How to raise an emotionally intelligent child pdf

3 Do’s and Don’ts for Raising Emotionally Intelligent Kids

With these three steps, you can raise children who are bright, confident, and better able to navigate the intricacies of life.

With these three steps, you can raise children who are bright, confident, and better able to navigate the intricacies of life.

With these three steps, you can raise children who are bright, confident, and better able to navigate the intricacies of life.

As parents, we want the very best for our kids. We work hard to raise strong individuals who will go on to lead happy lives and have good moral standing. Sometimes, however, we find ourselves questioning our parenting choices, crossing our fingers and hoping we’re doing this whole parenting thing right.

Our hopes, dreams, and fears about parenting will never cease, but as it turns out, we don’t have to wing it and rely on hope alone anymore. With Emotion Coaching we now have a science-based roadmap for how to raise well-balanced, higher achieving, and emotionally intelligent children.

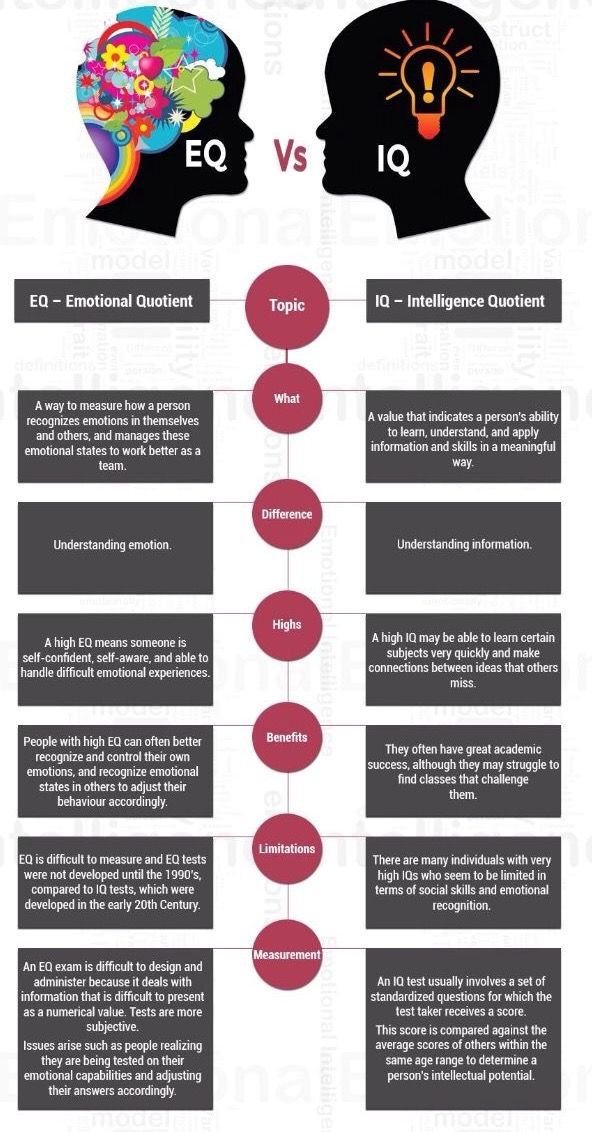

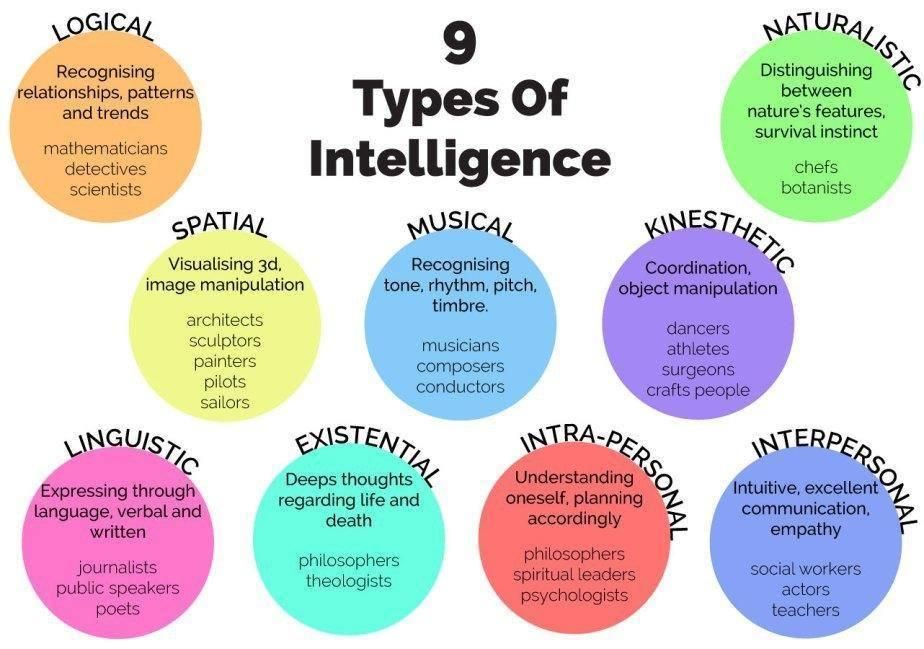

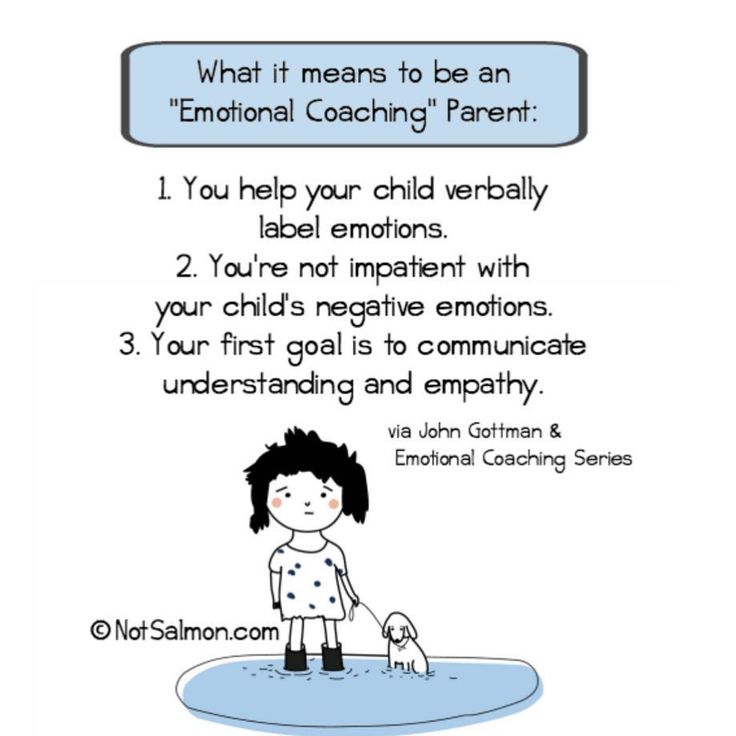

Research by Dr. John Gottman shows that emotional awareness and the ability to manage feelings will determine how successful and happy our children are throughout life, even more than their IQ. Being an Emotion Coach to our kids has positive and long-lasting effects, providing a buffer for the complexities of life that allows them to be more confident, intelligent, and well-rounded individuals.

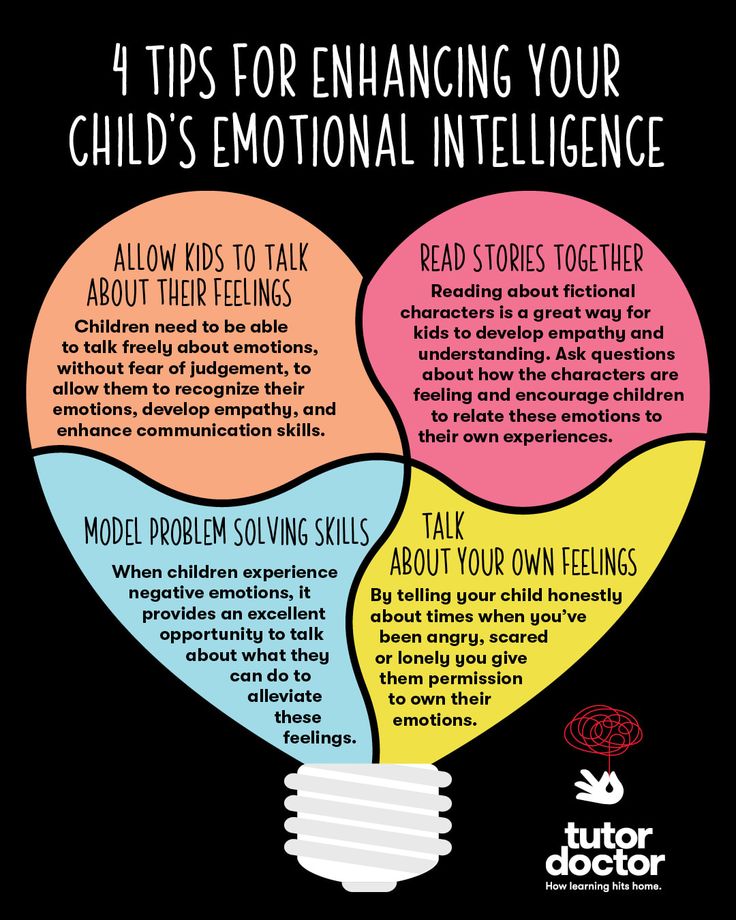

Below are three do’s and don’ts for building your child’s emotional intelligence.

1. Do recognize negative emotions as an opportunity to connect.

Use your child’s negative emotions as an opportunity to connect, heal, and grow. Children have a hard time controlling their emotions. Stay compassionate, loving, and kind. Communicate empathy and understanding so that your child can begin to understand and piece together their heightened emotional state. Try saying, “It sounds like you’re frustrated! I totally get it,” or, “You seem so angry right now. Is it because Sandy took your toy? I completely understand why you’d be angry. ”

”

Don’t punish, dismiss, or scold your child for being emotional.

