How to help an immature child grow up

Helping Kids Who Are Immature

As children grow up, the world’s expectations of them seem to change at the speed of light. Schoolwork is suddenly more challenging. Sports that were fun become more competitive and physically demanding. Activities, games, and TV shows your child and her friends loved one day are considered “babyish” the next.

All kids struggle to navigate shifting social norms and expectations of parents or teachers, but when a child matures more slowly than her peers, the changes can leave her feeling left out, embarrassed or bewildered by the things her friends are doing. Luckily, as every formerly awkward adult knows, immaturity is usually temporary, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy for kids who are in the thick of it.

“In most cases, as kids grow up, things even out,” says Rachel Busman, PsyD, a clinical psychologist. “They’re going to catch up. But the process can be hard.” Our role as parents, she explains, is to reassure kids and give them the support and scaffolding they need to make it through.

Children whose birthdays place them at the younger end of the class are more likely to be less mature than their classmates, but age isn’t the only factor, as kids mature at different paces.

In younger kids some signs of immaturity might be:

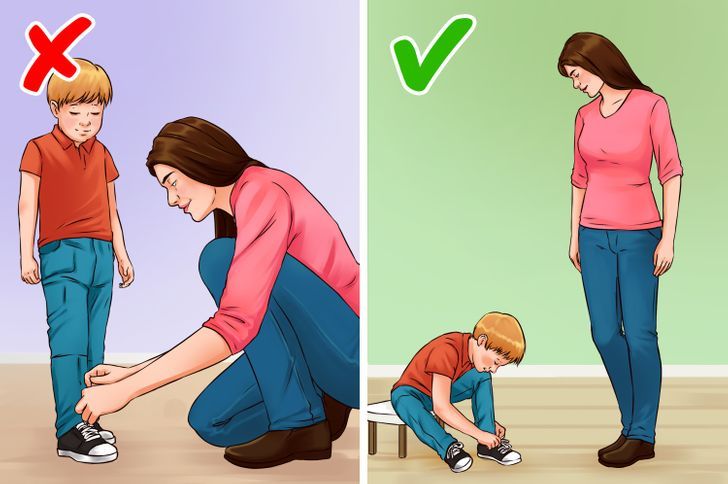

- Needing a little extra attention or help to do things her peers will do independently

- Being less physically coordinated than other children her age

- Becoming easily upset or overwhelmed or having trouble calming herself down when things don’t go her way

- Struggling to adapt to new concepts in school

- Being physically smaller or less developed than other kids her age

- Hanging back or avoiding activities that are new or challenging

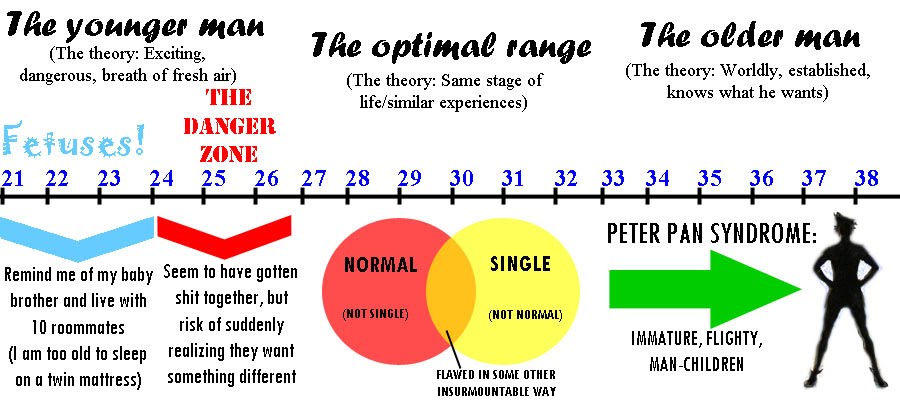

As kids get older, immaturity might look like:

- Age-inappropriate interests, for example a preteen who’s still watching Paw Patrol

- Social awkwardness, discomfort with new social relationships like dating, or unsupervised group hang outs

- Rigidity or unwillingness to try new things

- Being “grossed out” by conversations about sex and sexuality

- Being less physically developed than his peers

- Difficulty adapting to new academic challenges

It’s also important to note that kids may be less mature in one area, and advanced in another. For example, a child might be at the top of her reading group but feel lost when it comes to the social complexity of middle school, even when it seems like all her friends have it figured out.

