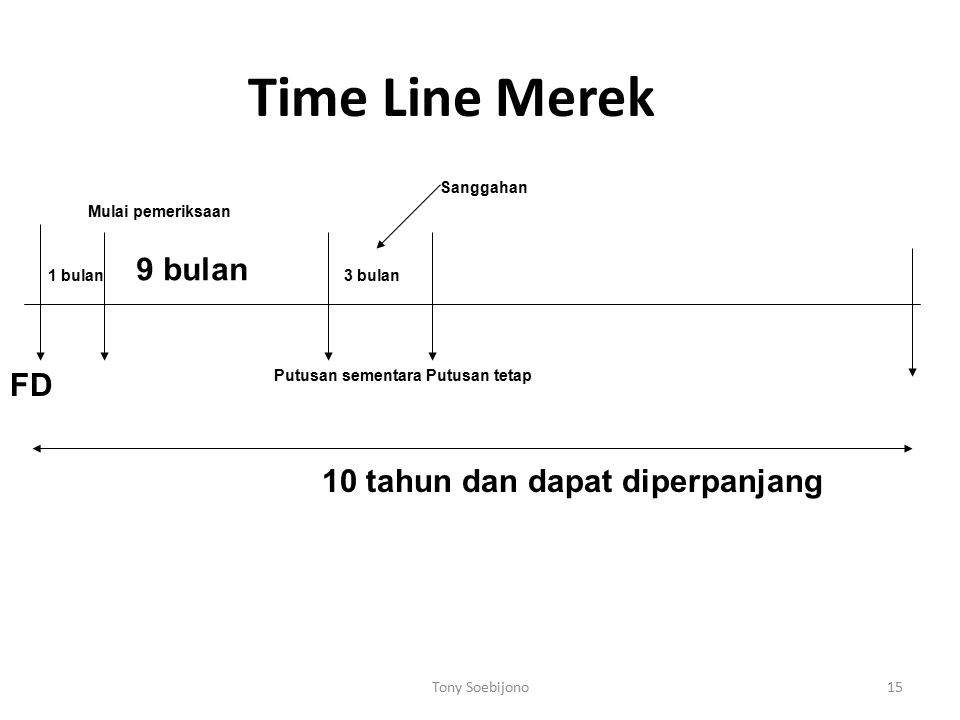

Labor induction timeline

Induced labour | Pregnancy Birth and Baby

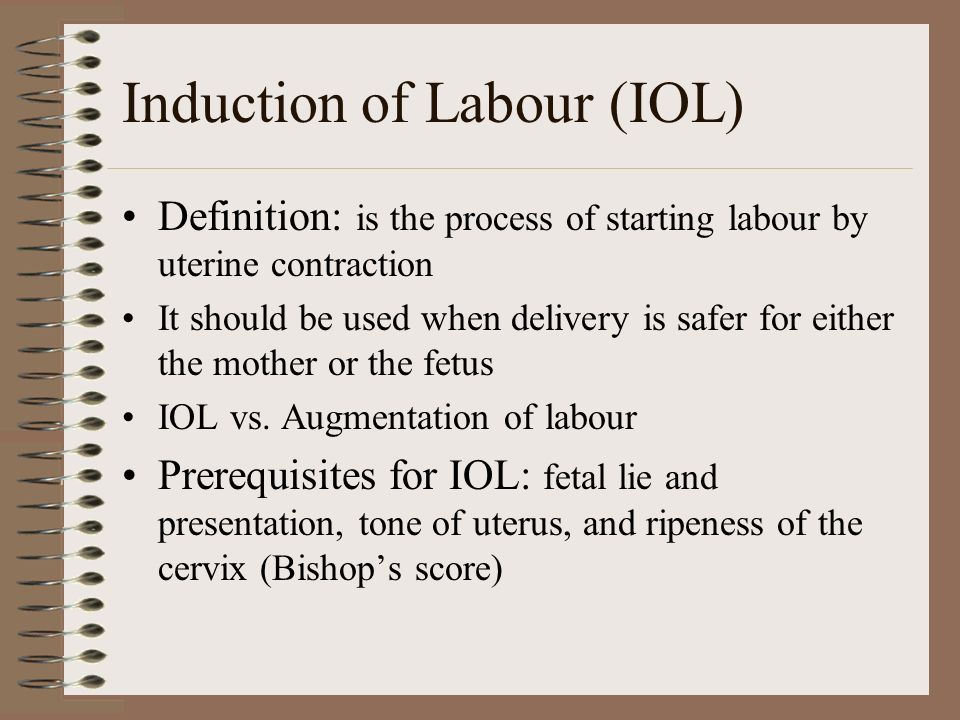

What is an induced labour?

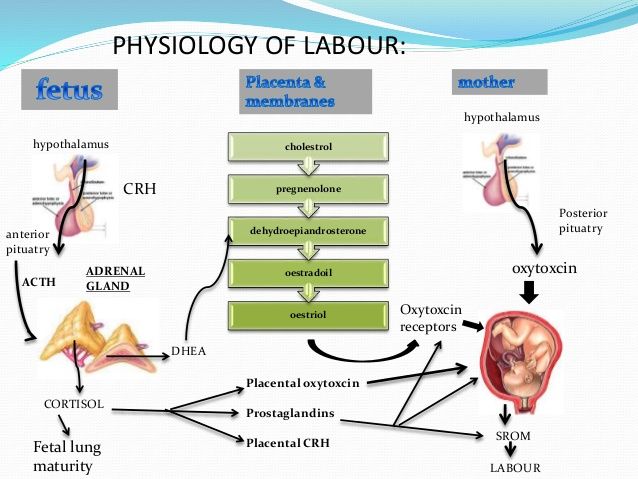

Labour normally starts naturally any time between 37 and 42 weeks of pregnancy. The cervix softens and starts to open, you will get contractions, and your waters break.

In an induced labour, or induction, these labour processes are started artificially. It might involve mechanically opening your cervix, breaking your waters, or using medicine to start off your contractions — or a combination of these methods.

In Australia, about 1 in 3 women has an induced labour.

What are the differences between an induced and a natural labour?

An induced labour can be more painful than a natural labour. In natural labour, the contractions build up slowly, but in induced labour they can start more quickly and be stronger. Because the labour can be more painful, you are more likely to want some type of pain relief.

If your labour is induced, you are also more likely to need other interventions, such as the use of forceps or ventouse (vacuum) to assist with the birth of your baby. You will not be able to move around as much because the baby will be monitored more closely than during a natural labour.

