Importance of mother infant bonding

The Importance of Infant Bonding

When a caregiver consistently responds to an infant’s needs, it sets the stage for the growing child to enter healthy relationships with other people throughout life and to appropriately experience and express a full range of emotions.

By Mary Beth Steinfeld, M.D.

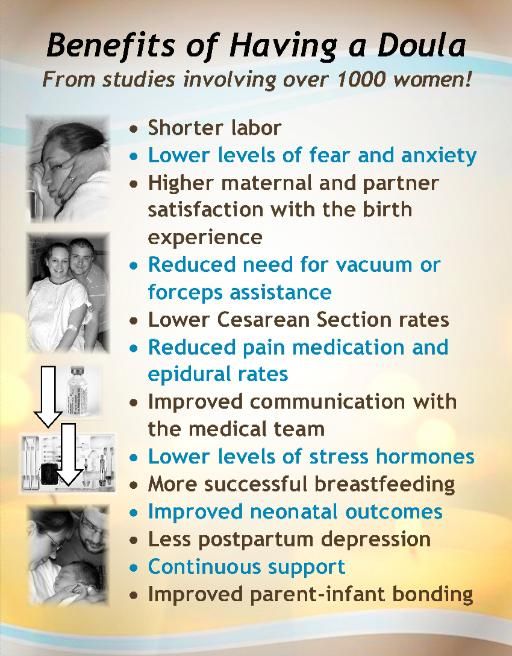

The process of bonding with a new baby is natural for most mothers. Left alone, new mothers will hold their baby next to their bodies, rock them gently, strive for eye contact, sing or talk to the baby and begin to nurse. Often within just hours of birth, mothers report feelings of overwhelming love and attachment for their new baby.

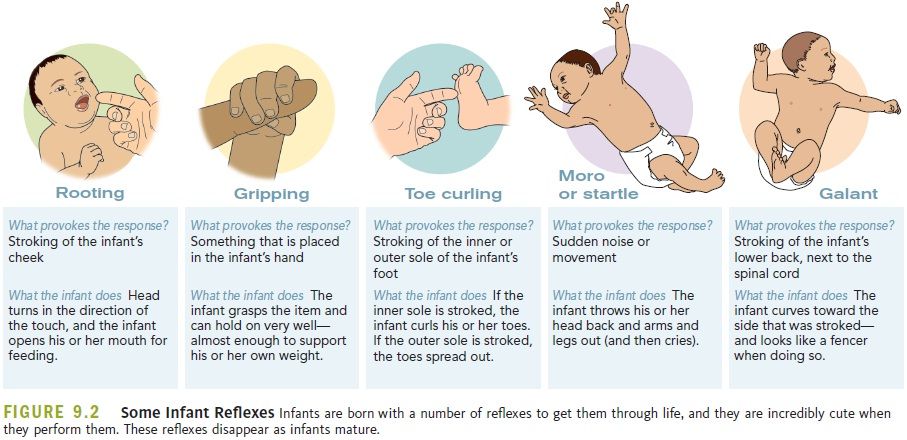

A normal, full-term baby is also programmed to initiate and enter into a bonding relationship. Crying and making other noises, smiling, searching for the breast, and seeking eye contact give cues for a caring adult to respond.

When a caregiver consistently responds to an infant’s needs, a trusting relationship and lifelong attachment develops. This sets the stage for the growing child to enter healthy relationships with other people throughout life and to appropriately experience and express a full range of emotions.

An optimum opportunity

Dr. Steinfeld is a developmental and behavioral pediatrician at UC Davis Medical Center and UC Davis Children's Hospital in Sacramento.

But what happens when things don’t work out so well? What if babies and their mothers are separated at birth, as when babies are premature or ill and need special care? Or babies who are placed for adoption and may not meet their adoptive mother for quite some time after birth? Sometimes a new mother feels depressed or incapacitated after delivery and doesn’t feel like interacting with her newborn.

Fortunately, humans are not completely dependent on those early moments and have many opportunities to bond appropriately throughout the first year of life. We know that mothers who adopt babies and even older children are able to form normal attachment relationships.

Still, the first few days of life are believed to offer an optimum opportunity for bonding to take place. Standard practice in most U.S. hospitals allows mothers and babies as much time as possible together after birth. Even when babies are born ill or premature, the importance of bonding is recognized. Whenever possible, health care providers in intensive care units try to create opportunities for parents to spend time holding and caring for their babies.

Dads and siblings, too

Babies who are held and comforted when they need it during the first six months of life tend to be more secure and confident as toddlers and older children.

Is it important for fathers to bond with their babies? Absolutely. New fathers often feel less confident than new mothers around a baby, and may feel excluded in the close relationship that develops between the mother and baby. If a baby is breastfed, fathers may be uncertain about what activities they can engage in with the new baby.

Like mothers, fathers need quiet time to spend holding their new babies close, gazing into their eyes, talking to them and comforting them when distressed. Fathers may wish to take walks with their babies tucked into a Snugli-type carrier or simply hold a quiet baby while reading or watching TV.

Brothers and sisters also need time and opportunities to establish a relationship with a new baby. You might offer young children who are too unreliable to hold a baby safely to have brief, supervised periods playing next to a brother or sister in a large crib or playpen. Such times often elicit unique responses of excitement and joy from the baby and allow loving relationships to develop successfully.

The 'spoiling' myth

While bonding does not occur instantly for everyone, it should be well established within the first few months after you bring your baby home.

The importance of bonding with the primary caregiver cannot be overestimated. Failure to do so profoundly affects future development and the ability to form healthy relationships as an adult.

I urge parents to give themselves plenty of time with their baby and to follow their instincts. Respond to the baby’s cues, and offer love and comfort when distressed.

Contrary to the “wisdom” in past generations, responding quickly to crying with holding and nursing will not “spoil” a baby. Instead, babies who are held and comforted when they need it during the first six months of life tend to be more secure and confident as toddlers and older children.

Seek help if you feel that bonding is not progressing as it should. While bonding does not occur instantly for everyone, it should be well established within the first few months after you bring your baby home. For any problem with your baby, ask your physician for help if you feel there is something wrong.

Bonding with your baby | Pregnancy Birth and Baby

Bonding with your baby | Pregnancy Birth and Baby beginning of content5-minute read

Listen

How do babies form attachments?

Attachment is when a baby and caregiver form a strong connection with each other, emotionally and physically.

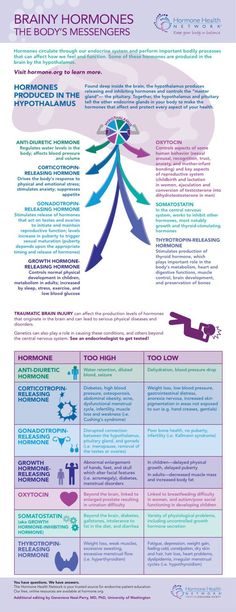

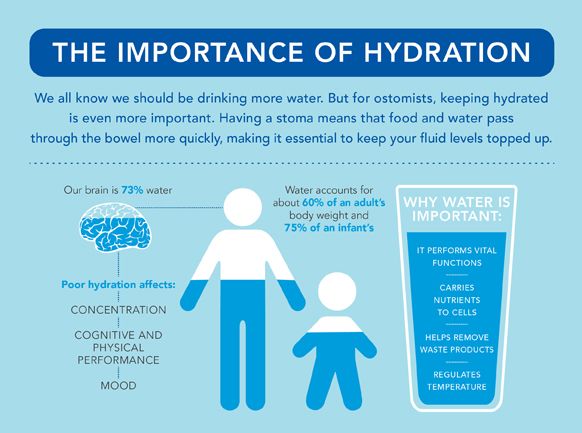

Bonding with your baby is important. It helps to release hormones and chemicals in the brain that encourage rapid brain growth. Bonding also promotes the development of connections between brain cells that are critical for learning; the growth of your baby's body; and the positive development of your baby's sense of who they are and how they deal with feeling upset.

Newborns don't know what they need. They have to be helped by a caregiver who will calmly respond to their physical needs and also provide plenty of love.

Who do babies form attachments to?

Babies usually attach to their main caregiver, but they can certainly bond with other people.

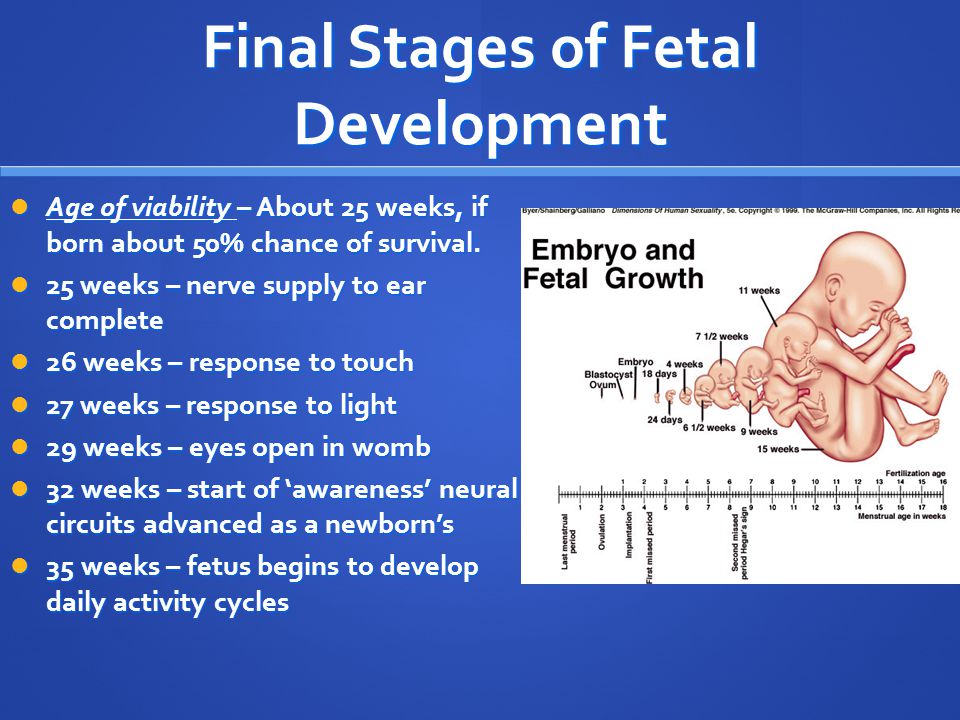

It's usual for a baby to attach to their mother, since by about week 31, a baby can recognise and be soothed by the mother's voice while in the womb. By the time they're born, newborns can even recognise some sounds of their mother's native language.