Negative emotions are age appropriate and will eventually subside as kids grow. By disregarding their feelings as insignificant or sending the message that their feelings are bad, you are in effect sending the message that they are bad. This damaging perception can stay with them throughout adulthood.

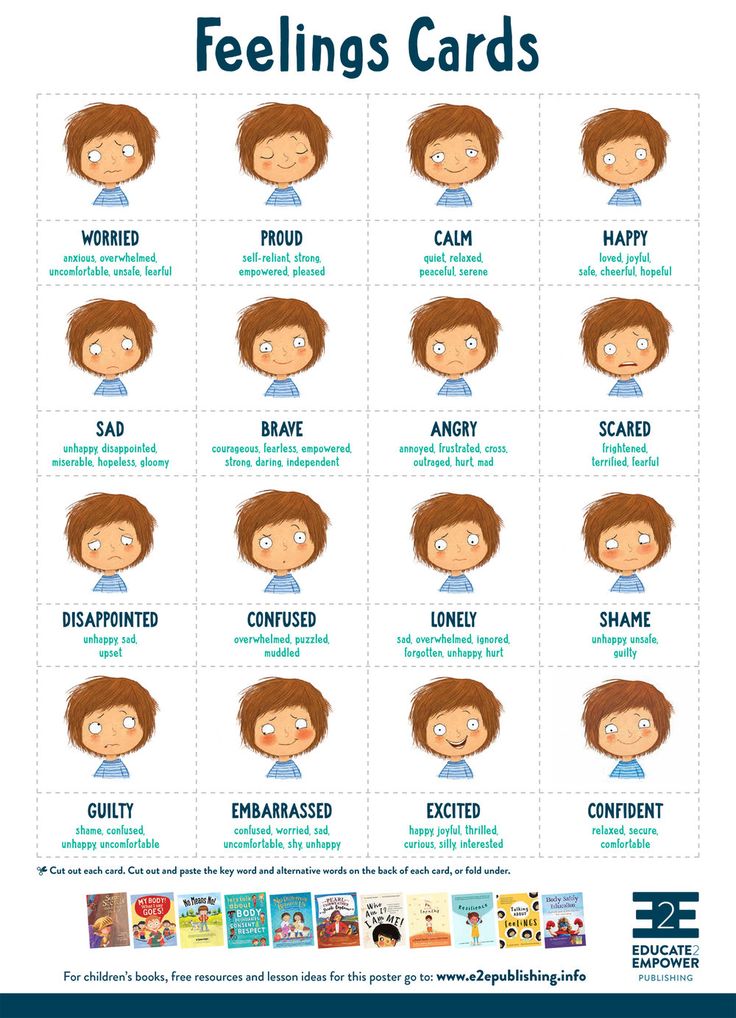

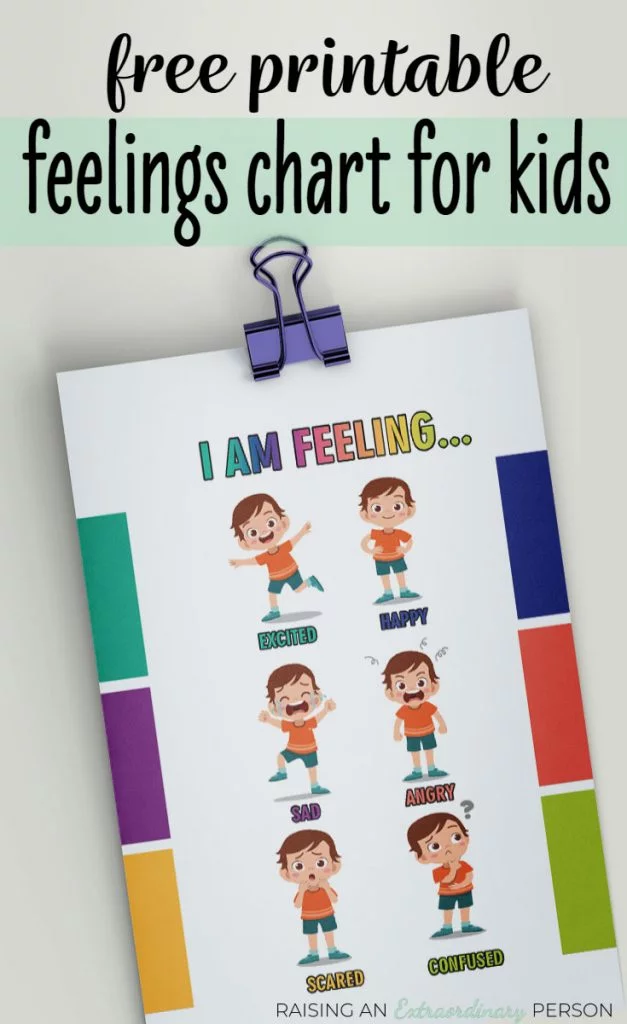

2. Do help your child label their emotions.

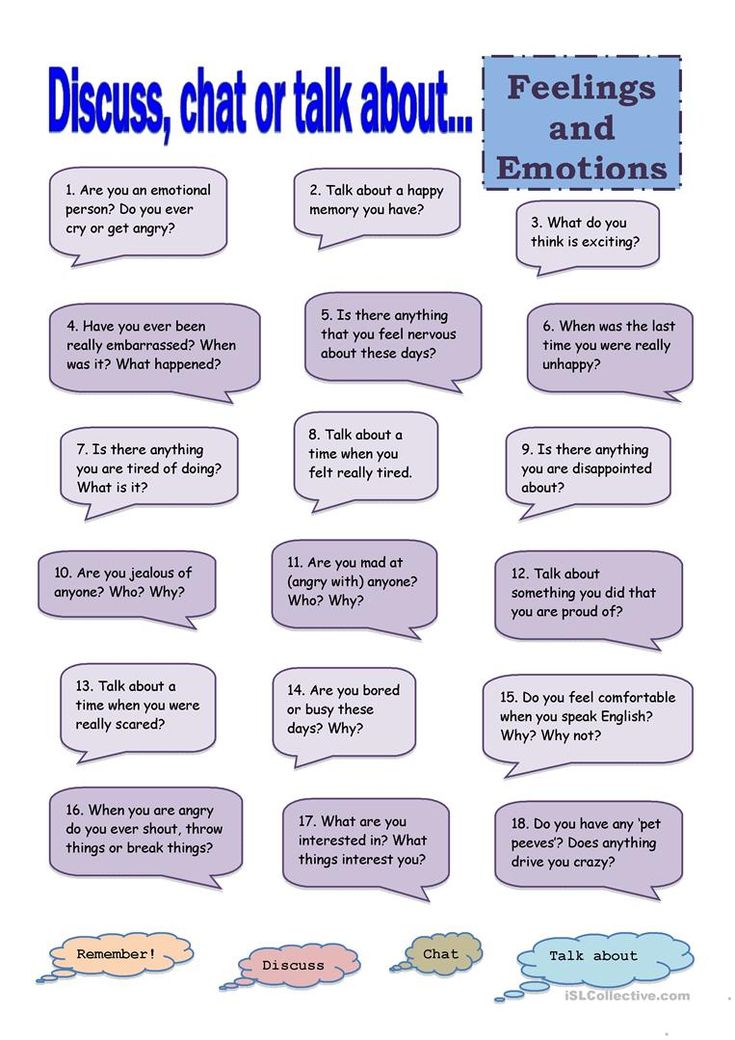

Help your child put words and meaning to how they’re feeling. Once children can appropriately recognize and label their emotions, they’re more apt to regulating themselves without feeling overwhelmed. Try using phrases like, “I can sense you’re getting upset” or, “It sounds like you’re really hurt.”

Don’t convey judgment or frustration.

Sometimes our kids can do or say things that are downright unacceptable and it’s hard to understand the emotions that seem unwarranted or irrational. But try putting yourself in your child’s shoes. Ask questions, seek understanding, and convey to them that you’re on their side, you support them, and you’re there to hold their hand through those moments where things feel overwhelming and tough.

Ask questions, seek understanding, and convey to them that you’re on their side, you support them, and you’re there to hold their hand through those moments where things feel overwhelming and tough.

3. Do set limits and problem-solve.

Help them find ways of responding differently in the future. Enlist their help in seeking alternative solutions to their struggles. Kids yearn for autonomy, and this is a great way to teach them that they are capable of self-regulating themselves in a world that seems unfair and particularly upsetting. Remind them that all emotions are acceptable but all behaviors are not. Here’s a great phrase to set limits and aid in problem solving: “I understand you’re upset, but hitting is not okay. How can you express your feelings without hitting next time?”

Don’t underestimate your child’s ability to learn and grow.

They have an innate capacity to develop into high functioning adults who can problem-solve and respond intelligently to life’s dilemmas. As children, however, they need a listening ear, a hand to hold, and a parent who can challenge them to reach from within and respond accordingly.

As children, however, they need a listening ear, a hand to hold, and a parent who can challenge them to reach from within and respond accordingly.

Being a parent is a challenging and never-ending job. With just three small steps, you can raise children who are bright, self-confident, and better able to navigate the intricacies of life with ease and confidence.

Subscribe below to receive useful tools for raising emotionally intelligent children directly to your inbox.

April Eldemire, LMFT

April Eldemire is a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist, Bringing Baby Home Educator, and couples expert in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. She is passionately devoted to helping couples achieve thriving relationships. For information on a Bringing Baby Home workshop, counseling services, or to subscribe to her Tip Sheet, visit her website.

We'll deliver the blog to you

Get our tips straight to your inbox, and master your relationships. ="wpforms-"]

="wpforms-"]

How to raise emotionally intelligent kids |

Nata Schepy

This post is part of TED’s “How to Be a Better Human” series, each of which contains a piece of helpful advice from people in the TED community; browse through all the posts here.

