How to train autism child

Seven toilet training tips that help nonverbal kids with autism

February 12, 2016

Today’s “Got Questions?” answer is by psychologists Courtney Aponte and Daniel Mruzek, of the University of Rochester Medical Center, one of 14 sites in the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network.

“We're looking for help toilet training our 7 year old. He is very limited verbally.”

Great question! Many children with autism take longer than is typical to learn how to use the toilet. This delay can stem from a variety of reasons.

- Many children with autism have a general developmental delay. That is, they simply learn new skills more slowly than other children do.

- Many children who have autism have great difficulty breaking long-established routines – in this case using a diaper. Plus, there are relatively few opportunities to practice toileting during the day, as there are only so many times a child genuinely needs “to go.

”

- Communication challenges – such as your son’s limited verbal abilities – clearly add to the challenge for many children on the autism spectrum.

- It’s also common for children with autism to develop anxiety around toileting.

For example, some children with communication challenges won’t understand the question – “Do you need to you use the bathroom now?” Or they may not know how to respond to it or otherwise signal that they need to use the toilet.

Even nonverbal communication can be a challenge among children with autism. In our practices, many parents tell us that their children don’t show the usual signs of an impending accident. For example, crossing their legs, grabbing themselves or even the classic “potty dance.” In other words, these children seem to “go without warning,” making it more difficult for the caregiver to get the child to the toilet in time.

The good news is that we’ve found a number of strategies that help children with autism overcome their toilet training challenges. Before we delve into them, we want to remind you of a very helpful resource and reference:

Before we delve into them, we want to remind you of a very helpful resource and reference:

Download the Autism Speaks ATN/AIR-P Toilet Training Tool Kit.

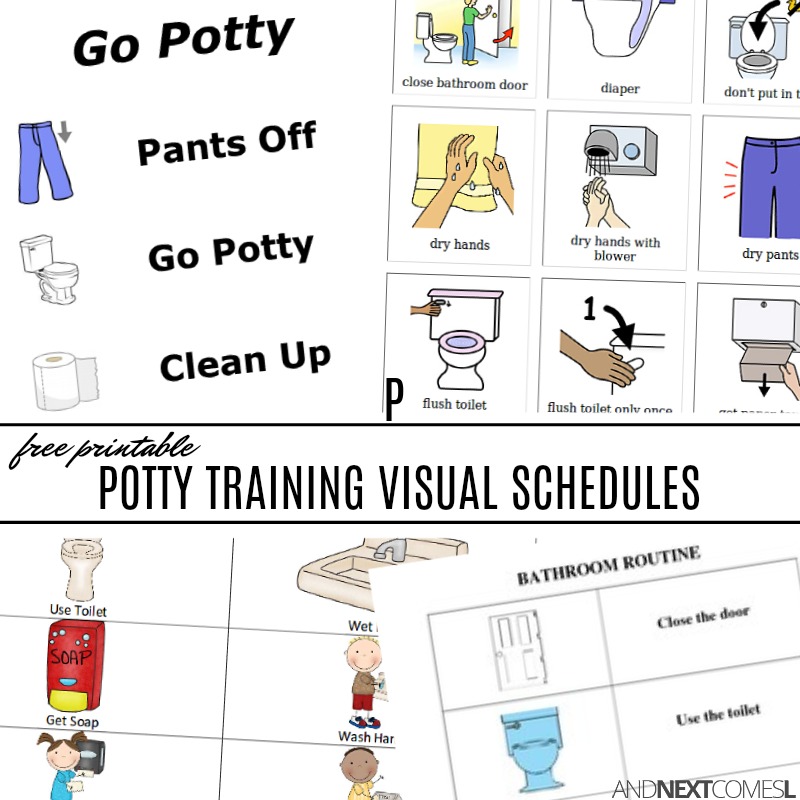

- When it comes to communication: less is more! Use clear and simple pictures or visual prompts such as the visual support below from the Autism Speaks tool kit.

-

Use the visual prompt with simple and direct language to help your child understand what is expected. For example, say “Time for potty” instead of asking “Do you need to use the potty now?”