The father, grandparents and significant childcare workers can also bond with a baby. This is particularly important if a mother is finding it difficult to form an attachment, is depressed, or there is some other reason why she can't pay full attention to her baby.

This is particularly important if a mother is finding it difficult to form an attachment, is depressed, or there is some other reason why she can't pay full attention to her baby.

If you are the baby's mum, and they form attachments with other important people, this does not mean your baby will be less attached to you. It helps your baby to learn about being close to people.

How do I bond with my baby?

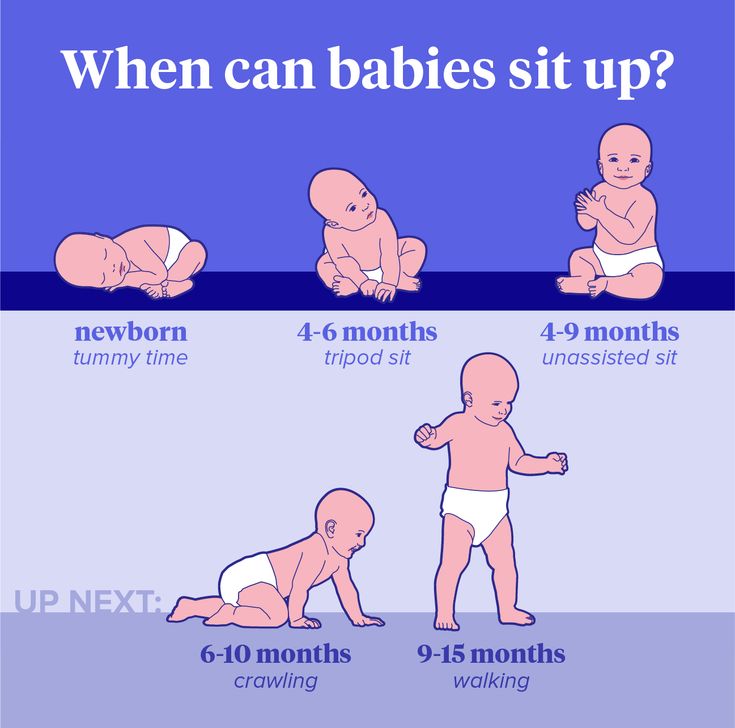

When you respond to your newborn's needs, you will probably start seeing behaviour or signals that show that he or she is attached to you. These will depend on their age and level of development and could include:

- making eye contact with you

- smiling, cooing, laughing or making other noises directed at you

- holding out their arms to you

- crawling after you

- copying you

- crying for what they need while looking at you

- looking interested in something you're doing

Responding to your baby

You can't spoil a baby by giving them too much attention. They need you to help them with the things they can't do for themselves — whether it's changing their nappy, helping alleviate their pain or hunger, providing warmth, or giving them plenty of affection and play. Responding to what they want and need builds their trust in you, and helps them feel confident.

They need you to help them with the things they can't do for themselves — whether it's changing their nappy, helping alleviate their pain or hunger, providing warmth, or giving them plenty of affection and play. Responding to what they want and need builds their trust in you, and helps them feel confident.

Mothers are biologically designed to act when their babies cry so you may feel anxious if you can't respond to your baby straight away. If you can see that your baby has everything they need and are safe, reassure them that you'll be there as soon as you can. When you're with your baby again, calmly sooth and comfort them.

Ways to bond with your baby

Here are some bonding techniques you can try:

- Learn to read your baby's cues and signals to you and let your baby know you understand.

- Copy your baby's noises or signals, then wait for your baby to respond before continuing.

- Once you have learned what your baby likes, do it regularly.

- Start new activities gently, rather than abruptly, and talk calmly about what you're doing.

- Soothe and cuddle your baby when they're upset.

- Hold your baby on the left side of your chest, so they can hear your heartbeat.

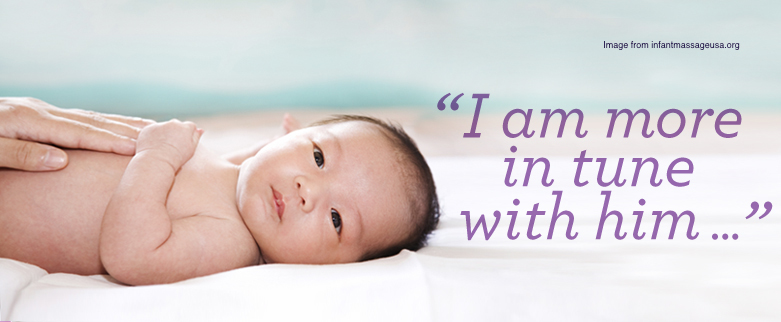

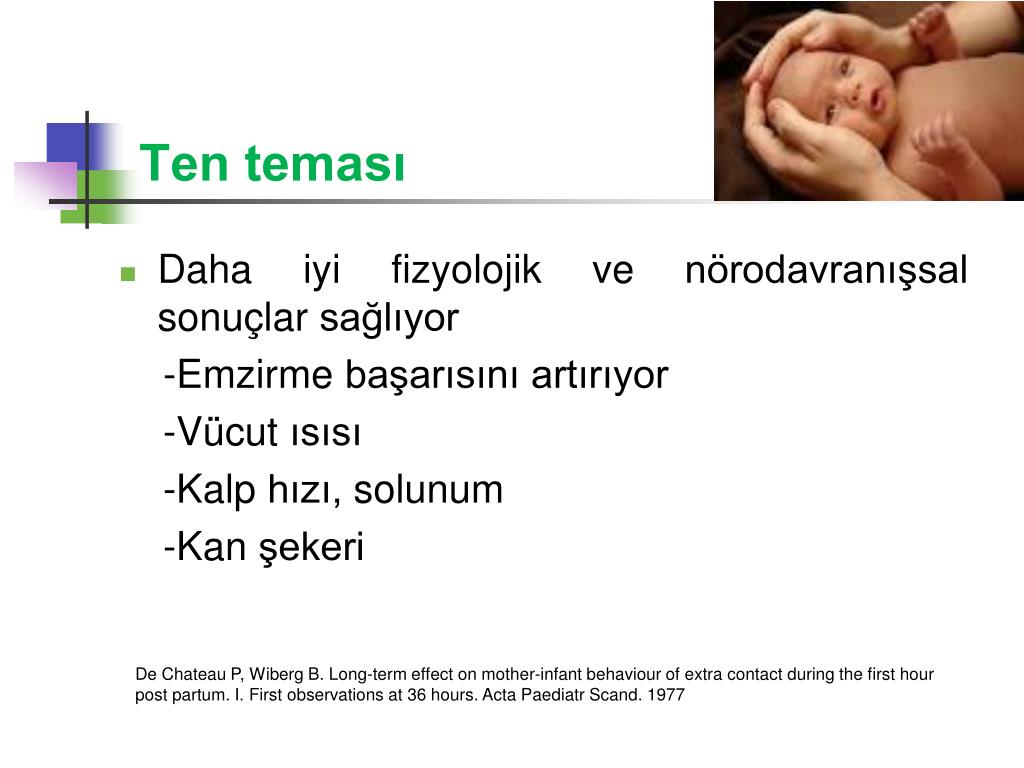

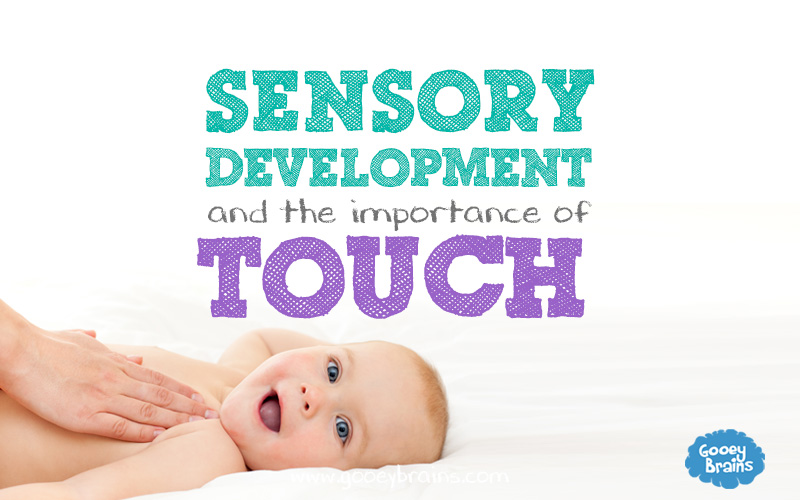

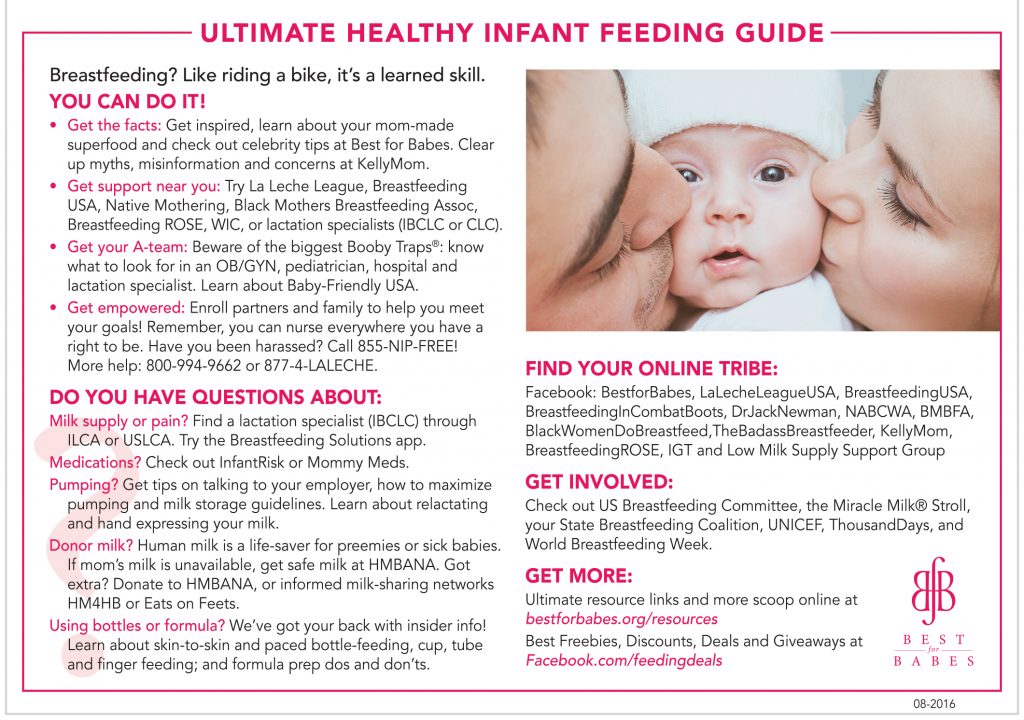

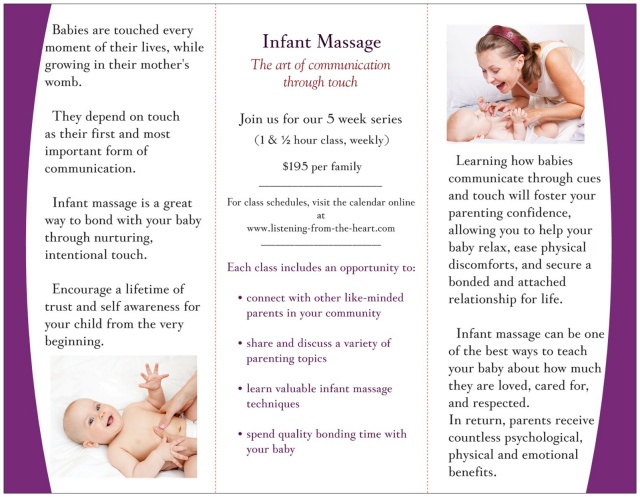

- Provide skin-to-skin contact (for example, while breastfeeding). You could also massage your baby.