I’d like you to take a moment and imagine you’re four years old. You’re building a tower, and you’re really proud of it.

But then the next minute another child comes running along and kicks over your tower. You are outraged, and you feel all these feelings bubble up inside — hurt, panic, frustration and helplessness. Just then, an adult comes by.

They get close, get down to your level, and ask: “Honey, what happened?”

In their eyes, there’s compassion and you feel that their body is calm and regulated. And then all those feelings come bubbling out of you — frustration, anger, helplessness.

This adult says: “Tell me all about it. ” They don’t try and fix it, and they don’t say to you: “Don’t worry, you can build another one.” They just let you feel all that you’re feeling. Then they open their arms and you snuggle, take another deep breath, feel better and go back to building your tower.

” They don’t try and fix it, and they don’t say to you: “Don’t worry, you can build another one.” They just let you feel all that you’re feeling. Then they open their arms and you snuggle, take another deep breath, feel better and go back to building your tower.

If you were lucky, the adults in your life gave you lots of space to express how you feel without trying to fix what was going on.

Now I’d like you to try and remember being four years old and a time when you felt angry or sad or scared or you didn’t understand what was going on.

How did the adults in your life respond to you? If you were lucky, they gave you lots of space to express how you feel and listened to your worries and hurt without trying to fix what was going on.

But many of us probably had the opposite experience. Maybe we were told “Stop being so stupid” or “You don’t need to cry.” You might have been sent to your room or to the corner or even been hit for making a mistake.

We still value IQ far more than we value EQ.

Why am I talking about children and feelings? We’ve seen a steady increase in psychological distress among adults — in Australia and around the world. And I see this increase in distress as being rooted in part in the messages we received as children around how to express feelings and emotions.

Of course, it’s easy to blame our parents for what they did or didn’t do. But the real issue is the lack of emotional literacy in our culture. We don’t teach parents how to respond to children’s feelings and emotions with empathy and compassion. We also don’t teach it in our kindergartens; we don’t teach it in our schools. We still value IQ far more than we value EQ.

My work over the last 16 years with families around attachment, trauma and connection has shown me that there are usually three ways we learn as kids to deal with feelings and emotions.

You might have been labeled as “naughty”, “too much” or “trouble” when all you were doing was responding to your environment.

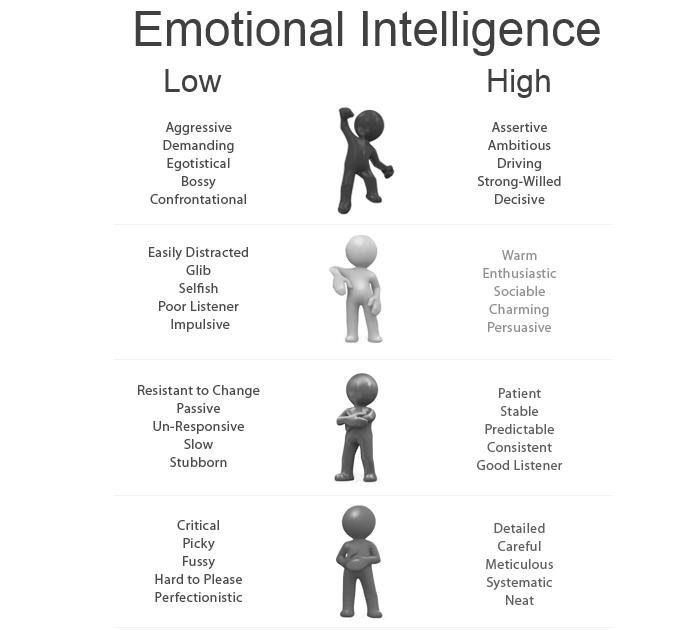

The first way is repression. Perhaps as a child, you learnt that it wasn’t safe to express your feelings. You might have gotten shut down and told to stop crying. Or you were given a look that made you draw everything inside and push them down deep. The impact of repression on a child is that those feelings stay there.

And then as adults, those feelings can turn up again when life throws us a curveball. Those same feelings come up, but this time, we respond by having another glass of wine or spending hours mindlessly scrolling through Facebook or making ourselves so busy at work that we don’t have time to feel .

The second way is aggression. As a child if we felt really powerless or scared and we grew up in an authoritarian environment where we didn’t have a voice and couldn’t say how we felt, then those feelings would again bubble up inside us. At the point where they would tip over when we felt most frightened or threatened, then they might come out in the form of aggression, rage, loud words. You might have been labeled as “naughty”, “too much” or “trouble” when all you were doing was responding to your environment.

You might have been labeled as “naughty”, “too much” or “trouble” when all you were doing was responding to your environment.

And then as adults, those tendencies show up in bullying behavior. Or they can turn up in harsh critical thoughts about ourselves and others. Or it can show up as violence.

The third way is expression. If we grew up with an imprint that said “Feelings are welcome. I will accept all of you — the happy bits, the sad bits, the joyous bits, the bits that are angry. I’m not going to try and fix them; I’m just going to hold you,” then as adults when things feel hard, we reach for our journal and write down our thoughts. Or we call a friend and say: “Hey, can you listen to me?” Or we might go for a run, do some yoga, speak to our therapist and find a way to lean into the feelings, we feel them and let them go.

When I was a new parent, my game plan was “I’ll just keep them happy all the time.” But that’s a ridiculous thing to do.

I am a mother to three beautiful teenagers. When I first became a parent, like many of you, I had absolutely no clue about what I was doing. When it came to understanding their feelings and emotions, my game plan was “I’ll just keep them happy all the time.” But, as anyone who has kids realizes, that’s a ridiculous thing to do. It is impossible and incredibly exhausting to try to keep people happy all the time. So I learned that I needed to find a way to help my children thrive emotionally and also create harmony for them in our home.

I’m lucky enough to understand and study trauma, and I began to see that what we need as humans is a safe place to unpack all of who we are. We need boundaries and holding, but we also need empathy and compassion for those big feelings that rise within. Instead of trying to fix their problems and trying to make them happy all the time, I just got down low and said: “Tell me all about it.”

And I just listened. Sometimes there were tears; sometimes, rage or complaining. But every time my only job was to sit there and hold space for them.

Sometimes there were tears; sometimes, rage or complaining. But every time my only job was to sit there and hold space for them.

What I began to see was emotional intelligence developing in my children.

How do we expect our children to have empathy and compassion for other people if we don’t show them how?

One evening, I realized just how powerful this was. I was making dinner but I also had to go teach a class so I was doing the hustle that most parents do.

I was just about to go out the door when my youngest daughter, who was five at the time, came into the kitchen. She looked unhappy, and I could see that she’s feeling some feelings. I actually turned to her and said: “Honey, do you think you could hold onto your feelings for a few hours?” Of course, she looked at me like, “Are you kidding?”

At that moment my middle daughter, who was then 10, walked into the room. She said, “I’ll listen to your feelings”, and I’m like “OK. ” So my 10-year-old took the 5-year-old into the bedroom, and I thought, I’m going to be late for work because I need to see what happens here.

” So my 10-year-old took the 5-year-old into the bedroom, and I thought, I’m going to be late for work because I need to see what happens here.

I stood outside their door, and I heard my 10-year-old say: “Tell me all about it.” And the five-year-old started crying and complaining about all the things that had happened at school.

The 10-year-old was going, “Oh that’s hard. What else?” And then there was more complaining and then more tears and giggles and laughter and they came out of the room.

I saw my 10-year-old and said to her, “Honey, how was that for you?” She looked at me and said, “Well, Mama, I just did to her what you do for me.”

At that moment, I realized that children can’t be what they can’t see. How do we expect them to have empathy and compassion for other people if we don’t show them how? How can we expect them to treat others with kindness and respect if they don’t know what that feels like in their own bodies?

I wonder:

- What would it be like if we actually supported parents with the tools and understanding to listen compassionately to their children?

- What would it be like if we actually helped parents unpack their own childhood, so they don’t have to carry that baggage and put it on their children’s shoulders?

- What would it be like if we supported and encouraged boys to cry and be vulnerable and girls to rage and find their voice and speak up for what they need?

- What if instead of harsh disciplines and punishments, we replaced them with compassionate listening and loving limits and boundaries?

- What would it look like if we took all of these ideas and placed them in our education system?

About 18 months ago, a colleague and I created Woodline Primary School. It’s set in the Geelong hinterlands on a beautiful farm with abundant nature. We have horses, chickens and veggie patches, and the philosophy of our school is to foster our students’ emotional well-being in a safe learning environment.

It’s set in the Geelong hinterlands on a beautiful farm with abundant nature. We have horses, chickens and veggie patches, and the philosophy of our school is to foster our students’ emotional well-being in a safe learning environment.

Sir Ken Robinson said the aims of education are to understand the world around us and the world within us. But what if we prioritized the world within?

Research shows that when children feel safe to learn — which means they feel free of judgment and criticism, they’re treated with kindness and respect, they have autonomy over their bodies and their learning, and they are given much love and celebrated for their unique differences — their neurological systems become fully operational and their capacity for growth and learning increases.

Our aim at Woodline is for children to learn about the world and also develop critical life skills such as emotional intelligence, growth mindset, critical thinking and a love of failure. Every time you fail, you realize, “Ah there are so many more options I haven’t yet explored!” More than anything, we want them to learn to be compassionate citizens of the Earth.

Every time you fail, you realize, “Ah there are so many more options I haven’t yet explored!” More than anything, we want them to learn to be compassionate citizens of the Earth.

The late great Sir Ken Robinson said that the aims of education are to understand the world around us and the world within us. But what if we prioritized the world within? Surely, the world around us would make so much more sense.

Just think: How different could the world be if we placed connection, heart and compassionate listening at the center of every one of our relationships?

This post was adapted from a TEDxDocklands Talk. Watch it here:

Read online “Child's Emotional Intelligence.