You will only be offered induced labour if there is a risk to you or your baby's health. Your doctor might recommend induced labour if:

- you are overdue (more than 41 weeks pregnant)

- there is a concern the placenta is not working as it should

- you have a health condition, such as diabetes, kidney problems, high blood pressure or pre-eclampsia

- the baby is making fewer movements, showing changes in its heart rate, or not growing well

- your waters have broken, but the contractions have not started naturally

- you are giving birth to more than one baby (twins or multiple birth)

Not everyone can have an induced labour. It is not usually an option if you have had a caesarean section or major abdominal surgery before, if you have placenta praevia, or if your baby is breech or lying sideways.

Can I decide whether to have an induced labour?

If you are overdue, you might decide to wait and see if labour will start naturally. However, if there is a chance you or your baby are at risk of complications, you might need to consider induced labour before your due date.

However, if there is a chance you or your baby are at risk of complications, you might need to consider induced labour before your due date.

When making your decision, discuss the risks and benefits with your doctor. Do not be afraid to ask lots of questions, such as:

- Why do I need an induction?

- How will it affect me and my baby?

- What will happen if I do not have the induction?

- What procedures are involved and how will you care for me and my baby?

You might need to consider several other health concerns. For example, there is a higher risk of stillbirth or other problems if your baby is not born before 42 weeks, and an increased risk of infection if your waters break more than 24 hours before labour starts.

What can I expect with an induced labour?

During the late stages of your pregnancy, your healthcare team will carry out regular checks on your health and your baby's heath. These checks help them decide whether it is better to induce labour or to keep the baby inside. Always tell your doctor or midwife if you notice your baby is moving less than normal.

Always tell your doctor or midwife if you notice your baby is moving less than normal.

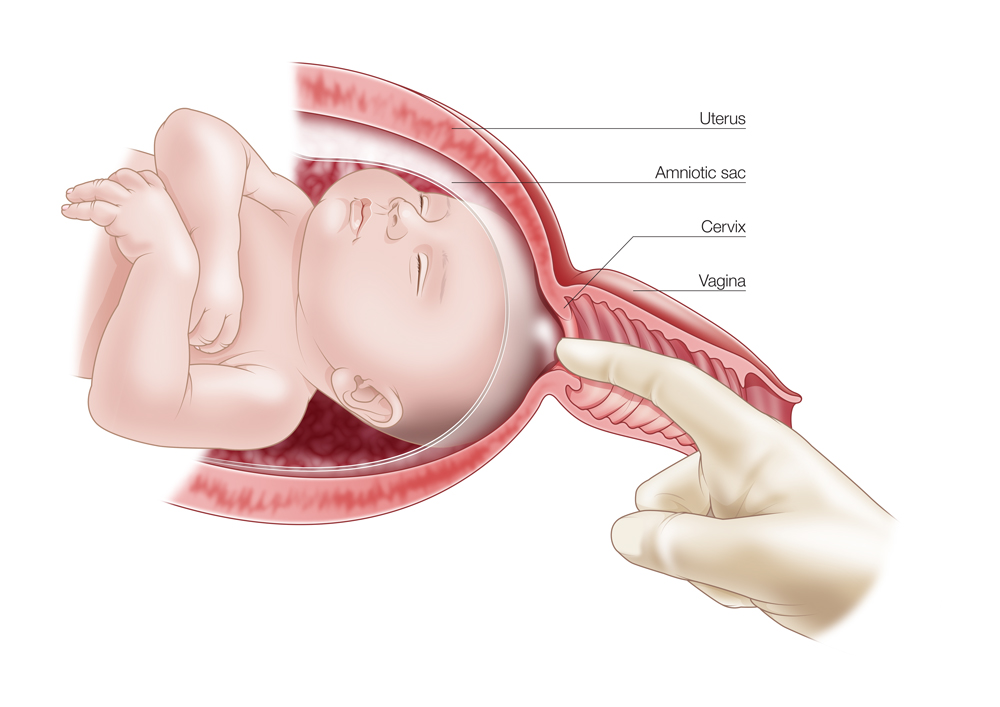

If they decide it is medically necessary to induce labour, first your doctor or midwife will do an internal examination by feeling inside your vagina. They will feel your cervix to see if it is ready for labour. This examination will also help them decide on the best method for you.

It can take from a few hours to as long as 2 to 3 days to induce labour. It depends how your body responds to the treatment. It is likely to take longer if this is your first pregnancy or you are less than 37 weeks pregnant.

What options are there to induce labour?

There are different ways to induce labour. Your doctor or midwife will recommend the best method for you when they examine your cervix. You may need a combination of different strategies. You will need to provide written consent for the procedure.

Sweeping the membranes

During a vaginal examination, the midwife or doctor makes circular movements around your cervix with their finger. This action should release a hormone called prostaglandins. You do not need to be admitted to hospital for this procedure and it is often done in the doctor's room. This can be enough to get labour started, meaning you will not need any other methods.

This action should release a hormone called prostaglandins. You do not need to be admitted to hospital for this procedure and it is often done in the doctor's room. This can be enough to get labour started, meaning you will not need any other methods.

Risks: This is a simple and easy procedure; however, it does not always work. It can be a bit uncomfortable, but it does not hurt.