We’ve found it most effective when parents simultaneously present the verbal direction with the visual support while immediately guiding the child to the toilet with little or no additional discussion.

-

- Don’t delay the underwear! Move your child into underwear as soon as possible. We realize that this seems an intimidating step for many parents. But we’ve found it’s really important.

Let’s face it, modern diapers and pull-ups can be too good at whisking away the pee. As a result, your child may not even realize that he has urinated. Putting your child in underwear helps him associate accidents with the discomfort of wetness on his skin.

Let’s face it, modern diapers and pull-ups can be too good at whisking away the pee. As a result, your child may not even realize that he has urinated. Putting your child in underwear helps him associate accidents with the discomfort of wetness on his skin. - Don’t fuss over accidents. When your child does have an accident, minimize discussing, cajoling, pleading, teasing or other fussing that can have the unintended result of reinforcing the accident behavior. Instead, provide a brief reminder that you expect your child to use the toilet next time he needs to go. Then complete the cleanup with as little fanfare and discussion as possible. Save your attention for when your child is using – or attempting to use – the toilet.

- Reward the desired behaviors. Identify some activities, toys or small treats that will motivate your child. Reserve these for rewarding your child’s toileting successes, and only for rewarding toileting success.

Chances are your child will work harder at achieving success if he can’t get these items any other way.

Chances are your child will work harder at achieving success if he can’t get these items any other way. -

Importantly, deliver the rewards as soon as possible after your child uses the toilet to pee or poop. Don’t wait! We’ve found that quick delivery of the reward tends to speed skill acquisition.

And remember those visual supports. For example, you can incorporate a picture of the reward in your child’s toileting visual schedule. OR use a “First-Then” board to illustrate “First use the toilet, and then get your reward.” (See example below.)

In the early stages of training, reward each small success – even a small dribble of urine. These are important behaviors that you can build upon during subsequent bathroom trips.

-

- Use rewards to communicate. Sometimes, rewards can help you communicate your expectations to your child. This is especially important for children who have difficulty understanding “if, then” rules.

-

For example, your child may not understand, “If you pee in the potty, you can have 5 minutes of iPad.” He may do better if you increase the opportunities for success and reward. How? Try the following:

1. On a day you are both at home, increase the fluids he drinks. This will give you more chances to take him to the bathroom for a successful pee. Reward each tinkle!

2. Look for patterns in when your child has accidents. It can help to write down the time and place of each accident for several days. You may start to see a pattern emerge. For example, you may find that he often urinates around 30 minutes after drinking a glass of water, milk or other beverage. Use this information to schedule his bathroom trips around times he seems most likely to pee.

3. Remember to make those rewards immediate and consistent. This increases the chances that your child makes the connection between peeing and receiving his reward.

-

- Empower your child to communicate.

It’s especially important to help children with limited verbal abilities to signal their need to use the toilet. Once your child is consistently using the toilet when you bring him to the bathroom, it’s time to teach him a simple way to tell you he needs “to go.”

It’s especially important to help children with limited verbal abilities to signal their need to use the toilet. Once your child is consistently using the toilet when you bring him to the bathroom, it’s time to teach him a simple way to tell you he needs “to go.” -

Consider encouraging him to use a visual support such as a picture of a toilet. Consider clipping it to his belt loop or shirt button hole so he can easily point to it. Or, if your child uses an assisted communication device, you can incorporate a picture of a toilet that he can press to give you an audible cue.

Ideally, you want him to use these cues when he feels his bladder is full. It can help to slowly stretch out how often you take him to the bathroom unprompted. In other words, you need to give him the chance to recognize what a full bladder feels like – and then experience the relief of peeing in the toilet. As we all know, that relieved feeling can be its own “natural” reward for using the toilet.

As your child becomes increasingly attuned to when his bladder and bowel is full, he may begin to show more obvious signs of a full bladder. You may start to see an increase in rocking, holding oneself, more vocalizations or other signs that he’s ready for a trip to the bathroom.