A Practical Guide for Parents, John Gottman - LitRes

A Practical Guide for Parents, John Gottman - LitRes Publisher Information

Published with permission from John Gottman, Ph.D. and Joan DeClaire, c/o Brockman, Inc.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the copyright holders.

© John Gottman, 1997

© Translation into Russian, edition in Russian, design. LLC "Mann, Ivanov and Ferber", 2018

* * *

Dedicated to the work and memory of Dr. Chaim Ginott

Foreword

CHILDREN ARE GOING OUT OF DIFFICULT TIMES, and so are their parents. Over the last one to two decades, there have been tremendous changes in children's lives that have made it more difficult for them to learn the skills of human feelings, which places additional demands on their parents. Parents should learn about more effective ways to teach their children the basics of emotional and social life. And this practical guide is designed to help them do just that. nine0007

And this practical guide is designed to help them do just that. nine0007

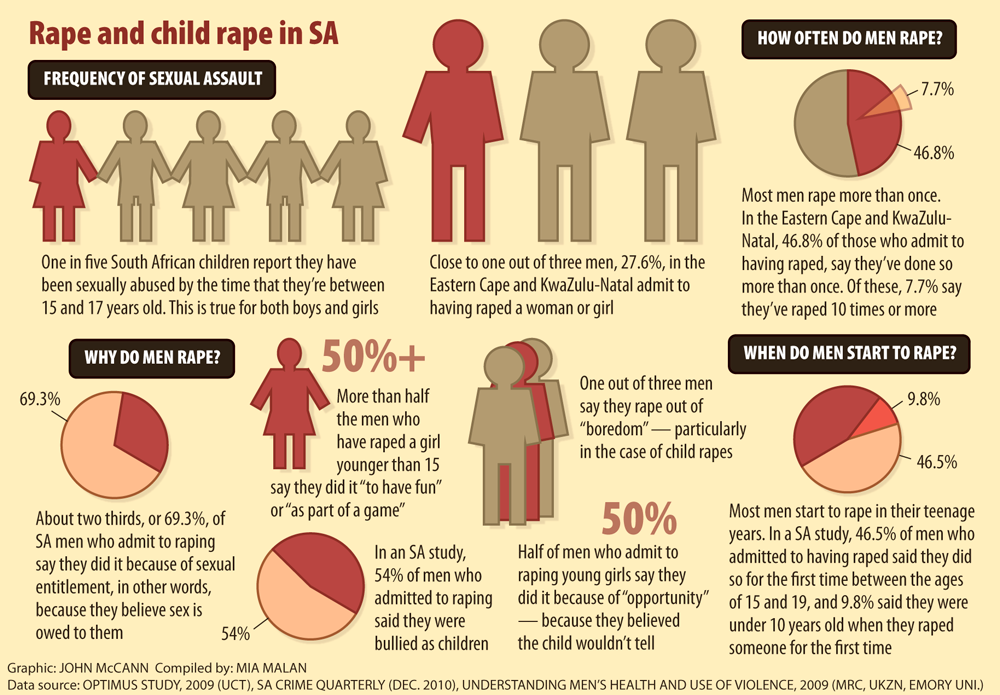

Perhaps emotional education has never been so necessary. Let's look at the statistics. Over the past few decades, teen homicides have quadrupled, suicides have tripled, and rapes have doubled. Behind these figures is the general emotional ill health of society. A study of a nationwide random sample of more than 2,000 American children as assessed by their parents and teachers, first in the mid-1970s and then in the late 1980s, showed a long-term downward trend in basic emotional and social skills. During this time, the indicators decreased by more than forty points. On average, children became more nervous and irritable, more sullen and moody, more depressed and lonely, more impulsive and rebellious.

This decline is the result of significant changes that have taken place in our society. New economic realities are forcing parents to work harder than previous generations, which means they have less free time to spend with their children than their own parents spent with them. An increasing number of families live far away from their relatives, often in areas where parents of young children are afraid to let them play on the streets, let alone visit their neighbors. Instead of playing with peers, children are spending more and more time in front of a TV or computer screen. nine0007

An increasing number of families live far away from their relatives, often in areas where parents of young children are afraid to let them play on the streets, let alone visit their neighbors. Instead of playing with peers, children are spending more and more time in front of a TV or computer screen. nine0007

But throughout the long history of human development, children have been exposed to basic emotions and social skills from their parents, relatives, neighbors, and from impromptu play with other children.

Lack of opportunity to learn the basics of emotional development leads to adverse consequences. Evidence shows that in girls, the inability to distinguish between feelings of anxiety and hunger in the future leads to disordered eating, and those who do not learn to control their impulses in their early years have a high chance of becoming pregnant in their teens. For boys, impulsivity in the early years can mean an increased risk of falling into crime and violence, and for all children, failure to cope with anxiety and depression increases the likelihood of drug or alcohol abuse later in life. nine0007

nine0007

Given the new environment, parents should make the most of the precious moments they can give to their children and make a concerted effort to instill in them key interpersonal skills such as understanding and coping with feelings that disturb them, impulse control, and empathy. In his book, John Gottman offers a scientifically sound and highly practical way for parents to give their children the tools they need for later life. nine0007

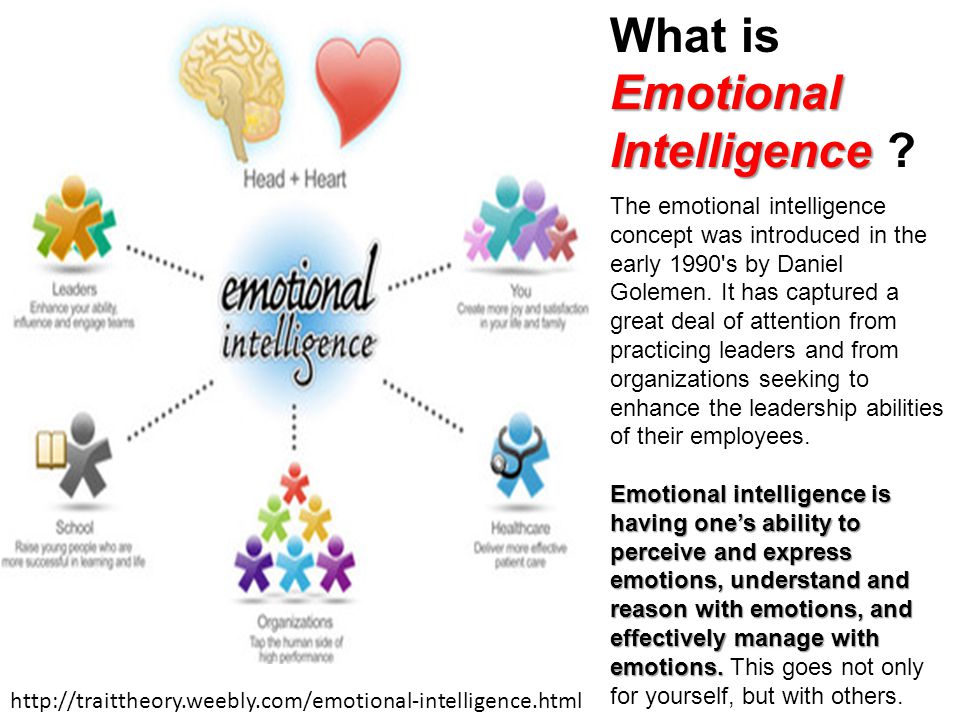

Daniel Goleman, author of

Emotional Intelligence and Emotional Intelligence in Business [1]

Introduction

BEFORE I BECAME A FATHER, I studied the emotional life of children for nearly twenty years. But it was not until 1990, when our daughter Morya was born, that I began to truly understand the relationship between parents and children.

Like many parents, I could not imagine the strength of feelings that I would experience for my child. I had no idea how excited I would be when she smiled for the first time, learned to speak and read a book. I had no idea how much patience and attention she would demand from me every minute and how much I would want to satisfy her need for attention. On the other hand, I was surprised by the feelings of disappointment, disappointment and vulnerability that I began to experience with the birth of my daughter. I was upset when I could not communicate with her. Frustrated when she misbehaved. Felt vulnerable when I realized how dangerous the world could be. For me, the loss of my daughter would mean that I lost everything. nine0007

I had no idea how much patience and attention she would demand from me every minute and how much I would want to satisfy her need for attention. On the other hand, I was surprised by the feelings of disappointment, disappointment and vulnerability that I began to experience with the birth of my daughter. I was upset when I could not communicate with her. Frustrated when she misbehaved. Felt vulnerable when I realized how dangerous the world could be. For me, the loss of my daughter would mean that I lost everything. nine0007

Being aware of my own emotions has helped me make a number of discoveries in my professional life. As a Jew whose parents managed to escape from Austria to avoid being victims of the Holocaust, I was close to theorists who rejected authoritarianism as a way to raise morally healthy children. I believed that the family should be democratic and that children and parents should act as reasonable and equal partners, and my years of research into the dynamics of family life have shown that the greatest influence on the well-being of children in the long term is emotional interactions between parents and children.

Surprisingly, b o Most of today's popular parenting advice ignores the emotional world. They rely on parenting theories that emphasize wrongdoing and ignore the feelings that motivate them. However, the ultimate goal of raising children is not to raise an obedient and accommodating child. Most parents want much more for their children: to raise moral and responsible people who contribute to society, are strong enough to make their own choices, use their talents, love life and the pleasures it offers, have friends, conclude successful marriages become good parents themselves. nine0007

In the course of my research, I found that love alone is not enough. It turned out that the secret of parenting is how parents communicate with their children in emotional moments. Unfortunately, it often happens that the attitude of loving and caring parents towards emotions (their own and their children) gets in the way of communication with the child when he is afraid, or angry, or very sad. This shortcoming can be eliminated by acquiring basic emotional education skills. nine0007

This shortcoming can be eliminated by acquiring basic emotional education skills. nine0007

I have studied families in detail through carefully designed laboratory experiments and observed the further development of children. After ten years of research, I found a group of parents whose children developed better than others. It turned out that when these children experienced strong emotions, their parents did five very simple things that I called "emotional parenting."