- Smile and laugh while looking into your baby's eyes.

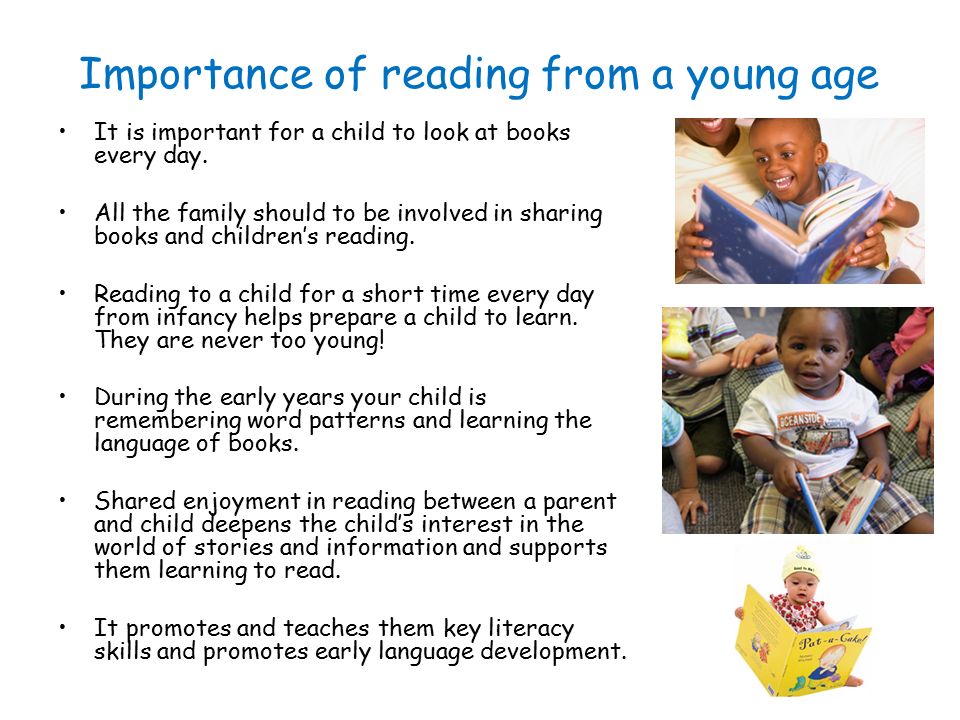

- Talk, sing, read books and play simple games together.

- Bathe your baby before bed.

What if I'm not bonding with my baby?

Some parents experience an instant connection to their baby within the first 24 hours after birth and describe it as an overwhelming feeling of love and protectiveness.

Don't worry if you don't feel this straight away. Although attachment is important for your baby, relationships can sometimes take a while to grow and you may find that it takes you days, weeks or even months to bond with your baby.

Communicate regularly with family members and friends and don't put extra pressure on yourself. The lack of a strong, initial bond does not mean you're not a 'natural' parent.

If you suspect you may be experiencing postnatal depression, talk to your doctor or other healthcare professional, such as a child health nurse.

- Talk to your doctor, child health nurse or midwife.

- Find a parenting helpline that suits you here.

- Call Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636.

Speak to a maternal child health nurse

Call Pregnancy, Birth and Baby to speak to a maternal child health nurse on 1800 882 436 or video call. Available 7am to midnight (AET), 7 days a week.

Sources:

BabyCenter Australia (Seven reasons babies cry and how to soothe them), Beyond Blue (Perinatal depression), Centre for Community Child Health (The First Thousand Days - an evidence paper), Centre of Perinatal Excellence (Bonding with your baby), Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (Neurobiology of culturally common maternal responses to infant cry), Raising Children Network (Bonding and attachment: newborns), Raising Children Network (Can you spoil a baby?), Women's and Children's Health Network (Attachment – babies, young children and their parents), Acta Paediatrica (Language experienced in utero affects vowel perception after birth: a two‐country study), Beyond Blue (Getting to know your baby)Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Last reviewed: February 2021

Back To Top

Related pages

- Bonding with your baby during pregnancy

- What is kangaroo care?

Need more information?

First 1000 days: conception to two years | Raising Children Network

The first 1000 days of life are key to lifelong health and wellbeing.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Bonding and attachment: newborns | Raising Children Network

Bonding with newborns happens when you respond consistently to your baby with love, warmth and care. Bonding and attachment are vital to baby development.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Bonding with premature babies in the NICU | Raising Children Network

For parents with premature babies in the NICU, bonding might seem hard. This guide explains how to use touch, song, play and daily care to bond with baby.

This guide explains how to use touch, song, play and daily care to bond with baby.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

The first 1,000 days

The first 2 years of a baby's life can impact their health and wellbeing later on. Here's what you can do to give your child the best possible start.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Bonding with your kids | Support For Fathers

Bonding with your kids. Support For Fathers, Fatherhood and Family Relationship Support. Relationships Australia Victoria RAV. Fatherhood Resources Library.

Read more on Support for Fathers website

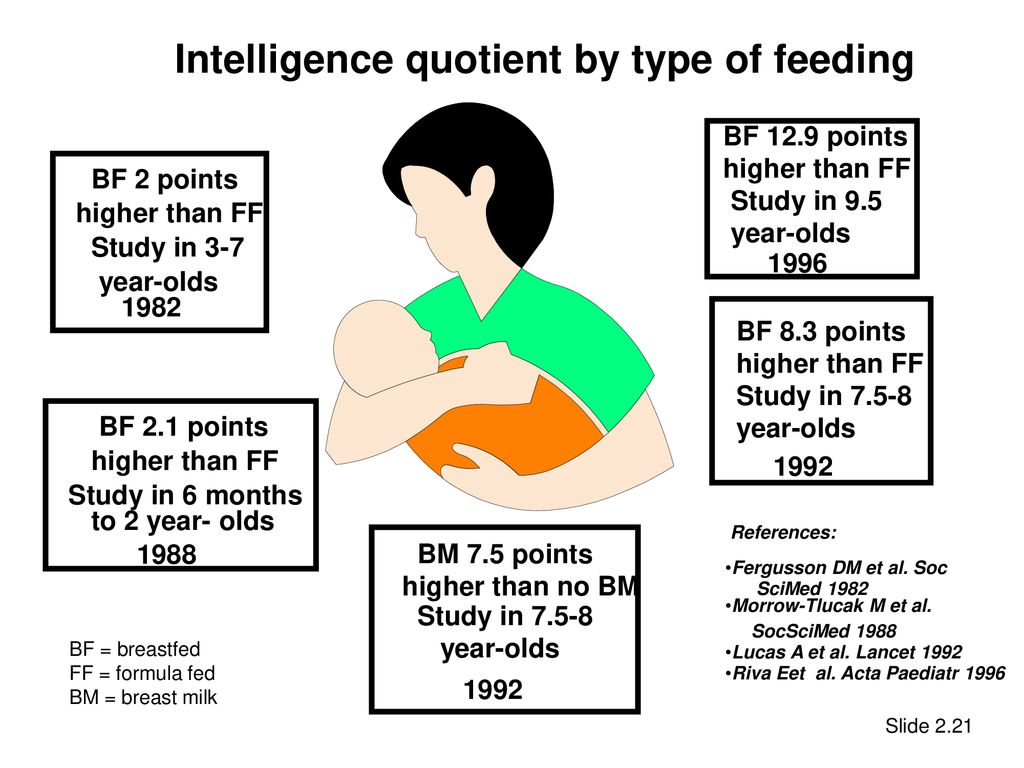

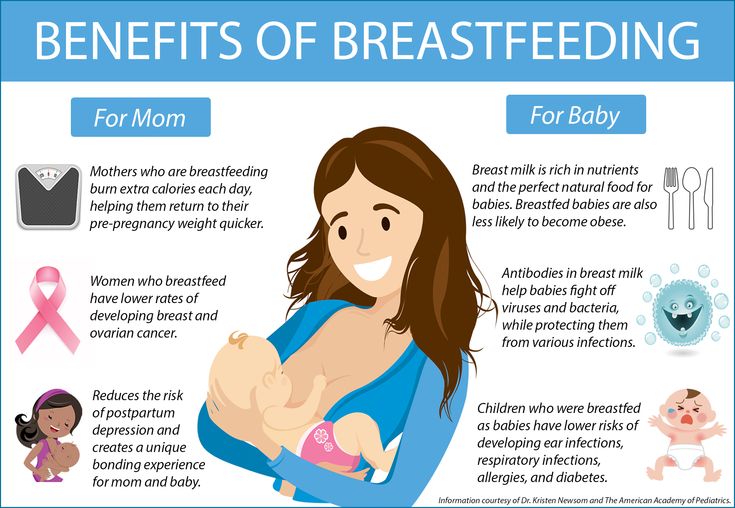

Breastfeeding your baby

Breastfeeding is the most natural way to feed your baby, providing all the nutrition your baby needs during the first six months of life and a loving bond with your baby.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Breastfeeding attachment techniques | Raising Children Network

Good attachment is key to successful breastfeeding. Baby-led attachment is when you let baby find the breast. Mother-led attachment is when you attach baby.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Baby's first 24 hours

There is a lot going on in the first 24 hours of your baby's life, so find out what you can expect.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Dads: premature birth and premature babies | Raising Children Network

After a premature birth, it can be hard for dads. Our dads guide to premature babies and birth covers feelings, bonding, and getting involved with your baby.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

A day in the life of a newborn

Most babies will start to settle into a daily pattern of sleeping, feeding and playing, whether you follow what your newborn does or establish a simple routine.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Disclaimer

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is not responsible for the content and advertising on the external website you are now entering.