Sometimes a child may simply look intently at you – or toward the bathroom – when he or she needs to go. It’s particularly helpful for parents, teachers and other caregivers to become sensitive to these “tells” and immediately encourage the child to use the chosen communication method. This can be with whatever method works best – e.g., handing you the toilet picture or pressing the toilet button on a speech device.

Definitely reward your child for any effort to communicate.

-

- If needed, get professional help. As parents, we often benefit from an expert eye and fresh perspective in what can be a challenging experience for many.

We wish you and your son all the best, and we appreciate your great question!

Editor’s note: The following information is not meant to diagnose or treat and should not take the place of personal consultation, as appropriate, with a qualified healthcare professional and/or behavioral therapist.

Blog

Catching up with Scarlett: Autistic second grader and her super mom thrive in 2022

Roadmap

Clinician Guide: Program Development and Best Practices for Treating Severe Behaviors in Autism

Science News

Study reveals long-term language benefits of early intensive behavioral intervention for autism

News

Join Us for a Brighter Life on the Spectrum

Podcast

Autism POVs: What does it mean to be nonverbal?

News

Autism Speaks and Royal Arch Masons expand funding for auditory-processing research

Expert Opinion

My child is nonverbal. Anything new that might help him communicate better?

Expert Opinion

How does sensory processing affect communication in kids with autism?

Social stories and autism | Raising Children Network

What are social stories?

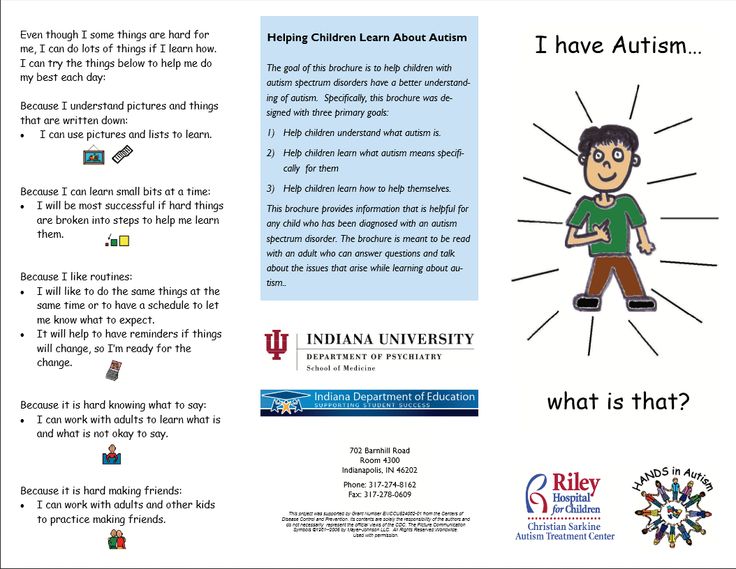

Social stories explain social situations to autistic children and help them learn ways of behaving in these situations. These stories are sometimes called social scripts, social narratives or story-based interventions.

These stories are sometimes called social scripts, social narratives or story-based interventions.

Social Story™ and Social Stories™ are trademarks originated and owned by Carol Gray.

Who are social stories for?

Social stories were initially developed for use with autistic children. They’re also sometimes used to help other children with learning or intellectual disorders.

Social stories might be less effective for children with poor comprehension skills, and they might not be suitable for non-verbal children.

What are social stories used for?

Social stories can help autistic children learn about social behaviour in specific settings like the supermarket, doctor’s surgery, playground and so on. You can create a social story for almost any social situation.

Social stories are used together with other therapies.

Where do social stories come from?

Social stories were developed in 1991 by Carol Gray, a teacher working with young autistic children.

What is the idea behind social stories?

Autistic people often misunderstand or don’t pick up on social cues that other people notice – for example, body language, facial expressions, gestures and eye contact.

Social stories were developed to help autistic children learn ways of behaving in social settings. Social stories do this by explicitly pointing out:

- details about the setting

- things that typically happen in that setting

- the actions or behaviour that are typically expected from children in the setting.

This can help children pick up on cues they normally wouldn’t notice and learn how to respond to these cues. It might also help children learn new skills for social situations.

What do social stories involve?

First, a psychologist or speech pathologist assesses an individual child to identify key areas of concern.