Growing up, children with whom parents engaged in emotional education became what Daniel Goleman calls "emotionally developed" people. They knew how to better manage their emotions, calmed themselves faster when they were upset, their heartbeats returned to normal sooner. Due to the higher efficiency of physiological reactions responsible for calming, they were less sick with infectious diseases. They had a higher ability to concentrate. They developed better relationships with other children even in difficult social situations during adolescence, when excessive emotionality is a significant obstacle (for example, when they are teased). They understood people better, they had more friends, they did better in school. In other words, they developed a kind of IQ with respect to people and the world of feelings, or emotional intelligence. This book will give you five steps to help you develop your child's emotional intelligence. nine0007

They understood people better, they had more friends, they did better in school. In other words, they developed a kind of IQ with respect to people and the world of feelings, or emotional intelligence. This book will give you five steps to help you develop your child's emotional intelligence. nine0007

My emphasis on the emotional bond between parent and child is based on extensive research. To my knowledge, these were the first studies to confirm the ideas of one of the most brilliant pediatric clinicians and psychologists, Dr. Chaim Ginott. He presented his ideas in three books written in the 1960s. Ginott understood the importance of communicating with children at times when they were experiencing strong emotions, and established basic principles for doing this most effectively. nine0007

Emotional education is a series of activities that helps create emotional bonds. When parents empathize with their children and help deal with negative feelings such as anger, sadness, and fear, they build mutual trust and affection. And while it is not uncommon for parents who practice emotional education to set some taboos, it is not the disobedience of children that is the reason for this. Compliance, obedience and responsibility are born from the love and connection that children feel with their families. That is, the basis of adherence to the values of the family and the education of moral people are emotional interactions between family members. Children behave according to family standards because they feel in their hearts that good behavior is expected of them and that doing the right thing is the property of belonging to the family clan. nine0007

And while it is not uncommon for parents who practice emotional education to set some taboos, it is not the disobedience of children that is the reason for this. Compliance, obedience and responsibility are born from the love and connection that children feel with their families. That is, the basis of adherence to the values of the family and the education of moral people are emotional interactions between family members. Children behave according to family standards because they feel in their hearts that good behavior is expected of them and that doing the right thing is the property of belonging to the family clan. nine0007

Unlike other parenting theories that offer a mixture of strategies to curb bad behavior in children, the five steps of emotional parenting provide the foundation for maintaining close relationships with your children at all stages of their development.

What is new in this book is the scientifically based conclusion that emotional interactions between parent and child play a major role. Now we know for sure that when moms and dads use emotional nurturing, they make an invaluable contribution to the success and happiness of their children. nine0007

Now we know for sure that when moms and dads use emotional nurturing, they make an invaluable contribution to the success and happiness of their children. nine0007

The approach I propose to parenting through working with children's emotions can help modern parents who face problems that were unimaginable in the 1960s. With the increase in divorce rates and rising violence among young people, raising emotionally healthy children becomes even more important. The proposed method allows protecting children from the risks caused by marital conflicts and divorces. In addition, I talk about how emotionally connected fathers, married or divorced, affect the well-being of their children. nine0007

The key to successful parenting is not to be found in complicated theories, family rules or intricate formulas of behavior, but in the deepest feeling of love and affection for your child, which manifests itself through empathy and understanding. Good parenting starts in your heart and continues when your children experience strong emotions: upset, angry, or fearful. It is to provide support when it really matters. This book will show you the right path. nine0007

It is to provide support when it really matters. This book will show you the right path. nine0007

Chapter 1. Emotional intelligence. The Key to Raising an Emotional Child

* * *

DIANA IS ALREADY LATE FOR WORK because she can't get her three-year-old son Joshua to wear a jacket to take him to kindergarten. After a hurried breakfast and a fight over the boots he'll wear, Joshua is tense. He does not care at all that in less than an hour his mother has to attend an important meeting. He says he wants to stay at home and play. When Diana explains to him that this is impossible, the child falls to the floor. He is frustrated, angry and starts crying. nine0007

Five minutes before the babysitter arrives, seven-year-old Emily addresses her parents in tears. "It's not fair that you leave me with a stranger," she sobs. “But Emily,” Dad explains to her, “the nanny is a good friend of your mom. In addition, we bought tickets for this concert a few weeks ago.” “But I still don’t want you to leave,” the girl cries.

Fourteen-year-old Matt tells his mother that he was kicked out of the school band because someone was smoking marijuana on the bus and the teacher thought it was him. “I swear to God it wasn’t me,” Matt says. But the boy's grades worsened, and in addition he got a new company. "I don't believe you, Matt," says the mother. “And until you fix your grades, I won’t let you go anywhere.” Without a word, Matt rushes out the door in a rage. nine0007

Three families. three conflicts. These children are of different ages, they are at different stages of development, but nevertheless their parents are faced with the same problem - how to cope with children when they are overwhelmed by emotions. Like most parents, they want to treat their children fairly, with patience and respect. They know that the world has many challenges for children and they want to be there to explain and support. They want to teach their children how to solve problems effectively and build strong and healthy relationships with them. They are want to treat them right, but they don't have the means to do so.

They are want to treat them right, but they don't have the means to do so.

A good upbringing requires more than mere intellectual guidance. It affects personality traits that most of the advice that parents have received over the past thirty years does not take into account. Good parenting includes the impact on emotions .