Oxytocin

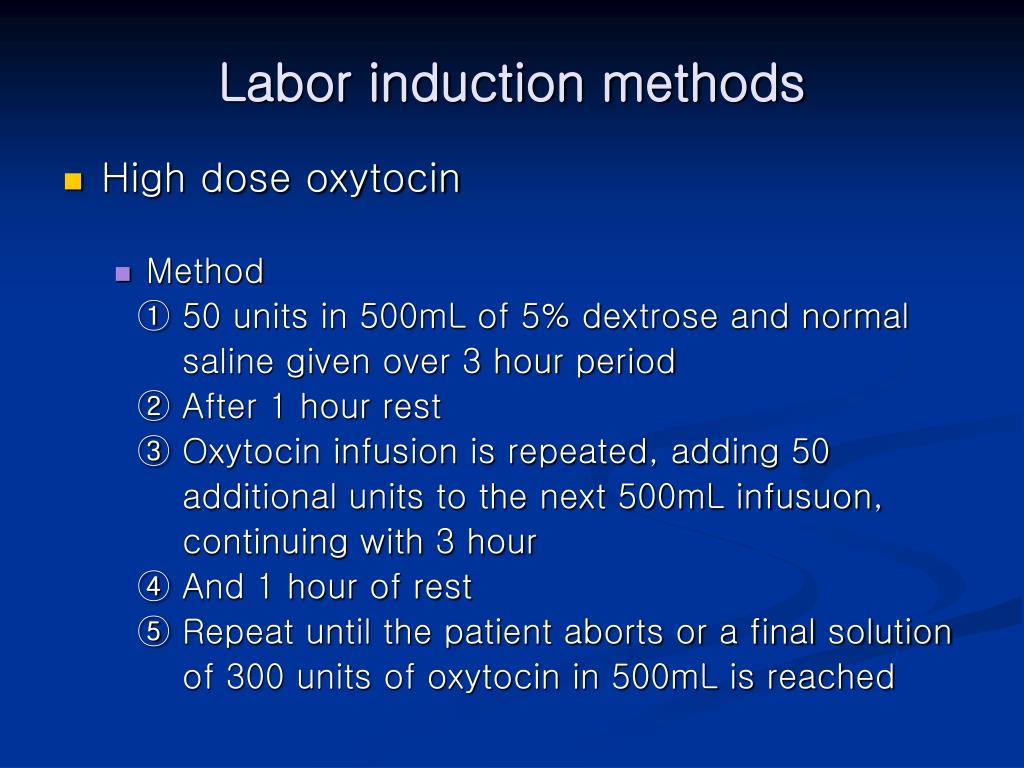

A synthetic version of the hormone oxytocin is given to you via a drip in your arm to start your contractions. When the contractions start, the amount of oxytocin is adjusted so you keep on having regular contractions until the baby is born. This whole process can take several hours.

Risks: Oxytocin can make contractions stronger, more frequent and more painful than in natural labour, so you are more likely to need pain relief. You will not be able to move around much because of the drip in your arm and you will also have a fetal monitor around your abdomen to monitor your baby.

Sometimes the contractions can come too quickly, which can affect the baby's heart rate. This can be controlled by slowing down the drip or giving you another medicine.

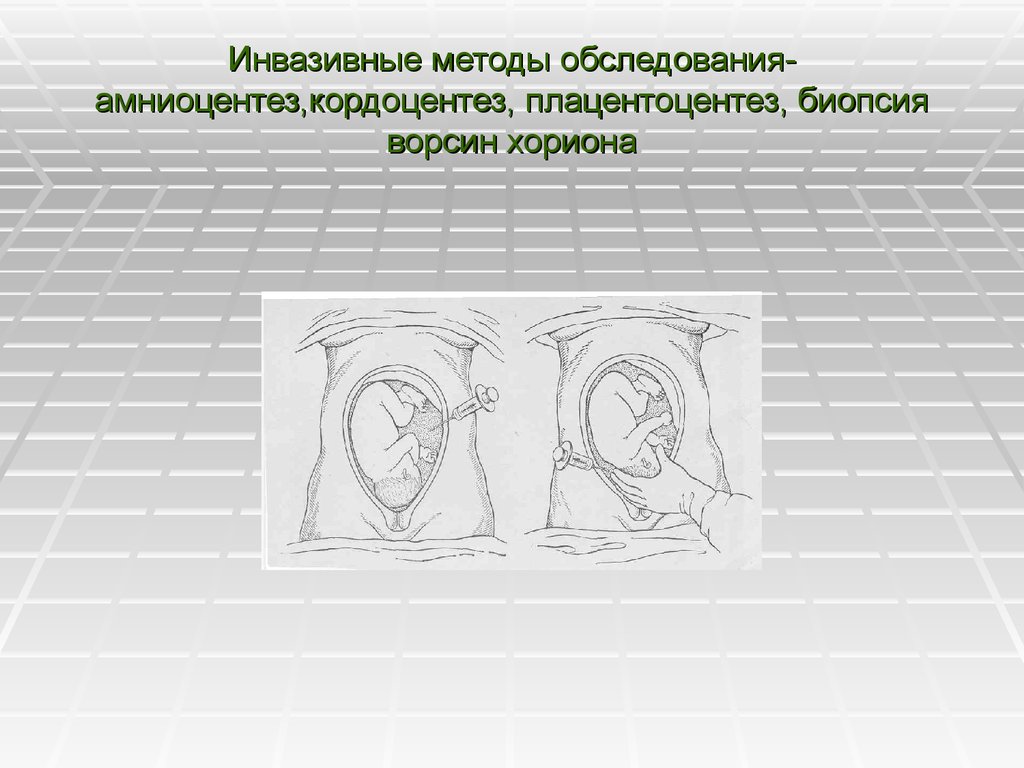

Artificial rupture of membranes ('breaking your waters')

Artificial rupture of membranes (ARM) is used when your waters do not break naturally. Your doctor or midwife inserts a small hook-like instrument through your vagina to make a hole in the membrane sac that is holding the amniotic fluid. This will increase the pressure of your baby's head on your cervix, which may be enough to get labour started. Many women will also need oxytocin to start their contractions.

Risks: ARM can be a bit uncomfortable but not painful. There is a small increased risk of a prolapsed umbilical cord, bleeding or infection.