For example, a child might be at the top of her reading group but feel lost when it comes to the social complexity of middle school, even when it seems like all her friends have it figured out.

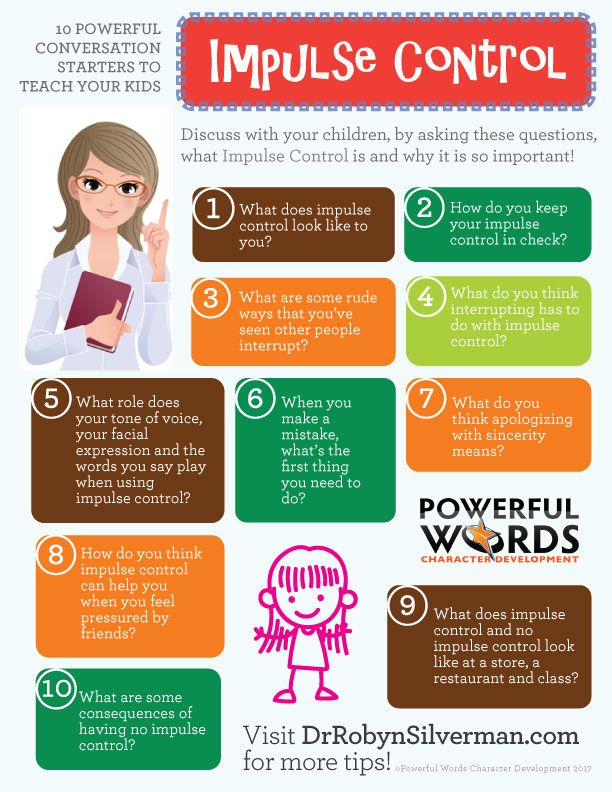

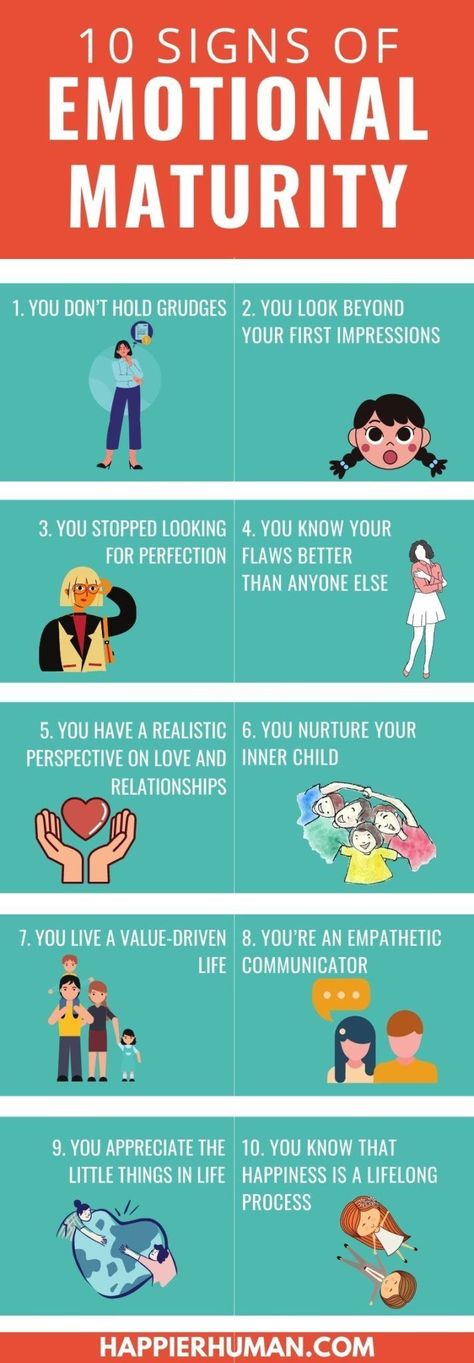

At its core, being mature isn’t about the toys kids are into, or whether they’re afraid of scary movies when their friends aren’t. The key work of growing up is acquiring a set of invisible skills called self-regulation — the ability to understand and manage emotions and impulses when they come up. Kids who struggle to self-regulate have a harder time dealing with even small setbacks and aren’t good at calming themselves down or controlling impulsive behaviors. For example:

- A child who stalks off in a huff if her friends won’t play the game she wants, bursts into tears if she doesn’t get the pink cupcake, or throws a tantrum when asked to clean her room or set the table.

