formula in order to develop normally.

There is another, much more common type of lactose intolerance called Secondary Lactose Intolerance. Gastrointestinal diseases such as stomach flu (more common among formula fed babies) can cause diarrhea that irritates the stomach lining. This inflammation can cause a temporary decrease in lactase production.

This type of temporary lactose intolerance continues until the child's stomach lining recovers.

No matter what a breastfeeding mother eats or drinks, her breast milk will contain the same amount of lactose.

Most exclusively breastfed infants regulate their milk intake and do not overeat, but they can become lactose overloaded due to excess milk in the mother. The problem is not the lactose in milk itself - the fact is that the baby eats more milk (and therefore more lactose) than his digestive system can process. This can lead to an imbalance of "front" and "hind" milk.

Lactose intolerance is a term widely used to encourage breastfeeding mothers to switch to formula, but in reality, very few are lactose intolerant.

When you are told that your baby is "lactose intolerant", think twice before switching to formula. Formula milk companies are very quick to play on the mother's fears by convincing them that their products are healthier for the baby. Remember, it's in their best interest to discourage breastfeeding and promote their products.

I recently saw a very expensive can of formula in a grocery store.