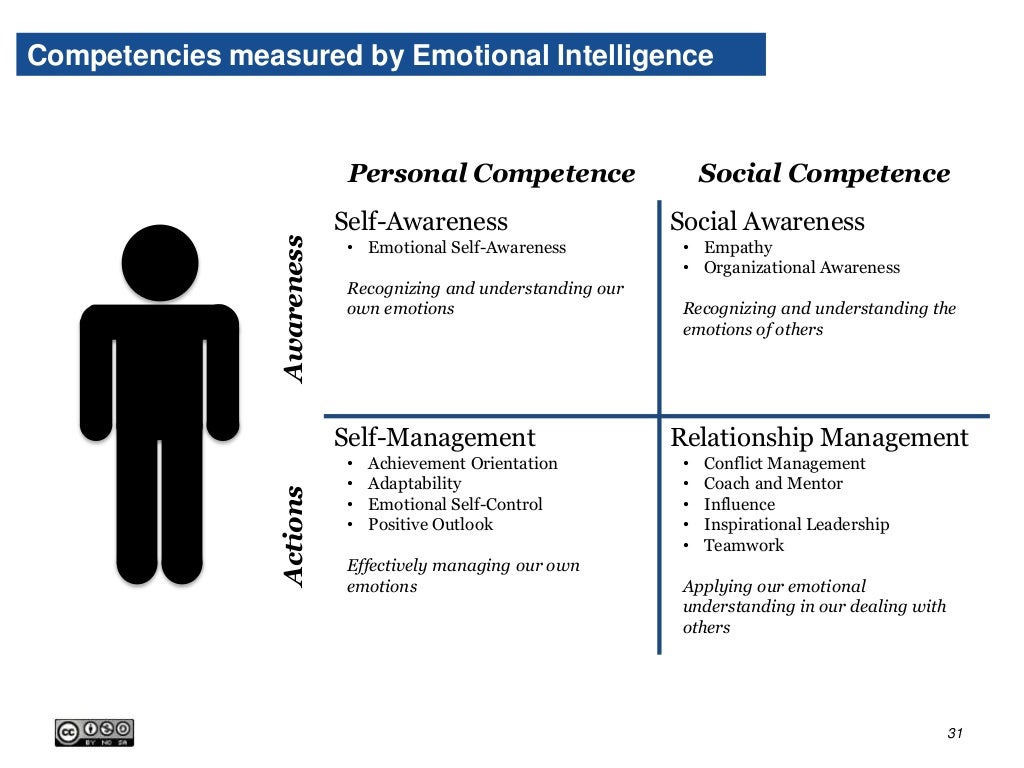

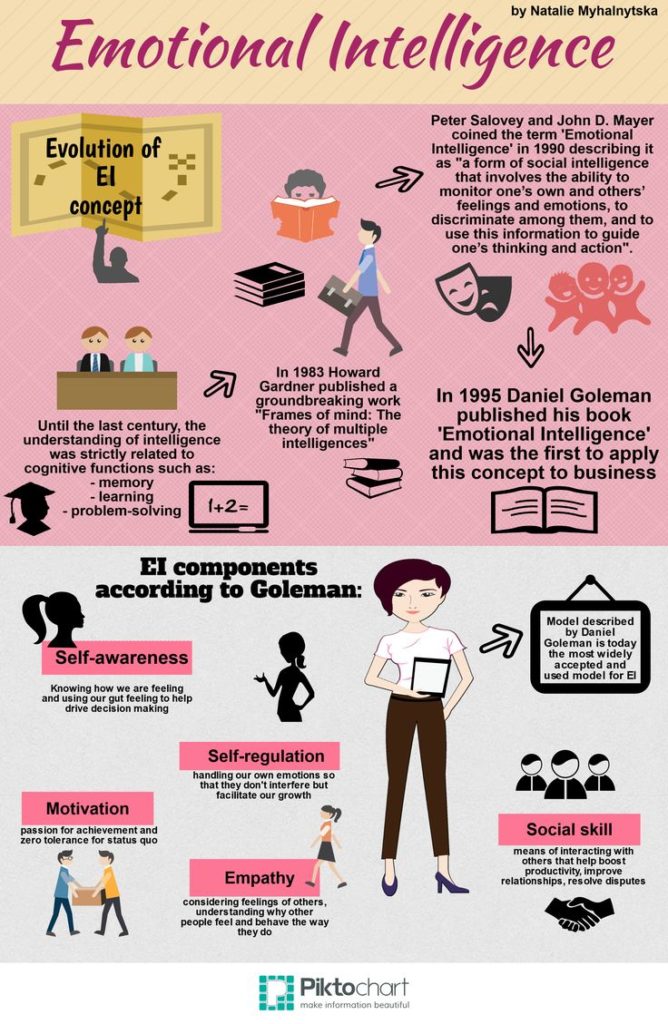

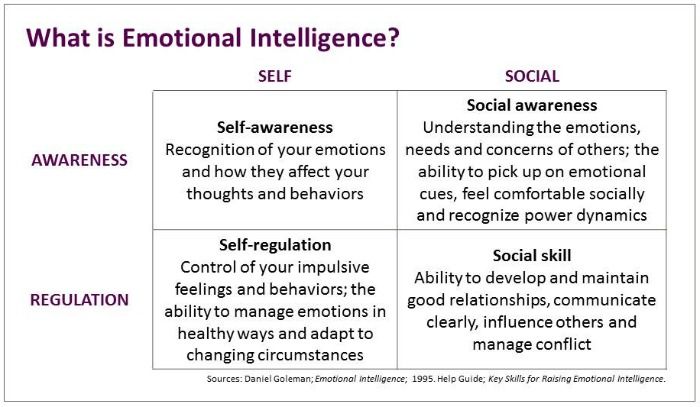

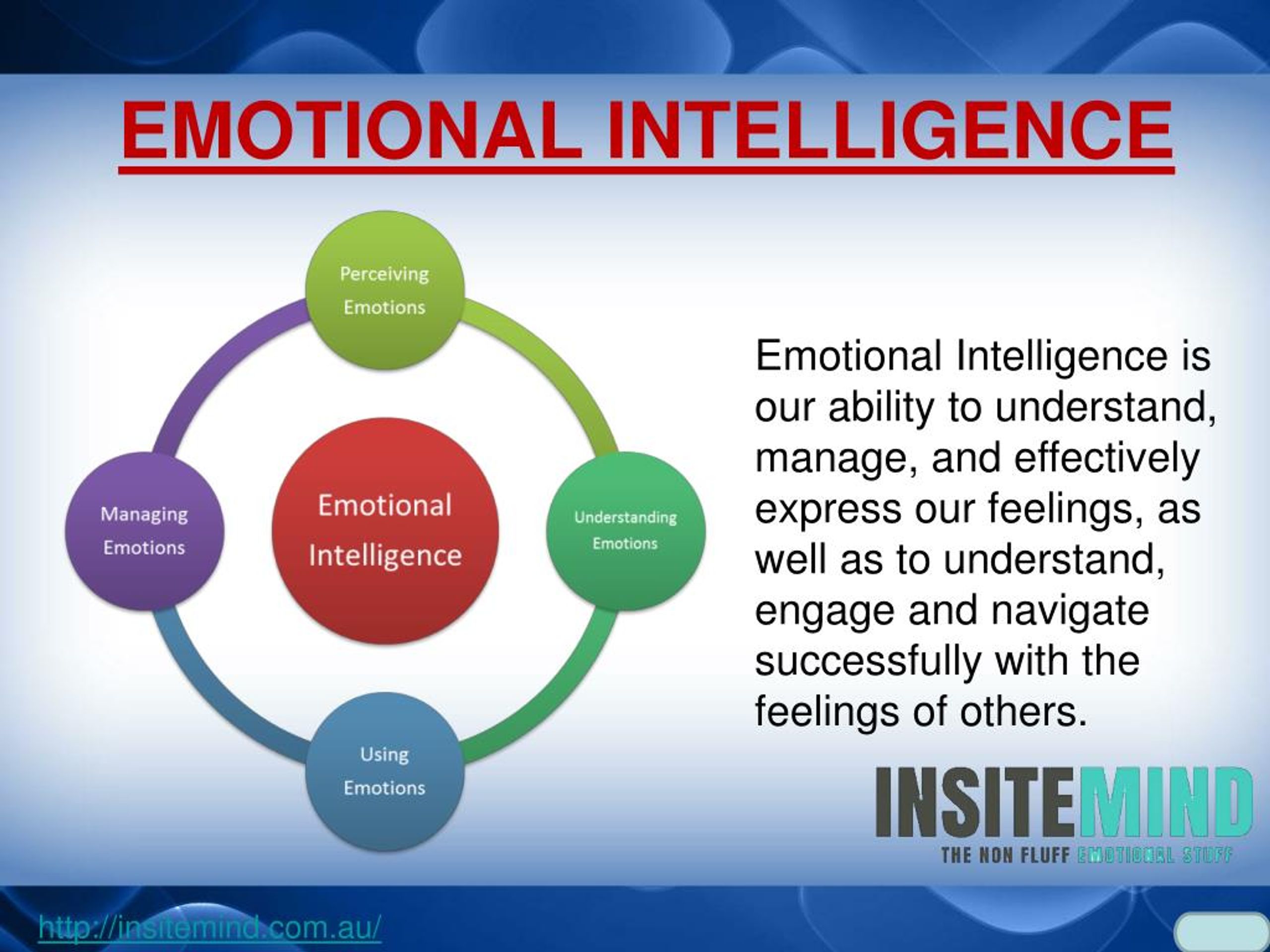

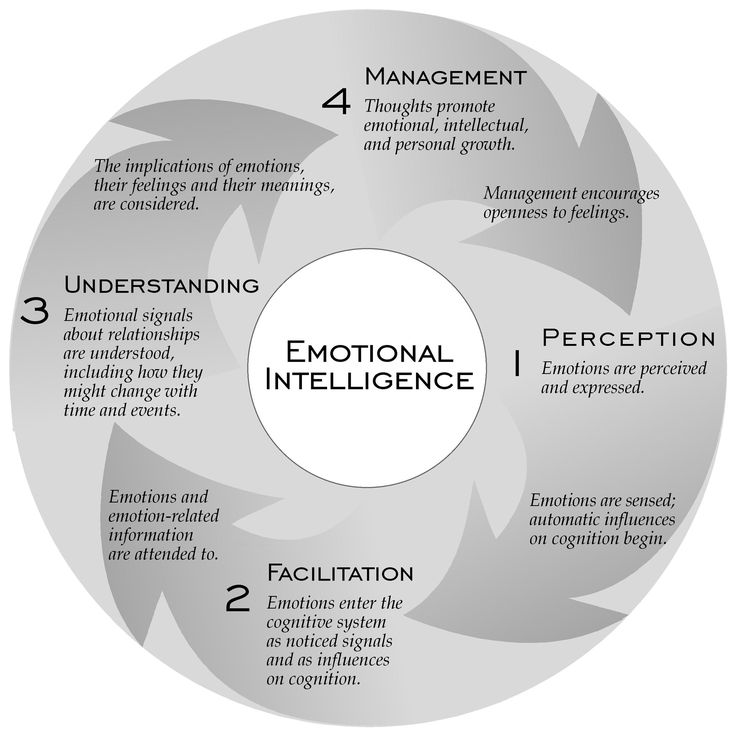

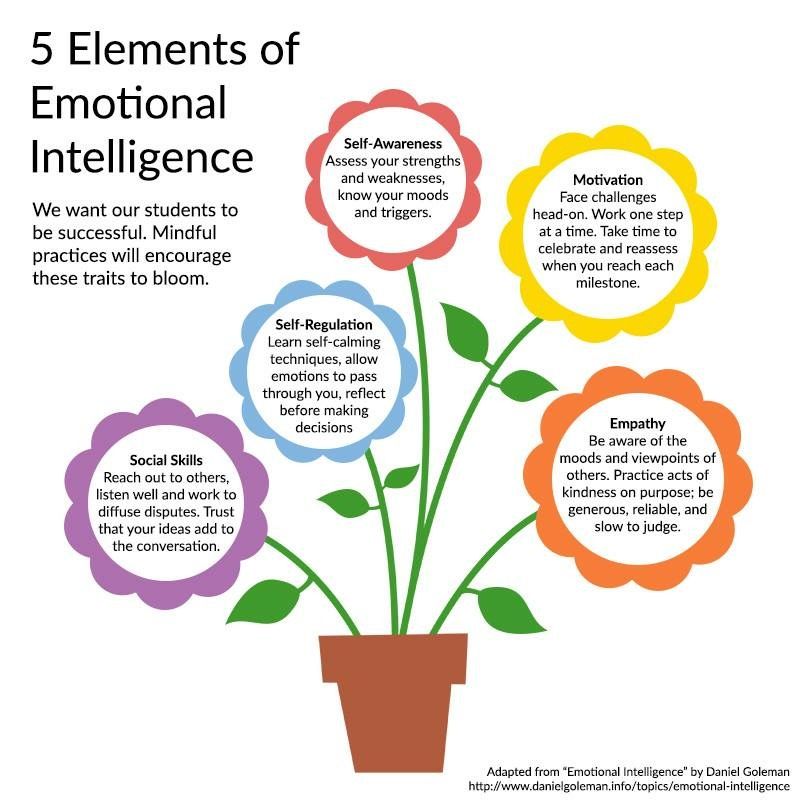

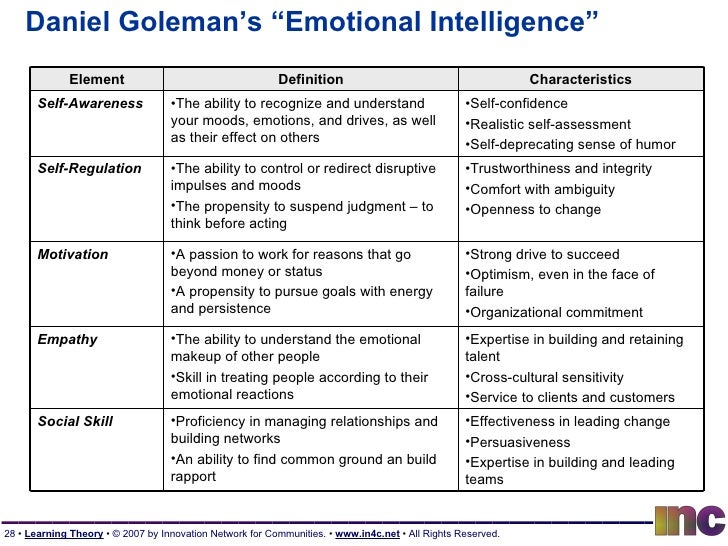

Over the past decade, scientists have found out how important role emotions play in our lives. They learned that success and happiness in all areas of life, including family relationships, is determined by being aware of your emotions and being able to manage your feelings. This quality is called "emotional intelligence". From the point of view of education, it means that parents should understand the feelings of their children, be able to sympathize with them, soothe and guide them. In children who receive b to Most of the lessons of emotion regulation from their parents, this quality means the ability to control impulses, motivate yourself, understand other people's social cues, and deal with the ups and downs in your life.