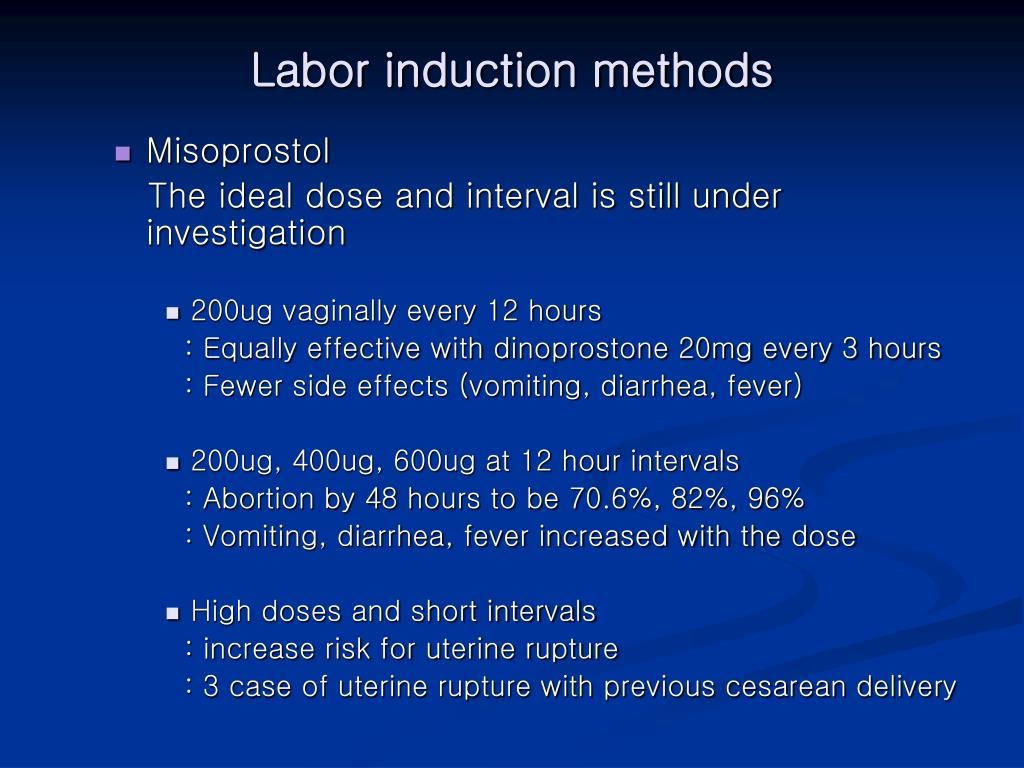

Prostaglandins

A synthetic version of the hormone prostaglandins is inserted into your vagina to soften your cervix and prepare your body for labour. It can be in the form of a gel, which may be given in several doses (usually every 6 to 8 hours), or a pessary and tape (similar to a tampon), which slowly releases the hormone over 12 to 24 hours. You will need to lie down and stay in hospital after the prostaglandins is inserted. You may also then need ARM if your waters have not broken, or oxytocin to bring on the contractions.

You will need to lie down and stay in hospital after the prostaglandins is inserted. You may also then need ARM if your waters have not broken, or oxytocin to bring on the contractions.

Prostaglandins gel is often the preferred method of inducing labour since it is the closest to natural labour. Tell your midwife or doctor straight away if you start to experience painful, regular contractions 5 minutes apart for your first baby, or 10 minutes apart for subsequent babies, or if your waters break, because these are both signs that your labour is beginning.

Risks: Some women find their vagina is sore after the prostaglandin gel, or they might experience nausea, vomiting or diarrhoea. These side effects are rare and there is no evidence that induction using prostaglandin is any more painful than a natural labour.

Very rarely, the contractions can come too strongly, which can affect the baby's heart rate. This can be controlled by giving you another medicine or removing the pessary.

You need to let your doctor or midwife know immediately if you start bleeding, or if your baby is moving less, because this could be a sign that something is wrong.

Cervical ripening balloon catheter

A cervical ripening balloon catheter is a small tube attached to a balloon that is inserted into your cervix. The balloon is inflated with saline, which usually puts enough pressure on your cervix for it to open. It stays in place for up to 15 hours, and then you will be examined again.

Tell your midwife or doctor straight away if you start to experience painful, regular contractions 5 minutes apart for your first baby, or 10 minutes apart for subsequent babies, or if your waters break, because these are both signs that your labour is beginning.

You may also need ARM or oxytocin if you are using a cervical ripening balloon catheter.

Risks: Inserting the catheter can be a bit uncomfortable but not painful.

You also need to let your doctor or midwife know immediately if you start bleeding, or your baby is moving less, because this could be a sign that something is wrong.

Can I have pain relief during induced labour?

Induced labour is usually more painful than natural labour. Depending on the type of induction you are having, this could range from discomfort with the procedure or more intense and longer lasting contractions as a result of the medication you have been given. Women who have induced labour are more likely to ask for an epidural for relief.

Because inductions are almost always done in hospital, the full range of pain relief should be available to you. There is usually no restriction on the type of pain relief you can have if your labour is induced.

Are there any risks with inducing labour?

There are some increased risks if you have an induced labour. These include that:

- it will not work — in about 1 of 4 cases, women go on to have a caesarean

- your baby will not get enough oxygen and their heart rate is affected

- you or your baby get an infection

- your uterus tears

- you bleed a lot after the birth

What happens if the induction does not work?

Not all induction methods will work for everyone. Your doctor may try another method, or you might need to have a caesarean. Your doctor will discuss all of these options with you.

Your doctor may try another method, or you might need to have a caesarean. Your doctor will discuss all of these options with you.

Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Labor induction - Mayo Clinic

Overview

Labor induction — also known as inducing labor — is prompting the uterus to contract during pregnancy before labor begins on its own for a vaginal birth.

A health care provider might recommend inducing labor for various reasons, primarily when there's concern for the mother's or baby's health. An important factor in predicting whether an induction will succeed is how soft and expanded the cervix is (cervical ripening). The gestational age of the baby as confirmed by early, regular ultrasounds also is important.

If a health care provider recommends labor induction, it's typically because the benefits outweigh the risks. If you're pregnant, understanding why and how labor induction is done can help you prepare.

Products & Services

- Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Why it's done

To determine if labor induction is necessary, a health care provider will likely evaluate several factors. These include the mother's health and the status of the cervix. They also include the baby's health, gestational age, weight, size and position in the uterus. Reasons to induce labor include:

- Nearing 1 to 2 weeks beyond the due date without labor starting (postterm pregnancy).

- When labor doesn't begin after the water breaks (prelabor rupture of membranes).

- An infection in the uterus (chorioamnionitis).

- When the baby's estimated weight is less than the 10th percentile for gestational age (fetal growth restriction).

- When there's not enough amniotic fluid surrounding the baby (oligohydramnios).

- Possibly when diabetes develops during pregnancy (gestational diabetes), or diabetes exists before pregnancy.

- Developing high blood pressure in combination with signs of damage to another organ system (preeclampsia) during pregnancy. Or having high blood pressure before pregnancy, developing it before 20 weeks of pregnancy (chronic high blood pressure) or developing the condition after 20 weeks of pregnancy (gestational hypertension).

- When the placenta peels away from the inner wall of the uterus before delivery — either partially or completely (placental abruption).

- Having certain medical conditions. These include heart, lung or kidney disease and obesity.

Elective labor induction is the starting of labor for convenience when there's no medical need. It can be useful for women who live far from the hospital or birthing center or who have a history of fast deliveries.

A scheduled induction might help avoid delivery without help. In such cases, a health care provider will confirm that the baby's gestational age is at least 39 weeks or older before induction to reduce the risk of health problems for the baby.

In such cases, a health care provider will confirm that the baby's gestational age is at least 39 weeks or older before induction to reduce the risk of health problems for the baby.