OKNeed further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Video call

- Contact us

- About us

- A-Z topics

- Symptom Checker

- Service Finder

- Linking to us

- Information partners

- Terms of use

- Privacy

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is funded by the Australian Government and operated by Healthdirect Australia.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is provided on behalf of the Department of Health

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby’s information and advice are developed and managed within a rigorous clinical governance framework. This website is certified by the Health On The Net (HON) foundation, the standard for trustworthy health information.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

Formation of mother's attachment to the child during pregnancy

"Questions of Psychology" - No. 1997. No. 6, P. 38–47

Brutman V.I., Radionova M.S.

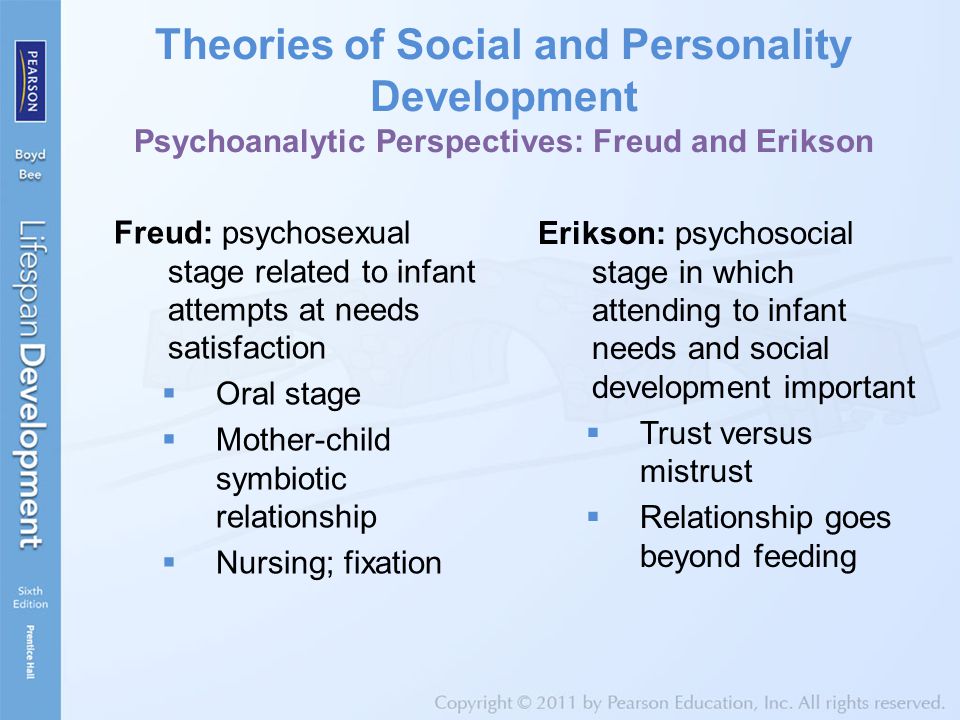

The phenomenon of attachment (attachement) between mother and child has been the focus of attention of researchers in recent years. He is given great importance in the formation of effective maternal behavior, in the adaptation of the child to the world around him, in his harmonious development. Among the studies devoted to this topic, two main areas can be distinguished: comparative ethological and psychoanalytic. nine0008

He is given great importance in the formation of effective maternal behavior, in the adaptation of the child to the world around him, in his harmonious development. Among the studies devoted to this topic, two main areas can be distinguished: comparative ethological and psychoanalytic. nine0008

Within the framework of the ethological direction, attachment is considered as an innate biopsychic mechanism that unites most animal species with humans (J. Bowlby, M. D. Ainsworth, D. N. Stern, M. Hubert, K. Lorenz, etc.). J. Bowlby considered attachment to be a primarily specific system, the meaning of which is to maintain the interaction between the mother and the infant, which is necessary for its survival and development. The first step to attachment, according to many authors, is the establishment of a connection as a result of early contacts within the first hours after birth. Kreisler (19)81, 1987) showed how the psychosomatic balance of the child is closely related to emotional contact with the mother. At the same time, her behavior is considered as reciprocal and complementary to the innate repertoire of the infant's behavior (D. Stern, 1977). Like any act of social behavior that is of fundamental importance for the survival of a species, attachment behavior has specific selective and triggering mechanisms: morphological features, special smells, movements and postures. The smile of an infant (R. Spits) is considered to be a specific human stimulus. More phylogenetically ancient, but no less significant for the emergence of attachment, is olfactory stimulation (Montagner et al., 1974, Engen et al, 1965, Steiner, 1979), along with visual cues, tactile sucking, and acoustic stimulation. The works of this direction analyze how the synchronicity of interaction in the "mother-child" dyad and the personal qualities of the mother affect the quality of the child's attachment and its strength.

At the same time, her behavior is considered as reciprocal and complementary to the innate repertoire of the infant's behavior (D. Stern, 1977). Like any act of social behavior that is of fundamental importance for the survival of a species, attachment behavior has specific selective and triggering mechanisms: morphological features, special smells, movements and postures. The smile of an infant (R. Spits) is considered to be a specific human stimulus. More phylogenetically ancient, but no less significant for the emergence of attachment, is olfactory stimulation (Montagner et al., 1974, Engen et al, 1965, Steiner, 1979), along with visual cues, tactile sucking, and acoustic stimulation. The works of this direction analyze how the synchronicity of interaction in the "mother-child" dyad and the personal qualities of the mother affect the quality of the child's attachment and its strength.

In contrast to ethologists, who were primarily interested in the interaction of the child and the mother in the postpartum period, psychoanalytically oriented researchers have shifted their focus of interest to the psychic history of the mother herself and the period of her pregnancy, supplementing objective studies of attachment with the concept of their "phantasmatic" interaction. They focused on the significance of the formation of images of the child, in the imagination of the expectant mother, in her acceptance of her newborn child. The role of fantasies of pregnant women in setting up the “maternal instinct” is the subject of research, Deutsch,1944; Bibring et al, 1961; D. Pines, 1972; S. Lebovici, 1990, C. Bonnet, 1992; Savatie 1992. It has been found that mother's fantasies about pregnancy and child can cause relationship dysfunction in the dyad, disrupting normal attachment. The mother's relationship with her child is determined by her own history before and after birth. So, according to D.Pine, internal conflicts and anxieties related to past stages of development come to life at a given crisis point in human life (pregnancy) and affect the real image of the child. These conflicts may include both positive and negative manifestations of both one's "ego" and the woman's partner, include the continuation of ambivalent relationships with her parents and siblings (Deutsch,1944; Bibring et al, 1961).

They focused on the significance of the formation of images of the child, in the imagination of the expectant mother, in her acceptance of her newborn child. The role of fantasies of pregnant women in setting up the “maternal instinct” is the subject of research, Deutsch,1944; Bibring et al, 1961; D. Pines, 1972; S. Lebovici, 1990, C. Bonnet, 1992; Savatie 1992. It has been found that mother's fantasies about pregnancy and child can cause relationship dysfunction in the dyad, disrupting normal attachment. The mother's relationship with her child is determined by her own history before and after birth. So, according to D.Pine, internal conflicts and anxieties related to past stages of development come to life at a given crisis point in human life (pregnancy) and affect the real image of the child. These conflicts may include both positive and negative manifestations of both one's "ego" and the woman's partner, include the continuation of ambivalent relationships with her parents and siblings (Deutsch,1944; Bibring et al, 1961). It follows that in order for a feeling of attachment to a child to be formed, a woman must integrate reality and subconscious fantasies, hopes and dreams related to a child during pregnancy (Pines, 1972).

It follows that in order for a feeling of attachment to a child to be formed, a woman must integrate reality and subconscious fantasies, hopes and dreams related to a child during pregnancy (Pines, 1972).

So, from a psychoanalytic standpoint, a mother's feeling of attachment to her child does not arise suddenly - after his birth, but goes through a long path of formation, starting from the period of gestation (and possibly even earlier) and continues after childbirth, in close contact with the child. Thus, the psychoanalytic line of research brings the problem of attachment into a "purely human plane." nine0008

Analyzing the scientific literature, we did not find any works that would raise the question of the relationship between the content of experiences (the fantasies of pregnant women) and the physiological (instinctive) mechanisms underlying maternal attachment to the child. The reason for raising the question in this plane was the analysis of our long-term studies of the psychological characteristics of carrying desired and unwanted pregnancies, which indicates the important role of the bodily sensations of pregnant women and emotional reactions in the formation of women's attachment to their child. nine0008

nine0008

Under our observation were 169 primiparous women aged 15 to 29 from socially disadvantaged groups of the population. The vast majority of them (84%) were single and gave birth in celibacy, 91% did not have their own housing and lived in parental families; 69% of women classified themselves as poor and low-income segments of the population, 72% did not work and were dependent on relatives, husbands, cohabitants. Of this number, 54 women considered their pregnancy desirable and retained their motherhood, the remaining 115 abandoned the child immediately in the maternity hospital. This group of "refuse women" is accepted by us as a verified model of unwanted pregnancy. The high proportion of "refuseniks" in the material is associated with the characteristics of the sample. nine0008

First, let's dwell on the nature of bodily sensations and emotional reactions in women carrying a desired pregnancy.

As is known, one of the main neoplasms during pregnancy in women is the occurrence of intraceptive sensory experience of interaction with the fetus. The formation of this experience is due to the fact that, starting from the second half of pregnancy, all women have natural sensations that are directly related to the movements of the developing fetus. Usually, women subjectively highlight these sensations and immediately distinguish them. They emphasize their unusualness, incomparability with any other previously experienced bodily phenomena. Describing these natural sensations of a woman, they usually resort to extremely figurative comparisons. This is especially emphasized at first, while the fetus is still small. Trying to convey their feelings, pregnant women tell how at the beginning they experience very vague, weak, poorly localized “shocks”, “indistinct movements”. For comparison, they use metaphors that correspond to their mood: “as if a fish swam”, “warm waves”, “soft touches”, “as if touched slightly”, “moved gently”, etc. The sensations experienced by a pregnant woman are usually emotional painted in pleasant colors. Pregnant women tell how they are constantly "listening", impatiently "waiting" for these signals, endowing them with an important meaning, as if "meditating" on these sensations.