Next the therapist writes a social story based on a particular area or situation of concern. The tailor-made story is written in the first or third person and can be written in the past, present or future tense – for example, ‘I go to the shop’ or ‘We will sit in the waiting room’. The story is written using language to match the age and skill of the child. The story can be a print book or an ebook. It can include photos or illustrations.

The tailor-made story is written in the first or third person and can be written in the past, present or future tense – for example, ‘I go to the shop’ or ‘We will sit in the waiting room’. The story is written using language to match the age and skill of the child. The story can be a print book or an ebook. It can include photos or illustrations.

When a social story is ready, an adult reads the story with the child to ensure the child can understand it. Typically, the stories are read just before the event they describe. For example, each morning a parent and child might read a story about what to do in the school playground, and the teacher might also read the story with the child just before the child goes out to play.

Parents and teachers help the child practise by reminding the child of the story’s key points. For example, ‘What does the story tell us to do?’

Once the child understands the social situation, children can read the story less often and it can be gradually phased out.

Children can experience social stories in different ways, depending on their capabilities. For example, if children aren’t yet reading, you can read stories to them or record stories and play the recordings as children read along.

Social stories involve daily use to start with. Gradually, this approach takes less time as children learn new behaviour. Because this is a preventative approach, the key thing to think about is when you use the stories, rather than how long you use them for.

Do social stories help autistic children?

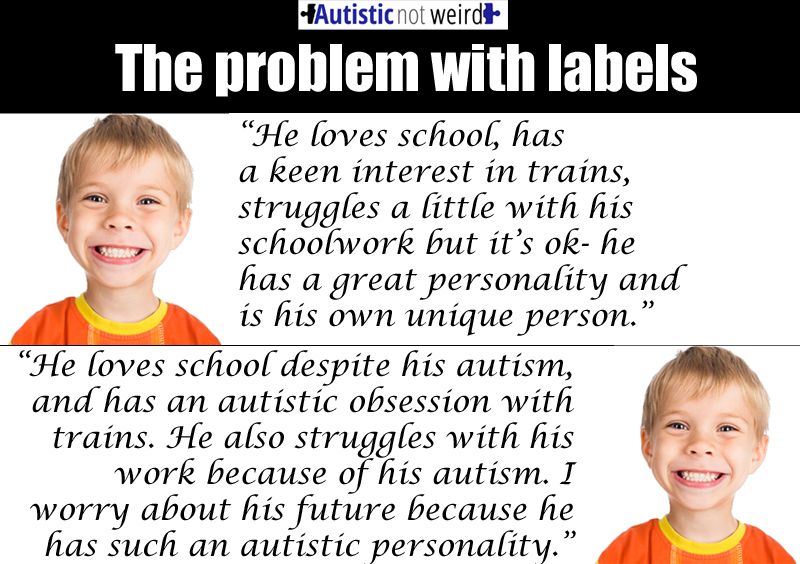

Research shows that social stories can have positive effects on the behaviour of autistic children. Research also suggests that they might be more effective at helping children manage their behaviour than helping them learn particular social skills.

For social stories to work, it’s important that the stories are highly individualised to each child’s needs and that they’re used at the right time for individual children.

Who practises this method?

You can read Carol Gray’s The new Social Story™ book or use online resources to learn how to write social stories.

Professionals like psychologists and speech pathologists can teach you how to write social stories for your child. They can also advise you on the best way to deliver the stories – for example, by reading them aloud, making videos or having your child read them.

Where can you find a practitioner?

Some psychologists and speech pathologists who work with children have experience writing and using social stories. You can find these professionals by going to:

- Australian Psychological Society – Find a psychologist

- Speech Pathology Australia – Find a speech pathologist.

You could also talk about this therapy with your NDIA planner, early childhood partner or local area coordinator (LAC), if you have one.

Parent education, training, support and involvement

If your child is using social stories, you’re usually directly involved in reading the stories to your child. You might also need to remind your child to use new skills in social situations, and you’re responsible for rewarding your child for putting the new skills into practice.

You might also need to remind your child to use new skills in social situations, and you’re responsible for rewarding your child for putting the new skills into practice.