As a result of recent studies, women with low-risk pregnancies are being offered labor induction at 39 to 40 weeks. Research shows that inducing labor at this time reduces several risks, including having a stillbirth, having a large baby and developing high blood pressure as the pregnancy goes on. It's important that women and their providers share in decisions to induce labor at 39 to 40 weeks.

Request an Appointment at Mayo Clinic

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free, and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips and current health topics, like COVID-19, plus expertise on managing health.

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which

information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with

other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could

include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected

health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health

information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of

privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on

the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could

include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected

health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health

information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of

privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on

the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Risks

Uterine incisions used during C-sections

Uterine incisions used during C-sections

A C-section includes an abdominal incision and a uterine incision. After the abdominal incision, the health care provider will make an incision in the uterus. Low transverse incisions are the most common (top left).

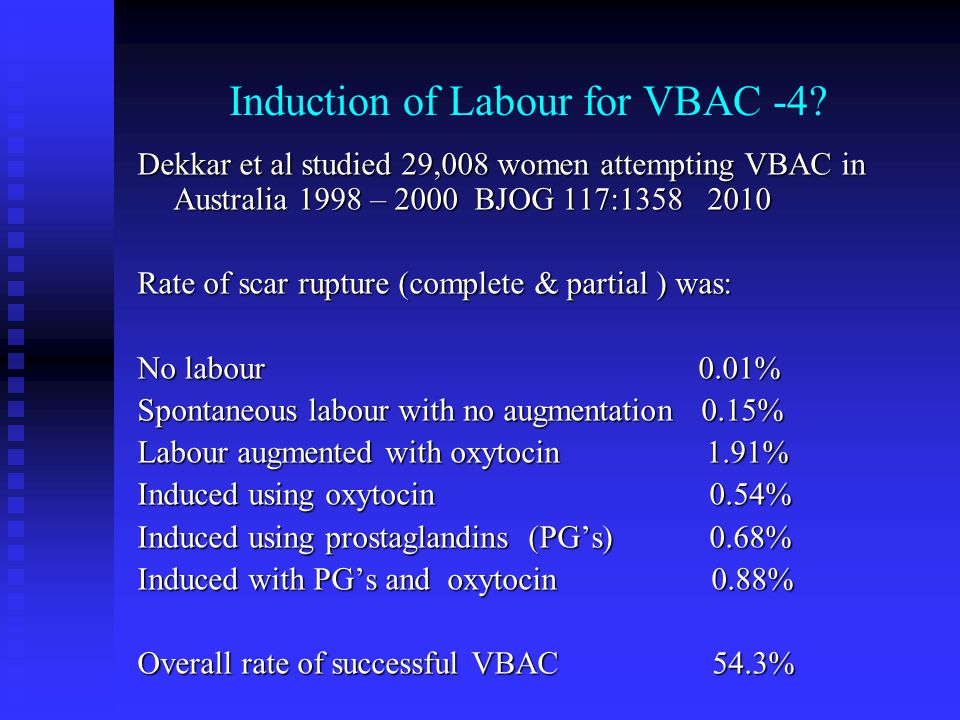

Labor induction carries various risks, including:

- Failed induction.

An induction might be considered failed if the methods used don't result in a vaginal delivery after 24 or more hours. In such cases, a C-section might be necessary.

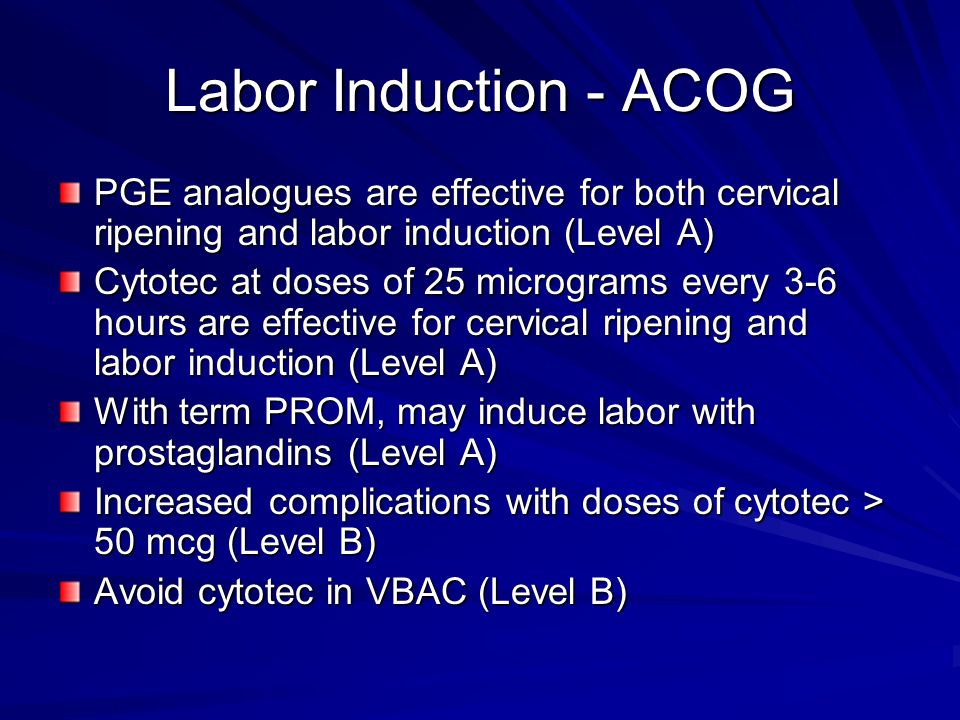

An induction might be considered failed if the methods used don't result in a vaginal delivery after 24 or more hours. In such cases, a C-section might be necessary. - Low fetal heart rate. The medications used to induce labor — oxytocin or a prostaglandin — might cause the uterus to contract too much, which can lessen the baby's oxygen supply and lower the baby's heart rate.

- Infection. Some methods of labor induction, such as rupturing the membranes, might increase the risk of infection for both mother and baby. The longer the time between membrane rupture and labor, the higher the risk of an infection.

-

Uterine rupture. This is a rare but serious complication in which the uterus tears along the scar line from a prior C-section or major uterine surgery. Rarely, uterine rupture can also occur in women who have not had previous uterine surgery.

An emergency C-section is needed to prevent life-threatening complications.

The uterus might need to be removed.

The uterus might need to be removed. - Bleeding after delivery. Labor induction increases the risk that the uterine muscles won't properly contract after giving birth, which can lead to serious bleeding after delivery.