- A pre-teen who smashes his video game controller when he loses, impulsively interrupts when friends or teachers are talking, or is late for everything.

Parents can help by encouraging children to practice skills and behaviors that bolster and teach self-regulation skills.

- Talk about how he could advocate for himself if he’s in a difficult situation. For example: if a child is uncomfortable with an activity his friends are doing you could develop a script he can use to defuse the situation: “You know, that’s not my thing but you guys have fun, I’ll catch up with you afterwards.”

- Work on negotiating and being patient. For example, if a girl gets upset when her friends don’t want to play her favorite game, you might say: “I know it’s upsetting when you and Jen want to do different things. Next time, maybe you could try agreeing that you’ll play a game she chooses first, then play one you choose afterwards.”

- Practice mindfulness with your child, and model what good self-regulation looks like. For example, “I get upset sometimes, too, and it can be hard to calm down. What if we both agree to take ten deep breaths next time we start feeling angry or upset?”

As kids learn better self-regulation skills, they’ll feel more confident and capable when it comes to navigating new or difficult challenges, and be better able to make smarter (and more mature) choices for themselves.

We want our children to grow at their own speed and feel comfortable and happy and excited about the things they love. But pressure to conform to what other kids are doing can be intense. The most hazardous part of immaturity is the potential for kids to be embarrassed, teased or bullied.

So how can parents walk the line between supporting a child where she is and making sure she’s not at risk? Let your child know that liking or doing things that are different than their peers isn’t something to be ashamed of, but that they may have to be ready for other kids to not want to play. For example, if a child likes to play with dinosaurs but his friends have moved on to Fortnite, you could make a plan for how he’ll talk to them about it. For example, he could say, “I’m going to play dinosaurs now, but can we play tag together later?”

“If a child is still sucking her thumb or bringing a stuffed animal to school at an age where that’s not really appropriate anymore it isn’t the end of the world,” says Dr. Busman. “We don’t want to shame kids or shut them down by saying, “Don’t be a baby. Get your thumb out of your mouth.”

Busman. “We don’t want to shame kids or shut them down by saying, “Don’t be a baby. Get your thumb out of your mouth.”

Still, it’s helpful to warn your child that her favorite activity may not be accepted by her peers. “It’s a chance to help kids understand that some activities are really only acceptable in certain places,” Dr. Busman explains. “You might say, I know that sucking your thumb is super relaxing, but you know I haven’t seen any of the other kids doing it at school. I wonder if that means that’s something that’s just better to do at home? What do you think?”

Keep communication open

Unfortunately, no amount of planning or practice can totally ward off the potential for bullying so parents should keep their antennae up.

The best way to know what your child is dealing with is to keep an open line of communication. That may require persistence. Ask open-ended questions and give kids as many opportunities as you can to tell you what’s going on in their lives. For example, if your child reports that a girl she was friends with no longer wants to play, take it as an opportunity to do some detective work. Instead of saying, “Oh, I’m sorry,” which kind of shuts the conversation down, try, “That sounds upsetting. Has anything happened or changed between you guys lately?” If she doesn’t want to answer, or simply says “I don’t know,” give her some space, but make a point of checking in again later.

For example, if your child reports that a girl she was friends with no longer wants to play, take it as an opportunity to do some detective work. Instead of saying, “Oh, I’m sorry,” which kind of shuts the conversation down, try, “That sounds upsetting. Has anything happened or changed between you guys lately?” If she doesn’t want to answer, or simply says “I don’t know,” give her some space, but make a point of checking in again later.

If you’re concerned your child’s immaturity might be causing problems for her, start by doing some research into what her universe looks like. What are other kids your child’s age listening to, reading, wearing, watching, etc.? How do they compare to your child’s interests? If you find something she might be interested in but hasn’t picked up, like a band or a tv show, try making a plan to check it out together.

And if your child has an interest her friends think is silly, find somewhere — a club or group or class — where she’s able to do it in an accepting, judgment-free space.

Finally, if you’re worried your child might be uncomfortable or being bullied at school, enlist her teachers or the school’s guidance counselor as an ally. “If you sense that your kid might benefit from a little extra scaffolding at school, you could ask them to keep an eye out for bullies, and to maybe help her along socially until she’s feeling more comfortable.” Even if you don’t suspect your child is being bullied it might be a good idea to schedule a check-in with your child’s teacher. He may be able to give you a better idea of the social and academic pressures she’s facing at school.