You can also create your own social stories.

Cost considerations

Anyone who’s trained can write social stories, so the cost can be quite low. You can even create your own social stories.

The costs of seeing therapists like speech pathologists to get help with developing social stories might be covered for up to 20 sessions by Medicare. Whether the cost is covered depends on the professional providing the consultation.

Some private health care funds might cover a portion of the consultation fee. This can be claimed immediately if the provider has HICAPS.

You can contact the NDIS to find out whether you can include the cost of using social stories in children’s NDIS plans.

Therapies and supports for autistic children range from behaviour therapies and developmental approaches to medicines and alternative therapies. When you understand the main types of therapies and supports for autistic children, it’ll be easier to work out the approach that will best suit your child.

When you understand the main types of therapies and supports for autistic children, it’ll be easier to work out the approach that will best suit your child.

Ten exercises for the development of gross motor skills in autistic children. ~ Autism | ABA

09:32 unknown No comments

We bring to your attention ten exercises for the development of gross motor skills in autistic children. With the help of these exercises, you can not only strengthen the muscles of the child, but also form very valuable skills in him. Parents and professionals working on the development of the motor skills of an autistic child have a wide range of different techniques and techniques. Some of these activities can be quite difficult for autistic children, while others will turn into real fun.

The ten activities for developing autistic children's gross motor skills in this article include activities that not only develop the child's motor skills, but also improve their social skills.

1. March

March is a simple gross motor activity that can also develop a number of other skills. The task is that the adult takes a marching step forward, and the child imitates his action. Invite the child to start by moving the legs in place, and then gradually move to the steps forward and to the movements of the hands.

2. Trampolining

The trampoline is the king of gross motor skills for children with autism. The bouncing motion is an excellent sensory stimulation that can be very helpful in relieving sensory overload and anxiety. A number of autistic children experience less intense repetitive behavior after trampolining, and such activity helps some children to calm down and organize their behavior.

3. Ball games

The simplest activities can be a source of great pleasure for a child, and one of these activities is the ball game. Catch the ball may not seem like the most realistic goal to start with, but it can be done gradually. Start by simply rolling the ball back and forth. This simple activity develops important visual tracking skills as well as fine motor skills as the child follows the movement of the ball. Other activities include:

Start by simply rolling the ball back and forth. This simple activity develops important visual tracking skills as well as fine motor skills as the child follows the movement of the ball. Other activities include:

• Kicking the ball

• Dribbling

• Hitting the ball off the floor

• Hitting and catching the ball

• T-ball (baseball hit)

4. Balance

balance is often a very difficult task, while many gross motor skills require the child to have a good sense of balance. Do a test to see if the child can stand still with their eyes closed and not lose their balance. This will help you determine how much balance you need to work on. You can start by moving the child along a thin line, and then gradually move on to balancing on a special swing.

5. Bicycles and tricycles

Bicycles for autistic children do not have to be specifically designed to meet the needs of children with autism spectrum disorders, but some of these adapted models have additional benefits. Bicycles and tricycles help develop not only a sense of balance, but also strengthen the muscles of the child's legs. The task involves the ability to ride a bicycle, concentrating on the direction of its movement, which can be quite a challenge for many children.

Bicycles and tricycles help develop not only a sense of balance, but also strengthen the muscles of the child's legs. The task involves the ability to ride a bicycle, concentrating on the direction of its movement, which can be quite a challenge for many children.

6. Dancing

The New York Times magazine published an article titled "Dancing Helps Autistic Children" in which the authors talked about the importance of entertaining and fun motor activity for the development of a child. Parents and therapists can use dancing to music to encourage motor imitation skills and other daily life skills. Ideas for dance activities include cleaning, brushing your teeth, freezing games, and more.

7. Symbolic play

Symbolic play is often a problem for autistic children. Many of them will find it easier to work on their imagination if such games involve physical activity. Here are some ideas for symbolic games to develop motor skills:

• “Flying like a plane”

• “Jumping like a rabbit”

• “Dressing up”

8. Steps in the box

Steps in the box

When it comes to choosing different fun activities for children , professionals and parents, such a simple item as an ordinary cardboard box often helps out. To begin, encourage your child to step into the box and then step out of the box again. Gradually complicate this task by coming up with sequences of steps or using deeper boxes.