Labor induction isn't for everyone. It might not be an option if:

- You've had a C-section with a classical incision or major uterine surgery

- The placenta is blocking the cervix (placenta previa)

- Your baby is lying buttocks first (breech) or sideways (transverse lie)

- You have an active genital herpes infection

- The umbilical cord slips into the vagina before delivery (umbilical cord prolapse)

If you have had a C-section and have labor induced, your health care provider is likely to avoid certain medications to reduce the risk of uterine rupture.

How you prepare

Labor induction is typically done in a hospital or birthing center. That's because mother and baby can be monitored there, and labor and delivery services are readily available.

What you can expect

During the procedure

There are various ways of inducing labor. Depending on the circumstances, the health care provider might use one of the following ways or a combination of them. The provider might:

-

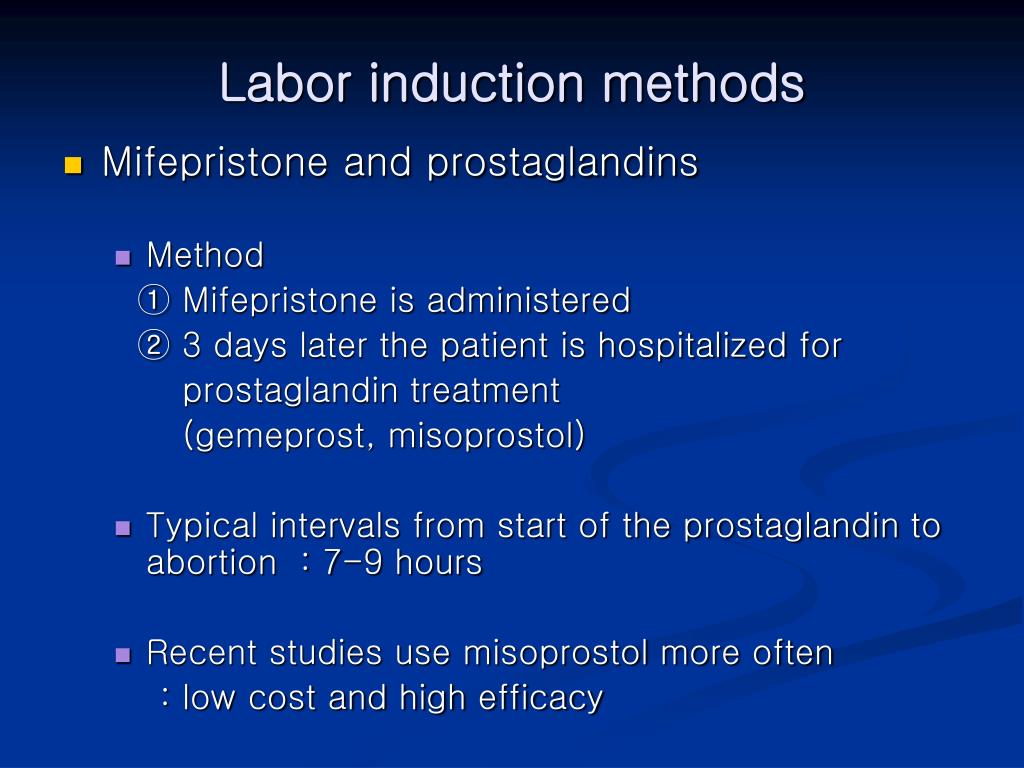

Ripen the cervix. Sometimes prostaglandins, versions of chemicals the body naturally produces, are placed inside the vagina or taken by mouth to thin or soften (ripen) the cervix. After prostaglandin use, the contractions and the baby's heart rate are monitored.

In other cases, a small tube (catheter) with an inflatable balloon on the end is inserted into the cervix. Filling the balloon with saline and resting it against the inside of the cervix helps ripen the cervix.

- Sweep the membranes of the amniotic sac. With this technique, also known as stripping the membranes, the health care provider sweeps a gloved finger over the covering of the amniotic sac near the fetus.

This separates the sac from the cervix and the lower uterine wall, which might help start labor.

This separates the sac from the cervix and the lower uterine wall, which might help start labor. -

Rupture the amniotic sac. With this technique, also known as an amniotomy, the health care provider makes a small opening in the amniotic sac. The hole causes the water to break, which might help labor go forward.

An amniotomy is done only if the cervix is partially dilated and thinned, and the baby's head is deep in the pelvis. The baby's heart rate is monitored before and after the procedure.

- Inject a medication into a vein. In the hospital, a health care provider might inject a version of oxytocin (Pitocin) — a hormone that causes the uterus to contract — into a vein. Oxytocin is more effective at speeding up labor that has already begun than it is as at cervical ripening. The provider monitors contractions and the baby's heart rate.

How long it takes for labor to start depends on how ripe the cervix is when the induction starts, the induction techniques used and how the body responds to them. It can take minutes to hours.

It can take minutes to hours.

After the procedure

In most cases, labor induction leads to a vaginal birth. A failed induction, one in which the procedure doesn't lead to a vaginal birth, might require another induction or a C-section.

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Related

Products & Services

When induction of labor in obstetrics is a modern, safe, effective and reliable strategy

Authors: ABOUT. Demchenko, Ph.D. D., Associate Professor of the Department of Perinatology, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kharkiv Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education

09.02.2019

Obstetricians around the world face the daunting task of managing the reproductive process. The desire to do no harm and follow the natural course and completion of pregnancy often has negative consequences. At the same time, excessively active tactics in relation to the management of pregnancy and delivery also sometimes have unsatisfactory outcomes for both the mother and the fetus. All this turns into conflicts of interest in real life. Against the background of a downward trend in the health index of the female population, the number of complicated pregnancies is increasing, and the maternal and perinatal risks of these complications and losses are increasing. The aggressive activity of some modern obstetricians or a pronounced conservative-waiting strategy sometimes does more harm than good. Where is the golden mean? It is important to assess and introduce into everyday practice the world's proven positive obstetric experience. This should take into account national characteristics, the interests of patients, as well as the possibilities and principles of the system of medical care for mothers and children. How relevant is it today to talk about such a problem as preinduction and induction of labor? Currently, disputes and discussions on these issues among specialists do not stop.