When to be concernedIn some cases, what looks like immaturity may have a different cause. Early signs of ADHD, some learning disabilities, anxiety and autism can all be mistaken for run-of-the-mill immaturity. Behaviors that seem extreme, or don’t fade as children grow, warrant a visit to your child’s pediatrician or a clinician.

Some things to watch for include:

- Speech delays

- Significant lack of coordination that is age-inappropriate — for example, a child who has difficulty using a fork or trouble writing legibly long into grade school

- Total lack of interest in social activities

- Serious anxiety around social situations like sleepovers or parties, or trouble making or keeping friends

- Significant sleep issues that are age-inappropriate, for example a 9-year-old who struggles to sleep through the night without parental intervention

- Academic difficulties that have a significant impact on grades

- Problems with impulse control or concentration

- Tantrums or meltdowns in elementary or middle school

In most cases though, being immature is just a part of growing up, like having knobby knees or braces. Giving your child the help and support she needs to navigate it in a safe, less stressful way will help her land on her feet when she catches up and give her powerful tools to care for herself both now and when she’s “mature. ”

”

My Daughter is Immature and She's Annoying her Friends

By Dr. Tori Cordiano, Ph.D.

Dear Your Teen:

I’m concerned about my 12-year-old girl’s behavior being too immature. One-on-one, my 12-year-old daughter is very sweet, thoughtful, kind, and funny. But in a group setting, she transforms into someone else. She is desperate for attention, trying too hard to be funny. She is oblivious to the fact that she comes across as obnoxious and immature. I’ve seen that other kids get annoyed by her.

She has a few good friends but even they lose patience with her silliness. I’ve tried talking to her about it but she honestly doesn’t seem to understand her 12-year-old behavior problems. I worry that continuing to point out concerns with her immature behavior will not only hurt her feelings but also could cause her to feel rejected by her parents (her dad talks to her as well). But I also strongly feel that it would be wrong to ignore it and allow her to act this way unchecked. I’m at my wit’s end.

I’m at my wit’s end.

EXPERT | Tori Cordiano, PhD

Oh, if only there was a way to make it easier to be 12 years old! Most adults would be eager to gloss over this age in our recollections of our own childhoods. Several factors coalesce to create this perfect, awkward storm. First, many 12-year-olds are juggling two different emotions. They mostly want to be older; but sometimes they want to be little again. This struggle can create behavior that seems inappropriately silly in certain situations. They also experience a heightened intensity of emotions. Their highs are higher and their lows are lower than ever before. Finally, friendship groups often change in sixth and seventh grade to include new members and exclude others. The shifting of friends can leave 12-year-olds feeling as if the ground is shifting beneath them in unpredictable ways.

Tween are trying to navigate this changing landscape. Often, they resort to goofy behavior or reactions that seem “too big” for the situation.

Here’s how you can approach your daughter.

1. Share your own memories.

Try to come from an empathetic, loving place when addressing this with your daughter. Wait for a moment when the timing is natural (e.g., she brings up a situation with friends). In response, you might start by reflecting on your own memories of what it was like to be 12.

2. Make positive observations about her behavior.

Point out things you observe. She has solid friendships. She seems to be more comfortable one-on-one or in smaller groups. The more opportunities she has for those types of encounters, the more confidence she’ll gain in her social skills and have the chance to be herself.

3. Explain the research.

Research finds children with one or two close friendships have higher levels of well-being than children who are identified as “popular” by their peers. Let your daughter know that there is no need to be friends with a large group. It’s often easier and more enjoyable to have a few friends instead.

4. Help her recognize her inappropriate behavior.

In the context of a gentle conversation, try to help your daughter identify aspects of large-group socializing that make her nervous. Then help her connect the dots to her goofy behavior in those settings.

5. If necessary, consider social skills coaching.

If your concerns grow, or if others (e.g., teachers, coaches) are concerned as well, consider a social skills group targeted toward girls her age. These can be great resources for kids and teens in need of some help and practice developing social skills in a neutral, safe environment.

Finally, take solace in the fact that fellow 12-year-olds are often more forgiving of this type of socially immature behavior than adults. Her friends may simply take it in stride as part of the friendship, knowing there are other qualities they appreciate about your daughter.