9. Tunnel

Tunnel crawling is often an incredibly fun activity for a child who is simultaneously training their motor skills and developing a sense of the permanence and stability of objects. Social skills can also be incorporated into this activity, using games such as hide-and-seek, finding hidden things, and symbolic games.

It is not necessary to buy a special tunnel for the child to enjoy this activity. You can line up large cardboard boxes or build a tunnel of chairs and blankets. Tunnel games can be transformed into many other activities ranging from train games to imaginary camping.

10. Obstacle course

Obstacle course is a unique set of exercises for developing gross motor skills. A cross does not have to be difficult in order to be effective. In fact, therapists and parents can start with a cross-country run that consists of just one obstacle and gradually build on it with different exercises. The simplest obstacle course ideas include:

• Crab walk

• Frog Jumping

• Rolling

• Rope Jumping

• Line Walking

• Climbing etc.

The obstacle course is a great opportunity to use a variety of gross motor exercises, and can also be used for sequencing activities with autistic children. This kind of physical activity is a great way to achieve instructional learning goals.

Development of a plan for the development of gross motor skills

Physical activity can be a source of anxiety for many children with autism spectrum disorders (we recommend that you also read the article on managing anxiety). Give your child support and introduce new types of exercise gradually. Start with the most neutral tasks and then move on to the more difficult ones, making sure that the activities you suggest are appropriate for the child's developmental level and that the motor development goals are realistic.

Give your child support and introduce new types of exercise gradually. Start with the most neutral tasks and then move on to the more difficult ones, making sure that the activities you suggest are appropriate for the child's developmental level and that the motor development goals are realistic.

Source: http://autism.lovetoknow.com/Ten_Gross_Motor_Activities_for_Autistic_Children

Posted in: Child Development

Next Previous Main page

How does exercise affect people with autism?

08/05/18

Scientific evidence and recommendations for physical activity in children and adults with autism

Author: Sean Healy

Source: Autism Speaks

The phrase “sport is the best medicine” has become the refrain of many fitness and health experts. This saying is supported by many studies. And there is now enough research in children and adolescents with autism to be able to say with certainty that physical activity has a range of benefits for autism.

Recently, my colleagues and I published a meta-analysis of 29 studies on the effects of exercise on children and adolescents with autism. In total, more than 1,000 people on the autism spectrum participated in these studies. In a meta-analysis, we were able to combine data from different studies and thus understand that exercise could indeed be one of the interventions for autism.

Overall, we found that physical activity programs for young people with autism had modest to significant effects in a number of important areas. For example, they improve motor skills, physical skills, social interaction, muscle strength, and endurance. I will describe these benefits in more detail below, and end with a few strategies to encourage young people with autism to engage in regular physical activity.

Exercise and autism: different benefits

Social skills: Our meta-analysis found that young people who participated in physical activity programs specifically for people with autism had significant improvements in social and communication skills. These programs included horseback riding, various group sports, running programs, or video games involving physical activity.

These programs included horseback riding, various group sports, running programs, or video games involving physical activity.

Researchers have tried to explain how physical activity can improve social skills. When properly planned, a physical activity program creates a fun, safe space in which to socialize with other children. In other words, this is a great opportunity to practice social skills. In addition, programs that include animals (such as horseback riding) allow children to interact non-verbally with someone.

Fitness: It may come as no surprise that our analysis confirmed that children and adolescents with autism improve muscle strength and endurance when they participate in programs such as water exercise, horseback riding, or video games with physical activity. activity. This is especially important for children with autism, as previous studies have shown that those with autism may have significantly lower muscle strength and endurance than their non-autistic peers.

Muscle strength and endurance are important for more than just fitness. They allow children with autism to take advantage of opportunities to socialize with peers that require physical activity, such as participating in sports or simply playing games.