The formation of this experience is due to the fact that, starting from the second half of pregnancy, all women have natural sensations that are directly related to the movements of the developing fetus. Usually, women subjectively highlight these sensations and immediately distinguish them. They emphasize their unusualness, incomparability with any other previously experienced bodily phenomena. Describing these natural sensations of a woman, they usually resort to extremely figurative comparisons. This is especially emphasized at first, while the fetus is still small. Trying to convey their feelings, pregnant women tell how at the beginning they experience very vague, weak, poorly localized “shocks”, “indistinct movements”. For comparison, they use metaphors that correspond to their mood: “as if a fish swam”, “warm waves”, “soft touches”, “as if touched slightly”, “moved gently”, etc. The sensations experienced by a pregnant woman are usually emotional painted in pleasant colors. Pregnant women tell how they are constantly "listening", impatiently "waiting" for these signals, endowing them with an important meaning, as if "meditating" on these sensations. Periodically arising movements enliven in them a stream of fantasies associated with a child and future motherhood. nine0008

Periodically arising movements enliven in them a stream of fantasies associated with a child and future motherhood. nine0008

Subsequently, as the fetus grows, the sensual component of these sensations becomes brighter, acquires a shade of objectivity. Women experience "distinct pushes", "coups", "beats", "pushing". Pregnant women during this period usually begin to interpret the behavior of the unborn baby: “woke up ...”, “he worries mom ...”, “naughty ...”, etc. You can see how a pregnancy endowed with meaning inspires the expectant mother, creates an appropriate affective background with which she inspires her future baby. Therefore, in their experiences, his presence evokes a feeling of tenderness, is painted in warm emotional tones. To express their feelings, as a rule, diminutive suffixes are used: “my little one”, “little one”, “bunny”, etc. Thoughts about him cause a smile. Some women are so captured, immersed in these experiences, that childish features also begin to appear in their behavior. They become more sensitive and suggestible, helpless and softened. As D. Pines writes, "... rationality recedes and even the most educated enter the magical world of childhood." (D. Pines, 1990). According to researchers, during this period of pregnancy, an internal dialogue between mother and child usually occurs. A special emotional state that develops during pregnancy contributes to building the image of the child and, as evidenced by the studies of Kopyl, Baz, Bazhenova (1994), is included in her self-awareness.

They become more sensitive and suggestible, helpless and softened. As D. Pines writes, "... rationality recedes and even the most educated enter the magical world of childhood." (D. Pines, 1990). According to researchers, during this period of pregnancy, an internal dialogue between mother and child usually occurs. A special emotional state that develops during pregnancy contributes to building the image of the child and, as evidenced by the studies of Kopyl, Baz, Bazhenova (1994), is included in her self-awareness.

However, in the process of development of even the most desired and meaningful pregnancy, women have conditions for the occurrence of a number of negative changes in the emotional sphere. At the physiological level, this trend is associated with the appearance of a number of completely natural endocrine-somatic and psychophysiological changes in the body of a pregnant woman. At the semantic level, this corresponds to a number of negative trends. Here are the fears and fears associated with the upcoming birth, sometimes reaching panic - “Will I bear the birth?”; and uncertainty in their abilities to give birth and become a "full" mother; and fear for the health and fate of the unborn child, concern about the deterioration of the material well-being of one's family, about the possible infringement of personal freedom, and finally experiencing one's bodily metamorphosis and, associated with this, experiencing one's sexual unattractiveness. Both of these opposite psychological plans develop simultaneously and, as our observations show, even the most desired pregnancy is stained with a special dual, contradictory, “binary”, according to L.S. Vygotsky, an affect in which joy, optimism and hope coexist, and - alert expectation, fear, and sadness. This ambivalent complex arises at a very early stage, when a woman is forced to decide whether to maintain or terminate a pregnancy. As the pregnant woman realizes her new quality, only separate and each time certain facets of this complex are highlighted in her mind, changing the consciousness and self-consciousness of the woman, including new images and motives in it. The ambivalent affective background reaches its apogee at the moment of childbirth, and its strength and severity of experiences reach an ecstatic level. At this moment (and this is especially pronounced in primiparas), painful contractions and attempts are emotionally tinged with joyful impatience, expectation, and the delight of accomplishment.

Both of these opposite psychological plans develop simultaneously and, as our observations show, even the most desired pregnancy is stained with a special dual, contradictory, “binary”, according to L.S. Vygotsky, an affect in which joy, optimism and hope coexist, and - alert expectation, fear, and sadness. This ambivalent complex arises at a very early stage, when a woman is forced to decide whether to maintain or terminate a pregnancy. As the pregnant woman realizes her new quality, only separate and each time certain facets of this complex are highlighted in her mind, changing the consciousness and self-consciousness of the woman, including new images and motives in it. The ambivalent affective background reaches its apogee at the moment of childbirth, and its strength and severity of experiences reach an ecstatic level. At this moment (and this is especially pronounced in primiparas), painful contractions and attempts are emotionally tinged with joyful impatience, expectation, and the delight of accomplishment. Paraphrasing L.S. Vygotsky, we can say that childbirth, like creative ecstasy, “is the moment in which both opposite emotional planes are combined in one act, exposing their opposite, bringing contradictions to their climax” and at the same time discharging the duality of feelings that has been growing all the time in course of pregnancy. nine0008

Paraphrasing L.S. Vygotsky, we can say that childbirth, like creative ecstasy, “is the moment in which both opposite emotional planes are combined in one act, exposing their opposite, bringing contradictions to their climax” and at the same time discharging the duality of feelings that has been growing all the time in course of pregnancy. nine0008

Delivery, as a rule, sharply shifts the whole tone of affect to one side. The emotional state of the puerperal is colored by a blissful feeling of joy, calmness, pacifying prostration. A blissful smile shines on his face; women look with delight at the face of their newborn child.

Thus, in the case of carrying a desired pregnancy, fetal movements occur within natural time limits; experienced as "natural"; as the fetus grows, sensations become more and more distinct, their perceptual component transforms from vague protopathic into a more concrete epicritical one, and the woman's sensual sphere acquires an ambivalent emotional tonality. nine0008

nine0008

Subjective feelings associated with an unwanted pregnancy.

An analysis of the subjective experiences of women carrying an unwanted pregnancy showed that their bodily symptoms and emotional reactions have a number of fundamental differences from those described above. With all the variety of individual differences, it is possible to identify common features and distinguish two extreme variants of psychological status. In the first case, there is a kind of "ignoring" the symptoms of pregnancy, a weak emotional reaction and a distortion of the idea of the terms of pregnancy. The second, as it were, opposite variant is characterized by the fact that throughout pregnancy, women experience hypersensitivity to bodily phenomena, affective tension, fear, and depression. In the first case, women feel quite well throughout their pregnancy. Significantly less often than in cases of desired pregnancy, they have the phenomena of early toxicosis. This reduced sensitivity persists in relation to fetal movements. nine0008

nine0008

Let's take one observation as an example.

Lena, aged 17, is married and already has one child. The second pregnancy occurred 1.5 years after the first and ended with the birth of a full-term girl. In the maternity hospital, the woman announced that she was giving up the baby. She explained her decision by the fact that pregnancy, unlike the first one, was unwanted and unexpected from the very beginning. She told that despite the fact that she lived with her husband and almost did not protect herself from pregnancy, the disappearance of menstruation was not at all worried, because “For some reason, she thought) that she couldn’t get pregnant. She explained her condition by the fact that she had repeatedly been diagnosed with ovarian dysfunction. I found out that I was pregnant "accidentally" only when fetal movements occurred. The husband was categorically against the appearance of another child, since he lost his job and could not provide for his family. In my heart I also did not want a child, but I was ashamed to refuse him. It was especially uncomfortable in front of the mother, who already knew about the pregnancy. At the same time, she did not want to quarrel with her husband, but to persuade and even discuss this problem with him, she considered it useless. After a short period of confusion, tension and concern, she calmed down, decided "not to worry herself ahead of time." nine0004

It was especially uncomfortable in front of the mother, who already knew about the pregnancy. At the same time, she did not want to quarrel with her husband, but to persuade and even discuss this problem with him, she considered it useless. After a short period of confusion, tension and concern, she calmed down, decided "not to worry herself ahead of time." nine0004

All subsequent months, despite the rapid weight gain and a noticeable increase in the abdomen, she felt cheerful, energetic, did not feel tired at all. Fetal movements were very weak, sometimes almost imperceptible. At times, "... I even seemed to forget that I was pregnant ...". She worked a lot, worried about the health of her first daughter, who at that time often had colds. Sexual attraction was preserved and even slightly increased.

Such a state, as the woman notes, was very different from the one she experienced when she was carrying her first - the desired child. Then she was constantly unwell, was drowsy and lethargic, from the very beginning and almost until the end of pregnancy she had nausea, a negative reaction to smells. nine0004

nine0004

In the case described above, one can clearly see the difference in the experiences of one and the same woman carrying first a desired and then an unwanted pregnancy. It is noteworthy that in the case of an unwanted pregnancy in a woman, as in many similar observations, a kind of hypoesthesia of the bodily manifestations of pregnancy and a special psychological state corresponding to it, which we called "athiophoriognosia", are formed. Thiophoria qeoga (Greek) - pregnancy. Hence the term arises by analogy with anosognosia. nine0008

As our observations show, atiophoriognosia in “mild” cases is manifested by a kind of “forgetting” of pregnancy, ignoring its symptoms, and sometimes a blatant distortion of ideas about its terms. In more pronounced cases, women are generally convinced of the absence of pregnancy, even if there are its pronounced signs (absence of menstruation, breast engorgement, an increase in the volume of the abdomen). Usually in such cases (as was the case with the observation presented above), they seek to explain these symptoms with "logical" arguments (disease, "habitual" menstrual irregularities, etc. ). nine0008

). nine0008

In more pronounced cases, pregnancy is denied in the presence of its unconditional signs (fetal movement). So, one woman who gave birth again for a long time mistook the movements of the fetus for the accumulation of gases in the intestines. She "treated" herself by doing daily enemas. The literature describes cases where women denied pregnancy even after the onset of labor (Pemberthorn, D.A., Bendy, D.K. 1973). In addition, according to our observations, such women usually try at all costs to avoid medical diagnosis of pregnancy. Unlike other pregnant women, even in the later stages, they do not have natural motor "calmness". There is no feeling of motor awkwardness, excessive own weight. Moreover, sometimes there is some elation that does not correspond to the circumstances, inadequate optimism about the future of her and her abandoned child (for example, Lena reassured herself that her child would definitely be adopted and she would certainly fall into “good hands”). This is the so-called euphoric type of atiophoriognosia. Apparently, mechanisms of protective psychological repression of unwanted experiences play a certain role in the formation of this state. nine0008

Apparently, mechanisms of protective psychological repression of unwanted experiences play a certain role in the formation of this state. nine0008

However, another interpretation of the phenomenon of atiophoriognosia is not excluded.