At the same time, excessively active tactics in relation to the management of pregnancy and delivery also sometimes have unsatisfactory outcomes for both the mother and the fetus. All this turns into conflicts of interest in real life. Against the background of a downward trend in the health index of the female population, the number of complicated pregnancies is increasing, and the maternal and perinatal risks of these complications and losses are increasing. The aggressive activity of some modern obstetricians or a pronounced conservative-waiting strategy sometimes does more harm than good. Where is the golden mean? It is important to assess and introduce into everyday practice the world's proven positive obstetric experience. This should take into account national characteristics, the interests of patients, as well as the possibilities and principles of the system of medical care for mothers and children. How relevant is it today to talk about such a problem as preinduction and induction of labor? Currently, disputes and discussions on these issues among specialists do not stop. Induction of labor is performed in women with high and low maternal and perinatal risk and aims to reduce the duration of pregnancy and reduce these risks.

Induction of labor is performed in women with high and low maternal and perinatal risk and aims to reduce the duration of pregnancy and reduce these risks.

Over the past few decades, the incidence of induction of labor has tended to increase in all countries. In developed countries, a quarter of all births at term and 20-30% at preterm pregnancy are induced. Data from the WHO Global Survey of Maternal and Perinatal Health (2014), which included the results of an analysis of almost 300,000 deliveries from 373 hospitals in 24 countries, showed that induction of labor occurs in 9.6% of cases. It was mentioned in the review that the incidence of induction of labor in hospitals in Africa is at a lower level (the lowest rate in Niger - 1.4%) than in Asia and Latin America (the highest rate of induction of labor in Sri Lanka). – 35.5%). According to the statistical centers of America and Canada, the number of programmed births in South America is 58% of the total number of births.

A number of reasons lead to the increase in the number of induced births in the world. The number of pregnant women of the older age group is increasing, there are social and medical reasons for this. There is a growing number of patients of reproductive age, whose pregnancy occurred against the background of extragenital diseases - obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertensive disorders, chronic diseases of the urinary system, endocrine disorders, infectious diseases. The course of pregnancy is often complicated by preeclampsia, placental dysfunction, intrauterine growth retardation. A certain proportion in this case is occupied by cases of multiple pregnancy. The list of indications for pre-induction and induction of labor has not yet been clearly defined, although the relative indications for their implementation are gradually expanding. Recently, the experience of elective (from English elective - optional, elective, elective, optional) induction of labor. Successes in induction of labor are finding more supporters of this strategy among obstetricians. New technologies in obstetrics provide for the active participation of patients in the reproductive process. The patient has the right to choose the time of pregnancy resolution and the date of birth of the child.

New technologies in obstetrics provide for the active participation of patients in the reproductive process. The patient has the right to choose the time of pregnancy resolution and the date of birth of the child.

Recently, various professional medical communities have recommended the use of induction of labor in cases where, in the opinion of the doctor, the risks associated with waiting for spontaneous onset of labor exceed the risks associated with shortening the duration of pregnancy due to induction.

There is no consensus on the safety and efficacy of induced labor. Various obstetric schools around the world identify and recommend their own list of indications for induction of labor (IR; table).

Today, there are new positive trends in the definition of obstetric strategy in terms of induction of labor:

- expanding maternal and fetal indications for labor induction;

- obstetricians have a differentiated approach to determining the timing of pre-induction and induction of labor, depending on the presence and degree of maternal and perinatal risks;

- timely planning of induction of labor is carried out;

- rational and consistent use of methods of pre-induction and induction of labor by obstetricians is carried out with a thorough step-by-step assessment of the effectiveness of the selected methods, obstetric aggression is minimized;

- certified mechanical means are used;

- the effectiveness of labor induction is achieved using a combination of mechanical and pharmacological (drug) means;

- , pregnant women and their families are actively informed about the benefits of planned delivery at the optimal time, the safety and effectiveness of the latest methods of preparing for childbirth are explained.

The timing of labor induction is extremely important. Recommendations regarding the timing of labor initiation are based on an assessment of the balance of maternal and perinatal risks. Induction of labor before 39 weeks 0 days of gestation without medical indication is associated with worse perinatal outcomes than labor at 40 weeks or more. For women who are 41 weeks pregnant or later, delivery is recommended due to increased perinatal risks. No form of enhanced antenatal monitoring, as noted in the 2018 Queensland Clinical Guidelines (Queensland Clinical Guidelines. Australia), reduces perinatal mortality associated with prolonged pregnancy. When pregnancy reaches 39weeks 0 days and continuing up to 40 weeks 6 days, it was common practice to avoid active delivery tactics due to lack of evidence of perinatal benefit and concerns about more frequent caesarean section and other possible adverse maternal outcomes, especially among nulliparous women. The perinatal and maternal consequences of induction of labor at 39 weeks among low-risk non-religious women have not been determined.

To test the hypothesis that selective induction of labor after 39weeks is more likely to reduce the risk of adverse perinatal outcome or the risk of severe neonatal complications than expectant management among low-risk nulliparous women, a multicenter randomized controlled trial was conducted. This study was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Development. Eunice Kennedy Shriver. A total of 6106 patients took part in the study, 3062 of them underwent induction of labor in 39weeks - 39 weeks 4 days. The comparison group consisted of 3044 pregnant women who were treated with expectant management up to 40 weeks and 5 days, but not later than 42 weeks and 2 days. In August 2018, the results of this study were published in The New England Journal of Medicine in the article Labor Indaction versus Expectant Management in Low-Risk Nulliparous Women. The conclusions were as follows: induction of labor at 39 weeks in nulliparous women at low risk did not provide a significant reduction in the incidence of adverse perinatal outcomes, but provided Significant reduction in caesarean section rate . Additionally, it turned out that women with induction of labor experienced less labor pain (had lower scores on a 10-point Likert scale) and, although they had a longer duration of hospitalization in an obstetric hospital, the duration of their postpartum stay in the maternity ward was shorter.

Additionally, it turned out that women with induction of labor experienced less labor pain (had lower scores on a 10-point Likert scale) and, although they had a longer duration of hospitalization in an obstetric hospital, the duration of their postpartum stay in the maternity ward was shorter.

It should be noted that the indications for induction of labor in most cases are not absolute. The start time for pre-induction and induction of labor and the choice of method depend on the specific clinical situation, as well as clear indications and contraindications for the use of the chosen method. Induction of labor should be carried out based on the necessary urgency to achieve the result, taking into account the availability of available resources.

The most common complications of induction of labor include: hyperstimulation or rupture of the uterus, fetal distress, prolapsed cord loops, postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony, premature detachment of a normally located placenta, infectious diseases, an increase in the number of instrumental and operative deliveries.