Physical skills: Many people with autism have significantly lower levels of physical skills than other people. Such skills include balance, body coordination, hand-eye control, and others. We recommend providing children with autism with different types of physical activity to improve various physical skills. This could include physical activity video games, trampolining (with safety precautions), table tennis, or horseback riding.

Motor Skills: Many physical activities (and the social opportunities associated with them) require what we call "fundamental motor skills". These skills include running, throwing, catching and so on. Our analysis, again, showed that exercise programs significantly improved these skills among children and adolescents with autism.

Looking ahead

We need more research on the effects of exercise on people with autism, in particular the type and duration of physical activity that is associated with the greatest benefits. We also need to determine how best to tailor and personalize physical activity programs to meet the needs and goals of each individual with autism.

Perhaps the most important question right now is how to ensure that people with autism get enough physical activity throughout their lives.

In the meantime, we hope our data will inspire fitness professionals, physical education teachers and parents who are trying to get children, teens and adults with autism involved in a variety of physical activities. The effort is well worth it—the benefits can be enormous.

Making exercise autism friendly

Research and our clinical experience have enabled us to understand what features of autism can interfere with the enjoyment of physical activity and how these barriers can be overcome.

For many people with autism, suggestions for physical activity are objected to, and in each case it is important to understand why. Not long ago, I tried to encourage a boy with autism to play with peers during recess. He replied: “I can’t think of a worse place for me!” I figured out what the problem is. I asked him to do something in a social, active, loud and unpredictable environment - all features that he could not stand.

A variety of problems may motivate people with autism to avoid physical activity. These may include low social and motor skills, a preference for computer-related activities, a lack of exercise partners, and an autism-friendly environment in sports facilities.

But the good news is that we know strategies that can reduce these problems. Here are some of the possible recommendations to help encourage regular physical activity.

1. Start small.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that a child be physically active for at least one hour a day. This is useful information, but I would advise you to set the most modest goal first, and then very gradually increase the load.

This is useful information, but I would advise you to set the most modest goal first, and then very gradually increase the load.

Our experience has shown that very short periods of physical activity that are distributed throughout the day are the easiest to maintain. Remember: the goal is for physical activity to be a regular and enjoyable part of everyday life. So be patient and make long term plans.

Here are some examples of how you can add physical activity to your daily life:

– Walk to school (work, other places), walk more distances than usual.

- Walk the dog (if you have one).

- Turn commercial breaks into exercise breaks while watching TV. I recommend a couple of minutes of intense physical activity like jumping jacks or leg swings. And do not sit by yourself, join the children.

- Daily visits to the playground, for example in the afternoon. If you have to walk to it, then so much the better.

I recommend gradually increasing the amount of time spent on these and other physical exercises. Your end goal is the recommended hour of physical activity that is a normal part of the day for your child.

Your end goal is the recommended hour of physical activity that is a normal part of the day for your child.

2. Develop motor skills.

Remember that your child must first develop fundamental motor skills before they can participate in physical activity and sports. To develop skills, you can offer your child a variety of games that will require him:

– Move in different ways (eg jump, jump over, jump on one foot).

- Play with various sports equipment such as balls, bats and rackets (throw, catch, kick or hit).

If a child practices these skills regularly at home, he or she will find it easier in physical education classes and will be more likely to enjoy sports with other children.

3. Offer to try a variety of physical activities.

Our analysis has shown that a wide variety of physical activities can be beneficial. Table tennis, swimming, cycling, horseback riding - there are a huge number of games and activities that your child can try. I recommend that you create a menu of these activities, and then try different "meals" from the menu until you find something your child likes.

I recommend that you create a menu of these activities, and then try different "meals" from the menu until you find something your child likes.

Ideally, the child should engage in one or more physical activities that encourage:

- Good physical shape. Any exercise that involves intense aerobic activity, that is, activity that makes you breathe heavily.

- Social interaction. Physical activity involving two or more people, such as tennis or ball games.

- Independence. Physical activity that you can do completely on your own, for example, home exercises or yoga exercises, maybe exercises with the help of a video.

4. Be a role model, involve friends and family.

Parents are the main role models for their children. I encourage you to be an example of an active lifestyle for your child. Show your child the value and enjoyment of physical activity.