“The family is where we first begin to study emotions,” writes Daniel Goleman, psychologist and author of Emotional Intelligence [2] , which details the scientific research that has enabled us to delve deeper into this area of knowledge. “In the family, we learn for the first time how we should feel about ourselves, how we should think about these feelings, how we can respond to them, and how to understand and express our hopes and fears. This emotional education includes not only what parents say and how they behave directly with children, but also ways that help them cope with their own feelings, the exchange of emotions that occurs between husband and wife. Some parents are gifted emotional teachers, others are terrible." nine0007

How do these parents behave differently? Because I am a research psychologist who studies parent-child interactions, I have spent most of the last twenty years trying to answer this question. Working with research teams at the University of Illinois and Washington University, I conducted two in-depth studies of 119 families, observing how parents and children react to each other in emotionally charged situations [3] . We followed these children from the age of four to adolescence. In addition, we are monitoring 130 newlywed couples as they become parents of young children. Our research includes lengthy conversations with parents, discussions of their marriages, their reactions to their children's emotional experiences, and their awareness of the role of emotions in life. We assessed the physiological responses of children during stressful parent-child interactions. We carefully observed and analyzed the emotional reactions of parents to the anger and sadness of their children [4] . These families were then re-contacted to find out how their children were developing—about their health, academic performance, emotional development, and social relationships.

We followed these children from the age of four to adolescence. In addition, we are monitoring 130 newlywed couples as they become parents of young children. Our research includes lengthy conversations with parents, discussions of their marriages, their reactions to their children's emotional experiences, and their awareness of the role of emotions in life. We assessed the physiological responses of children during stressful parent-child interactions. We carefully observed and analyzed the emotional reactions of parents to the anger and sadness of their children [4] . These families were then re-contacted to find out how their children were developing—about their health, academic performance, emotional development, and social relationships.

Our results tell a simple but fascinating story. We found that most parents fall into one of two categories: those who teach their children to manage their feelings and those who do not.

Parents who are taught to manage emotions, I call "emotional educators. " Like sports coaches, they teach their children how to handle ups and downs. These parents allow children to express their negative emotions. They accept them as a fact of life and use emotional moments to teach children important life lessons and build closer relationships with them. nine0007

" Like sports coaches, they teach their children how to handle ups and downs. These parents allow children to express their negative emotions. They accept them as a fact of life and use emotional moments to teach children important life lessons and build closer relationships with them. nine0007

“When Jennifer is sad, I think it's a very important time to create a bond between us,” says Maria, the mother of a five-year-old girl in one of our studies. “I say I want to talk to her and find out how she feels.”

Like many emotional parenting parents, Dan, Jennifer's dad, sees his daughter's sadness and anger as the time she needs it the most. “It’s moments like this that make me feel like a father the most,” Dan says. “I should be by her side… I should tell her that everything is all right. That she will survive this problem, as well as many others. nine0007

Parents like Maria and Dan can be described as "warm" and "positive," but warmth and a positive attitude alone are not enough to develop emotional intelligence. In fact, b o Most parents treat their children with love and attention, but not all of them are able to effectively deal with their negative emotions. Among parents who cannot develop emotional intelligence in their children, I have identified three types:

In fact, b o Most parents treat their children with love and attention, but not all of them are able to effectively deal with their negative emotions. Among parents who cannot develop emotional intelligence in their children, I have identified three types:

1. Rejectors are those who do not attach importance to the negative emotions of their children, ignore them or consider them a trifle. nine0007

2. Those who disapprove are those who criticize their children for displaying negative emotions, who may reprimand or even punish them for them.

3. Non-interfering - they accept the emotions of their children, empathize, but do not offer solutions and do not set limits on the behavior of their children.

To show you how differently emotional caregivers and the three types above respond to their children's feelings, let's imagine Diana, whose toddler doesn't want to go to kindergarten, in each of these three roles. nine0007

If Diana were a rejecting parent, she could tell Joshua that not wanting to go to kindergarten is stupid; that there is no reason to be sad because he leaves home. Then she could try to distract him from his sad thoughts, perhaps by bribing him with cookies or by telling him about interesting activities that the caregiver has planned.

Then she could try to distract him from his sad thoughts, perhaps by bribing him with cookies or by telling him about interesting activities that the caregiver has planned.

If she was the disapproving type, she might scold Joshua for not cooperating, say she was tired of his willful behavior, and threaten to spank him. nine0007

Being a non-interventionist, she could accept Joshua's frustration and anger, sympathize with him, say that it is natural for him to want to stay at home, but would not know what to do next. Unable to leave him at home and not wanting to scold, spank or bribe, perhaps in the end she would make a deal: I will play with you for ten minutes, and after that we will leave the house without tears. And it could drag on until tomorrow morning.

What would an emotional educator do? Start as a non-interfering parent with empathy, letting Joshua know that he understands his sadness, and then go further and show how he can deal with unpleasant emotions. Perhaps their conversation would go something like this:

Perhaps their conversation would go something like this:

Diana : Put on your jacket, Joshua. Time to go.

Joshua : No! I don't want to go to kindergarten.

Diana : Would you like to go? Why?

Joshua : Because I want to stay here with you.

Diana : Do you want to stay?

Joshua : Yes, I want to stay at home.

Diana : Damn, I think I know how you feel. Sometimes in the morning I also want you and me to climb into a chair and look at books together, and not rush to the door. But you know what? I made a promise to people at work that I would come exactly at 9:00 and I can't break my promise.

Joshua (begins to cry): Why can't you? It's not fair. I do not want to go.

Diana : Come here, Josh. (Puts him on her knees.) I'm sorry, dear, but we can't stay at home. I understand you feel upset?

Joshua (nods): Yes.

Diana : Are you sad too?

Joshua : Yes.

Diana : I feel a bit sad too. (She lets him cry for a while while sitting in her arms.) I know what we can do. Let's think about the day when we don't have to go to work or kindergarten. We can spend the whole day together. Can you think of anything special that you would like to do? nine0007

Joshua : Eating pancakes and watching cartoons?

Diana : Yes, that would be great. Anything else?

Joshua : Can we take my truck to the park?

Diana : Probably yes.

Joshua : Can we take Kyle with us?

Diana : Maybe. We should ask his mom. But now it's time to go to work, okay?

Joshua : Good. nine0007

At first glance, the emotional caregiver may seem like a rejecting parent because it distracts Joshua from staying at home. But there is a significant difference between them. As an emotional educator, Diana acknowledged her son's sadness, helped him name her emotion, allowed him to feel it, and stayed by his side while he cried. She didn't try to divert his attention from her feelings. She did not scold him for his sadness, as a disapproving mother would. She let him know that she respects his feelings and thinks his desire is justified. nine0007

As an emotional educator, Diana acknowledged her son's sadness, helped him name her emotion, allowed him to feel it, and stayed by his side while he cried. She didn't try to divert his attention from her feelings. She did not scold him for his sadness, as a disapproving mother would. She let him know that she respects his feelings and thinks his desire is justified. nine0007

In contrast to the non-interfering mother, the emotional educator sets the boundaries of the child's whims. She took a few extra minutes to work through Joshua's feelings, but let him know that she wasn't going to be late for work and break her promise to her colleagues. Joshua was disappointed, and Diana shared this feeling with him. By doing so, she gave Joshua the opportunity to recognize, feel, and accept the emotion, and then she showed him that it is possible to move beyond your sadness, wait, and enjoy the next day. nine0007

This answer is part of a process of emotional education that my colleagues and I infer from observing successful parent-child interactions. The process usually consists of five steps.

The process usually consists of five steps.

Parents:

1) understand what emotion the child is experiencing;

2) view emotions as an opportunity for bonding and learning;

3) listen sympathetically and acknowledge the child's feelings;

4) help the child find words to describe the emotion he is experiencing; nine0007

5) Explore problem-solving strategies with the child while setting boundaries.

Education of emotional responsiveness to peers in preschoolers

%PDF-1.5 % 10 obj > /Metadata 4 0 R >> endobj 5 0 obj /Title >> endobj 20 obj > endobj 3 0 obj > endobj 40 obj > stream

32 841.92] /Contents[140 0 R 141 0 R 142 0 R] /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 0 /Annots [143 0R] >> endobj 70 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 144 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 4 >> endobj 80 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 146 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 7 >> endobj 9 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 147 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 8 >> endobj 10 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 148 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 9 >> endobj 11 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 149 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 10 >> endobj 12 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 150 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 11 >> endobj 13 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.