The second, opposite, variant of the psychological state when experiencing an unwanted pregnancy is characterized by hyperergy of bodily symptoms, pronounced rigidity of negative affect - fear, depression.

As an example, the following observation.

Lilya S., 23 years old. Lives in an unregistered marriage, has a child 1 year 2 months. The first pregnancy was desired with the normal development of maternal feelings and attitudes, the second - accidental, occurred 3.5 months after the medical abortion. Despite the fact that she discovered pregnancy quite early and realized its extreme undesirability and futility, it turned out to be insufficiently focused in achieving the goal - termination of pregnancy. I dragged out with analyzes, was late for a consultation, found a lot of distracting everyday circumstances. When she discovered that all the possible terms for an abortion had passed, she began to blame her husband for not forcing her to have an abortion on time. She accused the doctors of callousness - "did not enter the position ...", etc.

When she discovered that all the possible terms for an abortion had passed, she began to blame her husband for not forcing her to have an abortion on time. She accused the doctors of callousness - "did not enter the position ...", etc.

In the first months of pregnancy she was extremely touchy, tearful. After the beginning of the stirring, a feeling of annoyance grew. Fetal movements were unpleasant, disturbing, painful. I could not find a place for myself from painful tremors in my stomach. To alleviate the condition, she lay down on her stomach, pressed it with her hands, pounded on it with her palms. She often woke up in the middle of the night from unpleasant dreams in which the child seemed scary and miserable at the same time. To reduce pain in the abdomen, she uncontrollably took analgesics. Despite the poor health of the doctors, she did not visit. Repeatedly, even in the later stages, for the purpose of terminating a pregnancy, she used medications, steamed in a bathhouse . . Her mood was constantly lowered, at times drearily-tense. At times she felt a sense of disgust for the unborn child. She was convinced that "such a child simply cannot be healthy ... normal." nine0004

. Her mood was constantly lowered, at times drearily-tense. At times she felt a sense of disgust for the unborn child. She was convinced that "such a child simply cannot be healthy ... normal." nine0004

In this observation, there is a picture of bodily-emotional phenomena that is directly opposite to the first case, which can be called the term "pregnancy hyperpathy". Fetal movements in such women, even at the very beginning, are accompanied by sharply negative sensations and experiences. Further, sometimes up to childbirth, the consciousness of a woman is filled with searches for ways of fruition. For some, an unwanted pregnancy is accompanied throughout by a deep sense of disgust, disgust and even hatred for the unborn child, which gives rise to especially vivid, painful "infanticide fantasies" in which she torments and even kills her unborn child. Accordingly, the bodily symptoms of pregnancy have a negative connotation. The tremors and movements of the fetus are unpleasant, emphatically interfering, excessively painful. Their occurrence is accompanied by an increase in general mental stress, depressing fantasies and memories associated with pregnancy and the situation around it. nine0008

Their occurrence is accompanied by an increase in general mental stress, depressing fantasies and memories associated with pregnancy and the situation around it. nine0008

Thus, in cases of carrying an unwanted pregnancy, the emotional manifestations of women are sharply polarized. In some cases, this is a stable negative, depressive background of mood. In others, there is emotional exclusion, indifference, and even a certain euphoria.

DISCUSSION

Thus, observations show that the psychological state of women in cases of desired and unwanted pregnancy differ significantly. And the subjective sensations associated with the movement of the fetus become the central link of these differences. To explain this phenomenon, we use several reasons. nine0008

First, it seems quite obvious that the complex of psychophysiological changes that form the complex sensory-emotional phenomenon of “fetal movement” is based on a purely physiological complex. The primary source of these bodily sensations is the mechanical irritation of the peripheral receptor fields of the intra- and proprioceptive analyzers (body, neck, ligamentous apparatus of the uterus. When the fetus reaches a size that allows direct stretching of the abdominal wall, and then the vaginal segments, extraceptive, skin sensitivity is also included in the formation of the sensation. From this time on, the jolts and movements become more distinct, and the women's self-report regarding sensations becomes more definite.0008

When the fetus reaches a size that allows direct stretching of the abdominal wall, and then the vaginal segments, extraceptive, skin sensitivity is also included in the formation of the sensation. From this time on, the jolts and movements become more distinct, and the women's self-report regarding sensations becomes more definite.0008

The psychological result of such stimulation is the formation of a new mental reality, the content of which can be characterized as the formation of a bodily-sensory and semantic boundary between the fetus and mother (Shmurak Yu.I., 1994). From our point of view, from the moment the movements begin, the corporality of the future mother, as it were, “splits” into “I” (“my body”) and not-I (“other”). What does this other - "not-I", up to childbirth, remain deeply contradictory. So, before the appearance of movement, the fetus, being topographically embedded and “sensually dissolved” in the inner space of the expectant mother, remains in fact not separated from this “I” and is still accessible mainly to abstract, and not concretely sensual (extraceptive) cognition. nine0008

nine0008

A special psychological reality arises from the appearance of fetal movements. If before that a woman perceived the world only in the extremes of an alternative semantic continuum: “Mine” and “Alien” (I and not-I), then from this moment a new, as it were, “intermediate meaning” begins to be built. Coming out of the vague, blurry, generally incorporeal, as it was in the first half of pregnancy (up to the first movements), the fetus begins to be identified by the mother as something already existing, different from her. This other is already quite concrete in its corporality, but at the same time it is vitally inseparable. A kind of “double I” arises, in which “my child” is already a “non-I”, but at the same time still “I”. This vague experience that is difficult to convey in words is expressed in a special, purely maternal perception of one's child, which can be called the words "native child" (in the sense of the simultaneity of I and not-I). From our point of view, this period in a woman's life has a very important psychological and evolutionary meaning. At this moment, the image of the unborn child (Kopyl) is not only built into the woman’s self-consciousness, but (which is especially important!) This image is filled with a qualitatively special sensual and semantic content, which can be characterized as “unity”, “affinity”. nine0008

At this moment, the image of the unborn child (Kopyl) is not only built into the woman’s self-consciousness, but (which is especially important!) This image is filled with a qualitatively special sensual and semantic content, which can be characterized as “unity”, “affinity”. nine0008

Based on these considerations, it can be assumed that phylogenetically it has developed so that on the periphery (if viewed from the inside) of our inner space, there are zones that are endowed with the ability to participate in the formation of the deepest, vital attachments of a person. Topographically, these zones are located on the periphery of the intestinal tube. In humans, this is the mouth, the terminal sections of the rectum with the anus, as well as the vaginal-uterine complex of women, the urogenital complex of men. From a physiological point of view, these zones are associated with the process of assimilation of the "alien" (mouth) and expulsion from the body outside the part of "one's own". From a psychological standpoint, there is a transition of the "alien" ("not-I") into the "I" and, on the contrary, the alienation of a part of the "I" into another, alien - "not-I". To clarify this thesis, you can refer to, for example. Bread, once in the mouth, quickly loses its former not only purely physical, but also semantic boundaries, as if dissolving in the inner space of the “I”. From food that is “outside me”, “not-I”, it becomes “part of me”. Another example is the penis in the vagina with its intraception "destroys the semantic boundaries" of the corporality of both men and women. In this sense, it ceases to be a body belonging only to a man. A woman, merging with a man, in turn acquires a “new quality” (in a certain, rather metaphorical, sense, she “acquires a penis”). This process of "blurring" the boundaries of the body, forms a new psychological reality - a feeling of "native", in the sense - "a part of me". And, finally, the reverse process - rejection from the "I". Thus, the embryo, with its indivisibility of extra and ipraception, is deeply, intimately merged in its own sensations with the mother's corporeality.

From a psychological standpoint, there is a transition of the "alien" ("not-I") into the "I" and, on the contrary, the alienation of a part of the "I" into another, alien - "not-I". To clarify this thesis, you can refer to, for example. Bread, once in the mouth, quickly loses its former not only purely physical, but also semantic boundaries, as if dissolving in the inner space of the “I”. From food that is “outside me”, “not-I”, it becomes “part of me”. Another example is the penis in the vagina with its intraception "destroys the semantic boundaries" of the corporality of both men and women. In this sense, it ceases to be a body belonging only to a man. A woman, merging with a man, in turn acquires a “new quality” (in a certain, rather metaphorical, sense, she “acquires a penis”). This process of "blurring" the boundaries of the body, forms a new psychological reality - a feeling of "native", in the sense - "a part of me". And, finally, the reverse process - rejection from the "I". Thus, the embryo, with its indivisibility of extra and ipraception, is deeply, intimately merged in its own sensations with the mother's corporeality. The mother's body, acquiring and holding its own fetus in the intraceptive space of the uterus, is inseparable from it in its bodily sensations. On this sensual basis, apparently, they form deep protopathically colored connections that determine the feeling of "attachment" and love of the mother to the child. That is why the mother-child complex is so vital and inseparable. Therefore, the feelings of “My own child” remain for a long time. Childbearing in this regard is not the beginning of the formation of attachment between mother and child, but the beginning of the dissolution of unity. It should be noted that the new, postpartum, stage in the development of attachment is already associated with the stimulation not of the intraceptive analyzer, but of the extraceptive one, both in the mother and in the child (tactile, auditory, visual, olfactory). This stage finally builds the semantic boundaries between mother and child - and in this regard, the formation of attachment after childbirth is based on their greater separation than in the prenatal period.