How to discipline a psychologically immature child

It is impossible to influence a child who is unable to influence himself. It is impossible to control a person who does not control himself. Therefore, discipline, or the establishment of boundaries, compliance with the framework in relation to a psychologically immature person (and children are psychologically immature by default) occurs as if bypassing. It is impossible to act directly without affecting the psychological and emotional development and without spoiling the relationship.

It is impossible to control a person who does not control himself. Therefore, discipline, or the establishment of boundaries, compliance with the framework in relation to a psychologically immature person (and children are psychologically immature by default) occurs as if bypassing. It is impossible to act directly without affecting the psychological and emotional development and without spoiling the relationship.

Minimize punishments and sanctions as they tend to make the child closed, callous and complicate the situation. Consequences can work well for children and adults who understand these consequences. That is, a person must be mature enough to see ahead, to assume: these specific actions of mine will lead to specific results.

A young child does not have this understanding, life just happens to him. So he broke a cup, and then suddenly my mother starts screaming, punishing, taking away and not giving him more milk. There is no understanding of the consequences (“I did something and something else will follow”), so we try to minimize the use of sanctions. Threats not to give milk, sweets, not to let him go for a walk, the child perceives as a statement that his mother does not love him, his mother wants to harm him. Sanctions undermine the relationship with the child, so they should be avoided.

Threats not to give milk, sweets, not to let him go for a walk, the child perceives as a statement that his mother does not love him, his mother wants to harm him. Sanctions undermine the relationship with the child, so they should be avoided.

If you know that your child is starting to overflow after half an hour with this boy on the playground, then let them play very well for 25 minutes, and then an adult takes responsibility, compensates for the immaturity of the child and distracts him: "Oh, now let's go and ride over there on the swing."

Or you hear in the next room that nervous notes are growing among your children in conversation, because one does not give the other pencils, and everything is about to turn into a scandal. Don't wait for the fight, compensate, go and divert attention to something else, switch them.

The child cannot control himself in this situation, and we cannot control him. We cannot say: “That's it, I warned you, behave yourself, and I will go about my business. ” That is, of course, we can say, but they are not able to behave well.

” That is, of course, we can say, but they are not able to behave well.

Know your child, anticipate him. Try to compensate for the circumstances, designate those in which he simply cannot cope. As, for example, with a six-month-old child: we don’t give him a sharp knife in his hands, but put it somewhere far away, we hide matches from children, we put pills and chemicals on the shelf higher, and we don’t just follow the child on the heels, forbidding him to climb into some kind of jar. We do not tell him that if you drink it, you can die, or rather, we say, but we do not really expect that it will work.

We understand that this is not the case with a child, and so is everything else: watch the circumstances, orchestrate the context, set the rules, organize the space and conditions so that the child does not get into problems, so that you do not have to say “no” or call him to order.

With young children, it is very important that there is some sort of routine, set procedure. For example, in the evening we take a bath, brush our teeth, read a book, fall asleep, all this is done at the same time every day. Routines, rituals, structure are of great importance. All this helps the child not to argue (to accept what is happening), just as we do not argue with the sunrise or sunset. We know that every day begins with sunrise and ends with sunset, and it doesn't occur to us to resist it. Therefore, structures, routines, rituals help the child to accept the way things have always been.

For example, in the evening we take a bath, brush our teeth, read a book, fall asleep, all this is done at the same time every day. Routines, rituals, structure are of great importance. All this helps the child not to argue (to accept what is happening), just as we do not argue with the sunrise or sunset. We know that every day begins with sunrise and ends with sunset, and it doesn't occur to us to resist it. Therefore, structures, routines, rituals help the child to accept the way things have always been.

This is very important - children's perception channel is very narrow. In children under 5-7 years old, the brain structures are not even ready to process two signals at the same time. If the child's attention is directed to something else, then he can no longer perceive you at this moment. He either plays with a toy or listens to you.

If a child plays with his father, he often says - "Mom, go away, don't bother us." If he plays with a typewriter, and you shout something to him from the kitchen, he simply does not hear you. So if you need to give some direction to a small child, first grab his attention. "Small" here is a relative term, we are looking at psychological maturity, and a fourteen year old can be small, especially if they are adopted children. Even your husband can be "small" in this sense.

So if you need to give some direction to a small child, first grab his attention. "Small" here is a relative term, we are looking at psychological maturity, and a fourteen year old can be small, especially if they are adopted children. Even your husband can be "small" in this sense.