Also think about the people the child comes in contact with every day or every week and whether they can be involved in encouraging the child to be physically active.

Teachers, especially physical education teachers, can have a huge impact on a child. Share with them your plans and strategies that have proven to be the most effective. If the child has an individual educational plan, then it is desirable that physical education goals are also included in it. If necessary, physical education teachers should be involved in the discussion of these goals.

Don't forget those who run sports programs for children in your area. Very often, the main obstacle for them is the fear that they will not be able to cope with the education of a child with autism. However, experience shows that if you give them a little confidence by sharing strategies to communicate and motivate the child, afterschool educators can make a big difference.

5. How to make physical activity more friendly.

Here are three strategies commonly used in sports programs for children and adolescents with autism:

Someone who understands. Ideally, it is important that people with autism, especially children and adolescents, participate in physical activity programs whose instructors have knowledge of autism, in particular, understand how to better communicate with people with autism and how to better motivate them. You don't need to be an autism specialist to do this - just the basics are enough. It can even be a "peer mentor" - another child who understands how to communicate with a child with autism and can provide one-on-one support.

Ideally, it is important that people with autism, especially children and adolescents, participate in physical activity programs whose instructors have knowledge of autism, in particular, understand how to better communicate with people with autism and how to better motivate them. You don't need to be an autism specialist to do this - just the basics are enough. It can even be a "peer mentor" - another child who understands how to communicate with a child with autism and can provide one-on-one support.

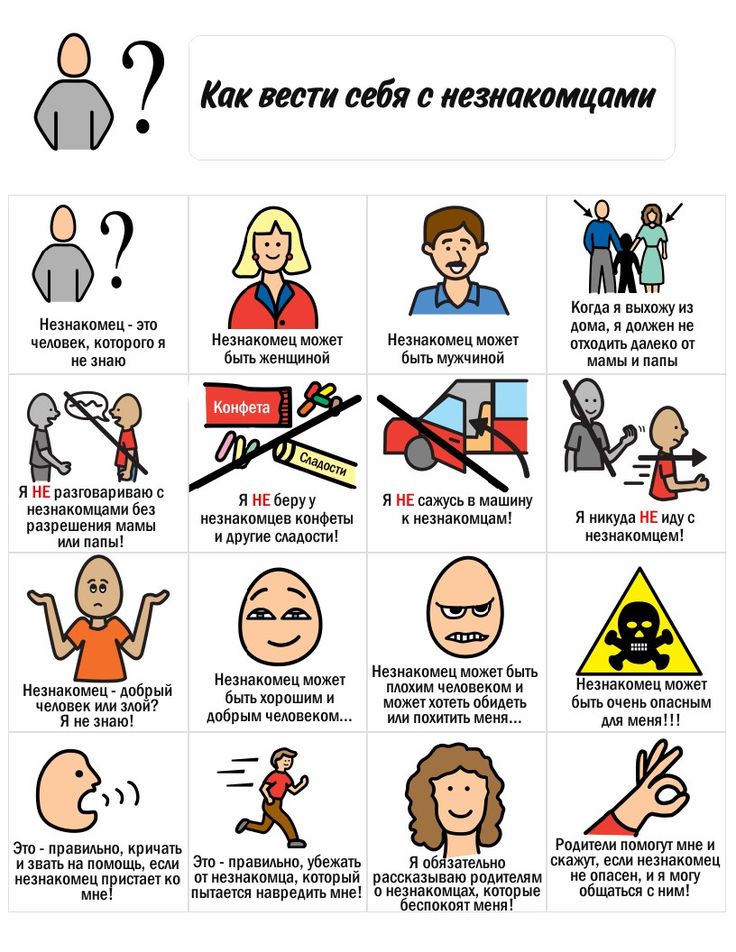

Visual support. Many people with autism perceive visual information better. Visual support is very effective in teaching children and adolescents with autism. This may include visual timetables, task cards, visual demonstrations, and video simulations. (See also: How to Use Visual Support for Autism.)

Routine. For most of us, routine is important - familiar environments and ways of doing things, but this is especially important for people on the autism spectrum.