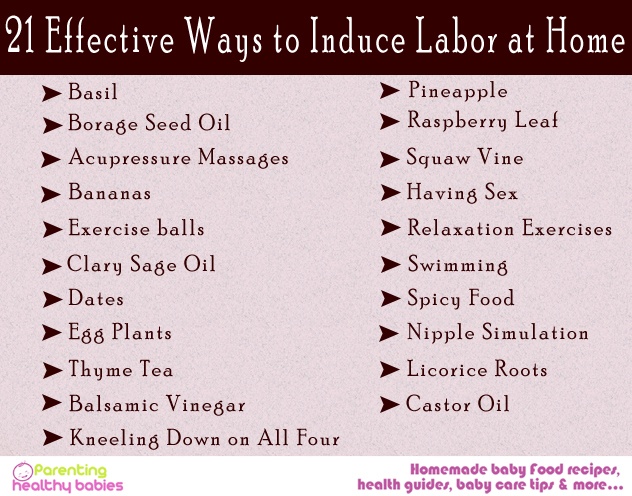

The Queensland Clinical Guideline on Induction of Labor (2018) cites that there is insufficient evidence to support IR use of nipple stimulation, acupuncture, intercourse use, kelp and evening primrose oil, castor oil, homeopathic remedies, nitric oxide donors, hyaluronidase, estrogens and corticosteroids.

To be continued.

Thematic issue "Obstetrics, Gynecology, Reproductology" No. 4 (32), chest 2018

- Number:

- Thematic issue "Gynecology, Obstetrics, Reproductology" No. 4 (32), chest 2018

08/25/2022 Obstetrics/gynecologyOncology and hematologyCervical cancer screening for early disease detection

The Public Health Center of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine invites women to undergo screening for cervical cancer (CC) due to recommendations that it is not necessary to see a gynecologist for a preventive examination. Even if you find ways to prevent illness and get cervical cancer at an early stage....

Even if you find ways to prevent illness and get cervical cancer at an early stage....

08/23/2022 Obstetrics/gynecologyOncology and hematologyScreening for cervical cancer in Ukraine0005

In Zaporizhia, the minds of the war continue to come in for screening for cervical cancer. How urgent is the problem of prevention of oncological diseases and how can the state give respect to screening?...

08/23/2022 Obstetrics/gynecologyOncology and hematologyPrevention of cervical cancer in Ukraine at the beginning of the war: strategy "90-70-90, self-screening model and test and treat tactics

Cervical cancer (CC) is the fourth widest type of malignant puffiness in women. In 2018, 570,000 new cases of cervical cancer were registered in the world, and 311,000 deaths were registered, 90% of them became in the countries with low and average income, demonstrating illness in 7-10 cases, in s...

In 2018, 570,000 new cases of cervical cancer were registered in the world, and 311,000 deaths were registered, 90% of them became in the countries with low and average income, demonstrating illness in 7-10 cases, in s...

04/25/2022 Obstetrics/gynecology European recommendations for the diagnosis of this treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis

We present your advice from the German, Austrian and Swiss Associations of Obstetrics and Gynecology on how to diagnose this type of vulvovaginal candidiasis. The publication analyzed and clarified all the super clear symptoms and gave recommendations for the management of patients with acute and chronic recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Key words: vulvovaginal candidiasis, Candida albicans, hostria vulvovaginitis. ...

...

Induction of labor in women with normal pregnancies of 37 weeks or more

Does the policy of inducing labor at 37 weeks of gestation or more reduce the risks for infants and their mothers compared with a policy of Will there be indications for labor induction?

This review was originally published in 2006 and subsequently updated in 2012 and 2018.

What is the problem?

The average pregnancy lasts 40 weeks from the start of a woman's last menstrual period. Pregnancies lasting more than 42 weeks are described as "post-term" and therefore the woman and her doctor may decide to give birth by induction. Factors associated with postnatal pregnancy and delayed delivery include obesity, first birth, and maternal age over 30 years.

Why is this important?

Prolonged (term) pregnancy may increase risks for babies, including a greater risk of death (before or shortly after birth). However, induction (stimulation or induction) of labor can also pose risks to mothers and their babies, especially if the woman's cervix is not ready for delivery. Current diagnostic methods cannot predict risks to babies or their mothers per se, and many hospitals have specific policies regarding how long a pregnancy can last.

However, induction (stimulation or induction) of labor can also pose risks to mothers and their babies, especially if the woman's cervix is not ready for delivery. Current diagnostic methods cannot predict risks to babies or their mothers per se, and many hospitals have specific policies regarding how long a pregnancy can last.

What evidence did we find?

We searched for evidence (July 17, 2019) and identified 34 randomized controlled trials in 16 different countries involving more than 21,500 women (mostly at low risk of complications). The trials compared a policy of induction of labor after 41 completed weeks of gestation (>287 days) with a policy of waiting (expectant management).

Labor induction policies were associated with fewer perinatal deaths (22 trials, 18 795 babies). Four perinatal deaths occurred in the induction policy group compared with 25 perinatal deaths in the expectant management group. Fewer stillbirths occurred in the induction group (22 trials, 18,795 infants): two in the induction group and 16 in the expectant management group.

Women in the induction of labor groups in the included studies were probably less likely to deliver by caesarean section than in the expectant management groups (31 studies, 21,030 women), and there was probably little or no difference when compared with assisted vaginal delivery (22 studies, 18,584 women).

Fewer infants were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in the induction policy group (17 trials, 17,826 infants; high-certainty evidence). A simple test of the baby's health status (Apgar score) at five minutes after birth was likely to be more favorable in the induction groups than expectant management (20 trials, 18,345 infants).

The policy of induction may make little or no difference for women who have had a perineal injury, and probably has little or no effect on the number of women with postpartum hemorrhage or breastfeeding at hospital discharge. We are uncertain about the effect of induction or expectant management on length of stay in the maternity hospital due to the very low certainty of the evidence.

Among newborns, the number of children with trauma or encephalopathy was similar in both groups (moderate and low-certainty evidence, respectively). None of the studies reported the development of neurodevelopmental problems during follow-up of children and postpartum depression in women. Only three trials reported some measure of maternal satisfaction.

What does this mean?

An induction policy compared with expectant management is associated with fewer infant deaths and probably fewer caesarean sections; and probably has little or no effect on assisted vaginal delivery. Determining the best time to offer induction of labor to women at 37 weeks' gestation or more requires further study, as well as further study of women's risk profiles and their values and preferences. Discussing the risks of induction of labor, including benefits and harms, can help women make an informed choice between induction of labor, especially if the pregnancy lasts more than 41 weeks, or expectant management—waiting and/or waiting until labor is induced.