Capture is a specific term, it means tuning into one wave. Make sure you can be heard and seen before giving instructions.

How to do it - for example, a child is playing with a typewriter, you approached him, sat on the floor, appeared on the same side with him, asked what he was playing, talked, carefully turned your attention to yourself, hugged, kissed. Then you can say: "Well, let's go eat, dinner is ready." But first we made sure that the child hears and sees you. This is very important - make sure that the child is attuned to you (especially if he is small) more often, and not just when you give him instructions.

Relatively speaking, this is a manipulative technique, the so-called matchmaking - eyes, a smile, a nod. We smile, nod and say: “Great weather, right? Beautiful car. What a wonderful suitcase you have. Why don't you buy from me a very necessary thing for your car, a polishing cloth for $ 30? Look, it will fit perfectly in your car.

We smile, nod and say: “Great weather, right? Beautiful car. What a wonderful suitcase you have. Why don't you buy from me a very necessary thing for your car, a polishing cloth for $ 30? Look, it will fit perfectly in your car.

This is how we capture attention – through the eyes, the smile, the nod. And in general, we smile at children more often. And certainly this must be done before we give instructions. Write it down somewhere for yourself, tie a knot for yourself as a keepsake: before giving any instructions, grab the attention of the child, make sure that he hears and sees you. Even if you are sure that he will hear you anyway, because you are screaming very loudly from the next room.

Direct behavior that would come naturally with greater maturity. Directing behavior is the same as directing in theatre. There is, suppose, the need to play a play in which the characters are adults and very mature. Hamlet, for example, or King Lear. The director has two ways - to wait for an actor who will someday psychologically mature to the level of the hero of the play (but directors usually don’t do that!) or to do otherwise. They take a young actor and tell him: “Put this on, do this, say this, don’t go here, go here, don’t do this, but do this.” And young enough, no matter what degree of maturity, the actor looks quite mature on stage and plays his role quite successfully.

They take a young actor and tell him: “Put this on, do this, say this, don’t go here, go here, don’t do this, but do this.” And young enough, no matter what degree of maturity, the actor looks quite mature on stage and plays his role quite successfully.

We do exactly the same directing with the children: look, we pet the kitten like this, and when we come to the grandmother, we need to look into her eyes, smile and make a curtsy (for example). If you are playing on the court and you suddenly feel like you want to hit someone, run to me and tell me about it. Try not to hit anyone, but if you notice or feel that your fists are clenching, then come and tell me about it. “Mom, my fists are no longer obeying me. "Baby, I'll do something with your fists."

In this way, we explain to the child how to behave, while in some situations he can behave quite well himself, but the main thing here is not to forget that immaturity has not gone anywhere, we just staged the behavior successfully.

If you meet your friend and her child on the playground, you explain to your child (and she to hers) that we do not pour sand on anyone's head and that we do not hit each other with a shovel. And here the children are playing peacefully for some time. Then something happens, for example, one of them crushes a sand cake made by another, they have a stone and a stick under their hands, and they use both, because the mothers did not say anything about the stone and the stick. The child does not see, does not understand the context, the words “behave well” mean nothing to him. So, you need to direct it, designate in detail how to behave, stipulate: you can do this and that, but you can’t do this and that.

This goes hand in hand with directing. Here, the younger sister should be held on the handles like this; If you want to touch her, then you can do it like this. We wear a kitten like this, and we stroke it like this. That is, we show what is right, what works. “Oh, how well you did to put the plates on the table, how well you did to clean the floor. ” We show what works. "It's great that you thought to wring out the rag, and not just take it out of the bucket and smear the water on the floor."

” We show what works. "It's great that you thought to wring out the rag, and not just take it out of the bucket and smear the water on the floor."

It is very important for a child to realize that he succeeded, that he is correct, good, that he tried to do something, and he succeeded. In general, we support the good intentions of the child. He often cannot realize, withstand, observe them, but at least he can work with them.

You stand on the side of the child, on the side of this intention, and together overcome difficulties. You can say: “Well, we agreed, and you told me that you would do your homework on your own every day, without interruptions.” If there is this consent, intention on the part of the child, then you can sit down with him and think about how you can make sure that he does not forget to do them.

He may need to be reminded or helped. Think about it together. But if there is no intention, then nothing can be done about it.