The mother's body, acquiring and holding its own fetus in the intraceptive space of the uterus, is inseparable from it in its bodily sensations. On this sensual basis, apparently, they form deep protopathically colored connections that determine the feeling of "attachment" and love of the mother to the child. That is why the mother-child complex is so vital and inseparable. Therefore, the feelings of “My own child” remain for a long time. Childbearing in this regard is not the beginning of the formation of attachment between mother and child, but the beginning of the dissolution of unity. It should be noted that the new, postpartum, stage in the development of attachment is already associated with the stimulation not of the intraceptive analyzer, but of the extraceptive one, both in the mother and in the child (tactile, auditory, visual, olfactory). This stage finally builds the semantic boundaries between mother and child - and in this regard, the formation of attachment after childbirth is based on their greater separation than in the prenatal period. nine0008

nine0008

What has been said above about the role of bodily sensations of pregnant women in the development of attachment still does not fully explain why the violation of attachment formation so significantly distorts the sensitivity of pregnant women. This phenomenon can perhaps be explained only by the fact that the quality of women's bodily sensations depends on the woman's emotional mood for pregnancy and upcoming motherhood. The psychophysiological basis for such a hypothesis is the long-established fact that the quality and modality of our sensations depend not only on the state of the peripheral (receptor) part of the analyzer, but are also deeply connected with the functional state of the thalamus, the entire limbic complex, and most importantly with the state of the higher cortical links of the analyzer. Apparently, a normal pregnancy corresponds to a well-defined and socially expected emotional complex that supports the characteristic modality of bodily sensations. On the contrary, distortions in the emotional sphere of pregnant women (regardless of the nature of these disorders) lead to changes in the quality of the tangible component of pregnant women's experiences. nine0008

nine0008

It is important to emphasize that the ambivalent nature of the bodily experiences of pregnant women under normal conditions corresponds, as can be seen from our observations, to a kind of ambivalent emotional complex of pregnant women, noted earlier (M.D. Marcone, 1993, D. Pines, 1972, S. Lebovici, 1988 , C. Bonnet, 1992, Savatier S. 1992). From the point of view of Brun A.E. (1994) "binary" affects correspond to special, "alternative" states of human consciousness. From his point of view, the psychological meaning of the latter is that this state facilitates the process of assimilation and internalization of information. If we accept such a hypothesis, then we can assume the existence of an alternative state of consciousness during pregnancy. Such a state apparently facilitates the process of "creativity" over the images of future motherhood - the restructuring of the pregnant woman's self-awareness, and therefore creates the best conditions for the appearance of the main neoplasm of the pregnancy period - a deep vital-protopathic attachment of mother and child. It can be assumed that the alternative state of consciousness in puerperas also has an evolutionary-adaptive meaning. We see it not so much in imprinting the moment of childbirth in the memory, but in its opposite - the hypomnesia of all the negative aspects of the birth act that quickly follows this, thereby preparing the woman for new cycles of motherhood. It can be assumed that in women carrying an unwanted pregnancy, due to the monopolarity of affect - its shift towards negative experiences, the "special state of consciousness" characteristic of pregnant women is not formed. This leads to the fact that the "image of the child" is not only not internalized, but, on the contrary, is psychologically rejected. nine0008

It can be assumed that the alternative state of consciousness in puerperas also has an evolutionary-adaptive meaning. We see it not so much in imprinting the moment of childbirth in the memory, but in its opposite - the hypomnesia of all the negative aspects of the birth act that quickly follows this, thereby preparing the woman for new cycles of motherhood. It can be assumed that in women carrying an unwanted pregnancy, due to the monopolarity of affect - its shift towards negative experiences, the "special state of consciousness" characteristic of pregnant women is not formed. This leads to the fact that the "image of the child" is not only not internalized, but, on the contrary, is psychologically rejected. nine0008

Thus, the maternal feeling of attachment to the child is formed during pregnancy, also due to new bodily experience. The body-emotional complex of pregnant women is extremely specific. As we see it, it participates in the formation of attachment not only as a factor stimulating the appearance of certain fantasies of expectant mothers, as psychoanalytically oriented researchers believe, but is also directly related to the deeper, vital, physiological aspects of this feeling. nine0008

nine0008

REFERENCES

1. Vygotsky L.S. Psychology of Art. M, 1987, 343 p.

2. Kopyl O.A., Baz L.L., Bazhenova O.V. // Synapse, 1993, 4, pp. 35–42.

3. Lorenz K. Aggression. M, 1994, pp. 120–123.

4. Marcone M.D. Nine months sleep. Dreams during pregnancy., M, 1993, 111 p.

5. Savatier S. Gestalt is a baby / / Ed. Moscow Gestalt Institute. M, 1982, 75 p.

6. Shmurak Yu.I. Prenatal community // Man. 1994.

7. Ainsworth M.D., Boulby J. An ethological approach to personality development// Amer.Psychol, 1991, V 46, pp 331–341.

8. Bonnet K. Geste d'amour, Paris, 1992, 350 rub.

9. Bowlby J. Child care and the grouth of love. Abridger and editor by Frym-London. Tonbridge. 1957.

10. Engen T. et al, Decrement and recovery of responses to olfactory stimule in the human neonate// J. of Comparative Physiology and Psychology, 1965, 59, p 312–316.

11. Kreisler L. L'enfant du desordre psychosomatique, Toulouse, Private, 1981.

12. Kreisler L. Le nouvel enfants du desordre, Toulouse, Private, 1987.

13. Lebovici S. Interaction fantasmatique, transmission intergenerationnelle // Psychiatrie du bebe, Paris, 1988, p 321–335.

14. Montagner H. L' attachment - le debut de la tendresse, 1990, 369 rubles.

15. Montagner H. et al. Les activites ludiques du jeune enfant// L'education nouvelle, n hors serie, 1974, p 15–44.

16. Pemberthorn, D.A., Bendy, D.K. // Brit J Psichiatry, 1973, V 123. - P. 575-578.

17. Pines D. Pregnancy and motherhood: interaction between fantasy and reality. // Br. J.med psychol,1972, v 45, p. 333–343.

18. Spits R. De la naissance a la parole, Paris, PUF, 1968.

19. Steiner J., Human facial expression in response to taste smell stimulations, N-Y, Academic Press, 1979, 13, p 257–295.

20. Stern D. The ferst relationship: Infant and mother., Cambridge, Harvard university Press, 1977. other manifestations of parental intimacy for children are as important as food and sleep. With the permission of the Mann, Ivanov and Ferber publishing house, we publish an excerpt from the book “In Search of Motherly Love” by Kelly McDaniel - about how the attunement of mother and child is formed at the level of neural connections

With the permission of the Mann, Ivanov and Ferber publishing house, we publish an excerpt from the book “In Search of Motherly Love” by Kelly McDaniel - about how the attunement of mother and child is formed at the level of neural connections

“It was customary among the women in my family to bring up children in the best possible way, and, like many, I had a heavy burden of the past. I had white skin, a quality education and other privileges, but even such an exemplary life could not get rid of the longing for motherly love, which I call motherly hunger, ”Kelly McDaniel writes at the beginning of her book “In Search of Motherly Love . How can an adult daughter heal from the traumas of the past and improve relationships with others and with herself. The origins of this hunger for maternal warmth and the trauma that daughters transmit to future generations, the author sees in the violation of attachment, the importance of which was underestimated for a long time. About how it is formed - this passage. nine0004

About how it is formed - this passage. nine0004

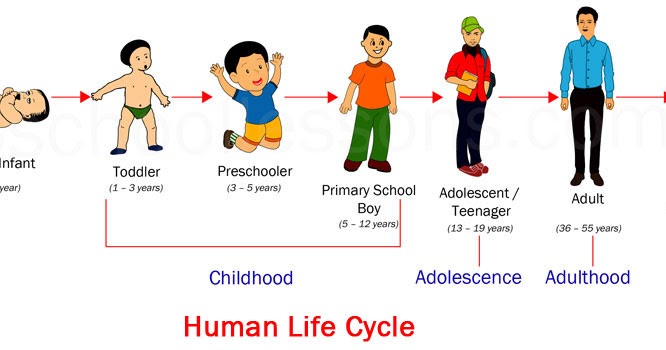

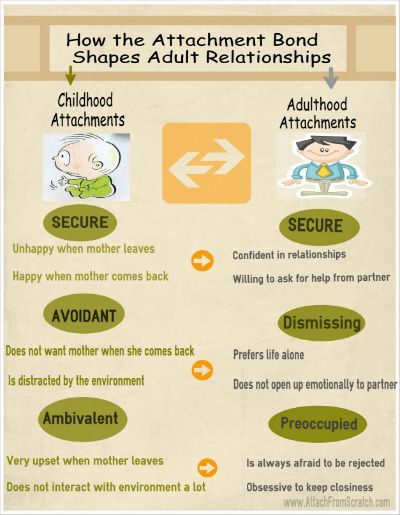

Attachment Theory

This theory was born after World War II. At that time, the British psychiatrist and psychoanalyst John Bowlby worked in orphanages. He noticed that children who had shelter, food and medical care did not prosper at all - on the contrary, many of them died. Bowlby began to look for the causes of this phenomenon. Later his work was continued by Mary Ainsworth. The results of their research have been repeatedly tested in practice in different countries of the world. Bowlby's Attachment Theory brings us back to a fundamental truth: Infants are inherently dependent on the care of their caregiver, it is built in by nature. Babies are true masters of affection. Their biology suggests that the parent is nearby. If an infant or child is unhappy, this does not mean that the problem is in him. Probably, his condition indicates a lack of something important in the atmosphere of caring for him. nine0008

nine0008

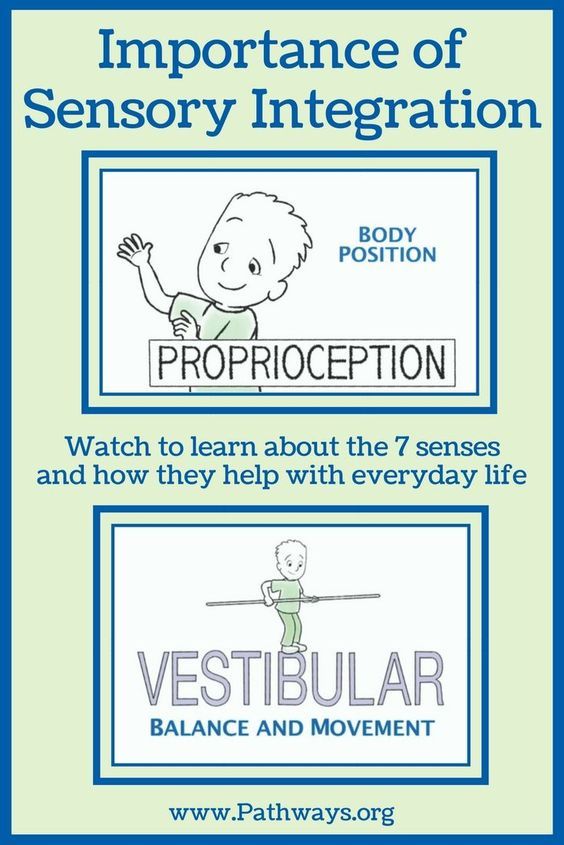

Infants need proteins and fats to develop their body systems. And in the same way, to strengthen the areas of the brain responsible for social functions, he needs maternal warmth. Hugs stimulate newborn brain growth. The same function is performed by hundreds of small touches when the mother changes his diapers, feeds him and carries him in her arms. Every moment potentially creates a conviction that people are fun and the world is a benevolent and safe environment. The soothing, responsive touch of mother to child stimulates the internal reinforcement system in the infant's brain, activating dopamine, serotonin and other neurotransmitters that color life with joyful colors. The more cozy hugs in a child's life, the more receptive his brain becomes to love and other happy experiences. During the first eighteen months of a baby's life, fast-growing sensory neurons are constantly learning through contact with the mother. nine0008

nine0008

Healthy mothering contributes to the development of the right hemisphere. The right hemisphere is the future seat of sanity, the ability to understand the hints of other people and empathy for the feelings of others. Its growth depends on predictable and sensitive moments of affection. Dr. Allan Shor, professor of interpersonal neuroscience at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, calls this phenomenon a "feeling process." Maternal love is the basis here, based on which the brain either completely trusts people, or does not trust them at all. nine0008