32 841.92] /Contents[140 0 R 141 0 R 142 0 R] /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 0 /Annots [143 0R] >> endobj 70 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 144 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 4 >> endobj 80 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 146 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 7 >> endobj 9 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 147 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 8 >> endobj 10 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 148 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 9 >> endobj 11 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 149 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 10 >> endobj 12 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 150 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 11 >> endobj 13 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595. 32 841.92] /Contents 151 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 12 >> endobj 14 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 152 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 13 >> endobj 15 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 153 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 14 >> endobj 16 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 154 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 15 >> endobj 17 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 157 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 16 >> endobj 18 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 158 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 17 >> endobj 19 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 159 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 18 >> endobj 20 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.

32 841.92] /Contents 151 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 12 >> endobj 14 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 152 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 13 >> endobj 15 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 153 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 14 >> endobj 16 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 154 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 15 >> endobj 17 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 157 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 16 >> endobj 18 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 158 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 17 >> endobj 19 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 159 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 18 >> endobj 20 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595. 32 841.92] /Contents 160 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 19 >> endobj 21 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 161 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 20 >> endobj 22 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 162 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 21 >> endobj 23 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 163 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 22 >> endobj 24 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 164 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 23 >> endobj 25 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 165 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 24 >> endobj 26 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 167 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 25 >> endobj 27 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.

32 841.92] /Contents 160 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 19 >> endobj 21 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 161 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 20 >> endobj 22 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 162 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 21 >> endobj 23 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 163 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 22 >> endobj 24 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 164 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 23 >> endobj 25 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 165 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 24 >> endobj 26 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 167 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 25 >> endobj 27 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595. 32 841.92] /Contents 168 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 26 >> endobj 28 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 169 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 27 >> endobj 29 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 170 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 28 >> endobj 30 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 171 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 29 >> endobj 31 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 172 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 30 >> endobj 32 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 173 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 31 >> endobj 33 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 174 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 32 >> endobj 34 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.

32 841.92] /Contents 168 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 26 >> endobj 28 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 169 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 27 >> endobj 29 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 170 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 28 >> endobj 30 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 171 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 29 >> endobj 31 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 172 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 30 >> endobj 32 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 173 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 31 >> endobj 33 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 174 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 32 >> endobj 34 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595. 32 841.92] /Contents 175 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 33 >> endobj 35 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 176 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 34 >> endobj 36 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 177 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 35 >> endobj 37 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 178 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 36 >> endobj 38 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 179 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 37 >> endobj 39 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 180 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 38 >> endobj 40 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 182 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 39 >> endobj 41 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.

32 841.92] /Contents 175 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 33 >> endobj 35 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 176 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 34 >> endobj 36 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 177 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 35 >> endobj 37 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 178 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 36 >> endobj 38 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 179 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 37 >> endobj 39 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 180 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 38 >> endobj 40 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 182 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 39 >> endobj 41 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595. 32 841.92] /Contents 183 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 40 >> endobj 42 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 184 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 41 >> endobj 43 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 185 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 42 >> endobj 44 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 186 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 43 >> endobj 45 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 187 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 44 >> endobj 46 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 188 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 45 >> endobj 47 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 189 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 46 >> endobj 48 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.

32 841.92] /Contents 183 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 40 >> endobj 42 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 184 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 41 >> endobj 43 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 185 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 42 >> endobj 44 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 186 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 43 >> endobj 45 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 187 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 44 >> endobj 46 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 188 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 45 >> endobj 47 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 189 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 46 >> endobj 48 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595. 32 841.92] /Contents 190 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 47 >> endobj 49 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 191 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 48 >> endobj 50 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 192 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 49 >> endobj 51 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 193 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 50 >> endobj 52 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 194 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 51 >> endobj 53 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 195 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 52 >> endobj 54 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 196 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 53 >> endobj 55 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.

32 841.92] /Contents 190 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 47 >> endobj 49 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 191 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 48 >> endobj 50 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 192 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 49 >> endobj 51 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 193 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 50 >> endobj 52 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 194 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 51 >> endobj 53 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 195 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 52 >> endobj 54 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 196 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 53 >> endobj 55 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595. 32 841.92] /Contents 197 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 54 >> endobj 56 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 198 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 55 >> endobj 57 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 199 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 56 >> endobj 58 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 200 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 57 >> endobj 59 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 201 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 58 >> endobj 60 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 202 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 59 >> endobj 61 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 203 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 60 >> endobj 62 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.

32 841.92] /Contents 197 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 54 >> endobj 56 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 198 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 55 >> endobj 57 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 199 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 56 >> endobj 58 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 200 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 57 >> endobj 59 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 201 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 58 >> endobj 60 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 202 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 59 >> endobj 61 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 203 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 60 >> endobj 62 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595. 32 841.92] /Contents 204 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 61 >> endobj 63 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 205 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 62 >> endobj 64 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 206 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 63 >> endobj 65 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 208 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 64 >> endobj 66 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 209 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 65 >> endobj 67 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 210 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 66 >> endobj 68 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 211 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 67 >> endobj 69 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.

32 841.92] /Contents 204 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 61 >> endobj 63 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 205 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 62 >> endobj 64 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 206 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 63 >> endobj 65 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 208 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 64 >> endobj 66 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 209 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 65 >> endobj 67 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 210 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 66 >> endobj 68 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 211 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 67 >> endobj 69 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595. 32 841.92] /Contents 212 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 68 >> endobj 70 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 213 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 69 >> endobj 71 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 214 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 70 >> endobj 72 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 215 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 71 >> endobj 73 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 216 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 72 >> endobj 74 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 217 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 73 >> endobj 75 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 218 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 74 >> endobj 76 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.

32 841.92] /Contents 212 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 68 >> endobj 70 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 213 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 69 >> endobj 71 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 214 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 70 >> endobj 72 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 215 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 71 >> endobj 73 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 216 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 72 >> endobj 74 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 217 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 73 >> endobj 75 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 218 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 74 >> endobj 76 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595. 32 841.92] /Contents 219 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 75 >> endobj 77 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 220 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 76 >> endobj 78 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 221 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 1 >> endobj 79 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 222 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 2 >> endobj 80 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 223 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 3 >> endobj 81 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 224 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 77 >> endobj 82 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 225 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 78 >> endobj 83 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.

32 841.92] /Contents 219 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 75 >> endobj 77 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 220 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 76 >> endobj 78 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 221 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 1 >> endobj 79 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 222 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 2 >> endobj 80 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 223 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 3 >> endobj 81 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 224 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 77 >> endobj 82 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 225 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 78 >> endobj 83 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595. 32 841.92] /Contents 226 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 79 >> endobj 84 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 227 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 80 >> endobj 85 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 228 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 81 >> endobj 86 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 229 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 82 >> endobj 87 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 230 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 83 >> endobj 88 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 231 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 84 >> endobj 89 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 232 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 85 >> endobj 90 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.

32 841.92] /Contents 226 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 79 >> endobj 84 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 227 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 80 >> endobj 85 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 228 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 81 >> endobj 86 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 229 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 82 >> endobj 87 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 230 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 83 >> endobj 88 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 231 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 84 >> endobj 89 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 232 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 85 >> endobj 90 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595. 32 841.92] /Contents 233 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 86 >> endobj 91 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 234 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 87 >> endobj 92 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 235 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 88 >> endobj 93 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 236 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 89 >> endobj 94 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 237 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 90 >> endobj 95 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 238 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 91 >> endobj 96 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 239 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 92 >> endobj 97 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.

32 841.92] /Contents 233 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 86 >> endobj 91 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 234 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 87 >> endobj 92 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 235 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 88 >> endobj 93 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 236 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 89 >> endobj 94 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 237 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 90 >> endobj 95 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 238 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 91 >> endobj 96 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 239 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 92 >> endobj 97 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595. 32 841.92] /Contents 240 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 93 >> endobj 98 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 241 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 94 >> endobj 99 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 242 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 95 >> endobj 100 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 243 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 96 >> endobj 101 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 244 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 97 >> endobj 102 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 245 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 98 >> endobj 103 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 246 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 99 >> endobj 104 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.

32 841.92] /Contents 240 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 93 >> endobj 98 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 241 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 94 >> endobj 99 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 242 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 95 >> endobj 100 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 243 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 96 >> endobj 101 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 244 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 97 >> endobj 102 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 245 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 98 >> endobj 103 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 246 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 99 >> endobj 104 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595. 32 841.92] /Contents 247 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 100 >> endobj 105 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 248 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 101 >> endobj 106 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 249 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 102 >> endobj 107 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 250 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 103 >> endobj 108 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 251 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 104 >> endobj 109 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 252 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 105 >> endobj 110 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 253 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 106 >> endobj 111 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.

32 841.92] /Contents 247 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 100 >> endobj 105 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 248 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 101 >> endobj 106 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 249 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 102 >> endobj 107 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 250 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 103 >> endobj 108 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 251 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 104 >> endobj 109 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 252 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 105 >> endobj 110 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 253 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 106 >> endobj 111 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595. 32 841.92] /Contents 254 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 107 >> endobj 112 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 255 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 108 >> endobj 113 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 256 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 109 >> endobj 114 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 257 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 110 >> endobj 115 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 258 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 111 >> endobj 116 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 259 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 112 >> endobj 117 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 260 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 113 >> endobj 118 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.

32 841.92] /Contents 254 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 107 >> endobj 112 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 255 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 108 >> endobj 113 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 256 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 109 >> endobj 114 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 257 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 110 >> endobj 115 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 258 0R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 111 >> endobj 116 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 259 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 112 >> endobj 117 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 260 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 113 >> endobj 118 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595. 32 841.92] /Contents 261 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 114 >> endobj 119 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 262 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 115 >> endobj 120 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 263 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 116 >> endobj 121 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 264 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 117 >> endobj 122 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 266 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 118 >> endobj 123 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox[0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 267 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 119 >> endobj 124 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.32 841.92] /Contents 268 0 R /group> /Tabs /S /StructParents 120 >> endobj 125 0 obj > /ProcSet [/PDF /Text /ImageB /ImageC /ImageI] >> /MediaBox [0 0 595.