It must be remembered that babies are not able to work. What does it mean? Work is some action that you do for the sake of a result. The game is the actions that you do for the sake of the process. That is, in the game, the result can also be quite important, but the process is more important.

What does it mean? Work is some action that you do for the sake of a result. The game is the actions that you do for the sake of the process. That is, in the game, the result can also be quite important, but the process is more important.

The importance of the game is now noted in many scientific anthropological works, neuroscientists study it very actively. The game allows us to make the child happy to eat these peas, clean his room, brush his teeth, go to bed and lie quietly, like a mouse, because the sister is sleeping, and we will play with the mouse so as not to wake her up.

For the sake of play, a child may agree to voluntarily do many things that he does not want to do without play or will do them with a cry.

If the focus is "Well, let's get dressed and let's go outside!" - it must be remembered that for a child the process is more important than the result. Due to his psychological development, he still cannot keep a perspective in his head. If now he does not want to dress, then for the sake of a walk he will not do this. Very often, parents complain that the child is difficult and long to get dressed on the street, and then runs around there joyfully for two hours. Or we go somewhere to the park, or to the playground - the child will fray all the nerves until we get there, and then does not want to leave from there.

Very often, parents complain that the child is difficult and long to get dressed on the street, and then runs around there joyfully for two hours. Or we go somewhere to the park, or to the playground - the child will fray all the nerves until we get there, and then does not want to leave from there.

The reason is that current affairs are more important for a child – it is difficult for him to distract himself from some of his childhood affairs, the process of dressing is difficult for him, it can be cold, unpleasant, bad weather outside. For him, this is more important than the distant prospect of getting to the site.

But when they have already arrived, then he plunges into the situation in which he now finds himself, into a new process. It must be remembered that the child is always immersed in the situation in which he is now. Therefore, to say to a three-year-old kid: “Learn English, it will come in handy in your life” is useless. But songs, nursery rhymes, finger games, cartoons in English - that's it.

Author: Olga Pisarik

NETOTAL CONTROL - articles by our partners

Every loving parent seeks to surround their child with care and attention, which is quite natural. But sometimes there is too much parental attention, and care becomes excessive. Psychologists call this style of parents' relationship with their child hyperprotection.

It can be said that overprotection is when mothers and fathers strive to control every step of the child, not allowing him to show independence. A common motive for such behavior is constant fear for the baby, obsessive fears for his life and health, the desire to protect children from wrong children from wrong decisions, they say, “we adults know better.” It is no secret that such behavior of parents can lead to very unpleasant consequences in the future for a person who has grown up in such an atmosphere.

Specialists of the Nebbiolo Clinical Research Center shared their professional views on the problem: Candidate of Psychological Sciences, family, child and adolescent psychologist Igor Vladimirovich Shchelin and clinical child and adolescent psychologist Svetlana Alexandrovna Burlutskaya.

“Today no one argues with the fact that many problems of an adult are rooted in his early childhood,” says Igor Shchelin. - Will your child in the future become a successful and independent person, able to cope with difficulties, achieve goals in life? It largely depends on how you, the parents, treat him now, while he is still small.

It is clear that when a child is born, he needs a lot of care, but with age it is reduced in proportion to the skills he acquires. For example, at the age of 3, the period “I myself!” begins, when children expect the family to recognize their independence and independence. What is important is the desire of the baby to notice and consciously give him more and more freedom. In other words: everything that a child can do on his own at his age, he must do on his own. It is important for parents to remember that their excessive control should not limit the initiative of the baby. Otherwise, overprotection leads to infantilism, lack of independence of children, and then adults. Of course, this may have a negative impact in the future on their professional career and family life.

Of course, this may have a negative impact in the future on their professional career and family life.

– Parents who are dissatisfied with their grown children quite often come to see us, Svetlana Burlutskaya continues the conversation. “They complain that their children have grown up insecure, having difficulty communicating with their peers. And, of course, parents are interested in the reasons for such behavior of their children, most often not even realizing that the reason is incorrect or distorted parenting tactics. The child's personality and abilities are developed only in those activities that he engages in of his own free will and with interest.

An immature, passive teenager is a sad picture, but this is not the only result of overprotection and total control. Much depends on the nature of the child. For example, if he is brisk and headstrong, then in response to excessive control, a teenager may rebel, protest, and even leave home, where he was not given freedom and did not notice his growing up.