Related material

How we learn attachment

The primitive experience of loving touch and safe sounds is stored in the body's implicit memory. Implicit, or bodily, memory accumulates information about the world and the family before the development of explicit, that is, conscious, memory. Explicit memory makes it possible to recall events that happened yesterday, last year, or the night before. The principles of implicit memory were developed by psychologists Peter Graf and Daniel Schacter. They explain why we respond to early childhood experiences even though we have no conscious memory of them. Our cells have memories of the very first sensations, even if a very long time has passed since then. However, it is impossible to recall them in memory. nine0008

Explicit memory makes it possible to recall events that happened yesterday, last year, or the night before. The principles of implicit memory were developed by psychologists Peter Graf and Daniel Schacter. They explain why we respond to early childhood experiences even though we have no conscious memory of them. Our cells have memories of the very first sensations, even if a very long time has passed since then. However, it is impossible to recall them in memory. nine0008

Some parts of the limbic brain, especially the amygdala involved in the formation of emotions, function from the moment of birth. That is why primitive, that is, primary, interaction with people is extremely important for newborns. Impressions of the environment (safety, belonging, joy, stress) are stored in implicit memory. It is a primitive part of innate intelligence that teaches us security, love, and helps us perceive reality even before the appearance of higher brain centers in the neocortex (or neocortex, which makes up most of the cerebral hemispheres). From the last trimester of pregnancy until the age of two, the brain doubles in size. During such a rapid growth, the emotional regulation of the baby directly depends on the parent: an adult relieves stress, gives a sense of security and teaches you to trust communication with a person, since the child cannot yet “think” on his own. In other words, the baby needs a caring person who, through sounds, touches and just being nearby, translates love into an emotional language that the baby understands. nine0008

From the last trimester of pregnancy until the age of two, the brain doubles in size. During such a rapid growth, the emotional regulation of the baby directly depends on the parent: an adult relieves stress, gives a sense of security and teaches you to trust communication with a person, since the child cannot yet “think” on his own. In other words, the baby needs a caring person who, through sounds, touches and just being nearby, translates love into an emotional language that the baby understands. nine0008

Science has proven that babies cannot think like children and adults. Knowing this, it hurts to hear so many ill-informed parenting experts claim that babies are good at manipulating loved ones. The ability to manipulate people is a product of higher mental activity, to which the baby will grow up only after a few years. If the baby cries and screams, he is not trying to control adults for his own purposes. So he reports a state of stress and asks for help. Young children do not know how to regulate emotions on their own - they learn to regulate based on the care they receive. nine0008

Young children do not know how to regulate emotions on their own - they learn to regulate based on the care they receive. nine0008

It can be said that a baby and mother have one brain for two, until the child develops the areas of the brain responsible for cognitive functions: logic and rational thinking. Physical closeness and gentle interaction with the mother or other primary caregiver supports the biological processes that promote optimal brain development. When the hemispheres work together, learning and managing emotions are easy. Both of these skills are entirely dependent on tutelage and protection in early childhood, which puts the mother in the position of the chief architect of the infant's brain. I myself did not fully realize the importance of the mother's presence when I was a young mother. There was nowhere to get this information, and, of course, I did not know what could not be read. nine0008

Related material

Attachment patterns

The feeling of close connection during early development is imprinted in implicit memory. And implicit memory shapes our unique attachment seeking patterns. In this sense, the body and brain govern our lives from day to day, whether we realize it or not. The lack of awareness and the inability to address early experiences explain why we often think that everyone is socializing, making strong bonds, playing or working just like ourselves. We don't understand that attachment types and behavior patterns are unique; we do not understand until we come into conflict with a loved one. Disagreements provide an opportunity to learn new things about how we make connections, what we need, and how others interpret our behavior. However, many neglect the opportunity to learn this lesson from the conflict because they do not have the tools to understand their own resentment or desperate jealousy. We just don't understand why we feel the way we do. nine0008

And implicit memory shapes our unique attachment seeking patterns. In this sense, the body and brain govern our lives from day to day, whether we realize it or not. The lack of awareness and the inability to address early experiences explain why we often think that everyone is socializing, making strong bonds, playing or working just like ourselves. We don't understand that attachment types and behavior patterns are unique; we do not understand until we come into conflict with a loved one. Disagreements provide an opportunity to learn new things about how we make connections, what we need, and how others interpret our behavior. However, many neglect the opportunity to learn this lesson from the conflict because they do not have the tools to understand their own resentment or desperate jealousy. We just don't understand why we feel the way we do. nine0008

The brain regions responsible for cognitive functions do not have a key (explicit memory) to the early stage of personality formation (implicit memory). When we get the right idea of the sensations in the body and pay attention to feelings, we are able to better control the selection process and our behavior. This can only be learned over time, because without an explicit memory of the first months of life, we are not able to form a complete picture of how we comprehended love and affection. But rest assured, as you learn more about the essential components of mothering—attunement and mirroring—your body and mind will begin to realize what they missed during the first years of development. nine0008

When we get the right idea of the sensations in the body and pay attention to feelings, we are able to better control the selection process and our behavior. This can only be learned over time, because without an explicit memory of the first months of life, we are not able to form a complete picture of how we comprehended love and affection. But rest assured, as you learn more about the essential components of mothering—attunement and mirroring—your body and mind will begin to realize what they missed during the first years of development. nine0008

While these discoveries may cause intense feelings, discomfort, and shock, they will actually prepare you for healing and transformation.

Related material

Attunement

When someone or something is important to you, they absorb all your attention. With attention, you show appreciation, love, and respect. Attention that requires both physical and emotional presence is attunement. Being attuned to your favorite activity, teacher, or friend is a demonstration of what is important to you. Attunement is the full expression of your personality. nine0008

With attention, you show appreciation, love, and respect. Attention that requires both physical and emotional presence is attunement. Being attuned to your favorite activity, teacher, or friend is a demonstration of what is important to you. Attunement is the full expression of your personality. nine0008

Children who are in an attuned relationship with a parent or caregiver during their first three years of life are better able to manage their emotions as they grow older. In this case, the researchers talk about secure attachment. These kids have happy brains. This does not mean that they are in a state of continuous happiness, just that their brains are functioning correctly.

Attunement is the language of motherly love. Through eye contact, sounds and touch, the mother teaches the child how love feels. The baby loves the face of his mother. He doesn't care if she is smart or beautiful - he wants her to always be there. Even if the baby cannot yet focus on the individual details of her facial expressions, he still feels attuned. Neuroscientist Edward Tronic, Ph.D. in Psychology, has conducted a number of practical studies to demonstrate maternal attunement with the child. In his landmark Stone Face experiment, mothers initially interacted with babies in the usual way. From the side it was clear how good they were with each other. They made gentle sounds, gesticulated, and maintained eye contact. After a few minutes, the mothers were asked to stop communicating with the children, but to remain close, keeping a frozen expression on their faces without any facial expressions. nine0008

Even if the baby cannot yet focus on the individual details of her facial expressions, he still feels attuned. Neuroscientist Edward Tronic, Ph.D. in Psychology, has conducted a number of practical studies to demonstrate maternal attunement with the child. In his landmark Stone Face experiment, mothers initially interacted with babies in the usual way. From the side it was clear how good they were with each other. They made gentle sounds, gesticulated, and maintained eye contact. After a few minutes, the mothers were asked to stop communicating with the children, but to remain close, keeping a frozen expression on their faces without any facial expressions. nine0008

The women suddenly stopped smiling and fell silent. Moments later, next to unresponsive, emotionless mothers, babies who had just looked happy began to experience confusion and stress. The children screamed in protest and tried their best to regain their mother's attention. Without exception, all the children tirelessly tried to resume communication, although the faces of their mothers remained indifferent. This is extremely difficult to watch, because children are undoubtedly suffering. They seem to be screaming, “What happened? Where are you going? What's wrong? I need you!" It is hard for a child to endure an indifferent, out of tune mother. Physical intimacy alone is not enough - it must be supplemented with an emotional connection. nine0008

Without exception, all the children tirelessly tried to resume communication, although the faces of their mothers remained indifferent. This is extremely difficult to watch, because children are undoubtedly suffering. They seem to be screaming, “What happened? Where are you going? What's wrong? I need you!" It is hard for a child to endure an indifferent, out of tune mother. Physical intimacy alone is not enough - it must be supplemented with an emotional connection. nine0008

Fortunately, the experiment ended very quickly (otherwise it would have been inhumane). Mothers immediately consoled the children: they took them in their arms, soothed them, smiled and cooed gently with them. A live demonstration of mother-infant communication shows the enormous power of affectionate, warm attunement. From these first lessons in relationship development, the building of a secure attachment is built. It is based on a sense of self-worth, which will develop in the future.

In addition to maternal attunement, we see how resilient and adaptive the infants behaved during the experiment. With the resumption of affectionate, soothing interaction, they quickly recovered from stress. No mother can constantly maintain perfect attunement with her child. Moreover, this is not necessary. But sensitive mothers do not allow babies to suffer too long and often. Just like the mothers in Tronic's experiment, they come to the rescue just in time when babies lose their sense of attachment. nine0008

Two-way communication between mother and baby builds the trusting and secure attachment needed for proper brain development. Modern studies have shown that by the third month of life, the girl completely adopts the facial expressions of her mother and the sounds she makes. Beatrice Beebe, Ph.D., professor of clinical psychology at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and expert in mother-infant communication, writes that baby girls cannot reproduce facial expressions that mothers do not have.